Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1251

September 14, 2015

What Economists Get Wrong About Measuring Productivity

I find it interesting to listen to economists talk about U.S. productivity growth – or the lack thereof. It has been a source of much fretting over the years. The 3+%/year labor productivity growth rates of the 1950s and 1960s slowed to under 2% in the 1970s and then to 1.5% in the 1980-1995 period. There was a heartening rally between 1996 and 2004, when growth returned to its 1950s/1960s levels of 3% — a performance almost universally attributed to the efficiency gains from information technology.

But just as the economists and IT enthusiasts were completing their victory lap, productivity growth headed into the doldrums for a decade — growing at an anemic 1.4%/year from 2005-2014, with the slowdown starting well before the global financial crisis. When the first quarter of 2015 revealed a 3.1% decline on the back of a flat 2013 and +0.7% 2014, it precipitated much wailing and gnashing of teeth. Thankfully, the just-released revisions to the second quarter 2015 growth of 3.3% wiped out the first quarter decline and helped economists breathe a collective sigh of relief that we aren’t necessarily going into a hell in a productivity hand basket.

As I read all the productivity analyses and commentary, including the recent one on these pages by the clever folks at the OECD, I am struck that in trying to understand productivity, economists exclusively look at only one half of the productivity equation — literally not figuratively. That impedes their ability to understand what is really going on with productivity in the modern economy.

Most people instinctively think of productivity as a quotient: a physical output (e.g., a ton of coal) divided by a physical input (e.g., labor hours). They wouldn’t be wrong; that is where productivity measurement started.

But to say something useful about the comparative productivity of different kinds of enterprises, you can’t compare the output “one ton of coal” with “one automobile” to judge the one that used fewer labor hours to be “more productive”. It is, of course, apples and oranges. To make the comparison you need to convert the numerator from a physical measure to a financial one — conventionally the dollar value added (essentially a product’s selling price less purchased inputs), which is also how economists measure a country’s Gross Domestic Product. Once you have a dollar figure for the numerator you can compare the productivity of labor across industries and jurisdictions in terms of dollar value-added created per hour worked.

So far, so reasonable, but when figuring out how to improve productivity, researchers almost always focus on the direct determinants of the denominator — they think about how to use technology, training, re-engineering of work processes, and automation in order to reduce the number of labor hours required to produce a given product or service.

The numerator is entirely ignored as if the value of the output was fixed and immutable. However, as any student of strategy knows very well, the dollar value-added that a firm generates is directly proportional to what it can charge in the marketplace for its products or services. And that price is, in turn, highly sensitive to the competitive dynamics of the firm’s industry and the strategic decisions it makes. Given the basic dynamics of a quotient, changes to the numerator are equally important to results as changes to the denominator.

An example of the impact of changes in competitive dynamics can be seen from our experience with globalization. After China joined the WTO in 1997, the effect of its exports on many U.S. markets was to systematically reduce prevailing price levels. While ignored by economists, this has created massive downwards pressure on U.S. labor productivity as Chinese exporting ramped up after 2000. Many US firms in many U.S. industries had no chance to reduce their denominator (labor hours) as fast as the market-driven numerator (prevailing price levels) fell. While on a physical basis, many were reducing the labor hours per unit (of whatever they were producing), their efforts were swamped by the reduction in the value those units generated. That shows up in an economy-wide reduction in the pace of productivity growth in the past decade.

That notwithstanding, there is little discussion among economists of the mixed impact of globalization on US productivity growth numbers. Most consider globalization an unalloyed good for productivity — because it reduces denominators. While it almost certainly increases the efficiency of the economy, there is no reason to expect that it will result in an observed increase in productivity.

Economists do try to account for this kind of effect by making what they call “hedonic adjustments.” Literally, they take the price of a good (let’s say a PC) and adjust it (in this case upward because over time the consumer has gotten more for less in their PCs) to take into account quality changes. But I struggle to take seriously the notion that any economist can accurately or even usefully re-price goods across the entire economy based on their “true value” rather than their prevailing price.

What about the second factor: strategic decisions? These also have a direct impact on the numerator. If, thanks to choices around, say, product design, brand-building or selection of distribution channels, your product or service is hugely attractive to customers, you will automatically have high productivity, almost regardless of what you do to the denominator.

Take Apple. An iPhone 6, with largely the same physical properties, sells for two times a HTC Desire because Apple has created a user experience and brand that causes consumers to pay whatever it decides to charge. As a result, Apple has sky-high productivity versus HTC — which is struggling to make ends meet in the smartphone business. It is simply and clearly a function of a strategic choices influencing the numerator, not the size of the denominator.

Yet the impact of these kinds of decisions seems to be almost completely ignored by productivity economists. It is a shame. All of the economists and policy wonks obsessing about low U.S. productivity growth focus, at best, on half the problem, which is like going into a fist-fight with one arm tied behind your back. When productivity recommendations are made, they never point out the need for smarter strategic decisions on the part of U.S. company executives — except for smarter decisions on adoption of labor-saving technologies.

A Refresher on Current Ratio

One of the biggest fears of a small business owner is running out of cash. But large businesses in financial trouble face the same risk. To know whether a company is truly on the cusp of hitting a $0 balance in their accounts, you can’t simply look at the income statement. You need to run a simple calculation using a few figures.

That’s where the current ratio comes in. I talked with Joe Knight, author of the HBR TOOLS: Return on Investment and co-founder and owner of www.business-literacy.com, to learn more about this financial term.

What is the current ratio?

It’s one of several liquidity ratios that measure whether you have enough cash to make payroll in the coming year, explains Knight. The current ratio measures a firm’s ability to pay off its short-term liabilities with its current assets. It is closely related to the quick ratio, which is often called the “acid test” because people use it to understand “if things got really ugly, could you stay afloat?”

How do you calculate it?

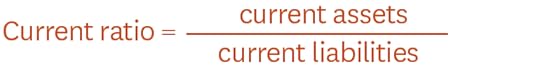

The formula for current ratio looks like this:

Note that “current” in financial terms means a period of less than a year. So your current assets are things that you could convert into cash within the year. They include cash on hand and short-term investments. They may also include your accounts receivable, inventory, and accrual payments, depending on your business. For example, accounts receivable may not seem like it could be quickly liquidated but there are third parties, explains Knight, that will buy a company’s accounts receivable in certain sectors. This is called “factoring”. Whether you can quickly liquidate inventory can also be industry-dependent. “Look at Goodyear,” explains Knight. “Chances of selling a million dollars of rubber fast are slim.”

Your current liabilities are things you expect to settle in the next year. “One of biggest liabilities on the income statement is accrued expenses,” says Knight. Those are the amounts that you owe others but haven’t yet hit your accounts payable liability. One of the biggest of these expenses, for companies, is accrued payroll and vacation time. You owe employees for their time but they don’t ever invoice your company so it doesn’t hit accounts payable.

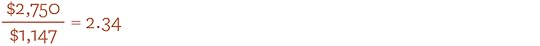

Here’s an example of how the calculation is done. If your business has $2,750 in current assets and owes $1,174 in current liabilities (again, you can pull these figures from your company’s balance sheet) then the current ratio is:

(Note that the ratio isn’t usually expressed in a percentage)

As with the debt-to-equity ratio, you want your current ratio to be in a reasonable range, but it “should always be safely above 1.0,” says Knight. “With a current ratio of less than 1, you know you’re going to run short of cash sometime during the next year unless you can find a way of generating more quickly.”

But the ratio can also be too high. The current ratio for both Google and Apple “has shot through the roof,” says Knight. “Apple’s current ratio was recently around 10 or 12 because they amassed a hoard of cash.” But investors get impatient, saying, “We didn’t buy your stock to let you tie up our money. Give it back to us.” And then you’re in a position of paying dividends or to buy back stock from your investors.

Now let’s look at the formula for the closely related quick ratio:

Note that quick ratio is the same as the current ratio with the inventory removed. Why? As discussed above, inventory can be tough to sell off so when you subtract it, nearly everything else in the liabilities is cash or easily turned into cash. “So this ratio will tell you how easy it would be for a company to pay off its short-term debt without waiting to sell off inventory,” explains Knight. “For businesses that have a lot of cash tied up in inventory, lenders and vendors will be looking at their quick ratio.” However, most people will look at both together, says Knight, often comparing the two.

How do companies use it?

Knight says that this is the first ratio he runs when looking at whether to invest in a business because it quickly tells him how solvent the company is. “I would go on to look at others, of course, but this would give me a sense up front of where the business stands.”

Bankers pay close attention to this ratio and, as with other ratios, may even include in loan documents a threshold current ratio that borrowers have to maintain. Most require that it be 1.1 or higher, says Knight, though some banks may go as low as 1.05. “If you’re below 1, you’ll be turned down quickly,” he says.

Managers may not be monitoring the current or quick ratio every day but they can have a great impact on it. “A lot of current liabilities are touched or managed by individuals in the company,” he explains. These include accounts payable, accrued vacation, deferred revenue, inventories, and receivables. So if your job includes managing any of these assets or liabilities, you need to be aware how your actions and decisions could affect the company’s current ratio. Even, for example, if you allow your team to rack up vacation time, it can have an impact on these figures.

This ratio can be helpful for people outside your company who are looking to do business with you. Potential partners may use it to understand how solvent you are. Suppliers may want to know whether they’re going to get their bills paid and customers may want to know how long they’re going to be able to do business with you if they rely on your product or service.

Of course, private companies don’t advertise their current or quick ratios so this information isn’t immediately available to everyone. “Whether you get this information about a company or a potential partner depends on what leverage you have with them,” says Knight.

What mistakes do people make when using current ratio?

These are relatively straightforward calculations to make. The tricky part is deciding what to include in the numbers. “There are many different ways to figure current assets and current liabilities and just as many ways to fudge the numbers if you wanted,” says Knight. “So if you’re outside a company, looking in, you never know if they’re telling the complete truth.” In fact, he says, you often don’t know what you’re looking at. “When you’re looking at a statement, you’re looking at the competence and integrity of the executive team that prepared it.” Therefore, he says, it’s not a number you can easily compare with other companies. What you hope is that, in a well-run company, you can compare trends across time to see how that company is performing.

Data Is the Next Big Thing in Content Marketing

The diminishing effectiveness of conventional advertising and the rise of social media have led more and more brands to embrace content marketing. More and more companies are seeing themselves not just as advertisers, but as publishers, launching digital newsrooms, podcasts, and other forms of branded content in order keep their brands, perspectives, and value propositions in front of customers.

Yet even as companies have embraced their new role as content creators, they’ve largely missed out on one of the hottest trends in the world of traditional media: data journalism. This still-new form of reporting draws on the growing availability of data sets and data analysis tools to uncover and tell stories like the impact of vaccines on infectious diseases, the continuing problem of school segregation, or the differences in working hours across industries, often presenting the results through compelling visualizations or interactive applications. Newspapers such as The Guardian and The New York Times have invested heavily in data journalism because they recognize that the world of big data offers opportunities to uncover new insights, and to tell stories in newly compelling ways. Just as crucial, data-driven stories attract the kind of social media attention that publishers dream about: fresh data and infographics spread across Twitter, Facebook and other social channels precisely because they are able to tell a story in a concise, compelling and visually appealing way.

While infographics are now a standard part of the corporate communicator’s toolkit, data visualizations driven by original data are still few and far between. Look on Pinterest and you’ll see that a lot of corporate infographics are basically pretty blog posts, not data visualizations that tell an original story.

That’s an ironic oversight because today’s enterprises have access to more data than ever before. All that information could be fodder for top-notch marketing; instead, it’s treated like a state secret, and used almost exclusively to drive internal decision-making. Look up “data-driven content,” and you won’t find much about turning data into blog posts or reports: you’ll mostly find marketers using data to guide their own campaigns and marketing decisions.

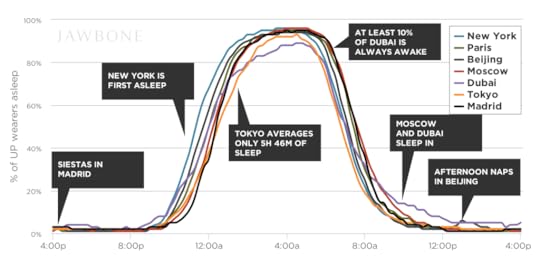

The exceptions to this rule are the few companies who’ve used their own data to drive original and fascinating stories: companies like OKCupid, General Electric, and Kickstarter. My personal favorite is Jawbone, which has uncovered some fascinating insights from all the folks wearing its fitness trackers – like when people in different cities wake up and go to sleep (below). These brands recognize what virtually every brand should be doing: opening the treasure chest of data and offering some of that wealth back to customers and the public in the form of original content.

I woke up to the power of data as a content marketing resource through my work with Vision Critical: because a lot of global businesses use Vision Critical’s customer intelligence software platform, we were in a great position to develop reports like Sharing Is the New Buying (with Jeremiah Owyang) and What Social Media Analytics Can’t Tell You. Working on those reports opened my eyes to the benefits that a quantitative approach can offer any business:

Traffic. Infographics are the type of content that’s most likely to be shared on social media, so creating data visualizations that offer real value to your readers is a great way to spread your ideas and message — and to drive traffic to your site. Unlike a typical blog post, a data visualization or report has some staying power, particularly if you choose your title keywords carefully so that your posts show up whenever people search for numbers on your topic or industry.

Value. The rise of brands as publishers has led to an explosion in the volume of content available online. And let’s be honest: most of it is terrible. From the endless spew of blog posts meant to establish a “personal brand” on a given subject, to the daily grind of keeping corporate websites stocked with up-to-date releases, a lot of what’s getting cranked out offers more in terms of word count than it offers in actual information or actionable insight. When you’re sharing fresh, accurate, relevant numbers, you are offering content that gives people real value.

Authority. Sharing, curating, and analyzing data — particularly if it hasn’t been shared before — establishes your brand as the authority on a topic. If you can release a report or infographic that offers a new or definitive take on a key set of market trends or issues, you become the go-to source on that subject. That may bring earned media mentions and interview requests, but just as crucially, the report itself highlights your company’s expertise. For B2B companies in particular, underlining expertise is often one of the top aims of content marketing, and data-driven content accomplishes that goal very effectively.

Learning. Data analysis skills are turning out to be ever more important in today’s enterprise, so a lot of businesses have significant strength when it comes to using analytics internally to drive business decisions. But when you start sharing your metrics externally, you can get a whole new perspective — because seeing how other people respond to and make sense of it may give you fresh insights into numbers you think you already know inside and out. That’s particularly true if you take a page from the rise of the open data movement in government, and actually release some of your data in a form that other people can use to create their own charts or analyses: they may find patterns and insights you would never have thought to explore.

Transparency. At a moment when consumers are increasingly concerned about the way that companies collect and use their personal information, data-driven content offers a way for companies to let people see how their information is being used. That transparency not only builds trust, but helps to address their concern that they give up more value by sharing their information than they receive back from the companies who collect it. By aggregating the data in a way that preserves the privacy of individual users, and provides insight based on the patterns revealed through that aggregation, brands can help customers understand how their data is being used.

For all the value that data-driven marketing can offer, it’s still an under-used part of the marketer’s toolkit — and as a recent Nieman Lab post observed, many of the companies that have ventured into this space are doing it poorly. But precisely because well-executed data storytelling is still the exception, there’s an enormous opportunity for companies to stand out from the marketing hordes by turning quantitative information into quality content.

Consuming Negative News Can Make You Less Effective at Work

We’ve known for some time now that hearing negative news broadcasts can have an immediate effect on your stress level, but new research we just conducted in partnership with Arianna Huffington shows how significant these negative effects can be on our workdays. Just a few minutes spent consuming negative news in the morning can affect the entire emotional trajectory of your day.

In 2012, we conducted a yet-to-be-published preliminary study with Martin Seligman at the University of Pennsylvania where we found that just a few minutes of negative news has a significant effect on mood. This year, we partnered with Arianna Huffington to examine the longer term impact of news on well-being and performance. In this study, 110 participants were blindly placed into one of two conditions: one group watched three minutes of negative news stories before 10 a.m.; the second group watched three minutes of solutions-focused news. This is important: the second group did not watch saccharine stories about cute puppies, rainbows, and waterskiing squirrels (although we love that viral video). The solution-focused news group watched stories of resilience to build the belief that our behavior matters. Two of the videos included inner city kids working hard to be successful in a school competition, and a 70-year-old man who got his GED after failing the test dozens of times. Then, the participants were emailed six hours later and asked to fill out a survey within two hours. This survey contained a battery of positive psychology metrics to gauge things like stress and mood. We were stunned by the results (we even reran the analyses to double-check it) because the effects were much more significant and dramatic than we expected. Individuals who watched just three minutes of negative news in the morning had a whopping 27% greater likelihood of reporting their day as unhappy six to eight hours later compared to the positive condition.

In the next phase of our research we will investigate the impact of negative news not just on individuals’ mood but on their performance. We’ll look at the effect of watching negative news on TV while at the gym, as well as the effect of negative news stories on sales and customer service at call centers in the Midwest. Our hypothesis, given substantial evidence that negative moods affect workplace performance, is that it will have a negative impact on performance levels in both cases.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Managing Stress at Work

Managing Yourself Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

We believe that negative news influences how we approach our work and the challenges we encounter at the office because it shows us a picture of life in which our behavior does not matter. The majority of news stories showcase problems in our world that we can do little or nothing about. We see the market dropping 500 points or ISIS poised to attack, and we feel powerless to change those outcomes. In psychology, believing our behavior is irrelevant in the face of challenges is called “learned helplessness,” which has been connected with low performance and higher likelihood of depression.

There is an equally compelling body of research that links optimism to higher performance. In a classic study in the 1980s, for example, Seligman followed insurance salespeople at Metropolitan Life and found that optimistic salespeople outsold their pessimistic counterparts by 37%. Our own research has shown how quickly positive cues can affect our behavior. In our previous HBR article, Positive Intelligence, we described how a group of hospitals in Louisiana trained 11,000 doctors, nurses and staff to make eye contact and smile at people who walk down the hospital hallways within 10 feet of them. Just six months later, they observed a significant increase in the number of patients visiting the hospital, an increased likelihood of referring that hospital based on the quality of care received, and elevated engagement levels for the employees. A one-second free behavioral change taught people a different social script: we are connected and your positive behavior can have a real impact on others.

We’ve also seen this at play out at our client companies, with the most compelling example coming from Nationwide Insurance. The president of Nationwide Brokerage Solutions, Gary Baker, decided to apply positive psychology research to the company’s workday. In particular, employees begin their days with a “huddle,” where they meet to share good news and rally around colleagues who might need some extra support that day. Those positive starts to the day, among other changes instituted based on positive psychology training at Nationwide, have led to an increase in gross revenues from $600 to $900 million and an application rate 237% higher in just one year. (Some might argue that this is correlation rather than causation. However, J.J. Bowman, business development leader at Nationwide, said during an interview that the organic positive changes and optimism felt on the team did drive revenue, as opposed to the other way around.)

So how can you prime yourself for higher levels of performance and feel better during the day without sticking your head in the sand and tuning out the news altogether? Try these three simple, research-supported strategies:

Turn off news alerts: Since the majority of new alerts are by default negative, try turning them off for one week. Shut off push notifications to your phone or email. These alerts pull our attention away from the present moment and can lead to decreased performance, as we are distracted from our work. If there’s anything really important happening, you’ll hear about it soon enough.

Cancel the noise: In Before Happiness, we suggest that in the same way you might cancel the noise on a plane using headphones, you can turn your brain into a noise-canceling machine by practicing meditation. Or, try turning off the radio for the first five minutes of your commute. When you do turn the radio back on, don’t listen to angry talk radio, and mute at least one set of commercials per show. It’s hard to tune into the signal of our own lives when we’re bombarded by the noise that surrounds us.

Change the Ratio: Start your day with empowering, solutions-focused news. Seek out stories on your favorite news site that are transformative, which means that they empower people with actions steps and potential solutions instead of just focusing on the problems. Occasionally, skip clicking on stories that are hypothetical or about tragic one-time situations that you can do nothing about. Find solution-focused news like Huffington Post’s new What’s Working series or CNN’s new impact series. If you don’t like that there’s so much negative news, don’t forget: you vote with your fingers. Every time you click on a story, you’re telling the media you want to be consuming this.

It’s possible to stay informed about the news and remain positive and focused on your own work, but only if you control your news consumption instead of letting it control you.

September 11, 2015

Why Curious People Are Destined for the C-Suite

When asked recently to name the one attribute CEOs will need most to succeed in the turbulent times ahead, Michael Dell, the chief executive of Dell, Inc., replied, “I would place my bet on curiosity.”

Dell was responding to a 2015 PwC survey of more than a thousand CEOs, a number of whom cited “curiosity” and “open-mindedness” as leadership traits that are becoming increasingly critical in challenging times. Another of the respondents, McCormick & Company CEO Alan D. Wilson, noted that business leaders who “are always expanding their perspective and what they know—and have that natural curiosity—are the people that are going to be successful.”

Welcome to the era of the curious leader, where success may be less about having all the answers and more about wondering and questioning. As Dell noted, curiosity can inspire leaders to continually seek out the fresh ideas and approaches needed to keep pace with change and stay ahead of competitors.

A curious, inquisitive leader also can set an example that inspires creative thinking throughout the company, according to Hollywood producer Brian Grazer. “If you’re the boss, and you manage by asking questions, you’re laying the foundation for the culture of your company or your group,” Grazer writes in his book, A Curious Mind. Grazer and others maintain that leading-by-curiosity can help generate more ideas from all areas of an organization, while also helping to raise employee engagement levels.

The notion that curiosity can be good for business is not entirely new, of course. Decades ago, Walt Disney declared that his company managed to keep innovating “because we’re curious, and curiosity keeps leading us down new paths.” But having that desire to keep exploring “new paths” becomes even more important in today’s fast-changing, innovation-driven marketplace.

In my own research for my book, A More Beautiful Question, I found numerous examples of current-day entrepreneurs and innovators—including Netflix’s Reed Hastings, Square’s Jack Dorsey, and the team behind Airbnb—who relied on curious inquiry as a starting point to reinventing entire industries. Dorsey, for example, was puzzled when an artist friend lost a big sale to a potential customer simply because the artist couldn’t accept a credit card. Dorsey wondered why only established businesses, and not smaller entrepreneurs, were able to conduct credit card transactions; his search for an answer resulted in Square, a more accessible credit card reader.

While curiosity has ignited numerous startup ventures, it also plays an important role at more established companies, where leaders are having to contend with disruptive change in the marketplace. “These days, a leader’s primary occupation must be to discover the future,” Panera Bread CEO Ron Shaich told me. It’s “a continual search,” Shaich says, requiring that today’s leader keep exploring new ideas—including ideas from other industries or even from outside the business world.

Advising business leaders to “be more curious” sounds simple enough, but it may require a change in leadership style. In many cases, managers and top executives have risen through the ranks by providing fixes and solutions, not by asking questions. And once they’ve attained a position of leadership, they may feel the need to project confident expertise.

To acknowledge uncertainty by wondering aloud and asking deep questions carries a risk: the leader may be perceived as lacking knowledge. In their book The Innovator’s DNA, authors Clayton Christensen, Hal Gregersen and Jeff Dyer observed that the curious, questioning leaders they studied seemed to overcome this risk because they had a rare blend of humility and confidence: They were humble enough to acknowledge to themselves that they didn’t have all the answers, and confident enough to be able to admit that in front of everyone else.

While we may tend to think of curiosity as a hardwired personality trait—meaning, one either is blessed with “a curious mind” or not—according to Ian Leslie, author of the book Curious, curiosity is actually “more of a state than a trait.” We all have the potential to be curious, given the right conditions.

Leslie notes that curiosity seems to bubble up when we are exposed to new information and then find ourselves wanting to know more. Hence, the would-be curious leader should endeavor to get “out of the bubble” when possible; to seek out new influences, ideas, and experiences that may fire up the desire to learn more and dig deeper.

Even when operating within familiar confines, curious leaders tend to try to see things from a fresh perspective. The ones I studied in my research seemed to have a penchant for bringing a “beginner’s mind” approach to old problems and stubborn challenges. They continually examined and re-examined their own assumptions and practices, asking deep, penetrating “Why” questions, as well as speculative “What if” and “How” questions.

Such leaders sometimes also evangelize about curiosity, urging people in their organizations to “Question Everything.” This can serve to model the behavior for others, though leaders may have to go much further—providing sufficient freedom and incentives—in order to actually create the conditions for curiosity to flourish company-wide.

In the end, it isn’t necessarily easy for a leader to foster curiosity on an individual or organizational level—but it may be well worth the effort. “With curiosity comes learning and new ideas,” says Dell. “If you’re not doing that, you’re going to have a real problem.”

Don’t Let Your Stressed-Out Boss Stress You Out

Is your boss stressed to the max and making you miserable? Join the club. Stress is an epidemic among managers and leaders today, and burnout is catching up fast.

We all know the reasons: the rapidly changing economic landscape; fast-moving technologies; 24/7 work with little to no downtime. It all adds up to far too much pressure. We’ve all been doing too much for too long, which has left your boss (and maybe you) trapped in the Sacrifice Syndrome: Everyone’s been giving and giving and giving…and now we have nothing left to give. A boss who may have once been known to lead with emotional intelligence, build a great team, and motivate people becomes a grumpy, cynical, anxious person when stressed. He’s now hovering over you, or worse, disappearing when you need him most.

What happens next is where the real problems crop up: you become stressed, too! You literally catch your boss’s destructive emotions. You’ve become demotivated, frustrated, and even angry. You want out. If you can’t quit, you dial back your contribution and just try to wait it out. Now it’s a matter of your own survival.

You and Your Team

Stress

Don’t let it get the better of you.

It’s stunning how quickly your stressed-out boss can turn you into a stressed-out team member. This is partly because of the contagious nature of emotions. They spread like wildfire among people—and even faster if one of those people has some control over our fate, as bosses do. Another reason our boss’s stress becomes our own is that many of us are already close to stressed-out ourselves. We too have been sacrificing and giving up a lot for a long time, and the cracks are showing. It doesn’t take much to push us into a bad place.

Let’s look at a real person—a friend and colleague whom I’ll call “Nathan.” Two short years ago, Nathan was quietly thrilled to step into senior management. Sure, he’d heard through the grapevine that his new boss Geoffrey was “tough”, but he’d had difficult bosses before. Nathan also knew he was tired from the climb to the top. He had been running hard for a long time, but this was what he’d been waiting for all his life, right? He could dig deep and find the energy for the big leap this job required.

During the first few months with the company, Nathan realized two things: first, he didn’t have as much energy as the last time he started a new job. Second, he was stunned to realize that the honeymoon disappeared before he could even enjoy it. Geoffrey was on him all the time. Nothing he did was right. At first, he thought it was his fault—maybe he needed to try harder, speed up, step up. He did so. It didn’t work. Geoffrey was still caustic and he just seemed so angry all the time. A year in and Nathan himself was getting ticked off. He’d go home and lash out—not at all like him. Nathan was catching Geoffrey’s disease, and there didn’t seem to be a cure anywhere in sight.

Despite a lifetime spent in an industry he loved, in a company he’d admired, he just couldn’t see the point anymore. In fact, neither Geoffrey nor Nathan’s team members seemed to care much about anything other than short-term results.

This leads to another problem with stressed-out bosses—what they aren’t doing. As long as they are focused on dealing with their own issues, they’re not spending time helping you to connect with what’s most important to you at work—that noble purpose your organization serves that inspires you, or that hopeful view of the future that makes you want to keep going. A sense of purpose was exactly what Nathan needed to counter the effects of the burnout heading his way, and it just wasn’t there.

So, if stress is epidemic and bosses are spreading it to us, what can we do? Let’s start by what you can’t do: you can’t change your boss or fix his response to stress. Learning how to deal with pressure is a very individual journey. If indeed your boss has tipped over the edge, no amount of perfection on your part, early-delivery of projects or compliments will help. Sure, do your job and do it well, but don’t expect miracles.

What you can do is work on yourself. First, you need to do your best to understand why your boss is burned out, then dig deep to find empathy—that unique human ability to understand another’s reality. It’s important to take some time to consciously try to recognize and understand the emotional state your boss is feeling. Engage in perspective taking by deliberately trying to see the world, events—and yourself—through your boss’s eyes. Empathy, by the way, is a key emotional intelligence competency.

This is what Nathan did. He made a conscious attempt to “get” his boss, veering away from defensiveness and anger . He tried to look at the whole picture, including his boss’s challenges with conflict on the team and a difficult chairman. Slowly, he found ways to hang out with Geoffrey, to have a laugh together now and then, and he got Geoffrey talking about his own life and family.

Empathizing with a man like Geoffrey is not easy, as our natural response to be defensive, even aggressive—not empathic. But if you can feel and express empathy, a) your boss will likely sense it, and this might help him and b) you will be able to remain grounded in the face of bad behavior, as you know it’s his problem, not yours. Paradoxically, when Nathan leaned in to this stressed-out boss, it helped to calm Geoffrey down.

Empathy also makes it easier to create appropriate emotional distance from your boss. This is a bit tricky, as you can’t shut down or have no relationship at all with him. Rather, you need to constantly monitor your own reactions and make a conscious effort to control your emotional response. Take stock and find that impermeable psychological boundary that separates you from your boss. What part of the stress and negativity belongs to him, and what belongs to you?

Then and most importantly, you need to take a good hard look at your own stress—at work and at home. How are you doing, really? Look at your relationships at home and at work. Are you testy? Irritable? Impatient? Or…nasty? We all act this way sometimes. And this kind of behavior (especially at home) is a good diagnostic.

If you see that you are heading for problems, or have entered into pre-burnout conditions, you need to do something now. Free up some time for renewal. And don’t be fooled: Renewal doesn’t happen as a result of a vacation. Remember that summer break? Seems like a long time ago, right? To deal with the kind of stress we all have at work today, renewal must become a continuous way of life, not an event.

There are a few things we know work for most everyone, such as laughing with coworkers (not at the boss!), doing fun activities outside of work, exercise, friendship, and setting healthy priorities. It’s becoming clear, too, that mindfulness meditation has a profound impact on one’s ability to stay grounded and manage stress. This movement is growing, in part because of the stress we’re all experiencing. Now, well-known mindfulness researcher Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts, Michael Baime at the University of Pennsylvania and others have now led tens of thousands of people through mindfulness based stress reduction programs, in which normal people learn to incorporate breathing and meditation exercises into daily life while increasing their own self-awareness about their stress.

You also want to engage a sense of hope by imagining how you’d like things to be at work, with your boss and probably at home. It sounds so simple, and in a way it is. Hope is natural for human beings, and it really helps with the day-to-day burden of stress. Try paying some attention to what you would like to be feeling—and why. This will help you to be optimistic and more mindful about your reactions. This requires emotional self awareness and emotional self control—two more key emotional intelligence competencies.

And Nathan? He’s still on the job, though that wasn’t a given a few months ago. About a year in, he realized that he needed to get hold of himself, as he was fast slipping into dissonance and burnout. He started to shift priorities, then realized he had to shift his mindset, first. He actually took a course on mindfulness and learned a bit about how everyday people can meditate. He brought his family into the conversation, so it didn’t feel so lonely anymore. He’s doing ok. Geoffrey, sadly, is on his way out. He just couldn’t get a grip and the entire company was starting to feel the effects.

Why and How to Build an In-House Consulting Team

In-house strategy and consulting groups are growing in popularity, supplementing and increasingly winning business from traditional consulting firms such as McKinsey & Company, Boston Consulting Group and Bain & Company. Today, many high-profile companies—Cisco, Google, IBM, Samsung, Siemens, Disney, Volkswagen and Deutsche Bank, to name a few—contain such roving consulting groups to help solve the most critical strategy and operations problems throughout the business. Internal consulting groups have a number of advantages over external firms, including a company-wide perspective, continuity into implementation, attraction of top talent to the company, higher levels of confidentiality, and greater cost-effectiveness. But building an internal consulting group is an unprecedented endeavor for many companies, and because best practices have yet to spread widely, internal consulting groups vary greatly in how they operate and the business impacts they are able to achieve.

Over the past six years, we have put in place a 30-person consulting team at EMC Information Infrastructure (EMC II) using a model we have found to be successful, winning projects away from external management consulting firms at a fraction of the cost, and with great “client” (that is to say, EMC) satisfaction. Here’s what we’ve learned about how to establish a successful internal consulting group.

Set objectives and size. Having clear objectives helps prioritize the group’s efforts and also measure success. The primary objectives in creating our team were to rein in spending on external strategy firms and to attract, train, and retain top talent in the company. Typically for an internal consulting group, we had to grow gradually as we demonstrated the quality of our work. But the key was knowing when to stop growing. We decided to cap the group’s size at 30 consultants. For a company our size, with reported revenue of $24.4 billion in 2014 and approximately 70,000 employees worldwide, this number allows us to deliver six to eight projects per quarter. Though the demand for projects often exceeds this capacity, we prefer to be able to prioritize the engagements with the highest business impact.

Win on merit. Every business leader should be able to hire the external or internal consultants of their choice. Our group welcomes the competition. Like any firm in need of business development, we build relationships with executives across the company, and pitch proposals. We call everybody within the company a “client.” We do not execute a central mandate (e.g., the CEO’s or CFO’s), but rather serve the needs of our internal project sponsors (usually at the CXO, EVP, and SVP level). This also forces us to deliver great quality on every project.

Self-fund. Numerous funding models exist for internal consulting. We encourage groups to charge their full cost back to their “clients.” Prior to starting any engagement, clients should approve a statement of work and commit to paying the “fees” for the internal consulting team out of their budgets. Therefore, the group is self-funded and neutral to the parent company from an expense perspective. This charge-back mechanism also forces our clients to prioritize their requests for support. On a typical project, the cost of engaging our internal group is four to six times lower than the fees of a big-three firm (i.e., McKinsey, Bain, or Boston Consulting Group).

Work on discrete projects. We recommend scoping, staffing, and delivering projects with set start and completion dates, and clear deliverables. Sticking to this principle is harder than it sounds. We receive numerous requests to engage outside the remit of a defined project, for instance staffing one of our consultants to augment an executive’s team, or overseeing large implementations over long periods of time. If we accepted all such requests, we would end up with 30 “chiefs of staff” or “operations leads.” That would neither be in line with our primary objectives, nor fit our consultants’ career expectations.

Exceed client expectations. To succeed long term, winning on price alone is not sufficient. Consistently convincing internal clients that the advice provided is on par with, or exceeds, what they can get externally requires a culture of over-achievement. We foster this culture by defining explicit values, encouraging team members to always speak their mind and challenge each other, investing in a full training curriculum, seeking out client feedback, and of course celebrating success. We also try to maintain a true meritocracy with competitive pay and a specific career path that defines clear expectations at every level (our titles replicated the ones external firms use: analyst, consultant, project manager, practice lead, and so on).

Attract top talent. What does it take to compete for the best? A strong value proposition and a first-class recruiting engine. In our case, the value proposition is unparalleled top-management exposure, real impact on strategy, a focus on professional development, the opportunity to transition into a management role in the technology industry after a minimum of two years with the group, and a fun team. We purposefully staff consultants on projects across business areas to make for a richer experience. We also proactively share job openings from other organizations. Team members spend 5-15% of their time either interviewing candidates, or running our recruiting campaigns for college graduates, summer interns, MBA-graduates, and experienced hires.

Be scrappy. As part of a larger corporation, internal consulting groups don’t have the luxury of hiring the extensive support staff external firms enjoy; typically 30-40% of employees at traditional consulting firms are non-consultants who provide research, presentation production, recruiting, training, and so on. At EMC, we make up for the staffing shortfall by assigning all our consultants to an “office development” team, such as recruiting, training and onboarding, knowledge management, or social committee. Though these require time commitment beyond project-work, they offer team members the opportunity to shape the group’s operations and culture, instilling an entrepreneurial mindset among our consultants.

Measure success. We use the following scorecard:

Business impact. Are we working on the projects with the highest business impact for the company?

Customer satisfaction. How satisfied are our clients with the value we provide, and the way we work?

Utilization. Does our utilization reflect strong demand and high productivity (we set our target at 75%-80%)?

Spending on external firms. Are we succeeding at reducing the company’s spending on outside consultants?

Acknowledge what you can’t do. There are three circumstances where a company should always turn to external firms: when there is a sudden need for a large number of consultants (e.g., crisis management), when deep expertise in a specific functional area is required (e.g., indirect procurement), or when findings are intended to be quoted publicly.

In a seminal 2013 HBR article, “Consulting on the Cusp of Disruption,” Clayton M. Christensen, Dina Wang, and Derek van Bever predicted the disruption of elite consulting firms. We believe the rise of high-impact, in-house consulting firms will play a role in this disruption. Our advice is to operate as a professional services firm within the company, to define a business model, and be unrelenting in its execution.

The 7 Attributes of the Most Effective Sales Leaders

Every salesperson knows the quality of their sales manager will have a profound impact on their own success. A recent study I conducted proves this point. Sixty-nine percent of salespeople who exceeded their annual quota rated their sales manager as being excellent or above average. In addition, the quality of the sales organization is directly associated to the quality of sales leadership. Fifty-six percent of salespeople who rated their sales organization as excellent also rated their sales manager as excellent—compared to only 3% who rated their organization as average.

If the best sales organizations have great sales leaders, what separates high-performing sales leaders who exceed their quota from underperformers who miss their quota by more than 25%?

To find the answer to this question, over 400 sales leaders (vice presidents of sales and frontline sales managers) completed an extensive sales management performance study. Twenty-nine percent of participants met or exceeded their annual quota last year, while 42% achieved between three quarters and all of their quota. Twenty-nine percent achieved less than 75% of their annual quota.

I also interviewed over 1,000 sales leaders to better understand the impact of management styles and personality patterns on sales success. This combination of quantitative and qualitative research provides insights about the attributes of high-performing sales leaders compared to their less successful counterparts. These attributes are described below in order of priority.

Target fixation. The best sales leaders are target and deadline driven. In personality testing, top sales managers scored 19% higher in the self-discipline facet, 20% higher in the success-driven facet, and 27% higher in the priority-focused facet than underperforming sales managers. As a result, they have the natural disposition to fixate their team on achieving their revenue goals at the exclusion of all else. They block out distractions and compartmentalize negative news that might sidetrack their team or cause their department to flounder. They keep their team focused and moving forward with a sense of urgency, regardless of the circumstances.

Command instinct. Great sales leaders establish firm command over their team by exercising the power their title and position entail. For example, they hold their team to a higher level of accountability. Seventy-five percent of high-performing sales managers agreed that their salespeople are consistently measured and held accountable against their quota, compared to 58% of underperforming sales managers. However, their authority is not autocratically administered as you might think. Rather, it is based upon establishing an environment where sales team members continually seek to prove themselves, thereby driving higher overall departmental performance. The leaders establish this culture using a “carrot and stick” psychological approach. Overachievers receive praise and public recognition, while underachievers are admonished or ostracized until they redeem themselves. In essence, the command instinct is responsible for creating the peer-pressure and attention-seeking environment that eliminates complacency.

Hiring ability. The ability to hire quality talent will determine the success or failure of the sales organization. Seventy-two percent of high performing sales managers rated the sales team they manage as excellent or above average, compared to 54% for underperforming sales managers. Conversely, 46% of underperforming sales managers rated their team as average or below average, while only 28% of high performing sales managers thought so. High-performing sales managers focus on hiring salespeople who are skillful builders of relationships, are persuasive, and have a reservoir of experience they use to control sales cycles.

Sales intuition. Sales is a mentorship-based profession, and a key differentiator of great sales leaders is their ability to dispense tactical sales advice and add value during customer meetings. While the average sales experience for both high-performing and underperforming sales managers was 17 years, high-performing sales managers estimated they have achieved their annual quota 88% of the time over the course of their career. Underperforming sales managers indicated they have achieved their quota 75% of the time. This suggests that the depth of a manager’s sales intuition—the practical knowledge gained from the experiences of participating in sales cycles and managing salespeople—is directly associated with their success.

Control orientation. Sales managers who closely monitor and strictly enforce a sales process are more likely to exceed their quotas, and the best sales leaders seek to control the daily behavior of their sales teams. Forty-three percent of high-performing sales managers responded that their sales process was closely monitored, strictly enforced, or automated, compared to 29% of underperforming sales managers. Forty-four percent of underperforming sales managers indicated they had a nonexistent or an informal structured sales process.

Coaching adaptability. Great sales leaders understand that there is a diversity of selling styles by which salespeople can achieve success. Therefore, they don’t employ a one-size-fits-all coaching style. Rather, they adapt their style to suit each individual. The fact that high-performing sales managers had a higher team effectiveness factor than underperforming teams supports these statements.

A team effectiveness factor is calculated by averaging total quota achievement across the number of salespeople on the team. For example, if a team of ten sales reps who each had $1 million quotas sold $8 million in total revenues, the team effectiveness factor would be 80% ($8 million of actual sales divided by $10 million of quota). High performing sales managers averaged an 81% team effectiveness factor, while underperforming sales managers averaged 55%. One explanation for this significant difference is that high-performing sales managers have a wider range of coaching adaptability.

It’s also important to note that high-performing sales managers had higher quota risk pool factors than underperforming sales managers. A sales manager’s quota risk pool factor is calculated by adding together all the quotas of the salespeople who report to the manager and dividing the sum by the manager’s quota. For example, a sales manager with a $10 million quota who manages ten salespeople with $2 million quotas would have a quota risk pool factor of two.

Strategic leadership. All sales leaders are battlefield commanders who must devise the organization’s sales strategy to defeat the competition. This requires plotting the best course of action to maximize revenue using the most cost-effective sales model. Great sales leaders possess the knowledge to correctly deploy field or inside salespeople, to segment the market into verticals, and to specialize sales teams by product or customer types when necessary. This helps explain why there was a 51% quota performance gap between high-performing and underperforming sales leaders last year. High-performing sales leaders reported an overall average annual quota attainment of 105% compared to 54% for underperforming sales managers.

The sales organization is unique and unlike any other department of a company. The best sales organizations have strong leaders who exercise control and establish the code of behavior that all team members must abide by. They employ their experiences to determine strategic direction and coach team members individually. Most importantly, they know how to keep the team on track and focused on winning.

You Really Can Change Your Reputation at Work

Do you ever feel that people have the wrong impression of you at work? Maybe you’ve been pegged as arrogant after you advocated for your project or as a pushover after a negotiation gone awry. How can you change others’ perceptions of you? Should you directly address the reputation you want to shake? Or should you focus your energy on changing your ways?

What the Experts Say

It can be frustrating when others don’t see us as we intend. “But we forget that we have so much more information about ourselves than other people do,” says Heidi Grant Halvorson, author of No One Understands You and What to Do About It. We also forget that nearly every action is open to multiple interpretations. Take the seemingly straightforward act of bringing someone a cup of coffee. You may intend it as a nice gesture but others might see it as the opening salvo in asking someone for a favor. Resist the urge to say someone’s understanding of the situation is mistaken, says Dorie Clark, author of Reinventing You and Stand Out. “A person’s perception may be different from what you feel is the truth, but it’s not necessarily wrong,” she says. “It’s real for them, and the onus is on you, not them, to work to change the dynamic.” Here’s how to change your reputation at work.

Be upfront about the issue

When you know you’ve made a poor impression, or you believe you are being unfairly branded, it can be useful to address the misperception head-on. If you think you may have offended a colleague, reach out to apologize. If you were late delivering two reports in a row, approach your manager to say you know it’s an issue and that it won’t happen again. “Naming the issue shows you are aware of it,” says Clark. It can also start the process of changing how you are perceived. Otherwise, “the negative association just keeps festering and strengthening in people’s minds,” she says. However, Grant Halvorson says, “You don’t always have to discuss the issue directly.” (See case #2 below). “But if there’s a sort of mea culpa involved, it’s often a good idea.”

Don’t get defensive

If you do address the misperception directly, make sure not to get angry or cast aspersions. “You can’t go into the conversation saying, ‘You know, I think from our last encounter, you see me like a jerk, and I’m not,’” says Grant Halvorson. “You’re basically accusing them of getting you wrong.” Instead, accept that they feel a certain way about you and apologize if necessary. Then pour your energy into building a standing that you think is more reflective of your actual self.

Look for opportunities to work together

Just saying you aren’t a pushover isn’t going to do it, nor is standing up for yourself once. “One time being nice is not enough to override an initial impression of you being arrogant,” says Grant Halvorson. You have to provide evidence to the contrary—the more often, the better. “Frequency is your friend,” she says. A smart way to achieve this, especially if you don’t regularly encounter the person you are trying to convince, is to volunteer to work with them. Not only do you have more opportunities to change their mind, the person is more motivated to soften their stance toward you. “When they have to work closely with you, it is in their self-interest to pay very close attention to you and who you are,” says Clark. Grant Halvorson agrees. “They think, ‘If I am going to succeed, I need you to work well with me,’ and that really gets people motivated” to open their minds, she says.

Go above and beyond

It can be tough to change people’s minds so when your reputation is on the line, “you have to overdeliver,” says Clark. If you have a reputation for showing up late to work, “getting into the office at 9:01 AM is a problem,” because you are proving people’s assumptions right. Instead, you need to get there at 8:45. If you believe you offended someone with an offhanded comment, you have to be especially vigilant about watching your tongue. And if your boss thinks you’re the meekest participant in meetings, you need to now offer up frequent, thoughtful contributions. “You have to recast yourself and perhaps play dramatically against type,” says Clark. “But over time, once people’s perceptions begin to shift, you can migrate back toward the center where it feels more comfortable.”

Find common ground

“Finding common ground gets the other person to start thinking of ‘us’ rather than ‘them,’” says Clark. “They will be far more receptive to listening to you and to taking in whatever you say.” The shared trait can be relatively inconsequential: Living in the same neighborhood, wearing the same brand of shoes, or being a dog lover. “People will sort of unconsciously re-categorize you” when they believe you both have something in common, says Grant Halvorson. “They’ll think, ‘we want the same things and we have the same goal.’ And we automatically have a much more positive attitude toward people that are in our ‘in’ group.”

If you don’t feel you are making much headway with someone, another strategy is to ask that person for advice. “The person usually feels flattered,” says Clark, “and it changes the dynamic because you’re making yourself vulnerable to them.”

Have patience

Don’t expect results overnight. “If you want to know how long it will take changing someone’s perception, Grant Halvorson follows this rule of thumb: “Longer than you want it to.” It depends of course on many factors, including how extreme the difference between the impression you gave and the impression you want to impart, and how many opportunities you have to make your case. “The stronger the impression, the longer it’s going to take to change,” she says. Clark says to give yourself a few months. But don’t let that discourage you. “Just think: If you begin now, you can begin to start turning the tide,” she says.

Principles to Remember:

Do:

Address the issue head on, especially if you were in the wrong.

If you want a more positive impression to stick in someone’s mind, you have to offer it up repeatedly.

Look for characteristics you share with the person. Common ground will help soften their stance.

Don’t:

Accuse the person of being wrong about you. Their perception is their perception, and it’s up to you to help “correct” it.

Avoid working with the person. The more you’re in front of them, the better.

Expect people to change their minds on a dime. Shifting someone’s perception often takes time.

Case study #1: Addressing the misperception with a mea culpa

Arvin Sahakian, a real estate broker, was rushing to finish a database project on deadline when a colleague called to ask if he could help him figure out a problem with Excel. Immersed in the project at hand, Arvin abruptly hung up the phone and rushed over to the colleague’s desk, where he wordlessly showed him how to fix the problem, pushed save, and walked back to his desk. “I wasn’t paying attention to how he would perceive the situation,” Arvin says. ”I was just trying to get him rolling so I could get back and continue doing my thing.”

A few days later, Arvin heard from another coworker that their colleague had assumed Arvin was annoyed by him, and that the colleague was now afraid to approach him to ask for more help. That afternoon, Arvin approached the colleague during a break and apologized for his brusque behavior, saying that he had simply been distracted and in a rush. “I told him to feel free to approach me anytime,” he says, suggesting that sending an email or an internal instant message would be the best way to get his attention in the future. “It really kind of cleared the air.”

The two had a very good working relationship from there on out. “Sure enough, our interactions after that worked fine,” says Arvin. “He’d ask me a question via email, and I would type back real quickly, ‘See you in 10 minutes.’ We kind of figured out how to communicate.”

Arvin, now a vice president for the online mortgage marketplace BeSmartee, says that the encounter made him much more conscious of how short and seemingly benign encounters might come across to colleagues. Even when we are distracted by our own pressures, “it’s important to remember we are all just people working with other people,” he says, “and maintaining healthy relationships with them matters.”

Case study #2: Giving 110%

Apryl DeLancey was working as a data insights manager at a large advertising agency when the new department head put her in charge of a major data project. But the transition to her new leadership position didn’t go smoothly. “There was a person who decided she didn’t like me for whatever reason,” says Apryl. “I would catch her rolling her eyes or shaking her head, or doing silly little things behind my back. I later found out she made sure to tell all of the new hires that I was incompetent and conceited.”

Apryl soon noticed that the members of her team weren’t giving her information she needed or meeting deadlines. She decided she wouldn’t get anywhere telling her detractors she was capable; she had to prove it by putting in 110%. “It was challenging, but I just stuck to my methods and did my work,” she says. “I kept doing my job and doing it well, and eventually I won over the team with my persistence and professionalism.”

In one instance, she partnered with one of the new members of the team on a small project. In the course of working closely together, the colleague — a good friend of the rumor spreader — could see that Apryl’s reputation as a poor worker wasn’t true. “She saw my work ethic up close and how I treated people and the job,” Apryl says. “And she apologized for making things difficult for me.”

“I’ve always believed if you do good work and you put good out there, good will come back to you,” she says. “I learned that if you do your job and be a leader, others will take note.”

September 10, 2015

How Israeli Startups Can Scale

Israel has been branded the “startup nation.” For good reason: A tiny country of only 8 million people — 0.1% of the world’s population — has more companies listed on the NASDAQ than any country in the world save the United States and China. Frequently cited as one of the world’s most vibrant innovation hubs, Israel boasts more startups per capita than any other country in the world.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that Israeli startups are struggling to scale. Only a handful of so-called unicorns — companies that have achieved a valuation of over $1 billion in the last 10 years — come from Israel, and only one Israeli firm, Teva, ranks in the world’s 500 largest companies by market capitalization. As a result, tech-sector employment has declined as a percent of the workforce, from 11% in 2006–2008 to 9% in 2013. That’s disappointing for a country with so much potential. But is all of that changing? Are Israeli companies on the verge of developing a repeatable playbook to scale their companies and become market leaders, not just acquisition fodder for the Silicon Valley giants?

We think so.

Why Is Israel So Entrepreneurial?

Israel is home to one of the most vibrant tech startup clusters in the world — why? Many explanations have been offered. Research has highlighted the early role of military R&D, which, much like in the U.S., helped to create the nation’s tech industry. (At nearly 4% of GDP, Israel spends more on R&D — public and private combined — than any nation in the world.) The government also took more direct measures to boost the tech sector. In the 1990s it subsidized venture capital, incubators, university R&D, and technology transfer programs.

Daniel Senor and Saul Singer offer additional explanations in their book, Start-Up Nation. Somewhat counterintuitively, they argue that mandatory military service helps build entrepreneurial culture. They write, “You have minimal guidance from the top and are expected to improvise, even if this means breaking some rules.” Senor and Singer also cite immigration policy and a culture that tolerates risk-taking and failure as contributing to Israel’s startup success.

Good relations with the U.S., too, have undoubtedly helped, connecting Israeli entrepreneurs to investors and a large market.

The final reason for Israel’s entrepreneurial dynamism is based on the logic of innovation clusters: Early success breeds continued success. Once enough technologists and startups are concentrated in one place, that place becomes a magnet for venture capitalists and more talent. Israel’s early embrace of tech and VC continues to pay off.

Decades ago, the thesis of Yossi Vardi, a prolific technology entrepreneur who has invested in 75 Israeli startups, was that Israeli entrepreneurs should seek quick exit opportunities through global corporations interested in buying a window into Israeli talent and technology. Today, this thesis is less relevant. For the first time in history there are Israeli companies scaling up successfully as global market leaders, and the ecosystem is evolving to support them. Indeed, the pattern of scaling seems to be changing meaningfully in recent years. In 2014, for example, 18 IPOs raised a record-breaking $9.8 billion, compared to just $1.2 billion in 2013.

So how do Israeli ventures scale up? What are the challenges and lessons of scaling up? To answer these questions, we built a database of 112 Israeli companies founded between 1996 and 2013 that have met or exceeded $20 million in revenue. We selected this benchmark because it reflects the phase in which companies have proven product viability, achieved initial product/market fit, and are now expanding sales and growing more complex operations. We also interviewed over two dozen Israeli entrepreneurs and the investors from these companies — the leading thinkers in the region — to determine the playbook that these startups are executing in order to scale.

Here’s what the data say about Israeli startups:

They’re Israeli-run but with global footprints. Eighty-two percent have global offices, and yet 91% are still run by Israeli CEOs, as opposed to foreign executives hired from the outside.

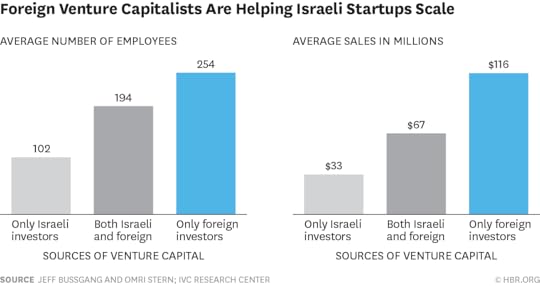

American VCs are critical. Ninety-one percent of the firms have received funding from foreign (mainly American) VCs.

The founders have started companies before. Sixty-three percent of startups currently scaling up are run by Israeli entrepreneurs with prior founding experience.

This evolving model is being supported and encouraged by the local Israeli VCs. According to Izhar Shay, a general partner at Canaan Partners, “The investment community has matured to recognize they need to plan for scale. They are seeking to build companies so that they are attractive to late-stage funds.” And the late-stage global funds are swarming in, from Accel to KKR to Li Kai-Shing’s Horizon Ventures.

This article outlines some of these patterns, seeks to characterize them, and draws out patterns in the data.

Pack Your Bags Early.

Despite hosting a rich startup ecosystem, Israel is simply too small a country for entrepreneurs seeking to build big companies. As a result, Israeli entrepreneurs need to begin immediately thinking outside of Israel since their primary market is often the U.S. The common approach is to incubate the business locally in Israel with a small development team, prove early product/market fit, and then build a sales and marketing organization abroad, usually in the U.S. In the old model of Israeli startups, many Israeli executive teams would hire a vice president of sales in the U.S. to assist with the local go-to-market approach. More recently, Israeli founders are themselves moving to the U.S. to build the satellite office and to personally oversee the recruitment and management of American executives who can lead the sales and marketing efforts.

However, waiting to move to the U.S. until the late-stage go-to-market phase may be too late. All of the risks inherent in launching a startup are exacerbated by the geographic distance between Israel and the U.S. Hiring talent and gathering customer feedback are even harder when teams are so physically far apart, and this separation can make it harder to build culture, forge partnerships, and raise capital.

So how early should the founders pack their bags and ship out to the U.S.? Our analysis and interviews suggest the prevailing wisdom has shifted toward a simple answer: as early as possible. Although the technical team often remains in Israel, many of the executives interviewed recommend departing for the U.S. as early as a year or two after founding. A move allows the business to get close to the customer, learn their pain points, and adapt accordingly. Understanding the market and establishing product/market fit is a critical seed-stage milestone.

When Udi Mokady and Alon Cohen launched CyberArk — the darling of the cybersecurity industry, with a market capitalization of nearly $2 billion — the founders abandoned the local strategy early on. “We began selling to local Israeli companies but had a strong feeling we were developing a product and go-to-market strategy that was missing the larger opportunity,” said Mokady. As soon as CyberArk raised Series A funding, they set up a U.S. headquarters, in Massachusetts, to immerse the team in the American market. “At the time, moving close to the market was not a given, and venture capitalists did not have a clear playbook. Nowadays the argument is very clear.”

Similarly, when Yaron Samid launched BillGuard, his team debated whether to build an enterprise or a consumer company. One-and-a-half years after founding the company, Yaron moved to New York and discovered that consumers, rather than banks, were the primary customer of BillGuard’s service, which helps customers identify fraudulent credit card charges. With the development team based in Israel, Samid shuttles between New York and Tel Aviv, where he shares weekly insights garnered from conversations with partners, consumers, and investors in the market. Viewing this as the typical challenge of running a global company, Samid believes there is no substitute for the learning that comes from being close to the market.

The second reason to move early is to hire the absolute best sales and marketing talent. Again and again, the most challenging issue we heard about from entrepreneurs and investors is finding and retaining exceptional talent, a problem exacerbated by geographical and cultural distance. According to Modi Rosen, general partner of Magma Ventures, “The challenge of scaling is primarily in hiring for the sales and marketing front. Having the founder [locally] present for this process can be the difference between success and failure.” Companies should strengthen the Israeli management team with local talent who understand how to define the market, how to sell into it, and how to gather feedback. Furthermore, companies need particular executives to serve as the primary liaison between the sales and marketing team in the U.S. and the development team in Israel. There are many Israeli professionals who have worked in the U.S. and have gained management experience at large organizations such as Google, Microsoft, and Amazon. There are also American executives who have experience working with startups with R&D in India, China, and Israel. Both cohorts can bridge cultural and geographical gaps.

In CyberArk’s case, Mokady admits the team faced major challenges in hiring talented and seasoned American executives. “We had a rough start,” he says. “As an unknown Israeli company breaking in to the U.S. market, we were not able to attract A-rated sales and marketing professionals. It took some time to gain momentum and learn how to attract local talent.”

One of the key lessons CyberArk learned is to partner with VCs in order to source top talent. Mokady believes that partnering with a Boston-based VC would have helped CyberArk address its talent problems more effectively because the VC would have vouched for the company. With that said, the founding team had big dreams of becoming a global company from the beginning. Although their investors were not local, CyberArk still benefitted by partnering with foreign VCs that helped them make the leap from Israel to the U.S.

Think Bigger.

This takeaway surprised us. After all, Israeli entrepreneurs are known to be tenacious and eager to tackle complex technological and entrepreneurial challenges. However, in our interviews with Israeli venture capitalists, we learned that around the board room, Israeli entrepreneurs tend to become overly preoccupied with the product and core technology. This fixation generates a short-term view on the potential of the venture to expand beyond the immediate product line. Of course, almost all entrepreneurs are preoccupied with near-term priorities, but our interviews uncovered a pattern of Israeli companies putting too much focus on the product at the expense of building a broad vision for growth, even after achieving product/market fit.

Scaling up begins with thinking about how you build a bigger story and a bigger vision once the company is expanding. Alan Feld, cofounder and managing partner of Vintage Partners, cautions Israeli entrepreneurs not to define their product category too narrowly. “The big idea is to think as a potential industry leader rather than a one-product company. Think of where you want to be in five years and begin building a product pipeline to get there.” For Netanel Oded, of Israel’s National Economic Council, the critique is more poignant: “In Israel, nobody is saying ‘I’m going to completely disrupt transportation.’ Israeli entrepreneurs are first and foremost focused on applying technology to create a business, not necessarily on disrupting big markets through the use of technology.” This subtle difference risks limiting the scope of the opportunities Israeli entrepreneurs are chasing.