Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1257

August 27, 2015

When Everyone Is Doing Design Thinking, Is It Still a Competitive Advantage?

Design thinking has come a long way since I wrote about it here in 2008. The most valuable company in the world places design at the center of everything it does. Designers are on the founding team of countless disruptive startups. Domains such as healthcare, education, and government have begun to prototype, iterate, and build more nimbly with a human-centered focus.

Now that design thinking is everywhere, it’s tempting to simply declare it dead—to ordain something new in its place. It’s a methodology always in pursuit of unforeseen innovation, so reinventing itself might seem like the smart way forward. But in practice, design thinking is a set of tools that can grow old with us. And I’d argue that in order to create sustained competitive advantage, businesses must be not just practitioners, but masters of the art.

Adapting from William Gibson, the future of design thinking is here, it’s just not evenly distributed. Some complex and large-scale systems are adopting the practice in holistic ways. The Innova School System, for example, with 23 schools thus far, is applying design thinking across its platform, from how the classrooms are built to the curriculum. Likewise, the UK’s Design Policy Unit has shown how taking an agile, iterative approach across a broad range of government services can make the whole system feel more open, transparent, and easy to participate in.

But I can count such examples on one hand, and that unevenness in distribution is due to a lack of creative mastery. For organizations that haven’t invested in a sustained way, the end results can be incremental and short-lived. Customer satisfaction and sales might see a bump, but incremental ideas are easy to copy. True competitive advantage requires non-obvious solutions executed in elegant ways.

One company that’s going for creative mastery is Umpqua. When the bank acquired Sterling Financial Corporation over a year ago, doubling its size and creating the West Coast’s largest community bank overnight, CEO Ray Davis seized the moment to reinvest in design thinking across the organization. Umpqua created and set up an exhibition at its headquarters in Portland, Oregon, focused on designing human-centered experiences, products and technological tools. Teams large and small, from executives to associates, walked through the exhibit, and Davis invited them to sign their names at the end only if they sincerely believed in the approach. Company evangelists handed out Moleskines with tips on “how to be better-makers,” and an internal tool (built on IDEO’s OI Engine) helps teams master design thinking through open-platform challenges. Design thinking even shows up in the questions asked during reviews, when employees are evaluated on how successfully they’re building its principles into everyday work.

Getting to that kind of mastery is our challenge for the next decade. How might organizations build deep design thinking skills and creative leadership at all levels? Lucky for us, there are a host of resources to turn to: Udacity and Kahn Academy, executive training at the d.School and Rotman, and new courses offered at our own IDEO U.

Whenever I’m faced with a tough business challenge, rather than trying to use some prescribed CEO logic, I tackle it as a design problem. That’s not an inborn ability, it’s a skill—OK, a mastery—learned over many years of doing.

What Driverless Cars Mean for Today’s Automakers

The rumors have finally been confirmed: Apple is building its own autonomous car. With Apple’s entry, it’s clear. The automotive industry has opened up again. The manufacturers we’ve become so familiar with over the last century — Daimler, Ford, BMW, Volkswagen, Toyota, and General Motors — aren’t necessarily the vendors we’ll be thinking of in the future. Competition is increasingly going to come from tech firms like Tesla, Google, and Apple, each of whom is building towards a future of autonomous vehicles that are basically highly advanced computers on wheels.

We may be entering an era in which cars are built in entirely different ways — and we might be surprised by what comes out the other side.

For a little bit of context, I’d recommend traveling back in time 50 years and looking at an entirely orthogonal industry: shipping.

Up until the late 1950’s, anyone interested in sending bulk product across the globe placed that product in 60-pound burlap sacks, sent those to the docks, and entrusted longshoremen to tuck them efficiently into nooks and crannies in the hulls of merchant vessels. When the sacks arrived at their destination, the shipper had to trust that a foreign group of longshoremen would be able to locate the right ones and help them find their way to their destination.

Courtesy of Boston Public Library

It wasn’t until the late 50’s that the standard shipping container emerged. This allowed merchants to put their product in locked containers at the point of production — containers which could be efficiently loaded on and off of trucks, trains, and ships. It was clearly a superior method of managing commerce. It made trips that could last months possible in just days. Its superiority can be seen today in any modern port, each of which has landscapes dominated by shipping containers, the cranes needed to lift them, ships designed specifically to carry them, and a constant dance of boxes to and from various locations.

But to capture the full potential of the shipping container, we needed to change how ports operated, how union employees were compensated, how ships were designed, and the very structure of business in the logistics industry. All of this despite the fact that the technical change itself was quite “small.”

Adding self-driving capabilities to a car seems like a similar shift. Cars will still have complex computers, four wheels, comfortable seats, and the like. Today, we can imagine a new “autopilot” feature being added to our Audis, Toyotas, and Hondas. Maybe we’ll hop in the back seat and catch up on email or the news as we ride to work — essentially being chauffeured by the computer.

But what’s more likely is that in order to take full advantage of this new technology, everything will have to change.

The very beginning of this transformation is apparent in the rise of cloud transportation services like Uber, Zipcar, and others. But in a world where cars are capable of safely and efficiently moving themselves around, it will be more than the likes of Uber that change how cars need to be designed and manufactured.

Namely, three questions stand out in particular:

What happens when accidents can be avoided entirely?

Early autonomous vehicles have been modified from those we use every day, and look pretty similar. But what happens when the technology is good enough that accidents can be avoided entirely? We certainly won’t need driver’s seats any longer. Cars will probably be able to have less metal and more glass. Companies will likely be able to experiment with the shape and size of the cars they make.

Clay Christensen used to advise auto manufacturers to focus on their customers’ jobs-to-be-done, understanding when their customers were looking for mobile offices and when they wanted family transport vehicles. In a world where cars can drive themselves and passengers don’t need to look at the road, we can imagine cars being built around conference tables. We can even imagine bedrooms on wheels, where passengers looking to go long distances hire a car for a night, go to sleep, and arrive upon waking in their destination.

What happens when the fleet is owned by profit maximizers?

The rise of cloud transportation implies that more and more of the automotive fleet will be owned by businesses who rent them out to individuals on an as-needed basis. And businesses often make buying decisions in fundamentally different ways than individuals do.

Ridesharing companies such as Uber will care less about incremental features that add to personalization or comfort and more about gas efficiency and cost. As the ability to resell automotive assets into the consumer population dwindles, companies like Hertz and Zipcar will care more and more about the lifetime drive miles of their cars and the ability to quickly refresh car interiors.

Businesses may also push automotive manufacturers to align their designs with transportation vendors’ business models — the way Boeing and Airbus ensure that they build planes to be the most profitable investments for their partner airlines. Since cars will be able to take themselves to the mechanic, you can imagine automakers being asked to deliver much more frequent maintenance schedules, designing cars to be tuned up quickly and ensuring that the chance they’re scrapped is next to nil. We might even see car manufacturers take over large maintenance contracts for their cloud transportation customers, ensuring that Uber is always up and running at a standard cost per drive mile.

What happens when brand stops mattering?

The Super Bowl is a great indicator of the importance of brand today. It costs millions of dollars to produce and place a 30-second spot to grab the attention of potential US customers. Last year, almost a full 15% of Super Bowl ads were paid for by car companies trying to grab the hearts and minds of consumers. What happens when that all changes? When individuals are requesting cars on demand that suit their needs at a particular moment, the brand of that car may no longer matter. The Chief Marketing Officer of Mercedes likely won’t be spending millions on 30-second spots.

Individuals often make irrational economic decisions based on the importance of brands. They find themselves affiliating with companies and gaining utility from their association. Apple is a perfect example. Individuals will buy Apple products regardless of feature comparisons. That’s wonderful for Apple, a company that makes the most personal product imaginable — the computer you keep on your person at all times.

When businesses are buying your product, however, brand isn’t a strong differentiator. For automotive companies, my intuition is that this might become the hardest shift to deal with. Today, they have expansive marketing infrastructures and models designed to appeal to the individual buyer. Adapting to a world where more rational buying decisions are made means redirecting those marketing dollars towards product improvement or price cuts. Inside a large company, that means shifting power dynamics and reorganization — never an easy process.

We can’t know for sure what the impact of driverless technology will be in the future. But we can bet it will mean a lot more than a robot chauffeur for the car you already own.

Even for Companies, the U.S. Is Split Between Haves and Have-Nots

The worldwide trend of rising economic inequality applies not only to individuals. Consider what’s happening among corporations.

Companies in the top one-fifth of profitability earn, in aggregate, about 70 times more economic profit (accounting profit less cost of capital) than those in the middle three-fifths combined, according to McKinsey’s database of 3,000 large, publicly listed, nonfinancial U.S. firms.

Moreover, the economic profit of companies that were in the top fifth in 1997 (at the start of the dataset) grew by close to 50% over the subsequent 15 years, so that the gap between the most and least profitable firms in the sample increased over time.

Sound familiar? Even in the corporate world, the rich are getting richer.

As for whether this is a new phenomenon, consider McKinsey’s dataset, stretching back to the 1960s, on 5,000 U.S. companies’ return on invested capital (ROIC), and compare it with economy-wide ROIC estimates constructed by Deloitte. The comparison is imprecise, of course, but nevertheless suggestive.

Economywide ROIC has trended downward since the 1980s, falling from above 6% in the mid-1960s to 5% in 1980, then to 3% in 1990, and to only a bit more than 1% by 2010. Deloitte attributes this fall in part to rising competitive intensity, as a result of new technologies and lower entry barriers.

But this phenomenon of rising competitive intensity does not, evidently, apply to all firms. An increasing number of U.S. companies have enjoyed supernormal rates of return. In 1960, only a tiny proportion of major American firms earned an ROIC of 50% or more. The proportion rose slowly and relatively steadily, reaching 5% by the mid-1990s. It then leapt suddenly to 14% by the 2005–2007 period.

So although you might expect that in a hypercompetitive environment, ambitious companies would constantly wrest market share from the leading firms, the reality is quite the opposite.

It appears that some firms have recently become rather insulated from competition and that the performance of these corporate “haves” is diverging from that of the large majority of “have-nots.”

So when billionaire Peter Thiel writes that “there is an enormous difference between perfect competition and monopoly, and most businesses are much closer to one extreme than we commonly realize,” he is onto something.

What are the underlying drivers of this trend? There are many. But the one I would point to first is the rising popularity and growing applicability of patents. McKinsey notes that since the 1960s, the industries that have sustained the highest average returns are those that “rely on sustainable competitive advantages such as patents and brands.”

And patenting activity has recently exploded. The number of patents filed in the U.S. doubled over the 30 years from 1960. The figure then grew by about 3.5 times over the subsequent 20 years. This acceleration was in part driven by the extension of patent law to apply to software in the 1980s, and then by its further extension to business processes in 1998.

Is this a bad thing? To be sure, corporations are not people (except in the legal sense) and don’t feel jealousy or vote for radical wealth redistribution when stuck at the bottom of the ladder. Senior executives in even chronically low-performing sectors (such as airlines) can be successful and well-remunerated. And even if some firms have been stuck at the top of supposedly dynamic industries (Microsoft, Apple) for a rather long time, others have used innovation to rise rapidly (Facebook, Twitter).

But I wonder whether some of the chronic underinvestment we have experienced since the global financial crisis isn’t related to the phenomenon of escalating corporate inequality. Overall corporate profits are at record highs of roughly 21% of GDP. Companies are using this money for share buybacks, or putting it in the bank, running high (and rising) cash balances of close to 15% of GDP. So the problem isn’t a lack of funds.

Which suggests a worrying alternative explanation. It’s the companies at the top of the food chain that have historically tended to invest the most, according to McKinsey. And if the past distribution of economic profits is any guide, these are the companies earning the overwhelming majority of the record profits of today. If these companies are facing less and less effective competition, how much do they need to invest to maintain their dominance?

The data on cash balances suggests an answer: not very much.

This underinvestment has a real cost to U.S. economic performance. Results of a scenario using the Oxford Economics global macroeconomic model suggest that if corporations threw the money they are keeping in the bank into capital investment instead, U.S. GDP growth could hit nearly 5% in 2016.

But as long as these companies remain above the competitive fray, it’s hard to imagine such an investment-led boom happening.

When You Shouldn’t Try to Dominate a Negotiation

Should you act dominantly or deferentially when you negotiate? Negotiators generally believe that dominance will give them an edge—and for good reason. Some past studies have shown that when negotiators act dominantly by raising their voices, expanding their body postures to appear larger, and moving themselves to physical positions associated with power they can often claim more of the value available in a negotiation.

But not always. Colleagues and I have discovered that there are instances when negotiators should act deferentially—they should maintain a constrictive body posture, adopt a softer tone of voice, and take other steps to ensure their negotiation partner feels respected, competent and unthreatened. It all comes down to the complexity of the deal and how the person across the table is behaving. In negotiations with many moving parts, negotiators need to find a conversational dynamic that allows them to exchange information effectively, to unravel the different areas of dispute, and to ensure that all the nuances of a potential deal are fully explored. This is best achieved when two parties attain what we call “dominance complementarity,” wherein one person in an interaction behaves relatively deferentially and the other behaves relatively dominantly.

Why is this? Consider the options a negotiator has when she squares off against someone who acts dominantly from the negotiation’s outset. The negotiator can match dominance with dominance. In this case conflict often escalates, people focus on “winning” each issue, and negotiators become more likely to reach impasses; mutually beneficial tradeoffs are rarely discovered. Alternatively, the negotiator can display deference in response to dominance. In this case the dynamic becomes more comfortable and the negotiators become better able to parse complex issues. In fact, we have noticed that each side will take on a clear role. The dominant negotiator will asert preferences and the deferential negotiator will ask questions to try to find solutions that satsify both parties.

But that does not mean that acting deferentially is always best. If one negotiator acts deferentially from the outset, the other negotiator should actually assume a dominant style. Meeting deference with deference may lead to collegiality; however, it does not reliably lead negotiators to discover the tradeoffs that create “win-win” agreements. Without one negotiator asserting strong statements of preferences or priorities and displaying a degree of inflexibility on these issues, compromises are too quickly made and information that negotiators might have otherwise used to discover more efficient agreements are never discussed.

In a set of two experiments, we had people participate in mock negotiations over either the merger of two companies or over a job offer. Both scenarios involved multiple elements so as to simulate a complex negotiation. We gave participants pay-off grids telling them how valuable each issue was to them using a point system. We instructed some of the participants to act dominantly by using expansive body posture and taking charge of the conversation. We instructed some of the participants to act deferentially by using constrictive posture and making sure that the other person felt respected. The control group received neither instructions to act dominantly nor instructions to act submissively.

Across our studies, we found that pairs consisting of one negotiator behaving dominantly and the other negotiator behaving deferentially reached better deals than did pairs consisting of two dominant negotiators, pairs consisting of two deferential negotiators, or pairs in which neither negotiator received behavioral instructions. We judged the success of the deal by calculating the number of points negotiators accumulated from the payoff grid. They reached these superior deals because they more successfully exchanged information about their preferences and the priorities they placed on different issues. In short, they communicated more effectively – with the dominant negotiators stating preferences and the deferential negotiator asking questions.

It is important to note that while adopting a deferential interactional style with dominant counterparts can help you in complex negotiations, you should not become truly submissive when playing that role. The negotiators behaving deferentially in our study who performed well did not sacrifice their own preferences or ignore their own desires. Instead, they used a more subtle, more respectful conversational approach to satisfy those desires and achieve their goals.

Next time you are negotiating, ask yourself if improving the amount and quality of information exchanged between you and your negotiation partner could improve the quality of the agreement you reach. If so, resist the urge to decide your interaction style before meeting your negotiation partner. Our research suggests that monitoring and tailoring your behavior based on one another’s interaction styles may allow you to achieve higher-quality deals.

August 26, 2015

Research: Technology Is Only Making Social Skills More Important

Automation anxiety reached new heights in 2013, when Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne, researchers at the Oxford Martin School, published a paper estimating that 47% of all U.S. jobs were “at risk” of being computerized over the next two decades. Although the jury is still out about robots stealing jobs, the pace at which AI and deep learning technologies have been advancing isn’t ebbing concerns over a future of disappearing work. As machines increasingly perform complex tasks once thought to be safely reserved for humans, the question has become harder to shrug off: What jobs will be left for people?

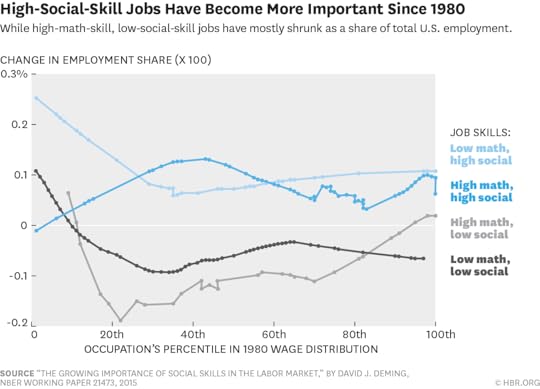

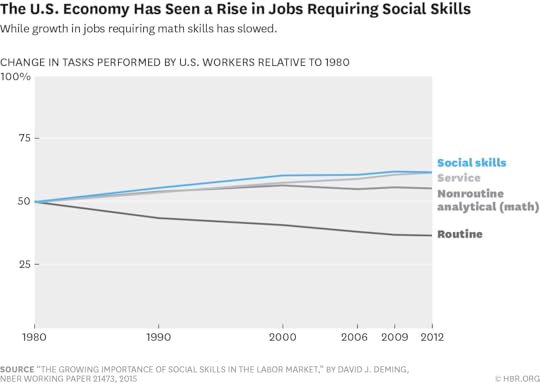

A new NBER working paper suggests it’ll be those that require strong social skills — which it defines as the ability to work with others — something that has proven to be much more difficult to automate. “The Growing Importance of Social Skills in the Labor Market,” shows that nearly all job growth since 1980 has been in occupations that are relatively social skill-intensive — and it argues that high-skilled, hard-to-automate jobs will increasingly demand social adeptness.

This doesn’t mean that analytical skills have become less important. In the paper, David Deming, an assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, explains that since the ‘80s, job and wage growth has been strongest in occupations requiring both high cognitive and high social skills. He builds largely upon the work of MIT economist David Autor, who’s studied the effects of technological change on the U.S. labor market, and that of James Heckman, an economist at the University of Chicago, who’s studied the importance of noncognitive skills — as well as older research on how the labor market has increasingly rewarded people who are both good at math and working with others (see “It’s Never Been More Lucrative to Be a Math-Loving People Person”).

What’s most surprising — and you can see this in the chart below — is that jobs involving a lot of math, but less social interaction, have shrunk in terms of total share of the U.S. labor force over the past three decades. So it still pays to be good at math in today’s labor market, but it’s often no longer enough. “The days of being able to plug away in isolation on a quantitative problem and be paid well for it are increasingly over,” Deming told me. “You need of have both types of skills.”

The paper explains three things about the growing importance of social skills: 1) social skills are valued in jobs across the entire wage distribution (as seen in the chart), 2) social skill and cognitive skill complement each other, and 3) jobs that require low levels of social skills are also likely to be routine jobs (filing clerks, factory jobs) at high risk of automation. Deming studied changes in work tasks using data from the Occupational Information Network (O*NET), a survey conducted by the U.S. Department of Labor that asks people about what they do on the job. He created a measure of social skill intensity — or the extent to which a job requires someone to have social perceptiveness, to negotiate and coordinate with others, and to involve persuasion. He made similar measures to determine the extent to which a job relied on routine tasks, math-oriented tasks, and service work, and then he divided jobs into these four categories.

The data show that social skill tasks grew by 24% from 1980 to 2012, compared to only about 11% for math-intensive tasks. While the latter has declined since 2000, the importance of social skills has grown by about 2% through the aughts. And jobs characterized by routine work have continued to decline.

So why are social skills so prized in today’s labor market? One reason, Deming explains, is because computers are still bad at simulating social interaction. And something that’s become more important in the modern workplace is being able to play off a team member’s strengths and adapt to changing circumstances. “If it’s true that work is becoming more team-based, and there’s a lot of evidence that it is, then it ought to be true that people who are more able to work with others will be more valuable,” he told me. “Because the thing about computers, technology, and machines is that they’re very good at the specific things they’re programmed to be good at, but they’re not flexible.”

To illustrate the value of this flexibility, Deming developed a model. It applies the logic of the Ricardo example of comparative advantage — one of the fundamentals of trade economics — to a team setting, so instead of countries trading goods, he conceptualizes workers trading tasks. The general idea of the model (he presents a different, much more thorough story in the paper) can be simplified as such:

Two colleagues, Dan and Sarina, have to write up a report. Dan is a stronger writer; Sarina is better at working with data. Since Dan’s comparative advantage is writing, and Sarina’s is data analysis, in order to work together efficiently, Dan does one thing, Sarina does another. This way, it takes them less time or effort to produce the same report. But then they bring in another coauthor, Nick, and he is even better at data analysis. Sarina would have to adjust and farm the analysis to Nick, so that she could do something else, like conduct more research or meet with clients.

Part of what being good at working on a team means is being able to adjust when your comparative advantage changes. Machines aren’t quite this agile (yet), whereas people can be. Social skills helped Sarina adapt when she needed to, and the team was more productive because of it. “The model is trying to capture this idea that being a good team player is valuable to employers,” Deming explains. “It’s trying to provide a rationalization for how being able to work with others might make someone more productive, and why employers would be willing to pay a higher salary to someone who has these social skills.”

Still, the model is conceptual. Deming didn’t have actual data on how people allocated tasks within a team inside a firm, and you can speculate about other factors at play. Social skills might not necessarily make you more productive on a team — or what we think of as social savvy could be an extension of cognitive skills (i.e., those with high IQ are better able to collaborate on teams). Perhaps Nick should have actually replaced Dan, since he’s also a better writer, but Dan had a better relationship with the boss, and that’s what cemented his role. The picture gets messier when you throw in real-world office politics.

Deming did turn to data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79) to test if his model worked. The survey has tracked respondents from adolescence into their mid 50s, measuring things like test scores, sports or club participation in high school (a proxy for social skills that’s been shown to predict labor market outcomes later on), and adult employment and income. This data let him measure the difference in wages for people with (self-reportedly) high social skills versus people with low social skills, across occupations.

What he found was that people who have higher social skills, as measured by the survey, earn more money — even after controlling for things like their education, their cognitive skills (measured by standardized scores), what type of job they’re in, etc. — than those with poor social skills. There seems to be a positive return to social skills in the labor market, according to the data, and that return is relatively greater when people are in jobs that require more interaction with others.

Again, this measure of social skills is not perfect, but Deming argues that a better measure would likely make the results stronger. Regardless, more work needs to be done in order to understand what it is about people skills that makes one more valuable in the labor market.

The paper also touches on an interesting correlation between two labor market trends: social skills becoming more important and the narrowing of the gender gap when it comes to jobs and wages. Deming admits it’s speculative — he doesn’t have direct evidence of differences in social skill by gender — but he cites other studies that show women tend to score higher on emotional and social intelligence tests. “It’s more of a conceptual leap,” he said. “But I don’t think it’s an unreasonable one.”

The call for social skills, “soft” skills, emotional intelligence, and the like, isn’t something new. Employers are constantly stressing the need for workers who can collaborate and communicate on teams. Meanwhile, the evidence on how automation effects employment remains inconclusive. (Other studies have posited that robots might be improving productivity, rather than costing jobs.) But while it might be too soon to start bracing for a dystopian no-jobs future, it’s not too early to think about whether people are learning the right skills they’ll need to succeed in tomorrow’s workforce.

Stress Is Your Brain Trying to Avoid Something

Stress exists in every workplace, and all of us have probably tried a few trendy stress-management approaches. But rather than trying the latest fad, it may be more effective to understand how stress works and where it comes from, so that you can create your own methods for dealing with it.

Stress is an emotional response; like all emotional responses, it emerges from the functioning of the motivational system. Your motivational system engages goals and gives them energy so that you can pursue them. Simply put, when you succeed at your goals, you feel good, and when you don’t succeed you feel bad.

Stress is a negative emotion, so the first thing we can see about stress is that it reflects a goal you are not currently achieving.

Your motivational system also has two distinct subcomponents. One (called the approach system) is focused on achieving desirable outcomes, while the second (called the avoidance system) is focused on avoiding undesirable outcomes. These two systems lead to distinct sets of emotions.

When the approach system is active (say you’re seeking a promotion), you are happy or satisfied if you succeed and sad or disappointed if you fail. When the avoidance system is active (perhaps a client is threatening to fire you), you are fearful and stressed if you are failing, and relieved if you succeed.

So we can also see stress as a reflection that there is something in your environment that you’re trying to avoid, but that you have not yet avoided successfully.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Managing Stress at Work

Managing Yourself Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Once you understand how stress works, you can begin to take steps to deal with it so it doesn’t become a long-term problem:

Figure out what you’re avoiding. If you are stressed, then something is engaging your avoidance motivational system. Sometimes, it is obvious. Big deadlines, angry clients, and frustrated bosses are obvious parts of your environment. When you are experiencing long-term stress, though, it might be difficult to disentangle the factors that you want to avoid. In this case, it might be helpful to talk to a friend, partner, coach, or therapist about what is going on.

You may discover that the issues at the root of your stress are not important enough to warrant the level of stress they cause. Or perhaps being specific about the causes of your stress can help you to break the cycle of rumination – the pattern of negative thoughts that accompanies, and worsens, stress. You may also be able to generate plans to repair specific problems once they’ve been identified.

Reframe the situation. Every workplace has both avoidance and approach elements. If your daily work life is stressful, you may be focusing too much on what can go wrong. Instead, start thinking about the desirable aspects of work. What do you really want to achieve? By focusing yourself on the potential positives, you engage your approach motivational system rather than the avoidance system and open yourself up to more experiences of joy and satisfaction.

A Gallup study suggests when people see their work as a calling, they experience higher levels of life satisfaction than when they don’t. A calling is a set of desirable outcomes that connect the workplace to a larger set of societal issues. When you feel stressed, try focusing on the bigger picture – and the broader mission.

Learn to calm yourself. Another key element of stress is the energy or arousal related to it. Your motivational system needs energy to be engaged. When you find your stress levels climbing too high, and you can’t reframe the situation, then you need to remove the energy driving the feelings of stress.

The mindfulness meditation techniques that have become so popular can help you to find the objects driving your stress, but they are also good at helping you to diffuse some of the arousal driving the stress response. Taking a few minutes to disengage yourself from the workplace and to focus on your breathing can help you to calm down.

It can also be helpful to burn off some of that energy. Schedule some exercise for the middle of the day. Go for a walk, hit the gym, or attend a yoga class. The motivational energy generated by the avoidance system prepares you to act in the world. If you spend your day sitting at a desk, then that energy has nowhere to go. Channeling it into physical activity is a healthy way to release that energy and let you get back to work.

Ultimately, stress involves some object (or objects) in the world that engage your avoidance motivation and give that system some energy. You can control that stress response by addressing any of those three elements. Understand the objects, try to control the motivational system that is active, and use the energy either to get productive work done or else find a way to dissipate it.

The False Promise of the Single Metric

Managers and boards are often pushed by investors, fund managers, and analysts to focus intently on a single measure of success, such as shareholder value or profit, and then they do everything they can to maximize it. As a result, they tend to overlook other important measures — for instance, customer satisfaction, employee motivation, and supplier support — and their narrow view of the organization can do long-term damage. Consider “Chainsaw Al” Dunlap, infamous for his profit-at-any-price approach to corporate turnarounds. He left a trail of failed companies behind him, including the iconic Sunbeam. He’s an extreme example, but one that shows what happens when you lose sight of organizational complexity.

Companies should be managed much more holistically. As complex systems, they require systems of measurement to track progress against key goals. It’s common sense, but it bears repeating, given how many companies don’t operate that way.

I know firsthand how challenging it can be to take a holistic approach, especially when your organization is in crisis. I was once a CEO leading a corporate turnaround. After I’d taken the reins of a loss-making manufacturer of trusses and frames for houses, the management team had to give the bottom-line its sole attention to get the company back to profitability. In short, we had to be a bit myopic to survive. Unprofitable, but still promising, product lines were cut, timber stocks were reduced to a bare minimum, employee numbers were razored, and long-term development activities were curtailed. We saved the company from being wound up — barely. But we also cut away the company’s muscle, leaving only the skeleton. It was no way to run a firm over the long term.

Certainly, some enlightened CEOs and boards understand this. When Paul Polman became the CEO of Unilever, for example, he stopped giving analysts earnings guidance, dispensed with quarterly profit reports, and said there’d be no special treatment for hedge funds. Instead, he focused his metrics on the long-term needs of a full range of stakeholders, as Unilever’s annual reports demonstrate. Initially the market took a dim view of this shift, punishing the stock price. But it rebounded months later, after analysts accepted Polman’s wider lens.

Think of it this way: Organizations are a lot like individuals. To live a full, satisfying life, you probably wouldn’t focus exclusively on wealth, sacrificing every bit of joy so you can have a large bank balance on your deathbed. Nor, most likely, would you concentrate only on your health, wrapping yourself in cotton wool to take zero risks with your well-being. Maximizing one thing would mean giving up too much in other areas. Most of us have found that it’s better to work on a combination of things — to look after the whole self’s best interests — by making many choices over time, from the foods we eat to the relationships we build.

Similarly, business leaders and governance teams must look after the whole company. Indeed, they’re charged by corporate law to do so. Their mandate is to improve the probability of their organizations’ long-term survival and growth. To gauge their success, they need a composite scorecard with both objective and subjective targets for key stakeholders. For instance, they may want to gauge employees’ productivity, innovation, and contentment, and customers’ profitable revenue and satisfaction. And so it goes, stakeholder by stakeholder.

But here’s the thing: Even if a metric is classed as objective, someone ultimately has to apply the “good enough” test, which is subjective. This requires continual judgment and adjustment —it’s much messier than using a single metric — but it’s what executives and boards get paid for.

The Reason Smart People Sometimes Struggle with “Aha” Moments

HBR STAFF

I’m increasingly jealous of people with fantastic working memories — as psychologists define it, the ability to ”hold and manipulate information in a temporary active state.” These people can get where they’re going without constantly staring at the GPS, can remember new people’s names from the beginning to the end of the conversation, and don’t have to re-read the recipe between every added teaspoon. How nice that must be! How freeing!

But new research does offer a ray of hope to those of us who can’t break eye contact with Google Maps and conclude networking conversations with the usefully ambiguous, “Nice to see you!”

Marci DeCaro, Charles Van Stockum Jr, and Mareike Wieth explain the results of two experiments in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition.

Having a high working memory capacity (WMC) generally helps with problem-solving by allowing us to avoid distractions, pull up relevant information, and complete multiple steps in a complex task. But not all problems benefit from that approach.

Previous research has shown that people with high WMC will choose problem-solving strategies that play to their strengths, adding more steps and complexity to the process than are strictly necessary — or efficient. Researchers have also found that high WMC individuals will direct the power of focused attention on activities that are actually performed better without it (such as dribbling a soccer ball or touch-typing).

DeCaro, Van Stockum, and Wieth wanted to examine how working memory capacity influenced a specific type of problem: insight problems. These are problems that don’t benefit from an incremental, step-by-step approach, but instead tend to be solved by reframing the issue. If you’ve ever had an “aha” moment, you may have just solved an insight problem.

The researchers began by subjecting participants to a test in which matchsticks had been arranged into nonsensical equations made of Roman numerals. Participants were instructed to make the equations make sense, by moving a single matchstick. As they expected, people who’d shown high WMC (as measured in a previous exam) were less likely to solve the problem — perhaps because they continued to try multiple incremental approaches for longer when it would have been better to give up and try reframing the problem or use lateral, associative thinking.

They then conducted a second experiment using seven word problems. Three of these were incremental problems, three were insight problems, and one was a very easy incremental problem to use as practice. (Here’s an example of an insight problem: Water lilies double in area every 24 hours. At the beginning of the summer, there is one water lily on the lake. It takes 60 days for the lake to become completely covered with water lilies. On which day is the lake half-covered?* Incremental word problems are the logic puzzles that involve a series of requirements, like the famous fox, goose, and bag of beans problem.)

This time, they initially saw that high working memory capacity had no impact on the insight problems, but that changed after controlling for some of the problem-solving processes shared by both incremental and insight problems (such as initial representation of the problem). This led them to theorize that high working memory capacity might be especially detrimental to specific aspects of solving insight problems (such as restructuring them).

How counterintuitive is this? Well, there’s a huge body of research out there that shows that having a high WMC is better than not having one, and that the ability to focus your attention generally leads to better results on cognitive tasks. But there’s also a growing body of evidence that this is not always the case. As the researchers write, “These findings are consistent with a growing body of research demonstrating that lower WMC is advantageous to tasks relying on more associative or procedural processes (DeCaro & Beilock, 2010). These findings are also consistent with others in the problem-solving domain demonstrating that individual difference and situational factors that disrupt attentional control facilitate insight, such as frontal lobe impairment (Reverberi et al., 2005), moderate alcohol intoxication (Jarosz et al., 2012), or solving problems at one’s nonoptimal time of day (Wieth & Zacks, 2011).”

The upshot: If you’re the sort of person who remembers everything and proceeds methodically, perhaps the next time you look for insight you should start by having a glass of wine.

*The 59th day.

Why People Are Drawn to Narcissists Like Donald Trump

HBR STAFF

Donald Trump is an official phenomenon. The real estate tycoon and TV celebrity’s ongoing success as a presidential candidate shows that he has clearly struck a chord with many voters. It has also confounded many citizens and pundits who predicted that Trump’s arrogant putdowns and grandiose claims would doom him to quick rejection by Republican voters. How is it that after outbursts that would not be tolerated in a schoolroom, Trump’s relationship with his followers just grows stronger? What do his followers like about Trump?

The answer may have as much to do with Trump’s achievements as his proposed policies. Unlike his rivals, he has made a fortune by his own efforts; he can convincingly claim he is his own man while his rivals are puppets, indebted to the big money donors his followers distrust.

But his appeal may have even more to do with his personality. No one pushes Trump around, and no insult goes unanswered. He fights back. He is not cautious or fearful of offending a critic or any of America’s adversaries. In this, Trump has a personality type that’s common to the charismatic leaders who emerge in times of turmoil and uncertainty, when people are ready to follow a strong leader who promises to lead them to greatness. Sigmund Freud called people with this personality type “normal narcissists” and he described them as independent and not vulnerable to intimidation, also noting that they have a large amount of aggressive energy and a bias for action. Freud included himself in this group and saw these narcissists as driven to lead and to change the world. Such narcissists can be very charming, and indeed, research has shown most of us like to follow narcissists.

I have done much additional study of leaders such as these, whom I call productive narcissists. The results of this research were first published in my Harvard Business Review article of 2000, “Narcissistic Leaders: The Incredible Pros, the Inevitable Cons” (which was later expanded into a book). I wrote that productive narcissists like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and Larry Ellison were exploiting new technologies to create great companies, just as Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Henry Ford did over a century ago. However, I also illustrated that people with this personality type, however brilliant, have potential weaknesses that can do them in.

They can become so tied to their visions that they lose touch with reality. They can become so self-important and thin-skinned that they lash out at subordinates who question them. They can act as though the rules don’t apply to them. They can end up isolated in their own worlds.

The productive narcissists who sustain success recognize their vulnerabilities and compensate for them. A few years ago, I was invited to a meeting of Italian business, government, media, and academic leaders to discuss narcissistic leaders – a topic of keen interest at that time when Silvio Berlusconi, a grandiose narcissist, was prime minister. The president of the Italian senate said that I was correct that visionary leaders were productive narcissists. But to sustain their success, he said, they should learn how to pretend to be humble.

Many leaders through history have understood this. Benjamin Franklin wrote in his autobiography that people didn’t listen to him because they thought him arrogant. But when he proposed his ideas humbly, he was much more effective. Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln were both extremely skillful in presenting themselves as humble. But even more important for a productive narcissist’s sustained success is partnering with people who keep them grounded. Steve Jobs was fired from Apple when he tried to run the company by himself and alienated his subordinates. On his return, by partnering with Tim Cook in operations and Jony Ive in design, he was able to lead Apple to greatness. Both Jefferson with James Madison, and Lincoln with William H. Seward, had trusted subordinates who complemented their strengths.

I’ve seen CEOs who were productive narcissists who have become so inflated with their success and the adulation of followers that they rejected the sidekicks who held them back from rash action. The same is true of national leaders. When Napoleon fired his adviser, Talleyrand, there was no one to dissuade him from his disastrous invasion of Russia.

Narcissistic leaders who have come to me for counseling wanted help in understanding their subordinates and partners. They wanted to control their tendency to lash out at criticism. They wanted to overcome their vulnerability to sycophants and flatterers and to appreciate partners who tell them hard truths. One narcissistic CEO, who often frightened his subordinates with his angry putdowns, came to me for help in understanding himself and his associates. When he told his executive team about our work together, even the coaching skeptics urged him to continue. A little self-understanding made a big difference in his relationships.

Followers must also take a step back to attain perspective. People who have become entranced by charismatic narcissists – whether in the political or business realm – often fail to sufficiently evaluate the leaders’ policies and their ability to execute them. Are the policies realistic? How will they be implemented? What results will they produce in the long run? Do the leaders in question have trusted advisers to keep them from taking rash actions?

Narcissistic leaders can create companies like Apple or those like Enron. Like Lincoln and Nelson Mandela they can change the world for the better, or like Napoleon and Hitler they can lead their followers to disaster. In the final accounting, a large part of the credit for their successes, or blame for their failures, belongs to the people who followed them.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers