Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1254

September 4, 2015

4 Reasons Retail Jobs Are About to Get Better

There’s widespread agreement that stagnant wages are a big problem in the United States. Which industry could really help do something about it? Retail.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the two largest occupations in the United States are retail salesperson and cashier. In 2014, their median hourly wages were $10.30 and $9.20, respectively. Both are below the poverty threshold for a family of four, even for someone working full-time.

But if you are one of those workers, it’s hard to even know for sure whether you do work full-time. Retail employees typically receive their work schedules one or two weeks in advance and even those schedules can change at the last minute. As a result, workers do not know when they will work and how much they will make from one week to next. Such unpredictable schedules make it harder for them to hold on to a second job or take care of their families.

A common misconception is that this is okay because retail jobs are mainly for high school or college kids looking for supplemental income. Not so. In 2014, the median age of a retail salesperson was 35. The median age of a cashier was 27. These aren’t kids looking for extra cash; these are people who depend on their jobs to support themselves and their families.

Why then do I say that retail is an industry that can help improve stagnant wages? Because improving retail jobs — which, of course, includes increasing wages — not only would help the workers; it can also help retailers and their customers. That is, it doesn’t at all have to be a concession. It can and should be a win-win-win.

If retailers want to thrive by offering better jobs, they will need to change their operations strategy from one that uses people as interchangeable parts to one that is human-centered. This is the equivalent of changing from Henry Ford’s assembly line, which depended very little on empowered, motivated, well-trained employees, to the Toyota Production System, which only works when empowered, well-trained employees constantly identify and solve problems and improve performance.

As we all know by now, Toyota’s human-centered operations strategy allowed the company to produce higher-quality cars at lower costs. In my research, I found that the same approach, which I call the good jobs strategy, allows retailers to provide better customer service at lower prices. Other researchers have made similar findings in industries ranging from steel to health care.

Transforming any company — retail or otherwise — into a good jobs strategy company requires a lot of changes to operations and will likely take time and great managerial competence. The good jobs strategy involves investing in people and making a set of operational choices. It concerns how many products and services a company will offer, the balance of job standardization and empowerment, the allocation of work among employees, staffing levels, and how employees will engage in continuous improvement. It’s a system that needs to be implemented together. That’s hard to do, but hard doesn’t mean impossible.

For retailers, now is the time to act. The competitive environment is increasing the benefits of following a good jobs strategy:

Bricks-and-mortar retailers need to create a better in-store experience. With e-commerce expected to grow more quickly than brick-and-mortar retailing, bricks-and-mortar retailers will need to give their customers more compelling reasons to shop at their stores. Low prices won’t be enough anymore; Amazon or someone else on the internet can match and probably beat your price. Those compelling reasons to come to a real store include in-stock merchandise and friendly, knowledgeable employees who are empowered and have the time to help customers. Of course, you also have to keep your store clean and appealing. But what I found in my research is that a retailer with a human-centered operations strategy can do it all.

Omni-channel retail is increasing operational demands at the store level. When customers reserve products online to pick up a few hours later, they use that store’s inventory data. Those data had better be accurate or a lot of customers will be plenty annoyed. That kind of accuracy is hard to maintain, but it’s not impossible. What it requires is not better software so much as better store operations. On top of all that, some companies are now shipping products directly from stores to customers. So store employees now also have to take care of internet orders. Good, human-centered, in-store operations will make that a great service; not-so-good operations will make it a nightmare.

Cities are raising the minimum wage, and Congress may force companies to give workers better schedules. Some cities have raised their minimum wage to $15. Consequently, unless companies find a way to increase the contribution of their employees, they will have to raise their prices, degrade their service, or just accept lower profits. Meanwhile, the recently introduced Schedules That Work Act, if approved by Congress, will force companies to provide their employees with more stable schedules. Again, that’s something that companies with a good jobs strategy already do.

Investors are on the lookout for more sustainable companies. There is growing evidence that companies with business models based on offering good jobs do better than their competitors. Some investment firms, such as Parnassus, have funds that focus on companies with great workplaces. Apart from such specialists, the amount of U.S.-domicile assets under management for investors who care about companies’ long-term competitive returns and societal impact is estimated to be $6.57 trillion.

As you can see, the times are calling for retailers to adopt a good jobs strategy. Just as automobile manufacturing was a great setting for the Toyota Product System revolution, retail is a great setting for the good jobs revolution.

The Powerful Effect of Noticing Good Things at Work

Over the course of a typical workday, negative and positive things inevitably happen to you. If you’re like most people, you tend to focus mainly, or even exclusively, on negative experiences. They’re what you ruminate over, what you talk to your friend about as you’re driving home, what you discuss with your partner at night. It sometimes feels good to talk about the negatives — it feels therapeutic.

If someone were to tell you to focus only on the positive experiences in your day, you might be annoyed. People tend to associate Pollyanna-type positivity with inexperienced managers trying to squeeze a little more work out of frontline employees, or with the “keep smiling” wall posters in the call center.

What most people don’t realize is that positive experiences — even small ones — provide you with valuable resources that can be used to reduce stress, including physical symptoms such as headaches or muscle tension. They make it easier for you to detach yourself from work at the end of the day.

We learned from our research that thinking about positive events in a systematic way can be healthy. We suggest that instead of ruminating about negative things, you try to “savor” — relive, enjoy, and share — the positive events of your day.

For most people, this doesn’t come naturally. Evolution and the survival imperative have attuned human beings to pay careful attention to all things negative; in addition, people quickly become so accustomed to positives in their environments that they hardly notice them. But a simple intervention can help overcome both tendencies.

Consider an experiment we conducted to study the workplace effect of what’s known as the “three good things” intervention. This intervention has been shown to improve mood among people who are mildly depressed, but we wanted to know whether it would also relieve stress for healthy workers.

Our team, which included Winny Shen of the University of South Florida, Eugene Kim of Georgia Tech, and Amanda J. Koch of Human Resources Research Organization, worked with employees of outpatient family-practice clinics (nurses, assistants, receptionists, and such). We asked participants — who had no idea what our research question was — to log onto a web site at the end of their work day and complete a “survey.” The survey asked them to spend five to 10 minutes writing about events large or small, personal or work-related, that had gone “really well” that day — and to explain why those things had gone well.

The responses ranged from reports of coworkers’ bringing in delicious food, to the mere fact that it was Friday, to thoughtful stories about interactions with coworkers or patients that made people feel good about themselves. For example, one nurse wrote that “a doctor gave me a compliment today.” Why? “Because I knew exactly what to do in an emergency situation, and I helped a patient who was having a seizure.”

After three weeks, stress levels and mental and physical complaints declined by small but significant amounts. Moreover, on days when participants focused on good things, they were better able to switch off stressful job-related thoughts in the evening at home.

This simple practice — writing about three good things that happened — creates a real shift in what people think about, and can change how they perceive their work lives. It can also create a feedback loop that enhances its impact: we believe that people who reflect on good things that happened during the day are more likely to share those things with family and friends. Sharing positive events with others creates connections between people and bonds them with one another, further reducing evening stress. Ultimately, this also improves sleep, which our ongoing research suggests leads to greater alertness and better mood — which in turn leads to more positive things happening the next day.

Other benefits of this easy-to-implement and inexpensive exercise include potential increases in creativity. Creative thinking and innovation are enhanced by positive emotions, especially feelings of contentment and joy. Growth, development, and forward thinking arise from positive emotions.

Complaining about your boss and coworkers is common, and can even be valuable if it helps you feel heard and understood. But there are downsides to expressing negativity. The research literature is unclear on whether focusing on negative events actually provides relief from stress. And in a workplace context, negative comments can spread through the organization via social contagion, causing further damage.

It is unlikely that people will stop talking about negative experiences at work. It is natural. But intentionally focusing on positive events can provide balance. We don’t advocate putting up happy posters, but companies can take steps to intelligently help people notice and share positive experiences. For example, how about starting a meeting with a review of what has gone well recently, rather than immediately jumping to what needs to be improved?

What’s great about this exercise, however, is the power it gives to each of us on a daily basis. Before turning on the radio or getting on a call during your homeward commute, take a moment to reflect on the good things that happened at work. Doing so can help you capitalize on the small, naturally occurring flow of daily positive events — a ubiquitous but too-often-ignored source of strength and well-being.

Why Sex and Violence Don’t Sell

Early on in the AMC series “Mad Men,” a young, ambitious Peggy Olson defends her ad idea to Don Draper, assuring him, “Sex sells.” He barely hides his disappointment before brushing this aside, “Says who? Just so you know, the people who talk that way think that monkeys can do this.”

Don was on to something. New research suggests that sex, in fact, does not sell—and neither does violence. A recent meta-study by Robert Lull and Brad Bushman of The Ohio State University, published in the journal Psychological Bulletin, looked at 53 experiments to analyze the effects of sexual and violent media and ad content on people’s memory, attitudes, and buying intentions. Contrary to the old adage, they found that, on all three measures, sex and violence weren’t effective at selling products, whether they characterized the program the ad was interrupting, or the content of the ad itself.

So why then does it seem like we’re inundated with these kinds of images on a daily basis? Part of the answer is that they simply get our attention. According to the authors, this goes back to evolutionary theory. Sexual and violent cues have been associated with reproduction and survival, and so we’re hardwired to pay attention to them. This seems to play out in what we choose to watch. Nearly half of the most successful shows, films, and video games from the last five years were rated for violence, and over a quarter were rated for sex. This isn’t lost on advertisers.

These programs also tend to attract the highly coveted 18-to-34-year-old demographic, known for having the most disposable income and believed to be more easily influenced by ads than older adults with more entrenched buying habits and brand loyalty. Combine these two factors—audience size and age—and it’s not surprising that companies may choose ads and shows that contain sex or violence.

There’s a problem with this reasoning, however. The authors explain that reach and attention aren’t great measures for advertising effectiveness (research has previously shown that large audiences don’t always yield the best ROI; the Super Bowl is a prime example). These are only the first two stages of eight: 1) you’re exposed to the ad, 2) you pay attention to it, 3) you understand the message, 4) you evaluate it favorably or unfavorably, 5) you store it to long-term memory, 6) you remember it later, when 7) you have to decide between different brands, and 8) you buy or don’t buy the advertised product.

Lull and Bushman’s meta-study focused on how sex and violence affected the latter stages of the model, those that represent people’s brand attitudes, brand memory, and buying intentions. And after combing through dozens of studies (involving nearly 8,500 total participants) on these advertising outcomes, they concluded: “Brands advertised in violent contexts will be remembered less often, evaluated less favorably, and less likely to be purchased than brands advertised in nonviolent media.” The results weren’t as significant when it came to programs that contained sex, but while it may not be as detrimental as advertising in violent media, they saw no positive effects, suggesting that “it does not appear to be a successful strategy either.”

The main reason for this, they say, is that titillating images and violent cues distract from the brand and product that the ad is trying to sell. “Yes, violence and sex naturally grab our attention, but the problem is that humans have limited attentional capacity,” Bushman explained to me. “Because violence and sex are so emotionally arousing, they take a lot of that capacity and leave little over for the brands being advertised. So you might notice the violence or sex in an ad but not remember the laundry detergent or whatever they were trying to sell.”

Yet while the evidence supports this idea, the researchers acknowledge that future research needs to be done to directly measure the underlying mechanisms of attention and arousal, and how they influence advertising outcomes when we’re exposed to sex and violence.

A few other interesting findings stood out in the data. The more sexually explicit the content, the worse the impact on advertising outcomes. Older people were more put off by violence and sex than younger people. And brand memory impairments were larger in studies that had more men. They also coded for publication year and observed that the detrimental effects of violence and sex on advertising effectiveness seemed to get smaller and smaller over time. “One possible explanation, and more research needs to be done to know for sure, is that people are just becoming desensitized to violence and sex,” Bushman said.

This all raises the question: If sex and violence don’t lead to better advertising outcomes, what does? The researchers didn’t look at other devices like humor or nostalgia. But they did find one possible exception to their overall finding—if an ad with sexual overtones is embedded in a sexual program, and likewise with violent ads in violent programs, they saw small positive effects. This is called program/advertisement congruity. However, this only appeared in four of the 53 studies they looked at, so Bushman said he’s not as confident in the finding. “I think the simplest explanation for this is priming, or how seeing one stimulus can prime or activate related stimuli,” Bushman told me. “If you see the word ‘bread,’ you have a faster response to the word ‘butter’ than you might to the word ‘doctor.’ Similarly, if people see a program containing violence and sex and then an ad with the same features, those become more accessible in memory.”

Perhaps it’s time to update the conventional wisdom about how profitable sex and violence really are. The researchers suggest that advertisers at least take this into account. “We hope that rather than basing decisions on intuition or common sense, people will turn to science,” Bushman said. “And the scientific evidence from our study is pretty clear.” Sorry to say it, Peggy, but it seems like Don was right about this one.

The Dawning of the Age of Flex Labor

The prevailing paradigm of people working as full-time employees for a single organization has outlived its usefulness. It produces excess volatility over the business cycle, resulting in measurable economic costs — both to people and to the companies they work for.

Our vision is straightforward: most people will become independent contractors who have the flexibility to work part-time for several organizations at the same time, or do a series of short full-time gigs with different companies over the course of a year. Companies will maintain only a minimal full-time staff of executives, key managers, and professionals and bring in the rest of the required talent as needed in a targeted, flexible, and deliberate way.

There are two reasons such a flexible work system is now plausible. The first is societal values. Work-life balance and family-friendly scheduling are much more important to today’s workers, and companies are increasingly willing to accommodate them. The second is technology. Advances in the last five years have greatly improved the ease with which people can work and collaborate remotely and companies and contract workers can find each other. These include:

The relative ubiquity of broadband connections

Collaboration tools like Dropbox and Evernote

Continued improvements to services like Skype and Google Hangouts.

Software-driven marketplaces such as HourlyNerd, UpCounsel, and Behance that are facilitating the fast and accurate match of the supply and demand for high-quality, experienced talent

As a result, we expect to see America’s leading companies leveraging what Mark Cuban calls the “spot market for intellect” for an increasing share of their needs. This is already happening in some places. Many complex projects on HourlyNerd, for example, are posted, negotiated, and closed within 24 to 48 hours. Recent examples include projects at firms such as General Electric, Staples, and dozens of other Fortune 1000 enterprises that span functional areas from marketing to strategy to human resources to operations. Due to very low marginal costs of delivery, these services are available to even small and medium-size businesses.

The application in the white-collar market of the seasonal worker concept — longstanding in both retail and agriculture — has clear advantages over the prevailing full-time employee model. Workers, employers, and society stand to benefit tremendously from breaking the cycle of hiring people in boom times and releasing them fully during economic slowdowns or contractions.

Workers. Many more people who today would be laid off from full-time positions when a recession hit and then would be totally unemployed for some period of time will find it easier to remain at least 80% employed during a downturn. In addition, the burden of the following would be reduced or eliminated:

The significant search and learning costs often required to land a new job.

Higher out-of-pocket expenses that result when a family loses employer-provided, health care coverage.

The increased difficulty of saving for retirement from continually changing benefits programs.

Sudden increases in debt that often occur during unplanned periods of lost or reduced income.

The unfair reputational costs that result from “resume gaps” due to unemployment.

Employers. For firms, the cost of locating, vetting, and onboarding full-time employees is very high: as much as 150% of annual salary for a management position, according to the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment at the University of California at Berkeley. Even assuming these costs are, say, 50% lower for lower-level positions, spending 75% of an employee’s annual salary just to hire her or him is extremely expensive.

Separately, the bureaucracy and approvals required to place a full-time job applicant within a Fortune 1000 company can often take three to six months, meaning that companies may ramp up hiring too slowly to capitalize on commercial opportunities. In addition, hiring and firing are subject to the “bullwhip effect”: Due to a lack of information about the true state of the present and the future, companies constantly lag in expanding or shrinking their workforces during the course of the business cycle. By making adjustments easier, the flexible work system allows firms to adjust faster and more accurately.

Society. The need for —and therefore the cost of — safety-net benefits to help people who lose their jobs (e.g., unemployment benefits and Medicaid) would decline. What is more, a flexible work system would create economic opportunities for people ordinarily locked out of elite, white-collar jobs (e.g., primary child-care givers, students, and those caring for sick relatives). This will increase the overall size of the workforce and help create a broader, more diverse talent pool.

Introducing an intermediate-worker category between employees and independent contractors is the final missing puzzle piece to making this vision a reality. The United States should follow the lead of countries like Canada, Germany, and Spain in creating a “third way” — a dependent contractor category that removes the rigidity of W-2 status and adds more clarity and structure to the relative Wild West of 1099. Fortunately, we’ve solved far more complex problems. As freelance work consumes an ever-increasing fraction of white-collar employment, the Internal Revenue Service and U.S. Department of Labor will have no choice but to act. Their action will be the keystone of a model that’s more attractive for all parties.

Flexible work is an idea whose time has come.

Many CEOs Aren’t Breakthrough Innovators (and That’s OK)

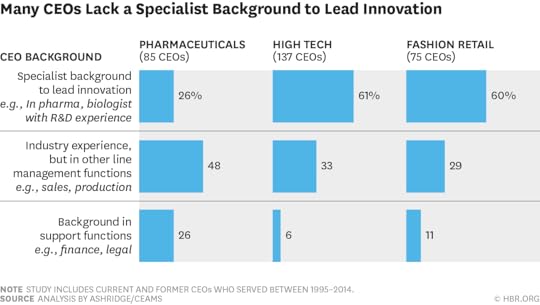

Innovation is widely regarded as important to long-term business performance. However, CEOs often don’t have the career background and education that would equip them to personally lead the process of new product development. We’ve found that CEOs of big pharmaceutical companies, for example, are more likely to have a background as company lawyers, salespeople, or finance managers, than one in medicine or pharmaceutical R&D.

So, to achieve higher performance, should company boards and investors choose CEOs with the expertise that would better qualify them to lead innovation? Our research suggests that in certain industries—where breakthrough innovation is critical for growth—they should. But in many sectors, breakthrough innovation is often not as important to performance as it’s perhaps made out to be.

We found that, for pharmaceutical industry CEOs, there is a statistically significant relationship between a CEO’s specialist background and the firm’s performance. A specialist background to lead innovation is worth a 4% better shareholder return every year for 20 years, compared to other pharma CEOs in our sample.

About the Research

We looked at the background and performance data of 297 CEOs leading the largest companies in three different industries which are widely regarded as innovative: pharmaceuticals, high-tech, and fashion retail. The data captured a 20-year period, from 1995 to 2014. (This work builds on earlier research into CEO qualifications.)

We hypothesized that to lead innovation and improve performance (which we measured by shareholder returns), CEOs needed to have substantial experience working in business functions responsible for creating the customer offer. This would mean, for example, working in R&D to lead pharma innovation, new product development for high tech, and product design or merchandising for fashion retail. And in pharma or tech, CEOs should have also had a relevant formal education such as in medicine or science for pharma, and in math, engineering, or computer science for tech.

We measured CEOs’ qualifications along these dimensions on the basis of an extensive search, going back many years, of press and company publications. Assessing CEOs’ specialist qualifications required some judgment; some medical doctors, for example, went into pharma sales not R&D. However, classifications were mostly clear.

To measure a CEO’s contribution to creating shareholder value, we then looked at the difference, during the CEO’s tenure, between a company’s total shareholder return (in percent) and that of its industry peers. (This measure was also recently used to calculate HBR’s 100 best performing CEOs in the world.) We used the measure to calculate the impact the CEOs in our sample had, during their tenure, on their companies’ average annual performance over the twenty-year period of our study.

Of course, there are other possible explanations for this. For example, the companies that had technically qualified CEOs and performed better were often relatively smaller, which suggests that the complexity of large pharmaceutical companies may be a problem in driving R&D. Overall, it is a messy picture. There was no strong association between CEO background and firm performance in high-tech and fashion retail. And across the three industries, there were plenty of CEOs well qualified to lead innovation whose firms generated poor shareholder returns, and vice versa.

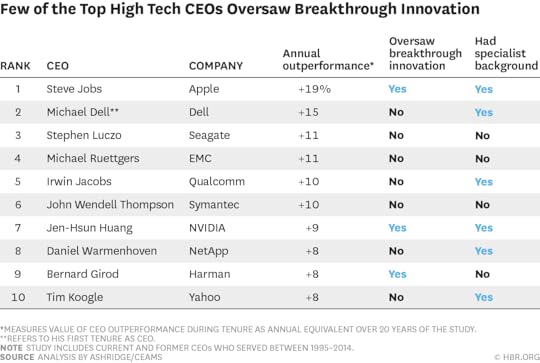

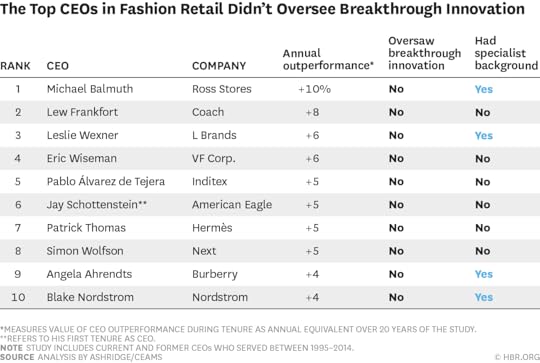

We decided to look at case histories of the 10 top-performing CEOs in pharma, high-tech, and fashion retail from our sample to understand people’s stories. (We focused on CEOs with at least five years in office.) Among these 30 CEOs, only nine (six in pharma, three in high-tech) achieved their strong performance while overseeing breakthrough innovation. For the rest, we found that other factors besides innovation drove strong shareholder returns.

Pharmaceuticals

In the pharmaceutical industry, short patent lives for prescription drugs mean companies must continually look for new drugs to fill their pipelines. And these often have to be significantly better than what’s on the market (in other words, breakthroughs) due to the high cost of R&D. Six of our top 10 pharma CEOs lead companies where shareholder value was directly tied to the development and launch of important new drugs during their tenure—and five of them did have a career background in pharmaceutical R&D and a relevant scientific or medical education.

The other CEOs in our sample didn’t directly oversee breakthrough innovation. Because the growth of Celgene under CEO John Jackson was tied to the repurposing of thalidomide (an old and powerful, but highly dangerous drug) to safely treat new diseases, we did not count this as a breakthrough (though it was a tough call). The three other CEO success stories, however, more clearly did not involve breakthrough innovation. For example, Brian McNamee of CSL Ltd made a series of global acquisitions to turn Australia’s small Commonwealth Serum Laboratories into the global leader in plasma products. And Michael Pearson, the head of Valeant, boosted the company’s performance by aggressively cutting R&D spend, taking on debt to finance acquisitions, and moving the company outside of U.S. tax jurisdiction. Meanwhile, Lars Sorensen was CEO of Novo Nordisk as the company’s core market, diabetes care, experienced growth beyond expectations.

High Tech

In high tech, two of the top 10 CEOs created particularly high value thanks to breakthrough innovations: Apple’s development of the iPhone and NVIDIA’s development of the graphic processing unit. Both Steve Jobs at Apple and Jen Hsun Huang at Nvidia were able to draw on deep personal experience in product development to play a key role in driving these innovations. But technical background isn’t an absolute requirement. For instance, we considered Harman International’s development of the MOST (media oriented system transport) system, under CEO Bernard Girod, as a breakthrough (it established its strong position in the infotainment market), but Girod’s career background was largely in planning and finance.

Breakthrough innovations in high tech certainly have a powerful impact on performance, but they are quite rare. Most of the tech firms in our sample achieved a breakthrough innovation early in their corporate lives. But seven of our top 10 tech CEOs relied on other sources of value creation over the period we examined. For example, Qualcomm’s CDMA mobile technology was a breakthrough that led to its IPO in 1991. But it was exploiting this technology’s growth potential some years later that put Irwin Jacobs in our top 10 tech CEOs between 1995 and 2014.

Most of our top tech CEOs created value by rolling out earlier breakthrough innovations in a newly high-growth market. For example, Michael Dell developed his breakthrough model of direct-selling personal computers in the 1980s. But it was the following decade’s internet boom that made this approach attractive and gave Dell a second burst of growth. And others, like Stephen Luczo at Seagate, Michael Ruttgers at EMC, and Daniel Warmenhoven at NetApp, took off as the internet boom led to dramatic growth in the demand for computer storage.

Even though (comparatively) few of our top tech CEOs achieved their outperformance from a breakthrough innovation occurring between 1995-2014, the ability to keep up with the pace of high-tech innovation was crucial – and having a sufficient technical background matters. For example, Terry Semel, who succeeded Tim Koogle as CEO of Yahoo in 2001, had a media marketing background at Warner Brothers. Clever brand positioning and offering media services helped him sustain Yahoo’s success for a while. When Google came in with its innovations in internet search and advertising technology, Semel made acquisitions rather than relying on internal development (Inktomi for search; Overture for search keyword advertising). But these products still needed rapid further development and integration to be competitive. Without a tech education or high-tech product development experience, Semel was not well placed to lead this process. Google powered through to an unchallengeable lead.

Fashion Retail

In fashion retail, what constitutes a breakthrough innovation may be more subjective. But based on our research, we consider that not a single one of the CEOs on our top 10 list got there because of a breakthrough innovation during our period of study. Most often, what led to their success was a strategy of growing the number of stores in an existing fashion chain.

One example is Ross Stores: It created an innovative off-price fashion retail format in 1982, which led to its IPO in 1985. But it was continuing to roll out this concept by opening more stores that helped it go from a $1.4 billion company in 1995 to an $11 billion dollar company in 2014. (It’s why CEO Michael Balmuth is the no. 1 in our fashion retail sample.) It was a similar story with Zara. Its key innovation was from the 1980s: a fast-fashion design, production, and replenishment process that brought more new merchandise into stores, faster. But what made the company’s performance soar under CEO Pablo Alvarez de Tejera was its rapid global expansion between 2005 and 2015.

Of course, there are other ways, aside from store expansion, to sustain high returns in fashion retail, such as global sourcing, growing e-commerce, improving stock management etc. Specialist background is arguably not so important for pulling some of these levers—any good analytically oriented general manager, with some level of retail industry expertise, can find ways to add value.

But there are also top performers who did have specialist background working in fashion design and merchandising—and one could say this was key to their success. For example, Burberry CEO Angela Ahrendts studied fashion design and merchandising and gained deep experience working in these functions at Donna Karan and Liz Claiborne. After inheriting a struggling brand at Burberry, she quickly created a single global design team, focused the product range, and introduced faster merchandising processes. The changes she made did not necessarily lead to breakthrough innovation (the core of the brand is still the trench coat, which was first designed for the British War Office in 1901), but she was able to revitalize the Burberry brand quickly. This is important because when you reposition a fashion offer, there is little room for testing and learning before you commit. Extensive prior experience in fashion design and merchandising help ensure more successful bet.

While the value of having a CEO with specialist experience deserves more research, we find that to drive innovation, CEO experience in product development is important. But a little innovation goes a surprisingly long way. In the pharma industry, the patent-based business model makes breakthrough innovation critical for achieving high returns. We found evidence that CEOs with the relevant technical education and career backgrounds were more likely to oversee breakthrough R&D. However, only about 28% of pharma CEOs have such a background. To us, this seems odd, but it may help explain why the largest pharmaceutical companies – those least likely to have CEOs with technical experience and most likely to have problems with R&D productivity – are outsourcing more R&D to small VC-backed firms, whose managers do have the expertise to lead the search for new drugs.

In high-tech and fashion retail, more CEOs have a product development background than in pharma (around 60% in both industries), but we found that breakthrough innovation for public companies in these industries is rare; most happen pre-IPO. Instead, public companies are mostly exploiting and improving upon past breakthroughs, not coming up with new ones. In this context, CEOs with technical backgrounds don’t necessarily achieve higher shareholder returns than those without. But with rapidly changing technologies and consumer preferences, having the right specialist experience can help CEOs keep their companies and their offerings relevant.

September 3, 2015

Stress Can Be a Good Thing If You Know How to Use It

With all the media and medical attention on stress and its negative health impacts, it is easy to reach the conclusion that stress is irredeemably bad—something to be avoided as much as possible.

We have a different perspective. We believe that pursuing a “stress-free” life often causes more stress down the line—problems compound, and by failing to face our most intense challenges we never overcome them. Think about a time when you experienced substantial personal or professional growth, or a time when you performed at your highest level, such as finishing a race, building a business, or raising a child. What was it that motivated and fueled you to grow, learn, and improve during these times? We are willing to bet that those times invariably involved some stress or struggle.

Stress has many wonderful attributes. It reminds us that we care; it connects us directly with the most challenging and important aspects of our lives. We aren’t suggesting that sustained stress does not take a toll, only that it can bring unexpected benefits, too, in the form of personal growth. Combining our years of experience conducting leadership seminars and teaching meditation and martial arts (Tom) and exploring empirical research in the area of psychology (Alia) we have found that individuals who adopt a “stress is enhancing” mindset in their lives show greater work performance and fewer negative health symptoms than those who adopt a “stress-is-debilitating” lens. Drawing on our work and research with executives, students, Navy SEALs and professional athletes, we have devised a three-step approach to responding to pressure that we believe can help you harness the creative power of stress while minimizing its deleterious effects.

Step One: See It

The first step to transforming your response to stress is to “see” your stress. Rather than denying it, or dwelling upon it, we recommend simply naming or labeling the stress you are facing. For example, you might simply say to yourself: “I’m stressed about my son failing school.” Or “I’m stressed about our year-end numbers.” Or “I’m stressed about my husband’s recent health diagnosis.”

Neuroscience research by Matt Lieberman shows how just acknowledging your stress can move reactivity in your brain from the automatic and reactive centers to the more conscious and deliberate ones. In one study, participants in a brain scan were shown negative emotional images. When asked to label the emotion the images invoked, neural activity moved from the amygdala region (the seat of emotion) to the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain in which we do our conscious and deliberate thinking. In other words, purposefully acknowledging stress lets you pause your visceral reaction, allowing you to choose a more enhancing response.

Another reason to acknowledge and “see” your stress is that evading it is counterproductive anyway. Our research with Peter Salovey and Shawn Achor has shown that individuals who view stress as debilitating tend to either over or under react to stress whereas those with a “stress is enhancing” mindset have a more moderate cortisol response to stress and are more willing to seek out and be open to feedback during stress, which can help them learn and grow for the longer-term.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Managing Stress at Work

Managing Yourself Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Mindfulness and other centering practices can help you acknowledge and transform how you are responding to duress. Each person reacts differently. Do you have a racing heart? Clenched muscles? Or are you in the minority who feel a sudden urge to fall asleep? What are your psychological reactions? To judge? Blame others (or yourself)? How about your behavioral reactions: Do you check out of the conversation all together? Rush to the refrigerator? Noticing these reactions releases us from their grip and helps shift our focus to pursuing more productive responses.

Step Two: Own It

The key to “owning” your stress is to recognize that we tend to stress more, and more intensely, about things that matter to us. Stress shows us that we care; that the stakes matter. Owning this realization unleashes positive motivation—because deep down we know that things that are important shouldn’t always come easy. A metaphor we often use to describe this state is “It’s just a cold, dark night on the side of Everest.” If you were climbing Everest, you could imagine that there might be some cold, dark nights on your journey up. But what did you expect—that climbing Everest would be a walk in the park? Do you really expect that raising a child, running a business, living a life of impact would be easy? Owning your stress won’t necessary make those cold, dark nights go away but they will likely be a bit more tolerable as you discover a sense of motivation and meaning.

“In Navy SEAL training,” former SEAL Commander Curt Cronin recently told us, “the leadership cadre designs situations that are exponentially more stressful, chaotic, and dynamic than any combat operation so that the teams learn to center [themselves] in the most arduous circumstances. When the stress of the training seems unbearable, we can own it, knowing that ultimately it is what we have chosen to do—to be a member of a team that can succeed in any mission.”

Step Three: Use It

Contrary to what you might think, the body’s stress response was not designed to kill us. In fact, the evolutionary goal of the stress response was to help boost the body and mind into enhanced functioning, to help us grow and meet the demands we face. When the body encounters stress, it pumps hormones such as adrenaline and dopamine which fuel the brain and body with blood and oxygen, a response which propels the individual into a state of increased energy, heightened alertness, and narrowed focus. Although the stress response can sometimes be detrimental, in many cases, stress hormones actually induce growth and release chemicals into the body that rebuild cells, synthesize proteins and enhance immunity, leaving the body even stronger and healthier than it was before. Researchers call this effect physiological thriving, and any athlete knows its rewards.

The issue, then, is not in the stress response itself but in how we channel or employ this response. Simply reframing your response to stress as something that is beneficial can be helpful. Researcher Jeremy Jamieson demonstrated that students asked to reframe pre-test anxiety as beneficial perform better on the exams. Harvard Business School professor Alison Wood Brooks has shown how reframing anxiety as excitement can improve performance on tasks such as negotiating and giving an important speech.

Sometimes, however, it is not so clear how best to use stress, especially with longer-term or more complicated situations. Consider an ongoing conflict with a spouse or a boss, a complex health condition or even the recent passing of a loved one. The key in these cases is to simply be open to the opportunities and learning inherent in the stress. Experiencing these challenges as an inherent part of our life-cycle—no one goes through life untouched by grief or heartbreak—can facilitate the acquisition of mental toughness, deeper social bonds, heightened awareness, new perspectives, a sense of mastery, greater appreciation for life, a sense of meaning, and strengthened priorities. Indeed, some leadership scholars—most notably Abraham Zaleznik—have drawn upon William James’ concept of “twice-born” personalities to argue that great leaders share the common experience of working through traumatic episodes in their lives.

That’s something the SEAL community has learned firsthand in recent years as its combat missions have increased. Commander Cronin recently told us, “After multiple years of back-to-back deployments, post-traumatic stress disorder continued to grow within the SEAL community. Learning about post-traumatic growth, leaning to ask ‘how could these experiences serve us?’ and being pushed to own the experiences that we had been through and use them to fuel our future, proved a powerful tool in helping our individuals, teams and organization thrive, not in spite of the stress but because of it.”

As society we largely fail to frame stress as potentially enhancing and often miss opportunities to learn from and grow from stressful moments. That does not mean that we advocate viewing all stressors as a positive thing; but we do advocate that you embrace your stress response as a powerful tool for helping you overcome the inevitable challenges in life that can—and will—arise.

5 Strategy Questions Every Leader Should Make Time For

Have you ever noticed that when you ask someone in your company, “How are you?” they are more likely to answer “Busy!” than “Very well, thank you”? That is because the norm in most companies is that you are supposed to be very busy – or otherwise at least pretend to be – because otherwise you can’t be all that important. The answers “I am not up to much” and “I have some time on my hands, actually” are not going to do much for your internal status and career.

However, that you are very busy all the time is actually a bit of problem when you are in charge of your company or unit’s strategy, and responsible for organizing it. Because it means that you don’t have much time to think and reflect. And thinking is in fact quite an important activity when it comes to assessing and developing a strategy.

The CEO of a large, global bank once told me: “It is very easy for someone in my position to be very busy all the time. There is always another meeting you really have to attend, and you can fly somewhere else pretty much every other day. However, I feel that that is not what I am paid to do. It is my job to carefully think about our strategy.”

I believe his view is spot-on. And there are other successful business leaders who understand the value of making time to think. Bill Gates, for example, was famous for taking a week off twice a year – spent in a secret waterfront cottage – just to think and reflect deeply about Microsoft and its future without any interruption. Similarly, Warren Buffett has said, “I insist on a lot of time being spent, almost every day, to just sit and think.”

If you can’t find time to think, it probably means that you haven’t organized your firm, unit, or team very well, and you are busy putting out little fires all the time. It also means that you are at risk of leading your company astray.

As famous management professor Henry Mintzberg has described, much of strategy is “emergent.” It is often not the result of a strategic plan just being implemented, but driven by opportunistic responses to unexpected events. Stuff happens. Companies often engage in new activities – customers, markets, products, and business models – serendipitously, in response to external events and lucky breaks. But this also means that business leaders need to make ample time to reflect on the configuration that has emerged. They need to systematically analyze and carefully think it through, and make adjustments where necessary.

Many leaders don’t make that time – at least not enough of it.

If you are in charge of an organization, force yourself to have regular and long stretches of uninterrupted time just to think things through. When you do so – and you should – here are five guiding questions that could help you reflect on the big picture.

1. What does not fit? Ask yourself, of the various activities and businesses that you have moved into, do they make sense together? Individually, each of them may seem attractive, but can you explain why they would work well together; why the sum is greater than the parts?

As the late Steve Jobs explained to Apple’s employees when he axed a seemingly attractive business line, “Although micro-cosmically it made sense, macro-cosmically it didn’t add up.” If you can’t explain how the sum is greater than the parts, re-assess its components.

2. What would an outsider do? Firms often suffer from legacy products, projects, or beliefs. Things they do or deliberately have not done. Some of them can be the result of what in Organization Theory we call “escalation of commitment.” We have committed to something, and determinedly fought for it – and perhaps for all the right reasons – but now that things have changed and it no longer makes sense, we may still be inclined to persist. A good question to ask yourself is “what would other, external people do, if they found themselves in charge of this company?”

Intel’s Andy Grove called it “the revolving door” when discussing strategy with then-CEO Gordon Moore; let’s pretend we are outsiders coming new to the job, ask ourselves what they would do, and then do it ourselves. It led Intel to withdraw from the business of memory chips, and focus on microprocessors. This resulted in more than a decade of 30 percent annual growth in revenue and 40 percent increase in net income.

3. Is my organization consistent with my strategy? In 1990, Al West, the founder and CEO of SEI – the wealth management company that, at the time, was worth $195 million – found himself in a hospital bed for three months after a skiing accident. With not much more to do than stare at the ceiling and reflect on his company’s present and future, he realized that although they had declared innovation to be key in their strategy, the underlying organizational architecture was wholly unsuited for the job. When he went back to work, he slashed bureaucracy, implemented a team structure, and abandoned many company rules. The company started growing rapidly and is now worth about $8 billion.

As a consequence of his involuntary thinking time, West did what all business leaders should do: he asked himself whether the way his company was set up was ideal for its strategic aspirations. What would your organization look like if you could design it from scratch?

4. Do I understand why we do it this way? When I am getting to know a new firm, for instance because I am writing a case study on them, I make it a habit to not only find out how they do things but also explicitly ask why. Why do you do it this way? You’d be surprised how often I get the answer “that’s how we have always done it” [while shrugging shoulders] and “everybody in our industry does it this way.”

The problem is that if you can’t even explain why your own company does it this way, I am quite unconvinced that it could not be done better. For example, when more than a decade ago I worked with a large British newspaper company, I asked why their papers were so big. Their answer was “all quality newspapers are big; customers would not want it any other way.” A few years later, a rival company – the Independent – halved the size of its newspaper, and saw a surge in circulation. Subsequently, many competitors followed, to similar effect. Yes, customers did want it. Later, I found out that the practice of large newspapers had begun in London, in 1712, because the English government started taxing newspapers by the number of pages they printed — the publishers responded by printing their stories on so-called broadsheets to minimize the number of sheets required. This tax law was abolished in 1855 but newspapers just continued printing on the impractically large sheets of paper.

Many practices and habits are like that; they once started for perfectly good reasons but then companies just continued doing it that way, even when circumstances changed. Take time to think it through, and ask yourself: Do I really understand why we (still) do it this way? If you can’t answer this question, I am pretty sure it can be done better.

5. What might be the long-term consequences? The final question to ask yourself, when carefully reflecting on your company’s strategy and organization, is what could possibly be the long-term consequences of your key strategic actions. Often we judge things by their short-term results, since these are most salient, and if they look good, persist in our course of action. However, for many strategic actions, the long-term effects may be different.

Consider a practice adopted by many of the UK’s IVF clinics – of selecting only relatively easy patients to treat, in order to boost short-term success rates (measured in terms of number of births resulting from the treatment). The practice seems to make commercial sense, because it (initially) makes a clinic look good in the industry’s “League Table.” But, as my research with Mihaela Stan from University College London showed, it backfires in the long run because it deprives an organization of valuable learning opportunities which in the long run leads to a lower relative success rate.

When you start a new strategy or practice it is of course impossible to measure such long-term consequences ex-ante, however, you can think them through. For instance, when we asked various medical professionals in these clinics what might be the benefits of treating difficult patients, they could understand and articulate the learning effects very well. They could not measure them, but with some careful thought they could understand the potential long-term consequences before even engaging in the strategic action. Actions often have different effects in the short and long run. Sit down and think them through.

Strategy, by definition, is about making complex decisions under uncertainty, with substantive, long-term consequences. Therefore, it requires substantial periods of careful, undisturbed reflection and consideration. Don’t just accept the situation and business constellation you have arrived at. Leadership is not just about doing things, it is also about thinking. Make time for it.

The U.S. Government Needs to Hire More Geeks

Randy Watson is choking back tears. He is a proud and grizzled Vietnam veteran, standing in front of an audience of hundreds. With the help of his daughter, Randy has just driven 1,100 miles from his home in Joplin, Missouri to Washington, DC to tell the story of how he almost died. But as he stands on stage overcome with emotion, Randy is very much alive. And he wants to thank the people responsible: policy wonks and data geeks.

Three years ago, the White House welcomed the Presidential Innovation Fellows program to the world. The mission was simple: save lives, save taxpayer dollars, and fuel job growth in the private sector. By applying proven methods from Silicon Valley — such as lean startup, agile development and design thinking — inside government itself, the executive branch has since been able to do things long thought impossible. Despite ambitious goals and few resources, the 18 inaugural Presidential Innovation Fellows that started work in the summer of 2012 were able to make game-changing progress in a matter of months.

At the Small Business Administration, Project RFP-EZ demonstrated that a streamlined, more competitive bidding process for government contracts led to 30% savings with no loss of quality. (For perspective, if such a reduction were made across total annual federal IT spending it would amount to saving taxpayers $24 billion per year.)

USAID’s Project Better Than Cash helped move international aid payments from cash to mobile phones. While first-degree payments from the U.S. Treasury had moved to electronic means long before, second-degree payments — from other countries and non-governmental organizations to end-users — needed U.S. help to move from cash to mobile phone payments. This change to digital payments reduced waste and graft (which had been found to constitute as much as 30% of aid dollars), enhanced the safety of U.S. military personal and aid workers, and delivered greater impact toward life-altering development projects across Afghanistan.

And at the Departments of Health and Human Services and Veterans Affairs, Project Blue Button empowered senior citizens and military veterans with their own health information. With a simple log-in to authenticate himself, a veteran could for the first time access machine-readable and human-readable details of their current and past medical conditions, allergies, lab tests and more. It’s Blue Button that brought Randy Watson to Washington.

Randy suffers from congestive heart failure, and after experiencing his eighth heart attack, he awoke in the hospital to a doctor telling him how lucky he was to have been carrying a printout of his Blue Button health data because that information — which the doctor would have had no other way to access — allowed the hospital staff to avert an adverse medical reaction that most likely would have killed him.

However, in the months that followed these successes, the Healthcare.gov website became perhaps the most public technology failure in American history. The website failed not because the project was technically infeasible, but due to overly prescriptive, tech-unaware legislative language, coupled with product development mismanagement by bureaucrats lacking the appropriate know-how.

The former is the responsibility of the legislative branch, and the latter the responsibility of the executive branch.

We need innovation in both branches.

Sadly, neither issue is unique to the Affordable Care Act. As the severity of the Healthcare.gov crisis became clear, President Obama turned to Presidential Innovation Fellows and other technologists from the private sector. By employing an “Innovation Fellows” approach and a heavy dose of 16-hour days, the site was made functional in a matter of weeks. Once the technology worked, eight million people – more than originally forecast — were able to sign up for healthcare coverage in the months that followed.

In order to create more Presidential Innovation Fellows-style successes and fewer Healthcare.gov-style failures, the Administration has scaled up the program with more projects and more Fellows. Born from this effort are the new shared-services division known as 18F and the cross-agency movement called the U.S. Digital Service, which will embed hundreds of technologists across 25 agencies before the end of this Administration.

Just a few weeks ago, President Obama enshrined the Presidential Innovation Fellows program through an Executive Order, saying, “What began as an experiment is becoming a success. That’s why I’m making it permanent. From now on, Presidential Innovation Fellows will be an integral part of our government.”

Of course, there are three branches that make up our federal government. While the executive branch has taken dramatic steps to infuse innovation inside its walls, the legislative branch has not… yet. Now is the time to create a Congressional Innovation Fellows program, in order to better inform the legislative process, test new ideas, and merge technology know-how with policy vision in the halls of the Capitol.

In the 21st century, policy doesn’t work unless the technology works. That simple truth is why we need a federal government — including both the executive and legislative branches – that understands technology and innovation and infuses best practices from Silicon Valley into the very fabric of government. We need to invite more techies, more data geeks, and more innovators to the policy table. If we do, I can only imagine what the Congressional Innovation Fellows and their partners might accomplish — and whose life they might save.

A New Way to Rate Retailers on Providing Good Jobs

Executives have a choice in how they run their operations. They can run them in a way that uses people as interchangeable parts. Or they can run them in a way that leverages a skilled, capable, motivated workforce. Both ways can be profitable. But the employee-centered way is a better way — even in low-cost retail.

In my research, I’ve found that retailers using an employee-centered operations strategy, which I call the good jobs strategy, have two strategic advantages. First, they differentiate themselves by offering low prices and good service at the same time. Second, they are better at adapting to changes in customer demand, technology, and regulation. The good jobs strategy is a strategy in which everyone — customers, employees, and investors — wins.

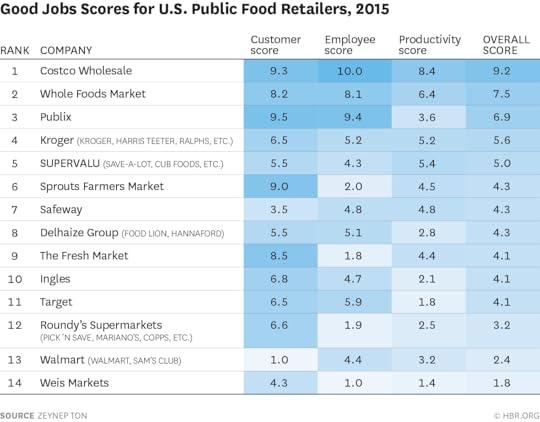

Since my book on this topic came out in 2014, one of the questions I’ve been asked the most is: “How can investors or customers identify which companies in a particular industry are following a good jobs strategy?” To answer this question, my MIT students and I set out to create a good jobs score. We started with food retail and plan to expand it to other settings once we get feedback on our methodology. (So please tell us what you think!) Focusing on the 14 U.S. food retailers that publicly file with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), we scored them in a range of 1 to 10.

Costco had the top score of 9.2, followed by Whole Foods and Publix, at 7.5 and 6.9, respectively. All the other food retailers we scored came in under 6, so there is a lot of room for improvement.

The score is a combination of three components: customer satisfaction, employee satisfaction, and productivity. Companies that follow a good jobs strategy design and manage their operations in a way that allows them to achieve high employee satisfaction, high customer satisfaction, and high productivity simultaneously. A company that does not follow a good jobs strategy will often sacrifice employee satisfaction or customer satisfaction for lower costs, which is commonly thought to be the only way to keep the “low” in low-cost retail. For this reason, we calculate the score as the geometric mean of these components rather than the arithmetic mean, so that a low score on any one of the components brings down the overall score more. In effect, we penalize the sort of trade-offs that the good jobs strategy renders obsolete.

For the good jobs score, we decided to focus on these three outcomes, as opposed to the particular operational practices that drive them. The reason: Collecting data on operational practices such as staffing, level of standardization and empowerment, and extent of cross-training was not feasible without having access to a large number of companies. In our early conversations with some companies, we found that they would not provide such data if we used those data to rank them publicly.

Even collecting data on employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and productivity was challenging. Although employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction are both important drivers of success, most companies do not disclose such data to their investors. We therefore had to rely on secondary data sources, which are not standardized and may have biases.

To create a customer-satisfaction score, we collected data from the American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI), Consumer Reports, and Yelp. Although each of these sources takes a different approach to measuring satisfaction, the results were pretty consistent. For the 14 companies we scored, the correlation between Yelp and Consumer Reports is 0.79, between Yelp and ACSI is 0.93, and between Consumer Reports and ACSI is 0.76. (As a reminder, a perfect correlation would be 1.0.)

To create an employee-satisfaction score, we collected data from Glassdoor.com and Indeed.com. Neither site can affirm that the people who provide data about companies actually work there. In addition, respondents to both sites are self-selecting; thus the data cannot be considered to have been gathered from a random sample of employees. But again, we found that these data sources were pretty consistent. For the 14 companies we scored, the correlation between Glassdoor and Indeed is 0.96.

To create a productivity score, we collected data from 10-K filings with the SEC. We looked at three measures of productivity: sales per square foot, sales per employee, and inventory turnover. Even those data are imperfect at best. Let me give you an example. Inventory turnover is calculated as cost of goods sold (COGS) divided by average inventory level. But even within the same SIC code, there is inconsistency in how companies report COGS. Some include depreciation of inventory; some don’t. Some include promotional expenses; some don’t. Some include compensation and benefits for some of their employees; some don’t. There are also differences in the merchandise mix of different companies. Of course, all the food retailers sell food, but some, like Walmart and Costco, also sell products such as electronics and furniture that are expected to have lower turnover than grocery items.

Clearly, investors concerned with how a company earns its profits — and whether it’s doing the best it could do for customers, employees, and the investors themselves — need better data to assess how well a company manages its operations. I hope that the good jobs score will encourage more companies to report these data.

On goodjobscore.com, we report a lot of other information about each of the 14 companies. Please take a look and let me know how we can improve the score and the website.

September 2, 2015

Make Yourself Immune to Secondhand Stress

HBR STAFF

Over the past decade, we have learned how our brains are hardwired for emotional contagion. Emotions spread via a wireless network of mirror neurons, which are tiny parts of the brain that allow us to empathize with others and understand what they’re feeling. When you see someone yawn, mirror neurons can activate, making you yawn, in turn. Your brain picks up the fatigue response of someone sitting on the other side of the room. But it’s not just smiles and yawns that spread. We can pick up negativity, stress, and uncertainty like secondhand smoke. Researchers Howard Friedman and Ronald Riggio from the University of California, Riverside found that if someone in your visual field is anxious and highly expressive — either verbally or non-verbally — there’s a high likelihood you’ll experience those emotions as well, negatively impacting your brain’s performance.

Observing someone who is stressed — especially a coworker or family member — can have an immediate effect upon our own nervous systems. A separate group of researchers found that 26% of people showed elevated levels of cortisol just by observing someone who was stressed. Secondhand stress is much more contagious from a romantic partner (40%) than a stranger, but when observers watched a stressful event on video with strangers, 24% still showed a stress response. (This makes us question whether we, as happiness researchers, should watch Breaking Bad before going to sleep.)

When your taxi driver honks angrily, you can carry his anxiety all the way to work. When a boss hurriedly stalks into a room, you can pick up her stress as you try to present your ideas. Even bankers on trading floors separated by glass walls can pick up the panic of a person across the room working in a separate market just by seeing their nonverbals.

According to Heidi Hanna, a fellow at the American Institute of Stress and author of Stressaholic, secondhand stress is a result of our hardwired ability to perceive potential threats in our environment. She writes, “Most people have experienced spending time with someone who triggers a stress response just by walking in the door. This can be a conditioned response from previous interactions, but may also be an energetic communication delivered by very gentle shifts in bio-mechanical rhythms such as heart rate or breath rate.” The cues that cause secondhand stress can be very subtle changes in the people around us at work, yet they can have huge impacts.

In fact, you don’t have to see or hear someone to pick up their stress; you can also smell them. New research shows that stress causes people to sweat special stress hormones, which are picked up by the olfactory senses of others. Your brain can even detect whether the “alarm pheromones” were released due to low stress or high stress. Negativity and stress can literally waft into your cubicle.

You and Your Team

Stress

Don’t let it get the better of you.

As the research has become more sophisticated, we see that the negativity we “catch” from others can also impact every single business and educational outcome we can track, and most recently has been shown to impact us down to a cellular level, shortening our lifespan. According to Before Happiness, companies like the Ritz Carlton and Oschner Health Systems, aware of the impacts of secondhand stress, have started instituting “no venting” zones for their employees when around customers or patients. A patient seeing a nurse seething with stress or complaint could catch the contagion as they evaluate the care they receive — not to mention the fact that positive mindset is continually associated with positive health outcomes, as outlined by Tom Rath in Wellbeing.

In our highly connected working world, we are hyper-exposed to other people. This means negative emotions and stress become even more contagious as we have high exposure to negative comments on news articles and social media; stressed body language of financial news shows; stressed out people on our subways and planes; and open office plans where you can see everyone’s nonverbals. In such a highly connected world, we need to find ways to improve our emotional immune system, otherwise we risk the negative effects of second handstress. Here’s how:

Change your response: In research we did at investment banking company UBS with Dr. Alia Crum from Stanford’s Mind & Body Lab and Peter Salovey, founder of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, we found that if you create a positive mindset about stress and stop fighting it, you experience a 23% drop in the negative effects of stress. When we see stress as a threat, our bodies and minds miss out on the enhancing effects of stress. (Even at high levels, stress can create greater mental toughness, deeper relationships, heightened awareness, new perspectives, a sense of mastery, a greater appreciation for life, a heightened sense of meaning, and strengthened priorities.) Instead of fighting and being frustrated at negative people around you, take it as an opportunity to feel compassion or a challenge to help that person become more positive. Our HBR article “Making Stress Work for You” includes more ideas on how to change your stress mindset to a more positive one.

Create positive antibodies: We need behaviors that can neutralize the negative effects of a stressed person. Instead of returning a harried coworkers’ stressed nonverbals with an equally stressed grimace of your own, return it with a smile or a nod of understanding. Suddenly you have the power. As suggested in the new book Broadcasting Happiness, you can create a “power lead” to short-circuit a negative encounter. The first comment in a conversation often predicts the outcome. Try to start your phone calls not with “I’m swamped” or “I’m so busy.” Instead, start with a breath and calmly say: “It’s great to talk to you.”

Build natural immunity: One of the greatest buffers against picking up others’ stress is stable and strong self-esteem. The higher your self-esteem, the more likely you will feel that you can deal with whatever situation you face. If you are finding yourself being impacted by others’ moods, stop and remind yourself how things are going well and that you can handle anything that comes your way. Exercise is one of the best ways to build self-esteem, because your brain records a victory every time you exercise, via endorphins.

Inoculate yourself: Inoculate yourself before going into work or stressful environments. For example, before we start our morning, the very first thing we do is think of three things we are grateful for that day. In this TED talk, you will learn the five positive psychology habits that help inoculate your brain against the negative mindsets of others: 1)writing a 2-minute email praising someone you know; 2) writing down three things for which you’re grateful; 3) journaling about a positive experience for two minutes; 4) doing cardio exercise for 30 minutes; or 5) meditating for just two minutes.

Nowadays, we may know to avoid smoking lounges and we wash our hands after being in busy airports, but in the future, we may realize the key to health and happiness is improving our emotional immune system to protect ourselves from others’ stress. And of course, it’s not just other people’s stress that matters — our own mindset affects the happiness of those around us. A positive mindset can improve our own lives, and the lives of everyone around us.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers