Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1328

January 22, 2015

How the U.S. and India Can Strengthen Their Business Ties

Barack Obama is the first American President to visit India twice while still in office. When he leaves New Delhi on January 26, the bilateral benefits of the time invested might flow for a decade or longer—but it will depend on how well both sides manage some of the barriers that have kept the two giant countries from working together well in the past. As executives with deep experience in both countries, we see at least three ways that the President—and anyone developing business in India—can improve the mutual understanding between the two countries.

Focus on Relationships: Business relationships between Indians and Americans, like political alliances, develop over time. Trust cannot be won quickly. While this might seem obvious let us look at the reality on the ground.

Many large American corporations send expatriate executives to India for one- or two-year terms. By the time these arrivals start to understand the textures of India, it is time for them to leave. We see some companies limiting their India offices to suites inside of upscale hotels. Sometimes for three years or more. A few companies locate their India-focused expats in Singapore, Dubai, or Hong Kong. While these are comfortable locations, many Indian customers assume these companies are not yet committed to India. While there is nothing wrong about developing a phased relationship with India, success will be limited if Indians perceive that the relationship is also tentative, not just phased.

Some years ago one of us (Bagla) took a top executive of a major agricultural company from California to India for his first business visit to meet distributors. At the time, many of the legacy distributors operated from tiny congested locations in the heart of the old walled city of Delhi and most offered to meet us at our hotel. We advised the client to accompany us to their place of business instead. While a few of them were embarrassed about their location in the short run, all were impressed by our client’s willingness to brave the dust and noise of Khari Baoli. This outreach started the relationship building on a proper footing.

Proceed with patience: Last September, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Obama took the highly unusual step of writing a joint op-ed piece for the Washington Post. Many seasoned India hands chuckled at the line that pointed out “the full potential of our relationship is yet to be realized.” This is true since small countries such as the Netherlands and Taiwan have larger trading relationships with the United States than India does today. Lack of cultural dexterity on the part of American executives and diplomats is one key bottleneck in developing the relationship more fully.

There is a nuance in the final sentence of that op-ed piece: “Forward together we go — chalein saath saath.” Some Americans are getting impatient with the pace of progress in India already because they have interpreted this message as “Let’s run together.” We think that it is better construed as “Let’s walk together.” And you must walk in India before you can run. Such walking can build more durable and productive business relationships. One such enduring corporate relationship is a 50-50 joint venture between Tata Motors of India and the Cummins Engine Company of Indiana. Most advisors would propose a 51-49 JV in India to be clear who is in control. Co-equal shares imply and require the kind of trust that is built by walking together before you run or fly.

Adapt your communications style: In dealing with Japan, China or Germany, most Americans recognize that they need a translator or interpreter. But not in India. There is an illusion of full communication since most of them appear to speak English. There are two layers of fallacy in this assumption that lead to stress.

The first layer that becomes apparent to visitors is the use of Indian English. In India a hotel can sometimes mean a restaurant, a bullet can be model of a motorcycle that sells more than Harley Davidson, and a bisleri can mean bottled water. Someone might ask President Obama if he likes curd (plain yoghurt) with his Indian dal. If there are hoardings along Sardar Patel Marg to welcome him and his team at they drive in from the airport, we are just talking about billboards.

There may be talk about the loin (lion) represented in the “Make In India” logo, particularly if the Indian speaker is not convent-educated. The visiting Department of Energy team might be told, if they have earned the trust of their Indian counterpart that Mr. Modi hopes to eliminate load-shedding in India. The Education team may hear that some deemed universities want to collaborate with American community colleges. If a senior Indian aide confides, “My Mrs. is out of station so I am not bringing my tiffin with me to work this fortnight,” the Obama team needs to understand that his wife is travelling so he’s not bringing his lunch with him.” These and hundreds of other terms are explained, in the Indian English Dictionary, the busiest section of Bagla’s website.

The answer to the second-layer fallacy cannot be found in a dictionary, however. Sometimes the intent of an entire action is misunderstood. Like most Asians, Indians are indirect communicators, and the normal blunt American style makes them uncomfortable. It is hard for them to decline an unreasonable request, particularly from a foreign visitor. It is difficult, but important for Americans (and Western/Northern Europeans) to appreciate that indirect communication can be equally effective in delivering a message compared to direct communication.

This second layer fallacy creates mismatched expectations on both sides and can erode trust rapidly. One example occurred when, after a prolonged and turbulent democratic process in both countries, and at the high point of the 2008 financial crisis, both houses of Congress approved a landmark civil nuclear agreement between India and the United States. Almost immediately, then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice showed up in Delhi to take the agreement to “the next stage.” But the Indian side wasn’t ready yet. They had more walking to do and Secretary Rice was trying to fly. Six years later Westinghouse Electric and GE Nuclear are still waiting to see business emerge from this agreement.

When presented with American bluntness, some Indians interpret it incorrectly as crudeness. Others have told us in confidence that many American appear to be “simpletons.” To overcome this barrier, Americans need to include team members who are adept at indirect communication. For example instead of asking,”Is everyone on board with our plan?” you might consider a less direct approach, such as, ” I’d like to hear from everyone about one area of concern you have before moving forward on this plan.”

It is good that President Obama’s team includes seasoned India hands such as Assistant Secretary of State Biswal, who served as Assistant Administrator for Asia at USAID, and Assistant Secretary of Commerce Kumar, who founded and ran the US-India practice for a Big Four accounting firm. Business people who travel without seasoned advisers on their team often miss key points; worse still, they reach erroneous conclusions about key issues.

Subtle but significant barriers have prevented the two largest democracies in the world from working together more closely. The openness and diversity of both India and America make it possible, however, for any open-minded and humble person in either country to learn about what drives their counterparts in the other nation. Workshops, articles like this one, and books can provide part of the answer. But the rest of the answer depends on what happens in the field, where companies must identify, nurture, and reward employees who want to be adept at both direct and indirect communication; or they must supplement their team with trusted external advisers. There is always room to improve mutual understanding between the two cultures, whether you are in politics or in business.

[image error]

January 21, 2015

Who Has Paid Sick Leave, Who Doesn’t, and What’s Changing

For decades, whether you can call in sick and still get paid has been determined by where you work. Because of this, millions of Americans — 43 million private-sector workers, as President Obama reminded us in the State of the Union — are out of luck, forced to make tough choices about whether to work when they — or their children or parents — have the flu.

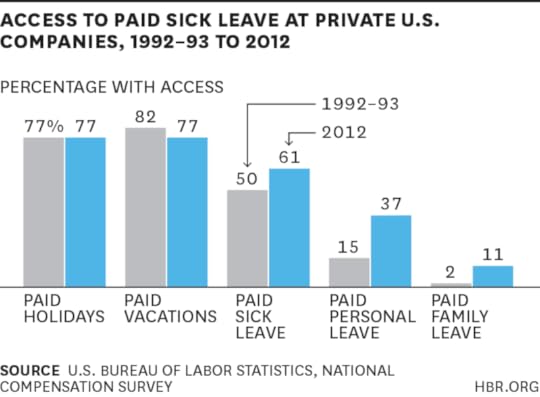

An initial glance at the private sector looks as though access to sick leave has improved. While the percentage of workers with access to holiday and vacation days has stayed the same or decreased over the last 20 years, those with paid sick, personal, and paid leave has jumped:

And the cost of sick time as percentage of total compensation has remained the same. So it’s not costing companies any more than it did in the early 1990s.

Good news, right?

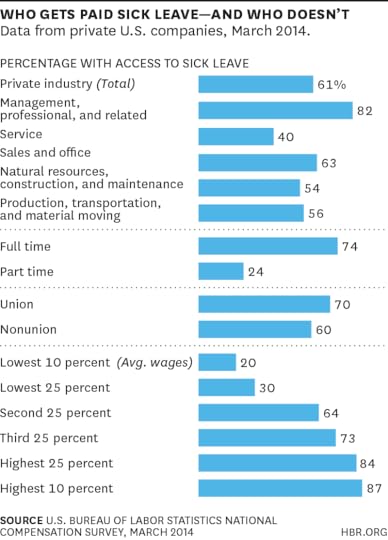

Not so much. When you look at the numbers a little closer, it becomes clear that there’s a significant divide in terms of who gets paid sick leave. For one, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the jump in access to paid sick leave is at least in part due to more Americans working white-collar jobs. This is particularly evident when you break down who has sick leave by sector, with full-time management workers receiving the vast majority of sick leave benefits, leaving service workers and part-timers in the dust. The more you earn, the more likely you are to have paid sick leave.

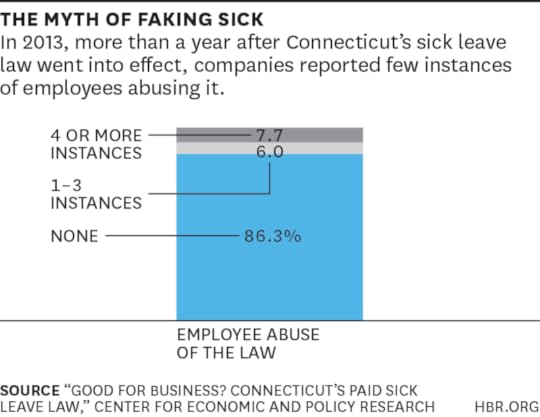

It’s in this climate that Obama is proposing up to seven earned paid sick days for all Americans, citing Connecticut’s 2011 law as precedence. While many expected that law to lead to costly abuse — with employees calling in sick whenever they felt like taking time off — according to data from the Center for Economic Policy and Research, those shenanigans never materialized:

In addition, only a third of eligible employees even used the benefit, and they used fewer days on average than they were allotted.

Obama’s proposal will obviously face an uphill battle in a Republican-controlled Congress, but even the mention of it gives companies the opportunity to rethink the benefits they’re offering employees. For one, we know that higher pay and benefits boost productivity and decrease turnover in the service sector.

Just as with health care, meditation rooms, and Foosball tables, sick leave is today treated as a perk — something certain employees get at certain companies. The Obama administration’s proposal would make it more like a safety regulation — something every company adheres to, for every employee.

The paradox is that although white-collar workers are more likely to have paid sick leave, they balk at using it; meanwhile, a whole host of people don’t have it and thus couldn’t use it even if they wanted to. In the end, all of this means that millions of people are going to work sick, albeit for different reasons and with different repercussions. Even absent government regulation, it couldn’t hurt private companies to do a little rethinking of why that happens, and what can be done about it.

[image error]

Companies with a Formal Sales Process Generate More Revenue

How well is your company managing its sales pipeline? Research conducted by Vantage Point Performance and the Sales Management Association revealed that 44% of executives think their organization is ineffective at managing theirs. (The survey included 62 B2B companies, 39% of which have revenue greater than $1 billion and 37% of which have revenue greater than $250 million.) This statistic is discouraging because there is a direct correlation between effective pipeline management and strong revenue growth.

In our survey of B2B companies, executives were asked to rate their company’s year-over-year change in revenue on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing “drastically decreased revenue” and 7 representing “drastically increased revenue.” Executives were also asked to rate their company’s effectiveness in managing the sales pipeline. On average, companies that reported having ineffective pipeline management had an average growth rate of 4.6; companies with effective pipeline management had an average growth rate of 5.3, a 15% increase. Even more interestingly, companies that mastered three specific pipeline practices saw 28% higher revenue growth.

What did these top companies do to achieve such a high level of success? Here are the three best practices that these all-star sales forces have in common, as well as ways to implement them in your company.

Clearly define the sales process. Pipeline management includes how the sales pipeline is designed, how it is measured, and how it is used to drive sales rep performance. However, at its most basic level, the sales pipeline is merely a representation of a company’s sales process. We discovered that sales forces were most effective at managing their sales pipelines if they had invested time in defining a credible, formalized sales process. In fact, there was an 18% difference in revenue growth between companies that defined a formal sales process and companies that didn’t.

So what does it mean to have a formal sales process? For starters, it means having clearly defined stages and milestones that are universally understood by your salespeople. Your sales team shouldn’t have to guess where a particular deal stands or how they should be managing deals in each stage. In addition, your sales process should align with how your customers move through their buying process. Too many sales teams use generic sales processes, and consequently get generic sales performance. Invest the time in developing a unique process for your team, and make sure that they understand how to use it.

Spend at least three hours a month on pipeline management. In addition to having a solid process in place, our research revealed the importance of dedicating enough time and resources to carrying it out well. Companies in our survey that spent at least three hours per month managing each rep’s sales pipeline saw 11% greater revenue growth than those that spent fewer than three hours per month. But success doesn’t just depend on the amount of time that’s spent on pipeline management – how the time is spent is just as important.

Many sales forces believe they are spending a lot of time managing their pipelines when in reality they’re spending a lot of time creating forecasts. If your pipeline management discussions revolve around close dates, probabilities, and deal sizes, then you are forecasting. Period. If, however, you spend your time discussing the overall health of your sellers’ pipelines and how they can shepherd more deals to successful closure, then you are managing your pipeline in a productive way. The primary focus of a pipeline meeting should be to help reps develop a game plan to move deals forward, not just scrubbing CRM data and forecasting revenue.

Train sales managers on pipeline management. Our research also revealed that 61% of executives admit their sales managers have not been adequately trained in pipeline management strategies and techniques. This begs the question, “How can we expect our sales managers to do something well when we haven’t prepared them to do it?” Companies that had trained their sales managers to manage their pipelines saw their revenue grow 9% faster than those that didn’t. But not just any training will do. Sales managers need targeted training to address specific pipeline management challenges.

Most pipeline training that sales managers receive is limited to how they log in to their CRM tool and generate reports. What they really need is training in how to make better pipeline management decisions. For instance, sales managers need to know how to determine the ideal pipeline size for each rep. They need to know at what point in the sales process their actions have the biggest impact. And they need to know how to structure pipeline meetings so they enable coaching rather than inspection. Even these few skills can have a significant impact on sales force performance.

Ultimately, pipeline management is a critical activity for all sales forces, and better pipeline management can make a huge difference in sales performance. Our research shows that there are no secrets to realizing this increased performance — you must define your sales process, commit to good pipeline management, and enable your managers to carry it out. If you integrate these best practices into your sales force, you can expect to nail your forecasts, hit your quotas, and see your sales reps succeed beyond what you thought possible.

[image error]

How to Craft an Agile Marketing Campaign

Meticulously designed marketing campaigns are a relic. As research on disruption and market transitions suggests, you’re better off these days if you can quickly identify and adapt to changes in your environment. Sure, you can anticipate multiple outcomes, with branching if-then plans and hypothetical scenarios — but those plans are only as effective as events are predictable. It’s extremely difficult to say how long current trends will remain significant — innovative technologies are popping up faster than we can forecast — and it’s impossible to tell which new trends could emerge during your campaign and thwart your efforts.

So marketers must develop the same mind-set and skills that allow agile tech and product-development teams to manage complex projects with many unknowns and moving parts. Here are some recommendations for doing that.

Think “outline,” not “campaign.” If you chart your campaign in such detail that it’s unalterable, you run the risk of being pinned down when something unexpected arises.

For the perfectionists out there, this may be a frightening thought. Many marketers have built their careers on following a series of highly detailed plans based on copious data. You still can, and should, draw on customer research, but leave room for growth. Map out your starting point, in as much detail as you wish, and then roughly outline your vision for the first few milestones in your campaign, keeping your plans tenuous and easy to adjust.

Consider this sample outline, from a firm that was launching a new clothing line.

Phase I (Weeks 1-4): Announcements and Initial Advertising

Submit press release detailing new clothing line and reinforce through social media.

Go live with new clothing products on the e-commerce platform, and schedule the release of images and links on social profiles.

Add banner to homepage, showcasing our new fleece-lined jacket, projected to be our top seller.

Initiate e-mail blasts to current customers, first announcing the new product line, then introducing discounted offers in subsequent weeks.

Introduce weekly articles, each highlighting a new product, and syndicate through social media.

Begin Google PPC campaign for new products, highlighting the fleece-lined jacket and seasonal keywords.

Phase II (Weeks 5-8): Ad Reinforcement and Consumer Engagement

Reach out through other advertising channels: magazines, direct mail, TV

Phase III (Weeks 9-12): Introduce and Promote Sale on New Products

Phase IV (Week 13): Analyze and Regroup

Note that the first phase of launch is outlined in detail, while subsequent phases are described in broad strokes. This allows you to measure impact and determine whether to keep going, make adjustments, or scrap what you’ve got and start over. The clothing company found that its fleece-lined jacket was underperforming and quickly substituted another product for it. The PPC ads were carrying significant traffic, but not converting, so in Phase II those were replaced with a direct-mail campaign.

Start small. It’s also good to plan modestly at the start and gradually become more ambitious, as you test the waters — especially if you’re venturing into a new channel. For example, if you’re going to run a series of pay-per-click advertisements, begin with a budget of only a few hundred dollars. Run it for a few weeks, analyze your results, and if you’ve been successful, increase your budget. This way, if a more attractive medium comes along — or if an unexpected obstacle interferes with your campaign — you’ll have a chance to make adjustments or bail out before you’ve spent too much money.

The same rule applies to scope. You might restrict your efforts at first and ramp up when your audience grows.

Take breaks. As you venture forth, pause frequently to reevaluate your position. If you’ve sketched out a minimalistic outline, you might do this when you get to each loosely defined milestone. Review the effectiveness of your current efforts, including projected profitability. Determine what changes have occurred in your environment, such as new competitors, technologies, or trends. And then tweak your strategy.

To carry out these recommendations, you have to pay close attention to your surroundings. Regularly visit industry news sites to stay on top of developments and consider how they could affect your marketing plans. Watch what your competitors are publishing and how well-received their ideas are. Keep in close touch with your target audiences, as well — conduct regular user surveys and measure how existing and potential customers interact with your brand. Track behavior on your website, through social sharing, and in reviews and comments. How are people’s priorities changing? What new tools are they using to make their lives easier? Adopt new trends early, and drop them when they appear to decline in relevance.

Agility doesn’t come naturally. You have to be at peace with the fact that, more often than not, you can’t predict what’s coming next. But this is a skill you can cultivate through awareness and practice. And really, to survive, you don’t have a choice.

[image error]

Dysfunctional Products Come from Dysfunctional Organizations

Producing great products isn’t just about creativity and execution. It’s also about organizational alignment. Let me tell you a quick story. One of my alumni, Eli, recently finished a contract with a government transportation agency. She had been tasked with spending time with the agency’s customers – regular citizens – to identify usability issues in their mobile app. She had quickly discovered that the app was basically a trainwreck. People couldn’t understand how to use it, frequently lost money during the ticket purchasing process, and often got frustrated attempting to pay bus fare with an electronic ticket.

Eli presented her work to executives and product owners in a two hour meeting. As the meeting progressed, the lead product owner got more and more agitated, and eventually exclaimed, “I can’t control any of these issues!” and stormed out. It became clear that the people who hired her were using her consulting as a weapon in the organization to compensate for interpersonal and cultural issues – to highlight misalignment.

As we were chatting about this experience, she offered a tremendously insightful view of what happened. “The problems in their software are directly indicative of the problems in their organization.” The company had layers of bureaucracy and management, siloed functions, and a culture of friction and defensiveness. Their product had layers of disconnected functionality, siloed capabilities, and generated obtuse experiences for users. The dysfunction in the organization became the dysfunction in the product, and that was passed on to the customers.

This is interesting as an intellectual curiosity – we can compare successful products to unsuccessful products and make inferences about the organizations that produced them, and how the “sausage is made.” But it has much more practical implications in the other direction. We can look at the way our own companies operate and make inferences about how our products are perceived. If the process, culture, and day-to-day experience of the organization is chaotic or broken, we can start to predict that our customers are experiencing an equally broken product or service. Since Eli shared this insight, I’ve observed its validity in many products and companies. Of course, there are exceptions, but on the whole it seems true that bad products point to bad alignment.

How can this misalignment be avoided or corrected? First, let’s clarify that we’re talking about a certain kind of alignment – i.e. congruence around a clear vision or goal for a product. This type of alignment is typically attempted in a meeting, where people discuss strategic direction and how the product fits into this. Ideally, everyone involved forms a basic shared understanding of how the world is and how the product is meant to improve it. But more frequently, because words carry ambiguity, meeting attendees leave without a clear understanding of just what they’ve actually agreed to. And even if alignment is achieved during the meeting, it begins to erode the minute the meeting is over. As time goes by, the shared vision splinters. I’ll ask myself “Did we mean this, or that?” – and since I’m moving quickly, I’ll answer it on my own. Then I’ll act on my answer. Other meeting participants will do the same. And as I make decisions independent of others, we become disjoint. Call this “alignment-attrition” – as the time window between our interactions increases, our alignment decreases.

This dynamic operates differently in different kinds of organizations. In an early-stage startup, for example, everyone sits next to each other. It’s hard to shake alignment in this context, because the window for alignment-attrition is so small. If you sit next to me and we have a conversation and “align” on a direction, there’s only a time window of about 15 minutes that can pass before we have another conversation and course-correct if things have gone sideways. But in a larger company, weeks or even months can go by, and the potential for alignment-attrition is enormous.

In these more distributed contexts, a visual model becomes one of the most effective tools for minimizing alignment-attrition. A visual model captures and freezes a thought in time. By building a visual model together, alignment is offloaded to and “frozen in” the diagram. Your thoughts, opinions, and views will change, but the diagram won’t, and so you’ve added a constraining boundary to the idea – and a tool for concretely visualizing how the product vision is changing. Herein is the magic of leveraging visual thinking in a large, distributed organization. A visualization of a product strategy (or almost any strategy) is easily consumable, while a requirement document is not. A visualization can be viewed by many at once, while it’s difficult to collaborate on generating a spreadsheet or specification. And most importantly, a visualization formalizes an emergent idea and solidifies it at a moment in time.

Here are some concrete process steps for reducing alignment attrition with visual thinking:

Facilitate an interactive workshop between constituents early in the process.

Rather than having a traditional meeting with a powerpoint and a lot of talking, structure the meeting with creative activities – storyboarding, sketching, or other forms of making.

After the workshop is over, capture the visual output, and revise it to be crisp and concise.

Circulate the visual broadly amongst the stakeholders, and ask for feedback on it; integrate changes, and as you work through the project, continue to revise the visualization and publish it periodically.

Besides enhancing and maintaining alignment, these steps help mitigate other important problems associated with conventional product management. Traditionally, a product manager might view her job as one of dictating requirements for features and functions in a product. In this model, alignment becomes less important than conformity. Top-down authority mandates what everyone works on, and a requirement document attempts to act as the rulebook. This almost always results in the people “lower down the chain” feeling disenfranchised. Not only are they not aligned, but worse, they feel no pride of ownership in the actual strategic direction that’s been set. If the foot soldiers carrying out all the tactical jobs of product creation have no visibility into the larger direction of the organization, and are unable to answer the question, “Why am I doing this?,” not only does this jeopardize the product, but it misses out on a huge opportunity for leveraging and increasing the positive engagement and productivity of the organization.

As companies grow and struggle with increasingly complicated and ambiguous product challenges, visual thinking, and product processes built around concrete visuals, help to clarify the challenge for everyone involved – and to increase the likelihood of creating a successful product.

[image error]

When It Comes to Digital Innovation, Less Action, More Thought

A few years ago, we had an idea for a new business opportunity. One of our colleagues owned a restaurant and was complaining about the amount of money he lost because expensive bottles of liquor often went missing (the industry calls this “shrinkage”). This is a problem affecting tens of thousands of restaurants — an attractive target market. So, like good innovators, we began working on a solution to our colleague’s problem by building an automatic liquor inventory-management system.

We partnered with a company in a Singapore that had expertise in RFID technology, and began to put together a solution involving tags on bottles, a customized storage unit that could read the tags, and a software management system. The system would give owners real-time inventory information, which would help them to identify shrinkage early. Wall-mounted cameras near the storage locker would allow them to see precisely when a bottle left the locker, which would serve as a strong deterrent. A matching tag reader in the bar allowed the software to send out alerts when a bottle was removed from the storage locker but never showed up at the bar.

As we went through various iterations of the solution and spending mounted, it became increasingly clear that there were good reasons why no one had tackled what seemed like an obvious opportunity. The integration between the tags, the storage unit, and the software was technologically tough to pull off. What’s more it required busy bartenders, who weren’t particularly interested in making their jobs more complicated, to scan new bottles before putting them in the locker. Integrating our software into the myriad inventory systems used by restaurants across the United States was even trickier. When we finally had prototypes to show customers, they balked at the idea of investing in expensive hardware when they could simply hire an individual consultant to provide occasional advice about stopping shrinkage. In 2009, we decided to shut the business down.

Insight Center

Making Money with Digital Business Models

Sponsored by Accenture

What successful companies are doing right

Our failure highlights a hidden challenge facing innovators today. The simplicity and affordability of innovation has led to too much action without thought.

Starting our business wasn’t free by any means, but by tapping into low-cost designers in India, partnering with the company in Singapore with the enabling RFID technology, and using off-the-shelf software, we were able to develop the first version of our solution relatively quickly and cheaply.

And today, almost a decade later, the cost of starting such a business has radically decreased. Imagine starting a computer hardware business today. An entrepreneur can rent computing capacity from Amazon Web Services, find skilled designers via eLance, accelerate software development with GitHub, place targeted advertisements on Google or Facebook, and tap into a legion of contract manufacturers. Scaling a business still requires hard work and investment, but an entrepreneur can develop the first version of a solution and approach early customers on very lean budgets.

That would seem to be good news for innovation, and in many ways it is. But it has also created the ever-strengthening impression that the only way to learn is by action. Paralysis by analysis, the bane of many a large organization, should certainly be avoided. But so too should doing without thinking. In fact, doing without thinking is arguably even more dangerous because you can squander time and money by tripping over traps that could easily have been identified if only you’d done the right work beforehand.

Before you fling your minimal viable product out into the world to see what happens, at the very least make sure you have done the following:

Identify offerings comparable to what you envision that have struggled commercially and find out why. Perhaps you’re about to make the same mistake.

Consider why it is that the large companies that could have gone into the space you’re contemplating haven’t. Is it possible they know something you don’t?

Talk to someone who knows more than you do about the key part of your business, such as your target customer, distribution channel, or business model. Are there hidden risks?

Document, with a degree of detail, a single transaction. Who is your first customer? How will he hear about your idea? How will she obtain it? How will you support him if he’s not happy?

Devour publicly available financial statements for companies competing in markets related to yours. How do people make money? What big investments are typically required? Are you missing an important ingredient that is necessary to compete? Are you underestimating what it will take to get to market?

Create a hypothesis for how you will make money, and describe it to a savvy friend. Ask that friend to poke holes in it.

A company that aspired to bring a sustainably oriented product to the university market shows the benefit of proper upfront thinking. The team was developing a plan to pilot the business. As they mapped out a transaction, they imagined that it would take a few months for them to close their first sale. But since they’d never sold to the university market before, they thought to check their assumption with some people in their network who had relevant experience. A couple of calls to experts suggested that the product the company contemplated crossed several internal jurisdictions, and could therefore take years to sell, not months. The business model wouldn’t make sense with such a long sales cycle, so the team decided to consider other target markets and entirely different models.

This kind of learning can happen very quickly. While it doesn’t replace the very vital lessons that comes from prototypes, pilots, and other mechanisms that get you as close to the realities of the market as possible, it certainly enhances learning from those activities.

If an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, perhaps an ounce of preparation is worth a pound of prototypes.

[image error]

Stop Playing the Victim with Your Time

It’s just not fair. There’s always too much to do. Everyone just keeps piling more work on me. I feel so helpless.

Sound familiar? If so, you’re not alone. Many people feel like they have a crushing number of requests coming at them from every side that make them a victim to their circumstances. They see forces outside themselves as the reason that they don’t have time to exercise, can’t leave work at a reasonable time, or just generally struggle to get everything done. Although there are occasionally situations that are outside of your control — that recent bout with the flu, for example — most aren’t. And even though it can feel gratifying in the short term to blame others for your situation, this attitude toward your time investment will leave you truly powerless in the long run.

When you play the victim with your time, everything around you suffers. You’re constantly on edge in your interactions with others because you fear that they’ll pile yet one more thing on your already heavy load. Since you don’t believe you can ever say, “no,” your “yes” comes out of a place of obligation and resentment, not wholehearted commitment. Since your situation seems so difficult, you don’t attempt to plan or work more efficiently because you believe that you will have to work all the time no matter what and are convinced that it’s impossible to get everything done. You eventually stop trying because you believe no matter how hard you try — you’ll fail.

In my work as a time coach, I’ve seen that individuals often have a much greater ability to influence their situation than they realize. But the breakthrough only happens when they start exerting their personal power instead of waiting for something around them to change. It’s similar to when people who find themselves in debt blame the credit card companies, instead of accepting that they had a choice in spending more money than they had. Only by accepting that they can — and need — to change and then taking steps to do so can that balance go down.

The way to break out of this victim mind-set is to stop blaming others, and instead, take ownership of your time and take responsibility for changing yourself. Here are three practical steps to take back control of your time:

Observe your reaction. Become aware of how you respond when your time investment becomes misaligned with your priorities. Do you always look for someone to blame? My boss always gives me too much to do. Do you pity yourself? Poor me, yet another stressful day. I’ll get some ice cream to make myself feel better. Do you reject advice or suggestions? How dare my wife suggest I could work differently to get home earlier. That’s just not possible. Do you ever say no to a new project? Do you ever set boundaries? Do you ever ask for support?

Recognize your role. Understand that you are the decision maker when it comes to investing your time. There are certain situations where you simply need to do what it takes to get things done for a short time. That could be when you’re approaching a major deadline, preparing for a new product launch, or drafting annual reports. But overload doesn’t need to be the norm. It’s not everyone else’s fault if you have too much to do and you don’t communicate that to anyone else. It’s yours.

You and Your Team

Getting More Work Done

How to be more productive at work.

Even in top consulting firms known for their rigorous work schedules, there’s room for open communication about time. For example, Boston Consulting Group established a formal global program called PTO (Predictability, Teaming, and Open Communication), which helps establish priorities and time-off goals for each team member. One component of this program is for team members to work together so that each one of them can have a period of time each week when they’re completely off the project. To help make this happen, the teams have weekly check-ins that include talking about how they’re feeling and the value they’re delivering to clients. Each person recognizes their role to openly and honestly communicate about their needs, instead of expecting others to automatically know when they’re overloaded. You must take on the same responsibility in your own organization with regards to your own time, even if you don’t have a formal program encouraging you to do so.

Commit to self-mastery. Regardless of how you’ve behaved in the past in certain situations or with specific people, you have the opportunity to make the future different. Make a commitment to change; choose to respond your environment instead of simply accepting whatever comes your way.

Instead of becoming a victim, take ownership of the situation and your time. This could look like speaking up when you feel that someone makes an unreasonable request so that you don’t end up overloaded. Have your project list on hand when you go to meetings so that if a new project is proposed, you can evaluate its importance in relation to your other commitments. If it doesn’t seem like there’s sufficient time for the new work, propose a discussion about priorities during the meeting or bring it up later with the appropriate parties.

Also, set clear rules and boundaries to prevent taking on too much from others. For example, if you manage staff members who tend to turn in work at the last minute with many errors, require that they turn in items earlier. That allows you to send it back to them to make corrections instead of doing them yourself because you’re on a tight deadline.

Finally, if you’re in a situation where setting better boundaries isn’t possible (such as a job where you’re on call 24/7) and you’re finding your time investment troubles unmanageable, you may need to consider whether you’re in the right job. There are some positions that will not create a sustainable lifestyle for you no matter what you try to do. It’s OK to decide to get out.

By taking responsibility for your time investment choices, you stop wasting energy blaming others and start directing it toward a productive response toward the people and situations around you. With that focus, you can have enough time for what’s most important to you.

[image error]

Robert Reich on Redefining Full-Time Work, Obamacare, and Employer Benefits

One of the U.S. Congress’s first acts of 2015? Trying to redefine what counts as full-time work, from 30 hours a week up to 40. It’s part of the latest attempt by Republicans to alter Obama’s signature healthcare law, the Affordable Care Act, and has already passed the House of Representatives. But it has also had the perhaps unexpected effect of putting the divide between full- and part-time workers front and center in American politics.

I asked former Clinton Labor Secretary and UC Berkeley professor Robert Reich about the debate, and what it means for employers, employees, and the future of American work. An edited version of our conversation follows.

The House has voted to change the definition of full-time work. It seems like the Senate may as well, and Obama has threatened to veto it. Why does the definition of full-time work end up mattering so much to our politics?

It matters under the Affordable Care Act because if full-time work is defined as 40 hours a week, employers can avoid the employer mandate [to provide health insurance] by cutting the work week down to 39 hours. It’s harder for them to do that if full-time work is defined as at least 30 hours. And of course if employers can avoid the employer mandate relatively easily, that means that more workers lose employer coverage, which, in turn, means that more workers have to rely on the government with regard to their health care, either through the Affordable Care Act or through extended Medicaid. That, in turn, puts a large and potentially growing burden on the federal budget, and could cause the deficit to expand.

Government has been a driving factor, along with unions, in defining how we think about what a workday looks like. How has that definition evolved over time?

Much of the tumultuous labor history of the 19th century centered on not just wages, but also on hours. At the center of all of that was the eight-hour workday. When Henry Ford moved to a 40-hour workweek in 1914, that went hand in glove with his increase in wages. And he did both for the same reason: he thought that workers would be more productive and that they would be more satisfied and loyal. And then by the late ‘30s organized labor began focusing on not only wages but also the conditions of work. The great GM strike of 1937, for example, was more about working conditions, such as sick pay and bathroom breaks and so forth, than it was directly about wages. Another important marker was the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act where you had, for the first time, a national standard, which was a 40-hour work week, time-and-a-half for overtime, a minimum wage. There was a ban on child labor. Social security had been passed just three years before and social security was not just the social security for retirees, it was also disability insurance, worker compensation.

It was clear that in the 1930s we were thinking both about wage security, but also about benefits and various forms of social security, provided by government and ultimately by the private sector as well. I think the big change that started in the 1970s was the change in the employment contract itself, because you had a dramatic drop in the percentage of workers who were in the private sector and unionized. And that meant that you no longer had a system of prevailing wages or prevailing benefits. And we see from the 1970s onward a movement toward where we are right now, and that is more workers who are without benefits coming from their employment contract, whose wages are less a function of collective bargaining than they are a function of the workers’ own individual bargaining leverage, which is extremely small if the worker has no particular educational advantage over any other worker.

Is this part of a larger divide over how full-time workers and part-time workers are treated? Or is it just a specific policy debate over how the ACA works?

It’s a broader debate. The ACA certainly brings it into relief, but the more fundamental question is two-fold. First, are workers assets to be developed or are they costs to be cut? Some employers regard even low-wage workers as potential assets. These employers are not only concerned about the costs of turnover and recruiting and training employees who might otherwise leave, but they’re also aware that employee loyalty and relational capital [are] very important to their business, even with regard to frontline workers or workers who are relatively low paid. Other employers have taken a very different approach. They regard workers as costs to cut. They are concerned that payrolls are too high. They look to cutting payrolls as the easiest and most direct way of improving performance. Some empirical work has been done as to which of these views pays off. I don’t think there’s any question that over the longer term, employers who view their workers assets to be developed do better. But let’s face it, we’re working in a very short-term world right now and so there are many forces that are creating incentives for employers to join the camp of regarding workers as costs to be cut.

The other factor here has to do with what level of employee we’re dealing with. Many firms regard their lowest wage employees as fungible. Even if their view is that their talent represents an asset to be developed, they don’t regard their frontline workers or low-wage workers as talent, they regard those workers as fungible costs. And so you get this second divide in terms of where employers draw the line between their so-called talent and their fungible costs.

Economists tend to talk about health benefits as if they are totally fungible with wages. If that were true, and employers could get away with cutting a 40-hour work week down to 39 hours and no longer having to pay for benefits, they would have to offer superior wages to make up for it. What’s missing in that kind of economic reasoning?

Well, the market is not, by any measure, perfectly competitive. The labor market, especially, has a lot of stickiness to it. Workers are not perfectly substitutable. A lot of people cannot move easily from where they are now working to another opportunity. The labor market also is very weak. There are millions of people who are no longer even in the labor market. They have given up looking for work, but they could come back in if demand picked up. Wages are, as a result, very low. Most of the new jobs that have been created in the United States pay less than the jobs that were lost in the great recession. So for all these reasons the notion that if I, as an employer, have to pay less in one domain or one dimension, I have to make it up in another, simply doesn’t hold true.

What about from the workers’ perspective? In a pre-Obamacare landscape the argument is very clear. If you aren’t able to get health insurance at work, particularly if you don’t qualify for Medicaid and depending on your health status, you may be denied coverage or charged an exorbitant rate in the private market. Today community rating is in place and the private exchanges are subsidized. What does the equation look like from a worker’s perspective, in terms of just how much they really want to be on that employer plan versus the exchanges?

We don’t know very much yet. We’re going to find out a lot more over the next few years. But the preliminary evidence seems to show that workers are relatively indifferent as to whether they’re on an employer plan or are getting their insurance off an exchange. Their real concern is cost, not just the cost of premiums, but also copayments and deductibles. One story that has not been adequately talked about, and a problem that hasn’t been adequately addressed, is that we see deductibles and copayments skyrocketing. Even though many workers today are getting insurance who might not have got insurance before on an employer-based plan, they are indirectly paying a great deal because of the size of the copayments and deductibles. And I might add this is also the pattern with regard to employer-provided insurance.

The U.S. is unique in terms of employer-sponsored health insurance. But does this kind of divide, about the benefits that accrue to full-time workers versus part-timers, have a corollary in other countries?

There’s not much of a corollary. If you look at other advanced nations, you see that, because of various forms of national health insurance, employer benefits don’t figure in nearly as much. Meanwhile there is much more part-time and temporary work in the United States, for a variety of reasons, some of which are sociological. Americans are working longer hours — at least Americans who are employed are working longer hours on average than Europeans or even Japanese workers. American workers are also working on weekends and at night to a much greater extent than European or Japanese workers. In fact the latest data show that 29% of American workers work weekends, 26% work at night. These are the highest percentages of any industrialized nation.

How does all of this relate to the challenges that we might face if the “sharing” or access economy – Uber, Airbnb, etc. — ends up growing?

It’s definitely growing. We’re seeing, with regard to a majority of workers in America, that they are moving toward a world in which they have few, if any, employer benefits. They are more freelancers and independent contractors, temporary workers, and part-time workers. Their remuneration is set in what’s essentially a price auction, a spot auction market, [and] varies from day to day or even from week to week. Now if you’re young and well-educated, this kind of a system may be quite attractive. There are many young, well-educated people who don’t want to be as regulated as a typical full-time employee. They want to be more entrepreneurial, they don’t mind that they have to pay for the equivalent of all their benefits. But the older the worker, the less educated the worker, the more the worker has a family or other dependents, that worker is likely to regard this emerging system as a far greater burden and a far greater challenge, because most people have bills they have to pay that are fairly regular. But if their compensation is variable, they can find themselves in very big trouble.

I want to go just back to one point you alluded to awhile ago. Many of the benefits that became part of the standard American labor contract date back to World War II and the days when about a third of our private sector workforce belonged to a union. Those benefits were included in contracts for two important reasons: first because there were price controls and the benefits were a way of circumventing the price controls, at least with regards to labor. The second reason had to do with taxes. It became a very attractive feature of labor contracts to provide these benefits, because many of these benefits were not taxed, as were regular salaries and wages. So that much of the benefit structure we have today is a legacy of the Second World War.

If you could wave a magic wand and put in place the support and welfare policies that you believe are necessary, would you be comfortable with this broad idea of switching risk mitigation from the company to the government, and letting the contracts between workers and companies be more fluid? Or do you think that there’s a risk in going in that direction?

I would definitely support that direction. I think that’s the direction we have to move in, for a number of reasons. First, the benefit structures that we still have in place amount to a very large tax subsidy going to the highest paid workers. Most low-wage workers are not getting tax-subsidized benefits. That makes no sense — that’s an upward redistribution that is socially unjustifiable. Secondly, these benefit systems are very inefficient. They keep people locked into jobs that they don’t necessarily want, or they prevent people from taking opportunities that might otherwise be available. They impede mobility in the labor market. I think it makes a great deal of sense to move away from these employer benefit systems to benefits that are provided through government, either directly or indirectly.

[image error]

January 20, 2015

Why Target’s Canadian Expansion Failed

It was a brief stint for Target in Canada. Less than two years after opening there, Target announced last week that it would close its 133 Canadian stores. Some Canadian Target customers responded emotionally to the news on Target Canada’s Facebook website (“totally heartbroken,” “please don’t go,” “good riddance,” “you obviously don’t understand Canadians”).

Target CEO Brian Cornell decided to close the stores after determining that they would not become profitable until at least 2021. The market exit will stop Target’s continued losses in Canada and help the company focus on its strategic initiatives in the U.S. such as smaller stores in urban places, mobile and online, and its cheap chic merchandising focus—to “be cool again,” as Cornell told Target employees in the fall.

What caused the retailer’s problems in Canada, and what are the lessons learned?

In Target’s annual 2012 report, then-CEO Gregg Steinhafel mentioned Target’s “two years of exceptional dedicated and hard work” to prepare for the international expansion. However, in the end, the market entry seemed rushed and oversized, with 124 stores opening within ten months.

The Canada expansion was announced in January 2013 when Target bought the 220 leases of Zellers, a declining and now defunct Canadian discount chain, from Hudson’s Bay. Target opened its first stores just a couple of months later despite the enormous remodeling work required. Maybe taking over the Zellers leases was too good an opportunity to pass up. But it may have led Target to launch with a bigger footprint than advisable.

Global expansion had been on Target’s mind for some time, and growth through physical stores rather than e-commerce seemed to be the retailer’s preferred path. Canada in particular held appeal as it is not only geographically close and mostly English-speaking but also because Target is familiar to the many Canadians who had visited the stores in the U.S. In addition, Canada was less affected by the recession than the U.S., increasing the appeal of a Canadian venture. What Target may not have fully appreciated was that the Canadian discount sector is a particularly tough market. Unlike the luxury segment, the discount market is fairly saturated by competitors such as Wal-Mart, Costco, Giant Tiger, and Sears.

To entice shoppers to switch, Target had to differentiate itself from all the other discount retail choices. It also had to address two kinds of customers in Canada: those already familiar with the retailer from their U.S. encounters and those new to the brand. While Target did a great job marketing its launch with a multiplatform ad strategy—TV, print, billboards, social media and so on— introducing itself as the new neighbour (notice the localized spelling), its execution was flawed.

The store locations were often out of the way, and stores weren’t up to par with Target’s U.S. look. The new stores also struggled with distribution challenges and shelf replenishment, leading to stock-outs. Particularly for Canadians familiar with Target, the poorly stocked shelves, an assortment that differed from the U.S. stores’, and, often, higher prices than in the U.S. all combined to discourage traffic. These issues also made it hard to win customers who were new to the brand. First impressions count, and once customers are disappointed it’s hard to win back their trust. Given the executional issues, Target wasn’t able to implement its differentiated U.S. concept in Canada.

As Target found, international expansion is difficult, even for top retailers. Tesco’s Fresh & Easy stores in the U.S. went bankrupt; Best Buy closed its stores in the UK after less than two years; Wal-Mart pulled out of Germany and South Korea; and Carrefour left Algeria and Thailand.

Still, there are many globally successful retailers. Their success is based on a competitive advantage achieved principally either through differentiation of merchandise or customer experience (Apple, J. Crew, Michael Kors, Louis Vuitton, Galeries Lafayette) or cost/price leadership (Wal-Mart, Amazon, IKEA, Aldi, H&M, Zara, Uniqlo). In addition, successful global expansion requires deft adaptation to the local markets — the customers, competition, culture and customs, local laws, and so on.

Consider J. Crew’s approach when it entered Canada in 2011. It opened one store in Toronto and then gradually added stores across the country. Like Target, J. Crew had customers that were familiar with J. Crew and unhappy with its Canadian prices, which were 15% higher than in the U.S. But J. Crew responded quickly, absorbing the duties on online purchases and offering a flat shipping fee to reduce the cross-country price differential. It also reverted to allowing Canadian customers to shop the U.S. J. Crew website in U.S. currency. As a result of its careful market entry and execution, J. Crew has been a great success in Canada, growing from one to 16 stores within three years and adding a men’s collection to its original women’s-only line.

In the end, Target struggled with the translation of its successful U.S. concept to Canada and execution there. A slower rollout of stores, the model that worked so well for J. Crew, might have helped it to gain experience in the market and adjust its strategy before expanding further.

[image error]

The Flaws in Obama’s Cybersecurity Initiative

President Obama’s new raft of proposals aim to address the growing concern that America is not taking tough-enough action against the increasing cybersecurity problem of nation-states and criminals (usually criminal gangs) attacking U.S. consumers and organizations. The evildoers’ motivation for doing so is most often money, but intellectual property is also being filched, and the internet is also being used for anything from identity theft to illicit political objectives.

The cornerstones of the proposal are to:

Prohibit the sale of botnets and similar tools

Give the courts the power to shut down networks assembled for cybercrime such as those involved in “distributed denial of service” (DDOS) attacks

Protect companies that share information with the government about computer threats from liability

He also calls for better cooperation between companies and the government when tackling cybercrime.

The problems are certainly real. We are losing on the battleground of cybersecurity. For example, the gains that IT contributed to the GDP of the Netherlands in 2014 were wiped out by the even larger cost of cybercrime. Cybercrime has now become widespread enough to be a drag on growth in many countries. By some estimates, it costs between $500 billion to $1 trillion worldwide. That’s bigger than the GDP of 75 countries combined.

But how much can any government do to address the problem of cybercrime? And will these proposals do anything to fix the situation in the U.S.? Many of the criminal gangs (and certainly nation-states) lurk beyond U.S. jurisdiction — or at least, beyond the capacity of law enforcement to track them down in large numbers. Therefore, criminalizing many of the activities and products associated with cybercrime is likely to have more symbolic value than actual effect.

This is a limitation that would be faced by any country’s government, except perhaps the one where the crooks live. Russia, for example, has an exploding underground cybercrime industry. Trend Micro’s findings are that you can buy a botnet outright for about $700, or rent one for an hour for $2 — enough time to do serious damage. Trojans that let you spy on incoming and outgoing texts will run you $350.

Every country now has its own special wares to peddle. Brazil is apparently the place to go if you’re in the market for some banking malware. China’s gangs have their own special portfolio to sell. In terms of the competition between Russia and the United States, the homes of the biggest criminal hosts, Russia is winning bigtime. In three months in 2012, Russia’s share of malicious hosts rose by around 10%, and the United States lost 10% of its bad boy computers. There’s ample evidence that for every cybercriminal activity that gets squashed in the United States, an offshore competitor takes it — at cheaper rates. And even those rates are falling fast as more players and countries compete for their share of the pie.

In other words, Obama’s proposals are tackling a problem that was already diminishing in the U.S. The bad guys that really cause problems for Americans (and everyone else) are beyond the long arm of the law.

But what of the part about encouraging companies to share information about cyberthreats with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security by offering them “targeted liability protection”? That has to be a good thing, right? Well, the thing is that it’s already happening. In the United States, many company groups already share information — without government involvement — concerning cyberattacks and threats.

Each of these industries is dealing with its own kind of ugly crook, looking to use its specialized expertise to exploit vulnerabilities peculiar to that industry. The Retail Cyber Intelligence Sharing Center has been up and running since last year, when some 30 large retail companies got together and decided to share information on threats with each other. The oil and gas industry are doing something similar through ONG-ISAC (an acronym likely brought to us by the spawn of the same marketing-savvy engineers that coined TCP/IP and PCMCIA). And FS-ISAC does the same thing for the financial services industry, a particularly important sector for Willie Sutton reasons.

It makes sense for companies to form their own cybersafety industry groups to combat their particular threats. Individual companies are also putting great effort into safeguarding their value, though the facts about and nature of their work is often secret.

A bigger issue is that cybercrimes are grossly under-reported and fear of liability is only one part of the problem. Companies just don’t see the governmental resources available to successfully prosecute the kinds of cybercrime they experience, and the track record probably supports that view. Why share information with the government if it won’t help your situation?

There are also hosts of not-so-wacky conspiracy theorists who worry about any governmental involvement with the internet. (Some of them actually think the government is using it to snoop on us!) They also worry that if Congress passes a bill when prompted by a crisis, there are almost always additional consequences: usually giving the government more power than we would like.

Nevertheless, a few things make this part of the proposals much more palatable. First, there are many cybercrimes that aren’t just industry specific. Lots of nasty stuff would simply fall through the cracks if left to individual industries. We might not see innovations and changes that affect all of us, and we not might be as good at communicating new general threats more publicly.

For example, the fastest growing malware targets smartphones. With the right hack, your phone can be used to bug you or see what its camera sees. Not a great sales pitch for a conflicted phone industry. How about cars getting hacked? What about Skype-enabled TVs peering into thousands of homes and the streams being sold on the dark web? We might want companies to share that kind of information with the government — and us — without too much fear of reprisal.

Probably more important than our internet-of-everything gadgets are the power, water, sewage, manufacturing and transportation networks. A surprise, broad attack might put us, if only temporarily, somewhere between now and the Middle Ages. And even though governments are trying hard to protect this infrastructure, we’d probably want any hint of a private breach likely to be correlated with a broad-scale, warfare-like attack shared centrally (sooner rather than later).

In summary, I believe Obama’s proposals are well-intentioned. Information sharing is, on balance, a good thing. They at least start to address a set of problems that will impact the next generation even more than ours and may be the basis for some fundamental research. But I just doubt that they will be very effective in combating cybercrime.

So what is the answer? We know it is a global problem requiring a global solution. We know we need more global cyber capacity to fight cybercrime. International cooperation is critical. Global information sharing is also important — and we are doing some of it. A better understanding of the psychology of how insiders are coaxed, blackmailed, or tricked into sharing access to their computer systems would help organizations defend themselves. Good technology exists and will help, if we use it. Most important is education: Everyone — individuals, employees, companies, and boards of directors — needs to understand the new dangers.

One of the best results of Obama’s initiative may be to put the cybercrime issue a little higher on everyone’s agenda. If it spurs more good guys to learn and focus on the challenges, this second-order effect may have the greater impact.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers