Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1312

March 9, 2015

3 Improv Exercises That Can Change the Way Your Team Works

What can leaders learn from improv comedians?

For five decades, The Second City comedy theatre and school of improvisation has been a launch pad for the leading comic performers of our times, from Alan Arkin to John Belushi, Gilda Radner to Tina Fey, and Steve Carell to Stephen Colbert, and many more. In a reference to our talent development prowess, we’ve been called the Harvard of Comedy (which is great, except that we think Harvard is the Second City of higher education).

We’ve been quite intentional about creating training curricula to reliably fill our pipeline, and as we’ve honed our methods, we’ve seen that improv principles are highly applicable to the corporate world. Drawing on lessons we’ve learned, my group, Second City Works, now counsels leaders during 400 engagements a year, about half with Fortune 1000 companies. Of all the lessons we share, these three are perhaps the most important:

Embrace the ensemble

There’s an important axiom in improvisation: Always take care of your partner. Even the most talented comedians need support when they’re up on that stage. The same is true of leaders: you need a great ensemble, working in concert around you, to succeed. We use the word “ensemble” because we think “team” is too loaded – often equated with lousy teambuilding experiences or associated with competition, where one group wins and another loses. Ensemble, by contrast, implies cooperation, collaboration, and unconditional support. For those who view success as a zero-sum game, believing that when you help others, you detract from your own success, we have dozens of counterexamples. Some of our most successful alums — including Fey, Colbert, Eugene Levy, Steve Carell – all achieved stardom while learning from and boosting their ensembles.

Exercise: Gather five to 10 people in a circle and create a new story one word at a time. Go around a dozen times, then stop to check in. Participants quickly learn that they have to balance their own ideas and expectations with those of the ensemble. No one can control the outcome. And words like “the” or “and” are just as important as “tortoise” or “hare.” Seemingly small contributions matter greatly to the whole.

Take responsible risk

In an improv theatre, failure is ever present; even Second City’s scenes don’t work a lot of the time. But our actors’ material works often enough that they’ve learned to accept little failures on the way to larger successes. Business leaders need to embrace risk in the same way. This can be difficult since most organizations reward prudence, planning, and the elimination of variables that can cause problems. But most decisions have to be made with imperfect information anyway. To navigate those grey zones, we advocate risk sharing – using your ensemble to help you solve vexing problems and support you when things go wrong.

Exercise: Two people engage in a conversation about anything, but have to begin every sentence with the words, “thank you.” This underscores a key idea in improv: everything your colleagues offer is a gift about which you should feel grateful. When comedians, or leaders, create an environment that welcomes and values contributions, people are willing to give bolder, more honest comments and take more risks.

Follow the follower

When our actors perform, it’s often impossible to know who is “leading” any given scene. Our people learn to do whatever is needed to entertain the audience. You may initiate an idea, then support someone else as he takes it in a different direction. The goal is to not be or even follow the leader, but to “follow the follower”. Effective leaders are equally comfortable ceding control to others, playing a more supportive role and filling gaps. Heck, I’m a CEO, but in our company, that doesn’t mean I’m always leading the conversation and my “rank” has little to do with the contribution I make.

Exercise: A group makes a circle; one person stands in the middle, eyes closed. Everyone else silently chooses one member of the circle to be the leader, then begins to mimic any body movements he or she makes. The person in the middle opens his or her eyes and tries to determine who the leader is. We use this exercise to reinforce the idea that high-functioning improv ensembles find their leaders by looking for the right person at the right time, not formal titles.

Improvisation – and the improv toolkit – offers great grounding for leaders challenged to thrive in a business climate that demands agility, resilience, quick thinking, and ease with ambiguity. Counterintuitive as it might seem, business is often an act of improvisation, not planning. So we say “lights up” on the era of leader as improviser.

[image error]

March 6, 2015

Learn to Become a Less Autocratic Manager

Mark, a ten-year veteran of the pharmaceutical R&D world with a Ph.D. in statistics, was the obvious choice to lead the SAS software and data management group of a global healthcare corporation when the current director suddenly departed. Having managed a small team of bio-statisticians successfully over three years, promoting him to director seemed like a no-brainer. Yet, within six months, despite being viewed as “high potential” by the C-suite, he had managed to alienate just about everyone.

As a team leader, he had proven himself effective—delivering results, improving processes, and directing junior staff. So why, when given the chance to manage a larger, more diverse group of top performers, would he flame out so spectacularly? The answer was simple: Mark was bossy.

By the time a coach was brought in, there was an alarming downward trajectory of morale and productivity. 360 feedback suggested that although Mark was respected for his expertise, his management style wasn’t working with this more experienced team. Some of his new team members matched his technical skills, and all of them were used to a great deal of autonomy.

As Mark painfully discovered, trying to run a seasoned, highly skilled group with the traditional type-A, command-and-control style is doomed to fail. Today’s knowledge workers demand what leadership experts call a “post-heroic leader”: one who is emotionally and intellectually agile, able to modulate their style as needed from authoritative to collaborative—and back again—in order to optimize team performance. Post-heroic leaders recognize that the key to success is not adhering to hierarchy or position power, but mastering a complex set of seemingly contradictory organizational dynamics—autonomy and shared decision-making, individuality and teamwork.

You and Your Team

Coaching

Get better at helping your employees stretch and grow.

Mark’s situation called for a change in mindset about what it means to be a good manager. To his credit, he was open to coaching. Yet coaxing him to become more easy-going or to let go of control was not enough. He was used to driving people hard for results. To help him, Mark’s coach re-focused the same deep desire to excel that had made him a great statistician on adjusting his style and provided a framework for change, suggesting several shifts that Mark must undertake:

From self-awareness to social awareness. This shift occurs when a manager realizes that effective leadership calls for more than just knowing one’s own strengths and weaknesses. Social awareness calls for a heightened sensitivity to how one’s behavior, in words and deeds, impacts others. To help build this awareness, Mark’s coach asked him questions like:

What is the impact of your management style on others?

How do you know what others are thinking or feeling?

From directive to inquisitive. When seeking to improve processes or engender creativity from an expert group, the manager needs to shift from a stance of declaration to one of curiosity. Questions that help managers make this shift include:

How much time do you spend listening rather than speaking?

How do you know if you are truly listening to your people?

From power over to power with. When a manager lauds authority over subordinates, A-players tend to shut down (and look for the exit), while B-players tend to acquiesce, hide out, and fail to grow. As a result, the potential of the entire team is lost. To facilitate this important shift, a coach might ask:

How do you stimulate the best thinking from your team?

What is the role of your subordinates in making decisions?

From teamwork to teaming. Traditional managers tend to rely on static definitions of who is “in” and who is “out,” fostering a culture of conformity and internal competitiveness. Adaptive managers evoke commitment through common values and aspirational goals, not structure. Good coaching questions include:

How do you create a sense of belonging when the boundaries of a team are porous?

How do you leverage diverse talents, skills, and perspectives, getting the best from everyone?

This framework gave Mark tangible guidelines to work with—not just generic admonishments to be more democratic. Coaching provided the space to acknowledge his fear of “losing his edge” and his hard-earned respect from the C-suite while exploring a different possibility: that he could have both—remaining directive when needed, but “flexing” to accommodate a variety of work styles.

Within a few weeks, he had made significant progress on two of the shifts—from power over to power with and from teamwork to teaming. The changes he made included:

Setting up a series of brainstorming sessions for process innovation, utilizing an outside facilitator so that he could participate as a team member—not as the boss.

Enlisting expert “thought partners” on his team to help make specific decisions that impacted work flow and initiatives.

Pairing senior staff with junior staff for mentoring and coaching.

Sending a personal note to each team member, asking them to share what activity, structure, or process would support them to do their best work.

Holding an offsite “values summit” to explore what his people cared about most—out of which they created their own internal values statement and a list of operating principles.

Initially, Mark’s team was skeptical about his sudden transformation, but with consistency and repetition, he earned their respect and morale improved dramatically. Encouraged by his coach to see himself not so much as “the boss” but as a role model, he began communicating with greater candor and vulnerability.

For any manager that finds herself across the table from a traditional heroic leader, like Mark—one who defaults to position power and authority—the challenge is to accelerate the shift to a more adaptive approach. Start by helping him re-connect to his aspiration to excel, not just as a functional expert but also as a leader. Then provide a framework for considering new options, a safe space for experimentation, and most important, ask thought-provoking, open-ended questions to spark his creativity. With the right kind of support, an old-fashioned manager can make the post-heroic leap, and soar.

[image error]

7 Traits of Companies on the Fast Track to International Growth

More than half of Google’s revenue (57%) now comes from outside the United States. Apple has a similar split, with 60% of its 2014 fourth-quarter revenue accounted for by international markets. Why is it that some companies experience tremendous success abroad, while others struggle to go global? In my work as a global business advisor to Fortune 500 companies and high-tech start-ups, I’ve observed seven traits that distinguish companies with accelerated global growth.

They have an innate global bias. American companies with strong performance in international markets frequently have a founder or a prominent executive on their team who is either from a foreign country or is a first-generation American. Having global diversity in the C-Suite makes a business more likely to optimize for global growth. Consider Google’s Sergey Brin (Russia), Facebook’s Eduardo Saverin (Brazil), and Microsoft’s Satya Nadella (India). Even Steve Jobs was the son of a Syrian immigrant.

A study published by the National Venture Capital Association reveals that 40% of publicly traded venture-backed companies operating in high-tech manufacturing were founded by immigrants. Similarly, more than 40% of the 2010 Fortune 500 companies were founded by foreign-born immigrants or first-generation Americans, according to a study by The Partnership for a New American Economy.

On the flip side, businesses lacking an international perspective among their leaders are often timid about moving into new markets. A fear of the unknown is normal, and because they do not have first-hand experience, they sometimes fail to recognize the importance of the rising middle class around the world. They struggle to prioritize global expansion, because they are not convinced they need to diversify geographically in order to scale.

They favor the web. Companies that deliver web-based products and services, such as e-commerce, SaaS, PaaS, and consumer web and mobile, tend to experience turbo-charged global growth, simply because they can take their software or website international without making a large investment.

Even companies in industries that pre-dated the web, such as manufacturing and pharmaceuticals, tend to have faster rates of global growth if they invest heavily in online and software-based models for strategic areas of the business. Moving to the web makes a company more nimble and capable of responding to opportunity in international markets.

They work with the right partners. High-performing global businesses have an ecosystem of channel relationships, resellers, and partners to help them expand internationally. Carefully choosing international partners is important at the onset of entering markets overseas, and especially when trying to push out competitors to become the market leader. Apple’s partnership with China Mobile, the largest wireless network in the world, helped the company become the no. 1 smartphone maker in China. One year after the deal was announced, the company moved past five local competitors that previously dominated. Likewise, Uber recently announced a relationship with Starwood Hotels that will help it strengthen its presence in 100 countries.

They know their metrics. All of the companies I’ve worked with that have seen their global revenues soar are diligent about analyzing international and domestic sales and marketing data.

Companies that struggle with international growth tend to have a hard time answering these basic questions: What are your top 10 countries by revenue share? By customer base? What percentage of your marketing budget is allocated toward international? What percentage of your sales team? Often, just the exercise of obtaining this data helps a company get a better understanding of their true international picture.

They value the opportunity. When advising executives, I watch closely to see how they talk about international business. Does the company think about international markets as a strategic advantage, a hassle, or something in between? High-growth companies view global markets as an area of largely untapped opportunity that simply must be explored. They talk about global business as an investment in the future, a way to diversify and achieve scale.

Companies that aren’t as destined for global success will interpret the same data negatively, viewing global markets as more of an annoyance than an opportunity. They tend to underestimate the revenue they currently obtain from international markets, and they view any spending on global markets as a cost to be reduced.

They put the customer first. The businesses I’ve seen with the strongest track record of global success all have this important mission in common. If the customer lives outside of their home markets, customer-centric organizations make an even greater effort to go the extra mile (or kilometer). They view global marketing and localization not as a burden, but as an advantage against competitors, which enables them to attract customers in other markets, better serve them, and convert them into advocates for their brands.

They take international strategy seriously. Companies must value the people and processes that are critical to global endeavors. Driving international revenue, at most modern businesses, hinges on two key functions within the company: global marketing and localization. Fast-growing companies prioritize these areas, usually by assigning an executive who helps drive strategy for international markets.

Businesses with unimpressive global trajectories make the common mistake of diluting the importance of international growth, either by placing ownership at lower levels of the organization that cannot influence strategy or within multiple silos across the organization. When globalization becomes decentralized and has no clear owner, the business struggles to coordinate all the moving parts and drive international strategy forward.

When proper support for globalization is in place, the end result is a “global first” culture. Employees throughout the company begin to display a globally-minded attitude, which spills over into business processes. The engineering team builds software with international users in mind. Content creators think about their audiences in different countries before translation ever happens. Executives frequently discuss the importance of international customers. Global becomes a strong driver of the company’s growth and future.

[image error]

If You Want to Be the Boss, Say “We” Not “I”

The royal “we” has a long and interesting history. Many attribute its first usage to King Henry II, who in 1169 used it to imply he was speaking for both himself, and for God. Overtime, leaders began to use it to imply them and their constituents (a distinction that got a little blurry when Margaret Thatcher proclaimed “we have become a grandmother” and got a significant amount of chastisement). But beyond using the plural pronoun to indicate that you speak on behalf of a others (or deity), it turns out that using “we” could also mean you’re more considerate of others and possibly even a better leader.

A team of researchers – Ewa Kacewicz, James W. Pennebaker, Matthew Davis, Moongee Jeon, and Arthur C. Graesser — studied the use of pronouns by individuals in a variety of contexts. Their theory was that pronoun usages (first-, second- or third-person and singular versus plural) could provide clues to an individual’s status inside a group or a hierarchy and possibly their likelihood of attaining higher status.

Pronouns help to signify a speaker’s focus of attention. When people feel insecure, self-aware, or diminished, they are more likely to focus their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors inward. Indeed, studies suggest that people manipulated to focus inward often increase the rate of first-person singular pronouns (such as “I,” “my,” or “me”) used in their speech. By contrast, the researchers theorized that individuals using first-person plural and second-person (such as “we,” “us,” or “you”) ought to demonstrate an outward focus, considering the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of others.

In addition, researchers suggest that an outward focus is an important requirement of those who hold, or look to attain, status. Status in a group is often conferred or legitimated by the group being led. Because of this, they theorized, individuals who demonstrate a strong focus on the group and its members (instead of on themselves) often attain higher status. Those who are self-focused would get looked down on, regardless of whether they held positions of authority. Perhaps the pronoun was a small, but potent, signal to others.

To test these assumptions, the researchers designed five separate studies in which language was used in a variety of contexts, but all in situations with status differences between the people communicating. In the first study, participants were placed in four-person groups with a randomly chosen leader and given a decision-making task. In the second and third, two-person teams were either given a series of problems to solve or tasked to talk informally through an online chat forum (and later self-reported their assessment of status relative to the other person). In the fourth study, nine volunteer participants submitted their email correspondence with up to 20 other individuals and self-reported their status relative to each individual. The fifth study was perhaps most interesting; the researchers collected 40 letters written by soldiers in the Iraqi military under Saddam Hussein (obtained through the Iraqi Perspectives Project). Half of these letters were written from higher ranked offers to lower ranks and half by lower ranked to higher ranked officers.

In their analysis of all five scenarios, published in the Journal of Language and Social Psychology, the researchers found surprisingly consistent results. Individuals with lower status overwhelmingly tended to use first-person singular pronouns (“I”) compared to individuals with higher status. Likewise, higher status individuals used significantly more first-person plural (“we”) pronouns relative to those with lower status (the only exception to the “we” effect was found in the fourth study, of natural use emails and self-reports of status). Second-person pronouns (“you, your”) also appeared more frequently in the language of high status participants in all five studies, though the effect was weaker than “we.”

The studies’ results imply that higher-status individuals do demonstrate an “others-orientation” significantly more than lower status individuals. Likewise, lower status individuals appear more self-oriented. All five studies were correlational, so its difficult to tease out whether an others-orientation was a cause of rising status or a simply result of operating at a higher status. In either case, however, the studies’ results underscore the importance of an others-focus for those seeking to rise in their organizations.

While switching from singular “I” to the plural “we” may not make you a king or win you a premiership, it might help shift your perspective from self-focused to others-focused, make you more aware of the needs of others and, as you work to meet those needs, might just make you a better leader.

[image error]

Training Police Departments to Be Less Biased

Fierce debates about biased policing continue to resonate across the United States, and they’re playing out on front pages again after a special investigation into the Ferguson, Missouri police department. The investigators concluded that the white police officer who shot Michael Brown, a black man, was justified in his use of force. But they also found that the Ferguson police department had over-policed the town’s black population. And they turned up multiple email messages rife with virulent racism.

Of course, police departments are not the only organizations confronting some uncomfortable truths about their biases — corporations have been in the hot seat on this as well, although there the recent discussions have mostly centered on gender, whether it’s equal pay, the , or the treatment of women in industries such as technology.

Whether it’s racial or gender bias, there is a lot at stake. To figure out how police departments are responding, I spoke with Anna Laszlo, director of Fair and Impartial Policing, a consultancy that has helped to train police departments and law enforcement agencies. Among others, they’ve worked with police departments in Milwaukee, Baltimore, Los Angeles, Detroit, Minneapolis, St. Louis, and Tucson. What follows is an edited version of our conversation.

HBR: Do the standards of bias training need to be different in police departments? Or is it pretty much like any workplace?

Laszlo: In terms of the role of implicit bias, the science is the same. The science tells us that if you hire from the human race, you’re going to be hiring biased individuals. There’s an extensive and growing body of research across all professions — doctors, lawyers, judges, real estate agents, teachers, and yes, police as well, that points to implicit bias in human beings.

[The difference is] that the stakes for policing are so incredibly high. Police officers are the only people in a democratic society who can legally take your freedom, and can legally, justifiably take your life. So with all due respect to my colleagues in other professions, the stakes for policing are significantly higher.

We also know that the police are most effective when they police their communities with the collaboration and authority of the people they serve. Police legitimacy is significantly harmed if there is no trust between the police and the community, and clearly biased policing can significantly impact that trust.

You mentioned the extensive research that’s out there on implicit bias, and I know that’s a big part of your training approach. Why emphasize the science? Why start with that?

It’s important to start with the science because the science is egalitarian in some ways. Scientific data is scientific data. The science helps us to understand that all of us as human beings come with implicit biases. That moves the discussion from an accusatory perspective of “You are racist, you are homophobic” to one of, “You’re human.” We often say early on in the training session, “If the worst thing you learn about yourself today is that you’re a human being, so be it.”

Your trainings focus on implicit bias, but I also want to ask you about explicit bias. The emails now coming out of Ferguson show that at least some police force members in Ferguson showed explicit bias. Those emails are pretty explicit.

They are.

So is a different intervention approach needed for explicit bias?

The short answer is is yes, but there’s a caveat. Clearly, you cannot lead an organization and have those sorts of biases rampant within your organization. I would humbly submit that the very fact that people felt comfortable, in a work email, expressing those sorts of biases and using that language really is an organization-wide failure. There’s no place for that in our organizations or in our society. It’s the role of leaders up and down the organization to identify those behaviors and immediately put an end to them.

Typically what happens is that [leaders] identify the person who expressed the explicit bias and fire them. Which is appropriate, but if you believe that your only problem within the organization is those few bad apples, and your solution is to get rid of those people and — lo and behold — you’ve solved the problem, well, that’s not the case.

What happens if organizations stop at just rooting out explicit bias, rather than also tackling implicit bias?

If your [assumption] is that only racist and explicitly biased employees exhibit biased behavior, then your solution [of firing them] results in organizational complicity — your organization can wash its hands, because you’ve gotten rid of those people. But the science says we all have implicit biases, and even if we don’t express them, they can still be operational.

Research has really helped us to refine our understanding of “this is your brain on bias”…[as well as] how we [can] override those biases. We now know that the first step is to recognize that we have these biases, recognize when our biases are kicking in, and then apply what social scientists call controlled behavior. We can develop skills to not let our biases impact our behavior.

How does that training need to differ if you’re talking to beat cops versus managers or supervisors?

For policing, our training is divided into three modules. The first is all about the science of human bias, and everyone needs to know that.

The second really looks at the impact of biased behavior on the organization as well as the individual. Here we talk about ethical cultures, the role of police legitimacy, and we spend a fair amount of time understanding the history of American policing, understanding our civil rights history, the history of our gay rights movement, and understanding immigrants who have come to this country from nations in which the police are not seen as a legitimate authority, nations where the role of the police is to suppress. For some of these officers, their response is, you know, “I wasn’t even born when Pol Pot was killing people in Cambodia, and now I have a community of Cambodian immigrants and I don’t understand why they won’t talk to me.” So it’s important to understand that history.

Then we look at the skills people need within the organization at different levels. If you’re a patrol officer, the application of the science to your skill is that you need to recognize bias, avoid policing by proxy, slow situations down so you have time to think before you act, and continually ask yourself, “Would I be dealing with this person in this manner but for if they weren’t X?”

When we talk about supervisors, the skills are much different. We talk about how to identify potentially biased behavior in your direct reports, for example, by taking a look at records of traffic stops, citizen complaints, other officer complaints. Is there disproportionality in the way a particular officer is using their enforcement powers?

For chief executives we focus on developing organizational policies and a comprehensive approach, based on seven elements, to creating a fair and impartial policing organization. Those are assessing policy, writing new policies, measurement, supervisory accountability, training education, outreach, and community engagement.

But everyone within the organization, including that patrol officer, has a leadership responsibility. Everybody needs to notice bad behavior, and to create a climate of speaking up. Paying attention to the small stuff is important, because small transgressions can turn into large ones relatively quickly.

We’ve talked about over-policing certain populations. But of course, bias cuts both ways: when one population is over-policed, there may be another that’s under-policed. What’s the impact of that?

If an officer is under-vigilant because they presume that someone who looks like me could not be dangerous, they may be significantly slower in responding to me. We have heard a number of examples from police officers [who had assumed that an] elderly female, a pregnant or tiny female, or an elderly male wasn’t dangerous, when in fact they were heavily armed. The flipside is that if you associate certain races or ethnicities as potentially dangerous, that you may become overly vigilant and think someone is dangerous when they are not. In both cases someone is getting killed. In one case it’s a police officer, while in the other it could be a citizen. So biased policing can have two deadly effects.

What’s an example of the kind of training you can do to mitigate that?

We do a role-play called “Woman/Man with a Gun” designed to teach the officers that assuming a woman is safe is pretty unsafe for you. They get called to a scene where there are several people, men and women, and are told to find the person with the gun. When the woman is the one with the gun, they either don’t find it at all, or they take much longer than when we do the same role-play with a male.

How do the officers respond to exercises like role-playing?

Well, there can be some pushback. I don’t mind that. There’s a little bit of, sometimes, “C’mon, would this really happen?” But you never know how what will happen in these training programs. When we were doing this exercise in Las Vegas, I remember an officer in the back of the room who raised his hand and said, “You know what guys, remember the case where there was that Walmart shooting?” This was a case where they’d lost two officers to a man and a woman who’d holed up in a Walmart. And this officer [had been at the scene], and it was the girlfriend [who shot at police]. When he was telling this story, you could have heard a pin drop. It was silence. And he talked about, “Yeah, you know, this happened to me for real. I almost got killed. I was almost not here.”

[image error]

How Counseling About Work Reduces Depression

Depression is a nimble beast that can creep into pretty much every aspect of life, including work. That takes a toll on a personal level, but there are also organizational effects. According to Debra Lerner,the director of the Tufts Medical Center Program on Health, Work and Productivity, depression is one of the few diseases that always comes up as one of the top five reasons behind productivity loss at any company she studies.

As noted in her latest research, depression costs around $44 billion per year in lost worker productivity in the U.S. Sometimes this occurs when people call out sick; at other times, it’s due to what’s called presenteeism, defined as “the problem of workers’ being on the job but, because of illness or other medical conditions, not fully functioning.” Depression, it’s been found, can lessen a person’s personal productivity by one-third or more.

Lerner and her co-authors wanted to test whether a fairly simple intervention could improve the work lives of people with the illness, and thus their absenteeism and presenteeism rates as well. So after screening people age 45 or older at 23 organizations for depression, they enrolled and randomized 380 of them into two groups: One got telephone-based counseling focused on recognizing when someone’s depression was impeding their work, and then working with him or her to develop strategies for dealing with it. The other got what she calls usual care – “which was anything that people care to use, really.” The status quo, essentially.

After eight sessions with the counselors over a four-month period, those in the first group saw a marked improvement in their symptoms – a 51% drop in mean depression symptom severity scores, compared to a 26% drop for the control group. In addition, their rates of both presenteeism and absenteeism were reduced significantly: the time that people weren’t able to perform tasks at work dropped 44% (compared with 13% in the control group) and the days they were absent from work dropped 53% (again compared to 13% in the control group).

The researchers also quantified the benefit-to-cost ratio for such a program annually, per employee: for every dollar spent, the organization saw $6.19 in improved productivity. Lerner notes that while they “only followed participants until the fourth month post-enrollment and projected the savings in productivity if the effect lasted for a full year,” it’s still fair to say that the program was effective and saved money.

Why was the telephone-based counseling so effective at improving work performance? Lerner explains that in the U.S. in particular, treating depression “is really based on a biomedical model of reducing symptoms.” This, obviously, is important. “But the treatment does not necessarily concern itself with whether or not people can function at work,” she continues. “And even if companies did know what the impact was, they wouldn’t really have the strategies to intervene.”

So, for example, the telephone counseling sessions put the way someone’s work was organized front and center. Common questions included, ”How can I perform my work when I’m not feeling well? How can I stay focused on my work? How can I keep pace throughout the workday when work is chaotic and I’m not feeling up to what I can normally do?”

In order to get to these questions, the treatment plan was broken into three main steps: First, getting the employee to recognize the thread that ties together depression and work. “Many people haven’t made that connection,” says Lerner. “They think problems at work are simply problems at work, and everything else is just their depression.” This step also worked to make sure the employee and their health care provider were on the same page in terms of all of the treatment options available to them.

Next came cognitive behavioral strategies, which starts with understanding how “counterproductive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors associated with their depression get in the way.” If you’ve ever experienced depression, this mental loop won’t be much of a surprise: “People may be sitting at work and ruminating about how nobody really wants to be involved with them and nobody cares for their input anymore,” explains Lerner. “So they get more socially isolated and don’t get the appropriate feedback they need about their work, or they may even snap at other people and lose supportive connections we all need to get our work done.”

Third, the counselors worked with people on very specific, concrete strategies for getting work done. This could include things like making small changes to their environment, like organizing documents differently or closing a door if they’re regularly interrupted; getting enough sleep; and learning new ways to organize email to make it more organized and, thus, less stressful.

One important point about this research: It was done in conjunction with health care providers and not directly with the companies where the participants were employed. In part this was because depression treatment is currently located in the medical and behavioral health care system, not in the workplace. But that doesn’t mean companies can’t learn from this program. While smaller companies tend to be either very supportive or not, Lerner says that mid-to-large companies are finally understanding “what depression is, how costly it is to themselves, their employees, and their family members, and are increasingly trying to put programs in place to help people get better care.”

[image error]

March 5, 2015

5 Myths of Great Workplaces

Suppose that later this evening, after you have stepped away from your keyboard, put on your coat, and traveled home for supper, your organization underwent a magical transformation, reshaping itself into the world’s best workplace.

How would you know? What would be different the next time you entered the building?

When we think about extraordinary workplaces, we tend to think of the billion-dollar companies at the top of Fortune magazine’s annual list. We picture a sprawling campus, rich with generous amenities; a utopian destination where success is constant, collaborations are seamless, and employee happiness abounds.

But as it turns out, many of the assumptions these images promote mislead us about what it means to create an outstanding workplace.

In recent years, scientists in a variety of fields have begun investigating the conditions that allow people to work more successfully. As I explain in a new book summarizing their discoveries, not only are the factors that contribute to creating a great workplace not obvious—often, they are surprisingly counterintuitive.

Consider these five “great workplace” myths:

Myth 1: Everyone Is Incessantly Happy

Over the past decade, the happiness literature has produced some compelling findings. Research conducted in lab and field experiments indicates that when people are in a good mood, they become more sociable, more altruistic, and even more creative.

Not surprisingly, many organizations have attempted to capitalize on these outcomes by searching for ways to boost employee happiness. In many ways, it’s a welcome trend. Surely, a workplace concerned about the mood of its employees is preferable to the alternative.

But happiness also has a surprising dark side. When we’re euphoric, we tend to be less careful, more gullible, and more tolerant of risks.

Not only is workplace happiness occasionally counterproductive, there is also value to so-called “negative” emotions, like anger, embarrassment, and shame. Studies indicate that these emotions can foster greater engagement by directing employees’ attention to serious issues and prompting them to make corrections that eventually lead to success.

Instead of espousing positivity at all costs, leaders are better off recognizing that top performance requires a healthy balance of positive and negative emotions. Pressuring employees to suppress negative emotions is a recipe for alienation, not engagement.

Myth 2: Conflict Is Rare

Workplace disagreements, many of us implicitly believe, are undesirable. They reflect tension in a relationship, distract team members from doing their jobs, and therefore damage productivity.

But research reveals just the opposite: in many cases, disagreements fuel better performance.

Here’s why. Most workplace disagreements fall into one of two categories: relationship conflicts, which involve personality clashes or differences in values, and task conflicts, which center on how work is performed. Studies indicate that while relationship conflicts are indeed detrimental, task conflicts produce better decisions and stronger financial outcomes.

Healthy debate encourages group members to think more deeply, scrutinize alternatives, and avoid premature consensus. While many of us view conflict as unpleasant, the experience of open deliberation can actually energizes employees by providing them with better strategies for doing their job.

Workplaces that avoid disagreements in an effort to maintain group harmony are doing themselves a disservice. Far better to create an environment in which thoughtful debate is encouraged.

Myth 3: Mistakes Are Few

Suppose you’ve just been hired to oversee two teams. Before your first day on the job, you receive a report summarizing each team’s performance during the past year. One statistic immediately jumps out: In the average month, Team A reports 5 errors. Team B reports 10.

Which team is more effective?

On the surface, the answer seems obvious. Of course Team A is better—after all, the data show they commit half the number of mistakes. But are fewer errors really the best metric of a team’s success?

In the mid-1990s, Harvard researcher Amy Edmondson conducted a study looking the performance of nursing units at a university hospital. What she expected to find was a simple correlation; one showing that units with the best managers and coworker relationships recorded the fewest drug treatment errors. Instead, she found the opposite.

Much to Edmondson’s surprise, nursing units with better nurse-manager relationships reported significantly more drug treatment errors, but not because they were less effective. They were simply more comfortable admitting mistakes when they happened.

Edmondson’s research underscores an important point. To achieve top performance, we must first recognize and learn from our mistakes. And for that to happen within a workplace context, for employees to willingly acknowledge errors, they need an environment in which it feels safe to have honest dialogue.

Paradoxically, fostering top workplace performance requires a new way of looking at failure. Instead of treating mistakes as a negative consequence to be avoided at all costs (thereby making employees reluctant to acknowledge them), organizations are better off making improvement rather than perfection a primary objective.

Myth 4: They Hire for Cultural Fit

Organizations no longer select job candidates solely on the basis of their skills or experience. They hire those whose personality and values are consistent with their company culture. Among the more vocal proponents of this approach is Zappos, the online shoe distributor. But lots of other companies have extoled the virtues of hiring for cultural fit.

The idea holds intuitive appeal: When employees share similar attitudes, they’re more likely to get along, and more likely they are to produce. Right?

Not necessarily. There’s a point at which too much similarity can stifle performance. For one, similarity fosters complacency. We get stuck doing things the way we’ve always done them because no one is challenging us to think differently. Similarity also breeds overconfidence. We overestimate the accuracy of our opinions and invest less effort in our decisions, making errors more common.

In a 2009 study teams of three were asked to solve a problem with the help of a new colleague who was either similar or dissimilar to the existing group. While homogenous teams felt more confident in their decisions, it was the diverse teams that performed best. The newcomers pushed veterans to reexamine their assumptions and process data more carefully—the very thing they neglected to do when everyone in their group was similar.

Finding the right degree of cultural fit in a new hire is tricky. When the work is simple and creative thinking is rarely required, a homogenous workforce has its advantages. But the same can’t be said for organizations looking to be on the forefront of innovation. Here, exposing people to different viewpoints can generate more value than ensuring that they gel.

Myth 5: Their Offices Are Full of Fun Things

On every list of great companies to work for, the top organizations offer lavish amenities. Twitter, for example, has a rock-climbing wall. Zynga lines its hallway with classic arcade games. Google provides a bowling alley, roller-hockey rink, and volleyball courts, complete with actual sand.

Given the frequency with which resort-like workplaces are recognized, it’s become easy to assume that to build a great workplace, you need to turn your office into an amusement park.

Not true. To thrive at work, employees don’t require luxuries. What they need are experiences that fulfill their basic, human needs. As decades of academic research have demonstrated, we perform at our best when we feel competent, autonomous, and connected to others.

What differentiates great workplaces is not the number of extravagant perks. It’s the extent to which they satisfy their employees’ emotional needs and develop working conditions that help people produce their best work.

For too long, we’ve relied on assumptions when it comes to improving our workplaces. Isn’t it time we looked at the data?

[image error]

The Sharing Economy’s New Middlemen

The sharing economy is usually thought of as a way for some people to make extra cash by renting an asset they already own, such as their home or car. But today, the sharing economy is becoming professionalized – for some, it’s no longer a secondary source of income, but a primary job. As this shift has taken place, several shrewd entrepreneurs have set themselves up as middlemen – a concept once unimaginable in the sharing economy.

These middlemen are finding a market for their services as the sharing economy reaches an inflection point. In a recent survey, Nielsen found out that two out of three people are willing to participate in the sharing economy, either by sharing/renting their own assets, or by renting others’.

Who are these entrepreneurial middlemen and what business are they building? Here are three categories I find particularly compelling: the power-sharer, the power-operator, and the power-organizer.

1. The power-sharer: optimize asset selection and utilization.

In large cities, where there is lots of demand, power-sharers choose to buy assets in order to rent them to participants in the sharing economy. Consider Breeze. For a membership fee and a weekly fee, they’ll lease you a car you can use to fuel your own sharing economy business, whether it’s as a driver for Lyft, a shopper for Instacart, or a cleaner for Homejoy (or all three). And unlike with a traditional lease, you can cancel your car with just 2 weeks’ notice.

YardClub provides an interesting variation on the power-sharer: it lets contractors rent out their tools and equipment to a screened set of renters, while providing insurance. Members can rent equipment by the hour, using it either for their own projects, or to perform a job for another sharing economy company like TaskRabbit.

2. The power-operator: empower freelancers with insightful tools.

Many sharing economy marketplaces cater to a very large population of sharers. Often, these sharers have no idea how to run a business nor the time or desire to learn. For instance, say you move for a job and decide that rather than selling your apartment, you’ll rent it on Airbnb or HomeAway. These would-be sharers lack the tools they need to run their operation efficiently. How will they screen all the applicants and make sure the apartment is cleaned between each guest? And if they really wanted to ramp up, they’d need an inventory management system, a real-time analytics engine, an automated pricing tool, and so on.

But a few power-operators have started to offer these tools. A company like Pillow will clean after each guest, or optimize price and occupancy rate in exchange for a commission on rent generated via Airbnb. For a small monthly fee per driver, ZenDrive screens would-be drivers and, once they get the job, monitors their performance.

3. The power-organizer: organize community and build trust.

One downside of the sharing economy is that each individual sharer has to learn on his or her own what works and what doesn’t. There’s no union talking about safety, no manager talking about identifying the most profitable opportunities. There is a need for communities in which sharers exchange knowledge. One example is the ride share guy, who has started to provide advice to drivers on optimizing their income from the different car sharing marketplaces. Power-organizer Peers.org takes this to the next level by offering a platform to organize, curate, moderate participants in the sharing economy, both its freelance population and its customers.

The sharing economy can be a huge source of social mobility and financial wealth, powered by social networks. Before it becomes mainstream and large industry incumbents place their bets, there are opportunities for clever and ambitious entrepreneurs to capture a meaningful share of this large and fast growing market.

[image error]

Why Leaders Are Easier to Coach than Followers

Photo by Andrew Nguyen

Followers receive very little fanfare. In a culture obsessed with leaders, we think of follower’s role as submitting, taking direction, and dutifully executing the leader’s will.

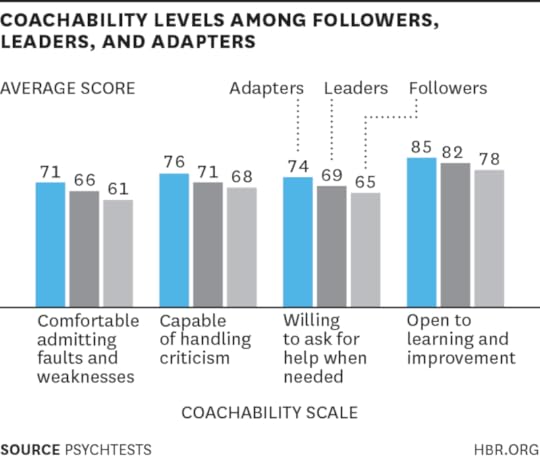

Recent research from PsychTests, however, reveals that followers may not be as compliant as we assume. In a study that measured individuals’ openness to coaching, PsychTests discovered that people who identify as followers are actually less open to coaching than people who identify as either leaders or adapters (those who are comfortable leading or following depending on the circumstances).

Across these three groups (and 380 total respondents), followers proved least willing to take direction or criticism, least comfortable admitting their faults and weaknesses, least willing to ask for help, even when they need it, and least open to learning and improvement.

So why do they lag behind the other groups in terms of coachability? “The answer lies in their perspective—what coaching means to them,” explains Dr. Ilona Jerabek, the President of PsychTests. Most of us have trouble taking criticism. But followers in particular “seem to have a self-confidence issue. Being criticized makes them feel weak, incompetent, or incapable…. When you offer coaching or training to followers, they may take it as an indication that something is wrong and that’s why they need help.” While they may realize on some level that a manager’s desire to coach them is actually a good thing, “they still see it as an indication that ‘I’m not good enough,’” which can generate resentment.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Coaching Ebook + Tools

Managing People Ebook + Tools

39.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

People who identify as adapters, on the other hand, tend to see coaching as an opportunity. Adapters outscored both followers and leaders on many coachability scales. 82% of adapters actively pursue learning opportunities, compared to just 52% of followers. 91% recognize that even negative criticism can be helpful compared to just 77% of followers, and 57% of adapters seek out feedback from their managers, while only 37% of followers do so.

Should employers care about coachability? Is there a correlation between coachability and performance? PsychTests analysts think so. “In today’s businesses, people need to wear many hats,” says Jerabek. A team member who isn’t willing to learn new things, or to work outside of their job description, can bring the whole team down. “What you want is people who are capable of adapting to or growing into different roles, people who want to work on their skills and improve their performance.”

It’s worth noting that scores for coachability across all survey participants was fairly high, indicating that most people are open to coaching. Because responses were self-reported, there’s also the possibility that people over- or under-estimated their level of coachability. However, there are important lessons both for managers and individual employees in these results.

First, managers need to support their followers. Analysts at PyschTests recommend that bosses try to help followers overcome insecurity. “Help them recognize that you [want to coach them] because you see their potential,” Dr. Jerabek suggests. “Make sure they understand that your company wants to invest in them because they are worth it, that [coaching] is an opportunity rather than a punishment.” Managers who want their feedback to stick should be patient and focus on delivering criticism in a constructive way. Reassure your people that it’s OK to make mistakes and that everyone has weaknesses

Second, companies need to do a better job of communicating the reasons for coaching or training, Jerabek adds. Make sure employees know that they aren’t being singled out for bad performance but that coaching is an investment in their development.

Third, hire adapters. It’s advantageous to have employees who are versatile, can both lead and follow, and are open to feedback and learning. How do you identify them? Make sure you ask for examples that demonstrate a willingness to hear criticism during the interview process. Most people will tell you what you want to hear when you ask for this, so it’s important to go beneath the surface. Inquire whether candidates liked school. Do they enjoy trainings? And pay attention to non-verbal cues. Some people may cringe while others will respond with wide-eyed enthusiasm about learning experiences.

Lastly, don’t count out older workers. The PsychTests study also revealed that the older we get, the more open to coaching and the less susceptible to “know-it-all-ism” we become. Older workers tend to be more confident in their abilities and less likely to take criticism personally—something we could all stand to get better at.

As for those resistant followers, Jerabek recommends keeping in mind that nobody is perfect. “In order to benefit from coaching, you need to be willing to put your ego aside and accept guidance and criticism, as painful as it may be.” And learn from the leaders and adapters of the world: asking for help is not a sign of weakness. On the contrary, PsychTests data show that those who achieve their goals often turn to others for help and advice and are quick to admit when they don’t know something. They also actively seek feedback and opportunities to stretch themselves. Self-awareness, Jerabek says, is the key. We must see our strengths and weaknesses clearly in order to develop—and advance in our careers.

It’s not a bad thing to be a follower. In many roles and situations, someone who takes direction is exactly what an organization needs. But closing off to criticism, coaching, and self-improvement is a bad thing—especially from the perspective of organizations and hiring managers. PsychTests created this survey in response to requests from clients who were looking for a tool to assess coachability among job candidates. So the next time you’re up for a promotion, applying for a new position, or responding to criticism from your boss, remember: people who are open to feedback, willing to ask for help, and eager to learn new things are in demand—and are more likely to achieve their goals.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers