Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1319

February 16, 2015

Making (a Little) Progress on CEO Pay

Since companies can’t seem to solve the divisive problem of exorbitant CEO pay on their own, legislation may well turn out to be the best fix. Here’s how it’s starting to help in various parts of the world, though there’s still a lot of work to do.

SEC registrants in the U.S. — public companies, mutual funds, investment advisers, transfer agencies, and broker dealers — are required by the Dodd-Frank Act (passed by Congress in 2010) to conduct shareholder advisory votes at least once every three years on compensation for board members and the highest-paid executives. Investors have used this process to voice their concerns, which is all to the good (it puts pressure on companies to change their practices), but the votes are nonbinding. In 2012, for instance, shareholders said no to almost $15 million in compensation for Vikram Pandit at Citigroup and to almost $6 million for Fernando Aguirre at Chiquita Brands. Even though both CEOs received their packages, against investors’ better judgment, they’ve since been forced out for their disappointing performance.

Shareholders in the UK have had advisory votes on pay since 2002 — but the British government has tightened the rules even more. For a little more than a year, UK public companies have had to prepare an annual remuneration report, and shareholders’ votes on the policy behind it are binding. If a company fails a vote, it can’t implement any of the proposed compensation changes — it reverts to the last approved pay scheme.

While many European companies have their own say-on-pay regulations — Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, for instance — the European Commission has proposed increasing shareholder power across the board. If the legislation is adopted, all EU-listed companies’ remuneration policies will be subject to binding shareholder votes every three years.

Australia has gone even further, with its “two strikes” policy: If 25% or more shareholders vote “no” on a company’s remuneration report at two consecutive annual general meetings, that triggers a vote to spill the board. And if this second resolution is passed, all directors (except the managing director) must stand for re-election within 90 days. This legislation, among the strictest in the world, has helped shareholders not just find their voices but exercise their muscle.

Just a few months ago, there was a first strike against Newcrest Mining, Australia’s largest gold miner. At its latest annual general meeting, 45% of shareholder votes went against the remuneration report for several reasons, including horrible performance on the share market and billions in write-downs on one of its mines. Here was the real clincher: Newcrest announced that the new CEO could, with bonuses, earn 62% more than his predecessor — and a larger base salary, at $2.3 million, than his counterparts at the much larger miners BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto.

First strikes have also occurred at Uranium producer Paladin, company car fleet manager McMillan Shakespeare, Seven Group (which has major media holdings, among other diversified interests), and engineering services company UGL.

Shareholders are OK with turning a blind eye to CEO packages when the profits of their companies skyrocket. But when fortunes change, they hasten to put the brakes on executive remuneration. Government action has given them more power to do that.

No board wants to receive a “fail” from shareholders, whether that vote is advisory or binding. It hurts the company’s reputation not only with investors but also with suppliers, customers, and the general public. But legislation ratchets up the urgency, and a recent cross-country study for the U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve shows that it’s actually starting to work. From 2003 to 2012, growth in CEO compensation was much lower (5.5%, on average) at firms that were subject to say-on-pay laws than at those that weren’t (8.1%).

So, expect more laws.

[image error]

Giving Effective Feedback When You’re Short on Time

Virtually all of the young executives I work with want to be good managers and mentors. They just don’t have the time — or so they believe. “I could either bring in a new deal, or I could take one of my people out for lunch to talk about their career,” a financial services leader told me recently. “In this industry and in this market, which one do you think I’m going to pick?”

Good question. It’s not easy to help your employees develop even as you take advantage of every business opportunity, but you can make coaching easier on yourself, in part by giving feedback efficiently.

Once you’ve identified that you need to give feedback to a direct report, you can make that process more efficient in three ways.

Create a standard way in. For the majority of managers, providing feedback — particularly constructive feedback — is stressful and requires significant forethought. How should you bring up the bungled analysis, the hurdles to promotion, or even the meeting that went unusually well? Like chess masters, we spend most of our time contemplating the first move. That’s why the key to reducing the time you spend mulling over and preparing for each coaching conversation is to have a standard way in: a simple, routinized way to open discussions about performance.

Keep it simple, and announce directly what’s to come. A straightforward “I’m going to give you some feedback” or “Are you open to my coaching on this?” gets immediate attention and sets the right tone. It will make it easier to prepare for the game if you have your opener ready. Furthermore, your direct reports will become familiar with your opener, and that will help them be attuned to and hear the feedback more clearly.

Excerpted from

HBR Guide to Coaching

Managing People Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Be blunt. The number one mistake executives make in coaching and delivering feedback to their people is being insufficiently candid—typically, because they don’t want to be mean. If you’ve ever used the phrase “maybe you could . . .” in a coaching conversation or asked one of your people to “think about” a performance issue, there’s a 99% probability you’re not being blunt enough. But the more candid you are, the more likely your coachee is to hear your message, and thus the more likely you are to have impact, and quickly. The trick to being candid without feeling like an ogre? Be honest, be sincere, be personal — while addressing the issue head-on.

The best feedback I ever received came a few years into my career, directly after a terrible meeting I had with senior management, in which I had been both unprepared and defensive. As we rode down in the elevator afterward, my boss said quietly, “Next time, I expect you to do better.” Don’t dance around the issues, and don’t let the person you’re coaching do so either.

Ask him to play it back. If your feedback doesn’t end up sticking, you’ll need to deliver it a second time — and a third, and a fourth — all of which takes your valuable time and managerial energy. To avoid the need for encore performances, check to make sure you’ve made an impact on the first go-round by asking the person you’re coaching to paraphrase what he heard. If your coachee can clearly explain to you — in his own words — what he needs to change or do next, that goes a long way to ensuring he’s gotten the message. You’ll then know that the conversation is over and you can get back to other things. If the message is muddled, you can correct it immediately. In either case, you’ve limited the need for future follow-up.

By doing these things regularly (perhaps even daily), you’ll not only save yourself and your coachee time, but your employees will feel that you’re not just their boss, but a coach. They’ll sharpen their skills and stay motivated. And for any manager, that’s time well spent.

This post is excerpted from the HBR Guide to Coaching Employees .

[image error]

February 13, 2015

What Everyone Should Know About Office Politics

Nobody really likes office politics. In fact, most of us try to avoid it all costs. But the reality is that companies are, by nature, political organizations, which means that if you want to survive and thrive at work, you can’t just sit out on the sidelines. If you want to make an impact in your own organization, like it or not, you’re going to need to learn to play the game. That doesn’t mean you have to play dirty, but .

In our HBR.org series on office politics, we asked experts to provide insights and practical advice for navigating the political playing field in any organization. Together, these pieces offer a solid foundation for learning the rules of engagement.

First, it’s important to understand why playing politics is so unavoidable. Work involves dealing with people, and people are, whether we like to admit it or not, emotional beings with conflicting wants, needs, and underlying (often unconscious) biases and insecurities. Our relationships with our colleagues — with whom we both collaborate and compete for promotions, for a coveted project, or for the boss’s attention — can be quite complex. Not everyone is friend or foe; many people are somewhere in between. And more people than you might think are lying to get ahead or gossiping as way to exchange information, vent their frustrations, and bond with co-workers when they don’t trust their leaders. Put all of this together and you’ve got a highly politically-charged work environment.

So, what can you do to navigate this dizzying maze?

Let’s start with an approach for three common scenarios that many of us will have to deal with at some point in our careers: 1) When you’re mad about a decision that affects you; 2) When you need to make critical comments in a public forum; and 3) When a colleague goes postal on you. It helps to have guiding principles to call on when you find yourself in one of these situations, keeping in mind that the context of the situation determines how you should proceed.

While these are common scenarios, there are lots of other minefields you’ll come across in your organization. Perhaps you’re dealing with a boss who’s a control freak. Or, maybe you’re knee-deep in the politics of a family business, when you’re not actually part of the family. Even the most seasoned executive, who’s worked long and hard to build trust and political capital, can make the wrong move and lose years’ worth of ground in an instant. Perhaps you’ve made a very public mistake that requires an apology. It’s important to admit your flaws, fix your mistake, and reclaim respect.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Office Politics

Communication Book

Karen Dillon

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Women have a unique set of challenges when it comes to navigating office politics. Research shows that women are more likely to become nervous and uncomfortable in meetings when interpersonal conflicts and other political challenges arise. And women executives say they believe politics present a particular dilemma for them: On one hand, they feel uncomfortable engaging in quid-pro-quo behavior and political maneuvering. On the other, they acknowledge that it’s all but impossible to operate above the political fray. Some of the most effective practices that help women become more politically savvy include finding a sponsor within the organization, treating politics like a game, doing some advance “political homework” before important meetings, and learning to lobby for yourself. After all, the most savvy women and men alike know how to promote themselves without looking like a jerk.

No matter what the challenge, one of the surest ways to improve your political prowess is to strengthen your emotional intelligence — it’s a key differentiator between star performers and the rest of the pack. If you recognize any of these telltale signs in yourself, don’t wait until it’s too late to address the problem. And at the end of the day, remember: when it comes to standing out in your organization and carving out a bigger leadership role for yourself, you’re never too experienced to fake it till you make it.

[image error]

The Taxi Industry Can Innovate, Too

On a recent trip to Manhattan I found myself being driven by an Uber driver who was obsessively following directions from his GPS. I grew irritated, convinced that the route we took was less than direct and far more congested compared to the path an experienced cabbie would have taken. I’ve loved using Uber since it launched in 2009, but my fondness for it has begun to fade.

My experience doesn’t necessarily signal a trend: Uber and Lyft remain popular with consumers, and with investors, who recently valued Uber at $40 billion. The ride-sharing startups are in the process of thoroughly disrupting the taxi industry.

But it’s far too early to eulogize the taxi industry. As my experience shows, a bad experience or two can cause individuals to rethink their fondness for the service. And if cabbies start playing a smarter defense, they may be able to more effective battle back against Uber and Lyft. Here’s how.

First, stop pushing for regulation. Instead, focus on deregulation. While Uber deserves kudos for being innovative, let’s be truthful: Its success has come from creatively exploiting a regulatory loophole. Uber argues that it is a rideshare service, not a taxi service. What’s the difference? Taxis cruise the streets seeking fares, while ridesharing services don’t, relying on apps to arrange a form of carpooling (wink, wink). As a result of this minor distinction, Uber has successfully argued it should be immune from taxi regulations.

Not being categorized as a taxi provides rideshare companies like Uber, Lyft, and Sidecar with a key pricing advantage. Taxis are required by law to charge pre-approved prices. In contrast, since Uber is a rideshare service, it has complete flexibility to raise and lower its prices based on demand. As a result, Uber undercuts taxis during off-peak times and charges premiums during high demand periods. Implementing surcharges not only increases profits, but also helps smooth out the traditional supply-demand imbalance that anyone who’s tried to hail a cab in a rainstorm has experienced. (Higher surge prices curb customer demand while also increasing the supply of drivers, since more drivers want to work during periods when they can charge more.) Archaic regulation has made taxis sitting ducks for ridesharing services.

Taxi companies are defensively lobbying to regulate ridesharing services. This is a bad idea and won’t work. Typically, more competition leads to deregulation. Consider the regulation-to-deregulation evolution in the long distance telephone market. AT&T once had a monopoly on long distance service and was thus regulated by the government. When Sprint and MCI entered the market with innovative offerings, the need for regulation vanished – competition ensured good service and fair prices. This exact scenario is occurring in the taxi market. Ridesharing is here to stay and as a result of this competition, it’s time to deregulate. Every car service should be allowed to set whatever price they want.

Copy Uber’s surge pricing model: Peak and off-peak is a standard pricing model used in hotels, airlines, even commuter trains. It’s a perfect way to deal with demand swings. Taxis should use it, too—and they should advertise it, by advertising current prices (+10%, -30%, etc.) on their cab-top digital billboards. This would allows taxis to benefit from flexible pricing in a key area where they still have a monopoly: on-street pick-ups.

Employ a new pricing model: It’s important to emphasize that for both taxis and rideshare companies, price is only a small component of profitability. Distance is as – if not more – important. For both businesses, a 10 mile trip is more lucrative than, say, a 1 mile one. Given this truism, companies should creatively use price to focus on per trip profitability. Riders, for example, can input their origin and destination into an app and receive a customized quote that takes into account the profitability derived from longer distances (i.e., discounted prices for longer trips). Another option is a Priceline style system: riders can bid a price (say, 85% of normal fare) for a pre-defined trip. It may make sense for a driver to take 85% of a normal fare for a 10 mile ride, for instance, compared to playing the lottery of “how far will the next fare go?”

Companies that use price to boost per-trip profitability will enjoy what economists term cream-skimming. They’ll attract profitable long haul rides while inferior (from a pricing perspective) competitors get stuck with low-profit, small-mileage fares.

Emphasize differentiation: Taxis should poke straight at a key side effect of the ridesharing model: Uber and Lyft drivers are inexperienced. It’s great that ridesharing enables part time drivers to pick up extra cash as a side job. But their inexperience means they rely too much on GPS. There is value in being driven by someone who has accumulated hard-earned knowledge of various routes and traffic patterns. At least in Manhattan, I’ll now always take taxis.

Develop an app: Taxi companies need to realize that people love using their smartphones. It’s simple: offer this convenience or lose business.

Uber’s growth and valuation has skyrocketed through a combination of innovation, excellent execution, and an anemic response from the taxi industry. Is Uber’s recent $40 billion valuation too high? It depends on the response of the taxi industry. A few straightforward initiatives by taxi companies – simply deregulating prices, for instance–makes Uber’s long-term ability to deliver profits that justify that valuation far from a slam dunk.

[image error]

When and Why to Part Ways with a Customer

Photo by Andrew Nguyen

List three customers you wish you could fire right now. That didn’t take long, right? Firing customers, when all other options are exhausted, should be a legitimate option — whether you’re working with a business-to-business multimillion dollar client or a business-to-consumer $10 customer. The customer is not always right and in some cases should not be the customer at all. It’s time to end the fear of customers’ public feedback and to start managing relationships with abusive customers in a disciplined way.

Some readers may dismiss this notion as the view of a consultant who does not understand real-world cash flow demands and financial pressures — but I’ve experienced this challenge first hand. We recently parted ways with our largest client because they were hurting morale and putting our reputation at risk. We fulfilled all our obligations to the client and then moved on. It wasn’t an easy decision, but one that we all ultimately agreed was necessary.

So ask yourself: Which customers do you want to serve and which customer behaviors do you want to eliminate? Here are five guidelines to consider as you reframe your own customer relationships:

Clearly define your ideal and non-ideal customers. When considering cultural fit and value, not every customer with a budget is an ideal customer. Unforgiving customers may be too costly to serve. Obnoxious, profanity-laden customers will damage employee morale. Individual customers with frequent calls to customer service are not ideal either. Develop a chart that displays both sets of traits side-by-side. Identify the costs associated with serving these customers and the impact on your profitability and the next steps will be obvious to all.

Design an appropriate response for outliers. Make sure that the customer-firing process is clear cut and impactful, but ensure there is still a touch of generosity. You do not want to adopt the negativity that the customer is bringing to your business. Firing customers is not a competition you win. It is unfortunate and can be hurtful to the person you are speaking to. When you deliver the news, put it in the context of finding “a better match” elsewhere. Take the time to explain to the customer why certain demands or behaviors may have been a customer-win, but do not represent a mutual win. Hotels often deal with this issue and can be a source of learning for those companies looking to come up with firing best practices.

Train employees on how to deal with abusive customers. Make sure that your staff knows how to handle problematic customers. Your employees may be operating under the “the customer is king” cliché, and may be trying endlessly to please every whim. Align their understanding to your new customer criteria and provide them with the tools and authority to act on it. Companies often do not conduct special training to handle entitled and abusive customers, therefore leaving employees to improvise. Introduce this training to your staff and allow them to practice behind-the-scenes before taking it public.

Empower employees to make on-the-spot decisions. Employees are your company’s frontline eyes and ears. They witness which customers are worth keeping and which are not. When a Southwest airlines employee charged an obese passenger for two seats, customer advocates from around the world cried foul. Southwest went to court and refused to settle. They eventually won the case. The logic behind it was quite simple: What would you say to the passenger sitting next to the obese passenger? He or she would ultimately be paying the price. This action was initiated by an employee who made a judgment call in the moment. The airline supported him all the way to court. Make sure your employees feel the same support. Provide them with the assurance and financial means they need to make these decisions on the spot.

Review and assess criteria regularly. Abusive customers will always come up with new tricks. REI cancelled its lifetime return policy due to customers blatantly purchasing products with the intention of returning them. Disney changed its handicapped access policy due to customer abuse. In both cases, all customers are now suffering because of the actions of a few outliers. If you offer a generous customer experience, you better believe someone will try to take advantage of it. Stay ahead of those advantage-takers.

The customer-empowered era is ushering in the trend of a customer-obsessed culture, but we should not confuse customer obsession with the acceptance of abusive behavior and loss of profits. Customer centricity is about loving and spoiling the right customers while leaving the rest to your competitors. Lose the fear of public dissatisfaction and continue to strive to delight and surprise the right customers through exceptional customer experiences. Then — and only then — will the customer always be right.

[image error]

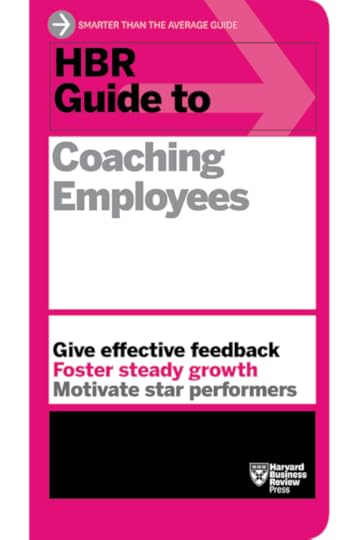

Are You Proud of How You’re Spending Your Time?

When you feel like you’re just one e-mail away from failure at work, it can seem ludicrous to take your eyes off of what you believe absolutely needs to get done to consider what you might regret in the future. The amount of demands coming at you feels so crushing and so unavoidable that you justify a missed soccer game here, a canceled dinner with a friend there, and a never-used gym membership over there, with the thought, I was just doing what it takes to get everything done.

Sometimes that thought is accurate when you have a truly urgent situation or a special event like preparing for an annual conference. However, in my experience as a time coach and trainer, I’ve found that reasoning is often a pretty façade for not knowing how to work smarter — so you end up working harder and sacrificing what’s important to you in the process. But when you neglect to consider common time regrets, you not only put a lien on your future happiness, but you can also decrease your effectiveness in and enjoyment of the present.

In my forthcoming ebook, How to Invest Your Time Like Money, I discuss how optimizing in the micro day-to-day activities is not the same as optimizing in the macro as a measure of success. For example, when you stop trying to get all tasks done from answering every e-mail to taking every meeting and start thinking about which activities matter most, you can get more of what’s important done now and live regret-free later.

If you want to stop making time investment choices subconsciously, based on what’s most urgent or most demanding, and start intentionally investing in what’s most important, start by understanding — and combating – these seven common time regrets, so that 20 years from now, you can look at your time investment with pride instead of remorse.

Not paying attention: If you have no idea how you invest your time, you’re probably not investing it in your highest priorities. This can leave you with an enormous sense of loss when you realize that you’ve let years of your life pass by that you can never get back and you have little to show for them. Start keeping a record of what you do by making note of key activities on your calendar or using a time tracking application, so you can begin to understand where you’re spending your time and where you might need to adjust.

Letting others steal your time: Legions of marketers work day and night thinking up ways to capture — and keep — your attention. They will gladly take as much of your time as they can get. So can the people around you. There’s never a lack of people requesting your time, from taking on a new project to volunteering for a committee to meeting for lunch. Depending on your professional situation, there may also be a strong pull for you to work longer hours and travel more. Engaging in media, spending time with others, and working can be wonderful things. But if you allow external forces to always dictate your time investment then you’re allowing others to steal your time. Practice saying “no” to what’s not most important to you so that you can invest in what is.

Deprioritizing family and friends: In the middle of deadlines and the many demands coming at you from all different directions, it can seem like less of a priority to make it home for family dinner, show up at a concert, go on a date with your spouse, call your parents, or connect with friends. Although in many ways these activities are less urgent, they are many times more important. A family dissolving doesn’t often happen in a single large event. Instead it erodes with each choice to not make the people who love you a priority. Engaging with friends and family can make life more fun and fulfilling, and provide an incredible amount of support during life’s ups and downs. Get these activities on the calendar so that you have clarity on your firm commitments. Each time you choose to spend time with someone else, you strengthen the relationship.

Skipping vacations: Taking time away from the normal day-to-day not only gives you the opportunity to have new experiences and bond with friends and family, but also it helps you reduce stress and gain perspective. Studies show that skipping vacations could put you at a significantly higher risk for developing heart disease or having a heart attack; a nine-year study of 12,000 men at high risk for coronary heart disease found that they were 32% more likely to die of a heart attack if they didn’t take an annual vacation (and were at a 21% higher risk of death from all causes). Relaxing is serious business. Be proactive in your vacation planning. Request time off at the beginning of the year instead of waiting to make a plan later. Otherwise, when “later” comes, you’ll again find yourself never leaving the office because you always feel like there is too much to get done. In 20 years, you’ll end up with a lot of “I always wanted to…” sentiments, instead of a treasure trove of “I’m so glad I did…” stories.

Neglecting your health: Getting enough sleep, eating healthy foods, and exercising regularly dramatically increases your happiness on a daily basis. And in 20 years you’ll feel a whole lot happier and be in a lot better shape. Avoiding trips to the hospital, medicine, surgery, and chronic pain helps you to savor life instead of simply trudging through it. Make the decision to builds habits now for exercise and a healthy lifestyle. A little time now can pay off huge dividends later in life.

Wasting time to save money: Saving money has its place, but many times spending a bit of extra money can save you hours in your day — and in many cases that time can be invested in activities that are most important to you. This could mean driving or taking a cab instead of booking a train because train travel would take three times as long. Or hiring a cleaning service to put your house in order or having groceries delivered, instead of spending the time and saving the expense to do it yourself. Or even choosing to live closer to work even though it’s more expensive because it saves you hours of time and frustration during your commute. In 20 years, you won’t miss the few extra dollars here and there, but you will miss the opportunity to live the life you wanted to live.

Never knowing yourself: In my experience, it’s so easy to lose track of who you are, what you enjoy, where you are in life, and where you’re going unless you purposely and intentionally take time to reflect. That could look like taking walks, journaling, praying, meditating, or simply staring at the ceiling for a while with no particular intention other than to be with yourself. In the end, if you never know who you are, it’s hard to feel really good about yourself.

These are just a few of the regrets I’ve seen that you can avoid by intentionally investing your time now. Not only will you end up with a more abundant and accomplished life in the future, but you’ll also really enjoy the present and feel good about what you do — and don’t — get done.

[image error]

February 12, 2015

City Governments Are Using Yelp to Tell You Where Not to Eat

Local governments are not known for being at the forefront of innovation and technology. That may be about to change.

Cities are beginning to see the value of using consumer-feedback sites to improve efficiency, provide citizens with important health data, and put pressure on unhygienic restaurants to clean up their acts.

Draw a dotted line to the future, and you can see how social media could transform citizens’ relationship with all sorts of governmental agencies and services.

Over the past year and a half, we have been developing algorithms and a disclosure platform to help local governments move in this direction. Progress has been incremental, but tech-friendly cities such as San Francisco and Raleigh, North Carolina (the heart of the Research Triangle) have demonstrated that digital and social technologies have the power to transform what used to be that most analog of processes, the disclosure and enforcement of public-health regulations.

Health departments typically send clipboard-toting inspectors to restaurants to check for things like improper food-storage temperatures and evidence of rodents. The worst violators are shut down, but the rest stay open, and each local government makes its own decisions about whether and how to inform citizens about inspection scores.

In some cities, letter grades from A to F are posted at restaurants for would-be diners to see. This can be effective: After such a policy was enacted in Los Angeles, restaurants improved their hygiene, and food-illness hospitalizations declined. In other regions, inspection results are more difficult to find — they’re posted in hard-to-notice places in restaurants or buried in municipal web sites.

But in recent years consumer-feedback platforms like TripAdvisor, Foursquare, and Chowhound have transformed the restaurant industry (as well as the hospitality industry), becoming important guides for consumers. Yelp has amassed about 67 million reviews in the last decade. So it’s logical to think that these platforms could transform hygiene awareness too — after all, people who contribute to review sites focus on some of the same things inspectors look for.

It turns out that one way user reviews can transform hygiene awareness is by helping health departments better utilize their resources. The deployment of inspectors is usually fairly random, which means time is often wasted on spot checks at clean, rule-abiding restaurants. Social media can help narrow the search for violators.

Within a given city or area, it’s possible to merge the entire history of Yelp reviews and ratings — some of which contain telltale words or phrases such as “dirty” and “made me sick” — with the history of hygiene violations and feed them into an algorithm that can predict the likelihood of finding problems at reviewed restaurants. Thus inspectors can be allocated more efficiently.

In San Francisco, for example, we broke restaurants into the top half and bottom half of hygiene scores. In a recent paper, one of us (Michael Luca, with coauthor Yejin Choi and her graduate students) showed that we could correctly classify more than 80% of restaurants into these two buckets using only Yelp text and ratings. In the next month, we plan to hold a contest on DrivenData to get even better algorithms to help cities out (we are jointly running the contest). Similar algorithms could be applied in any city and in other sorts of prediction tasks.

Another means for transforming hygiene awareness is through the sharing of health-department data with online review sites. The logic is simple: Diners should be informed about violations before they decide on a destination, rather than after.

Over the past two years, we have been working with cities to help them share inspection data with Yelp through an open-data standard that Yelp created in 2012 to encourage officials to put their information in places that are more useful to consumers. In San Francisco, Los Angeles, Raleigh, and Louisville, Kentucky, customers now see hygiene data alongside Yelp reviews. There’s evidence that users are starting to pay attention to this data — click-through rates are similar to those for other features on Yelp.

Digitizing inspection data raises difficult questions — What data should be displayed? How prominently? What is the right platform for displaying it? — but it also provides new opportunities for increasing knowledge. For example, Yelp can glean insights about restaurants’ and consumers’ responses to different types of disclosure. In one large city, we showed in a randomized, controlled trial that restaurants whose low hygiene ratings are posted on Yelp tend to respond by cleaning up and performing better on their next inspections.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, more than 48 million Americans per year become sick from food, and an estimated 75% of the outbreaks came from food prepared by caterers, delis, and restaurants. By partnering with social-media sites to provide digital disclosure, municipal officials can improve these numbers. They can also reduce costs and display information in ways that are easier for citizens to find and absorb.

And there’s no reason this type of data sharing should be limited to restaurant-inspection reports. Why not disclose data about dentists’ quality and regulatory compliance via Yelp? Why not use data from TripAdvisor to help spot bedbugs? Why not use Twitter to understand what citizens are concerned about, and what cities can do about it? Uses of social media data for policy, and widespread dissemination of official data through social media, have the potential to become important means of public accountability.

[image error]

Make Enterprise Software People Actually Love

There is a big, important change happening in digital product design. For a long time, there has been a clear split between business software (often called Enterprise or B2B), and consumer software (B2C, or simply “products”). That split is increasingly irrelevant.

As a product designer, I cut my teeth on enterprise software at Trilogy in Austin; we developed configuration tools for Ford and Nissan, pricing solutions for the insurance vertical, and supply-chain and selling management software for a host of different companies. This category of software is typically characterized as “feature-rich.” In fact, these products are sold as lists of features to C-suite executives, and the conventional wisdom over many years has been that the package with the most features wins. Unfortunately, the executive who signs the check rarely has to actually use the product he just bought, and so those features that look so good in a PowerPoint actually manifest as a mess of unusable complexity for the individual contributors in the company.

The other extreme of the digital product spectrum is consumer software, where the focus is on drop-dead simple products that provide a value-proposition related to emotions rather than features. At frog design, many of the products I worked on – HP Touchsmart, Microsoft Virtual Earth – were intended for regular people. Regular people have expectations related to ease of use, simplicity, and – most importantly – emotional attachment. When we bring products into our houses, we are implicitly expecting them to behave as we would want any person who enters our home to behave – with respect for how we live.

Of course, the joke here is that people in large companies are “regular people” too. Increasingly, these people have autonomy related to the tools they use in their jobs. We’ve all heard of the “consumerization of IT“: workers bringing their own devices, their own software, and their own expectations to the workplace and rejecting the overly complicated software provided by their employers. Consumerization, in this context, is not the dirty word of consumption; rather, it refers to power of choice and autonomy of control. As we see more and more productivity tools emerge that are simple and easy to use, we’ll continue to see more individual business units reject massive tools like SAP and PeopleSoft for tiny tools like Harvest, Basecamp, or Smartsheet.

I’m in the middle of this enterprise-to-consumer shift at Blackboard, where we’ve had extraordinary success in the education-technology space by selling features to administrators or CIOs. But, analogous to the consumerization of IT, there is also consumerization of education going on. Students are increasingly empowered to choose alternative educational models, alternative places to learn, and alternative technology solutions to support their education. Blackboard recognizes this shift, and that’s one of the reasons they acquired the startup where I worked previously, MyEdu – a free product focused on helping college students succeed in college and get jobs. Our ethos: instead of focusing exclusively on selling software to giant companies, we need to rally around free tools that students can elect to work with; instead of “monetizing students” or “selling features,” we need to monetize products that minimize attrition, support the complexity of the academic journey, and help students find a vocation that they enjoy and in which they can grow. This is a product ethos built around emotional impact and attachment.

But saying and believing in these words, no matter how passionately, does not shift a giant company. Here are some of the ideas and practices that have helped me and my colleagues begin to make what will probably be a hard, years-long journey to recast our focus on learners, and to reposition our software as a great consumer product.

Show an alternative. No matter how well-intentioned, a company can’t get on board with a vision without actually seeing it. The best way to socialize a trajectory change is to show it, in detail, and in a way that the organization can understand. The designers at Blackboard began creating visually persuasive demos, prototypes, and vignettes of a path forward before the path was even crystalized. For example, Blackboard used animated visuals (a few of which are pictured below) to help rally people around an alternative vision of the future without worrying about requirements or legacy product issues.

Ground the design in emotional research. Rather than supporting an emotional shift from enterprise to consumer with market research, I’ve found it effective to illustrate the value through qualitative, ethnographic research. We spend time with students, teachers, and parents, and leverage the findings to both substantiate new design direction and to help humanize the shift. The best tools? Quotes, images, and video snippets of real people describing their job, life, and emotions.

Relentlessly beat the drum of experience over function. If enterprise software is characterized as “more,” consumer software is characterized as “less,” with a focus on the emotional quality of engagement rather than a breadth of robust functionality. I know from my own experience that it can be tedious to constantly remind, evangelize, and describe that this is important, and why it is important – but it is also critical to success.

Describe an incremental path towards success. The change from features to emotion – in mindset and in operation – doesn’t happen overnight, and while the alternative visualizations paint an ideal picture of the future, the reality is often more convoluted. A change like this requires re-examining and rationalizing multiple technology platforms, existing legal agreements, and entrenched perspectives. The organization needs to see an incremental path towards simple, emotionally engaging products, one that describes small steps forward towards a big vision. It’s not enough for us to say where we are going; we need to say how we intend to get there, too. This means creating a visual road map that shows a thoughtful parsing-out and bringing-down-to-earth of the vision to something achievable; it shows small wins over time.

Our own shift at Blackboard is only one of hundreds occurring in education, healthcare, banking, and in nearly every sector and part of life. Our society is realizing that technological advancement is strange, and we need to humanize it to make it familiar. This humanization comes through a shift from features to emotions, resulting in simple, well-designed products that people love to use.

[image error]

Identify Blue Oceans by Mapping Your Product Portfolio

This past quarter Apple once again crushed its earnings report. This despite Wall Street’s uncertainty since the death of the company’s founder and visionary, Steve Jobs. How has Apple managed to maintain its stock price and convince investors of its growth potential?

Consider the recent history of Apple and Microsoft, two tech companies no longer run by their visionary founders, and how each has competed in red or blue oceans. Over the last fifteen years Apple has made a series of successful market-creating—or blue ocean—moves (think the iMac, iPod, iTunes, the iPhone, the App Store, and the iPad). From the 2001 launch of the iPod to the fiscal year end of 2014, Apple’s market cap surged more than 75-fold as its sales and profits exploded. Over the same period, Microsoft’s market cap crept up a mere 3 percent while its revenue went from being nearly five times larger than Apple’s to nearly half its size. Two old businesses—Windows and Office—account for close to 80% of the company’s profits. While the products might bring in steady revenues, the lack of any compelling market-creating offering has left Microsoft with a red-ocean heavy product portfolio—for which the company has paid a steep price.

The truth is too many companies are paying a similarly steep price. In studying more than 100 new business launches we found that 86 percent of what companies classified as new business launches were effectively market-competing moves. That is, incremental improvements in existing market space, like a pasta company introducing a new line of gluten-free pasta. This 86% of market-competing moves, however, generated only 62 percent of combined launch revenues and 39 percent of profits. By contrast, the remaining 14 percent of launches—those that created markets or recreated existing ones—generated 38 percent of revenues and a whopping 61 percent of profits. In other words, blue oceans offer the real potential for future profitable growth.

The challenge for all companies, Apple included, is how to continue investing in existing revenue-generating businesses while at the same time creating and launching the businesses of tomorrow.

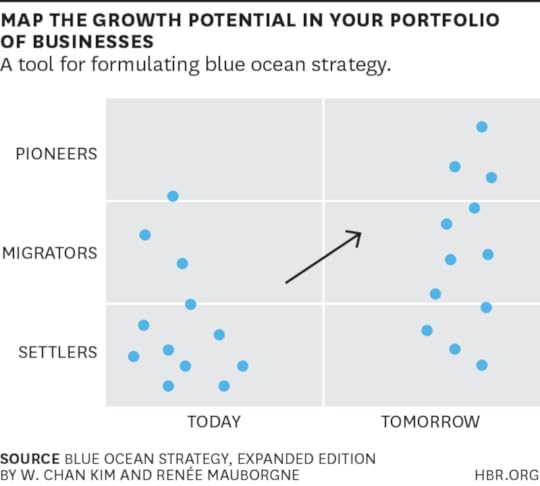

We developed an analytic tool—the Pioneer-Migrator-Settler Map—to address precisely that challenge and, as we discuss in the new Blue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition, its beauty is that it can be applied dynamically over time to shift the trajectory of a company’s profitable growth prospects.

The Map allows you to see in one simple picture what your current portfolio of businesses says about your future growth prospects and indicates how you should drive your company to lift your prospects over time. On the Map, settlers are businesses offering me-too value; migrators are businesses with value improvements over competitors'; and pioneers are businesses that offer unprecedented value—these are your blue ocean offerings. The key, for any successful organization, is to maintain a balanced portfolio of pioneers, migrators and settlers—or, put another way, of red and blue oceans, even as once pioneers get imitated.

Consider Apple, mapped in the chart below. In 1997, Apple could boast just one migrator (the Macintosh) and a handful of settler peripherals and services. And the company’s future hung in question. The Map shows a very different picture in 2003, with the addition of two pioneers (iPod and iTunes), and the Macintosh now lifted to high migrator status with Apple’s launch in 1998 of the iMac—the first colorful, friendly desktop computer that made it easy to connect to the internet. As shown on the Map, by 2008, as the iPod was eventually imitated and sank toward the migrator category, the company reached out and launched its next blue oceans, the iPhone and App store. Then as the iPhone and iTunes store fall into the migrator category, the company introduces the iPad. In other words, Apple has maximized growth prospects by maintaining a healthy balance of pioneers, migrators, and settlers over time, even as the businesses that fell into each category shifted with competition.

As the dynamic Map also makes clear, Apple is not only about blue oceans; nor should any company’s corporate portfolio be. Companies with a diverse portfolio of businesses, such as Apple, General Electric, Johnson & Johnson, or Procter & Gamble, will always need to swim in both red and blue oceans and succeed in both oceans at the corporate level. Once Apple’s iPod began to be imitated, for example, to counter competition it rapidly launched a range of iPod variants at various price points with the iPod mini, shuffle, nano, touch, and so on. This not only served to keep encroaching competitors at arm’s length, but also expanded the size of the ocean it created, allowing Apple, not imitators, to capture the lion’s share of the profit and growth of this new market space. By the time the iPod’s blue ocean became crowded with more imitators, Apple had created another blue ocean by introducing the iPhone.

The challenge for Apple in going forward is to continue to renew its portfolio, as current pioneers eventually become migrators and settlers, so that it can maintain a healthy balance between the profit of today and the growth of tomorrow.

This is the precise challenge Microsoft has been facing for nearly a decade. Despite relatively strong profit, Microsoft has failed to maintain a healthy balance across pioneers, migrators, and settlers. For Microsoft to get out of its slump, it needs to work toward creating a better balanced portfolio across businesses that not only compete in red oceans but also create blue oceans, which renew, expand, and build its leading-edge brand value.

The question for executives is: If you were to plot your portfolio of businesses on the map how would it fall? Is your portfolio settler-heavy—as is the case with a majority of declining companies? Has a business that was in the past a pioneer, generating huge profit and growth, become a settler, suggesting that the company’s growth is likely to be slow without the introduction of a new pioneer? Or is your portfolio well–balanced, ensuring current cash flow and strong upside profitable growth potential?

Forward-thinking executives understand that the real business they are in is not cosmetics or foods or chemicals or computers. It is the business of creating. Only sustained creation will sustain compelling profitable growth. The question is: How much of your organization’s time and talent is lined up behind building pioneers versus managing settlers?

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers