Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1283

June 17, 2015

Solving Complex Social Problems Through Collaboration

Geneva Global, a tiny but mighty philanthropic consulting firm that specializes in international development, is helping to change the world from its small suburban corner of Wayne, Pa. With a team of just 52 staff members, they are quietly igniting social good on a global scale through the repetitive flexing of an approach called dumbbell collaboration.

“On one side of the dumbbell are donors, either private philanthropists or foundations, and on the other are nonprofits,” explains Ava Lala, a director at Geneva Global. “Both want to solve complex social problems, such as modern-day slavery, but the ambition of the donors often outweighs their resources, and the nonprofits often spend precious time trying to connect with donors. The solution, as we see it, is to group each of these ends together, to be the handle in the middle that connects the two.”

And it’s here why the dumbbell serves as the perfect metaphor. Geneva Global sees philanthropic consulting — its role as the humble handle connecting two larger sides — as both the immediate project in front of it and as a strength training session to prepare for future projects. It takes seriously this belief that the more it exercises building collaborative relationships the stronger it and its clients will become in battling some of the world’s most pressing issues. It’s an approach to collaboration that has proved successful in some of the most challenging circumstances imaginable.

When creating philanthropic initiatives for its clients, Geneva Global first gathers insights about the client’s interests. For example, does the client want to address a pressing global health issue like Ebola or tackle an educational problem like out-of-school children? Geneva then typically seeks out indigenous, grassroots, and innovative nonprofits in developing countries who have a strong track record of success and who are willing to work together to build a program. The benefit of finding such partners is that the program can be tailored to the local context, encouraging buy-in from the community and local stakeholders and ultimately reaching more people. The challenge, however, is that these community-based organizations tend to be smaller nonprofits that lack sophisticated processes and often struggle to absorb a lot of funding.

In order to maximize the efficiency and sustainability of their client’s money, Geneva Global groups these nonprofits into a “community of practice.” In doing so, it has found that these smaller organizations make substantial improvements based on what they share with and learn from each other.

The results are undeniable. In one example, when Geneva Global was managing an anti-slavery program for a client, they recognized that people were being trafficking between India and Nepal, but that the relevant nonprofits working in these regions often were unaware of each other. So Geneva identified the most promising organizations, put them through an exhaustive due diligence process, and ultimately selected 28 of them to work together in what they called a Strategic Initiative. Some NGOs focused on community education to prevent slavery, others focused on rehabilitation to protect victims, and others focused on legislation to prosecute slave traders. By learning from peers, each nonprofit strengthened its capacity to do more effective work, which is ultimately what donors want to achieve. The results touched over 600,000 lives through slaves being rescued, villages forming vigilance communities, and people receiving sustainable education, psychosocial therapy, and other services.

When appropriate, Geneva uses a similar strategy to encourage donors to come together, but in this model the end result is to create pooled philanthropic funds. “Borrowing from the financial world, this model of pooling philanthropic funds allows private donors to leverage their funds for greater scale, diversify their risk, and retain some level of control,” says Doug Balfour, Geneva Global’s CEO.

Egos, the fear of competition, and sheer coordination can be challenging to navigate when trying to get donors to collaborate. In the case of pooled philanthropic funds, Geneva Global has found that having large donors gain board seats in accordance with their level of funding is one way donors can retain influence. Creating an independent brand and having a third party to manage the coordination of the pooled donor fund has also worked to ensure timely and successful launches.

For example, in 2011, Geneva partnered with the Legatum Foundation to create the END Fund, which brought together a collaborative donor set that has since raised more than $50 million. The money has been used to support neglected tropical disease control initiatives run by various nonprofits and government ministries of health in over 15 countries. “Over 75 million people have been reached through mass drug administrations. That kind of impact and scale can only be achieved when donors are willing to collaborate, learn from one other, and use their collective voice to spark change,” says Balfour, who sits on the END Fund board.

Collaboration is often talked about, but much less often done, and far less often done well. The concept of dumbbell collaboration has allowed Geneva Global to see each opportunity as a chance to flex and maintain its existing strengths while building new ones. The end result is that the metaphor has allowed it to envision and then execute a style of collaboration that, especially when applied to the social sector, can bring about sustainable social change and increase the bang it gets from its philanthropic bucks.

Americans Are Willing to Pay More for the Digital Grid

Sponsor Content Insight from GE.

As power outages go, the iguana affair was a mundane one. On July 27, a hapless lizard shorted a piece of electrical equipment in the middle of the Florida Keys and knocked out power for 11,000 local residents. It was an act of nature no outage prevention system would have been able to predict. But since the lizard climbed inside a substation, repair crews were able to locate the short and restore power in 10 minutes. “Spotting problems within the limited space of a substation is relatively easy,” says Chris Prince, application engineer at GE Digital Energy. “It’s a high-density nerve center for distributing power. But good luck finding and fixing a problem that fast when it happens along the miles of overhead and underground lines connecting the substation to the consumers.”

In an era when a smartphone can quickly pinpoint its location on a map, few power providers know that customers lost electricity before somebody calls them. Fewer still can see whether the outage was caused by a fallen tree branch, a lightning or faulty equipment.

Americans are taking notice. A new survey measuring public perception of grid resiliency found that many respondents were willing to pay $10 per month on top of their electricity bill to make sure that the grid becomes more reliable (see the results here).

The survey, which was commissioned by GE’s Digital Energy business, also found that a majority wanted utilities to start using digital communications and social media tools to keep them informed in real time during a power outage. “Consumers want to see investment in technology that prevents power outages and reduces the time it takes to turn power back on,” says John McDonald, director of technical strategy and policy development at GE Digital Energy.

Utilities are getting the message. As wireless networks became more ubiquitous, power companies started placing digital sensors along its lines and inside switches, breakers, smart meters and other devices. The sensors feed grid data to data collection centers where algorithms process it to create a virtual map of the distribution network.

Prince says that the network map resembles a tree where the transmission lines that come from the power generation plants are the roots and the substation is the trunk. “The feeder circuits that reach out through neighborhoods to residential customers are the branches where we’ve traditionally had the least visibility,” he says.

Prince says that an outage event could be due to a single cause or multiple causes nested together. This makes the prime cause harder to find. But digital systems that connect the grid to the Industrial Internet and string together smart sensors, controls, and software can quickly detect and locate trouble, and then isolate a likely problem area along the right branch. “Instead of telling the crew to patrol miles of a line, I can narrow the location to a block or two,” he says. “At the same time, the control system will quickly restore power to the other lines leading from the trunk that did not suffer any damage, and bring power back to those customers sooner.”

McDonald says that a number of utilities have already started implementing automation on the feeder lines where they see the most value. NSTAR, for example, brings electricity to 1.1 million customers living in central and eastern Massachusetts. Starting in 2009, the company reached out to GE and started building a “self-healing” grid. Today the system consists of 2,000 smart switches and 5,000 voltage and current sensors. The system was already tested by Hurricane Irene in 2011 and Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

During Irene, 500,000 customers lost power but the system was able to reroute it and turn the lights back on for close to half of them within an hour. NSTAR calculates that the new grid visibility has allowed it avoid 600,000 customer outages so far. “The concept of grid monitoring has been around for decades,” McDonald says. “But the advances in big data, software, fiber optics and digital wireless communications now really bring it alive.”

Not even lizards can stop it.

See how GE can give you the edge: gesoftware.com/solutions/intelligent-environments

The Perils of Algorithm-Based Marketing

If I told you this article was written by an algorithm (and you believed me), chances are you’d be creeped-out, suspicious of the content, and unable to muster much if any emotional response to it.

That’s a natural response. Yet companies don’t seem to be able to see algorithms from the consumer’s point of view. They think nothing of deploying algorithms as marketing tools. Instead, they should be looking for ways to inject humanity — and, yes, actual humans — into their efforts to reach out to customers.

I’ll explain why.

Originating in computer science, algorithms are simply sets of “if–then” rules. But a number of factors — easy-to-use predictive analytics and data-visualization tools, the proliferation of mobile devices, and companies’ ability to track and measure customer behaviors — have helped companies find an astonishing variety of ways to use algorithms, particularly in marketing.

Algorithms help marketers utilize customer-specific knowledge — demographics, previous behavior, fellow customers’ choices — to craft customized offers and deliver them, often in real time. They help companies track customers, cross-sell to them, and promote products. Banks use algorithms to suggest new products to customers, online retailers deploy them to set and change prices, and media companies rely on them to recommend and deliver streaming content and ads.

But despite the broad adoption and growth of algorithm marketing, companies should be cautious about it, for four reasons.

Algorithms aren’t sensitive enough to context. Effective marketing relies on messages that are attuned to the customer. Customer response, even for the most mundane of products, is sensitive to a host of ever-changing factors. On any given occasion, everything from personal factors such as how well a person has slept the night before, current mood, hunger, and previous choices, to environmental variables such as the weather, the presence of other people, background music, and even ceiling height can influence how a customer responds. Algorithms can use only a handful of variables, which means a lot of weight is inevitably placed on those variables, and often the contextual information that really matters, such as the person’s current physical and emotional condition or the physical environment in which the individual is tweeting, Facebooking, or buying online, isn’t considered.

They arouse suspicion and can easily backfire. In a climate where privacy concerns are perennially at the forefront of customers’ minds and trust is at a premium, customized marketing of any sort is risky. If customers feel the marketer knows too much about them, algorithm-based personalization can seem creepy or backfire badly. Something as innocuous as a customized Facebook feed highlighting the past year can generate tremendous grief for users in certain circumstances.

They encourage complacency. Having tools that capture exhaustive data about customers, quantify minute aspects of their behavior, and measure their responses can create a false sense that one knows customers really well and understands their motivations and triggers. At best, such complacency may limit marketing activities to those that can be measured easily and have worked in the past. At worst, it can lead to a completely inaccurate customer portrayal, ill-conceived marketing overtures, uninterested customers, and wasted resources.

They stifle customers’ emotional responses to marketing offers. By their nature, “if–then” rules imply a decision calculus (“If you are 35–45 and just paid 20% down with a mortgage, then you should purchase a home equity line of credit”). Marketing algorithms encourage analytical consumer decision making. Yet many customers make choices impulsively, are motivated by fun or a need for variety, and respond with spontaneous, emotional reactions. It is in these unscripted and impromptu interactions that the customer forges the strongest and most meaningful connections with brands. By shifting the customer into a more calculated and methodical mind-set, algorithm-based marketing minimizes opportunities for forming emotional bonds and limits the range of customer actions — to the marketer’s detriment.

How should marketers solve these problems? By injecting a strong dose of human into their customer interactions.

Marketers can “inject the human” into their offers and activities in many ways. Some approaches involve bringing in an actual human to interact with customers; others require making the algorithms work in more human-like ways.

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

First, understand the context and make it part of the tailored offer. Effective marketing is a never-ending quest to understand the contextual drivers of customer response. Constantly testing the impact of different contextual factors through field experimentation and observational research is part of the solution. Translating this understanding to marketing programs may mean creating more-sophisticated algorithms having more rules and greater flexibility to apply those rules; in another important sense, however, it involves the creation of processes and activities where the marketer can react to a customer without the use of algorithms. Waitstaff empowered to offer a complimentary cocktail to a distraught customer, or trainers who can take the time and trouble to educate a new software buyer after understanding exactly how she will use it, produce value for customers that algorithms simply cannot. Fondue restaurant chain The Melting Pot takes just such an approach, empowering servers and managers to offer complimentary food and cocktails and do other things to deliver a superior customer experience.

Second, introduce unpredictability into marketing. Algorithms favor patterned marketing activities, such as coupons or catalogs that are sent every quarter, emails sent each week, or twice-a-day tweets. Such marketing loses its impact partly because it is so firmly structured that customers become habituated to these overtures and tune them out. Introducing randomness and surprise into marketing activity breaks the shackles of algorithms and goes a long way toward counteracting customer ennui. An unexpected call or a surprise new product announcement, or even a sale that fails to materialize when it should have, make the brand more authentic, human, and exciting. Unpredictability allows customers to seek variety and respond emotionally to the brand. TD Bank, a Canadian bank, turned its ATMs into “Automated Thinking Machines” last year, surprising thousands of customers with $20 bills, flowers, and merchandise, earning accolades and garnering significant attention on social media.

Third, encourage interaction with humans at key customer decision and experience points. To date, adequate technological substitutes for empathetic, competent, and empowered humans have not been discovered, which is why luxury brands, whether they are fashion labels, hotels, or automobiles, overwhelmingly favor human sales and service staff over technological methods. Within constraints of affordability, every marketer should thoughtfully consider where and how to incorporate human interactions into the customer experience. Hybrid approaches utilizing a combination of humans supported by expert algorithms for services such as financial planning, product recommendations, and building security are an effective way to “inject the human” into algorithm-based marketing activities.

June 16, 2015

4 Ways to Build a Productive Sales Culture

All businesses face opportunity costs. In the case of a sales organization, money, time, and effort allocated to accounts A and B are resources not available for accounts C, D, and so on. That reality drives the distinction between effectiveness (optimization by doing the right things) and efficiency (doing things right) that Peter Drucker and others made years ago.

A confusion between efficiency and optimization plagues many sales efforts. If we use an automobile analogy, sales efficiency (SE) initiatives — like CRM, training, and KPI dashboards — improve the engine’s horsepower. Sales optimization (SO) decisions — like aligning sales tasks with business strategy, customer selection, and sales force deployment across opportunities — set the direction in which the car will travel. As the saying goes, “If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there.” But if a car is going in the wrong direction, getting there faster is not the solution.

Companies will spend about $30 billion on CRM alone by the end of 2015, according to Gartner. But consider the work of the Boston Consulting Group, which indicates that SO practices, such as targeting high-value customers and deploying sales resources with strategically-appropriate criteria, have more than three times the impact on revenue growth than SE initiatives.

The lesson is clear: How and where you allocate available sales resources is where the leverage resides for more profitable growth.

Once you appreciate the importance of sales optimization, you need to focus on four capabilities, which will help you form a foundation on which to build a productive sales culture.

Strategy and planning process. According to surveys, about two-thirds of companies treat strategic planning as an annual precursor to the capital budgeting process. Companies tend to do plans by business unit, regardless of the firm’s go-to-market approach (which often spans business units). Further, this process now takes, on average, four to five months. While this is going on, the market is doing what the market will do. No wonder only 11% of executives say that strategic planning is worth the effort, and why in a survey of 1,800 executives more than half (53%) of the respondents said their employees don’t understand their company’s strategy.

Keep in mind: Customers’ buying processes have no interest in accommodating your planning process, so sales must respond account by account. Hence, even if the output of planning is a great strategy (a big if), the process itself often makes it irrelevant to those on the front lines who must make important decisions throughout the year in accord with external buying rhythms and selling cycles.

Cost-to-serve and customer selection. All customers are not equal, and prioritizing customers is how firms make real the crucial “scope” component of a coherent strategy — i.e., decisions about where to play in a market. Profit is the difference between the price a customer pays the seller and the seller’s total cost-to-serve a customer, which can vary dramatically. Some customers require more sales calls, or geography makes them more or less expensive to serve; some buy in large, production-efficient order volumes, while others buy with many just-in-time or custom orders that affect setup time, delivery logistics, and other elements of cost to serve.

These differences are important, if you, or your investors, take seriously the notion of return on capital, because many capital costs are embedded in cost-to-serve differences, which are typically ignored in SE metrics. If you can’t measure your cost-to-serve, then your salespeople will be driven by competing price proposals. And when you chase price and volume — as most sales compensation plans provide an incentive for salespeople to do — you can wind up damaging profits and your business model. You won’t allocate sales resources optimally.

Finally, you are ultimately at the mercy of competitors who can measure their true costs and do these things more effectively.

Sales capacity and allocation of effort. Sales productivity is largely determined by how much the sales force can do in terms of call capacity and its capability to reach target customers. Allocating that capacity is a crucial SO lever, but many leaders lump SE and SO together and the result is a strategically inappropriate allocation of resources. The issue is not lack of data. It’s knowing what data and how to use it.

A common metric used by the C-Suite for evaluating sales is the expense-to-revenue ratio. This SE measure can shed light on the relative cost efficiency of selling activities, but not (by itself) on their cost effectiveness, which is a more complex relationship between selling costs, revenues, profit margins, and customers acquired through one or another means of organizing sales resources.

Big data analytics make these relationships accessible. But the average U.S. firm with more than 1,000 employees already has more data in its CRM system than in the entire Library of Congress. To make sense of this tsunami of factoids, never forget that data and analysis are not ends in themselves. To have value, your analysis must result in better resource allocation decisions.

Good leaders know that data are not just numbers; they are also a way of viewing reality by the people who should use that data. And sales people will ignore analytics that they can’t apply to where they live: in daily encounters with customers.

Performance reviews. The most under-utilized lever for improving sales is the performance review. Busy sales managers tend to treat reviews as cursory, drive-by conversations that are mainly about compensation, not evaluation and development.

Yet, core SO issues are often only apparent at the account level and via conversations with those account managers. Reviews are where strategic direction (versus a random-walk allocation of effort) is revealed, where call patterns and customer selection are supported or changed, and where data are applied to customer interactions. Effective reviews can look at options ranging from changing prices to reflect cost to serve, reducing technical support for certain customer segments, changing the locus of relevant support, determining different ordering or delivery options, and perhaps instituting a channel strategy that offloads some cost-to-serve to resellers whose economies of scope allow them to perform these tasks more efficiently.

Aligning strategy and sales also means sometimes “firing” customers that, despite all attempts, remain unprofitable accounts. It would be naïve to expect salespeople, especially those bonused on volume, to do that on their own. Managers must manage this decision.

It’s not our intention to discourage efficiency improvements. But ultimately there is no such thing as effective selling, no matter how efficient versus a benchmark, if it is not linked to your strategic goals. SO decisions are the prerequisite for any SE improvements. Among other things, a focus on SO allows sales leaders to grow the top line using the resources they already have by deliberately focusing selling efforts on what will really make a difference.

The Best Digital Strategists Don’t Think in Terms of Either/Or

It has become an axiom that “strategy is about making hard choices,” as we have been advised for over 20 years by leading thinkers including Michael Porter and Roger Martin. But our work with a community of senior executives in the Bay Area suggests that today’s market leaders are following the advice of Yogi Berra: “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.” Faced with hard choices, innovators find ways to transcend the tradeoffs. While their competitors make the hard choice between one or the other path, these businesses reap the benefit of both.

Transactions and relationships. When it comes to digital engagement, many companies feel they have to choose either transactions or relationships. Social media evangelists tell CEOs they need to stop focusing so much on driving sales and “connect instead of promote.” A focus on the transaction, they say, jeopardizes the relationship. Meanwhile, sales strategists suggest that social media is often more “hype” than “reality.” Focus on the relationship and forget the transaction, and you waste the company’s resources. The hard choice, it would seem, is between transactions or relationships.

Sephora has become a leader in the cosmetics market by transcending this tradeoff, finding ways to achieve transactions and relationships. It has a vibrant e-commerce business and a highly engaged customer community. What is particularly impressive is how Sephora is bringing transactions and relationships together in the same experience. On the Sephora Beauty Board, community members can upload photos of their favorite “looks” with the makeup products that made it possible. Click on a photo and you can see someone’s profile or posts. Click on a product and you can make a purchase.

High-tech and high-touch. There is concern these days about how technology is replacing our jobs and estranging our connections. As our communications become more digital, our customer relationships become less personal. The only hope seems to be make our technology appear more human.

In the apparel industry, companies choose one path or the other between high-tech and high touch. Shopping services like StyleSeek take the road marked “algorithm,” while Nordstrom’s Trunk Club takes the road marked “personal service.” Approaching the same fork in the road, Stitch Fix chose to go in both directions. New customers fill out a survey about their style and lifestyle. Ever-evolving algorithms then generate recommendations for Stitch Fix stylists, who select the final assortment for their customers based on personal knowledge and relationships. It’s no coincidence that the Chief Algorithms Officer at Stitch Fix was formerly head of data science for Netflix, and its Chief Operating Officer, Julie Bornstein, was formerly CMO at Sephora. Together, they are transcending the tradeoff between high-tech and high-touch.

Size and speed. There is an African proverb, “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” Most large companies excel at going far and going together. But these days every company has to go fast. Is it possible to be both bigger and faster? The recent experience of Visa provides some lessons in how to transcend the tradeoff between size and speed.

The market for cardless payments is growing rapidly, posing a threat to Visa’s core business. Four years ago, Visa launched V.me, but failed to gain ground against its nimble new entrants. For the recent launch of Visa Checkout, Visa took a different approach. One option was to focus purely on speed, and either acquire a smaller company or create a separate skunkworks. But this would have lost the advantage of size.

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

The solution was to go for size and speed. Lara Balazs, SVP of North America Marketing, leveraged Visa’s brand and market position to recruit a team of top talent, forge strategic alliances with market leaders, and create widespread awareness in the market. Although size was an advantage externally, it was a disadvantage internally. To leapfrog the competition, she had to move fast, but she also needed the involvement of twelve different departments. She had to go fast and go together. Her solution was to rip up the org chart, creating a “team of teams” with a new kind of culture for Visa that emphasized agility and experimentation over consistency and compliance.

Profit and purpose. Purpose has become popular for many reasons. It helps to re-energize leaders, engage millennials, invigorate brands, and demonstrate corporate social responsibility. But purpose still seems like a “nice to have” or something done on the side. Corporate boards still focus on quarterly earnings.

Faced with the choice between profit and purpose, some executives are making the move to social enterprises where profit and purpose are more intertwined. However, the evidence indicates that for-profit companies with a strong sense of purpose have better financial performance. So how can companies in traditional industries achieve both?

For most financial institutions, profit is the purpose. But Wells Fargo has a purpose behind profits. According to CMO Jamie Moldafsky, “every employee at Wells Fargo is focused on helping our customers succeed financially.” This approach is reflected in initiatives such as “Untold Stories” which fulfill this purpose in local communities. Echoing their logo, Wells Fargo promises to “never put the stagecoach ahead of the horses.” Proving that they have successfully transcended the tradeoff, Wells Fargo consistently outperforms it’s less purposeful peers.

Toymaker Goldieblox shows that purpose can fuel market disruption. Their mission to increase the number of women engineers led to an entirely new kind of product that combines storytelling and building. According to Lindsey Shepard, VP of Sales and Marketing, GoldieBlox is about encouraging girls to “think about themselves as innovators that can build their own future.” The result is a disruption in the proverbial “pink aisle.”

Airbnb is also fusing profit and purpose, disrupting (at least initially) the hospitality industry. Just a couple of years ago, people considered it strange to stay in a stranger’s home instead of a hotel. But according to their Chief Marketing Officer, Jonathan Mildenhall, Airbnb is on a mission to change both “behavior and perception” so that people can “belong anywhere.”

For each of these companies, purpose isn’t something on which they spend their profits, or a strategy they devise to make more money. Instead, profit and purpose are intertwined proving that money and meaning can indeed work together.

There is no doubt that these companies have all made hard choices in executing their strategies. But the nature of “the hard choice of strategy” has changed in today’s marketplace. It’s no longer about giving up something that is important to you or your customer. In many cases, it’s about finding a way to take both paths at once. For that is truly the road less traveled.

Leading in a World of Resource Constraints and Extreme Weather

My father worked at IBM for 35 years. He told me about the days, decades ago, when he first ran into a new breed of executive and thought, “What the heck is a CIO?” These information-focused leaders emerged as the world changed and the capabilities that companies needed shifted over time. And as an HBS white paper points out, even some of today’s most mainstream executives — from the CTO to even the CFO — were once just new positions created to deal with “significant opportunities and risks emerging from technological or social disruptions.”

Today we face a set of unprecedented disruptions under the “sustainability” banner that are driving deep change in organizations (indeed, the HBS paper is mainly about the rise of the Chief Sustainability Officer). Consider three critical mega-trends: resource constraints and rising commodity prices; climate change and extreme weather; and radical, technology-driven transparency.

The issues in each of these buckets require new leadership, or at least a rethinking of it in the highest ranks of companies, and deep operational changes.

Resource constraints mean organizations have to use less stuff. When it comes to our natural resources, we are facing a combination of some shortages — like the growing water emergency in California — and extremely volatile and generally rising prices for nearly every commodity.

We’re starting to recognize that this relatively new situation has important ramifications for how businesses operate, and we’re making some progress. McKinsey, for example, recently outlined the “new organizational capabilities” that chemical companies should develop to deal with frequent oil price shocks. The advice boils down to building better strategic foresight and creating more agile management and operations.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

And while that’s all true, it does suggest that having a facile organization will be enough. The reality is that, in a world of rising and volatile input prices, companies need to be more than just flexible in how they react to changes – they also need to proactively develop new products and services that are far less resource-intensive throughout the value chain.

In other words, they need to use less stuff.

The drive for dematerialization will change job descriptions in R&D, product development, and procurement at the very least. But companies will need new positions as well. Think of appointing a Chief Circular Economy Officer, a VP of Dematerialization, or Director of Water.

Climate change and extreme weather demand resilient, flexible organizations. In 2011, floods in Thailand stranded hard drive and automakers for months without key parts. Of course nobody can predict exactly when another Thailand — or floods in Texas or deadly heat waves in India — will happen again. But we know that because of climate change, these extremes will happen more frequently. At the very basic level, protecting assets will also mean that operational leaders will move more equipment to the second floor of buildings (which one of my consumer products manufacturing clients has done in numerous locations).

But a high-performing organization should do much more than that: Supply chain and operational execs should be ready to shift production and logistics very quickly from one region to another. And more proactively, they should spreading risk by spreading production around to different regions with different outlooks for weather and water availability.

Climate change is so far reaching, companies will want some dedicated resources to manage the operational and regulatory terrain. There’s already an Association of Climate Change Officers that provides some foresight into what that emerging role looks like. Facebook employs a Green Energy Czar, so I can easily imagine a Zero Carbon leader or Extreme Weather VP. Real estate or hospitality companies with major coastal assets may want a Sea Level Rise Officer. And everyone will need a Chief Resilience Officer, although that should really be the CEO.

A connected world is a transparent world. The rapid increase in data about real-time conditions in supply chains will enable more agility. But new levels of connectivity also have another important ramification: transparency. Business customers and consumers are demanding and expecting more information on the products they buy, so most large companies will want more people and resources deeply embedded in the supply chain.

A Supply Chain Transparency VP could focus energies on reducing downside risk and ensure that they have no environmental or social skeletons in the closet. A Value Chain Perfomance czar could provide knowledge, assistance, or capital to help suppliers improve their operations. They could work with their supply chain partners to innovate and improve the resilience of the whole chain.

One of the biggest changes that ties all three of these issues together involves the speed at which organizations will need to react to them. Companies will need to “listen” to their full value chains – collecting signals of extreme weather, shortages, major price swings, or shifts in customer demands — in as close to real-time as possible. They’ll also need increasing data collection and data analytics about their products and services, about all their ingredients and inputs, and about all suppliers multiple steps upstream.

Any new roles will also require the ability to consider systems and interconnections, like the energy-water-food “nexus” that Shell worries about. Coalition-building will be crucial as well as people across the organization will want to develop unusual collaborations within the company and with NGOs, governments, industry organizations, and even competitors.

The glue holding the new skillsets and titles together will be, for now, the Chief Sustainabilty Officer, or CSO (although this acronym is also sometimes used for Chief Strategy Officer). It may sound like it’s still a new role to many, but a report from recruiting giant Heidrick & Struggles was heralding the rise of the title eight years ago. Since then, the CSO’s role has most definitely grown and gained influence, as this Atlantic article explores by featuring CSOs from MGM, EMC, Owens-Corning, and elsewhere. These sustainability execs and many more are acting as hubs of information, connections, and strategy, as well as major conduits of communication and partnership with all stakeholders. And they can sit in nearly any part of the organization and hold other titles simultaneously (like R&D at Owens Corning or Corporate Communications and Marketing at Unilever).

Of course, new roles and skills don’t appear magically — they take planning, investment, ongoing commitment, and buy-in across the organization. Given the scale of the challenges we face, the typical staffing and resources provided to the sustainability executives in particular are woefully inadequate. And the development of new skills, like systems thinking mindsets, is lagging far behind where we need to be. But I predict that outside pressures will accelerate these developments, so much so that few people will have to ask, “What the heck is a Chief Sustainability officer anyway?”

Robots Seem to Be Improving Productivity, Not Costing Jobs

Nearly 30 years ago, in 1987, the Nobel-winning economist Robert Solow surveyed the impact of IT on the economy and concluded that “you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

Solow’s quip crystallized a frustrating disconnect in the 1980s. Why did an observed technology boom coincide with a prolonged slump in the productivity data? Companies were using computers, but they didn’t seem to be getting any more productive.

Strangely, it took another seven years for U.S. productivity growth to surge. At last, the computers Solow and everyone else saw around them had become visible in the statistics. It just took a while.

Well, here we go again. Now robots are everywhere — but they are also an object of confusion.

In early April the think tank Third Way published research by Henry Siu and Nir Jaimovich that blamed robots and automation for the fact that many repetitive jobs have all but vanished from the economic recovery. And yet, as Larry Summers noted recently, for all of the anecdotal evidence that automation is prompting mass layoffs and presumably increasing productivity, the “productivity statistics over the last dozen years are dismal.”

Again, something is failing to compute. And what’s more, the fact that there hasn’t been much macroeconomic research on the impact of robots has only added to the confusion. Commentators have largely been forced to rely on anecdote.

However, empirical evidence is beginning to trickle in that could begin to clear up the current paradox. Provided in a new paper from London’s Center for Economic Research, the analysis offered by George Graetz and Guy Michaels of Uppsala University and the London School of Economics, respectively, offers some of the first rigorous macroeconomic research and finds that industrial robots have been a substantial driver of labor productivity and economic growth.

To fuel their analysis, Graetz and Michaels employ new data from the International Federation of Robotics to analyze the use of industrial robots across 14 industries in 17 countries between 1993 and 2007. What do they find? Overall, Graetz and Michaels conclude that the use of robots within manufacturing raised the annual growth of labor productivity and GDP by 0.36 and 0.37 percentage points, respectively, between 1993 and 2007. That might not seem like a lot but it represents 10% of total GDP growth in the countries studied and 16% of labor productivity growth over that time period.

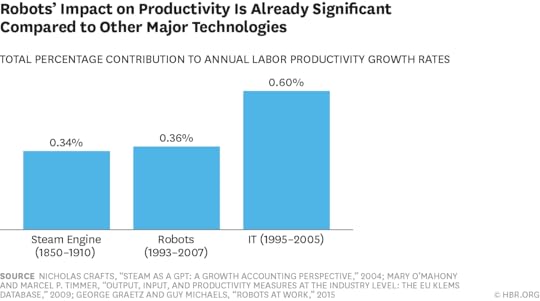

Moreover, to put that gain in context, it’s worth noting that the robots’ contribution to productivity growth in the 1990s and 2000s is comparable to that of a true “general purpose technology” (GPT) — one that has a pervasive, longstanding impact on a number of dissimilar industries. Graetz and Michaels calculate, for example, that robotics have of late increased labor productivity by about 0.35% annually — or by about the same amount as did the steam engine, a classic example of a GPT, during the years 1850 to 1910.

More recently, other analysis has shown that the pervasive IT revolution supported 0.60% of labor productivity growth and 1.0% of overall growth in Europe, the U.S., and Japan between 1995 and 2005. That’s about two to three times the amount contributed by robotics thus far but capital investment rates in IT during those years were also five times higher than those in industrial robots during the 1993 to 2007 period. As many economists have noted, productivity figure are often quite difficult to calculate in new technology categories, and could be larger or smaller than official estimates. Nonetheless, to the extent that one can trust today’s flawed productivity data, Graetz and Michaels’ work suggests the young robotics revolution is going to be a very big deal.

And yet, there is another critical question that needs asking, and that is whether the robots’ productivity impacts are resulting in job losses.

Consider that between 1993 and 2007 (the timeframe studied by Graetz and Michaels) the U.S. increased the number of robots in use as a portion of the total hours of manufacturing work (a standard measure of economic output) by 237%. During the same period the U.S. economy shed 2.2 million manufacturing jobs.

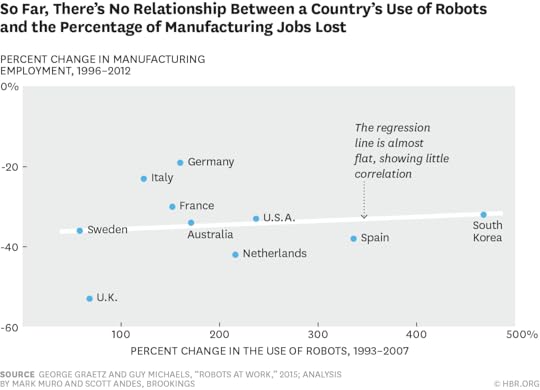

So is there a relationship between the use of industrial robots and job loss? The substantial variation of the degree to which countries deploy robots according to Graetz’ and Michaels’ data should provide clues. If robots are a substitute for human workers, then one would expect the countries with higher investment rates in automation to have experienced greater employment loss in their manufacturing sectors. For example, Germany deploys over three times as many robots per hour worked than the U.S., according to Graetz and Michaels, largely due to Germany’s robust automotive industry, which is by far the most robot-intensive industry (with over 10 times more robots per worker than the average industry). Sweden has 60% more robots per hours worked than the U.S. thanks to its highly technical metal and chemical industries.

However, these data don’t compute with expectations. By our calculations there is, as yet, essentially no visible relationship between the use of robots and the change in manufacturing employment. Despite the installation of far more robots between 1993 and 2007, Germany lost just 19% of its manufacturing jobs between 1996 and 2012 compared to a 33% drop in the U.S. (We introduce a three-year time lag to allow for robots to influence the labor market and continued with the most recent data, 2012). Korea, France, and Italy also lost fewer manufacturing jobs than the United States, even as they introduced more industrial robots. On the other hand, countries like the United Kingdom and Australia invested less in robots but saw faster declines in their manufacturing sectors.

For their part, Graetz and Michaels also see a lot of ambiguity when it comes to robotics’ influence on the labor force. They cannot rule out that there is no effect of robot densification on national employment levels. But they do see variegated skill-biased impacts. Specifically, their data suggest that the arrival of robots tended to increase the employment and pay of skilled workers even as it seemed to “crowd out” employment of low-skill and, to a lesser extent, middle-skill workers. So while robots don’t seem to be causing net job losses, they do seem to change the sort of workers that

are in demand.

In the end, the new data are important because they dispel at least some of the robotics productivity paradox. Assuming more analyses fall into line with Graetz’ and Michael’s work it will be possible to say that robots have become visible in the productivity data — and that the data and observed realities match up and can be useful. In addition, the scale of the robots’ impact — even with technology improvements racing along — suggests that robotics may well be a big thing: a general purpose technology that over time pervades the economy, spawns myriad new innovations, and elevates productivity for years, with major impacts on society. No, we’re not there yet, as Summers notes, but the evidence suggests that day is coming. As to the bots’ impact on employment, that is less clearly visible, and may be positive, negative, or mixed. Yet if the IT experience is any indicator, full adoption of a powerful technology can take a generation, and come after years of delay. In that sense, while it’s early, the advent of the robots is beginning to conform to expectations.

What Makes FC Barcelona Such a Successful Business

“Blue and claret blowing in the wind. One valiant cry. We’ve got a name that everyone knows: Barça, Barça, Baaarça!” So runs the battle hymn of FC Barcelona (aka Barça), the Catalan soccer club that won the UEFA Champions League — the world’s most prestigious inter-club soccer championship — earlier this month, defeating Italy’s Juventus 3-1.

With 23 Spanish League championships, 27 Copa Del Rey titles, and, after this last victory, as many as five Champions League trophies under its belt, Barca has earned a unique place in the annals of soccer. It’s also a successful business: the team’s net worth, according to Forbes, was $3.16 billion, making it the world’s second most valuable sports team, while its revenues touched $657 million, the fourth highest among soccer clubs (after Real Madrid, Manchester United, and Bayern Munich) in 2014.

There are many reasons for Barça’s sustained excellence: great players such as Lionel Messi, Neymar Santos, and Luis Suarez; terrific managers like Johan Cruyff, Luis Enrique, and Josep “Pep” Guardiola; and state-of-the art facilities. However, our research suggests that Barça’s organizational identity — the collective sense of “who we are” that players, managers, and employees share — lies at the core of its success. Such is the power of its identity that fans often say that Barça is més que un club (more than a club).

Identity is different from culture, the values, beliefs, and assumptions that establish behavior. While culture tells us how to behave, identity tells us who we are. That serves two purposes. By serving as a lens, identity helps make sense of the environment. It also informs action by guiding employees’ responses. Together, these dimensions allow organizations to maintain a sense of balance between “who we are” and “what we do.”

While most organizations have some understanding of their identity, few think of it as a way of driving performance. For many, identity is too abstract a concept to link to measurable objectives; for others, it is too long-term an ideal to translate into current goals. Yet, identity has the potential to infuse objectives with meaning and to deliver great results — as Barça has demonstrated.

Coaches and players may come and go, but the cornerstone of Barça’s identity is La Masía (The Farmhouse), the club’s youth academy located inside Joan Gamper Sports City on Barcelona’s outskirts. Since its creation in 1979, the school has educated over 500 aspiring players including stars such as Messi, Xavi Hernández, and Andrés Iniesta. Around 85 players, between the ages of 12 and 18 years, either live in or visit the school every day for education and training.

La Masía helps create Barça’s identity by playing four roles:

As the guardian of the organization’s ideals. One of Barça’s ideals is that soccer must be played skillfully and in an artistic fashion rather than relying on sheer strength and size. According to the club’s stakeholders, that belief lies at the heart of the club’s identity. La Masía, where the club grows its players, is responsible for imprinting that ideal in the youngsters that join its ranks every year.

Training at the school has a moral edge, agrees Albert Capellas, Barça’s former senior youth coordinator: “First, we must be the more sporting team, committing fewer fouls [than opponents]. Then we must try to win by playing more creatively than the opposition. Finally, we must win. But we don’t want to win without adhering to the other two ideals.”

As the source of the organization’s distinctiveness. Barça’s ideals translate into a distinctive kind of playing style known as tiki taka soccer, which relies on quick, short passes among players who advance in concert. (See, for instance, “Learning Collaboration from Tika Taka Soccer“) Passing is more important than shooting; smarts are more relevant than strength. It takes a special kind of player to thrive while using this style. Therefore, La Masía’s recruiters often take chances on kids who defy stereotypes.

They try to find children who make quick decisions in counterintuitive ways. For example, when Barca’s scouts found Messi in Argentina, he was smart but short and thin; he suffered from acute growth hormone deficiency. Other clubs thought he was too risky an investment, but Barca wooed the young Messi, paid for his treatment, and then, coached him into one of soccer’s all-time greats.

As the glue which imparts cohesiveness. Another characteristic of Barca’s identity is collaboration and teamwork. Because tiki taka soccer requires the team to move in unison, it calls for every player to be aware of his peers’ positions on the field and passing opportunities. There’s no room for lone stars; the team must act as a cohesive constellation in order to win.

While players who have grown up at La Masía understand this, those who join from other clubs have a tough time adjusting to it. For example, two of Barca’s current forwards, Neymar, who came from Brazil’s Santos, and Suárez, who transferred from England’s Liverpool, have spoken freely about the change in mentality they had to undergo after joining Barça. They started playing well – and enjoying the game — only when they let go of their personal aspirations and concentrated on supporting their colleagues on the field.

As the compass that points to the organization’s future. Like most organizations, Barça operates in a fast-paced environment with ambitious short-term goals. Its focus is on winning this week’s match and this season’s tournament; it’s easy to forget about the long term. In contrast, it takes around 10 years of coaching for a player to make the grade from La Masía to Barça’s first team.

The pressure to perform can be staggering, but trainers understand that rushing the development process compromises quality. “If you are forced to show immediate results, you are doomed. We need to be humble enough to understand that the fruits of the seeds we are planting may not be enjoyed by us, but by future generations,” points out Jordi Mestre, Barça’s board member in charge of youth soccer.

Interestingly, La Masía trains youngsters in soccer for only 90 minutes a day, during which the coaches focus on mastering ball control and tactics. The rest of the time is devoted to educating young minds and developing good attitudes around principles such as respect, responsibility, commitment, discipline, and humility.

In addition, cultural activities help expand the young players’ horizons and foster their curiosity. For instance, La Masía regularly invites guests — cardiologist Valentin Fuster, rock rumba music group Estopa, master chef Ferran Adrià, Albert Bosch, the first Catalonian to reach the South Pole etc. — to inspire its residents.

The ways in which La Masía nurtures Barça’s identity results in one key capability: talent development. While most soccer clubs rely on acquiring star players to win, Barça is able to grow its key players at home. When Barça won the 2011 UEFA Champions League, seven of its starters were La Masia products as were eight members of the Spanish team that won the FIFA World Cup in 2010 – unprecedented in the soccer world.

At the same time, Barca can maintain its identity only if players don’t leave. Says La Masia’s director Carlos Folguera: “Every player must think that ‘I will not let go of this for anything; I am part of something historic.’ That’s why we foster our identity like a protective shield.” The philosophy has worked, judging by Barca’s continued success.

Like Barça, corporations can benefit from creating stronger identities. In hyper-competitive markets, instead of focusing on what they’re good, most companies tend to react to rivals’ strategies. A clearer definition of “who we are” that speaks to what is core, distinctive, and enduring about the organization acts as a powerful tool for strategic adaptation. It also helps answer key issues such as: Should we acquire that company? Should we enter that market? Should we develop such a product?

Executives can also shape the organization’s identity over time by sharpening and growing the meanings associated with it, so the organization isn’t trapped by inertia. After all, every identity evolves over time.

Why Some of Us Dread Going on Vacation

There is a paradox around vacations. We all know that it is important to get away from the office periodically. Time away from work gives you a chance to relax, to reduce stress, renew your ties with your family, and to get away from problems you have struggled with so that you can think about them differently on your return to the office.

However, as a vacation approaches, we generally look at it with dread. There is too much work to be done! There are new projects starting and others that need to be completed. How could we possibly have selected this particular week to go away? It can get so bad that you might think twice before planning another trip.

Why is it that a vacation seems like a great idea when we first plan it, but feels like more and more of a burden the closer it gets?

It all comes down to distance.

Over the past 15 years, quite a bit of research has focused on what Yaacov Trope and Nira Liberman call construal level theory. The idea is that the more distant some object or event is for you, the more abstractly you think about it.

Distance can refer to physical distance, but it can also mean distance in other dimensions like time or social structure. So, an event that won’t happen for six months is distant, while an event that is happening later this week is near.

You and Your Team

Vacation

Make the most of your time away.

Abstractness refers to the level of detail that is captured in your thoughts about the object or event. When a vacation is far off, you focus primarily on general characteristics, such as “This vacation will be so much fun,” “I can’t wait to sit on the beach and relax,” or “I love visiting new countries.” At a distance, most of your thoughts are focused on these desirable aspects of the trip.

As the vacation gets closer, your thoughts become more specific. All of the details that are required for you to go on the trip come into view. You think about getting your passport renewed or reserving space on an excursion. You also start thinking about how to structure your work so that you can get away. You consider meetings you will miss, events that need to be rescheduled, and responsibilities that need to be shifted to someone else.

When you contemplate the number of changes that have to made to accommodate your vacation, you begin to wonder why you ever agreed to take the trip at all.

Because it really is important to get away, you should not add stress to your vacation by questioning your decision to go away. When you book your next trip, remind yourself of what you are going to feel like as the trip nears by imagining that you actually had to go on the trip next week. Look at your schedule and recognize that you will be busy no matter when you decide to go away. If it’s really a problem, start planning earlier – get your passport renewed well ahead of time, and book that excursion sooner too.

Then, remember that all of the work you miss will be waiting for you when you get back. If it is important, and you are the person who has to do it, it will be there on your return.

Finally, look back at your life over the last five years. How many specific weeks of your life can you remember? Chances are, most of the things you remember involve changes to your routine rather than business as usual. Your trips, family events, and new experiences are the ones that stick out in memory. Don’t let the mad rush the last week before you go away dissuade you from taking more trips in the future.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers