Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1316

February 24, 2015

Use Your Staff Meeting for Peer-to-Peer Coaching

One of the unintended consequences of the constant right-sizing and flattening of our organizations is that we now live in a world where managers just don’t have time to do all that’s required of them in their daily jobs, let alone find time for coaching their employees.

Yet coaching is a critical job for any manager who wants to improve her team’s performance. Research shows that training alone can improve performance by 22%, while training accompanied by coaching (that is, collaborative problem solving, feedback, and evaluation) can improve performance by 88%.

So what are time-constrained leaders to do?

In our research at Ferrazzi Greenlight, we’ve found an extraordinarily rich and robust coaching resource sitting around us each and every day — our peers. And the ideal venue for peer-to-peer coaching is already built into our schedules — the staff meeting. You can use staff meetings the way a sports coach uses practice time: to run new plays and build new, better habits. The time devoted to coaching during staff meetings can also propel team members to encourage each other “off the court.”

The staff meeting is one of the only times when all of the “players” are together on the field. It’s also the one time the manager has total control of the agenda and can micro-coach the movements of the team, so that new muscle memories are built under her watchful eye. On a winning sports team, the coach certainly spends time with individual players, but also has group practices where the team runs plays with the coach, who sometimes gives the entire group advice, and sometimes singles out individuals. Coaches then do the same during actual games.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Coaching

Managing People Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

The locker room conversations and peer-to-peer encouragement and correction that happen among great sports teams occur because the best athletes know that it’s not just individual performance that matters — it’s the collective team performance. If they fail, they fail together. Our research has shown that the same peer-to-peer dynamic can be used in business as a powerful driver of performance.

We recommend these ways to unleash effective peer-to-peer coaching in staff meetings:

1. Shift the meeting from report-outs to collaborative problem solving.

Change the structure of the meeting from individuals reporting their own performance and successes to collaborative problem solving, where the leader or a member of the team brings a topic for group discussion.

The importance of this exercise is that team members begin to see their peers as a rich source of advice — one that they might not have gone to before. This type of collaborative problem solving usually yields better decisions — and is a more enjoyable way to work. Just be sure to follow a few rules:

Set the topics in advance.

Distribute a one-page topic description beforehand for people to reflect on, which includes a specific question that you want the group to address.

In the room, break into small groups of three or four to debate the topic, in order to gain higher degrees of candor.

Don’t take decision-making control away from the individual who brought the question to the table. This should be a rich source of diverse input, not an abdication of the responsibility to the group, and not an exercise in reaching consensus.

2. Facilitate periodic, open 360-degree reviews.

In “Open 360s,” each team member gives very honest, constructive feedback to peers. The sessions are designed to get individual feedback and instill greater candor and intimacy within the team in a safe, and even caring, fashion.

Each individual hears from everyone at the table about what they admire most about his or her performance for no more than 30 seconds each. This sets up respect and safety and helps the individual welcome input from team members. Then, there is a second go-round where individuals offer constructive criticism. This time, each person shares in this way: “Because I care about your success, and your success is critical to this team’s success, I might suggest … ”

Here are a few rules of thumb for the person receiving the feedback:

After each go-round, you may ask clarifying questions. You may not be defensive. You may not push back.

There is no obligation to change. You don’t necessarily have to do anything with what’s suggested to you.

At the end, say, “Thank you,” and recognize that all this data is yours to chew on and do with what you will.

This exercise is a smart way to open up, through a formal process, the peer-to-peer feedback that should exist at all times. It also helps people see that their team members are resilient and that, perhaps, they can accept this kind of feedback at other critical times. When you couch feedback in service of others, instead of punitively or judgmentally in service of oneself, you lead with the affirmative and establish a level of respect that breaks down potential hostilities.

Professor James O’Toole and my late friend-professor Warren Bennis found in their research that teams who practice and exhibit candor in the workplace outperform their counterparts. They also discovered that whatever momentary discomfort leaders and employees may experience is more than offset by the fact that the unveiled information helps them make improved decisions.

3. Give ‘em homework and hold ‘em accountable.

Have each person in the room identify one behavior that they personally want to work on between now and the next meeting. Have everyone “buddy up” with another person in the room and require that, between now and the next meeting, they speak by phone, or in person, two or three times to check in on progress on their self-selected goal. As the leader, you have to assure that this offline peer coaching actually occurs by asking individuals to share their successes, or to request additional peer support if they feel stuck.

As leaders, we all know that we need to do more coaching. So let’s use the forum we’ve already established — the staff meeting — to encourage our team members to complement our efforts. Those who adopt this strategy may find themselves on the rare dream team where members can look at each other across the table and can say, “I’m not going to let you fail.”

Want to help with our research? Please answer this survey so we can see how many companies perform these practices.

[image error]

What CEOs Are Afraid Of

Deep-seated fears — of looking ridiculous, losing social status, speaking up, and much, much more — saddle children in the middle school lunchroom, adults on the therapist’s couch, and even, my research has found, executives in the C-Suite. While few executives talk about them, deep and uncontrolled private fears can spur defensive behaviors that undermine how they and their colleagues set and execute company strategy.

In 2014, I surveyed 116 CEOs and other executives, interviewing 27 in depth afterwards. Of the 116 survey participants, 73% were male, 27% were female, and all but 9% were based in Europe. About a third (32%) were CEOs or presidents; 31% were division/business unit heads; 30% were senior managers reporting to division/business unit heads; and 7% were in investment or professional services firms.

What I found about executives’ fears and their impact in the boardroom was revealing, and in some cases astonishing:

The biggest fear is being found to be incompetent, also known as the “imposter syndrome.” This fear diminishes their confidence and undermines relationships with other executives.

Their other most common fears, in descending order, are underachieving, which can sometimes make them take bad risks to overcompensate; appearing too vulnerable; being politically attacked by colleagues, which causes them to be mistrustful and overcautious; and appearing foolish, which limits their ability to speak up or have honest conversations.

About 60% said those first three fears affected behaviors on their executive team, although 95% said that executive team members had a very limited view of their own fears. About two-thirds believed they had “some” self-awareness.

The five top fears resulted in these dysfunctional behaviors: a lack of honest conversations, too much political game playing, silo thinking, lack of ownership and follow-through, and tolerating bad behaviors.

Asked to think about the fallout from those dysfunctional behaviors, the executives mentioned more than 500 consequences. Those mentioned most frequently were poor decision-making, focusing on survival rather than growth, inducing bad behavior at the next level down, and failing to act unless there’s a crisis.

The 27 executives whom I interviewed spoke candidly about their own fears. The most frequently mentioned fears were losing their reputation, underachieving (even among seasoned executives), and dying, both literally and in their career, and how it inspires a fixation on status, appearing youthful, and making money. Ten spoke at length about how greed at the top inspires greed (sometimes disguised as ambition, which is more socially acceptable) among lower-ranking executives. Two-thirds said their company’s executives were unable to talk directly to one another and even lied at times.

Many of their quotes are poignant and telling: “Greed. It controls everything.” “If someone told the truth they would be isolated.” “You’ve got to look virile.” “You know what? [A new CEO] was frozen by fear. He couldn’t think straight.” “He [the CEO] would publicly humiliate them, bully them [senior executives].” “We are competitive so there is less honesty.” Five executives in their 50s (four of them millionaires and all with stable families) admitted that they feared retirement.

Other studies have shown that such fears disrupt the healthy functioning of executive teams and whole companies. Noted INSEAD leadership professor Manfred F.R. Kets de Vries wrote in 2014 that anxiety over death often causes workaholic behavior. Through studies of adults, professors Tomasz Zaleskiewicz, Agata Gasiorowska, Pelin Kesebir, Aleksandra Luszczynska, and Tom Pyszczynski have proposed that money alleviates death anxiety. So greedy workaholics are really trying to stave off death, and the 50-something executive who fears being put out to pasture may fixate on a merger that stakes him with a big payoff, even if it’s not in the company’s best interest.

Fear is inevitable, but it doesn’t have to poison an organization. I have found seven approaches to be effective at reducing such fears:

The CEO should be aware of his or her own fears and those of the team, and committed to building a strong organization.

Organizations should value emotional intelligence as a key executive attribute. One financial services company’s business unit CEO has great emotional intelligence, and in running the company over the last four years has created a healthy group dynamic to debate the unit’s strategy and ongoing decisions. The unit’s revenue and profits have grown.

Top team effectiveness programs should encourage executives to tell personal stories about key moments in their lives. This gives them insights on what drives their colleagues’ behavior, including their fears and motivations. One engineering company’s top team conducted an offsite at which its executives shared such life experiences (good and bad). They trusted one another far more and made much better decisions afterwards.

The executive team should set guidelines for how team members must communicate with each other, and define acceptable and unacceptable behaviors.

CEOs should actively encourage all team members to speak up without fear of consequences. That fosters honesty, debate and better decisions.

The CEO should let his team meet without him occasionally, so that his fears and influences don’t constantly shape the others’ behavior and decisions.

Incentive systems should discourage self-interested behavior.

Fears and dysfunctional behaviors will always influence human beings, from the playground to the boardroom. Other factors – such as deadlines, competitors and economic downturns – will also create pressures on a company’s top team. But executives and chief human resources officers need to look at the deep-seated private fears that may be eroding the executive team’s dynamics and company performance.

[image error]

February 23, 2015

What Millennials Want from Work, Charted Across the World

Courtesy of NASA GSFC

As more Millennials assume leadership positions around the world, organizations are becoming increasingly concerned with how to ensure their success. However, most existing research on those born between the early ‘80s and late ‘90s is skewed toward understanding what a narrow, typically Western, population wants. Conclusions based on such a limited sample could lead to bad decisions (and missed opportunities) around attracting, retaining, and developing millennial leaders in a global business environment.

To broaden our understanding of what Millennials want at work, INSEAD’s Emerging Markets Institute, Universum, and the HEAD Foundation conducted the first of what will become an annual survey of Millennials — and the largest study of its kind. We surveyed 16,637 people between 18 and 30 years old, in 43 countries across Asia, Africa, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, and North America. The data was collected from May to August 2014, and the results are presented in “Millennials: Understanding a Misunderstood Generation.”

While the data have limitations (for example, random sampling could not be used and some regions/countries had more responses than others), the size of the sample and its global reach allowed for clear patterns to emerge. When asked about the desire to become leaders, the importance of work-life balance, and the expectations around retirement, we found that some common assumptions rang true, while others did not. But perhaps most importantly, we found that almost all views varied considerably by culture.

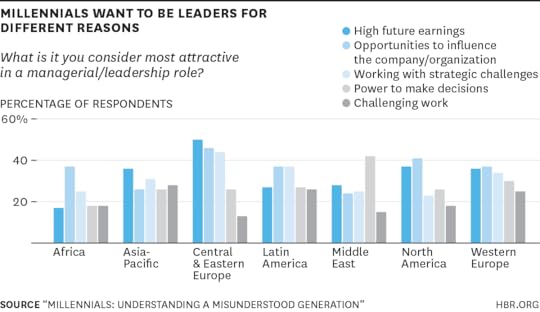

Millennials are interested in becoming leaders — for different reasons. On average, 40% of respondents claimed that becoming a manager/leader was “very important.” This ranged from 8% in Japan to 63% in India. And the reasons (money, opportunities to coach, building career foundations, etc.) also varied across cultures.

High future earnings stood out as the most dominant theme globally, yet the range was quite wide. Half of respondents from Central/Eastern Europe chose high future earnings as a reason to pursue leadership, while only 17% of Africans did. African Millennials seemed to care most about gaining opportunities to coach and mentor others (46%), a response that didn’t resonate as much in other regions — less than a quarter chose it in Asia-Pacific (APAC) countries, Central/Eastern Europe, and the Middle East. We also found that the opportunity to influence an organization was chosen by nearly half of those in Central/Eastern Europe and North America, but by only about a quarter of those in APAC countries and the Middle East. Companies should consider these findings when structuring incentives and leadership development programs.

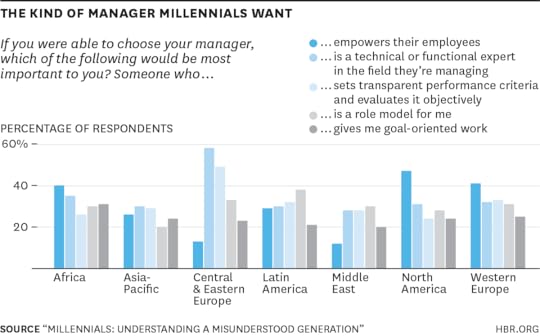

What Millennials wanted to see in a leader varied even more. For example, in North America, Western Europe, and Africa, at least 40% of respondents said they wanted managers who “empower their employees.” Yet only about 12% of Millennials in Central/Eastern Europe and the Middle East chose that quality. We can only speculate about the reasons, but the diverging preferences may be associated with a lingering imprint of the autocratic governance structures that were very much the norm in Central/Eastern Europe until not long ago, and are still in place in many parts of the Middle East.

Instead, 58% of respondents from Central/Eastern Europe believed that technical or functional expertise in a manager was important (in other regions, only a third or fewer respondents agreed). In the APAC countries and the Middle East, however, no single response drew more than one third of respondents.

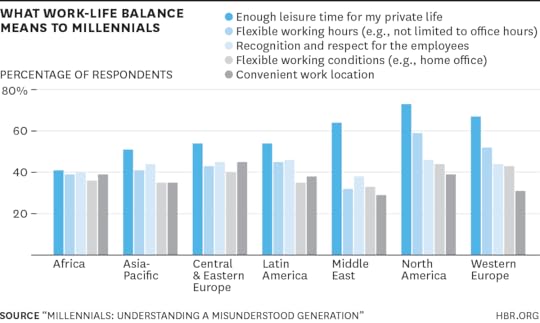

Work-life balance doesn’t mean the same thing to all. Millennials strive for work-life balance, but this tends to mean work-me balance, not work-family balance. They want time for themselves and space for their own self-expression. Overall, the dominant definition was “enough leisure time for my private life” (57%), followed by “flexible work hours” (45%) and “recognition and respect for employees” (45%).

Which responses or regions were outliers? In both Central/Eastern and Western Europe, “overtime compensation” scored relatively highly (52% and 45% respectively), indicating greater interest in regulated labor issues. In North America, 59% chose “flexible work hours,” perhaps indicating a stronger preference for autonomy. On the other hand, North American millennials do not seem averse to working long hours if it speeds up career progress — 42% found this proposition interesting. It was the same in Latin America, and it was 51% in Africa. However, nearly half of respondents in every region said they would give up a well-paid and prestigious job to gain better work-life balance. Central/Eastern Europe was the exception, as 42% said they would not.

Most Asian millennials defined work-life balance as having enough time set aside for their private lives, but this average hides differing country-by-country attitudes. In Singapore, 76% defined work-life balance as having leisure time to spend privately, while in Thailand, only 29% did. In India, 42% defined it as “flexible working conditions,” while in Vietnam, 76% saw it as “offering external activities (e.g. sports, cultural events).” Many Asian Millennials also seem to stress the importance of social ties more than their Western counterparts. For example, they rely more on support from friends and family.

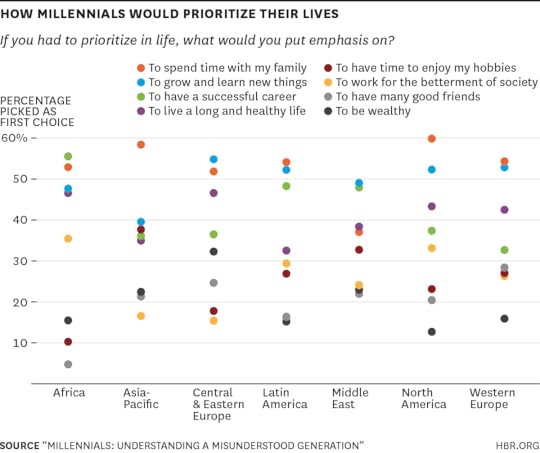

That said, some attitudes were similar across the world. For example, spending time with family ranked among the highest of priorities in every region we surveyed. And perhaps surprisingly, we found that working for the betterment of society was not a priority for a majority of Millennials anywhere.

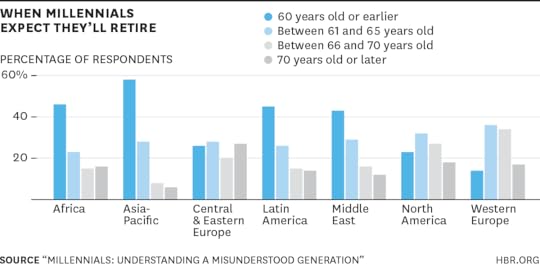

The “fear of not being able to retire” isn’t as widespread as it’s made out to be. The data show that this notion, often written about in the West, is not generally supported. Notably, in the Asia-Pacific, 58% of Millennials expected to retire by age 60 (in China, it was higher). And Central/Eastern European Millennials predicted the oldest retirement ages, with more than 27% expecting to retire at or after the age of 70.

We must be careful not to imply more than the data tells us. For example, it would not be fair to assume Millennials in regions with higher than average expected retirement ages (Europe and North America) are less confident about their financial future. Those findings could simply show a higher degree of confidence about future health. What we probably can assume is that Millennials in regions with lower projected retirement ages (APAC) feel more confident about their financial ability to do so. We also found that Millennials in Central/Eastern Europe, Africa, Asia, and Latin America most widely believed that they’d enjoy a higher living standard than their parents.

Generally, Asian Millennials are positive about their prospects for a secure financial future – with the possible exception of Australia. This outlook seems to correlate with the economic growth the region has experienced in their lifetimes. But while they do not necessarily fear retirement, they do they fear getting stuck in a job that they do not like and that is not challenging.

When we asked about work-related fears, we found that the top three were getting stuck with no development opportunities, not being able to realize their career goals, and not finding a job that matches their personality. Certain regions had “outlier fears,” or responses that were significantly different from those in other parts of the world. For example, in Africa, more Millennials (22%) worried that they wouldn’t get the chances they deserved because of their ethnic background. This differed from the average across other regions (12% in North America, 2% in Latin America, and 1% in Central/Eastern Europe). These regions noted other big fears. In North America, it was: “I will work too much.” While in Latin America, it was: “I will underperform;” and in Central/Eastern Europe, it was: “I won’t be valuable to the organization.”

To attract, retain, and develop Millennial leaders, companies and managers need to take these regional differences into consideration. What matters to a Brazilian Millennial might differ from what matters to a Singaporean Millennial, which differs from what matters to an American Millennial. But while it’s important to understand what’s valued in a particular culture, it’s also necessary to remember that people vary greatly within cultures. If there is one thing we know about Millennials globally, it is that they want to be seen as individuals.

[image error]

Inside Adobe’s Innovation Kit

Need to unleash innovation in your company? Trying raising an army of Kickboxers.

No, it’s not quite what you think.

Adobe Systems has recently launched a program to drive innovation from within, the Adobe Kickbox. The Kickbox is a small, red cardboard box containing everything an employee needs to generate, prototype, and test a new idea. According to Adobe, the Kickbox is “designed to increase innovator effectiveness, accelerate innovation velocity, and measurably improve innovation outcomes.”

The top of the box features a clever fire alarm image with the words “Pull in Case of Idea” written on it. When you break open the seal, you’ll find instruction cards, a pen, two Post-It note pads, two notebooks, a Starbucks gift card, a bar of chocolate and (mostly importantly) a $1,000 prepaid credit card. The card can be used on anything the employee would like or need without ever having to justify it or fill out an expense report.

The instructions inside the Kickbox take the form of a six-level curriculum that encourages employees to beat each level and “beat the box.” Each level contains exercises and a checklist. The exercises are designed to guide employees from ideation stages to a small-scale test of at least 100 users (the fifth level). The sixth level’s exercise is selling the idea to management. Putting selling to management as the final level is intended to democratize the process of getting new ideas – like many organizations, Adobe feared that its most creative ideas weren’t ever getting tested because they had to be sold to management first, to even be given a budget for prototyping.

As I write about in my book, The Myths of Creativity, many organizations unknowingly stifle innovation by requiring ideas to move up through levels of management before getting any investment. This might control costs, but as research led by Wharton’s Jennifer Mueller suggests, many people have a subtle bias against innovative ideas. Mueller’s team found that people often claim to want new and creative ideas, but when presented with those ideas in an uncertain environment and asked to evaluate them, the more novel ideas often get a lesser rating. Further research also showed that managers and senior leaders especially tend to reject the very ideas customers want. In the follow-up study, Mueller’s team found that when both managers and customers rated the desirability of new product ideas, customers favored the most creative ideas while managers most often rated those ideas as less than desirable because they saw them as unfeasible or not profitable. Both studies shine light on the friction many employees feel when trying to get their ideas implemented.

The idea for Kickbox came when Mark Randall, Vice-President of Creativity for Adobe found that same friction. In an article in Fast Company, Randall explained how he was looking for a way to capture the energy from Silicon Valley-style hackathons into something more tangible and more scaleable. Randall has surveyed employees to figure out what led them to keep their ideas to themselves and found that “convincing management” was the most frequent response. That led Randall to realize there was a better way to spend an innovation budget. Instead of funding the few big ideas getting presented, he could chop up his budget and potentially find the big ideas that often go unpresented. The Kickbox is a way to place thousands of little bets (as Peter Sims calls them). Any employee can request a Kickbox – and managers are prevented from vetoing the request. While employees have to share their results, there is no deadline on when they have to present and no judgment if their Kickbox bet doesn’t pay off. Adobe has even designed a two-day optional instruction course on how to get the most out of their Kickbox experiment.

More than 1,000 Kickboxes have been distributed to employees so far. It’s still too soon to assess the hard numbers results of the Kickbox program, as only a handful of employees have completed the last level and “beat the box.” Out of that handful, Adobe is seeing some promising ideas, one of which led the company to eventually acquire stock photography company Fotolia. However, on the soft side, Adobe claims the program has helped better engage creative employees and attract innovators to join the company. They’ve also made the Kickbox instructions available on their website, so any company can create a kickbox or modify the instructions to make their own.

The brilliance of the Kickbox isn’t that it gives employees a magic box, it’s that it gives them permission. And often, that’s all that required to unbox creativity.

[image error]

How the Best Board Directors Stay Involved

“Ask me for anything,” Napoleon Bonaparte once remarked, “but time.” Board members today don’t have that luxury either. Directors remain under pressure from activist investors and other constituents, regulation is becoming more demanding, and businesses are growing more complex. McKinsey research suggests that the most effective directors are meeting these challenges by spending twice as many days a year on board activities as other directors do.

As directors and management teams adapt, they’re bumping into limits—both on the amount of time directors can be asked to spend before the role is no longer attractive and on the scope of the activities they can undertake before creating organizational noise or concerns among top executives about micromanagement. We recently discussed some of these tensions with board members and executives at Prium, a New York-based forum for CEOs (in which McKinsey participates). The ideas that emerged, while far from definitive, provide constructive lessons for boardrooms. If there’s one overriding theme, it’s that boosting effectiveness isn’t just about spending more time; it’s also about changing the nature of the engagement between directors and the executive teams they work with.

Engaging between meetings. Maggie Wilderotter, chairman and CEO of Frontier Communications (and a member of the boards of P&G and Xerox) stresses that “it’s not just about the meetings. It’s about being able to touch base in between meetings and staying current.” Such impromptu discussions strengthen a board’s hand on the company’s pulse. Keeping board members informed also minimizes the time spent on background that slows up regular board meetings. And the communication works both ways. “I also want board members to elevate issues that they’re seeing on the horizon that we should be thinking about,” explains Wilderotter. “To me, it’s really more of a two-way street.” Directors and executive teams will need to work out what rhythm and frequency are right for them. Denise Ramos, president and CEO of ITT, notes that “conversations with board members every week or every two weeks may be too much.” For boards seeking to boost their level of engagement between meetings, experimentation and course correction when things get out of balance are likely to be necessary.

Engaging with strategy as it’s forming. Strategy, especially on the corporate-wide (as opposed to BU) level, is an area where the diverse experiences and pattern-recognition skills of experienced directors enable them to add significant value. But that’s only possible if they’re participating early in the formation of strategy and stress-testing it along the way, as opposed to reviewing a strategy that’s been fully thought through by executives. In the description of Wilderotter, strategy needs to become “a collaborative process where different opinions can be put on the table” and “different options can be reviewed and discarded.” This shifts the board’s attitude from reactive to proactive and can infuse a degree of radicalism into the boardroom. Effective directors don’t shy away from bold strategic questions, such as “What businesses should this company own?” and “What businesses should this company not own?” We were impressed by one board that even dared ask, “Should this company continue to exist?” In fact, that board concluded that the company should not continue to exist, and effected a highly successful reorganization separating the firm into several freestanding enterprises.

Engaging on talent. Directors have long assumed responsibility for selecting and replacing CEOs, both in the normal course of business and in “hit by a bus” scenarios. Many also find it useful to track succession and promotion—for example, by holding annual reviews of a company’s top 30 to 50 key executives. But to raise the bar, some boards are moving from simply observing talent to actively cultivating it. Case in point: directors who tap their networks to source new hires. Donald Gogel, the chairman and CEO of Clayton, Dubilier & Rice, explains that “our board members can operate like a highly effective search firm. There’s nothing like recruiting an executive who worked for you for a long time, particularly in some functional areas where you know that he or she is both capable and a great fit.” Other boards actively mentor high-performing executives, which allows those executives to draw upon the directors’ experience and enables the board to evaluate in-house successors more fully.

Engaging the field. Another way to enhance board engagement is to assign directors specific operational areas to engage on. Board members can assume roles in specific company initiatives, such as cybersecurity, clean technologies, or risk— becoming not only “the board’s eyes and ears,” notes Eduardo Mestre, Senior Advisor for Evercore Partners and a board director of Comcast and Avis Budget, “but really being a very active participant in the process.” Jack Krol, chairman of Delphi Automotive and former chairman and CEO of DuPont, requires board members to visit at least one business site every 12 months. At the same time, directors should be mindful not to interfere with operational teams or to supplant managers. The goal is to target specific projects that are particularly appropriate for individual directors and to encourage participating board members to be, as one director says, “collaborative, not intrusive.”

Engaging on the tough questions. We noted above the value of probing difficult strategic issues, but the importance of asking uncomfortable questions extends beyond strategy sessions to a wide range of issues. “You should have some directors—perhaps 20% of the board—who know the industry and can challenge any operating executive in that company on industry content,” says Dennis Carey, a Korn Ferry vice chairman who has served on several boards. “But the problem is not too few people on boards who know their industries. The problem is too many people who know the industries, who are looking in the rearview mirror and assuming that what made money over the past 20 years will make money again.” Michael Campbell, a former chairman, CEO, and president of Arch Chemicals, builds on this theme by adding that “every board member does not necessarily need to have industry experience. But they must have the courage in the boardroom to ask difficult questions.”

Our McKinsey colleagues have noted in past articles that understanding how a company creates (and destroys) value makes it much easier to identify critical issues promptly. In fact, it is worth asking whether everyone in the boardroom does indeed understand how the company and each of its divisions make money. Gogel even suggested that “boards should have at least one person who has the responsibility to think like an activist investor. Many boards are caught unaware because no director is playing that role.”

As boards raise and grapple with uncomfortable questions, it’s important to connect the dots between issues—perhaps by tasking one director with serving in an “integrator” role. “We get into a boardroom,” Wilderotter remarked, “and everybody’s a peer. But having a specific capacity to bring disparate points together is critical to keeping a board functional versus having it be dysfunctional.”

Ultimately, there are no shortcuts to building and maintaining well-tuned board and executive mechanics. Each of the measures requires hard work from the board members, and sometimes a CEO with thick skin. But a good director will provide the extra effort, and an effective CEO will make the most of an engaged board’s limited time.

[image error]

Start-Up Capital Is Spreading Across the U.S.

Startups have seemingly never been more popular, particularly in the U.S. Perhaps there’s something in the American spirit that appeals to striking out on your own, or perhaps it’s that Internet connectivity and cloud computing have theoretically made it possible to create and grow scalable businesses from most anywhere. Investors like Steve Case and Brad Feld are betting on companies outside Silicon Valley, predicting that “the rise of the rest” will geographically level the entrepreneurial playing field and make startup communities more prevalent throughout the country.

But what do the numbers say? Are startup hubs really forming all over the U.S.? To begin to answer this question, I analyzed data on a small subset of early-stage entrepreneurial ventures that are focused on high-growth — those receiving venture capital funding. I aggregated venture capital deals for each U.S. metropolitan area — 381 in this case — annually between 2009 and 2014, looking only at “first fundings,” or initial rounds of professional venture investment (those most closely associated with starting-up).

This analysis demonstrates that while a handful of well-known cities continue to dominate the landscape of early-stage venture-backed entrepreneurship, a non-trivial amount of catch-up by other cities has occurred.

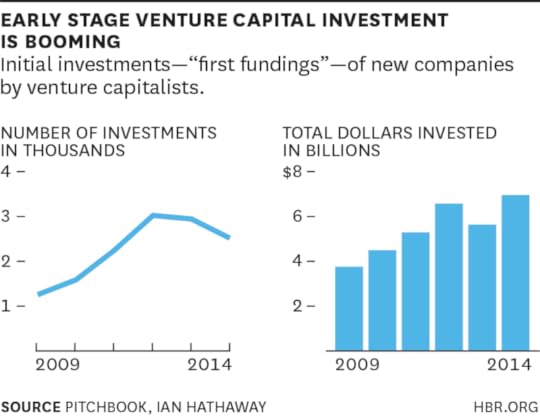

The chart below shows the number of first funding rounds by venture capitalists, and the total dollars invested. It confirms the fairly well known fact that early-stage venture capital deals are booming — the number of first fundings increased 150% between 2009 and 2012, before plateauing in 2013 and reverting some by 2014.

Nominal dollars invested increased less quickly than did the number of deals, as companies required smaller investments to get off the ground. The average deal size trended down each year from 2009, until shooting back up again in 2014.

So, more companies are receiving initial funding from venture capitalists, but back to the question at hand: how is this boom distributed geographically?

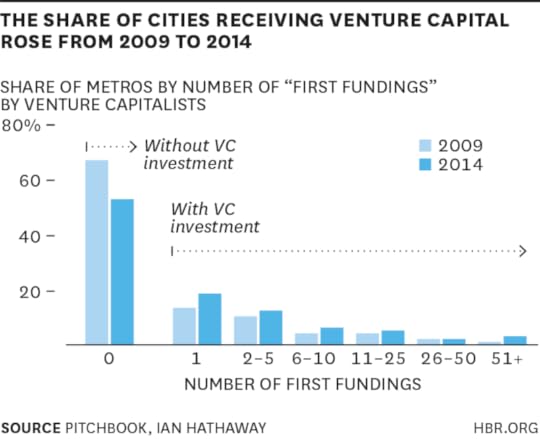

The next chart shows the share of U.S. metropolitan areas by the number of first fundings received annually in 2009 versus in 2014. The data show a sharp increase in the share of cities that receive at least some first-round venture capital. Two-thirds of the metro areas received no first-round venture deals in 2009. Five years later, that figure fell to slightly more than half.

Furthermore, the share of metropolitan areas receiving first fundings increased for each of the deal count categories. Not only are a substantial number of metros going from zero early-stage deals to one deal, but a fair number are expanding from one deal to a few, and from a few to many.

Despite this progress, venture capital remains highly concentrated in a handful of metropolitan areas, and early stage deals are no exception. Even in 2014, the vast majority of cities – 83% – received five or fewer initial VC fundings. Because of that, a closer look at the very top of the distribution is necessary.

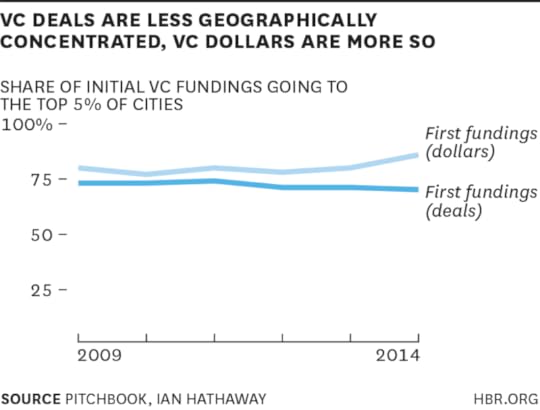

The chart below plots the share of first funding deals and dollars that go to the top 5% of metropolitan areas for such venture deals. It is clear that there is a tremendous amount of venture capital activity in just a small number of cities. About seven of every ten early-stage deals, and more than five of every six first-round dollars is goes to the top 5% of cities.

There is also some divergence between the share of first funding deals and dollars over this five-year period. Though subtle, there is a clear decrease in first-round deals going to the top 5% of metros over time, while simultaneously there is an increase in the share of investment dollars going to the very top of the distribution — particularly in the last two years.

This suggests that early-stage deals are larger in the leading venture capital cities, and raises the question: why are average deal sizes in the major venture capital cities getting so much larger since 2012? I don’t have the answer, but it does warrant further exploration.

To recap, the data tell a pretty clear story that seems to confirm the “growth-focused startups are spreading throughout the country geographically” narrative — venture capital first fundings are reaching more regions throughout the United States, and those that previously received at least some venture capital appear to be getting more early-stage companies funded.

While the substantial majority of first funding venture capital continues to go to a small number of metropolitan areas — even truer when measured by the amount of capital invested — the bottom of the pyramid is broadening and a number of cities are getting in on the action.

These cities will not rival Silicon Valley or even New York or Boston any time soon. Still, this is a welcomed development in my view. The presence of businesses in a region that achieve very high growth can broadly boost income and employment opportunities, not just for those directly involved, but for all participants in the local economy.

[image error]

Keep Your Home Life Sane when Work Gets Crazy

When you’re going through a phase that compels you to put in more time, effort, brainpower, and heart into your job, how do you work it out with your family and others who matter in your life? And how do you make sure this spike in your focus on work doesn’t become a “new normal” that extends indefinitely into the future? The short answer: Dialogue about what matters most – to you and to them.

First, forget balance, which is a misguided metaphor for what success looks like in the different parts of life. It’s not possible to have perfect equilibrium among the four domains of life – work, home, community, and self – every day, every week, or even every year. Naturally, there are times when any one of these aspects of your life has to take center stage.

When a spike in work-related activities is having a deleterious effect on your family or on some other part of your life, then it’s time for what I call “stakeholder dialogues” – conversations with the people who matter most about your mutual expectations and how best to meet them, now and in the long run.

Here are five steps to take in such conversations:

Provide context by letting people at home (or in your community) know why your work temporarily demands your attention to an extraordinary degree. As in “Let me give you a bit of background about what’s happening…” Keep it short. This is not an excuse; just a brief explanation to set the stage for dialogue.

Explain the purpose of what you’re doing at work and why you believe it’s important, not solely for your own growth but for the positive impact you hope to have on others. As in, “By my devoting this effort now I’ll be able to ____, which is important to us because it’ll help us to ____.”

Ask about the consequences they believe will result from this shift in your attention toward work. Learn more about what this adjustment means for them. As in, “Can you tell me how this will make things harder for you?” and then follow up with “Can you give me an example?” Do not try to minimize the difficulties they report; instead, compassionately inquire.

Express genuine remorse for disappointments or hurt you might be causing, being specific about your understanding of how your actions are creating stresses and strains. As in “I’m sorry that my being unavailable is hurting you.” Own it.

Explore possible alternatives for how you might minimize these negative effects. As in “I’m not sure what might help, but do you have ideas for what I can do to try to make this better for us, our family, our relationship?” And ask again, as in “What other thoughts do you have about what I can do, either now or sometime in the future?”

You’re likely to discover possibilities for actions you can take that won’t cost you much, but will help to minimize any damage caused by your work spike. You might even improve the quality of your relationships with your family, friends, and others in your life.

Assuming that if you’re not home for dinner that your family is losing out, or that you’re losing out, may not be an accurate read. Maybe driving your daughter to school is more important to her than your being home for dinner. Your spouse might be happy to meet you in town for dinner, even if you have to return to the office while he or she heads home afterward. Maybe they don’t care so much if your travel increases or the length of your workday increases, as long as they have your undivided attention when you are at home. You won’t know until you ask.

What I’ve found is that what others expect of you is usually a bit less than, and somewhat different from, what you think they expect of you. And unless you know what’s essential and meaningful to them, now and in the future, you can’t generate creative solutions that make sense to you and to them.

Once you’ve navigated your way through an especially tumultuous episode at work and managed to keep your domestic ship of state on course, it’s useful to again be deliberate in choosing a path forward that suits all parties. You might want to mark the end of that period as a special occasion with a celebratory dinner, as a way of closing the book on it.

Then, keep your stakeholder dialogues going as you return to a normal workload. Take a bit of time to review which of the strategies you employed worked well and which did not. The key is remaining open to discovering new ways of adjusting – either at work or at home—that let you pursue what you care about most, no matter what the world throws at you.

[image error]

You Can Teach Someone to Be More Creative

Photo by Andrew Nguyen

Though our inspiration levels fluctuate from time to time, we all differ in our baseline levels of creativity. For instance, it is safe to assume that John Coltrane was more creative than Justin Bieber, and that the creative talent of Leonardo Da Vinci exceeded that of George W. Bush. In the world of business, few entrepreneurs can realistically expect to emulate the colossi of innovation, such as Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, or Richard Branson, or the companies they created.

But can you coach someone to be more creative?

To some degree, our creativity levels are hard to change. They come down to personality traits such as intellectual curiosity, openness to experience, and unconventionality, which are largely set by the time we reach early adulthood. Creative individuals have also been found to have higher IQs and lower latent inhibition – that is, an “inability” to suppress irrelevant or inappropriate thoughts, which provide the raw materials for their creative ideas. And, as recent research highlights, the key ingredients for creative performance are somewhat field-dependent: in the arts, IQ is irrelevant but the desire to seek beauty, a tendency toward fantasy, and a vivid imagination are all critical; in science, thinking, reasoning, and a drive for truth are essential, even more so than IQ; in business, EQ and extraversion help, not least because innovation depends on successfully selling your creative ideas to others.

So creativity is not 100% malleable – personality sets its limits – yet it can still be nurtured via deliberate interventions, especially over a long period of time. Genetic studies suggest that genes determine only 10% of the variability in creative potential, so there is a lot of room for development.

Here are the main factors to consider when attempting to coach creativity:

You and Your Team

Coaching

Get better at helping your employees stretch and grow.

1) Give lots of feedback: Given that most people are not as creative as they think, it is important that any attempts to coach creativity begin by providing individuals with feedback, especially when they are narcissistic, since narcissism inflates people’s estimates of their own competence to an unrealistic level. Feedback is essential to help people close the gap between their confidence and their competence. Employees who seek more feedback have been shown to perform more creatively than their counterparts. Conversely, individuals who ignore feedback from others will only end up being creative in their own minds.

2) Provide training in creative thinking. Several exercises have been found to enhance creative performance. For example, teaching people to detect novel ideas, take on challenging tasks, retrieve knowledge outside their main area of expertise, or combine unrelated things or ideas can all boost creativity. The reason why incubators are so effective is that they successfully combine many of these techniques (e.g., they disengage people from their everyday activities and force them to pay attention to other issues, they push people to see things from different perspectives, and so on). Even small changes in your everyday routine can have a positive impact on your creative output – for instance, taking a different route to work everyday, or taking on new hobbies and activities.

Meditation and relaxation have also been found to improve creative performance, partly by creating more favorable mood states. A review of nearly 600 studies found that mediation, including mindfulness, enhances creativity with the same effectiveness as psychotherapy interventions improve well-being, and not merely by improving relaxation and mood. Managers can boost employee creativity by fostering meditation and relaxation not only in their employees, but also in themselves – the more relaxed and mindful managers are, the more they will value and reward creative ideas in others.

3) Assign people to tasks they love. One of the most effective methods for enhancing creative performance is to increase individuals’ motivation, particularly intrinsic motivation (their task-related enjoyment, interest, and involvement). Ever since Teresa Amabile first emphasized this idea, meta-analytic studies have confirmed the intuitive idea that assigning people to projects they love unleashes their creative potential. In contrast, extrinsic rewards, such as financial incentives, tend to inhibit people’s creativity. In the words of Carl Jung, “The creative mind plays with the object it loves.”

4) Help employees develop expertise. For any subject matter, creative performance is a function not just of potential, thinking skills, and motivation, but also of expertise. Most people are inclined to believe that knowledge interferes with creativity — that the more you read and find out, the harder it is to be creative. On the one hand, it is virtually impossible to come up with ideas that are completely original, which is why Einstein said that “the secret to creativity is knowing how to hide your sources.” On the other hand, without expertise or task-relevant skills, you cannot produce anything creative. If you don’t know how to play the piano, you’ll never be able to improvise on it; if you don’t speak a language, you won’t be able to tell jokes; and if you can’t code, you won’t be able to develop an original app. Therefore, a higher level of expertise, particularly in an area your employee is passionate about, will increase their chances of being creative in that domain.

Of course, expertise is not sufficient for creative performance. It is not enough to master the elements of the system — one also has to rearrange them in original ways. As Picasso once said, “Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

Finally, let’s not forget that though individual creativity matters, team creativity is far more important. The Western notion of “creatives” as individual superstars is in stark contrast with the realities of real-world innovation. Creativity is mostly a team effort that can only result from coordinated group activities, because it requires individuals to leave aside their selfish agendas to work as a team — and that is why leadership is a key driver of creativity.

Here are three basic suggestions managers can follow in order to boost the creative output of their teams:

Balance differences and similarities: high-performing teams tend to be similar in their values (they are all motivated and driven by the same things) but different in their styles (they have different personalities, skills, and backgrounds).

Avoid having too many “creatives”: although idea generators are critical to any creative team, their ideas will only be implemented if the team also comprises people who love execution, think pragmatically, pay attention to details, and help to transform their creative ideas into actual innovations. Don’t assume that your less creative employees cannot make a key contribution to the group’s overall creative output.

Embrace failure: This has become a cliché, but it is true. Too many managers and companies pretend to embrace creativity but they don’t care enough to do what it takes to promote it. They want employees to achieve “less with more” and are happy to support their creative ideas so long as they will “work for sure.” If you are not prepared to embrace failure, you will never encourage your employees to do anything creative.

[image error]

February 20, 2015

Why Debunking Myths About Vaccines Hasn’t Convinced Dubious Parents

Seventeen years ago, a physician in the UK published a study of twelve children who had been given the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine. It implied a scary correlation between the vaccine and autism. But upon both further investigation and further clinical studies, the original finding was thrown out, the medical journal retracted the article, and the doctor was found to have unethical financial interests in the findings. Finally, he was stripped of his license to practice medicine.

Yet today, surveys show that as many as a third of U.S. parents still believe the discredited allegations. One in five milliennials believe early childhood vaccines cause autism and 26% of parents trust a celebrity as a credible source on vaccine safety. And measles, declared officially eradicated in the U.S. in the year 2000, is back.

This has all led to a contentious debate among parents, politicians, and the medical community. But as someone who does communications for a living, I have a professional interest in this as well. Why it is so difficult to dispel rumors and debunk myths? I see four major reasons.

1. Arguing the facts doesn’t help – in fact, it makes the situation worse. In 1979, Charles Lord performed a seminal piece of research that revealed when you show someone factual, scientific evidence that they are wrong, they react badly. They will only accept the evidence that fits their pre-existing views. Lord called this effect “confirmation bias.” There have been hundreds of studies since, all finding the same results: when you argue using facts and evidence, people generally reject or discount your evidence. Instead of changing their minds, most will dig in their heels and cling even more firmly to their originally held views. Brendan Nyhan of Dartmouth and Jason Reifler of the University of Exeter have also documented an even more alarming tendency, which they call “the backfire effect.” In their study, correcting people actually increased their misperceptions.

2. Repeating the myth inadvertently popularizes it. When you repeat the myth while trying to debunk it, you do two things: first you introduce the myth to people who may never have heard it. As many as 40% then believe it. Second, by repeating the myth, you unintentionally convert “false claims into recommendations” as one study shows. They found that after three days, older adults misremembered 28% of false statements as being true, but once the false statements were repeated three times, the number of people who confused them as being true jumped to 40%. So repeating wrong information, even to debunk it, backfires.

3. Affirmation works – but we rarely use it. When someone has their facts wrong, our impulse is generally not to tell them we think they’re great. We’re more likely to go on the attack.

But Nyhan and Reifler, in their research on misperceptions and corrections, discovered that when people who are mistaken undergo a self-affirmation exercise, it increases the odds that they’ll accept the corrected information. That means you may have more success changing minds after making your audience feel good about themselves.

Part of the polarization happening in the vaccine debate stems from the vilifying of those parents who have not vaccinated their children. Instead of going on the attack, pro-vaccine advocates should reassure parents that we know they love their children. Treating them as idiots or fringe lunatics will only worsen the discussion about the science.

4. We consistently underestimate the power of narrative. In the 1940s, Austrian psychologist Fritz Heider created what has become a legendary piece of research that reveals the need for people to craft narratives. Heider created a short, simple animation of two triangles, a rectangle and a circle. His subjects all (except one) read a complete drama into the animation, complete with love affairs and bullying. Humans, it seems, must have a story line, and in a void, will create one.

In the vaccine wars, the anti-vaccination movement has referenced many narratives. Each narrative is different, but each one features a protagonist and a villain, along with attempts to bury or distort the “facts.”

Model, actress, and celebrity activist Jenny McCarthy has been one of the most outspoken critics of vaccinations in the U.S. She has drawn upon a personal narrative of her son, whom she claims was rendered autistic by a vaccination but later cured through organic and holistic approaches. McCarthy leverages a very powerful technique known to social scientists as the “identifiable victim effect.”

It turns out human empathy does not scale well. We can care very deeply about one, single stranger, but that empathy wanes rapidly as the group of victims grows. Once it becomes a large number we cease caring. By repeating her emotional story, McCarthy draws upon this psycho-sociological phenomenon. And when put head-to-head with scientists talking about immunology, the story of her child will sway audiences every time. When challenged on her lack of scientific proof, McCarthy has retorted, “Evan is my science.”

Stephan Lewandowsky a professor who researches the debunking of myths wrote “The Debunking Myth Handbook.” In it, he points out that it is not good enough to knock down a myth and leave a narrative vacuum. You must create a credible alternative narrative.

Think of all the times you’ve tried to clarify something by saying, “It’s X, not Y.” Or of all the times you’ve resorted to the facts to win an argument. Or of how tempting it is to tease or belittle someone you know is in the wrong.

We all fall into these traps. But all you’re doing is reinforcing the information you don’t want people to hear, increasing their resistance to your message, and making it harder for them to hear you in the first place.

Instead, we need to dispel rumors and debunk myths without repeating the misinformation; rely on a compelling, proactive narrative; and realize that more information is not necessarily better.

[image error]

When to Bring in a Professional Coach

As a manager, you’ll inevitably need to spend time actively coaching employees. Perhaps you have a hard-working employee who needs to build certain skills to be more effective on the job. Or maybe you’ve recently promoted a high performer, and you want to ensure that you’ve made the right decision by giving her an opportunity to build new skills. In situations like this, you may find that you’re able to be a very effective coach for your direct report. But in the 15 years I’ve spent on coaching and employee development initiatives, I’ve found that there are certain scenarios when it simply makes sense to call in a professional:

When you have a close personal relationship. If you’re willing to coach your employee, you no doubt respect his talents and strengths. You might also really just like this person, and genuinely want to help him succeed. Perhaps you even spend time with this person outside the office, know his family, and attend functions or events together. When you have such a close personal relationship, it can be difficult to address areas that need improvement. If you’re having trouble drawing the line between the personal relationship and the business relationship, it’s wise to invest in a professional coach.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Coaching

Managing People Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

When an employee laughs off your feedback. Every organization has that employee whom we’ll call “the mayor.” This person is popular, and has good relationships with co-workers, senior management, and clients alike. However, when it’s time to do his annual review and talk about performance issues; he tends to brush it off, and wants to talk about the Jets’ defensive line instead. While he may be your top sales guy, he’s recently rubbed one of your conservative clients the wrong way with his jokes, and you’ve decided that it would be wise to call in a coach.

To keep this type of employee focused, don’t meet in your office. Book a conference room instead, and be direct with your employee as soon as he walks in. Let him know that the firm values his contributions, but would like him to work on certain issues with a professional coach. Be sure to outline the consequences of not taking the coaching feedback seriously.

When an employee isn’t interested in being coached. There are times when an employee won’t agree with your assessment that she needs a coach. She might try to dismiss the suggestion, saying “It’s not a big deal,” or “I don’t need a coach, I can fix this myself.” As a manager, you need to spend more time understanding why this person is so resistant to coaching. Consider that many employees are concerned about how it looks to have a coach, and fear that others might see their skills as inferior, weak, or in need of improvement. It’s your job as the manager to ensure that you frame the coaching in a positive light. Tell the person that the company is making a serious investment in his or her professional development — and that’s a good thing.

One caveat. If an employee has a bad attitude about being coached, constantly pushes back on the coach, doesn’t follow the coach’s advice, or constantly disagrees with what’s expected of him or her, you may need to revisit whether or not this person is actually coachable. Your organization is making a financial investment in the coaching, and it should be reserved for employees who are willing and able to be coached, and who have a positive mindset about receiving feedback and changing behavior.

When an employee is a star, and needs high-level coaching. Most star employees will need coaching for a single, specific issue. Maybe your biggest producer on the team treats his colleagues with sharp elbows, and therefore needs to work on his self-awareness. In a case like this, you want to keep the employee engaged and encouraged, while pointing out that the firm values not just results, but results that are achieved in a professional manner.Once you’ve made the decision to hire a coach, understand that it’s still important to remain actively involved in the process, and to hold all parties accountable for the change. Whatever goal you’ve laid out for your employee — to increase revenue, to obtain new clients, to change bad behavior — should be specific and measurable. To make any professional coaching session successful, you as a manager need to be sure to:

Pick a past situation or scenario and dissect it to determine what worked vs. what did not work. For example, you might want to review one of your recent client meetings and analyze the entire experience: What did the person do that helped to either obtain or lose new business?

Determine what results you need to see from the coaching, and set a deadline in the near future for when you need to see them. Using the example above, you might set specific goals for the next client meeting.

Ensure that the employee understands her “homework assignment” at the end of each coaching session. Using the same sales meeting example above, you might require that your employee learn how to bone up on client/industry knowledge before a client meeting. Make sure that she completes her homework assignment by demonstrating what she’s learned about a particular client, and how she’ll use that knowledge in the next sales meeting.

Set regularly scheduled meetings to check in on progress.

Finally, consider that the day-to-day demands of being a manager and leader don’t always give you the time you need to coach your employees. Instead of putting necessary coaching off, consider partnering with a professional. Your employees’ continued development is too important to relegate to the back burner.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers