Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1331

January 12, 2015

Free Community College Would Help Fix the Skills Gap

On Friday, President Obama proposed a program that would make community college tuition free to most students. Such a program might go a long way to providing employers with a better-skilled workforce; it would also restore growing economic opportunity for many workers.

Modeled after a program that is starting up in Tennessee, Obama’s proposed program would pay tuition for community college students who are enrolled in a degree program at least half time and who maintain a 2.5 grade point average. The Federal government would kick in $60 billion over 10 years to cover 75% of the cost; states would pay the remainder.

Workforce experts see community colleges as essential for providing workers with “middle skills,” especially for jobs that require some post-secondary technical education and/or on-the-job learning (see “Who Can Fix the ‘Middle-Skills’ Gap?”). Currently, 26% of jobs require less than four years of post-secondary training; 16% of jobs require on-the-job training of more than six months. Community colleges provide a wide range of technical training and many of these vocational programs include work-study components at local employers, providing critical job experience.

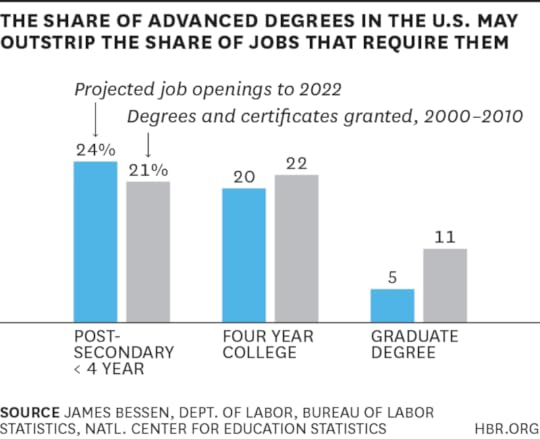

But the evidence suggests that while demand is growing for middle-skill workers, the U.S. educational system is turning out relatively fewer graduates at this level. This mismatch contributes to employers’ perceptions of a “skills gap”. The chart below shows the educational requirements of the jobs that will be created between 2012 and 2022, compared to the share of diplomas generated over the past decade. While 24% of job openings will require less than four years of post-secondary training, this category only accounts for 21% of the diplomas granted (including both associate degrees and non-degree certificates). By comparison, a larger portion of four-year and graduate degrees are awarded relative to job openings requiring these higher degrees.

New technology at least partly explains the rising relative demand for mid-skill workers. Historically, new technologies initially demand relatively educated workers, but as they mature and technical knowledge becomes more standardized, demand shifts to mid-skill technical occupations. While many of the first computer programmers were PhD mathematicians, few are today. In healthcare there has been a major shift of jobs from the most highly educated doctors and dentists to mid-skill workers including nurses, dental hygienists, medical assistants and a wide range of health technologists. Over the last two decades, two million mid-skill jobs have been created in health occupations beyond what can be explained by the overall growth of the healthcare sector.

But our educational institutions are not keeping up with this shift. The chart shows that middle skill workers are being undersupplied relative to workers with four-year or graduate degrees. Obama’s program might help fix that imbalance, benefiting both employers and employees. Indeed, mid-wage, mid-skill jobs in mature industries have been particularly hard hit by automation, leading to a “polarization” of job opportunities. But new jobs are being created that demand new skills, skills that community colleges can often provide. Free tuition may help bolster economic opportunity for the less privileged.

As the Wall Street Journal notes, presidents since Ronald Reagan have touted two-year colleges as a cure for problems with both job training and educational opportunity. Yet the funds haven’t followed the rhetoric. Instead, policy has favored four-year institutions. Over the last decade, one study found that spending per pupil at private research universities increased by $14,000 after adjusting for inflation; meanwhile spending per student at community colleges remained unchanged. In total, public research universities receive about twice as much government funding per pupil as do community colleges, not counting tax subsidies on donations and endowment funds.

Yet, arguably, community college students are more in need of assistance, including remedial education. As one study put it, “two-year colleges are asked to educate those students with the greatest needs, using the least funds, and in increasingly separate and unequal institutions. Our higher education system, like the larger society, is growing more and more unequal.”

Perhaps President Obama’s proposal will fare no differently than past ones. That would be a shame. Though some critics argue that this proposal is not the best way to promote mid-skill education it is nevertheless a step in the right direction. Moreover, the president’s proposal helps put a spotlight on the middle-skills gap. As Senator Angus King of Maine argues: “It’s not necessarily all about bills and funding. Sometimes it’s about the bully pulpit and raising the profile of an issue.” If America hopes to rebuild its middle class, technical education needs all the profile it can get.

[image error]

Ethical Consumerism Isn’t Dead, It Just Needs Better Marketing

Ethical consumerism is the broad label for companies providing products that appeal to people’s best selves (for example, fair trade coffee or a purchase that includes a donation to a charitable cause). Now that the general idea of combining ethics and shopping has become a mainstream concept, there is a developing a backlash against the idea that consumers might effect change through their purchasing habits. This pessimistic stance stems primarily from the lower sales of ethical brands. “If consumers cared about moral issues,” the argument goes, “then companies and brands that did the right thing would have a larger market share. It is clear people must not care about these issues and so ethical consumerism is going to fail. We cannot shop our way to a better world.”

I understand the attraction to markets and their efficiency; I am a marketing professor. I am also a psychologist, though, and a “behavioral economist,” which in my case means someone who studies the psychology of market decisions with an eye to economic theory and when it does (and does not) explain what people do.

I worry that the pessimism about ethical consumerism gives companies the idea that they should not actively pursue the moral high ground because consumers will not reward them for it. I also worry that consumers will give up on trying to effect change through purchasing, because they believe that the aim is hopeless. On the flip side, it is pleasing to imagine the market fixing societies’ ills, to provide a nice antidote to the common idea that the marketplace and consumers are amoral and solely profit-driven.

And yet the hopelessness of ethical consumerism is echoed everywhere, in the business press, in (some of) my students’ resistance to studying moral issues in a business framework, and in conversations I have on airplanes, at parties, and with colleagues. An often-quoted 2010 Wall Street Journal article, “The Case Against Corporate Social Responsibility,” laid out the argument clearly: “the fact is that while companies sometimes can do well by doing good, more often they can’t. Because in most cases, doing what’s best for society means sacrificing profits.” Indeed, regulation would be a more immediate and effective solution to unethical consumerism than hoping for market change. But let’s be honest– widespread sustainability regulation is not coming any time soon and would likely have some negative consequences even if it did.

So, for now we are stuck with hoping that consumers will drive change. I’m still optimistic about this, for one primary reason: Even though market share for sustainable brands is not always as high as for other brands, I do not think current sales are the best barometer of ethical sentiment. Until marketing practices do the best that they can to guide ethical consumerism, we can’t really draw any conclusions about what current market share means.

My first piece of evidence may seem obvious, but it seems to get lost whenever people discuss market behavior. The truth is, most people will (at least sometimes) behave ethically even when they have to sacrifice something, usually cash, for their morals. Billions are given to charity every year ($335.15 billion in the US alone in 2013 according to Charity Navigator). This past year, thousands of people dumped ice water on their heads and then gave a total of $115 million (as of this writing) to help support research for ALS. So clearly there is some human willingness to part with one’s money for an ethical cause.

And yet sometimes it is tempting to believe that shopping behavior is more indicative of people’s “real” selves than behaviors such as giving to charity, because market tradeoffs are expected to be more accurate revelations of deep, actual sentiment that strip away any nonsense and get to the real, perhaps ugly, truth. As economist Paul Samuelson explains, market preferences are “revealed preferences” that make people put their money where their mouth is.

But people regularly buy hybrid cars, organic foods, environmentally-friendly detergents and Warby Parker glasses. Why? I would chalk a lot of it up to really effective marketing. Yes, there are other benefits to those products – saving money on gas, health benefits, style, and comfort – but isn’t it a marketer’s job to tout those and other benefits, too?

Pessimism about ethical consumerism rests firmly on the assumption that consumers have one, stable utility structure and they express that utility in their purchasing. The problem is, human psychology does not work like that—people do not have only one value for things and they do not have a stable and consistent utility structure. Modern treatments of economic behavior have rejected the simplistic one-preference idea of human values and decisions for quite some time. As Daniel Kahneman’s explains in his wonderful book, Thinking Fast and Slow, a survey of all of his (Nobel-prize winning) research over the last forty years or so: “it is self-evident that people are neither fully rational nor completely selfish, and that their tastes are anything but stable.”

My primary research area has been how ethical decisions are especially squirrelly and inconsistent, flip-flopping all over the place, depending on the situation. To provide a personal example, I was just on vacation at Disney World and was offered the “green package,” which would mean not washing the towels while I was there, and also not tidying up the room. Consider: I not only value being environmentally sensitive, but also was in the middle of writing this very article. Nevertheless, I rejected the green choice, because I wanted them to tidy the room and they had mentioned the room tidying last, so I weighted that information more highly in my decision.

One of my favorite quotes, by Mark Sagoff, expresses this type of inconsistency: “I love my car; I hate the bus. Yet I vote for candidates who promise to tax gasoline to pay for public transportation. I send my dues to the Sierra club to protect areas in Alaska I shall never visit…I have an “Ecology Now” sticker on a car that drips oil everywhere it is parked.” Sagoff is focusing on inconsistencies between political and consumer behavior within a person, but the inconsistencies exist even across purchasing contexts.

For example, in a paper published in the Journal of Marketing Research with my colleague Rebecca Naylor, we showed that how much people cared about whether a shampoo company conducts animal testing depended on a simple shift in context. We asked participants to consider a set of actual shampoos that differed on many attributes including animal testing. There was a large set that, we told them, would need to be narrowed down before they picked one shampoo to keep (and we did actually give them the shampoo they chose). We instructed half of them to indicate which shampoos they wanted to consider further, and half to indicate which ones they did not want to consider further. Consistently, and surprisingly, the shampoos picked for further consideration (i.e., those that were included versus those that were not excluded) differed. In the including case, ethics played very little role in choice but in the excluding case it loomed significantly larger. In the end, being told to think in terms of excluding led to more ethical decisions.

In another paper, published with Kristine Ehrich in the same journal, we showed that people who care about ethical issues such as child labor will, strangely enough, avoid finding out whether their products are made using child labor. But then if you give them the information they will incorporate it into their purchasing. Ethical information is difficult to process and it is common for consumers to want to remain willfully ignorant of it. I myself behave in this manner at least once a week.

I could list a half dozen or more other examples, but suffice it to say that there is ample research to match the anecdotal evidence that ethical consumer values exist, but the context has to draw them out. This is the marketer’s task. I think a useful analogy to ethical consumerism is the tradeoff between vices versus virtues. Decades of research in psychology and economics (nicely summarized in Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s book, Nudge) establishes that people often want something different in the short term (e.g., chocolate cake) versus the long term (e.g., being skinny). Likewise, people both want to be ethical and they want to ignore ethics. As Thaler and Sunstein explain in the context of virtues such as eating healthy, exercising and saving money, sometimes all that is needed is a contextual push toward better behavior — a nudge.

Marketers are all about nudging, so why not use it to promote more ethical consumer behavior? Consumers are likely to be especially brand loyal if their deeply-held values are engaged in their purchasing. Consumer engagement and commitment is priceless: ethical brands are more likely to encourage this engagement. Consumers walk around with Whole Foods branded merchandise all the time; it is difficult to find similar examples for less ethical retailers focused solely on price. If low price is all a company offers, it is easy enough for the consumer to walk away when a lower price comes calling.

Imagine if your competitors have all fallen prey to pessimism about ethical consumerism, but you know better. You know consumers have ethical motivations, and you know you can help them express those motivations. You realize that past market share doesn’t have to mean consumers aren’t hungry for the chance to do good while they spend money. By remaining optimistic, you have both made a difference in a larger sense, and you have found a sweet spot in the competitive landscape where you can grow profits and your brand.

[image error]

Office Politics Isn’t Something You Can Sit Out

Ask most people about workplace politics and they’ll say they’d prefer to avoid it. Yet, most also know that developing political competence is not a choice; it’s a necessity. The ones who who manage to reach the inner circle are at a great advantage. They get more done, but they are also recognized for their competence and ability to manage interpersonal relationships.

When you don’t understand the political landscape of your company, it shows. Questions arise. Can you go the distance, handle the rough spots, inspire the troops, get the job done, and garner respect? Young workers, especially, often make the mistake of assuming that understanding office politics isn’t necessary. That assumption leads to the loss of valuable learning time. When you’re no longer so green, and start to become a threat to others, things change. Political know-how becomes important — and those who fail to develop such skills are often the ones who get left behind.

Handling public put-downs, knowing with whom to speak about what, understanding how to move projects along, realizing the right times to make yourself visible and how to make your work relevant are only a few important skills. Achieving a high level of political expertise is not easy — nor is maintaining it. Mastery will never be total or permanent. After all, the inner circles of business shift. Even the best senior-level engineer may stall out because she lacks the ability to manage or avoid the political traps that ensnare so many otherwise competent people.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Office Politics

Communication Book

Karen Dillon

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

So do we all need to play games every day? Not necessarily. The degree to which you engage in politics depends on where you work. Consider these four levels of politics in organizations: minimally, moderately, highly, and pathologically political:

In minimally political companies what you see is largely what you get. Standards for promotions and expectations for managing and leading are made clear. There is a sense of camaraderie. Rules are occasionally bent and favors granted, but underhanded forms of politics are avoided. This is the type of organization in which those with little understanding of or interest in politics — the purists among us — can thrive.

Moderately political organizations also operate largely on widely understood, formally sanctioned rules. Political behavior, where it does exist, is low-key or deniable. Conflicts are unusual, as there is a team player mentality. This environment works for people who’d rather not engage in politics, but are capable of managing or living with pockets of political activity.

The highly political arena is where not understanding politics and being unwilling to engage in some of its more surreptitious forms can exact a price. Formally sanctioned rules are only invoked when convenient to those with power. In-groups and out-groups are usually well defined. Who you know is likely to be more important than what you know. Working in organizations like this can be very stressful. Political street-fighters who “read the tea leaves” and “know the ropes,” as politically adept business people I’ve interviewed call it, do far better than those who don’t keep abreast of the games being played.

One organization where I consulted was highly political. Cliques had formed. People slipped into each other’s offices before meetings to share the latest offense of the out-group and to plan their revenge. In highly political organizations like this one, there usually isn’t one person responsible for the climate. Political activity is relational — even if only a couple of people are engaging in negative types, others get pulled in and playing-along-to-get-along becomes the norm.

The most virulent forms of business politics occur in pathologically political organizations. Daily interaction is fractious. Nearly every goal is achieved by going around people or formal procedures. People distrust each other — and for good reason. Out of necessity, people spend a good deal of time watching their backs and far less gets done than might otherwise be achieved.

Management expert Henry Mintzberg wrote of these types of organizations: “Much as the scavengers that swarm over a carcass are known to serve a political function in nature, so too can the political conflicts that engulf a dying organization serve a positive function in society. Both help to speed up the recycling of necessary resources.” The only problem: These types of organizations take a while to die, and so a lot of talented people are caught up for quite a while in politics run amuck.

Fortunately, most of us don’t work for pathological organizations and we don’t drive to work wondering who will be figuratively poisoning our wells today. But even more rare is the organization where politics of any type barely exists. Wherever there is competition, especially for scarce resources, you’ll find politics.

So, how do you know which type of organization you’re working in, and how do you develop the skills to survive there, especially if it’s not in your nature to play politics? You can wait around for the organization to address negative politics head-on. It happens. And when it does, all boats rise. That’s why more organizations should actively foster constructive politics. But it may take a long time for your own organization to see the light and take action, and in the meantime you have a career to manage, to say nothing of keeping your sanity. So, start by identifying the type of arena in which you work, as well as your own personal style. Is there a good match? If you’re a purist working in a highly political environment, for example, you need to become more street smart or move on. If it’s not in your nature to be political, then the latter may be the better choice. But it never hurts to learn about politics and to stretch your style to accommodate a variety of levels:

Read about workplace politics and observe those who are skilled. Treat it like any other important area of business expertise.

Try tweaking how and when you say things. For instance, if others expect you to be demure and let them steal your ideas at meetings, learn some ways of asserting yourself. For example, you could say: “I mentioned that option earlier. I’d like to expand upon it a bit more now.”

Consider to whom you’re giving power and alter that if it’s getting you nowhere. Find another way to get what you want or change the goal.

Break out of dysfunctional patterns, such as repeatedly taking on low visibility, low value projects to please someone; always having to be right rather than crediting others for their input; or failing to choose your battles instead of learning what matters most.

Be less predictable, because predictability is the kiss of death in political organizations. For example, if you’re constantly attempting to prove yourself, but you lack guidance and a support network, you can leave yourself open to political foul play. The more predictable you are, the easier it is for others to manage you to their own advantage.

Political proficiency is not a choice at work, but it’s a necessity that can be improved at any point in your career. For each and every one of us, the sooner that happens, the better.

[image error]

What Business Can Learn from Government

In 1989, Peter Drucker wrote an article for Harvard Business Review titled “What Business Can Learn from Nonprofits.” As the story goes, the concept was so counterintuitive that readers thought the magazine had made a huge typo; surely, it had gotten things backwards.

We wouldn’t be surprised if readers had the same reaction upon seeing the headline that sits atop this piece. What, after all, could government possibly teach business?

As it turns out, plenty. Despite the public sector’s blanket reputation as a bureaucratic backwater, there are countless examples of civil servants doing highly effective work. A number of cities, in particular, have become hotbeds of innovation, in no small part because of the fiscal strains they face.

With Washington mired in gridlock, local governments are being left “to grapple with super-sized economic, social, and environmental challenges,” Bruce Katz of the Brookings Institution has asserted. The good news: They’re responding “with pragmatism, energy, and ambition.” In fact, from our perch at the Drucker Institute — as we guide municipal leaders through the “Drucker Playbook for the Public Sector,” a training program distributed in partnership with the National League of Cities — we see local agencies performing particularly well in three areas.

The first is exemplified by South Bend, Ind., which is spurring rank-and-file workers to view themselves as innovators — a tough thing for many corporations to get right. As we’ve observed, it’s a mindset that starts at the top.

In the case of South Bend, that means Mayor Pete Buttigieg, a former Rhodes scholar and McKinsey consultant, who has been known to challenge city workers to tackle problems so thorny that they can only be solved with new kinds of thinking. In 2013, for instance, Buttigieg called for staffers in just 1,000 days to address, through rehabilitation or demolition, 1,000 vacant and abandoned properties blighting the city. They are now on pace to beat his ambitious timetable.

“Mayor Pete frequently says, ‘If we’ve never done it that way before, we’re on the right track,’” notes Scott Ford, the executive director of the city’s Department of Community Investment, which is responsible for economic development in South Bend. In turn, Ford has issued a mandate to his direct reports: He expects them to carve out real time to work on policy innovation, and not just concentrate on programmatic execution.

The results are tangible: Largely through the efforts of a single front-line employee and two middle managers working in Ford’s shop, South Bend last year streamlined and automated its tax-abatement petition process. Specifically, these staffers figured out how to slash the application from 22 pages to 4. What’s more, they made it so that those seeking tax relief now fill out a common online application, which allows the city to track their progress, monitor delays, coach them through any hiccups, and help them hit all deadlines.

It’s hardly an isolated example. In the past year, Ford’s people have also come up with fresh ideas to simplify accounting approvals, better track low-income housing tax credits, and speed up the transfer of funds.

That a place like South Bend has been able to cultivate this kind of bottom-up innovation makes sense. Although government workers are widely considered apathetic, research shows that many of them “enter public service because they are already committed to the mission of government” and are eager to make “a positive difference in the lives of the citizens they serve,” as Robert Lavigna, the author of Engaging Government Employees, commented recently. For companies trying to convey a strong sense of purpose to their workers, there is much to be learned here.

A second area in which cities are operating at a world-class level is in gathering and analyzing data to enhance performance. Take Louisville, Ky., which is pushing hard to constantly answer some key questions: What is city government doing? How well are we doing it? And how can we do it better?

Backed by the city’s LouieStat database, officials in 2014 were able to, among other things, reduce hospital turnaround times by an average of nearly 10 minutes for Emergency Medical Services personnel, making them available for more runs; slash the portion of restaurants, public pools, and other facilities in Louisville not receiving health inspections on a timely basis from 10.5% to less than 0.1%; and cut repair time for the city’s vehicle fleet to just 19 days from 77.

It’s not merely theory that government has much to teach business about using information effectively. Humana, the health insurer, helped Louisville get its performance-improvement team rolling a couple of years ago by offering pro bono support and teaching city staff about Lean and other management techniques. Humana executives still provide mentoring and coaching. But now, Louisville is also sharing with the company its own knowledge on a topic in which it has developed considerable expertise: linking performance management with innovation.

In addition, the city has become active in the Association of Internal Management Consultants, exchanging best practices with managers from Coca-Cola, Bell South, Turner Broadcasting, and other corporations. “It’s really a dialogue back and forth,” says Theresa Reno-Weber, Louisville’s chief of performance and technology. “We’re learning from one another.”

The third area in which cities are excelling is in arming residents with technology to improve government services. Among those leading the way is Boston, whose Citizens Connect mobile app allows people to report on potholes, graffiti, and other neighborhood nuisances. Now, the city is trying to take the technology even further by having it foster real civic engagement.

We are certainly not saying that all cities are well managed. Mindless bureaucrats abound in too many locations. Episodes of waste, fraud, and abuse are easy to cite, as well. When it comes to government, “it’s very easy for us—people associated with corporate entities or people doing research on the corporate world—to be somewhat condescending, dismissive,” Yvez Doz, an INSEAD professor, remarked last year.

But to see only the warts is to miss a huge opportunity. The best-run government operations have much to teach business, just as the best-run businesses have much to teach government. As Peter Drucker knew, the same holds true for nonprofits. Clearly, no sector has a monopoly on wisdom.

[image error]

How to Break into Your CEO’s Inner Circle

There is a widely held belief that strategic decisions are made collectively by an organization’s executive team, the senior executives who report directly to the CEO. In many organizations, though, nothing could be further from the truth. Decision-making power resides with a much smaller group, who form what you might call the CEO’s inner cabinet. Members of this elite club wield a disproportionate amount of influence, which is why most executives want to join.

But how does one become a member of the CEO’s inner cabinet? What traits must one possess? Ask CEOs and many hesitate to even admit they have an inner cabinet lest it demotivate those who aren’t members or, worse, have them clamoring to be admitted. Other CEOs simply respond that their closest confidants need to be “team players,” which is vague and even misleading.

To help executives get a better understanding of what they need to do in order to become a member of the CEO’s top team, I asked the CEOs I have worked with to name the “best” executives they’ve led — by definition, therefore, members of their inner cabinet — and to describe what set them apart. Five traits came up time and again.

Insiders make their numbers

This is often the first thing CEOs mentioned. It is shorthand for “they achieve the objectives I set for them” and the dogged determination they demonstrate in doing so.

But do the very best always make their numbers? No, the CEOs admitted, but they don’t waste time making excuses when they don’t. In a word, they feel accountable. This trait was wonderfully illustrated by a senior vice president in a telecoms company who recounted how a regulatory ruling had just wiped several millions dollars from his bottom line. From the conversation that ensued it was clear that pleading with his CEO to readjust his year-end earnings target wasn’t an option. His only thought was how to make up the shortfall.

The dogged determination that the best executives exhibit when trying to make their numbers sometimes leads them to jostle with peers, something the CEOs I spoke to found quite acceptable, despite their often professed preference for “team players”. In fact, the last thing a CEO wants is for an executive to surrender resources and capital to a colleague in the interest of the team. That decision is not for executives to take — it is the CEO’s. In such circumstances, the CEO feels best served by executives who fight hard to make the case that their units deserve the available capital and resources.

Insiders don’t spring surprises

If bad news is about to hit, CEOs want to hear it directly from the executive responsible, and certainly not from a board member or the media. This places executives between a rock and a hard place. Tell the CEO about the bad news before it materializes and you run the risk of appearing incompetent or unsure of yourself — not traits CEO admire. Just as bad, you invite the CEO to poke his or her nose in your business.

Seasoned executives learn when to reach out to their CEOs and when to hold back, which inevitably means they aren’t always totally transparent. CEOs tolerate this because they were once in the same shoes and in any event they know that they have little choice, given that they can’t know everything that’s going on in the company.

That said, not being totally transparent is one thing, but being evasive is quite another. Though CEOs may tolerate that executives keep information from them at times, they expect straightforward answers when they ask straightforward questions. One CEO told me about a direct report who had an impeccable track record but whose monthly reporting was never clear. This led the CEO to ask questions and demand more clarity. The situation never improved and, despite good results, the executive was dismissed for fear that, one day, his lack of clarity might hide a nasty surprise.

Insiders are loyal to the boss

If CEOs are the most powerful people in their organization, they still feel vulnerable — with good reason since they know that, at any given time, one or more of their direct reports wants their job. It’s easy to understand why loyalty is another important trait for CEOs.

It’s a particularly sensitive point for CEOs in an era in which their effectiveness is being scrutinized more than ever by corporate boards. For this reason, executives who wish to appear loyal should be wary of cozying up to board members. As one CEO put it: “Too much exposure to the board leads to radiation!” CEOs are also wary of executives who form coalitions with peers. One CEO told me she was considering firing her CFO because he consistently ran his monthly financial report by the Operations VP before showing it to her and, as she realized, was letting the Operations VP unduly influence when revenues and expenses were recognized.

Insiders tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty

This matters for two reasons. First, a CEO’s job involves striking a balance between a wide set of seemingly contradictory interests. They must plan for the long-term while minding the short-term, grow the top line yet ensure the bottom line stays healthy, and minimize risks while making risky bets. CEOs want executives who tolerate the ambiguity involved in this juggling act. As one put it: “When I hear an executive complain that I’m sending contradictory messages when I say we need to cut costs and spend to innovate, that tells me something about their capacity to move to the next level.”

Second, CEOs operating in uncertain environments need to have a lot of “what if” discussions with their executives. Those with a low tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty invariably react by emphasizing the negative consequences of a given scenario, especially on their unit. It is at times like these that executives who want to enter the CEO’s inner cabinet must be able to put their organizational leadership hat on and leave their unit leadership hat at the door. In my experience, a low intolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty derails more executive careers than a lack of technical competence.

Insiders are good-humored

Many CEOs mentioned “a good mood” as a trait they saw in their very best executives. I sought clarification and discovered that by “a good mood” they did not mean they wanted “Yes” men or women. CEOs want to be challenged but smart executives pick their battles and don’t constantly raise objections. And they are often, although not always, charming enough to present the unpleasant in a pleasant manner.

A good mood also seemed to be code for not bringing disputes with peers to the CEO for resolution. Top executives resolve them on their own. Some are even adept at helping to resolve disputes between their colleagues so they don’t find their way to the CEO’s office. Thus, a good mood appears in some cases to be synonymous with strong mediation skills.

The five traits that emerged from my CEO interviews were found in both men and women, and in executives with P&L responsibilities and those with functional responsibilities. They are not the traits typically found in leadership textbooks, but then again, the majority of leadership textbooks aren’t written by CEOs. They might not even be the five traits the CEO in your own organization most covets. But unless and until your CEO signals what she actually wants from you, getting better at these behaviors won’t be a bad start to winning a place at the top table.

[image error]

Why Online Retailers Are Starting to Care About Your Feelings

When I was growing up in suburban Cleveland, the mall was everything. It was where I hung out with friends, earned my first paycheck, and exercised my newfound independence. Now that mall is practically empty. Storefronts are vacant. You can hear the footsteps of the few shoppers echo down the hall.

We all know that shopping is not just about buying stuff, and that there are emotional and social reasons that drive us to choose certain shopping experiences over others. In the rush to get online, retailers focused on building lower-cost digital equivalents of their stores that left behind many of the human connections we once enjoyed. But in the latest wave of digital business models, e-tailers are seeking to satisfy not just functional needs but also those complex emotional and social “jobs to be done” that once made malls destinations.

This approach is typified by San Francisco-based Weddington Way, a start-up that aims to harness the group experience of shopping for bridesmaid dresses—keeping it social even when members of the wedding party live in different cities. By creating their own private virtual showrooms, brides and bridesmaids can discover, recommend, and vote on dresses and colors in a collaborative online space staffed by personal stylists available by chat session. With 25,000 dresses sold in just the first half of 2014, the company is approaching the $10 million revenue mark, a sum that includes fees from both purchasing and renting bridesmaid dresses (recognizing that lots of bridesmaids actually can’t wear it again, no matter what the bride says).

Insight Center

Making Money with Digital Business Models

Sponsored by Accenture

What successful companies are doing right

Other e-tailers are focusing on building experiences that eliminate the emotional angst and uncertainty of online purchases. In doing so, they are turning the “showrooming” phenomenon (browsing in-store then buying online) on its head. Zappos, Warby Parker, and others have proved that you can still turn a profit if you send consumers many choices to try on by mail and let then just keep the one item they like. But companies like Bonobos.com are now going a step further by integrating bricks-and-mortar services with the Web and mobile apps.

The men’s clothing site started online in 2007 but took off more recently when it began adding physical locations. The New York-based company has opened “Guideshops” in 10 cities that help alleviate the worry men have when buying clothing online. Will they look dorky? Does that shirt go with that tie? Do the clothes fit properly? What is the proper fit, anyway? Men can make an appointment to visit the showroom, which like a traditional bridal showroom, has samples of goods but doesn’t stock everything in every size. At the showroom, customers can meet with a real-life Guide, a personal shopper who can help them select, try on, and order clothes to be delivered in the proper size to their homes. Not having to keep all its goods in stock in the store means the physical spaces can be much smaller than a typical retailer’s, significantly lowering their cost and letting Bonobos combine the advantages of large on-line selection with in-person service. On the strength of this model, Bonobos is reportedly approaching $100 million in annual revenues and is partnering with Nordstrom to sell its custom clothing line in 200-plus stores.

Other retail start-ups are developing business models that monetize social connections in new ways. For instance, Luvocracy encourages shoppers to recommend clothing and fashion items from anywhere else on the web. Friends can add “luvs” to products which increases the “trust” rating of the recommender. When someone buys a product that you’ve recommended, you earn a 2% reward. If you attract enough followers who buy those products, you can become a “tastemaker” and earn 10% commissions. This model of turning on-line shoppers into salespeople was so attractive that Walmart Labs snapped up the company in an acquisition this summer. While Walmart’s plans for the site are unclear, I’d bet that the retail giant will end up integrating many of its lessons into the overall Walmart digital experience.

Interest from major retailers is one clear sign that these more-sophisticated digital business models are establishing a new basis of competition in the market. No longer can retailers, offline or online, be successful just by being cheaper, more convenient, or offering a wider selection. As competition intensifies, these functional advantages will become table stakes. With carefully designed experiences that address emotional and social jobs, newer entrants are setting a higher bar for the more-established retail brands and business models.

[image error]

Why English, Not Mandarin, Is the Language of Innovation

Last October, Mark Zuckerberg shocked the world when he addressed a group of students at Tsinghua University in Beijing completely in Mandarin. Media praised or lampooned his elementary grasp; some even called it mind-blowing.

The story reignited a decades-old debate: Will Mandarin overtake English as the global language?

For Zuckerberg, it’s certainly proven effective – prompting China’s Minister of Cyberspace Administration Liu Wei to visit for a meeting at Zuckerberg’s own desk in December.

César Hidalgo and his team at MIT Media Lab, however, would still argue for the preeminence of English. They published a study in late December that identifies English as the most influential language in the world. Their data are illustrated in “The Global Language Network,” an interactive model they produced showing English to be the largest hub of information. Hidalgo says the model suggests not a bias toward English itself, but that English, through its relevance as the dominant language of the internet, is able to connect people across languages.

Still, it’s true that China’s economy today is undergoing rapid change: the middle class is expanding, purchasing power is increasing, and with loosening regulation, China is becoming a fertile new market for global companies. In addition, native Chinese tech companies such as Alibaba, Weibo, and Momo are having some of the most successful IPOs in U.S. history.

But even despite China’s impressive growth, it seems clear that English – not Mandarin – is and will remain the language of innovation. Why?

From how we code to how we type, much of the world’s biggest advancements were developed with the English-speaking market in mind. Standard QWERTY keyboards are designed for the Roman alphabet and can’t accommodate the 2,000+ Chinese characters considered necessary to achieve even basic literacy in Mandarin.

The popularity of the QWERTY keyboard means programming languages typically use the Roman alphabet as well. In fact, the top 10 programming languages in the world are English-based. Two of these, Python and Ruby, were actually created by native Dutch- and Japanese-speakers, respectively, which shows that nonnative English speakers adapt to learn and use English when trying to accomplish broad goals.

English’s importance in the early development of modern technology has cemented its global importance today. Fifty-six percent of all online content in the world is in English. Accessing this content and drawing revenue from it requires English skills, which businesses and consumers alike are eager to acquire.

According to the annual EF English Proficiency Index for companies, English is a top priority for the world’s fastest-growing markets because it’s the common language that diverse and international companies use to communicate. The necessity of speaking English in the workplace has therefore increased the number of individuals looking to showcase their English skills for potential employers.

Global estimates figure more than 1.5 billion people around the world are trying to learn English. The sheer diversity of this population – culturally, economically, geographically – has heightened the demand for English training tools that can be accessed easily and inexpensively. As a result, we are seeing a surge in demand for standardized English proficiency exams such as the TOEFL, IELTS, and now the EFSET.

It’s important to note that this doesn’t mean English will replace local languages. Companies still need to serve markets locally; with globalization comes an increased need for localization.

The challenge for companies is to create cohesion between culturally distinct workforces. English, often considered a relatively neutral language, acts as a bridge that connects employees across countries and cultures, providing a pathway for innovation.

And the best tool of innovation? Collaboration. Companies whose employees can work together in a common language are more effective, efficient, and better able to work together.

As a result, companies around the world are choosing English as their official corporate language. European aircraft manufacturer Airbus is one example, as is Japanese e-commerce firm Rakuten, French automotive company Renault, and Korean electronics firm Samsung. Smaller companies looking to expand into the global economy are also investing in English. These companies are even offering language training tools for their employees.

In a survey conducted by The Economist Intelligence Unit, 90% of executives at companies around the world report that if cross-border communication improved at their company, then profit, revenue, and market share would increase significantly. This, in turn, would set them up for better expansion opportunities and fewer lost sales opportunities. Nearly half of the survey respondents acknowledge that basic misunderstandings stood in the way of major international business deals.

What does this all mean? English facilitates the innovation economy because it allows individuals and companies around the world to communicate, and therefore collaborate toward a common vision or goal. Imagine if Yahoo’s founder, Jerry Yang, never learned more than “shoe.” Or if Mike Krieger, Sao Paulo native and founder of Instagram, never learned English to attend college in the U.S.? Going back a few years, a man named Andy Grove, a native of Hungary, escaped WWII and went on to found Intel. What if language barriers stood in the way of these technologies?

When asked about how he sees Facebook developing in the next 10 years, Zuckerberg has said his first priority is to connect the entire world.

I’m with him. And having common ways to communicate and collaborate is a good start.

[image error]

January 9, 2015

The Myth of the Tech Whiz Who Quits College to Start a Company

There are three common myths about tech founders: they are extremely young, they are technically trained, and they’ve often graduated from a prominent local university. The logic then follows that to accelerate the growth of a local tech sector, cities need to actively cultivate people who fit this profile and encourage them to start a business. But on all three counts, the data tell a different story.

Two of the most successful tech entrepreneurs in history—Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg—follow this model. Both were college dropouts who studied computer science by day, programmed by night, and built large public companies without ever having worked at one. Anecdotes from popular media have only added to the cult of youth. Last year, articles in The New Republic and The New York Times explored the role young entrepreneurs have played in shaping Silicon Valley. The verdict in both follows a familiar line: for better or worse, successful tech sectors are products of young entrepreneurs, who disrupt whole industries without ever having worked in them.

These founders, in turn, are invariably portrayed technical experts. HBO’s Silicon Valley is emblematic of this stereotype: its protagonists are nerds. What they lack in business and social skills, they make up for in technical brilliance. The show is satire, but not pure hyperbole, either. Science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education is now at the center of entrepreneurship policy, and cultivating technical talent has become an important goal of the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP).

Where better to get that technical education than at a great local university? Stanford is the classic example, with hundreds of future Silicon Valley entrepreneurs passing through its Palo Alto campus. A university of this caliber not only creates great talent, the theory goes, but also helps a region to retain it. It makes sense, then, to assume that without a world-class university nearby, a city’s tech sector cannot thrive.

Over the last year, we at Endeavor Insight began studying the New York City tech sector, one of the largest in the world, to understand just how closely these myths align with reality. We started with publicly available data from Crunchbase, AngelList, and LinkedIn, and layered on top of it interviews with nearly 700 local tech founders. We found that none of these three stereotypes hold up.

We looked at the university start year for over 1,600 New York City tech founders, and found that college dropouts are the exception, not the rule. While the bulk of founders were in their twenties, the average founder in our analysis was 31 years old at company founding, and a full 25% were older than 35 when their companies got their start.

We also found that youth does not predict success. We took recent research by the Harvard Business Review a step further, by comparing founders’ age to traditional measures of success—investment amount, employee count, exit value—and found no relationship between age and company success.

The most successful entrepreneurs are not like Mark Zuckerberg or Bill Gates, and instead tend to be mid-career specialists with substantial industry experience. Take Alexandra Wilkis Wilson. She earned an MBA and worked for several years at retailers like Bulgari and Louis Vuitton before founding Gilt Groupe, a leading e-commerce business that has raised over $200 million. The same is true for Neil Blumenthal, who spent five years as Director of VisionSpring, honing his industry knowledge before founding online eyeglass company Warby Parker.

Tech founders are also much less technical than conventional wisdom leads us to believe. We divided New York City tech founders’ college majors into two categories: STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) and non-STEM, and found that just 35% studied STEM fields, while 65% majored in something else. In fact, these founders were more likely to study political science than electrical engineering or math.

When computer chips were made by hand, tech entrepreneurship was the domain of engineers and computer scientists. But today the barriers to starting a tech company have never been lower. With just a few clicks, a would-be entrepreneur can build a website, acquire new customers, and begin making sales. Scientists will continue to develop new technologies, but most entrepreneurs will succeed by applying existing solutions to new markets, creating a thriving local tech sector in the process.

Local universities certainly develop new research and talent, but their role in attracting and retaining entrepreneurial talent is less certain. In truth, talent flows to wherever opportunity is greatest. New York City is no exception, with over 90% graduating from college outside of the city. (The University of Pennsylvania, 100 miles to the south, is the school with the most alumni in our sample of New York City tech founders.)

Despite its world-class universities, New York City’s tech scene succeeds because people want to live there, not because they studied there. The average future entrepreneur initially comes to the city to work for one of its existing companies, taking the plunge to found a company almost a decade after graduating. Ultimately, it is not the cities that educate entrepreneurs, but rather the ones that attract and retain them that are building top-performing tech sectors.

Our research shows that entrepreneurs don’t fit the stereotypes. Policymakers looking to further local tech sectors need to base their decisions on numbers, not anecdotes. In reality, the entrepreneurs they are seeking to support are older, less technically trained, and more likely to have attended college elsewhere. Whatever their age, experience, or background, the best policies use data to help local entrepreneurs scale their businesses and reinvest as mentors, angel investors, and serial entrepreneurs in the city where they got their start.

[image error]

Advice for Dealing with a Long-Winded Leader

It can be tricky to tell people that they talk too much. And in cases where the offender is someone more powerful, like a senior executive or important customer, it can be downright risky. As a result, many “victims” have been suffering in silence for years in meetings that never end or conversations that drain the life out of them. As the saying goes, a rich man’s jokes are always funny.

How do you put an end to this agony? There’s no instant fix, but in addition to understanding why some people go on, and on, and on… there is a strategic approach you can use to spare yourself and everyone around you. While it shouldn’t be used all the time, it can help you build stronger relationships by moving from one-sided monologues to conversations.

First, more on why leaders can be long-winded. Executives sometimes find it hard to stop monopolizing a discussion because delivering a monologue feels so good. As a study by Harvard University researchers revealed, talking so much triggers a sensation of reward similar to that of sex, money, or food. It’s a power kick for big talkers to grab the mic — and hard for listeners to wrestle it from them once they’ve fallen in love with the sound of their own voice.

There are other reasons successful professionals tend to ramble. Sometimes they suffer from performance anxiety. They feel they have to put on a show. Or they may underestimate how busy and attention-starved their listeners are. The average attention span, they may not be aware, is now under 10 seconds.

So what to do? Here are some ways to counteract overtalking — without getting fired or losing a big account.

Diagnose the problem. Many senior leaders are long-winded in some situations and not others. Does your boss tend to deliver an Oscar acceptance speech only when big clients come to the office and meet you in the conference room? Will your biggest client complain for hours about his divorce case over lunch, but not if he stops by the office? Are management monologues more likely to occur when there’s no formal agenda, if you’re on a phone call with no time constraints, or when no one asks any questions?

Take note of when your culprit tends to dominate the conversation so you can change the setting or circumstances. All of these clues can indicate what the core problem is — and help you devise a plan of attack.

Identify your approach. There are a few different methods to help someone be more succinct. Before you choose one, consider the payoff to the offender. Perhaps he or she will benefit from a more productive team, greater collaboration, faster results, less frustration, fewer misunderstandings, or a savings of time. Once you’ve honed in on a benefit, consider how direct you should be. If your target is not good at picking up cues that listeners are getting bored, you may need to be direct. Other excessive talkers may require a more diplomatic approach.

A more direct approach works well when you have a strong enough relationship with the culprit to be brutally honest. Come prepared with a point — and a payoff — and be brief.

When Mitch Golub, the president of Cars.com, realized his team couldn’t stand working for a top client because meetings and calls dragged on so long, he decided the situation was so critical he had to raise the topic of brevity to maintain the partnership. He took the straightforward approach and said, “You’re an important client, but we are having trouble getting people on our team to work with you.” Golub shared a number of examples of how the client’s lack of focus was preventing his employees from delivering results. Afterward, the client thanked him — and did cut to the chase more. Golub is glad he took the risk. “Today, our relationship has never been better,” he says.

Regardless of whether you feel you can be brutally honest, you can explain and model the many benefits executives gain when they embrace brevity — a new business essential in an attention-starved economy.

Brian Ames, vice president, employee communications at The Boeing Co., recommends connecting brevity to a key business issue like credibility or leadership development and waging “a running battle against jargon.” Frame the issue as one that can help transform the corporate culture and improve the vendor relationship. Brevity is, in fact, a shift of thinking and acting for leaders that delivers tangible results immediately. A key measure of your success at this, says Ames, “is whether the end user of the message feels respected or not.”

You can also remind your listener that it is challenging to communicate in an information-driven economy: People are exhausted. They check their smartphones more than 100 times a day, and get interrupted six to seven times an hour. They’re at the saturation point and can’t take in much more information. The more we talk, the less they hear.

Everyone needs to adapt when the issue is framed as a significant social change. Brevity is a prime area of improvement for senior executives and people in a position of authority.

Reinforce brevity. Many leaders get better at being clear and concise once they work on it, then fall back into bad habits.

To keep them from losing ground, use some practical techniques to set limits or expectations. A junior employee might say to a boss, “I know your time is valuable. Let’s keep this to five minutes.” Another approach that works: “I’d like talk with you about the Jones account. I’ve prepared a three-bullet-point agenda. Could we discuss each of these items for five minutes?” On a conference call with a client, you might mention early, “I’ve got a hard stop at noon. Is there anything you’d like to tackle right away?”

I’d also suggest embracing brevity in your meetings by using tighter agendas and shortening or eliminating PowerPoint presentations to foster better, more concise conversations. In other words, personally commit to being brief as well to set an example. It can help you spread the challenge of being better by being brief.

[image error]

Stop Enabling Gossip on Your Team

Every Friday, the CEO of a prominent tech company (I’ll call him Ken), gathers his troops in the courtyard of their campus for critical updates. The level of candor in these meetings is impressive but the most fascinating part — and what makes this company so unique, is the Q&A that follows. It’s a no-holds-barred exchange that would take the breath away of most corporate managers. The CEO implores people to ask tough questions. On a recent Friday at 4:55pm with seconds left in the meeting Ken points to an employee with a hand raised. The employee says:

“Ken, when I got here I was told you wanted a culture of candor and respect. I have an email thread that included dozens of us here from one of our top managers that demonstrates he is a flaming jerk. He was abusive, condescending and threatening. So, I have three questions for you: 1) did you know this? 2) do you care? 3) what are you willing to do about it?”

Exchanges in the Q&A are breathtaking not because the sentiments are unusual but because in most organizations they are firewalled off in gossip where they can never get to those who can do something about them. I’m not suggesting that excoriating someone in front of thousands of co-workers is a preferred way of solving problems. It’s not. But I would argue that clumsy efforts that get problems in the open are almost always preferable to collusive gossip that disavows responsibility.

First, let’s talk about why gossip happens. People wouldn’t do it if it didn’t serve a purpose. In fact, gossip serves three: informational, emotional, and interpersonal.

It is a valued source of information for those who mistrust formal channels. “Word on the street is that the new test facility funding didn’t make the cut.” It’s also the most common way of gaining valued information about our most important social systems. “Don’t have Ted do your graphics unless you’re satisfied with clip art.”

It sometimes serves as an emotional release for anger or frustration. “Chet made us look like idiots in the project review today. I was so humiliated!”

It is used as an indirect way of surfacing or engaging in interpersonal conflicts. “I heard Brett slammed your capital requests—and mine—in the planning meeting. I see no reason to keep processing his claims with the same urgency.”

Gossip is an effective way of achieving these goals in an unhealthy social system. People engage in gossip when they lack trust or efficacy. We become consumers of gossip when we don’t trust formal channels — so we turn to trusted friends rather than doubtful leaders. We become purveyors of it when we feel we can’t raise sensitive issues more directly — so we natter with neighbors rather than confronting offenders.

The problem with gossip is that it reinforces the sickness that generates it. It’s pernicious because it’s based on a self-fulfilling prophecy. If I lack trust or efficacy I engage in gossip — which robs me of the opportunity to test my mistrust or inefficacy. The more I use it the more I reinforce my need for it.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Office Politics

Communication Book

Karen Dillon

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Over time gossip weakens the will. Like all palliatives, it provides relief from problems without actually solving them. Reliance on gossip can sap the strength it takes to participate in complex social life. Risk-free yakking about problems temporarily distracts us from our sense of responsibility to solve them. It also anesthetizes us from the painful uncertainty that inevitably accompanies mature interpersonal problem solving.

Leaders at the tech company discussed above see gossip not as a problem but as a symptom of a lack of trust and efficacy. They address the underlying problem in three ways:

Stop enabling. The best way to stop gossip is to stop enabling it. Gossipers are rewarded when others respond passively — by simply listening. To stop it, force it into the open. At the tech company, employees know that gossip comes with a risk — the risk that you will be called out. Recently some employees noticed a number of others had begun to use a third-party app, Secret, which allows people to share message anonymously, to complain about colleagues and policies. When they recognized their colleagues’ complaints, longer-tenured employees began calling out those who were whining rather than confronting responsibly. They even posted their names and contact information in the app to offer support for those who wanted to learn how to truly solve their problems.

Build trust in the alternatives. Leaders at the company also reduce the supply of gossip by decreasing demand. They proliferate options for raising problems. The all-hands meeting is just one example. The company also uses an internal social network platform to model candor and openness on a host of topics that would be terrifying at other places. For example, some employees grumbled when execs announced a recent multi-billion dollar acquisition. Monday-morning quarterbacking is common at all companies but at this company it was done with attributed comments in a discussion group – and Ken participated! One employee kicked it off with: “What’s up? We already have a business unit that does the same thing with even better margins?” The concern was addressed openly rather than metastasizing in gossip because there were credible channels for the discussion to take place.

Build skill. Gossip is a form of learned incompetence — an acquired skill that produces poor results. Overcoming it requires replacing that skill. The tech company starts re-scripting employees on day one. In a rigorous orientation employees are asked to describe things they hated about other places they worked. At the top of the list is always gossip and politics. Managers leading these discussions use this moment to offer alternative skills and strategies for surfacing emotionally and politically risky concerns—and to challenge employees to create the culture they want by using them.

When the employee finished her statement to Ken, other employees erupted in applause. She was rewarded because she was transparent. Every employee standing there that day got the message: “At this company we do things in the open.”

And CEO Ken followed suit: “First,” he said, “I did not know about the concern you described. Second, I care deeply. And third, I don’t know what to do, yet. I need information. Are you available now to talk?”

Gossip is not a problem; it’s a symptom. The symptom disappears when a critical mass of leaders stop enabling it, create trust in healthy communication channels, and invest in building employees’ skills to use them.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers

![techfounders[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1420983501i/13303742._SX540_.png)