Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1253

September 8, 2015

Help Your Team Agree on How They’ll Collaborate

It’s easy to assume that everyone knows how to work on a team — and on some level this is true. But each member of your team probably has her own understanding of how to collaborate, not to mention individual styles and preferences. If you ask six team members what they think “completing work on time” entails, you’ll probably get six different answers. The same holds true for your team’s other aspirations. It’s tempting to get going on the task work of a project, skimping on the people aspects of team work. But agreeing on clear rules of conduct allows you to blend individual team members into one cohesive unit.

We each have our own rules of conduct, of course. Yours may tell you that getting to a 9:00 a.m. meeting at 9:03 is just fine. Or that it’s OK to chime in mid-presentation when you’re enthusiastic about an idea. Or that you should remain silent to avoid rocking the boat when you disagree with a decision the majority of people seem to support.

So what happens when you work with someone who thinks that a 9:00 start time really means 8:55? And that interrupting is rude? And that silence signals agreement? One or both of you end up frustrated, angry, or feeling disrespected, and tensions will mount.

Most of us want to do a good job and work well together. But when individuals’ rules of conduct are unspoken, motives are often misinterpreted (“He’s just doing that because he always has to be right” or “She’s trying to hog the spotlight”).

Rules of conduct clarify how you’ll make decisions, keep everyone informed, run meetings, hold one another accountable, assess progress, and continually improve. The purpose of discussing your team’s rules isn’t to determine the one right way of running a team. It’s to agree on the one consistent way you’ll run this particular team.

Rules of conduct:

Clarify what others expect of you, the leader.

Make members’ behavior more predictable.

Rein in members’ behavior so you won’t have to play “cop” as often.

Reduce the amount of time you spend rehashing processes, such as how team decisions are made.

Provide criteria for objective feedback and conflict resolution.

Rules of conduct will form and evolve whether you talk about them or not. Without deliberate conversations, you’ll find that unproductive rules crop up as people mimic what you and other influential team members do in practice. If you, the leader, routinely show up five minutes late for meetings, lateness becomes the norm, overriding any notion that punctuality is important. Rules also evolve according to what you reward. By listening to a team member complain about another member, you reward that behavior—you’re giving the complainer your attention. And that kind of exchange becomes an accepted way of operating, even if the team originally agreed that members should try to resolve conflicts without your intervention.

Reconciling personality and style differences isn’t the only reason to create rules of conduct (though it’s a big one). If you’re leading a cross-unit team, you’ll need to blend the different approaches. If you’ve added new people to a team, you’ll have to take their perspectives into account. If you’re managing two teams that must collaborate to achieve larger goals, you’ll have to establish a third, overarching set of rules. You get the picture: Any time you bring people together, you have to create explicit rules of conduct—or the work will suffer.

Here are a couple of exercises to help your team establish its rules.

Begin with a Boilerplate List

Rather than having open-ended discussions about desired conduct—which can take a lot of time and exhaust everyone—find and use an existing framework (a quick Google search yields several and one is included in the HBR Guide to Leading Teams). Ideally it lists basic rules for respect and trust; meeting discussions and decision making; dissent and innovation; feedback and reporting; and conflict resolution.

A framework like this serves as a starting point for establishing your team’s top 10 rules (a manageable number to generate and remember). You can then reach agreement on them through what’s called the nominal method of decision making:

Ask individuals to do their own assessments: Which rules has the team followed from the get-go? Which would they like to add? Which would they rate as their top 10?

At a meeting, post everyone’s lists on the wall.

Have team members walk around, view everyone’s lists, and put checks next to the 10 rules they value the most (with fresh ideas in the room, their picks are likely to differ from their original 10).

The rules with the most votes become the team’s top 10.

This exercise works well for new and existing teams. At a large technology retailer, a team of eight Service Center staffers had worked together for several years, but they had never held team-building conversations. As a result, some counterproductive rules of conduct had emerged: For instance, team members weren’t following up on customer requests. As more and more of those requests went unaddressed, people started pointing fingers. The team decided it was time to create explicit rules of conduct; members consulted some sample ones they found online and then worked together to come up with the following list:

Bring up problems (regarding tasks or relationships) when they arise. Don’t expect them to go away; instead, name the elephant in the room.

Take ownership and follow through on problems.

Don’t let things fall through the cracks. Even if the next step is someone else’s responsibility, stay in touch until it’s done.

Tell people what you need. Don’t expect them to guess.

When responding to someone’s request, always explain why you are doing what you are doing, especially when you have to say no.

When asking for something, always explain why you are making the request. This allows the person to come up with an alternative solution if what you are asking for isn’t possible.

If you need training or tools in order to be successful, ask for them.

Take risks, but inform key people so that they don’t get blindsided. Analyze the risks, identify the unexpected consequences, and plan for them.

Think Center-wide. When your actions diverge from usual practice, always ask, “What impact will this have on the team?”

Start each meeting with individuals sharing “what I did this week that constituted excellent customer service.”

To make these rules stick, the team regularly reviewed them, especially when they experienced backsliding. And when the Service Center added three employees, veteran staffers used orientation as an opportunity to reexamine the rules. They invited the new hires to propose different rules or suggest changes to existing ones.

Even if the makeup of your team doesn’t change, members should periodically reassess its rules. Do this quarterly or each time you close out a project. That keeps the rules relevant as tasks and timelines change. It also helps quash undesirable behaviors that emerge, as the Service Center staffers discovered.

Conduct a Cultural Audit

A cultural audit helps newly blended or ongoing teams with new members identify rules of conduct that already exist—whether explicitly established or unofficially evolved. The team can then decide what to keep, modify, discontinue, or add.

A few days before you meet, ask people to think about how they would describe to a new member “the way things are done around here.” Use the following questions as prompts:

What rules were you told explicitly when you joined the team? Did someone take you aside and give you the “inside story”? If so, what did that person say?

What rules do you wish you’d been told about early on?

Has a teammate ever told you, “That’s not how it’s done around here”? (Violating an unknown rule is often the quickest way to learn!)

What criticisms have you heard about others’ behavior? Name the criticisms but not the people involved.

As the leader, conduct your own audit of the culture. Don’t spend too long on it: Your spontaneous responses are probably the most accurate. When the team meets, ask members to share their perceptions. Take time to highlight differences—they’re often a source of conflict (or at least confusion). As in the boilerplate list exercise, ask members to vote for the top 10 rules they’d like to see the team adopt.

Excerpted from

HBR Guide to Leading Teams Ebook + Tools

Leadership & Managing People Book

Mary L. Shapiro

39.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

A team I consulted with at a large health care company used the Cultural Audit to identify and resolve a culture clash. The leader, a VP of marketing, had brought together some internal folks and a group of contractors to create a social media campaign. But the two camps had problems gelling. The internal folks complained that the consultants were too lax about details and deadlines, and too informal. Not surprisingly, the contractors saw the company insiders as bureaucratic and stodgy. When each group fell back on its own home rules, conflicts arose. The Cultural Audit gave the team a nonjudgmental way of recognizing the two sets of rules, which took the heat out of the conversation. Members then negotiated one common set of rules to guide interactions within the blended team.

Rules of conduct should help your team work together smoothly and productively, so keep things simple and practical. Focus on behaviors that will improve collaboration and the quality of the work. Early on, though, it’s usually best to err on the side of more structure (and a few more rules), which you can adjust or relax as the team hits its stride. For instance, you might start out with a rule about answering e-mails by the end of the day. As that behavior becomes ingrained, you may no longer need that rule to ensure responsiveness. When teams don’t have clear, specific rules at the outset, they often have to impose structure later as confusion and conflict arise, which takes more time and energy than spelling out desired behaviors in the first place.

This article is adapted from the Harvard Business Review Press Book HBR Guide to Leading Teams Ebook + Tools.

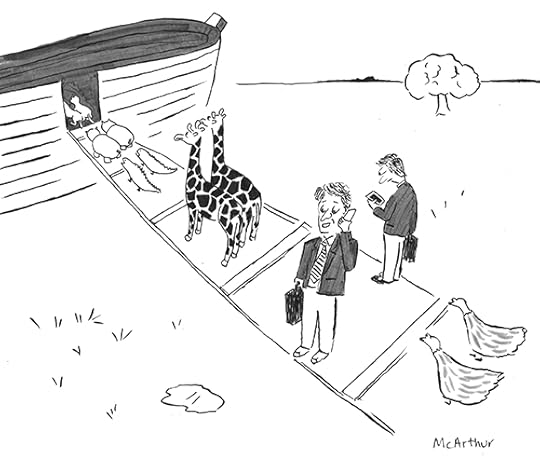

Strategic Humor: Cartoons from the October 2015 Issue

Enjoy these cartoons from the October issue of HBR, and test your management wit in the HBR Caption Contest. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

“Let me show you the slide deck I used to woo your mother.”

Jacob Samuel

“But if we keep up with technology, our employees might develop skills that will allow them to leave.”

Mike Shapiro

“I know what you’re thinking. Bonus points for spelling ‘incarcerated’ correctly nine times on a résumé.”

John Caldwell

And congratulations to our October caption contest winner, Jevb Enano Bote of Makati City, Philippines. Here’s the winning caption:

“They brought me here to talk about diversification, but they already have two of everything!”

Cartoonist: Damon McArthur

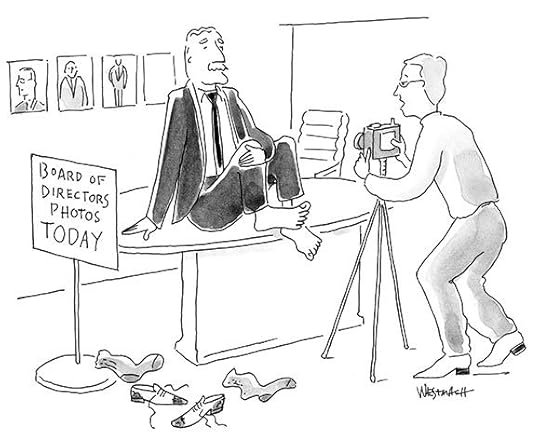

NEW CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your caption for this cartoon in the comments below—you could be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free book. To be considered for this month’s contest, please submit your caption by September 30.

Cartoonists: Elizabeth Westley and Steven Mach

Making Better Decisions in Your Family Business

The decisions facing business families can be gut wrenching – and the implications of these decisions can be huge both for the future of the family and also of the business: “Who should the next CEO be – my daughter or my son?” “Should we buy our cousin out of the business?” “Can non-family directors be trusted to make key decisions for our business?”

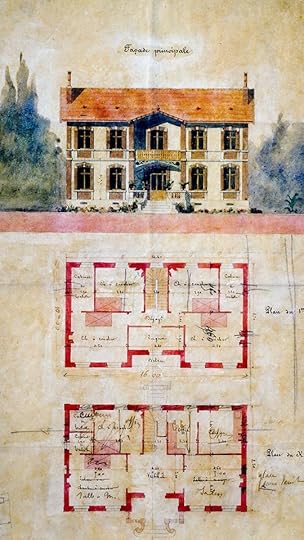

To help our clients, we use a simple analogy for how and where strong family businesses make decisions. Just as we separate the bedroom from the kitchen in our homes, successful family businesses build out and furnish four rooms: the owner room, the board room, the management room, and the family room.

Discrete decisions are made in each room: management directs operations; the board monitors the performance of the business and hires/fires the CEO; owners set the high-level ownership goals for the business and elect the board; and families build unity and develop family talent – to name just a few of the most basic decisions made in each room.

Well-run family business systems funnel decisions to the appropriate room, and family members and others play different roles and behave differently in each room.

The source of decision-making power also varies across the rooms. In the owner room, power is based on who controls the shares, either directly or through trusts. In the board room, directors influence one another in a peer-to-peer setting. CEOs run organizations that are hierarchical and generally make decisions based on financial returns. Families usually operate by consensus and make decisions based on their impact on legacy and stewardship.

The four-room model helps set decision boundaries. A non-family CEO, for example, stays in the management room and doesn’t tell the scion of the business family where to go to college. Similarly, executives make many daily decisions on how to implement the business strategy but do not decide the dividend policy. That’s up to the owners. For their part, family members can’t just walk into any room; there has to be a process for channeling family wants and needs to the appropriate rooms.

The four rooms are not randomly configured; there’s a clear hierarchy. Management answers to a board that ultimately answers to the owner group. The family room is not perched atop of the other rooms, as the other rooms don’t report to the family. Rather, the family room runs adjacent to them to symbolize family unity, which is so important for maintaining decisiveness across the full family enterprise and for developing the talent of family members who, if qualified, can move into other rooms. The family room is also important in that it provides a forum for addressing the family conflicts and stresses that can spill into the other rooms.

In our work using the four-room model, we have found that family businesses face three reoccurring, fundamental challenges in decision-making. Let’s take a look at each of these in turn.

One-Room Houses

Family A* lived in one room. They conducted business around the lunch table. The nine siblings, who equally owned the business and served in key leadership roles, ate together every day. The executive dining room became the de facto board room, owner room, management room, and family room. At one sitting, it was typical of the siblings to go from talking about the minutiae of daily business (setting prices at the retail stores that the family owned), to how the siblings should invest their multi-million dollars of jointly owned liquid assets, to where to spend their Christmas vacations.

These were genial discussions that rarely led to decision-making – one of the greatest challenges (and dangers) facing any family business. The conversations tended to go round and round despite the need to take action on a business portfolio that was on the decline. What was going on? First, the informal setting fostered wonderful dialogue, but rarely led to actual decisions. Even when actions were agreed on, there was little follow-up to see whether they had been implemented. More importantly, decision-making defaulted towards consensus based on the equality of their ownership, despite some having greater expertise in certain areas than other siblings did.

Many family businesses have this very informal way of exchanging information; they are often unaware that structure can dramatically improve the quality and effectiveness of their decisions. The lack of awareness is typically historical. A one-room family business is like a massive loft in which a bachelor might live – a converted warehouse that combines the den, bathroom, bedroom, and kitchen into a single space. Were he to marry and have children, our bachelor would need a larger house with walls dividing the rooms; there would have to be a separate kitchen, dining room, living room, and bedroom. So, too, as the family business grows from a founder-owned and operated entity to a larger family system, it must evolve towards a more sophisticated structure.

We helped Family A to see the need for structure, and they separated their family business system into the four rooms. We worked with them to create Executive Committees for their core businesses, each reporting to a separate board. An Owner Council was established to make decisions about how to allocate capital across their businesses, and a Family Council to prepare some of the 30 members of the next generation to step into leadership and management roles one day, if suitable. The nine siblings no longer occupied every room together, and people were brought in from the outside — in particular, into the management and the board rooms — to make the decision-making process more effective.

Although it took the siblings time to adapt to the structure of the four rooms, doing so has allowed them to make some tough choices about their business, as well as to find the mix of roles that best suits their talents and interests. They still eat lunch together every day, and clearly enjoy one another’s company, but now they come together primarily to catch up on their nephews and nieces, to plan vacations, and to stay connected as siblings.

Missing Rooms

Family B was in many ways a showcase family business. They had world-class family governance led by a textbook family council; in fact, we have never seen a finer one. They had a rock-star board room, with a mixture of family and non-family members. The directors met regularly and effectively oversaw the business, which was well functioning and profitable. Dividends were strong, even as the business was growing.

But there was one overarching problem – the owner room was missing. The owners had by choice given their proxy to the directors. They held shareholder meetings once a year as required by law, but these were perfunctory. The proxy effectively allowed the board to elect itself.

Eventually there was a majority of outside members on the board, and the influence of family owners began to wane. The family council was outstanding at organizing annual family meetings and developing the next generation, but they could not provide a cohesive perspective on key owner issues and decisions.

In its role overseeing management, the board kept asking: “What do the owners want?” “Do they want to grow the business?” “Do they want liquidity?” Without an owner room, the board had no way to have this conversation directly with the owners. In the absence of this perspective, the board members charted the course that they thought made the most sense. It took several years for the family owners to realize that the path they were on was not the one that they wanted, but they lacked the venue to act on that concern.

Having a family business with no owner room is like owning a mansion without a kitchen: no matter how beautiful the estate may be, the home is not functional. Yet in our experience, the owner room is the room that is most frequently missing in a family-owned business, at least in the US.

In part, the explanation lies in the fact that US business schools have lots to teach executives about best practices for boards and management in publicly-traded companies, lessons that can be transferred to family-owned businesses. But private ownership is generally ignored in academe – and in practice. Advisors who dedicate themselves exclusively to family firms have focused on the family part of the family business system for the last 30 years.

While good family business governance is necessary, it is not sufficient.

If there is no owner room, the family’s connection with the business gets lost. When owners become passive over time, they lose control of the business to the proxy who makes their decisions for them. On the other hand, we know of quite a few prominent European families that have owner rooms but no family rooms. In these cases, money becomes the overriding concern. Voting rights determine how decisions are made — even when family members are discussing the budget for the next family gathering.

That was not the problem for Family B, who needed to create a functioning owner room. To do so, the family first had to do something that felt uncomfortable. They had to establish a venue where family members were not all equal, where owners would participate, but spouses and in-laws would not – i.e., an Owner Council. The owners then augmented their knowledge of the business before electing representatives who would be authorized by the full owner group to define their vision for the business and actively select the board. It took time, but today the family has recovered control over their business, with the owners now serving the critical function that had been missing.

Messy Rooms

Family C had a board room where an under-performing non-family CEO/chairman dominated a set of fairly disengaged and inexperienced family board members. When the board met, the CEO/chairman ran the show, sharing what information he chose as relevant. Questions from the family directors were addressed with a confusing level of detail that they couldn’t understand. The owners said that they felt “stupid” during board meetings.

While the company was clearly under-performing its peer set, the CEO/chairman ensured that he had a non-performance based, very lucrative compensation package. The owners, on the other hand, were told that dividends were unlikely for at least a couple of years. Clearly, the right people were not in the board room.

Getting the right people in the board room, however, is no easy task. It often provokes anxiety to bring independent directors into a closely-held private business. Unless they are just rubber-stamping the decisions of majority holders, independent directors wield a lot of power. They learn the secrets of the business and are, indeed, outsiders. The level of trust required to share information with outsiders is extremely high. But when it works well, a good board serves as a buffer and a bridge between the owners and the business. As a colleague puts it: “The board is the arbitrator of fairness.” Indeed, by solving problems in as unbiased a way as possible, a highly effective board can help stabilize the family business across generations.

Cleaning up a board room usually involves balancing the number of directors who are owners with outside, independent directors. Over time these board rooms often shift to a majority of independent directors, but this transition typically takes many years. Best practice is for non-owning executives, other than the CEO, to be excluded from the board, while family members are restricted to those who are deeply knowledgeable of, and committed to, the business, rather than to those who are there to “protect” their ownership stake.

With this in mind, we helped Family C do two things: elect a set of strong, independent members to its board and move some discussions and decisions from the board room into the owner room, where the family owners could discuss their concerns and make ownership decisions outside the direct influence of the CEO/Chairman. (We also recommended an outside director be named Chairman, but the CEO’s contract prohibited that action. Some messes stay messy – or are postponed for later.)

The four-room analogy is a simple but dynamic way of rethinking decision-making in family businesses that can be transformative. As a CEO client summed up the transition to the four rooms: “I’ve become 50% more efficient. When my second brother, who no longer works in the business, comes into my office now and complains about some executive decision that I’ve made, I say, ‘Jack, are you talking to me as an owner? This issue is not in your bailiwick. This is the management room.’ Now I have one conversation at a time – and sometimes more conversations than I ever thought were necessary – and I am making a lot more progress.”

This is the eureka moment that is the reoccurring theme in our work.

*Some of the identifying details in this article have been changed to protect confidentiality.

Manage Stress by Knowing What You Value

Much has been written about “stress management” techniques that are primarily behavioral in nature — such as getting adequate sleep, regular exercise, and mental downtime; taking vacation; doing controlled breathing; practicing yoga or mindfulness meditation; or getting acupuncture treatments. But relatively little has been written recently on the benefits of self-disciplined articulation of a philosophical worldview and core values that help us weather the storms and devastations that inevitably rock our lives and careers.

The value of self-reflection and self-awareness is well known in both Eastern and Western philosophical traditions. The exhortation from Socrates to “Know Thyself” reverberates across the history of philosophy, as a reminder to reflect on our life’s mission and the strategies we use to attain it. Confucius similarly urged the individual to engage in self-disciplined reflection upon one’s values, followed by action steps to implement those values in interpersonal settings. Management of complexity and stress in the Socratic and Confucian traditions depends heavily upon self-awareness, an ethical value system, and a capacity to act on core values (such as kindness and humility) in social relations.

While this ancient wisdom hardly requires validation from empirical science, contemporary cognitive psychology and neuroscience research interestingly reveal how self-reflection manifests itself in our brains and behaviors. Recent neuroimaging research shows that self-reflection lights up the brain’s anterior and posterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which is linked to regions that mediate emotion and decision-making. Cognitive psychology research shows that one of the most effective methods for reducing stress is to engage in self-reflection directed toward appraising it as a challenge rather than a threat.

You and Your Team

Stress

Don’t let it get the better of you.

In overwhelming and frightening moments, stress can be prevented or managed by self-disciplined contemplation of core values and goals. Religious individuals consider this a turn toward God, while secular individuals may think of it as a turn toward their “highest good.” In all cases, they work diligently toward self-awareness and they maintain a steadfast focus on honorable goals and ethical principles – even as stressful uncertainties, risks, threats, and instability swirl about them. When confronted by frightening situations such as a job loss and financial setback, they carefully appraise their core strengths and resources, rather than panicking or disconnecting from reality. They humbly seek and accept help from others, maintain an open mind about next steps, and develop rational action plans to care for those who rely on them.

Many executive coaching clients use this approach successfully. In my own coaching practice, I ask clients open-ended questions about their philosophy of the “good life,” or what the ancient Greeks called eudaimonia. The conversations that ensue help clients to define the fundamental values and goals that underlie their careers and personal life decisions. These conversations can be deepened by the completion of style assessments that focus specifically on human motivators, such as the Individual Directions Inventory (IDI). The IDI is a well-validated and useful tool for assessing personal preferences and values, such as social affiliation and irreproachability.

Attaining clarity on core values and a philosophical worldview, helps individuals develop steadiness in the face of stressful events. They embody what Stoic philosophers, such as Marcus Aurelius, championed centuries ago: use of contemplative self-reflection and development of virtuous character traits to withstand stress and uncertainty. They become leaders who show others how to embrace eternal values regardless of current circumstances.

I encourage coaching clients to develop an effective and sustainable method for engaging in philosophical self-reflection, such as daily journaling or thinking regularly on these questions during an already scheduled, convenient, mundane activity (such as while brushing their teeth). Their self-reflection helps them to identify and reinforce their self-chosen core principles — such as being kind, gentle, humble, respectful, and generous. Later on, they can intentionally draw upon their self-reflective stance when striving to avert a crisis or manage a stressful life event.

My client Melanie is an example. She came to me after years of maneuvering to be promoted to a C-suite role didn’t pan out, and after having an affair with a man she met on a business trip. She felt burned out, unproductive at work, and irritable with colleagues. Our conversations led her to realize that much of her stress was related to her infidelity — both to her husband and to her current job role. Melanie came to see that she valued her current job and had taken it for granted, believing a promotion would improve her life.

After deepening her self-reflection about her fundamental values, she decided to make fidelity to her self-chosen life roles as a VP and a wife her top priority. She adopted the motto of the U.S. Marines — semper fidelis (always faithful). This steadfast decision about how to conduct her life going forward resulted directly from thoughtful self-reflection on the values and principles that were the underpinning of her entire life structure.

Everyone can benefit from this kind of disciplined and sustained self-reflection — both as a good thing in itself and as a powerful stress management tool. Nowhere is this more true than in stressful business situations, where it can be incredibly challenging to pause and reflect on essential values. So we ought to make a special effort to incorporate philosophical self-reflection as a meaningful, yet convenient, part of our ordinary routine.

Why More and More Companies Are Ditching Performance Ratings

A few years ago, I noticed around half a dozen courageous companies beginning experiments to remove ratings from their performance management systems. Companies such as Juniper and Adobe stopped giving people a one-to-five rating or evaluating employees on a “performance curve,” also known as the “forced ranking” approach. They were still differentiating performance in various ways, and still using a pay-for-performance approach, just not through a simple rating system.

By early 2015, around 30 large companies, representing over 1.5 million employees, were following a similar path. No longer defining performance by a single number, these companies were emphasizing ongoing, quality conversations between managers and their teams.

At the NeuroLeadership Institute, we’ve been studying this trend closely since 2011. Our interest in the topic was piqued when clients started to tell us how our research on motivation and the brain was explaining why standard performance reviews were failing. In short, we found that social threats and rewards, like one’s sense of status or fairness, activate intense reaction networks in the brain. This explained the intense reactions people had to being assessed on a ratings scale, and it also pointed to ways of designing better systems.

The idea of removing ratings drives many HR executives a little crazy because companies love to quantify and analyze almost everything. The thought of getting rid of a metric is almost heretical. Executives who contacted us after reading our research often assumed that removing ratings was an anomaly, perhaps driven by smaller companies who don’t realize how important pay-for-performance is.

Yet in mid-2015, the trend started to accelerate. Consulting firms Deloitte and Accenture, global health services client Cigna, and even GE—the company who popularized the idea of forcing people into a performance curve—all announced changes to their performance management systems. By September 2015, 51 large firms were moving to a no-ratings systems. According to research firm Bersin by Deloitte, around 70% of companies are now reconsidering their performance management strategy.

This November, coinciding with our annual Summit, we will publish a full set of findings from closely studying 30 companies that have made this change. But we’ve already seen four, clear reasons the trend is gaining momentum:

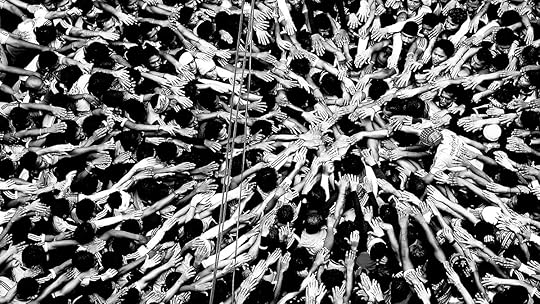

The changing nature of work. Numerical performance management systems don’t take into account how work gets done today. Who sets 12-month goals anymore? Some workers need goal cycles of one month, or even one week. Work is also happening in teams more than ever, and many people are involved in multiple teams that often are spread around the world. Few managers accurately know their team members’ performance when that employee is involved in many other teams, often doing work the manager doesn’t see or even understand. In short, standard performance reviews, delivered once a year, are just not relevant to the ways we work anymore.

The need for better collaboration. Studying companies that have made the change, we are seeing a clear trend: conventional ratings systems inhibit collaboration, making a business less customer-focused and agile. Top ratings lead to high status, promotions, and raises—yet it’s not like at school, where everyone can get an A if they work hard enough. With a forced curve, a manager with a hardworking team of 10 people may only be allowed to give one or two of them the top rating. As a result, people directly compete with each other for rewards, hurting collaboration. As our forthcoming research will show, when Microsoft removed its ratings, employee collaboration skyrocketed.

The need to attract and keep talent. Companies also remove ratings to get managers to talk to employees about their development more than once or twice a year. Millennials in particular crave learning and career growth. Of the 30 companies we studied, one preliminary finding that jumped out was that after a company removed ratings, managers talked to their teams significantly more often about performance (three or four times a year instead of only once). More frequent communication helps with employee engagement, development, and fairer pay, as managers better understand how their people are doing.

The need to develop people faster. By removing ratings, early indications of our research are that companies appear to be developing people faster across the board. It’s happening because of more frequent dialogues, which also tend to be more honest and open when neither party has to worry about justifying a rating at the end of the year.

When Deloitte analyzed their process, they found employees and managers spent around two million hours a year on performance reviews. The problem was that much of this time was spent talking about the ratings themselves. Companies that remove ratings are seeing the conversations shift from justifying past performance to thinking about growth and development. The result is better employee development, which seems to be a win for everyone.

Companies who have replaced ratings tend to be anxious about it beforehand and enthusiastic about it afterward. Their employees are happier, which encourages more engagement and better performance. It should be no surprise that treating an employee like a human being and not a number is a better approach. Yet it has taken a few bold companies to lead the way and show us that life is better on the other side. Only time will tell how lasting the trend truly is, but I strongly suspect we are at the beginning of something big.

September 7, 2015

3 Ways to Encourage Smarter Teamwork

Business problems today are too big for any one person to solve. Agile teams are much more effective at solving problems than are lone geniuses. So why do we still reward the smartest people in the room more so than those who excel at working with others? You know who I’m talking about: the people who brazenly take over meetings by showing off how much they know or how witty they can be at the expense of any other voice in the room—and who often end up getting all of the boss’s attention.

Perhaps it used to make sense to defer to “the smartest person in the room” because, in conventional organizational hierarchies, they are the ones who became the leaders charged with issuing the orders. But in today’s more open world, where the best work is done by teams and communities, we need to rethink which skills have become the most valuable.

I’m not arguing that intelligence isn’t a crucial skill. Rather, when we overvalue an individual’s abilities to the detriment of the team, we’re likely putting our organization at a disadvantage. It’s not an individual’s IQ that separates our best people from the rest; it’s their ability to work well as part of a team, that we should be celebrating.

At Red Hat, we’ve found that there are a set of skills you can prioritize, train, and even reward as a way to build the kind of smart teamwork that’s going to give you a competitive edge.

1. Active listening. How often have you found yourself in a conversation with someone, only to find yourself having to repeat the same information to that same person all over again? Great teams, however, are made up of great listeners.

This is a lesson I learned from Delta Air Lines’ former CEO, Jerry Grinstein. I remember a time when we were meeting with a group of financial advisers and Jerry, as usual, was taking copious notes. I didn’t think anything about it, because he often took lots of notes. But after the meeting, one of the senior advisers described how rare it was for a senior executive to “admit they don’t know everything” by taking notes. It made a clear impression on the adviser.

That’s why now, at just about every meeting I attend, I bring a notebook along and take notes to send that same message to who might be talking. Plus, I’ve found that when you take notes, you can more easily follow up with the person letting them know what you heard and what follow up questions you might have. When team members start actively listening to each other, everyone becomes smarter.

2. Giving and receiving honest feedback. Teamwork requires communication—a lot of it. It needs to be frequent and constant. It’s not enough to wait until the end of the year, for example, to share feedback on someone’s performance. There needs to be a continuous flow of information between the members of a team—and most of it needs to be positive. Your associates should be encouraged to say “Great job!” and “Thank you!” to each other far more than they should share criticism.

At the same time, individuals need to be willing to confront the hard truths about their own performance without becoming defensive. Team members need to embrace the concept of “you aren’t your code,” which means you must be willing to accept a critique of your work without thinking someone is criticizing you personally. The idea is that you want to build a sense of accountability among a team’s members where people watch each other’s backs—not look to stick a knife in them.

3. Valuing team contributions, not ego stroking. We all want to be seen as smart and capable, especially in the workplace. But it’s by making contributions to the team or community that actually earns you influence and trust—not your ability to show off how smart you are. Great team members have a willingness to admit they don’t have all the answers. Rather, they seek to talk through problems and think on their feet in order to reach the best conclusions with the help of their team rather than shoulder the burden of coming up with all of the answers on their own. Rather than seek personal awards and achievements above all else, great team members value their contributions to the group’s accomplishments instead. And by doing so, open themselves up to opportunities.

I’ve seen it first hand at Red Hat. The individuals that are team players are often called to participate on more cross-functional team projects, allowing them to enjoy broader opportunities and experiences across the organization.

When you can recruit, train, and retain team members that display skills like these, you’ll wind up with better decisions, better engagement, better execution, and ultimately better results. How smart is that?

Games Can Make You a Better Strategist

Play has long infused the language of business: we talk of players, moves, end games, play books and so on. And now we hear often about the “gamification” of work—using elements of competition, feedback and point scoring to better engage employees and even track performance. Even so, actual games are still taboo in most organizations—the stereotype of the work-avoiding employee cracking new high scores in Minesweeper has given gaming a bad name. And the corporate executive playing games to improve his or her strategy-making skills is still rare. This is unfortunate. We think that games have an important place in cultivating good strategists, and that now more than ever games can give executives an edge over their competition.

First, there has never been a greater need for companies to learn new ways of doing things in response to a complex and dynamic business environment. And second, the sophistication and effectiveness of strategy games at our disposal has risen tremendously. In the past two decades, strategy games have evolved from dull monochrome dialogs to well-designed AI-based apps.

We think that the next generation strategy apps will finally be able to prove a real business case. Just consider some the advantages games have over more traditional approaches in strategy education. Books are great to foster intellectual understanding but are not interactive and do not reflect the reality of busy schedules and declining attention spans. Live pilots are highly realistic but costly, time consuming and risky. And coaching or mentoring approaches have great merits for personal development, but are hard to scale.

Games on the other hand can create an experiential, interactive and tailored understanding of strategy at low cost and in a scalable manner. They allow managers to suspend normal rules in an acceptable way and they provide an effective audiovisual medium for absorbing ideas.

In our work with executives and strategy games, we see five distinct benefits of using games for enhancing strategy formulation and execution skills:

1. Games provide inexpensive, real-time feedback. With instant feedback, explicitly expressed in scores or implicitly via a competitor’s behavior, executives can learn much more quickly than in the real world.

In addition, unlike in reality, failing in games has no costly downside. Games are testing grounds for strategies. They’re “sandboxes” where erroneous behaviors can be undone and different decision paths tried out. Execute a flawed strategy in the real world and your organization might falter; applying it in the gaming realm, and a lesson is learned at the cost of only a little frustration.

Well-produced strategy games can model environments tailored to a company’s circumstances and targeted skills. Based on the user’s actions, a game can quickly adapt to the learner’s individual skill level and learning curve — clear advantages vis-à-vis books, articles, or seminars. A smart game keeps the manager in what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls the “flow” zone, an optimal corridor between challenge and skill, by building a series of rounds of increasing difficulty. The learning curve of a game can thus be tailored to the individual player, without overwhelming them as reality often does.

People Express, for example, is a business simulator that provides players with a rich inside perspective on starting and managing an airline. In each simulated time period, the player makes strategic decisions and receives feedback from past decisions—on how fast to grow, how to set prices, or how aggressively to advertise. Hiring policies influence morale, productivity and turnover, marketing efforts shape demand growth, and competitors fight back. Strategists learn to manage and steer complex systems—without the costly risk of bankruptcy. “Deep actionable knowledge and decision-making skills develop when people have the chance to apply classroom theory in the real world, with its messy complexity, time pressures, and irreversible consequences,” notes John Sterman, a professor at MIT who uses this game to educate business students and executives (we spoke with him recently about how games enhance strategy).

2. Games allow managers to deeply engage with ideas by incorporating interactivity. Games require managers to analyze the environment, make judgment calls, execute decisions, and reflect on the consequences. Stimulating aural and visual senses, games provide a much more immersive experience than written text or spoken words. Games will further reinforce this edge over books or seminars once VR (virtual reality) becomes fully market-ready.

Playing with and/or against others helps train a range of game-theoretic skills: wisely choosing one’s actions based on anticipated competitive reactions over a multiple-period time horizon. From cooperation to competition, a game with multiplayer features taps into the rich culture of board games humans have been playing for centuries.

As an example, a large utility company created a number of different teams role playing competitors and regulators. Each team’s task was both to decide on pricing, investment, M&A and integration priorities and to experiment with new business models while anticipating and reacting to the actions of competitors and regulators. The game play included collaborative interactions like agreeing on M&A/JV efforts. Exogenous shocks (new technologies, economic-political events) were incorporated as well to train players to stay agile and flexible. This interactive element helped the company not only to lay out strategic responses to possible contingencies, but also to get into the competitor’s or regulator’s shoes and see the world from their perspective.

3. Games allow structured analysis of an executive’s behavior. By unveiling what-ifs and routes-not-taken, well-developed games help managers reflect on their actions (and omissions). This way, even implicit choices and intermediate steps in executing a strategy become apparent and this helps in understanding the causalities that led to victory or defeat. A replay function can help retrace a player’s actions or view the game play from a competitor’s perspective. And score-keeping allows performance comparison with others.

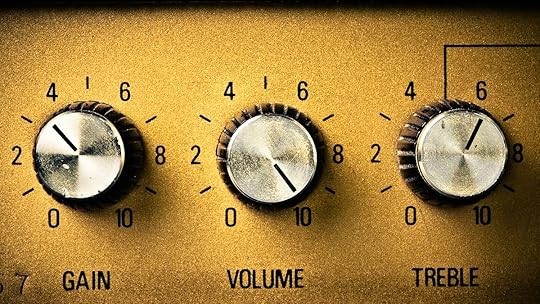

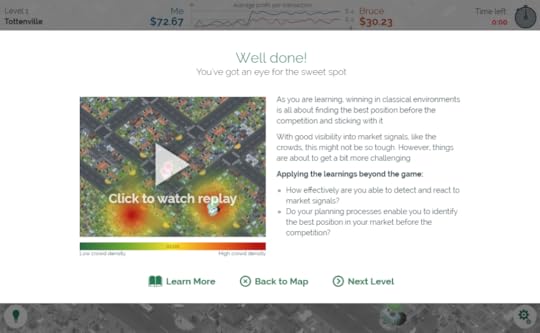

The Your Strategy Needs A Strategy game was created by BCG and Neofonie, a Berlin-based mobile computing company, to allow users to develop a hands on appreciation of the importance of choosing the right approach to strategy and execution in each business environment. It was released at the same time as a book with the same name. It features short rounds of game play in different environments and provides a running commentary on how the player is performing. A leader board allows comparison across players and identifies “best-in-class” strategists. Post action replay allows players to understand the consequences of their action (see the screenshot below). And contextualized links to relevant content allows players to deepen their understanding of what happened and why.

This process of analysis and reflection can give answers to such questions as: Was the choice of strategy incorrect, or execution flawed? To improve outcomes, does the player need to work on better observation, deeper consideration of options, greater agility, more flexibility and so on.

4. Games allow different scenarios to be tested. Strategy games can “enhance” reality by simulating different scenarios that require particular strategic responses. For example, exogenous shocks that haven’t (yet) occurred in real-life, but could plausibly materialize, can easily be modeled. How would a pharmaceutical company react, for example, when a new innovation disrupts the industry’s cost structure? Or what are the consequences of a conspicuous privacy scandal for a social networking company?

Strategy games anticipate and amplify reality by acting like vaccinations. By reacting to subcritical doses of a harmful diseases, a host develops immunity by “learning” to react for the worst case—a full scale infection.

Reid Hoffman, the founder of LinkedIn, plays The Settlers of Catan, an old-school board game, and says that tech entrepreneurs are drawn to the game because it “most closely approximates entrepreneurial strategy”. It requires players to collaborate and exchange resources to amass points, while the random rolls of the dice change the environment and require players to constantly adjust their strategies.

5. Games can be rolled out easily to many managers. Whereas conferences, seminars and coaching practically limit the number of participants, digital games display almost unlimited scalability.

Many strategy games and simulations we use today have their origin in the military sphere. The defense sector uses strategy games and simulations to train hundreds of thousands of their troops. Scalability is critical. Games only need to be programmed once, but can be rolled out to a large target audience at minimal incremental cost. Adjustments in scenarios can often be implemented comparatively easily and cheaply, by retuning a few parameters or by creating a new visual “skin” for the game.

Used appropriately, games can help corporations build strategic skills in a timely, cost effective and focused manner—a critical capability in today’s dynamic business environments. It’s time to break the taboo—and get serious about play.

Can Profit Sharing Address Income Inequality?

One of the first acts of George Washington’s presidency was to lower tariffs on the cod fishing industry, the equivalent of cutting taxes. The sector was reeling from the Revolutionary War, and the government wanted to help it get back on its feet. There was one requirement: the tax credit “would be paid only if the shipowner had a written profit-sharing contract with all the sailors.” The Washington administration wanted to be sure its support for the industry actually benefited workers.

This anecdote is the opening to The Citizen’s Share, a 2013 book by Joseph Blasi, Douglas Kruse, and Richard Freeman, economists and sociologists at Rutgers and Harvard. Their argument, reiterated last month in a New York Times op-ed, is that “we need to spread the benefits of economic growth to entrepreneurial citizens through profit-sharing and the ownership of capital.”

Their cause recently gained a notable spokesperson; the op-ed followed shortly after Democratic presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton announced her support for a tax credit for businesses that commit to sharing profits with workers.

The problem profit sharing seeks to solve is real enough: in the U.S., corporate profits are healthy, but that wealth is not being widely shared. Would more profit sharing help?

The first thing to know about profit sharing is that it’s already quite common in America. According to Freeman, about 35% of U.S. workers receive some form of it. Two slightly different types of compensation are captured in this statistic. The most common form of profit sharing is just what it sounds like: workers receive some cash bonus payment tied to how much profit the firm makes. If the company posts a loss, there’s no profit to be shared. By contrast, in “gain sharing,” also counted in that 35% figure, workers receive a cash bonus if their department or the company hits a certain metric. (Stock ownership and stock options are less common. Twenty-one percent of U.S. workers own stock and 10% have stock options, Freeman and his co-authors report, though there is overlap between these groups, and with the group that receives profit sharing.)

What’s the real impact on workers and companies? One common source of skepticism involves the idea that compensation is, in economic parlance, “fungible.” More of one form of compensation just ends up meaning less of another. For example, if you encourage a company to provide health insurance, it may respond by paying less in salary to keep overall costs unchanged. If you require firms to pay more for overtime, they might lower wages to make up the difference.

But Freeman and his co-authors reviewed a range of studies and concluded that profit sharing really did increase workers’ total pay. “Generally, the places that put in profit sharing systems tend to be more productive and workers’ total compensation goes up,” said Freeman.

The mechanism is simple: employees have an incentive to work harder because they share in the upside; that results in higher productivity, which means higher profits, some of which then gets paid out to workers. (In the most successful examples, workers help monitor each other’s behavior to prevent “free riding.”)

The positive impact on productivity is a bit stronger for profit sharing than for stock options or grants, according to research, but Freeman thinks there’s an advantage to having some of both. Profit sharing helps give workers a short-term incentive; stock options can incentivize the long-term view.

Another argument for profit sharing, made by Harvard economist Martin Weitzman, is that it could help wages adjust during recessions. One of the main theories of cyclical unemployment is that wages don’t fall quickly enough during recessions, and so firms end up firing workers instead. If some portion of compensation is profit sharing, then compensation can more easily adjust to changing economic circumstances.

Unions introduce another set of questions. Management has sometimes used profit sharing as a concession, to dissuade workers from organizing. I wanted to know if Freeman, who has also done extensive research on unions, saw profit sharing and unions as complements or substitutes. He argued that unions are necessary because not all workers will gain equally under a profit sharing regime, especially as the gap between highly profitable firms and the rest continues to grow. (For more on inequality between firms see here, here, and here.)

“I’m a worker working in a company that happens to be very profitable. You’re a worker working in a company that’s really doing very badly. That’s going to create more inequality,” he said. “You need to have some other mechanisms to make sure that the labor market doesn’t divide up massively between the profitable guys and the unprofitable guys.”

At the end of their book, Freeman and his colleagues offer a series of policy recommendations to further profit sharing and worker ownership. Among them is a tax incentive for firms that offer profit sharing, not altogether dissimilar to what Clinton is proposing.

But not everyone sees profit sharing policies as a cure all. Washington Post columnist Robert Samuelson, for example, has questioned how easy it would be to implement such policies, and suggested that it might just serve as a tax break for firms already sharing profits, rather than incentivizing new firms to give it a try.

And some conservatives are skeptical, arguing that if companies could make more money through profit sharing they would have figured it out by now. (More on that last line of reasoning here.)

One of the most interesting proposals from Freeman and his coauthors concerns executive compensation.

In theory, U.S. companies today can’t claim a tax deduction for pay to their top five executives beyond $1 million each. But there’s a loophole, put in place under the Clinton administration, which renders this virtually irrelevant: companies can deduct any executive compensation that’s structured as performance pay. So if a firm pays the CEO $1 million in base pay, then $5 million more tied to various incentives, they’re allowed to claim a tax deduction for all of it.

Freeman and his co-authors think this performance pay shouldn’t be eligible for deduction unless the firm extends something similar to all of its workers. They draw a parallel to health insurance and retirement benefits. “If a company provides a pension or health insurance system only for their top executives, it can’t deduct that as a cost of business,” said Freeman. “Our plan calls for treating performance pay systems just as we do retirement benefits and health insurance under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). The firm gets a tax advantage from providing these benefits as long as the plans cover everybody.”

It’s an intriguing proposal, especially with CEO performance pay under fire for its contribution to inequality and short-termism. Fine, Freeman and his colleagues argue, keep your performance pay tax break. But only if every worker gets some share of that upside.

The Most Common Mistakes Companies Make with Global Marketing

Marketers often find themselves at the forefront of a company’s global expansion. The marketing team is usually responsible for carrying out the market research that will determine where a company should expand, and it’s usually charged with creating a plan for attracting customers.

As a former business consultant to marketing executives at companies trying to expand globally, I’ve noticed some common marketing roadblocks that can stand in the way of international success:

1. Not specifying countries. Executives tend to think about overseas markets in vague regional terms (e.g., “We’re shifting our focus to Asia,” or “We’d like to double our growth in Europe”), but this oversimplification is problematic. Ask people what they mean by “Europe” and you’ll get widely varying answers—Western Europe, the European Union, the euro zone, and so on. Customers identify at the national level, and marketers need to remember that every country has its own local laws, cultural norms, forms of currency and payment, and unique business practices.

It’s essential to break up broader geographic “markets” into individual countries with distinct revenue and lead generation goals—and to conduct adequate local market research. Being more specific from the beginning helps tremendously with prioritizing one market over another, creating a staffing plan, and budget allocation—all of which are necessary for helping a company achieve its desired global goals. Research into local markets has to be aimed at understanding the market size, the challenges customers face, the solutions they currently have, and where your product can fit in. Many companies fail to think about these basics of product positioning at the country level and overlook things like strong local competitors.

2. Not paying enough attention to internal data. Developing a global market entry strategy requires more complex and specialized market research. In the vast universe of data that can help you figure out which markets are best for you, the most important data points are: 1) how much estimated opportunity is available in that market, 2) how easy it will be for your company to do business in that market, and 3) how much success you’ve already had with that market.

Many companies rely heavily on external data sources to guide this decision-making. However, analyzing your own data will help you answer the latter two questions and determine whether you have a strong product-market fit. Are you seeing a surge in leads from a particular market, in spite of not investing heavily there? Do you see a shorter sales cycle or a higher win rate in some countries? Is the average purchase price higher in a given market? Third-party data sources don’t know your customer or understand your brand – only you can answer these types of questions. Marketers can do a better job of utilizing their own data to prioritize their global marketing decisions.

3. Not adapting their sales and marketing channels. Many companies (especially Western ones) believe they can enter new markets by following the same playbook that brought them domestic success. While brand consistency is important, different markets favor different sales and marketing approaches. For example, in countries where relationships have a higher cultural value, such as Japan, selling products and services through local partners, such as resellers or channel partners, achieve faster success than direct sales models. Conversely, SaaS, online, and “touchless” sales models are often popular in markets where the cost of living is higher and automation is prized, such as the Nordic market.

Similarly, marketers need to change up their own channels according to the behaviors of each market, and this can vary across countries within the same region. For example, in Brazil, a marketing campaign might find more success with promoted messages on Facebook due to the popularity of this social network there, while in other Latin American countries, Twitter might attract a larger audience more quickly, and thus be a more effective marketing tool. While some channels work across a large number of markets, you want to explore what delivers the best result in each market by conducting detailed market research that relies heavily on local, in-country experts in advance.

4. Not adapting the product offering. Companies achieve “product-market fit” one country at a time. Yet all too often, companies try to launch identical products in different markets, ignoring the fact that they’re dealing with very different customers. For example, a software company won’t succeed abroad if it sells the same product that it sells at home if users in the new market aren’t as familiar with certain advanced features. Instead, they should start with a more basic version of the product to get people accustomed to it. Likewise, a more advanced market might require more features than a product currently has available.

Pricing is a similar issue. Because the value proposition varies from one market to the next, pricing will vary. While it’s not always essential for companies to change their pricing structure for international markets, many companies find that they are able to grow much more quickly by making adjustments at the local level. Forms of payment vary widely from one country to another. Marketers need to consider different pricing strategies for markets that are predominantly cash-based versus credit card-oriented, for example.

5. Not letting local teams lead the way. One of the most disappointing mistakes that I’ve seen companies make is that they hire highly competent, intelligent local people to serve their overseas markets, but then fail to consider their input when making strategic decisions.

In my global consulting engagements, marketing executives would often ask me, “What do you think our best way forward is in France? Why aren’t we succeeding there? What should we do differently?” My answer was often, “Ask your local teams.” They would frequently admit that they hadn’t tapped resources like the salespeople who sold there, and their local partners, vendors, consultants, and customers.

This is extremely important, because these individuals not only know the country in question, they know your business. The biggest challenge companies face with incorporating local insight tends to be communication. The marketing team must therefore put a system in place to help ensure that local views are captured and disseminated frequently enough. Don’t bring your company into a country the hard way. Leverage your existing relationships, and make sure to give their feedback extra weight. They are by far your most credible advisors.

6. Not thinking through the global logistics. Marketers use software that enables them to publish content on their website, send out email communications, publish social media updates, and carry out other key marketing tasks. But the same tools don’t support every market. For example, perhaps the software you use to conduct webinars only supports five languages, while your marketing automation software allows you to market in dozens of languages. Maybe your payment solutions only work for a few countries, but yet your CRM is filled with contacts from more than 100 countries.

Marketers need to ensure that they can actually market to people in the countries they’re looking to enter, which means considering details like how to display local currency, being able to email customers in their time zone, and supporting the languages customers speak.

As business continues to become more global, companies can gain competitive advantage by focusing their marketing efforts on targeting the right international markets and adapting their products and strategies to appeal to local customers. They’d be wise to avoid these pitfalls.

September 4, 2015

You Can’t Understand China’s Slowdown Without Understanding Supply Chains

HBR STAFF

The last few weeks have brought news of turmoil in China, including currency devaluations, an economic slowdown, and a stock market plunge. Most economists, including those at the the IMF, think it is premature to talk about an economic crisis. While I agree, I nonetheless believe that the slowdown is due, in part, to an acceleration of “near-shoring,” the practice of producing closer to the customer.

My evidence is a series of separate surveys conducted by different organizations, including the MIT Forum for Supply Chain Innovation.

The MIT Forum launched an online survey in 2012 to understand what U.S. manufacturers were doing about bringing production back to the United States and what factors were driving their decision process. One-hundred fifty-six U.S. manufacturing companies, defined as firms that have their headquarters in the United States, responded. The resulting report, U.S. Re-shoring: A Turning Point, indicated some shift in manufacturing footprint. While 33.6% of respondents stated that they were “considering” bringing manufacturing back to the United States, 15.3% of U.S. companies responded that they were “definitively” planning to do so. The results of the 2014 survey — to which 89 U.S.-based companies and 33 non-U.S.-based companies responded — were very similar.

The more recent AlixPartners survey of manufacturing and distribution companies serving North America and Western Europe suggests that this process is accelerating: Thirty-two percent of the companies surveyed reported that they have already near-shored or are in the process of doing so to meet end-market demand. Of the company leaders surveyed, 48% said near-shoring activities are likely within the next one to three years.

Another indication that near-shoring is accelerating is the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI). This index, which is compiled monthly, shows changes in manufacturing activity. A value of 50.0 means no change, while a value above it means an increase in activity and below it a decrease in activity. China’s PMI was 49.7 in August and 50 in July, reflecting a real decline in activity. In comparison, the U.S. PMI was 51.1 in August and 52.7 in July, reflecting a decrease in growth but not a decline in activity, and Europe’s PMI slipped slightly to 52.2 in August from 52.3 in July. Altogether, these figures suggest that the decline in manufacturing activity in China is related to both a softening of local market demand and the impact of near-shoring.

Of course, bringing manufacturing to the United States does not necessarily imply more U.S. manufacturing jobs; nor does it necessarily imply that China is changing its position as a manufacturing hub. However, it may suggest that the world is in the middle of a transformation, with companies moving from a global manufacturing strategy, whose focus is on low-cost countries, to a more regional strategy, where China is for China, the United States (or Mexico and Latin America) is for the Americas, and Eastern Europe is for European markets. As the recent surveys suggest, this trend has picked up pace in the last few years not only because of pressure to return manufacturing jobs to the United States but also because the economics that made off-shoring attractive in the first place have changed for the following reasons:

Oil prices. The move to low-cost manufacturing in the 1990s was driven in part by cheap oil prices. However, the price of oil then tripled in the last decade. As a result, logistics costs increased significantly compared to what they were when the decision was made. Yes, the prices of oil have recently fallen. But so have the prices other commodities, and another twist is the increase in U.S. production of cheap natural gas (using new fracking technology). This means that for some industries, the lower cost of manufacturing in the United States may outweigh the lower costs of shipping goods from China.

Labor costs. In the last few years, labor costs in China have increased annually by almost 20% versus 3% in the United States and 5% in Mexico. So if your company made production-sourcing decisions five, seven, or 10 years ago, it may need to revisit those decisions today.

Automation. Cheap sensors, fast computing, and new technologies have led to new user-friendly manufacturing automation that increases productivity. This improvement in productivity changes the economics and reduces the importance of low labor costs. As a result, the focus of manufacturing companies is more on skillful workers than on countries with low labor costs.

Risk. Global companies have realized in the last few years that strategies such as outsourcing and off-shoring have significantly increased risk because their supply chain is geographically more diverse and, as a result, exposed to all sorts of potential problems. A recent example is the explosion at a warehouse in Tianjin that ships hazardous materials, which was most likely caused by a company culture that flouted regulations. This drives companies to reevaluate their supplier and manufacturing base in order to increase flexibility and reduce risk.

The current turmoil in China will most likely accelerate the trend to near-shoring, but the impact will vary by specific industry and company.

For high tech industries (e.g., the manufacture of laptop computers and mobile phones) recreating the infrastructure in China somewhere else would be expensive and difficult to do. In contrast, it will be easier for footwear and apparel companies to move to lower-cost locations. Manufacturers of heavy products such as appliances or cars that are heavily influenced by shipment costs may find it pays to move production closer to market demand.

The bottom line: Companies need to evaluate on an ongoing basis whether the trade-offs for their particular industry have shifted enough to justify a change in their sourcing strategies.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers