Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1334

December 30, 2014

The Most Innovative Companies Have Long-Term Leadership

Call 2014 the year of innovation. A Gartner survey of almost 500 executives at global corporations revealed that growth is this year’s top priority. Google Trends reveals that interest in disruptive innovation crept up to peak levels this year. It seems that every time you hop on a quarterly earnings call, the CEO mentions innovation. The M&A markets are frothy, corporations are investing in Silicon Valley labs, and even PhDs looking for jobs in business schools are finding it tough to find homes without “innovation” somewhere in their background.

If innovation is the foundation to building the future, this focus should be reassuring. To overcome disruption and remain relevant into the future, companies need to build the businesses that will replace their legacy offerings.

The only problem: Being excited about a new corporate commitment to innovation assumes corporate investments aren’t the equivalent of cash flushed down the toilet.

And even with the best of intentions, most CEOs start off disadvantaged in building the next big thing. Many of the reasons for this are well documented. Executives have conflicting incentives, the wrong investment metrics, and enormous margin pressure. But sometimes, executives manage to overcome all of these structural challenges and push the right types of ideas regardless of the barriers. Companies like Apple, Amazon, General Electric, and IBM demonstrate the possibility for ongoing reinvention in pursuit of the next big idea.

But it’s more than simple disregard for the quarterly pressures of the public markets that powers these industry behemoths. They also share another quality uncommon among peers. All of their leaders have staying power. Regardless of swings in the public markets, Page, Bezos, Immelt, and Rometty expect to stay in their jobs for a while.

Staying power is vital for innovation. Consider the industry I call home, enterprise software. The typical enterprise software startup that IPOs is at least 7 years old (to say nothing of those that try and fail). Like most businesses, in the beginning it’s nothing more than an idea. But it’s an idea that demands attention, investment, and a long view of the market. Only with patience and perseverance will it flourish. And after these startups hit the public markets, they’re still generally too small for the average CEO of a Fortune 500 business to care about. In the year before Google IPO’d, it did about $962 million in revenue. The same year, Microsoft did $32.1 billion. Had Microsoft owned Google’s search engine at the time, it would have been an tiny piece of the revenue pie.

Just 10 years later – the revenue Google derived from its advertisements was larger than the largest Microsoft business. How times change, right? And that’s the point.

Tackling big audacious problems take time. It’s why venture investors and entrepreneurs tend to be committed for the long haul. Big ideas start small. Everything requires a foundation of results before it can expand. Sure, the distribution and brand that big companies bring to the mix can be useful in accelerating the pace of change, but innovation still requires long timelines. And the vast majority of public company executives don’t share those timelines.

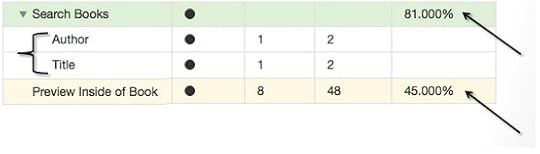

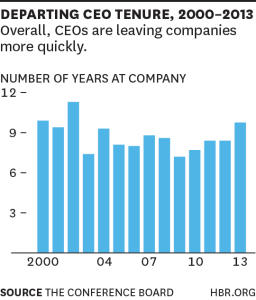

The unfortunate truth is that most public company executives don’t last too long in their roles. Based on an annual survey conducted by the Conference Board, the average CEO departs her role with fewer than 9 years under her belt. If it takes a decade to build a big business, that’s already too short of a time to be the “executive sponsor” for the project. If it only takes 5 years inside a bigger machine, that still means the CEO only has 4 years to start the project if she wants to see it come to fruition. Everything else might die on the vine in transition.

The unfortunate truth is that most public company executives don’t last too long in their roles. Based on an annual survey conducted by the Conference Board, the average CEO departs her role with fewer than 9 years under her belt. If it takes a decade to build a big business, that’s already too short of a time to be the “executive sponsor” for the project. If it only takes 5 years inside a bigger machine, that still means the CEO only has 4 years to start the project if she wants to see it come to fruition. Everything else might die on the vine in transition.

And 9 years is just the average. Look at Hewlett Packard for a horror story. Since 1999, HP has seen 6 CEOs and interim CEOs. Given the constant turnover, even the best of intentions could be made irrelevant. With HPs projects running on annually approved operating budgets and constant executive turnover, many corporations simply can’t be trusted to invest in innovation over the long haul it requires.

Consider what it has taken to push General Electric into the software business. For more than a decade, GE has been adding sensors to its industrial devices and enabling central collection of that data. Slowly, the company built out proprietary software systems to allow its customers to get more out of its product. Today, GE is emerging as a leader solution provider in the “Internet of Things.” But if not for execution against a decade-long plan, it would all be for nothing.

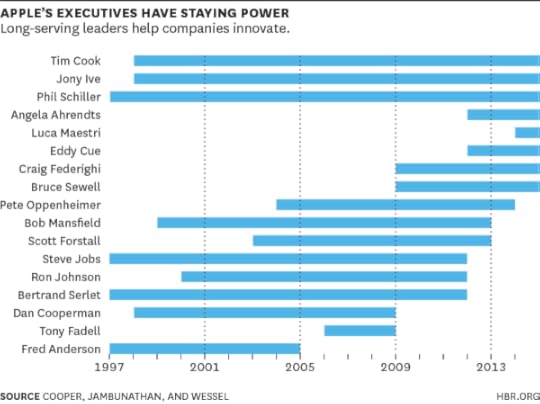

People often like to reference Apple as an example of a company that figured out how to use innovation to drive growth. Certainly they did. But staying power was a key part of the recipe at Apple. Executives spent years plotting their takeover of the mobile computing world and executing. They focused on a few enormous projects and did them incredibly well. And they lasted. From 1997 to 2014, 9 of Apple’s 17 most senior executives lasted more than a decade in the executive team (with 5 of them lasting more than 15 years).

With that kind of dedication, companies can achieve great things. But that’s more than enthusiasm. That’s staying power.

The fact that 2014 is the year of Innovation in the corporation isn’t surprising. We’re in an up market and people are more excited about technology than ever before. But taking excitement and turning it into results requires more than investment. It requires staying power. Projects need to be funded, sponsored, and protected for the long haul.

In the second part of this series I will dive a little deeper into the economics of this process. In the third part of this series I will make some suggestions about how to pull it all off in a large organization.

[image error]

Your Elevator Pitch Needs an Elevator Pitch

Ah, the elevator pitch. A favorite tool of the networking masses. A rite of passage of sorts. You’ve heard the scenario: you step into an elevator and go up one floor. The elevator doors open and in walks the client of your dreams. They start some small talk and ask, “What do you do?” and you’ve got the rest of the elevator ride to respond. How do you answer that in 20 seconds in such a way that gets them interested? The answer is simple. You need an elevator pitch for your elevator pitch.

Today, you’re getting both my word-for-word elevator pitch, my elevator pitch’s elevator pitch, and the secrets behind what makes it all so effective. It all starts when someone asks me…

“What do you do?”

“You mean, in addition to being an international bodybuilding champion?” (I’m 5’10” and a buck thirty-five, soaking wet. When I step on ants, they live. It’s painfully obvious that I’m not an international bodybuilding champion.)

Usually, they laugh. Usually, I laugh too. Then I continue…

“Well, you know how email and texting and social media have pretty much taken over how we communicate?”

“Yes.”

“We’re more connected than ever, but yet…more disconnected than ever. So I teach managers the secrets of true connection in a way that gets immediate results.”

“How do you do that?” (or “What do you mean?” or “What kind of results?”)

“Well, here’s an example. A company hired me because their management staff wasn’t connecting with their employees. It wasn’t their fault, they’ve just never been taught the right way to do it, right? So I went to their management retreat, taught everyone my 4-part formula, and now morale is up and productivity is up 38%. That’s why I’m constantly on the lookout for managers who don’t know the formula. They’re easy enough to spot. They don’t feel like managers, they feel like babysitters. They say things like, ‘This job would be so easy if it weren’t for the people.’ And they don’t have enough time to deal with all that people stuff and get their own job done so they can make the kind of money they deserve and have the kind of time and lifestyle that they don’t even realize they’ve been missing out on. So when you ask me what I do, I give managers their lives back. Life is too short for two out of every three Americans to hate their jobs. I get the feeling you know people like that though, right?”

Now obviously, this elevator pitch is a lot longer than 20 seconds. But here’s why I don’t buy the “20 second” rule.

When people ask “What do you do?” they’re just making polite conversation. With rare exceptions, they don’t really care. If you can’t make them care, then 20 seconds of their attention is generous. But if you do pique their interest, they’ll hold the elevator door and listen to you all day long. So don’t try to cram everything into 20 seconds. Instead, the best use of that first grace period is to make a bid for an attention extension. Now that you’ve seen how I do it, here’s how it works:

Start with a verbal slap. First things first. You’ve got to break their expectations. Most people answer the “What do you do” question with a single, predictable sentence: “I am an architect.” But the human brain only pays attention to interesting things. If you want to be interesting, you need to stand out. Giving them a verbal slap in the face helps break the patterned thought process that made them ask the question in the first place. Patterns, by their very nature, don’t contain anything that stands out. Pattern thinking is why there is almost a zero chance they will remember you.

To “wake them up” you probably won’t be able to use my self-deprecating, bodybuilding joke. That’s the point. You’ve got to say something DIFFERENT – something authentic. Something so totally “you” that they are forced to realize that you are a unique human and not just another “normal” interaction that their robot brain can coast them through. I’d write this for you if I could, but I can’t. Nobody can.

Then ask a problem question. Once you’ve verbally shaken them awake, your next goal is to pose a problem that you suspect they will identify with. This must be spoken as a question. Questions have always been, and always will be, far more engaging than statements. The problem question from my elevator pitch is, “Do you know how email, texting, and social media have kind of taken over how we communicate?”

Some respond with a simple “yes” and some launch into a diatribe about how awful modern technology is. That’s okay, I let them talk. Either way, I’m aligning myself with them against a common enemy. This is one of the most powerful rapport-building strategies there is, besides maybe shared laughter. However, if there is any doubt that I’ve just made a new BFF, I throw in one last rapport builder…

Go to the noddable. A noddable is an inspirational or wise quote that is so catchy and agreeable, it gets just about everyone nodding. People will agree with these so strongly that they may even let an audible, “Mmm!” or an “Amen!” escape their lips. If you want to know if your statement is a noddable, post it as a text image or “meme” on Facebook and see if it produces a response on the like and share buttons, or if the comments below it end with “#truth”.

My noddable is: “We’re more connected than ever, but yet…more disconnected than ever.” (I know…deep.) For additional rapport points, try this advanced technique: pause after the word “yet.” This allows your listener’s own brain to fill in the punchline even before you say it. When they do that, they have ownership of the quote and a small part of them is convinced that they thought of it themselves. Then when you say aloud what they’re thinking, it creates a moment of “great minds think alike” bonding.

So at this point, I’ve already broken their expectations and built some strong rapport very quickly – and I still haven’t even answered their question. That’s coming next. Kind of.

Finish with the curiosity statement. This is where you pretend to answer the “what do you do?” question. However, your answer will only want to make them ask another question. Here’s the simple formula for a good curiosity statement:

“I help/teach ________ (ideal client) to ________ (feature) so they can _________ (benefit).”

Mine was, “I teach managers the secrets of true connection in a way that gets immediate results.” This is so much more powerful than “I’m a speaker and author.” Also, the intriguing vagueness of “secrets” and “results” almost forces them to ask some kind of follow-up question. The hard work is done. Now that rapport and curiosity have been built up, you can deliver your true elevator pitch and make it almost as long as you want.

What about that actual elevator pitch? Even though the heart of this article is really about the elevator pitch before the elevator pitch, below is included a brief overview of the thinking behind my actual pitch too. It’s not perfect, but it has served me very well.

The first thing you’ll notice is that mine is long. It’s at least twice as long as the 20 second so-called “limit.” It starts with a true, results-based story of an individual or company I was able to help in a measurable way. It’s peppered with persuasive language and what I call “hidden salesmanship.” Then it mentions exactly who I’m “on the lookout” for. “They’re usually easy enough to spot because…” then I insert three pain points that my target market will identify with. All the while I’m building my level of enthusiasm and using rhythm, tone, and body language to do the exact opposite of a “verbal slap” – I’m putting them back into patterned behavior. Only this time, it’s a pattern of agreement and not a pattern of resistance.

By the time it’s their turn to talk again, I’ve taught them exactly the type of referrals I’m looking for. In addition, if they’re in need of my services, they’ll be feeling just the right amount of pain that will likely motivate them to begin describing their situation. When they do, I’ll get a meeting by saying, “Hmm, that sounds important enough for us to maybe sit down and talk about.” Surprise, surprise. They agree.

But the last thing you want to do is to make them feel like they’re being pitched to. If you get the sense that it’s turning into a commercial instead of a conversation, then you’re doing it wrong. Stop pitching and ask another question. You should only be doing between 15-20% of the talking.

A final caveat: the number one rule with any communication is to be authentic. Feel free to model my pitch, but unless you make it fit your personality, it will come across as phony and manipulative. And nothing ruins a pitch faster.

[image error]

Working Too Hard Makes Leading More Difficult

In 2007, the same day Steve Jobs introduced the first iPhone and the same year Twitter debuted at SXSW, executive coach Marshall Goldsmith published a book called What Got You Here Won’t Get You There.

In it, Goldsmith makes the case that many of the behaviors that initially propel high-achievers up the corporate ladder are paradoxically the same ones preventing them from reaching the very top. Habits like winning too much (the need to win every workplace disagreement, even when it doesn’t matter), adding too much value (adding your two cents to every discussion), and goal obsession (becoming so wrapped up in achieving short-term goals that you forget the larger mission).

Early in your career, these behaviors demonstrate that you are driven. But the moment you step into a position of leadership, they become counterproductive.

Since Goldsmith’s book first appeared in print, another double-edged workplace habit has cropped up—one that would have been difficult to foresee when he first conceived of his book.

Failing to disconnect.

Like many of the practices Goldsmith identifies in his book, it is surprisingly hard to recognize the damage working excessive hours inflicts both on leaders and their teams.

In part, it’s because when you’re first starting out, working evenings and weekends gets you noticed. It is what differentiates you from less motivated colleagues, yielding early recognition and promotions. In this way, hard work becomes ingrained as part of your identify.

While working long hours is often beneficial to early career advancement, as you rise to a position of leadership, maintaining this practice can damage your career prospects.

For one thing, it’s because of shifting job responsibilities.

Early in your career, the primary measure of your performance is how well you manage yourself. But the higher up you go, the more likely you are to have a job that involves managing others. No longer are technical abilities quite as important. Now, success hinges on interpersonal skill.

What happens to our interpersonal skills when we work ourselves to exhaustion? Studies indicate that when we’re low on energy, we tend to misread those around us, typically in a more negative fashion. Happy faces appear more neutral. Neutral face start to look like frowns. What’s more, when we’re fatigued we find it harder to resist lashing out at perceived slights. Not only to do we incorrectly perceive the world around us more negativity, we’re also more likely to act upon that information.

Weaker communication isn’t the only danger of failing to disconnect. So is impaired judgment.

The more senior you are in an organization, the more frequently you’re called upon to make complex decisions. And when it comes to navigating uncertainty and negotiating risk, the research is clear: Decision quality plummets when we’re tired. The more choices you face, the more critical it is for you to restock your energy. Overwork and the sleep deprivation it fosters prevent you from seeing problems clearly and identifying creative solutions.

But perhaps the biggest hazard of failing disconnect once you arrive in a senior position is that your actions make it harder for your team to stay engaged. Why? Because suddenly, your workplace habits are no longer a personal matter. As a leader, your behaviors communicate expectations.

A 2010 study looked at what happens when employees are unable to psychologically detach from work during off-hours. Hundreds of employees at a variety of organizations were surveyed twice—once at the beginning of the study and then again a year later.

The findings were unambiguous. Not only were employees lacking work-free time off less invested in their job a year later, they were more likely to report emotional exhaustion and physical symptoms, like headaches and stomach tenseness.

To be sure, working long hours isn’t always a path to disengagement. As anyone who has experienced sitting in an empty office on a Saturday morning can attest, freely choosing to work on the weekend is a completely different psychological experience than being expected to do so.

Which underscores yet another reason disconnecting from work is vital to leaders’ performance: when laboring non-stop becomes standard operating procedure, it’s difficult for employees to feel like working hard is their choice.

What can we all do to make disconnecting easier? Here, a recommendation Goldsmith noted in his book nearly a decade ago continues to have value: think small.

Find one thing you can change about your behavior and start there. Most attempts at behavior change—from trying to eat healthy to adopting a grueling new exercise regimen—fail for the same reason: they’re too ambitious.

Rather than attempting to modify all of your work habits, find one modest change that you feel comfortable implementing. For example, try leaving your smartphone in another room when you get home in the evening, so that you’re not tempted to check your work email every time your smartphone appears in your peripheral vision.

Or, spend a few minutes learning how to program the emails you send in the evening to arrive first thing in the morning, so that you’re not sucked into a back and forth with colleagues at all hours.

Just as useful: Stop “trying to disconnect” and find an enjoyable activity to fill your time outside the office. Ideally, identify something active you’d like to master: take up biking, join a sports league, sign up for baking lessons. Not only can activities like these refresh your thinking and offer you the perspective that comes with distance, they also enable you to reframe your time away from the office in terms of gain instead of loss.

Rather than chiding yourselves not to work after hours, you are better off proactively engaging in activities you can look forward to doing.

It’s what behavior change experts know: Breaking a bad habit takes more than trying to stop. It requires finding something more appealing you can do instead.

[image error]

The Ideas That Shaped Management in 2014

We look forward to the annual task of putting together an end-of-year reading list to keep you busy over the holidays. It gives us an opportunity to look back over all of the ideas and advice we published during the year and see what patterns emerge. We consider which ideas we think will have the best chance of really changing the way people and their organizations work. Which research best answered questions we hadn’t even thought to ask? Of all the ways the world changed in 2014 — economic, cultural, technological, all three — which will matter most to us in 2015? And which pieces of expert advice were most sensible, badly needed, and clearly explained?

So, here’s this year’s list: questions answered, helpful advice, and five themes that came up again and again. We hope you enjoy it.

Mysteries, Solved

The One Thing About Your Spouse’s Personality That Really Affects Your Career

The Real Reason New MBAs Want to Work for Goldman Sachs

Why Didn’t the Other Fukushima Reactor Melt Down?

How Old Are Silicon Valley’s Top Founders?

Would Body Cameras Change Police Behavior?

Why Women Don’t Apply for Jobs Unless They’re 100% Qualified

What People Are Really Doing When They’re on a Conference Call

Useful Advice on How to Do Many Things

Say “This Is Crap” in Different Cultures

Negotiate with Someone More Powerful Than You

Answer “What’s Your Greatest Weakness?”

Start a Conversation You’re Dreading

Make Yourself Work When You Just Don’t Want To

Retail Is More Digital Than Ever, but the Physical Store Is Doing Just Fine

E-commerce Is Not Eating Retail

Why Websites Still Can’t Predict Exactly What You Want

How Data Visualization Answered One of Retail’s Most Vexing Questions

At Amazon, It’s All About Cash Flow

What Chinese Companies Can Teach Silicon Valley

What Airbnb, Uber, and Alibaba Have in Common

Xiaomi, Not Apple, Is Changing the Smartphone Industry

Alibaba Looks More like GE Than Google

Why Facebook Should Worry About Tencent

An Insider’s Account of the Yahoo-Alibaba Deal

How the Precipitous Rise in Inequality Happened, and How It Is Putting Us All at Risk

The Rise (and Likely Fall) of the Talent Economy

The Price of Wall Street’s Power

CEOs Get Paid Too Much According to Pretty Much Everyone in the World

Piketty’s Capital in a Lot Less than 696 Pages

Google Adds Benefits, Walmart Cuts Them; Oddly, the Logic Is the Same

The Internet Will Soon Be in Everything

How Smart, Connected Products Are Transforming Competition

Is HR As We Know It Over?

It’s Time to Retool HR, Not Split It

In Hiring, Algorithms Beat Instinct

Hacking Tech’s Diversity Problem

[image error]

December 29, 2014

Why Sales Ops Is So Hard to Get Right

According to “Spin Selling” author Neil Rackham, when Xerox first established a sales operations group in the 1970s to take on activities such as sales planning, compensation, forecasting, and territory design, group leader J. Patrick Kelly described his responsibilities as “all the nasty number things that you don’t want to do, but need to do to make a great sales force.”

Forty years later, the concept of sales operations or “sales ops” has become widely accepted as essential for effective sales management. With growing demand for data analytics, sales ops capabilities have become an even more important ingredient in sales force success. Perhaps the biggest challenge for sales ops leaders is delivering a huge diversity of work, while operating in a constantly changing business and technology environment.

As an example, a recent job posting on the website of a global healthcare company seeks an individual for a sales operations leadership position who can do the following:

Strategy:

•Contribute to the 1- and 3-year business vision as a member of the executive leadership team.

•Evaluate sales force strategies, plans, goals, and objectives.

•Contribute expertise to optimize sales force and territory sizing, structuring, and alignment.

Operations:

•Oversee sales performance analyses and reporting, territory alignment, and customer profiling and targeting activities.

•Administer quarterly sales incentive compensation plans and the goal setting process.

•Manage sales force automation and CRM systems and processes.

•Provide data, analyses, modeling, and reporting to support sales force quarterly business reviews.

Can one person really handle all this? The diversity of this sales ops role cuts across two dimensions. First, they face many decisions. The job requires knowledge of a range of sales force decision areas, spanning across categories that include strategy, organization design, talent management, incentive compensation, and sales force automation. Second, they must be strategic and tactical. The job requirements span a spectrum from tactical/support tasks (e.g. provide data for quarterly business reviews) to strategic/design activities (contribute to 1- and 3-year business vision).

Consider the competencies required to deliver on some typical sales ops projects.

Strategy:

Responsibilities such as evaluating sales force strategies or optimizing sales force size and structure require a deep understanding of specific sales management issues. These activities are best performed by people who have analysis/design expertise – individuals with strong creative and problem-solving skills, and project management and collaborative abilities. Such individuals have credibility with top executives, and generally crave creativity and variety in their work.

Operations:

Tasks such as administering quarterly incentive compensation plans or managing sales force automation systems require specific technical knowledge. These tasks are best performed by people who possess process/detail expertise – individuals who have a strong operational mindset, are passionate about quality control and efficiency, are technically adept, and generally like structured work, even if it’s repetitive.

An individual who provides the steadiness required to be good at supporting operations is unlikely to possess the competencies, such as outside-the-box thinking, needed for designing strategy. At the same time, an individual who is good at strategy probably lacks the process discipline required to be good at operational work. Asking a process/detail expert to do the work of an analysis/design expert, or vice versa, is a recipe for disaster.

What does this mean for sales ops leaders? They must hire, develop, manage, and lead a team of people with diverse and specialized competencies who do fundamentally different jobs and likely have dissimilar career aspirations. The team must not only cover a broad range of sales force issue expertise; it must also include process/detail experts and analysis/design experts working together aligned around the goal of sales force success.

Strategies that use both internal and external (outsourced) resources enable sales ops leaders to build and manage these diverse capabilities cost-effectively.

Building a strong internal team requires defining roles and responsibilities, developing hiring profiles, acquiring talent with the right characteristics (including analysis/design and process/detail capability) and continuously developing and nurturing that talent. Companies such as GE use internal teams to oversee many sales ops projects. Team leaders have competencies in quality management and process improvement methods, giving them analysis/design expertise, along with an appreciation for processes and details. These leaders can structure problems, delegate work, and help process/detail people see the big picture so that everyone works toward a common goal. Many companies look for sales ops talent outside the immediate group by encouraging job rotations with other company departments, such as finance or marketing. Also, rotations between the sales force and sales ops can allow salespeople/managers to build on their sales experience while broadening their skill set. As salespeople become increasingly tech-savvy, more will possess the technical and analytic ability and interest needed for a sales ops role.

Companies can also use outsourced resources to deliver many sales ops capabilities. Some outsourcing partners excel at process/detail work; others bring analysis/design expertise. Onshore partners can provide functional and industry expertise, based on their experience working with many companies. Because of advancing technology, disappearing cultural barriers, and greater business expertise among offshore talent, many companies are using offshore partners for both types of work, allowing them to source the best expertise while reducing long-term costs.

The right person to lead sales operations is someone who respects both the analysis/design and the process/detail mindset, who can envision the business and technology future, and who can work with leaders across the organization, as well as with external partners, to enable ongoing sales force success.

[image error]

Your Agile Project Needs a Budget, Not an Estimate

Nearly every software development project starts with one question: How much is this going to cost? Perhaps it’s a stakeholder who asks the question: a CEO, Board member, VC, or boss. Maybe it’s been asked another way — How long will this take? How many stories can we get into this next sprint? How many people do we need to hire to get this done? How much money do I we need to raise?

These are all variations on the same question — how much effort is this going to cost in terms of time and/or money?

There are two common replies to this question:

We don’t know;

Let us estimate and get back to you.

Stakeholders and decision-makers don’t like the first reply because they desperately need an answer to their question and they don’t have the knowledge to answer it themselves. Technical teams don’t like the second answer, because estimating takes a ton of time and it’s often abused — stakeholders sometimes turn the “estimates” into maximums and get upset if the team exceeds them.

Yet the truth is: It’s the responsibility of the technical team to answer the question “How much is this going to cost?” because technical teams are the ones that have the most relevant knowledge to answer it. If I ask you, “How much does it cost to build a ballpark?” only those of you who have first-hand experience building a ballpark can truly answer. The rest of us are taking a stab in the dark.

Here’s the thing: “How much is this ballpark going to cost?” is a fair question. Do I need to buy a shovel so I can build a sandlot? Or do I need to raise $100 million dollars to build Yankee Stadium? Stakeholders have decisions to make and deserve to have an idea of what their investment is going to cost and if it’s worth pursing.

A recent Harvard Business Review article revealed that one in six IT projects has a cost overrun of 200%. That’s a pretty high rate of failure for estimation. To minimize the risk of having your next technical project go awry, stop estimating and start budgeting.

For most strategic decisions, estimating is too precise. Estimating breaks down a software project into granular, 1-to-3 day chunks. For a $100,000 project, that’s a lot of work. For a $1 million project or bigger, that’s inordinate. If you attempt to break an entire project into estimates at the beginning of the project, you are truly wasting weeks of your time. Why? Because there is no way that you are going to get estimation at a granular level correct at the beginning of a project.

Instead, here’s a four-step, tactical approach to budgeting. It takes 20% less time than estimating, and it’s easily updated throughout the life of your project.

Step 1: Identify Decisions

Before you even begin to think about budgeting, or estimating for that matter, it is critical to know what decisions you are trying to make. What will you do once you have the data? What are you trying to learn?

Some examples of decisions you might be trying to make are:

Should we start this project or kill it?

Hire more people or outsource?

Start marketing this feature?

Build this project next or deprioritize it?

Launch a startup?

Allocate budget this quarter?

Code this set of stories next?

Do not proceed to steps 2, 3 and 4 without truly knowing what decision you are trying to make. If you can’t identify which decision you are making, estimating and budgeting are both a waste of time.

Step 2: Match Precision to Decision

Once you identify the decision you are trying to make, your next task is to match the tool to the job. For example:

If you are making a detailed decision (i.e. How much will we get done this iteration?), then estimating is a good tool for the job because its precision matches the granular decision you are making.

Otherwise, for more strategic decisions like many of the ones listed above, budgeting is a more appropriate tool.

Step 3: Budget

When the decision you are making is strategic, budget using a top-down approach, and get only as granular as you need to in order to have enough information to make your decision.

To illustrate, let’s say we are building an online bookstore. What high-level functionality might we need? Maybe something like these:

Shopping Cart

Browse Books

Search Books

Manage Inventory

Preview Inside of Book

Do we have enough information to answer “How Much Is this Going to Cost?” Probably not.

Getting more granular is warranted. Let’s break down “Search Books” into more detail.

Maybe we want to search books by

Title

Author

Within the Book

Let’s assume someone on our team has built a search component before, so we can say that search by “Title” will take 1-2 week, by “Author” 1-2 weeks, and “Within the Book” 4-16 weeks.

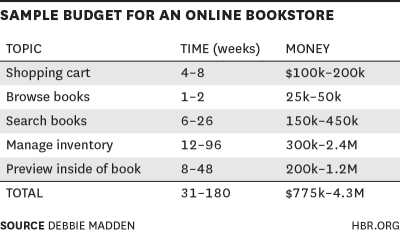

Do we now have enough information to answer “How Much Is this Going to Cost?” Probably not, so breaking it down further is warranted. If we take a ballpark guess as to the range of time each of the 5 topics will take, and associate that with a cost, we might wind up with:

To sum up, our data so far is:

The decision we aim to make is: Should we build this Online Book Store?

We expect the project to cost 775k – 4.3M

Do we have enough info to answer “How Much Is this Going to Cost?” Maybe.

If our budget is $500k, then we do have enough information. The answer is no, we can’t afford it.

If our budget is $5M, then we do have enough information. The answer is yes, we can afford it.

If our budget is $2.5M, then we do not have enough information.

Step 4: Ranges and Confidence Levels

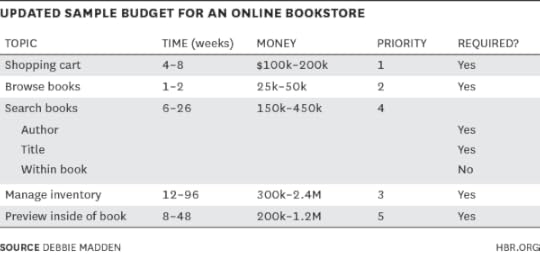

If our budget is $2.5M then more information is needed. We must now assign confidence levels to each topic. To do this, we:

Prioritize the topics

Identify which topics are “Required” vs “Nice to Haves”

In our online bookstore example, we come up with:

At this point, we’ve spent maybe 2-4 hours. If we had attempted to estimate this accurately, it would have taken 2-3 days.

A note here on Minimum Viable Products (MVP): If you are using a Lean Startup approach to building your software and are building an MVP, have two options. First, you can create one budget for the entire project and list the topics to include in the MVP as “Required” and everything else as not required. Or alternatively, you can create a budget solely for the MVP and leave the rest of the product intentionally vague. The beauty of a top-down approach to budgeting is that it’s so much quicker than estimating that you can easily run a budget multiple times throughout the project as you learn more.

Step 4 is difficult to do manually. To get accurate confidence levels, you need mathematical simulations. The best tool I’ve seen for this for software projects is Ballpark. (Disclosure: it’s an application developed by my coworkers. It’s free, and we don’t make money off of it.) It’s a budgeting tool that takes the input from a few hours of budgeting (as done above) and simulates thousands of possible outcomes using complex mathematical calculations, and in a matter of seconds spits out confidence levels that you can use to have a powerful conversation with your stakeholder to answer the “How much is this going to cost?” question.

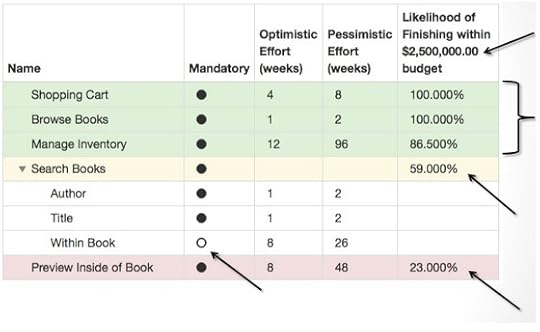

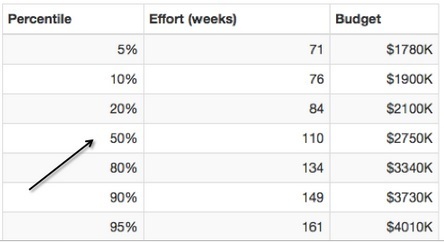

In this case, Ballpark tells us:

If we have a $2.5M budget, we have 100% confidence that we’ll finish our top 2 priorities within our budget.

86.5% likelihood of finishing “Manage Inventory”

59% likelihood of finishing “Search Books”

And 23% likelihood of finishing “Preview Inside Books”

Note that we input that “Within Books” isn’t mandatory. We can then rerun the simulation without “Within Book” and learn that if we only look at our mandatory topics, we get –

81% likelihood of finishing “Search Books” within our budget

45% likelihood of finishing “Preview Inside of Book”

Ballpark also calculates percentiles of the likelihood of each budget range. In the Online Bookstore example, we see there’s a 50% chance we’ll get the entire project done for $2.75M:

Ultimately, it is the tech team’s responsibility to give the stakeholder the answer to the cost question. Estimating is often a time-sink and not worth the effort this early on, with such a high-level question. So next time, try budgeting instead.

[image error]

Make Your Work Resolutions Stick

Many people have resolutions on the brain during this time of year. But it’s one thing to set goals — network more, learn to meditate, or get better at writing — and quite another to actually accomplish them. What are the right kinds of resolutions to make? How do you stay motivated? How do you turn your intentions into reality?

What the Experts Say

A lot of people set personal and professional goals this time of year but very few succeed. That’s because we often “set goals that go against our nature,” according to Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, professor of Business Psychology at University College London (UCL) and the author of Confidence. “We all have predispositions, character traits, and habits that we have built over many years,” he says. “Most of our New Year’s resolutions and goals involve breaking these patterns, which is very difficult to do and requires a lot of work.” So you have to be deliberate and strategic about setting goals and staying on track. “It’s important to have focus,” says Joseph Weintraub, the founder and faculty director of the Babson Coaching for Leadership and Teamwork Program. “You need to set the right goals within the right timeframe.” Here are some pointers on how to make your resolutions stick.

Be realistic

This is the time to “think small”— both in terms of the number of objectives and the timeframe in which you plan to accomplish them, according to Weintraub. He recommends setting no more than three goals — more than that is “too overwhelming” — with a deadline of a year or less. “For most companies and individuals, it’s hard to think five years ahead,” he says. Be ambitious — but not overly so, adds Chamorro-Premuzic. Choose things that challenge and stretch you but aren’t impossible. Also, make sure you’re setting “a goal that matters and is relevant” to you. “It’s so much work to create change, you have to really want it,” he says.

Focus on the positive

While at least one of your goals ought to involve developing an area of weakness, Weintraub cautions against getting hung up on self-improvement. “Too often we focus on what we need to do better,” he says. Instead: “Consider things you’re good at and set goals that leverage those strengths.” Say, for instance, you’re a strong writer or an effective public speaker; you should create goals that involve helping colleagues sharpen their presentations skills or using your writing abilities to earn a promotion. Your ultimate aim is to “move your organization forward and propel your career,” he says.

Further Reading

Nine Things Successful People Do Differently

Career planning Article

Heidi Grant Halvorson

Focus on getting better, rather than being good.

Save

Share

Commit publicly

Once you’ve decided on your goals, write them down and share them with others, including your manager, peers, direct reports, and friends and family. “When you make your goals public, you’re committing to them,” says Chamorro-Premuzic. Openness also enables others “to hold you accountable.” Weintraub explains that candor is especially important when your goal has an immediate impact on the people you work with. If, for instance, your goal is to reduce your micro-managerial tendencies, explain to your team that you will be delegating more often. “Tell people: ‘This is what I’m working on and here’s how I am trying to do it,’” he says. “Be explicit and overt about your intentions.”

Create a plan of action

To accomplish any goal — personal or professional — you need a step-by-step strategy. After all, says Weintraub, you wouldn’t expect to succeed at losing weight without systematically changing your eating and exercise habits. So “you need to think about tactics. Ask yourself: What actions do I need to demonstrate to accomplish this?” If your goal is nebulous — say, for example, to develop a more trusting relationship with your direct reports — you’ll need to think about specific behaviors that will help you, such as taking each of them to lunch individually and engaging with them on a more personal level. “And if you’re not seeing results,” says Chamorro-Premuzic, “you should also have a Plan B.”

Recruit support

An encouraging and supportive network is critical to reaching your goals, says Chamorro-Premuzic. Your support system could include colleagues, mentors, your significant other, a professional coach, or even peers outside your organization. They can be both your cheering squad and sounding board. “They will motivate you and encourage you, and when your morale is low, they will boost it.” Your support system will also help “reinforce that your goals are important to you and your career,” adds Weintraub. “The more you engage others in the process, the more likely you are to accomplish the goals you set for yourself.”

Set milestones

When you launch into working toward a new goal, you feel inspired and energized. But as the weeks and months trudge on, that initial excitement wanes, and it can be a struggle to find the time or motivation for it. To ease this problem, work toward short-term targets that bring you closer to your end goal. The success you achieve along the way should help you feel good about “the incremental progress” you’re making, says Chamorro-Premuzic. “You want to see change in a positive direction and small improvements,” he says. “The point is not to get better than others, it’s to get better than the old version of yourself.” To stay on track, “you need regular signals” that reinforce what you’re working toward, says Weintraub. It could be a reminder on your smartphone or a recurring “meeting” on your calendar where you “take the time out of your day to think about what your goals mean to you and your career.” At a practical level,” says Weintraub, you need “simple things to keep you going.”

Keep perspective

Nothing elevates cortisol levels like an approaching deadline. In some ways, the stress works in your favor, according to Wientraub. “It helps you focus on the goal,” he says. “It’s like when you know your doctor is going to put you on the scale at your next checkup, or when you know your boss is going to ask you about the status of a project at your next team meeting.” But while stress can drive performance, it’s important that you “don’t lose perspective” when unforeseen circumstances arise. “Don’t be too harsh on yourself,” says Chamorro-Premuzic. “You don’t want an unhealthy level of obsession about reaching your goals.” If a colleague needs you on a project or your personal life becomes unexpectedly complicated and completing your goal within the given timeframe becomes too difficult, cut yourself some slack. And don’t forget Weintraub’s golden rule of goal setting: “Strive for excellence, but sometimes good enough is good enough.”

Do:

Create goals that leverage your existing skills to move your organization and career forward

Share your goals with others and ask for support and encouragement when you need it

Create milestones along the way that help you appreciate the incremental progress you’re making

Don’t:

Become overwhelmed by a long list of goals; focus on no more than three at a time

Set yourself up to fail; create goals you can reasonably achieve

Beat yourself up if you don’t meet every deadline; recognize when what you’ve done is good enough

Case study #1: Create a detailed strategy and enlist support

Mindy Hall, a management consultant based outside of Philadelphia, knew she had a book in her. In fact, she wrote a manuscript for a leadership book back in 2007, but lost it because of a computer malfunction. “After that happened, I thought it wasn’t meant to be,” she recalls. “But over time it just kept gnawing at me.”

At the beginning of 2013, she decided it was finally time. “I psyched myself up to do it,” she says. She started with her calendar. She created an 18-monthlong timeline with deadlines for the research she needed to complete for finishing each chapter. She also included a plan to start a publishing company.

Seeing it in black and white helped her focus. “I wrote it all down so these [tasks and targets] weren’t just running around in my head,” she explains. While she felt confident she could hold herself accountable to specific deadlines, she also shared her timeline with “a close colleague and ally” who kept her on track. He reviewed and edited drafts and offered feedback. “He was in it with me,” she says.

There were also a number of other colleagues who regularly checked in on her progress during the writing process. “It was very helpful to have the support team. They keep you going and tell you ‘you can do it.’”

Some days were stressful. Some days Mindy didn’t have time to work on the book. “My timeline would have been realistic if I wasn’t also running a business full time, but it was aggressive considering I didn’t take time off to do it,” she says. “In hindsight it might’ve been better if I had forced myself to write every day but life didn’t work out that way.”

Still, she published Leading with Intention in October. Her friends and colleagues threw her a book launch party the following month. “No one writes a book on his own,” she says. “If you have the passion and the will do it, you just have to do it… or stop talking about it.”

Case study #2: Break big goals up into small action items

When Susan Hertzberg arrived as president and CEO of Boston Heart Diagnostics in 2010, it was losing money and had fewer than 40 employees. She had several big goals. One, make the heart disease diagnostic company profitable. Two, recruit a topnotch management team. And three, create “an authentic and real” corporate culture.

Susan knew the last one was an elusive goal; but she says she was determined to: “build a company where people show up and focus on what really matters.” Before she even started the job, she shared this goal in a presentation to Boston Heart’s board. It was in the spirit of: “this is what you can expect from me,” she recalls.

Then Susan formulated a plan. Some actions on her to-do list were small — for instance, to role-model the kind of behavior she wanted to see from colleagues. “I treated front-line employees just the same as executives,” she says.

Other items were large. To improve communication and transparency, she instituted monthly employee-wide meetings where she provided status updates on the business. She saved the last 30 minutes of each session for an open Q&A. “I said, ‘I am going to be as real and authentic with you as I hope you will be with me.’”

She also created a set of “ground rules” for all employees. These rules, known as the “compass,” comprise Boston Heart’s mission, values, goals, and top priorities. Every employee signs a copy of the compass once a year. “It’s our contract with one another so that we are aligned.”

Today Boston Heart, which was recently acquired by Eurofins Scientific, is profitable. Susan has grown revenue over 100% CAGR since she took over, and the company has nearly 400 employees. But Susan is perhaps most proud of the strong and positive culture she’s created. Boston Heart has made the Boston Globe’s “Top Places to Work” in Massachusetts list twice: In 2014 in the large companies category, and in 2012 in the medium companies category.

“There’s a lot hugging and high-fives that take place here,” she says. “And the most frequent feedback I get from [outsiders] is about the culture of the company. You can feel it.”

[image error]

December 26, 2014

Delivering Higher Value Care Means Spending More Time with Patients

“I would have written a shorter letter but did not have the time,” Blaise Pascal, the 17th century French mathematician and philosopher, once apologized. Unfortunately, the same problem often arises when physicians manage the care of patients with chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart failure, and kidney disease. If they had more time (and in some cases, motivational skills), they could better persuade patients to make the sacrifices and hard choices to change their lifestyles and to follow the recommended treatment plan.

Pressuring physicians to maximize the number of patients they see and minimizing the time they spend with each is one of five counterproductive mistakes that health care providers often make in trying to reduce costs — the subject of a recent article in the Harvard Business Review.

Overworked physicians rarely have the time for these difficult conversations, especially when they are restricted to 20- to 30-minute appointments, with much of the front end spent updating a patient’s medical record. When physicians spend an inadequate amount of time with their patients, the patients may not fully understand the importance of complying with all aspects of their recommended treatments, which eventually leads to deteriorating health and higher treatment costs. Approximately 50% of patients with chronic conditions do not take their medications as prescribed.

To illustrate the problem, consider our research on the cost of treating patients when their kidneys begin to lose their ability to filter blood. Should the kidneys of a patient with such a chronic disease completely fail when a transplant is not immediately available, the person needs dialysis several times a week to filter and clean the blood. How the patient starts on dialysis has enormous health and cost implications.

The vast majority of patients should do peritoneal dialysis at home or start with hemodialysis at a dialysis center. Both approaches require a vascular surgeon to create a fistula or a graft to connect an artery and a vein in the forearm. The surgery must be performed well before dialysis starts since a fistula can take about three months and a graft several weeks to “mature,” or be ready to be used for dialysis. (The alternatives are having either a preemptive kidney transplant or a peritoneal dialysis catheter placed, which also require advance planning.) If dialysis is required and a matured graft or fistula is not available, the patient must start with a catheter inserted into a vein in the neck or chest, a process that leads to a much higher risk of infection, blood clotting, and death.

Despite the large health benefits from an optimal dialysis start, more than 50% of patients nationwide begin dialysis via a catheter. Some of these occur because primary care physicians wait too long to refer their patients to nephrologists. Once referred, many patients are in denial that they will need dialysis or that they will need it as soon as actually occurs. Such patients may not adequately prepare for this eventuality despite a timely recommendation by their nephrologist.

To understand these issues better, we formed a project team to study patients that started on dialysis in 2011 and 2012. It analyzed historical data of 167 patients insured by Kaiser Permanente in the Georgia Region, and used time-driven activity-based costing to assess the costs of care received one year prior to the start of dialysis and also the charges incurred for one year after starting dialysis. We learned that health complications in the year following a sub-optimal start of dialysis led to nearly $20,000 in extra treatment costs per patient.

Interestingly, the patients in our study who started on dialysis with a fistula or graft largely had the same breadth of nephrology care — number of nurse visits, nephrologist phone calls, care manager coordination, classes, and initial consults — during the one year prior to the commencement of dialysis as those who started sub-optimally with a catheter. Even including the extra cost of the vascular surgery, the costs of treating the two sets of patients before dialysis began were about the same.

A few differences did exist between the two sets of patients, likely reflecting the better compliance of patients that started dialysis optimally. Patients with an optimal start received, on average, one more follow-up visit (5 vs. 4) with the nephrologist. Patients who started optimally were also somewhat more likely to have attended a class to learn about the options for starting on dialysis and were more likely to have attended the class farther ahead of the start of dialysis.

Dr. Nirvan Mukerji, a nephrologist and a coauthor of this article, believes that he could significantly increase the percentage starting optimally if he could spend an additional 30 minutes with each patient, counseling them on how to best prepare for dialysis as their kidney disease progresses. While his full schedule had previously prevented him from spending that additional time, he is now testing the use of extended office visits for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease as well as alternative options, such as having patients already on dialysis make presentations with him at the education class. We estimated that the incremental cost for the extended meeting or the educational class presentation would be under $200, a small price to pay to avoid the health risks and $20,000 in higher treatment costs that typically occur in the first year after a patient starts dialysis sub-optimally.

There are many other examples of how primary care doctors treating chronic diseases, such as diabetes and congestive heart failure, could offer better advice and achieve better treatment compliance if they had more time to spend with their patients. The costs of such extra time would be repaid many times over, often by orders of magnitude, through fewer future complications. Attempting to improve a physician’s productivity by placing arbitrary limits on length of appointments or setting high targets for the numbers of patients that he or she should see each day lowers costs at the front end of a care cycle. But they incur much higher costs later in the cycle when preventable complications are treated in emergency rooms and intensive care units.

[image error]

Before a Merger, Consider Company Cultures Along with Financials

A normal acquisition process seeks to ensure something basic: a strategic rationale for a deal, supported by a thoughtful selection process, with known risks identified by a short, intense due diligence. But what isn’t practiced, and too often ignored, is the process of asking: “What are the likely challenges we will face as we integrate these two complex companies over the next 1-2 years?”

My experience, after being involved in considerable numbers of such transactions over the past decade, is that in the majority of cases little due diligence is done beyond the financials to investigate the challenges of having two organizations become one. Management is usually shocked to find the degree of differences that exist between their two, soon to be merged, organizations — and too few actively consider these integration challenges before the deal.

What this requires is doing some integration due diligence as part of the M&A process. You can define this type of due diligence with a few key steps:

Assessing the institutional strengths of the acquired company and comparing and contrasting these to the acquiring company to map where there are welcomed overlaps and where there are redundancies.

Understanding the cultural dynamics of the acquired organization, including how they operate, the manner in which they develop their talent, how are they motivated to succeed, and their executive management decision making style.

Doing a stakeholder analysis to understand the additional challenges from political, regulatory, union, and community sources to be expected in the wake of a merger.

While this may sound like common sense, the reasons for ignoring this due diligence step are numerous. CEOs often fear that such analyses require involving too many people, when they have an understandable desire to complete deal negotiations with only a very few trusted lieutenants and advisors involved — and to conduct them in secrecy so as not to alert external markets. Investment bankers resist having to consider integration challenges lest the prospects for a deal be undermined by the realization of the all too numerous challenges that lie beyond their valuation analyses.

Plus, unlike financial due diligence, which can be done through data rooms and shared financials, integration due diligence requires an examination of another’s institutional capabilities, operating cultures, and management talent — all of which are difficult and time consuming to investigate when in the midst of an intense deal negotiation.

The result of this lack of due diligence is played out all too publicly when deals suddenly fall apart. For example, in 2014, mining giants Barrick and Newmont had to unwind their planned transaction after only nine months due to what published reports stated were “clashes over leadership and governance.” Barrick also claimed that the Newmont wanted to “renegotiate foundational organizational elements of the deal.” It was reported that among the causes of the breakup were disagreements about headquarters location, management roles, and other strategic and structural disagreements.

Publicis and Omincom had to unwind their $35 plus billion transaction after they were unable to agree on who would run the combined organization and whose operating strategy would be adopted in a newly merged agency. Now both agencies have to go back their suite of clients and explain why the value of the merger they had been so recently touting wasn’t needed any longer.

Office Depot and OfficeMax announced their intended merger deal without an agreement of , without an agreement on retail brand strategy, and without a chosen corporate headquarters location.

Each of these deals might have greater potential for success with due diligence, before the deal, on the post-merger integration challenges. This kind of due diligence, even if CEOs can get past all the reasons above why not to do it, is hard and unglamorous work: It requires CEOs to look beyond the financials and the strategic rationale and see the stark challenges the integration will require.

Such a cultural due diligence can be done by talking to past members of the target organization, interviewing common suppliers, customers, industry observers, and analysts. It is an “outside-in” analysis that can be undertaken in parallel to all the financial negotiations.

Those who conduct integration due diligences have two major advantages. First, they can build on their knowledge of their own strengths as the acquiring entity. Knowing these strengths means the acquirer can better focus their integration planning, adding only at the margin from the acquired entity into those areas of known strengths. In turn, this means one can focus the integration activities on areas of their weakness. Acquiring management will know at the outset what they need to receive from the acquired entity to strengthen and build a more collective competitive operation.

Second, the whole integration plan is more easily designed, easier to execute, and can be implemented at a faster pace. It’s easier to make decisions about retaining crucial staff, forming the new leadership structure, making changes to management systems, and segregating the integration from the base business to protect revenues during this vulnerable period. CEOs and their senior teams can be more confident and more directive in their communications after the deal announcement right up to legal close.

A prerequisite for any transaction is financial due diligence. But boards and CEOs need to make the integration due diligence as much of a core part of their pre-deal effort. For those that do, the benefit is faster paced, more focused integration planning efforts. Those that don’t risk adding to the enormous probability of failure that already surround such transactions.

[image error]

The Rise of the Not-So-Experienced CEO

When looking to hire a new CEO, corporate boards of directors are increasingly bypassing C-level executives and appointing less seasoned leaders.

They are still looking for chiefs with the traditional attributes of intelligence, integrity, and stamina—traits that have defined great executives for decades. But boards are now also seeking CEOs who understand signals in today’s unpredictable environment and are comfortable acting on them—abilities that directors hope will more than offset candidates’ relative inexperience. All too often, C-level executives are overly focused on internal issues and opt to invest in familiar opportunities rather than taking bold risks.

My colleagues and I have observed the “leapfrog” phenomenon both in our client work and through research. We have reviewed hundreds of corporate announcements and websites, interviewed numerous leadership experts, and conducted an analysis of CEO changes and successions over the past five years at S&P 500 and Global 100 companies. Through this effort, we have observed certain characteristics of this emerging trend.

The phenomenon of fast-track CEO succession appears to be most prominent in the retail, technology, media, and telecommunications sectors—all of which are particularly affected by disruptive business models and new competitors. Some recent CEO appointments in these industries include Yahoo!’s Marissa Mayer, Google’s Larry Page, Burger King’s Daniel Schwartz, Microsoft’s Satya Nadella, PetSmart’s David Lenhardt, and GameStop’s J. Paul Raines.

Many of these CEOs were appointed in their thirties and forties, but accelerated promotion, not age, is what defines a leapfrog leader. General Motors’ Mary Barra and Aetna’s Mark Bertolini, for example, were in their fifties when they became CEOs—but they still experienced a faster path to the top spot than the typical succession timeline of their companies.

Boards are reaching deeper into the companies they oversee to find executives who embrace disruptive technologies and digital media; have a proven record of innovation; are confident global citizens, able to operate in developed, emerging, and frontier markets and lead across diverse cultures; have an acute understanding of shifting demographics in their customer base; and have adaptive leadership traits, such as exceptional curiosity, open-mindedness, and the courage to act.

These attributes are some of the characteristics of a leapfrog leader. Attuned to the times, he or she has a stronger chance to uncover and release a company’s latent potential. A leapfrog leader will likely face stiff opposition in the form of vested interests and traditional practices. But he or she understands the company’s cultural norms sufficiently to ignore some of them without disrupting business continuity.

Although leapfrog CEO appointments come about for various reasons, when considered together, these successions seem to fit into one of two broad scenarios.

In the first, a corporate board persuades a high-performing and dependable CEO to stay longer than planned at the helm to keep a steady hand on the tiller, maintain progress, or weather an upcoming storm. When the CEO finally retires, however, business conditions are even more complex and the environment is even more uncertain. Believing that the company needs a change of course and a new kind of leader—one with more relevant experience and a more future-oriented perspective—the board passes over senior executives, who have “aged out” of consideration, and chooses a less seasoned leader.

In the second scenario, a planned CEO departure occurs during a time of uncertainty. The company is anticipating disruptive or disorienting forces, such as unfamiliar regulatory pressures, industry consolidation, complex emerging technologies, or changing consumer behavior. In response, the board searches for a leader who understands these dynamics. Given that senior leaders often share the same worldview as the departing CEO and could prove to be out of touch with the changes sweeping through the industry, the board looks to the third level of management.

In short, in one set of circumstances, the incumbent CEO remains in place long enough that executives in the next level may not have the forward-looking perspective needed; in the other, the succession plan happens to kick in at a critical time when the company needs leadership that has firsthand, on-the-ground experience with fast-moving change in the industry or technology.

It is still too early to tell whether instances of fast-track CEO succession are a coincidence, a fad, or a full-blown trend. But one thing is clear: boards and companies can take a number of actions to help new CEOs succeed and expand the field of internal CEO candidates.

Boards must remain engaged during the grooming and transition of new leaders. When considering the promotion of a relatively junior executive to the position of CEO, boards can have the candidate tested and prepared by ensuring an appointment as president, CFO, or COO. Placing the candidate on a corporate board will help him or her gain experience interacting with directors. And having the candidate sponsor a major enterprise initiative will give him or her the opportunity to mobilize other leaders across the organization.

The board can also continue to ensure the success of leapfrog leaders after their ascension to the CEO role. Keeping the roles of CEO and chair separate for the first year could allow a new CEO to get traction at the company while the chair manages the investment community. And establishing a clear transition process for assuming the CEO role and a first-year plan will also help the new chief get off on the right foot.

Some senior leaders may be disappointed that they were passed over for the top spot in favor of a more junior candidate. The company should anticipate some departures and make contingency plans to appoint replacements and reach out to stakeholders. At the same time, the company should try to encourage bypassed executives by expanding their responsibilities and offering them opportunities to diversify their experience.

To expand the field of internal CEO candidates, boards should revisit and revise the company’s succession processes, reconsidering the capabilities required at the top—for senior leaders as well as the CEO—and identifying promising candidates early in their careers. Moving some senior leaders from their positions to give younger candidates opportunities to gain the necessary experience may be prudent.

Most important, fast-tracking a leader and appointing him or her CEO should always be made for the right reasons. A leapfrog candidate should never be the “least worst” option. The more planning that goes into developing candidates for various future leadership scenarios, the more options a board will have for choosing a successor that best suits its strategic agenda. Forward-looking companies identify front-runners early on and groom them for success. A fast-track CEO succession should be the product of a deliberate strategy, not of desperation.

The author would like to acknowledge the contribution of BCG colleagues Gerry Hansell, Kaye Foster, and David Baron, who assisted in the development of these ideas.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers