Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1271

July 22, 2015

Case Study: Is a Promotion Worth Hiding Who You Are?

Andrew Nguyen/HBR STAFF

“I have some news,” David Lee told his team member Mark Brown. David was the president of the U.S. division of the Korean conglomerate Hanguk Industries, where Mark, a vice president of technology, reported to him.

“Good news?” Mark asked.

“That depends, I guess,” David said, looking a little tentative. “They want you for the Seoul job. You’ll be getting the official e-mail from HR soon.”

Hanguk was a large, fast-growing company with diversified interests spanning electronics, biotechnology, shipping, construction, and chemicals. Its most successful division, mobile telephony, was looking for a new head of software development at headquarters in Seoul. The division had just won a big contract with a major mobile operator in Qatar and needed to customize a smartphone system for the client’s Middle East–wide network in the next six months. Hanguk’s leadership would be watching the project closely, because expansion to the Arab world was one of its top strategic objectives. This was a dream job for Mark, and now, it seemed, he had it if he wanted it.

“That’s great news!” Mark said. “Isn’t it?” He was puzzled by the pensive look on David’s face. Of course it was natural for a boss to have mixed feelings about seeing a valued employee move on, but David was more than Mark’s manager: He was his mentor. He’d always pushed Mark to advance in his career, and this was an internal promotion, on a three-year contract, so they’d still be working for the same company. Mark might even return to San Francisco after his stint at HQ.

Editor’s note: This fictionalized case study will appear in a forthcoming issue of Harvard Business Review, along with commentary from experts and readers. If you’d like your comment to be considered for publication, please be sure to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.

“I know this creates a problem for you,” Mark said, “but there are a few people around here who could take my place.”

“I just want to be sure you’re making the right move,” David said carefully.

“If I were certain you were, I’d support you 100%. But I’m not sure Korea is the best place for you — professionally or personally. Besides, your role will involve spending a lot of time in the Middle East.”

Finally it dawned on Mark. “You mean because I’m gay,” he said flatly.

When Hanguk recruiters had come to Mark’s business school campus several years earlier, they’d assured him that the company was run very much like an American one: Everyone spoke English, foreigners were welcome, pay and promotions were merit-based, and employees were happy. The chairman, Jae Kyung Park, was often quoted as saying that he wanted Hanguk to be a symbol of progress in Korea, with best practices that matched those of its global competitors. Mark had certainly found all that to be true in the San Francisco office, which David ran with great independence.

Of course, he knew that the reality at headquarters was different. He’d seen it firsthand on the few trips he’d made there. In fact, David, a Korean-American who’d spent much of his youth in Seoul, put a lot of time into coaching his team on how to navigate the ins and outs of the chaebol’s culture and hierarchy. But Mark had never expected his sexual orientation to present a stumbling block in his career at the company.

“We’ve come a long way,” David said. “So has Korea as a country. But it’s not California. I really believe that Hanguk is committed to diversity and is firmly anti-discrimination. But I also know that when Americans go to HQ, they’re expected to fit in and play by the rules.” He paused. “And then there’s life outside the office. I have gay Korean-American friends here who won’t even go back to visit their relatives.” He hesitated before adding, “I worry that you won’t feel comfortable being yourself.”

“Are you saying that to do well in this job, I’ll have to pretend I’m straight?” Mark asked, as a flood of memories ran through his mind. Having grown up in suburban Columbus, Ohio, he knew well what a life of “pretending” meant.

“No, I’m not saying that,” David replied. “But you should know that Korean society is conservative — especially if your standard is San Francisco.”

We All Hide Parts of Ourselves

“Don’t go!” Kate Seward screamed over her noodles. “You can’t!”

“Calm down, Kate,” Mark said, smiling at his friend’s dramatics. They were out to dinner with another college friend, Jack Sheehan. Thick as thieves since freshman year, they’d all moved to San Francisco after graduation, and for more than a decade Pho Phy Quoc, in the Inner Sunset, had been their go-to meeting spot for catching up on one another’s lives.

“Jack, back me up,” Kate said.

“I don’t know why either of you is freaking out,” Jack said between slurps of soup. “You should go. They don’t need to know you’re gay.”

“Wait,” Kate said, holding up her hands in shock. “You’ve been out since you were 15 years old, Jack. And now you’re pushing Mark, in his thirties, back into the closet?”

“It’s not like we wear ‘I’m gay’ signs around our necks,” Jack replied. “I don’t introduce myself to coworkers with ‘Hi, I’m Jack. I like men.’ We all hide parts of ourselves at work. You’ve even told us you don’t mention your kids in meetings because you don’t want to get slotted into the mommy track.”

“But my colleagues still know I am a mom,” Kate said. She turned to Mark.

“How can you even consider taking a job that requires you to hide the fact that you’re gay? It would be like going back to high school in Ohio! If you can’t act in Seoul the same way you can in San Francisco, then you shouldn’t go.”

“No one has said that I definitely need to ‘hide’ who I am,” Mark replied.

“But it’s not reasonable to think that expectations in Korea, or the Middle East, would be the same as in San Francisco. And I’m not a vulnerable high school kid anymore. Besides, they really want me. The chairman sent me a personal e-mail last night encouraging me to accept.” Getting an individual note from Mr. Park was a big deal.

He continued, “The guy who would be my new boss, Ahn Moon, is flying out to meet with me on Monday. And this is a serious promotion. A huge step up in my career. More responsibility, more money, more industry exposure. I’ll have 25 developers reporting to me.”

“That’s not all that matters in life,” Kate said.

“Of course it’s not, but work is really important to me,” Mark replied.

“I’d be more worried about your love life,” Jack teased. He had just married his boyfriend of eight years, and Kate and her husband had been together for 12. Mark, by contrast, was still very much single.“It’s not like I’d miss the nightlife in the Castro,” Mark joked. “I’d be super busy with work. And on the off chance I did want to go out, Seoul has some gay-friendly neighborhoods. One’s called ‘Homo Hill,’ which my mom found on the internet yesterday.”

Everyone laughed. Neither of Mark’s parents had taken it well when their only child had announced in a letter home from college that he was gay, but his mother in particular had made a miraculous turnaround. She’d joined the Columbus PFLAG group and eventually became a mentor for other parents whose kids had just come out. She visited Mark every few months, so Kate and Jack knew her well.

“Oh, Carol,” Kate said fondly. “What does she think?”

“She said that she knows I’ll make a thoughtful decision —”

“— which you always do,” Kate interjected.

“But shockingly, she says that I should do it. True to her style, she’s been scouring the internet since I told her the news. She sent me some polling data suggesting that Korean society is improving when it comes to accepting gays. Apparently there is a Pew poll showing where major countries stand on gay issues. Korea wasn’t great — something like 40% say society should accept us — but it wasn’t abysmal either. As in most places, it seems to be a generational thing. Young Koreans see no problem with homosexuality; it’s the older generations that still struggle with the concept. She even forwarded clips of an openly gay TV personality.”

“It also helps that the contract is for only three years,” Mark added. “So according to her, I can do my time, come back to the U.S. office, find the man of my dreams, and, most important, give her some grandchildren.”

“Sounds perfect,” Jack said.

Mark nodded, but he knew that scenario was a long shot — on all fronts. He wasn’t sure he even wanted to get married or have kids. He was happy to focus on his career. Assuming that all went as forecast, the mobile telephony group would be busy with exciting, challenging work for at least the next five to seven years. And if he intended to climb even further at Hanguk, Seoul was the place to be.

Diversity and Inclusion

Mark stood and formally shook Ahn Moon’s hand, bowing slightly, as he’d learned to do with all his Korean colleagues.

“This is a very exciting time for Hanguk Industries,” Ahn said. “Chairman Park asked me to tell you how much he wants you to take this position. We know from David and others that you have the right skills, expertise, and creativity to manage this very important group. You are exactly the kind of leader we want. And as you know, we are keen to increase the representation of foreigners in all our businesses. We pride ourselves on being a multinational leadership team. It is the only way that we will succeed as a global company.”

Mark remained silent while Ahn continued. He knew he was expected to show deference to anyone more senior.

“You’ll be the first expat to lead one of our mobile software teams, but we’ve had other foreigners in the group. There was one in particular who did quite well — Mr. Ryan Porter. He was very much like you.” Ahn paused and looked Mark in the eye.

He knows, Mark thought, slightly shocked.

“He fit in very nicely. He understood a lot about Korean culture, and he did his best to act in a way that was comfortable for us Koreans.”

He did his best to stay in the closet, Mark thought.

“The cultural differences are difficult. That’s why the offer includes an increase in salary. ‘Hardship pay,’ I think they call it in English.”

Mark nodded, assuring Ahn that he’d gotten the phrase right.

“Of course,” Ahn continued, “as outlined in our Global Code of Conduct, we are committed to making every effort to create a working environment in which foreigners, women, even the disabled, are respected.”

Mark was confused. At first it had sounded like Ahn was telling him to keep quiet about his sexual orientation. Now he was talking about inclusivity. Which was it?

“We are all hoping you will accept the offer. We will make every effort to see that you’re comfortable, and I presume that you will make every effort to fit in. Yes? That could be our agreement.”

“I’m extremely honored to be considered,” Mark said. “I would greatly appreciate it if you would give me another day or two to think about it.”

“Yes, certainly,” Ahn said. “We do very much want you for this very important role. But,” he added pointedly, “I know it is not an easy decision to leave your home country.”

They again shook hands. Mark bowed, and Ahn left the office. Not five minutes later, David walked in. “So, did he give you the hard sell?”

“I’m not sure,” Mark said. “Did you tell him I’m gay?”

“Of course not,” David said sincerely, and Mark believed him.

“Well, he seemed to know; he hinted at it, in a bizarre sort of way.”

David shook his head but then quickly added, “I’m sure if you go to Seoul, you’ll find yourself learning lots of new things, and not just about work.”

“So you think I should do it?”

“Look, Mark, it’s up to you. I know you’d knock this out of the park. There’s no doubt it’d be good for Hanguk and for your career. Just know that if you say no, there will be other opportunities. I’m not going to be here forever.”

“But there’s no way they’d give me your job if I had no experience in Korea,” Mark said.

“Not necessarily,” David said. “The rules are changing.”

“So maybe other rules are changing too?”

“Maybe,” David said. But Mark could tell from his tone that he didn’t quite believe that.

Question: Should Mark take the offer?

Please remember to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and email address.

4 Strategies for Reaching the Chinese Consumer

Slowing Chinese economic growth coupled with confidence-sapping tumult on the stock market have set alarm bells ringing at companies about their future growth prospects in China. But they should not simply sit back and wait to see what happens next. Consumer-facing businesses have an important role to play as the Chinese government nudges its economy from an investment-led to a consumption-led model. China has many eager, experienced consumers – but companies need to remember that there are many more cautious ones waiting in the wings who will need to be coaxed into joining the consumer economy.

Government policy will, of course, be an important factor in releasing this latent demand. But while the power to initiate a transition to a consumption-led economy lies in government hands, what the government unleashes, companies can nurture.

Our research on China’s prospects, in comparison to the development trends of 167 countries over 60 years, highlights the magnitude of the opportunity. Economic growth of just under 5% a year would see consumer spending rise by 60% over the course of the next decade, even if consumption’s share of GDP doesn’t budge. But with the right mix of government policy and business action, consumer spending could rise by as much as 126%, the equivalent of an additional $15 trillion.

So what exactly can companies do to help push toward the higher number? There are four things.

First, as consumerism becomes more deeply entrenched, companies will need to segment more and more precisely, acting on the different needs and tastes of different income, regional, and age groups. Take transport. Audi has focused on the luxury car market, offering an extended-wheelbase version of its sedans to allow room for a chauffeur and back passenger, as many rich Chinese prefer to be driven rather than drive. Audi now sells more luxury cars than any other manufacturer in China. Meanwhile, agile Chinese manufacturers such as Geoby have taken the market for cheap transport by storm. A decade ago, there was no market at all for low-cost electric bikes. Today, an estimated 200 million Chinese people use them and the number is rising – and Geoby is heading to other markets with its products.

Second, they will need to extend modern trade channels and distribution networks to make sure it is not only consumers in today’s biggest cities that get access to new products, but those in more rural locations as well. E-commerce is helping to overcome this barrier. But China presents a unique set of challenges. How, for example, do you reach the millions of workers who, under China’s Hukou system, are still registered as living in villages but who have migrated to live and work in cities and so have no registered address there? In Brazil, Microsoft and Google helped overcome a similar problem in city slums, home to some 11 million people, many of whom own smart phones. With no official addresses, delivery of online purchases or local retail distribution near these people was almost impossible until the two companies entered into partnerships with local community groups to map these areas. This opened up the potential for delivery. The companies took the initiative to help find this solution.

Third, companies will need to communicate the benefits of unfamiliar products to Chinese consumers in order to build demand and loyalty. Property insurance is a good example. Despite growing personal wealth and a taste among the rich for expensive cars, jewelery and art, the penetration of property insurance in China remains very low. Between 2004 and 2011, only 1.4% of property losses due to natural catastrophe were insured, according to Lloyds. People are either unfamiliar with property insurance, or not convinced of its value.

Finally, companies will need to develop the financial services and products that typically underpin increases in consumer spending, and which remain relatively scarce in China. Innovative business models may be required. Take consumer credit. The absence of credit histories in a newly-consuming society stifles borrowing – a barrier that Sesame Credit Management Group, started by Alibaba founder Jack Ma, is overcoming by examining consumers’ online purchasing activity, including their record of paying utility and cell phone bills, in order to assess their creditworthiness.

All four actions, pursued energetically, will help determine the size of the Chinese consumer market in 2025. Company CEOs should take note that an economy, like nature, abhors a vacuum. Somebody will step in to fill the need. Those consumer-facing businesses that move quickly, but wisely, will enjoy an outsize share of what continues to be one of the greatest consumer spending expansions in history.

How to Design Work Projects for Maximum Learning

Skill development is clearly a major priority for companies and managers these days. Enrollment in learning programs has surged over the last few years to generate a global executive education market of over $70 billion a year. People are also being asked by their bosses or HR to attend conferences, read case studies, watch videos, and try their hand at simulations, all with the goal of picking up new ideas and techniques.

As valuable as these experiences can be, they’re all at least one step removed from practice. At some point, you have to stop listening to experts and start doing something real. That is why live business projects can be powerful vehicles for learning, especially when they aim for dramatic outcomes on a tight timeframe.

Consider, for instance, the talent development program at Ascom, a global telecommunications company. In addition to receiving traditional training, each participant designs and carries out a 100-day project that targets an important business challenge, such as increasing the firm’s footprint in the health care segment or developing new software to enhance mobile phones (these are real examples). While delivering millions of dollars in profits, these projects have helped develop a cadre of leaders who can inspire teams to achieve big goals. Managers learn how to articulate a business opportunity in ways that energize team members. They get better at devoting attention and providing support — without micromanaging. Because they often have to collaborate across units or functions to achieve their objectives, they become more skilled at leading without formal authority. And they learn how to make it safe to fail in small, fast ways to discover the best solutions.

Designing projects as learning tools is a fairly straightforward process. You’ll want to:

Select an area where improvement is a must. Leaders and team members alike should feel a need — and enthusiasm — for tackling the challenge. That will give urgency to the learning.

Tie goals to concrete results. The project team must commit to achieving a concrete goal that actually moves the needle on performance and learning. “Call on 50 customers who are prime targets for the product” won’t cut it, because even if people call on that many customers, they might not make any sales or learn how to sell more effectively. The goal is hollow — it can be accomplished without generating any gains for the organization or insights for team members. This sort of limited assignment is a disappointment for most ambitious employees.A better goal would be something like “Sell $100,000 worth of the new product.” Now the team is tasked with both identifying and carrying out the right activities to make the required sales. This may include calling on customers but also quickly assessing the strong and weak points of the current offering, testing different value propositions, targeting specific customer segments, adjusting the product, modifying marketing materials, and so on. Team members must push themselves to figure out the right solutions — in real circumstances, in real time.

Make it a stretch. The project goal must be a major step up from what is considered normal. If a goal is too easy to achieve, it will not prompt sufficient ingenuity and skills development. (If the goal can be achieved through business as usual, it will.) The aim here is to compel people to behave differently — to try new things and figure out how to get the needed results. Of course, a goal that is too ambitious will break the team’s spirit. The key is to strike the right balance between challenging and achievable.

Do it fast. When faced with an objective six or 12 months out, most people will delay working on it until it becomes more urgent. Instead of fighting this trait of human nature, set a tighter deadline. Projects that are completed in 100 days or so are ideal. This gives the team enough time to achieve something dramatic — but not so much that members will struggle to keep it top of mind. In addition, the urgency creates the conditions for rapid skill development. Team members must quickly learn about the issues at hand and find ways to work smarter.

Deliver a microcosm — not a “phase one.” Many organizations construct short-term projects by simply carving off the first few months of a multi-year implementation plan, and then the next few, and so on. These projects often focus on delivering outcomes related to data collection, data synthesis, development of recommendations — and when they’re diced up like that, it’s hard to apply early-days learning down the road. But a short-term project that delivers its own meaningful outcome right away — within a certain region, for example, or for a particular market or product group — allows the team to do something better in one context and then see how well it works in other settings. As it rolls out the solution each time, the team gains experience and confidence, and learns what works where and why. It becomes more and more adaptive.

Let’s look at an example that shows all these principles in action. A few years ago the Municipal Property Assessment Corporation (MPAC), the not-for-profit organization responsible for assessing and classifying more than five million properties in Ontario, Canada, needed to find better ways to manage its budget. Leadership also wanted to improve service delivered to property taxpayers and municipalities. They knew that achieving these aims would require some skill building in the work force. People would have to learn to move faster, for instance. They would also have to become better at understanding what customers and stakeholders need and how they work. And there was a general need to execute with more discipline using concrete goals, clear work plans, formal results tracking, and so on.

The company’s president convened a meeting of the executive management group to organize the improvement effort. Rather than design an overarching program that tried to address dozens of opportunities at once, the group opted to use a few short-term projects to make fast progress and generate new ways of working that could be rolled out across the organization. They zeroed in on two high-priority areas: land severances (changes in property size, property use, or both) and condominium assessments (calculating the value of a unit when the owner takes possession).

The severances team aimed to increase the number of land parcels processed per day by 50% in one field office in 100 days. The condo team set the goal of completing valuations within 30 days of occupancy for 10 high-rise condo projects in Toronto. It was taking an average of around 600 days to complete valuations.

Both teams exceeded their targets. The severances team increased parcels processed per day by 175%. The condo team completed the 10 valuations in 27 days. On both, people worked smarter, not harder. They learned how to set clearer goals, engage senior executives, mobilize resources, and lead through influence (which is especially important in a public sector environment like MPAC’s). They also found better ways to work with stakeholders outside the organization.

Drawing confidence from these successes, MPAC launched additional projects in the same two areas to rapidly expand the proven innovations into other geographies. Then they launched projects in other business areas. Now, several years later, these kinds of projects are a core element of the organization’s performance improvement program. They have been used to drive progress on a wide variety of opportunities including product development, software release, organizational restructuring, and succession planning. And each project typically includes both a team performance goal and individual development objectives.

Accelerating the development of management skills and delivering bottom-line gains to the organization at the same time is a “twofer” every leader can embrace. And live business projects provide both benefits. When forced to deliver an important outcome on a tight schedule, people can’t help learning and growing. They find that they can do more they’d thought, and that keeps them reaching.

The More Experience You Have, the Worse You Are at Bootstrapping

If a company wants to generate the most revenue from its resources, it should put its most experienced leaders in charge of those resources. Sounds logical, right? After all, who else would best know how to use them? But a new study on Hollywood producers in the Strategic Management Journal reminds us that it’s not that simple.

Academics have been writing about the Resource-Based View (RBV) — a theory of how companies can gain competitive advantage from their unique and valuable resources — since the 1980s, though the idea has been around for longer. The researchers behind this new study point out that recent work on RBV has focused on managers as the ones generating the revenue from the company’s resources. What they wanted to explore is how managers do that.

The study investigated the interplay between a manager’s experience level and the type of resource the manager oversees. The researchers looked at three types of resources — financial, brand, and human — and specifically at the role of “fungibility,” which is a resource’s ability to be deployed in different ways. (Think of it this way: Cash, which can be spent in whichever way you choose, is highly fungible; people, whose specialized skills limit your options for deploying them, are less fungible.) For their data, the researchers turned to the movie business, where all three types of resources are at work on every project.

Studying 837 mass-market movies released between 1996 and 2003, they collected data on the movies’ producers and their prior experience. All the movies were released by a major Hollywood studio and played on at least 1,000 screens in the U.S. Most of the movies had multiple producers: 92% had between one and three, and the rest had as many as seven. Each producer’s experience was measured by how many movies he or she had produced prior to the current movie. When a movie had multiple producers, their experience levels were used together. (The researchers also tested their results against the experience level of each movie’s most experienced producer alone, but the results were not significantly different.)

Next, the researchers analyzed the three types of resources across all 837 movies. For the financial resources, they used each movie’s production budget. For the brand resources, they used whether the movie is a sequel, reasoning that sequels and series can offer the same advantages as a brand. For the human resources, they used each movie’s director, assessing the director’s talent by whether he or she had ever been nominated for a professional award by the Director’s Guild of America.

Finally, a movie’s performance was judged by its U.S. box office revenue. The researchers controlled for several factors that could influence a movie’s performance, including its rating, the timing of its release, and whether its actors were stars.

Using regression analysis, the study found that experienced producers outperformed less-experienced producers when working with higher budgets and stronger brands — but got worse results when working with talented directors. Experienced producers only got better results when working with less-talented directors. In addition, less-experienced producers outperformed experienced producers when working with lower budgets and weaker brands.

The researchers concluded that fungibility plays an important role in whether top managers deploy resources successfully. As they gain experience, managers become more skilled at using resources in different ways, as well as at recognizing opportunities to use them. But when a resource is less fungible, like a company’s specialized top talent, experienced managers can struggle to deploy it, and even end up destroying value in the process.

The best strategy, the researchers say, is for leaders to adapt their approach to the specifics of the project. When working with top talent, it’s best to take a hands-off approach: offer general support, but otherwise let them do their jobs. When working with less-experienced talent, a manager being more actively involved will get better results. And when the resources aren’t people, the most experienced leaders will get the best possible results.

But the amount of resources matters too. The study also found that experienced managers struggle to create value with fewer resources, possibly because after honing their methods on projects with plentiful resources, they have a hard time adapting to meager circumstances. In these cases, less-experienced managers, who tend to be better at finding ways to wring value from fewer resources, are the best choice to lead the project.

So the next time your company has a resource-based project that needs a leader, remember: depending on the project, your most experienced people might not be the best people for the job.

A Quick Guide to Avoiding Common Writing Errors

You’re looking at an e-mail you just wrote, and you’re not sure whether you have the right word: Do you want affect or effect? Further or farther? Gray or grey? Getting it wrong can make you look bad — people do judge you by the way you write — but you also don’t have all day to look up words. It helps to have an easy reference for the basics, bookmark some resources, and learn how to choose your battles.

COMMON QUESTIONS

To save you keystrokes, here’s the run-down on some of the most common problem words:

Affect/Effect: Most of the time affect is a verb and effect is a noun. It affected him. The effect was startling.

All Right/Alright: Although alright is gaining ground, the correct choice is still all right.

A Lot: A lot is two words, not one. Allot means “to parcel out.”

Between You and I: Nope. Between you and me is the correct phrase.

Complement/Compliment: Things that work well together complement each other. Compliments are a form of praise.

Farther/Further: Farther is for physical distance; further is for metaphorical distance or when you mean “moreover.” How much farther? Further, your whining is annoying.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Better Business Writing

Communication Book

Bryan A. Garner

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Gray/Grey: Gray is the American spelling. Grey is the British spelling.

Irregardless: Never use this word. The correct choice is regardless.

Lay/Lie: Subjects lie down; objects are laid down. He should lie down for a moment. Lay the reports on the table. (Verb tenses are a bit tricky for this pair. Here’s a chart that will help.)

Myself: Send the e-mail to Bob and myself is a hypercorrection — when people try so hard to get something right that they actually get it wrong. The correct form is: Please send it to Bob and me.

RESOURCES

When you have questions beyond the basics, try some of my favorite resources for finding quick answers.

Google Ngram Search. The Google Books Ngram Viewer shows you how often words and phrases appear in books that Google has scanned. It’s a particularly good place to search — better than Google in general — if you’re looking for the correct idiom or phrase. That’s because books tend to be edited, which means they are more likely to conform to Standard English than the average blog post or web page. A general Google search may leave you confused, but a Google Ngram search will quickly show you that the correct phrase is bated breath instead of baited breath and that you want to say your beliefs are deep seated, not deep seeded. It’s also fascinating to play around with this tool to see how word use has changed over time.

American Heritage Usage Notes. Most major dictionaries are online. I use Dictionary.com and Merriam-Webster.com almost every day, and you should too. But The American Heritage Dictionary has an especially nice extra feature that can help you answer tricky questions: usage notes. For years, this dictionary has surveyed a usage panel of experts to gather opinions about areas of language that are changing, and certain dictionary entries include explanatory notes based on the survey results. For example, the dictionary explains that using contact as a verb used to be frowned upon but is now accepted by 94% of the usage panel. If you do a general search about a word and find conflicting advice, the American Heritage usage notes will often explain why people disagree.

Style Guides: AP or Chicago. Whereas dictionaries aim to give broad advice about how words are used in real life, without making judgements about right and wrong, style guides say, “This is our style. Do it this way.” The AP Stylebook (followed by Associated Press writers and many magazine, newspaper, and public relations writers) and the Chicago Manual of Style (followed by most people in the book publishing industry) are both available online for a fee, and that makes them searchable. If you pick one and subscribe, it will help you follow a consistent style, and you will be able to search and quickly find the answers to most of your writing questions.

When Time Is Tight, Rewrite. There’s no shame in rewriting a sentence if you aren’t sure about a word or format. Sometimes being unsure is even a sign that your sentence could be improved. For example, it’s more specific to say that storms hurt first quarter sales than to say they affected sales, and if you think you might need a semicolon, your readers will probably thank you if you split the long sentence into two or three shorter sentences.

July 21, 2015

The Research We’ve Ignored About Happiness at Work

Recently, we found ourselves in motivational seminars at our respective places of employment. Both events preached the gospel of happiness. In one, a speaker explained that happiness could make you healthier, kinder, more productive, and even more likely to get promoted.

The other seminar involved mandatory dancing of the wilder kind. It was supposed to fill our bodies with joy. It also prompted one of us to sneak out and take refuge in the nearest bathroom.

Ever since a group of scientists switched the lights on and off at the Hawthorne factory in the mid-1920s, scholars and executives alike have been obsessed with increasing their employees’ productivity. In particular, happiness as a way to boost productivity seems to have gained increased traction in corporate circles as of late. Firms spend money on happiness coaches, team-building exercises, gameplays, funsultants, and Chief Happiness Officers (yes, you’ll find one of those at Google). These activities and titles may appear jovial, or even bizarre, but companies are taking them extremely seriously. Should they?

When you look closely at the research — which we did after the dancing incident — it’s actually not clear that encouraging happiness at work is always a good idea. Sure, there is evidence to suggest that happy employees are less likely to leave, more likely to satisfy customers, are safer, and more likely to engage in citizenship behavior. However, we also discovered alternate findings, which indicates that some of the taken-for-granted wisdoms about what happiness can achieve in the workplace are mere myths.

To start, we don’t really know what happiness is, or how to measure it. Measuring happiness is about as easy as taking the temperature of the soul or determining the exact color of love. As Darrin M. McMahon shows in his illuminating study Happiness: A History, ever since the 6th Century B.C., when Croseus is said to have quipped “No one who lives is happy,” we have seen this slippery concept being a proxy for all sorts of other concepts, from pleasure and joy to plenitude and contentment. Being happy in the moment, Samuel Johnson said, could be achieved only when drunk. For Jean-Jacques Rousseau, happiness was to lie in a boat, drifting aimlessly, feeling like a God (not exactly the picture of productivity). There are other definitions of happiness, too, but they are neither less nor more plausible but those of Rousseau or Johnson.

And just because we have more advanced technology today doesn’t mean we’re any closer to pinning down a definition, as Will Davies reminds us in his new book The Happiness Industry. He concludes that even as we have developed more advanced techniques for measuring emotions and predicting behaviors, we have also adopted increasingly simplified notions of what it means to be human, let alone what it means to pursue happiness. A brain scan that lights up may seem like it’s telling us something concrete about an elusive emotion, for example, when it actually isn’t.

Happiness doesn’t necessarily lead to increased productivity. A stream of research shows some contradictory results about the relationship between happiness — which is often defined as “job satisfaction” — and productivity. One study on British supermarkets even suggests there might be a negative correlation between job satisfaction and corporate productivity: The more miserable the employees were, the better the profits. Sure, other studies have pointed in the opposite direction, saying that there is a link between feeling content with work and being productive. But even these studies, when considered as a whole, demonstrates a relatively weak correlation.

Happiness can be exhausting. The pursuit of happiness may not be wholly effective, but it doesn’t really hurt, right? Wrong. Ever since the 18th century, people have been pointing out that the demand to be happy brings with it a heavy burden, a responsibility that can never be perfectly fulfilled. Focusing on happiness can actually make us feel less happy.

A psychological experiment recently demonstrated this. The researchers asked their subjects to watch a film that would usually make them happy — a figure skater winning a medal. But before watching the film, half of the group was asked to read out a statement about the importance of happiness in life. The other half did not. The researchers were surprised to find that those who had read the statement about the importance of happiness actually were less happy after watching the film. Essentially, when happiness becomes a duty, it can make people feel worse if they fail to accomplish it.

This is particularly problematic at the present era, where happiness is preached as a moral obligation. As the French philosopher Pascal Bruckner put it: “Unhappiness is not only unhappiness; it is, worse yet, a failure to be happy.”

It won’t necessarily get you through the work day. If you have worked in a front-line customer service job, like a call center or fast food restaurant, you know that being upbeat is not an option. It’s compulsory. And as tiring as this may be, it makes some sense when you’re in front of customers.

But today, many non-customer facing employees are also asked to be upbeat. This could have some unforeseen consequences. One study found that people who were in a good mood were worse at picking out acts of deception than those who were in a bad mood. Another piece of research found that people who were angry during a negotiation achieve better outcomes than people who are happy. This suggests that being happy all the time may not be good for all aspects of our work, or jobs that rely heavily on certain abilities. In fact, for some things, happiness can actually make us perform worse.

Happiness could damage your relationship with your boss. If we believe that work is where we will find happiness, we might, in some cases, start to mistake our boss for a surrogate spouse or parent. In her study of a media company, Susanne Ekmann found that those who expected work to make them happy would often become emotionally needy. They wanted their managers to provide them with a steady stream of recognition and emotional reassurance. And when not receiving the expected emotional response (which was often), these employees felt neglected and started overreacting. Even minor setbacks were interpreted as clear evidence of rejection by their bosses. So in many ways, expecting a boss to bring happiness makes us emotionally vulnerable.

It could also hurt your relationship with friends and family. In her book Cold Intimacies Eva Illouz noticed a strange side effect of people trying to live more emotionally at work: They started to treat their private lives like work tasks. The people she spoke with saw their personal lives as things needed to be carefully administered using a range of tools and techniques they had learned from corporate life. As a result, their home lives became increasingly cold and calculating. It was no wonder, then, that many of the people she spoke with preferred to spend time at work rather than at home.

It could make losing your job that much more devastating. If we expect the workplace to provide happiness and meaning in our life, we become dangerously dependent on it. When studying professionals, Richard Sennett noticed that people who saw their employer as an important source of personal meaning were those who became most devastated if they were fired. When these people lost their jobs, they were not just loosing an income – they were loosing the promise of happiness. This suggests that, when we see our work as a great source of happiness, we make ourselves emotionally vulnerable during periods of change. In an era of constant corporate restructuring, this can be dangerous.

Happiness could make you selfish. Being happy makes you a better person, right? Not so, according to an interesting piece of research. Participants were given lottery tickets, and then given a choice about how many tickets they wanted to give to others and how many they wished to keep for themselves. Those who were in a good mood ended up keeping more tickets for themselves. This suggests that, at least in some settings, being happy does not necessarily mean we will be generous. In fact, the opposite could be true.

It could also make you lonely. In one experiment, psychologists asked a number of people to keep a detailed diary for two weeks. What they found at the end of the study was that those who greatly valued happiness also felt lonelier. It seems that focusing too much on the pursuit of happiness can make us feel more disconnected from other people.

So why, contrary to all of this evidence, do we continue to hold on to the belief that happiness can improve a workplace? The answer, according to one study, comes down to aesthetics and ideology. Happiness is a convenient idea that looks good on paper (the aesthetic part). But it’s also an idea that helps us shy away from more serious issues at work, such as conflicts and workplace politics (the ideological part).

When we assume that happy workers are better workers, we can sweep more uncomfortable questions under the carpet, especially since happiness is often seen as a choice. It becomes a convenient way of dealing with negative attitudes, party poopers, miserable bastards, and other unwanted characters in corporate life. Invoking happiness, in all its ambiguity, is an excellent way of getting away with controversial decisions, such as letting people go. As Barbara Ehrenreich points out in her book Bright-Sided, positive messages about happiness have proved particularly popular in times of crisis and mass layoffs.

Given all these potential problems, we think there is a strong case for rethinking our expectation that work should always make us happy. It can be exhausting, make us overreact, drain our personal life of meaning, increase our vulnerability, make us more gullible, selfish and lonely. Most striking is that consciously pursuing happiness can actually drain the sense of joy we usually get from the really good things we experience.

In reality, work — like all other aspects of life — is likely to make us feel a wide range of emotions. If your job feels depressing and meaningless, it might be because it is depressing and meaningless. Pretending otherwise can just make it worse. Happiness, of course, is a great thing to experience, but nothing that can be willed into existence. And maybe the less we seek to actively pursue happiness through our jobs, the more likely we will be to actually experience a sense of joy in them — a joy which is spontaneous and pleasurable, and not constructed and oppressive. But most importantly, we will be better equipped to cope with work in a sober manner. To see it for what it is. And not as we — whether executives, employees, or dancing motivational seminar leaders — pretend that it is.

How a Cartoon Caption Contest Can Make You a Better Writer

On the first day of my undergraduate marketing strategy course, I show my students one of my favorite New Yorker cartoons. It is an image of a familiar red-and-white-shirted man with matching cap and wooden cane. He sits at a bar. The caption states, “Nobody ever asks ‘How’s Waldo?’” It’s sharp. It mixes familiar and clever. It’s classic New Yorker humor.

While a good number of my students chuckle to themselves, few if any are regular readers of the New Yorker. Many have not even heard of the magazine, let alone its famous caption contest. But I’d like to think unfamiliarity is par for the course, as even fewer of them expect a weekly humor competition to be a graded portion of their capstone marketing class.

Each Monday of the semester, I send that week’s New Yorker caption contest to my students, who have until Friday at 5 PM to come up with their own submission. When all the entries are in, I send them to a team of friends who work in comedy full- or part-time, asking them to pick the top four. I then take those four back to the class to have the students choose their favorite. When done well, the exercise drives a lively class discussion on language and meaning, and generates a wealth of implications for future marketing professionals.

You and Your Team

Business Writing

Don’t let poorly-crafted communications hold you back.

The idea first came to me when I read a post on the New Yorker blog by Cody Walker, a University of Michigan creative writing professor and New Yorker caption contest winner. Walker started his own contest a number of years ago with a group of his students at the University of Washington. As a creative writing professor, Cody’s goal is to fix the broken assumptions of the inexperienced writer. He suggests that “inexperienced writers sometimes imagine that good writing comes from good ideas. But that’s not right: good writing comes from good sentences.”

I would frame my goal a bit differently. One thing I have learned through the discipline of writing is how rarely I can assess the quality of my ideas (or lack thereof) until I write them down. For marketers, it is easy to rest in abstractions. Making general statements like “I think we can connect to Millennials with authentic branding” is a whole lot easier than writing a pitch that achieves the goal. This work of moving from general idea to powerful copy at some point requires the discipline of pen hitting the page, then revising what’s there—again, and again, and again. And I would argue the same clarity of thinking is required outside marketing too, for the entrepreneur or corporate executive designing a new strategy, for example. We need good ideas in business, and an important part of producing them is learning how to expose flaws in our thinking.

In the fall of 2014, one of our judges, Matt Sterenberg, was picked as a finalist for the real New Yorker caption contest. His entry catered to an image of two fish swimming in the sea—one as a set of bones and one in more full-bodied form. Matt’s caption read, “The relationship was less symbiotic than I’d hoped.” He ended up second in the public vote. His selection and overall finish created a lively debate among our judges and students on what worked or failed to work about Matt’s caption versus that of the public winner: “He only wanted me for my body.” Was Matt’s too obscure, too intellectual? Could he have framed his joke in a way that was more accessible? It is these kinds of discussions that help us better understand and work through the power and flexibility of language.

This playfulness with words is at the core of combining disparate thoughts, of standing ideas on their head, and it has a great deal to do with the right-brain/left-brain integration required in a business vocation. In my experience, business students and leaders too often rely on a style of thinking that seems cut-and-pasted from some first-year MBA case or bland management theory, or that’s generated creatively but without a corresponding rigor of thought. To the extent that we think in words, cultivating the discipline of writing is one practice toward clear and creative thinking. This is true whether we work in writing or business, live in for-profit or nonprofit worlds, make our home on Wall Street or Main Street.

While asking a busy business executive to flesh out a creative long-form article or book chapter is a bit unrealistic, a weekly discipline of submitting for a caption contest is a move in the same direction. Returning every week to the journey from an image to an idea to a punchy joke is a great way to train playful and disciplined thinking, and it has value whether done individually, within a classroom, or across a larger organization. In this way, I find the caption contest to be a helpful pedagogy in the most unlikely of places. And if, in the end, what results is merely a future of business with a splash of New Yorker humor, then I would venture we still all come out ahead.

3D Printing Is Changing the Way We Think

Surveys indicate that more than 30 percent of the top 300 largest global brands are now using or evaluating 3D printing (often with printing technology in-house) whether for prototyping and other innovation projects or in actual production of what they sell. Over 200 universities and colleges already offer 3D coursework in their curricula – covering aspects of not only 3D printing but also 3D scanning and design. To my mind, there is no question that 3D has reached, as Dartmouth’s Richard D’Aveni argues in a recent HBR article, a tipping point.

Even Terry Wohlers, founder of Wohlers Associates and publisher of the most cited research tracking the rise of 3D technology, is impressed. In a recent email exchange he told me: “We’re seeing a level of investment in 3D printing that we have not seen in the past — not even close.” As much of a champion as Wohlers is for the technology, he marvels at how the pace is picking up: “It’s really very interesting, and to some extent, mind-boggling, especially given that 3D printing has been around for more than 25 years.”

But perhaps there is a simple reason that the tipping point is arriving now. I think it’s connected to the recent arrival of very affordable desktop 3D printers – which means it isn’t only big corporate R&D departments that are coming down the 3D learning curve.

I saw this last year, when I spent eight-plus months traveling to hotbeds of 3D innovation across America in a specially outfitted RV. Our tour took us to government agencies like NASA and big corporations like GE, but we also hung out in makerspaces, hackerspaces, and other places where creators were using less elaborate versions of the tools.

I met, for example, Jeff Tiedeken, founder of the uniquely named business Monkey Likes Shiny. He is a skilled metal fabricator, but that label doesn’t do him justice. Really, he is a renaissance man creating models that quickly move from digital to physical, in the form of metal and also many other materials. He uses 3D printers – and also CNC routers, metal bending machines, waterjet cutters, and other tools. That day, for example, he was happy to show me the gravity bikes he designed for maximum speed on downhill coasts. Wild cycles, for sure. He regularly volunteers at the San Francisco Exploratorium because he wants to help young people learn to make things with their own hands – especially things designed from scratch. When I contacted him last, he was in Hawaii helping community-college students machine up parts for a satellite.

People like Jeff and students all around the world are embracing newly accessible technology to make the things they couldn’t make as easily before. For evidence, just look at the popular crowdfunding site Kickstarter. Over the past couple of years, entrepreneurs have used it to launch no fewer than 300 3D-printer-related campaigns – and many of them have funded at levels in the millions of dollars. This must be what it felt like in the earliest days of the automobile when, depending on which source you check, something like 1,800-2,800 auto “startups” were launched in the span of a few decades.

And in fact, it’s also like the most recent days of the automobile era. The “Uber of 3D printers” is 3D Hubs, a platform that allows designers, once they have created 3D software files, to find 3D printer owners in their locales who can, for an agreed fee, print them out of the desired materials. Already, nearly 20,000 printers have registered with the site globally – most of them individuals who bought their machines for personal use but are not running them at anywhere near their full capacity. That network footprint, 3D Hub reports, means that one billion people on this planet already have a 3D printer within 10 miles of their homes.

My point is not that all these artisans and hobbyists and their shop-scale technology are collectively producing enough 3D-printed output to put a dent in the overall economy. For me, the most important “tipping point” isn’t about how many manufacturers have changed, it’s about how many minds have. Thanks to more accessible technology, we are now reaching a critical mass of people who, when they think about how things are made, think in a different way. You could say they are thinking in 3D.

It is simply a different world when the time lapse between creating a design and having a tangible object of that design in hand is tiny. One inventor I know says that with traditional CAD tools, he would spend 15-16 hours to build a new model, but with web-based tools he has cut that down to only 15-20 minutes. Once you begin to assume that your iterations will be so quick, many aspects of how you think about developing and delivering products change.

In the California leg of the 3DRV roadtrip, I talked with Jason Lopes of Legacy Effects, best known for its ingenious contributions to The Avengers, Avatar, and other Hollywood films requiring special effects, animatronics, and creature designs. It was Jason who first helped me see how having a new level of access to a technology can lead to different ways of thinking. The company has always relied on service bureaus with very high-end equipment to render its character designs, but a few years ago, it purchased a 3D printer to use for simple tasks in-house. Unexpectedly, that ended up changing a lot about its design project workflows. At the same time, having 3D printing technology right at hand opened people’s minds to possibilities for using it beyond the modeling of the characters themselves – for example, to print the parts, jigs, and fixtures also needed to complete work and deliver it to clients. Jason says that having a 3D printer in the office has changed the way he and his colleagues approach design overall.

The same can be said about the 3D software tools that are becoming widely available. As just one example, apps now exist to allow smartphone users to snap some pictures of an object and get a digital 3D rendering of it. That means, of course, that you can print a scale model of something – like an action figure of yourself, for example. But more importantly, if some approximation of an object you wish to create already exists, you now have a starting point for it rather than beginning with a blank screen. Beyond being a timesaver, that might spell the difference between pursuing your novel idea or never getting around to it.

3D technology has a special ability to capture people’s imaginations. In Florida, we connected with 350 seventh-graders at the Electa Lee Middle School in Bradenton, where educator Bekka Stasny invited us to demonstrate the process. My 11 year-old son was the natural spokesman for this stop, showing off simple toys he had created en route with an app and printer we had on board the 3DRV. You would not guess that 350 middle school students could watch and listen with such rapt attention.

It might not always occur to us that this is true, but the people who work as operations management executives in large manufacturing concerns are also people with outside lives, who take interest in new trends and who have hobbies and side projects suited to their skills. Some of the people going to work in today’s big businesses are young people who were not long ago learning about 3D in classrooms and science museums. Some aren’t so young but have kids doing that. Some are “makers” or even casual entrepreneurs, earning extra cash selling 3D printer access to their neighbors. The more people like this who arrive in a workplace, the more likely that workplace will be to undergo a change. This is how tipping points are reached: not when some key percentage of big companies has installed a technology, but when enough people see its possibilities. Expect to see global manufacturing transformed as more people see new ways to make things, because they’re thinking in 3D.

July 20, 2015

Using Social Media Without Jeopardizing Your Career

Effective business communicators know that a brisk, bulleted memo is often more effective than a multi-page document, that an executive summary is at least as important as a full report, and that a PowerPoint deck driven by a few key images and bullets works a lot better than a deck that contains a word-for-word transcript of your presentation. We all know that less is more.

Yet even those who have mastered the art of brevity in traditional business communication may have a tough time mastering online communication. Whether it’s email, chat, or a social network, word count isn’t just a matter of style—it’s often a technical requirement. Add to that the expectation that your online voice should sound conversational, engaging, or even funny, and communicating online may be the biggest (and certainly most frequently encountered) writing challenge that we face in business today. Here are some guidelines that can help make those messages productive and satisfying—rather than a liability.

Relax. The biggest difference between online writing and traditional business communications is that most online interaction is a lot less formal—especially social network updates and text messages. If you write tweets that sound like traditional news release headlines, you’ll come off as boring, stuffy, or pompous. So lighten up, and try to write in a conversational tone. It helps to actually read your messages out loud, or to dictate them into your phone in the process of posting.

But don’t relax too much. While most professionals are more likely to err on the side of formality when it comes to their online presence, some folks go too far the other way. It is fine to be silly or profane in your Facebook feed, particularly if you only friend people you know well or limit your Facebook updates to a limited list of people. But on any network where you’re posting to a broader audience, aim for a level of professionalism that’s equivalent to the way you’d speak with a group of trusted colleagues: relaxed but respectful. That doesn’t mean you can’t swear on Twitter (I do myself, though not routinely), but that’s probably something you should only do if you’re the kind of person who sometimes swears in meetings (guilty as charged).

Calibrate your voice to your platform. You approach a meeting with your immediate team differently from a talk to a 500-person audience. In the same vein, you need to calibrate your voice to different kinds of online platforms and audiences. A businesslike tone may be appropriate on LinkedIn, but it may seem out of place on Facebook or an online chat. Spend some time reading and listening to any new network you join before you jump in, so you get a feel for the tone that’s appropriate—and pay particular attention to the tone used by the people you admire, or who seem to get a positive response to their posts.

Embrace humor…cautiously. Particularly if you’re trying to build any kind of following on a social network, humor has a place in your online business writing. Your best bet is gentle self-deprecation (but nowhere near the uncomfortable line of self-loathing), good-natured cracks about broad topics like sports, parenting, or the weather (or even politics, if you don’t need to worry about alienating people with different views), or funny Internet memes (as long as they’re not offensive). If in doubt, don’t post it, forward it, or share it. (I think I need that engraved on my keyboard.)

Easy on the acronyms. Acronyms and abbreviations are extremely common online, particularly on Twitter, where the 140-character limit means you’ll often see terms like HT (hat tip, to acknowledge a source), MT (modified tweet) or FTW (“for the win!”, a celebratory term). This kind of shorthand has its place, but use too many LOLs and OMGs, and you sound like a teenager.

Be nicer online than you are offline. Aim for online communication that makes you sound about 30% nicer than you actually are. Why? Because we’re notoriously bad at judging how what we write—or rather, what we intend to write—will sound to the person reading it (and they’ll probably assume it’s worse than you intended). A good rule of thumb is to read anything you write out loud before you post or send it, particularly if it’s a challenging or controversial communication (ideally, you’ll set those aside for 24 hours, show them to another person first, and/or take the conversation offline). If you aim to be nicer online than you are face to face, you’ll probably avoid the accidental lapses in tone that can cause real relationship and business problems.

Beware of bragging or groaning. Many people post a lot of brags (“Just got off the phone with an F500 company that is so excited to be working with me!”) or complaints (“Another day of mind-numbing meetings.”) The occasional victory cheer is totally warranted, particularly when you’re sharing good news—but try to keep that to one brag a month, and try to share your news in a way that offers some value to your readers, like telling them how to register for the conference that just invited you to keynote. Complaints have their place too, but generally only if you’re asking for concrete support—which can be as direct as saying “I’m having a tough day, please send me something funny to cheer me up”—or if you’re being funny about your kvetching (and get someone to validate that you’re actually being funny).

Monitor yourself. At least every month or so, flip back through a few weeks of your social network updates to see if you like the overall tone of your profile. While most people see your updates one at a time, the moments when they really count—like when a prospective employer or client is checking you out—will be moments when someone is looking at your social media presence as a whole. So make sure you’re comfortable with the overall way you’re presenting yourself. You can also get some useful feedback by using a free tool like AnalyzeWords, which tells you the tone of the words you use most often on Twitter.

Remember that the Internet is forever. Every time I think we’ve all learned this one, an online scandal turns up ill-advised emails or tweets from someone who really should have known better. So I’m going to say it one more time: if you write it down, you should be prepared to see it on the front page of a newspaper. Even when you’re corresponding with someone via email, think about what would happen if this email got leaked. That doesn’t mean you can’t email your colleagues about confidential business dealings, but be sure that you can live with whatever you’ve written—so don’t write down anything that would sound small-minded or unethical (particularly if taken out of context). And when you’re posting on social networks, which are out in the open, assume that anyone can see anything—including your boss, your mother, your clients, and your kids.

Lead with your key point. Online readers have notoriously short attention spans. Whether you’re sending an email or posting to a social network, make sure that any actionable items, or any questions you want addressed, appear at the very top of your message. Then you can provide the context to go with that question. It’s much more effective to write, “Can you suggest a good H.R. consultant?” and then follow that with a description of what you’re looking for, than to provide a paragraph of explanation before getting to your request. If it feels ironic that I’m ending with “start with the most important point first,” take this as a case in point: getting your tone right is actually the place where people typically run into trouble online, so figuring out how structure your messages is a relatively simple task—one to tackle once you’ve got your tone down. What it comes down to is this: read your message before you send it, and if you need to, move your most important idea up to the top.

If you follow these guidelines, you’ll end up with an online voice that falls somewhere between the way you communicate face-to-face, and the way you communicate in formal documents. And that’s the very reason that online communication is so appealing, and so uniquely effective: by combining the forethought of the written word with the humanity of conversation, it lets us connect and work together in ways that were once impossible.

The Right Way to Prepare Your Budget

You know it’s important to weigh the costs and benefits before committing resources. So what are the crucial strategies when preparing a budget? How can you use past financial data to inform your assumptions? And how can you ensure your budget will help you meet your strategic goals? This advice, adapted from the book Finance Basics, will help you better understand how to create a useful budget.

Budgets should be ambitious but realistic. Don’t map out a budget that you can’t meet—but don’t underestimate the possibilities. Here’s how to begin.

First, list three to five goals that you hope to achieve during the period for which you are budgeting. For example:

Increase gross sales by 5%.

Decrease administrative costs as a percentage of revenue by 3 points.

Reduce inventories by 2% by the end of the fiscal year.

Make sure those goals line up with the organization’s strategic priorities.

Next, figure out how you’ll achieve them. (Remember that a budget is just a plan with numbers.) How can you generate more revenue? Will you need more sales representatives? Where can you cut costs or reduce inventories?

The smaller the unit you’re focusing on, the more detail you need. If you’re creating a budget for a 12-person sales office, you typically won’t have to worry about capital expenditures such as major upgrades to the building. But you should include detailed estimates for travel costs, telephones and utilities, and office supplies. As you move up in the organization, the scope of your budget will broaden. You can assume that the head of the 12-person office has thought about printer cartridges and gasoline for the sales reps’ cars. Your job now is to look at big-picture items such as computer systems and to determine how all the smaller-scale budgets fit together.

Other issues to consider when you’re preparing a budget:

Term. Is the budget just for this year, or is it for the next five years? Most budgets apply only to the upcoming year and are reviewed every month or every quarter.

Assumptions. At its simplest, a budget creates projections by adding assumptions to current data. Look hard at the assumptions you’re making. Let’s suppose you think sales will rise by 10% in the coming year if you add two more people to your unit. Explain what you’re basing that assumption on, and show a clear connection to at least one strategic goal (in this case, it’s probably to increase sales by a certain percentage).

Role-playing may help you here. Put yourself in the position of a division manager with limited resources and many requests for funding: Under those circumstances, what would persuade you to grant a request for two additional staff members?

Articulating your assumptions

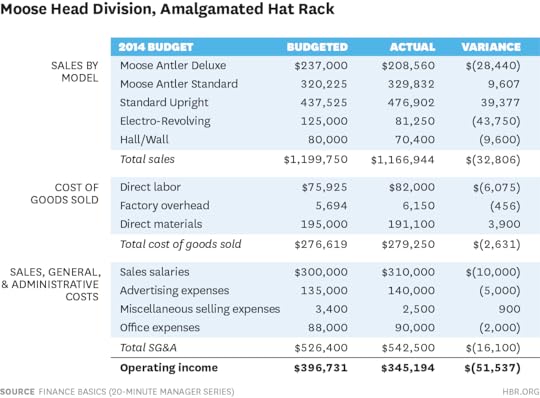

Usually, budgeters take the previous year’s budget as a starting point. If you’re the manager of the Moose Head Division at the fictional company Amalgamated Hat Rack, for instance, you might look at the 2014 budget to get ideas about how to increase revenue, cut costs, or both. (See the figure below, “Moose Head Division, Amalgamated Hat Rack.” Note that the parentheses in the table indicate unfavorable variances.)

Don’t look only at specific revenue or cost line items, because revenue and costs are closely linked. Instead, ask yourself what the budget shows about last year’s operations. As the table shows, the Standard Upright and the Moose Antler Standard exceeded sales expectations in 2014. Perhaps it would make sense to increase your sales projections for those products, particularly if your sales reps are optimistic about the prospects for more sales. The Standard Upright might be a particularly good choice, since it beat its 2014 projection by 9%. Could you increase the anticipated sales for this model by 5% or 10% in 2015? How much more would you have to spend on sales or marketing to achieve this increase? To make the decision, you’ll need as much data as you can get about pricing, competitors, new sales channels, and other relevant issues.

Alternatively, you might plan to eliminate some products. The Electro-Revolving model, for example, is faring poorly. Would it be better to cut this line and promote the newer Hall/Wall model? That would eliminate $81,250 in sales, but the Electro-Revolving is expensive to produce, so discontinuation might not have much impact on the bottom line.

Other questions to ask yourself:

Will you keep prices the same, lower them, or raise them? A price increase of 3% might offset the budget’s 2014 sales shortfall, provided that it doesn’t dampen demand.

Do you plan to enter new markets, target new customers, or use new sales strategies? How much additional revenue do you expect these efforts to bring in? How much will these initiatives cost?

Will your cost of goods change? For example, perhaps you plan to cut down on temporary help and add full-time employees in the plant. Or perhaps you hope to reduce wage costs through automation. If so, how much will it cost to automate?

Are your suppliers likely to raise or lower prices? Are you planning to switch to lower-cost suppliers? Will quality suffer as a result? If so, how much will that affect your sales?

Do you need to enhance your product to keep your current customers?

Does your staff need further training?

Are you planning to pursue other special projects or initiatives?

Articulating your answers to questions like these ensures that your assumptions won’t go unexamined. It will help you create budget numbers that are as realistic as possible.

Adapted from

Finance Basics (20-Minute Manager Series)

Finance & Accounting Book

12.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Quantifying your assumptions

Now you need to translate your assumptions and scenarios into dollar figures. Begin with last year’s budget and make the changes that fit your plans. If your entire staff of 12 needs sales training, for instance, find out how much the training will cost and add in that amount. Ask your coworkers for their ideas about costs as well. And consult the websites of trade associations or trade publications for data on industry averages.

Because your budget must be compared and combined with others in the organization, your company will probably provide you with a standard set of line items. When you’ve filled those in, take a step back: Does this budget meet your unit’s goals? It’s easy to overlook big-picture goals as you get into line-by-line details. Is your budget defensible? You may be perfectly happy with it, but you’ll need to win over the budget committee. Once again, push your assumptions. Could you do with one extra staff member instead of two? If not, be sure you can make a good argument as to why not.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers