Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1256

August 31, 2015

Is Overwork Killing You?

Kenneth Andersson for HBR

Every time the conversation turns to overwork, which is often these days, I think of Arthur (a pseudonym). When I met him, long ago, he was picking himself up after a tough year. A seasoned CFO with a sharp mind and an abrasive style, Arthur had lost his job over a disagreement with his company’s new CEO.

He had not seen it coming and it struck hard. “I hadn’t realized how much I cared, how much work mattered to me, until then,” he explained, sharing a feeling I have heard many a manager describe. The unexpected pang of loss he felt when his work email was deactivated. He had cleared his desk defiantly, but now, his once-overflowing inbox dry, he was overwhelmed with grief.

Arthur did not see himself as a workaholic. He had hobbies, spent plenty of time with family and friends, and kept his passion for work well hidden under a cynical foil. “I could quit at any moment, I told myself.” It was a lie. “Losing my work almost killed me,” he thought at first. But when he still felt scarred despite new opportunities, he realized that work had “almost killed” him long before — when it became his life.

I thought of Arthur when Steve Balmer chose the romantic Dirty Dancing theme song “Time of Our Lives” to bid Microsoft farewell, and again more recently, reading about the controversy that the New York Times exposé of Amazon’s corporate culture stirred up.

It is not the first time that a popular story has ignited a debate on the future, or more precisely the present, of professional work. Similar controversies have erupted in recent years following the publication of Anne Marie Slaughter’s essay “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” or news of an investment bank intern’s death. Each time we deliberate whether the blame for overwork rests on unrealistic individual ambitions, brutal organizational cultures, or both. Each time we ponder, in essence, whether senior management, banking, consulting, entrepreneurship, and statesmanship are compatible with human life.

Is it because the public cares so much about the health and families of elite professionals that these stories provoke so much debate? Hardly. While debate often swirls around the most dramatic anecdotes, we do not swarm to these stories as works of social science. As Fortune‘s Mathew Ingram suggests, we resonate with them because they portray familiar experiences. Their protagonists’ workplaces have the truth of fiction, so to speak, lending words and faces to the workplace in our minds.

In a memo to all Amazon employees, CEO Jeff Bezos argued that the Times’ story could not possibly reflect a company whose people “are recruited every day by other world-class companies, and … can work anywhere [they] want.” This argument sums up a common refrain about extreme work cultures. Those who can thrive in them want them. Those who do not can go elsewhere.

The truly talented, we are told, flee obligations to work themselves into the ground. And yet they appear to love opportunities to do so, if presented in the guise of solving big problems, learning, and pushing themselves further.

Whether we are forced to or choose to work too much, however, a growing body of research suggests that working long hours damages our health, productivity, and families. A recent study suggests that it might be a factor in 120,000 deaths a year. Research also shows that people often use devices and policies meant to increase autonomy to take work home and work around the clock. While organizations wage wars for talent, it seems talent is at war with itself.

Given the physical and social harm that overwork can do, and the productivity losses organizations suffer, why do we keep at it? To answer that question, I believe, we need to look beyond personal ambitions and corporate incentives and norms, and look at our relationships with work itself.

I (Over) Work Therefore I Am

Over the past decades, people’s attachments to organizations have become more tenuous. This loosening of long-term bonds has brought more uncertainty to all workers, and more freedom to a fortunate few. But as organizations have arguably become less significant, work has become more so. It is far more valuable — both economically and psychologically — to be defined by my talent and abilities than to be defined by an organization. Being a “talented coder” can outlast being a “Googler.”

As a result, commitment to work is no longer the consequence of organizational loyalty. It is an expression of talent.

This shift still allows organizations to exact commitment by offering that precious appellation, “top talent,” in return. Seen as a ticket to thrive in a mobile job market, “talent” is an ever more valuable label, and devotion to work is that ticket’s price. No wonder companies that churn their workforce and squeeze them to the ground claim to hire only the most talented.

Reflecting and sustaining this shift to a more personal relationship with work is the current obsession with passion, authenticity, meaning, and the like in popular management writing (including my own). This more intimate relationship with work makes it both more rewarding and more exposing. Where once only artists lived to work this way, now more and more of us do.

This suggests that some insight into the creeping feeling that work asks too much of us might be found in the commentary that follows popular artists’ struggle and demise. When someone like Kurt Cobain, Amy Winehouse, Heath Ledger, or Phillip Seymour-Hoffman passes away, the commentary that accompanies our mourning hardly pays any attention to organizations — to the studios and media companies on whom their careers nevertheless depended. They highlight instead a passion turned into obsession, talent ravaging a soul, the consuming nature of their work. Remembering Robin Williams upstage a fireworks display with an impromptu performance, a critic once wrote, “Whether or not anyone expected him to be, and maybe whether or not he entirely wanted to be, he was on.” Williams himself put it starkly, describing his gift of creative expression: “Some people say it’s a muse. No, it’s not a muse! It’s a demon!”

Those statements are close to the experience of many managers I meet. The work they fear might kill them is that which also makes them feel alive. Had I met Arthur at work before he was fired, he assured me, I would have found him if not quite fulfilled, at least always full of life — immersed in the excitement of pursuit, the satisfaction of accomplishment, the anxiety of deadlines, the frustrations of politics. All the while being consumed by them, too.

It is not the anomie of impersonal demands that saps us then, once work becomes a passionate pursuit and a form of self-expression. It is the striving for virtuous authenticity in every work performance. We become authentically drained, and vulnerable too.

The parts of us that die, symbolically, are those not tied to work. And as that happens, working becomes a matter of life or death.

The Passion of the Worker

In an age where talent, passion, and authenticity are hailed as virtues and antidotes to the uncertainty of the workplace, so-called overwork may well be their dark side. As we are urged to have a romantic, rather then instrumental, relationship with work, we should not be surprised that it threatens our families, our productivity, and our health. Romance has long been known for making us lose our minds. It is no different when work is involved.

Seen this way, overwork is not defined by the amount of our day work occupies but by the amount of our selves tied up to it. We “over” work not when we work too hard but when working becomes less of a means and more of an end. When meditation, exercise, sleep, holidays, and even parenting, are cast as tools to make us better workers.

This view explains why we ignore, apparently irrationally, that overwork erodes productivity. In a workplace that has co-opted the accouterments of romance and religion, where CEOs have visions and passionate managers are work martyrs, productivity is not the only aim. Passion, after all, has no concern for efficiency and martyrdom has never been about getting things done. Both have always been about expressing virtue and devotion. And people have long endured pains and trials to claim a valued self, with the belonging and expression it affords.

Neither, this view suggests, are we helped by the argument that more humane workplaces will make us more productive. That subtly reinforces the already totemic notion that being productive is the purpose of being human, and the taboo that surrounds the idea that one might work to afford a life elsewhere. Nor can data help much. What if it showed that a certain category of people, who were raised with and define themselves by overwork, were more productive that way? Should we endorse it then for everyone? Who gets to say when is it enough?

“Workers themselves,” is the common response, as I’ve noted above. They can vote for the fitness of corporate cultures with their feet, and move to friendlier ones. Many young professionals appear to have embraced this mantra, and often see large, prestigious companies with extreme work cultures as temporary homes. Stints in such workplaces, MBAs often tell me, are like going to boot camp while paying off your student loans. It is extremely intense, it prepares you for all circumstances, and it is not meant to last. One can always do something more meaningful later.

But though these jobs pay well, money is hardly the only, or even the major, reason most new MBAs work there. Research shows that managers choose to work for those companies early in their careers not because they pay well, but for the future opportunities stints there might afford.

Put another way, those companies don’t have to pay young professionals more, and need not promise them loyalty, to get them to (over) work there. While career ladders are disappearing, companies still provide a stage for workers to claim and display talent — much like media companies do for gifted artists. That makes them not insignificant, as talent moves around, but indispensable.

And these early career stints are not simply Faustian bargains. If a company is so appealing and influential that it is good for you to work there even if you don’t mean to stay, it is also likely to shape your attitude to work. Going to boot camp, as I remind my students, does prepare you — for war. Those organizations often serve as what Jennifer Petriglieri and I have termed “identity workspaces.” They shape people’s identities and work ethics, influencing working cultures, and casting their shadow long past people’s membership in them.

This is why the argument that talent shortage makes extreme work cultures unviable does not hold up. The opposite is true. Our conception of talent as a path to salvation and rapture in mobile labor markets makes more people embrace those cultures, anxious to prove that they are among the few to have the talent said to be so short. And those conceptions and cultures shape how we work, who we become, and the price we pay for it.

Things will only change when we stop treating passionate overwork as a marker of talent, and companies with extreme work cultures as the main suppliers of it. Until then, we’ll keep hoping that work gives us Stendhal syndrome, and end up suffering the Stockholm one instead.

Relax, Turn Off Your Phone, and Go to Sleep

As a child, I was a terrible sleeper. My parents would often find me awake at 3 AM with a flashlight under the covers reading a Hardy Boy, Nancy Drew, or Tom Swift book. When I was 9-years-old, my pediatrician prescribed an awful tasting medicine to be taken at night, mixed with pineapple juice to mask the flavor. Years later, I found out that the medicine was actually a heavy duty narcotic, sometimes called a “Mickey Finn.” Needless to say, I was just never a good sleeper. In my adult years, I often explained away my sleeping habits by swearing that 4-5 hours of sleep a night was all I needed.

My colleagues and I at California State University, Dominguez Hills, conducted sleep research that stems from my lab’s work on the “psychology of technology,” where we have discovered two important variables that encourage us to use (and misuse) technology, thereby losing sleep: (1) poor executive functioning, which includes our (in)ability to pay attention, problem solve, control our impulses, and make decisions, and (2) anxiety. In our work, anxiety is sometimes referred to as FOMO, or the fear of missing out. We see this anxiety in the majority of smartphone users who feel uncomfortable if they are not in direct contact with their phones — and their many electronic connections — 24/7/365. A dead battery and no charger can bring upon a panic attack.

In our new, yet-to-be-published study of more than 700 college students, we found that while poor executive functioning did predict sleep problems, the stronger effect was actually due to anxiety. The students who were more anxious about being apart from their phones used their phones more during a typical day, and woke up to check their phones more often at night. The latter two results — more daily smartphone use and more nighttime awakenings — led directly to sleep problems.

Why does anxiety about needing to stay in contact negatively impact sleep? First, those who are anxious about staying connected are more likely to use their technology right up until bedtime. We now know that the blue wavelength light from LED-based devices (phones, tablets, computers) increases the release of cortisol in the brain, which makes us more alert, and inhibits the production of melatonin, which is needed to fall asleep. That’s why The National Sleep Foundation recommends turning off all devices an hour prior to bedtime. The Mayo Clinic says that if you do choose to use technology during the hour before bedtime, keep it 14 inches from your face and dim the brightness, which helps reduce the blue light and increases the natural melatonin release. A study by researchers at Harvard Medical School found that compared to reading a paper book, people who read from an e-book needed an additional 10 minutes to fall asleep. They experienced 90 minutes of delayed melatonin onset — and had half the amount of melatonin released. They also had diminished rapid eye movement sleep. To compound these effects, anxious people have more cortisol in their system, which further stymies sleep. Anxious people also tend to have shorter attention spans — our own research has shown that they switch tasks every 3-5 minutes. This frenetic task switching increases stress — and cortisol — creating a vicious cycle. Finally, anxious people are more likely to sleep with their phone close by and check it when they awaken at night, which then further disrupts sleep.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Managing Stress at Work

Managing Yourself Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Consider how vitally important sleep is to our health. In the 1950s and 1960s, William Dement and Nathaniel Kleitman illuminated the process of sleep. Basically, for normally well-rested people, sleep happens in a series of 90-minute bursts, each ending with a dream. Leading up to the dream are four critical phases responsible for synaptic rejuvenation, or the process of pruning away unneeded mental connections and consolidating or reinforcing needed ones. In addition, various molecular byproducts of thinking are left in the brain throughout the day, which are then washed away during normal sleep. Included among these are beta amyloids, which have been found in abundance in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. (For more on the relationship between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease, see this brief.) When you are not well rested, these phases — and the brain’s housekeeping chores — are disrupted. Further, if you awaken someone every time they start dreaming, they will soon skip the four phases and go straight into REM dream sleep, reducing synaptic rejuvenation.

The National Sleep Foundation has shown that we are in the midst of a 50-year decline in sleep duration, and one study found that 90% of Americans use their gadgets within the last hour before bedtime at least a few nights a week. They also found that the average college student loses 46 minutes of sleep each night due to answering phone calls or checking for messages. Add it all up, and we are all running the risk of a massive sleep debt that is not going to allow our sleeping brain to do its job. Sleep deprivation is leading to less efficient learning, higher emotionality, increased anxiety, and a less efficient brain.

So how do you reduce your nighttime anxiety and permit your brain to sleep effectively? Here are some suggestions:

During the day, practice not reacting to incoming alerts or notifications like one of Pavlov’s dogs. Don’t check your phone every time it beeps. In fact, turn off notifications and check on a schedule to retrain your brain’s neurotransmitters (particularly cortisol). Start by checking every 15 minutes, and gradually increase that to 30 minutes or more. Tell your family, friends, and colleagues that you may not respond immediately, but you will within a specified amount of time, such as 30 minutes to an hour later.

Stop using all devices one hour prior to sleep.

Put all devices away in another room rather than keep them in the bedroom to discourage you from checking them during the night. (If you must keep a phone nearby in case of emergency, set it so that it only rings when certain people are calling, but still place it across the room and away from your bedside.)

An hour before bedtime, start dimming the room lights slowly to release melatonin.

During the last hour before bedtime, choose an activity that your brain will find predictable and, thus, not anxiety-provoking. Consider any of the following:

Watch a television show that you love, maybe even a repeat.

Read a paper book (or use a Kindle which doesn’t emit blue light) by a familiar author.

Listen to music that is very familiar like a playlist of your favorite songs. If you need a device to do this, burn CDs and get a CD player. (The key is to use a device that doesn’t have internet access, email, or a phone.) Keep the volume low.

If you awaken in the middle of the night, try this trick: have a song lyric in mind (not the whole song) that you plan to sing in your mind over and over to block the anxiety and allow you to fall back to sleep. Another option is to learn one of many meditation techniques and practice and use those skills to calm your mind.

Our devices are a gift that connect us to so many people and so much information, but they do not have to raise our anxiety and harm our all-important sleep. We need to control our devices, rather than letting them control us.

Why Your Employees’ Suggestions Aren’t Going Anywhere

A lot of companies use an ever-more-sophisticated array of online social tools in an attempt to connect their people, get a flow of ideas going, and spur innovation. But after an initial flurry of activity, the initiatives often fizzle and the new tools get tucked away somewhere. What goes wrong? Why is the goal of a more collaborative and innovative organization so elusive?

Consider a real example: Not long after a company created an online suggestion box on its new intranet, with all the bells and whistles of the latest social-media technologies, an executive lamented: “All we get are a bunch of complaints and impossibly wild ideas that we couldn’t follow up on in a million years.”

And there lies the problem. The span of ideas and suggestions on internal social platforms is often so extensive that follow-up is impossible. When ideas are ignored, or at least appear to be, people quickly get discouraged and stop contributing.

The solution is as simple as the problem: Put the resourcefulness and creativity of your people to meaningful and specific use. This particular company reversed the function of the suggestion box. Rather than treating it as a receptacle for whatever anyone wanted to talk or complain about, the company turned it into a “solution” box — a place to get help solving specific problems or capturing new business opportunities. Employees are individually invited to participate. Some are chosen randomly; others are picked on the basis of their experience and past practical insights about the topic.

The company’s leadership team launched the solution box by posing a question, via email, to several hundred employees: “What is the best way to show appreciation to our new clients for their business?” They were invited to propose practical solutions and to bring in other people who might have good ideas or experience to share. For inspiration, the email included an example of an appreciation gift sent by a well-known company.

Within hours, a lively online brainstorming session was underway. After several promising ideas were identified, all employees were asked to vote on their favorite idea by “liking” it online.

The resultant product was nothing earth-shattering. It was a personal letter from one of the business directors along with additional support (free of charge) to get the client up to speed using the company’s products and services. The real benefits extended well beyond the letter and support offered. Employees who participated gained a better understanding of their purpose to serve clients, and they felt more engaged. As one participant put it, “It was great to help the company along and to know that the results of our efforts can be seen in such a short time.”

Or take the example of a large industrial group we worked with. Rather than determining the attractiveness of a certain customer segment using a traditional approach of gauging size, growth rate, competitor positions, and profitability, the head of global marketing used social-enterprise tools. He began with a simple, direct question to the people closest to the markets, his sales and account managers: “If from now on you could serve only one segment, which one would you choose … and why?” As their opinions flowed in, with everyone bouncing ideas off one another, he asked them to rank the three segments they believed would have the most potential in the next five years. Their answers reflected consensus around certain segments and pointed to others that deserved further investigation.

There is significant value in expressly inviting participants into a discussion rather than sending blast emails. People tend to rise to the challenge of an individual invitation and take responsibility for passing it on, even if they know they were selected at random. But don’t keep your invitation list too short. It’s important to be generous with the invites, in order to get sufficient capacity and cross-functional expertise. And to get the most enthusiasm from the participants, don’t appoint people; simply ask for their help.

Social and collaborative tools alone do not create a flow of ideas and innovations. But they can be effective in getting people to put their minds to problems and offer ideas for consideration. To access a wealth of untapped employee potential locked up in departments and functions, all you have to do is ask the right questions.

6 Ways to Reduce the Stress of Presenting

In the past 30 years, I’ve given more than 3,000 speeches to audiences across the world. Presentations have been such a central part of my work that many who know me best have been surprised to learn how much anxiety they used to cause me. After my fourth root canal, my dentist pointed out that I appeared to be grinding my teeth at night. He suggested a mouth guard. Over the next few years, I ground through three of them. Fortunately, materials science advanced faster than my grinding and I eventually received a more durable one. Still, I had almost resigned myself to the fact that fitful sleep, restless legs, and a variety of aches throughout my body were the price of the career I had chosen.

I knew I had turned a corner 10 years ago when I was invited to speak to a prestigious business audience at Radio City Music Hall. I slept peacefully the night before. And when I stepped through the crimson curtains to face 6,000 nattily dressed executives, my former panic and dread were replaced with a sense of exhilaration and gratitude.

As I came to realize that presentations would be a permanent facet of my career, I began accumulating tactics to increase my pleasure while reducing the pain. Here are six that have made an enormous difference for me:

1. Bless, don’t impress. I discovered that much of my stress was more about my motive than the event. I would fret and stew more about what I imagined people would think of me than whether I would effectively serve them. I was most stressed when my motive was more about looking good than doing good. I recall pulling to the side of the road in the hills above Silicon Valley on the way to a retreat with a tech executive team that I was especially worried about. I asked myself, “Why am I doing this?” As I looked out at the Valley, the tightness in my chest disappeared. A sudden clarity overtook me. My errand was not about me — it was about them. I focused on the important ideas I hoped to share. I no longer cared if I did it perfectly — I only hoped I would do it well enough that they would be blessed by the experience. My stress subsides when my motive is to bless rather than impress.

2. Rehearse, but don’t obsess. I’ve learned to discern when over-rehearsing is counterproductive. I provoke more stress in myself when my preparation moves past the point of diminishing returns. When it’s an obsession, not preparation, it’s time to simply disconnect and engage in some distracting activity. If I am giving a new presentation I will practice it three times: Once when I finish preparing it, again the day before, and finally a few hours before I go “on.”

3. Create rest stops. For three weeks prior to my first three-hour-long presentation, I could hardly digest my dinner. How could I possibly avoid losing my place for so long? I later discovered that while a 180-minute presentation can seem like an uncrossable minefield, a series of 10 minutes chunks feels more doable. I began to organize my material in smaller chunks that built logically on one another.

4. Make it a conversation. A related discovery that brought relief was that audiences hate protracted monologues almost as much as I fear giving them. Audiences disengage when your monologue yawns on. There are hundreds of clever ways to engage the audience that amplify the persuasiveness of your presentation, relieve the tedium of a lecture and reduce your anxiety by giving you rest stops. I combined this and the previous insight by breaking all of my lectures into small chunks separated by brief, relevant and topic-appropriate involvement activities.

You and Your Team

Stress

Don’t let it get the better of you.

Involvement activities can invite participants to think with you, feel with you, help you, or try something with you. For example, you could share data and invite the group to make sense of it with you (think); show a brief video that provokes relevant emotion on your topic (feel); ask someone to read a pertinent quote from an expert and comment on it (help); or attempt a skill you’re teaching in a safe and structured way (try). I’m often told that “sophisticated groups” don’t want to be involved. That’s baloney. They don’t want to be involved in silly or worthless ways. But they love a structured task that is relevant to the topic that makes them feel smart and respected.

For example, when I’m teaching the skills of our Crucial Conversations Training to an executive team I start out by pairing them up and asking them to show how they’d respond to an abusive physician in a brief video clip. I limit their response to one sentence, so they don’t feel they have to take on a dramatic role — and allow them to be playful if they prefer, rather than serious. That interaction anchors the subject I want to involve them in and warms up the room immediately. It also takes the pressure off of me for a moment while I get my bearings.

5. Know thyself. There’s nothing intrinsically stressful about a presentation. The stress is usually self-induced — often because it triggers some trauma you carry from a painful life experiences (i.e. the audience snickered when you squeaked rather than sang during a choir solo in third grade) that your mind conjures a connection to. Over time, I became aware that my self-imposed demands for perfection and craving of universal approval were my primary generators of anxiety. As I’ve developed sources of peace and a sense of worth that are independent of these unattainable goals, I’ve found it easier to focus on blessing and surrendered the need to impress.

6. Breathe. Psychologist Amy Cuddy gave me a very practical stress-reduction tool. In controlled experiments, she demonstrated that before entering a high stakes meeting, you can substantially reduce stress hormones in your blood by simply breathing deeply and slowly while assuming a powerful pose (think Wonder Woman or Superman). When last minute jitters take over, I’ve found a bathroom stall and used this one to great benefit.

Over the years, these tactics have helped me learn to connect in a meaningful way with groups, turning once-stressful presentations into some of the most gratifying experiences of my life. As I’ve learned to get out of my own head, ground myself in more intrinsic sources of worth, connect to my deeper motives for sharing, and just breathe, the experience of standing in front of an audience is no longer a curse, but a blessing to me.

August 28, 2015

Female CEOs Find Stock-Based Pay Harder to Get, Easier to Lose

It’s long been a complaint in populist corners that chief executives receive huge stock-based payouts — even sometimes when their companies don’t perform that well. Well, researchers have now discovered an exception to both rules: women.

We already know that a) only a tiny minority of chief executives at large companies are female, and b) they earn less overall than their male counterparts. Now, new research by Stefania Albanesi, Claudia Olivetti, and María José Prados also looks at what happens when company performance changes, and examines stock-based pay in particular — often the biggest, but least-public, component of an executive’s compensation package. What they found is that female senior leaders were rewarded more weakly with stock-based pay when their companies improved, and are penalized more harshly when their companies stumble.

Looking at compensation data from S&P 500 companies between 1992 and 2005 — which, admittedly, feels light-years away in terms of the current executive pay debate, but disclosure rules changed in 2006 and affected the data-set — the researchers examined compensation for CEOs and chairs, vice chairs, COOs, CFOs, and company presidents. This gave them a sample of over 40,000 executives. Only 3.2% of these were women.

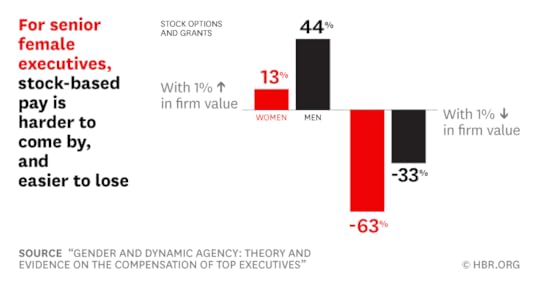

Women earned less across the board in all the forms of compensation the researchers examined — including salary, bonus, restricted stock, stock options, and stock grants, among other payments (including long-term incentive plans). The researchers observed some of the starkest disparities in what happened to the stock options and stock grants — the chunks that form the bulk of senior executive compensation, and which they shorthand as “firm-specific wealth”— when company performance changed.

The men — on average — were more rewarded when their firms succeeded, and less penalized when their companies stumbled. ”A 1% increase in firm value generates a 13% rise in firm specific wealth for female executives, and a 44% rise for male executives, while a 1% decline in firm value generates a 63% decline in firm specific wealth for female executives and only a 33% decline for male executives,” they write. That means that while women get less than a third of what men get in the boom times, in the lean times they’re penalized twice as harshly.

Here’s how that works out in dollar terms. ”A $1 million increase in firm value generates a $17,150 increase in firm-specific wealth for male executives but only a $1,670 increase for females.” That’s more than a 10x difference.

The message is clear: Female CEOs see less upside and more downside.

Why? While some general differences have been found between working men and women — such as women’s relative lack of mentoring, smaller professional networks, their greater responsibilities outside the home, and greater reluctance to negotiate and to embrace risk — I have a hard time believing that these explanations really apply to the tiny elite cadre of women who have fought their way to the top. (And who, despite earning less than their male peers, certainly still earn more than enough to smooth the rough edges of housework and childcare.)

And having spoken with lead researcher Stefania Albanesi, the research team seemed hesitant to chalk it up to those explanations too. After all, they found no difference between how the women’s companies performed and the men’s — if these female chief executives were bad negotiators with small networks who left board meetings early to fold laundry, it would probably show up in their companies’ performance data.

But there is something going on here — some mechanism by which our culture’s persistent sexism gets transmuted into less money, even for the highest-earning women. Previous research has shown that, in an era when all executives are under fire for how much they earn, many have learned to hide it. Salary and cash bonuses are tougher to obscure from the public eye, while stock options and grants are not only easier to conceal, but taxed at a lower rate and can be structured to minimize any downside — deals can be made so that the executive gets stock-based pay as long as the company’s share price goes up, even if it is underperforming its industry or peer group.

But to get sweet deals like that, it helps to have strong networks, long tenures, and lots of clout. The researchers conclude that female executives, who tended to be younger and have been in their companies for less time, “might be considerably less entrenched and exert lower control on their own compensation than their male counterparts.” In other words: they’re less powerful.

Why Won’t My Employees Admit They’re Going on Vacation?

Andrew Nguyen/HBR STAFF

As another summer comes to a close, I find myself noticing once again that my co-workers and employees have been very reluctant to both commit to a vacation and to communicate that time off to everyone else.

As CEO, I find this frustrating — it’s a waste of time to set up a client visit or an internal meeting only to hear from one of the essential participants that he or she will be on vacation. We have asked, even pleaded, that people mark the days when they will be away, even if they are still tentative. To be fair, some of my colleagues, with a degree of self-confidence and consideration, do indicate their days off well in advance — but the practice of the stealth vacation still persists.

And yet I realize that my company is hardly an exception. Studies consistently show that Americans are vacation-phobic, leaving as much as half of their annual paid vacation on the table. The reasons cited include an aversion to piles of work on return, the fear of being replaced, or a “martyr complex” that holds that the office can’t run smoothly without me. Of course, martyrs beget more within an organization, creating pressure on others to exhibit the same self-sacrifice.

And in our industry – financial services – this attitude may be even more pervasive. At the financial institution where I spent 22 years before co-founding Aureus, I would sometimes run into one of the veteran fund managers in the lobby of our building, as I was about to take the elevator up to our offices. He would describe with obvious bravado how he had already been at the office for at least an hour, getting tons done, and was now getting back from grabbing some coffee. I would stand there, at 7:45 a.m., feeling jealous and inadequate — exactly the intended effect.

So now, as a leader, I try to encourage people to take a break and get away from the office. No one has ever been denied a vacation, even at a challenging period – for example, one month into their employment or during the first two weeks of the year (which are very busy at our firm). We try to be generous as well as flexible about paid time off, offering three weeks of vacation for new employees, which increases over time to five weeks at twelve years.

What do we expect in return from our staff? That we try to avoid all taking off the same weeks during the summer and in the days around Christmas, and that everyone post their vacation, as soon as planned, on our shared Outlook calendar. But based on the actual notices on the schedule, we are failing miserably at convincing everyone to comply with this request.

To solve this problem, we’re trying to focus more on teamwork, collaboration, and coordination. This isn’t easy in an industry that often prizes grueling hours and extreme work devotion, in which one of the key measures of value to the firm is the perceived number of hours in the office and the fewest hours away from work. People who come up through such cultures may be used to concealing their time off – and rewarded for doing so, some research has found.

To counteract this culture of anxiety and hiding, I have made an effort to be very clear about my own vacation plans and have encouraged other senior staff to do the same. Part of this is about trust — in our collaborative work environment, a large part of our success hinges on the dynamic nature of small group debates. Those debates can only happen in a culture of mutual respect and trust. The lack of transparency about when we are in the office undermines that mutual trust.

We have also begun to include a discussion of who will be absent over the coming two weeks, either for business travel or vacation, in the agenda for our only weekly staff meeting. This is a helpful summary of who will be available over these days, but it also puts subtle pressure on my coworkers to participate in the program.

It seems counterintuitive to make acknowledging a vacation a stressful event, but once we are all comfortable with accepting our own need for time off, I am sure the guilt will disappear. If people have to sheepishly admit that they were planning on being off later this week or next week, it’s not as if they are coming clean about a coke addiction. It is just vacation — and they deserve it.

Maybe if we complete a single quarter when all vacation days are posted in advance, I’ll give the whole company an extra day off.

And order everyone to take it.

The Company Cultures That Help (or Hinder) Digital Transformation

Many companies struggle with digital transformation. It goes against the grain of established ways of working and is a threat to management practices that have existed for decades. Digital tools free people throughout the organization to share information easily. Communication managers no longer have total control over message, target, and timing of news and announcements. Horizontal and bottom-up information flows become stronger at the expense of the traditional top-down.

Digital lets expertise emerge naturally as people ask and answer questions peer-to-peer. People build up reputations across the organization as the “go to” person for topics even if they are not the official experts. This bypasses HR’s system and procedures for validating experts.

IT management risks losing control over enterprise technologies because in a fast-paced business world, teams — unwilling to wait for IT to rollout official solutions — solve their own needs quickly by resorting to cloud-based, consumer tools to manage projects and share information.

Personal branding worries management, as people who are active on the internal social network become “stars,” with greater name recognition inside the company than certain top managers. These de facto thought-leaders become a force to reckon with that is completely outside the hierarchy.

And yet despite all of these “threats,” some companies embrace the changes digital offers. What sets them apart?

To figure out what makes the transition easier for some companies than others, I have conducted several surveys with organizations around the world over the past nine years. I have grouped the toughest obstacles to change — those considered to be serious and holding us back — into five categories:

Slow or stalled decision-making caused by internal politics, competing priorities, or attempting to reach consensus.

Inability to prove business value of digital through traditional ROI calculations, resulting in lack of senior management sponsorship.

Too much focus on technology rather than willingness to address deep change and rethink how people work.

Lack of understanding operational issues at the decision-making level and difficulties when going from theory to practice.

Fear of losing control by management or central functions, and fears that employees will waste time on social platforms.

Work cultures can either accentuate or alleviate these obstacles. The 2014 survey participants rated their internal work cultures on a five-point scale for the following opposing characteristics:

Strong, shared sense of purpose vs. weak, inconsistent sense of purpose

Freedom to experiment vs. absolute compliance to rules and processes

Distributed decision-making vs. centralized, hierarchical decision-making

Open to the influence of the external world vs. internally focused and closed to the external world

These characteristics are not mutually exclusive, obviously, but data show that organizations tend to be stronger in one area rather than the other three. Out of 280 organizations, 66 indicated the highest level for one of the four characteristics,19 for two characteristics, eight for three, and none for all four. This minimal overlap lets us refine our understanding about which characteristic alleviates or accentuates which obstacles:

A strong, shared sense of purpose alleviates many obstacles, especially those of internal politics. A strong sense of purpose alleviates political resistance: people are moving in the same direction driven by shared values. A low sense of purpose makes it difficult for people to come to agreements and decisions. They are five times more likely to face obstacles from internal politics, five times more likely to be concerned about employees wasting time and three times more likely to suffer from lack of senior management sponsorship than organizations where there is a strong, shared sense of purpose.

Freedom to experiment helps people prioritize, make decisions, and rethink how they work. Freedom to experiment helps organizations prioritize. When people are not free to experiment or take initiative, it is difficult to consider different ways of working. Without experimentation, there is little basis for prioritizing and making decisions. These organizations are twice as likely to suffer from hesitation to rethink how we work and twice as likely to be held back by fears by management of losing control.

Distributed decision-making gives people at the edges of organizations a voice in digital transformation. Organizations with distributed decision-making rarely face resistance to rethinking how they work. In contrast, centralized decision-making puts control in the hands of people the least likely to be in touch with the reality of the edges — the front lines where people interact with customers. Removed from operational issues, they worry about losing control and fear that if given too much autonomy, employees will waste time. They’re also more comfortable talking about technology as opposed to the actual work processes technology enables. They are three times as likely to resist rethinking how they work. Organizations with highly centralized decision-making have the highest proportion of obstacles considered to be “serious and holding us back” and is the work culture with the most negative impact on digital transformation out of those studied in the survey.

Organizations that are responsive to the influence of the external world are more likely to understand the value digital can bring. Organizations that are open are more exposed to what is happening in the external world. They have a broader perspective helping them focus on their own priorities and be clear on ROI. Organizations that are closed to their external environment are twice as likely to report obstacles of competing priorities, slow decision making, hesitation to rethink how work is done, and an inability to make a compelling business case for digital.

If one of the obstacles described above is getting in the way of your company’s digital evolution, consider how the obstacle correlates with work cultures. Then find ways to transform your work culture using digital as a lever. Digital transformation is coming to us all, and understanding the relation with work cultures will help you optimize your change initiatives and actions.

You Don’t Need to Adopt Holacracy to Get Some of Its Benefits

When Alfred Sloan conceived the modern corporation at General Motors, he based it on hierarchical military organizations. Companies were split into divisions, each with their own leadership. Authority flowed downwards and your rank determined your responsibility.

Today, a few organizations – like Medium, David Allen Consultants, and Zappos – are adopting a radically different, approach to management: holacracy. Even as someone who has studied alternative management movements, I’ve been skeptical about holacracy, which eschews the standard “org chart” for a system of interlocking “circles.” To understand it better, I recently sat down with Brian Robertson, author of the new book Holacracy, to figure out how he’s gotten hundreds of firms to sign on.

For all of the sturm und drang surrounding the idea, as we talked I realized a lot of holacracy is just codifying many of the informal elements of good management. By getting beyond the particulars of adopting holacracy and taking a deeper look at the issues it addresses, we can see that problem isn’t that hierarchies have somehow become illegitimate, but that they are slow and the world has become fast. Instead of making the leap to an entirely new form of organization — a radical change not without its pitfalls — perhaps we should think more seriously about the problem of agility itself.

Even Brian admits that holacracy isn’t for everyone (I’m still not sure I would want to work in a company that adopted it), but I think every manager could benefit from a better understanding of the problems that it is trying to solve. So whether you are interested in making the jump to holacracy or not, here are four questions you and your company should be able to answer:

1. What’s your mission? While strategy is often seen as a cerebral, rational exercise, the truth is that to a great extent your mission drives your strategy. Management theorists have called a firm’s mission its strategic intent, because it serves as an organizing principle. A mission is why an enterprise exists, its purpose over and above delivering a bundle of products and services.

Southwest’s mission of being the low-cost airline drives everything it does, from the planes it buys to the routes it competes on. Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information, which helps it attract world-class engineers who share its mission. Tesla’s mission “to accelerate the advent of sustainable transport” transcends car manufacturing.

I’m always amazed at how few managers and front-line employees can articulate their company’s mission – and how few companies seem to have a differentiated mission. That’s a real problem. For all of the talk about “empowering employees” and “pushing decision making lower down in the organization,” without a shared sense of mission, none of that is possible without creating chaos.

By eschewing traditional hierarchy, holacracy helps bring the core mission of the enterprise to the fore. Instead of standard job descriptions listing qualification tasks and reporting responsibilities, it assigns roles, which spell out exactly what is supposed to be achieved and those roles are updated at regular governance meetings.

Clearly, holacracy is not the only way to clarify a mission, but the emphasis it puts on giving everyone in the organization a sense of purpose underlines how many enterprises lack a clear sense of direction. It’s something that we all need to pay more attention to.

2. How does work really get done? Most enterprises have rules, regulations, and procedures designed to promote a culture of predictability. Employees are supposed to get to work at a certain time, fill out timesheets and requisition orders in a certain way, and so on. This is supposed to support order and efficiency.

However, the real world rarely conforms to our expectations. Hopefully, in your organization, people have good enough sense to work around rules when they don’t apply.

Unfortunately, this often creates a destructive organizational dichotomy between how things are supposed to get done and how things actually get done. If these two diverge too much, then management loses legitimacy and trust. Once that happens, it becomes hard for people to believe in the mission of the enterprise, even if it is well stated.

Evan Williams, a cofounder of Twitter and Medium, writes that “one of the principles in Holacracy is to make the implicit explicit” and that is certainly important. However, you don’t need to turn your company upside down to do that. Frank and honest leadership is usually enough.

Make sure that you understand and support how work actually gets done in your organization, rather than some preconceived notion of how it “should” be done.

3. How would someone sell you a transformative idea? One of the greatest challenges of managing an enterprise today is that technology cycles often outpace planning cycles, so firms find themselves constantly having to adjust. Holacracy, inspired by Agile software development, is optimized for adaptation, making these types of adjustments as a matter of course.

One of the interesting things about firms that get disrupted is how often they were aware of the idea that upended their business, but didn’t see the potential. Wal-Mart and Sears. Netflix and Blockbuster. Google and Yahoo. In each case, the market leader had a chance to invest or partner with the upstart that eventually disrupted them.

Holacracy continuously adapts through a series of “governance meetings” that reallocate roles and responsibilities. However, that’s a significant investment in time and effort that many organizations may not want — or be able — to make. In industries with a large number of frontline employees, like retail, it probably isn’t practical.

One way to address the problem of adaptation is to ask yourself, if someone had an idea that could transform my company, how would they sell it? If Sam Walton came to you with a new retail concept, or Reed Hastings with a new way to rent videos, how would they get through the front door? Who would they talk to? How would they be received? What if the next great entrepreneur already works for you? Would she fare any better?

These days, every enterprise needs to develop a culture of change. What’s yours?

4. How do you balance cohesion and diversity? It’s become fashionable in management circles to talk about “breaking down silos” in order to improve how information flows around the enterprise. Yet we need silos, which are cohesive units that are optimized for specific tasks. What’s more, the reorganization efforts that are supposed to break down silos invariably recreate them in different places.

What’s really important is to balance cohesion and diversity. Without cohesion, there is no common purpose, but without diversity groupthink will set in and eventually that purpose will lose relevance. So you need a healthy amount of both in order to be able to both operate efficiently and adapt to new information in the marketplace.

A study of Broadway plays shows this in action. Researchers found that if no one in the cast or crew had worked together before, then results were poor. However, if there were too many existing relationships, then performance suffered as well. Traditional organizations often inspire far too much conformity — but I suspect holacracy and models like it will only exacerbate the problem because, ironically, its reliance on informal ties rather than dictates make conformity that much more insidious.. In hierarchical organizations — whatever their failings — leaders can change direction and combat groupthink. It’s not clear to me how that kind of change would happen in holacracy, which is driven by informal relationships to a much greater extent.

The jury is still out on holacracy, and I expect it will evolve over time just as traditional organizations have done. Every enterprise will have to choose its own path. What’s clear is that the status quo is untenable; we all need to ask ourselves some hard questions and continually come up with better answers.

What You Should (and Shouldn’t) Focus on Before a Job Interview

Years ago, when I was interviewing for the job of deputy editor at Harvard Business Review, I thought I had carefully prepared for my full day of interviews. I had my favorite suit dry cleaned and ready to go. I took my older daughter (a notoriously bad sleeper) to my parents’ house so I could count on getting a full night’s sleep. I even did a dry run of the unfamiliar drive to the office on the Sunday before my interview. I was ready for anything.

Or so I thought. The night before the interview, my younger daughter, normally a sound sleeper, started teething and cried continuously. Far from well-rested in the morning, I somehow managed to slice a hole in the suit when I tried to cut off the plastic dry cleaner wrap. With my second favorite suit on, I headed out the door with my driving directions in hand (this was pre-GPS!). Unfortunately, the map directed me on a heavily trafficked route — something I hadn’t encountered on my Sunday dry run. After sitting in bumper-to-bumper traffic, I ended up at the interview a solid half hour late — and seriously ruffled by my series of setbacks.

In hindsight, I can laugh at what happened (especially since I got the job) but I also realize that I had focused on all the wrong things: logistics and details instead of substance. That mistake could’ve easily derailed what was to be one of the most important job opportunities of my career.

Stress about job interviews feels like a given for most of us. And we often don’t make it easy on ourselves since we head into these critical moments with only a scant amount of preparation. “Even relatively smart people don’t prepare very well for interviews,” says John Lees, author of The Interview Expert: How to Get the Job You Want. Instead, we wing it. And that ends up making us nervous in the very moment that we’re most trying to impress. And as Lees points out, “nervousness is intimately related to underperforming.”

So, how do you manage the inevitable stress of a job interview and prepare correctly?

“Prepare yourself even more thoroughly than you think is necessary,” Lees advises. You may be perfectly qualified on paper, but presenting your best self in the interview room — someone who is energized and relaxed and easy to work with — is a rehearsed performance. Here’s how Lees advises you avoid the interview jitters:

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Managing Stress at Work

Managing Yourself Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Develop a real script. Most interview questions are utterly predictable, he says. You can probably sketch out the 10 or 12 things you will be asked. Why should we hire you? Why do you fit this role? I notice some gaps in your resume … and so on. Practice answers to those questions. Actually say the words out loud. It’s not good enough to think about how you’ll roughly answer. Lees calls that “false preparation.” Really do it. “It’s about building up small narratives,” Lees says, so that you have answers at the ready and you’re freed up to be far more present in the interview room. Plus you’ll probably give far more succinct and responsive answers. Remember that the interviewer needs to learn a certain amount about you in a short span of time. If you ramble on with one or two answers, you might use up all your time and you risk coming off as a self-absorbed bore.

Prepare for questions you want to avoid. If there’s something on your resume you’d rather not highlight, chances are your interviewer will be curious. You have a better chance of moving swiftly past the topic if you practice your answer ahead of time. “Keep it short and upbeat,” Lees advises. Let’s say you were laid off. You can say something like: “Like hundreds of other people, I lost my role when the company downsized. But that gave me a chance to look at the skills I’ve developed and identify new areas of growth.” Shift your answer from the past to the present and keep the conversation in a comfortable place.

If you are thrown for a loop by a question, take a minute to think about how you’ll answer before responding. Introverts, Lees points out, often need time to process a question. You can buy time by summarizing the question or framing it in your own way. “That’s a really great question. When I answer it, I’m going to discuss…” The worst thing you can do is look or act flustered. That communicates incompetence. If you have to, tell your interviewer: “Let me think about that for a minute…” and then only answer when you’re ready.

Make sure you’re actually listening. When people are nervous, they tend to focus on themselves, what they’re saying, how they’re responding. But anxiety can be a blocker that stops you from listening, or makes you miss something vital your interviewer just asked. Try to slow yourself down by taking slow breaths and focusing on the interviewer’s words, not your ruminations. If it’s a complicated question, it’s OK to repeat it and then ask, “Have I got this right?” before you start to answer.

Invent a conference call to give yourself a break. One of my former bosses once passed on an excellent tip. If you’re scheduled for back-to-back interviews, tell your contact in advance that you have a conference call you must attend and ask if there’s a private room for you to do that. That will allow you a small respite from the intensity of being “on” for several hours in a row. This trick is especially helpful for introverts but could help anyone who is likely to be exhausted from a long schedule of interviews (and who isn’t?).

Pre-script your own questions. You know you’re going to be asked if you have any questions for the interviewer. “No” is always the wrong answer. Have one or two good questions ready about the future of the company or the future of the role you are interviewing for.

Ask a trusted friend to mock interview you — and videotape it. If there’s anyone in your life with real world interview experience, ask them to practice with you. But both of you have to take it seriously. It’s a great dry run. Lees suggests videotaping the interview (your phone camera will likely do the trick) — and then watching it without the sound. Body language can be a critical component of your interview and “you’ll see how you present yourself,” he says. With practice, you have a chance to observe and correct your nonverbal messages before you’re in the hot seat.

Of course, being nervous is normal but don’t dismiss your jitters. Instead, be as ready as you can by doing the work of the interview well before you get into the room, says Lees. And he suggests you ignore anyone who tries to calm your nerves by telling you to “Just be yourself.” Of course you want be authentic, but you don’t want to present an anxious, sweaty-palmed version of yourself. You want to be the best version of you — calm, confident, and prepared.

August 27, 2015

A Simple Yet Powerful Way to Handle a Stress Episode

I’m sitting behind a long table, flanked by a marketing manager on my right and an entrepreneur on my left. We are an admission jury at an elite French business school. The candidate seated before us has spent the last two years toiling in a high-pressure preparatory school to get ready for this interview and the entrance exams that preceded it.

Right now, he’s falling apart. He can’t collect his thoughts. His answers to our questions are brief and incoherent. He is most likely unaware that he is continuously adjusting his glasses with visibly shaking hands. It’s painful to watch, and I want to give him a chance to reset.

“Take a minute and breathe,” I tell him. “You have plenty of time left.” He pants in distress.

“What’s happening right now?” I ask him. It’s a classic coaching question, designed to restore focus on the current moment. But he’s not fully present yet. Instead, he’s busy tightening his own noose. “I have no right to feel stressed. This is difficult, of course—but everyone else manages okay. I should be able to handle it.”

The candidate is experiencing what’s known as acute stress: it’s novel, unpredictable, and it represents a threat to a primary goal (in this case, admission to the business school, as well as the more general but no less vital goal of feeling good about oneself).

It is true that everyone encounters challenging conditions that can induce stress. But how well we continue to function has a great deal to do with how we assess the situation and how we respond. When we view the conditions as a challenge for which we have the resources needed to respond, stress can actually give us an edge in performance, as when a well-trained athlete gets butterflies in her stomach right before a competition. When we view the stressful conditions as a threat, something for which we are not equipped, our performance is likely to deteriorate. And if we don’t know how to catch the signs of a mounting stress response and take productive steps to counteract it, it can escalate, causing both our performance and well-being to suffer.

You and Your Team

Stress

Don’t let it get the better of you.

When we’re stressed, our bodies increase the production and release of the stress hormone cortisol. Research has linked elevated levels of stress and cortisol to impaired working memory—the capacity to store and manipulate information for short periods of time. Elevated stress levels can also impair the ability to retrieve memories. Thus, even though our candidate had spent many hours practicing for the interview, he wasn’t able to retrieve what he had learned during his practice. That’s because our ability to pay attention is compromised under stress. We may develop tunnel vision, overlooking vitally important pieces of information. Decision-making suffers as well; when stressed, we’re less likely to give full and systematic appraisal to all alternatives, and the quality of our decisions is more likely to be suboptimal.

Stress is thus like a vortex that can suck attention into it, consuming our cognitive resources—if we throw ourselves into the vortex, that is. One of the keys to staying grounded is whether we are able to connect to our inner resources in the presence of stress—or whether we lose the ability to access them. Interpreting stress as a sign of weakness, as the candidate did—and as many of us do in our daily lives—is dysfunctional. Instead of helping us to respond effectively, the negative self-evaluation we heap on top of the stressful circumstances increases anxiety, erodes self-confidence, and undermines our ability to direct our attention to productive problem-solving. Stress can cause us to lose perspective. It also breeds isolation and a sense that we are alone in our suffering, which only makes the stress worse.

Recognizing what’s happening in the body is the first step to shifting what’s happening in the mind. Any one of the classic physiological stress responses, such as breathing hard or feeling one’s heart race without physical exertion, perspiring more than usual, feeling one’s mouth go dry, clenching one’s jaw, noticing tension, numbness or tingling in the muscles, hunching or cringing, provides us with an opportunity to forestall the escalation of stress. Instead of trying to ignore these symptoms, the counterintuitive yet highly effective approach is to pay attention to them.

The acronym RAIN, a tool used by many meditation teachers—originally developed by Michele McDonald—is a simple yet powerful way to handle a stress episode. It allows us to shift our perspective of the stressor from threat to manageable challenge, and to activate our own resources to meet the challenge with equanimity:

Recognition: Consciously take notice of what is occurring in your body and mind. For example, “My mouth feels dry and there is a pit in my stomach. I feel like an idiot.”

Acceptance: Acknowledge that the stress response is present and allow it to be here. This doesn’t mean that you’re happy about it, but giving up the effort to resist it is, paradoxically, the quickest way to help it subside.

Investigation: Ask yourself calmly what thoughts and emotions are present, what stories you are telling yourself. Following this technique, the candidate might have answered, “I can’t believe I sound so lame. I’m afraid that I will lose this opportunity, that I will not be admitted to business school, that I will feel like a failure in front of my family and friends, and that I won’t have a successful career.”

Non-identification: Having recognized, accepted, and explored the implications of your stress symptoms, the final step is to realize that although you are experiencing them, they do not define you. “I am having the thought that I may feel like a failure” is very different from and much more manageable than “I am a failure.”

Using this tool helps you to regain your strength and sense of control, and to proceed in a calm, rational manner. RAIN harnesses the power of self-compassion to shift our perspective and reconnect to our inner resources, thereby reducing the potential negative effect of stressful conditions on our performance and well-being.

Just as stress is not a sign of weakness, neither is self-compassion. Self-compassion is not a way to avoid facing up to one’s challenges or limitations. Quite to the contrary, it is a force for facing those things head on and moving through and past them. Self-compassion enables us to look straight at the most daunting challenges we face in our lives without activating the stress response that can disable our ability to deal with them effectively.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers