Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1275

July 9, 2015

Africa’s Unique Opportunity to Promote Inclusive Growth

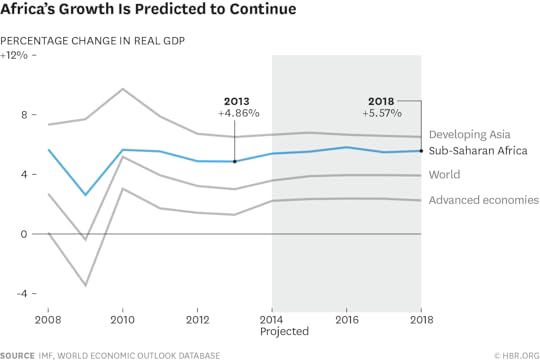

Six years after the global recession began, many parts of the world are still struggling to achieve growth. For the last decade, Africa’s GDP has been growing quickly. According to the IMF, it’s likely to remain that way for the foreseeable future:

The question Africans ask of their leaders now is: Will we grow fairly?

Income inequality is challenging the credibility of institutions and leaders everywhere in the world and Africa is no exception. But with robust growth rates and economies unburdened by legacy structures of the last century, Africans can innovate beyond what others are doing.

The African Development Bank (AfDB) is the most visible organization tasked with shepherding that inclusive innovative growth. Based in Abidjan, the economic capital of the Ivory Coast, 60% of the bank’s shares are held by the 54 countries in Africa, and a minority stake is held by 27 partner countries, including the U.S., China, and most countries of Western Europe. The AfDB has the strongest credit rating of any organization in Africa and in 2008, it surpassed the World Bank in lending to Africa, a signal of Africa’s growing agency in its own development.

In the coming years, expect the AfDB to pioneer approaches to inclusive growth. In May, AfDB shareholders elected former Nigerian agriculture and rural development minister Akinwumi Adesina as AfDB President. Inheriting a strong institution astride a growing continent, few tasks rank higher for Adesina than achieving more equal, inclusive growth. “As I travel across Africa, I notice two things about how we’re growing,” Adesina told me recently. “I see the sparkle in the eyes of a few. I get a sense of disenchantment and exclusion from many, many more.”

Adesina competed for the AfDB presidency against several accomplished bankers and finance ministers. He prevailed, in part, because his background is well suited to the task at hand. Adesina grew up in modest surroundings (“in a building with fifty people using one toilet”). He earned his way to a scholarship in Nigeria and a doctorate in agriculture economics at Purdue University. Later, as a project officer at the Rockefeller Foundation, he channeled resources to risk mitigation schemes that allowed banks to better serve small farmers. Then as Nigeria’s agriculture minister, he implemented a new e-voucher program to directly connect farmers with fertilizer producers and distributors – making the process more efficient by removing government as the middleman. He also partnered with Nigeria’s central bank to create a $350 million risk-sharing fund to encourage more banks to lend to farmers. Agriculture as a share of total lending in Nigeria has since grown from nearly zero to 7% in three years. Adesina’s success in applying market mechanisms to create widespread opportunity lead Forbes to name him African of the Year in 2013.

As Adesina takes the helm of AfDB, he has a unique opportunity to lead inclusive growth in Africa, and influence a world looking for markets that better serve people. Three actions will amplify his impact:

Modeling a new collaboration with the corporate sector. The relationship between government and business is under suspicion everywhere. Each country I’ve been to in Africa has some cronyism. However, the trans-African economy that extends across national boundaries is new and lacks calcified relationships. It displays a healthier, more transparent dialogue that can advance public policy and catalyze investment. That’s a nascent trend in need of a champion. In setting AfDB strategy, Adesina has the opportunity to engage the finest business minds around the world in the task of building a more inclusive growth model from the ground up.

Innovating away from past exclusion. From infrastructure to consumer purchasing, the current global financial architecture has mostly been built by the Western economic powers of the last century, using Western technologies. Africa has begun to develop its own systems, and small startups play a significant role. The Kenyan venture Cellulant produces many of the solutions that power that country’s mobile revolution, not to mention the mobile fertilizer e-voucher Adesina deployed as minister. Senegalese start up Volo recently beat the world’s largest credit bureaus in a competition to establish the first consumer credit bureau across West Africa, using biometric solutions and credit algorithms to redefine who gets credit. Adesina can challenge such disruptors to multiply the impact of the AfDB, and model financial architecture that is more accessible and transparent.

Using the bully pulpit. For all the global rhetoric around inequality, the absence of credible global voices on the topic is notable. The World Bank, beset by internal struggles in the short term, is facing challenges to its influence over the long term. The IMF’s mandate is more financial stability than fairness, which often puts it at odds with those at the base of society. The U.N. suffers from neither of these, but also has scant financial resources to actually participate in growth.

In another era, the leader of the AfDB might not have an opportunity to shape global issues of the day. But today, when new models of capitalism are sought and legacy structures are widely questioned, the leader astride a growing, resilient Africa can be the central figure of great change.

The world is not used to looking at Africa as a pioneer, and it is only beginning to grasp the region’s importance as a locus of global growth. Inside Africa, leading change agents often decry African inequality, instead of seeing it as part of a global phenomenon that Africa is singularly suited to address. Overcoming those dynamics is a challenge fit for a great institution that’s properly led.

How to Handle Rebellion on Your Team

Photo by Andrew Nguyen

Have you ever been blindsided in a meeting? You adequately prepared. The objectives were clear. But then, BLAM! Someone objects to one of your assumptions about halfway through the meeting and others just add to the objections. You try to explain your reasoning, but no one comes to your defense. Others join in and you feel as if you are at the bottom of a Rugby pile-on. It seems like chaos and anarchy have taken over, and your meeting is about to end with no clear resolution.

Far too often, executives try to minimize this possibility by making meetings “rubber stamp” events, where everything has been decided ahead of time and there’s no room for open discussion. But that’s a huge mistake. Repressing differences of opinion makes you less adaptable and make your meeting a boring waste of time. Instead you need to be open — and ready to handle — differences of opinion, dissent in the ranks, or even outright rebellion. Diversity of opinion is when one or more people offer a different way to view the situation. Dissent is when there’s a disagreement with a position or proposal. And rebellion happens when a dominant coalition or a sizeable force outright defy or contest your right to be the team leader. While these three things are quite different, they’re connected (a difference of opinion can quickly downward spiral into rebellion, for example) and you may feel besieged no matter which is happening to you.

The best advice I ever got about how to handle these situations was from a kindergarten teacher (who also happens to be my wife). She pointed out that when children get worked up in a class, and others get caught in their emotional frenzy, the only thing to do is to distract them. Telling them to calm down does not work. Asking them to reconsider does not work. You may have experienced a similar downward spiral of emotional contagion in an airport lounge when your flight is delayed another three hours, or at a sports event when a fight breaks out on the field and spectators join in. But in such heated situations, how do you distract people in a way that’s useful without treating them like kindergartners? Or seeming like you’re trying to manipulate them?

In the moment you’re feeling besieged, go back to basics – talk about the vision or purpose of the organization or group you are leading. Psychology studies show empirically that shared vision plays a major role in leadership effectiveness, engagement, and citizenship – and it invokes neural networks and hormonal systems that help us open up to new ideas and others’ opinions.

For example, in one study I did with Edward Mahon and Scott Taylor, we showed that members of knowledge worker teams (half from consulting companies and half from an R&D division of an industrial company) were more engaged if team members had emotional intelligence competencies (as seen by others in the team, not self-assessed). But when the team members showed a high degree of shared vision in their team, the engagement scores jumped considerably higher. In another study, Joannn Quinn showed that physicians were more likely to be seen as effective leaders when they demonstrated a higher degree of shared vision in their relationships within the hospital.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Leading Teams Ebook + Tools

Leading Teams

Ebook + Tools

Mary Shapiro

39.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

We understand why this occurs when we look at the two dominant neural networks we use at work (and during much of our waking hours). Cognitive neuroscientist Tony Jack and colleagues have shown that the Task Positive Network (TPN) — a network of areas in the brain that respond to attention-demanding tasks in functional imaging studies — enables us to focus, solve problems, and do analytic work with numbers and abstract concepts, while the Default Mode Network (DMN) — a network of brain regions that are active when you’re not focused on abstract tasks — enables us to be open to new ideas, people, and moral concerns. The dilemma is that these two networks suppress each other. Focusing on metrics and financials closes a person to considering new ideas, seeing others, and considering whether something is fair or just. Several of my and Tony’s fMRI studies have shown that thinking about one’s dream of the future – one’s vision — and then discussing that vision with others activates the DMN. If we are stuck in the TPN, then we are likely to analyze the situation abstractly, which leads to a more defensive and closed response. When it comes to team rebellion, dissent, or diversity of opinion, we tend to reject what’s happening and become resistant, thereby escalating the negative emotional contagion rather than resolving or calming it.

The practical implication of all of this is that you simply cannot calm these awkward types of team encounters with emotionless reason. That just makes it worse! Instead, you need to essentially toggle between reason and emotion, thereby encouraging others to do the same. Specifically, in the heat of the moment, you need to:

Pause and take a few deep breaths to settle your own anger, panic, or confusion.

Ask the group to pause.

Affirm the group’s ideas with statements like, “You are raising some important points. Let’s make sure we consider all perspectives and make this a better decision.”

Try to guide the discussion to something bigger than the immediate question. “Before returning to the discussion about tactics and details, could we spend a few minutes refreshing our memories about our vision and purpose – why do we exist?”

Ask how each of the arguments presented would help the team live that vision and pursue that deeper purpose.

Once when I was CEO of a consulting company with over 100 full-time employees, I heard some grumbling and dissent from a number of the consultants. I brought five of the most senior team members into my office, one at a time, and asked what was going on and how they and others felt. When I thought I had heard them, I asked them for another 15 minutes of their time. I said that I was beginning to worry about the firm’s future and how we would distinguish our products and services. I then asked them, “What do you think our clients might need in five to 10 years? What are the deeper or emerging issues they will be facing?” At the end of the conversation, I assured them we would work hard to resolve the issues they raised and also thanked them for their creative ideas about the future. I opened the next staff meeting with two agenda items: (1) a summary of what I had heard that was troubling people, and then asking for an open discussion of how we might address the issues; and (2) a brainstorming session on what our clients might need in 5-10 years, beginning with some ideas from these conversations.

This type of approach creates a time shift in perspective, refocusing people on their shared purpose, not on the tactics for getting there. Try it next time you feel blindsided in a meeting. You may be surprised to find how shifting the conversation to a shared purpose can diffuse emotions and get your team back on a more productive, collaborative path.

Your Calendar Needs an Upgrade

A little data-driven self-knowledge can be a wonderful thing. As Lenore Skenazy points out in her amusing Wall Street Journal review of Laura Vanderkam’s I Know How She Does It, even the most successful super-achievers remain oblivious to where their time really goes.

“Never one to take the lazy approach,” Skenazy writes, “[Vanderkam] decided to gather hard data. So she solicited time logs from nearly 150 women making at least $100,000 a year who have at least one child under 18 living at home.”

“The result? A time-diary study of 1,001 days, divided into half-hour chunks. These detailed diaries…show a whole lot of work going on but a whole lot of leisure time, too.”

In fact, Skenazy reports, “…once they looked over a week’s worth of their own activities, they were surprised by the large amount of time they spent with their families. Wrote one: ‘I no longer feel guilty.’”

That’s liberating. “Until we can manage time,” Peter Drucker declared in The Effective Executive, “we can manage nothing else.” To truly see how time is spent, invested and/or wasted transforms how its value is understood. Greater self-awareness about time inspires greater time for self-awareness.

For Vanderkam’s women, self-knowledge empowered. That power of self-knowledge didn’t merely help them work smarter, it made them feel better, as well. Win/win. But they ultimately had to see it to believe it.

In an era of Outlook, Google and iWatches, who doesn’t (digitally) manage their calendars and review schedules? No, there’s nothing novel about time management. But virtually everything about its tools and technologies is in flux.

So let’s update and upgrade our approach to time management. There’s no reason it can’t be better and more innovative — all the technical ingredients are there.

Self-quantification has quickly become the most valuable coin of the introspection realm. Fitbits and Garmins track steps and heart rates; Mint and American Express monitor expenditures; a nascent Google app promises to instantly convert photos of your food into calorie counts. There’s no shortage of selfies. Media and methods for self-monitoring along multiple dimensions have exploded exponentially.

But time management has seemingly stood still. As I reviewed my calendar, I was struck by its visual banality. No pie charts; no histograms. No creative visualizations of the whos, hows, and whats associated with the whens and wheres. No synthesized, aggregated, or comprehensive views were readily available. No computational comparisons of time spent/managed in the immediate or distant past. Visually and algorithmically, my email, searches, and social media were “smarter” than my calendar.

My calendar(s) should be telling me where—and how—I’ve been spending my most productive time at work and leisure. My calendar should flag my “Top 5 Timewasters” in the next month. There should be graphics dynamically illustrating the three most significant “time shifts” in emphasis over the past 100, 365 and 1000 days.

Where are time management’s counterpart to selfies? Who will be the Edward Tufte of personal productivity?

Emulating Vanderkam, I asked more than 20 high-performing colleagues and acquaintances this question: Do you view—or review—time spent in any sort of interesting or novel way?

The overwhelming answer was “no.” Almost all of them scrupulously managed their calendars, contacts, and to-do lists. But barely a handful broke the bonds of a calendar format to map time and effort. Just as intriguing, no one said they consistently compared/contrasted their time allocations from six months, a year, or three years ago with how they managed time now.

A couple of finance people converted Excel spreadsheets into calendars that let them chart time spent and deadlines in genuinely intriguing ways. Another used Toggl-like apps for visualizing their life as a series of color-coded projects to be managed. Another pair embraced the “personal kanban” approach to manage calendars as workflows. Their time management was “lean” (or just-in-time.)

Each of these approaches was fascinating and revealing. None were comprehensive or holistic.

The oddest factoid? Over half of these informal respondents were serious self-quantifiers. They knew how many steps they took in a day and how fitful their sleep had been. Examining patterns around health and fitness, yes; visualizing yesterdays and tomorrows from new angles, not so much.

Arguably the best way to answer, “Where did the time go?” is to ask “How is the time management?” It’s time for our calendars to become better partners not just for better scheduling our futures, but for better understanding our pasts.

July 8, 2015

How to Get the Most Out of a Conference

Conferences are an overwhelming rush of presentations, conversations, and potential meet-ups, and it can be tough to know where to focus your time. How do you figure out which sessions to attend? Should you skip the keynote to meet an important contact? How many coffee dates are too many? And what should you do if you’re an introvert who hates small talk?

What the Experts Say

Professional conferences are an unavoidable fact of working life. And even if you’re an introvert who dreads the multi-day extravaganza of breakout talks and cocktail-infused networking sessions, you must resist your impulse to stay home, says Francesca Gino, a professor at Harvard Business School. “Skipping conferences is problematic because you’re missing out on the benefits of networking,” she says. “Today, probably even more than ever before, networks are a key form of social capital for achieving goals in both your professional and personal lives.” And meeting people at conferences “who likely have the same interests as you and are highly relevant to your work” is a good way to nurture and expand your network, says Dorie Clark, author of Stand Out Networking. “The fact that technology has made it easier to interact with people across great distances and time zones actually makes face-to-face interaction even more valuable.” Here’s how to get the most from the conferences you attend.

Change your mindset

Despite the known benefits of having an extensive and diverse network, many people “shy away from the opportunity to create new connections because networking makes them feel inauthentic and physically dirty,” says Gino. To reduce these feelings, she suggests changing your mindset and motives. You’re not just networking because you should; you’re doing it because it’s good for your career. She says that people who focus on their professional aspirations “network more frequently and experience decreased feelings of dirtiness” compared to those who are focused on merely meeting professional duties and responsibilities. As you’re getting ready for a conference, “try to stay motivated to network professionally for the growth, advancement, and accomplishment” that it will bring.

Pre-introduce yourself

Weeks before the conference starts, “think about the people you would really like to get to know and then carve out time to accomplish that goal,” says Gino. Clark recommends creating a “priority wish list” of people you’d like to meet. Send those people an email introducing yourself; if possible, get an introduction from a mutual friend or colleague. If the person is presenting, tell her that “you’re going to make it a point to come to her session,” says Clark. “There’s a lot of fear when presenting that no one will come to your session so the fact that you’re making the effort will be appreciated.” If the person is not presenting, invite him for coffee. Or inquire “if there’s any session he’s excited about going to, then ask: Can we sit together?”

Be strategic with your time

Consider two things when choosing which sessions to attend. “A session should fulfill either a content goal, meaning the talk will be educational, or it should fulfill an interpersonal goal, meaning you want to meet or support the person who is presenting,” Clark says. The keynote speech is usually skip-able, but because someone famous often delivers it, “it’s fun to go,” she adds. “It’s likely to be entertaining and will give you bragging rights as in: ‘Hey, I heard Elon Musk speak.’” That said, “The keynote doesn’t have much networking value beyond being a conversation starter.”

Further Reading

A Smarter Way to Network

Career planning

Magazine Article

Rob CrossRobert J. Thomas

Successful executives connect with select people and get more out of them.

Save

Share

Network on your terms

If plunging into a crowd makes you uneasy, you’ve got to “take initiative to create a situation where you feel comfortable,” says Clark. Perhaps one-on-one meetings are better for you or small group settings. If so, Clark suggests making a reservation at a local restaurant for about eight people before the conference. Then invite people from your wish list. “You want it to be a mix of people you know and people you would like to get to know better,” says Clark. “Tell them you’re bringing together a group of interesting people and you’d like them to join.” And be sure to tell them why the dinner is of interest. “If she’s a tech entrepreneur, tell her that you’re also inviting venture capitalists,” for example.

Listen more; talk less

When you’re attending a semi-professional, semi-social networking situation — such as a group dinner or conference cocktail reception — your goal is to “allow enough space for others to shine,” says Clark. Harness quiet power by asking thoughtful questions and listening carefully to how others respond. Having conversation starters at the ready can make small talk more palatable. For example, you might ask: “Which work project are you most excited about right now?” or “Which session are you most excited to attend?” If you’ve invited people together, it’s also important that you “exert sufficient control” of the situation. “Make sure people are interacting with and getting to know each other,” she says. Ask people to introduce themselves. Think of commonalities among group members and highlight those when you’re making introductions. “Try to bolster group cohesion rather than letting it be a fragmented experience,” says Clark.

Manage your existing connections

Conferences can be useful venues to solidify your current professional relationships. After all, says Gino, “good networking not only means creating new connections. It also means maintaining and strengthening existing ones.” But don’t spend all of your time with people you already know. That defeats the purpose of going to the conference in the first place. “If you know beforehand that certain colleagues are likely to glom on to you, draw clear boundaries — for both of your sakes,” says Clark. Having existing dinner or lunch plans can be handy. “Say to your colleague: ‘I need to meet new people tonight, but tomorrow I’m going to a session that I think we’ll both find interesting. Would you like to go together?’”

Make time for yourself

Conferences are exhausting, and can be especially so if you’re not an extrovert. “The fundamental truth about being an introvert is that you need to manage your energy differently from other people,” says Clark. “You need to know when you’re on the brink.” And so if you spend five days pushing yourself to attend every luncheon, cocktail party, and networking reception, “you’re going to be worn out and frayed, and you will not be at your best.” Put simply: Skip happy hour. In its place, do something restful or restorative. This is sound advice for both introverts and extroverts. “It’s easy for any professional to lose sight of self-care” because he or she is busy, adds Clark. Eating well, exercising, and getting enough sleep are important to our health. Don’t neglect your own wellbeing. One of the most important ways to do this, says Gino, is to try not to be someone else when you’re in social situations. “Focus on being yourself,” she says. “This will help ensure that you don’t stress out too much or get too tired.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Shift your mindset by focusing on how networking is good for your career

When choosing which sessions to attend, consider whether you’ll learn something or meet someone new

Take the initiative to create networking situations where you feel comfortable

Don’t:

Spend all of your time with coworkers you see every day — draw clear boundaries

Burn out — give yourself time to rest and rejuvenate during the conference

Try to be someone you’re not — putting on a false persona is stressful and tiring

Case Study #1: Organize small group gatherings and take time to recharge

Parisa Parsa, the Executive Director of the Public Conversations Project — a Boston-based group that helps workers and organizations create constructive dialog in their professional, civic, and personal lives — attends several conferences a year. “I don’t know if I will ever figure out how to make conferences not exhausting,” says Parisa, a natural introvert, “but I know what I need to do to make them productive.”

Earlier this year, Parisa, who is also a minister, attended the annual Unitarian Universalist Association conference in Portland, Oregon. Before she arrived, Parisa reached out to several people with whom she wanted to connect at the conference and invited them for coffee or a meal. “I do terribly when it comes to chatting with people on the spot, so I tried to set up one-on-one meetings so I could focus my attention and not have to fight for airtime,” she says. “Reaching out to people in advance made sure I was on their radar. They knew they were a priority to me.”

In the past, she has also arranged small group dinners around specific topics. Since most people know her but don’t necessarily know each other, Parisa gets the conversation flowing by asking everyone to introduce themselves and to provide an initial take on the topic at hand. “I like bringing people together for a smaller, structured gathering. Big groups can be overwhelming.”

Parisa also makes sure to not wear herself out by giving herself time to rest and recharge. “I used to feel that I had to be at each and every session, but now I’m more strategic about choosing sessions based on the content.”

During her most recent conference, she went for frequent walks around Portland and nipped into coffee shops to reflect on and write about the presentations she’d seen. “I tried to see little bit of the city,” says Parisa. “It’s really sad when the only part of the city you remember is the inside of convention centers.”

Case Study #2: Offer your assistance in order to be seen as a potential resource

Ron D’Vari, CEO of New York-based advisory firm NewOak Capital, is a self-described “conference junkie” who attends dozens of conferences each year. Conferences, he says, “expose me to new ideas and perspectives and give me a sense of the marketplace and where things are going.”

Earlier this year, after he learned about the upcoming Professional Risk Managers’ International Association (PRMIA) conference in New York, the first thing he did — and what he always does — was call the conference organizer. “I asked if I could help with content — I volunteered to speak or to moderate a panel, and I let them know I could help introduce them to other speakers,” says Ron. “Offering to be a part of the conference provides many more networking opportunities than merely attending the conference.”

Ron won a spot on a panel. Before the conference started, he examined the agenda and looked at the list of speakers and presenters. Whenever he came across a person he wanted to meet, he sent them an introductory email and a request to connect on LinkedIn. “That way, they know who you are,” he says.

Ron attended the conference with several colleagues but he made sure to go to different sessions and networking events. “You can’t stay in a clique with colleagues,” he says. “It’s time to get to know other people.” After all, “conferences are expensive. You’ve got to be able to get your two grand’s worth of connectivity.”

When networking, Ron also makes an effort to do more listening than talking. “My objective is be seen as a resource for people. I want to engage them in a way so that when they have a technical question down the road, they think to pick up the phone and call me.”

At the PRMIA conference Ron made many connections, including a Fed official with whom he is currently writing a paper.

Gestures Will Be the Interface for the Internet of Things

The human body interacts with the physical world in subtle and sophisticated ways. Our eyes see a rainbow of color, our ears hear a range of frequencies, and our hands are great for grabbing whichever tool our creative brains can invent. But today’s technology can sometimes feel like it’s out of sync with our senses as we peer at small screens, flick and pinch fingers across smooth surfaces, and read tweets “written” by programmer-created bots. These new technologies can increasingly make us feel disembodied.

As people and companies prepare to adapt to the Internet of Things (IoT), with its ever-widening focus on machine-to-machine (M2M) communication, it’s a good time to ask where people will fit in. What will future “H2M”— human-to-machine — interactions look like in a world where physical objects are more networked than ever and are even having their own “conversations” around us?

One answer is gestures.

We have become familiar and even comfortable with gesture technology whether we realize it or not. From smartphone screens (pinch to shrink and sweep to scroll) to infrared sensors in bathroom faucets (don’t hold your hands too close), we have been trained to interact with “smart” objects in particular ways.

Gesture technology is important because when it is implemented correctly, it becomes something we barely think about. It can make basic interactions with everyday objects simple and intuitive.

In our research into a discrete class of offerings we call Living Services — that is, new IoT-based services delivered to people in the context of their everyday lives — we note several ways companies are testing uses for gesture. For example, Ericcson is experimenting with a product it calls Connected Paper to turn the human body into a sort of antenna. The product prints a circuit or tiny battery directly on packaging. When the circuit is touched, product information is transmitted through each uniquely identified person’s body to the phone in his or her hand. By touching a container of soup, a diabetic might see detailed information on ingredients and additives like sugar, helping her to make better decisions about what to eat.

Gesture-based technology is already being incorporated into product design by companies such as Reemo, which produces what is effectively a wrist-worn mouse. The device enables users to gesture-control connected objects ranging from lights to kitchen appliances to blinds to computer hardware.

Another promising development is Google’s Project Soli, which turns hand gestures into virtual controls — without need for a virtual reality headset. Instead a tiny sensor that fits onto a chip tracks at high speed and accuracy not just big arm-waving gestures but also sub-millimeter hand movements, using radar that allows the control of electronic devices without touching them.

Yet, as gestures become a more regular feature of connected devices, so too does the issue of “gesture conflict.” As the technology proliferates, we could see an increasing number of confusing, chaotic experiences where movements trigger unplanned actions.

Consider two broad areas of potential conflict. One is between the major technology platform owners. There is currently no standard format for body-to-machine gestures. Who will be the first to “own,” for instance, the hand gesture for a command as simple as “stop”? Without standards, a gesture that works with Spotify at home might not work in your minivan, where the vehicle manufacturer’s gestures must be used instead.

A second conflict could occur because of the fact that the gestures that are effective in one culture may not work in another. The gesture of an open palm could be used to initiate a payment, for example, but in Arab countries it would symbolize begging. Companies must be aware of these differences as they seek to sell their products and designs globally.

New approaches to human-machine interactions must be simple and natural to flourish. They should also be open. Many “wearables” currently available work only in closed ecosystems, where it’s difficult to share or analyze data across platforms.

Consumers may well resist a world in which they must choose between open and closed systems. And their frustration could slow down the uptake of these services, a potential loss for companies and users alike.

Open systems offer designers the ability to build around emerging standards. This will be critical for the sustainable growth of these technologies. The Withings Wi-Fi Body Scale is an example of an open system: the device, which measures consumers’ weight and body fat, syncs with third-party fitness app MyFitnessPal in order to automatically update the user’s weight in the app.

It’s still early for organizations designing for connected devices, and so we should expect some bumps as companies improve interfaces to better fit with the way people think and act. With openness comes a broader set of possibilities for gestures and ways to interact. Let the best gestures win.

Why Excom Meetings Are the Wrong Place to Make Decisions

It’s an age-old complaint: executive team meetings are “a waste of time.” Probe further and you’ll hear they’re “boring,” “serial one-on-ones with the CEO,” and a place where “decisions are avoided — not made.”

Executives and consultants have tried to improve ExCom (or ExComm depending on your acronym of choice) meetings through decision-oriented, inclusive agenda setting or by bringing in facilitators to keep people on topic. But the attempts don’t seem to stick. There are three reasons for this:

Reason #1: No one really wants to make decisions in meetings.

Ask executives what their meetings are for and a typical answer is “to make decisions.” But as all executives know, decisions rarely get made during meetings. Why? Despite what they say, most executives actually don’t want decisions made during meetings. Sure, they want to participate in decisions that affect colleagues or the business, but if the decision affects them, the last thing they want is a debate where their voice is just one amongst many. Better to push the debate off the agenda so they can later present their case to the CEO one-on-one.

For their part, CEOs are more than happy when decisions get pushed off the agenda because they don’t like being pressured into decision-making in a meeting. Imagine you have to decide whether to acquire a company or to lay off employees. Such decisions take time and it is difficult to predict the precise moment they are ripe to be made.

So when the agenda states that an item requires decision-making (as best practices would have it), CEOs run the risk of appearing indecisive if they judge it’s not time to pull the trigger. Plus, even if it is time to make a tough call, it is not always wise for the CEO to make his or her decision known on the spot if team members have just expressed a different view. While most CEOs have the authority to publicly “overrule” their team members, it is not something they do lightly or without preparation. Authority is like money in a bank account: it is best not to make unnecessary withdrawals.

Reason #2: No one really wants to facilitate.

Given the vague wording of agenda items (e.g. “project update” or “round-the-table”), I have often observed an executive team discussion run for 20 minutes or more when suddenly one member will interrupt another and say “But that’s not the topic we’re discussing!” An interminable debate then ensues about what the “real” topic is or should be. Another common occurrence is participants who wander off topic.

In theory, you would mitigate both problems by nominating an executive to act as a facilitator, which is why it is proposed as a best practice. But few executives want the job because there is no upside: intervene and you run the very real risk of offending a colleague whose support you need or, worse, your boss who is more often than not the source of the problem. Keep quiet and, at worse, you sit through another boring meeting and possibly catch up on your e-mails. This is not to say that executives won’t intervene when there is a critical issue. But a discussion that wanders off track doesn’t qualify. Such non-interventionism does not demonstrate a lack of courage, as some (mostly non-executives) would claim, but rather results from a rational cost-benefit analysis.

Reason #3: The CEO doesn’t really want a structured agenda.

Selecting agenda items that concern all team members is another best practice whose fit with executive team reality is questionable. The expression “team meeting” makes some lose sight of the fact that many CEOs consider it their meeting first and foremost.

It is a critical moment for CEOs because, as one executive once put it to me, “the CEO is the most manipulated person in the organization.” He was reacting to the myth that CEOs, perched as they are atop the organization, see and know everything. Research and experience tell a very different story: CEOs actually find it difficult to obtain the information they need. They must seek it proactively but when they do in one-on-ones with their executives, the latter don’t always tell the whole story fearing their boss will stick their nose too far into their business.

Team meetings fill the void because their characteristic lack of structure allows issues to surface that might not otherwise. Furthermore, a CEO is more likely to get a complete picture of those issues with the entire team on hand than sitting with a lone team member. Thus CEOs are not fond of tightly structured agendas, particularly ones that seek to involve all members, as these prevent them from probing issues they alone may see as critical. If that entails a bit of boredom for team members, so be it.

Focus on discussion, not decisions

Although executives and CEOs do their best to avoid decision-making during meetings, they do want discussions. The way in which agenda items are generally formulated, however, gives little indication as to what discussion, if any, is expected.

An effective and simple device for improving discussions is to tack on a question to each agenda item. Doing so immediately clarifies people’s expectations of the meeting. So, for example: instead of “SAP implementation update” try “SAP implementation update: what are your concerns and/or suggestions?”

Turning agenda items into questions in this way can also stimulate a discussion that will actually come close to a decision without forcing one. If instead of the item “Decide if we acquire ABC Inc.” the team sees “Acquiring ABC Inc.: what are the pros & cons?” the CEOs will probably achieve the important goal of gauging how much consensus exists on the issue.

Further advantages of turning agenda items into questions include:

Clarifying expected outcomes and thus avoiding discussions that run on because there is no defined end;

Keeping participants alert during presentations because they’re expected to respond;

Helping presenters focus on what is essential and leave out unnecessary detail that waste everyone’s time;

Ensuring a given topic is necessary. Indeed, if you can’t associate a clear question with a topic or presentation, you should revisit if the item is truly worth including on the agenda and/or if it could simply be covered with a pre-read.

Turning agenda items into questions can also be applied to that staple of executive team agendas: the “round-the-table” discussion, which is when executives are supposed to discover how their colleagues’ activities will affect them. However, it is more often used as an excuse to boast about recent accomplishments or pursue a one-on-one discussion with the CEO. While no measure will entirely prevent the latter from happening, formulating the item as a question (e.g., “Round-the-table: What am I up to and which of my colleagues will it impact?”) will better support its intended purpose.

The practice I’ve proposed is not the only way to improve the quality of executive team discussion. But more process change is not necessarily better. Turning agenda items into questions is very simple for executives to implement and follow and I find that it immediately addresses many of the complaints levelled at executive team meetings.

Great Leaders Can Think Like Each Member of Their Team

Money wasn’t the only thing that enabled financier Cosimo de’ Medici to become de facto ruler of Florence for much of the Italian Renaissance. He exemplified a special leadership skill — the ability to get diverse teams of contending bankers, merchants, and traders to collaborate effectively. How? He identified with each group’s sentiments and mindsets. With that understanding, he succeeded where others failed: He built new bridges of common purpose, resulting in a “team” that produced greater, more sustained economic, social, and cultural value for all parties — and the broader society.

Central to Cosimo’s success was what I think of as “multivocal leadership.” Multivocal leadership is not about gaining technical proficiency in multiple areas – Cosimo knew banking, but not trading, merchandising, or other areas of expertise, and he didn’t have the time to gain even nominal proficiency in other areas. Instead, multivocal leaders identify directly or vicariously through others with the experiences, mentalities, and skills of a diverse set of people, and fluently broker communication among teammates to guide collaboration.

My research with Jarrett Spiro and Balazs Vedres on factors promoting success for Broadway production teams and jazz bands showed that diverse teams were more likely to be effective if guided by a multivocal leader. Below I describe some of the key features of multivocal leaders, using the example of , an iconic Hollywood screenwriter, director, and pioneer of the action genre, who’s behind creative mega-hits including Predator, Lethal Weapon, As Good As it Gets, and Iron Man 3:

Fluency across fields and cultures: The best leaders of diverse teams can speak the multiple “languages” of their teammates, based on their own experience and learning. Black discusses how writers and directors need a way to fluently speak to actors in a vocabulary the latter group will value and understand. For example, one director we interviewed remarked that when directors impose their own view of a part, it tends to alienate the actor and others on the production. By contrast, multivocal directors get the best performance out of actors by leveraging the psychology of acting in communications. They help actors understand the full context of a given scene and to evoke emotion by connecting the role with the actor’s personal experience and empathizing with their frustration over multiple takes. The same approach enables the leader to more effectively broker exchanges among teammates themselves, too. Remember that a three-person team has three dyadic relationships, a four-person team has six dyadic relationships, and a five-person team has 10 dyadic relationships, and so on exponentially growing — making fluency among team members important for efficient, respectful communication.

Perspective built on breadth of experience and a deep curiosity about people: Multivocal leaders are genuinely interested in what drives those around them. That curiosity embraces diverse experiences and yields practical knowledge about what motivates others, and what will help them to trust you. For example, Black exhorts screenwriters and directors to take acting courses to gain an authentic appreciation for the meaningfulness of actors’ contributions to movies and to use that knowledge to guide collaboration. “It’s a way of approaching things that lets you know that, “Hey, I know how hard this job is for you. Let’s talk on your terms … because I appreciate and love actors….”

An almost painful self-awareness of one’s strengths and weaknesses: Effective leaders of diverse groups understand what they themselves bring to the table, as well as the potential limits of their capabilities. That helps them to defer to the expertise of their teammates, where needed. Black, for example, had studied theater and was interested in acting early in his career, but recognized that his shyness made him “intimidated by the cattle call auditions.” That self-awareness helped him focus on writing — and later, directing — and rely on the actors and others he worked with to bring his creative ideas successfully to the screen.

You and Your Team

Leading Teams

Boost your group’s performance.

Multivocal leadership is especially critical in a relatively new domain: data science. Handling Big Data means dealing with unprecedented volumes of information — whether terabytes of retail customer data, hospital records, or financial transactions — and complex decisions regarding questions to ask, frameworks and tools to use, and insights to seek. Success in this context requires integrating the efforts of computer scientists, physicists, computational biologists, social scientists, graphic design specialists, and others. It’s impossible for one person to hold deep expertise across all of these domains, and the individual players on data analytics teams will inevitably have divergent viewpoints, interpretations, and work styles. A physicist may value the ability to convert data-based concepts into mathematical language, for example, whereas a social scientist may believe such conversion diminishes the ability to derive bigger-picture insights from the data. A truly multivocal leader will be able to create order from this potential discord, aligning understanding and efforts into a high-value solution or product where the whole is much greater than the sum of individual contributions.

Some elements of multivocality are innate. But, you can learn the skill by following some practical tips:

Sidestep imposter syndrome: It can be easy for leaders of diverse teams to feel that they are in over their heads, because they lack the same level of expertise as any one teammate they have authority over. As noted earlier, no one individual can be an expert in every area a team represents. The most effective leaders understand and appreciate the limits of their capabilities. They lead diverse individuals to fresh solutions no one teammate could have discovered on his or her own by translating team differences into complementary skills. The strength of the wolf may be in the pack, but the highest-performing packs have multivocal leaders who believe in themselves and their cross-disciplinary abilities.

Expand your perspective — and translation skills: Multivocal leaders need to understand, interpret, and translate complex hard and soft issues to teammates and among teammates. The psychological concept of “perspective-taking” concerns the ability to place oneself effectively in another’s shoes, gaining understanding and empathy for them. You can enhance your perspective and fluency by taking a personal interest in teammates’ backgrounds and styles to understand where they’re coming from. Perspective taking for the leader begins with understanding what each teammate values and then brokering and communicating shared value among teammates.

Conduct an honest, ongoing self-assessment: Psychology research supports our tendency toward a “self-serving bias” that may prevent us from understanding our weaknesses. Such blindspots disrupt multivocality by endowing leaders with a false sense of competence that impedes their growth. Be honest with yourself about your capabilities and constraints. Meaningful self-assessment can take the form of a formal skills inventory administered by a third party or a more casual approach including inputs from your team, higher-level managers, and/or mentors. Be brutally candid with yourself to boost your collaboration skills.

Multivocality is a somewhat complex term for a simple concept: To lead a diverse team most effectively, draw on your past roles, cross-disciplinary fluency, and self-awareness to build trust, shared understanding, and momentum. You can maximize your team’s success by finding and channeling your inner Cosimo.

We Need to Move Beyond the Employee vs. Contractor Debate

Matthew Wiebe

Recently, a California court ruled that a driver for Uber was entitled to benefits as an “employee” rather than a “contractor.” Uber has since appealed the ruling. But the case raises anew the question about whether such legal actions could eventually lead to higher labor costs for the ride-sharing service and other businesses like it in the sharing economy.

But the real story is that framing the debate around whether a worker is an employee or a contractor is just missing the point.

The options for getting work done — beyond regular full-time employment — are increasing and, in a world of constant change, we should be asking not simply whether a worker should be categorized as an employee or a contractor but whether regular full-time employment is really the only way to deliver high pay and marketable skills. Shouldn’t we be developing more options outside of traditional employment that do just that? Framing the choices as “independent contractors” versus “regular full-time employees,” limits options and dialogue about how different work arrangements can — and must — provide stability, protections, and income.

A better way to frame the debate? We should be talking about “good work” not about “good jobs.” Replacing the idea of “good jobs” with the idea of “good work” doesn’t diminish the value and importance of regular full-time employment, but it places it in a context that acknowledges emerging work options — and it holds those new options to a higher standard, rather than simply dismissing them in favor of regular full-time employment.

Some Uber drivers prefer contracting while others prefer employment, so answering whether Uber or other companies provide “good work” requires reframing the question. This reframing around “good work” moves the dialogue forward in three ways:

First, reframing gets us more directly to the heart of a central issue with contract work and other new work arrangements—whether they are exploitative, taking advantage of workers who would prefer more stability or higher income but are forced to settle for less. Former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich has said: “For anybody who has to pay the bills and has a family, having no labor protections and no job security is at best a mixed blessing … At worst, it is a nightmare. Obviously some workers prefer to be independent contractors — but mostly they take these jobs because they cannot find better ones.” Yet, a study of 33,000 employees in 26 countries showed that independent workers were more satisfied, innovative, and engaged with their clients than regular employees, even those regular employees designated as high potentials. “Good work” emphasizes how we can improve contracting and other emerging work arrangements — what protections and safeguards should be built in?

Second, reframing the debate shifts the focus toward unleashing latent value for workers and society. A recent McKinsey report suggests that alternative work platforms may unlock trillions in future economic value by using their data to better source, match, and deploy workers. Alternative work arrangements, some powered by such platforms, can potentially enable boundary-less careers, lifetime learning, greater transparency about work, and even worker empowerment. Already, we see situations where the best workers (software coders, biochemistry puzzle solvers, media producers, or product designers) are available only as free agents, on platforms like Topcoder or Tongal. These platforms are expanding people’s options with an increasing array of work migrating to on-demand arrangements fueled by ever more sophisticated algorithms that match available and qualified workers with the work that suits them, when they want it. We predict that even more of these platforms will arise in the coming years, generating even more “good work” options. However, unleashing this potential requires that the platforms powering alternative work arrangements extend to the great middle of the global workforce, not simply the best and brightest or the least costly, and be held accountable for their impact on that global workforce. “Good work” brings attention to that accountability.

Finally, fast-changing future social and business challenges require inventing more creative options in the global workplace, and focusing on “good work” helps do that. My forthcoming book, Lead the Work, with Ravin Jesuthasan and David Creelman, suggests that regular full-time employment will and should remain a prominent option, but new options are emerging fast, and today’s focus on Uber is only the tip of the iceberg. Organizations must generate more options for workers, and framing the debate around “good work” encourages that innovation. Some innovative new work arrangements allow even traditional employees to work in new ways, making regular full-time “jobs” only one option for good work. Organizations like Google, IBM, Apple, and Visa regularly form alliances that borrow workers from partner companies, rather than compete with those companies to hire them, as Siemens did when it borrowed Disney marketing experts for its hearing aid designed for children. Employers can learn from them, as IBM did in creating an internal system where their employees find volunteer projects to expand their experience and visibility, beyond their regular “job.”

No doubt, shifting the debate toward “good work” not just “good jobs” means shifting the public policy debate and even employment law, and perhaps we are seeing a start.

A Mercury News article noted that Sen. Mark R. Warner, a Democratic Senator from Virginia, and former tech entrepreneur, has suggested an “hour bank” that accrues work hours and benefits no matter the employer. Rebecca Smith, deputy director of the National Employment Law Project counters that Congress should require firms to pay independent contractors overtime and other benefits. The McKinsey report suggests that new intermediaries may emerge to serve the needs for freelancers’ insurance, retirement plans, etc. Perhaps labor unions are the key. The decades-old “Hollywood Model” enables entertainment professionals to work as contractors on projects spanning many different companies, because their labor unions provide continuity in health care and pension benefits. But as laudable as these ideas are, they won’t go far enough if we’re only debating employment vs. contract work. Once we stop using the “job” as the focus, and replace it with the “work,” we’ll open up needed new dialogue and debate that includes the potential value of innovative work approaches.

As the Mercury News article concluded, “It’s time for companies, regulators, policymakers, and the public to look at whether this ‘sharing economy’ is a win-win for everyone and, if not, come up with new solutions.”

What Makes Great Salespeople

What behaviors drive successful salespeople? Last year, research by my people analytics company VoloMetrix identified three things that were highly correlated with top performing reps: More time spent with customers; larger internal networks; and more time spent with managers and senior leadership. These three behaviors persisted regardless of region, territory, or sales role, suggesting that they are foundational ingredients for success.

We came to these conclusions after studying the sales force of a large B2B software company using six quarters of quota attainment data for several thousand employees. We then correlated it against 18 months of VoloMetrix-created people analytics KPIs. Since then, we have had the opportunity to work with several more companies to perform similar and much deeper analyses.

Building off of the earlier findings, we have developed a broader framework for each of the behaviors we idenftified (two of which we combined), plus an additional one:

Customer engagement. This not not only includes overall time spent with customers, but also factors in the number of accounts touched; time spent with each; frequency of interactions; and breadth and depth of relationships built within them.

Internal networks. We’ve found that it’s useful to break internal network characteristics into three sub-categories:

General: This includes overall number of relationships within the company; time spent interacting with other colleagues; and influence within the network.

Support resources: A set of metrics focused on the relationships reps built with sales support staff, including pre-sales specialists, inside sales reps, and others.

Management: A set of metrics concentrated on relationships between reps and their direct managers, as well as broader rep engagement with company leadership.

Energy: This new angle, which is very much related to the previous two, includes a collection of metrics that measure overall time and effort exerted by salespeople.

In total, our new analysis suggests that sales success requires the right engagement model with customers, the right relationships within your own company, and putting in the needed time and energy. These insights may seem intuitive — and in many ways they are — but, according to the data, the details matter. Here’s how our findings play out:

Customer engagement doesn’t just mean spending time with more customers. We’ve stated before that top performers spend up to 33% more time with customers per week which, depending on the company, is typically 2-4 additional hours of time. It’s clear that time with customers matters. However, through further analysis we’ve found that degree of focus can matter as much or more than total time. For example, in one large B2B technology company, top performers spent 18% more time with customers per week. Yet they interacted with 40% fewer accounts over the course of a quarter allowing them to spend more time with each of those accounts relative to lower performers.

In other words, depth trumps breadth when it comes to accounts — top sellers focused on building deeper relationships with fewer customers rather than casting a wider net of shallower engagement.

Of course, these metrics are not one size-fits-all and the right balance varies by company based on what they are selling (e.g., highly consultative sales processes benefit most from depth whereas more transactional models can benefit from breadth). Regardless, these key metrics relating to time spent with customers and account relationships have emerged both as strong predictors of sales outcomes as well as highly actionable metrics for sales leaders to track, incorporate into territory design and use to help their teams improve performance.

A bigger internal network is generally better, with some nuances in sales support. No matter how we cut the data, top performers have significantly larger networks within their company (30-40% larger, which typically equates to 10-20 more people they interact with regularly), higher centrality (a measure of influence within the network), and spend more time with leadership. When you think about the level of complexity in a large organization, it makes sense that people who find ways to build more relationships get exposed to more ideas from across the business, are able to access expertise quickly when needed, and have more context about what’s happening. All of these things help them to be successful.

But building relationships doesn’t mean attending lots of meetings, especially those with 20 or so attendees. When we measure relationships, it involves both a frequency and an intimacy component. To qualify as a “relationship,” you have to not only interact with someone frequently (at least 2x per month), but that it also has to be in a relatively intimate group (five or fewer people involved in the meeting or email). So to establish a large network, you have to interact with many people, on separate threads, frequently.

This takes a lot of time. The top performers we study typically spend anywhere from 10-15 hours per week interacting with small groups inside their companies. Often sales executives balk at the idea of their reps spending so much time internally instead of out selling, but the data suggests that it is time well spent.

When we work with companies, we help them find ways to minimize large standing meetings and instead create ways to enable broader networks consisting of smaller groups of people. The unfortunate truth is that top performers in most companies are finding ways to build these bigger networks in spite of the processes they work within rather than because of them.

Management relationships are another important aspect of internal networking. Generally speaking, more exposure to senior leadership correlates with successful sales outcomes. That said, we have found a lot of variation in the specific interaction patterns between sellers and front-line managers across regions, product lines, and companies. For example, in some companies we have seen an inverse correlation between front-line manager involvement and seller success, meaning that top sellers spend less time with their direct manager than lower performers do. However, even in these situations, the top sellers spend relatively more time with other members of senior leadership.

Lastly, in complex sales organizations, the relationships between sellers and sales support staff is an area where more relationships is not necessarily better. In fact, in some cases sellers who have more relationships with sales support workers perform worse. This is sometimes the result of inconsistent pairings in which, for example, sellers aren’t able to work with the same pre-sales specialist consistently and instead have to work with a different one each time. This can lead to more relationships, but a weaker team. We’ve also seen that there is a stronger relationship between the time spent with support relationships and the complexity and number of products being sold than there is to actual outcomes. In other words, sellers who are trying to sell a broader portfolio or simply have more complex offerings are more heavily dependent on support resources, regardless of their effectiveness.

Sales is hard work (but you probably knew that already). Consistently, we’ve found that top performers simply put in more time. Their weeks are approximately four hours longer, with up to 40% more time spent outside of normal working hours compared to their lower-performing counterparts. But the answer isn’t saying that everyone should just work harder; even low performers work an average of 50 hours per week.

The implication, instead, is that every hour is precious. So echoing some of the findings above, here are some changes that could be made at the company level:

If salespeople have 15 hours available to spend with customers in a week, focusing that time on five accounts at three hours each rather than 15 accounts at one hour each is likely to lead to better outcomes

To facilitate the growth of internal networks, start with onboarding programs. New hires should meet and interact with a large and diverse set of colleagues, and can be supported through collaboration tools, trainings, coaching, and other mechanisms.

Create a model where sellers have access to consistent support resources and staff. Having to start over with a different specialist in each account adds lots of overhead and reduces outcomes.

Know that every additional product line in a seller’s bag comes at the cost of requiring them to build more expertise and more internal relationships to have a shot at being successful. While offering a broad portfolio can provide a powerful value prop to customers in some situations, the implication on sellers needs to be carefully thought through.

The right approach varies by company, and these things can and do change over time; companies that gather objective data on a regular basis to inform decision making have a massive competitive advantage over those that rely only on anecdotes and gut feel. Organizations we work with, for example, receive automated weekly updates on all of these metrics aggregated by team without any manual data gathering.

Lastly, a note on causality. All of the above metrics are highly correlated with sales success, but we haven’t yet accumulated enough data to have confidence on which of these metrics are truly causal. So while it is true that top sellers spend more time with customers, it is not necessarily true that an underperformer would suddenly become more successful simply by spending more time with customers.

That said, rigorously proven causality is not a prerequisite for learning from these insights. Quite a few companies are enjoying immense value in the predictive power of these metrics, which typically account for up to 70% of the variance in sales outcomes quarter by quarter And having access to objective, up-to-date data on what behaviors works and don’t work within a specific sales organization is a powerful compliment to existing management tools and allows leaders to set their teams up for success.

July 7, 2015

How to Break Through Deadlock on Your Team

If your team deals with important issues and team members have strong views on those issues, you can end up in a deadlock. When that happens, people dig into their own preferred solutions, operating from a unilateral control mindset where everyone believes that he or she understands the situation and is right, and that those who disagree just don’t understand the situation and are wrong. When all team members are thinking and acting this way, it creates a vicious reinforcing cycle. The more people try to prevail, the more people stand their ground, and the less likely it is that the team will ultimately resolve anything.

But there is a way to break through a team deadlock.

First, it’s important to understand how deadlocks develop. Think of them as an adult version of a connect-the-dots puzzle. In the children’s version, you draw a line connecting a series of numbered dots that are scattered on a page. If you connect the dots correctly, they form a picture, which is the solution to the puzzle. In a team deadlock, the dots represent the assumptions, interests, and relevant information that each member uses to arrive at his or her own solution. The line connecting the dots represents the reasoning process. In deadlocks, team members don’t select all the same dots, nor do they connect them in the same way. As a result, they arrive at different solutions. And everyone believes they have the one correct solution to the puzzle. Because each team member’s solution is the result of how they selected and connected their own dots, arguing about competing solutions without understanding what generated them in the first place just maintains the deadlock.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Leading Teams Ebook + Tools

Leading Teams

Ebook + Tools

Mary Shapiro

39.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Consider a three-person leadership team with members Stephen, Daphne, and Kim deadlocked about how to reduce the time it takes for the three divisions they lead to meet client deadlines. Let’s look at the dots:

Assumptions. Assumptions are things you accept as true or certain to happen without proof. The assumptions you make influence which solutions you consider effective or even possible. If Stephen assumes that all division managers are capable of performing at a certain standard, but Kim and Daphne assume that some managers don’t have the capacity to do so, their solutions for meeting client deadlines will likely be at odds.

Interests. Interests are the underlying needs that team members try to meet through their proposed solutions. Positions are simply solutions that people support that meet their interests.

People often take positions that meet the legitimate needs they face given their role in the team or organization. For example, if Daphne directs operations and Kim heads up finance, they may both take the position that the problem be solved using people who do not directly generate revenue. Their position may be based on their need that any solution be developed in a way that does not jeopardize the unit’s short-term profitability, for which they are accountable. If Stephen is responsible for strategy, he may take the position that all the managers need to meet together. His position may be based on his need to ensure that everyone understands the plan and is committed to implementing it.

The problem with focusing on positions is that team members’ positions are often in conflict when their underlying needs are actually compatible. Unfortunately, when people fail to realize this, they fail to explore solutions that everyone would likely support.

Relevant information. Relevant information is the information you use to formulate your solution. It includes financial and other data about the issue, information others have shared with you, and opinions that you value.

Whether people consider information to be relevant also affects the solutions they reach. If Daphne believes that the impending organizational change will alleviate some of the deadline challenges, she may not support a solution that commits resources she believes will be unnecessary. Similarly, if Kim believes that the new time management training program is starting to have a positive effect, she may want to delay any decision until the program has had sufficient time to show its full effect.

Connecting the Dots

To identify the cause of your own team’s deadlock and develop a solution that everyone can support, examine the reasoning that each person is using to connect their dots:

Identify the assumptions, interests, and relevant information that team members are using to reach their solutions. You can map these out using a connect-the-dots approach, or you can simply develop a list. Place the names of people next to the assumptions, interests, and relevant information they believe needs to be included; this enables the team to quickly identify who needs to explain their reasoning for each item.

Identify the assumptions, interests, and relevant information that team members do not agree on. Whether you are using a visual map or lists, circle the items that not all members agree on. In our example, Stephen, Daphne, and Kim would circle: Stephen’s assumption about managers’ capability; Daphne’s and Kim’s interest that implementing the solution not jeopardize short-term profitability; Daphne’s information that an impending organizational change is relevant to consider; and Kim’s understanding that the new time management training program for managers is having a positive effect.

Explore what leads members to include or exclude the item as part of their reasoning. For each item the team identified in the previous step, give individuals time to explain how the assumptions, interests, and relevant information they think are important influence their thinking. The purpose of this step is to understand how each team member is thinking, not for team members to try to convince others.

Agree on the assumptions, interests, and relevant information that will be considered in developing a solution. The core of this step is jointly designing ways to resolve the differing views. In our example, Stephen, Daphne, and Kim would jointly design a way of determining the extent to which the assumption that managers who report to them are capable of performing at a certain standard is accurate. They may decide to review available information or collect new information. They would agree on whether the interest of maintaining short-term profitability was critical. Finally, they would also jointly design a way to resolve whether Daphne’s information about an impending organizational change is relevant to consider and whether the new time management training program for managers is having a positive effect, as Kim believes. Jointly designing how to resolve the differences ensures that people agree on the data that will be used, how the data will be analyzed, and what decisions will be made based on the outcome of the analysis. This is the most challenging part of the process. It requires that team members be genuinely curious about others’ views and willing to examine their own assumptions and interests.

Jointly develop a solution that integrates the newly agreed upon assumptions, interests, and relevant information. In this final step, your team uses its collective creativity to generate a solution that is based on all the items they have agreed to. If your team has done its work well up to this point, then this step feels like you are solving a difficult puzzle together. The team is focused on the challenge of developing a solution, not on challenging each other.

While these steps are logical and seemingly easy to follow, to use them effectively, you and your team need to shift out of the unilateral control mindset that led you into deadlock in the first place. Most of the time, deadlock happens because we’re not fully transparent with others about how we arrived at our conclusions, we’re not curious enough about how others arrived at different conclusions, and we don’t creatively address and resolve the seemingly unbridgeable differences that form the deadlock. Making the shift to transparency, curiosity, and creativity is the key to making the process work.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers