Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1280

June 24, 2015

Build STEM Skills, but Don’t Neglect the Humanities

Who doesn’t stand in awe of the advances that science and its STEM siblings (technology, engineering, and math) have created to better our world? But since the time of Aristotle, it has also been recognized that the hard sciences and the humanities must walk side by side in governing human action.

Aristotle praised “practical wisdom” (the ancient Greek word is phronesis) — the middle ground between scientific knowledge (in Greek, episteme) and what he referred to as the “cunning intelligence” (in Greek, metis) of politicians, military generals, and Machiavellian business leaders. In his Nicomachean Ethics, he rejected that scientific knowledge alone could determine the affairs of the human social world, which he recognized as too complex and unpredictable to govern with certainty. Likewise he saw that cunning was insufficient to shape a society filled with the “good life.” Aristotle insisted that practical wisdom was required to advance the human race, because it would take into account what he called “the common good,” doing what is right for the majority of people living together in society.

Aristotle’s philosophy is still sound today. But to the extent that we side with him, we must challenge our modern era’s overwhelming emphasis on the STEM disciplines as the keys to progress. Yes, we will continue to welcome advances in computerization, robotics, communications, nanotechnologies, medicine, space exploration, and more — but to ensure these are in service of the good life, we must also advance our thinking in the humanities: philosophy, social affairs, and the arts. It is not either/or, but both.

Instead of just STEM, we should perhaps be promoting STEMMA — raising a new generation that also has greater capacities for managing collective human endeavors and appreciating the arts. Management education – the new “M” in the acronym – has not always been infused with humanistic thinking, but it must become more so. Our goal must be to cultivate the thoughtful enterprise leaders of the future. Meanwhile, regarding the “A,” how could it be beneficial to the future to deemphasize the arts, which inform our knowledge of beauty and meaning in human affairs? All the brilliant discoveries of STEM will not solve the grand challenges of today’s world — ignorance, poverty, intolerance, and political conflict – without the practical wisdom of humanities-trained leaders.

Let me illustrate my point. Imagine, if you will, that the STEM experts of the world make astonishing progress in the next two decades in physics, bioengineering, digitalization, nanotechology, and medicine. Say the future arrives as foretold by physicist and TV star Michio Kaku in Visions: How Science will Revolutionize the 21st Century: Humans live to age 150, disease is eradicated, space travelers regularly go to the far reaches of our planetary system, alternate realities are visible with the naked eye, and information of any type is available faster than the beat of a hummingbird’s wing. It’s a world in which Moore’s Law — the prediction made in 1965 by Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel, that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit would keep doubling at regular intervals – has held true, and Ray Kurzweil’s Law of Accelerating Returns has been borne out. (Kurzweil predicts that the rate of scientific discovery will keep picking up, such that the amount of knowledge gained in the seven-year period of 2014-2021 will be equivalent to the entire previous century’s gains – and eventually, that a century’s worth of progress will happen within a month.)

Without doubt, the biggest feature on this future landscape will be the presence of artificial intelligence (AI). If you have not yet thought hard about the implications of this, I would refer you to Tim Urban’s insightful piece, “The AI Revolution: The Road to Superintelligence.” Synthesizing the predictions of AI experts, Urban speculates that by 2040, we will have moved from the artificial narrow intelligence (ANI) that cars and refrigerators now have, up to artificial general intelligence (AGI), in which computers are as smart as humans. And that is when things really take off. At that point, AI leaps unimaginably quickly into artificial superintelligence (ASI). (Thank you again, Law of Accelerating Returns.) Urban explains how this might happen literally within hours, in what he calls an Intelligence Explosion, and hints at the mind-bending implications: “Superintelligence of that magnitude is not something we can remotely grasp, any more than a bumblebee can wrap its head around Keynesian Economics. In our world, smart means a 130 IQ and stupid means an 85 IQ — we don’t have a word for an IQ of 12,952.”

We cannot take these predictions lightly, given the enormous leaps we are already witnessing each year in STEM fields. Many AI experts subscribe to Vernor Vinge’s 1993 prediction that we will reach the point of “singularity,” when technology’s intelligence exceeds our own and “the human era will end,” and accept Kurzweil’s predictions of accelerating technological progress.

And therefore, we cannot march boldly into the future without demanding rapid advancement, too, in the faculties required to preserve our human dignity in a world of ASI. Our capacities for ethical decision-making, compassion, and creativity must also grow, along with our intellectual capabilities to deepen our understanding of the human need for connection, accomplishment, and meaning. Humans are not robots and neurons are not digital switches. It is only through the humanities that we will be able to appreciate the answers that superintelligent computers will give us when we ask them the hard questions. It is only through the humanities that we will increasingly recognize and build on what we humans uniquely are. It is through STEM plus MA progress that we have the chance to become practically wise.

This post is part of a series leading up to the 7th Global Drucker Forum, in Vienna, Austria, of which HBR is a sponsor. To read more posts related to the theme of Claiming Our Humanity–Managing in the Digital Age, visit the Drucker Forum’s blog.

June 23, 2015

What Happened When Linkin Park Asked Harvard for Help with Its Business Model

Photo by Mark Fiore

How do musicians make money today? Album sales are down 14%, single downloads are down 11%, and only the streaming services are up, 28%. Technology has forced music artists to completely rethink the way they approach their businesses. We’ve all had to adapt.

The most successful artists in this new landscape have begun to look at new business models and new industries to strengthen their existing brands. They’re extending their brand into areas like technology, gaming, fashion, and lifestyle content — essentially becoming entertainment platforms.

Here at Machine Shop, the wholly owned innovation company of the alternative rock band Linkin Park, we identified the need to think differently years ago. Machine Shop was born in drummer Rob Bourdon’s living room in 1999 when the band was packing CDs and stickers into boxes to send to their very first fans, long before any of their music had hit the radio waves. The band was distributing its self-produced first album, having created buzz for it in online forums and chat rooms and building a community there (this was several years before Facebook and Twitter transformed social media). Jessica Sklar, then the band’s intern and now Machine Shop’s Chief Strategy Officer, evolved the online discussions into in-person meet-ups and events at concerts, developing what came to be known as the “Linkin Park Underground.” This fan club gave the band a deep understanding of the importance of direct relationships. Today, Linkin Park is one of the biggest bands on Facebook, with over 63 million fans across the globe, and is particularly popular in Japan, India, Brazil, China, and Germany (and the U.S., of course).

For more than a decade, Linkin Park and Machine Shop enjoyed success and continued to innovate. The band put out new albums regularly and experimented in video games, art, and video content, among other things. Machine Shop began to offer its grassroots marketing services to other bands, film studios, TV networks, and brands. But by 2013, Linkin Park and Machine Shop had to address the fact that digital music (first downloads and then streaming) had changed the business dramatically. So they began to prepare for their next decade.

A New Model

I met the band at this inflection point. Rather than incremental change, they wanted a true paradigm shift, so the group tapped me as Machine Shop’s Executive Vice President. I had experience in marketing, business, and finance — all of it outside the traditional music business. When I looked at the global reach of Linkin Park, and the potential business opportunities outside the narrow category of music, I could see plenty of “blue ocean.”

We restructured Machine Shop to focus on innovation through non-traditional business partnerships and creative design thinking. Over the course of a year, we built strong case studies in fashion, design, and technology. Once this groundwork was laid, we realized that the traditional music management model would have to evolve to support these innovation activities. Most management companies consist of music industry professionals and digital departments that support music marketing activities — but what we were trying to do just didn’t exist within that framework.

So we parted ways with our outside management agency in late 2014 and we brought all core business operations in-house. As co-lead vocalist and founder Mike Shinoda puts it, “Our goal was to build an internal team of diverse talent to support the non-traditional endeavors the band plans to pursue in the coming years.” The move allowed us to venture freely into diversified revenue models to complement our music sales. Our business now operates like a tech startup, with less hierarchy and far more agility.

Photo by Lorenzo Errico

Enter Harvard Business School

To help think through this critical strategic restructuring, we turned to a leading expert on marketing strategy for media and entertainment firms, Harvard Business School Professor Anita Elberse. In collaboration with Elberse and her students Blaire Lomasky, Neil Wusu, and Jingping Zhang, we conducted a semester-long independent study on the business of Linkin Park.

During Phase I of the study, we did extensive research into the businesses of music industry innovators: the merchandise strategies of Tyler, The Creator, the joint ventures of Jay Z, and the tech incubation and investing of actor Jared Leto. We unpacked the strength of Trent Reznor’s creative partnership with Beats Music, the diversification of Pharrell’s content platform i am Other, and the positioning of Beyonce’s management company, Parkwood Entertainent.

We also looked beyond music for insights. We examined innovative brands that have build strong affinities and ecosystems around core products. The evolution of VICE’s media platform from print to video content across fashion, tech, design, and ultimate fighting. The expansion of Red Bull’s brand affiliation across multiple sports, and its integration into the worlds of racing and extreme sports. We also looked at niche creative studios like Staple Design and Surface To Air that have gained currency among the Fortune 500.

In this phase we learned that we need to:

Build a differentiated brand ecosystem that partners want to buy into

Use creative content to communicate our brand’s point-of-view

Ensure that our brand ethos is clear and that it’s reflected in every brand touchpoint

Diversify revenue streams across multiple business verticals to mitigate financial risk and extend our brand message

Partner with a broader community or network of global influencers to remain tapped into bleeding-edge cultural trends

In Phase II, we dissected the Linkin Park ecosystem and architected a framework to execute our new long-term vision. We restructured Machine Shop, moving it from a brand agency model to a multi-pronged innovation model based on four verticals: video content, global brand partnerships, merchandise, and venture capital.

Beyond Music

Having completed the study in early May of this year, we’ve already started to implement key HBS strategies. In mid-May, we launched Machine Shop Ventures, our venture capital firm, which will focus on investing in early-to-growth-stage consumer-focused companies that align with the band’s ethos of connecting people and innovation through tech and design. We want to share with our portfolio companies what we know about maintaining a brand in the cultural zeitgeist; we look forward to learning from them about internal company culture, vision, and creating new business. So far we’ve invested in Lyft, Shyp, Robinhood, and Blue Bottle Coffee to name a few.

We’ve also ramped up our brand expansion and merchandise business with the recent hire of Lisa Kidd, who was a driving force in the business development of Gwen Stefani’s fashion lines L.A.M.B. and Harajuku Lovers. To help with strategic thinking, we hired Michael Seversky, who was responsible for strategy, corporate development, and market insights at Beats by Dre.

To be clear, we are still in the music business, but creating and selling music now plays more of a supporting role in our overall business mix. As we get ready to headline a five-city stadium tour of China this summer, we are also planning to meet with technology companies, consumer brands, and venture capital firms to discuss opportunities for partnership. Of course we’ll play the shows and meet with fans, as we’ve always done. But along with continuing to make great music, today’s Linkin Park is now better positioned to operate in the ever-evolving cultural and business landscape.

How Industrial Systems Are Turning into Digital Services

To some, ball bearings are boring, even though these small steel spheres are what keep everything from factory machines and wind turbines as well as cars, trucks, planes, and trains moving smoothly and safely. But to Sweden-based SKF Group — the leading company in the $76 billion global market for ball bearing systems — these objects are heroic, destined to become the “brains of rotating machinery” by transmitting data to boost performance, reduce downtime, and prevent accidents.

Yet even though SKF has a century-long track record of keeping the wheels of industry turning, this new vision of bearings with brains by no means assures that SKF will prosper in the changeover in technology represented by the internet of things, in which every conceivable object can become a node on the net.

So far, much of the attention around smart, connected products has been around consumer-facing goods like watches and thermostats. Industrial companies have tended to be among the last to create digital strategies that harness the new opportunities arising from the proliferation of smart products. That lag poses dangers. Tech titans such as Google and Amazon are working to connect more and more types of objects to the web by offering mobile interfaces for managing just about anything. If someone else designs the apps and software that allow customers to monitor machines, the ripple effects across value chains could force industrial giants into the role of being mere suppliers of commodities.

Building an industrial internet strategy. In this respect, creating an industrial internet of things is an even more urgent endeavor, because industrial systems represent huge capital expenditures, have longer lifecycles, and are placed in mission-critical and often hostile environments that can cause costly and dangerous systems failures. “In some offshore wind applications, changing the main bearing on a turbine is so expensive that it undermines the business case for building the turbine in the first place,” said Filippo Zingariello, director of global strategic development at SKF.

Such challenges, he says, require industrial companies to take a fresh approach to strategy. After all, the technology now enables a different kind of relationship with customers.

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

Recognizing this, SKF two years ago announced SKF Insight, a way to turn its industrial products into digital services. The first step involved hardware — installing tiny sensors into bearings that are powered by the kinetic motion of the machines themselves. Those systems can now transmit real-time data about the performance of industrial machines as well as the components of energy and transportation systems. Railway operators and wind farm owners were among the first to deploy the concept.

Turns out, data from all of these little things can make a big difference. SKF now provides 45 different iPad apps so managers can monitor the maintenance, speed, and reliability of up to 8,000 kinds of smart objects. This has led to new business models, putting SKF squarely in a position to provide “knowledge as a service” (KaaS), as more than a half million machines are already connected to the SKF Cloud.

The race toward new industrial business models. SKF is just one of many industrial companies adopting new business models based around the increased interactivity between smart objects. Companies like John Deere have launched new business models for selling digital subscription services to farmers and operators of construction and mining equipment.

By changing the basis of competition in old-line industries, smart, connected products are precipitating three strategic shifts that we believe will eventually transform virtually all companies that manufacture things:

From selling equipment to selling outcomes. This is analogous to the shift to outcome-based business models taking place in other industries such as healthcare. You don’t buy a piece of equipment; you buy what that equipment can do for you. Bristol Siddeley (later purchased by Rolls Royce) originated the “power by the hour” model of selling aircraft engine uptime more than 20 years ago. Now, the industrial internet has enabled companies like GE, Cummins and Caterpillar to apply the idea across multiple dimensions. For instance, Caterpillar’s Cat Connect solutions emphasize machine uptime, fuel efficiency, and increased safety.

Designing solutions that transcend the notion of products and services: Instead of thinking of the world in terms of products or services, industrial companies need to create hybrid solutions. The provider goes in with a mindset of creating an integrated offering building on the value and decision making enabled through data analytics. For instance, GE’s Predix cloud platform is all about the performance metrics of water plants, gas turbine plants and other industrial systems, rather than the features of all the hardware and software that makes it happen.

From value chains to value networks: New stakeholders and types of relationships are causing companies to think beyond current industry value chains to imagine new industrial ecosystems. This requires industrial companies to reevaluate the sustainability of their current position, the viability of expanding into new roles, and the set of organizations they see as “competitors.” One could argue, for instance, that ExxonMobil is now competing against Google in telematics. And while Daimler and Volvo want to create their own telematics systems, commercial vehicle fleet owners want integration across brands, challenging the notion of proprietary systems. Companies that want to remain focused on their core products need to watch out for organizations that are capturing customer mindshare through such new services.

These three big shifts are now playing out in nearly every industrial market, regardless of whether it is B2C or B2B, high- or low-asset intensity. The scope and speed vary, but the shifts are more fundamental.

The Limits of 3D Printing

Contrary to what some say, 3D printing is not going to revolutionize the manufacturing sector, rendering traditional factories obsolete. The simple fact of the matter is the economics of 3D printing now and for the foreseeable future make it an unfeasible way to produce the vast majority of parts manufactured today. So instead of looking at it as a substitute for existing manufacturing, we should look to new areas where it can exploit its unique capabilities to complement traditional manufacturing processes.

Additive manufacturing, or “3D printing” as it is commonly known, has understandably captured the popular imagination: New materials that can be “printed” are announced virtually every day, and the most recent generation of printers can even print several materials at the same time, opening up new opportunities. Exciting applications have already been demonstrated across all sectors — from aerospace and medical applications to biotechnology and food production.

Some predict that a day is coming when we’ll be able to make any part at the push of a button at a local printer, which might even render the global supply lines that dominate today’s world of manufacturing a thing of the past. Unfortunately, this vision does not stack up to economic reality. Early findings from a research project being conducted by the Additive Manufacturing and 3D Printing Research Group at the University of Nottingham and Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford show that there are both significant scale and learning effects inherent in the 3D printing process. (The project, in which I am a principal investigator, is focusing on industrial selective laser sintering (or more accurately, melting) processes and not fused deposition modelling or stereolithography processes that are more suited to rapid prototyping and home applications.)

Furthermore, the pre- and post-printing cost amount to a significant proportion of total cost per printed part. So even when the cost for printers materials come down, the labor-cost penalty will remain.

3D printing simply works best in areas where customization is key — from printing hearing aids and dental implants to printing a miniature of the happy couple for their wedding cake. Using a combination of 3D scanning and printing, implants can be customized to specific anatomic circumstances in a way that was simply not feasible beforehand. However, we also know that 99% of all manufactured parts are standard and do not require customization. In these cases, 3D printing has to compete with scale-driven manufacturing processes and rather efficient logistics operations. A good example is the wrench that NASA printed on the International Space Station last year. The cost of shipping it to the space station would have been at least $400 (assuming the unpackaged weight of 18 grams per wrench and using the most recent cost data given by NASA for transporting goods into lower-earth orbit); in comparison, shipping it from China to the United States would only cost $0.002 per unit. Thus, while it makes a lot of sense to print the wrench on the space station, printing it for local consumption in the United States wouldn’t.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

The simple fact is that when customization isn’t important, 3D printing is not competitive. For one, printing costs per part are highly sensitive to the utilization of the “build room,” the three-dimensional area inside the 3D printer where the laser fuses the metal or plastic powder. Therefore, contract manufacturers that perform 3D printing such as Shapeways generally wait to fill a batch that uses the entire build room. Printing just one part raises unit cost considerably; so economies of scale do matter. Interestingly, the economic case for the most-cited standard part in 3D volume production today, the GE fuel nozzle for the CFM LEAP engine, is it is lighter and more fuel efficient, not a lower manufacturing cost per se.

A second point often overlooked is that the labor cost that remains. Counter to common perception, 3D printing does not happen “at the touch of a button”; it involves considerable pre- and post-processing, which incur non-trivial labor costs. The starting point for any 3D printing process is a 3D file that can be “printed.” Just having an electronic CAD drawing is not sufficient; currently, there is no way to automatically convert the CAD drawing into a 3D file.

Creating printable files involves two steps: creating a three-dimensional volume model that can be printed, and “slicing” that volume model in the best possible way to avoid material wastage and prevent printing errors. Both steps require tacit knowledge. Following the printing, the parts produced have to be recovered, cleaned, washed (or sanded and polished, in the case of metal prints), and inspected. This, in turn, means that using 3D printing for the aftermarket services — an application where it makes a lot of sense — requires making a significant upfront investment in generating the printable files of the spare parts that would likely be needed. This investment would have to outweigh the cost of keeping a lifetime supply of spare parts in inventory, which is a tough call for small bolts, brackets, and connectors that make up the bulk of aftermarket demand.

So while I, like many others, have fallen in love with the notion of the “ultimate lean supply chain” of having 3D printers at every other corner table to print single parts just in time where they are needed, I am afraid that this vision does not stack up against reality. 3D printing technology undoubtedly has great potential. However, it is unlikely to replace traditional manufacturing. Instead, we should see it as a complement, a new tool in the box, and exploit its unique capabilities — both in making existing products better as well as being able to manufacture entirely new ones that we previously could not make.

The 6 Most Common Innovation Mistakes Companies Make

The problem was clear. The executive team of a consumer healthcare company had concluded that the rise of new competitors meant the company needed to up its innovation game. The company had spent the past two decades focused on implementing Six Sigma processes across the enterprise and it was primed to execute on the best and smartest ideas.

We advised them that solving the problem required a carefully orchestrated set of interventions where we would “fight systems with systems,” making sure we linked a coherent innovation strategy to robust innovation processes, enabling structures, and work to make the underlying culture more supportive of behaviors and mindsets that drive successful innovation.

They chose … spandex.

A creativity consultant said to signal that it was a new era in the organization, all of the top executives should dress up as innovation superheroes. And that was it. No ring-fenced resources to pursue innovation. No tools or training. No special incentives. No definition of specific areas where the company should focus its energy.

The only piece of good news for the executive team is the “intervention” (which failed to have any impact, of course) occurred before smartphones were ubiquitous enough to capture video footage. (If this sounds familiar to some of you it is because we mentioned it to a BusinessWeek reporter in 2007, and IBM created a series of commercials with “innovation man” in them). We have nothing against spandex, and believe fun and play have a big role to play in a culture of innovation. But the real answer is surely more complex.

Because innovation is a system-level problem, a point solution – trying to drive widespread change by doing a single thing – is wholly ineffective. It is equivalent to attempting to turnaround a failing school plagued by disinterested students, overwhelmed teachers, and crumbling infrastructure by painting the walls blue. Soothing, perhaps, but unlikely to have any real impact.

We have seen far too many first hand examples of the equivalent of blue paint on a decrepit school wall. Rather, leaders hoping to boost their ability to drive growth through innovation need to simultaneously direct it strategically, pursue it rigorously, resource it intensively, monitor it methodically, and nurture it carefully.

This is clearly not easy stuff. Many of the most common missteps we see companies make would fit nicely in Steve Kerr’s management classic, “The folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B.” Here are the six most common mistakes we see:

Asking employees to generate ideas without creating mechanisms to do something with them. Executives often get fooled by inspiring stories of engineers at companies like 3M or Google coming up with germs of ideas in the 15-20% of their time they allocate to side projects. If your organization does indeed have mechanisms to take idea fragments, process them, and turn them into fully fleshed out innovations, by all means open up the idea spigot. Otherwise, all you create is a long list of ideas that never go anywhere, and substantial organizational cynicism. This doesn’t necessarily mean setting up a department, but at the very least develop a set of criteria by which to judge ideas and have suggestions for how the best ideas can be acted on.

Pushing for answers without defining problems worth solving. We define innovation as something different that creates value. You only create value if you solve a problem that matters. Executives often think that the best way to spur innovation is to remove constraints, to let hundreds or thousands of flowers bloom. Overly fragmented efforts result in nothing more than a lot of undernourished flowers. Constraints and creativity are surprisingly close friends. Problems can range from entering new markets to addressing everyday concerns such as low employee engagement. Whatever they are, the more specific, the better.

Urging risk-taking while punishing commercial failure. “If I find 10,000 ways something won’t work, I haven’t failed,” Edison once said. “I am not discouraged, because every wrong attempt discarded is often a step forward.” Indeed, the academic literature suggests that almost every commercial success had a failure somewhere in its lineage. But inside most companies, working on something that “fails” commercially carries significant stigma, if not outright career risk. It’s no surprise that people play it safe! That’s not to say that companies should encourage failure. When people do something stupid, or they are sloppy, or they screw up something that has dramatic repercussions on the business, they should absolutely be held accountable (can you imagine a heart surgeon talking proudly about the patients he or she killed?). The trick is simply recognizing that in the early stages of innovation what at first appears to be failure is anything but.

Expecting experiments without providing access to a well-stocked laboratory. It is increasingly well-understood that innovation success traces back to disciplined experimentation. Leaders transfixed with The Lean Startup or related books often urge their teams to develop minimum viable products or find other ways to rapidly prototype ideas. Indeed, finding smart ways to test is critical to innovation success, and this discipline goes well beyond prototypes. Consider what allowed the Wright brothers to successfully create a machine that allowed humans to fly. While most would-be aviators spent years building prototypes of their ideas, and then risked life and limb testing them, the Wright brothers flew kites and built wind tunnels. If your innovators don’t have the materials to build kites, or the space to fly them – or if they need to get 12 approvals to do so – don’t expect to see much experimentation.

Pleading for breakthrough impact without allocating A-team resources. Far too many companies create what you might call Potemkin portfolios. Just like the Russian prince Grigory Potemkin impressed Catherine the Great with villages that were nothing more than facades, companies build beautiful ideas on paper without considering the resources to turn them into reality. Innovation is hard work. The vast majority of startup companies fail, and that’s with tireless dedication from a team that has nothing to lose. If you don’t dedicate the right resources to your best ideas, you are consigning them to failure.

Demanding disruptive ideas, without ring-fencing resources for them. The essence of Clayton Christensen’s famous Innovator’s Dilemma is that companies privilege investments to sustain today’s business over those that have the potential to create tomorrow’s business. Along some dimensions, this is quite rational. After all, a dollar invested in the existing business produces a measurable, near-term return, whereas a dollar invested in a non-existent business promises ethereal returns at a difficult-to-pin down future date. Of course, over the long-run that disruptive investment might be a better proposition, but if the company hasn’t set aside resources specifically to drive disruption, the short-term will always win.

There is obviously a lot of value in pushing for more ideas, encouraging experimentation, and building breakthroughs. But take the time to think about the logical connection points inside your organization. Thinking at a system level will help to maximize your chances of driving impact. And minimizes the chances of being forced to wear spandex.

75% of Cross-Functional Teams Are Dysfunctional

When I was in the midst of researching what caused cross-functional teams to succeed — and finding that many of them failed — I discovered a deeply dysfunctional development project in a huge multinational IT company. The company had invested $100 million in the project, which involved three divisions. Most of the team, and even some executives, knew the project was a dead-end two years before the company finally pulled the plug. As one middle manager told me, “No one was willing to go to management and say, ‘Let’s redeploy everyone, including myself, and do something else because this project isn’t working.'”

This is just one example of the dysfunction that exists in cross-functional teams. In a detailed study of 95 teams in 25 leading corporations, chosen by an independent panel of academics and experts, I found that nearly 75% of cross-functional teams are dysfunctional. They fail on at least three of five criteria: 1.) meeting a planned budget; 2.) staying on schedule; 3.) adhering to specifications; 4.) meeting customer expectations; and/or 5.) maintaining alignment with the company’s corporate goals.

Cross-functional teams often fail because the organization lacks a systemic approach. Teams are hurt by unclear governance, by a lack of accountability, by goals that lack specificity, and by organizations’ failure to prioritize the success of cross-functional projects.

I studied cross-functional teams in industries including communications, software, pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, agricultural, chemical, manufacturers, retail, utility, consulting, internet software, government, insurance, and banking. We found a strong correlation between the minority of successful projects and their oversight by a high-level team that was itself cross-functional. A few successful projects didn’t have cross-functional oversight — but we found in those cases that they benefitted from support by a single high-level executive champion. Projects that had strong governance support — either by a higher-level cross-functional or by a single high-level executive champion — had a 76% success rate, according to our research. Those with moderate governance support had a 19% success rate.

Our research showed that the reason why most cross-functional teams fail is because siloes tend to perpetuate themselves: for example, engineers don’t work well with designers, and so on. The solution is to establish a “Portfolio Governance Team (PGT),” where high-level leaders make complex decisions on the various projects in their portfolio together. As they learn to work as a team, that attitude perpetuates itself in the teams under their purview.

You and Your Team

Leading Teams

Boost your group’s performance.

In the mid-2000s, for example, Cisco created a cross-functional team, including representatives from marketing, software engineering, manufacturing, quality assurance, and customer service, to heighten security for router lines. The team had a three-layer structure. About 100 people could attend the meetings, but there was a core group of 20 that communicated back to their functions. And, there was a small governance team at the top, made up of two vice presidents, the company’s chief development officer and the leader of the core team of 20 people.

This implementation of cross-functional governance worked. Cisco is now the number one router security vendor, with business growing at about 80%

per year for 5 year followings its introduction, based on a case study that I wrote.

Through our research, we’ve identified some golden rules of governance for PGTs:

1. Every project should have an end-to-end accountable leader. At large companies, where the hierarchy can be multi-layered, cross-functional teams can benefit from a mirroring structure. For example, if the PGT includes vice presidents of engineering, design, marketing and product, a project team could include managers and directors from those functions. But there should be one end-to-end accountable leader overseeing each function, and one end-to-end accountable leader overseeing it all.

However, one of the common breakdowns in cross-functional teams is people missing meetings. That’s why the personal accountable leader for each function also needs to appoint and empower a decision-making substitute. At IBM Global Services, for instance, there are occasions when mid-level managers step in with the authority to make decisions. At IBM, mid-level managers also serve as the first line of defense for cross-functional escalation issues.

2. Every project should have clearly established goals, resources, and deadlines. Before the beginning of any project, there should be an approved budget, and a charter defining priorities, desired outcomes, and timeframes. Establishing those early on is one of the key roles of the PGT.

3. Teams should have the project’s success as their main objective. Different functions may have their own priorities, and sometimes those conflict with the goals of the project. That’s why it’s crucial to include the success — or failure — of cross-functional projects in compensation and performance reviews of the people who work on or lead teams.

4. Every project should be constantly re-evaluated. PGTs should keep a list of projects and priorities and routinely cut those that aren’t working or that don’t align with business goals. In fact, one of the key roles of the PGT is to follow William Faulker’s advice to kill your darlings. Winnow constantly. Rapidly changing market conditions and customer demands force all companies to recalibrate their high-level corporate strategy. A PGT that is not routinely canceling some projects simply isn’t doing its job.

Cross-functional teams have become ubiquitous because companies need to speed innovations to market. The teams are like arteries, connecting parts of the body, enabling the whole organism to renew itself. That’s why it’s so important for leaders to pay attention to the way cross-functional teams are set up and how well they work: when they don’t function, the organization’s arteries harden. When they do, goals are met and the organization is ultimately more successful.

June 22, 2015

Rejecting Ideas Doesn’t Have to Cause Resentment

When I worked on Wall Street, my husband was doing postgraduate work at Memorial Sloan-Kettering in molecular biology. His research involved growing cells in beautiful pink-colored media. But the cell culture never stayed pink for long. Within three or four days the media would change to a dingy light brown. As the cells used nutrients, they produced byproducts, some of which were inhibitory to growth, and even toxic.

Much of how I view sustaining an innovative business culture comes from observing my husband maintain those cell cultures. Growing and maintaining a culture is an active process, which utilizes resources and generates byproducts. The dirty little secret of innovative cultures is that some byproducts are inhibitory to growth—and any organization that is not prepared to handle these toxins quickly puts itself at risk of contamination and failure.

Most innovative companies have an impressive ability to generate lots of ideas. Attached to each idea is someone’s dream. But not every idea can be pursued, which can make people grow angry, jealous, or bitter. If left unattended, these negative byproducts can become toxic, killing off projects and discouraging others.

Companies can avoid bitterness by making the message clear: no to your idea, yes to you. Consider the experience of Peter Eder-Buys, an IT executive at W.L. Gore & Assoc., a manufacturing company best known for its breathable fabric Gore-Tex. He and several other employees had presented ideas for the restructuring of the controller’s function and the calculation of transfer prices within the company. His idea failed to garner sufficient votes. Upset by his loss, his wound could have festered. But because his colleagues solicited his feedback and worked on getting a consensus, he didn’t become resentful. Eder-Buys told me, “Even though my ideas were not adopted, I was taken seriously and treated equally.” In time, he became one of the project’s biggest proponents.

Even when you do your best to be encouraging, rejection can stick. One small U.S. town government is facing intractable gridlock because one town commissioner’s idea met some resistance. In order to ease the town’s budgetary strain, one commissioner suggested charging residents a minimum fee for using the town’s recycling service. His colleague who had championed the recycling initiative turned vitriolic. He berated those in favor of the recycling fee–and got in the way of their proposals. And the mayor was too burned out to call out his bad behavior.

For organizations dealing with this kind of toxic or vengeful behavior, there are really only two options for preserving your innovative culture: reformation or termination. If you envision that the resentful party can still be a positive contributor, point out the unacceptable behavior while reaffirming your commitment to that individual. If the individual is unable or unwilling to reform, then they have to be removed. No scientist would ever endanger the outcome of an experiment by allowing toxins to build up in their cell culture, nor should any organization, manager, or mayor, tolerate toxic behavior spoiling the positive effects of an innovative culture.

One company that has found a unique way of dealing with toxic behavior is Riot Games, the maker of League of Legends. As Riot enjoyed an influx of new, inexperienced players, established players who considered themselves experts were subjecting newcomers to derogatory and disparaging comments. The negative behavior spread, threatening the company’s goal of creating a fun, collegial gaming environment and affecting the bottom line. Players who were subjected to abusive behavior were 320% more likely to quit. To counteract this trend, Riot started temporarily banning players for inappropriate or abusive behavior. The bans have gone a long ways toward removing the toxic behavior. Moreover, Riot has found that if you tell the players why they are being banned, half of them reform—and if you can show them evidence, that number jumps to 70%.

Giving a “timeout” to employees who are dismissive or actively haze new or more junior people is not always feasible, but calling out bad behavior is. Jeffery Lin, the Lead Game Designer of Social Systems at Riot is quoted as saying, “When a society (managers, employees and clients) is silent, deviant behaviors emerge, and they can become the norm.” Sometimes we turn a blind eye to this behavior because the bullies have standing or we just don’t want to deal with the upheaval and consequences of reprimanding the offender. But the danger of toxic behavior destroying what you have built is real and must be addressed.

My biologist husband found that to keep his cell cultures clean, healthy, and growing, he had to wash away inhibitory byproducts, re-plate the cells into a fresh medium, and at times, actively add antibiotics to remove a virulent contamination. The same applies to the unpleasant byproducts of a growing innovative business culture: management must be vigilant in keeping its cultural petri dish clean.

This article was co-authored with Roger Johnson, who holds a PhD in microbiology from Columbia University, and is a former assistant professor at UMass Medical School.

Is Programmatic Advertising the Future of Marketing?

Nicholas Blechman

It’s been 21 years since the first banner ad appeared on the web. It ran on a site called HotWired.com, the original website of Wired Magazine, and it asked, “Have you ever clicked your mouse right HERE?” An arrow pointed to an ominous-sounding prediction, which was spelled out in all caps, and read: “YOU WILL.” It was part of a campaign that aimed to visualize the digital future brought to you by AT&T. The vignettes were prescient in just about every instance except for a much-parodied TV spot that asked, “Have you ever sent a fax from the beach? YOU WILL.”

Who knew that it was the dawn of a new era not just for advertising, but for all of marketing? In the ensuing years, the technology ecosystem enabling the new ad medium would steadily unfold, while digital devices proliferated and network connectivity became ubiquitous. Now, many ads are served up by software systems targeting any digital device—from your smartphone and TV today, to the dashboard of your car and the thermostat in your home tomorrow. Soon, every display will be an addressable medium—that is, each will be individually targetable by device and, in many cases, down to a specific user; and interactive displays will not only deliver ad messages but also track consumer response. The result is a new era of marketing accountability, in which advertising “budgets” will have turned into marketing “investments.” This sea change in mindset will transform marketing forever.

How did we get here? Back for a moment to that first banner ad:

At the time, online advertising hardly represented a radical departure from Madison Avenue’s traditional practices. After all, the shift from print to electronic media had already taken hold, as advertising extended from newspapers and magazines to radio and television. The early buying and selling of online ads was not so different from what had come before. The same white tablecloth lunches served to negotiate deals, and the resulting insertion orders still, more often than not, were sent via fax. Yes, industry pioneers like Doubleclick were building technology systems to manage online ad serving, but the change was a matter of degree, not of kind.

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

It’s only recently that a true revolution in advertising has become evident. Fueled by the rise of ad-tech, or advertising technology, the buying and selling of digital advertising is evolving at a mind-bending pace.

The shift to advertising automation is quickly becoming an imperative. In 1977, advertisers vied for space (or time) from only a few hundred “publishers” (Web-speak for any digital media vehicle that delivers content). By 2012 the number of publishers, thanks to online media, had ballooned into the millions.

For advertisers, publisher proliferation signaled both good news and bad. On the positive side, brands now had an incredible array of options to reach precisely targeted sets of customers, which increased advertising efficacy. On the negative side, having millions of publishers implied extraordinary complexity and demanded Herculean administrative effort, which, in the absence of new methods, would dramatically decrease advertising efficiency.

The result? It’s become hard to do business in the same old ways: try negotiating over lunch with millions of publishers or sending insertion orders to thousands of them using a fax machine. Advertising automation is the inevitable solution to an otherwise insurmountable problem.

Beginning in 2007, the advertising ecosystem gradually became crowded with new players aspiring to fuel the programmatic placement of advertising. It was a change akin to what happened in the capital markets, as trading shifted from open-outcry exchanges to electronic trading on fully automated exchanges. Advertising was ripe for this shift, because large swathes of ad dollars were already buying digital inventory. Digital, today, accounts for one in four of ad dollars spent.

Of course, electronic markets operate in real time, or near to it. That suits online media just fine, because web pages, like smartphone screens, are also served up in real time in response to user queries. Today’s ad exchanges enable so-called real-time bidding (or RTB) on inventory that is bought and sold in 100 milliseconds per transaction—faster than the blink of an eye.

With increasing velocity has come expansion in scale and reach. While traditional media planners may analyze 10 to 20 ad buying opportunities a week, automated buyers of online advertising often analyze millions of ad buying opportunities a second.

The world’s digital ad markets already make available 100 billion impressions a day. Each of these impressions is qualified by as many as 100 variables, such as specific publisher sites, pages on site, dimensions of ad unit, device types, and so forth. In addition, each variable may have appended up to 100 different values, such as time of day, day of week, device location, local weather, regional sentiment, and so on.

If you calculate the daily number of permutations bidders on ad exchanges might consider in analyzing whether to buy specific impressions, and calculating what to bid for each of them, the answer comes to a staggering 1 with 15 zeroes behind it. That’s a quadrillion—a million billion possibilities. Only a machine could think through such complexity.

And that’s with only 20% of digital advertising already gone programmatic.

As every medium becomes addressable (programmatic ad buying has already extended its precision targeting to mobile devices, digital out-of-home displays, and even print), this kind of advertising automation will only become more mainstream.

As this drama plays out, it’s worth asking: Is advertising a bellwether for all of marketing? If so, we will soon see a comprehensive array of marketing functions transformed by programmatic techniques, enabled by enterprise software that goes beyond ad-tech. What Salesforce.com did for sales management and NetSuite did for financial management, software-as-a-service providers will do for marketing, by automating much of what marketers do every day. Such solutions are already known as mar-tech—or marketing technology—and they are just starting to take hold.

When that happens, software systems will make it possible to manage ROMI, or return on marketing investment, with a new level of rigor. Instead of setting advertising budgets on quarterly cycles, marketers will launch ad initiatives whenever opportunities emerge, and they will optimize them for efficiency and effectiveness on the fly. Bidding on ad exchanges already happens in real time; enhancements in media placement and creative execution (for example, what image goes with what copy for a given recipient) will occur with similar speed. The “budget cycle” is already a quaint idea. It will soon be a thing of the past.

When this happens, CMOs and CFOs will join forces as never before. Together, they will enable a new marketing model that blends art and science—the power of human creativity married with the split-second precision, and profit potential, of marketing automation. This will signal a brave new world for marketers—at least, for those who face the fact that it’s do or die. My bet is: it’s embrace the future, or say a not-so-long goodbye.

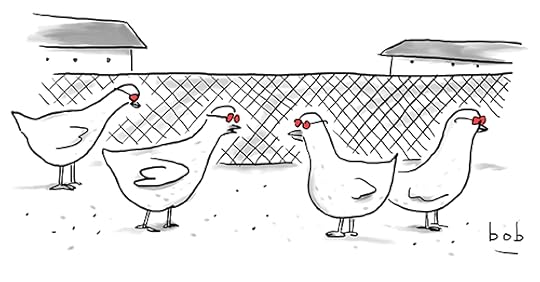

Strategic Humor: Cartoons from the July–August 2015 Issue

Enjoy these cartoons from the July–August issue of HBR, and test your management wit in the HBR Caption Contest. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

“So, has anyone figured out why we’re all wearing sunglasses?”

Bob Eckstein

“My research paper wasn’t accepted by any of the juried publications, but it’s regarded throughout the academic community as highly downloadable.”

Paul Kales

“And I’m proud to say that we’ve adopted not only a paperless environment but a peopleless one too.”

Susan Camilleri Konar

Harley Schwadron

And congratulations to our July–August caption contest winner, Laren Hagen of Seattle, Washington. Here’s the winning caption:

“Our VC firm takes a two-tier approach: first the seeds, then the money.”

Cartoonist: John Klossner

NEW CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your caption for this cartoon in the comments below—you could be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free book. To be considered for this month’s contest, please submit your caption by July 14.

Cartoonist: Damon McArthur

Why Interconnectedness Matters for Industrial Companies

Sponsor Content Insight from GE.

The convergence of the digital and the physical in the industrial world is a profound transformation that is far from fully appreciated. A connected device or machine becomes something entirely new. A smart phone, for example, still performs its original function; it allows you to make and receive telephone calls. But interconnectedness has rendered this a secondary function. The smart phone has new ways to make us more connected and informed (video chat, social networks, e-reader, and news and weather alerts). It is our concierge (restaurant reviews and bookings, taxi caller, online shopper). It is our entertainment system (music, TV, and games). It controls our thermostats, alarm systems, cars and more. A smart phone today is a fundamentally different object.

Cars are undergoing a similar transformation. Self-driving cars are already a reality. They can guide us on the most efficient route through web-enabled navigation systems and find the nearest gas station or restaurant; thanks to sensors, they can watch out for us, warning us if we stray from our lane, if we are about to turn when someone is in our blind spot, if we are at risk of hitting a pedestrian. In a Tesla, some technical problems can be fixed remotely by a technician at a computer hundreds of miles away. A car today is a fundamentally different object.

In a similar way, a company producing interconnected industrial devices becomes a fundamentally different company.

We have argued in previous work that the Industrial Internet and Advanced Manufacturing are not only transforming individual machines and systems, but they are also changing the nature of economies of scale, transforming the economic landscape and blurring the lines between manufacturing and services. In a similar way, industrial companies that combine the digital and the physical open entirely new dimensions in the way they operate and in the value they can provide to customers and shareholders.

Connecting the digital world of research, design, engineering and manufacturing enables a company to drastically reduce the time to introduce new products, leading to faster responses to customer needs and higher engineering productivity. Translating real-time factory and supply chain data into insights makes those factories and supply chains able to respond much faster to shifts in customer needs and external shocks. Linking engineering, supply chain operations, and services data through the cloud means operators can optimize factories and products in real time and continuously improve them throughout their lifecycle. As a result, machine uptime, throughput, and inventory turnovers increase. Higher responsiveness leads to higher sales.

Combining deep expertise in both digital technology and industrial machines is not easy. Both fields require complex and sophisticated domain expertise, and are experiencing fast-paced innovation. To be successful, a digital-industrial company must keep ahead of the curve on both fronts and be able to merge them seamlessly in a way that maximizes value. Just like innovation, design and manufacturing need to be closely intertwined to learn from each other and adapt to each other, so digital technologies and industrial manufacturing need to be melded to learn from each other and spur each other to reach higher levels of performance. Software development must be guided by the industrial machines’ purpose, potential and limitations—and vice versa.

GE has achieved this combination by establishing a new Software Center of Excellence (COE) in San Ramon, Calif. With an investment of $1 billion in software and analytics over three years, GE has become one of the major software companies in the world with the San Ramon Center and regional software centers in Europe and China. GE now employs 14,000 software engineers.

More than 1,000 of these software and data science experts are concentrated in the San Ramon COE, working seamlessly with their counterparts in the company’s industrial divisions from Oil & Gas to Transportation, from Aviation to Healthcare. Combining the software skills of the COE’s experts with the sectoral experience of data scientists and data engineers in the industrial businesses is essential— both to maximize the joint value of digital and physical as well as to ensure the compatibility and adaptability of software solutions across industries.

Creating value: The platform and Industrial Internet solutions

Platforms are essential to enable and monetize the value of interconnectedness. Interconnectedness is all about communication, collaboration and compatibility, including for big industrial equipment, and it all starts with platforms. The power of platforms has been abundantly demonstrated in the digital world; just think of the burgeoning range of increasingly powerful apps on our smartphones.

A powerful platform can facilitate the compatibility of applications, delivering a number of benefits:

i. collecting and analyzing data from a larger set of different industrial assets, creating a deeper and more informative information set that delivers more effective insights;

ii. enabling the interoperability of a wider range of assets within an industrial operation or system, boosting operations optimization;

iii. allowing applications to be adapted and adopted across different industrial sectors;

iv. making it easier for developers, engineers and data scientists to collaborate on a wider range of industrial solutions, leveraging the Global Brain to the maximum effect.

Most engineering and manufacturing system design tools, as well as factories and supply chains, have a plethora of data sources that are often neither connected nor integrated. To unleash the power of data integration and systems-level analytics and optimization in manufacturing, it is critical to ensure interoperability between data sources.

Much effort has recently been expended in integrating the data of design, product engineering, and manufacturing engineering through product lifecycle management (PLM) tools. But we have yet to reach the stage where a change in design automatically propagates through all virtual validation tools, such as robot and controls emulation, throughput and process simulation, and productibility and model-based manufacturing tools.

In factories and supply chains, it is not uncommon to find 20 or more separate data collection systems, from Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) to Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES) to energy management and homegrown quality systems. In fact, from a data collection perspective, every machine or controller might generate megabytes of data that often are not used to their fullest extent.

Integrating and fusing those data into one interoperable platform allows engineering, factory and supply chain leaders to gain visibility over their functions and to understand the system-level trade-offs of their decisions. Furthermore, the interoperability platform enables the development and implementation of generic engineering, factory, and supply chain tools that require only minor customization for different businesses and plants. These tools will unleash the power of analytics, simulation, and optimization providing leaders with (1) visualization of key performance integrators, (2) real-time decision support, and in some cases, (3) optimization and automation of decisions allowing them to focus on strategy and ‘exception management’ rather than day-to-day operations.

Platforms will play a key role in accelerating the growth and unleashing the value of the Industrial Internet, and the Future of Work more broadly. GE has developed Predix, our proprietary software platform for the Industrial Internet. Predix is designed specifically to meet the requirements and characteristics of industrial systems: it guarantees data security as well as mobility, it is optimized for machine-to-machine communication, and it supports distributed computing and big data analytics. Predix will support the rapid development of a growing number of applications for asset and operations optimization for a wide range of industrial sectors.

See how GE can give you the edge: gesoftware.com

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers