Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1273

July 16, 2015

Dispel Your Team’s Fear of Data

Kenneth Andersson

Most people are uncomfortable with data. Estimates, analytics, and data-driven predictions — they can all be confusing and overwhelming. Some of this discomfort is based on experience. Everyone remembers a time when their data was simply wrong, a prediction was misleading, and the consequences were serious.

Until recently people could easily ignore data in their daily work. The company’s “gearheads” and “quants” were isolated in specialist departments, tech handled the mundane stuff, and managers could brush off the benefits of improved data quality with the attitude, “We’re doing just fine. Why bother?”

But now that’s changing. The headline result of my most recent “scan” of the data space is that fear has replaced apathy as the number one enemy of data. More and more managers and their direct reports sense that, sooner or later, data will infiltrate every nook and cranny of every industry, company, and department, transforming work, relationships, and power structures. Uncertainty around “what will happen to me, my work, my department, and my company?” is seeping into hearts and minds of individuals at all levels. You can spot the fear in a number of ways: Some don’t make the effort to share potentially useful data, and others (increasingly) complain that the data is too difficult to access, understand, or use, so they ignore opportunities to include it when making an important decision.

This atmosphere of fear has profound significance for managers. Fear can paralyze both individuals and teams. Workers clam up when they’re anxious, and keep valuable thoughts to themselves. Fear prevents people from trying out new ideas, lest they suffer the costs of failure (or just look stupid for trying). It hampers productivity, as people waste time dissecting rumors, envisioning budget cuts, and fearing layoffs, instead of focusing on their work.

Good managers don’t allow fear to fester in their teams. And the best way for managers to help their direct reports grow more at ease with data is to lead by example. Here are a few steps you can take to learn to use data more effectively and pass those skills on to your team.

To get started, take a hard look in the mirror. It’s okay if you’re nervous. Just don’t let this fear stop you. Instead use it to drive a sense of urgency in gaining the knowledge and experience you need.

Next, read and study. Find stories in the news and articles on the web about data to learn more about it. Pick a book or two on the topic and ask yourself, “What does this mean for me and my department?” Here’s a short list to choose from: Davenport and Harris’ Competing on Analytics, Lohr’s Data-ism, and Silver’s The Signal and the Noise (or my own book, Data Driven).

Then, find ways to practice using data. Pick something that interests you, such as whether meetings start on time, your commute time, or your fitness regimen, and gather some data, recording it on paper or electronically. Create some simple plots (such as a time-series plot) and compute some statistics (such as the average and the range). Ask yourself what the data means and explore its implications.

As your knowledge grows, push forward. Dig into other data sets to uncover the stories behind the data. Learn the distinction between causation and correlation. Construct graphics to help visualize what you’ve found. Share these visuals with your team, so they can see what you’ve discovered and how it improves your work.

Bring your new experience with data into your daily work. In an earlier piece, I outlined twelve habits of the data-driven. Pick two or three and put them into practice. For example, “the data-driven recognize the importance of high-quality data and invest to improve it.” Here, you can identify and eliminate the root cause of one data quality issue in the data you use to manage your department. Show this to your team, and get them involved.

Or consider this habit: “The data-driven bring as much diverse data to any situation as they possibly can.” Practice this habit with those you work with. When discussing an important topic, ask, “Have we really assembled the total picture? Or are there other ways of looking at this that we should consider?” Encourage your team to look for more information, and make sure that at least one new piece of data or perspective emerges.

But my favorite habit is, “The data-driven make decisions at the lowest possible level.” Push back when a subordinate asks you to make a mundane decision. Challenge him or her to gather all the relevant facts themselves, sort through the options, and make a firm recommendation. Chances are high that your subordinate will allot more time, gather more diverse data, and thus think more carefully about the decision. Routinely following this habit has the salutary effect of facilitating comfort with data and making the entire department stronger.

In the face of fear, your department looks to you for leadership. You can become a credible leader and dispel the fear of data in your team as well as your own fear by increasing your abilities and inspiring the entire department to embrace data. After all, if fear is the number one enemy of data, knowledge is the number one enemy of fear.

What We’ve Learned About Fighting Ebola

Last week, an expert panel commissioned by the World Health Organization (WHO) issued its findings on the organization’s mishandling of the West African Ebola epidemic. The epidemic, already the deadliest in history with more than 27,000 cases and over 11,000 deaths, is now in its sixteenth month with new cases still occurring in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. The panel’s report characterized the WHO’s “organizational culture” as inadequate for emergency response and, among its recommendations, underscored the need for more effective mechanisms for “research and development” of new approaches.

We couldn’t agree more about the need for innovation. There has been remarkably little generated during this epidemic. The response to Ebola has largely relied on public health strategies established over a century ago and technology that has been around for decades. These tried-and-true approaches succeeded in containing the two dozen previous Ebola outbreaks, but this outbreak has been fundamentally different from those of the past. Highly mobile populations, the spread of Ebola into densely populated cities, and the need to simultaneously manage multiple outbreaks across disparate localities have made this “epidemic of many outbreaks” difficult to control.

As the number of cases doubled every three weeks late last year, the epidemic outpaced traditional approaches and became a global threat. In September 2014, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) speculated that Ebola could infect up to 1.4 million people by late January. In the past several months, a large-scale emergency Ebola response system was created. (Given the weak and poorly functioning health systems in the affected countries, it had to be built largely from scratch.) Even now, despite massive progress in reducing cases from hundreds to now fewer than 30 a week, the end of the epidemic remains elusive: Just two weeks ago, the virus reemerged in Liberia, which was declared ‘Ebola-free’ almost two months earlier.

The unique character, scale, and persistence of this epidemic demand innovation in how Ebola is tackled. Indeed, fresh thinking and new technologies could potentially address many challenges. For example, “contacts,” people exposed to someone with Ebola who need to be monitored for the 21 days during which they may become sick, frequently elude efforts to follow them. Given the penetration of cell phones in even these impoverished countries, “contacts” on the move could readily be tracked through their phones. Difficulties in transporting blood samples, another recurrent challenge, could potentially be solved using transport drones similar to what Amazon is attempting for package delivery in the U.S.

The possible innovations are not limited to technologies alone. People suspected of Ebola infection have to be taken long distances by road in order to get tested, oftentimes crowded together with other patients from whom they could become infected. Those who turn out not to have Ebola must then be transported back to their villages where they, even with a negative test result, frequently face ongoing suspicion from neighbors. Developing ways to safely collect blood samples at people’s homes could significantly streamline this process.

In an era of big data, information from different components of the Ebola response — tracing contacts, hospitalizing infected persons, safely burying those who pass away — remain in separate, incompatible databases. Integrating these information flows and opening them up to the wider community of academics, analysts, and hackers could produce new insights. Management innovations could be instrumental in streamlining the massive coordination challenge presented by the epidemic. In Guinea, for example, the Ebola response involved more than 30 local and international agencies active in over half of the country’s 33 districts.

The Ebola response has not been without some attempts at innovation. New protective suits were designed to prevent overheating and allow health workers to stay in Ebola wards longer. A number of rapid diagnostic tests have been in development that reduce the time needed to confirm someone has Ebola, hence, closing the window during which they can transmit the virus to others. Only one of these tests has received formal approval and even that one has not been deployed because of bureaucratic delays and questions over its performance left unresolved by the several month-long validation process.

Innovation has been limited by several factors:

A flawed mindset. Traditional techniques and tools have worked in containing past outbreaks. Even as this epidemic grew, the prevailing mindset was that these established approaches just needed to be applied more widely and with better execution rather than fundamentally rethought. There has been a concern that deviating from what we know and experimenting with new ideas during an emergency could make things worse.

Difficult conditions for innovation. The Ebola-affected countries are marked by harsh geographies, poor infrastructure, and unreliable power. A shortage of people skilled in technology also undermines the ability to try new tools. Political complexities and a sense of distrust in many communities further constrain the room for creativity. In the context of the emergency, the urgent and, at times, chaotic implementation of activities by so many different organizations also confounds the ability to systematically institute, evaluate, and iterate new approaches.

Organizations not built to innovate. Many of the organizations involved in the Ebola response, such as United Nations (UN) agencies and government ministries, are hulking bureaucracies that are simply not structured to innovate. They have very little incentive to do things differently, deriving their authority by statute rather than performance. In the Ebola epidemic, the criticism that international agencies drew for letting the outbreak spiral out of control has also discouraged them from trying new approaches that may fail.

In addition, these organizations now compete with a growing field of global health actors for the best talent. Many of the most capable global health practitioners are working in funding bodies, such as the Gates Foundation, or more action-oriented organizations like Doctors Without Borders. Those with an entrepreneurial slant, in particular, are least likely to join heavily bureaucratic institutions. Smaller NGOs that are better structured to innovate, however, often have limited, short-term funding that restricts their ability to take risks and pursue new ideas.

To stimulate more innovation amidst an emergency like the Ebola epidemic, several measures should be taken:

Dedicated focus and funding for innovation. Donors should earmark funds specifically for innovation, and implementing agencies should similarly establish a deliberate focus on innovation through special “innovation units” or incentives for generating better ideas. New approaches could be tested side by side with standard methods so immediate action is not compromised. For example, in Guinea, a real-time data system for tracking “contacts” with a smartphone app that uploads into a cloud-based dashboard is being piloted alongside the traditional paper-based system and will only replace paper when it is clear the real-time system performs better.

Collaboration between innovative organizations and implementing agencies. Forums should be created for organizations in highly innovative sectors, such as technology, to come together with agencies involved in emergency response. This collision of worlds could stimulate creative thinking and collaboration around key problems. Channels should also be created whereby innovative companies can directly engage with response efforts. During the peak of the Ebola epidemic, many groups would have been more than willing to donate their time, resources, and creative skills, but did not have a clear way to get involved. Major challenges should also be put forward for crowdsourcing potential solutions. Some attempts at this were made, such as the innovation challenge hosted by USAID that led to the better protective suits. A more institutionalized approach for engaging the best minds on crucial challenges should be forged for future emergencies.

Streamlined mechanisms for evaluating new approaches. Fast-track mechanisms should be put in place to identify and evaluate new ideas so that breakthroughs can be quickly validated and scaled up. In the Ebola response, the slow and confused process for validating rapid diagnostic tests is an example of how the lack of a clear and definitive system for evaluation and approval has caused serious delays to a potentially game-changing innovation.

We live in an era where advances in technology, design thinking, and collective problem solving can generate new and better ideas. Many opportunities to leverage these possibilities have been missed during the Ebola epidemic, which, at its peak, overran traditional approaches and, even now, persists despite ongoing efforts. Innovative thinking and innovative technologies can help tackle these challenges. We owe it to the communities who have suffered to do more and to do it better and faster to bring this epidemic to an end and to more effectively respond to the next one.

July 15, 2015

Your Company Should Be Helping Customers on Social

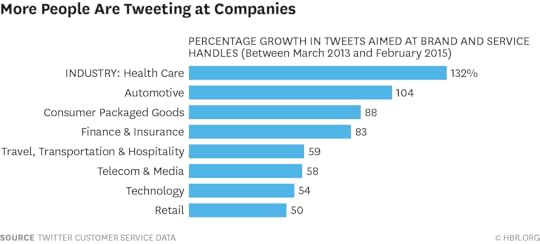

People under 35 spend almost four hours per day on social media, and more of that time is being spent engaging with brands. Our research has shown that the volume of tweets targeted at brands and their Twitter service handles, for example, has grown 2.5x in the past two years. Similarly, the percentage of people who have used Twitter for customer service leapt nearly 70%, from 22 to 37% from 2013-14. McKinsey’s analysis shows that 30% of social media users prefer social care to phoning customer service.

This is happening across age groups and income brackets: 17% of people older than 55 prefer social media over the telephone for service, and nearly half of people earning more than $200k per year prefer social media over live interactions for customer service.

So how can companies increase their ROI of social media customer service? In our experience, the best companies are building up their social media capabilities to capture value by focusing on doing two things well: building a social media CRM to increase relevance and focusing on complete customer care.

The most successful social media interactions are personal, genuine, and relevant. To scale that connectivity requires integrating social media data into your CRM system. Some retailers have been able to increase sales conversions 10-15% by tailoring their social media content based on customers’ previous purchases, according to McKinsey research.

Building an effective social CRM requires companies to:

Link social media and CRM data. Account numbers and customer IDs are easy to track, but linking social media handles with your internal account numbers isn’t as straightforward. The best companies find creative ways to get around this hurdle. For example, one telco uses a survey following customer service interactions on Twitter with an opt-in to match a customer’s ID and Twitter handle. And a leading hotel chain asks customers to direct message their account number so the company can link the social handle to their account in the brand’s CRM system. Small incentives (such as discounts or coupons) can encourage customers to provide this information.

Gather and track the right information. Social media is in effect a massive focus group that can provide intelligence about brand perception, services, competitors, and potentially disruptive trends. It’s easy to be overwhelmed by it all, so companies should prioritize gathering social data that indicate trigger events. These signal the moment when consumers are most open to shifting purchase behaviors and preferences. Creating keywords for life events and interests (e.g., “marriage,” “new school,” “change of jobs”), and then actively tracking them, can help you better tailor interactions with customers at key moments.

Keeping up with all of these social media interactions is challenging, but it helps to have a clear focus on the metrics that matter, to both the customer and the business, such as first response time, time to resolution, customer satisfaction (collected through surveys), and in-channel resolution. We’ve seen when companies do this well, they can resolve over 95% of issues through social media, while maintaining customer satisfaction levels above 90%.

Put in place processes to act on the insights. Some 72% of people who complain to a brand on Twitter expect an answer within an hour. Companies have to develop guidelines for how to act when a particular event occurs. For example, if a customer tweets about an upcoming trip but hasn’t yet purchased a flight, the airline can turn to its social CRM program to find out that this person is a priority member, and say, frequently tweets about craft beers. If the airline has guidelines in place about how to respond and what offers can be made, the people managing the airline’s social media can respond with a personalized message and a free beer coupon to help drive the customer to action. And one wireless carrier looked at customers’ social media complaints about poor service to predict churn. Employees knew to flag these “at risk” customers and reach out proactively to resolve issues. The firm reduced churn in one quarter by 50%.

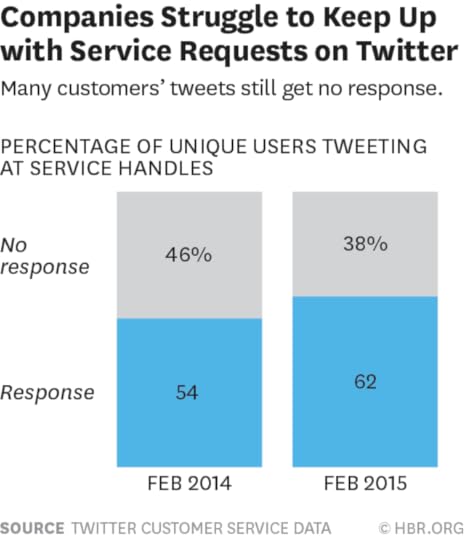

Responding to customer care issues over social media can cost as little as one sixth of a call center interaction while generating higher levels of customer satisfaction. But Twitter data shows that nearly 40% of customer tweets never get a response from the company.

The best companies look at social care not just as issues to be resolved but as opportunities to create value by cross-selling, upselling, or reducing churn. We found that companies that have developed social care capabilities to do this well – in a personal, non-invasive, and relevant way – improved year-over-year revenue per contact by 6.7% (those that didn’t saw a corresponding 12.1% decline). Using social CRM and advanced tools with predictive analytics, social media agents can move beyond issue resolution to provide tailored recommendations.

In an era when shifting a customer experience from “average” to “wow” is worth 30-50% improvements in terms of increased likelihood to recommend a company and make repeat repurchases, proactive social care is critical. To build loyalty with and attract new customers, start thinking about how to surprise and delight your customers. One leading hotel chain, for example, provides travel tips to travelers, even those not staying with them, to further its mission of hospitality. They use a tool that looks for particular keywords and provides agents with guidelines for how to curate travel tips.

While we are still in the early days of brands building their social media muscle, the strongest companies are putting in place the tools, processes, and people to unlock the wide range of value potential.

Changing an Organization’s Culture, Without Resistance or Blame

One of the biggest challenges a company can face is changing people’s behavior — getting them to collaborate and be humble, for example, or put the company’s long-term interests first. Most behavior-change initiatives accomplish little, at best.

So when we faced such a challenge at Lear Corporation, a Fortune 200 automotive supplier with 136,000 employees worldwide, we knew the odds were against us. We asked ourselves: What could we do differently?

Lear had gone into bankruptcy during the Great Recession. Getting the company back on its feet required a major boost in operating efficiency. We succeeded, but by 2013 we worried that we had taken our focus on results too far. In satisfying our demanding customers, were we pushing the organization to the breaking point?

In order to make our success sustainable, we decided to roll out a new “leadership model” for our middle- and upper-level managers. We’ve been in HR for a combined total of more than four decades, with multiple organizations, and we’ve been involved in a couple such rollouts. Our model at Lear — essentially a list of desirable behaviors — was pretty similar to what many other companies promote. We focused on the soft qualities that managers often overlook in their zeal for short-term results. “One Lear” was all about keeping the company’s interests ahead of one’s own division, function, or region. “Results the Right Way” emphasized collaboration and long-term perspective, while “Lead with Integrity” pushed for accountability and humility. We wanted strong but collegial leaders.

To make the implementation work, we took a four-phase approach, focusing on awareness, learning, practice, and accountability.

Awareness. We spent some money on publicity, including framed posters, mouse pads, and even a sculpture commissioned for the headquarters lobby. The leadership model and related descriptions went out in the 20 languages used by Lear managers around the world. But we knew all this was just a starting point. We couldn’t sit back and just let the well-publicized model do its work. It wasn’t enough to say, “The instructions are clear, we’re all grownups, so people just need to follow through.”

Learning. Too many companies skimp on this step. Any change in behavior that matters is going to be difficult. First of all, it’s just hard to translate words on a page into specific behaviors, especially when the words are about sensitive subjects. What does it really mean to “get results the right way”? Were managers supposed to be more relaxed about expectations, more focused on the process, more forgiving when their subordinates missed deadlines? How do you show empathy without seeming weak, without losing your authority?

We ended up putting a lot more resources into this step than into awareness. People needed to see what success looked like, and they needed to get support along the way. To make the process manageable for HR, we divided our 250-plus middle and upper managers into cohorts of about 65 managers each, with each cohort getting intensive attention for a three-month period.

The work started with each manager getting an initial assessment, based on surveys of direct reports, on how he or she matched up to the model. We wanted managers to know the areas they needed to get better at, as well as the strengths they could build upon. The assessments were purely for self-improvement. They had no career consequences — no one outside of HR, not even managers’ bosses, saw them.

Soon after receiving their assessments, each cohort attended a two-day retreat, with the first one in August 2014 near our Michigan headquarters. Our senior executives kicked off the retreat by talking about the key behaviors in detail. From there, we guided people through an online library of materials, centered on videos showing good and bad examples of each behavior. Then we put everyone into four-person peer-support groups, from different locations, so they could talk through the behavior in their own terms. We encouraged the groups to keep meeting throughout the process and beyond.

Practice. I’m proudest of this step, which I’ve never seen elsewhere. Real change is hard for anyone. If people are going to muster the energy and discipline to alter their habits, they need to start with self-confidence. We didn’t want to castigate people — we wanted them to feel OK about themselves, while still understanding the need for change. In essence we said: “Before, the organization rewarded you only for short-term results; now we need you to get sustainable success. It’s going to take real change for everyone.”

Framing the situation that way made a big difference. People didn’t feel blamed or put on the spot for their past actions. That made them much more receptive to the message. It helped that a lot of managers already knew that our current culture wasn’t working so well — they just didn’t know how to fix it. Because we cast the issue as an organizational challenge, not a problem for individual managers, people could talk about it and help each other much more.

We had a good message, but I couldn’t send it, nor could HR as a whole. It had to come from the leadership, and it had to come with some humility. That’s harder than you might think. It’s rare for a C-suite executive to publicly admit to struggling with a corporate initiative. We put so much pressure on leaders nowadays, and they need so much ego in order to rise to the top, that it’s genuinely difficult for them to show vulnerability.

Showing vulnerability, though, was key to getting people to take the change seriously. We weren’t going to get anywhere if it looked as though the leadership model were only for “some” people. All the ambitious managers would figure a way to game the assessments and come out clean. We needed people to really embrace the change, starting at the top.

At those learning retreats, our executives made a point of saying everyone was in this boat together. I’ll never forget our CEO, Matt Simoncini, getting up in front of dozens of managers and saying, in essence, “I’ve violated several of these model behaviors myself in the past. I’ve started to get better, but I still have a lot of work to do.”

As for checking progress, fortunately we had overhauled our performance management system only a year earlier. As one of us (Tom) explained in a previous post, instead of a big annual evaluation tied to bonuses, we now had people meet their supervisors on a quarterly basis, with no connection to compensation decisions. The new leadership model fit easily into those conversations. With the money pressure off, managers could talk more freely about their struggles with the key behaviors. Instead of hearing only the bonus rating, they could actually listen for their bosses’ feedback and advice. Managers got more-frequent, positive reinforcement, which is key to behavior change.

We wanted people to have a good deal of time to figure out and practice the new behaviors. We didn’t expect them to get it right the first time. A lot of behavior change is about failing your way to success.

Still, we did have to let several managers go, including some vice presidents. These were known troublemakers, at the extreme end of the spectrum, whom we’d previously turned a blind eye to because their results were good. People had justified their rough leadership style by saying they had “passion,” but over the years I’ve learned that’s just an excuse for bad behavior. We couldn’t have them around while we pursued the program, or we would have lost our credibility. We had many more, not-so-extreme managers I suspected wouldn’t make it either, but we wanted to give them the benefit of the doubt — and some have changed.

Accountability. After six months of development, we assess each manager again, and this time the assessments have teeth. Managers’ bosses see the assessments and start to factor them into promotion and other considerations. I remember one manager read his assessment and asked me, “Do I still have a job?” I reassured him that we were giving everyone one more chance at that point.

Our first cohort just had that assessment two months ago, and two other cohorts are still in the practice period. But already I’m seeing evidence of the change everywhere. People are more collegial and collaborative.

We’ve also been watching carefully to make sure we don’t lose our edge as an organization. The leadership model can’t become an excuse for slacking off. We still need strong operational results if we are going to stay competitive. Leaders still need to drive their teams hard, but I’ve seen them show more respect and better listening, with less micro-management.

With only a year and a half since the kickoff, it’s too soon to assess the operational results of the campaign. But our margins have been increasing in recent quarters. Core operating earnings and shareholder returns are also rising, faster than our peers’.

With each phase, we’ve created more believers in the program and gradually built up a critical mass that can change the entire culture. That’s the ultimate goal, since the new behaviors will stick only when they become unconscious norms. Better management will mean better results for the long term. We’ll attract and retain more talented employees, and we’ll see fewer managers derail because of bad behaviors. Better people will also bring long-lasting competitive advantage in our industry.

Like many companies, Lear is trying to move HR from a tactical department that manages transactions to a strategic function that develops people. Leadership models, when implemented in this gradual way, can do just that.

The Seductions of the Infosphere

Nicholas Blechman

The infosphere, as Luciano Floridi calls it, is the combination of the internet and computer technology that is revolutionizing our lives and work. He carries the intriguing title of Professor of the Philosophy and Ethics of information at the University of Oxford implying that the revolution is as much about issues of morality, identity and meaning as it is about technology.

The infosphere is an exciting prospect offering myriad new prospects for wealth and work creation, most as yet undiscovered. The idea of better lives for all is, of course, alluring. But there are few unmixed blessings in this world so we need to have a care lest we lose some of the best of ourselves in this new era. Today’s technologies would like to reclassify us as bundles of data—be they words, numbers, or images—that the infosphere can process more easily. For example, the computer on the help line may call me by my first name, but it’s really interpreting me as one more piece of data, not me as I know myself, complete with likes, prejudices, fears, and hopes. This kind of algorithmic society , with its programmes and routines, will take the stress out of life—but also much of its meaning if we let it.

This meaning is rooted in our consciousness, which cannot be coded or made into data. Nor can the virtues of beauty, truth, or goodness, which you recognize when you see them but cannot adequately measure or define. Love, trust, loyalty, and judgement—the essentials of our human relationships – are also immune to sensible quantification. Trying to codify them is pointless. But will what cannot be measured eventually not matter? And over time be thought not to exist? Could an algorithmic society reduce us to no more than bundles of data, trundling through life, pushed and pulled this way and that? Yes—if we continue to be seduced by the ease that it offers.

We are immersed in many programs of the algorithmic society. Much of them we never see because they are embedded in the things around us, easing, but also controlling, our lives. There lies the rub, or at least one rub. “We are being sedated by software,” the President of Britain’s Cartographic Society said, worried that the young would no longer be able to read a map, because they could instead rely on GPS and their satnav. Soon we won’t need to know how to read, cook, drive a car, or remember anything, as long as we know our ID and password—and even these will eventually be called up by putting your eyeball to a monitor.

Unfortunately not all of this data is what it seems to be: concrete facts safely lodged somewhere. Much of it is evanescent and rainbow-like, here for a while before ultimately fading away. For example, when a website is updated, the information that was there before is gone, forever. Even Google recommends that we print out any special photographs lest they disappear or we are unable to retrieve them a few years later. In other words, the data and technologies we use to structure our lives and make them easier aren’t always reliable. Any secrets we committed to those old floppy discs will remain secrets forever once we lose the means to access them. We may need printed documents and real books and strong memories after all. A self-driving car is magic until the operating system freezes. 3-D printed food is fine until the power goes out.

The algorithmic organization, too, is already here, at least in part. It’s built on the theory that the more work that can be routinized and programmed in advance, the more efficient the organization will be. But efficiency is not the same as effectiveness. Doing things well is not the same as doing the right things, as Peter Drucker used to emphasise. The latter requires judgement, vision, and often courage—qualities that cannot be programmed. Even the best software cannot deal with the unexpected or the unusual. We all have experienced the frustration of the computerised help line that has not anticipated our particular problem and sends us around in endless circles searching for an answer. Efficiency gets rid of choice wherever it can. Organisations tend to like that. And so, it seems, do we.

Already, Amazon and its ilk tell us what we would like to read, wear, eat, and watch. It is all too easy to go along with their suggestions. Many are familiar with the story of the store, Target, that was able to identify that a woman was pregnant based on the contents of her shopping basket, and then helpfully sent her suggestions for maternity wear. (This was fine, until they sent similar suggestions to a teenage girl whose father was unaware of her pregnancy.)

A world awash with data allows little privacy. Your mobile phone, even when turned off, can tell others where you are and whom you have been calling or texting. New television sets can record your conversation and send it away. Fibre optic cables underground can detect any movements without our knowledge.

When all our private habits can be observed, analysed, and dissected, we will have no secrets, even from ourselves. Who are we when others know us better than we do? The ever-present danger is the power that this gives to organizations, including the ones for whom we work. Is our world going to be out of our control, and who will control the controllers? That is the challenge faced by those who foresee a so-called singularity when computers start to think for themselves.

So where does this leave us? Rejoicing in the wonders of the infosphere and exploring its potential (I hope), using it while not becoming enslaved by it, and remembering our humanness, specialness, and all that cannot be reduced to data. We must remain the masters of our creations, not their puppets.

This post is one in a series of perspectives by presenters and participants in the 7th Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 5-6, 2015 in Vienna. The theme: Claiming Our Humanity — Managing in the Digital Age.

Make Your Team Less Hierarchical

The cargo door of an aircraft opens at 25,000 feet. The dark, freezing air rushes in and swirls around the Special Operations Forces (SOF) team that stands on the ramp of the aircraft, ready to jump. Their team leader stares into the darkness through his night vision goggles. He spots what he’s looking for, raises a hand, and then quickly points into the dark. Without hesitation, the team dives silently into the blackness.

Most of us have read about elite teams, seen them depicted in movies, or perhaps been fortunate enough to be part of one. Elite teams win the big games, save lives in emergency rooms, and fight in conflicts around the world. And there was a time when creating highly effective small teams was a sufficient way to set the conditions for success. In the military, for example, winning a war was a matter of scaling with efficiency while ensuring that every fighting unit was superior to the enemy unit it encountered.

The U.S. military built itself around the efficient hierarchy throughout the 20th century. Senior leaders identified how and where to deploy small units, and young leaders focused on leading the best small teams on the battlefield. The structure of the bureaucratic model was designed for efficiency and control — controlling the flow of information between verticals was the ultimate display of power. This leadership model worked especially well for the SOF community. There were complicated threats in the world, but they tended to exist in isolated pockets, so highly effective small teams were a sufficient solution.

But in the post-9/11 fight against Al Qaeda, SOF realized that the complexity of 21st-century problems wouldn’t be solved with a 20th-century approach. The speed of information flow and the interconnectedness of individuals had created an entirely new type of battlefield. Threats that could connect with each other in near real-time were forming networks able to outmaneuver the military’s more powerful, but much slower, bureaucratic model. The barrier to entry for an individual joining these networks was simply a cell phone or a YouTube account. Relying on the capabilities of elite small teams was now an insufficient approach.

You and Your Team

Leading Teams

Boost your group’s performance.

SOF’s critical first step was recognizing that our operating model needed to shift. Instead of leading a top-down, highly efficient bureaucracy, we began to lead ourselves as a network. Our mandate was to scale the effectiveness of small, elite teams onto the enterprise level. Instead of many individual leaders running many individual teams, we began to connect ourselves as a broad network of units (or a team of teams, as we liked to call ourselves).

We took the organizational blinders off and admitted that many of our assumptions about information sharing, leadership, and communication would need to change. Where once information was compartmentalized between small groups, now we pushed the boundaries of sharing as far as we possibly could. Where once units walled themselves off from one another, now our operations centers and ground units became a mix of intelligence civilians, special operators, and coalition partners. Where once our communications happened in a point-to-point fashion that mirrored our org chart, now our day began with a video teleconference where thousands from around the world would hear and share the latest information available. After several years of change, we could apply the force of a global enterprise with the speed and agility of a distributed network.

This is the model that any large organization will need in today’s world. A company used to be able to dominate the competition if it focused on creating an effective group of verticals. But in today’s world, leaders using the network model can quickly outpace those who remain focused on winning individual battles.

Importantly, SOF made this shift without touching a single org chart. It was a mental shift, a communication shift, and a leadership shift. It is up to today’s leaders to truly empower their organizations to think, act, and move as a network — it’s a mental shift that starts at the top.

To adopt the network model, your organization must take a few steps:

Create alignment. Does your team truly agree on the strategic vision of the organization? That wasn’t the case for us — and we were sitting in the middle of a combat zone, where you’d think the answer would be clear. Different teams can have competing visions for the organization, and work at cross-purposes as a result. Until you’re aligned, there’s no point in trying to solve more complex problems — because you won’t be doing so as a networked team of teams.

Drive inclusion and transparency. In a complex world, things move too fast for traditional systems, and challenges are often beyond the scope of just one functional team. The more people you can pull into real communication, the more perspectives and real-time insights you’ll have to attack problems with speed and accuracy.

Lead with empathy. Understanding the motivations and perspectives of those who follow you will make you a more effective leader. The era of top-down, “my way or the highway” leadership is over. Bottom-up, emergent intelligence will garner more creative ideas, and understanding the perspectives of those below you will help your network make better, more informed decisions.

Excellent but siloed small teams are no longer the panacea for all challenges. We must move to a world where all large institutions, from health care to our military apparatus to corporate enterprise, are as nimble and effective as an elite small team. Leading a team of teams is the approach that will win the day in the 21st century.

July 14, 2015

How Reddit the Business Lost Touch With Reddit the Culture

A community-driven business doesn’t have to run itself the way its community does, any more than an airline’s backoffice should be run by two people in a cockpit. But the business does need to be fluent in the values and dynamics of its community, just as the airline’s CEO needs to understand that passengers should be treated differently than freight. That helps explain why last week the users of Reddit.com, a popular message board, were up in arms.

Community-driven businesses should learn two important lessons from the Reddit rebellion. First, if there’s a significant difference between the culture and values of the business and the community, it will take more than a change in culture to fix it; it may require changes in the organization and core processes. Second, the Reddit turmoil should be understood first and foremost from the community’s perspective, not management’s. Because at Reddit the community is both customer and “product,” this requires much more than a blithe “The customer is always right” philosophy. Rather, management needs to align itself deeply with the customers’ culture.

Culture is at the heart of Reddit. It is often talked about as a community, but its scale—169M unique visitors a month—stretches that term. Rather, it’s helpful to think of it not just as a community but as a culture that springs from a set of values and a form of discourse. At its best it’s a remarkable and positive culture. At its worst, it is demeaning and even hateful, all too often suffering from an assumed boy-ism that can create discomfort, or worse, for women and those deemed cultural outsiders. Characterizing Reddit’s overall culture is difficult if only because each discussion board (“subreddit”) has its own flavor, but redditors’ pride in their community, and their identity as redditors, is undeniable.

The precipitating cause of the Reddit Rebellion is itself a strong indication that the event should be understood first in cultural terms. An immensely popular employee, Victoria Taylor, was dismissed; neither side is talking about why, although a common speculation was that Taylor objected to a rumored plan by Reddit’s management—what we’ll call “RedditCo”—to monetize the subreddit that Taylor facilitated.

This is where RedditCo’s management went very wrong. First, it failed to recognize the vital role Victoria played in the community, and the repercussions her dismissal would have on that community. Then, when moderators (“mods”) of many of the most popular subreddits shut down their sites to protest Victoria’s abrupt termination and subsequent lack of management communication, ex-interim CEO Ellen Pao took to mainstream media, rather than the platform she managed. Worse, she dismissed the community’s concerns:

“Ms. Pao says that the most virulent detractors on the site are a vocal minority, and that the vast majority of Reddit users are uninterested in what unfolded over the past 48 hours.

“Most of the community is made up of thoughtful people, and they can appreciate what we all do, even if we don’t always agree,” Ms. Pao said.

This angered the community even further, and not just because it seemed to imply that the protestors were not thoughtful. As users quickly pointed out, most of the site’s content (and indeed, the vast majority of community-driven websites) is created by that tiny percentage, and mods put in an enormous amount of volunteer labor to keep the subreddits appealing. It was exactly like dismissing a work stoppage by the most active editors of Wikipedia on the grounds that they’re just a tiny percentage of overall users. Without them, there is no Wikipedia.

When Pao eventually issued an apology, first under a smaller subreddit and eventually under the official communication channel, it was too little, too late. Pao’s behavior confirmed to the Reddit culture that she was not, in the phrase redditors sometimes use, “One of us! One of us!” (The phrase comes from the cult movie Freaks; redditors use it in a self-mocking way.) The alienation of management from its users was just about complete.

This was a fall of some great distance. At the birth of Reddit, there was a remarkable alignment of business and community. That alignment had been manifested in a few ways. First, management maintained as close to a pure Free Speech policy as the law allowed, signaling trust in its community. Management had already eroded that trust by recently shutting down some subreddits dedicated to hating and shaming. Second, Reddit traditionally has consulted with the community about business decisions, using subreddits as the mechanism for doing so. Third, Reddit has sponsored or participated in popular altruistic programs and has said it will share profits with charities chosen by its users. Fourth, Reddit initiated the 2013 online protests against SOPA/PIPA that led to major websites sites shutting down for a day in protest.

So how could this deep alignment fail so quickly?

A big part of the answer is that RedditCo only had one person in direct, visible, continuous contact with its community: Victoria. And Victoria could not have been better at it. Even though she was a paid employee of Reddit, she spoke and acted first and foremost like a member of the community. She was indeed “One of us! One of us!”

The problem is that Victoria was the only RedditCo employee who was so widely and consistently visible. When she was fired, it was One of Us—even, perhaps The Best of Us—who was not being appreciated. The community felt disrespected, insulted, alienated. The alignment was turning out to be at risk, if not revealed as having been illusory all along.

RedditCo seemed at first to view this through a management lens. Viewed that way, the community unrest is a PR problem, or an issue to be addressed through the usual business incentives, perhaps by starting to pay the mods who are wrangling the subreddits. It’s like any other product kerfuffle to be minimized, controlled, and out-waited.

If viewed through the lens of culture, different imperatives emerge. For example,the civic technologist Ethan Zuckerman has studied why global cultures tend to isolate themselves on the Net, even though they are all just one click away from each other. At a minimum, he concludes, cultures need what he calls bridge figures who not only speak both languages, but who can bring one culture to appreciate the values of the other. The same is true when the business and user cultures fall apart. Management needs bridge figures, and Reddit fired its best one. Because there are so few others, her presumedly involuntary departure was seen not just as a loss but as a betrayal, as if RedditCo thinks it needs no bridges.

This is a structural failing that RedditCo needs to address: it needs many more Victorias. It needs them as paid employees, and it also needs to let unpaid bridge figures emerge from the community, primarily by engaging in public with the mods.

It’s crucial that in all of RedditCo’s engagements with its community, from the CEO through its paid and community bridge figures, it needs to embrace the values and forms of discourse of the Reddit community. The new CEO, co-founder Steve Huffman, is off to a good start. The announcement of his appointment was done on Reddit, and Huffman immediately engaged in a long, open, and frank conversation with the community.

Reddit has been a success story because it has embodied the “Gettysburg Principles”: Internet companies do well when they are of, by, and for their users. We have more than a little confidence that Reddit will get back on track because its founders and workforce are inclined by character and values to operate their business under those principles. They are indeed “One of us!” The challenge will be for Reddit to resist the urge to treat its community purely as a product as it drives toward profitability.

Win Over Executives by Proving Customers Support Your Idea

Despite how much has been written about corporate innovation, it still presents a big challenge. On one hand, senior executives encourage employees to develop new products and services. On the other, they don’t want to throw money at concepts with limited market potential. So how can internal innovators create confidence in the viability of their ideas as they’re still evolving? One way is to get customers to help you make your case. Here’s an example:

A technology firm that wanted to spur innovation offered internal teams seed funding to develop potentially transformative products. One of the recipients, a mid-level manager, used the funding to create a business case and product prototypes. She shared these with a small group of existing customers. Although her work generated a great deal of enthusiasm among them, when she requested additional resources to expand her effort, executives told her that if she didn’t have a plan for fast double-digit revenue growth, they wouldn’t increase their investment. Cost pressures were too high to make long-term, risky bets, no matter their potential payoff. And obviously, at such an early stage of development, she couldn’t show significant profitability that soon. So, any continued work on the idea would have to be done within the manager’s own limited budget—most of which was already accounted for.

Given this type of feedback, most people would have wrung their hands and moved on. But this innovator was so confident in the strength of her product idea that she refused to let it go. Instead, she enlisted the help of her customers. Using what was left from her initial funding, she invited 50 existing and potential customers for a full day of on-site collaborative product development. She handpicked people to attend from big-name organizations that would be sure to pique the interest of her executive team. Once a dozen or so customers confirmed, she let word of the event trickle out internally. Soon, various executives within her company began asking whether they could drop by. In addition, they offered her a glitzy conference room and provided a videographer and photographer to capture the action.

On the day of the workshop, she began by laying out her product vision and how it could dramatically enhance the industry landscape. The rest of the day was devoted to facilitating small-group discussions about current solutions, additional functionality needs, and component priorities. Various executive sponsors dropped by and saw how excited customers were by the product’s potential. For the first time, an abstract idea became something much more tangible.

Following the event, the manager posted video clips to her company’s internal blog to highlight the success. Thousands of employees then became aware of her product concept. Perhaps more importantly, they saw images of smiling customers and heard their quotes of support.

The next week, the manager went back to the executive team to ask again for more money. This time, she got it – along with an invitation to brief them on her progress each month. The customers’ excitement had become contagious.

From our experience, this is not an isolated case. Internal innovators are often passionate about their ideas, but have trouble selling them to colleagues and bosses, especially in cash-constrained environments. Turning customers into allies can tip the scales and make the executive team, and the funding managers, pay attention. And of course, having customers on board early on, as partners in product development, helps increase the chances of achieving innovation goals anyway.

For managers seeking to engage their customers as innovation allies, here are a few steps to get started.

Define your targets. Consider the customers your company already does business with, and those it aspires to win over. Take note of the organizations that may be most interested in your idea and those that may have the greatest amount of credibility with executive decision makers at your firm. Focus on getting these people involved first.

Work your network. Collaborate with the account managers at your company to determine how to open up a dialogue with current customers. For new customers, solicit help from Sales and Marketing colleagues on how to make inroads.

Make your efforts visible. Give the people holding the purse strings at your company the opportunity to experience potential customers’ excitement about your idea. That doesn’t necessarily mean hosting events like the one described above; virtual experiences, testimonials, and video interviews can effectively relay customer sentiment too.

Innovators in established organizations need many allies to bring their ideas to life. Few are as powerful as customers when it comes to getting the sponsorship and resources necessary to be successful.

July 13, 2015

The Logic Behind Amazon’s Prime Day

Amazon has boldly anointed Wednesday, July 15 as Prime Day. Most holidays revolve around religion, historical events, or appreciation for someone special. So what’s Amazon Prime Day?

At root, it’s a self-interested homage to rock bottom prices and free expedited shipping. To celebrate its 20th anniversary, Amazon has pledged more deals than Black Friday, exclusively for Amazon Prime members – as well as complimentary 30-day trials of its Prime membership. Prime, which normally costs $99 annually, includes benefits such as free two-day shipping, same-day delivery in some areas, streaming video, streaming music, Kindle library, photo storage, and early access to sales.

So why do we care? We’re interested because Amazon doesn’t seem particularly concerned about earning profits. In FY14, for example, Amazon had an impressive $89 billion in revenues. However, operating income was $178 million (thus, a measly 0.2% operating margin) which resulted in a $241 million net loss. Partly because of Amazon’s longstanding lack of concern over profitability, consumers have faith that Amazon is going to roll out awesome deals on Wednesday.

Prime is the lynchpin of Amazon’s plan to rub out brick and mortar retailers. With “free” expedited shipping, the goal of Prime is unabashedly clear: make Amazon the first-choice retail product provider for consumers. One click assures home delivery in two days or less. The purchase loyalty engendered by this program is reflected in the big difference between Prime vs. non-Prime customer spending. In the fourth quarter of 2014, Consumer Intelligence Research Partners (CIRP) estimates Prime had 40 million members – with members spending on average $1,500 annually compared to an average of $625 spent by non-members. (Note: this 40 million member figure includes a significant number of consumers who took advantage of free holiday trials.)

The brilliance of Prime is in how the bundle of benefits is constructed. At its inception, Prime’s key benefit was unlimited two-day shipping. This promotional program was targeted at “Whale Buyers,” those who purchase a lot. For Whales, the calculation is straightforward: “Am I going to make enough purchases – and thus save on shipping costs – to justify the cost of Prime?” If the answer is “yes,” this cost savings justification makes Amazon top of mind for all purchases, including small items such as tweezers normally bought at CVS. And if Amazon loses money on shipping (i.e., cumulative shipping costs are greater than the $99 Prime price) for a particular member, the loss can be rationalized as a volume discount to a big-spending customer.

So why add such seemingly unrelated perks such as streaming video and music and photo storage to the Prime program? And what does the company hope to achieve with Amazon Prime Day? Quite simply, Prime has saturated the Whale Buyer market and is now hunting for smaller volume customers to fuel growth. With an increasingly large stable of benefits, potential members who can’t justify Prime on the grounds of shipping savings can now conclude, for instance, “Netflix costs $108 annually, so I’m already ahead of the game by purchasing Prime for streaming video before even considering the additional benefits.”

Indeed, the data confirms that Prime is moving beyond Whale Buyers and has begun to attract large numbers of lower volume customers. CIRP estimates that in the first quarter of 2015, Prime had 41 million members with members spending on average $1,100 annually vs. non-members’ spend of $700. Thus, more people are signing up for Prime, but the average member spend dropped by 27% compared to the previous quarter.

The downside of Prime – to Amazon’s stockholders, that is – lies in its pledge of unlimited shipping. The challenge of “unlimited” is that it attracts over-users. Consider Red Lobster’s 2003 Endless Crab promotion. Offering all-you-can-eat crab leg dinners for $20 – $25 (depending on market), determined diners ate and ate—and unfortunately for the seafood restaurant chain’s bottom line, they ate some more. After announcing disappointing financial results – drained by endless crab servings – the market value of Red Lobster’s then parent company, Darden Restaurants, dropped by $405 million in one day – one of the biggest stock routs in the company’s history.

Amazon could think creatively about minimizing the risks of its “unlimited” shipping offer. For instance, the current $99 program could allot, say, 15 free shipments a year, with any overages charged at a trivial $1 per shipment. If Amazon put a ceiling on the number of free shipments on its $99 Prime membership, it could then offer a $149 unlimited shipping option. These two options would allow Amazon to serve different volume customers – and the beauty is customers self-select which option works best for them based on their shipping needs. Forrester Research estimates Amazon loses $1 billion to $2 billion annually on Prime shipping costs. Given that this loss is up to 11 times as much as Amazon’s $178 million operating profit, small changes to Prime’s pricing can significantly improve Amazon’s financial well-being.

Remember the vicious discounting wars that occurred during the Internet bubble era? Amazon emerged a clear victor in that virtual retail grab. It’s time for brick and mortar retailers to be on the lookout. With an enhanced Prime program, focus on same day delivery, and now its own holiday, Amazon is clearly setting its sights on fully invading land-based retail territories.

A Refresher on Debt-to-Equity Ratio

When people hear “debt” they usually think of something to avoid — credit card bills and high interests rates, maybe even bankruptcy. But when you’re running a business, debt isn’t all bad. In fact, analysts and investors want companies to use debt smartly to fund their businesses.

That’s where the debt-to-equity ratio comes in. I talked with Joe Knight, author of the HBR TOOLS: Return on Investment and cofounder and owner of www.business-literacy.com, to learn more about this financial term and how it’s used by businesses, bankers, and investors.

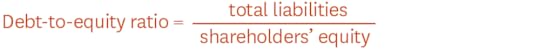

What is the debt-to-equity ratio?

“It’s a simple measure of how much debt you use to run your business,” explains Knight. The ratio tells you, for every dollar you have of equity, how much debt you have. It’s one of a set of ratios called “leverage ratios” that “let you see how —and how extensively—a company uses debt,” he says.

Don’t let the word “equity” throw you off. This ratio isn’t just used by publicly traded corporations. “Every company has a debt-to-equity ratio,” says Knight, and “any company that wants to borrow money or interact with investors should be paying attention to it.”

How is it calculated?

Figuring out your company’s debt-to-equity ratio is a straightforward calculation. You take your company’s total liabilities (what it owes others) and divide it by equity (this is the company’s book value or its assets minus its liabilities). Both of these numbers come from your company’s balance sheet. Here’s how the formula looks:

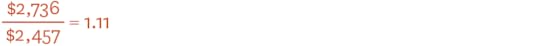

Consider an example. If your small business owes $2,736 to debtors and has $2,457 in shareholder equity, the debt-to-equity ratio is:

(Note that the ratio isn’t usually expressed as a percentage.)

So, of course the question is: Is 1.11 a “good” number? “Some ratios you want to be as high as possible, such as profit margins,” says Knight. “In those cases higher is always better.” But with debt-to-equity, you want it to be in a reasonable range.

In general, if your debt-to-equity ratio is too high, it’s a signal that your company may be in financial distress and unable to pay your debtors. But if it’s too low, it’s a sign that your company is over-relying on equity to finance your business, which can be costly and inefficient. A very low debt-to-equity ratio puts a company at risk for a leveraged buyout, warns Knight.

“Companies have two choices to fund their businesses,” explains Knight. “You can borrow money from lenders or get money from equity.” Interest rates on business loans tend to come with a 2-4% interest rate (at least at the moment), and that interest is deductible on your company’s tax returns, making it an attractive way to fund your business, especially when you compare it to the returns that an investor might expect when he or she buys your stock that shows up as equity on your balance sheet, which can be 10% or higher.

So you want to strike a balance that’s appropriate for your industry. Knight gives a few rules of thumb. Technology-based businesses and those that do a lot of R&D tend to have a ratio of 2 or below. Large manufacturing and stable publicly traded companies have ratios between 2 and 5. “Any higher than 5 or 6 and investors start to get nervous,” he explains. In banking and many financial-based businesses, it’s not uncommon to see a ratio of 10 or even 20, but that’s unique to those industries.

There are exceptions within industries as well. Take Apple or Google, both of which had been sitting on a large amount of cash and had virtually no debt. Their ratios are likely to be well below 1, which for some investors is not a good thing. That’s partly why, says Knight, Apple started to get rid of cash and pay out dividends to shareholders and added debt to its balance sheet in the last month or so.

How do companies use it?

The calculation is most often used by bankers or investors deciding whether to give your company money. It helps them understand how you’re paying for your business. They want to know, says Knight, “Does the company have the ability to develop revenue, profit, and cash flow to cover expenses?”

If the debt-to-equity ratio goes up, the perceived risk goes up. If you don’t make your interest payments, the bank or lender can force you into bankruptcy.

“Bankers, in particular, love the debt-to-equity ratio and use it in conjunction with other measures, like profitability and cash flow, to decide whether to lend you money,” explains Knight. “They know from experience what an appropriate ratio is for a company of a given size in a particular industry.” Bankers, Knight says, also keep and look at ratios for all the companies they do business with. They may even put covenants in loan documents that say the borrowing company can’t exceed a certain number.

The reality is that most managers likely don’t interact with this figure in their day-to-day business. But, says Knight, it’s helpful to know what your company’s ratio is and how it compares with your competitors. “It’s also a handy gauge of how senior management is going to feel about taking on more debt and and therefore whether you can propose a project that requires taking on more debt. A high ratio means they are likely to say no to raising more cash through borrowing,” he explains.

It’s also important for managers to know how their work impacts the debt-to-equity ratio. “There are lots of things managers do day in and day out that affect these ratios,” says Knight. How individuals manage accounts payable, cash flow, accounts receivable, and inventory — all of this has an effect on either part of the equation.

There’s one last situation where it can be helpful for an individual to look at a company’s debt-to-equity ratio, says Knight. “If you’re looking for a new job or employer, you should look at these ratios.” They will tell you how financially healthy a potential employer is, and therefore how long you might have a job.

What mistakes do people make when using the debt-to-equity ratio?

While there’s only one way to do the calculation — and it’s pretty straightforward— “there’s a lot of wiggle room in terms of what you include in each of the inputs,” says Knight. What people include in “liabilities” will differ. For example, he says, “some financiers take non-interest bearing debt such as accounts payable and accrued liabilities out of the liability number and others might look at short-term vs. long-term debt in comparison to equity.” So find out what exactly your company counts in its calculation.

Knight says that it’s common for smaller businesses to shy away from debt and therefore they tend to have very low debt-to-equity ratios. “Private businesses tend to have lower debt-to-equity because one of the first things the owner wants to do is get out of debt.” But that’s not always what investors want, Knight cautions. In fact, small—and large—business owners should be using debt because “it’s a more efficient way to grow the business.” Which brings us back to the notion of balance. Healthy companies use an appropriate mix of debt and equity to make their businesses tick.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers