Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1333

January 8, 2015

Corporate Empathy Is Not an Oxymoron

In a transparent world dominated by social media, corporations are feeling the need to become truly responsive to the needs of their customers and employees. The corporate world is an increasingly immediate, intimate, and interactive space. The call for companies to engage in authentic dialogue is becoming louder. And yet this desire to change is hampered by the fear of appearing weak and vulnerable, meaning that most businesses still suffer from an empathy deficit. As the CEO of a British bank confided at last year’s World Economic Forum, “We all know it’s important to be empathic, but how do I galvanize 48,000 people in my UK operations — most of whom think that empathy is for wimps?”

Enlightened companies are increasingly aware that delivering empathy for their customers, employees, and the public is a powerful tool for improving profits, but attempts to implement empathy programs are frequently hamstrung by the common misconception of it as “wishy-washy,” “touchy-feely,” and overtly feminine. So empathy is de-prioritized, and relegated to the status of just yet another HR initiative that looks good in the company newsletter. It is seen as a soft and frilly add-on rather than a core tool.

An additional problem facing CEOs is that many see empathy as an intangible quality, and as such hard to quantify. If you can’t measure empathy then it is very difficult to assess how much empathy your company is delivering, and where the greatest empathy deficits lie.

This is a misconception. Empathy can be measured, and your business’s empathy quotient can be assessed, allowing CEOs to pinpoint their companies’ strengths and weaknesses, and see how they rank alongside their competitors. Empathy should be embedded into the entire organization: There is nothing soft about it. It is a hard skill that should be required from the board-room to the shop floor. Corporations must demonstrate empathy across three channels: internally, to their own employees, externally, to their customers, and finally to the public via social media.

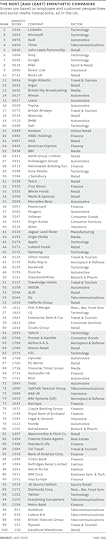

We define empathy by three components: customer, employee and social media. The combination of these, with equal weighting, across the three channels–internal (employees), external (customers), and social–gives us a company’s “empathy quotient.” We then applied our thinking to the 100 best-known companies in the UK, where we’re based.

Which, then, are the most empathic and least empathic household names? And what does this tell us about the way the corporate world is dealing with its empathy deficit?

While confirming many of our expectations, the results revealed a number of interesting surprises. The top places were not all taken up by trendy tech brands, and the bottom was not dominated by multinational banks. The sector that fared worse was the telecoms, with Vodafone and BT scoring particularly badly. Employee and customer satisfaction are the casualties of the race for short-term profits that is endemic in that sector. Their social media strategies tell one part of the story: they are over-reliant on unhelpful canned responses which merely shunt customers to more traditional forms of contact, such as call-centers.

The highest performing company was LinkedIn. It was striking that LinkedIn actually has a strong presence on the rival platform Twitter. One might expect them to force customers exclusively onto to their own channels of communication—which is the policy of both Twitter and Facebook. Instead, the company makes an effort to go where their customers are, even at the risk of being seen to endorse a rival product. This approach shows that LinkedIn empathizes with its customers’ interests and choices.

Other surprises included Twitter, which flails in a mediocre mid-table spot—with its primary empathy failure being its inability to engage with its own customers on its own platform. Few would have been surprised to see the airline Ryanair down at 99th. The only shock there was that the technology retailer, Carphone Warehouse, did even worse.

We expected the small and medium-sized companies to come out on top, guessing that larger companies would be the least empathic. But large companies were evenly distributed and well represented at both ends of the scale. There is absolutely no evidence that being big automatically makes you un-empathic. Empathy is most definitely not a problem of scale, but more an indication of management priorities.

Very few companies are good all-round empathizers. Even LinkedIn underperformed on our customer interaction score. The index highlights that each of the hundred companies had room for improvement. Two particular findings deserve emphasis: Customers are unforgiving of poor service and inauthentic communications (got that, telecoms?). And companies that see empathy as a single-dimension issue of employee relations will fail to realize the broader benefits of becoming more empathic across the other two channels.

Methodology

The Lady Geek “Empathy Quotient” is inspired by Simon Baron Cohen’s “Empathizer” and ‘”Systemizer” model. We built our model to measure levels of empathy in large consumer-facing companies with a significant presence in the UK. The Empathy Quotient combines three data streams to generate each individual company ranking. Each source summarizes one important aspect of empathy: customer, employee, and social media. All data sources are given the same weight when constructing the overall score and final quotient.

The employee and customer perspectives are sourced from nationally statistically representative samples in the UK and from publicly available data. The social media data is extracted from public communications made by the company. Our algorithm classifies empathic and unempathic interactions on Twitter.

Prior to combining these measures they are first standardized to address any inherent differences in the way that the data was collected and recorded. The standardized measures are combined and finally ranked.

Our data partners include Glassdoor and Survation. All surveys were conducted online. The sample size was over 1,000 nationally representative customers, each employee review was based on at least 25 employee reviews. The social media data was extracted from 10,000 tweets over a 2 week period.

This index can be really useful in locating the strengths and weaknesses of individual companies and using them as a basis of comparison. The management at Mercedes, for example, should be asking itself why it comes in at a relatively modest 35th, while Audi’s results put it in third place, and consider an expansion of its investment in social media which is where Mercedes is underperforming.

The good news is that the empathy deficit can be reduced. Empathy can be learned and companies can improve. With prioritization and commitment, companies can measure where they are and chart a path to becoming more empathic. Enlightened leadership can create a more empathic culture. Rene Schuster, former CEO of Telefonica Germany, puts it this way: “Empathy is not a soft nurturing value but a hard commercial tool that every business needs as part of their DNA. Our aim is to make every interaction our customers have with us an individual one.” Schuster implemented a Germany-wide empathy training program that led to an increase in customer satisfaction of 6% within 6 weeks. Even companies within the worst performing sector in our Index can show rapid improvements given focused management attention.

Empathy pays, and it pays best when it comes from the top.

[image error]

January 7, 2015

Knowing When to Fire Someone

George is the most talented, productive executive Roy ever had to fire.

George had pulled off a string of celebrated victories and won a reputation as a strong performer. Having been hired to lead his hospital’s compliance program as regulations grew increasingly complex, he had put the policies and procedures into order, achieving a goal that had eluded the organization for years.

Roy was grateful that this burden had been lifted off his shoulders. In fact, he was so smitten that he didn’t notice what else was going on — that George (and for the record, this is a composite case) had alienated colleagues and failed to create the sense of urgency needed to persuade employees to complete the required training. George’s excellent work was of little value if it wasn’t fully implemented throughout the organization.

As other team members started to complain, Roy made repeated attempts to coach George to improve his interpersonal and communication skills, but George rebuffed him.

It took Roy a while to see the corrosive impact of George’s more subtle deficiencies and to make up his mind about what to do. Roy was well aware of the cost and disruption of a termination. He spent so long weighing the issues that he nearly caused irreparable damage to his team’s collegiality, reputation, and performance.

Roy eventually realized that keeping difficult people around can undermine what should be a leader’s number one objective: maintaining a positive and productive work environment. If Roy had used a tool such as a simple worksheet to help him evaluate the costs and benefits of keeping George on board, he might have determined that George’s impact on the team’s productivity and esprit de corps outweighed the value of his contribution much sooner, to everyone’s benefit.

In The No Asshole Rule, Robert Sutton makes a case for banning jerks from the workplace because of the devastation they can inflict on coworkers’ emotional well-being and work quality. But skillful individuals don’t have to be full-blown tyrants to wear out their welcome.

Working with people who refuse to accept criticism is one of the thorniest management issues a leader can encounter. What may start out as a modest deficiency — one that could be easily addressed with performance coaching — can shift to an insurmountable management challenge when the employee resists feedback. The original performance issue soon becomes compounded by dysfunction in the manager-employee relationship, making the situation much more difficult to assess.

Because terminating someone is such an important and complicated strategic decision, it helps to have an objective way to measure the impact of a difficult employee, including a dispassionate evaluation of the disruption caused by turnover. Using the worksheet to quantify the factors in a termination decision can help you evaluate the costs and benefits of individuals’ performance, their impact on team dynamics, and bottom-line results. You can list such factors as the employee’s likelihood of improvement, the drain on your energy, and the cost of replacement. The tipping point comes when the cost of keeping an employee is greater than the disruption of letting him or her go. Such a tool could have helped Roy make the decision about George a lot sooner.

Or consider Jeff, a human-resources executive in a large global company (another real, but disguised, case): One of his managers, Karen, had a very strong skill set and brought passion and deeply relevant experience to her role. She performed well initially, but as the demands of her job grew, she lost focus and had increasing difficulty completing complex projects.

Unable to manage her time well, Karen became a demotivating influence on her team members, failing to keep them informed. For close to a year, Jeff tried to help Karen get back on track. Despite being an HR expert and well acquainted with best practices in delivering feedback, he was unable to overcome her defenses and motivate her to work on her deficits. Worse, these conversations generally left her moody and unpleasant to be around.

Karen wasn’t a jerk at all. She was well-liked, but she was so defensive when getting feedback that she couldn’t work on addressing the problems. Over time, Jeff found himself doing more and more of Karen’s job himself. He continued to compensate for her gaps for way too long because the cost and disruption of making a change were so great.

However, Karen’s teammates grew resentful as her deficiencies began to affect the group’s ability to deliver. Jeff knew it was his obligation to minimize obstacles in the way of the team’s performance, particularly as the team was expected to produce more results with fewer resources. Equally important, Jeff felt drained by confronting Karen’s crankiness, especially when his effort had little chance of producing positive results.

Clearly, doing his subordinates’ work was not the best use of Jeff’s time, and facing Karen’s moods was not the best use of his energy.

So in spite of her skills, experience, and institutional knowledge, and notwithstanding the disruption that a vacancy would cause, Jeff fired Karen. Eventually, Jeff’s decision was fully validated by the significant positive impact of Karen’s successor. Jeff’s only regret was that he had squandered so much time avoiding making the decision.

Leaders are responsible for managing the resources under their control. In most cases, the single greatest resource they manage is people, with compensation and benefits consuming as much as 80% of operating budgets. To sustain energy and engagement, and to retain the best talent, leaders must endeavor to make work life as manageable and as palatable as possible for themselves and their teams. Coming to grips with the need to fire a colleague, particularly when you’ve invested so much of your own effort to remediate his or her weaknesses, is one of the toughest management decisions you’ll ever have to make.

[image error]

The Type of Innovation That Builds Nations

Innovation drives economic growth.

This logic has risen to dominate the discourse in development circles, with government leaders, policy influencers, and development-minded business leaders fully embracing innovation as a panacea for unemployment and economic underperformance. Looking back on 2014, it is not difficult to see this globalization of the innovation mindset at work. India’s Narendra Modi recently called for a revival in Indian manufacturing and greater innovation to stimulate growth. Nigerian businessman Tony Elumelu recently launched a $100M Pan-African entrepreneurship grant program to unlock Africa’s economic potential. Start-up accelerators are almost as likely to be found in emerging nations as in Silicon Valley. Meanwhile, NGOs are increasingly emphasizing the role of innovation in their work.

But does greater innovation equal sustained macroeconomic growth and prosperity, all the time or even most of the time?

This question requires urgent clarification and may well be the difference between the developing nations that replicate the blistering success of China and the East Asian tigers, and those that crumble under the weight of their demographic booms.

There is reason to believe that while innovation can be pivotal to macroeconomic prosperity, not all kinds of innovation are created equal. But correlating innovation in itself with macroeconomic growth is misleading, as my co-authors and I discuss at length in a recent piece in Foreign Affairs. To understand how innovation truly interacts with prosperity, we should first distinguish between different kinds of investments in innovation. In simple terms, there are three types: sustaining, efficiency, and market-creating investments (see more in the HBR article “The Capitalist’s Dilemma”).

Of these, sustaining innovations (which replace old products with new and better ones) and efficiency innovations (which allow companies to make and sell established products for less) help companies serve their existing customers better, but do not address the needs of the majority of the population.

Market-creating innovations, conversely, are primarily focused at making products and services accessible to non-consumers or those who are under-served. For example, India’s Narayana Health and Kenya’s M-PESA transformed how healthcare and financial services were made accessible to non-consumers. Both introduced new business models that provided a “good-enough” solution for non-consumers, instead of going after customers that were already well-served. As they scaled their new business models, new value networks were created with net new jobs and economic uplift.

Market-creating innovations offer rapid growth and job creation, and by definition impact a larger swath of the population. Not only do they build new domestic value networks from scratch, but, when executed successfully, some market-creating innovations can be disruptive in foreign markets. The defensible cost models they develop and their knack for going after non-consumption often blindsides global competitors. This allows tiny economies to punch above their weight and build globally relevant companies.

Because companies and entrepreneurs are the vehicles for innovation, leaders in developing nations are right in reviewing how policy and other factors drive innovation. However, our research calls for a more intelligent approach towards the promotion of innovation. Rather than seeking innovation for its own sake, there needs to be a clear priority for the right kind of innovation.

Market-creating innovations are almost always harder to execute – in pursuing non-consumers, they are more often bound to the myriad infrastructural and social challenges that most developing nations face. They do not come together automatically; executing them consistently and successfully requires unparalleled collaboration between policymakers, investors, entrepreneurs and other stakeholders – but the rewards are more than worth it.

[image error]

When a Public Mistake Requires an Old-Fashioned Apology

Everyone makes mistakes. We make bad decisions and insensitive statements, we speak before we think, and we let our emotions get the best of us. But since we hold very senior executives to a higher standard, when they mess up, it often becomes a public spectacle.

Consider the case of AOL CEO Tim Armstrong. On August 9, 2013 — a time of disappointing quarterly results — he held an all-hands conference call with 1,000 Patch (AOL’s hyper-local news division) employees. During the meeting, which was called to announce layoffs and site closings, Armstrong publicly fired Patch’s creative director for apparently recording the meeting. This “brutal” firing created a firestorm of negative publicity both for AOL and for Armstrong. Several days later, Armstrong issued an apology to all AOL employees, in which he admitted that he had “acted too quickly … [and] learned a tremendous lesson … .”

Six months later, Armstrong was forced to apologize for another incident. In announcing his plan to delay retirement contributions, he mentioned the high cost of health care benefits and cited two individual cases in which the company paid $1 million dollars to care for “distressed babies.” Not only were his remarks callous, they also violated the privacy of the employees involved. After another round of disastrous publicity, Armstrong again issued a statement saying, “I made a mistake and I apologize for my comments.” He also reversed his decision to delay retirement contributions.

Of course, Armstrong is not the first, last, or only senior executive who has made troublesome public remarks. Tony Hayward, the former CEO of British Petroleum, famously complained that he “wanted his life back” in the midst of the 2010 oil spill. (He later apologized to the families of the workers who had died in the tragedy, as well as the thousands of people whose lives were totally disrupted.) Former Harvard President and Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers had to apologize in 2005 for his contention that “innate differences” between men and women accounted for the under-representation of women in the sciences. Senior advertising executive Justine Sacco was fired for posting an insensitive and racist tweet about AIDS in Africa. And more recently, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella apologized for suggesting that women should not speak up about pay inequities.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Office Politics

Communication Book

Karen Dillon

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

None of these executives intentionally tried to inflame their employees, their customers, or the public. But no workplace is perfect. Managers berate subordinates in meetings. Colleagues make snide remarks about each other. People send emails, texts, or tweets without giving sufficient consideration to how the messages will be received or whether they are sending them to the right people.

The question then becomes how to recover from one of these moments. A written and public apology is a good first step, particularly if you’ve offended thousands of people, but it’s not enough. The next step is to proactively seek out the few people who have been most affected and talk to them privately. Public apologies are impersonal. People who have been hurt need something more human. They want a genuine, direct apology.

Armstrong, for example, reached out to the AOL employees who were inappropriately singled out for the high cost of treating their newborn babies. As one of them later reported, “I really feel like he spoke to me … not in his public role as CEO … but in a heartfelt way as a father of three kids to a fellow parent … I appreciated it and I do forgive him.” Similarly, after one of my clients publicly humiliated a subordinate during a staff meeting, he sent an apology to all of his staff then also met one-on-one with the person involved.

The third step in the recovery process is to find out whether the poor behavior was a one-time slip, or part of a recurring pattern. Occasional mistakes can be forgiven, but if the same behavior occurs a number of times, an apology will ring hollow. If you really want to make amends and repair your reputation and authority after a public mistake, work with a coach, counselor, or trusted friend to assess problematic situations and figure out what triggers them.

Hopefully, AOL’s Armstrong has figured out if there were any underlying catalysts to his insensitive remarks. My client realized that his high performance standards caused him to behave irrationally when there was a shortfall in results — he’d take out his anger on whoever had responsibility for that area. Once he began to understand this pattern, he was better able to step back and calm down before discussing the issues. This prevented embarrassing moments and also created a better environment in which to solve problems.

The real key to moving forward is to accept that you’re not perfect, and that future mistakes are probably inevitable. Without this mindset, executives can easily convince themselves that they were actually “misunderstood” or there was poor communication — that it wasn’t really their fault. But without taking true accountability, executives won’t learn from their mistakes, and the next public gaffe isn’t far away. When executives do admit their flaws, they’re better able to fix their mistakes and reclaim respect.

[image error]

January 2, 2015

How and Why We Lie at Work

Although every society condemns lying, it is still a common feature of everyday life. Research suggests that Americans average almost two lies per day, though there is huge variability between people. In fact, the distribution of lies follows Pareto’s principle: 20% of people tell 80% of the lies, and 80% of people account for the remaining 20% of lies.

So how do you deal with a coworker you suspect of lying? It depends on the type of lie, and the type of liar, you’re dealing with.

Frequent liars have two salient characteristics. First, they are morally feeble, so they don’t see lying as unethical. Second, whereas most people lie when they are under pressure (e.g., anxious, afraid, or concerned), recurrent liars do it even when they are feeling good or in control of things – because they get a kick out of it. For these reasons, studies have found that frequent liars are more likely to admit to lying. If there’s nothing wrong with it, why hide it?

If you’re dealing with a frequent liar, he or she probably has strong social skills and a fair amount of brains. For example, neuropsychological evidence suggests that lying requires higher working memory capacity, which is strongly related to IQ. As Swift said, “he who tells a lie is not sensible how great a task he undertakes; for in order to uphold one lie he must invent twenty others.” Accordingly, effective lying also requires a vivid imagination, particularly when it comes to producing excuses and bending the truth; studies have indicated that creative people and original thinkers can be more dishonest. As Francesca Gino and Dan Ariely have noted in their research, “a creative personality and a creative mindset promote individuals’ ability to justify their behavior, which, in turn, leads to unethical behavior.”

In addition, effective liars tend to have higher levels of emotional intelligence, which lets them manipulate emotional signs in communication, monitor their audience’s reactions, and avoid something called non-verbal leakage – when our body language doesn’t match what we’re saying.

The key point with frequent liars is not to pinpoint whether they are telling the truth, but whether we can predict what they are likely to do. I may say “I enjoy working with you,” and I could be lying. However, so long as I keep pretending that I like working with you when we work together, then who cares about how I really feel about you? When lies are based on objective facts – “I graduated from Stanford” or “I will finish this project by Monday” – then they are self-defeating, because they damage the reputation of the liars when they are found out; so while it can be tempting to feel responsibility to punish the liar, recognize that simply exposing the lie may have the same effect.

Systematic liars are therefore as problematic as people who are systematically late: all you need to do is work out their typical patterns of behavior and plan around them. Unless you want them to stop lying to you, in which case you can gently expose their deceptions to show them you are not as stupid as they think.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Office Politics

Communication Book

Karen Dillon

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

An infrequent liar has a different psychological makeup. Many of their lies are the product of insecurity. These are lies motivated by fear, and they provide temporary psychological protection to the liar’s ego. For a trivial example, when asked whether you know someone important or have read a popular book, you may instinctively answer “yes” in order to avoid rejection. But this in turn actually increases your insecurity – what if you’re found out? – which will increase your probability of continuing to lie in the future.

Such insecurity-driven lies are often an attempt to gain status – exaggerating an achievement or claiming undue credit for a project. Status-enhancing lies are also often used to establish or maintain close bonds with others, for instance by making empty promises (offering help you can’t follow through on) or framing oneself as an insider rather than an outsider (saying bad things about Joe even if you don’t mean them, just to get along with Jane.)

The best way to deal with insecure liars is to make them feel accepted. Insecure liars are extremely self-critical, so it takes time and effort to compensate for their neurotic perfectionism and make them feel appreciated. Show them that you value them for who they are, rather than who they would like to be.

Whether you are dealing with a frequent liar or an insecure liar, there are a couple of important caveats. First, remember that while most of us perceive lying as a deliberate attempt to misrepresent the truth, as Nietzsche noted, “the most common lie is that which one lies to himself; lying to others is relatively an exception.” Both pathological liars and insecure liars are capable of self-deception. A great deal of psychological research suggests that people will generally act “dishonestly enough to profit, but honestly enough to delude themselves of their integrity.” Furthermore, it is quite plausible that the evolutionary basis of self-deception was to enhance our ability to deceive others, since it is much harder to persuade others of anything when we have not been able to persuade ourselves. To paraphrase George Orwell, “if you want to keep a secret you must also hide it from yourself.” And when someone is capable of distorting reality in their favor, they are not technically lying, just incapable of – or unwilling to – see the truth.

The key decision, in such situations, is whether we should help the individual see things in a different way. Truth can be taxing from a psychological point of view, when it inflicts a wound to the person’s ego. As Diderot pointed out: “We swallow greedily any lie that flatters us, but we sip only little by little at a truth we find bitter.” Before you accuse a colleague of lying, ask yourself whether he’s actually deliberately misleading others – or just sincere in a mistaken belief.

The second big caveat: not all lies are immoral. In fact, lies may be pro-social – “Mm, this is delicious!” or “Your new boyfriend seems nice,” or “That looks great on you.” Lies can even be ethical, such as when Nazis knock on the door and ask about the Jews hiding in the attic. This is why adults teach children to appreciate white lies and to develop a healthy degree of dishonesty, and why many people become “too honest” after they’ve had a couple of drinks. Indeed, successful interpersonal functioning often requires the ability to mask one’s inner feelings. Total honesty can take the form of amoral selfishness. Self-control is a moral muscle that not may inhibit not just dishonesty, but also honesty, when the goal is to behave in socially desirable or altruistic ways.

It is easy to get upset when someone lies to us, but there are many shades of dishonesty, and many motivations to lie. There are also many ways to react to a lie. Yes, you may feel insulted at being the target of deception, but reacting emotionally or confrontationally can backfire. A better approach is to politely demonstrate to the liar that they have failed to deceive you. Or just pretend to have fallen for it, which effectively means to deceive them back.

[image error]

For Leaders, Looking Healthy Matters More than Looking Smart

Every year around this time, people make resolutions to improve their lives and careers. The most common of these typically involve health-related goals such as quitting smoking or losing weight. The next most common might be career goals like finding a new job or getting a promotion. While we tend to separate out career goals from health/lifestyle goals in our minds, in reality there is a lot of overlap. If you’re looking to set some career goals, then you might think about getting healthier too. New evidence suggests that healthy-looking individuals are perceived as better leaders, even over intelligent-looking people.

The evidence comes from a study led by Brian Spisak at VU University of Amsterdam and published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. The study asked participants to judge leadership potential by looking at faces. Why examine our reactions to faces? Because they lead us to make snap judgments about other people. To quote the paper, “Qualities such as facial femininity can have a significant impact on who followers endorse as a leader in different situations because these visual signals can serve as a proxy for latent behavioral potential.” Facial femininity, for example, can signal tendencies to befriend or collaborate. Likewise, perceived age can be used to estimate wisdom or experience. Baby-facedness is often, for better or for worse, associated with trust.

In this particular study, the researchers created a collection of simulated faces based on a composite of three undergraduate volunteers (so that no one would recognize a particular person). Four faces were created, all of them clean-shaven white men who were not wearing glasses or jewelry. The researchers then manipulated those faces to make their “person” appear more or less healthy and more or less intelligent, based on previous research on assumptions based on facial features. The researchers then showed pairs of these faces to 148 participants recruited online. For each pair, participants were given one of four fictional company scenarios and asked to choose the new CEO of the company. The four scenarios outlined the CEO’s primary responsibility, either engaging in an aggressive competition strategy, renegotiating a key partnership agreement with another company, leading a new entry into an unknown market, or supervising the continued exploitation of non-renewable resources.

When the researchers tallied the choices of all the participants, both healthy and intelligent-looking leaders were chosen more often. However, health cues were more clearly influential in choosing a leader than intelligence cues. In 69 percent of choices, participants favored more healthy-looking faces over less healthy-looking faces. The tendency to choose healthy faces was dominant regardless of the scenario presented. “Overall, our findings suggest that although intelligence may be important for leadership in certain circumstances,” the researchers write, “health […] appears to dominate decision making in all contexts of leadership.” Intelligent looking faces were only preferred over less intelligent looking faces in scenarios that called for diplomacy or original thinking: the renegotiation and the new market scenarios.

The implications of this study are twofold, covering both the organization and the individual. For organizations, the study suggests that a subtle bias may affect leadership succession planning and unnecessarily favor healthy individuals. According to the paper, “a relatively healthy-looking leader may have a better chance of gaining sufficient levels of followership investment to initiate change. On the other hand, a potential leader who looks relatively less healthy may be over-looked even if they are better suited for the job.”

For individuals, the implications are even more straightforward: get healthy.

Spisak suggests, “If you want to be chosen for a leadership position, looking intelligent is an optional extra” only applicable in certain contexts. Looking healthy “appears to be important … across a variety of situations.” The researchers even suggest this is why modern politicians have put such care into their health and appearance.

If you use the New Year to set new resolutions and craft a development plan for hitting those goals, then resist the temptation to focus just on career or health goals or to separate out the two in your mind. Instead, think holistically. If you’re looking to get that promotion, your health matters just as much (if not more) than the experience and knowledge you plan to gain this year.

[image error]

January 1, 2015

Things to Stop Doing in 2015

Stop multitasking (it can be done).

Stop procrastinating, saving work for tomorrow, and waiting to be inspired to work.

At the same time, stop working at an unsustainable pace. It makes leading more difficult, and to do things better, you have to stop doing so much.

If that’s not possible, at least stop complaining about how busy you are. Everyone will thank you.

Stop feeling like you have to be authentic all the time. It could be holding you back.

Stop holding yourself back in these five other ways, too.

Stop being so positive — research shows it’s not all that helpful for achieving your goals.

Stop overdoing your strengths (lest they become weaknesses).

And when it comes to evaluating others, stop mistaking confidence for competence.

Stop giving negative feedback as a “sandwich.”

Stop overlooking the women in your organization. And stop relying on diversity training programs to fix the problem. They can’t solve it.

Speaking of things that don’t work: Stop ideating and brainstorming.

Stop trying to delight your customers all the time.

Stop searching for a silver bullet to your strategy dilemmas.

That said, stop using so many battle metaphors when you talk about strategy.

And please, stop using terrible PowerPoints and these equally terrible words in your business communications.

Stop sitting so much. Seriously.

Stop getting defensive. (Not that we’re accusing you.)

And if you can’t stop doing any of these things… stop believing that you have to be perfect.

[image error]

December 31, 2014

Choose the Right Innovation Method at the Right Time

In the industries plagued by the most uncertainty, how do companies hold on to their ability to innovate? And how do they achieve, and keep, an innovation premium in the market?

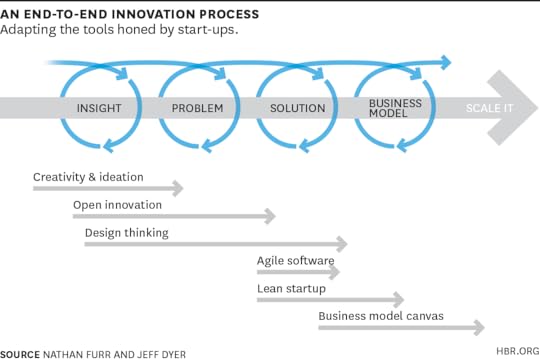

We found that managers who help their firms create and maintain an innovation premium use a different set of tools than their more traditional counterparts — tools honed in start-ups and specifically designed to manage uncertainty.

Although these tools come by many different names (e.g., lean startup, design thinking, discovery-driven planning, agile software, and so forth) they actually have a remarkable commonality. Where they differ is primarily with regard to the steps of the innovation process they emphasize. For example, design thinking emphasizes understanding customer problems, whereas lean emphasizes solution experiments. One other important difference: They tend to be tools that start-ups easily adopt, but that managers wrestling with day-to-day execution have struggled to incorporate.

In our research, summarized in The Innovator’s Method, we synthesize these perspectives into an end-to-end innovation process and show how successful corporate innovators have adapted these principles to increase their innovation premium:

Although the process may appear simple, even obvious on the surface, the billions of dollars wasted on failed innovation projects annually suggest that it is not so easy to implement. Naturally, innovation is a messy process and you may find that you start somewhere else on the figure (e.g., you already have a solution or business model innovation in mind), but the figure helps us remember that even in these cases, each element has to be addressed before you try to scale the business—or you are in grave danger of failure.

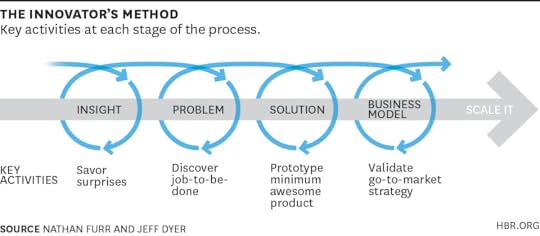

In the figure below, we summarize the key activities of each step.

Innovations always begin with an insight about a potential need, solution, or business model. These are the flashes of inspiration, the clues there is a problem, and the surprises that are lurking in the world around you. For example, as a sales representative at Baxter, Gary Crocker had a busy schedule, but he still spent as much time as possible observing the professionals he served, to understand them better, looking for surprises. As he watched cardiac surgeons work in the operating room, he noticed something obvious and yet completely overlooked: there was a lot of blood. Why? Of course, because it was a cardiac operation. But the blood was causing huge problems for the surgeons trying to work quickly and precisely. Crocker went on to found his first of several multi-million dollar companies, this one to create the “plumbing” that cardiac surgeons now use around the world to manage blood flow during cardiac operations. In our book, we discuss the observation behavior and several other behaviors that we saw innovators use to increase the chances of encountering a valuable surprise.

Once you have an insight, most innovators make the mistake of leaping to straight to solutions without first understanding the real problem, the job-to-be-done. For example, when managing the technology support function first became a major problem for software makers, most entrants into this market assumed the solution was to create a knowledge database for technicians. But Mike Maples Jr. and his team eschewed this approach, first spending weeks watching technicians, timing their calls, listening to the conversations, and mapping out the process. They discovered that only 25% of the call was spent actually addressing the problem with a knowledge database. The other 75% of the call was spent on simple administrative details, such as determining the operating system and the level of support needed. Maples and his team went on to build a multi-million dollar product based on a deep understanding of the problem that all their competitors missed.

After you know what problem you are solving, you need to find the fastest path to the solution. Everyone understands the value of prototypes and many have heard of the idea of a minimum viable product. What we found was that innovators used four types of prototypes: theoretical prototypes, virtual prototypes (or pretend-o-types), minimum viable products, and finally the minimum awesome product, in that order, to reduce their risks and quickly validate the solution. One of our favorite examples? Coin. The founders felt that most individuals hate carrying around multiple credit cards and had the idea to create a single digital credit card that contained the information to be used as multiple credit cards. They created a simple video describing the features of a product that didn’t exist yet and asked for pre-orders to validate demand. The video sold tens of thousands of units well over a year before they actually delivered the product to the market. Using little more than a video (a virtual prototype), they validated that customers wanted to purchase and were able to get details about what features they most valued.

Finally, although incremental innovations can leverage your existing business model, most new innovations require a new business model. You have to experiment to discover the right business model, particularly your go-to-market strategy, or the unique way that your customers find out about, evaluate, purchase, use, and connect to your product. This is a familiar concept. What’s different is the depth of customer engagement you need to discover the right go-to-market strategy unique to your innovation. Sometimes the changes are simple. Several years ago Merck launched a serotonin reuptake inhibitor that, despite having the same mechanism of action as Prozac, experienced dramatically low sales. Only after interviewing physicians and patients did they discover that customers associated these products with a label. Prozac owned the “depression” label, but the “anxiety” label was relatively uncontested. Merck re-launched around the new label and achieved billions in sales. After you have nailed these elements of your innovation, then you are ready to scale. Before that, scaling will kill your innovation because it obfuscates the real source of value and burns your precious resources.

Although the innovation process is messy and non-linear, every innovation we studied went through similar steps. If you are starting with a problem, work through the steps. If you already have a technology or product, go back to understand the problem you are solving. Avoid using surveys and market studies — really go deep and understand the hearts and minds of your customers during the process. Although you won’t eliminate the risk of innovation, you can dramatically reduce it and dramatically reduce the cost of failure, giving you multiple chances to launch a home run.

[image error]

Signs That You Lack Emotional Intelligence

In my ten years as an executive coach, I have never had someone raise his hand and declare that he needs to work on his emotional intelligence. Yet I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard from people that the one thing their colleague needs to work on is emotional intelligence. This is the problem: those who most need to develop it are the ones who least realize it. The data showing that emotional intelligence is a key differentiator between star performers and the rest of the pack is irrefutable. Nevertheless, there are some who never embrace the skill for themselves — or who wait until it’s too late.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Office Politics

Communication Book

Karen Dillon

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Take Craig (not his real name), a coaching client of mine, who showed tremendous potential and a strong ability to drive results for his company. The issue with Craig was the way in which he got those results. When asked to describe him, his colleagues would say things like: “he’s a bull in a china shop;” “he has sharp elbows;” and “he leaves dead bodies in his path.” His approach to executing projects was not sustainable as he wasn’t able to motivate, attract and retain good talent. His direct reports pointed out how frequently Craig seemed oblivious to how he demeaned others. His boss commented on Craig’s impatience and his propensity to lash out at his peers. When I shared this feedback with Craig, he seemed taken aback and was convinced that I had heard wrong. He didn’t have the self-awareness or empathy that are hallmarks of emotional intelligence.

Here are some of the telltale signs that you need to work on your emotional intelligence:

You often feel like others don’t get the point and it makes you impatient and frustrated.

You’re surprised when others are sensitive to your comments or jokes and you think they’re overreacting.

You think being liked at work is overrated.

You weigh in early with your assertions and defend them with rigor.

You hold others to the same high expectations you hold for yourself.

You find others are to blame for most of the issues on your team.

You find it annoying when others expect you to know how they feel.

So what do you do if you recognized yourself in this list? Here are four strategies:

1. Get feedback. You can’t work on a problem you don’t understand. A critical component of emotional intelligence is self-awareness — this is the ability to recognize and stay cognizant of behaviors in the moment. Whether you engage in a 360 assessment or simply ask a few people what they observe, this step is critical in heightening your sense of what you do or don’t do. And don’t just find excuses for your behavior. That defeats the purpose. Rather, listen to the feedback, try to understand it, and own it. When Craig initially heard what others thought of him, he quickly became defensive. But when he accepted the feedback, he moved to owning it and became determined to change.

2. Beware of the gap between intent and impact. Those with weak emotional intelligence often underestimate what a negative impact their words and actions have on others. They ignore the gap between what they mean to say and what others actually hear. Here are some common examples of what those with low emotional intelligence may say and how it’s actually heard:

What you say: “At the end of the day, it’s all about getting the work done.”

What others hear: “All I care about is the results and if some are offended along the way, so be it.”

What you say: “If I can understand it, anyone can.”

What others hear: “You’re not smart enough to get this.”

What you say: “I don’t see what the big deal is.”

What others hear: “I don’t really care how you feel.”

Regardless of what you intend to mean, think about how your words are going to impact others and whether that’s how you want to them to feel. Craig was notorious for saying things that made others bristle, but he began to consider the impact of his words. Before every meeting, he spent a few minutes asking himself: What is the impression I want to make? How do I want people to feel about me at the end? How do I need to frame my message to reach that objective?

3. Press the pause button: Having high emotional intelligence means making choices about how you respond to situations, rather than having a knee-jerk reaction. For example, Craig tended to interrupt and shoot down other people’s ideas before they could complete their thoughts. This behavior was a reaction to his fear of losing control of the discussion and wasting time. So he started to take pauses before reacting. There are two important pauses to take:

Pause to listen to yourself. When Craig was getting impatient and frustrated in discussions, he often felt his jaw clench and his chest tighten. By recognizing these physical signs, he was able to pause and remind himself that he feared losing control. As a result, Craig was better able to determine how he wanted to respond, rather than relying on his default of lashing out.

Pause to listen to others. Listening means helping others feel like you’ve understood them (even if you don’t agree with them). It’s not the same as not saying anything. It’s simply giving others a chance to convey their ideas before you jump in.

4. Wear both shoes. People often suggest you “put yourself in the other person’s shoes” to develop empathy, a key component of emotional intelligence, but you shouldn’t dismiss how you feel. You need to wear both shoes — understanding both your agenda and theirs and seeing any situation from both sides. Craig shifted his approach from “Here are my concerns” to “These are my issues, and I hear your concerns. Let’s determine a way forward that takes both into consideration.”

Strengthening your emotional intelligence takes commitment, discipline, and a genuine belief in its value. With time and practice, though, you’ll find that the results you achieve far outweigh the effort it took to get there.

[image error]

Who Provides Tech Support for the Internet of Things?

The Internet of Things (IoT) is a funny phenomenon. While the phrase connotes “interconnectedness,” the truth is that these new gadgets, applications, interfaces, and systems aren’t nearly as interconnected as we expect them to be.

Think about it. Why do we have these “things”? We want our lives to be easier; we have connected “things” to gain control and convenience. “Things” allow us to do something, achieve multiple tasks and glean useful, actionable information. They allow us to shop, research, activate, change, transfer, call, watch, monitor, control, and so on, and we expect to be able to realize those tasks wherever and whenever we want – even remotely. Sure, the “things” we’re using to accomplish those tasks work well individually (for the most part), but how many of them work well together and do so consistently? Who can help us make that happen? Who will help when any or many are not inter-operating as expected?

Today, customer service and support for connected devices are primarily focused on the device or system purchased, solely supporting the product at hand by the brand that built or sold it. Tablet companies can push updates to a specific device and provide video chat support, but most can’t or won’t help connect that device to the smart thermostats in a customer’s home. A home security or smart lighting provider can assist with the use of its app on a smartphone, but can that same provider assist with the use of an aggregator solution that initiates a series of activities? For instance, if a smartphone app recognizes a consumer is pulling into the driveway, which activates the garage door, which triggers the lights and deactivates the security system, can that lighting provider help when the lights don’t go on?

Connected technology is impressive, but it leaves us wanting more from the products themselves, and the brands that make and sell them. The optimization and integration of devices remains cumbersome and disjointed, and as connected “things” venture further and further away from traditional technologies for which some level of support is already provided, toward products and packages like Internet-powered toothbrushes, crock-pots, and home security systems, the support gap will only grow. Simply put, this disconnectedness is a byproduct of impressive innovation without the service and support transformation necessary to underpin the real-world use of those interrelated applications.

Manufacturers and retailers are not to blame here. Supporting the IoT is no easy feat. In fact, according to Gartner, the IoT – excluding PCs, tablets and smartphones – will grow to 26 billion units installed in 2020. With far fewer IoT devices today (research suggests an average of five to nine devices and technology services in every U.S. home), there are already tens of thousands of different ways that these devices and services might connect and interact with one another in a single home or small business on any given day or week. That creates countless, unpredictable service points that represent a very complicated technical headache for end users. Just imagine the number of phone calls, chat sessions, text messages and self-help searches that will be necessary to reconcile consumers’ configuration, activation, integration, backup, and security needs across this diverse network of devices by 2020. Now imagine how difficult it could be to establish and maintain a positive customer experience among all that possibility, especially if the definition, scope, and delivery of technical assistance and support don’t change from the current parameters.

The necessary cross-brand integration presents both a huge challenge and a significant opportunity for companies in the IoT business. Tech support is no longer about individual manufacturers, retailers, telcos, and internet service providers’ product sets; it’s about a continuous service experience of the full connected environment to deliver on consumer expectations, while adding customer value to drive loyalty.

Which companies will be the first to remove their blinders and start thinking – and acting – beyond their own brands and their traditional scopes of service to help consumers experience the control, simplicity, and convenience the IoT has to offer?

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers