Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1322

February 9, 2015

There’s No Such Thing as Anonymous Data

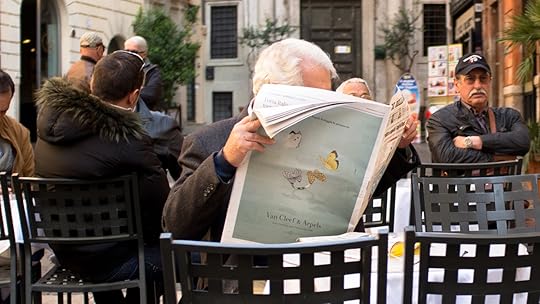

Photo by Andrew Nguyen

About a decade ago, a hacker said to me, flatly, “Assume every card in your wallet is compromised, and proceed accordingly.” He was right. Consumers have adapted to a steady thrum of data breach notifications, random credit card charges, and out-of-the-blue card replacements. A privacy-industrial complex has sprung up from this — technology, services, and policies all aimed at trying to protect data while allowing it to flow freely enough to keep the modern electronic bazaar thriving. A key strategy in this has been to “scrub” data, which means removing personally identifiable information (PII) so that even if someone did access it, they couldn’t connect it to an individual.

So much for all that.

In a paper published in Science last week, MIT scientist Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye shows that anonymous credit card data can be reverse engineered to identify individuals’ transactions, a finding which calls into question many of the policies developed to protect consumers and forces data scientists to reconsider the policies and ethics that guide how they use large datasets.

De Montjoye and colleagues examined three months of credit card transactions for 1.1 million people, all of which had been scrubbed of any PII. Still, 90% of the time he managed to identify individuals in the dataset using the date and location of just four of their transactions. By adding knowledge of the price of the transactions, he increased “reidentification” (the academic term for spotting an individual in anonymized data) to 94%. Additionally, women were easier to reidentify than men, and reidentification ability increased with income of the consumer.

To be clear: Reidentification means that the researchers could identify all the transactions that belong to an individual, but de Montjoye didn’t attempt to say which individual. For example, if he wanted to know my transactions, he’d need to take additional steps to cross reference something he knew about me to his data. If, for example, I posted on Facebook about a trip to a restaurant, that could provide the key to connecting me to an entire portfolio of anonymous transactions. “We didn’t try to put names on it,” de Montjoye says, “but we know basically what you need to do that.”

What’s more, de Montjoye showed that even “coarse” data provides “little anonymity.” He lowered the “resolution” on his data by looking only at areas where purchases happened, not specific shops, and 15-day time frames in which they happened, not specific dates. He also broadened the price range of the purchases so that transactions that previously were categorized as between $5 and $16 were now put in a bin more than twice as big that ranged between $5 and $34. Even with low-res data like this, he could pluck out four transactions and reidentify individuals 15% of the time. By looking at 10 such data points, he could, remarkably, reidentify individuals 80% of the time.

It’s not the first time de Montjoye has played the part of privacy killjoy. In previous work he pulled off a similar trick, reidentifying individuals using anonymous mobile phone location data. (Others have performed similar parlor tricks with other datasets.) And while he hasn’t yet tested other types of large datasets, such as browsing histories, he believes that “it seems likely” that they, too, are susceptible to reidentification.

The implications of de Montjoye’s work are profound. Broadly, it means that anonymity doesn’t ensure privacy, which could render toothless many of the world’s laws and regulations around consumer privacy. Guaranteeing anonymity (that is, the removal of PII) in exchange for being able to freely collect and use data — a bread-and-butter marketing policy for everyone from app makers, to credit card companies — might not be enforceable if anonymity can be hacked. Anonymization as we define it today, de Montjoye says, is “inadequate” and ultimately doomed to fail with large metadata — the kind of publicly available big data that so many companies are tapping into. (He won’t use the term “big data,” but what he describes as “metadata datasets” are largely in line with that concept).

One obvious response to this problem, being explored in Europe, is to make anyone who wants to use such data prove that they’ve made it impossible to identify individuals within the dataset. But if de Montjoye can identify four out of five people from anonymous data with only a general sense of where they were, when they were there, and how much they spent, it’s hard to imagine someone proving beyond a doubt they’ve anonymized their data. That kind of mandate, then, could ultimately prohibit the use and sharing of data.

That would be a terrible outcome given the power of the kinds of large datasets de Montjoye is testing. “The potential for good that comes from this kind of data is too great to shut it down,” he says, citing any number of cases: Mobile data can be used in the fight against the spread of disease. Traffic data can enable smarter traffic systems that significantly reduce emissions. Economic data tracking can help identify opportunities for innovation and growth.

One model de Montjoye cites is “PII 2.0” (PDF) proposed by Paul M. Schwarz and Daniel Solove. Currently, PII is binary and information is either personally identifiable or not. Schwarz and Solove propose a spectrum from those two ends, with a third category in between, in which identification is possible but not probable, and then regulation that addresses each type separately.

de Montjoye also looks to the “New Deal on Data” proposed by MIT’s Sandy Pentland (a co-author on de Montjoye’s paper) in which ownership rights of data shift to the consumer.

“Our goal is to start a debate, not shut down the use of this kind of data,” says de Montjoye. “This is a potential risk with these large datasets; anonymization is limited, but the potential uses for this data are great. So let’s find a better model. Let’s find a balance between privacy and utility.”

[image error]

February 6, 2015

How Do You Rank the World’s Best CEOs?

How do you measure a CEO’s impact? An HBR team recently addressed that question by ranking CEOs according to the increases their companies have seen in total shareholder return and market capitalization across their whole tenures. HBR’s resulting list of the 100 Global CEOs who have delivered the best financial results, published in its November 2014 issue, placed Amazon.com’s Jeff Bezos squarely at the top.

There’s no doubt that Mr. Bezos has done well for the company he founded. And clearly CEOs can and should be judged by the financial results they generate. But increasingly, CEOs and their companies are also being called to account for their impacts on employees, communities, governments, and society at large. The changing expectations have magnified the relevance of non-financial metrics and the need to paint a more complete picture of a CEO’s performance.

Companies now need to understand what value they are creating, not only for their investors, but also for their employees, customers, and society at large – and they need to know how their reputations reflect this net value creation. This is why Reputation Institute regularly surveys people around the world about their perceptions of companies, and produces a ranking on this score. It’s also why, since 2000, individual companies have consulted the Institute to gain a deeper understanding of how well they are regarded on non-financial metrics – and why. To develop consistent and reliable data, we rely on a scientifically developed and standardized survey instrument designed to gauge public perceptions of companies on seven dimensions: finance, leadership, workplace, citizenship, governance, products, and innovation. We call it the RepTrak scorecard.

When HBR invited Reputation Institute to add a nonfinancial perspective to its top 100 CEOs coverage, our team of researchers, led by Dr. Leonard Ponzi, Brad Hecht, and Viktoria Sadlovska, began with the RepTrak methodology, and created a special “non-financial performance index” using a subset of its categories – specifically, the scores for each company’s workplace, citizenship, and governance. Based on those scores, we reranked HBR’s list. (Note the caveat that our data reflect perceptions of companies, not individual CEOs. The assumption here is that, because most of these value-adding leaders have had substantial tenures, the reputations of the firms, no less than their financial success, reflect these individuals’ leadership. )

Next, we set out to examine more closely the relationship between HBR’s financial indicators and our non-financial indicators of performance.

Based on our past research, we thought it likely that companies with higher reputations would tend to financially outperform those with lower reputations. On average, we have found that high-reputation companies have higher returns (both Return on Assets and Return on Equity), deliver higher earnings multiples, have higher market/book ratios, and have a higher Enterprise Value/EBITDA ratio – the key measures on which investors assess corporate performance.

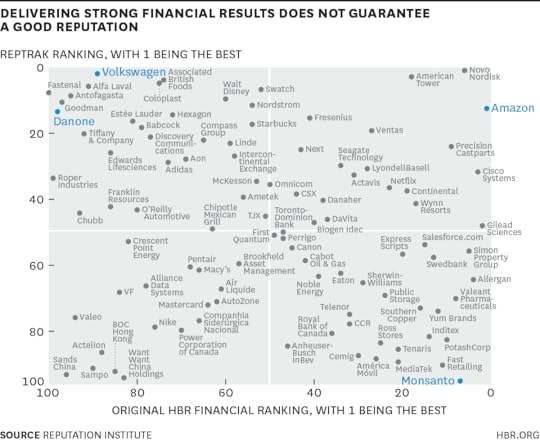

But the scatterplot presented below demonstrates clearly that, within this set of top CEOs’ companies, there is not a linear relationship between financial and non-financial measures of performance; companies that deliver strong financial results do not always have good reputations with the public, and vice versa.

Look, for instance at the company names in the lower-right quadrant – the ones who did well financially but not so well on reputation. Monsanto is a case in point, its CEO ranked #8 on HBR’s financially based ranking, despite having the weakest reputation of all the companies. Meanwhile the upper-left quadrant of the chart is also well populated. These are the companies earning the highest public respect, but turning in lower financial results. (Again, let’s keep in mind that all these companies are financial high performers in the greater scheme of things; otherwise they would not be on HBR’s list.) Germany’s car manufacturer Volkswagen stands out in this regard, as does France’s food giant Danone. Both of their CEOs were well down the list of HBR’s top 100, but have managed to win their companies high praise from the public on non-financial criteria. In general, the broad dispersion across quadrants shows that financial and non-financial metrics provide different points of view on a CEO’s performance.

This nonlinearity of course complicates the question of how one would arrive at a “net” assessment of a CEO’s legacy. How much weight should each ranking get? Should financial and non-financial criteria matter equally, or should they be weighted differently? More weight given to the financial or more to the non-financial?

We would argue that the truer measure of CEOs’ legacies is the amount of “public support” they helped to create for their companies during their tenures – the changes in people’s willingness to recommend, work for, buy products from, or invest in their companies. In fact, this is a measure that Reputation Institute regularly captures in its public surveys. And we have calculated the relative statistical contribution that financial and non-financial criteria make in predicting this index of public support. Our statistical analysis suggests that some 35% of a CEO’s legacy can be explained by financial performance, with the remaining 65% by non-financial criteria.

Thus, to assess these CEOs’ full legacies, we developed a combined ranking based on weighting the financial and non-financial performance rankings used in the scatterplot. Take a look at the table below. The second column in it is the original ranking released by HBR based on financial performance. The third column is the re-ranking of the same set based purely on reputations in non-financial (that is, “social”) performance areas. The first column is the ranking of CEOs that Reputation Institute arrives at by applying our weighted combination of the two. (And we’ve added a fourth column to highlight whose ranks change most.)

Now who rises to the top? CEOs one and two, as you can see in the overall rankings column, are Novo Nordisk’s CEO Lars Sorensen and American Tower’s CEO James Taiclet. Volkswagen’s Martin Winterkorn leaps up 68 slots to 21st thanks to favorable non-financial results. Disney’s Bob Iger also rises dramatically (from 60th to 10th) as do the CEOs of Fastenal, Alfa Laval, and Antofagasta. Starbucks’s Howard Schultz moves up from 54th to 14th place, reflecting a well-balanced commitment to governance, citizenship, workplace, and financial performance. Amazon’s Jeff Bezos drops only slightly from 1st place in HBR’s original ranking to a robust 3rd in the combined ranking.

Some CEOs see significant drops in ranking when we factor in the weak non-financial performance reputations of their companies. They include Japan’s Fast Retailing, and Taiwan’s MediaTek. Monsanto’s Hugh Grant suffers most heavily when ranked by this more holistic assessment of how his company has fared under his leadership. It drives down the assessment of his legacy from a lofty 8th to a more remote 82nd place in the adjusted ranking. Perhaps he has decided Monsanto must do more to boost its non-financial performance reputation; within the past few years, the company joined the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) and started offering Business Ecosystems Training globally to its employees.

The fact that financial performance and nonfinancial performance reputation do not correlate among HBR’s top 100 CEOs underscores why it is so important to keep refining our non-financial metrics and ensuring their rigor. And if both kinds of metrics are important to take the measure of a company, they may matter even more to assessments of a CEO’s tenure. The most holistic measure of a CEO’s contribution over his or her tenure would be a reliable answer to one question: How much better or worse is the overall reputation of the company compared to the day this leader stepped into the role? A great CEO’s legacy is never as one-dimensional as the ledger.

[image error]

The Biggest U.S. Health Care Challenges Are Management Challenges

Few health care leaders would disagree that the U.S. health care industry needs to drastically change. But do we have leaders in place who have the courage to raise their hand and lead the charge? In the classical theory of disruption, reform from within is almost impossible. It is hungry, fast-moving new entrants that upend slumbering incumbents. But at athenahealth, we’re seeing early signs of another possibility; more than any time in recent memory, provider groups themselves are preparing to do the disrupting.

Over the past two years, we’ve convened health care leaders at roundtables and other events to discuss the challenges and opportunities they face, both inside their organization and from the external market. As part of this process, we formally surveyed more than 150 executives; the sample represented a broad cross-section of health care, with respondents serving in leadership roles at organizations as diverse as physician practices, hospitalist staffing agencies and large health systems. What we found was a remarkable portrait of courage — a willingness to abandon the status quo in favor of an uncertain path.

In the survey more than 70% of participants reported that they felt their organization was well positioned for future success, with about 15% strongly agreeing with that sentiment. More than three-quarters said they are on a good path to successfully compete in their local markets. Fear of aggressive new competition is minimal, with only 3% of survey participants saying they feel very unprepared relative to their markets.

But this optimism is not a sign of complacency. More than half of the executives we surveyed believe their operational model is in need of change and disruption. At any other time or in any other industry, these results would seem contradictory. After all, we expect incumbents to feel most confident about the future when they believe their operating models are sustainable — and to fear extinction when disruption is on the march.

In healthcare, however, an instinct to disrupt existing models makes perfect sense. From every quarter, the industry is under pressure to cut costs and improve quality and the debate around the Affordable Care Act has crystallized the need for reform; many providers are leading the charge, moving further and faster to redesign care delivery than the law requires. Many health care leaders understand that there will be little room in the health care landscape of the next decade for laggards. These leaders may feel confident about their strategic direction, but they know their current models won’t get them where they need to go. Thus they need to become their own disruptors.

We asked our roundtable members where they hope to be in five years — and received an array of responses that all pointed toward disruption. One participant, the CEO of a staffing organization for hospital emergency departments, is looking beyond emergency care. “We hope to become a recognized leader in integrating physician care across transitions of care,” he told us — even though, ultimately, better care transitions will mean fewer E.D. admissions, which would threaten his existing business model.

The chief strategy officer of a west-coast medical center we surveyed is confronting a future in which her organization’s current strategy — top-quality tertiary and quaternary care — would be less competitive. “We need to position our enterprise for a post-reform era,” she told us, which means “moving from a tertiary/quaternary care model only to a dual strategy in which we are also a population health manager.” Rather than fearing the population health managers who would erode this organization’s high-margin business in complex surgeries, this strategy officer plans to join them — and reap the rewards of shifting from payment based on patient volume to payment based on delivering value.

Generally we found the respondents clear-eyed about the difficulty of changing course. One CEO of a large Midwestern health system reminded us that his system is already a Medicare ACO (Accountable Care Organization), and he and his colleagues are “positioned well in our thinking” about the future. But, he said, “we are not positioned well in some of our operating fundamentals such as infrastructure, analytics, process, and compensation models.”

The overwhelming sentiment among our roundtable participants was that the impediments to change are mostly internal. Less than a fifth of respondents said that market competition is the primary challenge they face in addressing the ongoing shift from volume-based to value-based payment. A similar share said that outdated or ineffective IT infrastructure is their major roadblock, and almost two-thirds identified either cultural resistance or misalignment with physicians as their biggest obstacle. One executive told us that his greatest challenge is persuading the “59-year-old physician who recognizes that things are changing but is hoping he or she can hang on.”

Overcoming such challenges requires intrepid leadership. Respondents to our survey said they are scanning widely for models of executives who have successfully disrupted their own organizations. When we asked which companies health care executives most admire, the top choice wasn’t Mayo, Cleveland Clinic, or any other blue chip health care institution. It was Apple: the tech giant with a history of cannibalizing its own products before a competitor does and promoting disruption before being overtaken by it.

[image error]

How to Protect Your Time Without Alienating Your Network

It’s a law of nature: the further you rise, the more people will make demands on your time. Some of those requests are self-interested: the informational interview, the job advice, the request for a connection, a recommendation letter, or angel funding. Others may be quite beneficial to you: the offer of a paid speaking engagement, or a prestigious media interview opportunity, or an invitation to an exclusive conference. The easy answer is to ignore all of these requests, deleting them as they come in — or even more extreme, declare some form of email bankruptcy. But, of course, that risks alienating some of your biggest advocates.

I feel genuine empathy for one top business thinker with whom I had a heart-to-heart at a conference a couple of years ago. She was overwhelmed and miserable with the amount of correspondence she received; it literally pained her. Her answer? She pretty much ignored everything including my follow-up requests to interview her for a (very well-read) publication and, later, to endorse my forthcoming book. I know she’s busy and I like her a lot, but total silence is not the mark of a friend, or even a passing-grade acquaintance. So how can you protect your time – and accomplish your more pressing priorities – without being a jerk to allies? Here are three strategies.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Getting the Right Work Done

Leadership & Managing People Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Scale your time. I’m fortunate that there are plenty of people who’d like to connect with me for meals or drinks or coffee: it’s a good problem to have. The downside, of course, is that I don’t have time for every request. Yesterday, I received an email from a Wharton School student who had attended a guest lecture I’d given there 18 months ago. Very politely, he thanked me for my talk, shared how he’d been implementing my suggestions, and then asked if I could “spend 20-30 minutes on the phone for a few points on how” he can best take advantage of a new opportunity. He sounds terrific and I’d like to help, but it’s just not feasible to do this for every student who requests it. Instead, I’m going to follow a tip that tech opinion leader Robert Scoble shared with me when I interviewed him for my forthcoming book, Stand Out. Instead of responding to emails one at a time, Scoble asks his interlocutors to post their questions on Quora, so that others can see and benefit from his responses. I won’t use Quora, but I’ll ask the student to email me his question, I’ll respond back electronically, and will later turn it into a blog post. Similarly, instead of one-on-one coffees, I’ll often organize dinners to bring together interesting groups of people who could also benefit from knowing one another.

Don’t overestimate your own importance. I’d been convening a series of such dinners in New York City for a number of months, bringing together authors to meet each other, make connections, talk about book marketing, and the like. When I realized a mutual friend knew one thinker I admired, I asked her to make an introduction, and invited him to our next gathering. In the past, I’d had prominent authors jump at the chance, excited to spend a night trading ideas with like-minded colleagues. But this potential guest was more skeptical. “I might have a conflict that night,” he wrote. “But can you let me know who’s going to be there and I’ll see if I can get around to it?” In other words: is there anyone important enough to be worth his time? I humored him with the list, and he agreed to attend — until the event was threatened by inclement weather. He wrote back eagerly: Is the event still on? Who’s still coming? Demanding a guest list is the equivalent of craning your neck at a cocktail party to see if someone more worthy of your attention has walked in the door. Of course it’s important to guard your time and be selective about which events you attend, but there has to be a baseline of trust and humility, especially when you’ve been introduced by a mutual contact. Make your best decision about whether to attend, and stick to it.

Make a choice about what to be bad at. Last year, I’d reached a point where I was feeling overwhelmed about my contacts. I knew I should be keeping in touch with people, but the volume had gotten so great, I didn’t know where to start. I signed up for a service called Contactually that helps track your interactions and sends you reminders when you’ve been out of touch with key people too long. A few weeks ago, they offered a free analysis of my email performance over the past year, looking for patterns and weak spots. Desperate for illumination, I had them run one … and got a D+, by far the worst grade I’ve ever received for anything besides handwriting. It was sad, true, and quantified before my eyes: I’m very pokey at responding to most emails. But I do have a policy: unless it’s a spammy message, I will respond eventually. It’s not perfect, but it’s a tradeoff I feel comfortable making thanks to Frances Frei and Anne Morriss’ excellent book Uncommon Service, in which they argue that in order to become truly great at something (such as a bank being open long hours), companies have to make an equally important choice about something to be bad at (such as offering unusually low interest rates on deposits). The same advice works for individuals. I’ve chosen to be bad at email response time because it’s less important to me than serving clients or creating new content like this article. But I’ll never let it get to the point where there’s no response. (My hero in this regard is Wharton professor Adam Grant, who hired an assistant just to help him respond to each and every message he got as the result of a popular New York Times Magazine profile. Though I make some use of virtual assistants, I’m now contemplating hiring someone fulltime.)

Managing your time is a constant balance — too loose, and you spin off in a million unproductive directions; too tight, and you eliminate serendipity and come off like a controlling primadonna. We all have to find the procedures that work for our lives and schedules, but it’s important to do it in a way that doesn’t needlessly alienate others.

[image error]

Everything You Need to Know About Becoming a Better Listener

“It can be stated, with practically no qualification,” Ralph G. Nichols and Leonard A. Stevens write in a 1957 HBR article, “That people in general do not know how to listen. They have ears that hear very well, but seldom have they acquired the necessary aural skills which would allow those ears to be used effectively for what is called listening.” In a study of thousands of students and hundreds of businesspeople, they found that most retained only half of what they heard — and this immediately after they’d heard it. Six months later, most people only retained 25%.

In this, I suspect the world has not changed much since 1957. So I dug into HBR’s archives for our best advice on the imperfectable art of listening. Here’s what I found.

It all starts with actually caring what other people have to say, argues Christine Riordan, Provost and professor of management at the University of Kentucky. Listening with empathy consists of three specific sets of behaviors. First, there’s the actual intake of information — recognizing the verbal and nonverbal cues the other person is emitting. Then there’s processing, which is where we make sense of what the other person is saying. Finally, there’s responding. This is where you validate what they’ve said — and note that validating doesn’t mean you have to agree with it — by nodding, playing back what you heard, or otherwise acknowledging that you’re picking up what they’re putting down.

To help you stay focused on the most salient points of what someone else is saying, take notes as you listen. Ram Charan offers a tip he saw work especially well for Larry Bossidy when he was CEO of Honeywell. Bossidy would draw a vertical line down the page of his notebook and write general notes to the left, while keeping track of the most valuable nuggets on the right. This helped train his brain to listen intently and zero in on what’s most important.

Recognize your defaults. Are you gregarious and outgoing — a real extrovert? Then you have many wonderful qualities, but listening well may not be one of them. It’s tough to listen when you’re the one who does most of the talking. Or are you super-conscientious, your smartphone always in hand and your calendar always uber-scheduled? Again … listening is hard when you’re distracted by a screen, or rushing to your next meeting. Knowing yourself is a key part of being a good listener (and one of just many good tips in Sara Stibitz’s piece).

Pay attention when your mind wanders to figure out what’s stopping you from listening. This piece of wisdom comes from Amy Jen Su and Muriel Maignan Wilkins, executive coaches and co-authors of Own the Room. When your attention flags, is it because you’re starting to plan your response to their comments? Or have you started listening to your own inner critic, instead of what they’re saying? But you can’t really listen fully at the same time you’re thinking about something else. When you notice something has blocked you from listening, simply make a note of it — don’t belabor it, or you’re just not-listening for even longer! — and shift your attention back to what the other person is saying.

Nichols and Stevens point out another factor that can stop us from listening: our own emotions. Feelings fog up a conversation. When you notice you’re having an emotional reaction, withhold evaluation and, with your judgment thus suspended, embark on a hunt for evidence that proves your own position wrong. “If we make up our minds to seek out the ideas that might prove us wrong, as well as those that might prove us right” – which human beings tend to do without making a conscious effort – “we are less in danger of missing what people have to say.”

When someone is upset or venting, a lot of us “listen” by sharing our own experiences (note: that is actually just talking). Or we try to fix the problem. (Note: that is also talking.) Or, perhaps because we’ve been told, “Don’t try to fix it, just listen!” so many times, we clam up and say nothing, which doesn’t result in the speaker really feeling heard. So the best way to listen when someone is venting is to ask questions, writes Mark Goulston, a psychiatrist and author of Just Listen. Help them get all that anger and frustration out into the open, where they can start to make sense of it on their own. Pose questions like, “What are you most angry about?” and “What are you really worried about?” They’ll feel heard, and you’ll get to the root of the problem.

As Nichols and Stevens point out, the basic problem with listening is that we can all think faster than we talk. The human mouth plods along at 125 words per minute, while a neuron can fire about 200 times a second. (This helps to illustrate why it’s crucial to slow down difficult conversations.) So give your brain something else to do while you listen: note the key points that are coming up in the conversation, actively look for nonverbal cues, ask yourself what the speaker might be intentionally not saying, or weigh the evidence being presented.

“The effectiveness of the spoken word hinges not so much on how people talk as on how they listen,” Nichols and Steven write. Many decades later, that’s still true. You can’t necessarily turn the people around you into better speakers. But we can all make ourselves better listeners.

[image error]

Pronouns Matter when Psyching Yourself Up

Some people seem to have an amazing ability to stay rational no matter what. They efficiently make good, clear decisions while the rest of us waste energy doing things like panicking about upcoming tasks, ruminating pointlessly, or refusing to move on from our failures. Those cool-headed rationalists also seem adept at getting ahead, while we’re mired in our all-too-human, biased habits of thinking. Could we ever become like them? The gulf between the two types of people seems vast and unbridgeable.

But it’s not. It can be crossed, via a simple linguistic shift.

“You.” Or “he.” Or “she.” Or even via your own name.

It’s a matter of how you talk when you silently talk to yourself, as you probably do often, especially when you’re confronted with a difficult task. Do you say something like “It’s up to me”? Or “I can do it”? Or do you say “It’s up to you” or address yourself by your own name?

Further Reading

Getting Work Done (20-Minute Manager Series)

Leadership & Managing People Book

12.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Nobel Prize–winner Malala Yousafzai demonstrated the use of the latter approach when she was asked by Jon Stewart how she felt upon finding out that she was on a Taliban hit list. She was fearful, but then she imagined how she’d respond if she was attacked: “I said, ‘If he comes, what would you do, Malala?’ … Then I would reply [to] myself, ‘Malala, just take a shoe and hit him.’”

Does this shift from “I” to “Malala” represent a simple quirk of speech? Or does it reflect something deeper — a process that helped her manage the intense threat that confronted her?

We, along with seven of our colleagues — Jiyoung Park, Aleah Burson, Adrienne Dougherty, Holly Shablack, and Ryan Bremner of the University of Michigan; Jason Moser of Michigan State; and Emma Bruehlman-Senecal of UC Berkeley — recently addressed this question in a series of experiments. We found that cueing people to reflect on intense emotional experiences using their names and non-first-person pronouns such as “you” or “he” or “she” consistently helped them control their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

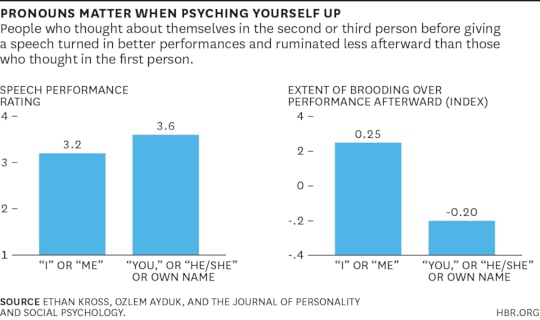

For example, in one study we found that participants who silently referred to themselves in the second or third person or used their own names while preparing for a five-minute speech were calmer and more confident and performed better on the task than those who referred to themselves using “I” or “me.”

The effects extended beyond the task, too: People who had used non-first-person pronouns or their names felt more positively about their performance on the speech once it was over. They also experienced less shame about it and ruminated about it less. Those are big pluses — ruminating endlessly over past experiences can hurt not only your psychological well-being but also your physical health.

It didn’t matter whether the research subjects were anxious or calm at baseline; both types of people benefited from the subtle shift in language.

Nor were there different effects for use of the second- or third-person pronouns or their own names. All that mattered was whether the participants did or didn’t use first-person pronouns.

It was impressive to see how a simple change in language could produce these effects. Having observed the power of this subtle shift, both of us now intentionally make use of it. One of us (Ozlem Ayduk) has even been known, when facing a difficult task, to write herself emails using her name. The other (Ethan Kross) regularly prompts his five-year-old daughter to use her own name in thinking about why she feels distressed when she doesn’t get her way.

Our findings are just a small part of a much larger, ongoing stream of research on self-talk, which is proving to have far-reaching implications for altering the way people think, feel, and behave. Not only does non-first-person self-talk help people perform better under stress and help them get control of their emotions, it also helps them reason more wisely.

Our past research indicates that a self-distancing effect can be achieved by cueing people to mentally adopt a “fly on the wall” perspective on their problems. Shifting visual perspective like that may work in situations where people have the time to reflect on experiences that have already occurred. What’s exciting about the self-talk effects we found is that they lend themselves to real-time situations that are unfolding quickly. When you’re in the midst of performing a task or interacting with others, the substitution of “you” for “I” can be done quickly and easily, and the results may surprise you.

[image error]

February 5, 2015

Managing Privacy in the Internet of Things

Photo by Andrew Nguyen

One of the promises of the Internet of Things (IoT) is that everything should talk to everything else. These talkative “things” include sensors, consumer appliances, home automation systems, and even connected vehicles. The frameworks through which such interconnectivity is arranged, controlled, and mediated – that is, how these things “entitle” each other to connect – is going to be a fundamental part of IoT. Managing this “entitlement,” which defines who can access your device data, and under what conditions it can be found and used by others, will be one of the major challenges for consumers and businesses.

The data from all these things will be valuable not just to the companies that deploy them, but also to people or companies operating in other domains. For example, your thermostat might talk to your neighbor’s weather station to determine an appropriate temperature setting, and then switch on the heating when your phone’s GPS tells it that you’re nearing home.

It’s this many-to-many and cross-domain aspect of connectivity that distinguishes IoT from earlier remote monitoring/control systems and M2M (machine-to-machine) systems, where only one organization created, owned, and used the data. In the IoT, each connection won’t be predetermined; these things should be able to structure their conversations on the fly, in an automated and ad-hoc manner. But this raises a number of questions and concerns around privacy, interoperability, and data-access privileges.

First, how do all these things automatically find each other? In the web world, discoverability (the ability to be found quickly) has been key to growth, but this isn’t necessarily the case in IoT, where many private things will not want to be found. Having a heart monitor at a home can be useful to your doctor, but you wouldn’t want an unknown company to be able to access that data. Knowing you have a heart monitor, a blood pressure monitor, and a dialysis machine could lead to unwanted targeted advertising. Things must define how, when, and by whom they are found.

Once they’ve found each other, how do they “speak” to one another? This has led to a focus on “interoperability,” which is getting things to talk in a common language. Yet even human beings have been unable to converge on a single language to share information. And where we are speaking the same language, we have different ways of describing the world. Some of us use Celsius and others use Fahrenheit. The same is true for our “things”: they are used in a variety of contexts. There may even be a disincentive to adopt a common protocol, data format, or parameter, since that can restrict inventiveness.

Then what happens when the data from one thing is used by another out of context? Imagine a thermostat making a decision based on a nearby temperature sensor, even though that’s measuring the temperature of a baby, not the room temperature. Developers of sensors can’t pre-define all the potential contexts in which their devices will be used. So how might their owners help refine or restrict the conditions in which data is employed?

Most importantly, how do people control which things can access the data generated by their things? People have different comfort levels when it comes to making their data available to others. One person might be happy to make his real-time energy usage profile available to an energy supplier, because that supplier offers competitive rates or services; but another person might not want to release that information. Real-time energy usage data can provide intimate information, including behaviour patterns – i.e., when people are present and active in their homes.

People are also nervous about how their things report contextual and geolocation information (where the things are and what is near them) — especially in the wake of revelations about how the NSA in the U.S. has used such metadata. Some might be happy to let others to see their real-time geolocation (if they’re using a mobile app that helps friends find each other in crowded locations), but others will want to keep it private.

On the web, we have largely ignored these issues. The data that we’ve grown used to making public has seemed innocuous. So people don’t protest too much when their personal profile or usage data is employed by companies like Facebook and Google to deliver highly targeted advertisements. But in the Internet of Things, the data generated by all these things tends to be much more personal and commercially sensitive; and the way it’s consumed (via non-screen devices) means that an advertising model isn’t necessarily going to be sustainable. These challenges don’t mean that IoT is impossible, they just mean that it will be complex — technically, socially, and economically.

[image error]

What to Do When Your Colleague Comes Out as Transgender

By now, many professionals have openly gay colleagues at work, including the 66,000 U.S. employees of Apple, whose CEO, Tim Cook, famously became the first Fortune 500 CEO to come out last October. But far fewer people have had the experience of working with an openly transgender colleague (i.e., someone “whose gender identity or expression is different from those typically associated with the sex assigned to them at birth,” according to advocacy group the Human Rights Campaign).

Partly that’s a matter of numbers. UCLA’s Williams Institute estimates that there are 700,000 transgender Americans – a significant number, but much smaller than the 8 million gays, lesbians, and bisexuals living in the U.S., according to surveys. And partly it may be a result of fear. In 32 states, it’s possible to fire someone for being transgender, and a 2011 survey revealed that 47% of transgender respondents had experienced a “negative job outcome – such as being fired, not hired, or denied promotion” because of their gender identity or expression.

Further Reading

Managing Your Professional Identity During a Gender Change

Gender Article

Dorie Clark

How to tell the world about your transition.

Save

Share

Your company needs to tap the best talent possible, and research has shown that workers perform better when they’re comfortable being out at work rather than constantly worrying about “covering” their identity. Here’s how you can make your company, department, and team a more welcoming place for colleagues who have – or might in the future – come out as transgender.

Unless you’re already good friends, keep your reactions to a minimum. Someone who comes out to you as transgender certainly hopes for a positive response – but also doesn’t want coming out to be a huge deal. Treat the person as you always have, and go for understatement. “I always appreciate it when all I get is a nod,” says nonprofit consultant Robbie Samuels. “Like, thank you for sharing that – noted. I’m not looking for a big reaction or to focus the conversation on me and my gender.” If you’re pals with your newly out colleague, however, you can get a little more creative. Advertising copywriter Chris Edwards, who is writing a memoir about his transition experience, recalls a note – actually a Bar Mitzvah card – one colleague left on his desk. “On the cover it said, ‘Congratulations. Today you are a man.’ It was perfect. I still have it.” Supportive humor can be great – but only try it if you’re already close to your colleague. Perhaps the best response of all was one received by Jessica Mink, a noted astronomer. She recalls, “My boss’s boss…said that he hoped [my coming out] didn’t mean I was going to leave, and told me how valuable my work was.”

Take your cues from your colleague. Some of your transgender colleagues may be pleased to discuss their own experiences or trans issues in general, while others may be more reticent. Follow their lead. Mink is open to discussing trans issues but often first points colleagues to a blog post she wrote – “On Being a Transgender Astronomer” – that provides an overview of her experience. Edwards notes, “If you’ve never really spoken to them before, to start now by asking personal questions probably isn’t the best idea.” But he’s a fan of breaking the ice where appropriate. “One time I was walking past the AV suite and the editor was showing her intern how to hook up the equipment. Just as I approached, she held up an adaptor and said, ‘This is a female to male,’ so I popped my head in the door and said, ‘Hey, stop talking about me!’ I could hear them laughing all the way down the hall. You can bet they told that story to others, which helped people know I had a sense of humor about it and that they could talk to me without fear they were invading my privacy. I encouraged questions and said, ‘If you ask me something that crosses the line, I’ll tell you.’ It worked pretty well.”

Be mindful of the pronouns. No one is going to expect you to become an instant expert on transgender issues. But there are two things you really, absolutely have to get right: the person’s chosen name and preferred pronoun. Just as it might be offensive if someone consistently called you by the wrong name or kept calling you “she” when you’re a “he,” the same is true for your transgender colleague. An occasional mistake is no big deal – just correct yourself and move on. (Profusely apologizing and calling attention to the mistake only makes it worse.) But repeatedly using the wrong name or pronoun for your colleague looks less like an honest error and more like malice – so make sure to get this one right.

Relax about the bathroom. Bathrooms were a source of great sturm und drang during the debate about gays in the military, and they may be so even more when it comes to transgender issues. As some courts have ruled, transgender employees should use the restroom that matches their gender identity, even if there’s a period during their transitions where they might not “look like” they fit in. While that may make some traditionally-gendered employees uncomfortable, it’s the transgender employee that’s at infinitely greater risk for insult or physical harm, so it’s important not to blow the issue out of proportion.

Do research on your own. You may be tempted to pepper your colleague with questions about transgender issues, and on one hand, that’s a laudable impulse. On the other, lots of people are probably doing the same thing, and having to answer the same question 30 times stops being interesting or productive. Don’t treat your colleague as your personal Google; you can read about transgender issues yourself and learn a great deal. “Make the effort to educate yourself so you can be a better ally,” advises Samuels. In particular, many transgender advocates recommend the in-depth site operated by the Human Rights Campaign and books such as Nicholas Teich’s Transgender 101 and Joanne Herman’s Transgender Explained For Those Who Are Not. Memoirs like Jennifer Finney Boylan’s She’s Not There: A Life in Two Genders may also be helpful.

You may – or may not – work with with a colleague who comes out as transgender. But to tap the true potential of your workforce, you have to ensure everyone feels comfortable being themselves. These strategies can help make that a reality.

[image error]

Get More Done by Focusing Less on Work

Photo by Andrew Nguyen

When people want to get more done at work, they double down on the time they put into their jobs. They adopt a new productivity approach, stay at the office late, work weekends, revamp to-do lists, and try to cram more into every day. But what if the secret to performing better at work, and feeling more satisfied, isn’t to put more effort and energy into work but less? Instead of working harder and longer, what if you better integrated the four domains of your life – work, home, community, and self? My research has shown just that: By focusing more on the areas of life you care most about, even if those aren’t work, you’ll perform better at your job.

In July 2013, I wrote a piece and launched an assessment on HBR.org meant to help readers take a clear view of what they want from — and can contribute to — each domain of their lives. My advice to people was to carefully consider the people who matter most to them and the expectations they have of one another. I then suggested that they experiment with small changes to see how those tweaks affected all four domains over a short period of time — what I call “four-way wins.” I gave practical guidance derived from my book on how to conduct the experiment. (See this article for more on designing four-way win experiments.)

But — as I’ve seen in thousands of cases from years of field research, teaching, and practice — there are serious barriers to this type of integration, and even to trying small experiments. Those barriers are fear, ignorance, and guilt. People are afraid of change, don’t know how to go about it, and feel guilty even trying because they worry it will negatively impact others. If you can learn to minimize these barriers, you make it far more likely that you will try something new and successfully experiment, thereby getting more done and creating greater harmony in your life. Here’s how:

Lower risk by scaling the intended new action down so it’s manageable, and less frightening. Let’s say the experiment is to shut down your digital stream periodically so you can focus on people at home and in your community. Instead of setting the goal for three hours of detox every day, try three hours per week.

Gather information about what might and might not work by sharing ideas for action with stakeholders who’ll be affected. For example, let your boss know that for the next month, you’re going to try shutting down for three hours per week — and which specific hours you plan to do so. Explain to her how you believe this will benefit her and ask her what her concerns might be. If need be, adjust your plan so she sees it as a win for her, as well. Ideally, she’ll then want you to do this more often.

Deliberately assess the positive impact you expect your actions to have not just on you personally, but on the people who depend on you at work, at home, and in the community — reducing any sense of selfishness you might feel because you’re doing it for them and for you. With your boss, for example, agree on a metric (e.g., your attentiveness to co-workers or your level of crankiness) that assesses an aspect of your performance that matters to you both. Then, figure out a simple way to collect data on this metric so you can quickly capture the results of your experiment and inform any further adjustments.

It might seem counterintuitive that you will perform better at work if you spend more time with your kids, leave work early to volunteer at a local nonprofit, or take an hour out of your workday to go to the gym. But that’s just what happens.

You and Your Team

Getting More Work Done

How to be more productive at work.

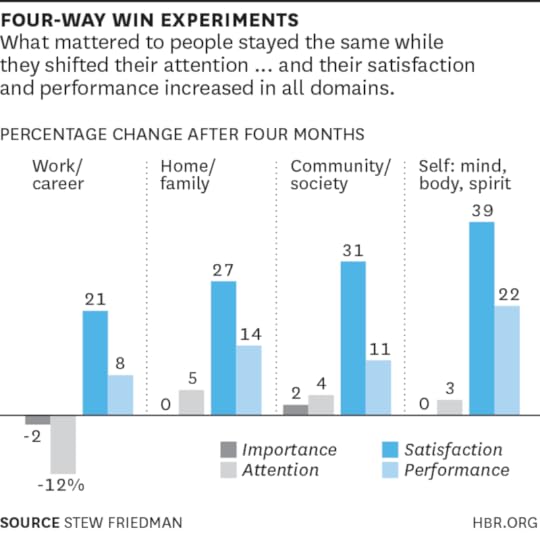

My research team observed in a 2005 study of 300 business professionals a paradoxical result (reported in my book Total Leadership): when you undertake smart experiments with the intent of better aligning your actions and your values in a way that’s consciously designed to benefit yourself, your work, your family, and your community, you are likely to spend less attention on work while experiencing enhanced well-being and better performance (as assessed by others) in all domains. Consider the following chart:

As the chart illustrates, we found that what’s important to individuals didn’t change much over the course of the four months of the experiments we studied. People still rated each domain with the same level of importance. But participants shifted their focus of attention to better match what they cared about — that is, generally away from work to other domains — family, community, and self (mind, body, spirit). At the same time, their satisfaction in every domain increased, particularly in self. It’s easiest to make gains in this domain because it’s (usually) rated lowest to begin with, so there’s nowhere to go but up. Further, the positive spillover from better experiences in the other parts of your life has an especially good effect on your mind, body, and spirit. And not only did people’s sense of well-being improve across the board, their ability to meet performance expectations — as reported to them on a standard scale by key stakeholders — went up in all domains, too.

But, how can performance at work improve with less attention paid to it? There are several reasons:

Clearer focus on results that really matter to the people around you.

Less wasted effort on activities that aren’t that important.

Reduced psychological interference across domains as a result of being less distracted, because you’re taking care of critical needs in those other parts.

A virtuous cycle of benefits from one part of your life spilling over to other parts; for example, greater confidence, less crankiness, and a stronger sense of control.

Barriers to creating meaningful changes in where you focus your attention — your most precious resource — are real, and there are ways to surmount them. Take action that’s within your control and that you believe will benefit the people who matter most to you in all the different parts of your life, gather data on your impact, and continually adjust so you’re increasingly able to do what’s good for you and for them. Your mindset will shift as you start to see more opportunities for realistic four-way wins. You just have to look for them, as a leader, in all parts of your life, by doing the basics: Envision a better future and bring others along with you.

[image error]

Closing the Gap Between Blue Ocean Strategy and Execution

At the highest level, there are three propositions essential to the success of strategy: the value proposition, the profit proposition, and the people proposition. For any strategy to be successful and sustainable, an organization must develop an offering that attracts buyers; it must create a business model that enables the company to make money out of its offering; and it must motivate the people working for or with the company to execute the strategy. While good strategy content is based on a compelling value proposition for buyers with a robust profit proposition for the organization, sustainable strategy execution is based largely on a motivating-people proposition. Motivating people requires more than overcoming organizational hurdles and winning people’s trust with fair process. It also rests on aligned and fair incentives.

In this sense, the three strategy propositions provide an organizing framework to ensure an organization is taking a holistic approach to the formulation and execution of strategy. The three strategy propositions correspond to the traditional activity system of an organization. As the ultimate outputs of an organization’s activities are value for the buyer and revenue for itself and its inputs are the costs to produce them and the people to deliver them, the three strategy propositions of buyer value, profit (revenue minus costs), and people capture the essence of what an organization’s activity system does. Unlike marketing, manufacturing, human resources, and other functions, a good strategy should cover the entire activity system of an organization. A marketing department, for example, may focus on the value proposition and pay insufficient heed to the other two propositions. Similarly, a manufacturing department may neglect buyer needs or may treat people as a cost variable. This is why a sustainable blue ocean strategy requires a fully developed and consistent set of three propositions. If a strategy does not fully develop and align the three strategy propositions, short-lived success or failure typically results. This is a trap many companies fall into. Lacking a holistic understanding of strategy, it is easy for an organization to focus overridingly on one or two strategy propositions to the exclusion of the other(s). For example, think of an organization that zealously focuses on getting the value or profit proposition right, but pays little heed to getting the people proposition aligned. Corporate graveyards are filled with such examples. This is a classic case of execution failure. Likewise, good strategy execution via a motivating-people proposition with poor strategy content as reflected in the value or profit proposition is also a path to poor performance.

In some situations, there may be more than one group of stakeholders that a strategy proposition must address. For example, if successful strategy execution rests on the buy-in of only employees, there is only a need for one people proposition. But when a company needs the support of a supply chain partner, for example, it must also give the potential partner a compelling reason to back the strategy. In that case, a company would be required to have a distinct people proposition for both employees and the supply chain partner. Similarly, in a business-to-business environment, there might have to be two value propositions: one for the business customer and another for the business customer’s customers.

Strategic alignment is the responsibility of an organization’s top executives versus those in charge of marketing, manufacturing, human resources, or other functions. Executives with a strong functional bias typically cannot successfully fulfill this important role because they tend to focus on a part, not the whole, of the three strategy propositions, hence missing the alignment. A manufacturing department, for example, might neglect buyer needs or treat people as a cost variable. Similarly, a marketing department might focus on the value proposition and pay insufficient heed to the other two propositions. However, when the three disparate strategy propositions that cut across an organization are fully developed and aligned, a high-performing and sustainable strategy is achieved.

Creating a full set of consistent strategy propositions is, of course, essential, whether a firm follows blue ocean or red ocean strategy. Where the two approaches really diverge is how organizations achieve alignment around the strategy propositions. Under red ocean strategy, an organization’s three strategy propositions need to be aligned with the distinctive choice of pursuing either differentiation or low cost within given industry conditions. Here, differentiation and low cost represent alternative strategic positions in an industry.

In contrast, under blue ocean strategy, an organization achieves high performance when all three strategy propositions pursue both differentiation and low cost. It is this alignment in support of differentiation and low cost that ensures a successful blue ocean strategy that has sustainability. While one or two strategy propositions can be imitated, imitating all three is difficult, especially the people proposition because it is embedded in human relationships that take time to cultivate. When external stakeholders are involved and important, getting the people proposition right takes even more time and effort for potential imitators, hence typically prolonging the aligned strategy’s sustainability.

Achieving Blue Ocean Strategic Alignment

To understand how an organization achieves alignment to produce a high-performing and sustainable blue ocean strategy, let’s look at Comic Relief, a UK fund-raising charity. Founded in 1985, Comic Relief leapfrogged existing UK fund-raising charities and emerged as one of the most distinctive charities in the UK that also enjoys the lowest costs. In an overcrowded industry that suffered rising costs, declining demand, and a public confused by the sheer number of fund-raising charities, Comic Relief rapidly achieved 96 percent national brand awareness and has raised over £950 million by inspiring everyone from traditional wealthy donors to previous nondonors to give. What’s more, while UK charities get, on average, only 45 percent of their funds from the public—the rest coming from government grants and corporations—Comic Relief has raised 100 percent of its donations directly from the public and has done so with no paid marketing or mail solicitations. Now, nearly thirty years on, there are still no credible imitators in the blue ocean it created. Let’s see how it has achieved this sustained high performance through alignment.

In the case of Comic Relief, customers are donors whom it needs to attract with a compelling value proposition. Its profit proposition is about the business model it built to maximize its “profit,” which for Comic Relief is its revenue surplus over costs that can ultimately flow to charities. And its people proposition is about the positive incentives and motivations put in place for its employees and network of volunteer fund-raisers, corporate partners, and celebrities.

Consider the differences between Comic Relief and other UK charities’ value, profit, and people propositions. As we go through these, you will see that when the three strategy propositions are aligned around differentiation and low cost, key factors from one proposition often support and reinforce the other two propositions, creating a strong, positive cycle. For example, organizations can leverage a compelling value proposition to strengthen its profit and people propositions or build on a powerful people proposition to create a strong value proposition, which in turn strengthens the profit proposition, which makes imitation that much more difficult. Here’s how Comic Relief’s value, profit, and people propositions work.

The Value Proposition

Traditional fund-raising charities in the UK use sad or shocking images in their campaigns, stimulating negative feelings of guilt and pity to trigger donations. Their focus is on securing and recognizing large gifts mainly from high-income, educated, older donors through year-round campaigns and solicitations of funds.

Comic Relief, in contrast, has eliminated pity and guilt. It uses a breakthrough new fund-raising approach, Red Nose Day, a double-whammy combination of a national day of whacky, community “fun”draising when people volunteer to perform zany antics to raise money, and a star-studded comedy telethon, Red Nose Night. Forget pity. It’s all about doing something funny for money to change the world.

With Comic Relief, donors don’t need to write a big check. Taking part is cheap, easy, and fun. People can contribute by buying a little plastic red nose that costs a £1, is sold everywhere, and can’t help but make you smile. Over 66 million have been purchased so far; everyone wears them. Or you can donate by sponsoring the silly antics of friends, family, neighbors, or colleagues, thereby giving money while having a great laugh. For example, friends and colleagues sponsored a London travel agent with a reputation as a chatterbox to stay silent for twenty-four hours; they collectively donated over £500 in sponsorship while having a blast watching the chatterbox struggle to stay silent.

Comic Relief’s unique use of community fund-raising not only leverages people’s fondness to have fun. It’s also personal. It is not some unknown person asking for donations as at most other charities. Rather it’s a friend, loved one, or colleague who you care about and want to support.

Unlike traditional charities, Comic Relief values and recognizes even the tiniest donation, for example, when Red Nose Night explains that the generous donation of one little girl, who gave “all her pocket money” of £1.90, will feed seven children in Africa. People know their every cent counts and makes a difference. This opens the door for even the poorest and youngest person to realize that even he can make a major contribution and become part of a greater cause of personally contributing to “changing the world.”

While traditional charities solicit funds from a regular base of supporters year-round and every year, Comic Relief focuses on creating this unique experience once every two years to avoid boredom and nagging. Instead of feeling donor fatigue, as with other charities’ continuous solicitations, people actually look forward to the excitement of the next Red Nose Day, which has nearly become a national holiday in the UK.

Lastly, Comic Relief donates 100 percent of all funds raised with its golden pound promise that it spends none of the funds on its own overhead or operating costs, as the average UK charity does. This transparency is reassuring to people who often wonder what percent of funds actually makes its way to charity. The result is a value proposition that not only is fun, exciting, and clear but also allows donors to make a huge difference with a small donation. In other words, it is differentiated and low cost, affordable to everyone from the very young to the very old and from low to high income.

The Profit Proposition

How does Comic Relief raise such extraordinary sums and support its operations while maintaining the golden pound promise? It has done so by complementing its compelling value proposition with an unbeatable profit proposition that simultaneously achieves a low-cost structure while generating funds in a differentiated way.

Traditional charities use a variety of methods to raise funds from several sources such as writing grant proposals to governments, trusts, and foundations; holding fund-raising galas for wealthy influential people and corporations; directly soliciting via mail and telemarketing; and operating charity shops. Almost all these activities entail significant overhead costs in staff, management, and administration as well as the possible renting or purchase of facilities.

Comic Relief, by contrast, eliminated all of these. It doesn’t plow time and money into expensive fund-raising galas, it doesn’t write grants to solicit funds from governments and foundations, and it doesn’t have charity shops. Instead it leverages existing high street retail outlets from supermarkets to fashion stores to sell its little red noses. And because Comic Relief makes grants to other charities, rather than introducing competing programs into an already crowded market, the costs of administering the funds it raises are cut dramatically. By some estimates, Comic Relief has stripped away more than 75 percent of traditional fund-raising operations.

Comic Relief can afford to keep costs low due to the unique way it raises money. What Comic Relief understood is that with community “fun”draising, it is no longer the charity pushing the donor to make a contribution, but the cause pulling the donor in. And with people volunteering to do the bulk of fund-raising by engaging in silly antics that others sponsor, Comic Relief’s staff costs stay very low. Whereas traditional charities’ use of community fund-raising is completely accidental and infrequent, through Red Nose Day, Comic Relief focuses on community fund-raising, making it the systematic, dominant channel through which to get contributions.

While traditional fund-raising charities tend to focus on wealthy older donors, Red Nose Day is all about targeting the mass and raising funds via lots of small increments. On Red Nose Day, ordinary people do extraordinary things and raise huge amounts of money, from a large number of small contributions.

What’s more Red Nose Night—the star-studded comedy extravaganza that makes people laugh to raise money for charity—doesn’t cost a penny. Everyone gives his or her services for free (the network, the studios, the stars). Unlike traditional charities that engage in costly marketing to stand out in the overcrowded industry, Comic Relief avoids large advertising costs, thanks to the widespread media attention and free word-of-mouth advertising that all the excitement of Red Nose Day generates.

To help Comic Relief realize its golden pound promise, corporate partners cover its operating costs in cash or in kind. The overall result is that Comic Relief has not only a compelling value proposition, but a differentiated, low-cost profit proposition.

The People Proposition

At Comic Relief, all the people involved win, not just those they help. With a small number of motivated staff members who are inspired by its value proposition, Comic Relief’s people proposition focuses on inspiring volunteer fund-raisers, corporate sponsors, and celebrities whose buy-in is needed to make the value and profit propositions sustainable.

Excerpted from

Blue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant

Competition Book

W. Chan KimRenee Mauborgne

32.00

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Toward this end, Comic Relief begins by creating a legitimate platform, Red Nose Day, for everyone to go a bit mad and have an outrageous time volunteering in order to raise money. Next, Comic Relief makes participating easy: its website offers all sorts of zany ideas to fire up your imagination for funny antics and tips on how to get people you know to easily sponsor you. By taking part and becoming an actor in fund-raising, people earn the respect of friends, family, and colleagues, while feeling a sense of pride that they are visibly part of a group working to better the world.

By offering people the opportunity to be actively involved in raising money through silly antics, not only are people having fun, but they become part of a greater cause of personally contributing to bettering the world. With Comic Relief, volunteers are the actors in fund-raising and part of a large one-day event where everyone is doing his or her share to positively change the world while having a great time.

All of this is achieved while conserving volunteers’ most valuable resource, time; participating in Comic Relief doesn’t take a lot as you only have to do something silly every other year. In this way, Comic Relief creates a compelling, low-cost people proposition that inspires people across the nation to volunteer and fund-raise on behalf of Comic Relief. Contrast this with traditional charities where volunteering can be a drag and people often silently feel they are sacrificing to help out.

Comic Relief’s low-cost and differentiated people proposition extends to corporations and celebrities as well. Only in this case, in addition to the benefits that ordinary citizens get for volunteering, sponsoring corporations and participating celebrities get tremendous free publicity across the UK. That’s because Comic Relief’s differentiated, low-cost value proposition triggers enormous free press, including over two hundred hours of TV time, hundreds of hours of radio coverage, and over ten thousand press articles. The result is that Comic Relief does not have to beg corporate sponsors or celebrities to take part. Instead it has corporate sponsors and celebrities eager to volunteer to help it realize its golden pound promise of giving 100 percent of donations to great causes, creating a win all around. As the Comic Relief case illustrates, the aligned value, profit, and people propositions around differentiation and low cost create powerful, reinforcing synergies and a win-win for all.

To produce a high-performing and sustainable blue ocean strategy, you need to ask the following questions. Are your three strategy propositions aligned in pursuit of differentiation and low cost? Have you identified all the key stakeholders, including external ones on which the effective execution of your blue ocean strategy will depend? Have you developed compelling people propositions for each of these to ensure they are motivated and behind the execution of your new idea? Do you have a holistic understanding of strategy? Has your new strategy fully developed and aligned the three strategy propositions for sustained success? The continuing success of your company’s strategy depends on it.

This article is adapted from the Harvard Business Review Press book Blue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant (2015).

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers