Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1324

February 2, 2015

What Research Tells Us About Making Accurate Predictions

“Prediction is very difficult,” the old chestnut goes, “especially about the future.” And for years, social science agreed. Numerous studies detailed the forecasting failures of even so-called experts. Predicting the future is just too hard, the thinking went; HBR even published an article about how the art of forecasting wasn’t really about prediction at all.

That’s changing, thanks to new research.

We know far more about prediction than we used to, including the fact that some of us are better at it than others. But prediction is also a learned skill, at least in part — it’s something that we can all become better at with practice. And that’s good news for businesses, which have tremendous incentives to predict a myriad of things.

The most famous research on prediction was done by Philip Tetlock of the University of Pennsylvania, and his seminal 2006 book Expert Political Judgment provides crucial background. Tetlock asked a group of pundits and foreign affairs experts to predict geopolitical events, like whether the Soviet Union would disintegrate by 1993. Overall, the “experts” struggled to perform better than “dart-throwing chimps”, and were consistently less accurate than even relatively simple statistical algorithms. This was true of liberals and conservatives, and regardless of professional credentials.

But Tetlock did uncover one style of thinking that seemed to aid prediction. Those who preferred to consider multiple explanations and balance them together before making a prediction performed better than those who relied on a single big idea. Tetlock called the first group foxes and the second group hedgehogs, after an essay by Isaiah Berlin. As Tetlock writes:

The intellectually aggressive hedgehogs knew one big thing and sought, under the banner of parsimony, to expand the explanatory power of that big thing to “cover” new cases; the more eclectic foxes knew many little things and were content to improvise ad hoc solutions to keep pace with a rapidly changing world.

Since the book, Tetlock and several colleagues have been running a series of geopolitical forecasting tournaments (which I’ve dabbled in) to discover what helps people make better predictions. Over the last six months, Tetlock, Barbara Mellers, and several of their Penn colleagues have released three new papers analyzing 150,000 forecasts by 743 participants (all with at least a bachelor’s degree) competing to predict 199 world events. One paper focuses solely on high-performing “super forecasters”; another looks at the entire group; and a third makes the case for forecasting tournaments as a research tool.

The main finding? Prediction isn’t a hopeless enterprise— the tournament participants did far better than blind chance. Think about a prediction with two possible outcomes, like who will win the Super Bowl. If you pick at random, you’ll be wrong half the time. But the best forecasters were consistently able to cut that error rate by more than half. As Tetlock put it to me, “The best forecasters are hovering between the chimp and God.”

Perhaps most notably, top predictors managed to improve over time, and several interventions on the part of the researchers improved accuracy. So the second finding is that it’s possible to get better at prediction, and the research offers some insights into the factors that make a difference.

Intelligence helps. The forecasters in Tetlock’s sample were a smart bunch, and even within that sample those who scored higher on various intelligence tests tended to make more accurate predictions. But intelligence mattered more early on than it did by the end of the tournament. It appears that when you’re entering a new domain and trying to make predictions, intelligence is a big advantage. Later, once everyone has settled in, being smart still helps but not quite as much.

Domain expertise helps, too. Forecasters who scored better on a test of political knowledge tended to make better predictions. If that sounds obvious, remember that Tetlock’s earlier research found little evidence that expertise matters. But while fancy appointments and credentials might not have correlated with good prediction in earlier research, genuine domain expertise does seem to.

Practice improves accuracy. The top-performing “super forecasters” were consistently more accurate, and only became more so over time. A big part of that seems to be that they practiced more, making more predictions and participating more in the tournament’s forums.

Teams consistently outperform individuals. The researchers split forecasters up randomly, so that some made their predictions on their own, while others did so as part of a group. Groups have their own problems and biases, as a recent HBR article explains, so the researchers gave the groups training on how to collaborate effectively. Ultimately, those who were part of a group made more accurate predictions.

Teamwork also helped the super forecasters, who after Year 1 were put on teams with each other. This only improved their accuracy. These super-teams were unique in one other way: as time passed, most teams became more divided in their opinions, as participants became entrenched in their beliefs. By contrast, the super forecaster teams agreed more and more over time.

More open-minded people make better predictions. This harkens back to Tetlock’s earlier distinction between foxes and hedgehogs. Though participants’ self-reported status as “fox” or “hedgehog” didn’t predict accuracy, a commonly used test of open-mindedness did. While some psychologists see open-mindedness as a personality trait that’s static within individuals over time, there is also some evidence that each of us can be more or less open-minded depending on the circumstances.

Training in probability can guard against bias. Some of the forecasters were given training in “probabilistic reasoning,” which basically means they were told to look for data on how similar cases had turned out in the past before trying to predict the future. Humans are surprisingly bad at this, and tend to overestimate the chances that the future will be different than the past. The forecasters who received this training performed better than those who did not. (Interestingly, a smaller group were trained in scenario planning, but this turned out not to be as useful as the training in probabilistic reasoning.)

Rushing produces bad predictions. The longer participants deliberated before making a forecast, the better they did. This was particularly true for those who were working in groups.

Revision leads to better results. This isn’t quite the same thing as open-mindedness, though it’s probably related. Forecasters had the option to go back later on and revise their predictions, in response to new information. Participants who revised their predictions frequently outperformed those who did so less often.

Together these findings represent a major step forward in understanding forecasting. Certainty is the enemy of accurate prediction, and so the unstated prerequisite to forecasting may be admitting that we’re usually bad at it. From there, it’s possible to use a mix of practice and process to improve.

However, these findings don’t speak to one of the central findings of Tetlock’s earlier work: that humans typically made worse predictions than algorithms. Other research has found that one reliable way to boost humans’ forecasting ability is to teach them to defer to statistical models whenever possible. And the “probabilistic training” described above really just involves teaching humans to think like simple algorithms.

You could argue that we’re learning how to make better predictions just in time to be eclipsed in many domains by machines, but the real challenge will be in blending the two. Tetlock’s paper on the merits of forecasting tournaments is also about the value of aggregating the wisdom of the crowd using algorithms. Ultimately, a mix of data and human intelligence is likely to outperform either on its own. The next challenge is finding the right algorithm to put them together.

[image error]

Bringing an Entrepreneurial Mindset to the World’s Failing Systems

A white-haired clergyman leans forward in deep, intent conversation with a lady with a shaved head. To the right, three shiny-suited investment bankers cluster around a banking reform activist in his twenties. Over the course of the evening, 60 people drink red wine and laugh together in the heart of London as they watch an improvisational opera singer sum up the findings of the day: the characteristics of a financial system they would collectively be proud to put their name to.

This is not a surreal scene painted by Salvador Dali, but rather a workshop convened by The Finance Innovation Lab (which Rachel co-founded). The purpose? To capture the energy created by the financial crisis to bring together people who don’t normally talk to one another to design a new financial system. This group knew that unusual solutions were needed — ones that acknowledge the complex interconnected issues that make a failing system so hard to transform.

It can be a daunting task. After all, when a disaster like the financial crisis hits, which problem do you tackle first? Bankers’ bonuses? The failure of legislation? Consumers’ over-reliance on credit cards? It’s clear that a focus on one problem in isolation will be ineffective. To address this complexity there is a growing breed of experts who identify the root causes of problems and set about finding long-term and long lasting solutions. We call them “systempreneurs.”

Systempreneurs focus on addressing some of the largest, most complex challenges of our time — from healthcare to food to politics — by taking on our most entrenched and broken systems. Consider this example: the Future of Fish. To tackle the growing problem of overfishing, they mapped the current supply chain, identified entrepreneurs who are working to fix failing parts of the process, and then supported them to succeed. Another example is the Finance Innovation Lab, which hosted the meeting of unusual suspects mentioned above. To create a system that is more democratic, responsible, and fair, they run an accelerator program that supports new business models that could bring diversity to the financial system. To break down barriers to new entrants they also build coalitions of civil society players to jointly lobby for policy change, recognizing the importance of this stakeholder group to open the door for new financial models to emerge.

The range of activities systempreneurs undertake is broad and heavily dependent on the system they are working on, but there are some common themes in how they get their work done:

1. They create pathways through seemingly paralytic complexity.

Systempreneurs avoid playing the “blame game” and instead point at root causes, highlighting the interconnection between problems. Masters of translation, they use language that connects people to a larger purpose and dissolves sides. They are conveners rather than activists, careful not to align themselves with positions that would harm neutrality, but they often sweep in after public discussion to bring together people who have been disturbed by a debate and turn that energy into action.

Systemprenuers are experts in using quick feedback loops to correct the direction of their work. They acknowledge how delicate new projects, new business models, new strategies feel during the creative process so they create safe spaces where pioneers can meet, test, and refine their ideas over and over before being released into the world.

2. They host “uncomfortable alliances” amongst friends and foes.

Systempreneurs are skilled hosts, bringing together unusual suspects. They identify the right people to bring to a party – carefully considering the individual’s personal qualities, rather than just a job title. They often have limited power themselves and rely on their role as a trusted, neutral, and honest peer to facilitate difficult conversations between people who don’t agree. They never want to be the star of the show, but they aim to cultivate the conditions for meaningful conversations.

They act with humility and welcome people with style, dignity, and gratitude. Systempreneurs appreciate that the process of convening is as important as the content discussed and go to great lengths to empower people who hold potential solutions. They are notorious for their hours spent thoughtfully connecting people by email and know that the secret is to nudge business partners to become friends, encouraging bonds to form in a deeply human way.

3. They create groundswells around new solutions.

As Buckminster Fuller said: “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

Systempreneurs make things happen. They may spend their time:

Supporting entrepreneurs who run businesses that play a particular role in the system. For example, the Civic Foundry, which supports citizens to launch new services to create stronger local communities and economies;

Experimenting with building more effective public services and embedding the most promising results back into incumbent public service systems, as Participle does working on topics like ageing;

Building projects that support the emergence of a new market, as Criterion Institute does by promoting gender lens investing; or

Supporting activists to develop new campaign strategies that can build the capacity of NGO’s, as Campaign Lab does in the U.K.

Many of our current systems — energy, finance, food — were designed at a different point in history when we didn’t consider how limited resources are. All of these systems now need to be redesigned with sustainability in mind. Systempreneurs are playing a critical role, experimenting with how to change these outdated, incumbent systems and strengthening them to fit our current reality, but this small but growing group aren’t yet getting the support they need.

What would boost their chances of success? For starters, we need to find ways to bring the global community of systempreneurs together. They know from their own work that a sense of camaraderie and a place to connect, learn, and share challenges can accelerate success. Yet this group hardly know one another.

Second, we need to get them funding. Systempreneurs are still pretty rare, funders often don’t know about them, and their projects don’t fit the typical funding profile. Their strategies are emergent and the outcomes of their projects cannot be easily predicted making it difficult to assess their effectiveness. But funding is critically needed to get these projects off the ground and to sustain them. We need to continue to build a pipeline of these systems changers. And while systempreneurs often incubate others’ efforts as part of their strategies, there are currently no intensive incubators designed specifically for systempreneurs. This group is so busy running their projects that they rarely have a chance to write down what they’re learning, but we need to capture and share their best practices.

Changing the status quo sometimes feels impossible. Systempreneurs bring a breath of fresh air to that challenge. They create spaces outside of the current system with a “can do” attitude. They dodge the same-old power dynamics and focus on building solutions that work.

[image error]

Priorities for Jumpstarting the U.S. Industrial Economy

The factory floor at Pittsburgh’s Aquion Energy doesn’t look much like the steel mills that once populated this Rust Belt city. Retooled industrial-age machinery sits alongside robotic-manufacturing equipment. Science and engineering professionals work closely with experienced technicians to produce next-generation batteries, not forged metal.

But just as U.S. Steel did in an earlier era of manufacturing, Aquion and innovative firms like it are spearheading economic and employment growth across the country. Spun out of Carnegie Mellon’s materials science research department in 2008, Aquion now employs 130 workers, manufacturing batteries to store electricity generated by intermittent renewable resources. This is the kind of technology—and the type of firm—that will make renewable energy more efficient and more cost-effective.

Aquion is a modern success story for American industry. But in order to create and foster more such firms, we need to recognize that today’s most cutting-edge industrial players are not monolithic; they straddle the lines between manufacturing and services, and production and innovation. Indeed, in a world where globalization and rapid technological changes are the norm, manufacturing, high-tech development, and innovation clearly require a different level of support.

To account for this shift, we believe a more holistic approach is needed to identify the highest-value, most strategically important industries that will drive U.S. competitiveness and growth in the 21st century. We call this super-sector “advanced industries.”

The defining characteristics of companies in this super-sector are a commitment to innovation and a focus on science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) skills in the workforce. The industries that we deemed “advanced” are those with research and development spending that exceeds $450 per worker and a workforce with greater than the U.S. average (20%) of highly intensive STEM occupations. Applying this standard, we identified 50 U.S. industries: 35 advanced manufacturing industries such as automotive and aerospace manufacturing, pharmaceuticals and semiconductors; three energy industries including electric power generation; and 12 service industries, from software design to telecommunications.

Together, these industries have an outsized impact on the U.S. economy. They employ 12.3 million people, or 9% of total U.S. employment, and they generate $2.7 trillion in output annually, adding up to 17% of GDP. Advanced industries are our most globally competitive industries, accounting for a full two-thirds of U.S. exports. And, critically, after years of decline, these industries have led the economic recovery—employment and output growth since the recession have been 1.9 and 2.3 times higher, respectively, than all other industries combined.

Increasing employment in advanced industries means not just more jobs, but better jobs. Average compensation in 2013 across the advanced industries sector was $90,000—nearly double that of workers in other industries. And at a time when wages have been stagnant for many, earnings in advanced industries are increasing—from 1975–2013, inflation-adjusted earnings in this set of industries grew 63%, while earnings in other industries grew only 17 percent.

Still, output and employment are not the only—and perhaps not even the main—contributions of advanced industries. Companies in this sector account for 80 percent of private-sector R&D investment, and so they are disproportionately responsible for the development of disruptive technologies that have affected the entire economy, decreasing transaction costs and waste, and increasing productivity and standards of living. A recent report from the McKinsey Global Institute identified a series of these disruptive technologies—from advanced materials to big data—that the firm projects will transform how we do business and live our lives. Many of these technologies are the direct products of advanced industries, even though their economic impact will radiate throughout a much more diverse set of industries.

Yet, there is a problem. Although the United States maintains world leadership in many advanced industries, that leadership position is eroding. Not only has the national government’s commitment to R&D investment become questionable but the nation’s skills pipeline—particularly for STEM workers—has become glaringly insufficient. At the same time, decades of off-shoring and neglect has left our network of regional high-tech and industrial supplier ecosystems patchy and thin.

So, what should the nation do to defend and expand its advanced industries? The first priority must be a renewed commitment to innovation. Federal investment in basic research cannot continue on its current downward trajectory, and Congress should act to establish something akin to a capital budget for R&D that prevents these critical investments from becoming a political bargaining chip. A recovering economy should also allow firms to reinvest in innovation. Ambition is crucial: Research from McKinsey finds that most low-performing research-intensive U.S. firms are merely “sleepwalking” through their R&D investment decisions, simply maintaining their existing R&D initiatives, unwilling to incur greater risk. New investment decisions should place more value on “open innovation,” which demands multichannel partnerships among firms, universities, and research labs. General Electric provides a good example of how this approach can work: It has partnered with the University of Louisville to create FirstBuild, an open-source factory for building next-generation appliances. Students, researchers, designers, engineers, and programmers gather under one roof to experiment with product concepts and tinker with everything from design to rapid prototyping. In a world in which consumer preferences and technological change are evolving more rapidly than ever, this open innovation model is intended to get new ideas from concept to product more quickly.

Equally important are bold reforms in workforce education and training systems. Despite the recent slack in the job market, signs still point to a stubborn STEM skills gap. To respond, industry must be more involved in shaping business-led, sector-specific regional training programs. Consider the program Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) has launched. According to some estimates, 50 percent of workers in the utility sector will soon be eligible to retire amid acute shortages of trained people to replace them. PG&E responded by developing the PowerPathway program, a partnership with local community college systems in selected U.S. markets. PG&E has co-designed curricula, offered direct instruction, and donated equipment for hands-on training of welders, technicians, and engineers. Through its leadership the company is making the ideal of industry-led regional training consortia real. Targeted government policy could encourage similar initiatives..

Shoring up innovation and skills systems, however, is just the start. We must also strengthen regional ecosystems that can facilitate and enhance industrial performance. These ecosystems improve productivity by gathering in one place cutting-edge suppliers, top-notch service-providers, and crucial innovation and workforce institutions. And yet, years of offshoring and industrial decline have hollowed out many of our manufacturing clusters: Since 1980, the number of metropolitan areas with more than 10% of their workforce in advanced industries has decreased from 59 to just 23. It’s time to replenish the nation’s industrial commons.

One promising strategy is the nascent National Network for Manufacturing Innovation—a federal initiative that offers seed money to chosen consortiums of universities, research organizations, and manufacturers to establish market-oriented research institutes. One recipient, the American Lightweight Materials Manufacturing Innovation Institute (ALMMII), recently opened its doors in Detroit, hoping to draw on the Motor City’s established auto-building ecosystem to accelerate innovation in materials manufacturing. ALMMII was cofounded by Ohio State University, the University of Michigan, and Edison Welding Institute, and counts Alcoa, Boeing, and Chrysler among its partners.

Defining and measuring the location of America’s advanced industries is just one step on the road toward an economic renewal; it’s also likely the easiest. With strong private-sector commitment; smart federal, state and local policy; and lots of collaboration, the nation can move to shore up and expand the advanced industries sector that will be a prerequisite of any rebuild of the U.S. economy.

[image error]

Don’t Ask for New Ideas If You’re Not Ready to Act on Them

Companies that focus on innovation often worry about how to encourage people to contribute ideas. But what happens when you ask people to participate in an innovation effort, and then get flooded with too many suggestions?

That’s the dilemma that one of my clients described not long ago. Faced with a declining market and needing to ramp up growth, the company decided to tap into employees’ collective brainpower. Using an intranet-based crowdsourcing approach, management asked employees to suggest ideas for new products and services, how to increase sales, and how to improve customer satisfaction. A communications campaign also encouraged people to use the platform to comment on and “like” others’ input. Within a few days, hundreds of ideas and discussion threads came in. When the submission period ended, the company had well over a thousand ideas.

Unfortunately, our client hadn’t expected this kind of response, and the small team charged with orchestrating the innovation event was quickly overwhelmed. It took them over a week just to sort the ideas into categories. The summary document that they put together for the senior executive committee was 30 pages long, with demographic and functional breakdowns of where ideas had come from. By the time the committee reviewed and discussed it, almost a month had passed since the end of the crowdsourcing event. It then took a couple more weeks before management finally thanked everyone and announced that senior executives would follow up on specific ideas to pursue.

The good news from this case, of course, is that employees were engaged. People from across the company logged onto the site and contributed ideas. The bad news is that senior management wasn’t prepared for the onslaught of suggestions — and in the absence of timely and effective follow-up, the event didn’t actually produce substantial results. The lack of follow up also potentially made employees more cynical about future innovation efforts.

There are several key lessons that can be derived from this story. The first is that innovation requires more than just coming up with ideas. In fact, ideation may be the easiest part of the process, particularly when new platforms and tools make it easy for people to contribute. Filtering and selecting the right ideas, and then prototyping, pivoting, piloting, and ultimately scaling them, in the midst of competing priorities and limited resources, is much more difficult. So if you’re going to start an innovation effort, think about how to orchestrate the process after you have ideas to work with. Another key lesson is to be more specific about the focus and criteria for submitted ideas. If the parameters are too general, it becomes difficult to sort out the wheat from the chaff.

In another company, for example, management knew, based on past experience, that an innovation challenge could generate lots of ideas that were all over the map — so they needed to be prepared. First they focused the challenge on several specific operational processes, and made it clear what would need to go into a successful submission. They also selected a dozen high-potential managers from across the business to be “idea champions” and put them through training about how to help employees sharpen their inputs, how to sort ideas into categories, how to rank the ideas in terms of impact and achievability, and how to provide feedback to contributors.

Throughout the challenge, the hundreds of ideas that came in were quickly divided amongst the champions, who used common criteria to sort and select those that could create the most business value. By the end of the challenge period, the champions had identified a small portfolio of ideas that were worth pursuing. Each champion was then paired with a more senior manager to create a plan for testing, prototyping, and driving the idea forward (or failing fast). In this way, everyone in the organization not only knew the outcome of the challenge very quickly, but also understood that ideation was only the beginning of a much longer process.

The final lesson here is that real innovation requires clear communication and careful calibration of people’s expectations. With the right encouragement, people will submit ideas. But they’ll want to know that their “brilliant” ideas are given full consideration — and if they’re not chosen or implemented, they’ll want to know why. Managing these messages in a personalized way, when hundreds of people are involved, can be logistically challenging. But without this kind of feedback, ideation can be demoralizing, sort of like dropping an idea into a suggestion box and then being ignored. To counter this, the idea champions mentioned above also had the responsibility of providing quick “thank you’s” and feedback to people who sent in ideas. And for the ideas that were selected, the champions encouraged the originators to become part of the implementation team.

Getting lots of ideas is a key part of innovation and a great way to engage employees. But unless you have a process to manage these ideas, you run the risk of wasting not only the content, but also the good will that comes with it.

[image error]

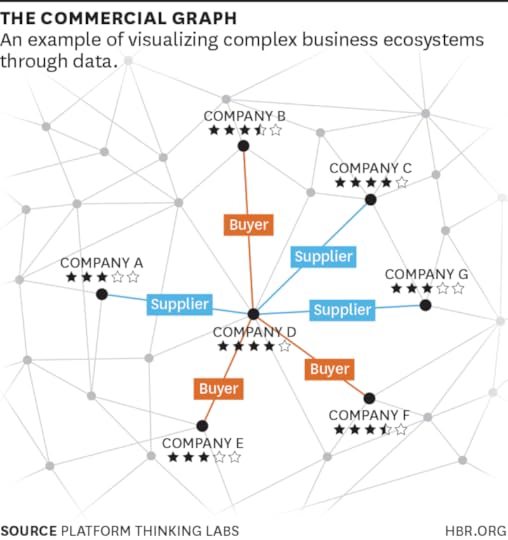

The Rise of Social Graphs for Businesses

If you’re a savvy social media user then you’ve already figured out that the knowledge a tool like Facebook is able to gather about your social connections is not only valuable to you. For you, Facebook’s ability to depict your network of friends and the varying strengths of those relationships supports all your mutual information sharing. For others — third parties — this “social graph” makes it possible to make personalized recommendations to you, and everyone else. For example, TripAdvisor leverages Facebook’s social graph to ensure that, when you are looking for reviews of hotels, restaurants, and so forth, any reviews posted by people you know appear right at the top.

For the social network companies, it didn’t take long to realize that the latter form of value creation should be the real focus of their business models. Early ventures like MySpace primarily focused on the social activity among their account holders, working to provide better tools to help them manage their relationships. Today’s social networks see social tools not as their end product but as a means for acquiring data. Facebook, in particular, saw the big opportunity in the “information exhaust” produced by all that user activity to produce a higher-level intelligence layer that would be useful to other businesses. Having graphed its users’ relationships and interactions, it could offer anyone else interested in those users the insight to reach them with highly targeted services.

Let’s say, however, that you are a business that would like to see that kind of social graph of the interactions among enterprises and not just individuals – perhaps because you sell to business customers, or perhaps because of your need to deal with suppliers. All businesses operate within their own networks of vendors, partners, clients, competitors, and other entities — the favored term these days is to talk of their “ecosystems.” Wouldn’t that be a valuable space to map?

This is the next step in the evolution of the social graph — let’s call it the emergence of the “commercial graph” — and it is happening now. Commercial graphs depict relationships between businesses, based on their actual interactions as they are captured digitally. And they support highly relevant information sharing, analogous to the TripAdvisor example above. Commercial graphs will help businesses manage their own partner relationships better, and also help third parties to those ecosystems understand them and spot ways to make targeted offers to those within them.

Insight Center

Making Money with Digital Business Models

Sponsored by Accenture

What successful companies are doing right

Of course, businesses already use supplier and customer relationship management tools to manage their commercial relationships. We might see these as analogous to the MySpace era of social networks. The tools help individual businesses manage their interactions, but they do not generate a higher layer of intelligence to aid with new business development or new supplier discovery. They offer no visibility into another enterprise’s connections with other businesses, or its reputation based on a track record in dealing with others. By adding this new level of insight, commercial graphs will allow businesses to connect far more efficiently.

Commercial graphs visually display three things: the companies in an ecosystem, the relationships among them, and the reputations they have earned through their mutual dealings. As with social graphs, the depiction of the nature and strength of relationships between companies is based on actual interaction data. Unlike with a social graph, a company does not have to explicitly opt to join a network for it to be included in a commercial graph. Instead, its connections to others can often be derived from interactions recorded by other companies.

The commercial graph’s ability to depict each party’s earned reputation is its main source of value. A company’s reputation score is based on its performance across multiple business relationships. Think of TripAdvisor and Yelp, both of which have by now gathered input on so many different experiences with a given hotel or restaurant that they can present reputation scores, and indeed generate an entire reputation layer for hotels and restaurants. Importantly, however, commercial graphs don’t rely on explicitly stated (and subjective) opinions submitted through social mechanism. Instead, they rely on implicit indicators of quality and performance, which can be objectively observed in the business interactions between companies, and consistently weighted in the scoring. Universally disliked experiences such as slow turnaround, late delivery, or defaults on payments drive reputation scores lower.

When aggregated across an industry, these data add up to commercial graphs which can help companies assess the performance of their business relationships vis a vis industry averages. They help managers identify new partners and suppliers who are likely to outperform current ones. And they help companies benchmark their own performance against peers.

Let’s turn now to the opportunity this represents for the first developer of the commercial graph — the equivalent of Facebook — for a given industry. That business becomes a powerful platform provider, and establishes a strong, sustainable advantage. Yes, the software can be easily replicated, and better user experience and easy data portability can potentially pull users away to a new platform provider. But with the creation of a commercial graph, powerful network effects kick in. Because the value of the tool rises for everyone with every addition of a new participant, there is a shared interest in converging on one platform rather than allowing two to coexist.

Thus we see the various software providers that already provide the tools to manage business interactions (like procurement and invoicing) moving rapidly to capitalize on this opportunity. Companies like TradeShift, Procurify and SPS Commerce already capture interaction data through their workflow management tools. Much like Facebook, they are recognizing that the software is not the end product, and instead seeing it as a means for acquiring the data to produce valuable commercial graphs.

These software as a service (SAAS) providers are powering the first few instances of the commercial graph today. But they are not the only ones eyeing this new opportunity. LinkedIn’s Sales Navigator shows the company’s intent to move beyond connecting professionals to connecting companies. Payment startups like Square and cash-flow management startups like Pulse App also capture transaction data that can help them map out commercial graphs for small businesses.

Keep watching this space. In a world where commerce flows on networks, and business people increasingly devise strategies with an eye to their broader ecosystems, the rise of commercial graphs will be rapid. We need them to create the layer of intelligence for more efficient market interactions and healthy business relationships.

[image error]

To Stay Focused, Manage Your Emotions

A leader’s most precious resource is not their time. It’s their focused attention. Time merely passes, while focused attention makes things happen. When we’re able to gather and direct our attention toward a particular task or interaction, we can have a significant impact in a minimal amount of time. But when we’re unable to bring our attention to bear on the work at hand, all the time in the world is insufficient. So what are the implications of this for leaders?

Leaders must recognize that it’s essential to work at enhancing their ability to direct their attention and minimize unhelpful distractions, and one of the most important steps in this process is managing emotions. Psychologist Victor Johnston describes emotions as “discriminant hedonic amplifiers,” meaning that they boost various signals in our mental landscape, drawing our attention toward certain issues and events and away from others. In other words, emotions are attention magnets.

Consequently, awareness and regulation of our emotions are central to the productive use of our attention. Here are some practical steps leaders can take.

Build Capacity. We can expand our attentive capacity though a commitment to practices such as meditation, journaling, time in nature, regular physical activity, and good sleep hygiene. All of these activities support our ability to direct our focus, filter out distractions, and manage our emotions, and we can often realize their benefits with a modest investment of time. Recent research indicates that meditating for just a few minutes a day, spending just one hour a week in nature, or jotting down a few reflective notes in the evening has a noticeable impact on well-being. My experience as a coach suggests that these benefits extend to leaders’ effectiveness. The key is a consistent commitment to each daily or weekly practice.

While these activities are often enjoyable in themselves, they aren’t indulgences–they’re investments in our ability to operate at peak effectiveness. High-performing professionals often enjoy success early in their careers by virtue of their ability to forego activities like this–they cut back on sleep or go without exercise for extended periods of time. But while those sacrifices temporarily expand our capacity for throughput, they actually diminish our capacity for focused attention. And while more senior leaders like my clients continue to work hard, what allows them to add value isn’t the extra hours spent working, but rather the quality of their focused attention while they’re at work.

Plug Leaks. Attention is finite, and our ability to focus in the moment is severely limited. Because distractions can fatally undermine effective leadership, it’s critical to avoid “attention leaks.” As I wrote a few months ago, “The functions on our phones and other devices that beep, blink and thrust red numbers in our faces are designed to capture our attention and create a sense of urgency… But how often are any of these interruptions truly urgent? Almost never. Turn them off.”

Another attention-destroying practice is what we’ve come to call “multi-tasking,” an utterly misnamed concept. While insignificant tasks requiring minimal cognitive effort can be performed in parallel, the truly meaningful work through which most leaders add value–one-on-one conversations, facilitation or decision-making in meetings, and creative thought and ideation–require a much more intense level of focus. Multi-tasking in those environments inevitably results in significant inefficiencies as we switch contexts and lose focus before returning to a deeper level of thought.

Create Space. Leaders typically face intense demands on their time (in part because everyone wants their attention), and if they’re not careful they can find themselves booked nonstop for days on end. It’s important to maintain some open space in the calendar, on a weekly or even daily basis, which allows for more creative thinking and helps replenish our stores of attention.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Getting the Right Work Done

Leadership & Managing People Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

This inevitably involves disappointing people, all of whom believe their issue is worthy of the leader’s time, but productive leaders realize that they can’t meet all of these requests and must ignore many of them. Here leaders require help from their senior team, family, and friends, and–perhaps most importantly–their executive assistants. People in these roles are uniquely positioned to help leaders protect open space on their calendars, and they’re uniquely positioned to undermine that process if they don’t understand this responsibility.

One final thought: If you’re a leader sitting in a meeting that’s not worth your focused attention, then you’re serving a theatrical function. Sometimes this makes sense. There’s a place for organizational theater. But more often the whole organization is suffering because your most precious resource is being wasted. Let the people who organized the meeting know that you’ll attend in the future when you’re needed, excuse yourself, and get on with your day. And if it’s your meeting, then you may well be wasting everyone’s time and attention–they may all be there in a theatrical function because they’re deferring to your authority. Have a candid conversation with a trusted ally, and get some feedback on the utility of your meetings.

Thanks to Chris Oestereich for a timely reminder on the importance of open space.

[image error]

January 30, 2015

Why the Keystone Pipeline Is the Wrong U.S. Energy Debate

The Keystone XL — a proposed addition to a network of pipelines running from the Canadian oil sands to refineries in Texas — has become the political football of the moment. It was the first issue that Sen. Joni Ernst addressed in her response to last week’s State of the Union address, and yesterday the Senate passed a bill forcing its approval. President Obama, however, has said he’ll veto Keystone, and he should.

Putting aside the divisive politics, let’s consider the pipeline on its merits, as an investment choice for the United States. In the short run, with oil at $50 per barrel, Keystone will connect refineries to oil that may be unprofitable to extract. In the long run, as the world turns away from fossil fuels aggressively, the pipeline will be moot — a relic of the past.

Either way it’s a poor investment.

First, the short-run economics. They’re not good. To feed the 90-million-barrel-a-day beast that is the global economy, we need more than just OPEC. The “unconventional” sources of oil, like fracked shale oil from North Dakota and the Canadian oil sands, help fill a large gap left by the production of conventional crude, which has, for years, flatlined at around 70 million barrels per day.

But “unconventional” also means expensive — squeezing oil out of uncooperative mud or tight rock formations is an energy, water and capital-intensive process. Oil sands require up to 3 barrels of water for every barrel of oil produced. And consider the “energy return on investment” — that is, how much useful energy you get for every unit of energy put in. Globally, oil and gas sites attain an average ratio of about 20 to 1, while oil sands efficiency can range down to below 2 to 1.

This resource intensity costs money and time. So at today’s (surprise) $50 per barrel price, most of the oil production sites in the world are facing serious economic challenges. When prices rise again — and they will — oil sands will be more profitable. But even then, these unconventional sources will still face two large and existential challenges: climate change and the fast-improving economics of renewable energy.

A tipping point on global action on climate change is approaching. For years, the likely suspects (environmental non-profits, well-known green leaders like Al Gore, and a handful of progressive business executives) have pushed for cuts in carbon emissions and a change in how we produce and use energy. But now an unlikely group of new voices — from the Pope to bankers and former U.S. Treasury Secretaries Hank Paulson, Robert Rubin and, most recently, Larry Summers — are calling for aggressive policies, such as a tax on carbon. The World Bank has also gathered the signatures of 1,000 multinationals and 70 countries in support of a price on carbon. These voices are not going unheeded: carbon taxes and trading systems are already in operation around the world, from British Columbia to China.

The call for regulations and public pressure on fossil fuels has intensified because the math and physics of climate change tell a clear story: We cannot burn all the reserves of fossil fuels that humanity has already identified … not even a third of them. A new study in Nature magazine overlays this harsh reality with the actual location of reserves. It’s not a pretty picture for oil-dependent regions like Russia and, yes, Canada. To keep the world from warming more than the globally-agreed upon 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit), the study says, “85% of the 48 billion barrels of reserves” in Canada will have to “remain unburnable.” So why would we build a pipeline to a resource that will most likely go unused?

The second, more long-term threat to the fuels of the past is arriving in the form of cheap renewables. Technically speaking, in the U.S., renewable energy does not replace oil (since oil has almost no role making electricity), but a shift to clean energy reduces demand for gas and coal — and a cleaner grid makes much more attractive the hybrid and electric fleets that do reduce oil demand. Cheaper renewables matter and they’re already here. Renewable energy is winning: in the U.S., half of the new energy generating capacity being put on the grid comes from renewable sources. In total, the world spent $310 billion on clean energy last year.

Investors and energy utilities on both sides of the Atlantic are waking up to these radically changing economics. Barclays bank downgraded all U.S. electric utilities, saying they were not a great investment as solar prices fall. The leading utilities are trying to pivot their businesses in a big way. In the U.S., NRG announced aggressive goals, including cutting carbon 90% by 2050. German utility E.On went further and spun off its fossil-fuel burning assets to concentrate on renewables.

While companies are recognizing that tackling climate change is getting much cheaper, in the political maelstrom around Keystone, Washington is ignoring the ample evidence. The supporters of the pipeline have touted the economic benefits of thousands of construction jobs. The critics have pointed out that those are temporary positions and only 35 jobs will remain after a few years. Both estimates are probably right — that’s what infrastructure investments look like. So those job counts are beside the point. Many other infrastructure choices we could make would create jobs — roads, bridges, schools, or a new energy grid.

So the real question is, what kind of infrastructure do we want to build? Do we approach every project as a one-off way to create some temporary jobs, or do we have a strategy in place that improves our long-term competitiveness? Imagine if we were thinking today of building our education infrastructure by investing in blackboards and slide rules. Instead, many school districts, including my son’s, are wisely handing out Chromebooks and iPads to every child.

Similarly, why would we invest in yesterday’s energy technologies when we have smarter options? Our investment choices should make our country more resilient, healthy, and prosperous. By that logic, the pipeline is a bad investment choice. That’s just simple arithmetic and economics. Given the challenging future facing unconventional, expensive fossil fuels, the Keystone XL is literally a pipeline to nowhere.

[image error]

How to Really Listen to Your Employees

Let’s face it: strong leaders tend to be characterized by their strong opinions, decisive action, and take-no-prisoners attitude. These are important traits, but it’s equally important for managers to stand down and listen up. Yet many leaders struggle to do this, in part because they’ve become more accustomed to speaking than listening. So, how can you develop this muscle? What are the barriers to good listening and how do you overcome them?

What the Experts Say

“As a leader, you need to have a strong voice and you need to know when it’s time to listen,” says Amy Jen Su, co-owner of Paravis Partners, an executive training and coaching firm. “A real conversation is a two-way dialogue; it requires both parts.” Christine Riordan, a leadership coach and president-elect of Adelphi University, agrees: “To be able to motivate and inspire others, you need to learn how to listen in both individual meetings and at the group level.” Fortunately, there are concrete ways to improve this important skill. Both Su and Riordan agree that the key is to start with the right mindset.

Make it a priority

First, you need the will. “You have to put it at the top of your list and acknowledge it’s a skill that’s important in your role as a leader. It has to be an active decision,” says Riordan. And to get over a need to talk or interject, adapt a mindset that will allow you to hear what’s being shared. If you believe you have all the answers, you simply have no reason to listen to others. Some of Su’s strongest clients build their listening skills by focusing on co-creation. “They recognize their own intellect, but they also recognize that their colleagues are equally smart and have something of value to say.”

Know thyself

It’s important to understand what’s holding you back. Are you a naturally good listener or do you have a more assertive personality? “There are personality traits that lend themselves to more empathic listening,” explains Riordan. “If you’re extroverted and conversational, you’re usually the one doing most of the talking.” Su had a client who was strong, passionate, and innovative. The downside to these fiery traits was that he was, as his subordinates and teammates described him, a “bull in a china shop” when it came to listening. To make matters worse, he was totally unaware of it. To break him of this bad habit, Su instructed him to use a “listening stick.” He started at home with his wife (who was thrilled at the prospect of his transformation into a better listener). Every time he wanted to talk during dinner, he had to wait for his wife to pass the listening stick. This physical cue finally helped him improve.

When assessing your own habits, also take your upbringing into account. “Some of us may have had early experiences in life where we were taught to be listeners instead of speakers, deferring to others. Some of us were taught that it was weak to listen, that we need to speak up,” says Su. Without first recognizing the influence of your early years, it’s difficult to change.

Further Reading

The Discipline of Listening

Communication Article

Ram Charan

How to master this essential leadership skill.

Save

Share

Get rid of distractions

When your attention is elsewhere during a conversation, you risk sending a message that the speaker and their message are unimportant. “We assume being on our iPhone or tablet isn’t a big deal, but when you speak to the people who work for those leaders, it has a really negative impact,” explains Su. And realistically, splitting your attention in such a way prevents you from getting the full picture; after all, you can’t pick up on facial expressions if your gaze is down at your phone. Demonstrate that you are listening by silencing phones, darkening your desktop monitor, and putting away anything that has the potential to distract you from the conversation at hand.

Look for nonverbal cues

Communication is much more than the words spoken. As Riordan says, “It’s not just content, it’s context, too.” People communicate in a myriad of ways and many of them are nonverbal. “In a conversation, people might say one thing but their face and body are saying the opposite.” Don’t let these cues pass by unaddressed. Acknowledge the information you’re receiving with questions like, “You seem excited about this, can you tell me more?” or “I get the sense that this upsets you, is there anything you need to share?”

Control your reactions

But don’t just focus on their body language. Control yours too. There are times this is challenging, either because we disagree strongly or because the news is upsetting. Riordan has seen leaders overreact to information, typically by snapping or very vocally disagreeing with the bearer before the message has been fully delivered–particularly when the news is bad. Regardless of the information you receive, it’s just as important to maintain control over your body language as it is to notice theirs. Practice sitting still and maintaining silence. Riordan advises us to avoid the rush to react or contradict.

Validate and verify

Leaders who are effective listeners validate and ask clarifying questions. “They don’t make assumptions. They drill down into the content of the conversation and verify what they’ve heard,” explains Riordan. They typically ask questions like, “Here’s what I thought you said, is that correct?” To be clear, Riordan stresses that you don’t have to agree with what’s being said. You can acknowledge and even express gratitude for the information, regardless of how you feel about it. Always close the talk with a summary of points heard and next steps.

Principles to Remember

Do:

Take an honest look at both your good and bad habits

Clear out all distractions that might draw your attention away from the person in front of you

Ask clarifying questions and repeat back what you heard

Don’t

Assume you know all of the answers — allow for the possibility that others have valuable information to share

Overlook nonverbal cues — they often reveal what a person is really thinking

React emotionally to what is being said — acknowledge the information even if you don’t agree

Case Study #1: Create an environment conducive to listening

In 2004, Mike Colwell was promoted to manage a team of five directors, all of whom he’d worked with previously. He made it a priority to bring them together in one cohesive unit. One by one, they would each come in for a meeting with him to discuss the usual day-to-day news, and any other issues his managers wanted to bring to his attention. But it wasn’t long before he noticed things just weren’t flowing smoothly.

“I had five very strong leaders, but they all communicated differently and seemed to be giving me different information depending on whether they thought it was important or not,” says Mike. Worse yet, it seemed that they weren’t bringing small issues to his attention before they became big problems.

After some consideration, Mike realized there were two elements that contributed to the problem. First, he wasn’t creating an environment that was conducive to listening. When his managers came in, the various electronics on his desk created distractions and interruptions. His monitor was constantly alerting him to new messages or emails. “I realized I had to eliminate the distractions so I removed everything from my desktop, including my phone, and turned off my monitor,” says Colwell. “The dark monitor became a reminder for me; every time my eyes wandered to it, it was a cue to pay attention.”

Next, Mike decided to follow a specific agenda for each individual meeting. Every time they came in, his directors knew they would be expected to discuss all nine key elements of the business. Mike also told them that he didn’t want to do the talking; he wanted them to take the floor and give him the information freely. Not only did Mike’s tactics give his team the satisfaction of feeling heard and understood; the quality of information he received improved drastically.

Case Study #2: Don’t let personality traits get in the way

In 2006, Cameron Herold was proud of where his company, 1-800-GOT-JUNK?, was headed. The company, which was started in 1989, had $60 million in revenue and employed over 200 people at its head office. This was a promising position for the growing venture, but dissension soon broke out on the leadership team over how to grow. Their VP of Finance kept warning them not to spend in a few key ways. “He cautioned us about our growth, but we never really listened,” says Cameron, who was the COO at the time.

The problem? “Our VP was quiet. Almost meek,” he says. He was an introvert, and his manner of speaking was subservient. In contrast, Cameron and the CEO were both dominant and expressive. “Because he wasn’t right in our face about it, pushing us, we let his words go in one ear and out the other.” As a result, the VP’s warnings went unheeded and the company expanded too fast and ran out of cash. They faced significant financial trouble, which made it harder to weather the economic downturn in 2009.

Luckily the company survived, and Cameron was able to change his ways. The experience taught him to spot the disappointment in someone’s face when they speak yet don’t feel heard. “It’s important to look for it, to know if I’ve been truly listening to them or simply placating them,” he says. “And as a leadership team, we learned that we had to listen and pay attention to everyone, regardless of their communication style.”

[image error]

The Decline of the Rural American Hospital and How to Reverse It

There are two kinds of health-care innovation: more-for-more and more-for-less.

The American health-care system exemplifies the first kind, offering more and more value at higher and higher costs. If you have the money and can travel, the U.S. is the place to take advantage of the latest innovations such as proton-beam cancer-radiation therapy, for which the equipment and facilities cost about $1 billion.

Despite these high-cost innovations (American consumers spend more on health care than their counterparts anywhere else), U.S. life expectancy ranks 34th in the world, and infant mortality ranks 27th. It’s no wonder that patients, politicians, third-party payers, hospitals, and providers are calling for health-care models and technologies that deliver more for less.

In contrast, India is widely recognized for the second kind. Providers such as Aravind Eye Hospital, Narayana Health, and Apollo Hospitals offer high-quality outcomes at a tenth of U.S. prices to vast numbers of patients who would otherwise have no access to care. The driving forces for this, of course, are India’s economy, its scarcity of providers, and its large population of poor consumers; the U.S. just has not been desperate enough to foster Indian-style health-care innovation.

There are, however, isolated pockets of extreme need in rural U.S. communities, where conditions are ripe for more-for-less innovation. These communities are facing a health-care crisis because economic and regulatory pressures are pushing providers to cluster in urban centers. The consequences are dire. Last year, 13 rural hospitals closed, and a tidal wave of closures is expected over the next few years. These hospitals are caught in a vicious cycle: Rural patients with serious health problems are traveling to cities to seek care from medical specialists, causing revenue declines at rural hospitals and clinics, which respond by downsizing and offering fewer services, causing more patients to seek care in major urban centers.

To help break this cycle, some rural hospitals and clinics are adopting an innovation that allows them to access specialists virtually, for a lot less money. Consulting with specialists via video conferencing may not sound like a dramatic innovation, in comparison with proton-beam radiation therapy, but it is! It redistributes access and makes use of resources in new ways. Virtual consultations, supported by sophisticated diagnostic instruments, high-resolution imaging, and data security, are at the heart of a reconceptualization of rural hospitals (and eventually urban clinics and hospitals as well) because they provide access to higher-quality care at much lower costs. Our research — we’ve interviewed executives and care providers at numerous health-care organizations and written a case study on telemedicine — suggests that telemedicine promises to upend health-care markets where supply and demand are out of balance.

Adam (his name and other details have been changed for privacy), a long-term HIV patient in rural Arizona, illustrates the effect. Prior to the implementation of a virtual-consultation program serving his local clinic in Kingman, he had two unattractive options: see his local provider, who wasn’t an HIV specialist, or travel more than two hours to Flagstaff on one of the HIV clinic days offered in a facility there. Neither was compelling enough for him to seek treatment. He didn’t have reliable transportation, and he was uncomfortable sitting in a waiting room on HIV day, because doing so would publicly announce his health status. Consequently, Adam became one of the thousands of rural patients who have given up on the health-care system.

Then North Country HealthCare developed a telemedicine program that allowed him to visit his local clinic and connect virtually with an experienced HIV specialist in Flagstaff. The telemedicine station at his clinic, supported by an onsite technician, allows the specialist to check blood pressure, view skin lesions, check for mouth sores, conduct an ear exam, watch a live ultrasound exam if needed, and talk with Adam about his personal health practices. The specialist, a nurse practitioner, has been able to triple the number of patients she sees because telemedicine reduces the time she spends driving to satellite clinics. She strengthens her patient relationships through in-person visits every few months, but these are now supported by more frequent meetings and telemedicine exams.

Telemedicine is a win-win for Adam and the local clinic. Adam saves time and money because he doesn’t have to travel to Flagstaff, and the Kingman clinic keeps Adam as a patient (and the revenue he brings in). Most important: Adam, who had opted out of the system, is now receiving the care he would have missed.

This story is not unique. Because of its telemedicine partnerships, a 25-bed hospital in La Grande, Oregon (population 13,000), has virtual access to 19 specialties, including pulmonology, cardiology, dermatology, rheumatology, neurology, and oncology. The same is true for close to 300,000 rural veterans who tap into the extensive telemedicine network maintained by the VA. Mayo Clinic in Arizona, applying a hub-and-spokes telemedicine model to provide neurological consulting for emergency treatment of stroke patients at 16 rural hospitals in four states, has reduced the need for air and ground ambulance transfers and significantly improved patient outcomes.

Administrators at rural hospitals and clinics are discovering that virtual consultations have an enormous influence on their facilities’ reputations. Knowing they can access specialists without making long drives to urban centers, rural patients regain confidence in the ability of their local hospitals to offer high-quality, specialized care. This enhances the hospitals’ ability to retain patients (and revenue), curtailing what for many has been a death spiral. After Lincoln Hospital in Davenport, Washington, started its telemedicine program, admissions grew by 25% and transfers to urban hospitals decreased by 21%, and the increased patient load produced well over $1 million in additional annual revenue for the hospital.

A few barriers stand in the way of widespread implementation of telemedicine: In most states, virtual consultations can be reimbursed only for rural patients, which means telemedicine isn’t available for the urban poor. And U.S. patient-privacy laws require sophisticated data encryption that rules out some of the simpler applications used in other countries — in Australia, or example, a doctor can be reimbursed for a consultation over Skype.

In addition, some of the providers we interviewed complained about problems with the technology. In Phantom Ranch, a remote location in the bottom of the Grand Canyon, paramedics feel that fiddling around to get the right satellite link is low priority when they are attending to time-sensitive emergencies.

Perhaps the most important barrier is acceptance. Not all primary care physicians see a need for the kind of additional expert help telemedicine can provide. Patients, too, are sometimes resistant: Indian Health Services, one of the largest users of telemedicine in the United States, has had difficulties getting older individuals in the Navajo nation, for example, to use the service because of religious concerns regarding the taking of photographs.

Despite these barriers, the innovation will spread as it matures. We expect that many of the telemedicine services that patients in rural America find invaluable will soon be demanded by urbanites. Who wants to drive an hour across town to see a specialist in a large medical center? Why not have a virtual visit in your local clinic — or, better yet, from your own home?

[image error]

Google Glass Failed Because It Just Wasn’t Cool

It was hailed as the greatest product since the iPod … the wheel … the car. Instead, it turned out to be more like New Coke or the Segway. So what went wrong with Google Glass?

It’s not that Google Glass looked absurd — people wear silly fashions every day. It’s not that it was overpriced — people collect luxury watches and handbags every day, too. Google Glass’s failure was a story of a visionary product utterly failing to be cool.

Cool is not trivial. As Apple, Warby Parker, Net a Porter, and Shinola all know: Cool is perhaps the crucial factor in the success of new products. Cool isn’t something that is easily calculated by data-driven corporobots or profit-maximizing algorithms. Cool is not an equation. It’s mysterious, ineffable. An art, not a science. Which makes it hard for an engineering behemoth like Google to master. Cool cannot be engineered.

And yet that’s precisely what Google tried to do. It put Google Glass on models during Fashion Week, in advertorials in fashion magazines, in the hands of fashion “influencers.” Why? To engineer hype, excitement, adulation … to manufacture “buzz.” Aha! Textbook digital strategy! Genius! How could it fail?!

Actually: how could it succeed? All of that desperate maneuvering served to reinforce the obvious: that Google Glass was so uncool, the only thing Google could do was try to force it to be cool. It’s like the sad guy at the bar who shows up one day in a Ferrari and a shiny $3,000 suit … all of which only makes him less attractive. In short, Google made a fatal error of post-modern marketing: it attempted to buy cool through the not-so-subtle techniques of influence, persuasion, and manufactured buzz. But if you have to buy cool, it’s probably a reliable signal that you’re totally, hopelessly uncool. Every organization, or leader, in history that has tried to buy their way to cool has learned the hard way: cool has to be earned.

So how does one earn cool? At its most fundamental, cool is about liberation. Jazz liberates music from the suffocating formalism of classicism. Disco liberates people to stop standing around and looking awkwardly at one another and get down until the sun comes up. Great books are cool – and often banned – because they liberate people from established ideas and norms. Biker jackets are cool, not because they represent two-wheeled transport, but because they represent freedom from the tedium of spreadsheets and minivans (which in turn are just representations of other things). Things stop being cool once they stop liberating; think of a revelatory Jimi Hendrix guitar solo juxtaposed with any run-of-the-mill shred-fest by some ’80s hair band. It’s so important, I’ll say it again: Cool liberates. What, exactly, did Google Glass liberate people to do – spend more time on Facebook?

Back up for a moment. What makes rock stars so enviable? It isn’t just the money, fame, and hangers-on. Even bankers have those (and no one wants to be a banker … not even bankers). Nope. What makes rock stars so enviable, and what we really mean when we describe someone as a “rock star,” is that they don’t give a damn — about the drudgery of bosses, bills, backbiting, invoices, accounts receivable, performance reports, deadlines, conference call and all the hellish paraphernalia of a prosperous post-modern life. (I’m willing to bet that the Ramones didn’t give a damn about conference calls.) In short, rock stars are freer than the rest of us, in a fundamental way: they’re free to pursue their their passion and not to waste their lives on what doesn’t matter. They’re free to be individuals.

But Google Glass did not liberate people. It didn’t make them freer. It didn’t help them become individuals. Why did people roll their eyes at (or even punch) people wearing Google Glass? Not just because it looked ridiculous. Because it promised to be just another way to rob people of their individuality. It threatened them with yet another demand for mind-numbing conformity. Better not speak out! Better not express yourself! Maybe the Glasshole’s recording you!

Patching into another three hours of meetings in your self-driving car on your augmented reality headset so you can spend even more time getting yelled at by your boss? That’s not freedom. That’s repression. Self-chosen. Which, of course, is the most pernicious kind.

There’s a now-old joke: Google Glass lets you step outside … to check the weather. But that joke contains a profound truth. Google Glass simply reinforced the status quo.

The painful truth is that there wasn’t enough rebellion in Google Glass. Google might have thought there was. But me, you, and probably even the guy in the $3,000 suit at the bar knew: it wasn’t revolutionary, socially, economically, culturally revolutionary … it was just more of the same suffocating, shoulder-shrugging, yawn-inducing conformity. And nothing conformist is ever, ever cool.

Let me put it this way. The average American has a veritable gadget cornucopia at his fingertips. But he’s poorer, more unhappy, more anxious, and less mobile than he was 30 short years ago. In short, technology hasn’t liberated people. It might just be thwarting them, in significant ways, from the lives they should be living.

And that’s why we love things that are cool. Because they give us a tiny taste of liberation. A small caress of freedom. A little jab of individuality. All that’s always in stuff that’s cool. That’s why it doesn’t just titillate and amuse us … but thrills, excites, and exhilarates us. What is truly cool challenges us. To imagine the world as it should be. And then make our lives the levers of those worlds.

Here’s the lesson: If you want to make something cool, you’re going to have to make people the rock stars of their own lives.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers