Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1259

August 24, 2015

How to Stop Overplanning (Even If You’re a Perfectionist)

When done well, daily and weekly planning rituals can help you travel gracefully through life in a peaceful, intentional manner. But sometimes, overplanning your day-to-day activities can make you a neurotic, stressed-out person who feels like you would have been better off if you hadn’t planned anything in the first place.

In my work as a time coach and trainer, I’ve found that people experience planning stress when they don’t understand the role that spontaneity plays in the process of implementing their plans for the day. Instead of embracing change as part of the process, they get irritated at themselves or others whenever something doesn’t go exactly according to plan, such as a meeting running late or something taking longer to do than expected. They can also cause themselves and others stress when they refuse to move something forward because they don’t have the ideal amount of time to work on it. For example, when the three hours they had designated to work on a project gets shortened to one and a half hours, they may not even bother to start on it.

You and Your Team

Stress

Don’t let it get the better of you.

The way to reap the benefits of daily and weekly planning without these unpleasant stressful side effects is to take a more relaxed approach. In How to Invest Your Time Like Money, I encourage people to use seven ways to achieve the effectiveness that’s only possible through planning, while retaining the happiness brought about by acceptance of and openness to any unexpected circumstances that might emerge:

Intention matters: You wouldn’t want to take a seat on a plane without knowing the intended destination because you could end up heading in the wrong direction. Similarly, the whole point of planning is that there’s a decision in advance about where you want to end up, and the proposed steps to get you there. Sure, pilots often need to adjust their flight path or even land if there are storms. But the fact that they had a specific end point in mind vastly increases the chances that passengers will end up in the right place. Similarly, you will have the best results when you set the course for your day. The next time something comes up that “messes up” your plans and you’re tempted to dismiss planning as irrelevant, remind yourself that your plan did help you set an initial trajectory and equip you to get to your desired destination eventually, even if you have to modify your course along the way.

Redefine a 100% score: One of my coaching clients recently asked me if anyone ever gets 100% on following through on their plans. I told him that a 100% day is rare. For most people, a great day is when you accomplish 60-70% of what you had intended to get done. Later when I contemplated it more, I realized that a better answer would have been that a perfect score should be defined as having confidence that you made the right decisions about how you invested your time based on the data you had in advance on potential tasks, your overall priorities, and the circumstances that arose throughout the day. The best way to evaluate the day is to ask yourself: Did I make the best choices in how I invested my time today? Instead of: Did I do everything as planned?

Don’t waste time obsessing about a perfect plan: There is no perfect plan. Even if there was a way to make one based on the current data, you can’t know what will come up unexpectedly, so you still can’t guarantee that your plans will be perfect. The goal of planning should be to get just the right level of clarity, so you know where you should focus your attention and how to evaluate opportunities that arise. I recommend setting a limit on how much time you invest in planning. For most individuals, an hour is the maximum time appropriate for weekly planning. Then daily planning should take 15 minutes tops, since you’re not re-evaluating all of your priorities, you’re only recalibrating your weekly plan.

Consider plans a road map: Your plan for the day, the week, or even the year, is a road map that gives you a sense of direction and a high-level overview of the various paths you could take. Just as you may find yourself on a detour and then need to turn back to your map to find the best way to continue on your journey, having a plan to come back to after an interruption gives you the insight you need to reroute your schedule. Throughout the day, I’m constantly looking back at my daily plan and saying, OK, based on how long that activity just took or on the fact that an important call came up, what’s most important now? You can do the same. Instead of reverting to checking e-mail after an unplanned meeting or phone call, go back to your daily plan and if necessary, move around items on your calendar or renumber your to-do list to give you clarity on what to do next.

Expect the unexpected: One of the greatest powers of planning is that it gives you the ability to respond to the unexpected without experiencing massive stress. When you plan correctly, you’re looking ahead and moving along activities ahead of deadline. This then means that when something comes up that causes you to have to switch your plans, you can do so without it causing issues, because you planned to have margin. When you don’t plan, you end up being so close to the edge that anything going slightly off kilter can create major problems. To dramatically reduce stress, give yourself a personal goal to complete items at least one day, if not multiple days, ahead of a deadline. This gives you flexibility when an unexpected interruption comes up or when there’s a technology problem.

This is not a test: If your plans—and then the accuracy of their subsequent implementation—form the basis of your self worth, you’re on shaky ground. Although I wholeheartedly believe in intention and discipline, I also know that we can’t control life. We instead need to embrace it. When you find yourself becoming critical of what you did or didn’t do, stop and ask the questions, “What happened?” and “Is there anything I could do differently next time?” Then use your answers to those questions to inform your decisions moving forward.

Be open to creativity: I loved this insight that one of my clients shared with me recently. With his permission, I’m sharing it with you as I feel it’s a wonderful way to think about the interplay between intention and freedom:

“I had some beautiful one-on-one time with my mom this week, where she was teaching me oil painting techniques. She shared how some artists sketch their scene before beginning, but she emphasized that a sketch on canvas is temporary—a guide only—which should not be too detailed, and is not to be strictly adhered to, as doing so can reduce a painter’s spontaneity and hinder creativity in the moment. I relate that lesson to managing my time, as well. I am starting to discover again what’s really important, what I want my life to look like and how to live life more fulfilled. Thank you for helping me realize that it’s my painting and I can paint it like I want it.”

So in short… relax. Breathe. Set your sails and then adjust with the currents and winds. Our safety and security doesn’t lie in our plans, but in our hearts. Life is to be lived and enjoyed, not just “done.”

Productivity Is Soaring at Top Firms and Sluggish Everywhere Else

A spirited debate is now under way on the future of technology and productivity. Some argue that the low-hanging fruit has already been picked: the IT revolution has run its course and other new technologies like biotech have yet to make a major impact on our lives. Others see the IT revolution continuing apace, fueling disruptive new business models and enabling a new wave of productivity growth across the economy. Either technological progress is slowing down, or it’s speeding up. Which view is right? At the OECD, we believe the research from our Future of Productivity project helps to resolve this paradox.

This isn’t an academic question. Productivity growth is the most important driver of long-term economic growth and well-being. But after the productivity surge of the late-90s and early-2000s, which was principally based on the development and deployment of information and communication technology (IT), the United States and other OECD economies have witnessed a significant decline in productivity growth. This has been exacerbated by the Great Recession and the weak post-crisis economic recovery. The slower productivity grows, the less prosperous the world will be.

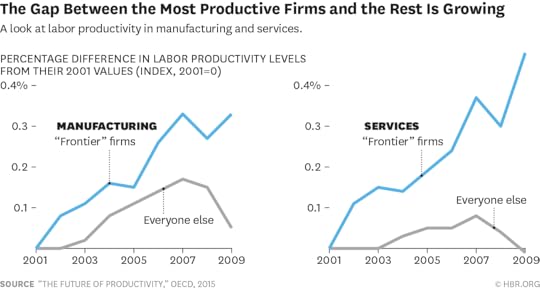

Our research shows that the slow productivity growth of the “average” firm masks the fact that a small cadre of firms are experiencing robust gains. OECD analysis shows that the productivity of the most productive firms – those on the “global productivity frontier” in economic terms—grew steadily at an average 3.5% per year in the manufacturing sector, or double the speed of the average manufacturing firm over the same period. This gap was even more extreme in services. Private, non-financial service sector firms on the productivity frontier saw productivity growth of 5%, eclipsing the 0.3% average growth rate. Perhaps more importantly, the gap between the globally most productive firms and the rest has been increasing over time, especially in the services sector. Some firms clearly “get it” and others don’t, and the divide between the two groups is growing over time.

The strength of global frontier firms lies in their capacity to innovate, which increasingly requires more than just investing in R&D and implementing technology. It requires the capacity to combine technological, organizational, and human capital improvements, globally.

Seen from this perspective, the productivity problem isn’t a lack of global innovation. It’s a failure by many firms to adopt new technologies and best practices. Indeed, the main source of the productivity slowdown is not a slowing in the rate of innovation by the most globally advanced firms, but rather a slowing of the pace at which innovations spread throughout the economy: a breakdown of the diffusion machine.

Future growth will depend on harnessing the forces of knowledge diffusion which propelled productivity growth for much of the 20th century. But what keeps firms from adopting the right combination of technological and organizational innovations?

The list of obstacles to diffusion is long. Four key factors need to function well for effective diffusion to take place. First, global connections need to be extended and deepened, so that firms can learn from successful counterparts across the world. This requires trade, foreign direct investment, participation in global value chains, and the international mobility of skilled labor.

Second, new firms need to be able to enter markets and experiment with new technologies and business models. The productivity slowdown coincided with a near-collapse of overall business investment and a slowdown in business dynamism, reflected in a decline in business startups. These trends need to be reversed.

Third, better “matchmaking” is needed across the economy, to ensure that the most productive firms have the resources—labor, skills, and capital—to grow. The larger the frontier firms become, the greater the extent to which their good performance gets reflected in overall economic growth. Unfortunately, the most productive and dynamic firms do not always grow to optimal scale. In some economies, the most advanced firms have productivity levels close to the global frontier, but they are under-sized relative to their peers in other countries. Inefficient resource reallocation—which can be caused by lack of product competition, rigid labor markets, failure to exit, or non-performing loans—doesn’t just keep frontier firms from growing. It also slows the diffusion of best practices to other firms.

Fourth, investment in innovation should extend beyond technology to include skills, software, organisational know-how (i.e. managerial quality). Innovation depends on the bundling of these investments, and policy initiatives should reflect that.

There’s a lot more policymakers can do to crank up the diffusion machine, much of which is listed in our research. But there are also implications for companies. For firms already at the productivity frontier, new innovations are the key to competitive advantage. But for many others, the goal needn’t be inventing something entirely new. A good start would be simply catching up.

August 21, 2015

How to Stop Micromanaging Your Team

Micromanaging is a hard habit to break. You may downplay your propensities by labeling yourself a “control freak” or by claiming that you just like to keep close tabs on your team, but those are poor excuses for excessive meddling. What can you do to give your people the space they need to succeed and learn? How should you prioritize what matters? And how do you get comfortable stepping back?

What the Experts Say

If you’re the kind of boss who lasers in on details, prefers to be cc’ed on emails, and is rarely satisfied with your team’s work, then—there’s no kind way to say this—you’re a micromanager. “For the sake of your team, you need to stop,” says Muriel Maignan Wilkins, coauthor of Own the Room and managing partner of Paravis Partners, an executive coaching and leadership development firm. “Micromanaging dents your team’s morale by establishing a tone of mistrust—and it limits your team’s capacity to grow,” she says. It also hampers your ability to focus on what’s really important, adds Karen Dillon, author of the HBR Guide to Office Politics. “If your mind is filled with the micro-level details of a number of jobs, there’s no room for big picture thoughts,” she says. As hard as it may be to change your ways, the “challenge is one that will pay off in the long run,” says Jennifer Chatman, a professor at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “There may be a few failures as your team learns to step up, but ultimately they will perform much, much better with greater accountability and less interference.” Here are some pointers on how to let go.

Reflect on your behavior

The first step is to develop an awareness of why you micromanage. “You need to understand where this is coming from,” says Dillon. “Most likely it’s because of some insecurity—you’re afraid it will reflect badly on you if your team doesn’t do something exactly the way you would do it or you’re worried you’ll look out of touch if you’re not immersed in the details, so you overcompensate,” she says. Wilkins recommends “asking yourself: what excuses am I using to micromanage?” Common justifications include: “It will save time if I do it myself.” Or “Too much is at stake to allow this to go wrong.” She advises focusing on “the reasons why you should not micromanage”—it’s bad for your team as they don’t learn and grow—“and the benefits you’d derive if you stopped,” chiefly more time to do your own job.

Get feedback

“Often there is a significant disconnect between what leaders intend and what the team is actually experiencing,” says Chatman. You may merely suspect you have a problem while your team members are already annoyed by your constant hovering “Feedback is essential to see how significant the issue is.” To get a handle on what your direct reports really think and whether it lines up with your intentions, she recommends “undertaking a cross-evaluation assessment.” Gather confidential data from your people—or better yet, have a third party do it—and aggregate those results so employees know you can’t find out exactly who said what. What you hear may be sobering, “but it’s critical to understanding the broader patterns and reactions and the impact [your micromanaging has] on your team,” she says.

Prioritize what matters—and what doesn’t

“A good manager trains and delegates,” says Dillon, and you can’t do that if you’re taking on everything—regardless of how important the task is—yourself. Start by determining what work is critical for you to be involved in (e.g. strategic planning) and what items are less important (e.g. proofreading the presentation). Wilkins suggests looking at your to do list “to determine which low-hanging fruit you can pass on to a team member.” You should also highlight the priorities on your list, meaning “the big ticket items where you truly add value,” and ensure you are “spending most of your energy” on those, she adds. Remember, says Chatman, “Micromanaging displaces the real work of leaders, which is developing and articulating a compelling and strategically relevant vision for your team.”

Further Reading

Are You a Good Boss—or a Great One?

Communication Feature

Linda Hill and Kent Lineback

If you want to keep growing as a leader, ask yourself these key questions.

Save

Share

Talk to your team

Once you’ve determined your priorities, the next step is communicating them to your team, says Dillon. “Have a conversation about the things that really matter to you—the things that they’ll need to seek your guidance and approval on—so your direct reports can get ahead of your anxiety,” she says. Tell them how you’d like to be kept in the loop and how often they should provide status updates. “Be explicit with your direct reports about the level of detail you will engage in,” adds Wilkins. At the same time, enlist their help in making sure you don’t fall back into your old micromanaging ways. Chatman suggests: “Tell them you are trying to work on this” and ask targeted questions such as: How can I help you best? Are there things I can do differently? Are our overall objectives clear to you and do you feel you have the support and resources to accomplish them?

Step back slowly

Fighting your micromanaging impulses might be hard at first so pull back slowly. You need to get comfortable, too. “Do a test run on a project that is a bit less urgent and give your team full accountability and see how it goes,” Chatman says. “Recognize that your way is not the only, or even necessarily, the best way.” The acid test of leadership, she says, “is how well the team does when you’re gone.” Another way to ease out of micromanaging is to discretely seek feedback from other coworkers about how your team is operating, says Dillon. “Ask a colleague you trust: ‘How’s that project going?’” The answer will provide valuable information, says Dillon. “You may feel better knowing that everything is fine, or you may realize you pulled back too much.” In the latter case, you need to “find a way [to support the work] that doesn’t involve peering over your employees’ shoulders.”

Build trust

Because your team members are used to you not trusting them, they may want to come to you for approval before taking charge of a project. “Acknowledge this is a growth opportunity for the person and say that you know in your heart of hearts he or she will rise to the challenge,” says Dillon. This is more than a pep talk. You’re in effect “giving your employee the psychological power to lead.” Making sure your team members know you trust them and have faith in their abilities is actually “very simple,” says Wilkins. “Tell them so. Say, ‘I fully trust you can make this decision.’” And then, “walk the talk,” she says. Don’t excessively scrutinize. Don’t insist on being cc’d on every email. And don’t renege on your vote of confidence. “Let them do it and don’t back pedal and change everything they did.”

And if things don’t go exactly as you’d like, try your hardest not to overact. Take a breath; go for a walk; do whatever you need to do to come “back from that agitated micro-managerial moment,” says Dillon. After all, does it really matter if the memo isn’t formatted exactly to your liking? “For most things, nothing is so bad it can’t be corrected.”

Know your employees’ limitations

“Some people will over correct by pulling away too much; but it’s smart to give appropriate support,” says Dillon. “Talk about how you will help them problem solve and how you’ll support them” even if you’re not deeply involved in a particular project or task. At the same time, keeping a closer eye on certain projects or certain employees is sometimes warranted, she adds. If “your report is junior,” say, or “not yet ready to be trusted,” you will need to keep close tabs on her work. Similarly, says Wilkins, “when the deliverable is urgent and high stakes” it may make sense to intervene or ask to be kept regularly apprised of things. “In this case, it’s helpful if you explain to the person why you are being so hands on,” she says. “You should also give feedback to the employee and coach them, so they can complete the task on their own over time.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Ask yourself why you micromanage and reflect on your need for control

Refine your to do list by prioritizing the tasks and projects that matter most to you

Talk to your team about how you’d like to be kept apprised of their progress

Don’t:

Renege on your vote of confidence—tell your reports you trust them and let them do their jobs

Overact when things don’t go exactly as you’d like them to—take a breath and figure out a way to correct the situation if it’s truly necessary

Go too far—you don’t want to become a hands-off boss

Case Study #1: Clarify your priorities

Jordan Fliegel, the founder and CEO, of CoachUp—the Boston-based startup that connects athletes with private coaches, learned to deal with his micromanaging tendencies after a bad experience early in the life of his company.

It was fall 2013—CoachUp’s second year of business. The company’s summer interns had completed a big blogging project, and CoachUp’s content team was responsible for editing the posts and tagging them for maximal search engine optimization. Given that the company was experimenting with blogs for the first time and the fact that Jordan is a formidable writer in his own right, he says he “felt attached to the project.”

The content team, however, was not moving fast enough on the project. He figured it would be easier and faster if he did it himself. “I took me three weekends to finish the work.”

When he presented the completed product to his team, his employees responded with a mixture of annoyance and puzzlement. “Their reaction was, was this really the most important or high-impact thing you could have been doing with your time? And, if you really thought this project was that important you should have told us,” he recalls.

Jordan understood that by completing the project he had, in effect, been doing other people’s jobs—which is a sure way to “undermine their creativity and drive,” he says.

He now knows to be more explicit about his reasons when he’s delegating certain tasks. “I realize that if I want something to get done, I need to explain the context and the return on investment to the team,” he says. “If there’s pushback—meaning that the team disagrees that it should be a priority—there can be a debate. But I shouldn’t shy away from saying what I think needs to get done.”

He attributes his earlier meddling to his newbie CEO status. “I hadn’t had a lot of experience managing people at that point,” he says. “And as the founder, I was used to doing everything myself. It was hard to let go. When it’s your business—your baby—you want to be involved.”

Today, Jordan is much more hands-off and tries to focus on “working on the business and not in it.”

Case Study #2: Explain why you’re being hands on

Mike Faith, the founder and CEO of Headsets.com, the San Francisco-based headset supplier, says that sometimes micromanaging can be a necessary part of leadership—especially when it comes to training new hires. “I’ve come to the conclusion based on experience that I need to stay close to new employees early on to give encouragement, correction, and learning,” he says. “I can’t let the fear of being called a micromanager prevent me from staying close at first.”

Mike is explicit about his management style with new recruits. “It’s important that they know what to expect. I tell them ‘I am going to check in with you early and often’ and then I follow through and do just that. Once they reach a level of confidence and competence, I am more comfortable pulling back.”

This policy occasionally applies to longtime executives, too. Recently, Mike and his VP of Marketing embarked on a big new project related to how Headsets.com handles online advertising. His VP will handle the day-to-day operations of the project, but Mike has a keen interest in its progress. “I told him that for now, we’re going to stay close to each other and learn as we go. I will be checking in with him daily, and I want him to be checking in with me,” he says.

Mike told his VP that the constant need for status updates wouldn’t be required forever. “I told him that once we get the hang of it and we’re hitting our numbers, we’ll check in with each other monthly or just as needed. There is no perfect recipe or perfect formula,” he says.

Mike also offered his support. “I told him that I had confidence he can do it,” he says. “I said: ‘We are going to try our damndest, and I’ve got your back.”

A Consultant’s Guide to Difficult Client Feedback

During one of my very first consulting assignments, a colleague and I interviewed direct reports of the Chief Information Officer of a chemical company about improving project execution. We consistently heard that the CIO was autocratic and intimidating, and that his people were afraid to talk openly about mistakes. Knowing that this was an important issue for project success, we met with the CIO alone and, with some trepidation, gave him this feedback — direct and to the point. To our relief, he didn’t get angry with us. He just said “thank you” and that he’d take the feedback into consideration. At the next meeting with his direct reports, however, he started by saying, “I hear from the consultants that you’re afraid to be open with me. Is that true?” Of course, each person denied the allegation, after which the CIO turned to us and said: “See, I didn’t think that people were afraid of me.”

In hindsight, it’s easy to see that we should have been more adroit about the feedback process. For instance, we could have couched the feedback in positive terms (“Your team has so much respect for you that they don’t want to disappoint you with news about projects being off track…”). We could have coached the CIO about how to inquire into projects, and we could have suggested a more proactive approach for encouraging people to raise issues.

But we were too anxious to think about these alternatives. After hearing over and over that the CIO was intimidating, we were unconsciously terrified. So our approach to giving feedback was basically: Get it over with and get out of there. Our own anxiety got in the way of giving constructive feedback.

Further Reading

HBR’s 10 Must Reads on Communication

Communication Book

24.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

When left unchecked, anxiety-driven behaviors impair your judgment and prevent you from doing what’s in the best interests of the client. For example, you might worry that the client will disagree with you — and you won’t get a follow-up assignment — and so you’ll try to skirt or sugarcoat uncomfortable issues. This prevents real change from happening.

On the other hand, knowing things about the client’s blind spots or weaknesses can make you feel superior or smug, causing you to convey messages in callous ways. To prevent anxiety from causing poor decisions, consultants need to remove themselves from the feedback they’re giving. Remember that it’s not about you; it’s to help the client become a more effective manager. And while this seems like an obvious point, it’s one that often gets overlooked in the moment. In our case, if we had been more focused on helping the CIO deal with his need for control, rather than managing our fears, the feedback might have made more of a difference.

Besides dealing with your own anxiety, you also have to gauge a client’s readiness to hear your message — and his or her openness to change. Based on that, you can adjust how you deliver feedback accordingly. This requires versatility.

Not long ago, for example, I was working with a large division of a health care company that was struggling to meet its revenue targets. Based on lots of feedback and data, one of the keys to a turnaround was for the division head to be more demanding and to hold people accountable for deadlines and sales deliverables. This manager, however, saw herself as a nice person, and having only recently joined the company, wanted everyone to like her. It was clear that she did not want to come across as “tough.” This meant that I couldn’t just tell her to change her behaviors; rather, we had to explore what it would mean to be more demanding, and test out different ways for her to start being tougher. I walked her through the data until she reached the conclusion, on her own, that “people want me to hold them to deadlines in a more disciplined way.” Once this was her conclusion, we got into a problem-solving discussion about how she might do that, and we eventually came up with a structured weekly results forum, where she could ask her team about performance metrics and deadlines.

The bottom line is that consultants have many different ways to present feedback: You can dole it out in small doses and let the client reach his own conclusions, or you can lay out all the evidence at once and explain what action to take. You can give the client some advance warning about the key messages, or you can surprise her. You can list the next steps for moving forward, or you can collaborate with your client to develop an action plan. There are dozens of other variations in between.

No matter the approach, giving feedback to clients — like giving feedback to anyone, really — is a difficult dance that requires thought, preparation, and learning over time. On the one hand, you have to be aware of your own emotional balance and anxiety, which can cloud your judgment about what to do. On the other hand, you have to assess the client’s ability to listen and do something with the feedback. Then, based on both of these factors, you have to consciously look at the alternatives and decide how to proceed. If you’re too brutal, your message may be rejected or dismissed; if you’re too soft or nice, the client may not take it seriously. If you get this wrong, it could end your consulting relationship. If you get it right, however, it could be the beginning of a valuable partnership.

The Female Soldiers Who’ve Already Joined Special Ops Teams

This week, two women will earn the Ranger tab for the first time. But the path to this day began decades ago, with the women have already served and sacrificed on the battlefield alongside Rangers and SEALs. Those earlier experiences are an important study in building teams, breaking ground on behalf of mission success, and successfully integrating new groups into the established order.

In 2013, I began reporting on a groundbreaking all-women special operations team made up of the finest, fittest and most driven soldiers chosen from across the Army, Guard, and Reserve. As my reporting deepened and grew into the book Ashley’s War, I realized the story of these Cultural Support Teams was not only a story of inspiring individuals – the female soldiers I was profiling – but a broader story of organizational change.

The shift began in 2010. Some of the most tested special operations leaders in the U.S. military concluded that America would never kill its way to the end of its wars. Commanders needed more knowledge and more understanding to gain an advantage on the battlefield. And yet male soldiers could not speak to Afghan women or enter their quarters without causing grave offense in the conservative, traditional societies in which they were operating. Without female soldiers, half the population’s knowledge would remain out of reach.

So the call went out across the Army, Guard, and Reserve: “Female Soldiers – Become Part of History” and join special operations units each night on the battlefield. Most of these units had never taken women on these kinds of combat operations — operations seen by less than five percent of the entire U.S. military. But by 2011, female soldiers who had undergone a selection process that involved a grueling weeklong ordeal known as “100 Hours of Hell” followed by six weeks of training, were joining Army Rangers, Navy SEALs, and other elite units on combat operations each night.

What made this change possible?

First, a sense of urgency. Quite simply, desperation was the mother of innovation. Nine years into a war that was not going well, all anyone wanted was solutions provided and problems solved – and so in 2010, Admiral William McRaven, then leading the Joint Special Operations Command, officially requested that women soldiers join Army Rangers on combat missions. General Stanley McChrystal and others noted to me that ideology might have prevented any leaders from putting in such a request even just a few years earlier.

Second, the elite units the female Cultural Support Teams would be accompanying had already been built with agility and adaptability in mind, and had only gotten more nimble as the wars went on. In other words, they were already used to change. Due to the demands of the post-9/11 world, McChrystal has noted, special operations “started the war as the greatest booksellers in the world and ended as Amazon.com“. No longer did operations take multiple days of planning; now, plans were sometimes forged within hours or even minutes as the evening’s developments demanded. This meant that by the time the Cultural Support Team members arrived to join Ranger teams on nighttime combat missions, the men leading those units already had seen their roles shift and their responsibilities grow. As one Ranger first sergeant told me, the arrival of women was simply one more shift to which his men would need to adjust.

Leaders also set the tone for their units. When one of the women arrived at her new forward operating base, one of the Ranger leaders pulled her aside and told her that most of the guys were pulling for her and to let him know if she had any issues with anyone. She didn’t, but knowing that he had her back offered a boost as she set out to prove herself in the local currency: by adding value each night on mission and by hitting the gym for hours each day in CrossFit workouts. She and her teammates did not look to prove a point, but to serve with purpose and to do their job to the best of their abilities. Knowing that senior Ranger leaders wanted to see them succeed helped them to push even harder and to seek out every opportunity to train with the Rangers whether in the classroom or at the shooting range.

Community mattered. The women formed a support network for one another, keeping isolation at bay while sharing knowledge. As they were venturing into the unknown, joining an all-male culture for the first time in a formal way, they used internet and video technology to cheer one another on and learn from one another on from bases across Afghanistan. This community allowed them a rare chance to enjoy camaraderie with people who knew just what they were facing and be less formal at a time when they were battling hard to prove themselves to men who may never before have worked with women.

Transparency and easy-to-track metrics make the case. And win over skeptics. On their nightly missions, special operations troops often sought a person, a cache of weapons, or intelligence – results tracked by senior leaders. These quantifiable contributions helped convince the doubters: for instance, several Navy SEALs who had initially expressed reluctance about bringing women with them on missions came to appreciate their contributions after an important intel item was found in a baby’s diaper inside the house’s women’s quarters.

Women like these have already served and sacrificed their lives alongside Rangers. Their performance in battle has helped to pave the way for today’s history-making moment when two women have earned the Ranger tab. And their experience offers a lesson in managing change, building teams, and integrating the best talent for the right job.

A Refresher on Price Elasticity

Setting the right price for your product or service is hard. In fact, determining price is one of the toughest things a marketer has to do, in large part because it has such a big impact on the company’s bottom line. One of the critical elements of pricing is understanding what economists call price elasticity.

To better understand this concept and how it impacts marketing, I talked with Jill Avery, a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School and an author of HBR’s Go To Market Tools.

What is price elasticity?

Most customers in most markets are sensitive to the price of a product or service, and the assumption is that more people will buy the product or service if it’s cheaper and less will buy it if it’s more expensive. But the phenomenon is more quantifiable than that, and price elasticity shows exactly how responsive customer demand is for a product based on its price. “Marketers need to understand how elastic, sensitive to fluctuations in price, or inelastic, largely ambivalent about price changes, their products are when contemplating how to set or change a price,” says Avery.

“Some products have a much more immediate and dramatic response to price changes, usually because they’re considered nice-to-have or non-essential, or because there are many substitutes available,” explains Avery. Take for example, beef. When the price dramatically increases, demand may go way down because people can easily substitute chicken or pork.

How is it calculated?

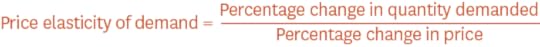

This is the formula for price elasticity of demand:

Let’s look at an example. Say that a clothing company raised the price of one of its coats from $100 to $120. The price increase is $120-$100/$100 or 20%. Now let’s say that the increase caused a decrease in the quantity sold from 1,000 coats to 900 coats. The percentage decrease in demand is -10%. Plugging those numbers into the formula, you’d get a price elasticity of demand of:

Note that the negative is traditionally ignored and the absolute value of the number is used to interpret the price elasticity metric, as it’s the magnitude of distance from zero that matters and not whether it’s positive or negative.

“The higher the absolute value of the number, the more sensitive customers are to price changes,” explains Avery. As she explains in her “Marketing Analysis Toolkit: Pricing and Profitability Analysis,” there are five zones of elasticity. Products and services can be:

Perfectly elastic where any very small change in price results in a very large change in the quantity demanded. Products that fall in this category are mostly “pure commodities,” says Avery. “There’s no brand, no product differentiation, and customers have no meaningful attachment to the product.”

Relatively elastic where small changes in price cause large changes in quantity demanded (the result of the formula is greater than 1). Beef, as discussed above, is an example of a product that is relatively elastic.

Unit elastic where any change in price is matched by an equal change in quantity (where the number is equal to 1).

Relatively inelastic where large changes in price cause small changes in demand (the number is less than 1). Gasoline is a good example here because most people need it, so even when prices go up, demand doesn’t change greatly. Also, “products with stronger brands tend to be more inelastic, which makes building brand equity a good investment,” says Avery.

Perfectly inelastic where the quantity demanded does not change when the price changes. Products in this category are things consumers absolutely need and there are no other options from which to obtain them. “We tend to see this only in cases where a firm has a monopoly on the demand. Even if I change my price, you still have to buy from me,” explains Avery.

Marketers should know where their products fall on this spectrum, but “the actual number is less important than knowing which zone your product falls within and what will happen to consumer demand if you change your price,” she says.

How do companies use it?

This is one of the key metrics for marketing managers, says Avery. “Our job is to create products and services that have unique and sustainable value for customers compared with other options available to them in the marketplace. Price elasticity is a way for us to measure how we’re doing in that regard,” she explains. “If my product is highly elastic, it is being perceived as a commodity by consumers.” It tells you how effective you are at marketing your products to consumers.

“A marketer’s goal is to move his or her products from relatively elastic to relatively inelastic,” she continues. “We do that by creating something that is differentiated and meaningful to customers.” When, through branding or other marketing initiatives, a company increases consumers’ desire for the product and their willingness to pay regardless of price, it’s improving the company’s standing compared with competitors. But it can go the other way. “It’s an important metric to watch because your product may become more elastic if a competitor starts offering compelling substitutes or consumers’ incomes go down, making them more sensitive to price,” says Avery.

Keep in mind that price elasticity isn’t just a factor of how well you’re marketing. It is also affected by the type of product you’re selling, the income of your target consumers, the health of the economy, and what your competitors are doing. “You can’t look at it in isolation,” says Avery. “You have to look at it in context of the industry and its competitive structure and in the context of consumers’ lives.”

As you may have figured out, this is a number that you can only calculate for certain after you’ve made an actual price change and seen the resulting impact on demand. And to be truly certain, you’d have to change your price multiple times to see what would happen at each price point. This is not what companies tend to do in practice. Rather, they send out questionnaires, run focus groups, or perform small-scale experiments in certain markets, to give them a sense of what would happen if they changed their price.

While it’s important to understand the price elasticity of your product or service, much more often, in corporate contexts, people talk about price sensitivity in a more qualitative way, explains Avery. You’ll hear managers say, “my product is price sensitive” or “we’re lucky to have a product that’s not sensitive to price.” Elasticity is not the same thing as sensitivity, she warns. “Sensitivity is more of a qualitative concept where elasticity is a quantitative one. But they are closely related.”

What are some of the common mistakes managers make with price elasticity?

Many managers assume they understand the full picture based on their experience pricing their products in the marketplace, that they know how consumers will respond to almost any price change, explains Avery. But rarely have companies tested extreme price changes. More likely, a company has a small sample of consumer responses to certain price changes, such as what happens when price is raised or lowered by 5-20%. More extreme changes in price may elicit significantly different consumer responses. “The math isn’t complicated,” she says, “but it’s tough to pin down how it will play out in the market because price elasticity is a dynamic concept.” What consumers have historically been willing to pay for a particular product is not necessarily what they are willing to pay today or tomorrow.

Therefore, elasticity can often be an inexact calculation. “It’s impossible to know what customers will do at every price point or in the marketplace,” Avery says. Sure, marketers can get a good sense of willingness to pay from survey responses, but “the challenge is that what people say they will do is not what they actually do when they are standing at the shelf.” It’s better, she suggests, to do a in-market A/B test, to put your product out at the new price point and see what the demand is, and compare it to the same product at a different price. That’s how you’ll get the most accurate information. Avery points out that in a digital context, this is easy and inexpensive to do. “You can put your product up at $10 and two minutes later change it to $2, and then sit back and see the resulting consumer response,” she says.

But it’s not just about figuring out the right number; you need to understand consumer behavior as well. “You could run market tests every day,” says Avery, “but you also want to understand why consumers are acting the way they are. Understanding the why behind consumer behavior is critical to predicting how they will respond in the future.” That information will inform your marketing efforts. Therefore, smart marketers supplement any quantitative testing with qualitative research to get at the underlying reasons for consumer behavior.

It’s also important to keep in mind that understanding the price elasticity of demand for your product doesn’t tell you how to manage it. “As a marketer, I want to understand my current price elasticity and the factors that are making it elastic or inelastic, and then to think about how those factors are changing over time,” explains Avery. Ultimately, you want to stay relevant to consumers and differentiated from your competitors. Once you do that, you can adjust price up or down to better represent the level of value you are providing to your customers. Your current price elasticity is just one data point that helps you make those future decisions.

Read refreshers on net present value, breakeven quantity, debt-to-equity ratio, and cost of capital.

Companies Need an Option Between Contractor and Employee

Recently, a federal district judge in California began hearings in a case aiming to determine whether Uber drivers should be legally considered employees instead of independent contractors. Several other similar cases involving other service marketplaces (e.g. Postmates, Lyft, Washio) are also under way.

Whether Uber’s drivers and the workers for other service marketplaces fall on one side or the other of the dividing line between independent contractors and employees as currently construed by the law is for the courts to decide — not an easy task given that the U.S. Internal Revenue Service lists about 20 factors that should be taken into account.

However, the entire exercise of trying to fit today’s marketplace businesses into one of only two discrete categories is out of touch with reality and could lead to the disappearance of more efficient, intermediate business models.

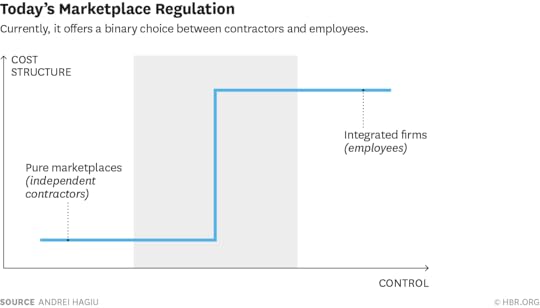

All marketplaces for products or services choose a position on a continuum defined by how much control they exert over the interactions or transactions they enable. At one end of the continuum are pure marketplaces, which exert little control over the terms of the transactions between independent suppliers or professionals and customers (e.g., eBay, Elance-oDesk, GrubHub-Seamless, OpenTable, Poshmark, RelayRides). At the other end of the spectrum are resellers that buy products from suppliers and resell or rent them on terms they completely control to customers (e.g. iTunes, Netflix, Zappos, Zipcar) and employers that hire professionals providing relevant services and entirely control how those services are delivered to customers (e.g., Infosys, McKinsey). Many firms have chosen to occupy intermediate positions along this continuum (e.g., Amazon.com, Lyft, Postmates, Uber).

The notion of control over supplier-customer interactions has many dimensions: price, equipment, how the relevant product or service is presented or advertised, how the product or service is delivered or performed, work schedule, and so on. What’s more, the stringency of the rules governing each of these dimensions can vary all over the map. As a result, there is a fine-grained spectrum of intermediate business models between pure marketplace and pure reseller or employer.

Marketplaces are driven to adjust the control dials for the various elements of their business model by a number of different factors: buyer or customer preferences for consistency across many sellers or suppliers, complementarities across products or services, seller or supplier heterogeneity, and so on. In particular, there may be very good efficiency reasons for choosing different levels of control across various elements (for details, see my recent work with Julian Wright here, here, and here). For example, Postmates has full control over the delivery price charged to customers, but its couriers can choose to use any vehicle they wish for performing their deliveries (including bicycles, cars, and trucks) as well as their work schedules.

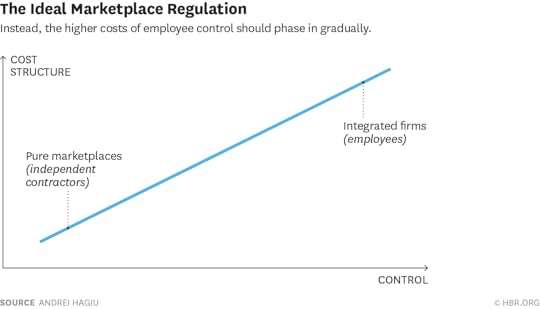

More control comes (as it should) with a higher cost structure. The precise shape of the increasing relationship between control and cost is determined in each industry by economic and legal factors and should, in principle, allow marketplaces to choose the position on the control continuum that maximizes the difference between the benefits of control and the costs associated with it.

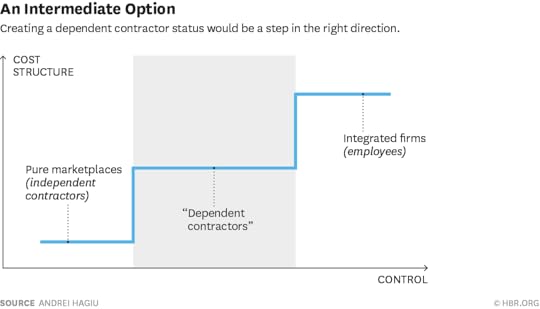

Here’s where the Uber case comes back into play. Service marketplaces today are forced to make a binary choice due to the nature of the cost-versus-control relationship they face. Their workers can either be independent contractors or employees: The latter option gives the firms full control over all relevant decisions but carries a 25% to 40% cost increase.

This is inefficient for two reasons. First, given the multiple dimensions of control described above, any attempt to draw a single bright line between independent contractors and employees seems arbitrary and impossible to do in a consistent way. This will inevitably lead to different and subjective interpretations from one industry to the next.

The second and more serious problem is that only allowing for two categories induces firms to run for the corners (pure marketplace or pure employer) in order to avoid getting caught in the uncertain middle. There is evidence that this trend is already underway: In the past two months, several firms (e.g., Luxe, Shyp, Sprig) have announced that they are converting all their workers from independent contractors into employees. This will likely eliminate many intermediate business models, which might be more efficient.

In an ideal world, firms would be able to choose among all possible intermediate steps between pure marketplace and pure employer — subject to the constraint that their costs will increase relative to some aggregate measure of the control exerted.

Needless to say, this is not practically feasible: There are just too many possible intermediate configurations, and it would be prohibitively complex to assign a different legal status to each of them. But it is not too much to ask for the introduction of at least one intermediate step such as “dependent contractors” for whom firms would cover some costs (e.g., expenses) but not others (e.g., social security).

Yes, there would still be the problem of drawing the boundaries between this status and the other two. Nevertheless, this would be a big step forward in terms of freeing firms to explore a variety of intermediate business models and arrangements with their workers.

August 20, 2015

Happiness Isn’t the Absence of Negative Feelings

Happiness feels intolerably elusive for many of us. Like fog, you can see it from afar, dense and full of shape. But upon approach, its particles loosen and suddenly it becomes out of reach, even though it’s all around you.

We put so much emphasis on the pursuit of happiness, but if you stop and think about it, to pursue is to chase something without a guarantee of ever catching it.

Up until about six years ago, I was fervently and ineffectively chasing happiness. My husband, Jim, and I were living in San Jose, California, with our two-year-old son and a second baby on the way. On paper, our life appeared rosy. Still, I couldn’t seem to find the joy. I always felt so guilty about my sadness. My problems were embarrassingly “first world.”

Then in September 2009, my world tilted. Jim fell severely ill. He was diagnosed with Swine Flu (H1N1) and West Nile (NOS), then Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS), due to his compromised immune system.

Jim never worried about death. I did.

When we were told Jim’s illness was letting up, that he’d won this round, we were relieved. When we were told Jim might not walk for some time – likely a year, maybe longer – we were worried. We knew this prognosis meant the end of Jim’s career as a pro lacrosse player. What we didn’t know was how we’d pay the medical bills, or how much energy Jim would have for parenting.

With 10 weeks to go until the baby arrived, I had very little time to think and reflect. Jim, on the other hand, only had time. He was used to moving at high speeds, both in life and on the field, so minutes passed like hours in the hospital. He was kept busy with physical and occupational therapy, but he was also in need of psychological support.

He put out a note to people in his social networks, asking them for reading suggestions that would help him to mentally heal. Suggestions flowed in. Books and audio tapes were delivered bedside with notes about how they’d “helped so much” after whatever difficulty this person had also experienced but overcame.

Jim would spend his days reading motivational books from Tony Robbins and Oprah or watching TED talks, like Jill Bolte Taylor’s Stroke of Insight, about the impacts of brain trauma. He would analyze spiritual books by Deepak Chopra and the Dalai Lama. Or review scientific research papers about happiness and gratitude written by researchers Martin Seligman, Shawn Achor, Sonja Lyubomirsky, and many others.

There was a repeated theme throughout all the literature – gratitude. It would weave in and out of the science, the true stories, and the drivers for success. Jim responded by starting a gratitude journal of his own. He got very thankful – thankful for the people who changed his sheets. Thankful for the family that would bring him hot meals at dinner. Thankful for the nurse who would encourage him and thankful for the extra time his rehab team would give on their own time. They once told Jim that they were only putting in extra time because they knew how grateful he was for their efforts.

He asked that I participate in his efforts, and because I wanted to help him to heal so badly and I was seeing how hard it was for him, I tried with all my efforts to be in a positive place when I came into his world inside that hospital room. I wasn’t always my best. I sometimes resented that I couldn’t break down – but after a while I started to see how rapidly he was getting better. And although our paths weren’t congruent, we were making it work. I was “coming around.”

It was shaky and scary, but when Jim walked out of the hospital on crutches (he stubbornly refused the wheelchair) only six weeks after he was rushed by ambulance to the ER, we decided there was something more to his healing than just dumb luck.

One of those early books that influenced Jim was Flourish, by Dr. Martin Seligman, psychologist and former President of the American Psychology Association. Seligman was responsible for defining the term “PERMA,” the root of many positive psychology research projects around the world. The acronym stands for the five elements essential to lasting contentment:

Positive Emotion: Peace, gratitude, satisfaction, pleasure, inspiration, hope, curiosity, and love fall into this category.

Engagement: Losing ourselves to a task or project that provides us with a sense of “disappeared time” because we are so highly engaged.

Relationships: People who have meaningful, positive relationships with others are happier than those who do not.

Meaning: Meaning comes from serving a cause bigger than ourselves. Whether a religion or a cause that helps humanity in some way, we all need meaning in our lives.

Accomplishment/Achievement: To feel significant life satisfaction, we must strive to better ourselves in some way.

We slowly brought these five tenets back into our life. Jim returned to Wilfrid Laurier University to research neuroscience, and we promptly started up Plasticity Labs to help teach others what we’d learned about the pursuit of happiness. As our lives came to include more empathy, gratitude, and meaning, I stopped feeling sad.

So when I see the recent skepticism directed at the positive psychology movement, I take it personally. Do these critics have a problem with gratitude? Relationships? Meaning? Hope?

Perhaps part of the problem is that we oversimplify happiness in our pop culture and media, which makes it easy to discard as unproven. As Dr. Vanessa Buote, a postdoctoral fellow in social psychology, put it in an email to me:

One of the misconceptions about happiness is that happiness is being cheerful, joyous, and content all the time; always having a smile on your face. It’s not – being happy and leading rich lives is about taking the good with the bad, and learning how to reframe the bad. In fact, recent research titled “Emodiversity and the Emotional Ecosystem,” by Harvard [researcher Jordi] Quoidbach, found that experiencing a wide range of emotions – both positive and negative – was linked to positive mental and physical well-being.

Not only do we tend to misunderstand what happiness is, we also tend to chase it the wrong way. Shawn Achor, the researcher and corporate trainer who wrote the HBR article “Positive Intelligence,” told me most people think about happiness the wrong way: “The biggest misconception of the happiness industry is that happiness is an end, not a means. We think that if we get what we want, then we’ll be happy. But it turns out that our brains actually work in the opposite direction.”

Buote agrees: “We sometimes tend to see ‘being happy’ as the end goal, but we forget that what’s really important is the journey; finding out what makes us the happiest and regularly engaging in those activities to help us lead a more fulfilling life.”

In other words, we’re not happy when we’re chasing happiness. We’re happiest when we’re not thinking about it, when we’re enjoying the present moment because we’re lost in a meaningful project, working toward a higher goal, or helping someone who needs us.

Healthy positivity doesn’t mean cloaking your authentic feelings. Happiness is not the absence of suffering; it’s the ability to rebound from it. And happiness is not the same as joy or ecstasy; happiness includes contentment, well-being, and the emotional flexibility to experience a full range of emotions. At our company, some of us have dealt with anxiety and depression. Some have experienced PTSD. Some of us have witnessed severe mental illness in our families and some of us have not. We openly share. Or we don’t – either way is fine. We support tears in the office, if the situation calls for it (in both sorrow and in laughter).

Today, perhaps looking for a “fresh angle,” some have even argued that happiness is harmful. The point of practicing exercises that help increase mental and emotional fitness is not to learn to paste a smile on your face or wish away your problems. It’s to learn to handle stressors more resiliently, just the way you wouldn’t run a marathon without training for it.

During my time with Jim in the hospital, I watched him change; in subtle ways at first, but then all at once, I realized that gratitude and happiness gave me a gift. It gave me Jim. If happiness is harmful – then I say, bring it on.

Companies Like Amazon Need to Run More Tests on Workplace Practices

A recent New York Times article about the business culture at Amazon triggered spirited reactions and a lot of media attention. Some “Amazonians” backed up the article’s description of a brutal, unrelenting workplace. Others — including CEO Jeff Bezos himself in a memo to his employees — questioned its accuracy.

I found the article to be an interesting read, especially in light of past discussions I’ve had with students or friends who have worked at Amazon. But beyond the question of how closely the story mirrored reality or not, it made me wonder why companies like Amazon, as far as I know, appear to choose work and management practices intuitively and stick with them without proper testing. But even if you’re adhering to principles of data-driven management, why not instead conduct controlled, randomized experiments to find out which practices are the best at promoting productivity, worker satisfaction, and innovation?

After all, companies seem well-versed in running all sorts of other experiments. Automotive firms develop concept cars. Food companies experiment with new foods and flavors. Retailers experiment with the placement of products and the design and atmosphere of their stores. Drug companies are built on conducting rigorous experiments to test the efficacy and safety of new medications. And at Amazon, experimentation with all sorts of things — different types of customer services, whether to advertise on television, whether to offer various types of free shipping and membership plans, and so on — has been happening since its beginning.

So it seems surprising that more companies don’t rigorously test work and management practices or policies that they are considering.

From talking to hundreds of executives in my classes and researching dozen of case studies on organizations in a wide range of industries, I’ve gleaned that there are a couple of reasons why they don’t. One is they do not want to give their employees the impression that the company is experimenting on them — or even worse, is trying to find way to squeeze the most out of them. Another is they worry about potential inequalities in the sense that employees who, by chance, ended up in the group subject to the new practice may benefit from it in terms of productivity, innovation, and work satisfaction, while those who are part of the “control group” (i.e., the group for which the practice is left unchanged) may not.

Partly because of these concerns, controlled studies have been conducted only as a result of collaborations between scholars and organizations. In my personal experience, these usually occur when an organization is suffering from a problem such as low productivity, low levels of employee engagement, or high turnover. But I have found that the benefits of conducting rigorous experiments on different work approaches, big and small, can be substantial. Here are some examples.

In one project, Adam Grant of the Wharton School and I examined whether showing appreciation for employees’ efforts makes any difference in terms of their productivity. We found that it does.

In a controlled experiment, we divided 41 fundraisers at a public U.S. university who were soliciting alumni donations into two groups: the thanked and the un-thanked. The former was visited by the director of annual giving, who thanked them by saying, “I am very grateful for your hard work. We sincerely appreciate your contributions to the university.” The other group received daily feedback on their effectiveness but no expression of gratitude from their director. The result? Fundraisers in the thanked group increased their weekly call volume 50%, on average, the week after the intervention took place. The director’s expression of gratitude strengthened the fundraisers’ feelings of social worth.

In another field experiment, Paul Green of Harvard Business School, Brad Staats of the University of North Carolina, and I examined whether the impact of expressing gratitude on productivity depends on who delivers the message. We randomly assigned 180 tomato-harvesting teams of a large food company who were working in fields in Central California to one of three conditions: the control group, the internal-beneficiary group, and the external-beneficiary group.

Each of the latter two groups watched a short video of either an internal beneficiary (such another worker in the field) or external beneficiary (a customer) articulating the impact of the harvesting employees’ work on them and then thanking the employees for that work. Over the course of the entire harvest season, we measured each team’s daily productivity (tons harvested per hour) for the period prior to the intervention and the weeks following it.

We found no significant increase in performance for those in the external-beneficiary condition. But teams in the internal-beneficiary condition, on average, produced almost 7% more per hour than did those in the control condition. Those employees could easily put a face on those who benefitted from their work and this inspired them to work harder.

Leaders could also test whether specific work conditions or policies affect workers’ performance.

Nick Bloom of Stanford University and his colleagues conducted a randomized experiment on working from home using a NASDAQ-listed Chinese travel agency called CTrip, which has 16,000 employees. Employees who volunteered to work from home were randomly assigned to either work from home or in the office, and their performance was monitored for the next nine months.

The results: Working from home led to a 13% increase in productivity, greater work satisfaction, and lower turnover. In fact, attrition among the home workers was 50% lower than among the control group. Overall, CTrip estimated it saved about $2,000 per year per employee working at home. Later, the agency allowed the employees in the experiment to choose if they wanted to work from home; their productivity increased by 22%.

Running controlled, randomized experiments on work and management practices may not always be feasible (when it is, here’s a five step-approach to follow). But it is a method that has proved effective in many contexts, from medical research to government policies and education. For example, sending parents of middle- and high-school students personalized text messages when their children did not hand in homework assignments increased homework completion by 25% as compared to children whose parents did not receive such messages, and parents were twice as likely to reach out to their children’s teachers.

Similar benefits could be gained by applying the logic of randomized experiments to white- and blue-collar work. This approach can help leaders identify best practices faster and at a low cost. In addition, it can help them focus on practices that not only enhance productivity and innovation but also work satisfaction — thus proving real benefits to both the organization and its members.

So next time you’re considering implementing a new practice or policy or wondering whether an existing one is actually succeeding in achieving its purpose, don’t take a chance. Conduct an experiment.

Deliver Feedback That Sticks

The secret of effective feedback is making it feel like the message is coming from an ally, not an adversary. Unfortunately, in my 17 years as an advisor to executive teams, I find that most managers’ anxiety and discomfort about delivering a difficult message inadvertently makes it come off as antagonistic, rather than supportive. A 2014 Zenger/Folkman study confirmed this problem when 43% of managers reported that giving corrective feedback is a “stressful and difficult experience.”

Unfortunately, if you’re stressed and anxious when delivering feedback, it will translate into poor communication (often abruptness or rambling), which will make it hard for the recipient to hear, understand, and apply the value of the information you’re delivering. Worse, your discomfort will be mirrored by the recipient and the interaction might actually erode trust his or her trust in you instead of enhancing it.

Before I tell you how to change this dynamic, take a moment to reflect on whether you make any of these common mistakes that can make feedback feel adversarial. First, do you stay at a safe distance to deliver feedback (e.g., behind a desk, or in the doorway of an office, giving the subtle impression that you’re planning an escape route)? Second, do you deliver your message and then leave quickly, to minimize your own discomfort with no regard for how the message landed with the recipient? Finally, do you make definitive statements (e.g. “You were rude.”) without being open to other explanations or perceptions (by phrasing it more openly, such as: “I found your tone harsh, what was going on for you?”). The statement feels like blame whereas the question leaves room for shared accountability.

Instead, you want to make feedback feel more like you’re invested in your colleague’s success. When you feel like you are helping someone, your anxiety will naturally decrease. So, before you even start the conversation, check in with yourself. Are you in the right state of mind to deliver effective feedback? Are emotions clouding your perception of the situation? How is your feedback a reflection of your own values and beliefs, and not just the behavior of your colleague? Don’t deliver the feedback until you can honestly say you’re ready to give it as an ally.

You and Your Team

Giving and Receiving Feedback

Make delivery–and implementation–more productive.

As you start the conversation, set the stage by sharing your support for the other person, and then orient her to the situation you’re talking about. Start with some background, “You know how important the Singapore project is and we really need to work together to succeed.” Then share the situation you’re giving feedback about, such as, “In our Steering Committee meeting on Monday, [insert your specific description of the behavior in question]”. Be crisp and objective; and be sure to remove judgment and subjectivity. Instead of “you were very disrespectful to me,” try “you interrupted me three times.” Don’t be afraid to comment on nonverbal behavior as well: “You turned away as I was speaking.” Ideally, you want your description to be so accurate that the only option is for the person to nod in agreement.

Then you can bring the subjective issues to the fore by sharing how your colleague’s behavior landed with you. Don’t make the mistake of attributing intent, just focus on the impact of the behavior. For example, “When you interrupted me three times, I think it reduced my credibility with the members of the other departments.” Using words like “think” and “feel” demonstrate that you are giving your interpretation rather than assuming your version is the truth.

Those three steps — orienting to the situation, describing the behavior, and sharing the impact — are the basic ingredients of effective feedback. But that’s not all you have to do. You don’t yet know if the message landed. You don’t know how the person interpreted it or how the feedback felt. You have no idea if the other person is going to do anything differently next time. Those are the issues that matter to an ally, so you aren’t done.

To make sure feedback is heard, understood, and applied, transfer ownership to the other person by asking an open-ended question. In the interruption example above, the question might be “How do you think that was interpreted by other members of the Steering Committee?” or “How might you leave more room for me to make my points?”

And that’s when you need to switch out of telling mode and into listening mode. You now get the opportunity to hear the other person’s truth. You experienced it as disrespectful, but that’s only one interpretation. What’s the other person’s version? An ally would be interested in both sides of the story. Was your presentation going on too long? Did you miss a few critical facts? Showing that you’re open to receiving feedback will go a long way toward increasing trust and credibility.

Make sure you go back and forth sharing perspectives and listening at least two or three times to ensure that you’re really hearing each other, increasing your understanding of yourselves and each other. “You thought I missed something, but what if I was getting to it on the next slide?” Don’t stop until you each have a clear vision for how a similar situation will play out better the next time. If the recipient says something like “Next time, I’ll ask if you’re going to cover something rather than interjecting,” you’ll know the feedback will stick.

Positive feedback is similarly improved when it is specific, when the impact of the behavior is shared, and when an open-ended question is used to test for understanding. For example: “In our meeting with the boss, when you disagreed with him and asked that he consider my suggestion, I felt like your credibility gave my idea a hearing it wouldn’t have had without you. What advice would you have for how I can continue to build my credibility with him?” That’s going to be a much more powerful exchange than just saying, “Thanks for doing that!”

Feedback is an investment in a colleague and a demonstration that you’re willing to endure a little discomfort to make your colleague and your relationship stronger. It only works if you deliver it in a way that demonstrates that you’re on the same team.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers