Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1258

August 25, 2015

Is Something Lost When We Use Mindfulness as a Productivity Tool?

I came to mindfulness as a healing practice after overcoming an addiction to Adderall during my junior year of college. I found myself in this situation because I thought that using Adderall to help me focus was no big deal — an attitude shared by 81% of students nationwide.

Adderall simply seemed like an innocuous shortcut to getting things done – and to do so efficiently yet effortlessly. I still remember the rush I felt my first night on Adderall: I completed every page of assigned Faulkner reading (not easy), started and finished a paper several weeks before the due date (because why not?), Swiffered my room (twice) and answered all of my unread emails (even the irrelevant ones). It’s also probably worth noting that I had forgotten to eat all night, and somehow found myself still awake at 4 a.m., my jaw clenched and my stomach rumbling. Sleep was nowhere in sight.

What I saw initially as shortcut to more focus and productivity ultimately turned out instead to be a long detour toward self-destruction. Rather than thinking of focus as the byproduct of my own power and capability, I looked outside of myself, thinking that a pill would solve my problems.

The long story short is that I eventually came to grips with my problem, got off the drug, and found an antidote to my crippling self-doubt: meditation – particularly, mindfulness meditation (or Vipassana meditation).

So to me, it’s somewhat ironic that mindfulness has now taken the media by storm because of its scientifically proven benefits for focus and productivity.

And it’s not just because I came to mindfulness as a way of healing from the fallout of the amount of pressure I put on myself to be productive. While mindfulness is not a little blue pill, it’s starting to be thought of as a kind of shortcut to focus and productivity, not unlike a morning coffee. A wisdom tradition associated with personal growth and insight is now being absorbed by our culture as a tool for career development and efficiency. But should mindfulness really have a particular goal, especially such a concrete one? Is it OK to think of a practice that’s all about “being” as just another tool for “doing”?

Companies seem to think so. Given the mindfulness buzz, it’s no surprise that corporate mindfulness programs are proliferating across the country. Google offers “Search Inside Yourself” classes that teach mindfulness meditation at work. Corporations like Goldman Sachs, HBO, Deutsche Bank, Target, and the Bank of America (among others) tout the productivity-related benefits of meditation to their employees – developments celebrated in the recent book Mindful Work by David Gelles.

The world of professional athletics too has drawn attention to the achievement-oriented underpinnings of the mainstream mindfulness movement – especially the NFL, most recently. In an attempt to understand the success of the Seattle Seahawks in the 2014 Super Bowl, The Wall Street Journal explained that the team’s “secret weapon” was their willingness to work with a sports psychologist who teaches mindfulness. Seahawks assistant head coach Tom Cable went so far as to describe the team to the WSJ as “incredibly mindful.”

This article was written in January 2015, a month before the Seahawks then lost the 2015 Super Bowl. I am not particularly cynical (and trust me, I really don’t care about sports), but something interesting happened in the wake of the Seahawks’ defeat: I heard multiple conversations among acquaintances and family members (all of whom are sports fans, and are non-meditating but aware of meditation) in which they expressed skepticism about the power of meditation for focus and success. I mean, how much can we embrace mindfulness as a tool for success if a team famous for meditating lost the Super Bowl?

Still a lot, I think. And I’m fine stopping here to admit (if you hadn’t already concluded yourself) that the commodification of mindfulness as a productivity tool leaves me with a strange taste in my mouth. Above all, I am resistant to the teleological attitude toward meditation – that it is a “tool” necessarily designed for a particular purpose, contingent on “results.”

And yet asserting this skepticism brings me back to a conversation I had with my vegan cousin a few years ago. He is a PhD student in biological anthropology, an animal activist, and has been a vegan for about 15 years. When I asked him if he was irked by all the celebrities going vegan to lose weight, he shook his head vigorously. “I’d rather have people do the right thing for the wrong reason than not do the right thing at all,” he explained (the “right” thing here being veganism).

This philosophy seems applicable to the mindfulness craze (aka “McMindfulness”) too. I am happy more people are getting the myriad benefits of meditation. I am glad that you’re no longer thought of as a patchouli-scented hippie if you’re an avid meditator. If corporate mindfulness programs mean that employee self-care is more valued in the workplace, then so be it.

But I also think there is room to consider an alternative way of talking about meditation, especially when it comes to how we relate to our work.

Looking at mindfulness as a tool for accomplishing what we need to get done keeps us trapped in a future-oriented mindset, rather than encouraging us to dilate the present moment. Of course, this doesn’t invalidate the neuroscience; mindfulness makes us get more stuff done. But what about allowing mindfulness to just be? To have the effects it is going to have, without attaching a marketing pitch to this ancient practice?

Psychologist Kristin Neff is renowned for coining the term “self-compassion.” In particular, Neff has asserted that the first component of self-compassion is kindness, the ability to shrug off those times when we “let ourselves down,” when we don’t get to check off everything from our to do lists. The other two components are awareness and, lastly, mindfulness. The goal is not to get more done, but to understand that we are enough, and that our worth is not contingent on what we get done. (Although funnily enough, studies have shown that self-forgiveness helps us procrastinate less.)

I’m not an idealist. I’m not saying everyone should start “Om-ing,” devoting themselves solely to self-compassion, and forgetting their to do lists. But I am saying that compassion, and self-compassion, ought to more in the foreground as we talk about mindfulness — even in corporate mindfulness programs.

There is no shame in wanting to be productive at work. But there is also no shame in being able to cut yourself some slack, to extend yourself some love during those times at work when things don’t feel so great.

What Really Motivates Workers in Their 20s

As we all know, young workers are a contemptible bunch. They’re “lazy,” and lack the admirable work ethic of their elders. They have an overblown sense of entitlement, believing they have some kind of right to walk right into a plum job in their early twenties rather than working their way up. They might even be a generation of narcissists, a consequence of their over-indulgent helicopter parents and a culture that favors giving every kid on the soccer team a trophy just for showing up.

Actually, like many things “we all know,” these nasty stereotypes disintegrate quickly when exposed to the harsh light of research evidence. For the past 20 years I have been studying 18- to 29-year-olds, a stage of life I call “emerging adulthood.” I coined this term to help people recognize that young people grow up later than they did in the past, in terms of entering adult commitments such as stable work, marriage, and parenthood. The rise of emerging adulthood does not mean that young people today are defective, only that it takes longer to prepare for the workplace than it did before and that they (wisely) want to enjoy a brief period of freedom before settling into adult responsibilities. My research, involving many hundreds of in-depth interviews and several national surveys involving thousands of young people, has shown that the negative stereotypes are mostly false and today’s emerging adults are a remarkably idealistic and hard-striving generation.

Our recent 2015 Clark University Poll of Emerging Adults, asked a national sample of 1,000 21- to 29-year-olds a wide range of questions related to education and the entry to work. We focused on ages 21 to 29 because the goal was to examine the transition to work during the twenties. The results were illuminating, and provide important information for anyone who works with or employs emerging adults. Here are some of the highlights:

Not lazy, but often not fully committed to the job. Most see themselves as diligent workers; 89% agreed that “No matter what job I am doing, I try to do it as well as possible.” However, 40% also admitted that “On a normal work day, I try to get by with doing as little work as possible.” This blasé attitude may be due to the fact that many of them are currently in transition jobs, while they finish school or try to decide what field they really want to pursue; 46% agreed that “My job with my current employer is temporary.”

Willing to work their way up, but not to be exploited. They recognize that it takes time to gain expertise in a job, which often means doing the lower-level work for a while; 78% agreed that “If I were in a boring job, I would be patient and try to move up within the company.” On the other hand, they believe that good faith should go both ways; 54% agreed that “If employers do not pay me well, they do not deserve my best work effort.”

Many are distracted by social media while on the job. Today’s emerging adults have been called a generation of “digital natives” who grew up with social media as second nature, in contrast to their mostly “digital immigrant” employers, who came to social media later and often grudgingly. This generation gap is evident in the 2015 Clark Poll results, in which 54% agreed that “I do not see anything wrong with checking my Facebook page, tweeting, or texting with friends now and then in the course of a normal work day.” One suspects their employers would beg to differ.

In addition to these recent findings, previous research has shown emerging adults to be not the narcissists of legend but strikingly idealistic and generous-hearted about work. In the 2012 Clark University Poll of Emerging Adults, which was also a national survey, 79% of 18- to 29-year-olds agreed that “It is more important to enjoy my job than to make a lot of money,” and 86% agreed that “It is important to me to have a career that does some good in the world.” These expectations may be unrealistically high; in the 2015 poll, 76% stated that “I am still looking for my ideal job.” Also, 71% admitted that “I have not made as much progress in my career as I would have hoped by now.” They remain restless and searching as emerging adults; 66% agreed that “My current job is not in the field I hope to be in 10 years from now.”

So what is the bottom line here for their older colleagues who are puzzled by these young workers? I’d recommend giving them a chance to show who they are and what they can do, as individuals. That is, don’t assume they are going to fulfill your worst expectations for their generation. They may not be as diligent as you would like them to be, or as focused on work that is more important to you than it is to them at this transitional time of their lives. They may be more distractible by social media than you would wish, and less committed to staying with your company for the long run. But they are eager to find engaging work that they can enjoy, and to do something important that can make some kind of positive contribution to the world around them. If you can find ways to direct their energy and idealism in productive ways, they may surprise you.

5 Work Stresses You Can Alleviate with Tech

From the pressure to keep up with social media to the low-level irritation produced by a world in which something is always beeping or buzzing, technology can produce its own set of anxieties.

At the very least, you need to organize your devices, accounts and online time so that you reduce your tech-induced stress. That means letting go of the idea that you need to keep up with social media, reply to every email and accumulate the maximum number of LinkedIn connections.

But keeping your online life from driving you crazy isn’t enough; you can also harness your devices and platforms so that they reduce stress and support good mental health. Here’s how technology can help you tackle five of the most common sources of work-related stress:

Distraction: Whether it’s a constant stream of colleagues knocking on your door with a quick question, or your own tendency to fall into a Buzzfeed quiz hole when you should be working on a Powerpoint deck, distraction is a major contributor to workplace stress. Rein in online distractions with tools like RescueTime (which tracks how you spend your time online), Focus (which blocks distracting websites) or Freedom (which can keep you offline altogether). To get dedicated chunks of work time without real-world interruptions, your best bet is to block off chunks of time in your calendar—then close your door (or get out of the office) and turn off your inter-office chat and email clients.

You and Your Team

Stress

Don’t let it get the better of you.

The demanding boss: If your boss typically contributes to your work stress, rather than alleviating it, it’s time to tame your boss with technology. Have you got a manager who emails you after hours, and expects a response before the next business day? Set up an email filter that sends you a text message when she emails you (so you can stop constantly checking your inbox). If you want to strike a balance between reinforcing her behavior with immediate responses and jeopardizing your job by ignoring after-hours messaging, use a tool like Outlook’s delay delivery or the Boomerang Gmail extension to time your response for a few hours after your boss has emailed. Have you got a manager who only points out your shortcomings, instead of your accomplishments? Use a note-taking program like Evernote to build a file of project notes and positive email feedback that you can show your boss at your next performance review.

The draining commute: Long commutes are one of the top reasons people feel dissatisfied with their work. But your commute can be a productive, energizing or restorative part of your day if you’ve got the right toolkit. For a productive commute by transit, install a newsreader like Feedly or Flipboard and use it to follow news in your field and related industries; hook your newsreader up to Buffer or Hootsuite and queue up a day or week’s worth of tweets and LinkedIn updates while you’re on your way to or from work. For an energizing commute by foot or bike, combine your commute with a workout by using Spotify’s Running feature to get a playlist calibrated to your pace, or the Gymboss app to power you up with interval training (you’ll want a shower at the other end of your commute). For a restorative commute, resist the urge to subscribe to podcasts that make you a better salesperson or in-the-know HR pro, and instead subscribe to podcasts that speak to personal interests like parenting, comedy, or creativity.

Fear of missing out: Professionals have long struggled with anxiety about what they’re missing—the conferences they aren’t attending, the meetings they aren’t invited to, or the industry news they’re the last to hear. But social media makes that fear of missing out (aka FOMO) a lot tougher, because we’re constantly subjected to the tweets, Facebook posts, and LinkedIn updates about all the stuff we’re not doing. If you want to improve your character and mental resilience, you can take each of these moments as an opportunity to build your character and transcend your own petty jealousies—or you can do what I do, and filter out the content that triggers your FOMO. If I’m not attending the SXSW Interactive Festival, for example, I use Tweetdeck to filter out any tweets about SXSW; and if I have a particular colleague whose Facebook updates often trigger my anxieties, I hide him permanently from my Facebook feed.

Sleeplessness: When you’re facing a major deadline or a difficult issue at work, bedtime can be a nightmare: instead of falling asleep, your brain fixates on work and ramps up your anxiety levels. My favorite way to combat that bedtime anxiety attack is with my iPhone. Listening to an audiobook from Audible—typically something light and funny—can usually keep my mind off my work long enough to let me fall asleep; Audible even offers a sleep timer that automatically shuts off your phone after 15 or 30 minutes. If I’m too stressed out for a mere audiobook, I use a guided meditation recording or a meditation app like Stop, Breathe & Think.

Your anti-stress tech toolkit needn’t be confined to these five stressors. Once you start thinking of technology as an ally in combatting stress, rather than yet another source of work stress, you can work to identify the tools and workflows that can help you tackle each of your major sources of work-related stress.

Women in Asia Are More Financially Savvy than Women in the U.S.

Around the world, the face of wealth isn’t what it was a generation ago. Today, it’s increasingly young, worldly, self-created — and female.

Our new book, Harness the Power of the Purse: Winning Women Investors, based on recent research from the Center for Talent Innovation, indicates that there is a rising tide of female wealth worldwide. Yet within that tide, we also found that there are different and distinct streams. While it’s easy to think of the female market as homogenous, our research shows that cultural, geographical, and generational differences, as well as disparate sources of wealth, all affect how women view and allocate their wealth.

When examining women and their relationship to wealth, what’s happening right now in Asia offers a window into where the West should be headed in the future. We surveyed women in the United States, United Kingdom, China, Hong Kong, Singapore, and India with personal income of at least $100,000 or investable assets of $500,000 or more. Our findings indicate that women investors in Asia are in many ways ahead of their counterparts in the U.S. We see this especially in women’s levels of confidence and engagement, their degree of risk tolerance, and the level of diversity in the financial services industry across the region.

Much of this trend is due to Asia’s economic boom over the past decade, which has accelerated the exponential growth of the female market, resulting in a cadre of business- and tech-savvy women who are accustomed to making financial decisions that affect billions in corporate assets, as well as controlling and deploying significant personal assets. These include such superstars on Fortune’s 2014 list of the 50 Most Powerful Women in global business as Chandra Kochbar of India’s ICICI Bank, Chua Sock Koong of Singapore Telecommunications, and Zhang Xin of SOHO China. Though the burgeoning opportunities for the industry are still dominated by men, more women are starting businesses. China, especially, stands out: No country has more self-made female billionaires. Zhou Qunfei, the world’s richest self-made woman and founder of Lens Technology, is emblematic of a new class of female entrepreneurs in China who have built their wealth from scratch. Asian women are also inheriting first-generation wealth and family businesses, something that was rare a generation ago.

In India, 59% of women in our sample report they’re generating their wealth; only 20% derive it from their spouse and 21% inherit it. In China, 68% have self-generated wealth, while only 16% derive it from their spouse and 16% inherit it. And their wealth is not just substantial. It is growing: 58% of women surveyed across the four Asian countries expect their assets to increase.

As more women generate their own wealth, women are increasingly controlling the deployment of their assets. The vast majority of women we surveyed across the four economies in Asia are financial decision-makers in their households: 87% in China, 80% in India, 71% in Hong Kong, and 59% in Singapore. Compare these numbers to those in the U.S., where 44% of women describe themselves as decision-makers.

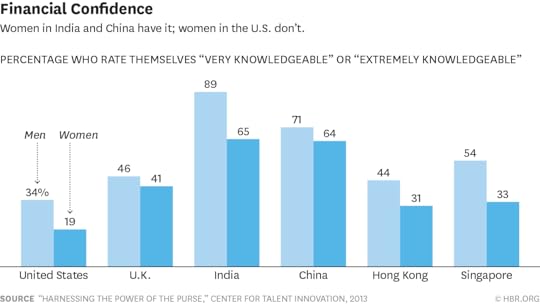

We also found a divergence in financial confidence between the East and the West. Across the countries we surveyed, women were as financially literate as men. In the U.S., for example, 35% of women and 39% of men passed our literacy assessment. But their confidence isn’t always commensurate with their acumen — particularly among Western women. Men in the U.S. are 79% more likely than women to express confidence in their financial know-how. In contrast, Chinese women are virtually as confident in their acumen as Chinese men (64% versus 71%).

Our research, in fact, finds that women in Asia are remarkably confident about their financial savvy, with women wealth-creators — as compared to spouse creators and inheritors — the most confident. Subha Barry, an adjunct professor at Columbia University and former Merrill Lynch managing director, attributes this to deeply engrained cultural mores across the region. “Even in rural India, women manage the households and pay the bills,” she says. “Women’s confidence comes from having handled money from an early age.”

While women in the U.S. often struggle with a cultural overhang of the Mad Men era that dictates men take charge of major financial decisions, Asian women within the countries we studied do not seem as constrained by traditional gender roles. As Dominique Boer, head of relationship management for Asia and Greater China at Standard Chartered, points out, “It’s not uncommon to see women, particularly in Shanghai, control all financial decisions, as women there have a long history as ‘money makers’ controlling gold and spice trades.” One of the biggest cultural differences between the West and Asia is the respect attendant on women. “Women are absolutely seen as equal partners,” affirms a senior wealth advisor in Asia.

There are also major differences in women’s appetites for risk. It’s widely assumed women are more risk-averse than men, yet, in Hong Kong and Singapore, women are as likely as men to be comfortable with a more aggressive portfolio allocation. In the U.S., a gender gap exists with 36% of women choosing a more risk-averse portfolio compared to 28% of men. The gender gap disappears though when you look at the sub-segments of the market in the U.S. Thirty-two percent of female wealth creators are risk-averse in the U.S., while 26% of women who inherited their wealth are risk-averse, compared to 28% of men overall.

This strengthening undertone of equality coupled with Asian women’s confidence and comfort with risk seem to also be influencing diversity dynamics in financial services across the region. For example, wealth management teams in Asia tend to feature higher proportions of female advisors than their counterparts in the U.S. and U.K. Based on interviews and focus groups we conducted across the region, cultural dynamics are playing a key role. In China, for example, the gender-equality legacy of Communism opened opportunities for more women like Qunfei to succeed. The rise of more successful women in leadership coupled with cultural influences have also helped shift the wealth management industry’s readiness to better serve a more diverse client base. In China, women outnumber men on advisory teams by three to two. In Southeast Asia, about three-quarters of wealth advisors in Singapore are women, our interviewees tell us — a function of Singapore’s two-child policy, which ensures women enjoy the same opportunities as men. The percentage of women in similar roles in the U.S. lag dramatically with women accounting for a third of financial advisors and only 23% of Certified Financial Planners.

Over and over, our focus groups in Asia proclaimed the message: “Women are leading and sustaining the economic boom and driving growth opportunities for the wealth management industry.” Asian women investors are shaping the future of the industry, and the West (as well as the world) should take note.

Law Firms’ Grueling Hours Are Turning Defectors into Competitors

In this latest flurry of debate about working long hours, some have intimated that overwork is inevitable in highly competitive industries such as law, finance, and high tech.

But that’s just not true.

We’ve all heard by now that productivity decreases with overwork, while attrition and health care costs increase. What you may not have heard is that businesses who drive people relentlessly create competitors who poach top talent by offering a more humane way to work.

A new study from the Center for WorkLife Law reports on this phenomenon in the legal profession. The report identifies over 50 entrepreneurial businesses that offer lawyers jobs with better work-life balance than large law firms offer. Big Law, meet New Law.

New Law is filled with Big Law refugees, who’re siphoning off the work Big Law used to rely on to balance its books.

This isn’t small potatoes. One New Law company, Axiom, is now one of the largest providers of legal services in the country, and boasts over half the Fortune 100 as clients. Axiom is an order of magnitude larger than most new models of legal practice, but it is not the only one nipping at Big Law’s heels. Counsel on Call was worth nearly $50 million as of 2013, with over 900 lawyers; it serves one-third of the Fortune 100. While Big Law still controls legal matters that require very large teams, or teams that span many different practice areas, virtual law firms (such as Rimon, VLP Partners LLP, and Potomac Law Group) and virtual law companies (such as Berger Legal LLC and Cognition LLP) compete successfully for a wide range of matters that may require high-level expertise but involve only one or a few seasoned lawyers.

Big Law’s commanding market lead in specific practices areas is also being challenged by boutique firms. A notable example is Bartlit Beck Palenchar & Scott, which handles high-profile trial work; it led the British Petroleum National Oil Spill Commission for the Obama administration. Other examples include Landmark Law Group (real estate), Smithline PC (tech transactions and IP licensing), Miller Law Group (defense-side employment law), Valorem Law Group (complex litigation), and The California Appellate Group (appellate).

Relatively routine legal work of the sort that used to keep first- and second-year associates busy at large law firms is also migrating away. The behemoth of “legal process outsourcing” is Axiom, which has commodified large companies’ contracting and certain litigation functions. Counsel on Call does e-discovery, contract review and abstraction, and other managed services, Raymond Law Group specializes in “price-sensitive commodity (litigation) work”). For a fixed fee, The General Counsel, Ltd will handle all of a company’s employment law matters.

Secondment Firms handle overflow from in-house legal departments and part time in-house counsel work for companies too small to need a full time General Counsel. The first step was that a lot of legal work formerly done by outside counsel migrated to in-house corporate legal departments. Now even the overflow work from in-house departments has migrated away from Big Law, too.

Last but not least, some New Law firms target the small or mid-market companies that may have been priced out by the steep rise in Big Law rates. Examples are The Mitzel Group LLP, Phillips & Reiter, PLLC, InnovaCounsel, LLP, Avökka, The General Counsel, Limited, Exemplar Companies, Inc., Burton Law LLC.) (Some of these target large companies as well.)

All this adds up to a sobering picture that helps explain why Big Law’s book of business is no longer growing by leaps and bounds. “While the … revenue that is actually being siphoned off by these non-traditional service providers still seems modest compared to the overall size of the legal market,” noted influential legal commentator James Jones, “they’re growing and they’re growing every single year.” Big Law used to do the entire spectrum of legal work, from low- to high-complexity. Now “the unbundling taking place in the corporate legal market” means that the “’fat middle’ of ‘meat and potatoes’ legal work” is being siphoned off, much of it to New Law. It’s classic disruption.

So here’s the real story. Big Law attorneys are notably unhappier than most other lawyers, for a variety of reasons. Far and away the most common one given by the Big Law refugees who have founded New Law companies is the desire for work-life balance. Recent research suggests that what Big Law offers—one-off individual accommodation policies—are not effective. Typically, the people who use them suffer the worst of both worlds – they’re stigmatized, but find themselves working full time for part-time pay. What New Law offers is what leading researchers now agree is a more promising formula: they hard-bake work-life balance into the business model.

New Law firms offer attorneys two very different types of alternative schedules. The first is genuine part-time work that can be done from home. This is popular both with lawyers who self-identify as stay-at-home parents and with those who have second careers (Counsel on Call is headquartered in Nashville and provides day jobs for musician-lawyers there). The second is full-time flex: 40 to 50 hours a week (but no more), worked from home, with completely flexible hours and the ability to be show up for dinner and vacations with your family. A lot of men want full time flex, alongside many women. “Many of our lawyers, myself included, had a difficult time while in full-time private practice fully committing to events, vacations, and time with their families and friends. That’s one reason many lawyers, including many men, are leaving Big Law,” said Eric Schultenover of Counsel on Call. Another Big Law refugee, Charulata Pagar of VLP Partners LLP, whose earnings increased when she left her firm (taking clients with her), said she also loved the fact that she was “at home with my seven year old who didn’t get into camp this week.” What’s not to like?

Law firms that drive their people relentlessly will lose a portion of those people – they already know that. The bigger threat is that astute, highly competitive entrepreneurs will organize those defectors and steal the relatively routine types of business that have always kept Big Law’s lights on. Or that entrepreneurs will found virtual and secondment firms that steal away high-value work, and offer all lawyers the flexibility and freedom Big Law won’t.

Whether it’s Amazon or a Big Law firm, large companies that offer only one gear – overdrive — should take notice. There’s strong demand in the market for work-life sanity, and creative entrepreneurs are inventing new business models to meet it. They’ll steal your people – and your business.

August 24, 2015

Data-Driven Management Can Also Be Compassionate

HBR STAFF

Should he desire, Jeff Bezos has a simple, powerful and culturally-compatible way to combat accusations that Amazon is a soulless, dystopian workplace: double down on being data-driven. Preempt bad employee vignettes with better empathic analytics.

Amazon should explicitly measure for the care, compassion, and kindness that Bezos justly celebrated in his 2010 Princeton commencement address. Monitor workplace “affect” as thoughtfully and rigorously as business “effect.” No, Bezos shouldn’t embed a C@D—Crying@Desk—metric on his KPI dashboard. But Amazon’s CEO might understandably want greater (statistical) confidence that his high-performance culture quantitatively reflects and respects the quality of mercy.

If Amazon’s culture of metrics truly cares about caring, in other words, it will measure it. Data will eradicate ignorance and ambiguity. Bezos’ best brains—and hearts—need to analytically define what they want empathy and compassion to look and feel like at their company. That may sound bloodless. But when your founder has declared data the lifeblood of his firm, it’s truly not.

There’s nothing glib or “tongue-in-cheeky” in this. To the contrary, data-driven compassion is completely consistent with the culture of metrics Bezos has sought to create since he launched Amazon.

As the New York Times article observed, “Amazon uses a self-reinforcing set of management, data and psychological tools to spur its tens of thousands of white-collar employees to do more and more. ‘The company is running a continual performance improvement algorithm on its staff,’ said Amy Michaels, a former Kindle marketer.”

Why shouldn’t or wouldn’t core values such as empathy and compassion be actively monitored, measured, and analyzed? Explicitly excluding kindness from managerial dashboards may send the wrong kind of message about the right kind of behaviors. “Continual performance improvement algorithms” that minimize or ignore behaviors the founder publicly cherishes are recipes for pathology and dysfunction.

If Bezos—who literally enjoys access to every bit of data that matters at Amazon—truly suspects or fears his metrics-obsessions have subverted the human values he highlighted at Princeton, you can bet that empathy and compassion metrics will soon be baked into Amazon’s next set of people analytics. A Culture of Metrics 2.0 becomes essential.

The most important insight here affirms that the roads to organizational hell are paved—not just digitally driven—with good intentions. That’s ultimately self-destructive. Innovators defined and led by data-driven decision-makers inspire schizoid enterprise cultures that bring out the best in people who want to build on data, and the worst in those looking simply to follow it—“I was just following the data/orders/metrics/KPIs,” etc.

Why? Because—more often than not—data inspire affective, not just effective, response. The key cultural quote from the Times story makes the point. “Data creates a lot of clarity around decision-making,” said Sean Boyle, who runs the finance division of Amazon Web Services and was permitted by the company to speak. “Data is incredibly liberating.”

That raises an obvious question: Liberating for whom?

When cultures authentically commit to being data-driven, data can literally dictate what you and your colleagues should do next. For many people, that’s not liberation; it’s servitude. Data end up removing choices instead of creating them. The “clarity” data supposedly bring eliminate excuses and rationalizations for avoidance and delay.

As the Times fairly noted, “Explanations like ‘we’re not totally sure’ or ‘I’ll get back to you’ are not acceptable, many employees said. Some managers sometimes dismissed such responses as ‘stupid’ or told workers to ‘just stop it.’”

When a founder/CEO cherishes data, analytics, and metrics as corporate cultural totems, then that becomes part of the enterprise DNA. You don’t address it by memos and charismatically appealing to people’s good intentions and better selves, you deal with it by—yes!—asking for and insisting upon better data and metrics.

At Amazon’s cultural core, however, data and meaningful analytics are fuel and enzyme for innovation and inspiration. Outliers aren’t artifacts or aberrations; they’re gateways to new markets, novel technologies, or transformative insights that will knock Bezos’s socks off. Yes, you must respect and hit your “core metrics” but data truly liberates the enterprising intrapreneur. You betray Amazon’s principles and your commitment to the company if you don’t embrace data as your path and partner to the truth.

That’s not a challenge to the mediocre to up their game; it’s a declaration that great talent and great effort and great vision with great data isn’t good enough for Amazon. If you’ve got a problem with that, Bezos has a problem with you.

But if great data and great analytics make it too easy for Amazon leaders and managers to swap apathy for empathy, then maybe they’re not so great. That’s exactly the kind of challenge a Jeff Bezos cares about.

What Facebook’s Anti-Bias Training Program Gets Right

No matter how highly you think of your organization, chances are its members—including you—are biased in ways that harm both you and others. Decades of research tell us that systematic errors affect our judgments and decisions at work, as well as the way we interact with others. And some of these biases are unconscious, including racial, gender, and income discrimination. The consequences of such insidious biases can be quite costly to an organization, from leading it to hire or promote the wrong candidates to investing in less innovative ideas just because of who proposed them to crossing ethical boundaries.

For instance, Lamar Pierce (of the Olin Business School in St. Louis) and I found evidence of illicit behavior as a result of income discrimination, when we analyzed data on hundreds of thousands of records on inspectors conducting vehicle emission tests. Inspectors felt envy toward customers driving luxury cars and empathy with those driving standard cars since, like them, they did not seem to have high salaries given the type of car they drove. As a result, inspectors were more likely to fraudulently assist the customers driving cheaper cars, passing them even if they didn’t abide by emissions guidelines.

Increasingly aware of the costly consequences of bias, leaders at various companies are taking action. Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg recently wrote about her company’s introduction of a course for its employees aimed at combatting unconscious biases. A new website shares Facebook’s presentations on bias with the public.

Such training programs are a positive step, but, in order for them to be effective, they need to be thoughtfully developed—something that Facebook seems to have done. In fact, just raising awareness of unconscious biases is not sufficient to end them in organizations (as I discussed in this post). To effectively combat them, training programs also need to help people accept that biases affect them, stress their concern about the consequences, and assure people are willing to learn to replace those tendencies with ones that more closely match their values (e.g., not having prejudice).

Raise awareness and acceptance of the influence of bias. Training programs are generally a good tool for raising awareness about the existence of biases and their implications, especially when they give participants the opportunity to test the extent to which they are biased. (If you are curious about your implicit biases in a wide variety of domains, from race and gender to religion and age, you can take an online test here).

Having taught courses on biases and decision making to executives and MBA students for quite some time, I know that it is not always easy for people to accept that systematic errors affect their decisions. Most of my students easily recognize that their colleagues and friends are biased but generally don’t think they are themselves. Stressing that even smart, well-intentioned people are influenced by biases because of the way our minds are wired usually helps my students feel more accepting of the fact that they may have discriminated against others based on gender, race or other factors in the past.

Stress concern about the consequences of bias. We all care about the outcomes of our actions. And research suggests that when we realize that our behavior affected others negatively, we get more concerned about actually fixing our actions so that they do not generate the same costs to others in the future. For instance, Lisa Shu (of London Business School), Max Bazerman (of Harvard Business School), and I found that identifying the victims of our behaviors makes people feel less virtuous about it as compared to leaving the victims unknown.

Discuss strategies that eliminate unconscious bias and how to apply them. Despite decades of research on the pervasiveness and workings of biases, only a few studies to date have examined how to effectively reduce them. This research has identified a few successful interventions that can be discussed in training programs. In one experiment, Nilanjana Dasgupta (of the University of Massachusetts Amherst) and Anthony Greenwald (of the University of Washington) found that it is possible to at least temporarily reduce people’s prejudices by showing them pictures of iconic examples of individuals who do not fit common stereotypes—such as African-American icons like Martin Luther King, Jr., in conjunction with infamous white villains like serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer.

Another approach that proved effective in reducing unconscious racial bias was tested in research studies where people listened to stories, told in the second person (the “you” voice), in which a white assailant was attempting to hurt them and a black man came to their rescue. A longer and more vivid version of the story that increased its emotional pull was doubly effective at reducing bias. Yet another approach that worked well involved telling participants to imagine a scenario in which they were playing a game of dodge ball in which everyone on their team was black and everyone on the opposing team was white.

These might sound like short-term mind games, but some evidence suggests the effects of these interventions could be long lasting. In one experiment, carried out over 12 weeks, non-African-American students in a psychology course were first alerted to their prejudice (90% of them showed anti-black bias) and taught a range of de-biasing strategies they could employ on their own time. This was done through an education and training program that involved two components—which reflect the steps we are discussing.

First, it educated participants about implicit biases in order to evoke a general concern about them and provided information about the implications of implicit bias for discriminatory behaviors across a wide range of settings (e.g., interpersonal, employment, health). Second, it presented five different strategies to eliminate such biases and described how to apply them in daily life.

For instance, one strategy was perspective taking: adopting the perspective of a member of a stigmatized group. A second was contact: increasing exposure to members different on dimensions such as race and gender. Yet another was individuating: viewing others according to their personal characteristics rather than stereotypical ones.

As part of the intervention, participants in the study were prompted to report and reflect on their use of these strategies. The results: With the participants’ sustained effort, prejudicial attitudes decreased and stayed down for at least two months. Thus, unconscious biases, like a bad habit, can be unlearned, but it takes some conscious effort.

Similar to the intervention used in this study, training programs should involve discussions of a variety of strategies that can effectively reduce bias and of ways in which people can apply them. For instance, employees may be encouraged to get into the habit of pausing to ask themselves if they would react differently to a person if she or he was of the opposite gender or belonged to a different race.

By taking all these steps deliberately, anti-bias programs can succeed in reducing or even eliminating biases in the workplace.

CEOs Can’t Give Feedback Only to Their Direct Reports

Steven Moore for HBR

I began my tenure as CEO of Campbell Soup Company in 2001 with the mandate to turn around an iconic but struggling consumer products company. Soon after, I asked Gallup to conduct an engagement survey of our leadership to assess the level of personal commitment employees felt toward the organization and its goals. It’s an important thing to measure because companies with higher rates of engagement have been shown to meaningfully outperform those with low engagement. The results of Gallup’s initial survey of Campbell were very poor, among the worst they’d ever seen in the Fortune 500.

At the time, our Global Leadership Team (the top 350 leaders) had an engagement ratio of 1.67:1, meaning that for every 1.67 people who were engaged in their work, 1 person was not. This amounted to 220 leaders doing the work of 350 leaders in the face of one of the company’s toughest moments in its 125 year history. Over the next decade, I made it my mission to champion superior engagement at Campbell—and when Gallup did the same engagement survey of our Global Leadership Team 10 years later, in 2010, the engagement ratio had skyrocketed to 77:1, among the best Gallup had ever seen in the Fortune 500.

How did we do it? There were countless contributing factors to our successful engagement story at Campbell. But one unique practice that made an important impact, and that I believe can make a significant impact in other organizations, was our commitment to management development conversations that we called One-Over-Ones.

A One-Over-One was a discussion that would take place between me (the CEO), Nancy Reardon (my CHRO), my direct report (a senior manager), and that manager’s direct report (a subordinate). These meetings took place after the senior manager had already completed the traditional performance review of their subordinate. Nancy and I would review the evaluation and then prepare to have an intimate discussion between the four of us.

Further Reading

Giving Effective Feedback (20-Minute Manager Series)

Communication Book

12.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

These were notably different than regular “performance reviews” because they were top-line conversations focused on the development of the leaders; they were not tedious rundowns of specific tasks or objectives. The focus was leadership itself. The benefits were tremendous in stimulating the engagement of our senior leaders.

There are three important reasons I believe discussions like this should take place in other organizations:

They show that you value people. It is imperative, particularly at the CEO level, to make time for what you say is important. When you proclaim that people are essential to the success of the organization—you have to support that statement with action. I would do an average of fifty One-Over-Ones a year, at about an hour each, and they were the most important 50 hours of my work year. Making the necessary time to have these discussions shows that you are devoted to people’s advancement and helps you stay connected to them in a more personal way throughout the year.

You further demonstrate that you value people by setting the appropriate tone for the meeting. These were not monologues where we would regurgitate the subordinate’s evaluation while they sat rapt and silent. One-Over-Ones at Campbell were informal, candid, two-way conversations that afforded both the manager and their direct report the opportunity to approach the CEO and CHRO honestly with whatever leadership quandaries, ideas, or questions they had. The conversations were an opportunity to learn more about how they were leading. What was working? What wasn’t? How could we help ensure they were poised for success in the coming year?

That information set the stage for meaningful follow-up and also created a forum for leaders to voice their career desires in a context where they knew they would be heard; they could nominate themselves for newly available leadership roles or ask for our support in exposure to new work experiences—like an international assignment or working on an acquisition team. This was valuable both for succession planning and for earning their trust by visibly championing their career goals. Overwhelmingly, both the manager and subordinate would leave these discussions feeling deeply supported and excited about their development agenda.

Everybody needs to grow. When having these conversations at the CEO level, even the subordinate of the manager is often the head of a huge business unit and is responsible for leading large teams of people. A problem we’d observed in the Fortune 500 community was that by the time a leader ascended to a very senior level, they no longer had meaningful evaluation and development discussions. The prevailing attitude was that they had reached a point where they were beyond that type of conversation. But that is simply not true.

No matter the level, all leaders need to further hone their skills, to stretch, to grow, to learn. You can’t rely on past successes to propel you forward in a fiercely complex world. What’s more, many senior leaders want to continue their development but they don’t know how to make the time amidst their extraordinarily demanding schedules—and their desire isn’t supported by the organization in any visible way, so it falls by the wayside. One-Over-Ones afforded high level leaders at Campbell the rare opportunity to reflect on their leadership and engage in productive development conversations that helped them do their jobs better.

They model desired behavior. As a leader, you must model the behavior that you want to see manifested in the larger organization. Often, the development plan in a traditional performance review is hastily scribbled at the end of the report, signed off on relatively thoughtlessly, and never followed up on throughout the year. This sends the message that it’s not important; it’s hard to engage with an afterthought. But it is essential that leaders be reminded that they are expected to reflect on their leadership skills—and to make the time to improve their leadership craft.

That’s why at Campbell the core focus of a One-Over-One was to actively develop leaders—to formulate a specific plan for doing so, and to provide any resources necessary to bring that agenda to fruition. This signaled to my direct reports, and the entire leadership team, that learning and development were very important to me—as was the notion of being closely involved with developing one’s subordinates. It also worked as a teaching mechanism. Our direct reports would watch how Nancy Reardon and I would talk through the review. They would see that we tried to deftly bridge the gap between being tough on the standards of performance and tender with the people involved. Through observing and participating, they learned how to lead their own One-Over-Ones. As people became more and more conscious of the benefits, the practice trickled down throughout the organization. We witnessed that modeling the importance of growth and leadership development at a high level translated to engagement with learning at every level.

I strongly recommend this practice to any leader who is looking for ways to better develop and engage their leadership team. It was certainly an important part of our turnaround at Campbell. These meetings, in tandem with a host of other strategic initiatives, resulted in superior employee engagement and cumulative shareholder returns in the top tier of the global food industry. One-Over-Ones provided an opportunity to lead by example, to give senior leaders development opportunities they might not get elsewhere, and to reinforce how important our people were to the success of the organization.

A traditional performance review can only go so far. To truly lift performance, all leaders must become more intimately involved in developing and engaging their leaders through candid development conversations.

Greece and Its Misguided Champions

With the Tsipras government having resigned and Greece (probably) heading to the polls to vote on September 20, it may be time to consider how we got here. While much can be said about internal dynamics within Greece, we shouldn’t underestimate the impact of some global thought leaders who have shaped opinion not only internationally but also in Greece, making its crisis a cause célèbre for progressive economists. Pundits such as Paul Krugman, Joe Stiglitz, and Jeffrey Sachs have rushed to comment on the Greek crisis, eagerly using their considerable influence, followed by like-minded commentators. Yet, how much of this analysis is grounded in the causes as opposed to the symptoms of the Greek crisis?

Greece offered a tantalizing opportunity to socially minded critics to condemn the approach taken by the euro group under Germany’s leadership. Greece was seen as an exemplar of a country under assault, victim of the waning European sense of cohesion and social justice, and of ineffectual, neoliberal policies. The controversial style and substance of Yanis Varoufakis and the Tsipras government had come to be seen as a rare sign of defiance and of standing up to injustice.

Framing this as a case of a small country defying the bullies misses the point. It is too easy to view the Greek mess as a case of austerity policies gone berserk.

There is some truth to the criticism. German policy makers have shown dogmatism and moralism, incensed by what they view as unjustified profligacy in the European South. Contractionary policies may create a self-reinforcing spiral of decline that increases the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Yet, while some EU policies are punitive or counter-productive, the strength of opinion of pundits long on conviction and short on detail seems to ignore the real root cause of the crisis. This is that the Greek economy has become inward-looking, unproductive, incumbent-favouring, and rife with rent-seeking. They may also underestimate how Grexit would exacerbate many of the Greek pathologies at the root of the crisis.

Greece’s main problem isn’t its currency. Rather, it is that its Byzantine regulations and institutional uncertainties discourage investments and reduce competitive pressures. Grexit would further restrict available capital, shatter the fragile banking sector, and increase the investment gap, which, as McKinsey’s recent study shows, is the key issue.

If the euro is not the problem, then returning to the drachma is not the solution. (Greece’s labor costs have already fallen 40%, exports have fallen, and currency devaluations in the 1980’s and 1990’s were unable to boost competitiveness.) Also, as a recent E&Y study confirms, a new currency now would create unimaginable legal and economic havoc. It would also massively boost inequalities, with wealthy Euro hoarders benefitting while the poorest struggle in a crumbling state.

Political sympathies may have led some progressives to accept all too readily the leftist rhetoric of Syriza, which has proved to be the most conservative government in memory ̶ in the literal sense of the term. The remarkably few laws passed over the last six months have only aimed to restore pre-crisis bankrupt practices. For all Syriza’s talk of “social justice”, only €200 million were granted to cope with Greece’s humanitarian crisis. Meanwhile the €600 million yearly annual government subsidy for pensioners of the partly private electricity utility DEI has been protected. Hardly surprising–DEI’s union has strong Syriza links. And while Syriza spoke out against “oligarchs”, precious little has happened either on the tax evasion front, or on combatting oligopolies; opening markets to competition was readily demonized as “neoliberalism.” As for the real economy, November’s 1.8% growth turned into August’s 3% recession. And while the last few days a sense of pragmatism seems to have returned to the Greek side, easy rhetoric can still derail the deal, and obfuscate reality.

It is worth noting that the overwhelming majority of Greek economists both in Greece and abroad (including Nobel laureate Christopher Pissarides), regardless of political leanings, have a fairly consistent (if less sexy) set of views: they believe that Grexit would have catastrophic short and medium-term impacts; that structural reforms, such as those Syriza is still trying to forestall, are indispensable; and that these reforms are needed to protect Greece from rent-seekers, large and small. Yet the voices of a few visible economists, possibly motivated by worthy objectives and agendas, often drown out such grounded views, inadvertently legitimizing reckless policies and an inept government.

An irony surfaces here. Paul Krugman, the least equivocal voice in the crisis, famously pointed out in 2009 what he saw as the root cause of the demise of economics. “Freshwater economists” (theory-driven modelers, with firm ideas on how the world worked), he argued, dominated “saltwater economists” (who were more empirically driven), mistaking theoretical integrity “clad in impressive-looking mathematics, for truth…” He argued that “economists… will have to learn to live with messiness.” This is a lesson worth remembering. Progressive pundits may do their cause, and Greece, a serious disservice by inasmuch as they draw on their own theoretical preconceptions, rather than looking at the messy reality on the ground.

The Greek problem is tough, but tractable–provided we focus on cleaning up the messiness of its root causes, rather than seeking the comfort of abstraction, the ease of rhetoric, and the purity of ideological binds. While the current deal, tough as it is, might have the opportunity to stabilize the country, the tumult of the elections can throw everything up in the air again. Global pundits, once again, may find themselves shaping the fate of a small country, far away from their comfortable desks. Let’s hope they will appreciate that with power and influence comes responsibility.

As we look to the turbulent weeks ahead, we need to remember that Greece is no place for freshwater economics, whether of the conservative or the progressive kind. It’s as salt-water as you get.

Research: For a Corporate Apology to Work, the CEO Should Look Sad

“Straight up, we made some mistakes,” Whole Foods co-CEOs John Mackey and Walter Robb said earlier this year in response to an overcharging scandal.

“We weren’t prepared for the crisis and we dropped the ball,” wrote AirBnB CEO Brian Chesky in 2011, after a guest trashed a host’s home.

“This should never have happened. It is simply unacceptable,” said Mary Barra, CEO of GM, in one of several public apologies in the wake of safety scandals at the automaker.

The corporate apology, once a relative rarity, has become a normal part of business discourse. Stuff happens, and then we say we’re sorry for it. But just because corporate apologies have become commonplace doesn’t mean they’re all created equal.

Two new studies shed light on what makes some apologies effective, and what makes others backfire.

First, Leanne ten Brinke of the UC Berkeley Haas School of Business and Gabrielle S. Adams of the London Business School examine how expressions of emotion affect corporate apologies. Publishing in the journal Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, they present the findings of two studies.

In the first study, they looked at how investors reacted to real apologies from executives. They examined 29 online videos of apologies made between 2007 and 2011. Using an established system for distinguishing facial expressions (the Facial Action Coding System, or FACS), their researchers watched each video second by second, without sound, and tracked the expressions that flitted across the executives’ faces. Were they frowning? Smiling? Looking sad? Then Brinke and Adams looked at what happened after the apology to the company’s stock price. They found that for those leaders who had apologized with a smile, the stock dropped—perhaps because the leader seemed insincere delivering his apology, or even seemed to be enjoying the suffering his company had caused. The more the person smiled, the worse his company performed.

For the leaders who appeared genuinely contrite, at first it seemed like there was no impact on stock price—the company neither performed worse, nor performed better. “Normative emotions simply allow the company to move forward,” they write.

But then the researchers took a closer look at CEO apologies, specifically—16 out of the 29 cases. They found that when an apology was delivered by a CEO who looked sad, the company’s stock price actually rose post-apology. “A good apology can build investor confidence,” especially in the long term.

To investigate this further, Brinke and Adams conducted an experiment in which they hired an actor to portray an airline CEO apologizing for a computer malfunction that canceled 140 flights, stranding thousands of passengers—a scenario based on a real Alaksa Airlines snafu. They made sure his fictional apology contained all the verbal elements of a good apology—the components previous research has identified as being central to repairing relationships (see sidebar). They then recruited subjects to watch this fictional CEO apologize—either happily, sadly, or neutrally. When the CEO appeared sad, participants rated him as more sincere and were more likely to want to reconcile with him. When the CEO delivered his apology with a smile on his face—or, interestingly, a neutral expression—the study participants were less likely to trust him, and the apology even seemed to exacerbate their negative feelings.

The 5 Elements of a Complete Apology

An effective apology includes up to five elements, according to psychology researchers.

An explicit “I’m sorry.” Linguists call this an “Illocutionary Force Indicating Device.”

An offer of repair. This is where you offer to make it up to the person, eg, “I’m so sorry I spilled on your suit, can I pay for the dry cleaning?”

An explanation. Here’s where you explain how the mistake happened. But, it’s important to note that a complete apology also includes…

Taking responsibility. Without this, an explanation just sounds like an excuse.

A promise of forbearance, eg, “I promise it won’t happen again.”

Even seasoned leaders are likely to find delivering an apology to be an uncomfortable experience, and when we feel uncomfortable, a normal reaction is to grimace, laugh awkwardly, or even try to break the tension with a joke. Leaders (especially Americans) may also feel they can’t show too much sadness or anguish but instead must present a positive front at all times. The research by Brinke and Adams reminds us how these understandable impulses can backfire.

Another paper appearing in the Journal of Corporate Finance adds an interesting wrinkle to this subject. Researchers Don Chance, James Cicon, and Stephen P. Ferris examined 150 press releases from 1993 to 2009 to examine how companies fared when they blamed themselves for poor performance as opposed to blaming external factors. They found that while companies are twice as likely to blame external factors when things go wrong, passing the buck results in continued financial decline. Conversely, companies that take responsibility for their missed earnings stabilize and eventually see an uptick in financial performance. (Interestingly, both groups were about equally likely to fire their CEOs.)

Why? After eliminating numerous factors, the researchers conclude that being honest and specific about the source of the problem—both characteristics of self-blaming statements—not only cheers up investors, it likely helps the company turn around the issue more quickly. Conversely, the companies who blamed external factors were often vague (blaming “economic forces” for instance) and seen as less honest (since many of their wounds had actually been self-inflicted).

The message is loud and clear: when you mess up, admit it. And look appropriately sad about it.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers