Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1323

February 5, 2015

The Ambitious Business Goals Aiming to Change the World

Sam Walton once said, “High expectations are the key to everything.” An increasing number of companies — particularly in the auto industry — are heeding that call, setting aggressive, creative, and visionary goals that change their approach to business and how they relate to the wider world.

Consider Nissan’s “Vision Zero” which aims for “zero traffic accidents involving Nissan vehicles that inflict serious or fatal injuries,” according to COO Toshiyuki Shiga. A broad, seemingly impossible systemic goal like this might seem like a social responsibility or public relations strategy — and of course it has those elements. And I’m sure some corporate lawyers aren’t exactly thrilled, since it’s hardly only the car company’s issue – we all have an individual responsibility to drive safely, too. But Nissan is, I think, ignoring the risk-averse nature of our normal business culture and putting itself out there.

It’s brave. But it’s also very good for the business.

In order for Nissan to actually pursue the Vision Zero goal, the company is forced to think differently about innovation and product development, developing technologies that keep cars from hitting each other. But since there’s no way Nissan could address the goal solely through its products, it also propels creativity in marketing in order to change how all of us drive. The company’s “Red Thumb” campaign encourages people to wear a red band to remind them not to text and drive, and they’re using some star power, with Maroon 5 front man Adam Levine and the popular show The Voice to raise awareness.

Rethinking products and how you talk to your customers at the same time is systemic thinking at its best.

Nissan is not alone in setting big goals. My firm has collected 4,000 environmental and social targets set by the world’s largest 300 companies. A surprising number reach for deep changes in the world, going well beyond the expected and narrower kind of goals like “reduce energy use 10%.” Just within the auto and transportation industries, a few goals stand out:

Honda: Bring well-to-wheel CO2 emissions down to zero.

Deutsche Bahn: Achieve rail transport that is CO2-free and powered by renewables.

Maersk: Safely recycle all their ships at the end of their service life.

These systemic goals have enormous repercussions for the companies and their value chains. How can Honda influence the emissions profile of oil production or move away from oil burning vehicles entirely? How will trains run on renewables without some deep investment by utilities and European governments? What kind of reverse logistics and markets for recycled materials does Maersk need in place before it can recycle ships that are now larger than the Empire State Building?

These are meaty questions that go to the core of what these businesses do. And they take into account the stark realities of a world dealing with resource constraints, climate change, and other mega challenges. These are the kinds of goals that bring about a big pivot in how business runs.

Importantly, this pivot is not just about arbitrary visionary goals, but ones based on the reality of the challenges we face – that is, based on science. Ford Motor, for example, has used “science-based CO2 targets” to shape its product development plans for 10 years. The company has been developing vehicles that help the world meet its carbon reduction goals, including most prominently the 2015 F-150 truck. Ford made this vehicle, its top-selling brand, 700 pounds lighter by shifting from steel to aluminum. The Automotive Science Group just named the F-150 the best large truck on environmental and economic performance (a lighter truck also saves the driver money on fuel).

Even tactical operational goals can be transformative. GM wanted 100 landfill-free (“zero waste”) manufacturing sites by 2020. The company has already surpassed this target as part of its larger goal, to be “the leading auto-maker in waste reduction.” Managing its waste, which once cost GM billions of dollars a year, now makes the company more than $1 billion annually.

Automakers are not the only ones setting visionary targets. Consider a few more:

Unilever wants to halve its greenhouse gas impact of its products across the product lifecycle by 2020.

Coca-Cola will “replenish” 100% of the water used by 2020 (and Diageo just set a similar goal).

Walmart will eliminate landfill waste from U.S. stores and Sam’s Club by 2025 (and actually, 39 of the Fortune 200 have zero landfill goals).

Biotech firm Novozymes plans to “deliver 10 transformative innovations…and save 100 million tons of CO2through the use of its products by 2020.”

French utility EDF wants to “ensure equal pay for female employees.”

These targets set a high bar for both business and society. Coca-Cola depends on water resources for its products. Unilever believes that increasingly aware and concerned consumers will buy more of its sustainable products. And won’t EDF attract the best talent by compensating women better? And for Nissan, the company recognizes that a brand known for safety will certainly attract buyers.

The leading large companies seem to be realizing that their size gives them great influence over the world and creates unusual opportunities to tackle big issues. By setting big, visionary, science-based goals these companies are taking on a larger role in the world, creating new levels of performance, creativity, and business value.

[image error]

February 4, 2015

Your Data Should Be Faster, Not Just Bigger

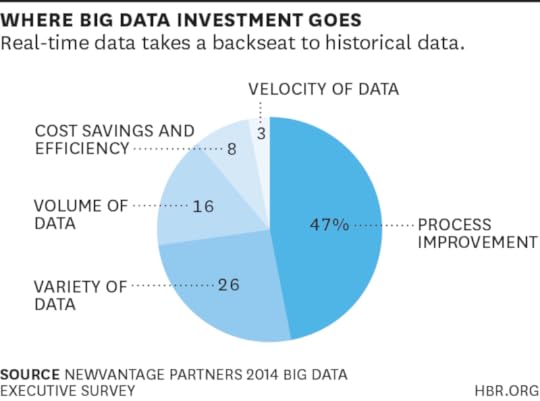

It’s universally acknowledged that Big Data is now a fact of life, but while large enterprises have spent heavily on managing large volumes and disparate varieties of data for analytical purposes, they have devoted far less to managing high velocity data. That’s a problem, because high velocity data provides the basis for real-time interaction and often serves as an early-warning system for potential problems and systemic malfunctions.

Moreover, data proliferation has been accelerating. EMC recently reported that data volumes can be expected to double every two years, with the greatest growth coming from the vast amounts of new data being produced by intelligent devices and sensors. Oracle president Mark Hurd has predicted that the number of devices connected to the Internet will grow from 9 billion to 50 billion by the end of this decade.

What makes device data, sensor data, and other forms of “fast data” distinctive is that, unlike historical data, it is live, interactive, automatically generated, and often self-correcting. Historical data is used to identify patterns that inform future decision-making, while fast data is designed for real-time decisions and real-time responses. Think of fast data as the continuous processing of events and data in order to gain instantaneous insight and take instantaneous action.

While fast data is not really new, it has been largely restricted to a couple of high-value uses: complex event processing (CEP) activities that operate on event streams, examples of which include algorithmic trading and fraud monitoring in financial services; and event correlation, which includes the systems that monitor and manage complex industrial components such as jet engines.

So, what has changed? First, the explosion of fast data has driven the demand for instant action. Second, innovators in social media and services like Uber have shown that businesses can be differentiated based on their ability to act on data instantly. Uber knows where you are, where you’re going, and how you will pay to get there because it can capture, analyze, and act on data in real time. The availability of lower-cost memory is making fast data accessible for a broader set of applications, including:

First responder systems that rely on integrating fast response data collection and analysis

Network usage systems that respond instantly based on traffic patterns

Customer-experience management systems that analyze vast amount of behavioral data in real time to tailor interactions and support self-service

Organizations that know how to use fast data will be more nimble, adaptive, and competitive. What can companies do differently to prepare for the opportunities created by high-velocity data? Here are a couple of suggestions:

Automate decision-making to increase customer engagement. Monitor customer activities to identify—and respond to—patterns, thresholds, and triggers. One major retailer is seeking to engage with customers in real time while they are online, but is hampered by traditional systems and batch processing environments. They are now creating an environment that marries customer and inventory data with streaming data so they can, for example, report to the customer whether a product is in stock and address any inventory gaps immediately.

Integrate machine-generated data to personalize interactions. EMC projects that soon nearly two-thirds of all data will be generated by machines, not people. That presents a technical challenge: how can companies capture and analyze many flows of data concurrently? The good news is that next-generation data systems that prioritize real-time data are in the early stages of adoption. By integrating new sources of machine-generated data, and combining it with traditional data sources, firms can further personalize their customer interactions. Ericsson, the mobile broadband company, has developed real-time visibility into its system performance, using device and user data as it is generated. This enables Ericsson to identify and improve slow performance as needed and to serve customers with programming tailored to them.

Firms that take these steps now will be well positioned to improve their operations and better serve their customers using high-speed data.

[image error]

We Shouldn’t Be Dazzled by Apple’s Earnings Report

Apple’s record Q1 earnings report may have led some consumers to believe that the “old” Apple is back. And the world wants that Apple back. We want the Apple that revolutionized industries and communication in the last decade.

But does the fact that it earned more money in one quarter than any company in history mean that our beloved Apple is alive and well? A look at the bigger picture within which these numbers sit suggests an alternate view.

To see that larger picture, let’s locate Apple within its larger context as a once disruptive innovator that’s now essentially an incumbent.

A fundamental tenet of disruptive innovation is that established firms normally do not react to disruptors. And for a good reason. Generally, disruptors take over the least profitable customers of the industry, and as that happens, established firms usually redirect the resources they might have spent defending their low-value consumers toward their high-value consumers. For instance, when Dell started its upmarket march, Hewlett-Packard’s executives weren’t too concerned. They considered HP to be too premium a brand to justify investing resources in defending the low end. When Southwest Airlines started to occupy the same market space as established air carriers, the incumbents predictably focused more on business class and international routes. When Curves (a gym that specialized in women) started to grow, established chains didn’t see it as competition. When online banks first started to appear, retail banks did not consider them as “real banks.” Insurance companies initially neglected selling insurance by phone and later online.

One of the most common misunderstandings about disruptive innovation is thinking that incumbents are either blind to the opportunity disruptors are creating or they are deliberately choosing to ignore it. It’s more accurate to say that they see it, but are unable to adopt the disruptor’s business model for some reason. Established insurance companies, for instance, had difficulty selling direct to customers over the internet because they could not risk alienating their own agents (and, worse, the independent brokers) who stood between them and their customers.

But not reacting at the business model level does not mean failing to react at the technological level. Very often incumbents do adopt a disruptor’s technology if it serves their best customers. For instance, HP did try (and succeeded, for a time) at selling PCs online. Established airlines adopted many of the technologies of disruptors, including online reservation, fleet optimization, and internal management practices. Established gyms launched their own version of programs for women.

In many cases, what is gold for the disruptor is only the cost of doing business for an incumbent, which can now serve its best customers better — even if it does not earn much in the way of additional revenue or profits. Many banks, for instance, now offer the convenience of online banking, but they still rely on branches to bring in new customers.

But there are the cases when new technology helps incumbents better monetize their premium customers. One such example is the smartphone’s screen size.

In a smartphone market that is growing at a healthy rate of over 25%, data indicates that Apple had lost 2% of market share in the last three years. This loss of market share came from new customers that chose other brands and, even more importantly, from former Apple customers who defected because of frustration over a particular feature: screen size. By launching the iPhone 6, Apple has regained a portion of these customers, as well as an additional share of new customers, who now can compare different phones without screen size being an issue.

So at a strategic level, what Apple has done is what incumbents usually do: adopt a disruptor’s technology (Samsung’s and Xiaomi’s, mainly) to sell more to its premium customers. The astounding results are explained in large part by the power of its scale – the reach of Apple’s mighty marketing capability and its capacity to manufacture a large number of phones, admittedly the result of good, traditional management by CEO Tim Cook. (Consider that Apple sold 74.4 million phones in Q1 alone, while Xiaomi cannot produce 70 million phones in an entire year.) And as disruption theory predicts, it is rumored that Apple is already thinking about implementing new screen sizes in other products, most notably the iPad.

Despite these record numbers, though, the process of disruption continues. Xiaomi and other disruptors still eat away at the low end with business models that are capable of monetizing their products much more effectively than Apple.

But one thing has changed. Apple used to revolutionize industries, announcing record sales numbers because it had introduced a new technology, feature, or product that we had never imagined but that, when we saw it, we all instantly wanted. That Apple seems no longer present. In this instance, all Apple has done is copy a feature for its own best customers. While that’s very effective for today, it does not solve the problem of tomorrow for a company that competes on serial innovation.

But even more fundamentally, this is not the Apple that we want or need. We, as loyal customers, believe Apple exists to revolutionize industries (and in the process earn a ton of money). Announcing boatloads of money, as if that were point, makes us think Apple no longer has the vision to keep on revolutionizing. It makes us think that it can no longer do what it did before — which is to tell us what comes next.

What’s more, by dazzling us with dollars, it seems that Apple’s leaders are deliberately trying to divert our attention. By making such a communication effort to let us know how much money they’ve made — instead of what they’ve done to change the world recently — they are inevitable forcing us to ask ourselves, is this what we get from the new Apple?

[image error]

McDonald’s and the Challenges of a Modern Supply Chain

Recently, McDonald’s, the world’s iconic largest food service provider, has been (forgive the cliché) through the grinder. Poor performance has led to the departure of its CEO and plenty of critical attention in the business pages. Part of this story relates to the provenance, or origins, of its products: Chains that provide more upmarket “fast casual” dining such as Panera, Chipotle, and Shake Shack have brands that speak of freshness, health, and trustworthy sourcing.

In 2010, I wrote an HBR article predicting increased interest in supply-chain transparency: firms needed to develop strategies for knowing and explaining where stuff comes from. Since then the idea of product provenance has steadily crept up the corporate agenda and is now a compulsory issue for boards and governments. In the UK, for example, legislation is in progress that would build on the California Supply Chain Transparency Act, potentially applying to wider range of firms. Across Europe, the 2013 horsemeat scandal generated widespread panic about contaminated meat. In a wide range of industries — electronics, software, toys, aerospace — provenance is increasingly a critical concern.

McDonald’s woes offers three lessons for others about supply-chain transparency.

Transparency needs a long game; reputational problems don’t mend fast. Few firms have faced such reputational challenges as McDonald’s. In the 1990s, an ill-judged legal case, the McLibel trial, saw the corporation acting against a tiny environmental group in one of the longest civil cases in UK history, with terrible reputational consequences. The movies Super Size Me and Fast Food Nation cemented the view that the corporation was complicit in promoting bad health, bad environmental practice, and food that was just, well, disgusting.

Faced with these challenges, McDonald’s has not been idle. It has taken on its critics and made substantial changes to both its practices and its communication. Indeed, in the UK, the official government review of the horsemeat scandal, the Elliot Review, singles out the McDonald’s supply chain for praise. In the United States, a series of documentary-style promo films with celebrity presenter Grant Imahara have tried to give customers a clear and unvarnished account of sourcing and production processes. You may still not like the firm or its products, but you can’t deny it has made serious efforts.

The trouble is bad reputations aren’t lost that easily. A generation of cynical middle-class customers have already decided that McDonald’s is a tarnished brand. Supply-chain transparency is that kind of challenge: It’s rarely the top thing on consumers’ minds, but it is an issue that sticks in the imagination. And when newer, less tarnished players like Chipotle arrive, consumers can tacitly exercise the prejudices and cross the street. The lesson for other firms: If you have problems in your supply chain, don’t let the critics get there first.

Global operations need consistent global standards. Despite the great strides that McDonald’s has made in some markets, its progress and practices have not been uniform. Last year McDonalds — and other major food companies — were plunged into a food safety scandal in China. This is a case of your defense being as strong as your weakest point. Bad headlines about foreign operations tell consumers, “This company still can’t be trusted.” And such bad news doesn’t just reduce the impact of your good work elsewhere; it means that its credibility is fundamentally undermined. So firms need to be cautioned: Supply-chain transparency initiatives are not a normal program to be rolled out region by region.

Sometimes transparency has paradoxical consequences. Let’s return to those videos with Grant Imahara. “Look,” they declare, “it’s real wholesome meat!” Imahara holds up great chunks of flesh from the conveyor as if to say, “Appetizing!” But even hard-core carnivores like me blanch queasily at this amount of dead animal. OK, you’ve convinced me there is no pink slime, but you’ve reminded me that this whole process is kind of horrific. That’s one of the curses of transparency of provenance: I might now approve of your food-safety practices, but you’ve just reminded me of things that, deep down, I don’t want to know. This is a paradox that firms in a wide range of industries will inevitably need to grapple with. (Question: What does an unethical shirt factory look like to a naïve consumer? Answer: Appalling. Question: What does an ethical shirt factory look like? Answer: In truth, still pretty appalling.)

It may be that McDonald’s future lies in yet further reinvention of the brand. The Corner, one of its experiments, is a “McCafé” that looks and feels nothing like a McDonald’s restaurant. But even then, the provenance agenda is not going away: The new CEO (who holds an honorary visiting position at Oxford’s Saïd Business School, where I teach) will need to tough out the current problems and stick to the mission of ever-greater openness.

[image error]

February 3, 2015

Staying Motivated After a Major Achievement

In 1993, after leading his country to an Olympic gold medal, winning his third NBA championship, and scoring more points than any player in the league for a seventh consecutive season, Michael Jordan announced his retirement from basketball. He was 30 years old.

“I just needed to change,” Jordan would later recount. The regular season was just weeks away and he was finding it impossible to get motivated. “I was getting tired of the same old activity and routine and I didn’t feel all the same appreciation that I had felt before and it was tiresome.”

Jordan’s sentiments were recently echoed by another prominent high achiever. In a November interview with NPR’s Terry Gross, Jon Stewart made the following remark about returning to the routine of The Daily Show after directing his first film. “I don’t know that there will ever be anything that I will ever be as well suited for as this show,” said Stewart, whose contract to host the show expires later this year. “That being said, I think there are moments when you realize that that’s not enough anymore, or that maybe it’s time for some discomfort.”

Many of us have experienced some of the same feelings after completing a major project, or winning a big sale, or making a crucial presentation to the board. For months or weeks you were ruthlessly focused on a single, herculean undertaking. And then inevitably, that assignment is done.

When we think about achieving a major goal, we picture the exhilaration of reaching new heights. What we often fail to anticipate, however, is that once we’ve scaled that mountain, it can be surprisingly chilly on the other side. After a period of massive productivity we have to revert back to life as usual and settle back into an established workplace routine.

It’s a lot harder than it looks.

For one thing, it’s because of the emotional letdown of going from an exciting, challenging, or pressure-filled situation to one that’s considerably less demanding. High-stress situations and the adrenaline rush they produce can be addictive. When the constant sense of urgency we’ve adapted to comes to an abrupt halt, we experience withdrawal.

In many cases, reverting back to a predictable routine also means the work is no longer as stimulating. To be fully engaged, we need to experience an ongoing sense of growth on the job. At no point is the gap between rapid learning and intolerable stagnation more prominent than after a period of intense professional development.

But perhaps the biggest reason we have a hard time motivating ourselves after a major success is that we fail to recognize the symptoms of burnout.

Mastering new challenges involves an outpouring of mental, emotional, and physical effort. Sustaining that effort over an extended period of time depletes your energy. Burnout can happen when the amount of energy required consistently exceeds the amount of energy you have available.

But here’s the thing we often miss: unlike exhaustion, burnout can be surprisingly hard to detect. You won’t find any glaring markers. The symptoms are subtle. You might notice yourself taking a few extra minutes in the morning to get out of bed. Or delaying important decisions. Or feeling a bit more cynical about your job.

Even mental health experts whose job it is to identify these symptoms struggle recognizing their own burnout. In part, it’s because of this unfortunate fact: burnout damages your ability to recognize the symptoms of burnout.

We’re all susceptible to burnout, especially in the wake of tackling difficult challenges. That doesn’t mean, however, that inefficiency, cynicism, and procrastination must necessarily follow every major success. Here are some adjustments worth considering the next time you transition from a big win back to your normal routine.

Recognize that your job is about to get more difficult. A common mistake we make after succeeding at a major challenge is having unrealistic expectations about the work that follows. After a major outpouring of effort, your energy stock is likely to be depleted, which makes it hard to maintain your concentration. Tasks that may have required little exertion in the past suddenly demand a lot more of you. Adjusting your expectations is important because it helps minimize the self-blame that often accompanies and exacerbates burnout.

Separate thinking from doing. If your job is like most, it’s rare for you to have the opportunity to savor your successes for very long. In fact, there’s probably an enormous backlog of work that accumulated while you were seeing your project out the door, because the rest of your job didn’t stand still during that time.

While you may feel tempted to immediately dive in, doing so is generally not in your best interest. When we’re depleted we find it harder to distinguish tasks that are important from those that simply feel urgent. It’s at this point that we’re at our most vulnerable to doing busywork.

Carve out a few hours outside of the office to list, clarify, and prioritize your tasks. A focused strategy session will help declutter your mind and ensure that you devote the limited energy you have to activities that have value. The sense of direction is itself energizing, while preventing you from falling prey to easily-accomplishable tasks with limited worth.

Unapologetically restock your energy. To achieve top performance the human body requires periods of recovery. Laboring when our physical and cognitive resources are depleted yields low quality work and makes engagement more difficult.

When taking extended time off after a big win is not an option, integrating recovery into your day is especially valuable. Schedule intermissions onto your calendar and use them to take a walk. Have lunch away from your computer. For a few days, turn off your work email after hours, or better yet, when you arrive home, leave your phone in a different room.

What should you do at home to replenish your energy? A 2014 Journal of Occupation Health Psychology article offers clues. Within the study, psychologists compared how different after-work activities affect employees’ recovery from burnout. While many of us assume that passive, relaxing activities are best, researchers found evidence that engaging in exercise and social interaction can be even more revitalizing.

The lesson: slowing down isn’t the only way of filling up your tank. Sometimes renewal requires accelerating in a different direction. Instead of just flipping on the TV and vegging out, consider calling your friends and suggesting a game of tennis.

Find your next mastery goal. To be at our most engaged, we require experiences that grow our competence. Leadership consultant Jim Collins argues that organizations need a “big hairy audacious goal” to achieve great things. The same can be said for employees.

If you’re aiming to perform at your best, you need something new to be excited about. Building time into your routine to explore new ideas, for example, by reading before work or setting aside 15 minutes after lunch to review industry blogs, helps foster a sense of growth even when the tasks you’re working on are predictable.

Another method of growing on the job: mentoring. We tend to think of mentoring as a means of educating others and improving their performance. But new studies indicate that in many cases, it’s the mentor who reaps the greatest benefit, especially when it comes to mitigating perceptions of having reached a “career plateau.”

How does mentoring help? Research suggests mentoring prevents job monotony and enhances the way we look at our jobs. It contributes to the perceived meaning we derive from our work. In so doing, mentoring helps us find growth in new ways, mitigating emotional exhaustion.

Ultimately, how you approach your work in the days and weeks following a big win can be just as critical to your long-term success as the achievement itself. By anticipating and proactively addressing a depleted mental and physical state, you’re more apt to turn an isolated victory into a consistent winning streak.

[image error]

A Simple Way to Measure How Much Customers Love Your Brand

How do you measure love? Beyond the supermarket magazine or social media “quiz” that we’ve probably all taken, you really can’t. It’s a feeling. You just know.

But when thinking about a brand’s relationship with consumers, the marketer in me needs something more concrete. I need to know how many of my consumers are in love with my brand and the degree of their passion. To try and measure that emotion, I use a “Brand Passion Score” that ultimately shows how in love a consumer is with the brand, and more importantly, why.

To come up with your own scoring system, first talk to consumers and interview them about their affection for a series of brands, not just your own brand. In my experience, there are a few components to measure. These then build up to an overall Brand Passion Score, which provides a reliable measurement of consumer love for the brand. Often this can simply be in the form of an “agree/disagree” seven-point scale (strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, neither agree or disagree, somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree.)

While not an exhaustive list, here are three of the most effective statements that I’ve found to measure a consumer’s passion for a brand.

X is a brand for me. These are very powerful words. They immediately personalize the brand-consumer relationship. It becomes all about the brand understanding that the consumer is special, and the consumer feeling like the brand really has been designed for them. This creates a strong bond; in my experience, no one measure correlates more to future purchase intent than “is a brand for me.”

X is a brand I can trust. If a brand scores high on this measure, it has proven to the consumer that it has his or her best interests in mind. In our cynical society, it is becoming more difficult to achieve high scores for this measure. Brands that do have earned a special place in the consumer’s heart – the consumer genuinely believes that this brand will take care of them.

X is a brand I enjoy introducing other people to. In your own relationship history, do you remember when you first met “the one?” Did you want to keep it to yourself? Of course not! You wanted to tell the world! The same thing is true for consumers and brands. If a consumer is truly in love with a brand, they want to share that with those most important to them – their friends and families. Not only is it a great measure of brand passion, but marketers can also track the influence of consumers whose referrals are most influential.

How can you use the Brand Passion Score to grow your business? For starters, I see four immediate ways:

It serves as a critical variable in measuring our brand’s overall health. When taken in context with other brand health variables (sales, share, etc), such a score can let us see what’s driving our brand’s successes (or failures). If the score is relatively high and sales are low, there is an execution problem. If sales are high and the score is relatively low, we are either seen as a commodity and have no brand or are “buying” our volume through promotions and discounts — neither of which is optimal.

It helps us discover our brand’s relationship strengths and weaknesses. If you compare the components of our Brand Passion Score with each other, you immediate get insight into where your brand’s strengths and weaknesses are and, ultimately, where you should be focusing your marketing efforts. Maybe your brand is strong in consumption measures but weaker in word of mouth. If it is important for your brand to have a strong word-of-mouth presence, then clearly you know that you need to emphasize instances in which consumers want to introduce or share the brand with others in a social setting.

It helps us discover how our brand’s relationship is progressing over time. Implementing an ongoing, trended Brand Passion Score can help you identify when and where a relationship may be going off track — well before traditional market or consumer measures may indicate as much. Think of it as preventive medicine for the brand/consumer relationship.

It helps us benchmark against competitors. A critical factor is to compare our score with that of our competitors. Where do we have an edge in our relationships and where do they have an edge? We may even go beyond our category and look at “best in class” brands. These benchmarks will 1) clarify whether other competitors are doing something that is significantly increasing or decreasing their score or 2) reveal whether our brand may be facing potential problems bubbling under the surface that our competitors and best in class brands are not.

In summary, while we haven’t quite yet figured out a way to quantitatively measure the passion in our personal relationships, we do have the ability to use a relatively simple metric to monitor the strength of the relationships between consumers and our brands and ultimately make ourselves better marketers.

[image error]

Managing Your Professional Identity During a Gender Change

It can be complicated to change your name after getting married. With multiple social media accounts and years of Google search results behind you, it’s often a fraught transition for your personal brand, as I’ve . Jess Samuels, who wed in 2013 and took her husband’s name, wrote a about the logistics, including helpful tips like using the website Knowem, which allows you to check whether your preferred new username is available on various networks.

But if it’s challenging to change your name in the Internet era, it’s even more complicated to change your name and your gender—a situation faced by Jess’s now-husband, Robbie Samuels, when he came out as transgender a decade earlier.

Robbie, whom I profile in my forthcoming book Stand Out, has a two-decade history of professional activism. “Some of my biggest accomplishments in my 20s are still tied to my birth name online,” he said. “I was bummed to lose this online history when I began to use a new name.” But coming out as transgender doesn’t mean you have to give up entirely on your past. Here are three strategies to help you tap into the full power of your personal brand:

Create a team of ambassadors. When Chris Edwards came out as transgender in 1995, he was a young creative executive at an ad agency. “I actually used what I learned from working in advertising to rebrand myself,” he says. Inspired by “evangelism marketing,” in which others spread the word about a product via word-of-mouth, he recruited 12 of his closest friends in various departments at the agency. “Since they would be acting as my brand ambassadors, I really took the time to explain what I was going through, educate them, and then coach them on how to tell others,” he recalls. “I asked them to keep it quiet until after I told the Executive Board. I wanted to be respectful to upper management—it was important that they hear it from me first, and not find out via the gossip mill.” He told leadership one evening at 5 PM, and “then gave my 12 evangelists the green light to start spreading the word. By 11 AM the next morning, my whole agency knew, and by that afternoon, all the other agencies in town knew.” Instead of a long and drawn-out coming out process, Edwards took care of it quickly and controlled the narrative by ensuring that his personally chosen allies spread the word.

Connect your past and present strategically. In an era where we’re constantly recorded and tracked (you can probably find clippings from your high school newspaper online), how do you connect your past identity with the one you’re moving into? As with those getting married, you’ll need to either open up new social media accounts or (where possible and desirable) change your name on existing ones. To counteract the loss of search engine results for your past professional accomplishments, it also pays to double down on your social media presence under your new name.

Some professionals—particularly those who transition later in their careers—may want to follow the example of astronomer Jessica Mink, who came out at 60. “I simply claimed all of my past accomplishments without saying anything about the change, except through a single, vaguely-worded link,” she says. Where questions may arise online, she links to this explanatory page, which begins, “I have not always had the same name and appearance. Here’s why.” She adds, “I’m also ready to answer questions from anybody who asks, which seems to help.” As Edwards notes, other people will treat your transition as less of a big deal if you frame it as a rebranding. “You’re not trying to hide your past; you’re simply evolving from it,” he says. “If there are no juicy secrets for people to uncover, then who cares?”

Embrace the advantages of your new brand. Every transition comes with benefits and drawbacks, and changing gender is no different. The disadvantages of coming out as transgender, such as the lack of legal protection against job discrimination in 32 states, are well known. But if you really want to own your brand, you have to embrace the positive elements.

Chris Edwards, who rose to one of the top positions at his advertising agency, believes that his transition actually set him up for success. He notes, “I was more comfortable in my own skin, which made me more confident, which in turn made me speak up more in meetings and be considered more of a leader.” Mink, a noted astronomer who helped discover the rings of Uranus in 1977, discovered her new ability to make a feminist mark. “This fall, I found myself as the only woman author out of eight on a paper, and it took me a while to realize that it was significant that the only woman was the lead author,” she says. And for Robbie Samuels, who was steeped in progressive activism long before coming out as transgender, his new identity—which meant he was generally perceived as a straight white male—gave him a new frontier in which to make a difference. “I try to always use my privileges…to create opportunities for everyone in the room to contribute more of their full selves,” he says, adding that he became involved in his local chapter of the National Organization for Men Against Sexism. “That’s a major element of my personal brand and may not have been fully realized if I had not had to grapple with this self-discovery as a trans man.”

When you come out as transgender, it may seem like a break with the past is necessary. In many ways, it’s even desirable: finally, a chance to reinvent your personal brand on your own terms. But you don’t have to get rid of everything. The real secret of personal branding is retaining the best parts of your past experience, while simultaneously creating the new identity you envision.

[image error]

How to Revive a Tired Network

On a scale of one to five, how important is having a good network to your ability to accomplish your goals? When I ask my executive students this question, most of them answer in the fours and fives. Even the most naive of them agree that, like it or not, relationships hold the key to both their current capacity and future success.

A Network Audit

Think of up to ten people with whom you have discussed important work matters over the past few months (you are not required to come up with ten). You might have sought them out for advice, to bounce ideas off them, to help you evaluate opportunities, or to help you strategize important moves. Don’t worry about who they should be. Only name people to whom you have actually turned for this help recently.

List their names or initials, without reading further.

The main strengths of my network as it exists today are:

The main weaknesses of my network as it exists today are:

What can a network do for you? It can keep you informed. Teach you new things. Make you more innovative. Give you a sounding board to flesh out your ideas. Help you get things done when you are in a hurry and you need a favor. The list goes on.

When it comes to stepping up to leadership, your network is a tool for identifying new strategic opportunities and attracting the best people to them. It’s the channel through which you sell your initiatives to the people you depend on for cooperation and support. It’s what you rely on to win over the skeptics. It protects you from being clueless about the political dynamics that so often kill good ideas. Your relationships are also the best way to change with your environment and industry, even if your formal role or assignment has not changed. Without a good network, you will also limit your own imagination about your own career prospects. Your network is also what puts you on the radar screen of people who control your next job or assignment and who form their opinion of your potential partly on who knows you and what they say about you.

But just because you know that a network is important to your success, it doesn’t mean you are devoting sufficient time and energy to making it useful and strong. In fact, few of us do. I know because I ask a second question: On a scale of one to five, how would you rate the quality of your current network?

My guess is that your second number is lower than your first. On average, my executive students answer this question in the twos and threes. Most admit that even by their own standards, their networks of connections leave much to be desired.

The good news is that you can change that. By managing the three key properties of networks that either propel you forward or hold you back—breadth, connectivity, and dynamism—you can develop a stronger network and use it as an essential leadership tool. This article will show you how to reinvent your network, by managing these three critical dimensions.

To start, assess the network you have today. The sidebar “A Network Audit” lets you conduct a quick-and-dirty audit of your present network. The questions represent a short version of the survey I use with my students.

As you’ll see, there are three basic sources of connective advantage that you will need to build into your network. As you read the next section, you may want to return to this network audit to assess if these properties of networks are working for you or against you.

The BCDs (Breadth, Connectivity, and Dynamism) of Networking Advantage

Your network’s strategic advantage and, therefore, the extent to which it helps you step up to leadership, depends on three qualities:

Breadth: Strong relationships with a diverse range of contacts

Connectivity: The capacity to link or bridge across people and groups that wouldn’t otherwise connect

Dynamism: A dynamic set of extended ties that evolves as you evolve

I call these three qualities the BCDs of network advantage, or A = B + C + D.

Breadth: How Diverse Is Your Network?

One of the first things that my students notice when they audit their networks is that the network formed by the people they talk to about important work matters is much more internally focused than it should be. As these managers start to concern themselves with broad strategic issues and organizational change processes, lateral relationships with people outside their immediate area become even more critical to the managers’ ability to get things done. And in a connected world, building stronger external networks to tap into the best sources of insight into environmental trends is also part and parcel of the leadership role.

Data compiled from the network surveys I give my participants shows that we are still not using networks to our best advantage. We build networks that are heavily skewed toward our own functional, business, or geographical group and fail to elicit or value the input and perspectives of peers from different functional or support groups. Moreover, we are still relying on networks that are mostly internal to our company, in a world where the rate of change outside is considerable.

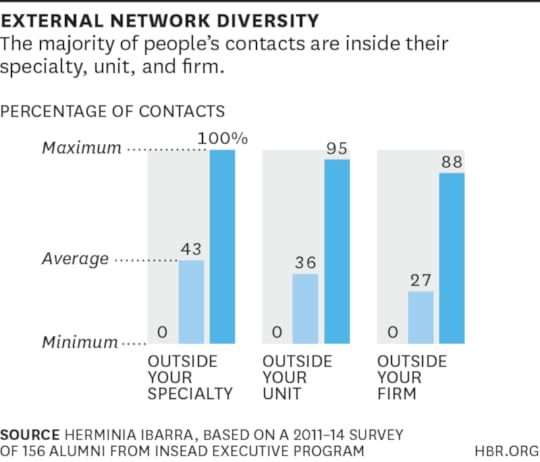

As the descriptive statistics in the figure “External Network Diversity” show, the majority of my students’ contacts are inside their specialty, unit, and firm. On average, less than 43 percent of the people the executive students were discussing key issues with were located outside their unit or specialty; even fewer, only a quarter, were external to their company. But averages can be deceiving: the range of values shows that some of the managers in the survey have no contacts at all outside their specialty, unit, or firm.

You can also overdo diversity: the ranges also show that some of the executives have heavily external networks: up to 100 percent and 95 percent outside their specialties and units, respectively, and 88 percent outside their companies. That’s fine if an executive is looking to move elsewhere, as some of my participants were. But an exclusively outside network is not as useful if you are trying to bring an outside approach into your own company. You can’t bridge the outside to the inside if you haven’t established strong relationships on the inside.

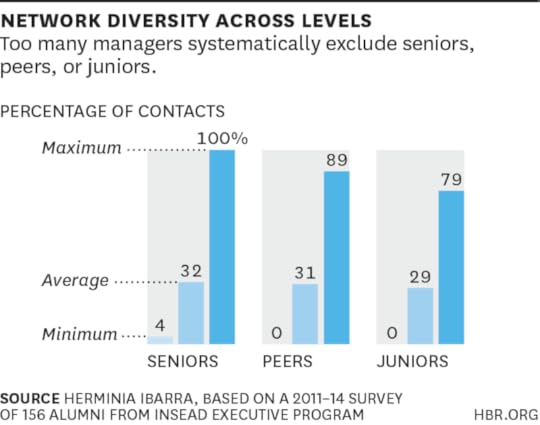

Another common network blind spot consists of undervaluing the potential contributions of junior people. Managers striving to make their way up the leadership pipeline tend to manage up, forgetting that their connection to the layers below is often what makes them invaluable to seniors whose sponsorship they hope to attract. One manager explained it to me this way: “I would perhaps have been able to add even more value to my superiors if I had retained my links with more junior people. For example, recently we were in a meeting discussing the results of a global people survey. I was listening to all their comments, and I said, ‘You guys are looking at this from the perspective of very senior people; be careful about how you are interpreting the results. [People at a lower level] are saying something completely different.’ I knew that because I had been spending time with them.” Given a choice between a network heavily skewed to the power players in your firm and a good mix of diverse contacts, which would you choose? Research shows that you are better off with the latter. This is because networks run on the principle of reciprocity. The value of diverse relationships lies not only in what your contacts can do for you, but also on what you can do for them. Your senior leaders don’t need you to connect them with other seniors; they already know each other. Top management needs you to bring them the fresh ideas, insights, and best practices that you can only get elsewhere, outside, across, and below. As the figure “Network Diversity Across Levels” shows, too many managers lack the 360-degree perspective you can only get from cultivating relationships with a mix of peers, juniors, and seniors. Although the averages suggest that people focus their networking on approximately one-third of each group, the range of the scores shows that too many managers systematically exclude one of these groups. The sidebar “Why We Need Fresh Blood” explains how diversity on any team often produces the best results.

Why We Need Fresh Blood

Stefan Wuchty, Benjamin Jones, and Brian Uzzi, a multidisciplinary team of researchers, decided to use big data to learn what distinguished ideas that had impact from those that didn’t. In a massive study of the twenty million academic articles and two million patents cited over the past fifty years, which Wuchty and his colleagues published in the prestigious journal Science, they found that the difference lies in the kinds of networks that produce the ideas.a

The study showed that the days of the solitary genius or lone inventor—think Newton or Einstein—are over. Creative and scientific work has migrated to teams and, more recently, to large, distributed teams like the hundreds of scientists that worked on the human genome project.

But being part of a team wasn’t enough for high impact, as measured by article and patent citations. The really great ideas were much more likely to come from cross-institutional collaborations rather than from teams from the same university, lab, or research center. Not only that, but the most successful teams mixed things up. They avoided the trap of always working with the same people, and successful groups brought to the team both newcomers and people who had never collaborated before.

Uzzi and another colleague, Jarrett Spiro, also discovered that this pattern held across sectors as disparate as the Broadway musical industry and biotechnology.b Between 1920 and 1930, for example, 87 percent of Broadway shows flopped despite being attached to big names like Rogers and Hammerstein, or Gilbert and Sullivan. When well-known composers like these continued to work together without the benefit of fresh blood, their creations suffered, critically and financially. The most successful plays, instead, resulted from collaborations among diverse players. Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story, for example, which went on to become a megahit, featured newcomer Stephen Sondheim and other new collaborators.

a. Stefan Wuchty, Benjamin F. Jones, and Brian Uzzi, “The Increasing Dominance of Teams in Production of Knowledge,” Science 316, no. 5827 (2007): 1036–1039.

b. Brian Uzzi and Jarrett Spiro, “Collaboration and Creativity: The Small World Problem,” American Journal of Sociology 111, no. 2 (2005): 447–504.

On making a list of their relationships, even highly experienced leaders find that they’ve failed to network with people who are different from them or to build bridges across and outside their organization’s lines. Check the diversity of your network by returning to the list you made in your Network Audit. To what extent are your relationships externally facing? Have you included a good mix of people occupying different levels and functions?

How Connective Is Your Network?

So far we’ve looked at who the people are in your network and how you are connected to these people. Now we’ll turn to how your contacts are connected and what that means for you.

The connectivity of your network is the basis for the famous six degrees of separation principle—the idea that we are rarely ever more than six links removed from anyone else in world through the friends of our friends—discovered by Harvard psychologist Stanley Milgram in the 1960s. As any LinkedIn user knows, the fewer degrees of separation between any two people in a network, the easier it is to access the resources you need.

In the original study, Milgram gave a bunch of people in Nebraska a letter destined for a stockbroker in Massachusetts—a man they didn’t know. Their job was to get the letter to him by sending it to someone they did know, who might then send it to someone else, ultimately reaching the stockbroker. Milgram found that it never took more than six links (thus the six-degrees concept) to reach the stockbroker, for those letters that actually arrived. But many of the letters never got there, because the first degree—the people his participants knew directly and contacted first—didn’t have networks that reached outside their local environment. So, many of the letters never got out of Nebraska. They only circulated inside the same circle of people who all knew each other.

Adapted from

Act Like a Leader, Think Like a Leader

Leadership & Managing PeopleBook

30.00

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Something similar happens when you fall prey to the biggest trap in networking: everyone you know knows the same people you do, and the flow of information gets stuck in the same office, in the same industry, in the same neighborhood. Sociologists use the term density to describe this property of networks: it quantifies the percentage of people who know each other in a network. Density is an imperfect measure, but it is a quick way to check how much six-degree potential you have in your network. See the sidebar “Calculate Your Network’s Density.”

Calculate Your Network's Density

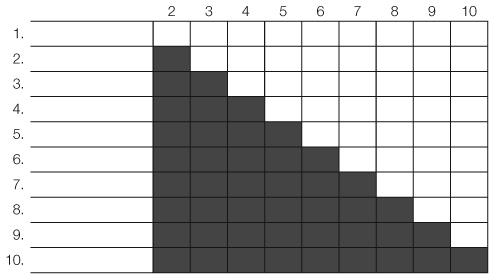

Go back to the list of up to ten contacts you made, and put their names into a copy of the grid provided here.

Using only the unshaded portion of the grid, place a checkmark to indicate which pairs of people know each other. If you are not sure whether two people know each other, assume they don’t.

Start with person 1, and run along the top row checking if person 1 knows persons 2, 3, 4, and so on. Then go to person 2, and do the same until you have considered all the people on your list.

Now, compute the density of your network following these steps:

Count the total number of people on your list (the maximum is 10), and write it down.

Take that number, and multiply it by the number minus 1. Then divide the result by 2, and write it down.

Count the total number of checkmarks on your grid (i.e., the number of links that exist between the various people on your list), and write that number down.

Take the number you obtained in step 3, and divide it by the number you got in step 2. This is the density of your network.

The lower your network’s density score, the less inbred your network (note that lower isn’t necessarily better because too low a density, as I explain below, can be problematic too).

If you are like many of the successful executives I teach, chances are that your density score is higher than it should be. When I conduct this exercise in class, the average density hovers above 50 percent, although it is significantly lower for professionals who work mostly with outside clients such as consultants, investment bankers, lawyers, headhunters, and auditors and for people who go back to school to orchestrate a career change. The range of scores always extends to 100 percent: when nearly everyone with whom you discuss important work issues knows each other, you have an inbred network. There’s no other way to put it.

To understand the problems of having an inbred network, let’s look at the effects of network density in a completely different context: the so-called obesity epidemic. Two previously unknown university professors, Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler, became overnight celebrities when they showed that being overweight can be contagious.

Christakis and Fowler analyzed the health records and social relationships of twelve thousand Framingham, Massachusetts, residents from 1948 to the present. Using advanced visualization techniques and careful statistical controls, they showed that overweight people tend to hang together socially, while thin people tend to be friends with other thin people. But this is not a mere correlation showing that birds of a feather flock together: being connected socially to people who are overweight, even indirectly, seems to make a person overweight. The researchers concluded that thin and overweight people tend to live their lives within different and unconnected social clusters—“microclimates,” so to speak— within which different social norms about what is normal and desirable have developed. Political views also hang by cluster. Tightly connected members apparently had no external perspective on the world beyond their immediate group.

At work, when we surround ourselves with people like us and with whom we’ve worked before, the network creates an echo chamber in which no new information circulates because everyone has the same sources. That’s how groups become mired in consensus, and after a while, everyone thinks and acts alike. The sidebar “The Innovator’s Network Dilemma” presents convincing data that bears out this observation.

The Innovator's Network Dilemma

A study by University of Chicago sociologist Ron Burt demonstrates the cost of inbred networks.

When Burt studied managers in the supply chain of Raytheon, the large electronics company and military contractor based in Waltham, Massachusetts, he discovered that the company had no trouble coming up with good ideas but considerable difficulty turning these ideas into reality.

Burt asked the managers to write down their best ideas about how to improve business operations, and then he asked two executives at the company to rate the quality of these ideas. He then mapped out the network of who consulted with whom. Burt was looking for what he calls “structural holes,” gaps between cohesive groups of people with dense patterns of informal communication among them and few ties outside their circle.

His many years of research have shown that people whose networks span these holes reap the greatest network benefits. These people see more and know more. They have more power because other people have to go through them to connect outside their group.

Not surprisingly, the highest-ranked ideas came from managers who had contacts outside their immediate work group. Most managers, however, overwhelmingly turned to colleagues already close in their informal discussion network to bounce ideas off (think “inbred circle”). The result was that their ideas were not developed.a

a. Ronald S. Burt, Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995); Ronald S. Burt, “Structural Holes and Good Ideas,” American Journal of Sociology 110, no. 2 (2004): 349–399. See also Gautam Ahuja, “Collaboration Networks, Structural Holes, and Innovation: A Longitudinal Study,” Administrative Science Quarterly 45, no. 3 (2000): 425–455.

This state of affairs also limits significantly how valuable you are to your network, since you bring nothing unique that the network members can’t get elsewhere. Your comparative advantage— how you differentiate yourself from others who are as smart, hardworking, or expert as you are—depends on your capacity to connect people, ideas, and resources that wouldn’t normally bump into one another.

Some research suggests that there’s an optimum level of density, about 40 percent. But of course, that depends a lot on what a person’s job is. When your network gets too sparse, you lose connectivity. You are a “visitor” to many networks but a “citizen” of none. You may have access to lots of ideas and people, but you can’t put them to use inside your organization (or any other group to which you belong), because you lack inside information about how to pitch your ideas, who might be opposed to them, and how to win people over—all critical parts of leading change.

Too sparse a network, and you might also lack credibility and visibility with important gatekeepers, who might not know you well but who implicitly evaluate you on the basis of who you know that they also know (the principle on which professional networks like LinkedIn work). This is often a problem when you are the minority in a group. People are apt to have relationships with people like them, so minorities and majorities and professional men and women are unlikely to have highly overlapping networks. In a study of boards of directors, for example, James Westphal found that minority directors tend to be more influential if they have direct or indirect social network ties to majority directors through common memberships on other boards. These overlapping networks serve as a form of social verification and increase the likelihood that the minority’s ideas will be heard.

In sum, as Malcolm Gladwell illustrated in his book The Tipping Point, networks run on “connectors,” people who are linked to almost everyone else in a few steps and who connect the rest of us to the world. Connectors can see a need in one place and a solution in another, a vacancy in one area and a talented person in another, a discovery from a different discipline and a problem in their own, and so on, because they’re just one or two “chain lengths” away from the issues. That is, you can reach connectors through someone you already know or through someone who knows someone whom you already know.

How Dynamic Is Your Network?

One of the biggest drawbacks of a poorly managed network is that it quickly becomes a historical artifact, the residue of manager’s past rather than a tool to move into the future. We change jobs, firms, and even countries, but our networks lag behind our new responsibilities and aspirations and therefore pigeonhole us just when we need a fresh perspective or seek to move into something different. Joel Podolny, former head of Apple’s human resources, calls this tendency of our networks to evolve more slowly than our jobs “network lag.” We’re exceptionally slow to build relationships that allow us to perform in a new position or prepare us for future roles.

Making Your Network Future Facing

A financial services firm executive, Pam, realized that she was unprepared when her job became more externally facing. “I was fairly well networked internally and within my region,” she told me, “but I had no external network or external points of connectivity, and I don’t think I understood the value of those external points.” Never one to give much thought to whom she knew, she realized the time had come to build a new network systematically. Here are the steps she followed:

Identify twenty to twenty-five key stakeholders you wish to stay connected to in a meaningful way.

Assign these contacts into key categories:

Most-senior clients

Most-senior people in your company

Most-senior hedge fund people and competitors

Most-senior service providers (e.g., lawyers, accountants)

Most-senior women in financial services

For each category, select the three to five people you want to stay connected to.

Decide how frequently you will reach out to each contact.

When asked about the strengths of their network, most people think first about the quality of their relationships. They value most their strong ties, because trust is essential when it comes to getting things done, and we trust most the people we know best. But as we have seen, the people we know best are not necessarily those who can prepare us for stepping up. To make your networks future facing, you’ll need to build and value your weak ties—that is, the people and groups that are currently on the periphery of your network, those you don’t see very often or don’t know so well (see the sidebar “Making a Network Future Facing”). What’s important about these contacts is not the quality of your relationship with them (just yet), but the fact that they come from outside your current world. These contacts tend to be several levels removed from you or circulate in different circles.

That makes reaching out harder. Getting to know your weak ties or getting to know them better usually requires an explicit plan and strategy—these relationships will never evolve naturally, because you have no common context in which to develop them. Nevertheless, these are the ties from which you stand to gain the greatest outsight.

Another problem with relying exclusively on your strong-tie network is that it limits your capacity to rethink yourself. In my study of thirty-nine midcareer managers and professionals considering major career changes, I observed directly how much their old networks can “bind and blind” them. All of them were told by a friend, family member, or close coworker that they must be out of their minds for thinking about quitting their jobs or leaving their organizations. The people close to you may mean well, but they are often not helpful when you are trying to stretch yourself. Despite their good intentions, they hold restrictive views of who you are and what you can do. So, they are the people most likely to reinforce—or even desperately try to preserve—the old identity you are trying to shed.

Getting Started: Experiments with Your Network

In the next three days, talk to three people outside your business unit or company; learn what they do, how it helps the company, and how it may apply to your work.

In the next three weeks, reconnect with people outside the company who may shed useful light on your work, industry, or career. Have lunch.

Make a list of five senior people you need to get to know better. Figure out ways to strengthen your relationship over the next three months.

These three sources of network advantage—the diversity of your contacts, your connectivity within the network, and your network’s dynamism—are obviously interrelated. Without these advantages, you never meet new people and the circle closes; over time, you lose relevance.

Return to the network audit that you completed, and check what you listed as the strengths and weaknesses of your current network. Which of the following weaknesses that we discussed above are true for you?

Birds of a feather: Your contacts are too homogeneous, all like you.

Network lag: Your network is about your past, not your future.

Echo chamber: Your contacts are all internal; they all know each other.

Pigeonholing: Your contacts can’t see you doing something different.

Practical Steps to Expand Your Network

Spend time at a start-up within your business sector. Consider why incumbents rarely lead the way in new products and services.

Attend a conference you have never before attended. Meet at least three new people. Follow up with them afterward.

Start a LinkedIn or Facebook group. Be the connector for this group of people.

Spend a day with a millennial in your company. Learn more about how she uses social media.

Get in touch with a venture capitalist. Find out how he thinks about leadership and innovation.

Teach a course at a university or local college. Learn from your students.

Be a guest speaker at a local or national event. Use it to build or strengthen your brand around a particular area of expertise.

Go to lunch with a peer from a competing company. Learn more about your market value.

Start a blog. Find out who reads it.

Take advantage of your next business trip to connect with someone you’ve lost track of. Have this person help you connect with someone new.

Summary

✓ As you embark on the transition to leadership, networking outside your organization, team, and close connections becomes a vital lifeline to who and what you might become.

✓ The only way to realize that networking is one of the most important requirements of a leadership role is to act.

✓ If you leave things to chance and natural chemistry, then your network will be too inward-facing and not diverse enough.

✓ You need operational, personal, and strategic networks to get things done, to develop personally and professionally, and to step up to leadership. Although most good managers have good operational networks, their personal networks are disconnected from their leadership work, and their strategic networks are nonexistent or underutilized.

✓ Network advantage is a function of your BCDs: the breadth of your contacts, the connectivity of your networks, and your network’s dynamism.

✓ Enhance or rebuild your strategic network from the periphery of your current network outward as a first step toward increasing your outsight on your self:

Seek outside expertise.

Elicit input and perspectives of peers from different functional or support groups.

This article is adapted from the Harvard Business Review Press book Act Like a Leader, Think Like a Leader.

[image error]

7 Steps to Deliver Better Customer Experiences

A surprising thing happened during a recent brainstorming session I led for a retail client. We were supposed to be coming up with ideas for improving the company’s customer experiences, but the head of operations could not think of a single new customer service idea to explore. And the development leader failed to identify any new ideas for store layout or building features. And the merchandising vice president had difficulty understanding why “product” was one of the categories we were discussing.

Each of these executives offered plenty of ideas when the discussion turned to promotions, social media tactics, and marketing messages. But apparently none of them understood that generating new customer experience ideas would involve his domain. They seemed to think that designing and managing the customer experience is a marketing function, as if the customer is only associated with marketing, and the store only with operations. They were happy to maintain the age-old silo between marketing and operations.

I was stunned. How could such a misconception of customer experience have developed? After all, it’s been 10 years since Don Peppers and Martha Rogers, in their seminal book, Return on Customer, declared the customer experience the single most important factor for business success. And since then, countless case studies and analyses have been published about the importance of optimizing a business around the customer experience. If such confusion can exist at a high-growth, $2.5 billion public company, how many other organizations could be struggling to understand and manage customer experience appropriately?

I’ve discovered that most companies are using an incomplete definition of customer experience, and have incomplete tools and approaches to design and manage it.

While customer experience can be defined as the sum of all interactions a customer has with a company, most people operate with a narrower view. Some understand it as customer service or service excellence — without recognizing that service is only one element of the entire experience. Others, like my client, consider it to be customer marketing — that is, the communications and promotional activities used to attract and retain customers. Again, these activities represent only a fraction of the interactions between company and customer — and as it’s been said time and again, what an organization says in its advertising has far less impact on customer perceptions than what it does in reality.

Even with the correct, complete view of customer experience, it’s still possible for companies to mismanage it because they lack the proper tools to help them design and manage their approach. The most common mistake in mismanaging the customer experience is starting with customer data. Using data and analytics as a starting point fails to recognize the importance of coherence between customer experience and brand identity. (By brand identity, I mean the defining values and attributes that distinguish a brand.) Delivering on the brand promise, expressing the brand personality, and bringing the brand attributes to life should be the primary objectives when designing the customer experience. Some companies drive their customer experience with conversion rate and customer lifetime value targets, then end up delivering experiences that are unmemorable and undifferentiated.

Other common tools, like journey maps, are also incomplete because multiple customer journeys usually exist for a single organization. Most companies target more than one customer segment with more than one need or driver, and today’s customers engage in more than one channel or sequence of channels.

A more thorough approach to designing and managing customer experience is to use a customer experience architecture. It’s a framework for designing and delivering the optimal experiences to different customer segments in different business segments with different business objectives. The “architecture” is similar to other strategic architectures that are used as planning tools, like a brand architecture or an information architecture — or a structural architecture for building a house.

To develop a customer experience architecture, follow these steps:

1. The brand platform — First, define or reaffirm the overarching ideas that represent the brand. REI’s brand platform is the excitement and adventure of the outdoors; Chick-fil-A’s is exceeding customers’ expectations with a servant’s spirit.

2. Customer experience strategy — Then describe the desired customer feelings and perceptions of the brand across all interactions with the organization. An electronics website might want to create a “place” for customers to discover and be delighted by innovations. A hotelier might want customers to feel pampered by legendary service.

3. Business segmentation — The next step is to break down the business into discrete units. For a new brand, segmenting the business by traffic vs. trial vs. transition might be an illuminating approach; a restaurant company might segment by service mode, e.g., eat-in vs. drive-thru vs. carry-out; and a product-line segmentation might be appropriate for a manufacturer. The objective is to identify the different experiences the organization delivers and to articulate the requirements and objectives of each.

4. Customer segmentation — Different target segments have different needs — some customers may value convenience over price, others may be looking for an entertaining experience — so their desired experiences vary. Describe each segment with a profile and a needs inventory, including key drivers of purchase decisions and brand perceptions.

5. Prioritization — Create a grid with the business segments as columns and customer segments as rows. Each business/customer intersection represents a discrete experience to design and deliver. They should be prioritized in order to focus design and management. Prioritization criteria include profit potential, fit with long-term strategy, competitive advantage and differentiation, resource requirements, and how the experience affects and/or reinforces brand values and brand position.

6. Experience design — Determine how to meet the segment-specific needs in each business segment, either by improving existing approaches based on new insights from the architecture or by developing entirely new ones. All the levers of customer experience — product, service, content, channels, touchpoints, pricing, facilities, sensory engagement, etc. — should be considered and described in the design.

7. Assessment and integration — Now the architecture is ready to be inspected for integrity and coherence. Is the brand platform expressed throughout every experience? Do the discrete experiences contribute to the overall customer experience strategy? Do experiences complement and enhance each other, or do they conflict or detract from each other?

Developing a customer experience architecture isn’t rocket science, but it requires accepting a broader, fuller definition of customer experience and committing to a robust planning tool and process.

Companies that develop their own architecture will find it breaks down organizational silos, addresses the diversity of customers and their needs, and produces unique and compelling experiences.

[image error]

Increase the Odds of Achieving Your Goals by Setting Them with Your Spouse

Do a quick Google search of “work-life balance” and over 260 million results will flood your screen. But the current conversation often treats “work” and “life” as separate and, all too often, in tension. We make annual resolutions, detailed daily plans, and to-do lists, but we do so as individuals — generally not sharing those plans or planning jointly with those closest to us. And we often think of our personal and professional goals as occupying distinct and separate spheres. But what if the work and home “spheres” could merge and actually improve the odds that we’ll achieve our goals?

Research shows that it’s easier to achieve our goals when we’re not trying to go it alone. One recent research paper found a positive correlation between participation in digital communities and reaching fitness goals. Similarly, a study of rowers found that their working together in training heightened their threshold for pain.

For many of us, our closest and most trusted companion is a spouse. Couples in committed, long-term relationships often see each other every day, but rarely plan or set resolutions together. By not doing so, couples may actually be making it harder to achieve their goals. This January, we fully integrated our personal planning for the year for the first time. We’ve always informally mentioned our goals to each other, but this time around, we talked with intentionality about why we were chasing those goals, and how we planned to get there. By including each other in the process, we invited the other to not only be aware of what we plan to accomplish this year, but also to hold us accountable as we strive to reach these goals. And our experience combined with research we’ve evaluated and other couples we’ve consulted with have led us to a few tips for effective planning as a couple.

First, start with an annual board meeting. Several years ago, we attended a seminar where speakers Rick and Jill Woolworth introduced the idea of an “annual meeting” for families — taking time at the end of each year to evaluate that year and plan for the next. Establishing this as a family norm assures that goal-setting happens on a set schedule rather than haphazardly or in isolation. For us, this happened over the holidays between Christmas and the new year, and included a discussion of the past year, how we performed against our goals, and how we felt about life as a couple and individuals. We wrote out our specific goals for the year and the habits we hoped to develop. Then we discussed them and how each of us could help the other achieve each goal. These annual meetings provide accountability, but more importantly, lay a vision for the year ahead. Then, as so many have advised, break these annual goals into habits, monthly and weekly goals, and daily to-dos.