Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1317

February 20, 2015

How Leaders Should React When Someone Disappoints

“Why?” the CEO of the hedge fund yelled at one of his portfolio managers. “Why would you increase that investment? What were you thinking?”

The portfolio manager muttered a weak defense which the CEO promptly and easily tore to shreds.

When the manager left his office, the CEO turned to me, exasperated. “How do you reverse a losing streak?” he asked.

“Not like that,” I said.

High performing leaders expect a lot of themselves and the people around them, as they should.

But when people fall short of those expectations, the way leaders handle their disappointment can mean the difference between a return to high performance and a downward spiral of failure.

This is a serious deficit I have seen in many otherwise strong leaders. They’re inspiring when things are going well, but when the numbers slip, they can’t help losing their temper, or withdrawing.

“I need to hold people accountable,” I often hear from leaders who lean hard on people when they show disappointing results. “Maybe I yell a little, but they’re senior enough to take it.”

Sure, maybe. But what’s more important — holding people accountable or improving their performance? There’s a massive difference.

Yes, it’s important that people are accountable for their results, and if they don’t meet expectations, they need to know that. But in reality, if they’re generally high performers, they already know that they’re falling short. And, almost always, they take it seriously.

In other words, awareness and accountability aren’t their problems. What is? Regaining enough confidence to take necessary risks to succeed after a failure.

If you’re a high-performing, impatient leader, supporting others during tough times can be particularly hard for you to do.

It’s hard because your natural, knee-jerk response to underperformance is anger, directed at yourself and others. But our natural, knee-jerk responses are often counterproductive. (This is something I talk about a lot in my new book, Four Seconds.) Anger often feels right at the time, but it almost always makes things worse.

So, how should you respond?

Take a breath (that’s the four seconds part). Slow yourself down for the briefest of pauses — just enough time to subvert your default reaction. In that moment, notice your gut reaction. How do you tend to handle poor performance? Do you get angry? Stressed? Needy? Distant? Your role is to give people what they need to perform, not what you need to release.

Decide on the outcome you want. In this case it’s fairly straightforward: improved performance. Still, be specific. What does this particular person need in order to turn around this particular poor performance or failure? Maybe it’s help defining a stronger strategy, or brainstorming different tactics, or identifying what went right. Maybe they need to know you trust them and you’re on their side.

But here’s what people almost never need: to feel scared or punished. And more often than not, that’s how we make them feel when we “hold them accountable” in anger.

Choose a response that will achieve the outcome you want, rather than simply making your already obvious displeasure more obvious.

In hard times, people want to feel more connected to their leaders. They need to have reasons to trust you. They need to feel trusted by you.

But our instinctive response is to be less visible and to communicate less positively. We have to counteract that instinct and connect more. That means more offsites, and more conversations among senior executives, as well as between senior executives and the rest of the organization.

One CEO I know resisted his urge to come down hard on people after a difficult year when the company didn’t achieve its goals. He had done that in the past with poor results. We talked about how the employees were already feeling down, compounded by the fact that none of them made the bonus threshold. He wanted to reinvigorate them so he did a counterintuitive thing: he rewarded them.

He told them that, while they didn’t earn their bonuses because of the results, he and the other senior executives knew how hard everyone worked. Then he announced that the senior executive team was going to give a share of their compensation to the rest of the company. The new energy and loyalty this created drove the company’s turn-around.

Another CEO I know had a meeting scheduled with a project team responsible for a high-profile pilot project that held the possibility of a large piece of client work. But the team was struggling and the pilot faced many challenges, some of them the fault of the team. He had prepared a short speech to tell them how critical this project was, how the company was riding on it, and how they had better fix the problems and make it work.

But when he stepped into the meeting and looked at the faces of the engineers, many of whom didn’t even meet his glance, he took a breath and changed his tactic on the spot. He knew he needed their positive energy now more than ever. And he did trust them. He started the way he had intended: “This project is critically important to our success,” and then he shifted his approach, “I know you’re doing everything you possibly can to make this successful. I want this pilot to succeed. But if we don’t get this, it’s OK. We’ll get others. I believe in you and I trust that you are doing everything possible. Thank you.”

They doubled down their efforts and turned the pilot around, eventually winning the larger project.

So, back to the hedge fund CEO’s question: How do you reverse a losing streak? Take a breath. Then offer the support needed to perform better next time.

[image error]

Yes, Your Uber Driver Is Judging You

Companies like Uber, Airbnb, and OpenTable have been in the news lately for rating their customers — rating systems that the users themselves are not always privy to. This has caused some consumers to feel creeped out, yes, but it also got me thinking – is this even necessarily in these companies’ best interests? I called Frances Frei and Anne Morriss to ask. Both are co-authors of Uncommon Service: How to Win by Putting Customers at the Core of Your Business . Morriss is co-founder and CEO of GenePeeks. Frei is a Senior Associate Dean and the UPS Foundation Professor of Service Management at Harvard Business School. What follows are edited excerpts from our conversation.

HBR: Haven’t companies always tried to keep track of who’s a good customer and who’s a bad one?

Frances Frei: Rating customers is actually a very new phenomenon. Most organizations have a false sense of security, as in, “We have 80/20 rule – 80% of our customers are good, and maybe 20% are bad.” But they don’t actually check, and as they serve each customer, they don’t really know which is which.

What’s new about what these data- and tech-driven companies are doing?

Frei: Having the employee make the rating is a switch. A company cares about customer longevity, or how profitable the customer is. But the employee is rating the customer on, “Are you a nice customer?” So, you hear stories like the recent one about Comcast, where someone in the system to “SuperBitch,” and when her bill came, it was addressed to “SuperBitch Bauer.” She’s just a 63-year old woman who was just trying to get her cable to work. So I think it’s still unusual to give that power and discretion to employees.

One of the issues making customers uncomfortable seems to be that people don’t necessarily know they’re being rated, or what criteria the rater is going to use.

Anne Morriss: In the case of Uber, for instance, they were not at all transparent about the fact they were rating customers. It then ended up getting headlines in the New York Times, New York Magazine, Business Insider. It created all this anxiety among users, but they didn’t know how to influence the score, what behaviors were being measured.

Frei: Actually, when that all came out, Anne convinced one of the drivers to look up her rating. She found out she’s a 4.8. She became obsessed with, who didn’t give her a 5? [Laughs] So she convinced a driver to show her the rating, and she figured out that it had something to do with where she was standing at Penn station, and the GPS showing her in a different spot — something beyond her control. So in that case, the rating didn’t even lead to the behavior Uber wanted.

That’s interesting though, because Lyft says that basically anything less than a perfect 5 means someone messed up, something went wrong. That seems like a kind of grade inflation. We all want to get that perfect score, and yet what’s the point of having a five-point scale if it’s “5 is great, anything less is bad”?

Frei: It’s close to useless. For instance, we just had a guy out from a pest control company. When he leaves, he says, “A guy’s going to call and ask you to rate me, if you give anything less than a 10 out of 10 I won’t get paid for this job.” At that point, any notion that the company would be soliciting useful feedback, it’s gone.

Without a good management system, these ratings can become perverse. That’s true on the customer side and the employee side. That may not be what Uber is doing — I’m expecting they have an intelligent management system — but the bad way to do it is to blindly take the data and blindly present the data.

So what’s a better way?

Morriss: Companies need to be very strategic on how and why they’re using these scores. Let the customers know what their scores are, and train employees on how to use the rating system. You need a management system, or it becomes a way of punishing people.

Is there a technological fix as well?

Frei: With customer feedback systems, if you get a customer who only gives one-star ratings of hotels, for instance, the system will stop penalizing the hotels for getting a bad review from that customer. Similarly, if you have an employee that only ever gives one-star ratings to customers, you can stop taking that person’s ratings into account. That’s one simple example.

So that would apply to, perhaps, the Uber driver I read about who gave people bad ratings for having “negative energy.”

Frei: Right, you need to weed that out. Ratings are most effective if you get fewer, better ratings. You don’t need a rating for every transaction. A mystery shop is often better than a customer satisfaction score.

Couldn’t you argue that you just need more ratings to help balance out the flukes? That it’s just a sample size issue?

Frei: More data just makes the problem worse. People get falsely comforted by having a lot of data. You think, “Oh I heard from 100,000 people so it must be right.” But if all of the 100,000 are using their own peculiar biases, then more data are not necessarily the solution. You need a management system on top of it.

Some have speculated that aggregating customers’ scores across apps like Open Table and Uber and Airbnb could lead to a new sort of “credit score” based on how someone performs as a customer. Could you see that happening?

Frei: Of course there will be a score aggregator at some point. But “Will someone invent it?” and “Will it be useful?” are two different questions.

You know, when I first started using Uber, it was relaxing and felt like a luxury. Now, I’m worried about how I’m coming across, how I’m being judged.

Morriss: All of a sudden it’s just another place to perform, another person whose approval I need. Customers are now worried about their drivers having a great experience, to the extent that they get in the car and whatever the music is playing, it’s “This is great music!” And I don’t think that’s what the company intends for that experience, being emotionally invested in my driver’s experience. So particularly at the scale of an Uber or an Airbnb, we get to see how these fantastic intentions really play themselves out, and I think we’re going to learn from that in the next generation.

What do you think the next generation of rating systems will look like?

Morriss: If the goal here is to have a system of getting real insight into the performance of customers, that’s getting distorted. The customer experience is changing in dramatic ways based on how employees are rating customers. Companies need to think about how to protect against that.

So separate out the carrot and stick goals. Think about what kind of intelligence you need to layer on to this type of system. And then think about how to make that system, and what it’s tracking, consistent with the strategy of the organization. To me, that’s where I would go in terms of making these systems even smarter.

Frei: For both customer ratings and employee ratings, organizations need to guard against process transcending purpose. The purpose of these systems is to understand what’s really going on, so we can improve it. But process transcends purpose when Joe the exterminator says, “I don’t get paid unless you give me a 10.”

It was a great idea to solicit what customers thought, and what employees think, but that doesn’t let you off the hook from having to manage.

Morriss: We have to factor our humanity into these systems. We have to design them to account for the fact that human beings, flawed in all our glory, are going to be operating them.

[image error]

Why Workplace Accidents Tend to Happen Late in a Project

In neighborhoods all over the U.S. Northeast, desperate homeowners have been dragging extension ladders out of garages and gingerly climbing to clear their roofs and gutters of ice and snow. Along the way, they’ve been tempting fate.

Hospitals in these regions, not surprisingly, have seen a spike in people showing up to the ER with rib and spine fractures as a result of roof and ladder falls. Although it’s too early for detailed data, I’d confidently wager that the bulk of the injuries occurred not at the start of these do-it-yourself jobs, but near the end.

That’s typically how things go every autumn when homeowners climb ladders to clear the leaves out of their gutters. Nearly 200,000 emergency room visits and roughly 300 deaths are linked to ladder falls each year, according to Consumer Reports. Reaching too far is the most common cause of these accidents.

Research shows, however, that these ladder-climbers most likely started their work with caution in mind, dutifully climbing down the ladder and moving it every couple of feet, rather than risking a fall by overreaching. Trouble tends to come toward the end of the jobs. Why? It could be that the homeowner is getting hungry or is anxious to catch the Sunday NFL game. So that homeowner stretches a little more to try to reach a distant clump of leaves – and shave a few minutes off the clock. Or maybe he or she is just be getting a bit cocky, knowing that nothing bad had happened while clearing the earlier runs of gutter.

In everything from small home-improvement tasks to public infrastructure megaprojects, injuries and deaths tend to happen late in the job, when confidence runs high and tolerance for delays dips especially low. This springs from a phenomenon known as normalization, which often allows people to accept looser standards in the name of greater speed.

The more people do something without suffering a bad outcome, the harder it becomes for them to remain aware of the risks associated with that behavior. The most obvious example of this in everyday life is texting while driving. Most of us have been guilty of this risky behavior, even if we don’t want to admit it. And if we’ve never suffered an accident as a result of all of furtive thumbing from behind the wheel, we might have even fooled ourselves into thinking we’re just better at it than most people. We’re not. That’s simply the seductive yet slippery power of normalization at work.

Before I spent five years researching my book Trapped Under the Sea, the true story of a team of commercial divers sent on an impossible mission to rescue the multibillion-dollar cleanup of Boston Harbor, I intuitively assumed that the most dangerous time on a job was Day One. After all, that’s when workers are usually getting used to a new setting, new colleagues, and new equipment, and when the learning curve is steepest. However, after marinating in workplace safety data, I came to understand that the opposite is true.

In the 1980s, Boston had the dirtiest harbor in America. Today, Boston has what is widely considered the cleanest urban harbor in America, one of the most dramatic environmental transformations in recent American history. Yet it came at a deadly cost. The massive cleanup effort, which took more than a decade and cost $4 billion, claimed the lives of five workers. Tellingly, none of those fatalities happened early in the job. In fact, four of the five deaths happened at the very end of that particular phase of the project.

The deaths I focus on in Trapped involve a small team of divers dispatched to the end of the world’s longest tunnel of its kind, a 10-mile long dead-end tube carved into the bedrock hundreds of feet of below the ocean floor. This Deer Island Outfall Tunnel was the largely overlooked centerpiece of the harbor cleanup. Up to 1 billion gallons of wastewater now flows through the tunnel and out to sea every day, with gravity serving as its only power source.

Still, for the decade it took to build this engineering marvel there was electrical power, rail transportation, and ample ventilation flowing through the full length of the tunnel. These were the utilities that kept tunnel workers alive.

Yet at the very end of the tunnel construction, with the various best-and-brightest minds overseeing the project engaged in bitter battles over cost overruns, a dangerous game of corporate chicken played out. Managers decided to remove the electrical power, rail transportation, and ventilation system that had helped keep workers alive during the tunnel’s decade-long construction — yet at the end of the tunnel, 55 safety plugs still needed to be removed. To do that, managers sent a team of divers to the end of the pitch-black, oxygen-starved tunnel.

Five divers were sent in. Only three made it out alive. And even those three survivors came within 30 seconds of losing their lives as well.

How could the project’s managers, who had demonstrated remarkable skill and prudence for a decade on this job, have made such a colossally bad decision at the very end, taking unforgivable risks with other people’s lives?

Like the homeowner overreaching to clean that last run of gutter, they had fallen victim to the potent cocktail of normalization. With one part time pressure and one part overconfidence, it had clouded their ability to assess risk in any meaningful way.

[image error]

February 19, 2015

Get Your Passion Project Moving Without Quitting Your Day Job

You’ve finally figured out what you want to do with your life — start a company, launch a website, design an app, or found a nonprofit. The only problem is that you can’t afford to quit your job (and lose your benefits) in order to pursue it fulltime. So, where should you start? What’s the best way to get your passion project moving? And how can you tell when you’re ready to strike out on your own?

What the Experts Say

Knowing where your professional passions lie puts “you in a good position,” says Dorie Clark, the author of Reinventing You: Define Your Brand, Imagine Your Future. Lots of people don’t know what they want to do. “They’re struggling because they know they’re not happy doing what they’re doing, but they don’t know what else is out there.” An idea is certainly a promising start, but executing it while holding down a busy fulltime job is undoubtedly a challenge. “You’ve nailed the one percent inspiration, now it’s time for the 99% perspiration,” says Daniel Gulati, the coauthor of Passion & Purpose: Stories from the Best and Brightest Young Business Leaders. “If you are committed to making it happen, there are ways,” says Clark. So, whether you want to start a company that could become The Next Big Thing or you have a hobby that you’d like to spend more time on, here are some ideas to get your idea up and running.

Create a strategy

“Begin by sketching out exactly what it is you want to achieve,” says Gulati. Is it a large, scalable company? Is it a small company? Is it a charitable organization? “You want to have specific, concrete goals to shoot for, including revenue targets and [desired] social impact.” Next, make a timeline based on what you think you can reasonably accomplish toward your project in the time you have. “Your biggest constraint is how many hours you have to devote to this side project, so commit to an end-date [when you’d ideally like to leave your job] and solve backward from there,” he says. As you chip away on your project, continue to give your job the attention it needs. “Your day job takes precedence,” says Gulati. You must also be willing to extend your timeline if your proposed end-date doesn’t seem realistic the closer you get, adds Clark. “Be prepared to make adjustments.”

Save money

“Having financial security gives you the opportunity to build your business on your terms,” says Gulati. But if your ultimate goal is to one day leave your job and devote yourself fulltime to your project, “you will need a financial cushion” — particularly to get you through the early stages of your new venture, says Clark. Your timeline, she says, should include clearly defined savings targets for each month or quarter and — if necessary — a plan for raising money from investors. “If you don’t have sufficient funds [when you leave your job], you will make bad business decisions out of fear.”

Further Reading

How to Stay Stuck in the Wrong Career

Professional Transitions Article

Herminia Ibarra

The biggest mistake people make when trying to change careers is delaying the first step until they have settled on a destination.

Save

Share

Take control of your schedule

Perhaps the biggest challenge is finding time in your busy schedule to work on your project. A good starting point, says Clark, is to begin keeping a time log. “Look at how you’re spending your time, and make sure you’re using it the way you want to,” she says. The log will ideally help you discover valuable stretches of “free time that you’ve either missed or not accounted for” that could be channeled into your new endeavor, she adds. If after looking at your log, you’ve uncovered very little wiggle room, you might explore the idea of outsourcing parts of your project to a paid helper, says Gulati. For instance, can you hire someone to help you code? Or pay a freelance consultant to do market research? “If you’re cash-rich and time-poor, look for opportunities to trade money for time,” he says.

Patch weak spots

Clark recommends listing the “concrete skills you need to develop in order to be successful at pursuing your passion full-time.” Once you have a list of necessary skills, figure out how to acquire them. Perhaps you need to take a class; maybe an internship or apprenticeship is in order. Clark suggests identifying ways to “stretch your job description” to learn new skills. For example, if knowing how to build websites will be important to your new venture, see if your current job will subsidize a class in web design that will also help you in your current job. “It should be win-win for your company,” she says. Your goal, adds Gulati, is to make the case: “This side project is a form of learning that helps me do my day job.”

Ask for flexibility

It’s not out of the question that your boss may even give you leeway to work on your venture, according to Clark. “Read the culture of your organization” to get a feel for whether or not people would be supportive, she says. “If others have flexibility for personal reasons” — say they coach their daughter’s soccer team, they take guitar lessons, or they are writing a book — “you may be able to have flexibility to pursue a vocational passion, too.” And you may have more leverage if you’re a valued employee and your boss is concerned you’ll leave. “It’s a judgment call,” says Gulati, as to whether you alert your boss and peers to your intentions. Another option is to see whether you can take an unpaid leave of absence without losing your benefits, he says. “Being able to work on [your project] for a big block of time is an opportunity to really accelerate the pace of your progress and get it to the next big milestone.”

Don’t be sneaky

In most cases, there’s no need to be overly secretive about your project at work. Clark says that being honest makes what you’re doing “less suspicious and more legitimate.” When talking to others, “frame your project in a way that shows value to your company because you are learning new skills that you can apply to your current job,” she adds. After all, your current coworkers represent a “ready-made network of colleagues who can help you think through your idea and give you feedback,” says Gulati. They are also “your biggest allies” and the first port of call for reference checks from potential investors. “It’s in your best interest to be transparent,” he says, adding that “externally committing” to your project increases accountability and “ups the ante for you.” That said, many people at work will naturally “be skeptical,” he says. “There is a default assumption that this [project] is going to take up time and hamper your performance. You need to make sure it doesn’t impact your day-to-day work.” If you think that your boss or colleagues may be less than supportive, talk with family and friends about the project instead.

Be brave

There comes a time when you have to ask yourself, says Gulati: “By virtue of doing your project on the side — and not spending all of your time on it — are you robbing yourself of success?” It’s a question only you can answer, of course. “Following your passion might seem daunting,” says Clark. “But if you’ve planned your transition well, you’re not taking a heedless risk.” Instead, she says, you’re making an “investment in your happiness and in your future.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Build up a financial cushion before you leave your fulltime job

Look for creative ways to make headway on your project either by making better use of your free time, taking a leave of absence from your job, or outsourcing some tasks to others

Seek out training opportunities to help you develop the skills you need for your project

Don’t:

Let your primary professional obligations slip — your day job takes precedence

Be overly secretive about your project — current colleagues could help you think through your idea and give you valuable feedback

Leave your job without a strategy — plan your transition so that you’re not taking a heedless risk

Case study #1: Create financial flexibility for yourself and commit to an end date

Kate Blanchard had a great job at PerkinElmer, the Massachusetts-based multinational, but she was eager to build something of her own. “I wasn’t unhappy at PerkinElmer — I had a resources, infrastructure, a good team, and the opportunity to really influence — but I felt inspired to create something new and be in complete control of my own path,” she says. Kate had had a taste of entrepreneurial life — she was on the management team of ArtusLabs, the North Carolina-based software company that was bought by PerkinElmer in 2011 — and knew how “exciting it was to work at a start-up.”

Thanks to her own foresight, Kate had financial flexibility to start a new business. “The only reason I could even think about doing something like this is that early in my career was because I was living beneath my means,” she says. “I knew I wanted to be free to make these big decisions.”

In 2013, she and Robin Smith — a former colleague from Artus Labs — began exploring ideas. They “carved out time on nights and weekends” to do research and market analysis. And Kate soon came to the conclusion that she couldn’t continue to work fulltime and focus on her side project. “I couldn’t service my day-job if I was always thinking about something else.”

Kate committed to an end-date six months down the road. While she chose not to tell her colleagues about her future plans, she spent that time shoring up her team at PerkinElmer so that when she ultimately gave notice it would be a seamless transition. During those six months, Kate admits doing an occasional “gut check” about her decision. “I wrote out a list of pros and cons, and I thought about what I liked about [PerkinElmer] and my next move.”

Kate left her job at PerkinElmer in February 2014; the next month, she and her business partner started ORIGƷN, a Boston-based biotechnology company. It currently has nine employees and will have 12 by the end of next month. “It’s an exciting time,” she says. “I made the right decision. I have no regrets.”

Case study #2: Solicit ideas (and maybe funds) from others and maximize free time

Dan Hogan was working in technology sales when he got the idea of starting a home healthcare agency — a company that sends nurses and therapists to a patient’s residence for rehabilitation. A former colleague of Dan’s had made a similar move. “Watching him do it gave me confidence that I could go ahead and make the leap too,” says Dan. He made up his mind that within nine months, he would leave his company. It was a trying period, he recalls. “Ultimately you’re serving two masters by working two jobs.”

He mainly worked on his project on weekends but he also spent time on it during lunch breaks and in the evenings. “Rather than spending time on Facebook or goofing off surfing the web, I realized I could use that time to focus on my idea,” he says. “I did 15 minutes of market research here and there, and squeezed in five-minute calls while walking around the block. I was shocked at the progress that I made.”

Dan says he constantly talked about his business idea with family and friends. “Talking about it made the idea visible and that created a momentum of its own,” he says. “It also made me accountable.”

Some of these conversations revolved around money. Dan was saving money on his own, but he knew he needed more funds to launch his business. The day he quit his job he had lined up 18 investors — including his college roommate and his cousin—for a total of $150,000. “I didn’t want to disappoint them,” he says. “It made everything all the more real because I had all these people who were on the line with me.”

Five years later, Dan’s healthcare company — Doctor’s Associates — had 500 patients and over 100 full- and part-time employees. He sold that company and started a new one. Today he is the CEO of Medalogix, the Nashville-based health IT company, that has raised just under $7 million in financing.

[image error]

What Happens If Apple Starts Making Cars

Apple fanboys and Samsung’s “Next Big Thing”ers would hoot with derisive laughter if The Wall Street Journal or Financial Times reported that GM or Ford planned to rewrite the rules of smartphone innovation. But when media coverage suggests Apple may redesign the automobile, even the most cynical car-lovers quiver with righteous curiosity. They should.

Could Sir Jonny Ive be the next Battista Pininfarina, Harley Earl, or Akihiro Nagaya? Don’t bet against him. Steve Jobs’ successors are at least an order of magnitude more credible as disruptive innovators than the heirs of Ford and Sloan. The computer, software, telecoms, music, broadcast, publishing, photography, retail, and consumer electronics industries certainly believe so. Apple demonstrably understands design, UX, and global supply chain alignment in ways few organizations ever have. According to data from Yahoo finance, company’s market cap exceeds that of Toyota, BMW, Volkswagen, Ford, GM, Honda, Fiat Chrysler, Tesla, and Daimler combined. Apple’s cash hoard currently tops $175 billion.

If Apple truly wants to fundamentally transform the driving experience and global automobile business, it surely has the ingenuity and resources to do so. Super-investor Warren Buffett’s admonition that “When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact” doesn’t apply. Unlike commercial aviation, automobile economics brilliantly reward the brilliant. Apple is brilliant. Don’t bet against them.

Who knows what an iCar might look, feel, or drive like? I don’t. But the better and more challenging question is, how would the automotive industry’s incumbents respond to genuinely disruptive competition? How might the industry splinter, shatter, or consolidate when truly well-endowed innovators commit to upending expectations around the DX — the Driving Experience? The money, frankly, is secondary; the real issue is creativity and capability.

Consider what happened with the iPhone. Incumbents Nokia and RIM—the handset status quo—collapsed into irrelevance. They simply couldn’t compete. By contrast, entrepreneurial non-incumbents like Google counterattacked with Android. Samsung and Xiaomi—a company that didn’t even have a smartphone five years ago—quickly became dominant players.

No, an automobile is not just an iPhone with wheels. But is GM a Blackberry and Ford a Nokia when Apple competes with a DX, a business model, and an iCar “genius bar” support network that makes their offerings look last century?

The failure of Shai Agassi’s Better Place and the ongoing production challenges confronting Elon Musk’s Tesla underscore how hard being an entrepreneurial 21st Century automobile start-up can be. Musk, whose company is reluctant to hire people from the industry, has bitingly observed that his established automotive competitors are innovation laggards. “I had thought the big car companies would be coming out with electric cars sooner,” he observed in late 2014. Their failure to do so was “mind blowing.”

But Apple would deny any and every incumbent their “too small to matter” excuse for inertia. Indeed, precisely because Apple knows how to profitably scale its design, UX and supply chain expertise, automobile manufacturers would be compelled to react and respond. Traditional retailers smirked and cried “niche!” when Ron Johnson began rolling out Apple Stores in 2001. Yet those stores have successfully redefined retail norms and customer expectations well beyond Apple products and services. Apple dramatically influenced even its indirect competitors.

So put aside its brand equity. Apple’s command of UX and technical infrastructure create multiple opportunities to transform the economics and expectations of every value-added aspect of the automobile experience. Building a car is the least of it. Apple needn’t build a car any more than it must build an iPhone or an iPad (thanks, Foxconn). All Apple has to do to force fundamental industry restructuring is do what the incumbents have not—redesign the end-to-end purchase and DX, not just the cars themselves.

That’s a bold vision for an entrepreneur, but a revitalizing challenge for a post-Jobs Apple. A partnership with Uber, for example, could be as DX transformative as special arrangements with the traffic management authorities in Beijing, London, Los Angeles, and New Delhi. How might Apple leapfrog or reframe Google’s autonomous vehicle approach to DX? Even a modest Apple incursion into the automotive industry would likely prompt an entrepreneurial explosion of innovation—and innovative—partnerships. To what extent might an automotive counterpart of “apps” and the “app store” generate new automotive expectations and value?

Indeed, it’s easy to see how a Google has as much or more incentive than Apple to “own” tomorrow’s DX as the future of personal mobility and sustainability evolves. After all, Google’s Waze is already evolving into an indispensable global DX standard. More difficult to anticipate is how a Toyota or Ford or Volkswagen will respond. These companies haven’t had to respond to a truly disruptive innovator in over forty years.

Toyota, without question, is the real incumbent to watch. If Apple drives into the automobile marketplace, Toyota has the most to lose. Between the Lexus and the Prius, Toyota’s the one dominant market leader that consistently respects design and business fundamentals even as it innovates.

Even if it never built a single car, Apple would likely prove the most serious and worthy competitor Toyota ever confronted. Toyota knows that Apple could design, build and deliver a DX that Toyota’s best customers would like. Maybe it wouldn’t be a “car”….but it would be something that redefined how people thought and felt about what it means to buy, own, and drive a car.

I bet BMW, Volkswagen, and Ford know that, too. The question is, what are they going to do about it? Will the incumbents wait and see? Or will they take the wheel?

If Apple hits the accelerator on its DX option, the next ten years of automobile innovation will be more interesting than any ten years of the automotive past.

[image error]

Why It’s So Hard to Figure Out What to Pay Top Talent

“It’s harder than ever to hire the right people.” It seems like almost every company today shares some version of this lament, and for good reason: Research shows that many have open positions for 12 months or more. Often, that’s not because the talent isn’t out there; rather, it’s because a company’s approach to compensation hasn’t evolved to be effective in today’s rapidly changing talent market.

Traditionally, compensation models have been shrouded in secrecy, with the employer holding all the cards. However, a few big changes over the past five years have left companies off balance and unprepared to compete for talent effectively. There are several factors at play:

More jobs are becoming highly specialized as technology advances and “micro-industries” evolve. Think about the advent of the petrophysicist or the hydrocarbon mud logger in the oil and gas industry. These are jobs that didn’t even exist several years ago. As a result, it’s harder to compare one candidate to others in the market, when there may only be a sample size of two or three with the same, precise qualifications.

It’s no longer uncommon for a single team to be distributed across the world. Because of this, determining salary is no longer as simple as calculating the relative cost of living in your geography (i.e. jobs in New York City pay X% more across the board than jobs in Topeka, Kansas). Physical location may no longer be the primary factor that drives pay for a specific job.

Increasingly, a talent market transcends not only geographies, but also multiple industries. It used to be that only leading technology firms like Microsoft, IBM, Oracle or SAP hired software engineers. Now, posted software engineering jobs are legion at financial, aerospace, and energy companies, to name just a few. Likewise, large churches and religious organizations now compete with established entertainment companies like Disney or Paramount for producers and highly experienced creative professionals.

Employees and candidates are more informed than ever about what they’re worth thanks to social networks and online compensation services (like the one I work for). And, as younger employees fill more positions in the workplace, they tend to expect more transparency from managers about the way their compensation has been determined. Because of this, employers need to be better prepared to back up their compensation offers with real data.

In the end, and in part due to the factors above, the single biggest driver of compensation today is not the job title, but rather a specific candidate’s own skills, achievements, and capabilities. Increasingly, these skills are most valuable when they are documented or certified. In many industries, the required skills are constantly evolving, so some credentials that are hot today weren’t in demand several years ago. An example is the web application framework Ruby on Rails. Over the last five years, demand for Ruby on Rails has quadrupled. As a result, the salaries have responded to market demand and developers who have Ruby on Rails skills are compensated at nearly $18,000 more annually than their peers without this capability, all other compensable factors being equal. This is a significant increase over just one year ago when Ruby developers made about $10,000 more than their “non-Ruby on Rails” peers.

Because of these factors, it’s no longer good enough for hiring managers to play it by ear or approach compensation as a dark art. This requires a cultural evolution for companies that used to rely on gut feel when it comes to compensation. Firms that want to attract somewhat elusive highly skilled and highly desirable professionals (a “purple squirrel” or “unicorn” in HR circles) need to get serious about getting pay right.

For positions that are in demand — such as many IT and engineering jobs — hiring managers may find they need to pay 10 to 20% more than they anticipated to attract the right employees. And in some cases, these people are being lured from industries that are completely different from yours, and thus have different expectations about pay.

And while it’s important to price your jobs according to your compensation budget, it’s more important to understand various attributes will drive different pay requirements. It’s no longer good enough to say, “Accountants are paid $85,000.” For example, how much more should you pay a candidate with 12 years of experience, with specific certifications, located in Boston, and with relevant experience in the technology industry? Employers need to become more precise about their offers to attract and retain the right talent. Analyzing real-time data from many markets on an ongoing basis will ensure you’re educated on the realities of who, exactly, you’re looking to attract. And when you find the right person, you’ll know how much to pay at the exact moment in time the offer is being made.

[image error]

Is Your Employee Coachable?

As a manager, you provide some level of coaching to all your direct reports, helping some attain higher levels of professional achievement, and helping others improve their performance to fulfill their current roles. But while every manager should have the capability to coach, you also need to have the ability to discern when coaching isn’t working.

When your direct report isn’t improving despite your best efforts, you need to consider whether that person is coachable. “Coachability” requires two things of your direct report:

She needs to demonstrate a commitment to her development. That means she will be more willing to accept feedback, more willing to try something new, and more willing to confess if she didn’t do something right—because she sees that moment as a learning opportunity.

She needs to have capacity to get to the skill level you want her to reach. For example, you could want to be a professional basketball player, but no matter how hard you practice, you may not get into the NBA.

If your direct report doesn’t seem to be improving, don’t assume the worst. Skills don’t often improve right away, so first check for #1, the willingness factor. Is she showing up for meetings? Coming prepared? Is she taking the lead and following up with you? Is she addressing action items you have defined together? Is she owning the feedback you are giving her–or does she act defensive? If she is, as the coaching process progresses, you can start to watch for improvement in capabilities and outcomes.

If she’s not, she may not be in a place where coaching can to help. Discuss this with her to let her know what you’ve observed, and to explore with her how committed she is to her development along this particular path.

It’s also common for a coachee’s motivation to begin to wane even after she begins the coaching process enthusiastically. She may start canceling your check-in meetings; she may not address all of the action items you’ve agreed on; you might keep discussing the same things over and over again. This is a key moment for you, the manager, to check in with her. “You seemed eager and committed when we began working on this skill,” you can ask, “Now it’s lagging—what’s behind that?” This opens up the door for a great coaching conversation.

A manager I know was working with a direct report on building the skills he needed for a promotion. She became concerned that she wasn’t seeing him improve, and that he wasn’t even coming to see her or ask her questions, or report on his progress. Finally she sat him down and talked him through what he really needed to do. But above all, she said, “I know we’ve been at this for a while and I feel like you are getting discouraged—and it’s diluting your commitment to the process. Is that how you are feeling?” It turned out that he had thought she was very busy and wouldn’t want to hear from him. They were able to clear up the misunderstanding and he made it very clear how enthusiastic he was about the work he was doing. It wasn’t all easy for him from there, but they were able to talk more openly about his progress.

If your direct report’s enthusiasm is high but her capabilities still don’t seem to be improving—she’s not showing even incremental progress toward the goals you have set–that may be a sign that she is not coachable on this skill. Again, find out more before calling it quits. Talk to her about the fact that she is not meeting your expectations, and ask questions so that she can explain her own perspective on the situation. “The needle hasn’t moved on these skills we’ve identified as important. Were the expectations we set earlier too high or unrealistic? Or is it that you need to put in more effort? Is there a different way that you can learn this?”

If you’ve tried every way you can think of to move your direct report in a particular direction and it’s just not working, consider alternatives such as a third-party training, or having someone else on your team provide the coaching (if you’ve had a tumultuous history, for example, the lack of trust can make it hard to get into a coaching relationship).

Sometimes the issue that your employee is grappling with may even take psychological therapy or counseling, especially if it is a general behavior rather than a specific skill. One manager I know had a direct report who was starting to miss a lot of deadlines just around the time their company was moving offices. He began coaching her on her productivity but instinctively felt that there was something deeper going on. As things progressed with the move, it became clear that she was very protective of the enormous number of files and objects that she kept in her office and she became very emotional at the thought of having to part with them. After the move, he referred her to the employee assistance program to help her address what had been a difficult situation. It turned out that she was diagnosed with an obsessive-compulsive tendency to hoard. This was far beyond what he could or should deal with as a manager.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Coaching

Managing People Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

It can often be difficult to even begin to assess whether this kind of intervention is needed because you don’t want to place judgment on the person. If you feel comfortable you can ask, “Have you thought about getting assistance in other ways?” But how you talk with them about this depends on the person and your relationship. In any case you should confer with your HR department before bringing up any more sensitive forms of treatment.

If she still doesn’t make progress, you will need to make a decision about whether she is the right person for this particular task or responsibility. If the issue you are trying to coach toward is a specific capability rather than a behavior, but your direct report is just not picking up the skills fast enough, despite having the willingness, consider redirecting her energies to skills that she does have. Shift her role if you need to. As long as that willingness is there, you have someone whom you want to support.

Acknowledging when someone isn’t coachable and finding more appropriate next steps to help her develop—or to just letting her maintain her status quo—can save you a lot of time as a manager, and sometimes it’s just what your direct report needs.

[image error]

Where the Digital Economy Is Moving the Fastest

The transition to a global digital economy in 2014 was sporadic – brisk in some countries, choppy in others. By year’s end, the seven biggest emerging markets were larger than the G7, in purchasing power parity terms. Plus, consumers in the Asia-Pacific region were expected to spend more online last year than consumers in North America. The opportunities to serve the e-consumer were growing – if you knew where to look.

These changing rhythms in digital commerce are more than a China, or even an Asia, story. Far from Silicon Valley, Shanghai, or Singapore, a German company, Rocket Internet, has been busy launching e-commerce start-ups across a wide range of emerging and frontier markets. Their stated mission: To become the world’s largest internet platform outside the U.S. and China. Many such “Rocket” companies are poised to become the Alibabas and Amazons for the rest of the world: Jumia, which operates in nine countries across Africa; Namshi in the Middle East; Lazada and Zalora in ASEAN; Jabong in India; and Kaymu in 33 markets across Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.

Private equity and venture capital money have been concentrating in certain markets in ways that mimic the electronic gold rush in Silicon Valley. During the summer of 2014 alone $3 billion poured into India’s e-commerce sector, where, in addition to local innovators like Flipkart and Snapdeal, there are nearly 200 digital commerce startups flush with private investment and venture capital funds. This is happening in a country where online vendors largely operate on a cash-on-delivery (COD) basis. Credit cards or PayPal are rarely used; according to the Reserve Bank of India, 90% of all monetary transactions in India are in cash. Even Amazon localized its approach in India to offer COD as a service. India and other middle-income countries such as Indonesia and Colombia all have high cash dependence. But even where cash is still king, digital marketplaces are innovating at a remarkable pace. Nimble e-commerce players are simply working with and around the persistence of cash.

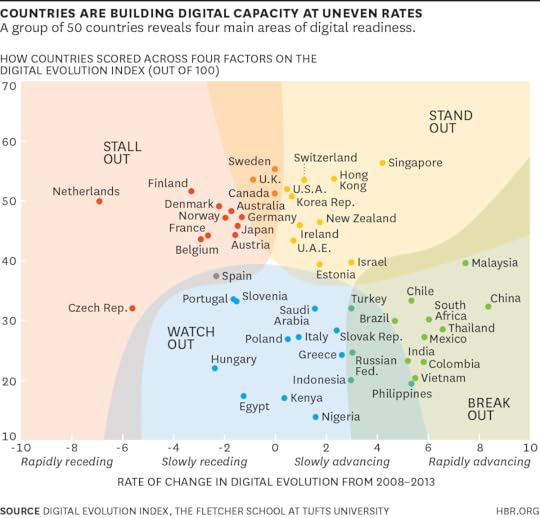

To understand more about these types of changes around the world, we developed an “index” to identify how a group of countries stack up against each other in terms of readiness for a digital economy. Our Digital Evolution Index (DEI), created by the Fletcher School at Tufts University (with support from Mastercard and DataCash), is derived from four broad drivers: supply-side factors (including access, fulfillment, and transactions infrastructure); demand-side factors (including consumer behaviors and trends, financial and Internet and social media savviness); innovations (including the entrepreneurial, technological and funding ecosystems, presence and extent of disruptive forces and the presence of a start-up culture and mindset); and institutions (including government effectiveness and its role in business, laws and regulations and promoting the digital ecosystem). The resulting index includes a ranking of 50 countries, which were chosen because they are either home to most of the current 3 billion internet users or they are where the next billion users are likely to come from.

As part of our research, we wanted to understand who was changing quickly to prepare for the digital marketplace and who wasn’t. Perhaps not surprisingly, developing countries in Asia and Latin America are leading in momentum, reflecting their overall economic gains. But our analysis revealed other interesting patterns. Take, for example, Singapore and The Netherlands. Both are among the top 10 countries in present levels of digital evolution. But when we consider the momentum – i.e., the five-year rate of change from 2008 to 2013 – the two countries are far apart. Singapore has been steadily advancing in developing a world-class digital infrastructure, through public-private partnerships, to further entrench its status as a regional communications hub. Through ongoing investment, it remains an attractive destination for start-ups and for private equity and venture capital. The Netherlands, meanwhile, has been rapidly losing steam. The Dutch government’s austerity measures beginning in late 2010 reduced investment into elements of the digital ecosystem. Its stagnant, and at times slipping, consumer demand led investors to seek greener pastures.

Based on the performance of countries on the index during the years 2008 to 2013, we assigned them to one of four trajectory zones: Stand Out, Stall Out, Break Out, and Watch Out.

Stand Out countries have shown high levels of digital development in the past and continue to remain on an upward trajectory.

Stall Out countries have achieved a high level of evolution in the past but are losing momentum and risk falling behind.

Break Out countries have the potential to develop strong digital economies. Though their overall score is still low, they are moving upward and are poised to become Stand Out countries in the future.

Watch Out countries face significant opportunities and challenges, with low scores on both current level and upward motion of their DEI. Some may be able to overcome limitations with clever innovations and stopgap measures, while others seem to be stuck.

Break Out countries such as India, China, Brazil, Vietnam, and the Philippines are improving their digital readiness quite rapidly. But the next phase of growth is harder to achieve. Staying on this trajectory means confronting challenges like improving supply infrastructure and nurturing sophisticated domestic consumers.

Watch Out countries like Indonesia, Russia, Nigeria, Egypt, and Kenya have important things in common like institutional uncertainty and a low commitment to reform. They possess one or two outstanding qualities — predominantly demographics — that make them attractive to businesses and investors, but they expend a lot of energy innovating around institutional and infrastructural constraints. Unclogging these bottlenecks would let these countries direct their innovation resources to more productive uses.

Most Western and Northern European countries, Australia, and Japan have been Stalling Out. The only way they can jump-start their recovery is to follow what Stand Out countries do best: redouble on innovation and continue to seek markets beyond domestic borders. Stall Out countries are also aging. Attracting talented, young immigrants can help revive innovation quickly.

What does the future hold? The next billion consumers to come online will be making their digital decisions on a mobile device – very different from the practices of the first billion that helped build many of the foundations of the current e-commerce industry. There will continue to be strong cross-border influences as the competitive field evolves: even if Europe slows, a European company, such as Rocket Internet, can grow by targeting the fast-growing markets in the emerging world; giants out of the emerging world, such as Alibaba, with their newfound resources and brand, will look for markets elsewhere; old stalwarts, such as Amazon and Google will seek growth in new markets and new product areas. Emerging economies will continue to evolve differently, as will their newly online consumers. Businesses will have to innovate by customizing their approaches to this multi-speed planet, and in working around institutional and infrastructural constraints, particularly in markets that are home to the next billion online consumers.

We may be on a journey toward a digital planet — but we’re all traveling at different speeds.

[image error]

A Formula to Stop You from Overcommitting Your Time

When I dive into time coaching clients’ schedules, I consistently discover that people misdiagnose themselves as having a “productivity” problem when, in fact, their bigger issue is an overcommitment problem. When they have committed to more external projects and personal goals and obligations than they have hours for in the day, they feel the massive weight of time debt. One of my coaching clients suffered from a huge amount of false guilt until he realized he had the unrealistic expectation that he could fit 160 hours of tasks into a 40-hour workweek.

Effective time investment begins with accepting the reality that time is a finite resource. This acknowledgment frees you to make choices about what you will and won’t do so you can invest more in what’s most important, feel good about what you do and don’t get done, and still have disposable time left to relax and enjoy yourself. As one of my time coaching clients put it, “I’ve realized there’s only X amount of time, so I need to invest in my priorities and understand that when I choose one activity, I’m not choosing another.”

The single most important factor in feeling like a time investment success or failure is whether or not your expectations of what you will accomplish align with how much time you have to invest. The following time investment formula provides a mathematical way to understand the relationship between your expectations and your actual time budget. Once you have this data, you can then determine exactly what you need to do to get to a balanced budget in which you have enough time for what’s most important.

Time investment success

(External expectations) + (Internal expectations) ≤ 24 hours — (Self-care)

Time debt stress

(External expectations) + (Internal expectations) > 24 hours — (Self-care)

Look at the successful side of the time investment formula. On that side, there’s one fixed value, the twenty-four hours in a day, and one variable, the amount of time needed for self-care. For the purpose of this exercise, “self-care” is the most basic of wellness activities you do on a regular basis: sleeping, eating, and personal grooming, that is, showering, brushing your teeth, and so on.

Here’s an example of this breakdown:

Sleeping—seven hours

Eating—one hour

Personal grooming—two hours

Total—ten hours

On a piece of paper or electronic document or note, add up the hours you need to spend on sleeping, eating, and personal grooming. If you want to do so, you can include more self-care categories, but make sure that you limit these values to only the necessities in order to get the most accurate tally of your available time per day.

Once you have quantified the “fixed expense” of self-care, subtract it from twenty-four hours to come up with your daily time budget. There can be some variability in this number from day to day, but you want to determine your sustainable baseline.

Example of a daily time budget

24 hours — 10 hours = 14 hours

After you’ve calculated your time budget, total up the time costs related to your external and internal expectations. External expectations include commitments to others, such as spending a certain amount of time at work or attending family events; internal expectations are commitments to yourself, such as wanting to exercise or read. Here are some potential areas to consider:

External expectations:

Work

Commute

Relationships

Pet care

School/training

Related homework

Recurring meetings

Leadership/committee responsibilities

Internal expectations:

Personal development

Hobbies, side projects

Travel

Finances

Prayer, meditation

If most of your commitments recur daily, then the values for expectations in each category of your life can be based on a twenty-four-hour day. For example, you may put down nine hours for work and two for hobbies or side projects.

If you have a fair amount of variance from day to day, it may be more effective for you to craft a weekly time budget. To come up with your weekly time budget, multiply your daily time budget by seven.

Example of a weekly time budget

14 hours x 7 days = 98 hours

Then, figure out the weekly time cost for your internal and external expectations. For example, allocate forty-five hours for work to reflect the fact that, on average, you invest that much time in the “work” category each week—both in and out of the office—and only five hours for side projects.

Adapted from

How to Invest Your Time Like Money

How to Invest Your Time Like MoneyBook

6.99

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Take time to write down your numbers for each category of your life and then total them. If you’re unsure how you spend your time, look back at your calendar or planner. If those don’t provide an accurate enough reflection of your time allocation, write down your expected time allocations for the upcoming week.

Now comes an important moment of truth: it’s time to determine how closely your expectations align with the reality of your time budget. Plug your time costs for external and internal expectations into the left side of this formula and your calculated daily or weekly budget into the right side of the formula.

(External expectations) + (Internal expectations) ____ (Time budget)

Then fill in the blank between the two sides with a “>,” “<,” or “=” sign.

If you’re like most people, you’ll end up choosing the first of the three options—the greater-than sign—because you’ve made more external and internal commitments than you can realistically keep. This has created a lot of guilt and stress for you in the past. But now that you’re aware of what’s happening, you can adjust for the future.

This post is adapted from the Harvard Business Review Press book How to Invest Your Time Like Money.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers