Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1321

February 10, 2015

When Investors Want to Know How You Treat People

How much time do you spend enhancing your organizational culture, leadership pipeline, and employer brand? How well are those efforts reported to your investors? If you’re typical, then your culture, leadership, and employment brand are described vaguely or not at all. That may be changing as “enhanced” or “integrated” reporting gains momentum across the globe. It augers great benefits to leaders that have a strong human capital story to tell with numbers, and poses dilemmas for those not prepared to measure their human capital and organizational capability more precisely.

The idea of revealing human capital data in annual reports is not new and the reports won’t change overnight; however there is now an unmistakeable trend towards enhanced reporting. This is no fringe movement. The big player in the U.S. is the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) led by Michael Bloomberg and former SEC chair Mary Shapiro; with the notable presence of ex-FASB chair Robert Herz on their board. Outside the U.S., the movement to enhanced reporting is led by the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), which is endorsed by regulatory heavy weight Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England. Other important groups like GRI are also playing a role.

Largely unnoticed in the U.S., the IIRC has had substantial impact internationally. Japan’s Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry published The Ito Review in 2014 which points to integrated reporting as a way to combat “short-termism.” Singapore’s Accountancy Commission, a statutory body which promotes accounting excellence has produced an integrated report. Australia’s main CFO forum, the G100, has shown interest in the topic and even published a paper offering broad support for integrated reporting, arguing that “corporate reporting reform is underway and CFOs should seize the opportunity to drive the reporting agenda.” A Brazilian Stock Exchange BM&FBOVESPA has encouraged listed companies to produce integrated reports. In South Africa, integrated reporting is a requirement for listed companies on an apply or explain basis and the European Commission passed legislation that will require around 6,000 European entities to disclose on non-financial and diversity information.

Why the interest? Both SASB and the IIRC are promoting improved reporting of non-financial information so as to give a better, more holistic, picture of how the organization creates value. In a world where value increasingly pivots on elements that are not traditional financial measures, investors and regulators realize they need better insights.

Some of the most important insights will come from human capital reporting. The CFO of Halogen Software, Pete Low, said “Given the strategic relevance of HR information, it’s timely that companies are working on enhanced reporting. This is one of the reasons we’ve supported research on how human capital is being discussed in integrated reports.”

What will “enhanced reporting” actually entail? While the IIRC sticks to providing general principles, SASB is carefully providing specific standards. Harvard professor Robert Eccles sits on the board of SASB. In an interview he told us: “SASB has now issued standards for 45 industries in six sectors The specific issues we examine for human capital include labor relations; fair labor practices; employee health, safety and wellbeing; diversity and inclusion; compensation and benefits; and recruitment, development and retention. We have found human capital issues are likely to be material in every sector. Not surprisingly, the particular aspects of managing human capital that are most important vary by sector. For example, recruitment, development, and retention is particularly important in the knowledge intensive health care sector. Compensation and benefits is especially important in Financials, as is diversity and inclusion since financial institutions are under increasing pressure to align compensation with long-term value creation and penalize excessive risk-taking.” Your investor reporting systems may soon be required to answer a call to meet these reporting standards.

New reporting is interesting, but where’s the real payoff? The hope is that deeper reporting on human capital will motivate leaders to make more rigorous decisions about talent (including individual and organizational capability). For example, in the standalone human capital report from Deutsche Bank (2013), the bank showed trends in its investment in training — and in 2013 investment went down. That could be a bad thing, a step away from investing in talent. Deutsche Bank felt compelled to explain there was a good reason (in this case increased efficiency through e-learning). As talent decisions become more transparent and more quantified, the logic behind them will also become more apparent, and they are likely to be made with better rigor, as investors and others learn what decisions drive value.

For CEOs and leadership teams that spend substantial time and resources on talent, capability, leadership, and culture, the requirement that organizations share more information offers an opportunity to better tell their story to investors. Those with a sound and logical connection between their human capital decisions and their strategic mission will benefit as investors better understand the whole picture of value creation.

For CFOs, it is an invitation and a potential obligation to get a better handle on human capital measurement and collaborate with the CHRO and the human capital data and analytics team, to get more analytical and quantitative about human capital, beyond simply measuring its financial cost. For example, CFOs and CHROs should seek to move beyond the typically vague risk assessments of today, such as “inability to attract and retain talent may impact our performance” to offer specific data on the risks of losing talent in pivotal roles and the potential financial impact.

For CHROs, these requirements may provide a platform for HR analytics and measurement to gain more prominence at the Board and C-suite level, much as having a Compensation Committee on most Boards has elevated discussions about executive pay and total rewards. This is good news for HR’s influence and stature, but it also obligates HR leaders and the HR profession to have a rigorous and evidence-based framework that guides decisions about what measures matter and why.

For the average manager, it is a reminder of the argument we made in Beyond HR, that human capital deserves to be treated with the same rigor as financial capital and other tangible resources, and to bring that rigor by applying frameworks developed in more quantitative disciplines like finance, supply chain and marketing. Managers may soon be held much more accountable for demonstrating that they make rigorous decisions about human capital and organizational capability.

The writing is on the wall and it’s in the handwriting of heavyweights like Michael Bloomberg’s. Whether it’s called “integrated,” “enhanced,” or “holistic” reporting, there is a slow and steady movement toward giving investors more precise information about things that have traditionally been reported only vaguely or not at all. The prudent course may be to increase your organization’s rigor and analytics toward human capital first for the C-suite, then for the board, and one day, perhaps sooner than you think, for investors.

[image error]

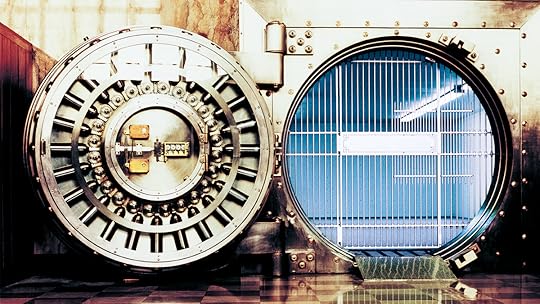

If Data Is Money, Why Don’t Businesses Keep It Secure?

Personal data is the new currency of the digital economy. Like money, it can flow easily across borders and it commands an intrinsic value — the insight generated from personal data helps deliver benefits to individuals, businesses, and governments alike. Yet, unlike money, the market for personal data is relatively embryonic. Important questions, such as who “owns” personal data and what responsibilities companies have as custodians of it, are hot topics of debate. If businesses are to continue using personal data to create value for themselves and for their customers, they will need to manage it as carefully as they would money, in four key ways.

1. Maintain trust to avoid data runs

People deposit money with the expectation that they will be able to safely and readily withdraw funds and earn some form of return. When there is no longer trust in the institution, capital flight can be rapid. Today, we are seeing similar responses to concerns over the secure and responsible use of personal data. A 2014 global survey by SafeNet found that nearly two-thirds of consumers said they would stop or avoid using a company that had experienced a data breach. Similarly, trust erosion triggered by Edward Snowden’s revelations of government surveillance in mid-2013 are estimated to have cost U.S. technology companies as much as $35 billion in potential business. At the same time, several technology platforms that do not collect or share personal data have emerged since mid-2013. DuckDuckGo — a search engine that allows users to access it anonymously — saw the number of daily queries double in the second half of 2013, and reach more than 7 million in early 2015.

To help retain trust, many businesses combine enhanced security measures with efforts to become more transparent about their data practices, giving customers greater levels of control. Telecommunications company Telefonica is currently developing a “Data Locker” scheme that allows users to see their own data, including the social networks of those they talk to and text with. This initiative would offer customers opt-in choices to share personal data in exchange for new services and give rewards to top data-sharers.

2. Understand how regulation alters the data cost-benefit analysis

In any investment decision, understanding the potential costs and likely returns requires an intimate understanding of many factors — not least the local regulatory environment. Today, new policy approaches to data privacy are requiring businesses to update their understanding of the costs and benefits associated with collecting and analyzing data across different economies.

For example, proposals in Brazil (since dropped) and, most recently, Russia would require companies to store data of domestic citizens physically within the country, a potentially significant cost for businesses collecting data about citizens in those countries. Large technology companies might have to pay as much as $200 million to build a data center in Russia, compared with $43 million in the United States.

However, many companies are recognizing that it is worth investing in a long-term reputation for security and privacy. This may involve taking extra steps to protect customer data that is not deemed “sensitive” in nature, such as viewing habits or style preferences; or extending the coverage of data protection to customers’ other activities online (e.g. for a bank to provide data security protections to its customers’ social media accounts). And in turn, many governments are realizing the extent to which a reputation for regulatory excellence in this area can attract business investment. Singapore passed its Personal Data Protection Act in 2014 as a strategic move “to strengthen Singapore’s position as a trusted global data hub” of the future.

3. Manage brand reputation by engaging with data rating agencies

Reporting standards, codes of conduct and rating agencies — such as Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s, and Fitch — all help to ensure the transparency of the financial system. By providing a range of independent views on the risk profile of different economies, investors can have greater confidence in the system as a whole.

However, in the personal data market, customers currently feel that they have little idea or control about how their data is being used or by whom. According to a survey by telecommunications company Orange, seven out of 10 consumers feel that there are few or no ways to find out how their personal data is being managed and protected online. And a higher share (82%) find it hard to control the use of personal data by organizations.

As a response, independent sources of oversight are springing up. For example, Fair Data, launched in 2013, is an accreditation system that recognizes companies who adhere to its ten Fair Data principles. In a similar vein, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a non-profit digital rights group based in the U.S., has recently started publishing scorecards on the major Internet companies, based on an assessment of their commitment to protect customer interests when third parties seek to access their user data. As programs like these gain wider recognition, businesses may consider engaging with “data rating agencies” to give credence to their assessment, and harness them as a more visible source of differentiation and brand enhancement.

4. Strengthen customer sovereignty by learning from data intermediaries

In financial markets, customers generally know how much money they have and can control how it is invested. However, in the personal data market, customer sovereignty is more limited. Individuals are largely in the dark about how much their personal data may be worth and who might be monetizing it. If the personal data market is to be sustainable, closing this gap and providing more incentives for individuals to share their data would appear to be prerequisites.

Startups in particular are emerging to tackle this problem. Datacoup, based in New York, offers people $8 a month in return for access to a combination of their social media accounts. Placed — a “location analytics” company — offers customers $5 or $10 gift cards in exchange for data collected from an app that tracks their location. And in the United Kingdom, Handshake is a personal data platform currently in development that will give users the opportunity to earn money in exchange for their data and time spent filling out pulse surveys. A tech-savvy British person who is willing to use the platform frequently can expect to earn £5,000 a year.

Taking their cue from startups, incumbent companies are also realizing the potential value of enhancing the rewards accruing to their customers. A number of American retailers such as Target, Macy’s, and JC Penney have partnered with Shopkick, a mobile app that monitors the location of participating shoppers and gives out monetary rewards and discounts. In 2013 alone, this app drove $500 million in revenue for its partners.

In any market — and particularly those in the early stages of development — uncertainty is commonplace. In the personal data market, many key questions remain to be answered. How will the attitudes of younger generations change market dynamics? Will global regulation harmonize or fragment the market? How will technology evolve to address customer concerns? To navigate these uncertain waters, businesses need to prepare for multiple potential futures and draw lessons from the development of other relevant markets. As with their money, the key with personal data is for businesses to manage it wisely.

[image error]

Smart Leaders Are OK with Seeming Uncertain

The expression of confidence is intimately tied up with leadership. Would-be leaders are careful to present a confident face because it helps gain them credibility and convince others that they know what they are doing.

When George W. Bush faced John Kerry in their first Presidential debate in 2004, Bush criticized Kerry for having vacillated on the war in Iraq. “I just know how this world works,” Bush declared. “And in the councils of government, there must be certainty from the U.S. President.” Even those who may have disagreed with Bush’s policies may nevertheless support this view. In his profile of President Barack Obama, Michael Lewis put it this way: “After you have made your decision, you need to feign total certainty about it. People being led do not want to think probabilistically.”

New York Mayor Bill de Blasio got in trouble two weeks ago for something similar when he predicted that a blizzard “could be the biggest snowstorm in the history of this city.” He was doing what leaders routinely do: acting as if they know what will happen when, in reality, there is substantial uncertainty. Different meteorological models offered different potential paths for the storm to take. Some of them did indeed predict 30 inches of snow, but others predicted something more like what actually happened. de Blasio could not have known which of these models would ultimately prove accurate, but he chose not to represent that uncertainty in his advice to city residents.

By choosing to focus on the worst possible outcome, New York’s leaders sought to encourage people to take precautions. In this, they succeeded. But they also undermined the credibility of warnings of future disasters. When another storm comes, New Yorkers are likely to be more skeptical of the Mayor’s warnings. The leader’s dilemma in this situation: Is it better to err on the side of caution or action? False negatives fail to warn of impending storms, attacks, or disasters. False positives cry “wolf” by exaggerating future risks.

Fortunately, there is a path between these twin risks. That middle way empowers leaders to express well-calibrated uncertainty when they devise policy or recommend actions to the public or shareholders. In other words, leaders shouldn’t just focus on the best, worst, or even the most likely possibility; instead they should provide a range of possible outcomes. Companies are already used to doing this in one setting: corporate earnings. When public companies issue earnings guidance, they provide a range within which profits are likely to fall. Leaders should use this technique more often and in more areas to avoid the trap of false certainty.

The problem is that leaders may be especially resistant to communicating uncertainty. In my research with colleagues at Carnegie Mellon and UC Berkeley, we found that those who express confidence gain credibility that helps them attain positions of status and influence in the groups of which they are a part. By the time leaders reach the top job, they’ve often learned to err on the side of certainty in order to instill confidence and gain status in their organization. Furthermore, leaders are disproportionately likely to be surrounded by people who praise their wisdom rather than question it.

Though it may be particularly hard for leaders to embrace uncertainty after years of being taught to display confidence, there is a clear business benefit in doing so. Research has shown that over-confident CEOs make overly risky decisions, often at the expense of their shareholders. Leaders who are able to come to terms with uncertainty and communicate it to employees may avoid such bad decisions.

In the long term, honesty is the only sustainable strategy. Rather than fooling themselves, or us, we should want our leaders to represent the truth, even when it makes their jobs harder. That is, after all, one of the great missions to which we entrust them: to take the complex information and broad vantage point to which they have access and convey it to the rest of us in a useful way. Doing so represents authentic and courageous leadership, even if it means being less certain.

[image error]

How America’s Wealthiest Black Families Invest Money

The gaps in wealth and income between white and black Americans are stark – and haven’t narrowed significantly in 50 years. There are even big gaps among black and white business owners.

According to data from the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), white Americans’ median incomes were 70% higher than black Americans’ in 2010. Overall net worth was 7.9 times larger for white Americans.

Credit Suisse and Brandeis University’s Institute on Assets and Social Policy took a closer look at that dataset to figure out whether there were similar disparities be found among the wealthiest households. The short answer is yes.

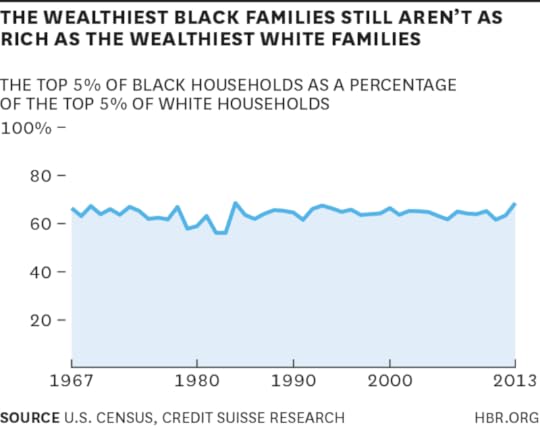

Among the richest 5% – according to Census data – black Americans have earned roughly 60% what white Americans earned over the last thirty years:

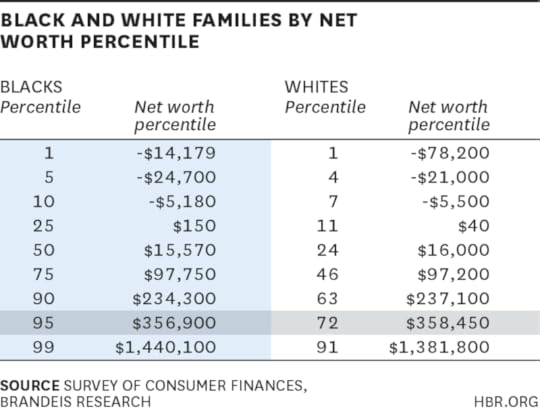

Here’s another way of looking at it. If you’re white and have a net worth of about $356,000, that’s good enough to put you in the 72nd percentile of white families. If you’re black, it’s good enough to catapult you into the 95th percentile.

(The researchers decided to focus on the 95th percentile, rather than the 99th, because the 99th percentile in the SCF data was only 12 black families – not a large enough sample size to support significant conclusions.)

The researchers then took a closer look at how the top 5% of black households allocate their wealth, and compared it with the wealth strategies of comparatively wealthy white households. (So, not the top 5% of whites – but the whites with about the same amount of money as the top 5% of blacks – in other words, about $356k.)

Before diving into those differences, it’s worth pointing out that there are a lot of similarities between these two groups – relative to the general black and white populations, both are more likely to be older, college educated, married, and either retired or running their own business. The biggest single category of wealth for both groups is their retirement accounts. And among the top 5% of black households and comparatively wealthy white households, both groups have a median income of about $100,000 per year.

But there are some notable differences in how each group approaches their money. Here are a few:

The wealthiest 5% of black Americans are slightly less likely to hold financial assets (stocks, bonds, and so on) in their asset mix. Of the financial assets they do invest in, wealthy blacks are more likely than wealthy whites to invest in safer assets, preferring CDs, savings bonds, and life insurance to higher risk (and higher reward) assets.

Wealthy black Americans have more money in real estate holdings than equally wealthy white Americans. The former hold 41% of their non-financial assets in (non-primary residence) real estate, while the figure for the latter is just about 22%. Adding in primary residences brings those numbers to 57% and 34%, respectively. Even after the housing bust, real estate is considered a lower-risk investment.

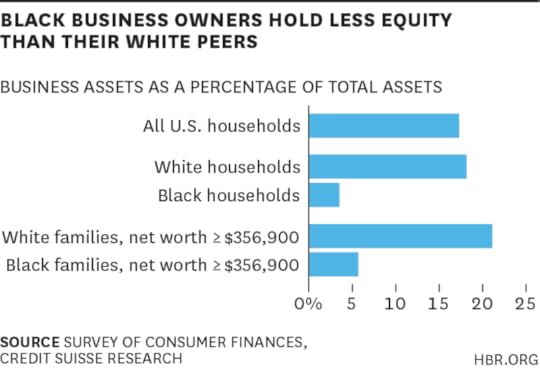

Wealthy black Americans are less likely to hold equity in business assets. Looking at this group’s non-financial assets, 9% are equity in business assets. That figure is 37% for comparably wealthy whites. The numbers are similarly stark if you look at this as a percentage of total assets: 21% of the wealthy whites’ total assets are invested in their own businesses, versus just 6% for wealthy blacks. Because both groups are equally likely to run their own companies – 23% in both cases – the researchers calculate that this means white business owners are investing in their businesses at a rate 7 times higher than black business owners. In raw dollar terms, it means that black business owners have about $68k in their businesses, while white business owners have roughly $468k.

This all adds up to a more conservative investment strategy for wealthy black Americans. But as the study points out, that actually makes a lot of sense – given that even at the top of the economic ladder, black Americans still find themselves in a precarious position.

Consider some other findings from Brandeis University’s Institute on Assets and Social Policy. In 2009, 57% of the top-third of black Americans had been in that economic bracket since 1984. But 8% had fallen into the bottom third. Those numbers for the richest white families? 73% and 1%, respectively.

A 2003 study out of NYU, by Dalton Conley and Rebecca Glauber, showed similar findings: that 60% of white families who were in the top quartile of wealth in 1984 were still there in 2003 – but that figure for black families was only 24%.

Another possible explanation for black families taking fewer financial risks: they have less financial support from the previous generation to rely on. Only 7% benefit from an inheritance; but 36% of white families do, according to the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. And white families’ inheritances are about 10 times as big. For these reasons and more, it makes sense for a wealthy black person to be conservative with his or her investments.

What is less easily explained away is the much lower rates of business equity among black business owners. Since both the wealthiest black people and similarly wealthy white people are equally likely to be running their own business, why does the white group have so much more equity?

One possible explanation floated by the Credit Suisse/Brandeis researchers is that whites have more access to start-up capital when they found their businesses, which translates into greater business success down the line. (This hypothesis is based on findings by economists Robert W. Fairlie and Alicia M. Robb.)

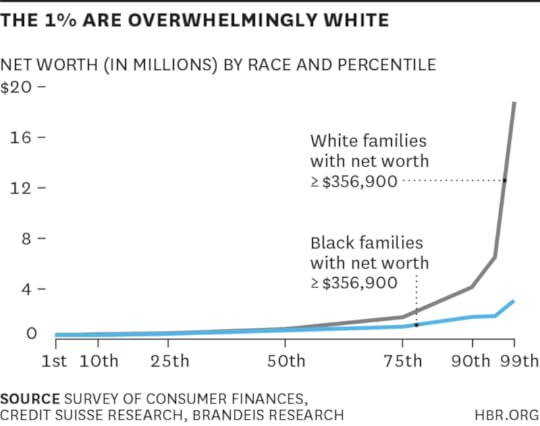

The upshot is that black and white families’ wealth tracks about the same to the 50th percentile, and then whites’ wealth takes off exponentially. In America, in other words, the super-rich are also super-white.

[image error]

February 9, 2015

Most HR Data Is Bad Data

How good a rater do you think you are? If you were my manager and you watched my performance for an entire year, how accurate do you think your ratings of me would be on attributes such as my “promotability” or “potential?”

How about more specific attributes such as my customer focus or my learning agility? Do you think that you’re one of those people who, with enough time spent observing me, could reliably rate these aspects of my performance on a 1-to-5 scale? And how about the people around you – your peers, direct reports, or your boss? Do you think that with enough training they could become reliable raters of you?

These are critically important questions, because in the grand majority of organizations we operate as though the answer to all of them is yes, with enough training and time, people can become reliable raters of other people. And on this answer we have constructed our entire edifice of HR systems and processes. When we ask your boss to rate you on “potential” and to put this rating into a nine-box performance-potential grid, we do it because we assume that your boss’s rating is a valid measure of your “potential”— something we can then compare to his (and other managers’) ratings of your peers’ “potential” and decide which of you should be promoted.

Likewise, when, as part of your performance appraisal, we ask your boss to rate you on the organization’s required competencies, we do it because of our belief that these ratings reliably reveal how well you are actually doing on these competencies. The competency gaps your boss identifies then become the basis for your Individual Development Plan for next year. The same applies to the widespread use of 360 degree surveys. We use these surveys because we believe that other people’s ratings of you will reveal something real about you, something that can be reliably identified, and then improved.

Unfortunately, we are mistaken. The research record reveals that neither you nor any of your peers are reliable raters of anyone. And as a result, virtually all of our people data is fatally flawed.

Over the last fifteen years a significant body of research has demonstrated that each of us is a disturbingly unreliable rater of other people’s performance. The effect that ruins our ability to rate others has a name: the Idiosyncratic Rater Effect, which tells us that my rating of you on a quality such as “potential” is driven not by who you are, but instead by my own idiosyncrasies—how I define “potential,” how much of it I think I have, how tough a rater I usually am. This effect is resilient — no amount of training seems able to lessen it. And it is large — on average, 61% of my rating of you is a reflection of me.

In other words, when I rate you, on anything, my rating reveals to the world far more about me than it does about you. In the world of psychometrics this effect has been well documented. The first large study was published in 1998 in Personnel Psychology; there was a second study published in the Journal of Applied Psychology in 2000; and a third confirmatory analysis appeared in 2010, again in Personnel Psychology. In each of the separate studies, the approach was the same: first ask peers, direct reports, and bosses to rate managers on a number of different performance competencies; and then examine the ratings (more than half a million of them across the three studies) to see what explained why the managers received the ratings they did. They found that more than half of the variation in a manager’s ratings could be explained by the unique rating patterns of the individual doing the rating— in the first study it was 71%, the second 58%, the third 55%.

No other factor in these studies — not the manager’s overall performance, not the source of the rating — explained more than 20% of the variance. Bottom line: when we look at a rating we think it reveals something about the ratee, but it doesn’t, not really. Instead it reveals a lot about the rater.

Despite the repeated documentation of the Idiosyncratic Rater Effect in academic journals, in the world of business we appear unaware of it. Certainly we have yet to grapple with what this effect does to our people practices. Look closely and you realize that it will cause us to dismantle and rebuild virtually all of them.

Fueled by our belief in people as reliable raters, we take their ratings — of performance, of potential, of competencies — and we use them to decide who gets trained on which skill, who gets promoted to which role, who gets paid which level of bonus, and even how our people strategy aligns to our business strategy. All of these decisions are based on the belief these ratings actually reflect the people being rated. After all, if we didn’t believe that, if we thought for one minute that these ratings might be invalid, then we would have to question everything we do to and for our people. How we train, deploy, promote, pay, and reward our people, all of it would be suspect.

And yet, is this really a surprise? You’re sitting in a year‐end meeting discussing a person and you look at their overall performance rating, and their ratings on various competencies, and you think to yourself “Really? Is this person really a ‘5’ on strategic thinking? Says who – and what did they mean by ‘strategic thinking’ anyway?” You look at the behavioral definitions of strategic thinking and you see that a “5” means that the person displayed strategic thinking “constantly” whereas a “4” is only “frequently” but still, you ask yourself, “How much weight should I really put on one manager’s ability to parse the difference between ‘constantly’ and ‘frequently’? Maybe this ‘5’ isn’t really a ‘5’. Maybe this rating isn’t real.”

And so perhaps you begin to suspect that your people data can’t be trusted. If so, these last fifteen years have proven you right. Your suspicions are well founded. And this finding must give us all pause. It means that all of the data we use to decide who should get promoted is bad data; that all of the performance appraisal data we use to determine people’s bonus pay is imprecise; and that the links we try to show between our people strategy and our business strategy — expressed in various competency models — are spurious. It means that, when it comes to our people within our organizations, we are all functionally blind. And it’s the most dangerous sort of blindness, because we are unaware of it. We think we can see.

There are solutions, I’m sure. But I think, before we can even consider those, we must first stop, take stock, and admit to ourselves that the systems we currently use to reveal our people only obscure them. This admission will challenge us. We will have to redesign almost our entire suite of talent management practices. Many of our comfortable rituals — the year-end performance review, the nine-box grid, the consensus meeting, our use of 360’s — will be forever changed. For those of us who want HR to be known as a purveyor of good data — data on which you can actually run a business — these changes cannot come soon enough.

[image error]

Strategic Humor: Cartoons from the March 2015 Issue

Enjoy these cartoons from the March issue of HBR, and test your management wit in the HBR Caption Contest. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

“These aren’t our real numbers, but darn it, they’re the numbers we deserve.”

Paula Pratt

“Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day. Give him a Kickstarter campaign,

and he can write a bad fishing memoir.”

John Klossner

Scott Arthur Masear

And congratulations to our March caption contest winner, Eric Woodman of Roslindale, Massachusetts. Here’s the winning caption:

“It’s a new transportation start-up called UBear.”

Cartoonist: Crowden Satz

NEW CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your caption for this cartoon in the comments below—you could be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free book. To be considered for this month’s contest, please submit your caption by March 3.

Cartoonist: Crowden Satz

[image error]

Your Board Should Be Full of Activists

With more than two centuries of making everything from gunpowder to nylon and Tyvek, Dupont Co. has renewed its product lines many times. Now it is being pressed to renew its governing board as well. Its directors have turned over many times, of course, but Trian Fund Management, led by activist Nelson Peltz, is pressing for far more than a routine remake, demanding four seats of its own choosing at the table. This despite Dupont’s strong results over the past two years, its stock outperforming the S&P 500 index by 47 percent. Dupont did not give in to Nelson Pelz’s demands, but .

Activist investors waged a record number of campaigns against U.S. companies in 2014 and show no signs of letting up in 2015. Among their trophies in 2014 was a complete housecleaning at Darden Restaurants, the largest operator of full-service restaurants in the U.S. When Darden directors backed a spin-off that many owners opposed, Starboard Capital—with the support of many institutional investors—led the ouster of the entire board. Much the same occurred at Canadian Pacific Railway in 2012, when Pershing Square Capital Management acquired control of its board.

This is a good time to renew your board before an outside activist tries to change it. Here’s why. The backing of the traditionalists like Vanguard Group is often giving activists like Trian — the latter with just 2.7% of DuPont’s shares — the extra clout they need. Vanguard holds more than $3 trillion in assets, making it the equivalent of the world’s fifth largest country in GDP, ahead of France. Along with its heavyweight brethren like Fidelity and Blackrock, it packs enormous punch. Vanguard owns some 5% of most publicly-traded companies in the U.S., and with half of its fund assets indexed, it is not going anywhere if it does not like its portfolios’ strategies or results. But that does mean indexed investors will remain passive if a company’s strategy could be strengthened or its results could be better.

To the contrary, said Vanguard CEO William McNabb, this is “precisely why we care so much about good governance.” Good means directors who exercise independent oversight and who are deeply engaged in the company’s long-term strategy. Consider what the board of General Electric has declared as its criteria for new directors. In its 2013 proxy statement, GE announced that it is searching for director candidates who will bring technology, marketing, finance — and “leadership” experience to the boardroom. “We believe,” explained the GE board, that “directors who have held significant leadership positions, especially CEO positions, over an extended period, provide the company with unique insights.”

We are reminded yet again that the chief executive is no longer the sole leader of the enterprise. In recent years, the competitive fires of capitalism have been pushing directors to the fore as well. If individual directors are not adding real value to the firm’s leadership, especially in the eyes of institutional investors, this is an opportune moment time to recruit directors who will.

To that end, dialogue between directors and investors should be part of the equation too, including activists. We are personally familiar with several companies whose boards now routinely vet director candidates with their major shareholders before their names are placed on the proxy. But directors will certainly want to retain final authority, seeking guidance but surrendering nothing.

Vanguard CEO McNabb even advocates forming a “Shareholder-Director Exchange” and for boards to create a “Shareholder Relations Committee” to facilitate such dialogues. “You, as directors, have a great opportunity to tell us how you bring value to investors,” he said, and since “we are your permanent investors,” we “want to listen.”

We would take that further. Instead of waiting for an activist to force their agents into a boardroom with the avowed purpose of redirecting strategy — as happened at Darden Restaurants — why not have the board leader, whether chair or lead director, preemptively strike? Spearheading a board’s own renewal calls for more carefully considering who comes on to the board, who remains on the board, and above all how the board is organized and led as an active strategic partner of management.

Glenn Tilton, former CEO of Texaco and United Airlines and director of Abbott Laboratories, AbbVie, and Phillips 66, well captured the point. From his own experience, he told us, board leaders and chief executives could make far better use of their board. They should insist that every director is deeply informed and keenly contributing to the company’s strategy and risk management. When he was running United Airlines, for instance, he asked directors to accompany him on calls to customer CEOs to demonstrate the directors’ personal commitment to the company’s turnaround.

We should thus think of activism, Tilton concluded, in a very different way. Simply put, he said to us, the “board leader should instead be the activist.” And everybody on the team should be savvy on strategy. “Does the talent around the board table,” he would ask as board leader, “reflect all the success determinants for the company, and the risks that can derail it?” Former CEOs bring a lot, he has found, as do experts on risk management. “I want to look down the board table and see a set of directors every bit as good,” he said, “as top management.” And to bring that out, he would go around the table and ask each director for informed direction at pivot points, allowing no place for the uninformed to hide.

Raj Gupta, former CEO of Rohm and Haas who has served on the boards of Delphi Automotive, Hewlett-Packard, Tyco, and Vanguard, urged that directors look at their firm from the “outside in” rather than “inside out,” posing the same questions that an activist investor would ask. Is the company’s portfolio too complex? Is management top-notch? Is the cost structure too high? Has the firm missed an inflection point?

The board, in short, Gupta told us, “should think like an activist.” So should top management, but Gupta also cautioned that this requires more from both. Unlike activists, directors and executives cannot forego long-term thinking. “Boards need to step up their game by asking the right questions,” he said, and for that they need directors on the board who can answer those questions and a culture in the board that focuses on them now — and also ten years out.

Whatever the particulars, with the proxy season approaching, this is an opportune moment for the board leader to bring activism home by becoming the board’s own Activist in Chief and for directors to ask the outside-in questions of themselves.

[image error]

How Power Affects Your Productivity

Think about the last time you came home from work completely and totally drained. I don’t mean the good kind of tired, when you’ve worked hard and gotten something done. I’m talking about exhaustion, colored by frustration and tinged with anger. Maybe you even felt hopeless. You were fed up, trying to be nice but snapping at family, wanting nothing more than to crawl into bed (or dive into a bottle of wine). If you’re like me, feeling pissed off and hopeless isn’t your natural state. And for those of us who love our work, feeling negative is doubly painful because it just shouldn’t be this way.

Sadly, though, we spend far too much time and energy dealing with destructive emotions at work — which is no doubt part of the reason so many people are disengaged. It’s also the reason why we often don’t live up to our full potential. When we’re stuck in a dissonant state, we lose our capacity for mindful learning. We don’t process data as quickly or well, and we make bad decisions. We aren’t very creative and we don’t adapt as the world around us changes. We don’t focus, so we don’t get as much done. In short, negative emotions make us less productive.

You and Your Team

Getting More Work Done

How to be more productive at work.

Then there is the stress. Toxic emotions affect our capacity to manage ourselves. There’s also increasing evidence that in mice — and people too — stress decreases our capacity for empathy. All in all, pervasive negative emotions impact how smart we are, not to mention our emotional intelligence.

What can we do? First, let’s face it: we’ve got to do something. Dissonance is an epidemic in our organizations. Why? Pressure, change, too much work, too few resources — sure, these all affect us, but let’s look at what we can control, starting with how we manage power.

Power, not money, is the real currency in organizations. It gets us what we need to stay “alive”. The strongest people make the calls, show us the way to go. And whether we admit it or not, most people want to be seen as powerful. There are lots of ways to at work, some that generate positive emotions, and some that aren’t so good. Healthy ways include striving to be the best at building a great team, and being at the center of information flows. When we wield these kinds of power, we feel pretty good about ourselves, and people trust and want to follow us.

Unfortunately, lots of people either don’t know how to get and keep power in positive ways, or they deliberately engage in destructive, even Machiavellian behaviors. They end up withholding information others need, stirring up trouble, and generally wreaking havoc.

Faced with people who are bad at handling power, we feel our jobs – and therefore our lives — are threatened, and we go into survival mode. We shut out everything in the environment except what we think we need to stay safe. Adaptability? Gone. Creativity? Snuffed out. Ability to take in information and make sense of chaos? Nope.

It isn’t easy learning how to deal with your own and other people’s power while maintaining positive relationships and a sense of personal safety and integrity. But it can be done. First, you need to do a gut check. How do you feel about power? Do you shy away from commanding people? Fight authority? Or conversely, are you constantly seeking the safety of someone else’s shadow? Clearly none of these is a healthy or effective approach. But in truth, many people are either caught in dysfunctional dependency upon people with power, or they are counter-dependent — fighting against them — just to prove they can win. These reactions stem from childhood and all of those old messages about how we should deal with authority. It’s a really good idea to do a bit of thinking about those old assumptions — do they still serve you? If not, it may be time to change. Awareness isn’t everything, of course. But honestly assessing your deep feelings and reactions is a good first step on the path to dealing with negative emotions at work.

For leaders, deepening your self-awareness will help you acknowledge that people see you as powerful (and maybe even a bit scary). Never forget for a moment that your whisper is a shout. As far as your employees are concerned, you hold their fate in your hands, and your emotions spread easily to them. In the end, knowing how to use your power will enable you to consciously choose to create a climate in which everyone can be and do their best.

Let’s not give in to the dissonance that has become the default in so many companies. Let’s take charge — of ourselves, first.

[image error]

Larry Summers on What Business Can Do to Save the Middle Class

There’s growing recognition that CEOs are paid too much, that shareholders are pocketing too large a share of corporate profits, and that high levels of inequality are bad for economic growth. The case for paying workers more keeps getting made — again, and again, and again — and yet the gap between the rich and the rest continues to grow, within countries and companies alike.

Rising income inequality is a feature of most advanced economies, and yet we seem hard-pressed to do anything about it.

Enter a new report from the Center for American Progress, co-led by Larry Summers, the Harvard economist, and Ed Balls, a Member of the British Parliament. Their answer to inequality and stagnant living standards is “inclusive prosperity,” an economic agenda centered around middle-class growth.

I asked Summers about his proposals, and business’s role in implementing them. A condensed and edited version of our conversation follows.

What is inclusive prosperity and why should executives and business owners care about it?

Inclusive prosperity refers to the idea that growth — growth that is inclusive, that benefits the middle class — is essential if nations are going to flourish.

Without middle class growth, institutions lose legitimacy. The American example is degraded. The ground is fertile for populist revolt. The debt becomes much more difficult to manage and cynicism corrodes the functioning of the society.

I think it is a lesson of history that businesses succeed or fail with nations. It is very difficult for any company to be highly successful based in a country whose national economy is stagnating. And it is much easier for businesses to succeed when a society is functioning well.

Can the private sector create a more inclusive economy or is it up to policymakers to solve the problem?

The right public frameworks are in the interest of the majority of businesses that very much want to do the right thing. That means cracking down on tax shelters that give some businesses a competitive advantage. That means strengthening regulation where some businesses are putting competitive pressure on others by skimping on safety, by denying workers basic benefits, or by operating with dangerous degrees of leverage. Support for making certain benefits like family leave universal serves the interests of good employers against ruthless employers who may seek to gain advantage by skimping on basic benefits.

What would change about the relationship between firms and workers in a more inclusive economy?

I think we need to encourage employers to make decisions based on something other than the ruthless reduction of costs. During the time I was president of Harvard, we instituted a policy that if the university outsourced a function like, for example, janitorial services or cafeteria services, those to whom it outsourced had to pay the same wages that the university paid. That did not mean we were biased against outsourcing if it was more efficient, but it did mean that we were leveling the playing field and did not permit outsourcing to gain advantage simply by holding down wages.

I would hope that businesses would increasingly see the need to invest first in their own interest in their workforces. Study after study suggests that programs of family leave reduce workers’ stress and permit workers to continue working in ways that benefit not just the worker but also their employer.

I also think that businesses need to contemplate their relationship with their workforces in other ways. Experience suggests that where workers are empowered, given more voice to shape the terms of their employment and the way in which they work, productivity very often increases.

There’s an increasing body of evidence suggesting the desirability of profit-sharing as a way of enfranchising and motivating workers. And there is even some increasing suggestion in the data that corporate leaders who maintain a philosophy of teamwork where, for example, pay differences within a firm are limited and where everyone shares in success and failure, get better results.

What about the role of more traditional unionization and collective bargaining?

I think that one has to maintain a sense of balance. Unions are right in some employment contexts. Unions do not add value in other employment contexts.

What I think is important is the principle enshrined in U.S. law that workers should have the right to collectively bargain if that is what they desire. I am concerned that in recent times that right has eroded because employers have been permitted to retaliate against those who seek to organize workers with impunity.

At the same time, I would be the first to recognize that in a world where American businesses are competing very vigorously with foreign competitors, in a world where domestic competition has increased substantially, prudent union leaders will need to recognize that they need to cooperate with management to craft employment arrangements that better serve workers, but also serve the objectives of competitiveness and economic efficiency.

I think there’s substantial scope for thinking about new compacts between firms and workers in the mutual interest of both.

What about freelancing and the sharing economy and the idea that the contract between companies and workers is changing?

I’m a believer in the sharing economy. I feel proud to serve on the board of Lending Club. I certainly see enormous efficiencies coming and improvements in economic performance coming from efforts to deploy the economies of housing resources more efficiently through firms like Airbnb or transportation resources more efficiently through firms like Uber and Lift.

I believe that much of the way capitalism moves forward is through organizational innovation as well as through technological innovation and the so-called sharing economy represents an important example of that.

At the same time, in crafting our social institutions we need to recognize that if workers are going to have more flexible terms of employment, are going to work in many cases more irregularly and for different employers, that the provision of a basic social safety net is something that’s going to be done less by employers and that there will be a role for government in picking up the slack. I think that recognition has to inform the approaches that we take.

How does corporate governance need to change in your view?

I was struck that in a panel discussion at Davos the FT journalist Martin Wolf asked those present what fraction of them felt that share value maximization was in the interests of the broader economy.

At Davos, hardly a Marxist redoubt, 70% of those who answered the question initially said they felt that it was not, as currently practiced, in the long run interests of economies.

I believe in general that property rights are immensely important and I support the idea that businesses should be run for the benefit their owners. And I think that efforts to align those who are managing business with the interests of shareholder owners are for the most part a positive thing.

But I have the concern that as currently practiced, our institutions provide overly high-powered incentives for taking steps that will benefit share prices in the very short run and insufficient incentives for taking steps that will benefit the company and both shareholders and stakeholders over the long run. I think this tendency has been exacerbated by some of the extremes of activism that we have witnessed in recent years where activists have sought to disrupt or restructure companies for the sake of an immediate payout even at some sacrifice of long-run interests.

I am sympathetic to proposals for staggered boards of directors to make activists’ attacks more difficult. I am sympathetic to proposals to provide particular protections for long-term holders of companies who can serve as validators that management’s long-term investment plans are in fact in the interests of corporate shareholders.

The ruthless short-run Darwinianism of the activists is not the way forward. Neither, though, is the belief that management should be entirely trusted independent of the results they have generated. What we need is to find a way of empowering active, critical, but patient board members for our leading corporations.

Anything else you’d like to add?

Just one thing. John Kennedy in his inaugural address famously said, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

That was a reasonable thing to say that called forth a great response at a time when American middle-class standards of living had grown rapidly. When millions of families were enjoying the benefits of the interstate highway system. When a generation had been educated by the GI Bill. When millions of families were fulfilling their version of the American Dream by living in their home in the suburbs thanks to the FHA and a range of successful public investments.

If it’s much more difficult to call on Americans today, that is importantly a reflection of the failure of the national economy to deliver rising standards of living in the way that it once did for the middle class.

[image error]

Uber Needs Our Permission to Grow

Last week, I fielded an inquiry from a New York Times reporter asking if I would like to comment on the apparent change of heart (and strategy) underway at Uber. You know, the new “kinder, gentler” Uber — the Uber that is eager to collaborate with local governments, and to calculate its contribution to sustainability and to getting cars off the road, the one that is serious about beefing up its safeguards on access to rider data. At first blush, this was a highly unlikely subject for me to weigh in on: I am just about the only person I know who is not gaga over the Uber experience. Nor am I a fan of its pugnacious approach even to regulations as outdated as those governing the taxi industry — what CEO Travis Kalanick has called Uber’s stance of “principled confrontation.”

While I was an unlikely commentator from one perspective, I was well-suited from another. I am a firm believer that companies need society’s permission to grow, and it would appear that Mr. Kalanick and the management team at Uber are coming to this realization as well. This notion of “permission to grow” did not originate with me. I first picked it up in correspondence I was fortunate enough to have carried on with Alfred Chandler (yes, that Alfred Chandler) almost 20 years ago, in the course of writing a book. This was a good old-fashioned exchange of typewritten, snail-mailed letters — Dr. Chandler’s preferred medium. He and I were discussing Wal-Mart’s prospects, as I recall, and whether the company could succeed in resetting our collective understanding of the size that a retailer could attain. So what were the limits to its growth: Adequate labor pool? Attractive retail locations? Sizable acquisition targets? Proximity of adjacent planets? He wrote in one of those letters (How I wish I’d kept it!), “Companies need society’s permission to grow.” Mind you, this was well before Wal-Mart management rolled out its kinder, gentler vision (“Save money. Live better.”).

Companies need society’s permission to grow. We see this demonstrated both in the antitrust courts and in the courts of public opinion. The most extreme proof of this axiom is, of course, our reaction to “unreasonable” monopoly, as expressed in the breakup of the Standard Oil group in the first decades of the last century. There are abundant examples across the intervening years: following World War II, Dow was forced to share its proprietary processes for manufacture of magnesium and synthetic rubber, setting the company back a decade in the view of company officials. DuPont was forced to dissolve its patent-pooling arrangements with foreign chemical firms and disgorge its cross-holdings in GM stock, devastating both its top and bottom lines. And in more recent experience, of course, we have witnessed the seemingly never-ending antitrust battles of Microsoft and the constant, uneasy attentiveness of Facebook management to the data privacy concerns of its users. The management teams of all of these companies became aware—sooner or later—of a simple, compelling truth: When society withdraws its permission for a company to grow, that growth can stop dead in its tracks.

Today we call the withdrawal of this permission “reputation risk” — how favorably a company’s motives, impact, and agency are regarded by important external constituencies. A good reputation can lead to a whole host of benefits; a bad reputation, on the other hand, can lead to a loss of customers, disengaged and unmotivated employees, and shareholder dissatisfaction. Whatever form Uber’s risk management dashboard takes, it is clear that the reputation risk hazard lights have been flashing red for some time now. Conflicts with government, here and abroad; legitimate, frightening concerns over rider safety; data privacy violations — these are the kinds of risks that Dr. Chandler was warning us about, risks that by their nature flare up suddenly, unexpectedly and painfully. At the very least, they pose a huge distraction to management.

And on this issue of management distraction, and organizational maturity, it is instructive to remember that Uber is impossibly young for all it has achieved. The company is only five years old (only five years old!), with thousands of employees, tens of thousands of drivers, a $40 billion valuation and global growth ambitions. The company is like an adult in an adolescent’s body, and so it is unsurprising that they should be suffering these growing pains. They have a lot of growing up to do — and in a hurry.

It seems fairly clear from the recent shift in strategy that this young management team has concluded that the last thing it needs is rearguard battles with regulators and customers when the road ahead presents such enormous challenges. And make no mistake, the immediate future for Uber promises to be much, much harder than the recent past. Their business model is in full view, ready to be copied; they have spawned a whole host of aspiring disruptors coming up underneath and seeking to topple them; and the investors who have bestowed such a rich valuation on the company will be incredibly sensitive to any bumps in its growth performance. Oh, and their employees — particularly their most valued employees — have ample alternative employment options. Given the choice, would you work for a pariah?

If Uber were a case study, it would fit perfectly in the course we teach at HBS, called “Building and Sustaining a Successful Enterprise,” because we are watching in real time as the management team digests a lesson that has been learned time and again by successful enterprises before them. If you had to distill our teaching down to a couple of sentences, they would read as follows: In order to build a successful enterprise, you need to have a remarkably well-integrated business model and capability set, focused on an important job that your customers are trying to get done. In order to sustain that success, however, you need the wisdom and humility to adapt when the capabilities and behaviors that earned you your initial success will no longer take you where you need to go. Calling that turn is the lonely, necessary lot of the leader.

So has Uber management spotted the inflection point early enough? My guess is that they have, and here’s my reasoning: We’d know it was too late if the question weren’t so engaging—if we’d all moved on to Lyft or Sidecar or any one of the dozens of similar upstarts. The fact that we’re all somewhat surprised by this new conciliatory stance of theirs—even wondering if it was really necessary—suggests that they’ve likely gotten the timing about right. If the Uber management team truly understands that they’ve outgrown the behaviors that served them well as an upstart, and they’re able to develop a new set of skills and behaviors more suited to the requirements of their current scale and future ambitions, then they might still have the ability to surprise us with how fully they have earned the permission that we have granted them, and with the impact that they can have on the world.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers