Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1261

August 18, 2015

Microsoft’s Bid to Make Outlook More than Email

Email as we know it is changing—and so is Microsoft’s strategy for its cornerstone product, Outlook. Last week, the company announced partnerships with third-party companies to integrate additional functionalities—including those from Uber, Yelp, Evernote, PayPal, and Boomerang—into Outlook email. These “add-ins” allow Outlook users to schedule an Uber ride prior to a meeting, for example, or send PayPal money through an email, or easily share information to and from Evernote. Most of the features will be incorporated into Outlook 2013 and Outlook Web for Office 365, with more partnerships likely to come. This announcement suggests a shift towards a platform strategy, whereby Microsoft acts as an intermediary connecting third parties with Outlook users.

Many successful platforms today have experienced this product-to-platform transition. Apple’s iPod started as a music-playing device, until it developed the iTunes music store and App Store to connect content providers and app develops to iPod users. Similarly, Google started with a search engine and then introduced search advertising to connect advertisers to users. So what can Microsoft do to ensure that Outlook’s transition is successful?

Re-brand Outlook. Outlook’s transformation reinforces CEO Satya Nadella’s goal to “reinvent productivity.” With third party integrations, Outlook can center its brand not on a product that sends and receives email, but on an ecosystem of services that enhances productivity overall. Microsoft must selectively choose new partners to align with such an identity and build its ecosystem around this core idea. And it should rebrand Outlook to emphasize its evolving benefits.

Outlook may be able to reinvent its business model as well. Because Microsoft now serves two groups—users and third parties—it does not necessarily need to monetize Outlook by charging users. It could eventually turn to third parties to collect a commission fee each time a service is used. Indeed, this is exactly how many other successful platforms (e.g., app stores) have generated revenue. While a product-based strategy might have worked for Outlook on PC in the past, it may take a more platform-based model to be profitable in the future.

Grow mobile. Outlook’s market share still lags behind the default mobile email clients on iPhone, iPad, and Android. While Outlook is available for free on mobile, so are all of its competitors. This will make it hard for Microsoft to convince users to download the Outlook mobile app from the app store. Drawing users away from these convenient default options requires an entirely different email experience, which third parties could help provide. The more value these third parties offer on mobile, the greater the appeal of Outlook’s app and the more users it can attract.

Of course, mobile devices’ smaller screens make it harder to interface with third party services within email and without a strong value proposition, people may opt to use the corresponding standalone apps instead. Third party integrations must be so seamless and flawless that users prefer to adopt them in their Outlook app workflow. For example, Uber could ping users just before an event listed in their calendars to offer them a ride.

Test the waters. If Outlook builds enough momentum with third parties, we can expect Apple and Google to follow suit. Many third parties will be interested in working with Apple or Google, as they have a greater number of email users. The good news for Microsoft is that it has a first-mover advantage, and can evaluate its platform partnerships to decide which third parties should be acquired, which should be exclusively available on Outlook, and which should be more tightly integrated. Microsoft can use this information to learn about user engagement with third parties before its competitors can and evolve Outlook accordingly.

Google Couldn’t Survive with One Strategy

When Google announced the creation of Alphabet, its new umbrella organization that separates Google’s “bread-and-butter” businesses like Google Search and YouTube from riskier or non-core ventures like GoogleX and Google Capital, shareholders rejoiced. As Todd Zenger writes in his recent HBR piece, “Why Google Became Alphabet,” investors were somewhat uneasy with Google’s approach of mixing unrelated investments, acquisitions and businesses, because it appeared to limit transparency, accountability and discipline. There were also branding benefits to the change, as Kevin Lane Keller explained in another article.

But let’s think about Google’s move from a strategic perspective: What does the creation of Alphabet tell us about the company’s strategic motives?

Alphabet, Larry Page writes on abc.xyz—Alphabet’s new URL—stands for two things: A collection of letters that represent language, the substrate for Google’s indexed search results (the company’s mature business). Competitiveness in such businesses is usually driven by scale, efficiency and incremental improvements to stay relevant.

But Alphabet also stands for alpha-bets, i.e. bets on alpha (investment returns above a benchmark). “Betting on alpha” refers to investing in projects which may have a low probability of success, but also very significant upside. Project Loon is such a moonshot project, providing internet access to remote regions by equipping balloons with wireless capabilities.

Page’s distinction brings to life the idea of strategic ambidexterity: a company’s ability of exploring new practices, products and business models while exploiting existing ones at the same time—a capability which is both remarkably valuable and equally hard in practice.

As we write in Your Strategy Needs a Strategy, successful companies in today’s diverse and dynamic business environments do exactly that: they select right approach to strategy and execution for each part of the business—and animate the resulting collage of approaches as circumstances change or each businesses evolves.

So what can strategy-makers learn from Alphabet’s example? Three main things. Alphabet’s new structure:

1. Allows each unit to deploy the right approach to strategy and execution. Many tech companies have innovation- and engineering-driven cultures typical of nimble, improvisatory start-ups. Many have already built maturing, multi-billion dollar core businesses, however. As parts of a business portfolio grow and develop, different approaches to strategy and execution may be needed. As the market leader in online advertisement, AdWords may need to follow a more classical approach to strategy, with greater emphasis on planning, scale economies, and business model optimization; whereas pioneering businesses may need to employ a visionary approach, which stresses speed and persistence in recognizing and addressing an unmet need with a novel product or business model. Fast changing, unpredictable, embryonic businesses may require an adaptive approach which stresses rapid iterative experimentation and organizational flexibility. And some businesses may present an opportunity to deploy a shaping approach, in which an orchestrating company build a collaborative ecosystem around a shared platform. Attempting to apply a single approach to strategy and execution to these very different situations compromises competitiveness and performance.

2. Makes it easier to build the required capabilities in each business.

In order to effectively apply different strategic approaches in different business environments, a company needs also to be able to support each with appropriately differentiated capabilities and culture. The discipline and efficiency focus of classical businesses engender very different needs compared to devolved, free-wheeling adaptive ones, for example.

With its notorious appetite for hiring engineers and computer scientists, its famous “20% time” policy (which allowed employees to take one day a week to work on side projects) and its campus-based community approach, Google has created a highly distinctive culture.

The new modular approach to strategy and organization realized by Alphabet allows it to vary that unique recipe according to the needs of each business. Visionaries, risk-takers and engineering geniuses may fit better with moonshot companies, and disciplined doers, optimizers and commercial types for their more mature businesses for example. It also allows Google to employ different leadership styles and develop different cultural variations for each.

3. Lowers the hurdles to acquiring and growing companies.

An umbrella organization makes forming and buying new businesses a lot easier, too. Transparent reporting will give shareholders what they are looking for. And a modular structure means that integration challenges are minimized. Forming, buying and selling subsidiaries are a hallmark of experimentation by acquisition. An umbrella structure increases a tech company’s flexibility and agility to reshape its portfolio of bets.

Google, now Alphabet, restructured its organization to realize an ambidextrous approach to its business, potentially benefitting both its moonshot projects, its nascent businesses and its mature core business. Google’s move is part of a broader trend towards the “fission” of bloated business structures, as evidenced by the increasing incidence of corporate splits and spins. While other factors, like tax and capital allocation, have undoubtedly also played a role, the need to apply more tailored approaches to strategy and implementation in a more diverse and dynamic business environment has been a key driver. “Separation” is not the only approach to achieving ambidexterity, but it is a very effective one for a business portfolio of moderate complexity and dynamism.

Amazon Is Right That Disagreement Results in Better Decisions

Kenneth Andersson for HBR

When I worked in the federal government, I was amazed at the large numbers of factual errors in widely-read stories, even in the best newspapers. As a colleague of mine, a staunch Democrat, observed in 2009, “I now think that at least half of the things I most disliked about the Bush Administration . . . never happened.”

I tell this little tale because the lengthy New York Times story, detailing some apparently brutal features of the culture at Amazon, should be taken with many grains of salt. But even if the story is full of inaccuracies, and if we put the company’s alleged harshness to one side, Amazon’s approach offers indispensable guidance for companies both large and small when they are deciding how to make group decisions.

The story suggests Amazon places immense importance on defining team players not as people who go along with the group’s consensus, or who support the status quo, but instead as those who add new ideas and perspectives. The company evidently prizes those who overturn workplace convention, as signaled by the term used on the award given to high-performing employees: “I’m Peculiar.” To be “peculiar” is to break with convention, in the sense of generating fresh perspectives and (potentially) significant reforms.

In short, Amazon discourages conformity and combats groupthink. Bosses do not just give feedback; they receive it. Disruptive thinking is welcome. Conflict and innovation are thought to march hand-in-hand. One of the company’s core principles advises employees to “disagree and commit.” The theory is that “harmony is often overvalued in the workplace” and “that it can stifle honest critique and encourage polite praise for flawed ideas.” Low-level employees are strongly encouraged to make major contributions. In discussions, high status is not believed to be a guarantor of correctness.

In emphasizing that harmony is often overrated, and in valuing disagreement and internal scrutiny, Amazon is acting consistently with the principal findings of decades of research in behavioral science. That research has shown that many groups, including businesses, do poorly, or at least less well than they should, because they do not take advantage of the information and the creativity of their own staffs. Led by confident (but closed-minded) leaders, they establish policies and practices and then they execute – but without sufficient internal scrutiny, either before the fact or on a continuing basis.

Of course Amazon has the advantage of an extraordinary amount of data, allowing it to explore, on the basis of evidence, what works and what doesn’t. But by itself, data can be inarticulate. It needs human beings to make sense of it, or at the very least to try to figure out what sense it makes. Amazon puts a premium on sense-making. To the extent that a company takes self-conscious steps to elicit creativity and honest critique from its own people, it is likely to avoid groupthink and to do far better than it otherwise would – and to make more effective decisions than companies that overvalue harmony and do not focus explicitly on how to produce informed judgments.

This particular story, however, has an apparent dark side, which is garnering most of the media attention. According to the article in the Times, Amazon’s excellent practices, counteracting consensus and complacency, are accompanied by a culture that is not merely ultra-competitive but also unforgiving, harsh, and sometimes even cruel. Whether or not that’s so, it’s crucial to see that good companies can encourage internal disagreement, and reject the supposed virtue of harmony, while also treating their employees with courtesy.

Wise companies can do both well and good. They do well because they take full advantage of the ideas and imagination of those who work for them. They do good because they never embarrass or humiliate their own people. Recognition of the dignity of each and every employee underlies the belief that harmony is greatly overrated – and also the belief that each and every employee should always be treated with respect.

August 17, 2015

7 Tips for Managing Freelancers and Independent Contractors

When people work for you, you want to do right by them. But the rules and expectations are different when you’re managing a freelancer who isn’t fully employed by your company. How do you best motivate someone who you don’t have formal authority over? How do you keep them interested and excited about the work when they don’t get perks like bonuses or benefits? Should you give them performance reviews so they know where they stand?

What the Experts Say

Many managers assume that they don’t need to tend to freelancers as much as they do regular employees—and there’s some truth to that, says Dan Pink, author of Free Agent Nation and Drive. “The relationship is often less fraught, less hierarchical, and doesn’t come with the same expectations,” he explains. But that doesn’t mean that you can be completely hands off. You still need to actively and thoughtfully manage them so that you can get their best output and ensure they’ll want to work with you again. “There’s a growing war for talent for people with specialized skills,” says Steve King, a partner at Emergent Research. Freelancers are often just as valuable as full-time staffers, so employers need to treat them accordingly. Here’s how to successfully navigate your relationship with contractors.

Understand what they want

The first question you need to ask is: Why are they interested in doing this job? “It could be money, the chance to develop new skills, or the opportunity to work with great people,” says Pink. “What are you giving that person in exchange for lending his or her talent to your organization?” Because you won’t know freelancers as well as the people on your team, you may need to put this question to them directly. (“Just asking is a woefully underused technique in life,” says Pink). You might say, “Tell me what you’re hoping for from this assignment.” Then make sure you’re delivering on that.

Set expectations

At the same time, you need to be clear about what you want in return—whether it’s a well-designed brochure, a new website, or advice every two weeks. It’s good practice to draft a statement that details exactly what you need and when. It’s also important to provide them with context. Because freelancers aren’t around all the time, “they’re not getting the purpose of the exercise through osmosis the way your employees are,” says Pink. “You have to spend extra time talking about what the goal is, how it connects to the big picture, and why it matters.”

Build the relationship

“It’s fair to say you don’t have to invest as much in a freelancer as you do as an employee,” says King. But, “don’t fall into the trap of making it purely transactional,” warns Pink. Get to know them by asking questions about their family, what they’re interested in outside work, and the other projects they’re working on (assuming you aren’t their only client). This is especially important if you want to work with this person again in the future.

Make them feel part of the team

King’s recent (and not yet published) research on freelancers shows that they prefer to work for employers that treat them like part of the team. So try to avoid all the subtle status differentiators that can make contractors feel like second-class citizens—for example, the color of their ID badges or access to the corporate gym—and be exceedingly inclusive instead. Invite them to important meetings, bring them into water-cooler conversations, and add them to the team email list. Compliance departments in some organizations might worry that doing these things makes freelancers look too much like employees for legal and tax purposes, and managers certainly need to be careful not to overstep any employment laws or HR guidelines. But, King notes: “There’s nothing that says they can’t come to a team lunch.”

Don’t micromanage

Your contractors likely got into freelancing because they wanted autonomy. King and Pink agree that it’s important to give them freedom. “To be a successful freelancer, you need to be self-motivated and able to work without someone looking over your shoulder,” says King. Be flexible with their schedules and other commitments. You’re likely not their only client. And give them space to do their work. “You shouldn’t have to manage the work product of a contractor. If you are, find another one,” he says.

Give feedback

There’s no need to do a formal review with freelancers (“I’m not even a big fan of giving employees performance reviews,” admits Pink) but that doesn’t mean you should skimp on the feedback. Telling them what you think of their work will improve their performance and deepen the relationship. “Besides, most freelancers are starving for that kind of input,” says Pink. It can be as simple as spending five minutes at the end of an engagement discussing what went right and what went wrong but King says continuous feedback is even better. “Regularly revisit the statement of work or contract and be clear about whether they’re hitting their targets,” he advises. “If they’re doing a good job for you, thank them, especially in front of others.” And, if they’re underperforming, don’t beat around the bush. “It’s easy to say shape up or ship out partly because you can boot them at any time and you don’t have to feel as badly about it.”

Pay them well

Don’t think just because the contractor is work-for-hire that you should take advantage. They deserve to be treated fairly. “Pay them market rate,” says Pink, “and if you value their work pay them more.” Even if you’d like to test the person out before committed to a big project with her, avoid asking for work on spec; offer to pay for the time the “tryout” takes. “People talk to one another,” Pink warns, and you don’t want to risk getting a bad reputation. Your company should “aspire to be an employer of choice—for regular and 1099 employees.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Ask what they are looking for from the arrangement

Invest time in getting to know them

Make them feel like they are part of the team and that their work is valued

Don’t:

Neglect to give them feedback on how they’re performing

Assume yours is the only project they’re working on—freelancers often have multiple commitments

Skimp on paying them what they’re worth—you’ll get a reputation and other contractors may be unwilling to work with you

Case study #1: Be sensitive and flexible

Nick Hales, an IT manager at AOMi Ltd based in Reading, U.K., has hired freelancers—mostly software developers—for 15 years. He’s used them for both short, three-month stints when his company needed extra capacity as well as for more involved, specialized projects that have spanned years.

While he acknowledges that there are some key differences in how you manage employees and contractors (“I would never give a freelancer a formal performance review, for example,” he says), he believes they should be “treated as equals in terms of professional respect and decency.” He always provides ongoing feedback to the contractors he works with, and for those that he wants to keep around, he’s open and honest about what work might come up in the future so that they don’t get “uneasy about their position and leave.” He also makes an effort to make them feel part of the team and invites any active freelancers to the company Christmas party.

One key difference in how he interacts with freelancers is onboarding. “Contractors need to hit the ground running and so often need—and appreciate—a clear steer on what is expected,” he explains. “I’m always more firm at the start of an engagement with them than I am with new permanent employees, who you can shape and mold over time.

Still, he makes sure to ask questions and understand their goals, habits and schedules too. “I always take a collaborative approach. Contractors are human, they have lives and they have external demands. Work with people in a flexible manner and they will work with you,” he says.

Case study #2: Know what they want

Sumeet Goel first starting hiring contractors in 2002 when he founded HighPoint Associates, a firm that draws from a network of independent consultants to staff client projects. The company now has two offices—one in Los Angeles and another in New York City—and works with over 100 freelancers each year.

The key to managing such a large and diverse group of contractors, Sumeet says, is a personal approach. “We’re very high touch.,” he explains. “Individual freelancers can often feel like they’re operating in a vacuum” so you want to emphasize that they’re a valued part of a team and not alone on the project. Everyone who works for his company knows that he or one of his partners will always be available to bounce ideas off of—whether that’s in a weekly call or less frequently. The contractor determines what level of support he or she needs.

Sumeet also respects their time. “Freelance consultants typically have a lot of other things going on,” he says. So he is flexible about their schedules and makes sure they can see to their other commitments. And he’s very conscientious about paying them promptly. “Our payment structure is something our contractors value most. We pay our freelancers on a net 30 day basis, irrespective of whether the client has paid us or not,” he explains.

Another way Sumeet keeps his consultants motivated and focused is by “stressing how important their work is to us, our company and our client” and by figuring out and emphasizing the aspects of the relationship that are most important to each individual. For those who crave a sense of security, he may point out that the company has more work coming down the pipeline. For those who appreciate clear project end dates, he outlines the off ramp for the work.

What Separates Great HR Leaders from the Rest

HR seems to have become every manager and employee’s favorite corporate punching bag, vying with IT for the dubious title of most-irritating function. We have seen a parade of articles recently calling for HR to be blown up, split in two, or at the very least, redesigned.

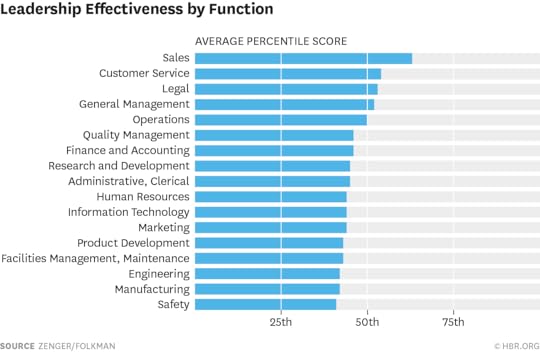

Perhaps this is a good moment to evaluate what it is we really want from our HR leaders—and what we don’t. Over the last five years, Zenger Folkman has collected 360-degree feedback data on 2,187 HR leaders. These leaders are spread across hundreds of different organizations with 68% of those leaders located in the US, 11% in Asia, 8% in Europe, 7% in Latin America, 4% in Canada, and 1% in Africa. Comparing assessments of leaders in the HR function with those of leaders in other functions, our data suggest that the typical HR leader is seen as is six percentile points below average.

We analyzed the data in two different ways. First, we contrasted the results for the 2,187 HR leaders in our dataset with those of 29,026 leaders in other functions. We were able to identify a few key skills that were common strengths of those in HR and some that appeared fairly frequently as weaknesses. Second, we rank-ordered 49 leadership behaviors for all those in HR from the most negative to the most positive behaviors.

Strengths of HR Leaders

Developing and coaching others. One of the most positive areas for HR leaders in general was that they were truly concerned about developing others. This set them apart from leaders in other functions, who did not score highly on this skill. They were also rated positively on providing coaching, acting as a mentor, and giving feedback in a helpful way.

The 16 Key Leadership Skills

Great outcomes are connected to 16 leadership competencies that span five

categories:

Character:

1. Displays honesty and Integrity

Personal Capabilities:

2. Exhibits technical/professional expertise

3. Solves problems and analyzes issues

4. Innovates

5. Practices self-development

Getting Results:

6. Focuses on results

7. Establishes stretch goals

8. Takes initiative

Interpersonal skills:

9. Communicates powerfully and broadly

10. Inspires and motivates others

11. Builds relationships

12. Develops others

13. Collaborates and fosters teamwork

Leading change:

14. Develops strategic perspective

15. Champions change

16. Connects the group to the outside world

But is this skill valued by HR leaders’ colleagues? We asked raters to indicate the importance of each competency we measured, and they rated this skill eleventh of 16 for HR leaders. Perhaps the message here is, “We know you do this well already” or even “This is just table-stakes.” Or, it could be that developing others takes a back seat to other competencies that are highly valued by the other functional leaders.

Building positive relationships. This was another skill where HR scored much more highly than other functions. That makes sense; in most organizations HR is responsible for diversity and inclusion initiatives and for labor relations. HR leaders were rated well on being able to “balance results with a concern for the needs of others.” Another of their more positive items was being trusted and staying in touch with the issues and concerns of others. This competency was also more valued by our raters, who chose it as third in importance.

Role modeling. Some of the most positively rated items for HR leaders focus on their willingness to “walk the talk,” to be role models and to honor commitments and promises. HR leaders are frequently put into the position of ensuring that others in the organization do the right thing and follow established procedures. For those in the HR function, this competency is rated as second in importance. It’s also a skill that seems to be fairly common across all functions.

Having functional knowledge and expertise. Many HR leaders were rated positively on their functional knowledge and expertise. Most employees in organizations are unaware of labor laws, hiring rules, benefits and compensation issues. HR leaders were viewed as knowledgeable and helpful in these areas. This was another common skill across functions, and was rated as ninth in importance for HR leaders.

Weakness of HR Leaders

Focusing internally rather than externally. When comparing HR leaders to all other leaders in our database, they were rated significantly more negatively on their ability to understand the needs and concerns of customers. In many ways the function of HR is focused on internal problems, but the lack of understanding of the external environment often caused others to view some HR leaders as not in touch with the issues facing the organization. HR leaders were also rated more negatively on their ability to represent the organization to key groups.

Lacking strategic perspective. In general, HR leaders were rated significantly less positively on their ability to have a clear perspective between the big picture strategy and the details. Many were viewed as so focused on the “day-to-day” work that they lost perspective on the longer term broader business issues. HR leaders often complain that they “want a seat at the table” to engage more fully with other executives, but without clear strategy and focus they will never have that seat.

Not anticipating and responding quickly to problems. HR leaders were rated significantly more negatively on their ability to anticipate and respond quickly to problems. A number of items noted a general lack of speed and urgency to respond and react quickly.

Resisting stretch goals. On a number of occasions we have watched as senior executives ask for a program or process to be rolled out quickly only to have HR respond, “It takes more time than that—we need to slow the process down.” While at times that is necessary advice, too often it is the first response given by HR without considering what could be done to speed the process and move quickly.

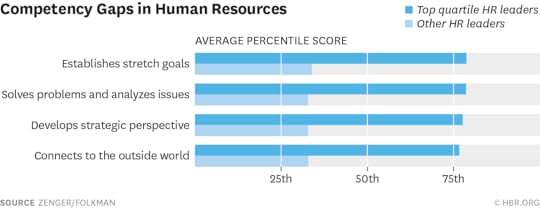

What the Best HR Leaders Do

We also found in our database that some of the best leaders in the world were part of the HR function. The graph below shows the four competencies that most consistently separate the top quartile leaders from the other HR leaders. It is worth noting that what separated the best HR leaders from the rest was their performance on the key competencies that were often weaknesses in HR, in addition to performing extremely well on HR’s traditional strengths.

If more HR leaders would add these four important competencies to their skill sets, we would see many more sitting at the table; and an increasing number seated at the head of the table.

Authors’ Note: There’s an interesting gender wrinkle in our data, although we’re not quite sure what to make of it. According to our data, HR has the highest percentage of female leaders (66%). Overall, female leaders were rated at the 45th percentile while male leaders were at the 43rd percentile, but at the very top levels it flipped, and the senior-most men in HR were rated more highly—male senior leaders were rated at the 52nd percentile, and female senior leaders at the 47th. These differences, while small, are statistically significant. When we look at the overall data for male versus female senior managers in the other functions, males are at the 48th percentile and females at the 53rd. Only in HR, Engineering, and Safety do male senior leaders score higher than their female counterparts.

Admitting You Don’t Know, When You’re the CEO

Frank* quite simply doesn’t know what to do. The newly named CEO of a highly regarded publishing company, Frank is a print guy through-and-through. He spent twenty years working his way up through the editorial side, and is excited about the challenge of bringing the company’s great content into the 21st century. In fact, he knows one of the reasons the board has chosen him to replace the retiring CEO is his focus on finding new outlets and platforms for the organization’s wealth of content.

Now, though, he’s sitting in a meeting of his direct reports and their direct reports, and Anne-Marie, his head of digital, is talking about how they should partner with social sites to syndicate their content in ways that could garner both license fees and advertising rev-share…and Frank has realized that he doesn’t really understand what she’s talking about.

Should he ask a question that will reveal his lack of knowledge to his top 30 executives? Or should he say nothing and hope his gap in understanding doesn’t trip him up later in the meeting?

Being a CEO has always been a challenge: everyone looks to you for direction and clarity, and it’s your responsibility to set the tone—philosophically and practically—for the entire organization. And your board and shareholders, if yours is a public company, are expecting you to guide the enterprise to sustainable financial success.

As if that weren’t challenging enough, over the past decade it’s gotten even harder. The ever-increasing pace of change has brought with it the need to find new ways of operating and the ability to understand and incorporate new technologies on an almost daily basis.

Frank’s dilemma arises out of this new pressure, and is common to almost every CEO today: How can I demonstrate that I’m capable of leading the company into the future when there’s so much I don’t know? And how can I find out what I need to know without looking incapable?

The good news is it’s possible. We’ve seen in our work with leaders that some of the most highly respected CEOs and senior executives are also the best at revealing their “noviceness” and opening themselves up to acquiring the emerging skills and knowledge most necessary to their success. In fact, research increasingly supports the idea that CEO openness to and about new experiences is highly correlated with organizational effectiveness. Here, then, are the keys to being successful as a novice when you’re sitting in the big chair:

Be great at the core of your job: My business partner is extraordinarily good at what he does. I’m impressed every day with how he builds relationships with our clients and how he supports them to lead well and to be ready for the future. Because I have such respect for him as a highly capable person, when he says to me: “I don’t understand thing X—can you explain it, or do you know someone who can?” I don’t start assuming that I’ve been wrong all this time, and he’s not really very good or smart after all—I assume that this is why he’s so good, that he has built his expertise by being open to learning in areas where he’s not yet expert. If a leader starts by demonstrating that he or she is excellent in many of the core skills and capabilities needed to lead, the people surrounding that person will have confidence that he or she will be able to learn the rest of what’s needed, and will see that person’s openness to learning as a positive thing.

Recognize the inevitability of “being bad first”: Frank’s hesitation to reveal his lack of knowledge arises from a nearly universal human longing: we love to be good at things. Especially once we get to be adults and have experienced some level of mastery, we don’t ever want to go back to being novices. Sadly, though, every time we need to learn something new, we’ll be bad at it when we begin. That’s just how it works. When you’re attempting to understand or get good in a new area of skill or knowledge, you’re going to feel clumsy, make mistakes, have to ask 101-level questions.

You can’t change that reality, and given how quickly everything is moving now, you can’t avoid having to learn new skills. But you can make the process a whole lot easier by simply accepting it; by telling yourself, I’m going to be bad at this for a while until I get good at it.

Recently I shared this approach with a client of mine who was having to learn a new way to manage his company’s supply chain—and was both resistant to and embarrassed by his lack of understanding. However, as soon as he was able to shift his mindset into “accepting being bad,” he told me it was almost like setting down a physical weight—that simply acknowledging and accepting the reality of his novice-ness made him feel immediately less pressured, more capable and hopeful. He told me later that he felt as though “the static in his head had quieted down,” and he was able to pick up on what he needed to understand much more quickly than before.

Get good at being a novice in public: This is where the rubber meets the road for a CEO. Having to show your noviceness in public when you’re wanting to be seen as a competent and powerful leader can feel awkward and even a little scary. However, if you can be courageous enough to ask that first “novice” question in public, I can almost guarantee you’ll find your fears aren’t justified. You don’t have to throw up your hands and admit you have no idea what’s going on. You just need to ask people to walk you through what they’re saying step-by-step.

For instance, our new CEO Frank might take a deep breath and say to his head of digital, “I’m not sure I’m following you—could you explain that in a different way?” I’m sure when he does, his heart rate will accelerate a bit, and he’ll wonder if he’s made the right choice. But then she’ll stop and say, “Oh, sure. It’s what we’ve found out from some of the one-off deals we’ve done with Facebook and HuffPo for our articles. How it works is…” Frank will listen and understand, Anne-Marie will feel important and helpful, and the trust and openness on his team will tick up a few micro-points.

In other words, nothing bad will happen and a number of good things will happen. That will make it much easier for him to “be bad” the next time, and the next. Word will get around that he’s really interested in his people’s point of view and willing to learn from them, better conversations will happen, and his employees will start to ask curious questions in their own meetings. Learning in his organization will accelerate, and they’ll be able to shift their business in the fundamental ways that will allow them to succeed long-term.

*Name and some details changed.

Use Your Customers as Ethnographers

Several of the great success stories of corporate ethnography have 3M engineer Richard Drew as their protagonist. In the 1920s, Drew spent several days at an auto assembly plant, observing how the workers were using his company’s sandpaper. Two-tone cars were all the rage at the time, and Drew serendipitously noticed that the plant workers were laboriously and often unsuccessfully using newspapers to shield the painted portion of the car while the second color was applied. That alerted him to a need and ignited the idea for what became 3M’s keystone product: masking tape.

When it comes to discovering unmet customer needs and innovation opportunities, there’s no substitute for in-the-moment, in-context observation for making meaning out of the complex weave of emotion and rationality that drives consumer behavior. That’s why ethnographers often follow subjects around or even temporarily move in with them to note the compensations, workarounds, and rituals associated with some specific product, task, or routine.

But unless ethnographers are willing to spend weeks on end with their subjects, their presence inevitably introduces some behavioral change in the people they’re observing. After all, if you’re a teenaged girl, are you likely to buy condoms for your boyfriend with an ethnographer tailing you around? If you’re her mother, might you hold back from purchasing those Cheetos or Oreos, or hesitate to strip off your bra the moment you get home from work? If you’re her father, will you be tempted to tune into NOVA instead of the latest episode of Hoarders?

At the same time, technologies like selfie sticks, Fitbits, and wearable video cameras are making people comfortable monitoring their own calorie consumption, sleep patterns, heart rate, friends, family, and daily experiences. This is leading some companies to investigate whether they can obtain comparable or at least good enough ethnographic insights in faster, cheaper, and more scalable ways by using simple mobile ethnography apps to equip people to observe themselves. These apps typically enable people to upload media files, tag their location, and provide brief responses to open- and closed-ended questions that are tailored for each project.

Why use them? At C Space, we’ve conducted more than 800 mobile journaling and ethnography projects on behalf of over 240 clients since 2010, and have seen the power of bringing consumer experience to life for our clients. Product and package designers can see how people open, store, and use their purchases “in the wild.” Manufacturers and retailers can jointly learn what shelf sets, aisle layouts, signage, and promotions are capturing attention and changing shoppers’ behavior in the moment. Marketers and innovation specialists can immerse themselves in the sights, sounds, and emotions of consumers’ daily lives, surfacing opportunities to make their products and services more emotionally resonant and durable. Customer experience initiatives can benefit from longitudinal studies capturing consumers’ every touch point with the brand.

In myriad tangible and intangible ways, consumers’ self-ethnographies help employees throughout an organization get to know customers as real human beings, not merely as data points. And that living, breathing knowledge builds corporate empathy, which, we’d argue, is ultimately the key to business growth.

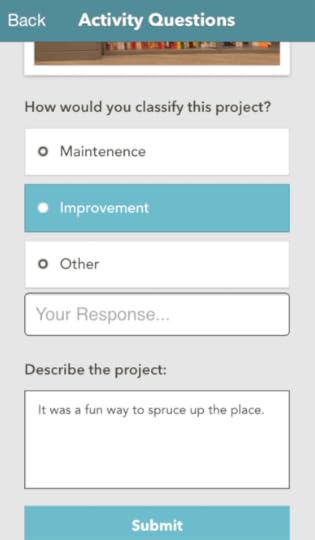

But to achieve these benefits, mobile ethnographies must be well designed. (The screenshots below, from our mobile ethnography app at C Space, give a sense of how this sort of activity is captured.)

One of the biggest challenges companies are finding in getting their customers to become their own ethnographers is that it’s difficult to remember to step out of the moment to capture it. We’ve found that companies have greater success getting people over that hurdle when they give people short, focused assignments, particularly those that capture moments of strong emotion.

For instance, consumer insight specialists for Procter & Gamble’s Secret asked a number of women to use our mobile ethnography app to upload photos or videos illustrating the scents that brought them pleasure over the course of a week, and then to write a few sentences explaining what these pictures meant to them. The resulting images of Play-Doh, newly painted birdhouses, and freshly mown grass led product developers far from the types of scents normally associated with deodorants and antiperspirants. The stories accompanying these pictures highlighted the ways in which, over the course of an ordinary day, the women appreciated the power of scent to fleetingly elicit other times and places. That insight drove the development of a new sub-brand for the Secret line, Destinations, which promises scents that evoke locales and seasons. Not only did Destinations advance from insight to concept development to market launch in record time, but it exceeded its sales forecasts.

Similarly, to help market researchers understand the effectiveness of store layouts, we asked people to document what captures their attention or changes their behavior when they are in the grocery store. Some assignments focused on a particular product, as when we asked people: “On your next trip to buy toothpaste, show us what confuses you, surprises you, annoys you, or simply captures your attention in the oral care aisle.” In another, designed to explore what prompts people to make impulse purchases, we asked consumers to submit photos and narratives showing us what was on their shopping list, what captured their attention in the store, and what unplanned purchases they ended up making.

In both cases, the assignment was clear, the duration short but intense. Asking for images enabled us literally to see what is breaking through the visual noise of the aisles. Connecting those images to participants’ reflections on why they deviated from their plans or routines and why they made the impulse purchases they made adds a depth and texture that we could not have gotten had we asked participants to rely on their memory sometime later in a survey or even if we’d sent a professional ethnographer shopping alongside them.

“But isn’t this atypical of the normal shopping experience,” the seasoned market researcher might object? And it’s true – asking consumers to install a smart phone app to chronicle and interpret their own processes and rituals falls outside the realm of normal behavior. Still, that doesn’t invalidate the insights that spring from this approach. In fact, there are unique benefits to this kind of enforced mindfulness for researcher and subject alike, especially when they are one and the same person.

“I thought I mostly bought healthy food until I photographed what was in my pantry and refrigerator,” one consumer told us. “Now I’m wondering if I can’t figure out what’s healthy while I’m racing through the grocery store, or if I’m just lying to myself.” That kind of epiphany is gold for the manufacturer of food or, in this case, of weight loss products, informing the design and content of consumer education and behavioral support materials. But it can only happen when the consumer is both a participant and observer of her own life.

While the assignments might be specifically focused in support of a specific product or project, the insights gained from this kind of emotional self-reportage can resonate with creative professionals, marketers, and researchers across a company. That’s what Hallmark found when it turned to self-ethnography to yield a deeper, more empathetic and more individualized understanding of the 85 million+ American moms who are so essential to the Hallmark brand. “We hope that experiencing their real moments will help Hallmarkers recognize that our core consumers aren’t ‘moms with kids,’ but are real individuals,” observes Nancy Cox, Hallmark’s manager of consumer understanding and insights (CU&I).

With that goal in mind, the greeting card and media company equipped members of its long-established online consumer communities of women advisers with a simple ethnography app, which they used to conduct a variety of projects.

When asked to record the sounds of daily life that made them happy, for instance, they generated hundreds of submissions over the course of a single, wonderfully noisy week. They used their phones to record and upload thumping washing machines; the whirr of dishwashers; the opening door signaling someone’s return home; and, of course, laughing babies. What became apparent from their accompanying commentaries was that all of these sounds created happiness, or at least satisfaction, for these women, many of whom were juggling families and work outside the home. They created a feeling that no matter how demanding or volatile other aspects of their lives were, things were at least operating as they should within the domestic world in which they had some measure of control.

These sounds were then used as ambient background in an immersive exhibit at the company’s Kansas City headquarters entitled “Real Moms, Real Moments.” Created by the CU&I team and designed to inspire creative professionals, marketers, and researchers, the exhibit, which more than 600 Hallmarkers toured over a three-week period, featured an array of interactive, sensory-rich simulated areas of a consumer’s home. For example, by “answering” phones, exhibit visitors heard moms describe the differences that make a house a home. Hearing these women talk about the aromas, sounds, and warmth of a home helped further humanize their words.

Employees were also invited to sit in a comfortable chair while browsing excerpts from multimedia diaries of 20 moms who used a mobile app to record their thoughts and experiences during the course of a workday and a non-workday. The serendipitous input — one mom raving about Bollywood theatre, another sharing the fact that she was pregnant and afraid to tell her family because of heartbreak from a prior miscarriage – illustrates the intimate, contextual nature of this approach.

Beyond sights and sounds, ethnography apps also generate GPS location data, which some companies have used to discover some surprising insights. For instance, a major toy manufacturer developing an app to provide parenting tips asked women to share moments of success (children’s problems solved, crises averted) and moments in which they were desperate for suggestions and help. Contrary to the hypothesis going in, the project revealed that the parents’ moments of need arose not outside the home — like, say, when the child was having a temper tantrum in the mall — but inside — when they were trying to come up with a new hairstyle for their fashion-conscious daughter or cook a meal that their picky child would actually eat.

Hospitality companies are also deriving quick, highly actionable insights by combining GPS information with the experiences and rituals that travelers and guests are recording and sharing with them. How far from the hotel do solo travelers tend to go at night, and how does that differ by gender? What do frequent travelers do when they first check in to their rooms? Some lay out their toothbrushes on facecloths so that they need not touch the counter (suggesting that hoteliers should either provide toothbrush stands or reassurances about their hygiene practices). Others inspect the walls and ceilings for leaks. Indeed, the video one nonplussed man shot of the creepy stain behind his bed almost put Psycho to shame. The geo-tracking data that came with it enabled our client to identify the specific property in need of some fast upgrades.

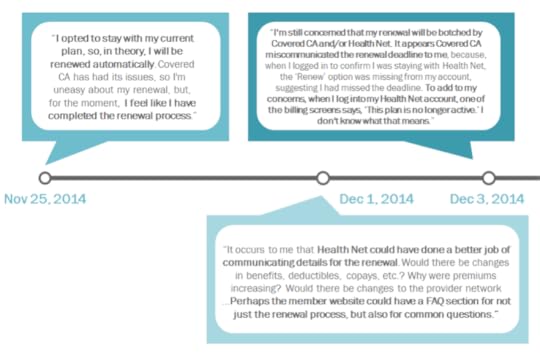

Longitudinal data can be as, if not more, valuable than actual longitude. For example, California health-insurer Healthnet enlisted 40 of their online community members to document their insurance renewal journey over the course of three months during the 2014 Open Enrollment Period. While technically more of a diary than an ethnography exercise, this project illustrates the benefits of having long-term relationships with consumers who are equipped with ethnography apps and willing to share some aspect of their lives in an ongoing way. Take a look at the accompanying timeline below (which is in no way unusual – we’ve collected dozens like it), and you can see how the customer experience can change dramatically over time and how clearly it suggests opportunities for improvement.

“While we’ve always paid attention to our internal processes, this approach allowed us to hear and directly witness our members’ emotional as well as operational experience,” explains Guy Hadnot, Healthnet’s Director of Customer Experience. “And what we learned was sobering. We found that our members didn’t so much actively renew as just “stay” with us, and largely because of price. They were apathetic renewals, not actively positive ones, which meant that they’re at-risk renewals.”

Healthnet acted quickly and systematically on this insight. They shared out the findings from this in an immersive, internal cross-functional Action Setting workshop, where they mapped out changes in advance of the 2015 Open Enrollment period. Healthnet hopes that on the strength of the insight gathered through this longitudinal process, they’ll retain and expand the company’s member base despite an increasingly competitive pricing environment.

“You just can’t get this depth of insight in a one-off focus group or survey,” Hadnot notes. “And the icing on the cake is that even after the renewal journey was complete, thanks to the ongoing relationship we had with them, we could partner with our members to help us improve the process.”

Having consumers chronicle and interpret their own lives helps to mitigate the embarrassment potential of being observed by a stranger, face-to-face in real time. But it can nonetheless feel invasive to know that intimate data – what you’re seeing, where you are, how you feel — is being collected, often by people you’ve never met. So just as in live ethnography, researchers have to earn the trust of the people from whom they’re hoping to learn.

But how do you do that? Playback and dialogue turn out to be key success factors. The diligent and often intimate disclosure by citizen ethnographers should never be transmitted to a black hole, lest once-willing “subjects” quickly feel unacknowledged. What’s more, when consumers document their days for remote researchers, it’s crucial that we close the loop, testing our interpretations with them. Saying “Here’s a pattern we’ve observed” not only demonstrates the kind of reciprocity that’s inherently motivating but helps us understand if we’re drawing valid conclusions.

Family members, friends, and others in the “subject’s” immediate circle can also provide a reality check. When consumer-ethnographers fall victim to the quest for “social desirability,” presenting themselves as healthier eaters, more frequent exercisers, or more disciplined shoppers than they typically are, we can ask them to pass the phone to their spouse to comment on the accuracy of what’s being reported.

Ultimately, the outcome of consumer-conducted ethnography is not just to reveal unmet needs and innovation opportunities, but to humanize customers for the brands that serve them. And you don’t need a Ph.D. in anthropology for that; anyone with a smartphone and a sincere desire to learn from can do it.

How to Handle Negative Feedback

There’s no shortage of advice about how to react to negative feedback. Whether the critic is a boss or a co-worker, the same familiar guidance is consistently presented: Listen carefully, don’t get defensive, ask for time.

There’s nothing wrong with these three suggestions, of course. But at the moment when an unhappy colleague is telling you loudly that the project plan you created left out some obvious key components, or your boss is taking you to task for the stumbles you made in running an important meeting, it’s hard to recall these valid pointers, move them to the front of your mind, and actually act on them.

Here’s the point: unless you have spent a little time in advance thinking about what you’ll do the next time that—fairly or foully—someone delivers some unexpected criticism, all the good advice you’ve heard about how to react won’t come immediately to mind. Unprepared, you’re likely to be so caught up in the immediacy of the moment that you won’t remember these three simple, familiar prescriptions that allow us to keep control and to master (or at least, defuse) the situation. So they bear repeating, and thinking through now—so you’ll be prepared in the heat of the moment.

1. Listen carefully. First, there’s no question that not interrupting and listening carefully is the right thing to do when you’re getting negative feedback. That’s familiar counsel. What’s often left undiscussed is the question of what, exactly, is it that you should be listening for?

There are several good reasons to remain silent when you’re on the receiving end of negative feedback. Of course, you want to understand exactly what the criticism is before you react to it. But you need to be listening for other things, too.

First, is what’s being said fact or opinion? That you didn’t include some components in your project plan is a fact. That you ran a meeting poorly is an opinion. Both may be accurate, but sorting out facts from opinion while you’re listening will make it easier for you to respond effectively.

Next, is it accurate? Distinguish the accuracy of the feedback from the quality of its presentation. Few people are skilled at presenting criticism in a way that makes the recipient feel comfortable accepting what’s being said as worthwhile information and learning from it. I often hear, “It wasn’t what she said, it was the way she said it.” OK, the way she said it was harsh and callous and insensitive. But is she right? Even though negative feedback may be badly delivered, it may be accurate.

Further Reading

HBR’s 10 Must Reads on Communication

Communication Book

24.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

What’s the intent? What’s the motive? If the person who’s giving you feedback is someone who’s usually trustworthy and reliable, this is feedback you’ll want to pay close attention to. If the individual is egotistical, or is into one-upmanship, or has a tendency to dramatize, you should still be professional and listen to what’s being said. But consider the source, and take it with a grain of salt.

2. Don’t get defensive. When the other person’s criticisms seem inaccurate, ill-informed, petty, irrational, or just plain weird, it’s easy to become defensive. Even when your criticizer is factually wrong, the response “You’re wrong!” won’t ever be helpful. Not even if you can prove it.

It’s in our nature to listen defensively. As the other individual is giving us a dose of negative feedback, we tend to listen not to understand what’s being said, but to spot distortions or inaccuracies or faulty conclusions. We listen so that we can refute errors or justify our actions or prove the other individual wrong.

But even if the negative feedback we’re getting is demonstrably wrong, it’s not in our best interest to immediately try to prove it. Try to prove someone wrong and we become argumentative. We’re close-minded to the useful information that may be hidden in the poorly presented feedback.

The key is to listen to the other person without planning our reply. Simply nodding until the other person has completely finished will make sure that your counterpart has said everything intended.

Asking questions helps eliminate the appearance of defensiveness and keeps us from immediately jumping in to justify our actions. Ask, “I want to be sure I understand what you’re saying. Do I have it right that you feel . . .” That question can help the other individual communicate clearly whatever his or her core message may be. Asking for examples may help you gain useful insights that are buried in the unconstructive message.

3. Ask for time. Unless the negative feedback concerns something that is right-on-the-spot fixable, it’s good to ask for time to consider what your informant has told you. This provides several benefits. It defuses the immediate situation. It tells the other person that you consider their feedback important enough that you want to consider it carefully and calmly. And it allows you to think through the accuracy of what you’ve been told, perhaps testing its validity with others.

Saying something like, “I appreciate your feedback. I’d like to give what you’ve said some real thought and get back to you,” and then adding, “Is there anything else I should know?” will demonstrate that you take what you’ve been told seriously and will ensure that there’s been nothing left unsaid.

Asking for time also helps defuse the emotional load. Say, “This is important. I want to talk with you about what you’ve told me, but right now I’m overloaded/distracted/feeling defensive. Can we get back together tomorrow morning?”

In that following conversation, whatever explanations or defenses you offer will be more carefully considered than if they were blurted out right after the negative message was received. Once the other party feels heard and understood, it’s much more likely that the criticism will be put in perspective by both giver and receiver. Once you fully understand the negative feedback that’s been delivered, it may be appropriate to offer an apology.

But then, close it off. Don’t over-apologize. Apologize once if necessary, sincerely and maturely. Remember that criticism and negative feedback are a fact of life. Learn from your mistakes, and move on.

What You Might Not Know About the Cuban Economy

On the front page of a Cuban newspaper recently there was an item about a two-story home in the old city of Havana that crumbled—and that in the course of its collapse, killed four people. This is a harsh glimpse the physical reality facing many of the buildings across Havana and elsewhere in the country. But it’s also a metaphor for much of the Cuban economy. Cuba is, in many ways, an economy stuck in time and at risk of further unraveling.

Cuba’s economy got a jolt in December 2014, when U.S.-Cuban ties were restored. The U.S. embassy in Havana has reopened. Some travel is easing. Pope Francis will visit in September. So on the surface, it might appear to be full steam ahead for business and beyond. But in order to understand where Cuba may go, we need to understand where its economy, its people, its governance, and its marketplace have been.

Cuba’s growth domestic product per capita in 2015 is approximately what it was in 1985. The short version of Cuba’s recent economic history is that it peaked in the last quarter of 1984 and began a slow slide during the second half of the 80s. It then suffered a catastrophic plunge in the first four years of the 1990s. To the extent that we can estimate, a third of the economy disappeared during this time and a slow recovery followed. There was a spike in the 2000s when Venezuela began to provide petroleum at deeply discounted market prices, and that peaked just before the 2008-09 financial crisis.

After 2009, the Cuban economy really didn’t recover. For the most part it has remained at the alleged 2% growth rate, but given the unreliability of statistics from Cuba, it’s likely a lot closer to zero. That’s grim.

Cuba’s population, now shy of 11.2 million, is shrinking and rapidly aging. Cuba has been below the demographic replacement age since 1978. This is not a good scenario for productivity and economic growth. For that, you need people who are in the prime of the workforce. That’s not the Cuban demographic story.

Cuba is closing primary schools and opening homes for the elderly, closing pediatric wards and opening geriatric wards. That’s a burden for growth, but also creates business activity and opportunity: Cuba suddenly needs to build retirement communities. Cuba projects a population of 10.8 million in 2030. It is about to go from around two million people over the age of 60 to 3.25 million in 2030.

But it isn’t all bleak. Cuban life expectancy is approximately what you would expect in North America and Western Europe. That means levels of education are good. It means there is access to basic, quality healthcare. It doesn’t mean that you can have a banquet every day, but that basic nutritional needs are met. There are opportunities for sports. These are the kinds of things that contribute to well-being and that require lots of effective institutional arrangements.

When you put all these pieces together around education and health care, it’s clear that Cuba is likely a champion of investment in the development of human capital—but for the last 50 years it has an extremely low economic return on this investment. If you invest in human capital, whether in your company or in your country, sooner or later it will pay off if you have the right set of incentives. In other words, you need the right organizational design so that all these well -trained, well-educated people will be able to do their work. That’s what Cuba doesn’t have. But it does have a colossally well-trained work force. It is probably the best, most well-trained workforce at the cheapest labor-market price that any international investor could find anywhere in the world. You could find such first-rate people in Singapore, but they wouldn’t be cheap.

This is true despite the country’s very poor infrastructure. In Cuba, there are seven computers per 100 people — one of the lowest ratios in the Americas. Internet access in Cuba is very expensive. Consider that the median monthly salary in Cuba, when converted into dollars, is a bit below $20 a month. Then think about what you pay for a service like Netflix. For many Cubans even at a discount, half your monthly income would go to Netflix.

So how does Cuba make money? Its current principal source of revenue is the export of healthcare services by means of sending physicians, nurses, and healthcare technicians to countries like Venezuela and Brazil—an item that it has yet to record in its published official statistics. Cuba’s main resource to engage in the world is no longer sugar cane. It has tourism—beach and sun and one of the communist world’s last Jurassic political systems—but the real asset is the brains of its people. It could be an ideal location for healthcare organizations, but also for those in applied sciences, biotechnology, and pharmaceuticals.

We know two things about biotech in Cuba. One is that the quality of applied science seems to be first rate. And secondly, the business model for Cuban biotechnology has been laughably bad. They know how to make new products. They don’t know how to market them effectively. That’s a solvable problem, yet they haven’t been able to do it, and so a partnership with a European or a Canadian or a U.S. pharmaceutical company could be a great asset in the future.

Have the doors opened to U.S. company investment? Well, no. The power to authorize U.S. business investment in Cuba still rests with the U.S. Treasury Department Office of Foreign Assets control (OFAC)—and the fact is this agency’s documentation contains the exact same formulation that it had before December 17. Economic transactions, trade, and investment with Cuba remain prohibited unless they are specifically authorized by OFAC. The Government of Cuba must also authorize each and every foreign investment from any country, and it has yet to authorize one from the United States.

A lot of people get hung up on the issue of travel between the U.S. and Cuba. JetBlue recently launched direct commercial flights from New York. But there have been charter flights from Miami to Cuba since the late 1970s. OFAC has made particular determinations authorizing different airlines as charter flights for many years for various travel programs to Cuba, especially for cultural, educational, and religious groups.

There has been a U.S. embargo on economic transactions with Cuba since 1960. There are still restrictions on American tourist travel. Going to the beach is something that the neither the President of the United States nor OFAC can authorize. It requires an act of U.S. Congress. Congress decided in 2000 that it wanted to prohibit beach tourism and it didn’t want the president to have any discretion whatsoever on this point. Now, while more people will be allowed to visit, they still can’t go to the beach.

On the exports side, President George W. Bush authorized U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba in late 2001 under presidential discretion, which exceeded $5 billion between 2002 and 2014.

But, oddly, U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba declined by over one-third (if you compare January-June 2014 to the same months in 2015) since the President Obama’s announcement. The boom in U.S.-Cuba trade has yet to materialize.

Cuba does have a private sector, which it calls it the “non-state sector.” It includes mixed enterprises (foreign firms and state enterprises) and a “self-employment sector.” In a population just shy of 11.2 million, there are over 500,000 people who have self-employment licenses, according to President Raúl Castro’s report to Cuba’s National Assembly in July 2015. The rule of thumb among Cuban scholars who study this is for any one license there are on average four lawfully-hired employees. That would amount to over two million people in the self-employment sector. One reason why the average number of employees is four is because, once you reach five or more employees, your tax rate goes up. The Cuban government’s tax collection system is primitive. There is no personal income tax in Cuba. There is no corporate tax in Cuba. There is no value added tax in Cuba. There is no sales tax in Cuba. But there is a tax on the number of your employees. This tax system discourages economic and job growth.

The Cuban government has a list of occupations that are authorized by name; everything else is prohibited or reserved for state-run enterprises. Authorized occupations include plumbers or electricians. These are skilled workers, but the list rarely includes those who studied at the university. Thus in a country that has invested so much in the development of a human capital, it says in effect: if you attended university, then you’re going to work for the state.

Let’s say you go to the medical school at the University of Havana. Healthcare is a state sector, it’s not private activity. So what if you decide you want to make more money? You might realize that the one useful skill gained from your time at medical school is learning English. So, you quit as a physician and become a maid at a tourist hotel. You earn more money because your most marketable asset turns out to be that you can communicate in English.

This is a tragedy for the individual and for the society. It turns incentives about acquiring skills upside down. You do have people with university training in the private sector, but often not working in the profession for which they trained. There are some exceptions—for example you could be a tutor in the private sector, but you cannot be a classroom teacher. You can, in the private sector, teach foreign languages, but you cannot teach mathematics.

Thus the private sector is tiny. There is also foreign investment, although not a lot. The 2014 foreign investment law finally authorized wholly owned foreign enterprises, but thus far without exception they are all joint ventures with the government.

Cuba’s trade reveals its international partners. In 2013 in U.S. dollar-equivalents, Cuba exported $343 million to China and imported $1.5 billion from it. In contrast, it exported $81 million to, and imported $614 million, from Brazil. Cuba exported $2.3 billion to, and imported $4.8 billion from, Venezuela, its top partner. But China matters in one decisive way. The Chinese government strongly advocates that the Cuban government should reform its economy to achieve a faster, wider market opening. That’s not the way you might have guessed China would be advocating, hut in fact China’s role in Cuba is to try to persuade the Cuban government to emulate its own market opening.

The extraordinary competence of Cuba’s political leaders is sometimes easy to miss. They’re colossally impressive in the management of politics. They’ve remained in power. Who would have known that all communist regimes in Europe would collapse, but that only Cuba and four East Asian regimes would survive?

Cuba has a really, really well-educated and cheap workforce, as well as substantial evidence of entrepreneurial potential. If its political leaders can manage to lift constraints on investment, create the right incentives, and reform its tax code, the country could really boom. But that’s a lot of change to expect for the insular government of an island nation that’s otherwise stuck in time.

Reclassifying Office “Housework”

A few years ago, a colleague I’ll call “George” leaned in confidentially to tell me, “Take on a high-profile, low-stakes administrative task, then royally mess it up. They’ll never ask you to do anything like that again.” As a fellow law professor, George thought he was sharing his secret formula for writing scholarly books and articles – the coin of the realm in universities – while his colleagues did research on top of committee work like updating the curriculum and reviewing applications. Ever since I recounted this tidbit over a family dinner, his name has been shorthand for slackers at my house. If one of us tries to get out of walking the dog or washing the dishes, the one who picks up the leash or sponge is likely to tease the free-rider for “pulling a George.”

In most organizations female employees pick up after George. Instead of thanks, they get lower pay and less respect. Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg and Wharton professor Adam Grant want to change that. They wrote recently in the New York Times, “[s]omeone has to take notes, serve on committees and plan meetings — and just as happens with housework at home, that someone is usually a woman.” Not coincidentally, this work is dubbed “housekeeping,” sometimes even done by “office wives.”

Suggestions abound for how organizations can better spread the wealth of office housekeeping, both from Sandberg and Grant and from a 2014 primer by law professor Joan Williams and Rachel Dempsey, What Works for Women at Work. But businesses probably will continue to reward their Georges until they appreciate the harm it causes to the organization itself.

My book, Love’s Promises: How Formal & Informal Contracts Shape All Kinds of Families imports business ideas to families, and also provides a framework and terminology that can help businesses recognize the dangers of the George Syndrome. Families are shot through with exchanges, some legally binding contacts, and others so informal or unsuited to judicial enforcement that the law won’t enforce them. I call these not-legally-binding agreements “deals.” The most common agreement – which I call the “pair bond exchange” – is a legally binding contract under family law. Often one spouse keeps up the bank balance while the other focuses on keeping the home running smoothly. Family law recognizes the value of both contributions – cash and housekeeping – by treating them both as owners of any assets acquired during the marriage. It’s not so different from a small start up business in which one partner provides more capital and the other contributes more expertise and hours at the terminal to bring the product to market, yet they split profits evenly.

If a marriage ends through death or divorce, each spouse leaves with a share of the family’s assets even if one contributed more money and the other did more to keep the family healthy, happy, and well-mannered. But a property-hoarding prenup demotes that care work to a mere deal.

Consider the case of Michael and Hildegard Borelli, which shows how caretakers on the home front suffer when law takes that care work for granted. When 70-something San Francisco businessman Michael Borelli married 39 year-old Hildegard in 1980 they signed a premarital agreement that reserved most of his property — worth around $1.5 million — for his daughter from a prior marriage. Eight years later Michael suffered a stroke, and his doctors advised him to go into a nursing home. Michael promised to alter the prenup to give Hildegard some of his property — around $500,000, — if she’d disregard the doctors’ advice and provide the nursing care herself at their home.

Hildegard did her part, personally providing ‘round-the-clock nursing care for Michael until his death a year later. But Michael didn’t. She sued and lost because family law clung to the fiction that her caretaking was a pure gift. The California court cited pre-WWII caselaw for the proposition that “a wife is obligated by the marriage contract to provide nursing type care to an ill husband.”

Some businesses likewise take office housekeeping for granted. Law firms often designate associate’s work planning the firm retreat or training new hires as “non-billable,” and too many organizations overlook how a manager’s routine “good mornings” to everyone in the front office can help operations run smoothly all day.

Gary Becker’s Nobel-winning work on labor specialization in marriage shows the inefficiency in devaluing care work in relationships, but it’s UCLA psychologist Shelley Taylor’s book The Tending Instinct that illustrates how those insights translate to the workplace.

Taylor offers new language — “tending” – to describe the many relationship-enhancing activities that happen among friends, family, and colleagues. Reconceiving office housework as “tending” helps get its value translated from a mere deal – not remunerated – to the equivalent of a contract, a genuine and valuable part of a person’s job. It’s both gender neutral and new, unlike “housekeeping.” Talking about administrative work in new ways could prevent it from remaining largely invisible, noticed only when it’s botched.

Taylor shows that tending like that simple “good morning” from the boss reduces stress and its emotional, physical, and social toll. Mentoring, a common method of workplace tending, can improve skills, increase job opportunities and satisfaction, and increase longevity on the job. Bad tending, in turn, increases stress and its consequences. At the extreme, abused or neglected children become adults with more health and emotional problems, including depression, drug and alcohol abuse, heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. Conversely, people with close, supportive ties to family, friends, and colleagues are less likely to get sick — from cancer or colds — and when they do, the disease is often less severe. Having just one good friend at work translates to fewer sick days.

All that workplace tending done by both men and women helps employees work up to their potential, keeps health insurance premiums down, and prevents lost productivity that comes with extended sick leave. The Georges in every workplace may stop free-riding when tending gets recognized as valuable to the workplace – instead of a gift given to their employer with no expectation of return. Most importantly, the work itself will get properly valued, and along with that the employees who do it.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers