Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1266

August 5, 2015

How the Philippines Became Tech Startups’ New Source for Talent

Fifteen years ago, Fort Bonifacio in the Philippines was a former military base still dotted with barracks built in World War II. Thanks to an aggressive privatization and conversion program, Bonifacio Global City — as the base is known today — is a modern, bustling financial district lined with blocks of skyscrapers, shopping malls, and luxury condos.

The Southeast Asia city’s rapid growth echoes the story of the so-called “unicorns” — technology start-ups that rapidly grew to a billion-dollar valuation and beyond. So far, 2015 has produced 30 unicorns. But as start-ups mature, the grow-at-all-cost narrative will be replaced by a flight to capital efficiency and profitability.

In this next chapter, the Philippines — the world’s second-fastest growing economy — will play a crucial role in helping tech companies access the talent to scale efficiently and sustainably.

The Philippines has a huge business process outsourcing industry. It employs over a million workers and is expected to hit $25 billion in revenues in 2016. That’s significant for a country with a GDP of $270 billion. Technology-enabled services are the backbone of this industry, and the fastest growing sectors have demand for high-end skills, such as mobile app development and data analytics, as well as middle-level skills, such as video production, copywriting, and financial analysis.

Technology start-ups are the Philippines’ latest customers, and more are flocking to the country’s beach-laden shores each year. Beyond the obvious labor cost savings, the Philippines is an attractive destination for tech jobs, particularly for American companies, because of its young, educated workforce and its English-speaking population (the fifth largest on the planet). Unlike other outsourcing hubs, Filipinos are intimately familiar with American culture, a legacy of more than 30 years of American colonial rule. Generations of Filipinos have been raised on Hollywood movies, Friends, the NBA, and of course, Facebook.

The median age is 24, and local universities produce over 130,000 graduates in information technology and engineering each year. Most are skilled in the more ubiquitous programming languages and producing iOS and Android apps. A great web developer with at least five years’ experience can cost less than $25,000 a year.

Combine these basic building blocks with the rise of cloud computing and you have new ways of building a flexible, distributed workforce as a start-up rapidly grows. For example, American services marketplace Thumbtack leverages close to 1,000 home-based contractors in the Philippines to help with business operations. This virtual set-up and access to on-demand talent helps the company scale much faster than it could if it were geographically constrained.

But alongside the skill, there’s the shift in mindset among younger workers in the industry. Traditionally, business process outsourcing was associated with high-volume, low-price work. Today, the mainstream appeal of Silicon Valley is turning young Filipino workers who might have been satisfied with a call center job a decade ago into a creative and entrepreneurial class seeking a deeper connection with innovation-driven and mission-focused companies. Working for a venture-backed start-up is the new status symbol. As a start-up founder, my biggest competitors in the talent market are no longer the local family conglomerates. They’re tech companies from the U.S., Germany, Singapore, and Japan coming to the Philippines.

This cultural shift is a great thing for start-ups. No longer satisfied with back office support work, this fresh cadre of talent wants to be part of the front line and build new products and services. When Jessica Mah, founder of inDinero needed to turn around her Y-Combinator-backed online accounting start-up, she decided to deliver a SAAS-based product with a high-touch service component. So she built a team of accountants in the Philippines that is familiar with U.S. General Accepted Accounting Principles. In combination with its proprietary B2B software, this team plays a critical role in delivering inDinero’s suite of accounting, payroll, and tax preparation services.

Over time, local outsourcing vendors can evolve into strategic partners and recipients of venture capital investment. Many local entrepreneurs that started in outsourcing eventually moved on to found technology companies backed by Silicon Valley investors, such as Y-Combinator, the Omidyar Network, and 500 Startups. These growing companies provide great opportunity for their overseas counterparts. Take Rocket Internet’s strategic partnership with PLDT, a Philippine telco and IT company, for example. Rocket operates some of the largest e-commerce platforms in emerging markets. It partnered with PLDT in a $445 million investment deal that involves deploying PLDT’s mobile payments solution to Rocket platforms outside the Philippines, and codevelop digital services using teams composed of Filipino and Rocket engineers.

In addition to investment potential, there are opportunities to move into new markets, given the Philippines’ unique strengths in Southeast Asia. Because of the ubiquity of English, product managers have found it relatively quick and easy to use the Philippines as a test market to deploy and iterate new applications without the need for translation into a non-English language. For example, Facebook quietly piloted a feature during the Philippine typhoon last year that allows users to leverage on their social graph for real-time information in disaster situations. Uber tested an on-demand courier service last holiday season.

“The Philippines is a natural gateway to the broader Southeast Asia market. Filipinos share a common ethnicity with other Southeast Asian countries. But it’s also the most westernized country in the region. This makes it a fertile testing ground for a product that can scale to other emerging markets,” wrote Nix Nolledo, CEO of Xurpas, a mobile content company that builds apps and games for Southeast Asian markets, in an email.

Emerging markets are a popular place to outsource cheap labor. But the talent that some of these areas house can provide benefits for technology start-ups that go beyond simply cutting costs and offering low-skill work. Filipino workers are proving themselves to be valuable partners in the growing tech industry, and start-ups should take notice.

The Two Essential Entrepreneurial Types

In my research on innovators, I like to draw the distinction between “path finders” and “path creators.” Rarely does the metaphor seem so apt as in the case of Federico Bastiani. He is the originator of the “social streets” movement now spreading across Italy, so the innovation he created literally involves a path: the street in which he and his family live in Bologna.

Bastiani grew up in a small town in Tuscany, where people knew and helped their neighbors. When he moved to the city he was disheartened by how little social connection he had to the other residents of his street. His solution, in 2013, was to create a Facebook page called “Residents of Via Fondazza—Bologna” which he promoted by posting flyers in his neighborhood. Quickly, people began to connect with it, and soon the page became a place for neighbors not only to get to know one another but also to arrange to help each other in various ways. As one article reports, people were soon “giving free piano lessons, lending washing machines, providing tips to newcomers about services in the city, giving away leftover food when going on holiday, holding street birthday parties,” and more.

But Bastiani and the others he had engaged in this project didn’t stop at the end of their own street. They publicized the success of the model and created a website to guide others who wanted to do the same. As of January 2015 there were at least 330 other social streets established in Italy, and more than 360 in other parts of the world.

We could say, then, that Bastiani is a path creator, and the enterprising people in the other cities, making progress with access to his story and approach, are path finders. Both are essential entrepreneurial types, in the commercial as well as the social sector, but the former is much more rare than the latter. The difference between them is not how boldly venturesome they are, but the extent to which they rely on preexisting knowledge.

Path finders are map readers. They very reasonably rely on already-discovered ways to do things as they seek new opportunities. The steps they take are valuable but not usually surprising (to themselves or others). They accept that they will face and have to manage risk when they set out to build something new.

In contrast, path creators avoid best practices, rules, and existing rights of way. They don’t need the comfort of roads already traveled and don’t filter their visions through the judgments of others. Innovation, for them, is a form of disobedience; they revel in the uncertainty and unpredictability of creating solutions that are sui generis. As I describe in The Role of Creative Ignorance, their open-mindedness is key to their ability to come up with new and better approaches, and sometimes cause fundamental alterations to what is understood about the world. They can be terrifically disruptive, depending on the institutional, entrepreneurial, and social contexts in which they act.

Given all this, it is interesting to consider in which direction today’s advances in information and communications technology are taking us: Are they encouraging more path finding or more path creating? As early as the 1960s, Peter Drucker told managers that the thorniest problems they faced in applying technology were not of a technical nature, but human ones. This remains true. If we want technology-fueled progress, we should be figuring out how to help humans use technology to open up new territory, not just to map the territory we know in ever greater detail.

Either is possible, for example, with big data. Path finders value big data for its power to fill in as many details as possible on their knowledge maps, allowing them to identify the most reliable steps to take. By contrast, path creators see the extra layers of detail offered by big data as the enemy of creative ignorance. The appeal of big data for them is the chance to see patterns that disprove the assumptions that come with acquired knowledge. As the great Italian physicist Enrico Fermi put it, “If the result confirms the hypothesis, then you’ve made a measurement. If the result is contrary to the hypothesis, then you’ve made a discovery.” Of course it was data that allowed Galileo Galilei to discover, contrary to all received wisdom, that the Earth moves around the Sun. The defiant statement attributed to him even as he was forced to recant his finding—Eppur si muove (“And yet it moves”)—could be the battle cry of all path creators.

When someone like Federico Bastiani takes a modern technology like an online social networking platform and finds in it a way to enrich the physical reality of a neighborhood, he is using it for path-creating purposes. To get more innovations like social streets—technology-supported solutions that add so much to human life that they turn into movements—I would argue we need more than technologists taking technology to the next level. We need humanists, deeply attuned to what would make their lives and their neighbors’ lives more fulfilling, and unconstrained in imagining how to use an ever-evolving toolkit to deliver it.

This post is one in a series of perspectives by presenters and participants in the 7th Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 5-6, 2015 in Vienna. The theme: Claiming Our Humanity — Managing in the Digital Age.

To Really Help the Global Poor, Create Technology They’ll Pay For

Investing in technology can help lift people out of poverty, and investments that use technology for development are good for business, creating millions of new customers. But the development landscape is littered with projects that never got past the pilot stage. When the seed funding from philanthropies or governments runs out, if projects haven’t signed up enough paying users, there’s nothing to fuel growth.

As simple as it sounds, development projects need revenue. Many organizations aim to narrow the “digital divide”: the socioeconomic gap between people with Internet access and the skills to make use of it and people who lack those resources. Using information and communications technology (ICT) for development is fairly common, but surprisingly, most digital divide projects don’t generate revenue. Some projects seem never to have been designed as anything other than pilots: they remain limited and local, delivering only marginal benefits.

To determine the best approach to using ICT for development (or ICT4D, as it’s sometimes called), Huawei recently interviewed 150 telecom operators, government bodies, regulators, NGOs, and social enterprises in 11 countries. Many people we spoke with said there were simply too many projects that were based on good ideas but lacked adequate funding. Some countries have grown so frustrated with small, unsustainable pilot projects that they have actually banned them: Uganda, for example, which has only one doctor for every 25,000 people, has issued a moratorium on new mobile health initiatives.

The most common response we received, however, was that successful ICT4D efforts start by providing something that users value enough to pay for. Value, of course, resides in the mind of the customer, and many potential beneficiaries simply don’t understand the value of being online. An Economist Intelligence Unit report commissioned by Huawei in 2013 found that “a lack of perceived value” is one of the main things that keeps a lid on digital adoption and usage rates. Another recent survey found that half of rural Brazilians would not be interested in internet access, even if it were free.

NGOs and philanthropic organizations often give away their digital products and services, as if being free could compensate for a lack of value. In fact, for-profit tech companies often do the same thing, reasoning that if they build a huge user base now, they can figure out how to monetize it later. This approach consigns many ICT4D projects and tech startups alike to failure. Hystra Consulting, which works with businesses and social entrepreneurs, studied 280 ICT4D projects and found that 136 relied completely on donor funding to cover their operating costs, while 35 were partly subsidized.

Supplying something that customers will pay for has another virtue: it provides feedback, which many digital inclusion projects lack. By charging even a small amount, ICT initiatives get a clear signal about how to adapt their offerings in response to changing conditions. Without this feedback, they operate in a vacuum of good intentions, insulated from the market and ultimately cut off from the very communities they are trying to serve. Nothing provides clearer evidence of a project’s viability than a base of paying customers, and this proof of success makes scaling up vastly easier.

For example, take Bridge International Academies, which runs 400 for-profit schools for 120,000 students in Uganda and Kenya whose families earn less than $2 a day. Its ICT systems have standardized the life cycle of education delivery: the way schools are built, how teachers are selected and trained, and how lessons are delivered and monitored for improvement. Costs are low because each school has just one employee, who uses a tablet with tailored content. Non-classroom activities, such as billing and admissions, are processed automatically through a smartphone application connected to the school’s back-office software. Everything – tuition, school lunches, staff salaries – is paid for with mobile money. In fact, the school doesn’t accept cash at all. Bridge provides an excellent example of using technology to solve social needs in a profitable and scalable way, achieving proven social impact at a reasonable cost. It opens a new school every 2.5 days, and aims to teach 10 million children over the next decade.

Another example is M-KOPA, a revenue-generating social enterprise that sells lighting systems to the rural poor in Uganda and Kenya. Villages in those areas often lie off the electricity grid, which means the only available form of lighting comes from kerosene lanterns that emit harmful fumes and pose a fire hazard. M-KOPA sells a home solar energy system for about US $200, too much for any of its customers to pay at one time, but the same as what a household could expect to spend on kerosene in a year. The company charges customers a small payment up front, followed by micropayments of about 46 cents made daily by cell phone over the course of a year. After 12 months, customers own their systems outright—or can continue paying and get an upgraded version. M-KOPA’s strategy of providing a valuable product and charging small fees that generate revenue has allowed the company to grow: as of January 2015, it employed about 500 full-time staff and sold its products through a network of about 1,000 direct sales representatives.

Finally, Vodafone Farmer’s Club provides agricultural information that helps farmers improve their livelihoods. Launched six years ago in Turkey, where roughly a quarter of the population are farmers, the service provides early warnings of storms and extreme weather, tips on the best times to harvest, updated commodity prices, and expert techniques on how to control pests, maximize crop yields, and manage agricultural resources. Customers can pay monthly, or choose an annual billing option that lets them pay at harvest time, when their income is highest. Currently 1.2 million Turkish farmers subscribe to the service, which Vodafone will expand to India, Ghana, Kenya, and Tanzania this year. From 2012–2013 alone, the service improved Turkish farmers’ productivity by an estimated €190 million.

These success stories cannot remain the exception. The widespread failure of ICT4D pilot projects demonstrates that making digital services free is not enough—the goal should be to make them valuable. Technologies that don’t meet this goal are exacerbating the digital divide, not helping to close it.

It’s easy to envision a technological future where those with wearables enjoy better health, where cities using “Internet of Vehicles” technology have lighter traffic and fewer accidents, and where countries that use agricultural sensors have a more abundant food supply. Without sustainable, scalable ICT4D efforts, non-adopters will continue falling further and further behind, and people everywhere will miss out on how technology can improve their lives, make economies more vibrant, and foster global development.

What Salespeople Need to Know About the New B2B Landscape

Selling has always been more about the buyer than the seller. So any effective sales model must adapt to changing buying protocols, not ignore or resist them. This is a big transition for firms whose marketing, sales-training and enablement tools, and wider organizational processes reflect outdated assumptions about purchasing in their markets.

For a century, buying has been framed in terms of moving a prospect from Awareness to Interest to Desire to Action (AIDA). The AIDA model and its variants are the basis for sales funnels at many B2B firms. The typical funnel starts with a marketing-generated lead for a “suspect” that, after qualification, becomes a “prospect,” and then a customer through steps that are measured and managed. In each step, sales people are expected to perform a series of tasks, usually sequentially, in order to close. It’s an inside-out process and CRM systems are there to provide data about progression (or not) through that company’s funnel steps — the famous “pipeline” metrics that dominate so much talk about sales.

But Gartner research (see here and here) indicates a very different contemporary buying reality. Rather than moving sequentially through a funnel, buyers actually work through four parallel streams to make a purchase decision.

Let’s examine these activities, one by one:

Explore: Here, buyers identify a need or opportunity and begin looking for ways to address it, usually via interactions with vendors and self-directed information search on the internet.

Evaluate: Buyers take a closer look at options uncovered while exploring, again leaning heavily on self-directed search and peer interactions as well as vendor sales representatives.

Engage: Buyers initiate further contact with providers (or accept proposals from providers) to get help in moving toward a purchase decision.

Experience: Buyers use a solution, increasingly in pilots or proof of concepts, and develop perceptions about its value based on that usage.

With these changes in mind, understanding where customers are, and how to interact with them appropriately in a given stream, are now central to effective selling.

Here are a few tips and insights to help you navigate these shifts.

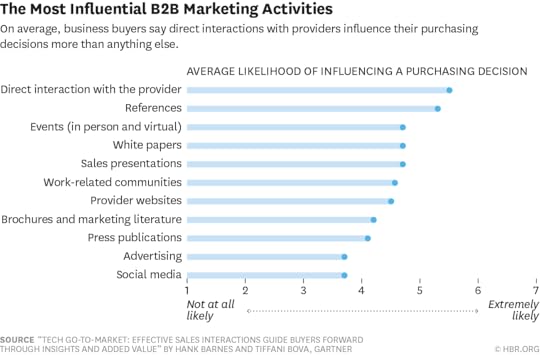

The sales force is more important than ever. Regardless of which path customers take, or in which order they take them, they want to deal with people who can help them move toward a purchase decision, be the internal champion at the vendor, and bring it together for that customer. In fact, B2B buyers report that, compared to other sources of information, these interactions are the most influential in their decision making process:

The source considered the least influential is social media. Don’t believe the hype. Sales people have not been replaced by digital, and providing relevant solutions remains key in most B2B buying scenarios.

One reason why the sales force remains so important to the B2B customer is that most products and services sold to business organizations are components in a wider usage system at that buyer, and customer value ultimately resides in that usage, not just the individual product.

To add to that, business buyers must justify a decision to others in the organization, especially as capital expenditures flow less liberally in many industries since the financial crisis of 2008. And you are naïve or spending too much time on your smartphone if you believe that a combination of economics, solution identification, product application, risk management, and political journey through the buyer’s organization is now handled predominately online in most buying scenarios and without knowledgeable and savvy sales help.

The research also found that, across all buying streams, buyers emphasized that interactions with sellers — technical demonstrations, sales presentations tailored to my company’s need – should be about the buyer’s needs. Among the least valued interactions are sales calls in response to registering for webinars or events. That is, core solution-selling and account-management skills still matter.

Lastly, although buyers certainly use online search, they use it as a complement to, not a substitute for, interactions with sales reps, channel partners, and others at their suppliers. If anything, access to information online has increased awareness that relevant alternatives and best practices about product applications and service requirements often reside outside one’s firm. In turn, this drives the B2B buyer’s propensity to seek information from vendors who work with companies across regions or vertical segments, and who can use that knowledge to help frame and deliver solutions for that buyer’s needs.

Buying is a continuous and dynamic process. Specious talk about disintermediation of salespeople obscures the real issues facing firms. Sales people are not disappearing, but buying processes and therefore sales tasks are changing.

For example, note that in the second figure above customer references are a close second in terms of influence, and the nature of references has changed. In the past, a buyer might ask for references and that seller would cite a few satisfied customers. But through the web, customers connect with each other and get unedited versions of others’ experience through review sites such as bazaarvoice and PowerReviews, and they gain access to thousands of people at other companies who can share experiences and options through community sites such as SAP Developer Network and Marketo Marketing Nation.

Also playing important roles are events, white papers, and the seller’s website — activities that are typically part of marketing’s domain, not sales. This puts pressure on a notoriously fraught relationship: improving coordination between sales and marketing, two functions that are increasingly interdependent but different in their perspectives and procedures. The marketing–sales relationship now tops the agenda of concerns in a survey of B2B executives.

More generally, it’s important to recognize that web sites, blogs, and other digital media have made vendor organizations more visible and transparent to potential buyers, which has disrupted the inside-out funnel approach. Prospects now touch your brand and company at many different points (online, offline, marketing collateral, and so on), when they want, and each touch has an impact on selling tasks. Buyers value interaction with others at your firm besides the sales person (e.g., product specialists, technical experts, professional services personnel, delivery personnel, pre- and post-sales applications resources). In their buying streams, they expect the rep to orchestrate those interactions purposefully, and efficient coordination of these interaction points must be reflected in an effective 21st-century go-to-market strategy.

Finally, if you consider the streams that now characterize B2B buying and what buyers value in their suppliers’ behaviors, a big disconnect becomes apparent. Despite huge advances in technology over the past two decades, most sales models and performance practices are the ad-hoc accumulation of years of reactive decisions, often by different managers pursuing different goals. This is why many B2B sales models firms are incapable of dealing with the reality that buying is now continuous and dynamic — an on-going movie, not a selfie or snapshot in a funnel.

Choices are often false. Despite what you often hear, no single tactic — e.g., a given selling methodology, “challenging” the customer, or more “big data” analytics — will address the new reality. Aligning buying and selling is a process, not a one-shot deal.

Going forward, many B2B sellers will need to reconfigure their selling processes more effectively and efficiently for each buying stream. They should not waste lots of time and energy debating whether to be online or in-person, interacting via the web or through sales reps, digital or human. They need to do both, and create the right mix for their go-to-market programs.

It’s also important that every group within an organization that deals with customers has a shared vision of how customers buy and, more importantly, a clear sense of their company’s strategy. The cross-functional communication and coordination that is required to navigate this change is the job of leadership. Is your organization, not just your sales force, ready to deal with this purchasing reality?

Finally, to paraphrase Churchill, it is not “the end of solution sales” and it’s not the beginning of the end. But it should be the end of glib generalizations about sales and selling, which remain complex, changing, and people-dependent activities in most B2B markets. As a leader, understanding how buying really works is the place to start in order to spur effective selling, profitable growth, and better resource allocations in your firm.

Leading Job Growth in the Digital Economy

Courtesy of Manuel Ferrol

Last week I visited Finisterre, an ancient Spanish port and fishing village, where my grandfather was born. He, like many others, was forced to emigrate to Argentina at the end of the 19th century, leaving land, family, and friends in search of employment, since jobs were increasingly scarce at home. This photograph from the period, O home e o neno, shows a man and his son crying as some of their dearest relatives board the boat to Buenos Aires.

The heart-wrenching scene reminded me of the terrible challenges that today’s job-seekers face thanks to the advance of technologies that make human labor obsolete. In many ways, the situation is even worse than it was in my grandfather’s time. While the men of Finisterre could flee economic conditions in Spain, there is no escaping employment market upheaval in the digital age.

Consider the global trends cited by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee in a recent interview with HBR. In most countries, both developed and developing, private employment and median family income have stopped growing at the same pace as labor productivity and real GDP per capita—mostly due, they argue, to technological advances. In emerging markets, labor’s share of GDP is declining in 42 out of 59 countries, including China, Mexico and India. These are areas with 90% of the world’s population, higher birth rates, more young people, and lower education standards. Scarcer jobs and diminishing wages can only lead to greater inequality and global instability.

So what are we to do? Learn from the countries that are bucking the trend. In Singapore, median income, GDP per capita and labor productivity have all grown dramatically and in tandem over the past 30 years; unemployment stands at just 3%; wages account for a larger percentage of GDP than they did in 1980; and middle-income earnings have increased six-fold in the past five decades. With the highest median wage among newly industrialized Asian nations, the city-state also ranks first globally in worker productivity and attitude.

Although it has no natural resources, Singapore has succeeded by investing large portions of its public budget in education, a strong civil service, and the development of great leaders, proactively moving its economy away from basic manufacturing, to higher value, technology-based manufacturing, then to knowledge-based R&D sectors.

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, who passed away earlier this year, set the tone with a speech he gave to senior civil servants, just after his country’s transition to independence from the United Kingdom in 1965: “Singapore must get some of [the] best in each year’s crop of graduates into government,” he said. He added that he wanted leaders with not just stellar academic records but also imagination, dynamism and, especially, character and motivation. His administration followed up by instituting massive public sector scholarship programs; rigorous assessment practices focused on potential; extensive development and training, including exemplary rotations and milestone courses; and outstanding promotion, recognition, and salary benchmarking practices to match private employers. As a result, according to HBS’s Michael Porter, Singapore developed a highly efficient civil service elite that has been able to dynamically shift policies and priorities over time.

Professions-based education – that which ensures future employability for students – has also been a key area for investment and innovation in the country. Today, 95% of its young people progress to post-secondary education institutes, but there are also different pathways to work, including German-style an apprenticeship and certification program. Most recently, Singapore launched the SkillsFuture initiative, including a fund where the government provides a yearly stipend to be used for continuing education at all levels. Government expenditure on education remains dramatically higher than it is in other OECD countries.

Can other countries follow this model? With the right leadership, I think so. On a recent trip to Africa I was greatly impressed by the African Leadership Academy (ALA), an extraordinary institution founded in 2008, which offers a highly selective two-year pan-African pre-university program. (Out of 4,000 applicants per year, only 100 are chosen.) Nearly 800 young people have already studied there, and the goal is to develop 6,000 leaders over the next five decades – people screened for their perserverance, courage, passion and ethics, who will, it’s hoped, go on to transform Africa as country presidents, central bank governors, or CEOs of major corporations.

This is the sort of institution public and private organizations around the world should be looking to build because, as the title of my latest book notes, It’s Not the How or the What but the Who. We need extraordinary leaders to face the monumental challenge of preserving human dignity in the digital age.

This post is one in a series of perspectives by presenters and participants in the 7th Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 5-6, 2015 in Vienna. The theme: Claiming Our Humanity — Managing in the Digital Age.

How to Do Walking Meetings Right

Fran Melmed is the founder of context, a communication and change management consulting firm. She spends her days performing communication audits for organizations and meeting with clients. Sounds like a recipe for a sedentary workday, right? On the contrary. Fran is part of a growing trend known as walking meetings or “walk and talk.”

A walking meeting is simply that: a meeting that takes place during a walk instead of in an office, boardroom, or coffee shop where meetings are commonly held. Nilofer Merchant wrote in HBR about her own transition to walking meetings after realizing that, like many Americans, she was sitting way too much while working. Merchant traded her coffee-shop meetings for walking meetings and immediately saw the benefits. Likewise, Melmed finds that merely holding some of her meetings while walking has given her the necessary “unplugging” time she needs in order to be an effective writer.

Recent research finds that the act of walking leads to increases in creative thinking. This certainly supports the usefulness of walking meetings. Plenty of anecdotal evidence also suggests that walking meetings lead to more honest exchanges with employees and are more productive than traditional sit-down meetings.

Based on this, we undertook an exploratory study of the benefits associated with walking. We surveyed a population of approximately 150 working adults in the U.S. to gather input about their walking meeting and work habits. In short, we find that those who participate in walking meetings are 5.25% more likely to report being creative at their jobs than those who do not. Additionally, the responses suggest that walking meetings support cognitive engagement, or focus, on the job. Those who participate in walking meetings are 8.5% more likely to report high levels of engagement.

What we found adds support to the notion of walking meetings being beneficial for workers. Is an increase in creativity of 5.25% likely to make or break a business? Most likely not. However, look at these findings through the lens of a cost-benefit analysis. The costs associated with regularly participating in walking meetings are next to nil. Keep in mind that walking meetings are not breaks from work. They are meetings that would have taken place regardless of whether they were held in someone’s office or while walking around your office complex. There may be no cheaper way to achieve moderate increases in creativity and engagement.

Just how do walking meetings produce these positive benefits in the workplace? Ted Eytan, MD, Medical Director of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Total Health and a vocal advocate of walking meetings, has some ideas. First, from a neurochemical perspective, Dr. Eytan emphasizes that our brains are more relaxed during walks due to the release of certain chemicals. This aids executive function, which governs how we focus on tasks and deal with unforeseen events, among other things. Open-ended responses to our survey seemed to back this up by referring to moments of creativity sparked by walking meetings.

Furthermore, Dr. Eytan believes walking meetings lead to better employee engagement by breaking down barriers between supervisor and subordinate or between coworkers. He sees the bonding achieved through walking meetings as a micro version of the bonding that can be experienced when coworkers travel together on business trips. David Haimes, a senior director of product development at Oracle, has experienced this in his meetings with team members: “The fact that we are walking side-by-side means the conversation is more peer-to-peer than when I am in my office and they are across a desk from me, which reinforces the organizational hierarchy.”

To be sure, not all meetings are suitable for walking meetings (and not everyone is physically able to participate in walking meetings). Sometimes it is valuable to have materials or a whiteboard close at hand, and sometimes, as in an intense negotiation, it is important to be face-to-face. The best candidates for walking meetings are ones where colleagues are conferring on decisions or exploring possible solutions. Indeed, in our survey, participants holding managerial and professional positions experienced more of a creativity boost from walking meetings than those in technical or administrative type jobs (though all categories realized some benefits).

If you are inspired to give walking meetings a try, here are a few tips that can help your walking meeting go well:

Consider including an “extracurricular” destination on your route. Dr. Eytan, whose office is located in Washington, D.C., often mentions the nearby Washington Coliseum as a place to stroll by, and notes it is where the Beatles played their first U.S. concert. Naming a point of interest, he says, provides more rationale and incentive for others to go for a walk.

Avoid making the destination a source of unneeded calories. One of the arguments in favor of walking meetings is the health benefit. However, this is easily negated if the walking meeting leads to a 425-calorie white-chocolate mocha that wouldn’t otherwise be consumed.

Do not surprise colleagues or clients with walking meetings. It’s fine to suggest a walk if it seems appropriate in the moment, as long as it’s clear that you’ll be fine with a “maybe next time.” But if you’re planning ahead to spend your time with someone in a walking meeting, have the courtesy to notify them in advance, too. This allows them to arrive dressed for comfort, perhaps having changed shoes. You might also keep water bottles on hand to offer on warm days.

Stick to small groups. Haimes recommends a maximum of three people for a walking meeting.

Have fun. Enjoy the experience of combining work with a bit of exercise and fresh air. Perhaps this is the one piece of advice that doesn’t need to be given. Our data show that those who participate in walking meetings are more satisfied at their jobs than their colleagues who don’t.

Based on our survey and the clear case to be made for walking in general as a key to good health, there would seem to be no good argument against making a habit of walking meetings — or at least giving it a try.

August 4, 2015

Merging Two Global Company Cultures

While working his way up from Hyderabad, India, to 1 Procter & Gamble Plaza in Cincinnati, Ohio, Moheet Nagrath came to understand culture well enough to look past it. “I’m pretty convinced that there are superficial differences in culture and communication and how people do things,” said the global human resources officer. “There’s an essence. When you scratch the surface, people have the same needs, the same aspirations, and the same concerns.”

Nagrath spoke in reference to the company’s Purpose, Values, and Principles (or PVPs), written down in the late-1980’s amid P&G’s internationalization, and later translated to multiple languages. The statement sought to capture the company’s existing culture, while creating fresh sinews for integrating Mumbai with Geneva, Mexico City with Cincinnati. Over the years, it came to serve as a moral compass for guiding decisions. “What I tell the new hires is that this is the one thing in the company that will never change, these values and principles,” claimed the P&G Near East general manager.

Yet this universalism – the conviction that “we’re all the same” – sat in contrast to decades of lessons learned globalizing P&G’s billion-dollar brands, the guardians of which sat in the floors below as Nagrath spoke.

In the 1990s, P&G, like other companies, sought to take advantage of global scale and technology platforms, rolling out their products worldwide. But just as tastes for food differ, so do preferences for toothpaste, diapers, soap, and feminine hygiene products. Through trial and error, P&G, like so many other globalizing firms, overcame initial stumbles and became more adept at customizing products to local markets. By the 2000s, they had developed a methodology for a new class of culture-specific line extensions for specific markets, helping drive growth.

Just as the PVP became institutionalized throughout the organization, validating the assumption that “we’re all the same,” brand managers and product developers learned the opposite lesson: “We’re all different.”

Successfully managing with culture in mind is an art based on judgment – like a tightrope act, it hinges on balance. Or according to the words of famed French high wire walker, Philippe Petit, it’s about seeking self-correction and turning it into an art.

In a global organization like P&G, it’s not just about maintaining the balance between two alternatives, but doing so while leading a sprawling organization across roughly 80 national cultures. The tightrope turns into a suspended spider web.

This is what Nagrath and his fellow P&G leaders faced in their blockbuster acquisition of Gillette. They kept their balance and self-corrected using at least four methods:

Decategorize. When contact occurs in a situation like an acquisition and in-groups and out-groups form, members of the in-group have a tendency to homogenize members of the out-group, without attention to the diversity and differences within the out-group. To overcome this, leaders may structure contact situations so that members of the in-group and out-group must treat one another as individuals. P&G leadership took great pains to create integration teams composed of both groups who must work on shared tasks, thus forcing them to personalize their interactions and focus on specific, shared goals.

Recategorize. Another way to overcome in-group/out-group biases is to develop a superordinate category that includes both groups, thus enabling preservation of their cultural identities – and associated attributes – while creating a new, larger in-group. The challenge is to create a new “we.” It is common in mergers, for example, to rename the new organization to communicate this recategorization. Although P&G didn’t rename itself, like other companies, they pursued other forms of renaming.

Mutual differentiation. A related but distinct approach is to identify complementarities and structure group relations around them. Two groups may identify their relationship as a division of labor in service of a common goal. In the process, in-groups develop positive attitudes toward the out-group, while preserving the original identities. For example, Publicis Groupe, a French marketing and advertising agency, preserved acquired agency identities by reconceptualizing relationships as that of a family – families may elbow one another and even fight sometimes, but in the end they are family and help one another. Likewise, Gillette’s focus on male consumers complemented P&G’s expertise in female consumers. Gillette’s merchandising expertise complemented P&G’s branding acumen.

Healthy debate. Sometimes the cultural norms, values, and beliefs may inevitably conflict. At some point the value for hierarchy must contradict egalitarianism or consensus decision-making runs up against clearly demarcated decision rights. P&G leaders called out early the importance of taking the best of both, even if that meant recognizing Gillette practices as better. This was indeed the case in the development of a new decision-making protocol to move P&G away from their nemawashi tendencies.

Successfully managing through culture depends on the ability to understand it well enough to know whether, when, and how to take it into account. Too much emphasis on difference blinds you to the commonalities between groups. Yet at the same time it is easy to assume that others are just like you, that there is a universal way of being human. As a native from Hyderabad sitting in Cincinnati, Nagrath developed this sensitivity. The managerial art lies in developing awareness to differences without paying undue attention to them. Whether you’re integrating a culturally diverse team or adapting a product for a new market, the key is balance – and to self-correct before you fall.

How Talent Pulls One Over on the Capitalists

Last week I got a call from the founding CEO of a startup in which I am an angel investor. Outside investors, including me, had provided its $10 million in risk capital about three years ago. The founding group of managers, including the CEO, took sweat equity in the business. He was calling to get my consent to sell the company for $31 million. That sounded pretty good – a threefold payoff on a three-year investment.

But after telling me the sale price, he went into a carefully structured description of how that $31 million was going to be split up. He began by telling me that things weren’t going as well as management had hoped and that they had determined the company needed to be sold to a major player in their industry. Only one buyer had come forward and if our company didn’t do this deal, it was at risk of running out of cash. The subtext was: take this deal or your investment is gone.

Then came the punch line: the buyer had insisted on a deal structure by which the outside equity providers would be paid $11 million – a annual return of 3% that looks suspiciously like the interest rate on a secure bond, not a risky startup investment. Meanwhile, the founding group would be compensated on the basis of an earn-out structured to pay them $20 million if they achieved some relatively reasonable targets. Talent had managed to extract an impressive 95% of the $21 million upside, leaving the risk capital providers with only 5% — a nearly perfect extraction of value.

Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised. Last year, I wrote an article for this publication showing how over the past two decades, talent has taken over as the dominant factor in the economic equation, and today is using its bargaining power to extract an ever-greater share of the value it helps create. Hedge fund managers exemplify the phenomenon: with their clever combination of annual fees and carried interest charges, they take as much as 84% of the fund’s net earnings, while the actual providers of the risk investment capital get the remaining tiny sliver.

But of course, it’s not just hedge fund managers. As my personal experience attests, value extraction by talent can be a problem in new ventures as well.

Normally, equity investors in a new venture provide risk capital, reaping all of the upside in exchange for accepting the risk of losing 100% of their capital before debt holders take a hit. Debt providers accept a limited and fixed upside in exchange for downside protection by the equity capital. Meanwhile talent is given a free share in the equity as motivation. But in the modern talent-centric economy, we’re increasingly finding that talent manages somehow to secure itself a privileged position relative to the equity investors who purchased their stakes – to the extent that the latter are effectively being converted into debt holders.

As our phone call wound down, the CEO I’d backed explained that he had tried as hard as he could to get the seller to provide a more reasonable split of the upside but apparently his pleadings were of no avail. That’s not very surprising, of course, because the outcome was fully in the interests of both parties. The buyer got to make sure that the founders were fully motivated to achieve the earn-out targets and could not have cared less about the equity providers. And the founders got to keep 95% of the upside, rather than the minority proportion that their actual share ownership would have dictated.

It’s hard to see what we shareholders could have done about this. If we had refused, the founders could simply have walked away from the deal and we would have ended up with nothing. You could say that it’s just the risks of playing the game. Maybe. But I do worry that this kind of behavior will ultimately have a negative impact on economic growth. Who will ever want to provide risk capital if all they can rely on is a sense of guilt or obligation on the part of the entrepreneurial talent they’re expected to back?

Stop Worrying About Whether Machines Are “Intelligent”

Stephen Hawking, Bill Gates, and Elon Musk have sounded warnings that AI, especially robotic weapons, might escape our control and take over. Ray Kurzweil has claimed the “singularity” (his term for the moment of takeover) is at hand, surfacing some of our primitive terrors. Given the trend to a surveillance society, our deepening embrace of technology, and the emerging Internet of Things, are we right to be afraid?

One way to detect such a shift is “Turing’s Test,” a puzzle devised by the British mathematician Alan Turing. It challenges us to decide whether questions posed to a hidden respondent are being answered by a human or a computer. Rather than comparing our capabilities to the computer’s (based on memory, calculation speed, and so on) Turing’s Test explores our sense of consciousness. Our amazement at the machine’s knowledge and insight leads us to believe it has an intelligence greater than our own. The mechanism here is the same as at the mythical Greek spot of Delphi – where the famous Oracle supposedly spoke in gibberish that was interpreted by priests to be poetic prophecies. How readily we fool ourselves.

This indicates three views of the singularity. Firstly, and most naïve, is that as we create ever more complex systems there must come a point when they are more complex than us. But even then, as amazed at the system’s capabilities as we may be, we know these abilities have been engineered in. Calling the system “intelligent” abuses the meaning of the term, for its intelligence is only that of its human makers. Of course, a system might well fool those who do not understand what is going on, just as people unfamiliar with modern medicine may be fooled by a doctor’s “magic.”

A second notion, proposed by Herbert Simon and Allen Newell, is of machine intelligence based on heuristics. Their insight was that these human and non-logical work-rules, such as kitchen recipes or mate finding, could be programmed into a machine that is entirely logical. Medical diagnoses were early examples. Such systems are now common. They are “intelligent” to the extent programmers transport human-devised intelligent-seeming rules into the system. Comparing the results against the rules can lead to feedback, a mode of machine learning. Yet this, too, must be programmed in. Simon and Newell reminded us the system is displaying the programmer’s learning, not its own.

But Turing offered a third and different notion. His famous 1950 Mind article suggested that we may eventually be unable to distinguish machine intelligence from our own. Lacking the ability to make a distinction, we would conclude that their intelligence is fundamentally similar. But note that for Turing, machine consciousness is not at issue; the emphasis is on our inability to distinguish the machine’s “consciousness” from our own. We can assume we have capabilities machines lack, such as faith and love, but cannot ever define or test them. Turing simply proposed that machines could acquire all the rules necessary to imitate us so proficiently that they’d become indistinguishable. Is more needed for the singularity to arrive?

Not all are convinced. The deepest doubts revolve around imagination, our evident capacity to deal with the uncertainties in our lives, and non-computable situations such as choosing a mate or what to cook for dinner. Could machines ever mimic our imagining as well as our computation?

We believe our imagination is shaped — though not determined — by our experiences, and our ability to both think and observe our thinking. Might a machine learn to know itself and so become conscious? Though computers inhabit their own universe, not ours, and so do not live as we do, Turing presumed they might seem to mimic our imagining. With the Internet of Things, they might also get to share our panoply of senses and develop experiential learning capabilities we could not distinguish from our own. A “reverse Turing test” hovers in the background — just as we challenge computers to become human-like, so smart machines might choose to challenge us to become more computer-like, and ignore or punish us if we fail. Recall Star Trek’s Mr. Spock, who coped patiently, if a little stiffly, with humans’ failings.

And so I go back to my original question: Are we right to fear the singularity and all that it means – from robots taking our jobs to the advanced dystopias of science fiction? Are we right to worry about a loss of our own relevance in a world dominated by machines?

If a singularity really is coming, it’s beyond our ability understand it. Machines might become conscious – they may be already – but the odds are, we won’t be able to recognize it. If the singularity is not coming, then it’s just empty dogmatism. Hence our task is always more practical — to bring a machine’s functionality, as we comprehend it, to bear on our world and our projects, answering “What does it mean to us?” rather than puzzling about what we might mean to them.

This post is one in a series of perspectives by presenters and participants in the 7th Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 5-6, 2015 in Vienna. The theme: Claiming Our Humanity — Managing in the Digital Age.

How Target Is Taking Sustainable Products Mainstream

For years, the answer to the question “Do people really want to buy more sustainable products?” was a profound “sort of.” Surveys consistently show that we aspire to buy responsibly, and we even say we’ll pay more for environmental or socially preferable products. But purchase intent does not always translate to real sales, and companies have often struggled to make sustainable products more mainstream.

That seems to be changing. Kate Heiny, who very recently departed as the director of sustainability at Target, told the crowd at this summer’s sizable Sustainable Brands conference that: “With their words and wallets, our customers are asking for more [sustainable products].”

The numbers bear this out: Within Target’s “naturals and organics” category, sales grew 17% last year, four times faster than its total grocery sales. And it’s not just happening at Target. A new Conference Board study, as CFO magazine reported, reveals some startling growth in greener products at a dozen big companies like Kimberly-Clark, Dow, GE, Siemens, Toshiba, and more.

So why are sustainable products surging now? I’ve been in contact with Heiny and her team at Target over the last year about the program she helped build to drive product innovation and more sales. Our discussions focused on three reinforcing elements.

First, the company painstakingly built its own Sustainable Product Standard. Working with UL’s Good Guide system, Target scores 7,000 products on a 100-point scale, with 50 points at stake related to the toxicity of ingredients. Additional points are awarded for reduced packaging impacts (can consumers recycle it?) and transparency (that is, sharing all ingredients on the product labels with deductions for things like “fragrance” without the details). The list of no-no ingredients is long — 1,600 chemicals tracked or regulated by NGOs and governments around the world.

It’s unclear whether Target will really eliminate low-scoring products, but the company has certainly promoted the highest scoring options – and that’s part two of the story. Under the banner of “Made to Matter,” Target is showcasing good-guy products, including usual suspects like Ben & Jerry’s, Annie’s, Stonyfield, Seventh Generation, and Method, but also some lesser-known players. In total, these brands are projected to reach revenues of $1 billion at Target alone this year.

With this level of topline growth, it’s no wonder that Target wants more options.

This gets us to part 3, an unusual initiative with the company’s arch-rival Walmart to improve the sustainability of the entire personal care value chain. But in order to understand their unlikely collaboration, it’s important to consider the competitive strategic elements of Target’s approach.

Target has, until recently, lagged Walmart on building its brand around sustainability issues. For nearly a decade, Walmart has made environmental progress a priority, in word and in deeds. The company has made significant efforts to improve store operations with their impressive energy efficiency work and the purchase of more solar power than any entity in the U.S. besides the military. For years, the retail giant has also applied imposing pressure on suppliers to reduce and improve packaging, cut carbon, and much more.

While Target has also reduced its impacts and committed to using much more solar power, it always seemed like the company was searching for its unique, brand-appropriate approach to environmental and social issues. Now Target has clearly focused its attention on consumers. Making sustainable products more accessible is a great fit for Target — after all, the company was dubbed Tar-jay years ago after its many successful forays into making high-end design affordable.

This all isn’t to say that Walmart has sat still on the consumer front — a few months ago it launched an important experiment on walmart.com to highlight mainstream products “made by sustainability leaders,” as they called it. But by and large, for years, Walmart has taken, in my view, a mainly operational, cost-reducing, brand-fitting approach to sustainability.

Target is, by comparison, focusing much more about the downstream part of the value chain. But of course, for a retailer to provide better products to customers, it has to work with suppliers and, now it seems, even with competitors.

Target and Walmart launched the Personal Care Sustainability Summit last year, and invited the largest players in the $74 billion market for lotions, soaps, and other beauty and grooming products to join them. I attended the two main meetings thus far, first in Chicago in 2014 and then in Brooklyn earlier this year. In one room, at the behest of the two big guns of retail, sat the largest consumer product, chemical, and fragrance companies.

The collaboration, which the NGO Forum for the Future is managing, has high aspirations. They’ve developed ongoing working groups to seek solutions on critical themes like information sharing; agreements on science-based definitions for safety/toxicity on ingredients; and — in the truly unusual part — group R&D across the value chain to develop new, safer classes of chemicals (particularly in preservatives). Over the last five years, Walmart and Target have increasingly become what I call “de facto regulators” of chemicals through their programs to limit certain ingredients. But now they’re actively pushing the supply chain to invest better options.

When I asked Target why they would go to this much trouble, they saw the big picture. As Laysha Ward, Target’s EVP and Chief Corporate Social Responsibility Officer said, “We realize that we can leverage our scale, influence and resources to improve the way products come to market and drive transformational change for our business and society.” But again, it’s not solely a change-the-world discussion – Target is seeing real customer demand. As Heiny put it, “It is quite clear that our guest is asking for these products, which is why we’re having these summits.”

In all, Target’s growing focus on the consumer end of the equation demonstrates some key elements of a modern sustainability strategy, including giving customers options that are not just greener, but better; data-driven analysis and transparency; value chain and systems thinking; and radical collaboration with suppliers and even competitors.

Anytime the giants of an industry really start competing and collaborating on sustainability, it’s a very good development. Let’s hope we consumers continue to play a positive role — we may be key to companies making big, important changes.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers