Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1281

June 22, 2015

Is Your Supply Chain Ready for the Congestion Crisis?

A few years ago one of us (George) and his wife decided to sell their large house in the center of Toronto. With only one of their six children living at home, now was the time. But who in this age of smaller families would want our house? To our surprise, it sold in 20 minutes for 25% more than the asking price. A childless couple who lived 20 miles away bought the house because they were sick of commuting into the city!

Longer commute times are just one sign that congestion is creeping into our lives. Highways and bridges are in desperate need of repair, making travel slower—and more dangerous. Our overburdened air-traffic-control system struggles to deal with increasingly crowded skies. Port congestion is a growing problem, exacerbated by the new super-size container ships that take far longer to unload than older, smaller ships. “Expect delays” has become the recurring theme of our transportation system.

With growing congestion a global megatrend, companies have a choice. Either accept it (and its higher costs and lower profits) or take control of your fate with strategic, game-changing actions that cut time and costs from the supply chain.

A looming crisis. First, it’s important to understand the magnitude of the coming congestion crisis and its underlying drivers. These include the following:

Not enough port container capacity. Until the summer of 2008, container ports on both the west and east coasts of North America were nearing capacity as imports and exports soared. Then the recession hit, and the problem receded as port traffic slowed. But now the problem is back with a vengeance. Shipment volumes through North American ports, which fell 20% in 2009 from a record peak in 2007, are now higher than they were in 2007, and port-expansion plans from Vancouver to Los Angeles/Long Beach are bogged down by political wrangling.

Railway systems are near capacity. For instance, the average transit times to move containers from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach to Chicago grew from 84 hours at the end of 2004 to 120 hours by early 2015.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

Highways can’t keep up with demand. The highway systems in North America and Western Europe are also feeling the strain. The United States greatly expanded “lane miles”—one measure of capacity—in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s but not much since then. Meanwhile, the load factor on the system has been doubling every 30 years. Today, the load factor (total vehicle miles traveled divided by lane miles) is growing more than 10 times faster than capacity is.

Air freight isn’t the answer. Airports in North America are slowed by outdated traffic-control systems, limited runway capacity, and a shortage of fuel-efficient air freighters. In the last 40 years, only three major new airports have been built in North America: Dallas-Fort Worth, Montreal’s Mirabel, and Denver International. All of them replaced existing airports. Expansion of runway capacity in the United States also has been limited. Since 1975, just 41 new runways were planned, and only 25 were actually built, each with an average construction time of about 11 years! Lobbying by special interest groups got in the way.

The impact on supply chains. The shortage of transport capacity relative to demand will have a profound effect on businesses. For instance, Procter & Gamble’s logistics costs already exceed such key value-adding costs as manufacturing, even though the company mainly ships by land. Longer supply chains also increase inventory levels and carrying costs related to financing and warehousing.

These are just the first-order costs of congestion. The second-order costs are even greater. Companies can easily match supply and demand if demand is steady over time with no change in volume or mix. But as soon as demand changes, supply levels at each step of the chain must adjust. Given the lag time before changes in demand are actually felt by different players along the chain, their effects are amplified when they hit, leading to inventory shortages or pile-ups. Then, companies tend to overcompensate by stopping or increasing production lines, and inventory levels can fluctuate wildly. This is the “whipsaw” effect, and congestion can exacerbate it.

The associated costs can be significant: Lost profits from a stockout equal the gross margin of a product—generally in the range of 20% to 50%. Product overstocks result in discounted prices, which are usually about half to two-thirds of the gross margin. Congestion-driven losses from stockouts and overstocks are overwhelmingly greater than the direct costs of congestion but often remain hidden because they may not be measured or called out.

The bottom line: Companies must redesign their supply chains or become victims of the direct and indirect costs of increasing congestion.

What companies can do. Companies can minimize the business impact of congestion—and gain a strategic advantage over less-prepared competitors—by enhancing their supply-chain performance in four critical ways:

Improve process efficiency. Speeding up value delivery can result in remarkable performance improvements. For instance, a 25% reduction in the time needed to deliver a product or service can double the productivity of labor and of working capital. And our experience over the years at BCG is that a business that can deliver value twice as quickly as its competitors will grow twice as fast and be three times more profitable.

Improve information flows. Supply-chain speed and agility sharply increase when information is shared across the network. Walmart’s Retail Link offers an electronic bridge to the retailer’s suppliers, providing data on sales and inventory levels and allowing them to download purchase orders. This close integration gives suppliers a better sense of true demand, which can reduce the effects of congestion throughout the supply chain.

Reduce variability. The longer your supply chain is, the greater the risk of variability. But much supply-chain variability is self-inflicted, the result of inadequately informed planning and needless complexity in processes, products, and portfolios. As noted above, improving process efficiency will reduce cycle times, a good first step toward reducing variability. But companies should also look for ways to shorten and simplify their supply chains by shifting away from high-volume, world-scale plants that make just a few products to smaller plants that make a wider range of products closer to local markets. Increases in unit-production costs are often offset by lower logistics costs, faster replenishment cycles and fewer stockouts and overstocks. The same logic can apply to distribution logistics when global distribution centers are replaced by regional warehouses.

Compress transit times. Besides improving process efficiency and shortening their supply chains, companies can improve cycle times by rethinking how they transport their goods. One tactical approach is to make more use of air freight. Air cargo costs per ton are four to six times greater than on-ocean shipping costs, which account for 0.5% to 2% of the shelf price of most products. For the right products—those with high margins, a limited shelf life, or short product life cycles such as fashion and technology items—the added costs of air freight are more than offset by the positive impact on profits of fewer stockouts and overstocks. Air freight can cut weeks from the time it takes to ship from China to North America and Western Europe.

In the end, the above four are just tactics. Real benefits—growth and profits—come when these tactics are employed in a differentiating strategy that exploits congestion. For example, one possible strategy is building dominant share positions with those customers who value faster, more reliable responses from their suppliers.

Such tactics and strategies for improving supply-chain performance can increase market share, reduce costs, and dramatically improve profitability. Companies that take action now can turn the looming congestion crisis into a major strategic opportunity. Use it against your competitors before they use it against you.

An HBR Refresher on Breakeven Quantity

Marketers often have to make the call on whether a certain marketing investment is worth the cost. Can you justify the price tag of the ad you want to buy or the marketing campaign you’re hoping to launch next quarter? One of the most straightforward ways to answer this question is to perform a breakeven analysis, which will tell you how many incremental units you need to sell to make the money back that you put in.

While the concept may be straightforward, the calculation and the assumptions underlying it are far from simple. I talked with Jill Avery, a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School and co-author of HBR’s Go To Market Tools, to better understand how to use this important calculation.

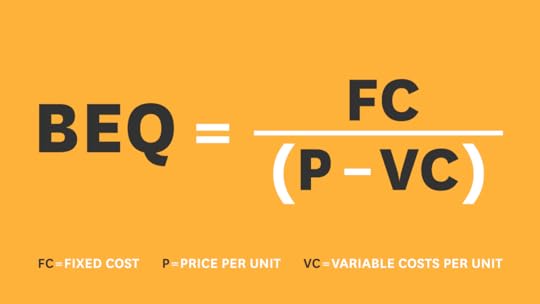

What is breakeven quantity (BEQ)?

“Breakeven quantity is the number of incremental units that the firm needs to sell to cover the cost of a marketing program or other type of investment,” says Avery. If the company doesn’t sell the equivalent of the BEQ as a result of the investment, then it’s losing money and it won’t recoup its costs. If the company sells more than the BEQ then it not only has made its money back but is making additional profit as well.

“It’s one of the more popular ways that managers calculate marketing ROI,” says Avery, pointing out that other common ones include calculating the investment payback period, calculating an internal rate of return, and using net present value analysis. “I like breakeven analysis because it is easy to understand and it’s often the simplest way to think about return on investment.” The other forms of ROI often require a more complex understanding of financial concepts such as the firm’s cost of capital or the time value of money.

How do you calculate it?

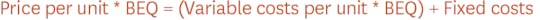

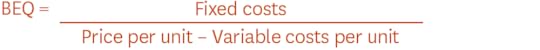

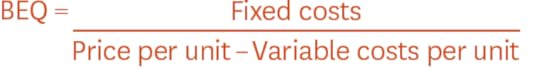

To figure out BEQ, start by setting up an equation where Total Revenue = Total Costs, which will mathematically represent the point at which profit is equal to zero, i.e., where you will break even:

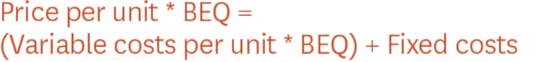

Then you have to find a unit quantity — your BEQ — that makes both sides of the equation equal. The BEQ will be present on both sides of this equation because the number of units sold affects both the revenue the firm earns as well as the costs it must incur to earn it. Revenue is the unit quantity sold multiplied by the selling price per unit. To figure total costs you first multiply the unit quantity sold by the variable costs per unit, then you add the fixed costs. So it looks like this:

You then reorder the equation to solve for BEQ. Like this:

Note that Price per unit – Variable costs per unit is equal to the Contribution margin per unit.

So to calculate BEQ you need to know the fixed costs for your program and the contribution margin per unit.

Take this example of a company that sells flip flops from Avery’s teaching note, “Marketing Analysis Toolkit: Breakeven Analysis.”

The company sells each pair of flip flops for $24.00. The variable costs to make each pair of flip flops are $14.00. (Note: variable costs are per unit costs that vary depending on a company’s production volume. They rise when you increase production and fall when you decrease it.) The fixed costs to advertise the flip flops are $2,000. So, how many flip flops does the company need to sell to breakeven on its advertising expense?

First, look at fixed costs. No matter how many flip flops are sold the cost of advertising remains the same: $2,000. Note that most companies’ fixed costs are much more complex and often include rent, advertising, insurance and office supplies but since we’re trying to evaluate the BEQ for the $2,000 advertising campaign, we focus just on this number.

Then you take the price of the flip flops and the variable costs and put them into the equation like this:

BEQ = $2,000 / ($24-$14)

or

BEQ = 200 units

So if the managers at this flip flop company believe they will be able to sell more than 200 extra pairs of flip flops because of the advertising campaign, they will recoup their costs and it will be a worthwhile investment. But, if they don’t believe that the advertising campaign will drive enough incremental demand for flip flops, then they shouldn’t run it. It will not breakeven.

How do companies use BEQ?

The above is a simplified example but most companies use BEQ in a similar way. “It’s a pretty universal tool. It can be used to evaluate any investment from a marketing campaign to a decision about whether to build a new factory,” says Avery. However, she says, it’s particularly useful for marketing because it relates the cost of a marketing program to the program’s ability to affect consumer demand for a product. “It most closely relates one of our main goals in marketing, to generate demand, to the costs that we incur to achieve it.”

Among marketers, it’s most often used to do one of several things:

Assess the feasibility of a marketing expense, such as an advertising campaign (as we did in the flip flops example above). This is most common use, says Avery. Typically the campaigns are more expensive then the $2,000 the flip flop company was considering. So a manager may consider, If I’m going to spend $10 million on a marketing campaign, how many additional units of my product do I need to sell to breakeven on the investment? The formula will tell the manager how many units will result in $10 million in profit.

Managers will also use BEQ to assess the feasibility of a permanent price change, either an increase or a decrease. “Pricing changes are complicated because when you change price, you inherently effect demand. You have to think through what happens to demand before you can determine the effect of the price change on your business,” says Avery.

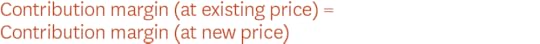

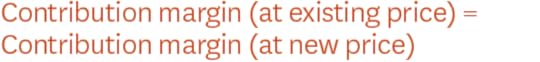

So the question for marketing managers here is How many more units of a product must be sold to compensate for the lower price? You can use the same BEQ equation above to determine how much additional demand you need to generate. You start by setting an equation with the current contribution margin equals the contribution margin with the new price:

For example, let’s say your current demand is 100 units at a price of $10.00, but you want to lower it by $2.00. If the product has a contribution margin of $5.00 (at the $10.00 price) and therefore $3.00 (at the $8.00) price, then the equation would look like this:

$5.00*100 units = $3.00*(100 + BEQ)

Then you solve for BEQ:

3*BEQ = 500 units – 300 units

BEQ = 200 units / 3

BEQ = 66.7 units

So you have to be confident that you will sell at least 67 additional units at the lower price (or 167 units in total) to justify the price decrease.

The calculation works similarly if you’re considering raising your price but instead of looking at the number of additional units you need to sell, you’re considering how many units can be sacrificed if you’re getting the higher price. So again, you set it up so the contribution margins are equal:

Contribution margin (at existing price) = Contribution margin (at new price)

Then, let’s say you wanted to raise your price by $2.00 and therefore your contribution margin at the $12.00 price would be $7.00.

$5.00*100 units = $7.00*(100 + BEQ)

Solving for BEQ:

7*BEQ = 500 units – 700 units

BEQ = -200 units / 7

BEQ = -28.6 units

In this case, you need to be sure that you will lose 29 units or fewer if you raise your price (or sell 71 units in total).

Marketing managers can also use BEQ to assess the feasibility of a short-term marketing expense, like a coupon promotion, or the feasibility of a new product introduction that will cannibalize existing product sales.

What are some of the common mistakes managers make when using BEQ?

First off, it’s important to keep in mind that the BEQ is a measure of the incremental units needed to be sold to justify the investment. So these are additional units that you have to sell because of the price decrease or the marketing campaign. “Some managers think, ‘Sure, we can do 200,000 units.’ But the real question is can you do what you did yesterday plus 200,000 units,” Avery explains. And for many managers, says Avery, determining what is incremental can be tough. Would you have sold the same amount without the coupon or the sales promotion? Or has the coupon forced people to “pantry load” — stock up on a product because it’s cheaper now? If razors are on sale at Costco some consumers will buy all the razors they need for the next year. “We want marketing investments to generate incremental demand and not cannibalize what we would sell anyway, switching tomorrow’s demand for today’s demand,” says Avery.

This is where “the art of marketing comes in,” she says. You have to look at the data available to you — including internal and external benchmarks — to assess whether you believe that you can sell that many more units. Avery suggests asking: What have we done before and what has that yielded? And what have competitors done and what has that done for them?

Another mistake that managers make is forgetting to consider the length of time it will take to hit the BEQ. “If the 200,000 additional units represents two months of sales, that may seem reasonable but if it will take two years to sell 200,000 units, that’s often a different story,” says Avery. This is where payback period comes in, and it can often be helpful to run a payback period analysis in conjunction with BEQ (for help on how to do a payback period analysis, check out the HBR TOOLS: Return on Investment).

There is also room for error in the various assumptions that go into the BEQ calculation. Avery says that the cost of the marketing program, for example, can be difficult to pin down ahead of time. She gives the example of a couponing program, where you won’t know the total cost until the redemptions come in. In these cases, you want to do a sensitivity analysis and run the calculation using several different numbers. “If you want to be conservative, overestimate the cost,” says Avery. “That will give you a higher BEQ number and therefore a higher threshold to meet.”

The biggest mistake people make, however, says Avery, is not even running a breakeven analysis. “Too often, marketing budgets are just spent because that’s the way we’ve always done business and there is little effort to justify the expense,” she says. Many managers don’t even run an ROI because the costs of programs and the incremental demand can be hard to determine ahead of time. “There’s often a lag time between when we spend and when we see results so programs can be hard to measure.” Even if the numbers are tough to get right in advance, Avery says, it’s simply good marketing management to understand how well you’re spending your dollars, even if you run the analysis in retrospect to help you make future decisions.

“Breakeven analysis imparts discipline into marketing decision making,” she says. You need to understand what you are trying to achieve, what it will cost you, and then how likely it is to succeed.

You can learn more about breakeven analysis by using the interactive in this piece .

How to Be a Pro-Vacation Manager in a High-Pressure Industry

The financial services industry is known for having a high bar and a strong work ethic. It’s difficult for people in the industry to step away from their work due to the fast-paced, high-pressure environment. Yet, the benefits of taking a break are indisputable.

A colleague once told me about a particularly memorable vacation she took during her second year as a banking analyst, at another Wall Street firm. She’d been working long hours, but had finally found herself in a position to afford a well-deserved, special vacation. So, she chose Australia and let her manager know that she’d be gone for two weeks. The response was disappointing: “Don’t do that,” her manager had said, “it will reflect badly upon you.” Not to be deterred from taking the vacation she had earned, my colleague went anyway, leaving her work in capable hands during her absence. When she returned from Australia, refreshed and re-energized, she found that she’d been essentially de-staffed from all of her pre-existing projects, as someone else had been assigned to take the lead on them in her absence. She was open to taking on new assignments, and was soon loaded up with new deals—big, blue chip deals—and her exceptional performance on them became the hallmark of her junior career. They eventually helped her move up the ranks to associate and beyond. In the end, the benefits of my colleague’s vacation were two-fold: she was able to disconnect from the high pressure environment and come back from vacation feeling renewed and clear-headed; at the same time, she had the newfound energy to dive head-first into the new deals on which she’d been assigned and lay the foundation for her blossoming career.

You and Your Team

Vacation

Make the most of your time away.

If your employees are the drivers of your business success, as ours are at Blackstone, then it’s critical to encourage them to take time to recharge. There is a way to balance the rigors of the business and the well-being of your people. It takes a “pro-vacation manager” to strike that balance, but how do you actually become one?

Set expectations

Ask your team about their vacation plans. If they don’t have any yet, ask them to prioritize a vacation, and then follow up with them to make sure they do.

Don’t accept the “it’s not a good time” excuse; while some times are clearly not optimal depending on the role and responsibility, there is never really a “good” time. Encourage your employees to make time.

Create a contingency plan

When a key player is away from the office, take stock of the big ticket items that are going on during that time. Who is going to drive deliverables in that person’s absence?

Work together to identify someone you both trust to be accountable and agree on a plan of action to ensure that nothing falls through the cracks.

Observe some boundaries

There’s nothing worse than getting all the way to your tropical island destination only to discover that you have 150 unread emails, all of which are flagged as “urgent.” Only email your vacationing team members when absolutely necessary.

If you’re a “pro-vacation manager,” follow the contingency plan you agreed upon. Make sure those who are accountable are copied on everything so that the vacationer can feel some peace of mind.

In the event of a real fire drill, respect your employee’s time and minimize the interruption.

Get some perspective

Put yourself in your employee’s shoes. How would you feel if your phone rang off the hook for a week straight as you attempted to ride rollercoasters with your kids?

Give your vacationing team some distance to disconnect from the office—resist the urge to check in to see how it’s going or to follow up on items you may have worked on recently together.

Lead by example

Your team will do as you do. Show them you mean what you say by ensuring you take time away from the office to re-charge and unplug.

Put away your devices while you’re on vacation. Designate a couple of consistent times per day, so your team knows when you will be checking in. The rest of the time, refresh and relax. You will return a better leader and manager, and a more productive and constructive member of your firm.

If you encourage your employees to take the vacations they need, let them fully disconnect, and make sure they don’t return to chaos, you’ll be rewarded by an energetic, dedicated, and highly effective team.

The Leadership Behaviors That Make or Break a Global Team

We’re all familiar with the promise of global operations. It’s not just about accessing big new markets—the bigger payoff, most people agree, comes from expanding the firm’s talent pool and bringing together a diversity of perspectives that will combine to make the firm more productive and innovative.

Well, that’s the idea, but as many people who’ve actually worked on a global team know, the reality often feels very different. The team from head office feels like it’s carrying the folks working remotely, while the latter feel they’re ignored and undervalued.

To get insight into how to stop that from happening, I recently visited professor Tsedal Neeley, who studies and teaches global teamwork at Harvard Business School. What follows is an edited version of our conversation

HBR: What is the biggest challenge of leading a global team?

NEELEY: Social distance is one of the greatest barriers to effective teamwork. In the context of teams, the term denotes a lack of connection between co-workers or colleagues and is sometimes referred to as psychological distance. Without a sense of connection, it is very difficult for co-workers to get on the same page about their work, whether they’re determining how to accomplish a task or thinking about a process for doing a task. Overcoming social distance is more challenging in the context of global teams because when all of a team’s members are nowhere near each other, it’s all the more difficult for them to agree on how to coordinate their work.

What causes social distance?

There are five ways in which social distance gets created and you have to manage each differently. To begin with, team structure—the physical configuration of the global team, how many people are in what location, not to mention where the leader is. Then there are the processes that you use for managing team interactions—without carefully managing communication, team interactions can end up as a dialogue of the deaf. Language is a third source: all teams have a common language but when some people are more fluent than others, it creates social distance between members. The fourth source is identity. The ways in which global team members define themselves (through culture, religion, and gender, for instance) affect team dynamics and mutual trust and require careful management. Finally, you have to be savvy about how you use communications technology. We often assume that mediating technologies like email or instant messaging or Skype or conference calls are neutral and benign. But the way we use them can decisively shape relationships among global teams.

Supposing you’re leading a global team working in multiple locations and you feel one of the members is out of the loop. What can you do to fix that?

First off, you have to increase your contact with that person. He or she has to feel your presence. It doesn’t really matter how—you can use instant messaging, you can text them, you can call them, send them e-mails, obviously—the point is that you really have to make the person feel that you think he’s important. Then, when you have group meetings, invite him to speak up. Make him the first person you ask for a comment or reaction to a particular suggestion. This demonstrates to the rest of the team that the person is valued and important. Also, think hard about how much this person gets inconvenienced in terms of time zone differences. Is she regularly taking calls with the team at 10 pm her time? If she’s the one who always has to compromise her schedule she’s likely to feel less important because of that.

Getting a person to participate more in meetings is obviously difficult if the person struggles with the team’s common language. How can the team leader help there?

People who are less fluent have a tendency to withdraw from communication, which means the team may not get all the input it needs. As a leader, therefore, you have to make sure that your fluent speakers make room for less fluent speakers to communicate. Again, this is going to involve calling on the weaker linguists in meetings when you feel their expertise is relevant. It means maybe limiting the dominance of the stronger linguists. And don’t try to speak for people or interpret them, because that can destroy their confidence as well.

You and Your Team

Leading Teams

Boost your group’s performance.

The good thing is that language imbalances are predictable. When you put a team together you can tell which ones are comfortable in the team’s chosen language, which means you can formulate an explicit team strategy for dealing with fluency differences. Get the weaker speakers some formal language training ahead of and during the project and get them to formally commit to participating. Get stronger speakers to make it a goal not to talk too much.

How does a team leader develop trust with distant employees?

All employees want leaders to be fair and to respect them and they’re always looking for reassurance on this score. In a global team, whose leader is remote and an unknown, the anxiety levels are high on this score and so team members are constantly on the lookout for cues about what leaders feel and think about them. On your visits and in video-calls they watch what you say and how you say it very carefully and are hungry for information about you and what you are likely to think about them. They’ll pore over your e-mails. And of course they’re watching you around your decisions, they’re watching how you treat them, they’re watching the extent to which you help them remove obstacles so that they can be successful at their jobs.

A good way to build confidence in this highly charged atmosphere is to disclose some information about your vulnerabilities because that will lower the anxiety levels. If they see you recognizing your fallibilities they’ll be less worried about their own. What’s more, by opening up, you’re modeling the types of behaviors that you want your team members to adopt and creating a context of psychological safety. This makes it more likely that people will speak up honestly when mistakes have been made. As we all know, people worry a lot about the impression they make, and this is precisely what you want to avoid.

What’s the single most important piece of advice you have for someone leading a global team?

Think of the job as a combination of being in several marriages at once and being a parent at the same time. You’ve got to constantly work on your relationship with every member of the team. You’ve got to schedule date nights with each of them. And never, ever take your relationships for granted. In co-located teams you can afford to ease up on the communication pedal once the project gets under way and coast until something important changes or a new member joins the team. People see you around and feel reassured. But with global teams, the members just need more from you. They will worry about late replies: “I sent the boss an e-mail last night and she still hasn’t gotten back to me. Is something wrong?”

At the same time you’ve got to manage your team members’ relationships with each other. In co-located teams people can manage relationships with each other quite easily—they’re physically nearby, culturally close, and there’s always time for the water-cooler chat. With global teams you’ve got to step in as a leader to help your members learn to communicate directly and be ready to moderate if need be.

I can’t emphasize enough how important the leader is to the success of a global project. Most times, when we pick a team leader we’ll weight the leader’s credibility on the task—look at their track record in this line of work. But if it’s a global team, we need to emphasize the people skills, especially their ability to manage distance, not just mastery of the subject matter.

June 19, 2015

How to Negotiate for Vacation Time

Marisa recently received a job offer from a major food service retailer to lead their continuous improvement group. Having previously worked for a small consulting company, where schedules were entirely self-directed, she’s unclear about how to negotiate benefits with a large company that seems to have only standard and rather rigid packages.

Tom, the director of portfolio marketing in a financial services firm, was delighted when his boss offered him a promotion to group vice president. But he was equally disappointed to learn that, due to challenging business conditions, the company would not be able to increase his compensation accordingly.

Jennifer, the VP of health policy and strategy at a major consulting firm, is tasked with rolling out a new service to three major clients. Since this will require her and her team to work pretty intensely for six weeks, she thinks everyone (including her) will need a respite after it’s complete.

You and Your Team

Vacation

Make the most of your time away.

Each of these leaders is poised to enter a negotiation about vacation. Marisa needs to let her potential employer know that she considers time off a key component of her compensation. Tom should consider whether his promotion could come with different perks, since a pay increase isn’t possible, and ask his boss about it. Jennifer has to create her own bargaining opportunity since there’s no clear structure for discussing rewards for work well done.

Each situation is different. But here are a few negotiation principles that might help in any of them.

Figure out what you want. You won’t be able to negotiate without being clear about this. All too often when people are offered new jobs or promotions, they focus only on salary, bonus and stock options instead of considering the entire package, including vacation. What is most important to you and where you are willing to make trades? Marisa thinks carefully about how much she values extra holiday and whether she’s willing to concede on any financial aspects of the retailer’s offer in order to get it. Tom considers what his raise should have been and how much holiday he desires in lieu of it. Jennifer weighs the amount and timing of days off that her team needs to relax and feel appreciated.

Benchmark the norms. It is difficult to negotiate in an information vacuum. You need to learn — usually through your network — what is normal. What have people in similar situations negotiated for? What is standard at the organization and what special requests have colleagues made — and been granted or denied — in the past? Benchmarking can give you confidence by ensuring that you’re not demanding too little, or too much. Tom asks a few trusted colleagues at his company and learns that some people in his situation have just taken the title and nothing else but that others have negotiated for some form of deferred compensation or more vacation days. Jennifer’s network tells her that timing is important: she should broach the idea of compensatory time off with her boss at the start of the project so he’s prepared for a more formal request later.

Have options to propose. You want to make it easy for your counterpart to agree to your request, and research consistently shows that negotiation outcomes are most successful when parties propose multiple equivalent options. Marisa proposes two packages — one with a higher salary and bonus than the retailer had initially offered plus a standard three-week vacation; another with the same higher salary but a phased-in bonus that would start accruing after six months and a four-week vacation. Tom asks his boss to either reconsider whether the company can offer a pay raise with his promotion or instead think about giving him extra time off immediately and a promise to revisit the pay issue when the company’s financial situation has improved. Jennifer also presents two options to her manager: first, a staggered vacation plan that would keep her team fully functional while members are out and, second, a new policy that would allow her reports (and possibly others) to tack vacation days on to the business trips they will take in the coming year.

Appreciate your counterpart’s situation. When you ask for something atypical, you can create problems for the person with whom you’re negotiating. He or she is under constraints and it’s important for you to understand those. Your proposals may violate precedent, they may cost too much, they may require an uncomfortable conversation with a more senior leader. Sometimes it helps to address these issues directly — indicating that you appreciate the good reasons for saying “no” to your request. Jennifer designs both of her proposals to addresss her boss’s concern about how her team will cover its workload. Tom might acknowledge that his request is difficult to grant given the financial straits his company is in. Just mentioning these issues can lead to more fruitful, collaborative problem-solving.

Be prepared for pushback. Because your counterpart does probably have at least one good reason to say “no,” you should expect pushback. But don’t let it put you on the defensive. Instead, use one of three approaches: question, correct, divert. When an HR director tells Marisa that the company’s policy on vacations is three weeks for someone at her level and that she’ll accrue more the longer she stays, she can ask, “Are there any circumstances under which you deviate from that for a person with my experience?” or “ Under what circumstances would you consider altering the policy given my situation?” When Tom’s boss tells him that he can’t allow extra time off because of financial constraints, he can correct the impression that an extra week would have any significant impact on the company’s profitability. When Jennifer’s manager worries that her request will open the floodgates — encouraging people to ask for extra holiday any time they work long hours — she can divert and focus on criteria they might create to prevent that from happening.

Vacation is often an underutilized negotiating point. But it shouldn’t be. Just consider how Marisa, Tom, and Jennifer’s stories end. Marisa secures a higher salary and one-month vacation, with delayed bonus. Tom takes an extra week vacation in the year he’s promoted with an agreement to consider a salary increase the following year. And Jennifer scores a few days off for each of her team members on a staggered schedule.

What Knowledge Workers Stand to Gain from Automation

It is by now an obvious statement that companies compete on the strengths of their knowledge workers – people who “think for a living” by applying convergent, divergent, and creative thinking skills. Yet, more than 50 years after Peter Drucker devised the term knowledge worker, it is quite disappointing to peer inside the operations of any large organization and see how little of their time knowledge workers actually spend on higher-order thinking tasks. Largely to blame is the approach their companies have taken in applying office technologies. Faced with the choice, as author Shoshana Zuboff put it, to either automate or informate, they have tended toward the former – transferring tasks from the hands of workers to machines, rather than endowing people with greater capacities and having them work symbiotically with technology.

One result is that workers must now spend substantial time dealing with systemantics – the quirks and shortcomings that are just as endemic to systems as their strengths. For example, it is a systemantic problem that the typical automated operations system (including Enterprise Resourcing Planning, Customer Relationship Management, e-commerce, and e-business solution systems) is unable to complete a whole process, end-to-end. For the technology to deliver value, knowledge workers must do pesky things like extract and move massive amounts of data from one system to another. Knowledge workers consistently tell us they want to be liberated from such highly-structured, routine, and dreary tasks to focus on more interesting work. Some are actually getting that wish, thanks to a new approach known as Robotic Process Automation (RPA).

When people first hear the term “Robotic Process Automation,” they might imagine shiny robots gliding around office buildings. In reality, this is just software that can be made to perform the kinds of administrative tasks that otherwise require stop-gap human handling – for example, transferring data from multiple input sources like email and spreadsheets to systems of record like ERP and CRM systems. Calling it robotic, however, emphasizes the utility of a machine that can stand in for a worker and handle disparate, discrete chores. (One “robot” equals one software license and, in general, one robot can perform structured tasks equivalent to two to five humans.). The workplace adoption of RPA differs from classic business process automation in two important respects:

The developer hoping to automate a task does not need to have programming skills. Business operations people who have process and subject matter expertise but no programming experience can, with only a few weeks of training, start automating processes with RPA tools. If you are familiar with Microsoft’s Visio product, you can envision RPA tools functioning in the same way, with users dragging, dropping, and linking icons that represent steps in a process. (One of us took the software training for Blue Prism, one of the leading RPA providers, and was able to automate a process in less than two hours.)

RPA does not disturb underlying computer systems. This is “lightweight IT,” in that the robots access other computer systems the way humans do—through the user interface with a logon ID and password. No underlying systems programming logic is touched. (For IT readers: RPA accesses systems of record through the presentation layer.)

Given this ease of use and lightweight operation, adoption of RPA can originate inside business operations, and typically does, rather than being brought to the business by the IT department. And thus (because RPA projects do not require expensive IT skills), the threshold of processes worth automating is substantially lowered. Even where a particular tedious task is not being performed by a very large number of people, RPA can economically delegate the task to robots.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

In one case study we saw UK mobile communications provider Telefónica O2 deploy more than 160 robots to process between 400,000 and 500,000 transactions each month, yielding a three-year return on investment of over 650%. More astounding, Telefónica O2 reached this scale by training only four people. Another case study subject, a large UK-based utility, deployed more than 300 robots that process three million transactions per quarter, yielding an annual return on investment of 200 percent. Here, two humans orchestrate 300 robots that perform the work of 600 people. In general, early adopters of RPA find that automation radically transforms operations, delivering much lower costs while improving service quality, increasing compliance (because everything the software does is logged), and decreasing delivery times.

This might sound like a recipe for headcount reduction, but in the cases we have studied, it hasn’t been. People who worry about job losses to automation tend to overlook the unprecedented data explosion businesses are experiencing, now accelerating out of knowledge workers’ control and demanding automation to deal with it. Indeed, most of the RPA adopters we have studied have gone so far as to promise their employees that automation would not result in layoffs. (To be sure, many have been able to avoid hiring new workers – and some companies have reduced their reliance on outsourcing to complete administrative tasks.)

Where such job assurances have been given, workers have not felt threatened by automation. They embrace the opportunity to take on more interesting work, and view the robots as teammates. For example, in our case study of Xchanging, a provider of IT, business, and procurement services, the knowledge workers named the robots and even invited them to office parties.

Our favorite example is the robot (technically, the set of robots) they named “Poppy” — because the system went live on Remembrance Day in the UK, when it is traditional to wear poppies. For the knowledge workers at Xchanging, Poppy took over the laborious task of processing the structured premiums that come in from London’s insurance brokers. She adds supporting documentation, checks for errors, kicks out exceptions, and adds validated information to the official market repository. Poppy hands over the exceptions to her human teammates for processing. They think of her as a “fresher”— the kind of newly-hired employee that has traditionally done the support work for the team — but an especially industrious one.

In another workgroup at Xchanging, a knowledge worker named her robot teammate “Henry”— but despite the male persona, she sees him as a kind of extension of herself. “He is programmed with 400 decisions, all from my brain,” she explained to us, “so he is part of my brain, and I’ve given him a bit of human character which works for me.”

For us, there is a big takeaway from the case research we have done. It indicates that, as cost barriers fall, workplaces will naturally gravitate toward teams of humans and robots working together to accomplish goals, each assigned the tasks for which they are ideally suited. RPA is one automation tool, but not the only one, that will help to bring about this future of operations. As cognitive intelligence tools like IBM’s Watson are adopted, those will be game changers, too. Combining these technologies, human knowledge workers might soon, in the midst of creative tasks, call on multi-tasking robotic coworkers to perform supporting work as needed — boosting their output even in novel processes with “robots-on-request.” In this way, contrary to today’s worst fears, robotics could facilitate the rise, not the demise, of the knowledge worker. Let’s hope the imaginations of their managers expand as rapidly as their automation toolkits.

Personalized Technology Will Upend the Doctor-Patient Relationship

In a few years, the idea of receiving medical treatment exclusively at a doctor’s office or hospital will seem quaint. Wearable technologies, implanted devices, and smartphone apps allow continuous monitoring and create a ubiquitous, 24/7, digitized picture of your health that can be accessed and analyzed in real-time, anywhere. Data gathering isn’t the only force moving treatment out of the doctor’s office; telemedicine, home diagnostics, and retail clinics increasingly treat patients where they live and work. In the next decade, these trends will create a veritable gold rush in patient data and consumer options.

With incremental revenue, cost savings, and customer loyalty all up for grabs, a range of players—from consumer product companies to digital and mobile technology firms—are already fiercely staking their claim. As with the original Gold Rush of the 1840s, we believe two principal business models will emerge: Goldminers, who dig deep in one major area, and Bartenders, who offer customized and convenient options to address routine needs.

The Goldminer strategy will typically involve vertically integrated players (large institutions like insurers, hospitals, and physicians’ groups) creating medical value by better managing the health of the heaviest users of healthcare: the 30% of patients with complex conditions that comprise 75% to 80% of all medical spending. By coordinating care more effectively and offering daily support—through mobile communication and remote monitoring—along with community outreach, these companies can help shift care to more timely, home-based, and less costly interventions.

There is clear potential in this approach, yet it is a logical, tech-enabled extension of the traditional approach to healthcare. Providers still make the bulk of the decisions, and patients dutifully follow instructions.

The Bartender strategy represents a much more dramatic transformation. In this approach, new entrant companies (often players from outside healthcare—retail, software, electronics, and apparel) focus on empowering and creating a better experience for consumers by providing detailed, personalized health information and advice. This approach is profoundly disruptive, in that it circumvents the doctor-patient relationship and gives people far greater choice and control over where they receive care, how, and from whom. As Eric Topol of Scripps Health put it, “The digitization of human beings will make a parody out of ‘doctor knows best.’”

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

For example, consider a woman with random heart palpitations. In the Goldminer approach, she would be enrolled in a preventive care program, the centerpiece of which could be an app for her phone that continually tracks cardiac activity, with the bulk of decisions centrally controlled through a clinical care team.

By contrast, a Bartender approach would be to sell the patient an ECG and lifestyle app for her smartphone and let her retain control over the data. The patient records her daily activity through the app’s intuitive interface and decides whether to send the data to her doctor, to a vendor’s experts, or to a computer for continuous monitoring and interpretation. The app also tracks lifestyle behaviors such as exercise, diet, sleep, and medications. As data accumulates, patterns start to emerge, such as a correlation between certain medications and the severity and frequency of her palpitations. The app can suggest a range of interventions, from text-alert reminders of her medication schedule to automatically notifying a designated contact in an emergency. Every choice represents a potential revenue stream that is up for grabs between incumbents and new players.

One could even imagine the OnStar of healthcare—a subscription service via an implanted device that can detect if a heart attack is imminent, alert the patient to take action, or even send a message to 911 to send an ambulance if necessary. Throughout, the patient retains control over decisions and is continuously empowered by data.

These scenarios are already in play today. Mobile health company Alivecor sells a device that tracks ECGs via smartphone and provides consumers options for sharing and interpreting the data with third-party vendors and doctors. Device and analytic firms such as WellDoc and BlueStar use mobile self-management programs to monitor blood sugar and offer coaching to diabetic patients. Sentrian feeds data from biohealth sensors into IBM’s artificial intelligence engine, Watson, to identify when an intervention may prevent a hospital admission. Apple’s iWatch and Health app opens enormous possibilities for further innovation in wellness through continuous monitoring, particularly given that it comes through a brand that consumers are already passionate about. Technological advances based on the Bartender model will also push the boundaries of healthcare into new retail frontiers. Walgreens, for example, has partnered with Theranos Technology, a company that can conduct lab tests with a pinprick sample, to expand the diagnostics available in its walk-in care locations.

Consumers who subscribe to such offerings will force traditional providers to demonstrate value in new ways. With patients now owning and interpreting their health data, they will enter every medical encounter armed with meaningful, personalized expertise (not just a few pages printed from the internet). They may even choose to crowdsource their diagnosis in a forum like CrowdMed. When expertise becomes tailored to the individual and broadly accessible, providers must add greater value through relationship-building and a deeper understanding of patient needs.

The new companies applying the bartender approach are by no means fringe players. They will fundamentally restructure the flow of money in healthcare—and create enormous medical value in the process. A forthcoming Strategy& study of profit pools in the future U.S. healthcare value chain found that applying the Bartender model could reduce healthcare spending by $400 billion a year by 2025. That is nearly three times the reduction we saw in a scenario in which Goldminers dominated.

The Goldminer approach represents progress. But it is incremental progress within the current healthcare model. Bartenders, by contrast, will accelerate the transformation of the industry by profoundly challenging the industry’s current “one-size-fits-all” standard of care and centralized clinical authority.

How Bots Took Over Twitter

For the past year, Twitter has been plagued by stories of its decline — stories that got fresh momentum with the company’s latest quarterly report and the exit of CEO Dick Costolo. In their explanations for why Twitter ain’t what it used to be, critics often cite the proliferation of spam accounts: robots that exist purely for the sake of padding out follower numbers and hijacking hashtags.

But the robots that are really ruining Twitter aren’t these wholly automated fakers. They’re the semi-automated fakers: us. Many of us have long used tools that allow us to expedite our social media posting; for example, I’ve used Buffer and HootSuite for several years to pace my tweets and keep my social media presence active. But now these companies not only offer the ability to schedule tweets; they also can suggest tweets for you to post.

Buffer offers “suggestions”; HootSuite, “suggested content.” Commun.it suggests the tweets that can thank and engage your most loyal followers. All these apps — and many more — are saving us from the problem of keeping up with social media by stripping away what was once the entire point of social media: actually using your own voice. The result is a Twitter that is authored by predictions and algorithms, rather than by humans.

For many users, that means Twitter offers a far less satisfying experience than it did just two or three years ago, when sharing a link often provoked follow-up comments and questions from people who’d actually read whatever you’d shared, or when tweeting a question could instantly elicit offers of help or insight. In on- and offline conversations with friends and colleagues, I frequently hear from folks like Michele Perras, a San Francisco-based design and product entrepreneur. “Twitter has become too much noise and not enough signal,” she says. “It used to be more like a hallway conversation, and now that’s harder to find that amongst the robotweeting and marketing.”

Twitter has always included a lot of one-way broadcasting alongside its micro conversations; indeed, as a number of my Twitter enthusiast friends pointed out, part of its value is in offering a quick way of finding and consuming a wide range of must-read or must-see content. But the rise of suggested content tools has shifted the balance between conversation and link-sharing, and in so doing has diminished the value of the links that get shared. For all the folks who are relying on suggested tweets, a tweeted link no longer reflects any curation or judgment on their part; it may well be something that was found for them rather than by them. Nor is it a sign that they’ve even read what they’re sharing: as The Verge reported in a story about Upworthy last year that there’s no consistent relationship between whether people shared a story on social media, and whether they’d actually read it.

I’m not immune to the temptations of suggested content myself. For much of the past year, I filled in the gaps in my tweeting by turning to Buffer’s “Daily,” a mobile app that suggests content for you to share, based on what you’ve previously posted. Launch the app on your phone, choose the network you want to post to, and Daily lets you page through a series of curated updates you can repost to your network of choice. Much like the dating app Tinder, Daily has made publishing or rejecting a tweet as easy as swiping right or left. Where it once took me an hour to queue up a week’s worth of tweets — by working my way through news stories and scheduling tweets based on the posts I found most interesting — I could now do it in 10 minutes.

Though, as in the Verge’s story, I cut the corner of actually reading the links Daily would suggest. That shortcut fueled a vicious circle at both a micro and macro level: As an individual user, the more I relied on Daily to drive my tweeting, the less often I checked in on Twitter to find posts I might want to reply to or reshare; that made me still more dependent on Daily to find material for me to tweet. And of course, the more people engage in that kind of behaviour, the more soulless and monotonous Twitter itself becomes.

Even though Daily was eroding my own experience with Twitter, the time it saved me made it irresistible – until I had an encounter with Buffer that made me see suggested content in a new light. Make that more than 500 encounters, actually: encounters with a steady stream of tweets linking to my July 2014 blog post for HBR,“The Right Way to Unplug When You’re on Vacation.”

That post had attracted a fair amount of Twitter activity when it first went live in July 2014, and enjoyed another surge when HBR promoted it again over the December holidays. Not long after, Buffer added the post to its own queue of suggested content, and soon I was getting anywhere from a half-dozen to a couple dozen mentions a day, all from Buffer’s one suggested tweet.

At first, I was delighted: Who doesn’t like getting more Twitter mentions? But as the months wore on, I grew tired of having a Twitter feed that was full of monotonous, cookie-cutter references to the same post. Admittedly, when I conducted a quick and dirty survey of a dozen people who’d shared my post via Buffer, seven of them said they’d read the post in its entirety before tweeting, and only one person admitted to tweeting it entirely unread. But the post was getting only a little more traffic than HBR would normally expect for an eight-month-old post, and more telling, none of the last 50 people who’d tweeted the post actually followed me on Twitter.

If they were “engaged” by Buffer’s suggestion, it was a brief engagement that added little value to the online conversation. Some of the people who had shared the post when it was first published had added their own reflections in tweets like “I still struggle with this” or “I read this article, just a little late” and “Can any business owner really do this!?!” But the people who were tweeting out Buffer’s suggested content all posted the same, uniform tweet: “The Right Way to Unplug When You’re on Vacation by @awsamuel.” Not only is this less interesting for me as an author, but it’s symptomatic of the way that suggested content makes link-sharing less valuable and more boring: Where Twitter users once got context and insight with their shared links, now they’re just getting the titles of posts — and they can’t even trust that the sharer has read that piece of content.

Finally, I decided to reclaim my Twitter mentions stream, and asked Buffer to unplug me from their list of suggested posts. They complied immediately, and their response pointed me toward a much happier tale of being on the receiving end of all those tweets.

But getting my post out of Buffer’s suggested content queue wasn’t enough to fully restore my passion for Twitter. I realized that to make my Twitter experience better, I had to be the kind of tweeter I wish to see in the world: someone who eschews the shortcut of suggested content apps and instead finds my own shareable content, enhancing it with my own reflections and commentary.

That doesn’t mean giving up on posting regularly, or even on using some shortcuts to make posting easier. But there’s a big difference between using these tools to make it easier to post the content you find, and using them to find it for you (maybe skipping the step of actually reading what you share). As I map out in Work Smarter with Social Media, you are better off using a news reader like feed.ly to find your own content — ideally based on searches you set up yourself, so you’re not tweeting the same stuff everybody else shares. Then you’ll not only share it but read it too — content that makes you more informed, with fresh information and perspectives that aren’t just borrowed from someone else’s crib sheet.

If we want Twitter — or any other online conversation — to be actually worthwhile, we have to be willing to put in at least that amount of effort. Otherwise we’ll be left with a social network where the only folks socializing are just robots, talking to other robots.

A Friend’s Support Can Make Women Better Entrepreneurs

The people we choose to surround ourselves with often matter a great deal to our success — especially when we are trying to thrive as entrepreneurs. That’s because spending time alongside other motivated and successful people can have positive effects on our own success. For instance, a 2014 study found that communication with motivated and successful nearby leaders can lead to higher aspirations and better investment behavior. But for women in the workplace—especially those in low-income developing countries—it can be harder to find other successful women to learn from and collaborate with, since social norms often restrict their mobility and opportunities to interact with one another.

In many developing countries, small family businesses, or “micro-enterprises,” run by women are very common. In India, for example, these home-based businesses are usually comprised of one or two family members and specialize in trades such as making incense sticks, vegetable vending, and construction work. There have been many efforts to increase business success among these low-income entrepreneurs through business training and counseling programs—but they have yielded mixed results.

It seems that simply training men and women in good business practices is not always sufficient to improve business outcomes. In light of this, researchers have searched for other factors that can impact the success of micro-enterprises. One such factor is peer interaction, but the evidence around peer effects at work is limited. A 2013 study found that having peers with prior entrepreneurial experience reduces the likelihood of future business failure. But this connection has yet to be studied extensively in the context of developing countries, or specifically with female entrepreneurs. If entrepreneurs do benefit from having friends at work, then the real culprit behind the low income and growth for female micro-enterprises could be the lack of established female micro-entrepreneurs in the business network.

We sought to explore this in a recent study. Working with Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) Bank, the largest women’s bank in India, we created a unique two-day business counseling program for women ages 18 to 50 who had actively saved or borrowed from the bank between December 2004 and January 2006. The program, led by bank staff who had been training similar groups for years, taught women basic financial literacy and business skills and showed them a film showcasing successful role models in their community. We also paired them with a trainer to help them set a medium-term financial goal and identify steps to achieve it. Approximately 57 training sessions were conducted from September 2006 to April 2007. Each two-day class had 10-12 participants, drawn largely from the pool of SEWA members who own a small business (e.g., vegetable vendors, tailors, etc.) or are engaged in home-based work (e.g., embroidery, rolling bidis, etc.).

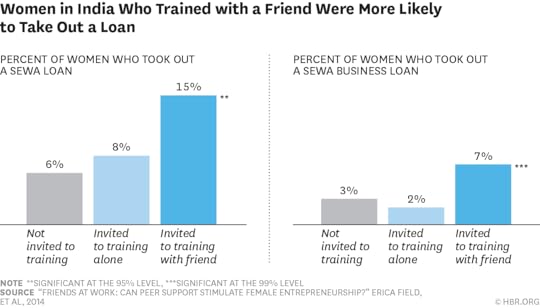

More than 400 women were randomly invited to attend the training program, while a group of more than 200 women served as the control group and were not. And unlike other business counseling programs, half of the women in our treatment group received invitations not just for themselves, but also for a female friend or family member of their choice. The friend would support the participant and receive training as well. Four months after the training, striking differences surfaced between the two groups of women who were invited.

Although both sets of women were more likely, on average, to take out loans than other clients of the bank who weren’t in the program, what they did with the loans turned out to differ quite a bit too. The women who were invited without a friend mostly used their loans for home repair largely unrelated to their businesses. Women who were asked to bring a friend along, on the other hand, were more likely to use their loans specifically for business purposes. You can see the levels in the graph below. Notice that invited alone and the control are never significantly different.

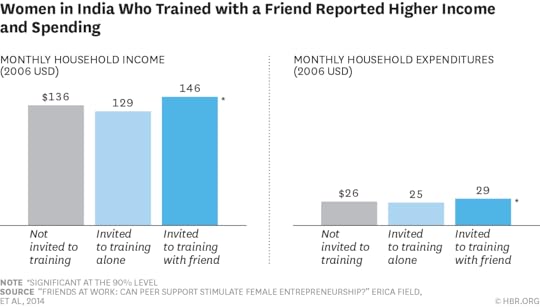

And not only were funds spent differently, but the women who brought friends also reported having a higher volume of business than those women trained alone—and they had specific plans to increase revenues.

Perhaps most strikingly, women who were invited to the training with a friend had significantly higher household income and consumption levels four months later, and were less likely to report their occupation as housewife.

These findings suggest that having a friend present during training can be an important factor in laying out and ultimately achieving business goals. And there are several possible reasons behind why this could be: Having a friend around may create a more supportive business environment, leading to greater business confidence. Alternatively, the presence of a peer could also create a sense of competition, which can lead to better business outcomes. And having a friend as a training partner may strengthen the social network that a woman relies on for support after the training is over. This support could include financial assistance, information, or even just ongoing encouragement.

However, evidence from our study seems to suggest a different explanation. Women invited to the sessions with a friend actually set very different goals—more ambitious goals—for themselves compared to women who attended alone. It appears that having a friend around actually changed the aspirations of women to be more business-oriented, not just their ability to meet the goals. For instance, women in the peer treatment group were more likely to state that their goal was to open a small shop, while the women trained alone were more likely to state a goal of saving money for their child’s education.

The improvement of business outcomes was especially salient for women in castes or religious groups that impose more restrictions on whether women can move about the community and interact with others unaccompanied. Socially restricted women who attended the training with a friend were 400% more likely to take out a loan than women in the control group and work nearly 14 more hours per week on average. This makes sense considering that heavily restricted women would ordinarily struggle to form strong professional networks with other female entrepreneurs and would likely not know about the success of female peers, given constraints on their mobility and interactions with others.

The key limitation of our study is that while the evidence on goal-setting is enticing, we cannot know exactly how peer effects operate. Our experiment was not designed to tease apart the specific channels through which a friend’s support boosts entrepreneurial outcomes, so more research is necessary to fully understand what’s behind our findings.

Nonetheless, these results show that peer encouragement really does have a positive influence on female business decisions and outcomes—which has wide-reaching implications. We should take the lack of peer interactions in business seriously if we want to close the entrepreneurial gender gap that exists in many developing countries. Strengthening peer networks can significantly raise women’s aspirations for themselves and their businesses.

Deciding to Fix or Kill a Problem Product

How can you tell if the product you are working on is likely to succeed or fail? In my experience working with leading tech and telecom clients on strategy and new product innovation, there are clear signals that a product is not ready for launch, should never be launched, is not actually a product at all, or, if it is launched, will most likely fail — signals that should be heeded if you want to avoid product train wrecks. If your project displays any of these signs, it’s time to radically change what you’re doing or pull the plug.

Situation One: It’s a Technology in Search of a Need

In 2002 I worked with a client at a large global electronics company. They were excited about bringing internet connectivity to home electronics such as TVs, refrigerators, washers, and driers. But they focused their energy on the technical issues — methods of connectivity, standards of information sharing — without having asked a fundamental question: What new things could each of our connected devices do that people would actually want them to do? The result was multiple product launches and more than 10 years of limited or no success in the connected home space.

Nest took a different approach. People have little interest in smart connected devices in and of themselves, but the Nest Thermostat does things people do care about: saving money, being comfortable, reducing energy waste. Instead of selling the concept of the “connected home,” Nest focused on specific problems their customers wanted to solve in addition to good technology. The result: Market success for the product and the company was purchased by Google for $3.2 billion in 2014.

Fix or kill? Kill: If you can’t point to the specific and glaring need you are solving for, something people care about and will pay to have solved, then kill the product and start over.

Situation Two: Poor Usability

Usability is the second major killer of new products and services, and the bar is getting ever higher for what makes a great user experience. People will compare your product against the best things they’ve experienced, not just competitive products in its category. If it has a screen, people will touch it and expect familiar swipe functionality. If it has search functionality, they’ll expect it to auto-fill the most likely results. When they take it out of the box, they will expect to just plug it in or turn it on and have it work.

But products often fall short of these high expectations. One of my clients launched a connected home product that required the user to interface through a browser on a computer even though customers expected to engage through a mobile app. Another client introduced a connected product that required the user to go through a long set up process, including setting a clock. Setting a clock? Isn’t this thing connected to the internet?

The idea here isn’t to pursue perfect, but rather to have a more expansive view about what your customers will perceive as the benchmark for similar products and to avoid usability mistakes that are easy to make — and to make sure non-experts have experienced it the way customers will.

If some of these usability shortcomings are obvious, then how do they get out the corporate door? The answer is usually that key decision-makers haven’t actually used the product. They’ve seen a visualization, listened to a PowerPoint presentation, watched a highly controlled demo. And the engineers and developers working on the product are too close to it or have a much higher tolerance for complexity than the customer will.

Fix or kill? Fix: Make sure people outside the design team have used the product; work tirelessly to remove barriers to set up and improve usability; often these weaknesses can be fixed, but only if they are caught before launch. When we do a product evaluation we score our client and competitor products against both “hard” and “soft” factors. Hard factors being the typical features, costs, and capabilities that our clients would look at themselves, and soft factors being things like installation, out of box experience, usability, aesthetics, brand value, etc.

Situation Three: It Does Not Have Good Strategic Fit

While it’s imperative to keep in mind the fundamental needs of the consumer, the needs of the company are important, too. I’ve seen many good products suffer delays, die the “death of a thousand cuts” or get dumped altogether — not because they didn’t have real purpose and potential, but because people in the organization were not clear on how the product aligned with the company’s goals.

In the tech space, there are dozens of startup companies and products — like Dropbox, WhatsApp, and Netflix — that are succeeding in the market even though larger, more established companies had the concepts in development earlier than they did. What happened? Corporate indecision and misalignment of strategic objectives let promising products fall by the wayside.

What is your company’s strategy? How does your product fit into it? Will it cannibalize other initiatives? If you don’t know the answer to these questions, then your project may be at risk.

Fix or kill? Usually kill: The fix is conceptually easy but hard in practice: clarify the role of your product in your organization’s strategy, link what you are doing to long-term value creation and growth, and get buy-in across the organization; if you can’t get those things, it’s time to kill your product. In spite of the project’s potential, your success is unlikely.

Situation Four: It’s an Idea, Not a Product

You have a grand vision of an emerging market opportunity, a hot trend, a breakthrough technical wave, that — at least in theory — your company is superbly positioned to capitalize on. This is the case, for example, with digital advertising. It seems that every major tech company has a plan for how to invade and dominate this space by leveraging their customer data or subscriber relationships.

But fantastic opportunities and relevant assets are not equivalent to viable new products. Until you map out exactly what you are creating, why it’s valuable, and who is going to pay you for it — you don’t even have a “concept,” let alone a product. In a way, this is the opposite of a technology in search of a need. You’ve identified a need, but you haven’t figured out how to solve the need with a tangible product offering.

It is fine to explore new market areas like this, but spending months or years without figuring out the details is dangerous and wasteful. This problem can be compounded when senior executives publicly announce these non-products in an “exciting new space,” creating more pressure on the project development team to deliver something (anything) before it is clear what exactly should be delivered.

Fix or kill? Kill: Set clear timelines, milestones, and criteria for product development in new market areas. If real products do not emerge according to plan, kill the project. This takes great effort. One client described the process as “Whac-A-Mole” — the same half-formed ideas keep popping back up even after you smack them down.

Situation Five: It’s Designed for Now, Not for the Future

The final major product development challenge is market timing. Most product teams or strategy groups go through a process of defining market requirements and scoping out the competitive landscape. This is necessary, but too often they focus on the market as it is today, rather than what it might be at the time they plan to launch the new product — months or years from now.

Product developers also evaluate specific features of their product-in-development against current offers in the market and conclude that theirs will have an advantage. In the meantime, the competition is managing their own innovation and coming up with similar or better improvements to their own products. The result: you are always a year or two behind the market.

No innovation remains innovative for long. In the mobile phone market, black and white displays gave way to color in a wave. Thin phones beat out fat phones. Flip phones (“feature phones”) were trumped by smartphones. In each case, the leader in the prior generation was left behind because product organizations underestimated the speed and magnitude of the market transitions.

In the automobile market, Tesla provides a counterexample. Although electric vehicles are too expensive for most people today, Tesla is betting on the long-term cost and performance improvements of the battery, IT, and electronics markets to improve competitiveness over time. Each year, the integrated software and hardware of electric vehicles (EVs) gain ground on traditional internal combustion engine vehicles, expanding the market opportunity for Tesla and other firms pursuing EVs.

Fix or kill? Fix: This is a process fix, a mindset fix. To win, your product must capitalize on changes in enabling technologies to lower costs or create new value. Revisit your market requirements and competitive assessment with an aggressively forward-looking lens, and you can dramatically improve your chances of success.

A final note: Killing a new product initiative is one of the toughest things to do in any organization, but, in my experience, the ability to kill a project that cannot succeed is one of the most valuable skills a product development team can have. Learning to recognize the signs, and developing ways to respond to them immediately, can save you hours — and possibly even years — of fruitless effort and wasted resources.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers