Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1332

January 9, 2015

Investors Fawning over Uber Should Recall AOL’s Stumbles

January 10 marks the 15th anniversary of the announcement of a merger that most observers agree was just about the worst in history: the fusing of the start-up AOL and the venerable Time Warner. This year also marks AOL’s 30th birthday as a company. Finally, it’s also the 30th anniversary of a pivotal piece of research that we ruefully keep re-discovering with each entrepreneurial boom that comes along.

At the time the merger negotiations began, AOL was enjoying intense investor interest, to the point where a company that was only 15 years old and had been public for only 8 years had a higher market capitalization than media powerhouse Time Warner. Many thought the world had truly been turned upside down when a company that flooded mailboxes with CDs and infuriated customers with frequent busy signals could acquire Time Warner. Ah, the magic of the marketplace.

The merger was originally heralded as “transformative” – the first actualization of the long-promised fusion of content and delivery channel. Time Warner would instantly solve its concerns about being relevant in an online age, and gain access to tens of millions of AOL customers. AOL, for its part, could leverage the beloved Time Warner brands across its properties and make its dial-up subscription services more valuable — even as the threat of always-on broadband was making itself known. Other companies wondered whether they should pursue mergers of their own, thinking that perhaps this deal was going to be the wave of the future.

Unfortunately, for that strategy to work, the people in the merged company would have to work across silos, cooperate, and otherwise play nicely together. And they hated each other. What was simple friction and cultural distaste in the beginning hardened into visceral enmity after the dot-com crash led to the deflation of the company’s market cap (from $226 billion to about $20 billion) and the company had to write-down nearly $99 billion of goodwill in 2002, a number that even hardened Wall Street Journal reporters termed “astonishing.”

Insight Center

Making Money with Digital Business Models

Sponsored by Accenture

What successful companies are doing right

But today we’ve learned our lesson – there’s no way we’ll support the wacky valuations that those smoking-something dot-com-boom investors did, right? I’m not so sure. Riddle me this: Uber, the car sharing service, was recently valued at $41 billion. As critics have pointed out, the entire taxi and limousine industry in the US generates $11 billion in revenue per year.

Yes, one might argue, Uber is “transformative” (there’s that word again) because it will dramatically increase the number of people who can afford to hire a driver rather than drive themselves or own a car. But this assumes that Uber can somehow lock in the lion’s share of that business. With few barriers to entry, there’s no reason many more players wouldn’t jump into the business, including existing taxi drivers. Unlike Google, Facebook, or Twitter, which have strong network effects (meaning that the more people that use them, the more valuable they become), Uber really doesn’t, beyond its ability to maintain adequate driver coverage. Further, as it deepens its reach into more of the population, its troubles with safety, privacy, driver vetting, and even criminal behavior are likely to increase as well. $41 billion looks pretty rich to me.

Back in 1985, Bill Sahlman and Howard Stevenson of Harvard wrote a brilliant case and article they called “Capital Market Myopia”. The phenomenon that drew their attention was that participants in capital markets were ignoring the collective implications of their individual investment decisions. They were simply unwilling to back away from a market all the experts agreed was going to be tremendously exciting.

Their original study was of new entrants into the Winchester disk drive industry, a sector every bit as hot and exciting back then as start-ups like Uber are today. Between 1977 and 1984, venture capitalists invested over $400 million in 43 manufacturers of the drives. Some (12) of the firms had an IPO, and collectively enjoyed valuation that at its peak was $5.4 Billion. At the peak of the frenzy, some 70 companies participated in this space. It didn’t end well. The public companies’ valuations dropped to $1.4 billion in 1984, and investors lost millions in the ensuing shakeout.

So what does an old bubble in now-dusty disk drives have to teach us about investments today? Well, for starters, Silicon Valley is once again awash in capital, which in turn means companies are burning through that capital quickly, which in turn increases the likelihood of irrational investing. They are also amidst the frenzy of a winner-take-all mentality: the theory of the case is that the firm that gains the biggest market share first will ultimately triumph in its sector. It’s set up perfectly to induce what is sometimes called increasing commitment to a failing course of action – if you stop spending, you know what you’ll lose, while if you keep investing, the dream of a big return can be kept alive. But, people, we have been there before – remember WebVan, Value America, Boo.com, Pets.com, and all the rest?

So here’s a little statistic to ponder: According to the Wall Street Journal, there are now 48 private companies in the US valued at over $1 billion. During the peak of the dot-com boom, there were only 10 companies valued over $1 billion.

But all 48 of them are transformative, right?

[image error]

Why Europe Tops 2015’s List of Global Risks

Russia and Ukraine. ISIS. Iran and Syria. The Sony hack by North Korea. In 2014, global political volatility reached an intensity not seen since the end of the Cold War. What are the biggest political and economic risks heading into the year ahead? Taken together, what do they mean for global businesses?

For an expert perspective on these questions and more, I talked to Ian Bremmer, president of Eurasia Group. The firm has just published its annual assessment of Top Risks. An edited version of our conversation is below.

Europe is at the top of your risk list for 2015. Why? That seems somewhat surprising given that the Euro economic crisis seems to have tailed off, or at least plateaued.

You notice it’s the politics of Europe, not the economics of Europe. Clearly the economics of Europe are better than they were in the teeth of the Eurozone crisis. I hate to say it, but that’s actually part of the problem. In the United States we complain about governance from Washington constantly; and in Europe they complain even more about Berlin. But the fact is that when there’s a big economic crisis, we are capable of responding. When Lehman fell apart, the U.S. put hundreds of billions of dollars together almost overnight. And the Germans were capable of responding with the European governments immediately when there was a true rubber-hits-the-road moment, like the Greek exit or Cyprus.

But they don’t face that right now. So the economics are better, but the politics are worse – and they’re worse on every front. Internally, you’ve got the growth of populist movements within European countries. The potential that Syriza actually wins a snap election in Greece. You look at Podemos in Spain, with elections coming up in 2015. The rise of UKIP in Britain and how that forces Cameron to talk internally about Europe, about Germany, about immigration. The Front National in France. Combine this with fairly anemic growth, no opportunities for Europe’s youth, visceral anti-immigrant sentiment, growing Islamist radicalization – all this is making it much harder for these countries to govern. And it’s likely to start returning governments that are much more alienated from Berlin and from Brussels.

At the same time, you have extremely challenging geopolitics, specifically around ISIS and terrorism, and Russia. Look at the horrific attack this week in Paris. I think we’re more likely to see a kind of metastasis of the ISIS brand and ethos causing one-off attacks in major capital cities in Europe than in the U.S. or in Australia. And certainly Europeans are alarmed about Russia, which is absolutely on a road to ruin: low oil prices, increasing concern about default, about expansion of the fight in Ukraine, about near misses between Russian military aircraft and European commercial aircraft. The geopolitical environment is much worse for Europe now than it has been historically. And because Europe is the world’s largest single common market, all of this redounds very negatively to the global scene.

Russia is your number two risk. Obviously, Russia’s offensive actions in Ukraine last year shocked the world. Should the U.S. have responded differently? And what’s the continuing risk in dealing with Putin?

We could have done a lot of things differently. The U.S. and NATO have spent 80% of our effort in punishing the Russians, and 20% in supporting the Ukrainians. That is exactly the wrong balance. It should have been 80/20 in the other direction. We have pushed the Russians to the point that Putin believes we’re trying to undermine him personally and that our goal is regime change. The U.S. view is that we just want to punish him, enough so that he changes his behavior. But he’s not going to change his behavior. He’s only getting more aggressive. And he does control his country. I don’t know how far he’s going to go, but I know that we’ve seen major cyberattacks against American banks, and against the White House that have come from Russia.

Think about the Sony attack. What are we going to do if a major American bank suddenly has all of their dirty laundry exposed and it turns out it came from the Russian government? What happens if next time it’s not a near-miss, but a direct hit of a commercial airliner by a Russian plane that turns its transponder off?

And look at instability in the Baltics. We have pushed the Russians to the point that people are concerned about a default. That doesn’t necessarily mean there will be a default, but it absolutely leads to more capital flight from Russia and the kind of market sentiment that can drive a panic. Combine this with the fact that Russia’s economy is deteriorating quickly, that Putin’s popularity is unlikely to stay at 85% over the course of next year, and that he’s not going to give up on Ukraine. Also, low oil prices – these are generally an enormous good for the world, helpful for global consumers. But major oil producers get hit and Russia’s a big one.

All of these things make Putin and Russia the biggest, most powerful wildcard in the entire world, with the potential to cause a lot of damage to the global economy.

The “weaponization of finance” is also high on your list. Are you talking about the usual economic and trade policy kind of hardball?

A lot of people are talking about how the United States is becoming more isolationist, that we should lead from behind, and that the U.S. isn’t as interested in doing engaged foreign policy. I don’t agree with any of that. I think the U.S. is still very, very assertive around the world in ensuring that its interests are met.

But what’s changed is that the U.S. is becoming much more unilateral. Less focused on collective security and NATO, more focused on drones and surveillance and the NSA. And actually, the biggest projection of American unilateral power is on the economics side. In terms of America being a superpower, U.S. dominance of the global financial system is much greater than if you look at America’s role with regard to nuclear weapons or conventional military forces or even surveillance. And America’s willingness to weaponize finance has grown substantially as a consequence.

When it comes to fighting ISIS, for example, militarily we don’t want boots on the ground, we’re not doing that many bombing runs, we don’t want to kill civilians. But America’s willingness to use the dollar, to use the banking and financial system to squeeze countries that are not doing what the U.S. wants with regard to rogue regimes and rogue actors, that’s getting much more severe.

And what’s interesting is that while the U.S. is the country imposing sanctions, it’s our allies that are actually bearing the biggest cost. This is particularly true for Europe, which has the world’s largest banking system, but whose companies are significantly more exposed to all of these rogues – Russia, Iran, South Sudan. This leads to a growing transatlantic rift, because the Europeans become increasingly frustrated with American unilateralism that the Europeans pay for.

Of course, when the Obama administration imposes sanctions, the intention is to support democracy and to combat terror, in the service of the American national interest and to promote global security. We’re sanctioning bad guys, so who wouldn’t want that? But the point is, a lot of countries are on the wrong side of that, financially.

Your number seven risk, on the rise of business sectors that are strategic to governments, seems to confirm the thesis of your 2014 HBR article, in which you described a world of “guarded globalization,” with emerging markets wary of opening more industries to multinational companies, and an overall economic dynamic that is more selective and nationalistic. Do you see this dynamic continuing?

Yes, it’s going to continue. There are a few things to look at here. First, the U.S. is going to start hiking rates and that’s clearly a challenge for emerging markets. Broadly, China is slowing down, and intentionally so, and that will be a challenge for other emerging markets. So there are definitely some headwinds that make it more difficult if you’re a country like Brazil or Indonesia just opening up and being more competitive. Whether it is populist policy from governments that want to maintain approval, or more hostile sentiment toward foreign companies as a result of the leadership’s geopolitical leanings, many countries will shift more toward nationalism in the marketplace. All of those trends can come hand in hand with deeper government intervention into more sectors of the economy.

Russia is the extreme example on this front. Talk about strategic sectors – McDonald’s has had stores shut by the Russian government because they’re an American company, and perceived as such. The Russians are putting sanctions on Western firms precisely because of politics and because of nationalism, and I think we’ll see more of that. We see Russia orienting itself overwhelmingly toward emerging markets and towards China. This eventually leads to a breakdown of U.S.-led global standards as the Russians form their own ratings agency with the Chinese; their own financial transaction management organization with the Chinese; their own Internet standards. Russia is developing their own Wikipedia. All of this pushes against U.S.-led globalization-slash-Americanization.

China is different, but just as powerful as an example. They’re engaged in serious economic reform at home and it has been very successful. But the Chinese government has no interest in liberalizing their political system. They do not want to create a free market private sector-based economy. They’re still very much state capitalists. As Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) continue to gain more influence on the international stage, China will be able to create and enforce rule sets which reflect their own norms and priorities and values.

That is what the creation of the BRICS Bank was all about. Also the Chinese and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and the China Overland and Maritime Silk Route programs. All of these institutions are oriented bilaterally between China and other countries in their region, transacting billions and billions of dollars and at the same time making these countries more accountable and leverageable according to Chinese economic and commercial preferences. This is a huge driver towards guarded globalization.

That does start to sound something like a new Cold War. Are we already in it, or not quite yet?

We’re headed in that direction. If you’re a Western multinational company you may have thought, historically, well, OK, I know China’s getting bigger and they may have challenges, but eventually they’ll get wealthy, and then we can work with them. But what if it’s not just China? What if it’s China and Russia? What if it’s China, Russia, and Russia’s neighborhood, and then some of China’s neighborhood? And what if that starts to grow? The potential for this to continue and develop into a more fragmented system where regional powers have enormous sway – from a security perspective, a political perspective, and an economic perspective – over their own peripheries certainly seems closer to reality as a consequence of what’s happened with Russia in recent weeks and months, with the collapse of the ruble, dropping oil prices and continuing tensions around Ukraine.

What does business leadership look like in this changed context? In a recent piece, you said: “We now live in a world where no single power or alliance of powers is willing and able to provide global leadership. Call it geopolitical creative destruction.” How should individual leaders be thinking and acting differently in such a world?

In an environment of geopolitical creative destruction, you will see much more global volatility in the markets. As a result, the quality of returns on investment and the quality of global growth is actually going down. This means that in order to achieve the same amount of growth as in the past, you will have to take on more risk.

For most multinational leaders, that means they need to focus a little less on growth and a little more on resilience and anti-fragility. This is hard to do, particularly for American CEOs because they’re not there for long, with a typical stint of four years or so. They’re focused on increasing shareholder value and getting as much profitability as possible, and not as much on sustainability. I know that’s become a great buzzword, but I’m not talking about climate – I mean sustainability of the corporate models themselves. That’s going to be a big challenge for leaders. It’s easier, perhaps, for a Japanese CEO to think in those terms.

[image error]

How to Handle Difficult Conversations at Work

Difficult conversations — whether you’re telling a client the project is delayed or presiding over an unenthusiastic performance review — are an inevitable part of management. How should you prepare for this kind of discussion? How do you find the right words in the moment? And, how can you manage the exchange so that it goes as smoothly as possible?

What the Experts Say

“We’ve all had bad experiences with these kind of conversations in the past,” says Holly Weeks, the author of Failure to Communicate. Perhaps your boss lashed out at you during a heated discussion; or your direct report started to cry during a performance review; maybe your client hung up the phone on you. As a result, we tend to avoid them. But that’s not the right answer. After all, tough conversations “are not black swans,” says Jean-Francois Manzoni, professor of human resources and organizational development at INSEAD. The key is to learn how to handle them in a way that produces “a better outcome: less pain for you, and less pain for the person you’re talking to,” he says. Here’s how to get what you need from these hard conversations — while also keeping your relationships intact.

Change your mindset

If you’re gearing up for a conversation you’ve labeled “difficult,” you’re more likely to feel nervous and upset about it beforehand. Instead, try “framing it in a positive, less binary” way, suggests Manzoni. For instance, you’re not giving negative performance feedback; you’re having a constructive conversation about development. You’re not telling your boss: no; you’re offering up an alternate solution. “A difficult conversation tends to go best when you think about it as a just a normal conversation,” says Weeks.

Breathe

“The more calm and centered you are, the better you are at handling difficult conversations,” says Manzoni. He recommends: “taking regular breaks” throughout the day to practice “mindful breathing.” This helps you “refocus” and “gives you capacity to absorb any blows” that come your way. This technique also works well in the moment. If, for example, a colleague comes to you with an issue that might lead to a hard conversation, excuse yourself —get a cup of coffee or take a brief stroll around the office — and collect your thoughts.

Plan but don’t script

It can help to plan what you want to say by jotting down notes and key points before your conversation. Drafting a script, however, is a waste of time. “It’s very unlikely that it will go according to your plan,” says Weeks. Your counterpart doesn’t know “his lines,” so when he “goes off script, you have no forward motion” and the exchange “becomes weirdly artificial.” Your strategy for the conversation should be “flexible” and contain “a repertoire of possible responses,” says Weeks. Your language should be “simple, clear, direct, and neutral,” she adds.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Office Politics

Communication Book

Karen Dillon

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Acknowledge your counterpart’s perspective

Don’t go into a difficult conversation with a my-way-or-the-highway attitude. Before you broach the topic, Weeks recommends asking yourself two questions: “What is the problem? And, what does the other person think is the problem?” If you aren’t sure of the other person’s viewpoint, “acknowledge that you don’t know and ask,” she says. Show your counterpart “that you care,” says Manzoni. “Express your interest in understanding how the other person feels,” and “take time to process the other person’s words and tone,” he adds. Once you hear it, look for overlap between your point of view and your counterpart’s.

Be compassionate

“Experience tells us that these kinds of conversations often lead to [strained] working relationships, which can be painful,” says Manzoni. It’s wise, therefore, to come at sensitive topics from a place of empathy. Be considerate; be compassionate. “It might not necessarily be pleasant, but you can manage to deliver difficult news in a courageous, honest, fair way.” At the same time, “do not emote,” says Weeks. The worst thing you can do “is to ask your counterpart to have sympathy for you,” she says. Don’t say things like, ‘I feel so bad about saying this,’ or ‘This is really hard for me to do,’” she says. “Don’t play the victim.”

Slow down and listen

To keep tensions from blazing, Manzoni recommends trying to “slow the pace” of the conversation. Slowing your cadence and pausing before responding to the other person “gives you a chance to find the right words” and tends to “defuse negative emotion” from your counterpart, he says. “If you listen to what the other person is saying, you’re more likely to address the right issues and the conversation always ends up being better,” he says. Make sure your actions reinforce your words, adds Weeks. “Saying, ‘I hear you,’ as you’re fiddling with your smartphone is insulting.”

Give something back

If you’re embarking on a conversation that will “put the other person in a difficult spot or take something away something from them,” ask yourself: “Is there something I can give back?” says Weeks. If, for instance, you’re laying off someone you’ve worked with for a long time, “You could say, ‘I have written what I think is a strong recommendation for you; would you like to see it?’” If you need to tell your boss that you can’t take on a particular assignment, suggest a viable alternative. “Be constructive,” says Manzoni. Nobody wants problems.” Proposing options “helps the other person see a way out, and it also signals respect.”

Reflect and learn

After a difficult conversation, it’s worthwhile to “reflect ex post” and consider what went well and what didn’t, says Manzoni. “Think about why you had certain reactions, and what you might have said differently.” Weeks also recommends observing how others successfully cope with these situations and emulating their tactics. “Learn how to disarm yourself by imitating what you see,” she says. “Handling a difficult conversation well is not just a skill, it is an act of courage.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Take regular breaks during the day; the more calm and centered you are, the better you are at handling tough conversations when they arise

Slow down the pace of the conversation — it helps you find the right words and it signals to your counterpart that you’re listening

Find ways to be constructive by suggesting other solutions or alternatives

Don’t:

Label the news you need to deliver as a “difficult conversation” in your mind; instead frame the discussion in a positive or neutral light

Bother writing a script for how you want the discussion to go; jot down notes if it helps, but be open and flexible

Ignore the other person’s point of view — ask your counterpart how he sees the problem and then look for overlaps between your perspectives

Case Study #1: Be clear, direct, and unemotional

Tabatha Turman, the founder and CEO of Integrated Finance and Accounting Solutions, a financial firm with both government and private sector clients, knew she had a problem with a certain employee. “He was a nice person and he worked long hours but his productivity was an issue,” she says. “He wasn’t right for the position he was in.”

She and her team tried a number of interventions — including having him work with a professional coach — but after six months, she needed to take action. “We kept kicking the can down the road, but I realized I was going to have to be the bad guy.” She was going to have to lay him off.

Tabatha dreaded delivering the news. “I really liked this person,” she says. “We’re a small company and all really close—you know about people’s families and you hear about their vacations. At the same time, everybody plays a position on the team and one weak link can bring it down.”

To steel herself for the conversation, Tabatha called on her 20 years of experience as an officer in the army. “I grew up in a military environment where there’s no bluff,” she says. “When you’re at work, you’re at work. You need to be strong for the people around you and take your feelings out of it.”

Her words were simple. She told the employee that he was “not a good fit.” She explained that the company would keep him on until the end of the month and then provided details about the severance package. Tabatha says that while the employee “wasn’t happy” he took the lay-off “like a trooper.”

Even though she didn’t show her emotion during the meeting, Tabatha still says the conversation “lingers” in her mind today. “I still feel badly that it didn’t work out, but it wasn’t right,” she says. “We had to move on.”

Case Study #2: Put yourself in the right frame of mind and show empathy

As Chief Personnel Officer at Booz Allen Hamilton, Betty Thompson, is accustomed to having hard conversations. Recently, for instance, she had to tell a successful, longtime employee that his position was being eliminated.

“Over time, his role had become less relevant to the organization,” she says. “There were also proximity issues — his team was on one side of the country but he was on the other side. It just wasn’t going to work anymore.”

Betty decided that the message would be best delivered not in one conversation, but in a series of multiple discussions over a couple of months. “I didn’t want to rush things,” she says. “It was a process.”

Before even broaching the subject with the employee, she reminded herself of her good intentions. “You need to have the right energy going into something like this. If you’re coming from a place of frustration—which can happen, we’re only human — it will not be a constructive conversation. You have to think: ‘What’s the best way for this person to hear the message?’”

Her first step was sitting down with the employee to ask how he thought things were going. “I wanted to know what frustrations he was having,” she says. “I wanted him to look in the mirror, not poke him in the eye.”

After he spoke, she offered her own perspective on the problem. He was initially defensive, but by the second time they spoke, he had come around and agreed there was a problem.

By their final conversation, the employee had decided to leave the company. They had a great talk and even ended the conversation with a hug. “He knew that I cared,” she says.

[image error]

Fixing the Euro Zone and Reducing Inequality, Without Fleecing the Rich

What do deflation and rising inequality have in common? The answer is that we have too much of both and they threaten the nascent global recovery. The US economy is in cyclical full-steam-ahead mode, but it’s mainly benefitting the owners of financial assets – wage growth is missing. In Europe, deflation and rising inequality are combining to make a bad situation much worse.

Prior to the global financial crisis, deflation looked like a uniquely Japanese problem. But today this malaise is most acute in the euro zone, where demand has been depressed due to counterproductive fiscal policies.

Increasing inequality of income and wealth has occurred across the developed world for the past 30 years, with the majority of the gains from technology, globalization and deregulation accruing to a small minority in each country. Setting aside the issues of political legitimacy this raises in democracies, high and sustained levels of inequality are bad for long-run growth. This is now accepted as fact by organizations as diverse as the IMF and Standard and Poor’s.

The policy response to the global financial crisis exacerbated and entwined these trends still further. The traditional response to the problem of insufficient demand is government-led infrastructure spending. Yes, no doubt many countries would benefit from better infrastructure, and the current low cost of borrowing for governments suggests that it would be a good time to make such investments. But the recent attempt to launch a major infrastructure program in the euro zone – the so-called “Juncker plan” – illustrates that such proposals are hindered by politics, are rarely timely, and are often insufficient in scale to make a real difference to the larger economy.

In addition, rather than continue their stimulus spending, many economies began to cut back excessively, especially in Europe, which made their economies slump further. With fiscal remedies on the sidelines, monetary policy had to take up the slack. Interest rates of zero meant that central banks took to targeting asset prices – stocks and bonds – to boost spending. But the ownership of financial assets is highly concentrated and the effect was to compound the existing trends of wealth and income inequality, with muted effects on demand.

Both of these reinforcing trends have created a tax revenue problem for governments. Today, the burden of income tax is increasingly being borne by middle and upper-salary households. Those with the lowest incomes have their income supplemented by transfers, often as tax credits, while at the other end of the distribution, many of the super-rich owe their wealth to capital – which is taxed at a lower rate — not salary. With the recovery in Europe failing to materialize and wages in the US stagnant despite the improved economy, tax receipts will continue to fall, which only leads to wider deficits and more demands to cut spending.

In short, the middle is being squeezed, the top doesn’t spend enough, the bottom doesn’t earn enough, and the policy mix is fatally flawed. We need new policies.

The European central bank is close to exhausting conventional approaches – official interest rates are negative, and even large-scale asset purchases are unlikely to significantly increase private sector spending. Encouraging already stretched households and corporates to borrow more, as a way to spur recovery in the midst of deep recession, is both ineffective and negligent. So one solution suggested by a growing number of economists in Europe is for central banks to “helicopter drop” money, and directly finance private sector spending.

Milton Friedman imagined a helicopter flying over a community and dropping dollar bills from the sky. Conveniently, he assumed each household picked up an equal share. To Friedman, it was obvious that this would result in an increase in spending. All the empirical evidence on analogous policies, such as tax rebates, suggests that Friedman was correct: unsurprisingly, if you give people more money, they tend to spend it. They don’t rationally-discount it, save it all, or give up their jobs in the hope of a handout.

How could this work in practice in a modern economy? And wouldn’t it all result in hyperinflation and the end of civilization?

The simplest way to boost demand is to give power to central banks to transfer cash in equal amounts to all households. For example, the European central bank, which by law is prohibited from financing government spending, could simply credit the bank accounts of all tax-paying euro zone citizens.

Such a policy would be cheaper than the alternatives and more effective. Quantitative easing (QE) by the Fed, Bank of England and the Bank of Japan, has involved asset purchases equivalent to more than 20% of GDP. A payment of cash to Eurozone households of 3-5% of GDP would probably suffice to generate a recovery. This policy is also fairer. Each household gets the same amount of money and there is no favoring of borrowers, lenders, or owners of assets. It’s also faster and more direct than infrastructure spending.

What about inflation, or worse still, hyperinflation? These fears are emotional and fade under clear analysis. Any impact on prices would depend on how much spare capacity there is in the economy. Firms in the euro zone are desperate for higher sales; price increases would be corporate suicide in the current, intensely competitive economic environment. For Europe to have an inflation problem, there would need to be a boom first – and nothing could be further from the current reality. Still, to mitigate fears of inflation, we recommend tying the cash drops to a Taylor rule (a nominal interest rate/inflation rate target) and when the economy hits that target, the drops stop.

All central banks should be given this power, even if they do not need to use it immediately. It would provide the Fed and Bank of England with a contingency plan should their economies faced renewed shocks. In Europe it is an immediate remedy to deflation, which if it is not halted, threatens the very unity of Europe.

But even if this works, can we do more to reverse the huge increase in income and wealth inequality that makes recessions deeper and recoveries more fragile?

Substantial benefits of globalization, deregulation, and technology accrue to almost all of us, but the financial rewards appear have gone disproportionately to capital. In the United States, corporate profits as a percent of GDP are close to historic extremes and yet higher corporate investment spending has not materialized. One policy would be to tax the top more, but a better solution would be make sure that all segments of society have significant equity ownership.

One lasting consequence of the global financial crisis is a high global equity risk premium. This risk premium is a measure of the likely excess return of the stock market relative to government bonds. Sine the crisis, investors have had a strong preference for assets which are perceived as low risk, such as government debt. Combined with an expectation that interest rates will stay low for a long time, this creates a world where the cost of borrowing for most developed governments is now negative in real terms. In contrast, global equity markets are priced to deliver something close to historic long-run returns of around 5% in real terms. Even in the United States, where many correctly observe than equity valuations are above their long run averages, equity markets are still priced to beat government bonds by around 4% in real terms. This gap implies that governments have an opportunity to buy equity cheaply on behalf of the population.

We propose that governments should exploit this excess return by funding large sovereign wealth funds housed within central banks (so that politicians can’t get at the funds), financed by issuing government bonds. Alternately, the Fed and other central banks, which have trillions of dollars of “safe” bonds via QE programs, could sell these and buy global equities. Creating sovereign wealth funds along these lines would allow governments to dramatically expand the ownership of equity, without any increases in taxation.

For example, if the US government issued 30% of GDP in bonds and invested the proceeds in an index of global stocks, there would be no immediate impact on the government’s balance sheet. It would have a liability (government bonds) and an asset (equity holdings) of equal value. But over 15 years, the real value of the government bonds will be unchanged, or lower, because after inflation the yield is negative, and the value of the equities is likely to have doubled – the compounding effect of a 5% real return. The wealth created, equivalent to 30% of US GDP, could then be distributed to the poorest 80% of households. This is not alchemy. The government is simply broadening equity ownership by exploiting the shorter time horizons and risk aversion of global investors.

The politics of fiscal policy and the tools of monetary policy are out-of-date and dysfunctional. Modest innovation to address the intertwined problems of deflation and inequality is needed. Financial markets currently provide a unique opportunity for governments to acquire equity on behalf of a majority of the population. If rising job insecurity and lower wage growth is the price we must pay for globalization and technological innovation, let us at least broaden the ownership of equity so we all share the upside.

[image error]

January 8, 2015

Sometimes Cutting R&D Spending Can Yield More Innovation

This may sound as though we’ve got our facts backward, but your company can significantly increase its knowledge output by cutting R&D spending.

It’s all a matter of when you cut your spending, and why.

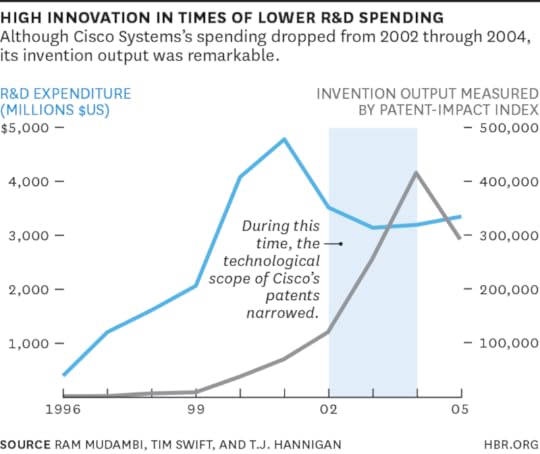

Take Cisco, for example. The company’s R&D expenditures dropped by about $1.5 billion from 2002 through 2004. Drawing on data from the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research, we found that during this period, the company’s patented knowledge output increased significantly.

The chart may appear to show merely that Cisco’s patent filings lagged its R&D spending by three years, but in fact the decline in spending and the rise in patents were part and parcel of a deliberate strategic shift by the company in 2001.

So what was going on? How could a decline in research spending stimulate an outpouring of patents?

What Cisco was doing was shifting its R&D approach from exploration to exploitation. Exploratory R&D, in which researchers cast about for radical new ideas, is expensive and iffy, typically resulting in patents that are relatively few in number but packed with valuable knowledge. Exploitative R&D, in which companies focus on making use of the best ideas they’ve discovered, is less costly and more of a sure thing, often resulting in a vast quantity of incremental and defensive patents built on the foundation of prior exploration. Cisco followed this pattern: In 2001, its patent activity narrowed dramatically from a broad array of technological areas to relatively few.

Over time, many of the best tech companies cycle between exploration and exploitation. Sometimes exploration means creating inventions; sometimes it means acquiring small, inventive companies. But whatever form it takes, exploration in these companies is typically followed by exploitation (a few companies do both simultaneously, but we’ve found that the sequential approach is much more common, probably because trying to do both at once is really difficult).

Exploitation allows companies to monetize their exciting new ideas and thereby relieve some of the stakeholder pressure for short-term earnings. It gives the CEO a breather until the company has to return to exploration to restock its supply of radical ideas.

We’ve found that, in general, companies that move between exploratory and exploitative R&D exhibit superior performance, in comparison with companies that budget R&D expenditure as a fixed percentage of sales, committing neither to exploratory nor exploitative R&D.

Our research shows that Cisco is unusually adept at this sequential ambidexterity, shifting between the two approaches at opportune moments. In fact, we think Cisco is one of the all-time best at this corporate skill.

During exploratory periods, when new opportunities are opening up, Cisco spends generously in search of radical innovations for competitive advantage; once it has identified a good number of them, it shifts to exploitation, which allows the company to cut its R&D budget while producing large numbers of valuable patents, although with narrower scope than during the exploration phase.

Having gone through a period of intense exploration and discovery at the beginning of the 2000s, when the internet was still fairly new, the company changed tack, focusing mainly on exploiting inventions related to the internet’s backbone. It issued numerous upgrades that increased the speed and throughput of its routers and improved the accompanying software platform. Although it expanded into new markets, these moves were based on the company’s existing knowledge: Cisco’s storage-area network products were modified versions of its routers, and even its move into consumer wireless internet relied on mature Cisco technologies.

As of late, Cisco is back into exploratory territory as it leads a push into multimedia conferencing, in large part by acquiring smaller companies. Where will this period of discovery take the company? If the past is prelude, before long we’ll see the company amass a number of valuable ideas related to conferencing, then shift to a lucrative period of exploiting its best ideas.

Cisco’s example demonstrates that corporate vision comes in many flavors. It’s not always just about hiring great minds and giving them the freedom to look for the next big thing. It’s also about knowing when to shift from one mode to another. That requires an understanding of when a set of radical ideas is ripe for monetization and, later, when the returns to incremental R&D are falling, necessitating a return to search mode. Visionary leadership is also about helping the company overcome inertia so that it can shift effectively from one frame of mind to another when the time comes. Few companies pivot easily, but those that do position themselves to ride wave after lucrative wave of exploratory, then exploitative, R&D.

[image error]

Mindfulness Can Literally Change Your Brain

The business world is abuzz with mindfulness. But perhaps you haven’t heard that the hype is backed by hard science. Recent research provides strong evidence that practicing non-judgmental, present-moment awareness (a.k.a. mindfulness) changes the brain, and it does so in ways that anyone working in today’s complex business environment, and certainly every leader, should know about.

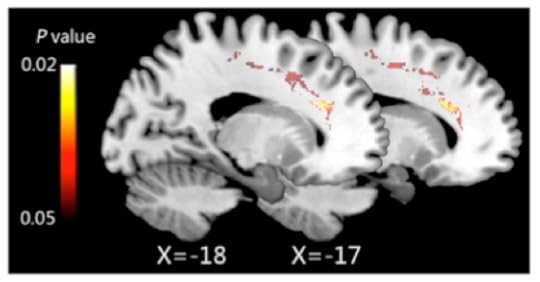

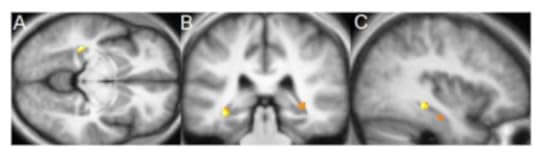

We contributed to this research in 2011 with a study on participants who completed an eight-week mindfulness program. We observed significant increases in the density of their gray matter. In the years since, other neuroscience laboratories from around the world have also investigated ways in which meditation, one key way to practice mindfulness, changes the brain. This year, a team of scientists from the University of British Columbia and the Chemnitz University of Technology were able to pool data from more than 20 studies to determine which areas of the brain are consistently affected. They identified at least eight different regions. Here we will focus on two that we believe to be of particular interest to business professionals.

The first is the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a structure located deep inside the forehead, behind the brain’s frontal lobe. The ACC is associated with self-regulation, meaning the ability to purposefully direct attention and behavior, suppress inappropriate knee-jerk responses, and switch strategies flexibly. People with show impulsivity and unchecked aggression, and those with between this and other brain regions perform poorly on tests of mental flexibility: they hold onto ineffective problem-solving strategies rather than adapting their behavior. Meditators, on the other hand, demonstrate , resisting distractions and making correct answers more often than non-meditators. They also show more activity in the ACC than non-meditators. In addition to self-regulation, the ACC is to support optimal decision-making. Scientists point out that the ACC may be particularly important in the face of uncertain and fast-changing conditions.

(Source: Tang et al.)

(Source: Fox et al.)

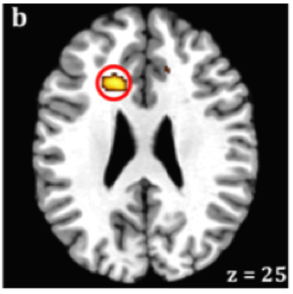

The second brain region we want to highlight is the hippocampus, a region that showed increased amounts of gray matter in the brains of our 2011 mindfulness program participants. This seahorse-shaped area is buried inside the temple on each side of the brain and is part of the limbic system, a set of inner structures associated with emotion and memory. It is covered in receptors for the stress hormone cortisol, and that it can be damaged by chronic stress, contributing to a harmful spiral in the body. Indeed, people with stress-related disorders like and tend to have a smaller hippocampus. All of this points to the importance of this brain area in resilience—another key skill in the current high-demand business world.

(Source: Hölzel et al.)

These findings are just the beginning of the story. Neuroscientists have also shown that practicing mindfulness affects brain areas related to perception, body awareness, pain tolerance, emotion regulation, introspection, complex thinking, and sense of self. While more research is needed to document these changes over time and to understand underlying mechanisms, the converging evidence is compelling.

Mindfulness should no longer be considered a “nice-to-have” for executives. It’s a “must-have”: a way to keep our brains healthy, to support self-regulation and effective decision-making capabilities, and to protect ourselves from toxic stress. It can be integrated into one’s religious or spiritual life, or practiced as a form of secular mental training. When we take a seat, take a breath, and commit to being mindful, particularly when we gather with others who are doing the same, we have the potential to be changed.

[image error]

What Marissa Mayer Got Wrong (and Right) About Stack Ranking Employees

Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer has been criticized for implementing the practice of stack ranking, most notably in an excerpt from Nicholas Carlson’s upcoming book, Marissa Mayer and the Fight to Save Yahoo! that was published in the New York Times. Most of the criticisms of stack ranking center on the seeming arbitrary nature of the practice, which requires managers to grade their people on a bell curve, with a mandatory proportion of both 5s (excellent employees) and 1s (underperformers), regardless of the actual distribution of performance. According to critics, stack ranking produces excessive and unproductive internal competition, and discourages employees from helping their peers.

Yet stack ranking suffers even more fundamental problems. The fact is that the implicit assumptions required for stack ranking to make sense simply don’t apply in the real world.

Let’s consider a common situation in which stack ranking seems to make sense: education. College courses are often graded on a curve, a fact that draws little protest. I can recall one college physics final exam I took where the median score was 17 out of 100; “stack ranking” made a lot more sense to me than simply failing 90% of the students. Yet the context of a college course could not be more different from that of the workplace. Consider the differences:

College course:

Every student completes the same assignments and takes the same exams

The main purpose of the course is to teach and evaluate the students

Receiving one or two failing grades has few consequences; students can re-take failed classes

Workplace:

In most cases, each employee’s job is different, even if they have the same job title

The main purpose of the company is to create value

Receiving one or two “failing grades” has disastrous consequences and likely means the end of the employee’s tenure

Stack ranking employees who have very different roles, using largely subjective measures that have little to do with actual value, and making critical and irreversible decisions based on those rankings, tends to produce the negative effects cited by the critics.

Instead, managers should treat employees like allies:

Each key employee should be on a personalized tour of duty with a specific mission objective that improves both the company’s business and the employee’s career prospects.

Managers should evaluate each employee based on their progress towards and accomplishment of their mission objectives. This connects the evaluation to the actual work being done, and the actual value being created.

Managers should meet with each employee on a regular basis to discuss the progress of the tour, and to confirm that the mission objective is still relevant to the business and the employee’s career. Either party should have ample opportunity to surface any performance concerns, and to take steps to address those concerns, rather than waiting for an artificial quarterly or annual stack ranking process.

This personalized, organic approach actually helps employees reach their full potential, rather than simply attempting to weed out underperformers.

That being said, I can understand why Mayer tried stack ranking at Yahoo. The alliance framework both relies on and is designed to increase the trust between manager and employee. Companies that adopt the principles outlined in The Alliance typically follow a measured, incremental approach. As trust increases, they can broaden the scope of an alliance-based set of programs.

But Mayer was an outsider CEO, brought in to turn around a company in crisis. And one of the biggest issues afflicting Yahoo when she arrived was a broad complacency and tolerance for low performance. She needed to shrink the organization and get rid of underperformers. Stack ranking gave her a simple and scalable tool to accomplish those objectives, albeit at a cost in terms of employee satisfaction. In the case of Yahoo, the benefits of stack ranking may have outweighed its negatives, at least in the short term.

Now that Mayer has been Yahoo’s CEO for nearly two-and-a-half years and has had time to build relationships and trust with the rest of the organization, the time may be right to phase out stack ranking, and start adopting a more productive approach.

[image error]

To Make Money with Digital, Be an Innovator – Not a Strategist

For many companies considering how digital technologies could or should transform their business models, the questions they face are questions of unprecedented uncertainty, where past experience may be no help.

It’s uncomfortable terrain for many strategists. But it’s familiar territory to innovators, who’ve spent decades wrestling with the problem of how to manage uncertainty when there is little to guide them in getting their new offering to a new audience or market.

But unless your company competes on the basis of continuous innovation, like, say, Apple or Amazon, your innovators probably work separately from your strategic thinkers. That’s a shame, because the discipline of the innovation process is tailor made for addressing the wealth of unknowns that moving to a digital business model entails.

For over a decade now, we’ve been studying how the best innovators manage uncertainty, and in the course of our research we’ve seen three traps strategists fall prey to in fashioning digital business models, which they could avoid if they approached digital business modeling as an exercise in innovation.

Trap 1: Replicating What You Did Before

The greatest temptation is to replicate your current business model digitally. That’s understandable, since making your existing resources do more makes good financial sense and often makes good strategic sense, especially to strategists who have seen the wisdom of moving carefully from core to adjacencies.

But if you think of a digital business model as an innovation, rather than as an extension of your core strengths, it becomes easier to think of the shift as an opportunity to take advantage of new capabilities, rather than leverage old ones.

Innovators lower the risks of moving beyond their comfort zones by breaking down new-product development into a series of small, low-risk, low-cost experiments designed to test the assumptions behind a new offering. This same approach can be used to test out the assumptions behind a new business model before going full bore over some cliff.

Insight Center

Making Money with Digital Business Models

Sponsored by Accenture

What successful companies are doing right

Take the shift from print newspapers to online media portals. In the early days, many publishers assumed they could set advertising rates online the same way they did in print, on the basis of the volume of readers. The prospect of lowering production costs, by not having to print and distribute paper, combined with the ease of (theoretically) reaching a larger audience online, led many to assume that the online versions of their publication would be even more profitable than the print versions. Some further assumed that first movers had the advantage online, and rushed to get big fast.

But those assumptions turned out to be famously flawed, as advertising dollars were spread far more thinly across a proliferation of sites, and publishers found they could not even replicate their print revenue streams, let alone scale up. Incentives for the sales team turned out to be radically different, as well, as large, in-person bulk ad buys gave way to a series of small, semi-automated sales transactions.

Still, the new medium represented new opportunities waiting to be explored, even for incumbents. Salt Lake City-based Deseret Media, for instance, experimented with creating a free online local classified website, in the process building capabilities in web design and user interfaces. In this way, the 165-year-old newspaper succeed in creating a site that most viewers agree is easier to navigate than Craigslist, and as a result, KSL.com is the only local newspaper classified site to beat out Craigslist in one of the 40 largest U.S. markets.

Trap 2: Build It and They Will Come

On the other side of the coin is the temptation to just jump right in and build something awesome and expect everyone to see its obvious merits, just as you do.

But bankruptcy courts are littered with seemingly clever software programs and apps that were written in the mistaken belief that customers would want them. Successful innovators take a step back, before building, to deeply understand what problem they could really solve with the new digital offering.

Our favorite way to think of this is in terms of what Clay Christensen has famously called the “job-to-be-done.” Essentially, this is the view that all successful products and services satisfy a functional, emotional, or social job a customer needs to do by either mitigating some pain or creating some gain, and by doing so better than other available alternatives.

It’s the “better than other alternatives” that matters most in digital business models, we’d argue. Take, for example, Instagram’s recent success. Instagram clearly allows for social connection, but so do many other online services. So what job is it doing that other sites do not do as well? Anyone who has written a blog understands how much time it takes to craft high-quality material. Twitter, arguably reduces the pain of self-expression down to 140 characters, which for many purposes is enough to get the job done. But with a few clicks on Instagram, users can not only send a picture (possibly worth a thousand words), but through the use of filters and simple effects easily and conveniently multiply their powers of self-expression, as well as get social validation through the feedback function.

Trap 3: Thinking the Sale is the Finish Line

Enlightened strategists have always focused not only on the point of sale but on the entire consumption chain before the sale, mapping out how customers would become aware of, evaluate, and purchase a new offering. But we’ve noticed that even enlightened leaders often miss or ignore what happens after the sale — service, support, and disposal. For digital business models, however, the “virality coefficient” — the rate at existing users recruit new users — may make how you connect to customers after a sale the key to success or failure.

For example, when Dropbox first launched as an innovative file storage, syncing, and sharing service, its executives assumed they could simply acquire customers using Google AdWords. But competitors had bid up the cost of keywords so much that it was costing Dropbox between $300 and $500 to acquire a customer who paid $100 a year in subscription fees. Recognizing that the business model was unsustainable, co-founder Drew Houston proposed another approach, one used by PayPal during the dotcom boom to acquire customers: Dropbox offered 250MB of free storage for referrals (both to the giver and recipient of the referral). Adoption of Dropbox shot through the roof and customer acquisition costs fell to pennies on the dollar.

Connecting to customers after the sale may mean transforming a one-time sale into a recurring subscription revenue model. Alternatively, it may mean giving away part of the business for free, recognizing that both the additional referrals and data captured (which, with permission, might be resold to advertisers) may have more value in the long run than the short-run sales.

Or not. It might turn out, as the newspapers found, that giving something away for free doesn’t automatically lead to revenues from anyone else. That’s why the only way to resolve these kinds of questions is to test them out on the cheap. Fortunately, if digital business models are risky, they are easy to experiment with.

Some of our students, for example, believed there was a need for an improved collaborative project management tool (akin to Base Camp). But was that so? To find out, they launched a website that merely described what their software would do and then offered a year’s free access to anyone who sent referrals of five other potential customers who also signed up. In four weeks, 140,000 people signed up for their no-name startup. That number rose to 300,000 soon after, exceeding the growth rate of Base Camp itself. But the important thing here isn’t that experiment worked – it’s that if it hadn’t, the students would have found out that their idea wasn’t the next Base Camp before they’d committed serious resources to it.

Every time you introduce a new value proposition to a new audience (or change some key element of your business model) you introduce uncertainty. Introducing a digital business model often introduces uncertainties not only of degree but of kind, shifting the effort out of the realms of strategy and into the realms of innovation. Innovators know they need to manage uncertainty differently than they manage the execution-oriented part of the business. It’s a lesson that strategists might profitably apply, too.

[image error]

How France Used Unemployment Benefits to Kickstart Entrepreneurship

France produces fewer start-ups than the average developed nation, and has historically had a higher rate of unemployment. Critics are quick to blame both on its generous welfare state. But in 2001, the nation’s policymakers were able to boost entrepreneurship, according to a recent paper. And they did it by making welfare policies even more generous.

Unemployment insurance had been a substantial deterrent to entrepreneurship in France, because individuals without jobs ceased to be eligible for it if they founded a business. So the French Ministry of Labor enacted a series of reforms which allowed founders to continue to draw unemployment benefits during the first three years of their business, subject to some restrictions, and to remain eligible for such benefits if the business subsequently failed.

The reforms appeared to have an almost immediate effect: the rate of new firms created rose by 25%. But researchers at MIT, Berkeley, and HEC Paris set out to determine whether the increase was actually caused by the policy change. They wondered whether some of the change could have had to do with the state of the economy, or whether the quality of the new businesses was lower as a result. They found that at least a large part of the increase was directly a result of the policy, and that the new businesses seemed at least as productive and sustainable as older ones. Moreover, they estimate that the change boosted the nation’s economy by €350 million per year, at a cost of only €100 million annually.

To measure all this, the researchers broke up the data (from 1999 to 2005) by industry. The idea was that it would be comparatively easier for the unemployed to start a business in an industry where small firms are already prevalent. (Starting a business in an industry made up of larger firms would require more capital than was provided by unemployment insurance.) If the increase in entrepreneurship was really caused by the reforms, it ought to be more dramatic in industries with more small firms. And that’s just what they found.

They used the same approach to measure the quality of the businesses. Start-ups founded after the reforms in industries with more small firms — the ones more likely to have been the direct result of the reforms — were just as likely to stay in business, to grow, and to hire as those in industries with more large firms. The entrepreneurs were equally as well-educated in both groups as well. Perhaps most importantly, the new firms were more productive and paid higher wages than the average incumbent.

“Our most conservative estimates suggest that about 12,000 additional firms are created every year thanks to the reform,” the authors conclude.

There is a narrow lesson here, and a broad one. The narrow one for policymakers is that welfare programs can in fact distort entrepreneurial incentives, but dismembering those programs isn’t the only or best option. This is consistent with previous research, which found that expanding government-sponsored health insurance encouraged more people to start businesses. And that leads to the broader lesson.

Because entrepreneurs inevitably take risks, we tend to think that people who aren’t comfortable with large amounts of risk wouldn’t make good entrepreneurs. The data doesn’t support that view. Research from the UK has shown that in fact, entrepreneurs are more cautious than the general population. “Higher risk-taking increases the propensity to launch a business, but does not correlate with greater start-up success,” wrote Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, a professor at University College London, in a previous HBR article, citing a meta-analysis of several studies. “In fact, conscientious and prudent founders tend to do significantly better.” And in France’s case, the entrepreneurs who were enticed to start something once the financial risks were lessened were just as qualified and successful as those already in the game.

In that sense, this research is an argument about what entrepreneurship is and isn’t, and who’s qualified to do it. Entrepreneurs will always take some risks, particularly with their time and reputations. But starting a business is about more than that, and it shouldn’t include being forced to go broke in the process.

[image error]

You’re Never Too Experienced to Fake It Till You Learn It

Novices emulate favorite bosses and colleagues in an effort to look and talk as if they know what they are doing — even when they have no clue. It’s how they develop and grow (just as children do, first imitating their parents, then their peers). But this natural — and efficient — learning process tends to break down as people gain experience and stature. As we become more certain about what we “know” and who we are, the idea of mimicking others feels artificial, even distasteful. So we stick with what’s natural and comfortable. And that’s precisely what gets us in trouble as we hit career transitions that call for new and different ways of leading.

In my research on how experienced managers and professionals step up to bigger leadership roles, I have observed both the value and the difficulty of returning to our youthful, fake-it-till-you-learn-it strategies. The only way to pick up the “softer” skills that we need to lead with greater impact is to observe and emulate people who already have them, trying their strategies and behaviors on for size before making them our own.

Take, for example, Clara, an HR specialist who was promoted a level above her boss to become her company’s director of operations. The new assignment meant managing people who had been her superiors and overseeing functions, like finance, in which she had no expertise. “I understood in theory that a good manager should be able to manage areas without understanding the technicalities of the work,” she told me, “but in practice this made me feel like a fraud.”

At a loss for what to do, Clara decided to emulate people she saw as effective leaders. When she met with the finance manager, one of her new direct reports, Clara greeted her warmly, putting an arm around her shoulders as she’d seen her own boss do in the past. And in her first staff meeting, she tried out the blunt and direct way of speaking that she’d frequently noticed other directors in the company using.

“I went home exhausted each day from playing the role of ‘Director of Operations,’” she said. It was depressing — even embarrassing at times. Still, she persisted, adjusting her tactics along the way. After about a year, in the course of leading a successful meeting, she realized she had grown into the role. “As I began to gain confidence in my own ability to do this job, I also began to fall into a leadership voice that felt more like my own and less like an imitation of my former bosses.”

This kind of identity stretch-work comes more naturally to some people than to others. Psychologist Mark Snyder identified the profile and psychology of “chameleons,” people who are naturally able and willing to adapt to the demands of a situation without feeling like a fake. Chameleons have core selves defined by their values and goals but have no qualms about shifting shapes in pursuit of their objectives. Then there are the “true-to-selfers,” as I call them, those who view situational demands that push them away from what they do naturally as threats to their authenticity. Their self-definitions are more all-encompassing, including not only their innermost values, but also their leadership styles, speech, dress, and demeanor.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Office Politics

Communication Book

Karen Dillon

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

A quintessential chameleon, author Michael Lewis famously describes how imitation helped him transform himself from an inexperienced trainee into a highly successful bond salesman in his best-selling book Liar’s Poker. “Thinking, as yet, was a feat beyond my reach. I had no base, no grounding,” Lewis writes. “So I listened to the master and repeated what I heard, as in kung fu. It reminded me of learning a foreign language. It all seemed strange at first. Then one day, you catch yourself thinking in the language. Suddenly words you never realized you knew are at your disposal. Finally you dream in the language.”

People gravitate more readily to chameleon strategies like Lewis’ earlier in their careers, when it is easier to accept and express ignorance. With experience and success, our habitual ways of thinking and doing become more entrenched and our work identities solidify. We value authenticity, so we continue to act in accordance with our sense of who we are — even when it becomes patently ineffective. Unfortunately, the effort we put into protecting our “true” identities can really hold us back later in our careers, when we’re trying to build on past successes to take on new and bigger roles or responsibilities as leaders.

Suppose you have become known (and been rewarded) for your ability to use rigorous analysis to figure out solutions to organizational problems. What happens when you’re suddenly expected to start selling your good ideas to diverse, skeptical stakeholders outside your area of expertise? Intellectually, you know you need to persuade and inspire, but you just can’t bring yourself to do it. So, you put more work into your facts and figures — and when your ideas repeatedly go unheard, you conclude that the organization and its key players are “political.”

A better option is to look around to identify people who are good at selling their ideas — and watch carefully what they do and how they do it. People who use this strategy concentrate their efforts first on reproducing the behavior they have observed, even if they don’t fully understand it. Then with practice, like Lewis, they try “to get inside the brain of another person.” In their minds, they’re not being inauthentic — they’re simply evolving so they can get the job done. After a while, they find they have acted their way into a new way of thinking. They haven’t just developed their persuasion skills; they now value a different way of working and see themselves as the kind of people who are good at getting others on board.

By definition, transformative learning starts with unnatural and often superficial behaviors. When we are working at improving our game, a clear and firm sense of self is a compass. It helps us navigate choices and work toward our goals. But when we are looking to change our game, a rigid understanding of authenticity is an anchor that keeps us from sailing forth. By viewing ourselves as works in progress, we multiply our capacity to learn, avoid being pigeonholed, and ultimately become better leaders. We’re never too experienced to fake it till we learn it.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers