Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1286

June 10, 2015

High-Tech Tools Won’t Automatically Improve Your Operations

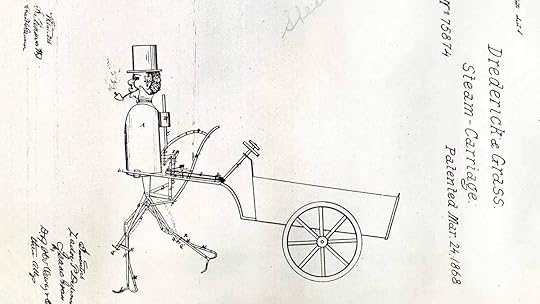

Advanced tools for creating and testing new products and the operations that will make them are all around us. They are not only changing the economics of innovation and operations, they are also pushing the frontier of what’s possible.

Airplanes and cars are designed, modeled, and simulated on computer-aided software before the first prototypes are tested. Complex architectural structures undergo virtual stress tests before concrete is poured. Engineers can “walk” through digital factories before workflows are finalized. The CRISPR tool, which has electrified the scientific community, lets scientists easily disable genes or change their function by replacing DNA letters; its many applications include the development of new drugs. And in a recent HBR article, my coauthor and I wrote about advances in running disciplined business experiments, assisted by complex analytical tools.

While it is encouraging to see this rapid progress, tools — no matter how advanced — do not automatically confer benefits on organizations. They must be integrated into systems and routines that are already in place. Tools are embedded within the organizations that deploy them as well as the people that use them. When integrated incorrectly, they can actually inhibit performance.

In my research, I have uncovered some pitfalls for organizations that adopt such tools and ways that they can avoid them.

Don’t use tools merely as substitutes. When new modeling and simulation tools became available, their proponents initially argued that substituting virtual prototypes for physical ones could save millions of dollars. Indeed, companies did save money with such simple substitutions. But they failed to address the bigger opportunities that such tools offered: fundamentally rethinking and reorganizing the flow of product-development activities. One manager explained this by using the analog of morning traffic. Even if he had a Ferrari, his commute wouldn’t be faster unless he could find a new route that took advantage of the car’s speed and acceleration. Similarly, companies can’t unlock the full potential of new tools unless they find new ways to operate.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

In a project with an analog chip company, I worked with senior management and engineering to find innovative ways to leverage detailed performance data of its equipment and the integrated circuits that it manufactured. We used the data to develop sophisticated statistical models of its manufacturing capabilities and embedded these models in design and simulation tools that were used by upstream design engineers. Previously, these engineers had to design with wide safety margins that ensured that their devices could be manufactured, which lowered performance and increased cost. Now, with manufacturing capabilities integrated in the design tools, they could tighten safety margins significantly. The result: higher performance and lower costs without lowering the manufacturing yield.

But it also required fundamentally new ways for design and manufacturing to work together. First, manufacturing had to collect and frequently update the data for the benefit of upstream design. Second, both had to trust that the models embedded in the tool were accurate and would not result in lower yields. Third, manufacturing had to immediately communicate and coordinate any changes, such as process tweaks, with other groups because its actions affected the tools that these groups used.

Build trust. In my research, I have observed that the rate of technological change often exceeds the rate at which people can change their behavior. That is, when the knowledge base of an organization depends on the use of particular materials and tools, engineers will not easily dismiss much of what they know; nor will they change how they work overnight.

In the chip company I discussed above, manufacturing was very reluctant to acknowledge that tighter safety margins in design tools would not affect production quality. To be sure, the company didn’t know what the overall effect would be, but the company’s CEO wanted to run some experiments because, if it worked, it would give them a performance edge over competitors. (Many competitors were “fabless” and thus didn’t have access to detailed manufacturing data.) Once the manufacturing folks saw the impressive results from some design projects, they were sold.

Similarly, when simulation tools were introduced to engineering organizations, people had trouble accepting the results of a simulated test when they had spent years or even decades learning from physical models. This led to bizarre outcomes: In one company, I found that the introduction of computer simulation tools ended up increasing overall product-development costs. Because people didn’t trust the new tool that was supposed to replace expensive prototypes, they ended up building more prototypes to verify that the simulations were accurate. In some cases, the skepticism was well founded because virtual tests were poor substitutes. But in many cases, management failure to build trust led to wasted resources.

Find new ways to create value. Advances in tools can open up new ways of interacting with partners and creating value. By putting analytics tools into the hands of customers, Google has changed the face of advertising. Apple’s app developer tools have turned many users into software suppliers and created a huge marketplace that Apple controls and benefits from. Indeed, new value can be created by findings ways that customers and users can play a more active role in innovation and operations. This is done by putting a company’s know-how into tools and empowering customers to design and even “manufacture” solutions for themselves, thus fundamentally changing value creation and capture. I’ve seen this in engineering and software industries, but new tools are now being adopted more broadly.

Credit Suisse created a platform through which customers can design their own financial products. By automating routine safety and robustness checks and shifting the design work to customers, the cost has dropped by approximately 95%, massively increasing profitability and freeing resources to focus on innovating instead of execution. More importantly, hundreds of unique products are generated each day, and the volume of trading on the platform has soared.

By rethinking how they have provided value to their customers, the bank and its customers are now creating solutions that didn’t exist before.

Advanced tools can transform the way you run innovation and operations. But it’s the way you manage the tools and the people that use them that will unlock, or hold back, their potential.

When Sales Incentives Should Be Based on Profit, Not Revenue

Most sales forces link some portion of salespeople’s pay to sales metrics. For example, they pay a commission on the revenues salespeople generate or a bonus for achieving a territory sales quota. This proven “pay for performance” approach motivates salespeople to work hard and drive sales results.

But today, companies increasingly expect salespeople to deliver not just sales but profitable sales growth. Logically, it follows that a sales force can align salespeople’s effort with company profitability goals by linking incentives to profit, rather than sales metrics.

When an industrial lubricants distributor started paying commissions on gross margin rather than on sales, for example, the message to the sales force was clear and the impact immediate. Salespeople curtailed price discounts and focused their effort on more profitable product lines, leading to accelerating margin growth. However, when a medical device company started paying commissions on margins instead of sales, constant change in product costs, distribution costs, product rebates, and portfolio rebates made it a nightmare to determine territory-level margins. The plan was abandoned after just one quarter.

To help you determine whether paying salespeople on profitability is something you should consider, start with two questions.

1. Is profitability strategic? Companies sometimes sacrifice profitability for reasons such as building market share, blocking a competitor, or gaining entry into a market. Consider paying salespeople for profitability only if profitability is a strategic goal.

2. Is profitability controllable by salespeople? Salespeople who sell a single product at a set price have no impact on the gross margin of sales; the way they increase profits is by selling more volume. Thus, there is nothing to be gained by paying on profitability; the result will be the same as paying on sales. Salespeople have the ability to impact gross margin when – 1) they can influence price and/or 2) they sell multiple products with varied margins. Paying salespeople for profitability only makes sense if at least one of these conditions applies.

If profitability is both strategic and is within salespeople’s control, then four additional questions can help you determine the best approach for using incentives to encourage more profitable selling.

3. Can you measure gross margin at the territory level? The most straightforward way to encourage salespeople to sell more profitably is to use the approach that worked for the industrial lubricants distributor–pay incentives on territory gross margin rather than sales. But as the medical device company discovered, measuring and reporting on territory gross margin in a timely and accurate fashion is sometimes more difficult than it seems. Even when information systems allow measurement, complex calculations can make it challenging to gain sales force understanding and acceptance of gross margin metrics. If you can measure and report on territory gross margin at reasonable cost, then pay on gross margin. But if the cost is too great, consider other options for using incentives to encourage more profitable selling (see questions 5 and 6).

4. Do you want to share profitability data with salespeople? If you can measure territory-level margins but want to protect the confidentiality of profit margins from customers and competitors, you may want to avoid sharing margin information with salespeople. Some companies have had success paying on margin proxies–artificially calculated margins that reflect the relative profitability of products, without revealing actual margins. Yet margin proxies still reveal a lot of information. If confidentiality is a big concern, consider other options for encouraging more profitable selling (see questions 5 and 6).

5. Do salespeople influence price? If the cost of measuring and sharing territory gross margin is too great, then linking incentives to average selling price is a good alternative for encouraging profitable selling when salespeople influence price. For example, an office products supplier had a commission plan with a multiplier linked to average selling price performance. Deals booked at more than 3% below list price earned the salesperson a base commission rate. For deals booked within plus or minus 3% of list price, salespeople earned the base commission rate times a 1.1x multiplier. For deals booked at more than 3% above list price, salespeople got the base rate times a 1.25x multiplier. The multipliers discouraged salespeople from conceding price in order to outperform on volume.

6. Do you want to drive sales of higher margin products? If the cost of measuring and sharing territory gross margin is too great in a sales force that sells multiple products with different margins, then paying on sales by product grouping is a good alternative for encouraging salespeople to spend time on more profitable or strategically important products. For example, a technology company created an incentive plan with two product groupings: “strategic products” (newer products with paramount strategic importance and an average 50% gross margin) and “core products” (older products with an average 30% gross margin). Salespeople earned a 5% commission on sales of strategic products, but just 2.5% on sales of core products. The commission rate differential encouraged salespeople to focus on higher margin products, thus boosting overall profitability.

Sales incentive compensation plans can play a key role in aligning sales force effort with company strategies. When profitability is a strategic objective and is also within salespeople’s control, a sales incentive plan that rewards salespeople for profitable selling can be an effective way to motivate achievement of company financial goals.

June 9, 2015

Companies in Happy Cities Invest More for the Long Term

Happy people work differently. They’re more productive, more creative, and willing to take greater risks. And new research suggests that happiness might influence how firms work, too.

Companies located in places with happier people invest more, according to a recent paper by Tuugi Chuluun of Loyola University Maryland and Carol Graham of Brookings. In particular, firms in happy places spend more on R&D. That’s because happiness, they argue, is linked to the kind of longer term thinking necessary for making investments for the future.

Chuluun and Graham wanted to know if the optimism and proclivity for risk-taking that come with happiness would change the way companies invested. So they compared U.S. cities’ average happiness, as measured by Gallup polling, with the investment activity of publicly traded firms in those areas. (Gallup asks respondents to evaluate their lives from zero to 10, with 10 representing the “best possible life.”)

Sure enough, firms’ investment and R&D intensity were correlated with the happiness of the area in which they were headquartered (view maps of average happiness, investment, and R&D here). But is it really happiness that’s linked to investment, or could something else about happier cities explain why firms there spend more on R&D? To find out, the researchers controlled for various factors that might make firms more likely to invest — like size, industry, and sales — and for indicators that a place was desirable to live in, like growth in wages or population. The link between happiness and investment generally held even after accounting for these things (though more so for R&D than for other investments).

The correlation between happiness and investment was particularly strong for younger firms, which the authors attribute to “less codified decision making process” and the possible presence of “younger and less experienced managers who are more likely to be influenced by sentiment.’” The relationship was also stronger in places where happiness was spread more equally. Firms seem to invest more in places where most people are relatively happy, rather than in places with happiness “inequality, or large gaps in the distribution of well-being.”

While this doesn’t prove that happiness causes firms to invest more or to take a longer-term view, the authors believe it at least hints at that possibility. It’s not hard to imagine that local culture and sentiment would help shape how executives think about the future. Just ask anyone who’s spent time in Silicon Valley. “It surely seems plausible that [happy people] would be more forward-thinking [and] creative and lean towards R&D more than the average,” said Graham.

If that’s true, it would bolster an already impressive case that happiness shapes how we work. But while much of the focus on workplace happiness concerns engagement of front-line workers, the link to investment is a signal that broader satisfaction matters too. At a time when companies are plagued by short-term thinking and are sitting on cash, happiness could be a missing part of the puzzle.

Even if the link between local happiness and investment isn’t definitive, Chuluun and Graham’s work is a nice illustration of the way geography can shape companies. And they are not the first to argue that location influences how firms think about the future.

In a 2007 Harvard Business Review article, Mansour Javidan reported on his research comparing a society’s “future orientation” to its level of economic success. He and his colleagues asked thousands of managers across the world how much they agreed with the statement: “More people live for the present than for the future.” Agreement was negatively correlated with competitiveness. The more a country’s managers reported that people lived for the present, the worse the society’s economic performance.

It’s easy to imagine how corporate short-termism and unhappiness reinforcing each other. Less optimistic, future-oriented, or happy places may deter investment. And lack of investment in turn gives people less reason to feel optimistic about the future.

The good news is that, while Javidan’s work found that societies varied in how focused they were on the future, most cultures agreed that people should care more about the long-term. “Because of those shared values, it is possible to inspire people to become more future oriented,” writes Javidan. For now, though, when it comes to resisting short-term thinking, companies in happier, more future-oriented places may have a leg up.

How Bayer Developed a Cross-Cultural Senior Team

For the last five years, Bayer has been quietly transitioning from being an international company to a truly global one. There is a difference, says CEO Marijn Dekkers.

“You are not a global company because you do business in 120 countries. You are a global company if you understand countries and customers so well that you are able to do business optimally everywhere. In a world where no one ever has a monopoly anymore, it isn’t about differentiating with a better aspirin. It is about a company’s ability to deeply build a profound affinity with a country – every country. That’s what being global means.”

Five years ago, Dekkers became CEO of Bayer. Since 2011, I have been working with him to further globalize BAYER’s management.

These efforts have, intentionally, been neither fast nor flashy. They are, instead, part of a serious, carefully paced effort to transform a more than 150-year old, mainly German-run company into a 21st century, truly global powerhouse. For the past three years, Bayer has invested time and money to carefully build awareness and skills across its global leadership on leading teams that are more culturally and gender balanced –and how to then use that balance for competitive advantage in the market.

Here’s a glimpse of what we did, how we did it, and some of the initial results.

“When we began,” admits Dekker, “we didn’t underestimate how hard it would be to shift the culture, but we did underestimate the base line attitudes from which we were starting.” Bayer’s capability of being in tune with its global markets was not optimized back in 2011.

The challenge for many executives sitting at corporate headquarters in Western countries is to build trust in locals who are faraway in very different cultures, like Brazil, Russia or India. It is so much more comfortable to work with someone you have known and worked with for 20 years who shares your nationality and language. To change that deeply and sustainably, you don’t use brute force, you have to do it gradually.

Setting the right pace is crucial. Bayer was smart to keep things slow and steady. To succeed sustainably, the speed of change has to be appropriate to the company’s cultural roots, its history, and its business context. Even if this opens companies up to criticism that they are not going far enough, fast enough. “We could have moved faster by force fitting,” says Dekkers, “but how intelligent is that? Our advice to others on this journey is: Don’t set overambitious goals. Don’t overstretch people too early, or you alienate your majority group, who in the beginning, were very skeptical. You have to think whether it’s the right thing for the people who are given the jobs, and the reaction of their colleagues when they get them. We resisted the short-term approach of hiring female talent from other companies, a decision that has gone over well internally. Promoting from within is less threatening to male managers than rushing to recruit a lot of women from outside.”

It was also helpful to bundle the topics of gender and nationality together. As in most companies, male managers were more ready to accept the business case for balancing the mix of nationalities than they were to accept the business case for gender balance. “It is more intuitively comprehensible why you want to get a local Chinese executive running China,” says Dekkers, “than to understand why you want a woman running Germany. And yet our customer base is a mix of women and men, as well as people from countries around the world. We needed both more women and a more representative mix of nationalities in management in order to better serve these consumers. Tying both topics together helped them reinforce each other.”

To communicate this through an organization of over 118,000 people, we began with what we called “strategic debates.” In these, senior leaders discuss both why balance is relevant to their business as well as how they can implement change. Almost 2,000 Bayer leaders have been actively engaged in these sessions, which equip managers to recognize a world full of cultural and gender differences and become skilled at understanding, celebrating, and using those differences to connect with customers and employees. Dekkers has insisted, and will continue to insist, that all Bayer leaders run this exercise with their teams.

“These discussions require serious time and focus,” comments Dekkers, “even though many executives already feel that they ‘get it.’ Like any other business issue, it can’t be delegated to diversity experts or HR. We framed the issue as a business opportunity, and, like any other opportunity, it requires thinking, commitment, and accountability from leaders. We made the rules of engagement clear from the get go: our efforts would be leader-led, strategically focused, and business-driven. Accountability for change sits with the people with the power to change the rules.”

So what are the results?

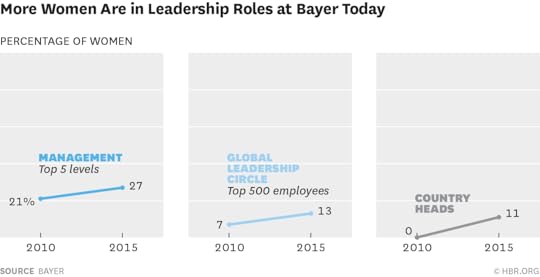

On gender, the balance shifted by 1.5% per year over the past four years. That was, says Dekkers, “about right given the existing talent bench.”

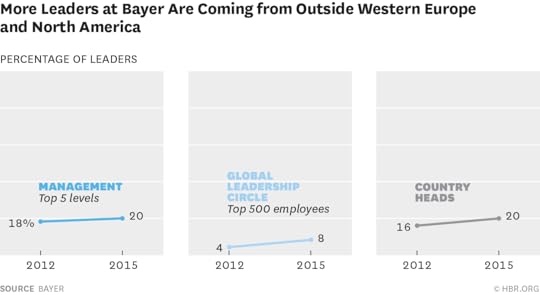

In terms of nationality, the tracking only began in 2012. It focused on measuring the share of managers coming from countries outside of Western Europe and North America. In the intervening two years, the trend was positive:

And again, these are mutually reinforcing, not mutually exclusive, goals. For example, the Country Manager in China is an Australian woman with Malaysian Chinese origins.

Dekkers is the first to admit that there is more work to do. Bayer’s Annual Report still has a picture of eight Western men on it. But now there is agreement and commitment to making the picture evolve. And Dekker adds that the picture also “reveals a smart commitment to resisting the pressure to catapult the wrong person into the role for the wrong reasons. Today, the talent bench is much more culturally mixed than it was. The current generation of Bayer leaders has no reservations about how important this is. They have helped to create this momentum.”

It’s still, as in most of the world’s companies, the beginning of a longer journey. Every company is competing around the same dual realities: globalisation and feminisation. Dekkers knows how completely the world has changed in a generation, and we are pleased to have been able to do our bit to help Bayer get ready.

As a research company, with the slogan “Science for a Better Life,” Bayer usually sees innovation as a scientific or technical breakthrough. Yet we think that the company’s approach to balancing the gender and cultural mix of its management is equally innovative.

Does Hardware Even Matter Anymore?

We are in the midst of a technological revolution that is every bit as profound as the impact of cheap computing power, but it’s subtler and harder to notice. It will ease the way for companies launching and updating digital products, but it presents steep new learning curves that companies will have to master if they are to be successful.

What I’m referring to is the migration of functionality from hardware to software. In more and more businesses, physical objects are no longer the primary basis for innovation and differentiation. They come second to innovations in computer code.

Managers are well aware that Moore’s Law, the idea that the number of transistors on a practical-sized chip doubles every 18 months, has brought us a bounty of cheap computing power, leading to smartphones, tablets, fitness trackers, cloud-based services like Facebook and Uber, and on and on. But I’ve found that they’re less cognizant of how software has transformed other fields that we traditionally think of as hardware-based.

Consider, for example, how we convert and control electrical power. Think of the cubes we plug our iPhones into, the sensors that control our heating and lighting, and the motors used in tiny disk drives and the giant traction motors in locomotives. Modern solid-state power electronics got started in the 1950s, but rapid recent progress in power semiconductors, new power conversion topologies, and methods for controlling electric motors has brought us a plethora of small, high-efficiency, low-cost, and long-lived electronics subsystems for motion control. For a few dollars, designers can easily connect a computer to remember the seat position in your car. They can also replace the hydraulic power steering with a more-efficient electric power-steering system, or for that matter control everything needed to make that car autonomous — all it takes is software.

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

The biggest benefit from this trend is that you can incorporate more sophisticated control regimes into products. Old-fashioned analog controls require tuning and are expensive to manufacture. Software control allows you to plug in control schemes that would be almost impossible to implement otherwise. I recently rented a Volkswagen Beetle, and I noticed that when I opened the door the window rolled down just a little bit, anticipating the air pressure buildup that would occur when I shut the door. I got a nice satisfying door slam, and afterward the window rolled up. That would be really hard to do with analog controls, but with software? Easy. That’s one reason high-end cars have as many as 100 microcontrollers and 100 million lines of software running them — to power what Toyota calls “hospitality features.”

This style of “more electric” control by software also means big gains in energy efficiency. With electric power steering you draw power from the engine only when you need it, not constantly as with a belt-driven hydraulic pump. One automotive engineer told me that mandated fuel-economy standards were forcing manufacturers to replace engine-driven mechanical and hydraulic loads with electric. Lost in the furor over the lithium-ion battery problems with Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner were the efficiency gains from the plane’s “more electric” architecture. Boeing substituted electrically operated subsystems for traditional hydraulic and pneumatic power in key subsystems like flight controls, the environmental control system, landing-gear retraction, and braking. Not only do these subsystems draw engine power only when they need it, but more electric means less weight from hydraulic lines and ducts. Of course it also means a lot of lines of software.

The rapid uptake of smartphones has enabled manufacturers to rapidly scale up the production of sensors — GPS sensors, accelerometers, image sensors, capacitive touch sensors, all kinds of devices that help us measure the analog world — and connect them to our electronic world, where they can control things on the basis of what we see, hear, or feel. The sophistication and efficiency of these sensors are advancing rapidly, as you might expect given that their makers are supplying them for the manufacture of 60 million iPhones and even more Android phones each quarter. So it has become really inexpensive to add sensing to all kinds of devices — rear, side, and front vision on a car; an accelerometer to monitor your clothes dryer. The most innovative applications are probably still to come.

Harnessing all this technology — the computing, the motion control, the sensing — poses a huge challenge, but rising levels of abstraction are giving product designers the tools to meet it. By “abstraction” I mean the isolation of something’s essential properties so that it can be generalized and reused for wider application. Many software developers will tell you that the whole history of the software industry can be described by increasing levels of abstraction.

Abstraction allows product designers to conceptualize ideas at a higher level, which enables better and more innovative designs. It’s like using building blocks, adding the custom pieces, and then rapidly deploying them. If you need a standard building block that gives you internet connectivity, a camera, and a programmable computer, you can always use an iPad or a smartphone as a starting point. The advent of the iPad raised the level of abstraction for a whole group of hardware builders who formerly buried PCs in their systems. Notice all those new point-of-sale systems, or the remote-control apps that use them? They’re based on the iPad. Cloud computing abstracted away the whole provisioning of computing services for firms like Uber and Airbnb, as well as Nest and other hardware builders.

There are important implications for companies. For corporate leaders, one of the key lessons is that higher levels of abstraction shrink the entry barriers to numerous businesses — it seems that everyone can develop a new digital product. Companies need to be constantly on the alert for the next software-based product that might pose a competitive threat.

For product designers, the first implication of the software-replaces-hardware trend is that a much higher proportion of the value of a product will be in the electronics. The Boston Consulting Group estimates that the cost of the electronic parts will rise from 20% of the value in a typical automobile in 2004 to 40% this year. That means a major shift in the supplier network, with consequences that many are not prepared for.

It also means that much more of a product’s differentiation will be expressed in software. Over-the-air updates give firms the opportunity to add features, fix mistakes, or optimize performance, after the hardware part has been shipped, as long as the hardware design is robust enough to handle more demands than initially planned. When NASA sent the Curiosity rover to Mars, it discovered a software bug after the spacecraft had been launched. “Software can be updated, but hardware is fixed,” one of the engineers explained about the ultimate over-the-air update.

Software development will be more complex. As engineers take on more-complex control regimes, real-time software development and simulation tools will play a critical role in system designs. Complex-systems designers already know how to do this, but as usage becomes more pervasive, more firms will need to learn how to manage simulation and testing tools, as well as how to manage software complexity.

Finally, connectivity will assume a bigger role in the functioning and differentiation of products. Thus designers will have to take security seriously. For some applications like automobiles, manufacturers are putting firewalls between the infotainment side and the vehicle control and powertrain side. But for many new hardware devices that “live on the net,” we are entering a brave new world where security strategy is going to have to be a core design principle.

The software revolution will be a powerful complement to the cheap-computing revolution, and the opportunities for unique and innovative products are boundless — it’s just a matter of programming.

How Pinterest’s Buy Buttons Can Change e-Commerce

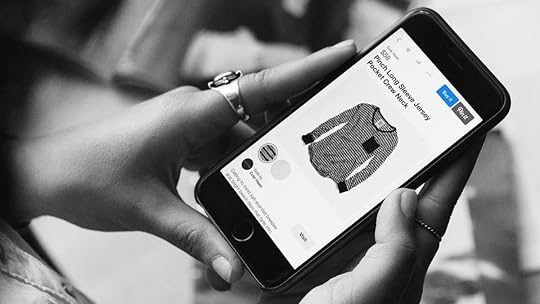

Courtesy of Pinterest

Will buyable pins turn Pinterest into the web’s new shopping mecca? That’s the question marketing and e-commerce professionals need to answer now that Pinterest has announced it will soon offer “Buy” buttons to let users buy products directly within its app. And while there are plenty of reasons to think that buyable pins could turn the platform into an e-commerce powerhouse, it stands a greater chance of succeeding if it adopts key features offered by other online retailers and search engines, such as Amazon, and adapts them to the unique habits of the Pinterest community.

My own thinking about the power of buyable pins has been shaped both by research on how social networks drive purchasing (as featured in these pages in 2012 and 2013), and by my experiences as a compulsive online shopper. As someone who regularly goes on digital shopping benders (often pinning my top finds before I commit to them) I have a personal stake in seeing buyable pins enhance the Pinterest experience — instead of detracting from it.

So what will Pinterest get out of me spending the entire weekend online (strictly hypothetically), shopping for dresses? Well, it won’t take a direct cut; for now all the revenue earned through buyable pins will go straight to retailers — though Pinterest stands to make good money by charging companies to promote their now-buyable pins. The platform stands to win big by plugging what is currently a major hole in its user experience: for all the time shoppers like me spend curating potential purchases on Pinterest, we have to go elsewhere when it comes time to take out our credit cards.

Interestingly, that “elsewhere” is as likely to be offline as online. As a 2013 Vision Critical study showed, half of Pinterest users actually buy in-store when they get around to buying something they’ve pinned. By making it easier for shoppers to buy directly from Pinterest, brands may shift some of that offline shopping back online, which would allow Pinterest to more clearly establish the ROI of promoted pins.

Moving purchasers more quickly from pin to purchase is one way buyable pins could also help brands boost sales. While half of Pinterest-driven purchases are made within one week of pinning, only 10% are made within 24 hours. Since about a third of Pinterest purchasers buy items they hadn’t previously contemplated, this suggests there is a big opportunity to increase impulse buying through the platform.

To realize these potential gains for both retailers and the platform itself, Pinterest needs to offer the features that will make it competitive with other visual shopping sites. Inspired by Pinterest’s success, a number of these sites have already introduced Pinterest-style curation, including my personal favorite, ShopStyle. Even Amazon has introduced a pinboard-like feature called Amazon Stream. To compete for shoppers, Pinterest will need to think about certain features that have helped other sites succeed. That means, for example, giving users a way to filter and sort search results by price and available size. The platform may also need a way to flag discounts for deal-hunters. The ability for users to get a notification whenever a pinned item goes on sale – and then click to buy immediately – could be a powerful purchase driver.

But buyable pins won’t take off by simply replicating what has worked well elsewhere. Pinterest needs to leverage the unique strengths of its platform. One of those is the power of curation: 43% of Pinterest purchasers said that the platform influenced their purchase by providing additional information or product reviews, usually from other users. If Pinterest can come up with a model that allows dedicated taste-makers to actually earn income by curating buyable pins, it will inspire the kind of value-added pinning that drives purchasing.

The most obvious way to do that would be through an affiliate program that allows pinners to earn some portion of the revenue of any item purchased through a buyable pin on their boards. That would not only drive focused curation, but encourage curators to prioritize buyable pins when they are creating their boards – which again, provides retailers with a reason for making their pins buyable (and paying to promote them).

While this model might seem most obvious for categories like fashion and home décor, the Vision Critical report showed that cooking and dining was actually the most-followed topic among Pinterest users (66% said they followed these pins), and 24% of Pinterest purchasers bought in this category.) However, a simple per-pin purchase model won’t always work, especially when, for example, users want to buy multiple ingredients for a single recipe. Enabling buyable pins for entire shopping lists – so that a single click adds all the ingredients to your next Amazon wish list – will also help Pinterest drive purchasing.

If all of this sounds like the beginning of a golden era in which online shoppers can easily purchase from collections curated by an army of citizen-stylists, be aware that there are potential risks here too. Part of what has made Pinterest so effective as a purchase-driver is the strong element of serendipity: you never know what interesting item you might stumble across while browsing your friends’ latest pins, or scanning for Wonder Woman-themed clothing. As we’ve seen with other social networks, the shift towards monetizing a platform with paid promotions and transaction revenue can often lead to a backlash from users who mourn the loss of a grassroots-driven experience.

As Pinterest explores ways to make the platform more valuable to corporate customers, it will need to ensure that promoted, buyable pins don’t crowd out the quirky, user-driven pinning that gives the site its character. It’s a challenge that’s hardly unique to Pinterest: Facebook, Twitter and Instagram have all created their own instant conversion or buy tools, blurring the line between social networks and e-commerce sites. What will make on-site purchasing work for all of these sites – and particularly for Pinterest – is treating instant purchase as an extra feature in the content that a user might encounter anyhow, rather than as a reason for putting it in front of their eyeballs.

The Internet already offers people plenty of ways to buy stuff; what makes social networks special is the ability to connect with our friends and peers. Well-handled, a purchase feature means that the stuff our friends, colleagues or favorite style mavens share is easier for us to buy when we want to. Handled badly, it not only fails to make the sale: it turns our social relationships into just another shopping mall.

June 8, 2015

Big Data and Big Oil: GE’s Systems and Sensors Drive Efficiencies for BP

Sponsor content – insight from GE.

With energy demands rising and reserves of oil and gas becoming more challenging to access, the productivity revolution promoted by the Industrial Internet is of vital importance to the oil and gas sector. By combining decades of manufacturing expertise with its rapidly expanding software engineering capability, GE is leading the big data revolution so that its customers can operate both more effectively and efficiently.

The Industrial Internet drives improved business outcomes for customers by harvesting the vast quantities of data produced by the GE machines they have installed, such as jet engines and MRI scanners, and feeding this into advanced analytical systems. By analyzing the data it is possible to pursue the ‘power of one percent’, a GE term which states that efficiencies of only one percent can make a dramatic impact across the $32.3 trillion of relevant sectors.

In the oil and gas sector, GE is working in partnership with BP to ensure the efficient operation of critical rotating machinery found on the energy company’s production facilities. Such equipment includes compressors, generators and critical pumps that are vital to ensure the safe extraction and transportation of oil and gas, around the globe.

By analyzing sensor data such as vibration, rotor position, temperature, pressure flow and other parameters, GE is able to identify changes in the operating condition of the machine or determine that the machine is no longer performing at its optimal capacity. Identifying the early onset of abnormal operating conditions minimizes disruption and avoids unnecessary periods of down time that often result in lost production or increased costs. For example, BP aims to extend the running period between overhauls without interruption, a substantial challenge due to the aging infrastructure associated with some parts of the industry and the highly challenging environment that it has to operate in.

BP has deployed GE’s System1TM and SmartSignalTM software across a number of its offshore production facilities located in the UK and Norwegian sectors of the North Sea, along with other key oil and gas areas such as Gulf of Mexico, Caspian Sea and Angola. Utilizing their investment in offshore network connectivity, BP is able to remotely monitor its machinery from its Advanced Collaborative Environment (ACE) center in Aberdeen and take advantage of expert support from any of GE’s dedicated remote monitoring centers around the world. Remote monitoring has a number of benefits for customers, not least because it removes the need to bring extra staff on to the rig to undertake physical monitoring in an environment which can be plagued by hostile weather conditions. It also means that experts can be consulted remotely from anywhere around the world, as required.

GE assists BP to harvest and manage large volumes of data from sensors installed on its offshore machines with the ability to vary the amount of data being captured based on operating status and when a potential problem is identified so that an accurate diagnosis can be made and preemptive interventions taken. BP’s objective is to eliminate defects in operations, and this solution ultimately allows BP to take a more proactive approach to maintenance, whilst having additional insights to manage risk.

The extraction of oil is a highly complex process and is made more difficult by the fact that the oil is often mixed with pockets of hydrocarbon gas. Moreover, with exploration targeting new frontiers in ever more demanding and challenging locations with increasing water depths, companies such as BP are looking to deploy advanced technologies to enable access to these reserves.

As Gillian Goby, Performance Enhancements Team Leader of BP notes: “The oil and gas industry is an extremely dynamic sector that places great demands on its personnel and equipment. Any solution that helps to ensure the integrity of our assets whilst minimizing production disruptions, offers significant benefits for our operations. BP highly values condition monitoring because it helps us manage our machines more effectively by allowing us to identify developing abnormal conditions and plan our maintenance activities.”

The synthesis of big data and engineering excellence forms the backbone of GE’s offering in the oil and gas sector. As customers like BP understand, the sector presents many challenges, but with the advent of big data and the Industrial Internet there is much scope to eliminate variability of performance and increase up-time in oil and gas exploration and extraction. The harnessing of oil helped drive the Industrial Revolution, and now such transformative power is being driven by the next technological revolution, the Industrial Internet.

See how GE can give you the edge: invent.ge/oil-and-gas

Corporate Alliances Matter Less Thanks to APIs

Eighteen years ago, five airline companies—Lufthansa, Air Canada, United Airlines, Thai Airways and Scandinavian Airlines—formed an alliance with a vision to offer better services to their customers. Under the banner of Star Alliance, these companies started sharing resources such as sales offices, maintenance facilities, operational staff, and seating capacity. As a consequence they could offer customers a broader set of destinations, options for collecting and using mileage points across partner airlines, and lower prices because of cost consolidation. Customers saw immediate value in this seamless enhancement in the scope of services. Even when dealing with any one airline, they could enjoy access to the resources of several airlines. Hailed as one of the most successful alliances in business history, Star Alliance, whose number of partners ultimately grew to 27, soon inspired the formation of rival airline alliances such as One World and Sky Team.

The onset of digitization, however, has exponentially amplified the potential of this success story. In the digital world, customers may still deal with any one airline, but their access now expands to the resources of much more than just a handful of allies. Indeed, through any one airline, customers can have access to thousands of organizations across a spectrum of businesses such as hotels, rental cars, vacation resorts, cruises, and restaurants. In addition, they can use and share mileage points across these numerous organizations. The invisible force behind this transformation is the application program interface (API), a technology that allows firms to interact and share informational assets with other firms. As digitization opens new opportunities for firms to leverage informational, rather than physical, assets, APIs are poised to replace alliances as the most common means for inter-firm partnerships.

How are APIs different from alliances? We see three important dimensions.

Scalability of operations. Limiting the size of alliances is understandable. They entail negotiating complex terms of engagement along with how revenues, physical assets, and data will be shared. The management of shared assets and activities (mostly through human interactions) can be complex. And the sharing of physical assets sharing and integration of data usually demand substantial investments that are typically specific to each relationship. Not surprisingly, as the number of alliance partners increases, the cost and complexity of data integration escalates non-linearly.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

With APIs, however, the terms of engagement and revenue sharing can be highly automated. Also, informational assets replace physical assets as the key resources shared. As a consequence, data-integration investments need not be relationship specific. For example, Expedia’s publicly described APIs (Expedia Affiliate Network) make it possible to integrate data across numerous partners, which include almost all competing airline companies and thousands of hotels, resorts, rental car companies, and payment-service providers. There need not be any limit on the number of partners signing up. In fact, the more partners that sign up, the more Expedia benefits, with marginal, if any, increase in costs and complexity.

Flexibility in acquiring partners. Companies frequently forge alliances to share risks in new ventures or to leverage complementary resources. General Mills, for example, formed an alliance with Nestlé (Cereal Partners Worldwide) to enter Europe with breakfast foods not only to mitigate the risks of entering a market dominated by Kellogg but also to utilize Nestlé’s distribution network in that part of the world. Implementation costs associated with such objectives and the fact that not all companies are suited to share risks or offer complementary resources restrict firms to working with a narrow set of partners.

APIs, on the other hand, turn the burden of finding partners willing to share risks and offer complementary resources on its head. With APIs, companies pivot from finding partners to letting partners find them. Known as the URL strategy, Eric Schmidt of Google called it “ubiquity first, revenue later.” Kraft Foods and Nestlé, for example, opened API platforms that can attract a variety of potential partners, ranging from those who suggest recipes and cuisine preferences to advocates of health consciousness who may highlight food allergies or calorie counts. Not all these partnerships may bear fruit, but a few may become blockbusters. The idea is to attract all kinds of partners first and worry about the risks of revenue generation or the usefulness of their synergies later. This API-based approach thus allows companies to be substantially more flexible in finding effective business partners.

Fluidity in business goals. Companies usually have specific aims and finite objectives when they venture into an alliance. The costs associated with alliances and the risks of failures do not allow for any ambiguity in the goals. When Starbucks formed an alliance in 1993 with Barnes & Noble, for example, it was with an express goal of creating in-house coffee shops within the stores of the book-retailing giant. And indeed such unequivocal clarity in purpose was likely necessary for this alliance to succeed.

API-based partnerships, however, allow firms greater fluidity in business goals and substantially more experimentation in realizing them. Take the case of Twilio, a company that provides text-, voice-, and picture-messaging capability that can be embedded into any application. This service could potentially be used in many industries. Instead of forming alliances with companies and launching into any particular industry, Twilio opened its APIs and allowed third-party developers to use them. It is now used as the communication engine for Uber, Airbnb, Home Depot, Walmart, and others. Instead of investing heavily in any particular partner specific resources, Twilio focuses on the communities that drive adoption of its APIs.

These dimensions of APIs take business partnerships to an entirely new level. Indeed, just as Big Data transformed business analytics through volume, variety, and velocity, APIs are revolutionizing traditional business alliances and partnerships through scalability, flexibility, and fluidity. APIs may well be heralding the Age of Big Alliances.

How Merck Is Trying to Keep Disrupters at Bay

Pharmaceutical companies, buffeted by regulatory changes, new drug technologies that alter entry barriers and competition, price pressures, and an estimated 300,000 job cuts since 2000, seem to fit the popular narrative of large organizations unable to deal with disruptive forces. In the 1990s, for example, pharma firms were regulars on “Most Admired Company” lists. Merck and Co. (Kenilworth, NJ, USA) topped Fortune’s list for seven consecutive years. Not now.

But “reports of my death are greatly exaggerated,” as Mark Twain said.

Change and innovation are choices, not givens, in any organization, and there are managerial levers for making these selections wisely. With its Emerging Businesses (EB) group (where one of us serves as President), Merck started a journey about three years ago with a core investment thesis: there are areas of growing unmet need in health care that intersect with its established competencies. Within EB, Merck first created a Global Health Innovation Fund and then a Healthcare Services and Solution unit to identify, develop, and operate nascent opportunities that fit that thesis.

Here are the philosophies and strategies that Merck’s EB group has used successfully, and each has implications for companies seeking new routes for profitable growth. They also debunk the common notion about disruption that big companies must willfully forget what they learned from prior periods of growth and success.

Integration is key. Contrary to current conventional wisdom, evangelists of new ideas must engage in a purposeful way that fosters collaboration with wider organizational networks, not ignore or pretend to forget them, for a couple of reasons. For ideas to become reality, a company needs repeatable processes, not only out-of-the-box insights. Also, most billion-dollar ideas don’t start that way; they can benefit from the established operations, go-to-market or service capabilities, and other corporate assets that help to scale rapidly.

To do that, Merck formed a Strategy & Innovation Council with people from across the company. But the Council was not the typical think tank for brainstorming ideas. Rather, members were explicitly chartered to network with the leaders of new business initiatives and existing business units within the broader organization relevant to scaling a new initiative. It’s a two-way flow of information from ideation to execution, and transparent: meetings, successes, and decisions are posted on an inter-company wiki.

One result is Ilum Health Solutions, a new business that provides hospitals with high-precision clinical decision support at the point of care for infectious diseases and associated conditions including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and sepsis. For perspective on the market opportunity, consider: sepsis, an inflammatory response to infection, is by itself estimated to consume more than $20 billion in health-care costs annually, or more than 5% of total hospital costs and about 7% of all Medicare costs.

EB operates Ilum as a separate business, while still drawing on Merck’s established corporate resources in IT, finance, privacy, compliance, and legal. This combination provides scale, scope, and cost economies, which allow Ilum to tailor its offering for each individual hospital.

It’s not just products. From Edison to Jobs, we’ve tended to associate innovation with products, and nowhere is that more true than in pharma, where new products are key to success. But innovation in solutions and business models is equally important because new health-care tools and technologies create beyond-the-pill opportunities.

In 2014, the Global Health Innovation Fund combined Preventice, developer of the PatientCare Platform and the BodyGuardian Remote Monitoring Sensor, with eCardio Diagnostics, a provider of remote cardiac monitoring products and services. The combination has created the industry’s first wireless, discrete, and switchable remote system, and has provided physicians and patients with real-time monitoring and predictive analytics that have been shown to reduce readmission rates for cardiovascular patients.

With the right interactions, large companies can add customer value and augment products with recurring revenue businesses. Established firms often have the access and credibility required to get customers to try a new service. And trial is important, because services generally provide experiential value that is only visible after usage, not ex-ante.

Most importantly, for many companies like pharma firms that have focused exclusively on products, services spur other ideas about relevant customer solutions.

Experimentation is vital. The lean-startup software ethic of launching minimal viable products in order to fail fast and learn is a challenge in many businesses and especially in healthcare where no one wants a minimum viable pacemaker or “lightly tested” drug. But translating an experimentation mindset to the relevant industry conditions is key for innovation in a large corporation.

The translation involves people and processes. EB has people with both Fortune-500 and private equity backgrounds. The latter helped to establish staged funding, adaptive planning, tranching, and other private equity processes for collaborations with the core enterprise. These processes create a discipline often missing from standard capital budgeting procedures in large corporations where “strategies” tend to be the compilation of business-unit plans that, in turn, are a compilation (not integration) of ongoing functional initiatives.

It has also abandoned other initiatives, and that’s equally important in managing innovation in a corporate context. Some great business ideas don’t belong in your company, and free-range innovation often drives value-destroying diversification in corporations.

EB plays the role of a venture capitalist or private-equity board with responsibility to sell, spin-out, or wind-down initiatives that, in practice, are found to be a poor strategic fit. Examples include Prophecy, a crowd-sourcing analytics business, and Koneksa, a consumer sensor initiative. Both have real market opportunities and strong value propositions, but they don’t provide the strategic fit that would justify allocating the assets needed to scale and generate good returns.

At the same time, the highly regulated nature of the healthcare industry — from drug products to health IT and marketing and promotions — requires that this translation also include the discipline of developing and validating fully-compliant infrastructure components, a requirement often at odds with nimble experimentation. But, because of EB’s diverse set of employees, it’s able to stimulate ideas from other industries and counter “paradigm bigots.”

Usually, companies often want to utilize “core competencies” in order to expand into “adjacencies.” But it is naïve to expect busy line-of-business or R&D heads to do that kind of ideation, experimentation and business-model assembly. It would also be surprising — or simply hit-or-miss — if a separate group of bright people from outside found traction for their ideas in a large organization wrestling with changes and quarterly earnings goals.

As Louis Gerstner, reflecting on his experience at IBM, put it, “Who says elephants can’t dance?” But to do that, managers must view innovation as involving more than inspiration, perspiration, a determination not to be “disrupted,” and a willingness to let a hundred flowers bloom. It also means processes for linking capabilities across the organization so that new and established units are capable of more in the aggregate than they are on their own. As a great organizational scholar, James March, once noted, “Leadership involves plumbing as well as poetry.”

What Makes an Organization “Networked”?

In 1904, the great sociologist Max Weber visited the United States. As Moises Naim describes in The End of Power, travelling around the vast country for three months, he believed that it represented “the last time in the long-lasting history of mankind that so favourable conditions for a free and grand development will exist.”

Yet while Weber saw vast potential and boundless opportunities, he also noticed problems. The massive productive capacity that the industrial revolution had brought about was spinning out of control. Weber saw that traditional and charismatic leadership would have to give way to a more bureaucratic and rational model.

Most of today’s organizations were built on Weber’s principles. So much so that we see them as “the way things work” and forget that bureaucracies were once innovations too. Today, we live in a time of transformation every bit as colossal as what Weber saw a century ago: a shift from hierarchical to networked organizations. Here’s what you need to know.

1. If it can fit on an org chart, it’s not a network.

Before Weber’s bureaucracies became predominant, most enterprises were fairly organic. People shared the work, helped out where they could and all pitched in to get the job done. At the end of the day, they went home and then came back the next morning, ready to tackle a new job, which was often different than the day before.

Yet the increase in scale that the industrial revolution brought about resulted in a difference in the kind of work that was to done. Jobs would be broken down into small, specific tasks and be governed by a system of hierarchy, authority and responsibility. This required a more formal form of organization in which roles and responsibilities were clearly defined.

As business became more complex, these rigid structures grew increasingly untenable and so management theorists began to look for another way—matrixed organizations. In addition to the hard lines of responsibility and authority, dotted lines were used to denote cross-functional authorities and responsibilities.

Yet before long, it became clear that matrixed organizations also had problems. Despite the often mind-numbing complexity of matrixed organization charts, they still could not match the complexity of the marketplace. So matrices, in a sense, led to the worst of both worlds, a cumbersome organizational structure and the inability to adapt to fast changing contexts.

The truth is that networks are informal structures. If it can fit on a traditional org chart, it’s not a network.

2. Silos themselves aren’t the issue.

The term “network” is often misconstrued. In management circles, it is often used to mean an organic, unfathomable, amorphous structure, but really a network is just any system of nodes connected by links. So, in that sense, any organizational structure is a network, even a formal org chart.

For functional purposes, networks have two salient characteristics: clustering and path length. Clustering refers to the degree to which a network is made up of tightly knit groups while path lengths is a measure of distance—the average number of links separating any two nodes in the network.

We often hear about the need to “break down silos” to create a networked organization, but this too is a misnomer. Silos are functional groups and they need a high degree of clustering to work effectively and efficiently. The real problem in most organizations is that path lengths are too great and information travels too slowly, resulting in a failure to adapt.

The most efficient networks are small-world networks, which have the almost magical combination of high clustering and short path lengths. So silos aren’t the issue—high clustering promotes effective collaboration—the trick is to connect the silos together effectively.

3. Small-world networks form naturally, if they’re allowed to.

The idea that clusters of close-knit teams can somehow increase the flow of information on their own, simply through shorter social distances, seems unlikely. Yet actually, small-world networks often form naturally, without design or complex organizational engineering.

In fact, in their initial paper describing the phenomenon, Duncan Watts and Steven Strogatz found the neural network of a roundworm, the power grid of the western United States, and the working relationships of film actors all followed the small-world network pattern. It takes effort to design a traditional organization, but small-world networks form naturally.

The reason why these types of networks are so pervasive in nature is that it takes a relatively small number of random connections to drastically bring down social distance. Over time, most systems will tend to become small worlds if they are left uninhibited. So why do truly networked organizations seem so hard to create?

The unfortunate, but obvious answer is that traditional organizations actively discourage connectivity. They favor strict operational alignment within specific functional areas while doing little to foster links between them.

4. Networked doesn’t mean flat.

The latest management craze is flat, leaderless organizations. Much has been made about Zappos’ recent efforts with holacracy, but as Tim Kastelle recently explained, the jury is still out whether the effort—and those like it—will be ultimately successful. My own feeling is that flat structures will work for some cultures, but not others.

The important thing is that an organization does not have to be flat to be networked. In his new book, Team of Teams, General Stanley McChrystal explains how he drastically reinvented how his forces operated, but didn’t changed the formal structure. The changes mainly had to do with informal structure, communication and forging a shared purpose.

General McChrystal’s Special Forces command was still hierarchical and clustered into small operating groups. What changed is how they were interconnected. Rather than a collection of units, they became a synchronized organization that acted as one.

So what really needs to change is not how we describe our organizations, but the role of leaders within them. Whereas before, it was the role of managers to direct work, in a connected age we need to instil passion and purpose around a shared mission. The networking, if encouraged and not inhibited, will take care of itself.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers