Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1288

June 5, 2015

How Banking Analysts’ Biases Benefit Everyone Except Investors

Wall Street analysts influence markets and companies daily. They release earnings forecasts and investment recommendations moving stock prices and changing investors’ portfolio decisions. These movements in turn generate responses from corporate leaders that make changes in operations, strategies, acquisition, and investment plans. No wonder CEOs and CFOs spend significant amounts of time communicating with the influential analysts covering their firms.

But how unbiased are the earnings forecasts that they release? To answer this question we studied Wall Street analysts that provide earnings forecasts for banks and other types of financial institutions or non-finance companies (‘banking analysts’). We classified all companies that are rated by the banking analysts as likely future employers or not, based on whether they have a sell-side equity department. (Companies with a sell-side equity department hire banking analysts of their own and so are potential future employers.) And we found that banking analysts’ forecasts are in fact biased in favor of potential future employers. Specifically, analysts’ forecasts for these firms are more likely to exhibit “a walk down to beatable earnings.” This is a well-documented pattern where forecasts of annual earnings are optimistic early in the year but become less optimistic later in the year, and then just before the announcement of earnings they are pessimistic. This pattern allows executives to beat their earnings forecasts, which frequently results in large positive changes in the company’s stock price. This pattern is not observed when banking analysts forecast earnings of companies that are not likely to be future employers.

Whether or not they engage in this behavior consciously, analysts do benefit from it — as do bank executives. Analysts issuing more biased forecasts for potential future employers are more likely to face favorable career outcomes and move to a brokerage house of higher status, according to our data. This usually comes with higher compensation and recognition. Moreover, bank executives appear to profit from the analysts’ bias. We find that for banks where analysts are the most biased, executives initiate the largest trades in the bank’s shares following earnings announcements and sell shares following stock price appreciations, pocketing the gains.

So then who loses? Investors, who end up receiving biased expert advice, after paying billions of dollars for these research services, therefore making bad investment decisions. Perhaps this bias in expert advice explains also why an increasing number of investors are conducting their own in-house analysis and rely more on the “wisdom of the crowds” by using signals that are generated by web-based technologies that aggregate individual opinions and measure the sentiment of people towards a company. Moreover, our results raise a number of governance issues. Specifically, board of directors need to carefully evaluate whether stock options and bonuses are awarded for meaningful value creation, not by beating biased expectations.

June 4, 2015

How to Speak Up About Ethical Issues at Work

Sometimes you sense that something isn’t right at work. You suspect that your finance colleague might be fudging numbers, your boss isn’t telling his manager the truth about an important project, or your co-worker is skipping out of the office early but leaving her computer on so it looks like she’s just down the hall. How do you know when it’s worth speaking up or not? Can you you protect yourself from potential consequences of calling out bad behavior? And when you do decide to say something, what do you say and to whom?

What the Experts Say

“Most of us don’t face a billion-dollar fraud or an issue where someone’s going to die tomorrow,” says James Detert, a management professor at Cornell University’s Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management and author of “Why Employees Are Afraid to Speak.” But even minor issues can have serious consequences. “Ethical situations at work can be cause for alarm, and are also a normal part of doing business,” says Detert. The key is to not let either of those realities prevent you from making a rational decision. “When it comes to ethics, we think it’s a test of our moral identity, which makes us more emotional, less effective, and vulnerable to self-deluding,” says Mary Gentile, author of Giving Voice to Values and director of a program by the same name at Babson College. That’s why it’s important to not only know how to recognize an ethical issue but how to raise it — especially one that may be more of a gray area, she says. “There is no one strategy or answer for all situations,” she says. “The key is to practice ahead of time, before a situation arrives so you’re ready when it does.” Here are some tips on what to do if you find yourself in a sticky situation.

Watch for rationalizations

“If something happens and you get that feeling in your gut that something’s dodgy, a lot of preemptive rationalizations come in,” says Gentile. That’s because fear takes over. “Studies show that people are likely to overestimate how awful the confrontation will be, how terrible the retaliation will be, and how long the retaliation will last. You build up all the personal horrible consequences and find ways to avoid the harm or loss,” says Detert. The most common rationalizations include: It’s not a big deal. I don’t have all the information. This is someone else’s responsibility. This must be the way these things are done (at our company, in this region, in our industry, etc). “Statements like these allow us to recognize the problem and still feel not feel bad about not doing anything about it,” says Detert. “It’s not that these statements are false,” says Gentile, “they’re just not the whole truth.” If you find yourself rationalizing in this way, question your underlying assumption. For example, “think about how many times someone says ‘no big deal’ when it’s actually a big deal,” says Detert.

Consider what’s really at risk

You also want to be clear with yourself about what’s happening. If your coworker is leaving early every day, is it worth doing something about? One could make the argument that she’s stealing time from the company and therefore taking money that’s not hers. But if she gets her work done, does it really matter? Gentile suggests asking yourself: What is the value that’s being violated here? Why is this troubling me? Detert says to consider whether it’s important to just you personally or to the larger group, either your team or the organization. Being clear about the issue will help you accurately weigh the pros and cons of addressing it.

Understand why people are acting the way they are

A useful skill when it comes to ethical situations is perspective-taking. Rather than casting your colleague as bad, seek to understand the reasons behind her actions. Typically, people have an understandable (if not defensible) motivation. Your finance colleague may be fudging the numbers because he wants to make his boss look good or he’s afraid of losing his job. Put yourself in your colleague’s shoes and try to understand what she’s trying to achieve. Gentile gives the example of someone she knows who was asked by her boss to hide the firm’s underperformance over the previous year. “Her boss wanted her to find a different benchmark that would make it look like the firm had done OK,” says Gentile. The woman thought about her boss’s goal in this scenario and “decided that he wasn’t invested in being unethical but he wanted to get through a tough conversation with a client that afternoon.” This information helped the woman decide how to respond to his request because she now understood “what was at risk for him” and instead of doing what he asked, she could provide him with information that would help him get through the conversation.

Weigh the pros and cons

“Only each of us individually can decide which issues we’re willing to lay it on the line for,” says Detert. So consider your situation carefully. What would be the benefit of speaking up? What would the consequences be if you didn’t? One of the biggest pros of saying something is that you might help the business, especially if the unethical behavior puts the company at risk of a lawsuit, damaging an important customer relationship, or losing money. You might also feel better about yourself if you don’t stay silent. Detert says that research has shown that people regret inaction more than they do actions that didn’t go well. The cons will be very situational but might include the fact that the situation is unlikely to change or you are the sole earner in your household and can’t risk losing your job. “There may be consequences and there may be times that you don’t speak up because the positives don’t outweigh the negatives,” says Gentile. Detert adds: “We live in a society where most of us are dependent on employers for salary and benefits and we don’t have the power that allows us to be free moral agents. None of us will be able to speak up about every problematic ethical issue. We are all compromisers in that regard.”

Talk to the perpetrator first

Detert and Gentile agree that when you suspect someone is acting unethically, in most cases, you should talk to him first. You might be tempted to go to your boss or your colleague’s boss, but it’s often better to give the person the benefit of the doubt and assume that, when he sees how his behavior is perceived, he’ll change. Give him the opportunity to correct his ways or to at least explain himself before you escalate. That said, if the violation is a particularly serious one, with potentially grave consequences, you may need to go to your boss, speak to HR, or call your company’s ethics hotline immediately.

Rehearse

If you decide to say something to your colleague, don’t go in cold. “Spend some time with a trusted peer, your spouse, or a good friend — someone you can talk the situation through with in a non-defensive, open way – to test your reasoning and develop an action plan,” advises Gentile. If you build confidence by rehearsing, then you’ll have more energy to engage in the conversation. And “you won’t have to rehearse as much in the future, when the same type of issues come up over and over,” adds Gentile.

Ask questions, don’t accuse

Broaching the subject by saying, “I think what you’re doing is wrong,” or giving a lecture on morality is likely to backfire. “That leads the other person to shut down and get defensive — not because they’re unethical but because they’re human,” says Gentile. “A better place to start would be to ask questions instead of making assertions,” Detert explains. Use phrases like: “Can you help me understand…” or “Can you help me see why you’re not worried…” Detert points to two reasons why this approach works. First, he says, “there’s a possibility that the person isn’t aware they’re doing something wrong and your questioning might allow them to see the problem.” Second, asking questions is “a reasonably safe way to determine if the target is going to be open to discussing this issue or whether you need to pursue another avenue.”

In the best-case scenario, your colleague may respond by saying, “Wow, I haven’t thought about it that way,” and change his behavior. Problem solved. Or he may start to rationalize his actions: “This is always how we’ve done it.” “You’re not seeing the big picture.” In this case, you want to align yourself so he doesn’t feel accused. Detert suggests saying something like “I just asked because I’m concerned about you and I wouldn’t want you to get in trouble” Or “I know we share the same overall goals, I just wanted to help make sure we were on track” or “I wanted to be sure we protect the organization’s reputation.” If your colleague believes you’re on his side, he’s more likely to be open to changing his mind about his behavior.

Escalate when necessary

It’s also possible that your colleague will react negatively to your questioning and say something like “Let’s not talk about it anymore” or “Mind your own business.” If that happens, the next step is to ask yourself: Do I want to talk to someone else about this? Or do I let it lie? “Only you can decide,” says Detert. If you want to pursue it, you might schedule a meeting with your boss and again treat it as information gathering. You can say, “I want to share what I’m seeing. I’m uncomfortable with it and I wanted to get your perspective.” If your boss doesn’t care, you’ll need to decide if it’s worth escalating further. At each step of the way, be open to what you’re hearing. “You may see that you weren’t aware of what was going on and once you have further information, your own perspective might change,” says Detert.

Protect yourself

“We know enough about whistleblowers to know that retaliation is real,” says Detert. You’ll probably never be in a situation where it’s 100% safe to speak up so “think about how you might protect yourself,” says Gentile. She suggests keeping a record of relevant conversations and enlisting allies to support you if things go sideways.

Principles to Remember

Do:

Seek to understand your colleague’s perspective — why is she acting the way she is?

Consider the benefits of speaking up against the potential consequences

Rehearse what you’re going to say before calling out unethical behavior

Don’t:

Rationalize the behavior just because you’re afraid of having a tough conversation

Go straight to your boss or HR unless the situation is severe — try talking directly to your colleague first

Make moral accusations — ask questions and treat the initial conversation as information-gathering

Case Study #1: Test the waters before speaking up

Sharon Fritz* had been in her role as legal counsel at a software company for two months when she suspected a vice president was trying to deceive a new customer. Sharon and the vice president, Kim*, had had a conference call with the customer’s lawyer about the terms of a contract. “Because I was new, I didn’t follow everything that was said,” Sharon recalls. As a result, she followed Kim’s suggestions on how to draft the language. But when they were finalizing it, Sharon realized that one of the clauses was vague and open to interpretation, in a way favorable to their company. She decided to email Kim about the issue, then ask her about it at their next meeting. “Is this what you meant to do?” she asked. Kim told her yes; she had wanted the language to be vague. “She said it in a way that made me think she wasn’t open to hearing anything more about it,” Sharon explains. Afraid that an unpleasant confrontation would harm her new working relationship with Kim, she didn’t go any further. “It was clear what she wanted to do, and I didn’t think I was going to change her mind.”

But Sharon was worried that when the customer got the first invoice, things would blow up, and she was right. A month after the contract was signed, the CEO called her into his office and explained that the customer was upset about the invoice and felt deceived. Sharon explained what had happened. The CEO told her that wasn’t how their organization did business and asked her to push back in the future. “He knew that [Kim] was tough and understood why I hadn’t stood up to her,” Sharon says. But she still felt as if her reputation had been damaged and regretted not saying anything. “It was valuable lesson for me. If the same thing happened now, I would just tell her, ‘We can’t do that’ and give her alternatives,” she says.

Case Study #2: Stand your ground when necessary

As an HR director at a large global company, Carla Santos* was often privy to sensitive information about employees. So, when one of the company’s executives became severely ill, she wasn’t completely surprised when a relative reached out to explain the situation. Unfortunately, however, this put her in a tough position. “I possessed medical information which typically an employer doesn’t have access to,” she explains. “The executive team realized that the family had confided in me and they were very interested in finding out the extent and gravity of the illness,” she says. But she didn’t feel comfortable violating the family’s trust by sharing the information. She knew that keeping quiet might negatively affect how her bosses perceived her, but that was a risk she felt was worth taking.

“I put my foot down and simply said that I would only share my own observations as a bystander,” she says. The decision was driven not only by her personal values but also her concern that the organization could be sued should the private information have any impact on the employee’s salary, benefits, promotion potential, or future employment.

As she suspected, her stance did have consequences. Her boss and one member of the executive team “became much more guarded” with her. But she still has no regrets: “I knew I was doing the ethical and legally correct thing.”

*Names and details have been changed.

The U.S. Can’t Count on Technology to Revive the Job Market

Job recovery after the 2007 recession is happening, but slowly, and wage growth is still anemic. Apart from the effects of the recession, there are concerns about the future of employment in the United States. I and others believe that the recession may have precipitated or accelerated certain long-term changes in employment patterns that will mean slower job creation, lower total returns to labor, higher skill requirements, and issues with income inequality. These have multiple causes including the shift of the economy to services and information-intensive activities, productivity growth, the appearance of new products and services, demographics, and continued offshoring that now includes services ranging from call centers to medical procedures.

The declines in manufacturing jobs during the downturns of 2001 and 2007, which totaled over 5.8 million, were the largest in U.S. history. Some were due to layoffs caused by the global recession and slowing of manufacturing exports, which constitute around two-thirds of U.S. manufacturing output. Many were due to increased imports and offshoring to low-cost locations. Thanks to the global recovery, about 900,000 have reappeared, and some more will, resulting in a recovery of probably around 25% of the recent losses. The United States remains the world’s second-biggest manufacturing power after China overtook it only three years ago. But the manufacturing jobs lost in labor-intensive sectors will not return to the United States in the foreseeable future.

Technology to the rescue? Some have pointed to 3-D printing as a road to a manufacturing renaissance. There are indeed many interesting applications in niches like prototyping, prosthetics, customized consumer products, jewelry, and even some industrial components such as turbine blades. But like craft production, the economics don’t work out for even modest production volumes. The aggregate impact on jobs and revenues will not be noticeable in the context of the huge U.S. economy.

One of the promising areas supported by technology is at the intersection of the internet and online technologies with the physical world: the “internet of things” (IoT). RFID tags were the first wave of IoT implementation and are already playing a large role in locating inventories, vehicles, people, and assets. Home automation, autonomous vehicles, drones, smart environments, and smart infrastructure are all potential growth areas.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

But IoT activities also are not likely to give manufacturing a significant boost in the next 10 years. The effect on jobs is likely to be gradual and subject to importing and offshoring. On the service side, the installation and maintenance of new systems in roads, power grids, and buildings (including homes), is likely to create jobs. However, the rate depends on investments and there may be negative effects as some jobs, like those of meter readers, are replaced by automation.

A shift in information-intensive services. Most jobs in the United States in the future will come from services as they already do. For instances, the aging of baby boomers is predictably driving the growth of health-care-related occupations. But there is a complicating factor: the growth of information-intensive services relative to physical services. Services growth and the decline in manufacturing jobs and GNP share over the last 70 years have been explained by the higher relative increases in productivity in manufacturing. Now within services we are seeing a shift from physical services (like transportation) to information-intensive services (like financial services and digital-content delivery). In the latter, new technologies are clearly leading to increases in productivity. Will that mean a decline of jobs in those sectors as well?

Not immediately and not everywhere. First of all, it turns out that the productivity explanation for sector trends is incomplete. Relative productivity growth initially causes growth in emerging sectors as prices drop and nascent demand grows. That happened to manufacturing up to the 1930s; then, with maturing markets and slower demand growth, continuing productivity increases led to the long and continuing decline in manufacturing employment.

Today, technology-driven productivity and innovation are still leading to growth in new information-intensive sectors. Consequently, information-intensive service jobs overtook physical service jobs in both numbers and wages after 2001. But it is possible that there will be job declines in information-intensive services in the future. This is already the case with some sectors: travel agencies, mail services, and music distribution come to mind. Occupations in sectors like publishing and clerical processing are also seeing low growth or declines. Basic financial services and content management could follow soon. Knowledge-based services will be at risk as well.

All this means net job-creation rates will not return to the levels of the 1990s in the near future. However, the rates at which labor participation (working-age people seek work) and the size of the labor force are growing are also slowing with an aging population and slower immigration. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) forecasts that the U.S. labor force will grow by about 8.5 million between 2012 and 2022, while the number of jobs will grow by about 15.6 million. The BLS warns against using these forecasts to infer employment rates, but the implications are obvious.

A skills shortage? Now it is possible that while jobs will be available, there will be a lack of people with the skills needed to fill them. For example there is still a demand for nurses being filled by foreign sources, though the influx has slowed since 2010. The shift to information-intensive sectors and the industrialization of services will require a more technically trained workforce. The same shifts will also threaten many routine white-collar jobs with automation and offshoring. This is especially an issue for aging countries where many skilled workers will retire in the coming decade.

To reiterate: jobs will come from services. The brightest spots are health care and construction, which also have high pay scales and lower barriers for some roles. Some concerns include the effect of continued industrialization on white-collar and pink-collar jobs. Brown-collar jobs (in physical services, warehousing, freight, and transportation) seem safe for a while, but automation is a potential if distant threat. In all, barring another global recession, it appears that unemployment is likely to drop steadily for a decade or more simply because of a smaller U.S. labor pool. But without decisive government action, wealth distribution will remain a problem.

Imagining a Smarter Future with the Industrial Internet

This is sponsor content – insight from GE.

The big unifying theme of this year’s International Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas was the Internet of Things (IoT). From BMW’s self-driving car to smart door locks and bells, and Wi-Fi tea pots, there were hundreds of exhibitors who presented their IoT-ready technology.

The IoT is ultimately about connecting devices to people, and allowing them to remotely control and monitor their thermostats, lighting, air conditioners and other appliances.

But there’s another, arguably deeper change taking place: the Industrial Internet. It’s less about remote control and more about machine intelligence and allowing things like wind turbines, locomotives and jet engines to talk and understand each other. This dialogue will allow these “brilliant machines” to work better together, optimize production and reduce unplanned downtime.

GE has been developing Industrial Internet software and applications for several years, and spent more that $1 billion to launch its global software center in San Ramon, Calif.

Last fall, the company opened Predix, its software platform for the Industrial Internet, to outside developers like Japan’s SoftBank Telecom, which took the first license in December.

The Industrial Internet could add $10 to $15 trillion to global GDP in efficiency gains over the next two decades. GE estimates that convergence of machines, data and analytics will become a $200 billion global industry over the next three years.

The Industrial Internet is already powering an American railroad as well as a South African platinum smelter. Take a look at a handful of examples.

American pipeline operators are investing up to $40 billion every year to maintain, modernize and expand their networks. Intelligent Pipeline Solution combines GE software and hardware with Accenture’s data integration expertise to allow customers to monitor their networks in almost real time and streamline their operations.

GE engineers and scientists are working with the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and Southern California Edison on a software system that could simulate and control the grid in real time, and predict and reduce outages.

GE’s Mine Performance system is helping the South African platinum smelter Lonmin to monitor and evaluate production. The gathered data allowed Lonmin to increase throughput in the section that feeds the furnaces with raw material by 10 percent.

GE’s SeaLytics BOP Advisor allows drilling crews to monitor the health of the components of blowout preventers siting atop new subsea wells and determine how many cycles they have gone through, what needs to be fixed and when. “When there is a problem, the drilling contractor will know within seconds,” Judge says.

See how GE can give you the edge: gesoftware.com

Making Appointments Fast and Easy Must Be Health Care’s Top Priority

I go to a lot of health care conferences and of late there’s a seemingly obligatory slide that crops up in nearly every PowerPoint. It’s a now-iconic image of a triangle divided in equal parts and labeled as follows: “improve the patient experience,” “improve the health of populations,” and “reduce the per capita cost of care.” This is health care’s “Triple Aim” and it is definitely trending. The framework, introduced by Dr. Don Berwick and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement back in 2008, proposes that in order to bring about the change we seek in our bloated health care system we must “simultaneously” pursue these three aims.

I must confess that I’m not a fan of the Triple Aim. It’s not that I don’t believe those three outcomes are vitally important. (For the record, I also believe in motherhood, apple pie, and the Stars & Stripes). I just don’t believe it’s possible to aim at three things at once. As a manifesto or creed, it’s inspiring. As a roadmap, it’s a bit hard to follow.

A more effective approach to change, I’d argue, is the one taken by Paul O’Neill back in 1987 when he was first appointed CEO of the aluminum giant Alcoa, a company that manufactures everything from the wrappers of Hershey Kisses to the bolts on satellites. As New York Times reporter and author Charles Duhigg recounts in his bestseller, The Power of Habit, accidents were commonplace at Alcoa, as they would be at any company in the business of handling molten metal on a regular basis. But the company’s safety figures weren’t bad – in fact they were better than their competitors. Nevertheless, O’Neill stood up in front of his investors that year and declared that the company would focus its entire strategy on bringing workplace injuries to zero. “If you want to understand how Alcoa is doing, you need to look at our workplace safety figures,” he argued. No talk of profits, opening new markets, or any of the usual crowd pleasers. Everyone thought he was nuts.

By the time O’Neill left Alcoa in 2000 to become Treasury Secretary the company’s market cap had increased by $27 billion and by 2010 not a single employee day was lost to workplace injury at 82% of Alcoa locations.

So what happened at Alcoa?

O’Neill had located and had the discipline to focus on what Duhigg calls a “keystone habit,” a deep organizational vein that, once tapped, has the power to drive other downstream improvements as it reverberates through an organization. In the case of Alcoa, once employees were asked to suggest ideas for safety improvement they began to surface other issues that had been buried. The rising tide of a more open, problem-solving culture helped raise all of Alcoa’s boats – and profits.

At my company, athenahealth, we are big believers in focusing ourselves and our clients on keystone habits and corresponding “sentinel” metrics. Our corporate scorecard, for example, is a waterfall that begins with workforce stability — over 17 years, we’ve found that our success depends on focusing first on managing voluntary turnover, ahead of all other traditional performance measures (including the ones our investors care about). Any spike in voluntary turnover is a canary in our coalmine and raises an alert that we take very seriously.

So, what should health care providers focus on as their keystone habit? For my money it’s patient access – making it as easy, quick, and worry-free to get an appointment with a provider as it is to get into a restaurant via OpenTable. Because, let’s face it, that is not our experience today. A 2013 Commonwealth Fund study of wait times in eleven countries found that 26% of U.S. residents waited six days or more for an appointment when they were “sick or needed care,” worse than eight of the other countries. Even the UK ranked higher, giving lie to the oft-heard refrain here that “we may pay more but at least we can get an appointment when we need it.”

But why, you might ask, should providers focus on access before quality? Because, as a recent Advisory Board study on “New Consumer Demands” pointed out, comprehensive measures of quality remain elusive at best. While we’re making progress with the shift to managing the health of populations, we still have limited ability to measure quality outcomes, limited physician consensus on what to measure, and limited ability to predict the drivers of quality. And, as consumerism explodes in health care, the reality is that patients tend to assume quality. As one health system CEO put it, quality is just “the cover charge.”

In that same study, however, patients consistently rated access and convenience higher than quality and other attributes when deciding on a primary care physician. In fact, six out of the ten things they cared the most about were tied to access, with the top one being, “I can walk in without an appointment, and I’m guaranteed to be seen within 30 minutes.” If that sounds like what you’d expect from a retail clinic, it should come as no surprise. Consumer expectations around convenient access to care have risen in sync with retail clinics, which have doubled in number in just the past three years.

When provider organizations make it a habit of opening their schedules and committing to same-week-or-sooner appointments other good things can happen. Appointment types can be simplified and streamlined, driving other opportunities for process improvement and efficiency. Care is more likely to be directed as appropriate to lower-cost providers and nurse practitioners or even to virtual consults, cutting costs and eliminating unnecessary care. And, most important, physicians can be freed up to see the sickest patients when they need to be seen.

In a recent New Yorker article about unnecessary care, Atul Gawande tells the story of an elderly patient who had been hospitalized after a fall with a contused kidney and a compression fracture. After being discharged, the patient was in pain and called his family physician for help. Five years earlier, Gawande says, the patient would have been told the doctor’s schedule was full and sent to the emergency room where he’d be re-admitted with a battery of unnecessary tests, MRIs, and more before being sent home with thousands of dollars of bills. Instead, the patient got in to see his primary care physician the very same day. The result was no hospitalization, no extra tests, a few pain meds, and no more than a hundred bucks in additional cost.

And so, I tell my clients when they’ll listen, patient access is worthy of your focus. Being best in the world at getting your patients in for care quickly when they need it can lead to being best in the world at other good things. Some don’t buy it, or have other priorities that seem right for their practices, which is fine by me. As long as they pick one thing (not three) to focus on relentlessly, and then test and learn their way forward from there.

Is Your CEO’s High Salary Scaring Away Customers?

Babo Schokker

Let’s say you’re in the market for some new towels. Nice towels, oversized and made with 100% Turkish cotton. They’re priced below your budget and in stock at a well-known retailer with both brick-and-mortar and online stores.

So far, so good. But what if you were told that the retailer pays the average employee $22,400. Its CEO, $24 million. That’s a ratio of 1000 to 1.

How do those towels sound now?

Currently, companies aren’t required to disclose their CEO-to-worker pay ratio (in the U.S. specifically, the provision of the Dodd-Frank Act calling for such disclosures has yet to be adopted by the SEC). At the same time, research is beginning to peel back the layers about what the general public knows about executive compensation — and all indications are that we’re woefully ignorant. For example, people drastically underestimate the compensation difference between average workers and Fortune 500 CEOs; globally, they say their ideal pay ratio for CEOs to unskilled workers is around 4.6 to 1. According to the AFL-CIO, the actual number is closer to 331 to 1 in the United States (most other developed countries have lower ratios than the U.S., but are still higher than the ideal).

It’s one thing to ask whether people are aware of the realities of these ratios, however. It’s quite another to predict whether their behavior will change based on that knowledge. If companies and countries were more transparent about salary, would it really have an effect on how people view the company — and, by extension, will it change whether they buy what it sells?

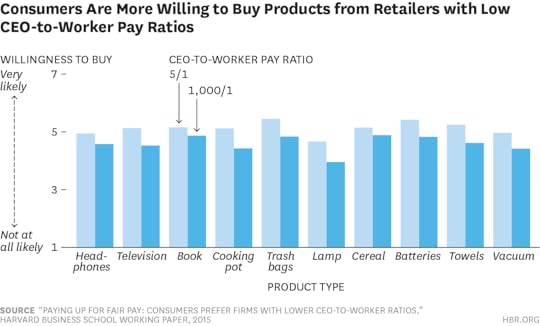

The answer, at least according to a new working paper, is “yes.” Consumers report being more likely to buy from companies with CEO-to-worker rations closer to what they deem fair.

Bhayva Mohan, a doctoral student at Harvard Business School, along with professors Michael Norton and Rohit Deshpande, set up several experiments to gauge consumers’ willingness to buy products when equipped with knowledge about the CEO-to-worker compensation ratio of the company selling them.

Which brings me back to the towels.

In the first three parts of the study, the researchers asked respondents (whose numbers ranged from more than 400 in the first experiment to between 100 and 160 in the second and third) about their willingness to buy a towel set under different conditions. Some were given a CEO-to-worker pay ratio of 1,000 to 1 (the estimated ratio at Walmart, given the information available, though respondents weren’t told this); others were given an ideal ratio of around 5 to 1 or a reality-based one of 60 to 1 (the estimated ratio at Costco); and in the third study, they were given options of comparing retailers with high and low ratios.

Across the board, people were more willing to buy from the company with the lower pay ratio, and more than 30% said they would pay more for the towels when given the option of two different companies with two different compensation ratios.

But the researchers knew that there could be a handful of ways a low ratio could backfire, too. For one, knowledge of the ratio along side of certain types of products could indicate a lower quality. It might also indicate the company is too warm and fuzzy, and thus seen as less competent. Finally, different political and economic beliefs among consumers could also change their willingness to buy.

So the researchers then tested against these assumptions, too. First, they found that the type of product didn’t much matter — the 151 people in this experiment were still more likely to buy from a company with a lower pay ratio.

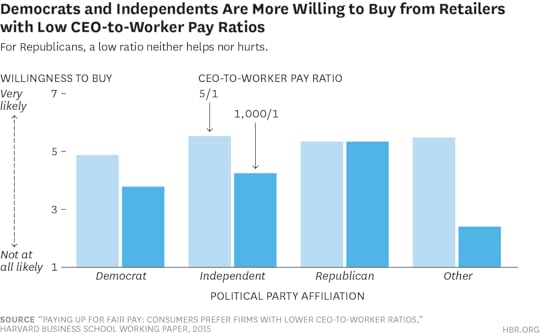

Then, in a second test, they found that perceptions of warmth did not dissuade people from preferring the low-ratio retailer. Finally, in another test, which involved more than 250 respondents, they found that both Democrats and Independents responded positively to a low ratio. Republicans were indifferent. (The people who answered “other” did not provide additional information, and were about 4% of total respondents.)

These tests led Mohan and her coauthors to conclude that an egalitarian compensation strategy “increases positive perceptions of most customers without harming perceptions of other customers.” In other words, your more politically conservative customers won’t run screaming if your CEO is paid a bit less.

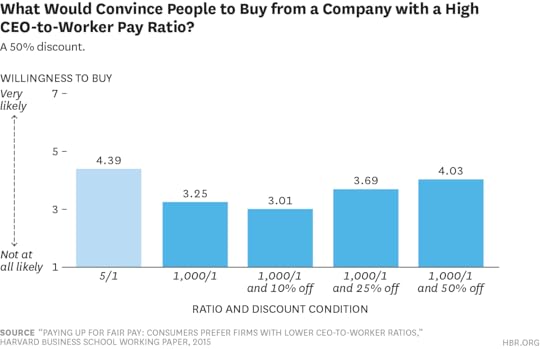

In addition, they tested whether discounts might help consumers overlook high CEO-to-worker pay ratios. They don’t, until you slash the price of an item by 50%, according to a survey of more than 350 people.

“We were surprised by how steep a price discount it took to make the products offered by high pay-ratio firm as appealing to consumers as the low pay-ratio firm,” Mohan told me over email.

So should companies be more strategic about making lower CEO-to-worker pay ratios public? Transparency can be a tricky thing. While showing the work that happens behind the scenes can sometimes pay off, like in the case of travel sites that visually indicate they’re trying to find you the best possible flight, disclosure can also backfire. “When websites reveal their processes only to suggest poor options (say, an unattractive date), consumers react more negatively,” write Mohan, Norton, and Deshpande.

Granted, these examples aren’t precisely aligned. But the authors conclude that their study suggests “that pay disclosure can have benefits,” and that companies with lower ratios compared to their competitors “may wish to begin to disclose this information voluntarily, as a means of garnering favorable consumer perceptions.” Mohan says the results “suggest that board executive compensation committees may wish to factor in the impact of CEO pay ratio on their customer behavior, particularly as the pay ratio disclosure law looms closer.”

While it’s still unclear, exactly, what the SEC’s timetable is, the sheer number of public comments on the Dodd-Frank provision — a full 25% contained the word “consumer” — indicate that “at the very least, “some investors looking through proxy statements might actually be affected by the disclosure when they go shopping.”

There’s also the issue of whether consumers will actually read proxy statements or annual reports for the ratio information — or if and how the media will publicize them, and for which companies. In addition, we know that sometimes what consumers tell us they want doesn’t perfectly predict behavior. That said, research has shown that adding a “fair trade” label to coffee resulted in a 10% increase in sales compared to a placebo label, so the effects of a “doing good” indicator aren’t far-fetched.

Mohan also acknowledges that different aspects of branding could influence people’s willingness to buy, something the researchers weren’t able to test in part because, of course, companies aren’t actually required to disclose their ratios. “For instance,” she says, “if a company is known for treating its employees well (i.e. by providing educational benefits), then a high pay ratio might not seem as unfair. Branding could absolutely make a difference.”

In the end, the researchers float an idea I find particularly appealing, even if it is a rather unlikely. Could disclosure have powerful results when it comes to gender pay inequality? Sure, there aren’t any laws in the U.S. requiring companies to state how much they pay men and women for the same work. But if a company had egalitarian salaries and sold oversized towels made with 100% Turkish cotton? Well then, I might suddenly be in the market.

June 2, 2015

Going on Vacation Doesn’t Have to Stress You Out at Work

Vacations are the things that dreams and cruise commercials are made of. Ideally, you come back refreshed, recharged and ready to go. But sometimes, the exact opposite is true. Who among us hasn’t said at some point, usually the day before we leave, “Trying to take this vacation is so stressful, it would have been better not to go at all!” Sometimes vacation stress is unavoidable, but most times it’s manageable if we’re simply more strategic. As the owner of a time coaching and training company, many of my clients tell me that after using the strategies below, they were able to take their first really refreshing vacation in years:

Initial Office Scheduling

One of the most important elements of reducing stress around your vacation is to decide well in advance when you’ll take time off. This gives you the opportunity to protect the time before and after your holiday from too many commitments. It also gives you the ability to make thoughtful choices as you pull the details of your trip together. Having lead time reduces stress to such a degree that one of my time coaching clients who does high-end travel planning requires at least three months of advance notice.

Once you know that you want to take a vacation, immediately block out those dates on your calendar as “out of the office.” It’s best to not make plans for any scheduled items like conference calls while you’re traveling. This way, the only work activities that you might end up doing during your vacation are the truly unexpected and urgent ones. Sure, you may have to check in on one or two things while you’re away — life happens — but you should avoid having to do your regular work during your time out of the office.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Managing Stress at Work

Managing Yourself Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Although it’s tempting to pack in as many meetings as you can before and after a trip, you’ll end up with better results by creating a buffer around your vacation. Set aside a few days before you leave to wrap up projects, take care of important e-mails, and attend any truly urgent meetings that pop up. Reserve at least the first day that you’re back in the office to get your head back into work and clear out your inboxes. It’s the office equivalent of getting your suitcases unpacked and your home back in order promptly instead of staying half unpacked for days or weeks on end.

Initial Travel Planning

How you structure your trip also has a significant impact on how refreshed you’ll feel when you get back. I recommend taking at least a half a day off of work before you leave to give yourself some margin for any final packing details or errands. When you originally purchase your flights, it’s worth spending the extra money to travel at reasonable times. Having to get up at 3 a.m. to catch a flight will not put you in a good state for your travels, and being sleep deprived makes it more likely that you’ll get sick. And since you planned well in advance, you’ll be able to find more affordable flights.

As you plan activities, don’t just think about what you want to see or do, but also think about the sort of experience you want to have. Just because you’re in Paris for the first time doesn’t mean that you need to go to every museum on the map. You may find you feel much happier — and more refreshed — by spending time at a few important spots and then giving yourself the luxury of sitting at a café for a few hours or taking a leisurely stroll.

If you’re traveling with children, focus on simplicity. Especially at younger ages, they’re quite content with a pool to play in, and with being unrushed. Plan for everything to take longer than you’d expect, and relax into the fact that you’re on vacation, so that’s just fine.

The Week Before You Leave

If you plan on taking a substantial vacation, start packing — or at least running errands — early. I find that blocking out time the weekend before the final week of work dramatically decreases the amount of last-minute trips to the pharmacy or the dry cleaner’s. Also, coordinate with your colleagues so that everyone has clear expectations on what you will and won’t be doing while you’re out of the office. That could mean giving others the authority to make decisions on certain projects, or letting them know that in specific situations they should contact you.

Use your “Out of Office” message on your e-mail and phone wisely. I like to state that I’m out of the office until X date and that I will return messages as promptly as possible after that time. That sets the expectation that I won’t reply while on vacation and also that it may take a few days after I return to the office to reply. Additionally, if you start your out-of-office auto-response a day before you actually leave, it’ll be easier to extract yourself from the office on time, as you’ll be able to focus on what’s most essential during your last day in the office.

The Week You Return

To maximize the relaxing benefits of your vacation, have a good re-entry plan. This can include arriving home a day early — or at least earlier in the day — so that you have some time to unpack, do laundry, and get a good night’s sleep. This also gives you time to make a plan for the coming day, so that you have a clear sense of how to approach your first day back in the office. Finally, instead of focusing on the fact that you’re no longer on vacation, think about how grateful you are for the time you had away. Gratitude creates joy that can carry you through the initial shock of going back to “real life.”

As you’re planning your next getaway, these strategies can help make it truly refreshing.

It’s OK to Move Down (Yes, Down) the Value Chain

Leaders of many companies — in industries ranging from contract manufacturing, and software services to consulting and health care — tell us the same thing: “We want to move up the value chain.” This seems to make a great deal of sense: Moving to higher- and higher-value work (from the customer’s perspective) makes it possible to command a higher margin. Moreover, customers often see this higher-value work as more “strategic,” which allows its provider to move from being a commodity supplier to a trusted advisor.

But managers should think twice before making this leap: Instead of accepting the conventional wisdom, they should seriously consider following those companies that are taking a different path and moving down the value chain. Why do so? Because it can

make your own operations more efficient

lead to significant growth

create the opportunity to invent new operations

defend against “attack from beneath”

and maintain your reputation for ethical operations.

Let’s look at each of these reasons.

Increasing efficiency. As organizations gain increasing insight into their own operating models and supply chains they are coming to appreciate the true cost of supposedly “low-value” suppliers. One such customer is Morning Star, a world leader in the production of industrial tomato paste. Traditionally, it trucked tomatoes to its processing facilities in California and then converted them into tomato paste. It had focused on operational improvements inside the proverbial four walls of its factory — things like more efficiently heating and cooling the tomatoes and developing novel ways to pack the paste for shipment to customers.

However, as the marginal returns to these improvements decreased, Morning Star’s leaders realized that the bottlenecks in the system were occurring, at least in part, from “low value” suppliers: the tomato growers. They weren’t planting or harvesting their crops properly, which resulted in foreign materials in the tomatoes delivered to Morning Star, slowing down its factory. In other cases, farmers didn’t plant tomatoes when they should have; as a result, supplies weren’t ready when the factory needed them.

Morning Star’s response: move into planting and harvesting. Farmers were still responsible for growing the tomatoes. But by taking over the steps at the beginning and end of that process, the company gained valuable control. Similarly, Nucor, the minimill steelmaker, decided to acquire David J. Joseph, a scrap-metal recycler, in order to secure supplies for its operations.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

Growth opportunities. In addition to improved efficiencies, moving down the value chain can open up new ways to grow. For Morning Star, an additional benefit of moving into planting and harvesting was the ability to offer its customers a greater variety of end products (by planting particular tomato varietals that yielded different flavors and tomato-paste consistencies) and ensure that they would be ready when customers wanted them.

Other examples are Indian IT companies such as TCS, Cognizant, Infosys, and Wipro. Traditionally, they have sought to move up the value chain by offering clients more-sophisticated, higher-margin services. They might support an insurance provider by providing technical support for the mainframe that ran its claims process and then, over time, look to add enhancements to the system or consult on the process.

However, moving down the value chain — taking on claims processing and call centers to answer customer questions — made it possible for a customer to outsource the entire claims process. Owning that entire process meant that the outsourcer not only sold more business to the customer but also could provide it with greater value by identifying challenges in processing and then incorporating the need to address those issues into the technology roadmap.

New operations. Moving down the value chain can lead to the invention of entirely new operations. Fashion apparel is an excellent example. By the late 20th century most retailers designed the clothes that they sold and outsourced their manufacture to others’ factories in low-cost parts of the world. This often meant lead times of more than nine months. Consequently, retailers were practically ordering the next season’s clothes while selling the current ones.

Zara, a retail chain that now has stores in 88 countries and belongs to Inditex, had a different idea. Moving into manufacturing allowed it to go from idea to clothes on the rack in weeks. Instead of having to guess the next season’s fashion trends, Zara could study what was hot and then make it, thus offering many collections each year rather than just one.

Defense against attacks from below. Where do new competitors come from? Often, they are the very firms that have honed their capabilities by operating in low-end markets or by performing outsourced work. As they learn the skills, they can move up the value chain themselves, biting the hand that fed them. Industries where this has occurred include personal computers, bicycles, software services, and musical instruments.

To prevent this from happening, you might want to retain, rather than outsource, capabilities and refrain from training suppliers that could turn into future competitors. This will make the option of investing in upstream operations far less attractive to them.

Ethical supply chains. Many companies now have supply networks that are so layered, dynamic, and complex that even they don’t know who many of its members are. This makes it extremely difficult to ensure that steel in cars didn’t originate from appalling shipbreaking operations in Chittagong, Bangladesh, working conditions in Asian suppliers’ plants are safe, the Latin American farmers who supply an agricultural commodity such as coffee are paid fairly, and the contract manufacturers’ factories in China aren’t major polluters.

While we don’t suggest that companies bring such operations in-house, they can bring them closer. For example, Pactics, a Cambodia-based supplier of microfiber, guarantees customers that its offerings are produced ethically. It does this by either producing the item itself or delving into the details of sub-suppliers’ operations.

Starbucks has taken a similar approach with its Coffee and Farmer Equity (CAFE.) standards, which provide guidelines for suppliers and provide third-party oversight that the standards are followed. Such strategies protect a company’s brand and reputation.

Moving down the value chain may seem like a crazy idea. But it might actually be the smartest way you can deliver more value to customers, expand your business, and protect it from attacks.

What It Was Like to Be a Manager in Ukraine

Most of the world views the turmoil in Ukraine as a geopolitical and humanitarian catastrophe. In my former position as Managing Director of Philip Morris Ukraine where I was based from January 2012 until February 2015, I was forced to see it as a business crisis that threatened our people, operations, and bottom line. When peaceful protests turned into violent clashes between demonstrators and police, and fighting engulfed the nation, every rule of normal business collapsed. Our supply and distribution lines were impeded; we lost market territory to war and annexation; we had to manage the impact of military mobilization of our workers, and we needed to relocate or redeploy almost a hundred employees and their families.

In that confusion, I had two clear priorities: to secure the safety of our employees at all costs; and to maintain our operations to whatever degree possible.

I tried to give my team in Ukraine this perspective. It is easy to feel anxiety, responsibility, and even shame when things go wrong in a business. But you can only make good, prompt decisions that move the organization forward if you have enough detachment to view the confusion in a clear-eyed and objective way. Indeed, Ukraine’s troubles offered an opportunity to build the leadership capacity of my management team.

Shift from “fog fear” to “tent time.” A crisis breeds pervasive dread. I call this the “fog fear” and I’ve seen it paralyze organizations. The antidote is to help your people feel safe, secure, and supported.

Our behavior as the management team mattered a lot. The eleven of us aimed to be calm, decisive, and hands-on captains to the 200 people in our office, the 450 others spread around the country, and the 750 in the factory. We kept our own feelings under control as we tried to be emotionally “present” so that people could discuss their fears and worries with us. We assured them through our actions that our most important priority was to keep them and their families safe and, to that end, instituted nightly head counts and safety reports during the worst of the crisis. Throughout it all, we provided constant communications with status updates, decisions, changes, and guidelines for how to act and react appropriately to the level of crisis at hand.

Just as critically, we supported each other by spending lots of time together, sharing thoughts, and laughs. We called this bonding “tent time.” The expression came from an arctic adventurer who had told us that his team grew closer through the long hours they spent together in their tent at the end of every day. The more tent time we had in Ukraine, the closer and calmer we became as a team.

Become a “what if” machine. A crisis throws predictability out the window and forces everyone to adopt new ways to run the business. To effectively manage that chaos, it’s necessary to develop the habit of continuously processing new information, playing out “what if” scenarios, calculating risk factors, and running through checklists. With each new development, we learned to assess what it meant by asking, “What is in front of us and what are the consequences?” Through that discipline, it became almost automatic to imagine options, craft emergency plans, and identify trigger points to propel us into action. We knew what we would do if our factory was shut down, our phones stopped working, or the fighting intensified and evacuation was necessary. It was critical to make decisions quickly and avoid becoming stuck.

Avoid secrecy. During a crisis, it’s easy for a senior team to huddle in the war room while making important decisions. But while leaders need time to absorb new information, assess priorities, and have candid conversations it is just as important to be out with the troops and “leading from the front.” I helped my team understand that increased communication is a must during a crisis. By nature, people are less confused and prone to panic when they understand what is going on. Tone and body language are also important because everyone is hypersensitive to nonverbal clues. Some leaders sugarcoat reality or take the corporate line. We found that it helped to consistently downplay expectations and confront brutal facts so people knew they were always getting straight talk.

Rely on others as much as possible. To manage a crisis, the leadership team must function at its highest capacity. Each person on my team had different skill sets and personalities. Depending on the circumstances, different people came to the front to lead. Our Director of Information Systems became a technological tactician who worked out a plan in record time to allow us work remotely in the event that fighting encroached on our offices. Our Director of Operations led our special situations management team to respond to threats and constant changes. Others offered psychological support to employees experiencing breakdowns, developed contingency plans, or found temporary shelter for those whose homes were threatened. I never appreciated the diversity of a team more, and our tent time helped us benefit from our collective talents. Disagreements and debate was encouraged because we needed a variety of perspectives to surface problems and good ideas. The cohesion of our team made it safer to discuss difficult issues, innovate solutions, and take risks.

Many foreign companies decided to write off Ukraine. Our company achieved exceptional results – maintaining market share, reaching sales targets and accomplishing the majority of our business objectives – while serving as a beacon of stability to our customers and the people of Ukraine, especially during the most difficult eight months of the crisis until September 2014 when the Minsk Protocol temporarily ended hostilities.

We live in a world where crises are likely and leaders must prepare to face the unexpected. It is important to take advantage of every opportunity, even catastrophe, to learn and grow.

Customer-Centric Org Charts Aren’t Right for Every Company

The new conventional wisdom on corporate structure is that companies can do better by organizing themselves around customer groups. The logic sounds compelling: A customer-centric structure, as the approach is known, can help a company understand its customers better, develop deeper relationships with them, and improve customer satisfaction. Some 30% of Fortune 500 firms, including Intel, Dell, IBM, and American Express, are already on board, and the numbers are growing all the time.

But customer alignment doesn’t work for everyone. Cisco and Xerox, for example, have seen poor results. And even when it does work, a company can go through years of poor performance before the benefits kick in. Is there a flaw in the logic?

Our analysis of Fortune 500 firms shows that the strengths of the strategy are real: Customer-centricity does allow divisions to focus on specific customer segments, and this narrower focus increases their knowledge of those groups. But it introduces greater complexity into communication and decision making and leads to duplication of certain functions across divisions. Details of the competition and of customer segments determine whether the positives outweigh the negatives, and years can pass before customer-centricity bears fruit.

We’ll show how companies can use our findings to estimate whether — and when — a customer-centric structure is likely to work. But first a little background.

The idea that companies should adopt customer-centric structures has been around in both academia and practice for a while, but it was George S. Day of Wharton who reignited interest in the concept. In his 2006 survey of U.S. managers, he said the proportion of U.S. firms with structures organized around customers would grow from 32% to 52% as firms raced to build customer-centric organizations, and he interviewed companies including IBM and Systems Group that had announced customer-centric restructurings. He also emphasized in a 1999 book that “the wrong structure can doom all other market-driven initiatives in the organization to failure.”

A good example of customer-centricity is Tumi, the innovative U.S.-based maker of suitcases, which has been customer-centric since its founding in 1975. Each division focuses on one customer group — premium customers or young adults, for example — and, through research, designs products for that segment. Surveys commissioned by the company show that it does a good job of satisfying customers by matching their needs.

Intel, whose top-level divisions had been organized around product groups or functional areas, adopted customer-centricity in 2005, and its improved knowledge of and commitment to customers has resulted in greater customer satisfaction. Dell, which adopted customer-centricity in 2009, has seen positive results too: After aligning its corporate business units around customer groups, such as large enterprises and consumers, the company learned to operate seamlessly in the new structure and improved its financial performance.

Examples like these, as well as the seemingly bulletproof logic of making customers’ needs central, have helped sell customer-centricity to many corporate leaders. And there’s no doubt that a customer-centric structure helps organizations amass rich depositories of customer knowledge and expertise and thereby uncover unmet needs.

But our research, conducted with Conor M. Henderson of the University of Oregon and Irina V. Kozlenkova of Michigan State University, tells us that there are situations in which discovering and acting on unmet customer needs either amounts to mere table stakes or contributes little to profitability:

Prevalence of customer-centricity and high competitive intensity. When competitors already have customer-centric structures or otherwise do a very good job of meeting customer needs, any one company’s customer-centric structure is less valuable. Customer-centric firms with many customer-centric competitors exhibited 11% lower performance than peer firms with product-centric structures. Moreover, customer-centric firms that operated in highly competitive markets had 69% lower performance, compared with product-centric peers.

Low industry profitability. When few customers value greater customization or responsiveness, the headaches of restructuring around customer segments aren’t worth the trouble. Customer-centric firms in less-profitable industries performed 20% lower than firms whose structures were not aligned with customers.

Take, for example, two exponents of the customer-alignment philosophy: the for-profit health-care company Anthem and software and services firm SunGard. Anthem implemented a customer-centric structure in 2008 when it was known as WellPoint and when few of its competitors had adopted the approach. It was able to use its new organizational structure to discover and meet new customer needs such as better quality of care, enhanced transparency, and lower health-care costs. Its adoption of customer-centricity yielded a 36% increase in return on assets over the four-year period after the restructuring. The company has maintained and still benefits from its structure, even though some of its competitors have adopted customer-centricity.

SunGard’s competitive environment was different. Its competitors, such as Affiliated Computer Services and Leidos Holdings, were already doing a good job of discovering and addressing unmet customer needs. Its 2002 restructuring offered little incremental benefit while adding cost and complexity. Its ROA dropped 81% over the four years after the restructuring.

There’s also a gray area in which customer-centricity provides significant advantages while simultaneously dragging down results. Tumi, for example, has recently struggled with the drawbacks of customer-centricity. With each division focusing on only its own customer segment, the structure appears to be poorly suited for generating widespread corporate brand awareness. Customer-centricity appears to be a reason for the company’s high marketing and coordinating costs: Its customer-focused structure has entailed a division of resources, capabilities, and people; raised organizational barriers to sharing and communicating; and led to greater complexity-related costs and losses of economies of scale. These high marketing and coordinating costs may be the cause of its problems today.

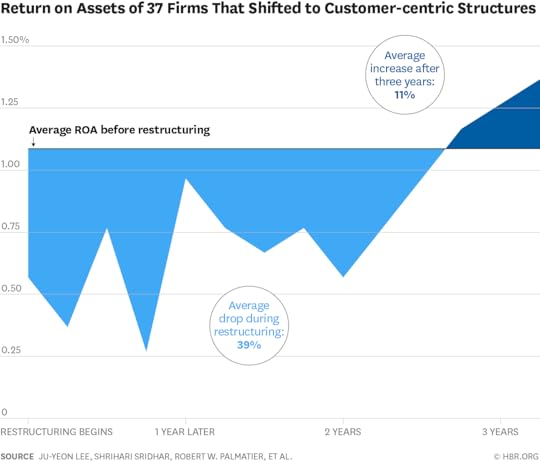

In cases where customer-centricity is an appropriate structure, we found that it takes more than two years after a restructuring, on average, for companies’ performance to exceed prior levels. During that period, performance typically deteriorates significantly as the firm incurs coordinating costs due to internal conflicts and confusions.

Among 37 Fortune 500 firms that went through customer-centric restructurings, the performance drop averaged 39% from companies’ pre-restructuring levels; it was only after 10 quarters that performance exceeded those levels — at which point it exceeded them by 11%, on average.

Before initiating adoption of a customer-centric structure, companies should look carefully at the extent to which this approach has permeated the competition. Firms should also gauge the industry’s competitive intensity and take a close look at their industries’ profitability. There are no simple rules of thumb for these assessments — every industry is different — but a predominance of customer-centricity, high competitive intensity, and high commoditization and a prevalence of low margins all suggest that restructuring around customer segments may not pay off.

And if executives determine that a customer-oriented restructuring is a good gamble, they should enter into the process with eyes wide open, establishing clear expectations that performance will sag before it rises.

In addition, CEOs and functional heads need to talk to each other about proposed changes in organizational structure. Top executives should get guidance from marketing, sales, and R&D before making structural-design decisions, and managers from those functions should weigh in on the harm that could be done by the greater complexity and duplication that are so often a consequence of customer-centricity.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers