Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1327

January 23, 2015

3 Ways Businesses Are Addressing Inequality in Emerging Markets

Last year, the World Bank added a new mission to its original goal of reducing poverty: boosting shared prosperity. The change reflects the state of today’s world: the fraction of the global population in extreme poverty, defined as those earning less than $1.25 per day, has dropped to 12% from 36% in 1990. Yet income inequality is more pronounced than ever. According to a report released by Oxfam International on Monday, the richest 80 individuals in the world hold as much wealth as the poorest 3.5 billion. World Bank President Jim Kim has called this reality a “stain on our collective conscience,” explaining that boosting shared prosperity is the best way to fight inequality. We agree wholeheartedly with that approach. And we believe businesses must play a large role in making it happen.

Unlike extreme poverty remediation, shared prosperity cannot be accomplished solely by government handouts or even the well-meaning initiatives of NGOs. The first is not affordable and the second is often not scalable. Businesses can be a significant part of the solution. But they much more likely step in if they recognize that serving the masses is not about altruism or charity — it can be profitable in its own right.

Business can apply its innovative genius in three ways to create shared prosperity: by supplying quality products at ultra-affordable prices, which will allow the masses to stretch their purchasing power and improve living standards; by creating new opportunities for gainful employment, which will increase their incomes; and by providing access to services that will increase their future earning potential.

Take the case of Safaricom, Kenya’s largest cell phone company and creator with Vodafone of the popular wireless banking product, M-Pesa. As in other developing countries, telephone service and banking were regarded in Kenya as products for the rich, but the emergence of mobile phones and online banking, and the innovative idea of combining them, has brought these services to the Kenyan masses at ultra-low prices. Before M-Pesa, most Kenyans were classified as “unbanked,” and they transferred money in cash, through a friend or via a bus or taxi. This was slow, risky, costly, and inconvenient. Today, a phone doesn’t just give the poor the joy of communication but also a means to enhance their livelihood. One study reports that mobile phone usage increased the income of Ugandan farmers by 36%.

Businesses can also help the poor by enlisting the poor to serve the poor. An inspiring example is Aravind Eye Care Hospital of India. Two-thirds of its staff members are village girls with a high school degree who have been trained by Aravind for two years to perform many tasks, including helping doctors perform surgery. This has allowed Aravind to perform cataract surgery for just $100. (The cost of cataract surgery in the U.S. is over $3,500). As a result, Aravind has created thousands of jobs for village girls, while giving eyesight — and the dignity and employability that come with it — to three million poor. Because the girls come from the same villages as Aravind’s poor patients, they empathize with and serve them better than city-trained nurses tend to. The strategy produces winners all around, including Aravind, which has been able to fund its rapid growth entirely with internal resources.

Finally, businesses can provide income mobility to the poor and help them migrate up the income ladder — for instance, by giving them access to higher education. Kroton Educacional of Brazil is doing just that, in a country where just 57% of children finish high school and 14% of young adults enter college. Kroton started by developing innovative curricula for K-12 education in one province, and then grew to become a national leader in online higher education. Last year it merged with another for-profit firm to become the world’s largest online educator, with 1.2 million students and a market capitalization of $11 billion. Kroton has leveraged technology, such as online courses and satellite broadcasting of lectures by gifted teachers, to educate students across Brazil, including remote parts of the Amazon. Fees are low, quality is high, access is widespread, and the curriculum promotes employability. Kroton’s graduates have seen their incomes grow by a higher multiple than students in any OECD country.

These organizations have fewer peers than they ought to. But their winning formula is not a secret. To innovate for the developing world, companies must deeply understand the customer’s problem before designing solutions; localize R&D, manufacturing, the supply chain, and marketing in the economies they serve; and stick to the goal of providing high-quality products at ultra-affordable prices. We won’t pretend this is easy, but the potential rewards for businesses — and for societies in narrowing income inequality — are too large to ignore.

[image error]

How to Conduct an Effective Job Interview

The virtual stack of resumes in your inbox is winnowed and certain candidates have passed the phone screen. Next step: in-person interviews. How should you use the relatively brief time to get to know — and assess — a near stranger? How many people at your firm should be involved? How can you tell if a candidate will be a good fit? And finally, should you really ask questions like: “What’s your greatest weakness?”

What the Experts Say

As the employment market improves and candidates have more options, hiring the right person for the job has become increasingly difficult. “Pipelines are depleted and more companies are competing for top talent,” says Claudio Fernández-Aráoz, a senior adviser at global executive search firm Egon Zehnder and author of It’s Not the How or the What but the Who: Succeed by Surrounding Yourself with the Best. Applicants also have more information about each company’s selection process than ever before. Career websites like Glassdoor have “taken the mystique and mystery” out of interviews, says John Sullivan, an HR expert, professor of management at San Francisco State University, and author of 1000 Ways to Recruit Top Talent. If your organization’s interview process turns candidates off, “they will roll their eyes and find other opportunities,” he warns. Your job is to assess candidates but also to convince the best ones to stay. Here’s how to make the interview process work for you — and for them.

Prepare your questions

Before you meet candidates face-to-face, you need to figure out exactly what you’re looking for in a new hire so that you’re asking the right questions during the interview. Begin this process by “compiling a list of required attributes” for the position, suggests Fernández-Aráoz. For inspiration and guidance, Sullivan recommends looking at your top performers. What do they have in common? How are they resourceful? What did they accomplish prior to working at your organization? What roles did they hold? Those answers will help you create criteria and enable you to construct relevant questions.

Reduce stress

Candidates find job interviews stressful because of the many unknowns. What will my interviewer be like? What kinds of questions will he ask? How can I squeeze this meeting into my workday? And of course: What should I wear? But “when people are stressed they do not perform as well,” says Sullivan. He recommends taking preemptive steps to lower the candidate’s cortisol levels. Tell people in advance the topics you’d like to discuss so they can prepare. Be willing to meet the person at a time that’s convenient to him or her. And explain your organization’s dress code. Your goal is to “make them comfortable” so that you have a productive, professional conversation.

Involve (only a few) others

When making any big decision, it’s important to seek counsel from others so invite a few trusted colleagues to help you interview. “Monarchy doesn’t work. You want to have multiple checks” to make sure you hire the right person, Fernández-Aráoz explains. “But on the other hand, extreme democracy is also ineffective” and can result in a long, drawn-out process. He recommends having three people interview the candidate: “the boss, the boss’ boss, and a senior HR person or recruiter.” Peer interviewers can also be “really important,” Sullivan adds, because they give your team members a say in who gets the job. “They will take more ownership of the hire and have reasons to help that person succeed,” he says.

Assess potential

Budget two hours for the first interview, says Fernández-Aráoz. That amount of time enables you to “really assess the person’s competency and potential.” Look for signs of the candidate’s “curiosity, insight, engagement, and determination.” Sullivan says to “assume that the person will be promoted and that they will be a manager someday. The question then becomes not only can this person do the job today, but can he or she do the job a year from now when the world has changed?” Ask the candidate how he learns and for his thoughts on where your industry is going. “No one can predict the future, but you want someone who is thinking about it every day,” Sullivan explains.

Further Reading

How to Separate the Winners from the Spinners

Hiring Article

Chris Smith and Chris Stephenson

Push job candidates out of their comfort zone to find out who they really are.

Save

Share

Ask for real solutions

Don’t waste your breath with absurd questions like: What are your weaknesses? “You might as well say, ‘Lie to me,’” says Sullivan. Instead try to discern how the candidate would handle real situations related to the job. After all, “How do you hire a chef? Have them cook you a meal,” he says. Explain a problem your team struggles with and ask the candidate to walk you through how she would solve it. Or describe a process your company uses, and ask her to identify inefficiencies. Go back to your list of desired attributes, says Fernández-Aráoz. If you’re looking for an executive who will need to influence a large number of people over whom he won’t have formal power, ask: “Have you ever been in a situation where you had to persuade other people who were not your direct reports to do something? How did you do it? And what were the consequences?”

Consider “cultural fit,” but don’t obsess

Much has been made about the importance of “cultural fit” in successful hiring. And you should look for signs that “the candidate will be comfortable” at your organization, says Fernández-Aráoz. Think about your company’s work environment and compare it to the candidate’s orientation. Is he a long-term planner or a short-term thinker? Is he collaborative or does he prefer working independently? But, says Sullivan, your perception of a candidate’s disposition isn’t necessarily indicative of whether he can acclimate to a new culture. “People adapt,” he says. “What you really want to know is: can they adjust?”

Sell the job

If the meeting is going well and you believe that the candidate is worth wooing, spend time during the second half of the interview selling the role and the organization. “If you focus too much on selling at the beginning, it’s hard to be objective,” says Fernández-Aráoz. But once you’re confident in the candidate, “tell the person why you think he or she is a good fit,” he recommends. Bear in mind that the interview is a mutual screening process. “Make the process fun,” says Sullivan. Ask them if there’s anyone on the team they’d like to meet. The best people to sell the job are those who “live it,” he explains. “Peers give an honest picture of what the organization is like.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Lower your candidates’ stress levels by telling them in advance the kinds of questions you plan to ask

Ask behavioral and situational questions

Sell the role and the organization once you’re confident in your candidate

Don’t:

Forget to do pre-interview prep — list the attributes of an ideal candidate and use it to construct relevant questions

Involve too many other colleagues in the interviews — multiple checks are good, but too many people can belabor process

Put too much emphasis on “cultural fit” — remember, people adapt

Case study #1: Provide relevant, real-life scenarios to reveal how candidates think

The vast majority of hires at Four Kitchens, the web design firm in Austin, TX, are through employee referrals. So in November, when Todd Ross Nienkerk, the company’s founder and CEO, had an opening for an account manager, he had a hunch about who should get the job. “It was somebody who’d been a finalist for a position here years ago,” says Todd. We’ll call her Deborah. “We kept her in mind and when this job opened, she was the first person we called.”

Even though Deborah was a favored candidate, she again went through the company’s three-step interview process. The first focused on skills. When Four Kitchens interviews designers or coders, it typically asks applicants to provide a portfolio of work. “We ask them to talk us through their process. We’re not grilling them, but we want to know how they think and we want to see their personal communication style.” But for the account manager role, Todd took a slightly different tack. Before the interview, he and the company’s head of business development put together a job description and then came up with questions based on the relevant responsibilities. They started with questions like: What are things you look for in a good client? What are red flags in a client relationship? How do you deal with stress?

Then, Todd presented Deborah with a series of redacted client emails that represented a cross-section of day-to-day communication: some were standard requests for status updates; others involved serious contract disputes and pointed questions. “We said, ‘Pretend you work here. Talk us through how you’d handle this.’ It put her on the spot, but frankly, this is what the job entails.”

After a successful first round, Deborah moved on to the second phase, the team interview. In this instance, she met with a project manager, a designer, and two developers. “These are an opportunity for applicants to find out what it’s like to work here,” says Todd. “But the biggest reason we do it is to ensure that everyone is involved in the process and feels a sense of ownership over the hire.”

The final stage was the partner interview, during which Todd asked Deborah questions about career goals and the industry. “It was also an opportunity for her to ask us tough questions about where our company is headed,” he says.

Deborah got the job, and started earlier this month.

Case study #2: Make the candidate comfortable and sell the job

When Mimi Gigoux, the EVP of human resources at Criteo, the French ad-tech company, interviews a job candidate, she looks for signs of “intellect, open-mindedness, and passion” both for the company and for the role. “Technical expertise can be taught on the job, but you can’t teach passion, drive, and creativity,” says Mimi, who is based in Silicon Valley.

About two months ago, Mimi opened a requisition for a new member of her team. She was particularly interested in one of the applicants: a person who had previously run talent operations at several top companies in the Bay Area. We’ll call him Bryan.

Before the interview, her team communicated with Bryan about the kinds of questions Mimi planned to ask. “I don’t believe in ‘tough interviews,’” she says. “If candidates perceive a hostile environment, they go into self-preservation mode.” And when Bryan came in for the interview, she did everything she could to make him comfortable. She started by asking him questions about his hobbies and interests, and Bryan told her about recent trips he had taken to Nepal and Australia. “It told me that he was open and intrigued by different cultures”— a characteristic she deemed critical for the recruiting role.

Mimi then moved on to past professional experience. Her aim, she says, was “to find out what inspired him to move from one job to the next.” She also asked behavioral-based questions. “I wanted to see how he identified patterns and problems, how he has managed difficult personalities in the past, and how he worked cross-functionally,” she says.

As the interview progressed, Mimi became more and more convinced that Bryan was the right person for the job. She shifted from asking questions to detailing “how special this company is.” She explains, “I wanted him to walk away from the interview thinking: ‘I want to work at Criteo.’”

Mimi offered the job to Bryan; he accepted but later had to retract for personal reasons.

[image error]

What Is a Business Model?

In The New, New Thing, Michael Lewis refers to the phrase business model as “a term of art.” And like art itself, it’s one of those things many people feel they can recognize when they see it (especially a particularly clever or terrible one) but can’t quite define.

That’s less surprising than it seems because how people define the term really depends on how they’re using it.

Lewis, for example, offers up the simplest of definitions — “All it really meant was how you planned to make money” — to make a simple point about the dot.com bubble, obvious now, but fairly prescient when he was writing at its height, in the fall of 1999. The term, he says dismissively, was “central to the Internet boom; it glorified all manner of half-baked plans … The “business model” for Microsoft, for instance, was to sell software for 120 bucks a pop that cost fifty cents to manufacture … The business model of most Internet companies was to attract huge crowds of people to a Web site, and then sell others the chance to advertise products to the crowds. It was still not clear that the model made sense.” Well, maybe not then.

A look through HBR’s archives shows the many ways business thinkers use the concept and how that can skew the definitions. Lewis himself echoes many people’s impression of how Peter Drucker defined the term — “assumptions about what a company gets paid for” — which is part of Drucker’s “theory of the business.”

That’s a concept Drucker introduced in a 1994 HBR article that in fact never mentions the term business model. Drucker’s theory of the business was a set of assumptions about what a business will and won’t do, closer to Michael Porter’s definition of strategy. In addition to what a company is paid for, “these assumptions are about markets. They are about identifying customers and competitors, their values and behavior. They are about technology and its dynamics, about a company’s strengths and weaknesses.”

Drucker is more interested in the assumptions than the money here because he’s introduced the theory of the business concept to explain how smart companies fail to keep up with changing market conditions by failing to make those assumptions explicit.

Insight Center

Making Money with Digital Business Models

Sponsored by Accenture

What successful companies are doing right

Citing as a sterling example one of the most strategically nimble companies of all time — IBM — he explains that sooner or later, some assumption you have about what’s critical to your company will turn out to be no longer true. In IBM’s case, having made the shift from tabulating machine company to hardware leaser to a vendor of mainframe, minicomputer, and even PC hardware, Big Blue finally runs adrift on its assumption that it’s essentially in the hardware business, Drucker says (though subsequent history shows that IBM manages eventually to free itself even of that assumption and make money through services for quite some time).

Joan Magretta, too, cites Drucker when she defines what a business model is in “Why Business Models Matter,” partly as a corrective to Lewis. Writing in 2002, the depths of the dot.com bust, she says that business models are “at heart, stories — stories that explain how enterprises work. A good business model answers Peter Drucker’s age-old questions, ‘Who is the customer? And what does the customer value?’ It also answers the fundamental questions every manager must ask: How do we make money in this business? What is the underlying economic logic that explains how we can deliver value to customers at an appropriate cost?”

Magretta, like Drucker, is focused more on the assumptions than on the money, pointing out that the term business model first came into widespread use with the advent of the personal computer and the spreadsheet, which let various components be tested and, well, modeled. Before that, successful business models “were created more by accident than by design or foresight, and became clear only after the fact. By enabling companies to tie their marketplace insights much more tightly to the resulting economics — to link their assumptions about how people would behave to the numbers of a pro forma P&L — spreadsheets made it possible to model businesses before they were launched.”

Since her focus is on business modeling, she finds it useful to further define a business model in terms of the value chain. A business model, she says, has two parts: “Part one includes all the activities associated with making something: designing it, purchasing raw materials, manufacturing, and so on. Part two includes all the activities associated with selling something: finding and reaching customers, transacting a sale, distributing the product, or delivering the service. A new business model may turn on designing a new product for an unmet need or on a process innovation. That is it may be new in either end.”

Firmly in the “a business model is really a set of assumptions or hypotheses” camp is Alex Osterwalder, who has developed what is arguably the most comprehensive template on which to construct those hypotheses. His nine-part “business model canvas” is essentially an organized way to lay out your assumptions about not only the key resources and key activities of your value chain, but also your value proposition, customer relationships, channels, customer segments, cost structures, and revenue streams — to see if you’ve missed anything important and to compare your model to others.

Once you begin to compare one model with another, you’re entering the realms of strategy, with which business models are often confused. In “Why Business Models Matter,” Magretta goes back to first principles to make a simple and useful distinction, pointing out that a business model is a description of how your business runs, but a competitive strategy explains how you will do better than your rivals. That could be by offering a better business model — but it can also be by offering the same business model to a different market.

Introducing a better business model into an existing market is the definition of a disruptive innovation. To help strategists understand how that works Clay Christensen presented a particular take on the matter in “In Reinventing Your Business Model” designed to make it easier to work out how a new entrant’s business model might disrupt yours. This approach begins by focusing on the customer value proposition — what Christensen calls the customer’s “job-to-be-done.” It then identifies those aspects of the profit formula, the processes, and the resources that make the rival offering not only better, but harder to copy or respond to — a different distribution system, perhaps (the iTunes store); or faster inventory turns (Kmart); or maybe a different manufacturing approach (steel minimills).

Many writers have suggested signs that could indicate that your current business model is running out of gas. The first symptom, Rita McGrath says in “When Your Business Model is In Trouble,” is when innovations to your current offerings create smaller and smaller improvements (and Christensen would agree). You should also be worried, she says, when your own people have trouble thinking up new improvements at all or your customers are increasingly finding new alternatives.

Knowing you need one and creating one are, of course, two vastly different things. Any number of articles focus more specifically on ways managers can get beyond their current business model to conceive of a new one. In “Four Paths to Business Model Innovation,” Karan Giotra and Serguei Netessine look at ways to think about creating a new model by altering your current business model in four broad categories: by changing the mix of products or services, postponing decisions, changing the people who make the decisions, and changing incentives in the value chain.

In “How to Design a Winning Business Model,” Ramon Cassadesus-Masanell and Joan Ricart focus on the choices managers must make when determining the processes needed to deliver the offering, dividing them broadly into policy choices (such as using union or nonunion workers; locating plants in rural areas, encouraging employees to fly coach class), asset choices (manufacturing plants, satellite communication systems); and governance choices (who has the rights to make the other two categories of decisions).

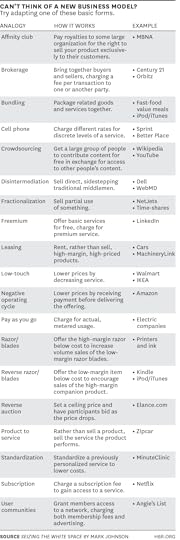

If all of this has left your head swimming, then Mark Johnson, who went on in his book Seizing the White Space to fill in the details of the idea presented in “Reinventing Your Business Model,” offers up perhaps the most useful starting point — this list of analogies, adapted from that book:

[image error]

An Exercise to Get Your Team Thinking Differently About the Future

Thinking about the future is hard, mainly because we are glued to the present. Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize-winning economist and author of Thinking, Fast and Slow, observed that decision makers get stuck in a memory loop and can only predict the future as a reflection of the past. He labels this dynamic the “narrative fallacy” – you see the future as merely a slight variation on yesterday’s news. A way around this fallacy, we’ve found, is a speed-dating version of scenario planning, one that takes hours rather than months.

Consider the experiment we recently ran with an expert panel to jump-start fresh thinking about the future. Our guinea pigs consisted of life sciences executives from big pharma, biotech entrepreneurs, and academics.

The question we asked: How might a shortage of science, technical, engineering, and math (STEM) talent affect the growth of life sciences companies? The high-speed scenario workshop involved three steps: 1) Identify key story elements or drivers of the STEM talent “story” to be explored; 2) conceive a plausible future by combining the elements; and 3) explore this future to understand its implications for their businesses.

Participants chose three drivers — forces that could be expected to shape the future of the life science industries: Science education, federal investment in life sciences, and private investment. They then identified extremes for each driver that were far from their current state. For example, the group defined the education driver as “the degree to which US elementary through higher education has developed curricula to produce science and technical talent.” Participants decided that in their future story, the US education system would substantially weaken, resulting in relatively few new science graduates, and that government funding, the second driver, would drop precipitously. Meanwhile, the group suggested that large-scale private investment in life sciences would soar.

Building a scenario based on the imagined future state of these drivers, the experts painted a picture of a world in which investor-funded technology companies would transform the traditional life sciences industry. In this world, life-science research draws more on big-data analytics than lab-bench experiments, and virtual talent easily supplants large supplies of scientists married to one location. The result is a more efficient and cost-effective industry.

By helping the group break free of the narrative fallacy, the exercise allowed them to rapidly build a scenario that stood in sharp contrast to their initial assumptions about the future — that a science-graduate shortage could only harm their industry.

Next, we asked participants to consider the strategic implications of this single future story. Here are a few of the provocative ideas the group advanced:

Pharmaceutical and biotech firms will make smaller bets, and more of them. Private money – not government grants – will fuel these bets.

There will be more R&D partnerships between private organizations like the Gates Foundation and biotech firms, as well as Big Pharma. Private foundations will supplement, but not replace, anemic government funding.

Crowd sourcing will become a fundamental R&D engine. This will allow corporations to continue to pursue R&D at near current levels without but at lower cost.

Big Data and analytics companies such as Google will re-shape life-sciences R&D, shifting the emphasis from hands-on laboratory experimentation to virtual research facilitated by ever-increasing computing power.

While a two-hour exercise could never substitute for a full-bore, months-long scenario planning activity, our experiment did get participants out of their usual frame of reference, opening their eyes to a possible future that would require very different types of investment and research. That this shift can happen in a matter of hours shows how workshops like this one can unstick executive thinking.

To make exercises like this work, a disciplined facilitator must prepare and guide the participants. They don’t need to be given a formal write-up, but relevant research materials must be handy (in our case, these included a handful short articles on life sciences growth trends, as well as a few news reports on STEM talent); and the facilitator must serve as an editor, pruning and clarifying the flood of ideas the group will generate. Given the tight constraints on such exercises, the facilitator has to carefully balance the time devoted to imagining a future world, and to “living” in it – that is, exploring how the envisioned future might actually affect participants’ businesses and industry.

Obviously, a brief workshop like this one shouldn’t be used to shape strategy; that requires true scenario planning. But we’ve found that such exercises work well to dislodge narrow thinking about the future, neutralize Kahneman’s narrative fallacy, and kick-start a strategy conversation.

[image error]

A Working from Home Experiment Shows High Performers Like It Better

Marissa Mayer’s move to ban working from home at Yahoo in 2013 caused a media firestorm over the costs and benefits of this rapidly growing practice. People lined up to defend both sides of the argument: Do work-from-home (WFH) policies encourage employees to “shirk from home” or are they an essential way to make our modern work lives actually work?

To answer the question systematically and scientifically, we and two of our students ran an experiment with Ctrip, China’s largest travel agent. Ctrip wanted to test a WFH policy both to reduce office costs (which were becoming an increasingly high percentage of total costs due to rising rents at the firm’s Shanghai base) and to reduce the firm’s high annual rate of staff turnover (50%). Ctrip management was concerned, however, that allowing employees to work from home could have a negative impact on their performance, so they wanted to test the policy before rolling it out to the entire company.

By way of disclosure, one of our research team members, James Liang, is also the co-founder and chairman of Ctrip. This provided us with excellent — and uncommon — access to both the experimental data and to the management’s views on working from home. As such, the experiment provided some insight into how large publicly-listed firms adopt new management practices, and helped shine a light on why so many firms fail to adopt potentially beneficial management practices.

Ctrip decided to run a nine-month experiment with its airfare and hotel divisions in the firm’s Shanghai headquarters call center. All employees with at least six months’ worth of experience with the firm were offered the option to work from home for four days each week. Of the 508 eligible employees, 255 volunteered to work from home and — after a lottery draw — those with even-numbered birthdays were selected for WFH arrangements while those with odd-numbered birthdays stayed in the office to act as a control group.

Further Reading

Getting Work Done (20-Minute Manager Series)

Leadership & Managing People Book

12.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Both home- and office-based employees worked the same shift period, in their same work groups, under the same managers as before, and logged on to the same computer system, with the same equipment, and the same work-order flow. The only difference between the two groups was the location where they worked. Ctrip keeps extensive, computerized records of the times employees are actually working, the sales they make and the quality of their interactions with customers, and this data allowed us to compare the performance of those at home and those in the office.

So what were the results of the experiment? First, the performance of the home-workers went up dramatically, increasing by 13% over the course of the nine months. This increase in output came mainly from a rise in the number of minutes they worked during each shift, which was due to a reduction in the number of breaks and sick days that they took. The home-workers were also more productive per minute, which employees told us (in detailed surveys) was due to the quieter working conditions at home.

Second, there was no change in the performance of the control group (and there were no negative effects seen from staying in the office). Third, the rate of staff turnover fell sharply for the home-workers, dropping by almost 50% compared to the control group. The home-workers also reported substantially higher work satisfaction and less “work exhaustion” in a psychological attitudes survey.

At the end of the experiment, Ctrip’s management team was so impressed by the success of the WFH policy that they decided to roll it out to the entire firm. They also offered both the original home-workers and the control group a fresh choice of work arrangements.

To their surprise, half of the home-workers changed their minds and returned to the office and three quarters of the control group — who had initially all requested to work from home — decided to stay in the office, as well. The main reason seems to be that people who worked from home were lonely. This unexpected outcome highlights the fact that before these types of management policies are implemented, their likely effects are as unclear to employees as they are to managers. It also helps to explain the typically slow adoption of such practices.

How do our findings compare with previous research? There is an extensive body of case studies on individual firms that have adopted WFH programs, and they tend to show large positive impacts. (See the studies here and here.) But the robustness of these results is hard to evaluate because of the non-randomised nature of the programs, both in terms of the selection of firms and the selection of employees who worked from home. This self-selection effect is evident even in the case of Ctrip: when the firm allowed a general roll-out of home-working, high-performing employees typically chose to move home while low-performing employees chose to return to the office. We suspect that the most driven employees were more willing to work from home, knowing they could stay focused away from the office, while the more distracted tended to worry about the consequences of sitting all day next to the fridge and the television — the biggest enemies of working from home.

What does our experiment tell us about what other companies can expect if they allow employees to work from home? Clearly, Ctrip’s call centers are different from many work contexts: behavior and performance at Ctrip are easily tracked, bonuses make up almost half of salaries, and the work could be done on an individual basis with limited need for collaboration or innovation. While many firms that depend on innovation discourage WFH because they want interaction among employees, many occupations have these same characteristics as at Ctrip. Examples include coding, technical support, telesales, and basic accounting. Moreover, two WFH benefits would probably also transfer to many jobs: the increased productivity that comes from the peace and quiet of home and the large drop in turnover rates due to greater employee job satisfaction.

So our advice is that firms — at the very least — ought to be open to employees working from home occasionally, to allow them to focus on individual projects and tasks. We encourage companies to do a trial the next time an opportunity presents itself — like bad weather, traffic congestion from major construction, or a disruptive event (such as a city hosting the Olympics or the World Cup) — to experiment for a week or two.

We think working from home can be a positive experience both for the company and its employees, as our research with Ctrip showed. More firms ought to try it. And our advice to Yahoo is to give working from home a second chance — it is critical for retaining and motivating your key employees, and is an essential part of the 21st century office.

[image error]

January 22, 2015

What Netflix and Starbucks Know About Cash Flow

Netflix just announced its best quarter ever. Its subscriber count went up 13 million worldwide, and investors are enthused. Its U.S. business ended 2014 with 39.1 million subscribers, not far off our 2012 prediction that there were at least 40 million U.S. households who seemed likely to sign up for its streaming video service.

The success Netflix is enjoying was far from certain if you recall the summer of 2011. That’s when the company suffered through the Quikster controversy and a protest over its price increase. I was in the minority when I wrote that the price increase was a good thing. I wrote that not as a growth strategist, but as a loyal, happy Netflix consumer. I was very pleased with my decade-long relationship with Netflix. I trusted the brand. I knew my demand for streaming would go up over time. And I felt certain that Netflix would take my extra $1 per month and invest it wisely for my benefit.

And it did. It took my dollar, combined it with many dollars from like-minded customers, and invested it in things like original content, including “House of Cards,” for which Kevin Spacey won the Golden Globe.

Netflix’s ability to make a big bet like this stemmed from its certainty of latent demand—in other words, that people signing up for a monthly service showed a real commitment not only to become customers but to stay customers. For that to happen, consumers must know their demand for a product or service is predictable and likely to go up. The consumer must also have sufficient trust in the brand’s willingness and ability to understand, predict, and invest in meeting that demand.

Both of these were true for Netflix. Americans’ demand for media is very high. As Steve Hasker, Nielsen Global President, says, American consumers now have a second 40 hour per week job: consuming media, much of which now streams over phones and computers. And consumers could be confident that Netflix, with its recommendations engine, could reliably meet that demand.

When customers can foresee their demand for a product or service rising and trust a company enough agree to a monthly payment (thus providing regular cash flow), they are essentially enabling the company to build what customers want. Think of it as Kickstarter for established companies and their consumers.

Converting consumer certainty into consumer cash flow is a key part of making money from digital business models, many of which use subscription models. From a consumer standpoint, digital payments can be more convenient and are potentially safer. But mostly it taps into the wisdom from Mark Cuban of creating as much transactional value from cash as possible. When consumers are certain about their latent demand, they are increasingly willing to provide positive cash flow in exchange for better value or more benefits. “Saving 30 to 50% buying in bulk — replenishable items from toothpaste to soup, or whatever I use a lot of—is the best guaranteed return on investment you can get anywhere,” as Cuban says.

Insight Center

Making Money with Digital Business Models

Sponsored by Accenture

What successful companies are doing right

Improving cash flow is extraordinarily healthy for any business. If you can better predict consumer demand with more certainty, whether via subscription business models like Netflix or Amazon Prime, you can improve forecasting. This allows you to better manage operating and capital expenses. It can also improve working capital. Consider the Starbucks loyalty card, which consumers buy pre-loaded with cash. In early 2014, Starbucks said consumers loaded $1.4 billion to those payment platforms. According to Bloomberg Businessweek, in 2013 Starbucks made $146MM on interest investing the float, or 8% of total profit.

Digital payment innovations that tap into consumers certain about their latent demand are at the heart of successful digital business models. And brands that have earned high degrees of trust with great loyalty and passion—whether in a sexy category or not—are in the best position to capitalize on it.

[image error]

Evaluate Your Leadership Development Program

Despite studies showing that succession is an essential part of strategic planning, many companies ignore leadership development to focus on more immediate challenges. But your organization’s future success depends on identifying and developing the next generation of its leaders.

According to a 2014 survey from Deloitte, 86% of business leaders know that their organizations’ future depends on the effectiveness of their leadership pipelines — but a survey of 2,200 global HR leaders found that only 13% are confident in their succession plans, with 54% reporting damage to their businesses due to talent shortages. To improve your leadership development strategy, look at the criteria you’re using to identify potential leaders, what you’re doing to assist with their development, and how you’re measuring their success.

Establish a set of clear and defined leadership competencies, so HR and other stakeholders know whom to fast track for leadership. Too often, companies demand a laundry list of vague qualities, such as creativity and innovation, which fail to align with organizational needs. Or they rely on subjective metrics, such as likability, loyalty, whether someone is “due for promotion,” etc. This puts you at risk of missing out on true top talent and promoting the wrong people. And it confuses young, promising managers about what skills and behaviors they need to develop to advance their careers.

A McKinsey & Company report also said, “Too many training initiatives we come across rest on the assumption that one size fits all and that the same group of skills or style of leadership is appropriate regardless of strategy, organizational culture or CEO mandate.”

Senior leaders must determine the specific leadership skills and behaviors needed to successfully execute the company’s strategy. Whether your organization is planning a merger, entering new global markets, ramping up sales operations, or creating a flatter corporate structure, it’s important to first think about what skills are needed to successfully execute the initiative. For example, when a U.S. company promoted someone to head its product and content development unit in India, it assessed what skills would enable him to succeed: cultural sensitivity, an ability to build multicultural teams, a flexible communication style, and a high tolerance for uncertainty. With executive coaching and targeted leadership development, the executive was able to transition with the necessary competencies.

Aside from the skills needed to execute on specific strategy initiatives, research has noted that high-potential leadership talent generally demonstrates a drive to excel, a “catalytic learning capability,” and an enterprising spirit, coupled with the ability to sense real risk. Focus your leadership development program on strengthening employees’ ability to deliver strong and credible results, to master new types of expertise, and to uphold behavioral standards that reflect the company culture and values. Credibility is especially important, as building trust and confidence among colleagues leads to an ability to influence a wide array of stakeholders.

Consider how leadership talent is fast-tracked within your organization. Studies have shown that leadership development is most effective when high-potential employees are formally identified as such. Organizations must be clear about whom they’re eyeing for leadership and how much they’re investing in them. This investment can take the form of enhanced development opportunities, such as special assignments or training, rewards and incentives, greater authority, additional resources, and increased feedback.

Pair potential leaders with mentors and executive coaches to aid in their development. Give challenging job-specific assignments that tie in to the overall business strategy, and then provide more frequent feedback so adjustments can be made in real time. The key for these interventions is to keep the momentum going. These aren’t one-off initiatives or stand-alone workshops without follow-up. You want to sustain and expand your development program to address business challenges in real time.

Create a process for measuring overall performance and growth. Once the necessary leadership competencies have been determined, targeted assessments at various stages of a development program can help keep future leaders on track. There are numerous assessments that measure everything from problem-solving and decision-making styles to emotional intelligence to identifying one’s approach to innovation. Using 360-degree assessments throughout the program can show you whether employees are learning the desired leadership competencies or whether adjustments need to be made.

Some companies have proven themselves to be models of effective leadership development. Look at P&G, IBM and GE — the top three companies for leaders, according to a ranking by Chief Executive. P&G and IBM both make developing leaders from within a priority and invest heavily in training, and IBM has a standardized leadership track. GE has shifted its leadership development focus under new CEO Jeff Immelt, putting greater emphasis on drawing innovation and new ideas out of its high potentials.

Organizations that fail to develop strong future leaders will inevitably see that high-potential talent — already in short supply — head elsewhere. By then, expensive executive searches may need to be repeated, there may be a loss of strategic momentum and investor confidence, and the company may flounder with a CEO who is out of step. It’s time to protect your company from inadequate leaders, who, at best, hurt a company’s bottom line, and at worst, threaten its legacy.

[image error]

Why a Messy Workspace Undermines Your Persistence

The disorganized accumulation of papers and coffee cups scattered across your desk may help you project the impression that you’re working at full throttle, but in fact it’s probably dragging you down. We’ve found that people sitting at messy desks are less efficient, less persistent, and more frustrated and weary than those at neat desks.

But wait, you may say. No one who has worked in a busy office for more than a week can possibly keep a neat desk — the work comes at you too fast. Or you may say that you like your mess, that it’s as comforting as a little nest. To which we say yes, it can be challenging to keep a desk neat. And yes, a mess can be comforting, even freeing, in a sense: You don’t have to worry about things becoming disordered, because they’re already disordered.

But look at the data:

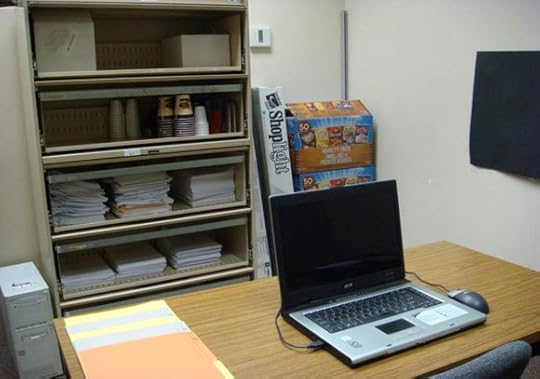

In one of our experiments, more than 100 undergraduates were exposed either to an uncluttered space or to a work area where papers, folders, and cups were scattered over shelves, a desk, and the floor, like so:

Measuring the impact of mess. Source: Boyoun (Grace) Chae and Rui (Juliet) Zhu

Measuring the impact of mess. Source: Boyoun (Grace) Chae and Rui (Juliet) Zhu

Then, in a separate room, they were asked to undertake what was described as a “challenging” — actually, it was unsolvable — task that consisted of tracing a geometric figure without retracing any lines or lifting the pencil from the paper. Those who had been exposed to the neat environment stuck with the task for an average of 1,117 seconds before giving up, more than 1.5 times as long as those who had been exposed to the messy space (669 seconds). Other experiments produced similar results.

Persistence in a frustrating task is a classic measure of what’s known as self-regulation, which is essentially your ability to direct yourself to do something you know you should do. Self-regulation can be undermined by depletion of mental resources, and that’s exactly what we think was going on. The mess posed a threat, in a sense: It threatened participants’ sense of personal control. Coping with that threat from the physical environment caused a depletion of their mental resources, which in turn led to self-regulatory failure.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Getting the Right Work Done

Leadership & Managing People Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

The evidence for this chain reaction comes from another aspect of the experiment: If participants wrote about their personal values, an exercise known to restore mental resources, the disorganized environment had no effect on their persistence on the fiendish task.

So even though it can be comforting to relax in your mess, a disorganized environment can be a real obstacle when you try to do something.

And although we don’t have data to back this up, we conjecture that a mess of your own creation may affect you even more strongly than a mess that’s been imposed by someone else. A self-created mess can become overwhelming because it serves as evidence that you’re unable to control your environment.

We’re aware that other researchers have found there’s a benefit to a disordered environment: It seems to help people break from convention and be more creative. A team led by Kathleen D. Vohs of the University of Minnesota found that people in a room where papers were scattered on a table and the floor came up with five times more highly creative ideas for new uses of ping-pong balls than those in a room where papers and markers were neatly arranged.

The two sets of findings aren’t necessarily contradictory. In fact, it could be that the depletion effect of disorder caused people to engage in primarily affective or divergent thinking, which enhanced creativity.

In any case, our research has made us think about other factors at work that may deplete employees’ mental resources and therefore undermine their self-regulation and persistence. One possibility that comes to mind is extreme self-consciousness — ruminating about others’ perceptions. Employees might find it depleting to wonder: What do people think of me? Of my work quality? Of my appearance? It’s very possible that this kind of thinking hurts performance.

It can be challenging to turn off rumination. In comparison, solving the messy-environment problem is relatively easy. Because of our research, both of us have become more aware of the value of an ordered environment. We both keep our desks neat, and one of us (Chae) makes sure to maintain an orderly home. The reasoning: A neat environment at home allows her to head into work on Monday morning feeling fresh and restored.

[image error]

An Approach to Ending Poverty That Works

Ending extreme poverty by 2030 is the BHAG – the big, hairy audacious goal – of our generation. While skepticism abounds, momentum is on our side, with poverty rates falling in every region of world.

Unfortunately, these trends still have little to no impact on the lives of a critical and chronically marginalized subset of the extreme poor around the world, those living on less than 60 to 70 cents per day. At BRAC, where I work, we call this subset the “ultra-poor.” Microfinance and other market-based interventions don’t generally reach them. Predominantly women, they face chronic food insecurity, malnutrition, gender discrimination and often abuse. They also bear the brunt of climate change— especially in rural areas where inclement weather and the increasing frequency of storms can hurt agricultural yields and contribute to malnutrition — not to mention countless other external challenges.

If we’re to end poverty, we can’t ignore them. All of us — researchers, policymakers, governments, social entrepreneurs, nonprofit development groups, microfinance institutions, corporations, and philanthropists — have a role to play in bringing them into the widening zone of prosperity. And we may have found a way to do this.

BRAC began grappling with the problem of the ultra-poor in the 1990s. Despite decades of success fighting ill-health, illiteracy, and poverty, BRAC saw its programs still weren’t reaching women trapped in this chronic cycle of dire poverty.

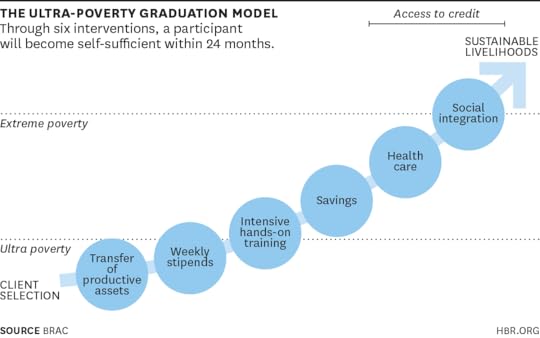

We tested different approaches and in 2002, we began deploying a new set of interventions now known as the “graduation” approach, which provides these women with a host of services and benefits to move them out of ultra-poverty and eventually into sustainable livelihoods. That methodology has in turn been tested by other nonprofit organizations in other contexts, with pilots in eight countries as varied as Yemen, Ethiopia, and Haiti, with support from the World Bank’s Consultative Group to Assist the Poor, the Ford Foundation, and the MasterCard Foundation.

Our research has shown that the vast majority of participants in these programs – 75 to 98%, depending on the geography – not only leaves the category of ultra-poverty within 24 months, but remains on an upward trajectory even four years after they’ve stopped receiving direct benefits.

What sets the graduation approach apart from other attempts to reach the poorest is, in part, the mixed methods used. Discussion abounds in the development sector today about the best ways to empower the poor. Do you give them cash or assets? Is it better to attach conditions, or do the poor know best how to spend their money? BRAC’s short answer to these questions is yes, all of the above. That’s why we’ve taken a multi-intervention approach.

And perhaps we’ve overlooked the most important question of all: Are we really reaching those most in need?

Targeting is crucial. We need to make sure scarce resources are deployed efficiently. To do this, BRAC first identifies regions with high concentrations of ultra-poor. Then, using a method called “participatory wealth ranking,” we establish a group of 40 to 50 villagers and community leaders who rank the wealth of each household in the area. Community members outline their own criteria and identify the poorest living among them. BRAC staff then goes door-to-door to visit selected participants and verify their circumstances with questionnaires. These surveys vary by region, but may include how many meals she eats a day, number of people in her household, access to clean drinking water, etc. Including the community in this process also fosters a support network for participants as they go through the program.

From there, participants receive set of six interventions over the course of 24 months. They get a productive asset, like a goat or a cow; intensive hands-on training that includes livelihood training to maximize revenue from their asset and in-person coaching in the form of a weekly visit from a BRAC worker; a weekly cash stipend to give them some breathing room while they learn their new livelihood; healthcare recommendations; and financial planning services with additional support from the community.

It is an intensive, integrated approach that works. It probably sounds expensive, too, but it isn’t as costly as one might think. It costs less than $500 per person for the full two years in Bangladesh. The long-term drag of not intervening — namely that of malnutrition, resulting in stunted growth and intellectual development, untapped labor potential, and so on — is estimated to cost $3.5 trillion each year, 5% of the global gross domestic product. To put things in perspective, reaching every ultra-poor family in Bangladesh (6 million families or 17% of the population at $500 per household) would cost the country $3 billion, less than .5% of GDP over six years.

Munshi Sulaiman, previously a researcher at BRAC and now pursuing post-doctoral studies at Yale, is looking at the cost-effectiveness of graduation-style programs in several countries. He is authoring an as yet unpublished study comparing these programs to 50 other government and NGO livelihood and cash transfer programs in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

“We found the graduation approach isn’t necessarily more expensive than other programs of a comparable scope,” Sulaiman says. “In some cases it actually works out to be cheaper, especially when you take effectiveness into account. These graduation programs are more consistent in achieving impact than other programs we looked at.”

Dozens of governments are now looking at ways to integrate graduation programming into their social protection policy and efforts. The Kenyan government recently hired BRAC to assess the viability of the graduation approach in some of its most difficult, climate-change prone areas where droughts have caused displacement and food insecurity.

I’d like to see the private sector, philanthropists, and social entrepreneurs throw their weight behind this idea to end poverty for all.

There’s a lot of talk about resilience in the world these days; the ultra-poor are the paragons of resilience. We need to tap into their creative power. We need to imagine a world where they don’t just survive – they thrive.

[image error]

99% of Networking Is a Waste of Time

Building the right relationships — networking — is critical in business. It may be an overstatement to say that relationships are everything, but not a huge one. The people we spend time with largely determine the opportunities that are available to us. As venture capitalist and entrepreneur Rich Stromback told me in a series of interviews, “Opportunities do not float like clouds in the sky. They are attached to people.”

To say Stromback is a great networker is an understatement: he was introduced to me as “Mr.Davos” for good reason. He has spent the last ten years attending the Mecca of networking events — held by the World Economic Forum every year in Davos-Klosters, Switzerland. The New York Times described him as the “unofficial expert on the Davos party scene.” Every year, he knows where the big events will be because he has so many people feeding him information, and he makes sure to be at the center of the action. Over time, this has turned into a surreal set of relationships. When a Middle East Prince was asked to meet with some Fortune 500 CEOs, he reached out to Stromback to attend and facilitate the meeting; when the Vatican was trying to negotiate a peace treaty of sorts they asked Stromback to help.

People also come to him because they feel they’re not getting enough value at Davos. “They chase for more and get less,” says Stromback, who finds the notion almost unimaginable. “The forum is the most influential community in the world. It’s the United Nations, G20, Fortune 500, Forbes List, tech disrupters and thought leaders all brought into one.”

Much of what he has learned from a decade at Davos flies in the face of generally-accepted networking advice. Below are snippets of my conversations with Stromback about his counterintuitive advice. Use it at Davos — or any other networking event:

Don’t care about your first impression. “Everyone gets this wrong. They try to look right and sound right and end up being completely forgettable. I’m having a ball just being myself. I don’t wear suits or anything like that. I do not care about first impressions. I’d almost rather make a bad first impression and let people discover me over time than go for an immediate positive response. Curiously, research I read years ago suggests that you build a stronger bond over time with someone who doesn’t like you immediately compared to someone who does. Everything about Jack Nicholson is wrong, but all of the wrong together makes something very cool.”

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Getting the Right Work Done

Leadership & Managing People Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

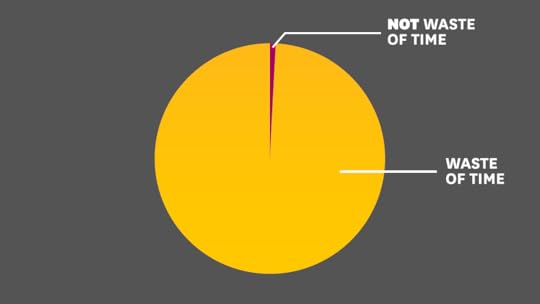

99 percent of any networking event is a waste of time. “99% of Davos is information or experience you can get elsewhere, on your own timeframe and in a more comfortable manner. When I had my white badge access [an official pass to the conference center] — which I don’t bother with anymore — my friends would laugh because I never went to a session. [But] that’s not where the highest value is. What you can’t get outside of Davos is the ability to have so many face-to-face interactions which either initiate or further key relationships.”

Sleep from 4-8PM every day. “I nap every day in Davos sometime between the hours of 4-8pm. It’s the most efficient time to catch up on sleep so I can be fresh when the time is opportune. The opportune moments happen while dancing at one of the nightcaps or at a chateau where only a select group of people is invited. The conversations there can go on until the early morning hours.”

The key to networking is to stop networking. “Nobody wants to have a ‘networking conversation,’ especially those who are at the highest levels of business and politics. They are hungry for real conversations and real relationships. It just has to be authentic, genuine and sincere. I don’t look at people’s badges to decide if they are worth my time. Davos is 3,000 influential people and I need to be selective, yet authentic — focused, yet open to possibilities. In the end, I put myself in the most target-rich area and then just go with the flow and spend time with who I enjoy.

You’re not required to go to the big-name parties. “I maintain a broad and deep global network of C-level relationships without wining and dining face-to-face with people 90% of the time. But you need to know where people will be. For example, one year I told someone, “Don’t go to the Bill Gates party this year.” He asked me why? And I told him, “Because no one will be there.” He went and couldn’t believe I knew ahead of time. But I just knew the party was at the wrong time in the wrong location. It’s all about understanding where to be and when.”

Live in Detroit (or somewhere like it) the rest of the year. “Most people who are focused on building relationships at the highest levels live in London, New York City and Washington, D.C. They are immersed in the scene 24-7. I prefer to be disengaged 90% of the time. I live in Bloomfield Hills, in the Detroit area, and I don’t do anything social there. I love Detroit because no one comes to visit, and there are very few distractions. This is my escape for crucial family time. Being removed from the fray 90% of the time reduces a lot of drama.”

As Stromback — a self-declared essentialist — put it, “Davos is 99% distractions; you have to know what to avoid.” When asked how he would respond to the idea that most people don’t like networking because it’s time intensive and distracting from their “real work” he said, “The answer is to be extremely efficient and focus on what is truly essential.” This jibes with my own personal point of view on the world: Almost everything in life is worthless noise, and a very few things are exceptionally valuable. This is as true in networking as it is in almost every other area of life.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers