Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1300

April 16, 2015

“Office Housework” Gets in Women’s Way

More often than not, women are the ones who help others when asked — they plan the meetings, take the notes, and take on other types of “office housework,” in Rosabeth Moss Kanter’s immortal phrase. These thankless-but-necessary tasks keep organizations humming. But as Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg and Wharton professor Adam Grant noted in a New York Times article, while women are expected to do more of this work, they don’t get credit for it and suffer backlash when they refuse to do it. “When a woman declines to help a colleague, people like her less and her career suffers,” they wrote, citing different studies by professors Madeline Heilman, Joan C. Williams, and Joyce K. Fletcher, “But when a man says no, he faces no backlash. A man who doesn’t help is ‘busy’; a woman is ‘selfish.’”

Office “housework” is often invisible and so its value to a team is under-appreciated. That fact creates one of the hidden barriers that can keep women from ascending to more senior leadership roles. In our decades studying this phenomenon, we’ve found four negotiation strategies that work.

Turn a request for help into a negotiation. Alexandra, a project manager, was asked by her boss to support a leader who has having family issues and needed help doing his work. Her boss asked to be an “acting director.” Alexandra negotiated this request into a promotion: she agreed to help, provided she would be named to a “director” role after the helping period ended and the leader returned to his job.

Ascertain the cost of your contribution. Helping is not a free good. Not only does it take time away from your day job but it can exact a toll on your health and family. When Patria, a program leader in an NGO, was asked by her director to help a colleague whose team was having trouble managing its workload, she agreed. But when she factored in the additional time required to help her colleague, her pro-rated hourly pay dropped dramatically. When she pointed this out to the director in stark dollar terms, Patria was able to negotiate for more resources in order to continue to help without putting in more time.

Demonstrate the value of your help. In our work, we have seen how women successfully incorporate their helping work into an expanded version of their jobs by showing the value of the work. That is what Isobel, a communications manager, did. After initially helping another division with a government client and saving an important relationship, the other division kept asking for her “fixing” help. Although she liked being seen as a “fixer,” she knew she could not continue and still keep up with her job. By showing the value of her work to the other division, she negotiated the “fixing” work she was doing into a new expanded role, with a commensurate title and raise.

If the ask is more personal than professional, build in reciprocity. In the examples above, helping benefited the organization. But getting the coffee and planning the office party are more personal. When negotiating these types of requests, ask for reciprocity—if I do this, then what will you do? Allison, a senior leader, was always willing to take her turn getting the coffee –with the proviso, “I’ll do it today and next time it will be your turn.” And she made sure the other person remembered.

Negotiating the conditions of your help is good for you as an individual and good for your organization. When you help without conditions, you train people to expect that you will continue to do so. But when you negotiate the conditions of your help, it can be a small win for you. And as we have found in our work, these small wins can start to accumulate into bigger gains. Sandberg and Grant note it doesn’t have to be the case that “no good deed goes unpunished.” But reversing that behavior requires women to place value on their help and to negotiate to have that work acknowledged and rewarded.

CEOs Don’t Care Enough About Capital Allocation

In his 1987 letter to investors, Warren Buffet made the following observation: “the heads of many companies are not skilled in capital allocation, and … it is not surprising because most bosses rise to the top because they have excelled in an area such as marketing, production, engineering, administration or, sometimes, institutional politics.”

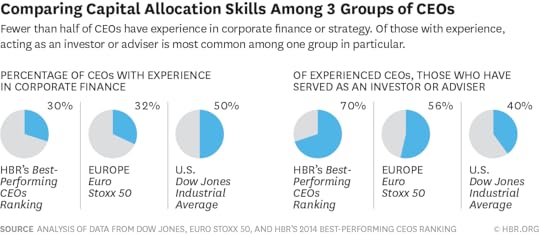

A quarter century later, not much seems to have changed: fewer than five out of the 100 CEOs on HBR’s 2014 list of best-performing CEOs even mention “return on capital” on their official biography — and none of those five lead companies listed in the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) or in the EuroStoxx50.

This failure to even mention return on capital seems perverse. It’s been more than 50 years since Nobel prizewinners Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller identified return on investments as a major component of value creation (and value destruction). It is, in fact, the salt in the value recipe. Unless your company’s return on capital exceeds its cost of capital, no amount of revenue growth can create value.

For the many firms whose cost of capital and return on capital are roughly equal, in fact, the only path to value creation is to increase return on capital. The results can be impressive: if your firm’s return on invested capital is 8% and you have an 8% cost of capital, a 1% improvement in ROIC will increase firm value by 19%. And at a time when growth opportunities are limited, it is arguably the only way to create value.

There are just two ways to increase ROIC: improve operating profit (by increasing revenues or cutting costs) or invest capital more wisely. The revenue and cost path is, however, well trodden in a low-growth economy and evidence suggests that the real leverage comes from making smarter investment decisions.

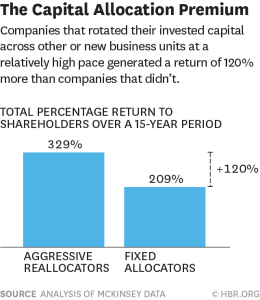

A 2012 McKinsey Report shows that over a 15 year period companies that shifted more than 56% of their capital across their business units during that period delivered annual return to shareholders that were a third higher than those delivered by companies that allocated roughly the same amount of capital per unit as they had the previous year. The results are shown in exhibit 1. Another study by private equity investor William Thorndike shows that this aggressive group outperformed the S&P 500 by over twenty times.

This, of course, raises an obvious question: Why are so few CEOs skilled at capital allocation?

Looking at the resumes of current CEOs across developed markets suggests that the answer may be that many lack training in the skills of investment analysis. As the chart below shows, only half of the CEOs of companies in the Dow Jones Index have previous experience in corporate finance or strategy. It’s worse in Europe, where the proportion falls to just 32% of CEOs of EuroStoxx50 companies.

Tellingly, another recent (2013) McKinsey study covering a 20-year period revealed that only 16% of board members understood how their firms created value.

Those of us in private equity (and our counterparts in active investment funds) are well aware of this skills gap. We know that we need a CEO for the management of current business operations in the companies we own, but we also know that we are generally better at allocating the excess cash generated from operations or from external fund providers. The generally superior returns that the top private equity funds deliver are almost entirely explained by their decisions on what to do with the investment capital available to the firms they own.

The bottom line? Boards that are serious about value creation need to look more carefully at the track records of the CEO candidates they’re recruiting. They might even think about recruiting executives with some experience in private equity — which few CEOs of companies in the Dow Jones Index or the EuroStoxx 50 can claim to have.

10 Tactics for Launching a Product Using Social Media

I’ve witnessed a seismic shift in the way new products are launched over the past decade. As the founder of a firm that helps launch products, services, businesses, and communities, I’ve watched the days of an embargoed launch date and a single exclusive media story disappear. The Internet has changed the launch process—now companies seed products with influencers, leak information to reporters, bloggers, and consumers, live-stream launch events globally, and reward brand advocates with exclusives. The insatiable 24/7 news cycle and the dominance of social media makes launching a new product far easier in some ways—and more difficult in others.

The new launch landscape levels the playing field for brands of all sizes and industries when reaching consumers–yet the ability for consumers to share their opinions freely on social media can provide huge hurdles for brand messaging. Consumers can quickly activate other like-minded consumers to rev up the online discussion to a level anywhere from highly positive to tanking a brand.

When it comes to choosing media to support a new product launch, consider the target market. Schneider Associates 2014 Most Memorable New Product Launch survey found that each generation uses a unique media mix. Seniors, Boomers and GenXers still like to curl up with a magazine. Millennials are turning to Facebook and Twitter, while GenZ, or the iGeneration, is skeptical of brands and places more value on peer-to-peer reviews–even from strangers. Consumers now look to six or more sources for information before buying a new product. This fractured media consumption trend makes it difficult for brands to build brand awareness, earn consumer mindshare, and drive sales.

According to our MMNPL survey, Facebook is now the second-most used source for new product launch information behind TV commercials. Brands are using Snapchat to provide exclusive, limited-time opportunities to fans, closing the gap between virtual and in-store retail experiences. Meerkat, which was the darling of SXSW 2015, allows people to experience anything virtually through live video streaming on their smartphones. More apps of this nature are surfacing every day.

Brands must be creative and nimble in their approach. Here are some tips brand and marketing managers can use to leverage converged media to their advantage:

1. Use social media as a supporting character, not the star performer. Taco Bell got it right with the launch of the Cool Ranch Doritos Locos Taco, sending customers on a wild goose chase to get the news about this new product. The brand used social media to leak that a flower shop in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District was giving out Cool Ranch Tacos, but only to those who knew the secret “blue bouquet” password. This was a clever use of social media, but not the only launch tactic. Taco Bell supported the social media stunt with a press release, national media coverage and Super Bowl commercial.

2. Use social media to leverage and support an in-person launch event. When we wrote about the Amazon Fire phone launch for Harvard Business Review in June 2014, Amazon missed the mark in disrupting the smartphone market. Why did the Fire phone fizzle? Aside from the lackluster product specs, the launch didn’t have much spark. While Amazon took a page from Apple’s playbook—creating a launch event, some tech blog and online news coverage—they needed to put more muscle behind the launch by activating an integrated social media strategy.

3. Use social media to build or capitalize on a consumer’s emotional connection to a brand. When Hostess declared bankruptcy in 2012, Twinkie fans mourned the loss of the classic American snack. That was until the brand launched “The Sweetest Comeback in the History of Ever.” After a hugely successful earned media campaign with widespread coverage, Hostess promoted the relaunch on all social media channels, centering the campaign on creating emotional responses in consumers who had been devastated by the departure of Twinkies. The relaunch generated more than 350 million Twitter impressions and 500,000 new Facebook fans..

4. Use social media to support a launch by knowing your target demographic and their social media preferences. Madonna owned 80’s radio waves, but if you asked a teenager today the question, “Who is the Queen of Pop?” the answer would fall somewhere between Selena Gomez, Taylor Swift, and Ariana Grande. So when it came time to launch her new song “Living for Love” Madonna didn’t turn to traditional channels like MTV or radio she used in her prime. Instead, the singer launched on Snapchat’s Discover platform to appeal to today’s pop music listeners.

5. Use social media to host contests that foster loyalty and reward brand advocates. Rewarding brand advocates and fans with the chance to win products through social media drives engagement and repeat fans. New product launches lend themselves perfectly to these contests, because brands can use product samples as giveaways to entice consumers to try before they buy. We help our client Sunstar GUM execute monthly Facebook sweepstakes to boost product awareness, real-time engagement and expand its fan base. The contest benefits? We experience significant spikes in brand reach and impressions that correlate to sales.

6. Use a blogger outreach strategy to help launch your product. Last year when P&G launched its new Swiffer Sweep & Trap, the company needed a fresh way to reach its target demographic–parents and homeowners–through social media. At a New York City “Make Meaning” launch party, P&G invited mommy bloggers to bring their children and make messy crafts, then use the Swiffer Sweep & Trap to clean up. The bloggers took photos of the event and documented their experience with the product on their blogs. Bloggers are key influencers when it comes to launching new products as their loyal followers want to try recommended products.

7. Use a hashtag to create, ignite, and track the conversation on social media. Hashtags are essential to follow chatter surrounding a launch campaign. Wendy’s used the hashtag #PretzelLoveSongs to launch its Pretzel Bacon Burger, asking fans to share their thoughts about the new product. The brand followed responses using the hashtag, chose the best ones, and then activated singers like Nick Lachey to sing the tweets on video. #Success.

8. Use visual social media to give people an inside look at a B2B company. There’s a misconception that certain social media platforms, like Pinterest and Instagram, are meant only for consumer brands. General Electric does an exceptional job breaking this mold as a B2B company, using Instagram as a window into the science behind some of GE’s most cutting-edge technology. Through visual campaigns on Instagram, the culture and history of the 120-year-old company is brought to life and followed closely by brand fans.

9. Use social media to let consumers create the new product. Brands want to create products consumers will buy. Consumers want control. Social media allows for both. When launching a new product, social media doesn’t have to be strictly promotional—it can play a starring role before manufacturing begins. Lay’s did this with its “Do Us a Flavor” campaign, asking social media followers to suggest their own new chip flavors. The brand chose a winner—Kettle Cooked Wasabi Ginger chips—and made it available in stores. You asked, Lay’s delivered.

10. To maximize effectiveness of a social media campaign, always stay ahead of “the next big thing.” No matter what the product or campaign, build your teams—marketing, sales, advertising, PR, Web development and more—with forward thinkers who enjoy reading tech blogs, industry news sites and downloading the latest apps. Learn about new social apps like Meerkat and Periscope before they hit the mainstream media sphere. You don’t want to waste time, money and passion implementing an outdated launch plan that features yesterday’s social media channels.

How to Refocus a Meeting After Someone Interrupts

You did everything you were supposed to do: Invited all the right people, sent out an agenda in advance, and got everyone’s agreement on the process. Despite your diligence, your meeting is being hijacked. How should you handle a persistent interrupter? Will it work to just ignore the person? And how can you get the meeting back on track?

What the Experts Say

Whether it’s a team member who disagrees with your approach, an employee from another department who brings up irrelevant information, or a colleague who wants to use your meeting as a soapbox for his own personal agenda, dealing with interrupters during a meeting is challenging. “It’s the workplace equivalent of having someone steal the parking spot you were aiming for or jumping ahead of you in the line at the grocery store,” says Judith White, visiting associate professor at the Tuck School of Business. “When someone interrupts you, blocks you, or otherwise thwarts your intended action, it’s natural to feel upset,” she says. “This is a basic instinct and you will always have a flash of annoyance.” The key to successfully dealing with interrupters is to quash your frustration and instead “operate from a mindset of curiosity,” says Roger Schwarz, an organizational psychologist and the author of Smart Leaders, Smarter Teams. Here’s how to handle this often frustrating situation.

Go in prepared

A “well-designed agenda” provides both “a structure for the meeting and serves as a point of reference,” according to Schwarz. People are less likely to disrupt a meeting if they feel like they had a hand in shaping it. Send out a proposed agenda ahead of time and ask your team for input. Give them a time frame within which to make recommendations and ask that they include a reason why they think the item is worthy of discussion. Everyone should have a say but “the team leader gets the final decision about what to include.” While an agenda does not entirely prevent interruptions, “it becomes the basis of your intervention,” says Schwartz. Once you’re in the meeting, if someone interrupts with an off-topic remark, Schwarz suggests saying something like, ‘I don’t see how your comment connects to the issue we’re talking about now. Help me understand how the two relate.’ If he can’t do that, “then you use the agenda to pick up where you left off,” he says.

Stay calm

When someone interrupts or challenges you in a meeting, it’s important to respond in “a leaderly way,” says White. “Don’t get emotional — if you look threatened or angry, you will lose the trust of everyone in the room.” Rather, your goal is to “react with humor, kindness, inclusion, and assertiveness.” Modulate your tone of voice and inflection, too. When you respond to the person who is interrupting, Schwarz says, “You should talk in a genuinely curious, not frustrated way.”

Further Reading

[image error]

The Seven Imperatives to Keeping Meetings on Track

Meetings Article

Amy Gallo

Everyone knows good meeting practice — but few actually follow it.

Save

Share

Listen, validate, redirect

Don’t be tempted to ignore the interruption and move on. At the point of interruption, “you need to stop talking and listen to what the person has to say,” says White. Then summarize his points “to let him know he’s been heard.” Let’s say, for instance, you’re leading a meeting about new corporate initiatives, and your colleague, Bob, interjects with, “Why are we bothering to discuss this? We don’t have money in the budget to execute these ideas.” You should then say, “Bob, your point is that we don’t have money in the budget for this. And that’s a good point.” After “validating his comments,” one strategy for moving on is to “redirect the discussion.” The people around the table — even the interrupter — “are counting on you to lead the meeting in a productive direction.” Start by “restating the purpose of the meeting.” In this instance, you could say something along the lines of, “We have great minds in this room and the president of our company asked us to work together to come up with cost-efficient ideas; I am confident we can do it.”

Probe further

Don’t always rush to redirect the conversation, however, warns Schwarz. Your goal is not necessarily to move through the meeting agenda as quickly as possible. Rather, your aim is to “address issues efficiently, but also in a way that leads to a sustainable solution,” he says “When a colleague interrupts you with a comment you think is off-topic, that’s not a fact; it’s an inference,” he says. Ask your colleague to elaborate on his point; if you’re still unsure how his point relates to the topic at hand, ask others at the meeting for help. Frame the interruption as “an opportunity for learning a new perspective,” he says. “Think: What does he know that I don’t know?” It may be that he has a point you haven’t thought of. “Take time to address legitimate issues because they’re not going away,” says Schwartz.

Be resolute and direct

When a colleague persists in interrupting, is off on a tangent, or keeps on making the same point over and over, be direct and firm, says White. She suggests saying something like: “Rich, you’ve brought this issue up before and we heard you. If you would like to stay after the meeting and talk with me, I’d be happy to discuss the matter further, but now we need to get back on track.” Or you could directly address the colleague who keeps on interrupting. Schwarz recommends a script like this: “Bob, I’m seeing a pattern, and I’m trying to figure out what’s happening here. Is there something going on that’s leading you to bring up these items?” While some might contend that strategy puts Bob on the spot, Schwarz says, “you need to deal with the issue in the place where the data lie — within the team.” Handling situations in the open also allows you “to model to your team how to have challenging conversations” and provides a forum for others to “add relevant information.”

Use body language to take back control

When your meeting is in danger of derailment because of insistent or hostile interrupters, you can take back control using body language and non-verbal communication. “If you’re already standing, take a step or two toward the person who’s interrupting you,” says White. “Face that person and hold his gaze for five seconds — it will feel like an eternity.” Never cross your arms. “You should appear open,” she says. Then, walk slowly around the table, “stand directly behind the person who’s disrupting the meeting, and address the rest of the room.” Proceed accordingly. This, of course, requires confidence and finesse. Even though it’s not always easy, “it’s a powerful way to exert influence,” she says.

Consider having a one-on-one conversation

After a meeting filled with tense and numerous interruptions, you might spend a little time alone “reflecting on whether you’re doing anything to contribute” to the problem, says Schwarz. It might also be worth approaching the interrupter for a one-on-one conversation. “Don’t argue with him after the meeting and never scold,” says White. “He wants to feel heard.” Instead, pose questions and listen. Ask: What is your thinking on this issue? What would you like done differently? What’s important to you? “It may turn out that you and he want the same thing, in which case, propose that you become allies,” she says. On the other hand, “you can agree to disagree.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Prepare an agenda ahead of time and ask colleagues for their input

Listen to what the interrupter is saying and validate his points

Redirect the conversation by restating the purpose of the meeting

Don’t:

Get upset and emotional about the interruption — stay calm and collected

Be in a hurry to brush off an interruption — sometimes it’s worth probing further to gather more information

Scold your employee after the meeting — instead pose questions and listen

Case study #1: Think about interruptions as learning opportunities

Adam Goldstein, President of Royal Caribbean Cruises and the Acting Global Chair for Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA), acknowledges that workplace hierarchy is a big factor in an employee’s likelihood of interrupting the person who’s in charge of a meeting.“There’s a strong consciousness of rank when it comes to people’s ability to speak out in meetings,” he says.

A couple of weeks ago, two of Adam’s colleagues at CLIA — we’ll call them James and Kate — interrupted him during a meeting to bring up an issue that was not on the agenda: Their concern that certain revenue generating programs CLIA ran were actually a disincentive to some international sales staff.

Adam was not aware of this potential problem, so he asked James and Kate to elaborate. Adam wanted to make sure he understood. “I challenged them a little bit, and I pushed back,” he says. “I wanted to be crystal clear on their objections.”

From Adam’s perspective, it was not a particularly tense exchange. However, a senior staff member told him after the meeting that James and Kate were worried they had “damaged their standing” by interrupting him. “I didn’t feel like I was harsh, but I was told there was a ‘significant level’ of nervousness,” he says.

Through an intermediary, he assured James and Kate that he was grateful for their willingness to speak out during the meeting. “I learned something because they were willing to speak.” And when he sees them next, he’ll tell them in person.

“If you want to get the best out of people long-term, you want to hear what they have to say,” Adam says. “You want people to leave feeling positive about the meeting and their participation. It’s very daunting for someone to raise his hand. I want to send a signal that I want to hear that person’s opinion.”

Case study #2: Listen to concerns and be willing to address them in future

Melissa Anthony Sinn, the founder and CEO of anthonyBarnum Public Relations, an Austin-based communications firm, leads a regularly scheduled meeting with her senior staff. The week before each meeting, Melissa distributes the agenda through a shared online folder.

“If people on my team have additional items they’d like to discuss, they need to call me or email me beforehand,” she says. “I know from past experience that if we make up the agenda on the day of the meeting, there are all kinds of things that may be bothering people [that they’ll want to add to the agenda] and the meeting veers off course.”

A couple of months ago, however, one of Melissa’s direct reports — we’ll call her Susan — interrupted the weekly team meeting to bring up a topic that was irritating her: individual workload challenges. Susan hadn’t warned her that she planned to broach the topic.

Melissa was caught off guard by Susan’s interruption, but she was aware that some employees had problems with the workload. “Capacity is a high voltage issue here because people have myriad responsibilities at any given time, but those responsibilities change as we evolve as a firm,” she explains.

Melissa listened to Susan’s complaint and did not outwardly react. “As the leader of the meeting, I have to be very contained,” she says. “I didn’t respond emotionally as that would have been unproductive.”

She was reluctant to delve into the issue because the agenda was chock-full of other, more time-sensitive items. So Melissa paused and took a deep breath. She addressed the team by repeating Susan’s key points. Then, she said, “I hear you, and I appreciate that capacity is an issue. This meeting is focused on other matters. If you would like to discuss capacity at the next meeting, we can do that.”

After Susan’s interruption, Melissa stuck to the agenda. “I admit I wasn’t always able to get meetings back on track in the past,” she says. “But I need to value people’s time. It takes discipline.”

Not Taking Risks Is the Riskiest Career Move of All

Mark was a survivor. Until he was fired in 2012, six months shy of his 50th birthday, he’d done everything right — rising through the ranks of the book publishing industry, from editorial assistant to associate editor to senior editor, then into management as an editor-in-chief. But as e-books and Amazon destabilized the industry, and waves of consolidation contracted available jobs, Mark (not his real name) admits today that he hadn’t “paid attention to the writing on the wall.” He confessed that he’d spent the 18 months prior to being fired living in denial as his team was reorganized. “Despite that,” he says, “I clung to my job rather than start thinking about how to leave. At that point, I couldn’t conceive of a life outside of the confines of corporate publishing, of not being at the center of the club I’d been a part of — and a star in — since the age of 21.”

Mark’s story is a cautionary tale for us all. In my experience, Mark’s kind of wishful thinking — that things will sort themselves out on their own — rarely works out. Not taking action has costs that can be as consequential as taking risks; it’s simply less natural to calculate and pay attention to the “what-ifs” of inaction. In today’s marketplace, where jobs and job categories are being destroyed and invented at an accelerating rate, I’d argue that the riskiest move one can make is to assume that your industry or job is secure. Just ask former employees of Countrywide, British Petroleum, or Newsweek if you doubt me. Former Chief Talent Officer of Netflix, Patty McCord, says that companies should stop lying to people about their job security, because there’s simply no such thing.

Research I conducted in 2012, 2013, and 2014 with the global advertising agency JWT Thompson for Risk/Reward, my forthcoming book, suggests that anxiety about our job futures weighs heavily these days. More than half of the respondents to our surveys — all over the U.S., with people ranging from janitors to CEOs, old as well as young — were thinking of changing not just their jobs, but their careers. Think about that. Half of all Americans long to do something dramatically different with their working lives.

But it’s hard to jettison a career decades in the making in the pursuit of something new. There’s an enormous gap between dreaming about doing something different, particularly if one has spent years building skills and rising through the ranks, and actually doing anything about it. It’s terrifying to think about just letting go of one’s hard-earned law degree and years invested on the law-firm partner track in order to write for television, as an acquaintance of mine has done. Most people dream, but fail to act.

You and Your Team

Mid-Career Crisis

When you’re feeling stuck.

What stops us? There are all sorts of complicated financial and behavioral barriers to risk-taking — loss and risk aversion, the sunk-cost fallacy, poor planning — but basically it boils down to the fact that as human beings, we are wired to resist giving up the known for the unknown. None of us tolerates ambiguity well — particularly when the losses and gains underpin our livelihoods or the projected long-term happiness of our families. Psychologically, particularly during tough economic times, people feel driven to hold onto an unsatisfactory job rather than gamble on something with uncertain odds that might be better in the long run. And we all have different levels of innate risk tolerance that inform our calculus for evaluating probable gains and losses. So how can we turn self-defeating inaction into sensible action?

Start by building vibrant networks. In Working Identity: Unconventional Strategies for Reinventing Your Career, Herminia Ibarra, an organizational behavior professor at INSEAD, writes that people’s existing “contacts [don’t] help them reinvent themselves…the networks we rely on in a stable job are rarely the ones that lead us to something new and different.” There’s a reason, when we’re interested in making a 45- or 90-degree career shift, why most jobs suggested by headhunters rarely feel right. The majority of people we know in one line of work can only imagine us continuing to do the same thing. So as we meet more people employed in a wide range of professions, our ability to imagine ourselves doing something different grows stronger.

Stanford sociologist Mark Granovetter discovered that the contacts most helpful to people looking for new jobs were neither their closest friends, nor new acquaintances, but rather people with whom they had relatively weak ties that had been forged and maintained over several years. In addition, the more different their contacts’ occupations were from their own jobs, the more likely people were to successfully make a major career change.

Perhaps the biggest impediment to change in our working lives is the sense that any significant change has to be all or nothing. I either quit my miserable job or just suck it up and grind along. I’ve got to make a comprehensive business plan before I test whether my English muffin/croissant hybrid and baked-goods truck can generate enough income for me to live. I’m good at structuring logical arguments so I should quit sales and become a lawyer. Instead, we need to break problems into small actions. The more logically-oriented person might, for instance, test-drive the legal profession as a paralegal before assuming the expensive three-year commitment of getting a law degree. The amateur cook with a killer recipe could approach a local bakery with his novel product to see if they’d be willing to sell it, getting market feedback before spending time crafting a business plan for a new venture. The person in the miserable job could volunteer weekends in an organization they think might make them happier — learning what the work is really like from the inside before chucking it all on a dream that may be a fantasy. Then, armed with real-world data, each of those hypothetical career-changers would have more clarity and about the correct next steps. The trick is to start with the immediately, manageably doable and do.

We need to continue to find new challenges, and to acquire the skills to meet those challenges. Moreover, according to Sonja Lyubomirsky, a psychologist at the University of California, Riverside, the act of committing to goals also provides structure and meaning to our lives that leads to more overall happiness. She quotes G.K. Chesterton in this regard: “There is one thing which gives radiance to everything. It is the idea of something around the corner.”

Real life, by necessity, is improvisational and interactive, crafted incrementally through our responses to the particular circumstances at this moment in time, and the next, and then the next. As author Tom Peters wrote, “I have said and mean with all my heart I’ve only learned one thing ‘for sure’ in 48 years: WTTMSW. Whoever tries the most stuff wins.”

3 Ways to Make Less Biased Decisions

Unconscious bias – judgments and behaviors toward others that we’re not aware of – is everywhere in our lives. And while this type of bias may seem less dangerous in the workplace than it may be on the streets of Ferguson, Mo., or in , it still leads to racial injustice.

In March 2013, a U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission report identified “unconscious bias and perceptions about African Americans” as one of seven “major obstacles hindering equal opportunities for African Americans in the federal work force.”

In fact, simply having a name that sounds black can reduce the chance of you getting an interview, according to a study conducted by researchers at MIT and the University of Chicago. The research showed that this is true even at companies that are actively looking for diversity in hiring. Similar trends have been identified in virtually every aspect of the talent management system. For example, another study from the University of Warsaw, found that women described with feminine job titles (e.g. “chairwoman”) are perceived (by men) to be as significantly less warm and marginally less competent than women with masculine job titles. And men reported that they were less likely to hire these women.

In my 30 years of consulting and research, I have seen this unconscious bias play out again and again. It not only results in lack of equity in organizations, but in poor talent management practices. How can we hire, retain, and develop the best people — regardless of race — if we are not even aware of the forces that dominate the choices we make?

Unfortunately, it is unlikely that we can eliminate our biases. We are learning more and more that they are a natural part of human functioning. Psychologist Joseph LeDoux refers to bias as our human “danger detector,” as it provides a quick way to insure our safety. We make fast judgments about what is “normal” and what isn’t and often this works in our favor. For example, a good leader may sense that certain behaviors are consistently more dependable in meeting client needs and may develop a “bias” toward those approaches. Even if they are not correct 100% of the time, they may still make more sense as a rule than approaching each client situation as if it has never happened before. Of course, that doesn’t mean that one approach should be chiseled in stone.

The good news is that there are things that we can do to mitigate the negative impact of biases on our organizational decision-making.

First, by realizing and accepting that we all have bias, we can learn to watch for it in ourselves and help others who work with us to do the same. This process of building awareness is similar to what happens when we step on the clutch in a standard transmission automobile. The motor doesn’t stop running (bias doesn’t stop), but the car is no longer moving forward. When we are on the lookout for biases, they are less likely to blindly dictate our decisions.

Second, we have to develop tactics that help us make decisions more consciously. There are three types of approaches that can help: priming; reorganized structures and systems; and new forms of accountability.

Priming is a memory effect that gets created when one activity subtly, and often unconsciously, impacts subsequent behaviors. By consciously priming people to pay attention to potential areas of bias, extensive research as well as our experience with clients has shown that they can be encouraged to be more conscious of their decision-making processes. For example, before reviewing resumes, managers can be asked to respond to a series of questions like:

“Does this person’s resume remind you in any way about yourself?”

“Does it remind you of somebody you know? Is that positive or negative?”

“Are there things about the resume that particularly influence your impression? Are they really relevant to the job?”

“What assessments have you already made about the person? Are these grounded in solid information or are they simply your interpretations?”

Similar safeguards can be put in place around many aspects of talent management: recruiting, interviewing, hiring, promoting, and performance reviews. As Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman said: “The odds of limiting the constraints of biases in a group setting rise when discussion of them is widespread.”

Reorganizing structures and systems can also help reduce the impact of bias. Structure creates behavior in organizations and by creating consistency in how certain processes get carried out, you can encourage less biased behavior. For example, structured interviewing processes, in which the questions are consistent across candidates, have been found to reduce bias relative to unstructured or free-form interviews. In fact, as a rule, structured processes can reduce the patterns of unconscious bias that take over when people are just “trusting their gut” in informal structures like mentoring, managing, coaching, and reviewing performance.

Finally, you can put new forms of accountability in place so that it becomes clear when bias is occurring. For example, if a manager gives 10 performance reviews, five to men and five to women, and four out of the highest five are women, it should at the very least call for an inquiry into whether there might be a pro-female bias in the process. It might be total coincidence, but it is worth checking. You might get input from some colleagues who also work with the people being rated and see if they make the same evaluation.

Another place to encourage accountability is in diversity metrics. If you look at metrics individually you might argue that you’re reaching your company’s diversity goals of representation at each point in the process. But if you look at the batch of metrics together — for example, the percentage of people who apply for jobs, the percentage who are offered jobs, the percentage who accept those jobs, and the percentage who are successful in their jobs after six months — you are far more likely to be able to pinpoint the places in the system where breakdowns are occurring.

Bias may be as natural as breathing and it may very well be impossible to drive it out of human consciousness. But by shifting your mindset and inviting constant inquiry into how you make decisions, you can create businesses in which the diversity of your workforce is truly the strength that you hoped it would be.

Can Nokia Reinvent Itself Again?

Nokia, today’s telecommunications networking company, has made corporate transformation into an art form. Established originally in 1865, as a paper mill, it became a public company in 1868. Over ensuing decades, the company expanded into an ever-more-bewildering array of product categories.

Often entering new categories through acquisition, at one point it made rubber boots and tires; telephone and power cables; even household products like toilet paper (I’ve seen them myself). But it was power generation that helped Nokia survive its first existential crisis: in the aftermath of World War I, the company threatened to go bankrupt and was acquired by a significant customer, Finnish Rubber Works, in order to maintain its power supply. (That’s where the rubber boots came from.)

In the following decades, the company operated as an industrial conglomerate, with different divisions operating more or less independently and without too much rhyme or reason under one roof (it is hard to make the connections between footwear, gas masks, and robots). As the company explored new markets, it began to make additional investments in pre-cellular mobile radios and other componentry in the emerging market for mobile communications.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, the highly diversified company had once again gotten itself into real trouble, helped not one bit by a deep recession in Finland. Another existential crisis was well underway. Friends have told me that the company even tried shopping itself to rival Ericsson, to no avail.

In 1992, new CEO Jorma Ollila and his team made a decision that is iconic in the world of corporate reinvention, going all-in on the emerging telecommunications markets. The company (finally) divested its paper plants, downsized its consumer electronics, and within a couple of years sold its power unit, television, and tire and cable units. The ensuing focus on creating a leading position in a rapidly growing global market created legendary results, with Nokia soaring to the number-one position in the mobile phone category throughout the nineties.

Interestingly, as a member of the Executive Committee later told me, the decision was far easier than the choices the company faced as it enjoyed spectacular success later on. “We had virtually no good options [then], so it was relatively easy to move forward aggressively into the mobile business,” he told me.

Of course, we know what happened next. Despite a record of success that is the envy of many a corporate chieftain (41% market share globally? that’s unbelievable), Nokia’s leadership failed to see the potential of the smartphone business, with its “Internet in your pocket” allure. They didn’t introduce smartphones to the market (which, ironically, they had actually developed) but even worse, they lumped the regular mobile phone business and the smartphone business together in the same division. What that led to is familiar to any student of corporate entrepreneurship: the big, established business basically rolls right over the emergent ones, with the result that when competitors such as Apple and Samsung took the world by storm with smart phones, Nokia was caught flat-footed.

After struggling unsuccessfully to regain its former glory, the firm has once again made an existential choice, selling the entire mobile phone division to Microsoft, where its software and brand are slated to disappear. Three businesses are left – the networks business, which serves many of the world’s major telecommunications companies, a mapping business, and Nokia technologies, which (astonishingly) is once more tiptoeing back into the consumer electronics space with an Android-powered tablet it plans to sell in China.

But lo, do we see the re-emergence of the company’s fabled ability to reinvent itself? News that Nokia is considering acquiring Alcatel-Lucent might well be part of an effort in that direction. The two companies would create enough heft to challenge Ericsson and China’s Huawei. In addition, combining their technologies would fill in gaps in their capability portfolios that could make the combined company a major player in the fastest-growing parts of the tech world, such as on-demand streaming and cloud computing. The possibility of making its telecommunications business into a major focus is reinforced by recent rumors that it might sell off the mapping business.

The playbook sounds familiar. Select an area of focus, ideally one that is poised to grow rapidly. Figure out how to create the scale and capability to succeed in that area. Sell off those businesses that are distractions from this focus. Be prepared to make some pretty difficult decisions. Perhaps history will repeat itself in Nokia’s favor.

April 15, 2015

What Is a Robot, Anyway?

Quick — think of a robot, any robot.

If you’re into movies, you might imagine the android from the new movie Chappie, a machine with artificial intelligence that learns morally questionable behavior. If you think more about industry, you might imagine a mechanical arm programmed to install parts on a production line. If you have dirty floors, you might think of a Roomba.

What do these and other robots have in common? What is it about them that makes them a robot? Finding an all-encompassing definition of a robot is actually a difficult problem, even for world-class roboticists. Form-factors, intelligence, and the purpose of robots can all vary significantly. And yet many of us think we know a robot when we see one. How is this so?

For Westerners at least, our working cultural definition owes a lot to robots in stories and film, as well as real-life robots past and present. But it’s worth looking further for a more considered definition, starting with the origin of the word itself.

Before robot meant what it does today, the word meant “forced labor” or “hard work.” The robot was a central European system of serfdom — according to the Oxford English Dictionary — abolished in the Austrian Empire in 1848.

Then, in 1920, a Czech writer named Karel Čapek wrote a play called Rossum’s Universal Robots, coining a new meaning for the word. In R.U.R., as it’s known, Čapek’s robots were mass produced workers assembled from artificially synthesized organic material. The play featured the first robot uprising, and the genre of dystopian robot sci-fi was born. Descendants include Terminator and Battlestar Galactica, among others.

While some research groups are working hard to make highly intelligent humanoid robots as those depicted in R.U.R., most real-life robotics efforts are decidedly less dramatic. A good place to find the staid, real-life state of robots is the International Federation of Robotics, or IFR. Helpfully, the IFR categorizes today’s robots into two major categories: industrial robots and service robots.

The IFR defines an industrial robot as “an automatically controlled, reprogrammable, multipurpose manipulator programmable in three or more axes, which may be either fixed in place or mobile for use in industrial automation applications.” For years industrial robots were all that a real robot could be.

The first industrial robot was installed in a Swedish metalworks plant in 1959. It was a jointed, actuated arm that weighed two tons. Controlled by a program on a magnetic drum, the robot relied on hydraulic actuators to adjust its position over a set of pre-programmed joint angles. It was precise, but not necessarily elegant.

By 1973, there were 3,000 industrial robots in operation. By 2003, there were 800,000. Today, more than 1.3 million industrial robots are in use or available in various industries including automotive, electronics, rubber and plastics, cosmetics, pharmaceutical, and food and beverage. Their market value is $9.5 billion. (A more complete history can be found here.)

Industrial robots will always have a place in the economy, but the relative newcomers on the scene are service robots. This category, according to the IFR, is populated by autonomous machines that complete tasks outside industrial applications. This means service robots are found in personal and professional settings: a telepresence robot at work, a robot in the operating room, an educational robot helping students learn to write code, a research robot exploring the ocean, a robot in space helping astronauts make repairs, and so on.

The industrial vs. service distinction is helpful because it defines robots based on their relationship with people and work more than around any technical factor. Combining industrial and service robots, we can generalize to offer a basic definition of a robot as an artificially created system designed, built, and implemented to perform tasks or services for people.

There are echoes of the original meaning of the word robot here, as robots are doing labor and hard work. And while this labor has historically been physical, we might also consider that robots needn’t have actuating limbs.

Much of work today is knowledge work, therefore the definition of a robot should extend even to automated computer programs to include cognitive computing, which describes IT systems that can sense, comprehend, and act. This includes pre-programmed Twitterbots on the low end and IPSoft’s Amelia artificial intelligence system on the high-end. Across the spectrum, though, robots perform rule-based work, and tend to be configurable with basic features like authentication, security, auditing, logging, and exception handling.

But even this broad definition will have to evolve as robots progress. What should we expect from machines built to be stronger and smarter than the people who made them? Will they always be limited to doing work for people? It’s a question that conjures Čapek’s robot uprising, and has prompted many essays invoking Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, among other texts of monsters and unintended technological consequences.

It’s with good reason engineers, scientists, writers, ethicists, and philosophers are considering the ramifications of advanced robotics and artificial intelligence. Even if real robots are unlikely to match their dystopian sci-fi counterparts anytime soon, they still disrupt economic sectors and directly affect the way people live and work.

Some clues to our robot future could come from an emerging field called “wise computing,” presented at the recent annual meeting for the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in San Jose, Calif. Wise computing as a research field originated in Japan, where cultural attitudes toward robots are less fraught as in Western countries.

The movement’s aims are to investigate the ethical, legal, and social relationships between humans and machines, to develop machines that can make decisions with a kind of programmatic wisdom, and to help humans make wiser decisions themselves. At the AAAS panel, researchers from industry and universities in Japan and the UK discussed the possibilities and challenges of such an approach.

While it might not catch on in the western world anytime soon, wise computing offers an intriguing modification to the western cultural definition of robots. Imagine: Future robots could be built to include a kind of ethical clause that limits what they are allowed to do. As we progress with these technical, social, and ethical challenges, our definition of what a robot is will have to change too.

What to Do If a Feud Threatens Your Family Business

Reading the banner headlines about family businesses gone sour — Market Basket, Rollins, L’Oreal, among others — people often conclude that conflicts in family businesses spiral out of control like mighty tornadoes that destroy everything in their paths. Actually, strong disagreements are inevitable in all human relationships, but families that own businesses are more at risk for serious conflict than ordinary families because the power, status, and money at stake are greater, and so the decisions that these families face are also of greater consequence.

Our firm’s partners have worked with more than 200 family business clients in 20 countries, and over time we have seen seven predictable stages of conflict. The tragedy is that these stages are largely avoidable, but the owners of family businesses have to be aware of them — and of the ways to extricate themselves when they get caught up in a spiral.

The seven stages:

1) Interests diverge. In their book in Getting to Yes, Harvard negotiators Roger Fisher and William Ury define an interest as a broad desire that a person or group of people have for something. Some interests are shared; others are individual. Most business families are united first and foremost in their wanting to protect the Golden Goose; i.e., to keep the business healthy. However, given that family members have different roles and responsibilities as the family business grows, interests naturally diverge. Some family members work in the business, and some are owners (some are both; others are neither). Those employed in the business will be more inclined to channel profits to re-investment and bonuses, while owners will be disposed to pay higher dividends. Where anyone stands on a particular issue will be influenced by where they sit in the family business system.

2) Positions harden. Once interests diverge, individuals or groups typically adopt different positions on issues. A position is the specific way that people try to get what they want, and positions become clear as soon as decisions must be made. Again, all families have to make important decisions — e.g., where to live and where to send the kids to school — but business families are called upon to make significant decisions more frequently. Because these decisions often involve the allocation of resources, positions can degenerate into zero sum games: He wants more; therefore, I get less. Positions harden, and suddenly everyone feels that the matter can be resolved in only one way – his way. Positional bargaining begins, and even if a solution is reached, one party often comes away feeling that the solution is unfair. Consequently, positional bargaining typically leads to outcomes that are neither successful nor sustainable.

3) Communication breaks down. When there is a failure to recognize common interests, and when positions harden, then communication gets badly muddled. Family members start shunning one another or sending flaming emails — or even conversing through memos that are vetted by their personal lawyers. Typically it’s not silence or all out war, but rather a tense dynamic where people break away and don’t talk for a while, and then the tension bubbles up to the surface again, and things explode. We worked with one client family where three brothers would get into huge screaming matches, yelling verbal abuse, before lapsing into silences that threatened the business. Although the brothers were effectively the CEO, COO, and CFO, they wouldn’t talk to one another for months after a fight, not even on business matters. They each squandered opportunities to reconcile their differences.

4) Alliances form. When people stop talking directly to each other, alliances inevitably begin to take shape. Everyone feels forced to take sides, and partisan camps spring up, often starting with the spouses of the “wronged” family member. Alliances harden as confirmation biases set in: All actions of the other side; are interpreted through a lens that confirms the righteousness of the alliance’s view. In this stage, things get very personal, and each side labels the other as crazy, stupid, lazy, or worse, and this polarization makes compromise even more difficult. In business families, five kinds of alliances are common: alliances that form around family branches (e.g., brother’s side versus sister’s), owner groups (e.g., voting versus non-voting shareholders), participation levels (owner-operators versus passive owners), gender, and generations (senior versus next). We are familiar with one business family, for example, where the senior generation has aligned itself against the next generation of operators and managers in such a way that, if not resolved, threatens the very survival of the business.

5) Proxy wars are unleashed. As alliances get entrenched, those on opposing sides look for ways to bolster their positions, and inevitably they entangle other people in the conflict. Family members call in insiders; non-family managers and employees, for example; to serve as pawns in a game that nobody will win. Proxy wars take multiple forms: In a very large firm, businesses aligned with, or led by, the other side are sold; aligned senior managers are fired; dividends are withheld to hurt some passive owners, at the expense of the many. At one client family, a board member actually threatened to unleash an out-of-the-ordinary audit of the work of a CFO aligned with the other branch, not too subtly accusing him of fraud.

6) Advocates are called in. After involving innocent insiders, the next move down the conflict spiral is to bring in expert outsiders as advocates for a particular point of view or position. Warring Co-CEOs, who were cousins, called in a compensation consultant, whom one cousin accused of being biased. The cousins dismissed the consultant, but the tension between them mounted. Even worse, family members lawyer up. Since lawyers are obligated to advocate for their clients, they make the strongest possible, uncompromising case for why their side is in the right, and the other side in the wrong. The nature of the dialogue changes, too, as the search for unlawful behavior takes center stage over reconciliation. For this reason, even the best-intentioned lawyers almost always ratchet up the conflict. We remember one painful board meeting with seven family board members, each with their personal counsel sitting behind them. The meeting degenerated into one legal objection after another that smothered all attempts at making important decisions.

7) Lawsuits are filed. Turning a family difference into a lawsuit is an act of all out war. Families can and do get to this stage, and it’s almost always counterproductive, and expensive, both financially and psychologically. Our colleague, Steve Salley, himself an attorney, summed up the situation: “Family litigation is the ugliest form of warfare: civil war. Hostages and casualties vastly outnumber apparent winners, and the scars are permanent. Any victories end up being tragically unsatisfying.” When families think of lawsuits as the remedy, they are not taking into account the likely regret they will feel for the next five or 10 years, or longer, as well as the impact on their employees and the community.

We see the tragic unfolding of these seven stages of conflict all the time in the business families with which we work. We have observed great anguish and frustration. Families fractured. Careers and businesses ruined.

The good news is that we have also witnessed a difficult, but replicable, path out of the conflict spiral — a few important steps that can get the business family on the right path again.

See the opportunity in the pain. If family members feel enough pain, then they become willing to see their interests in a new light. Pain brings fresh opportunities. Indeed, intense pain is a sign that interests have actually shifted, and this shift allows warring factions to come to the table and find compromises that didn’t exist before. Interests can change so much as business families go down the conflict spiral that the client with the seven lawyers in the boardroom actually told us later: “All we want now is peace and prosperity.”

Re-tap the ties that bind. After interests are redefined, business families who successfully break the conflict spiral do so by acknowledging the ties that bind them together. These families tap into a visceral, almost biological, realization that family matters deeply, and that protection of the family is an almost evolutionary imperative. As one family member put it: “Let’s work out our differences so that we don’t poison the next generation.”

Go back to common interests. After rediscovering the emotional ties that link them, successful business families are then ready to create another deal together based on the new interests that they share. To do this, however, they need to return to ground zero. Even when relations have improved, family members can’t just reverse direction and go from stage seven back to stage three — from filing a lawsuit to just plain communicating poorly. They have to go right back to the beginning again to try to find some points of commonality in their redefined interests.

Re-set expectations. Finally, once families have completed all the previous steps, there comes the inevitable resetting of expectations. Families that have sued one another may never end up as friends again, but they can revise what they want from one another. Once-warring family members may never forget the past, but unless they can forgive one another, they will never be able to look together towards the future.

Tragically, there are times when families just can’t turn their pain to their advantage. They can’t go back and find a commonality of interests, a new grand bargain; they can’t forgive the mistakes of the past. Then it’s time to sell the business and to separate socially, if possible.

Even better than knowing how to get out of a conflict that is spiraling downwards, however, is knowing how to avoid the seven stages of conflict. Really understanding the cost of litigation — for example, appreciating how ugly is it, and how much families will regret it later — can go a long way toward keeping them from waging all out war.

If family members want to avoid the disastrous spiral of conflict, they should keep an eye open for the seven escalation points. When people disagree, they often think that the best way to address their interests is to leap into action. And the tricky thing is that this reaction is often rational. If someone in the family is not honoring a written deal, the logical step is to turn to a lawyer. It’s also reasonable that the other party will hire his own lawyer. Taken individually, all these steps make sense. Ironically, it’s rational actions provoking rational reactions that send business families down the devastation spiral.

We advise family members, therefore, to take a deep breath before allowing to themselves to escalate to the next stage. Recognize that whenever they say, “I think this is the only way to do it,” they’ve taken a step towards escalating conflict in the family business system. Whenever they give up truly trying to communicate, they’ve taken a step toward all-out war. Each of the seven stages of conflict is a step that a family member or family branch can take or not — there is a choice. And that’s the really hard part because each family member has many chances to keep the family and the business from self-destructing. That’s a huge opportunity, and a big responsibility.

Some of the identifying details in this article have been changed to protect client confidentiality.

Store Brands Aren’t Just about Price

More and more, I hear different twists of the same question from clients: Can emotion still influence buying behavior in world where the mobile internet, with real-time access to product reviews and price comparisons, is training consumers to shop purely on rational facts?

On the surface, it looks like rational benefits are winning. According to Nielsen, in the last three years leading national brands in grocery stores, which probably command the lion’s share of traditional “emotive” advertising dollars, grew sales 0.7%. Meanwhile, private label, or store brands, grew 8.8%. That’s scary data, if you are one of the big brands who rely on emotion to drive the business

The core assumption here is that private label sales are only about price. To test this, we decided to take a look to see if private label superconsumers — consumers who buy a lot of private label and have strong emotions about private label — actually existed. It turned out they do exist, but they were different, more prevalent, and more important than what we expected.

The top 15% of private label shoppers across all food, drug, club, and mass channels account for 50-65% of private label sales for that particular retailer. But they’re not just important for private label sales — they also account for 40-55% of total sales for the retailer. So they are extremely important from an economic perspective. But the assumption was a consumer who buys a lot of private label was only concerned about price and other functional benefits. To our surprise, we were wrong.

First, we found two overarching emotions from private label superconsumers. The first emotion was these consumers felt a great deal of affection for that specific retailer overall. Someone who buys lots of Kirkland feels very strongly and positively about Costco. The second emotion we found was a deep level of pride about being a private label superconsumer. The Freakonomics podcast “How to Save $1 Billion Without Even Trying” talks about how doctors and chefs were much more likely to buy private label in their respective fields and feel proud about doing so as an expression of their expertise.

But as we dug further into the integrated big data-set of sales and motivations, it revealed further insights. The incidence of a consumer solely focused on the lowest price and no benefits was extremely tiny. Instead, we found two core private label superconsumers on interesting ends of the value = benefits/price equation. One is a purpose driven shopper; the other is a treasure hunter. Each is driven by emotions, not just price.

The purpose driven supers are not robotic price chasers, but want good quality at a great price. They are consumers with big life aspirations and the discipline to reach their purpose and goals. Life aspirations included starting a family, saving for college and retirement, and making it easier to care for sick family members. But they also care about benefits and don’t want to sacrifice today in order to enjoy tomorrow. These purpose driven supers felt an extraordinarily deep level of emotion for the retailer brand at levels typically associated powerful lifestyle brands in apparel and luxury goods. This is not surprising when you consider that the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure survey says food for at home expenditures was $3,977 per household in 2013. Savings of 25% equal $1,000, which is real money and about 8% of average discretionary income in 2015. Real emotion comes from making a real difference in a consumer’s life.

The treasure hunting supers are the inverse of their more price driven cousins, they want great quality at a good price. These are consumers who love food, love to cook, and find joy in discovering new experiences. These are consumers who really know their food well and can personally tell which products are better quality or have exciting new varieties. Trying new brands, including private label, is not something they are afraid of, but actually enjoy. The epitome of this is Trader Joe’s, whose entire assortment is private label. But if you ask any Trader Joe’s superconsumer, the array of variety and treasure hunt is glorious indeed.

But these treasure-hunting supers don’t just shop at Trader Joe’s. They are everywhere, but interestingly they cluster together in pockets of the country. There are in fact Super Geos — local markets with high concentrations of supers — of both types of supers that exist in pockets across the U.S. Superconsumers have a network effect and subtle peer pressure, and private label shoppers are no different. Imagine you go to a friend’s house and see a ton of Kirkland and Trader Joe’s products. That sends subtle signals that say, “Your friend is a smart person and makes smart choices. Maybe I should try more private label?”

The challenge is that too many manufacturers and retailers still believe that private label is about the lowest price. And the risk is that this becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy if companies continue to strip out benefits for a lower price.

But companies have a choice — they can find and foster growth for both purpose driven and treasure hunting supers. By innovating on the new mixes of price and benefits should create innovation opportunities for everyone. But most importantly, it reinforces the idea that the right benefits matter and are worth paying for. This way the rise of private label and profitably growing the pie are not mutually exclusive.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers