Duncan Green's Blog, page 98

March 27, 2018

The UK Labour Party sets out its stall on International Development – here’s why you should take a look

I’ve just been reading the UK Labour Party’s Green Paper on International Development (out this week). ‘Green  Papers’ are not about the colour (this one is actually red), but ‘designed to stimulate discussion and set the direction for the Labour Party’s programme for government.’

Papers’ are not about the colour (this one is actually red), but ‘designed to stimulate discussion and set the direction for the Labour Party’s programme for government.’

I work for an NGO, so a couple of minor gripes first: the party political point scoring is over-done (a bit of bipartisanship would have sounded a better note I think – for example, the Conservatives have done much better on aid volume than anyone predicted) and there’s a bit of hand waving in the section on ‘How Labour will Achieve This Vision’. But overall, there is a lot to applaud here – I hope it stimulates discussion, as intended, and not just within the UK.

Here’s some highlights.

‘Labour will wholeheartedly back the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). [It] will set a second twin objective for all international development work and spending: not only to reduce poverty but also, for the first time, to reduce inequality. Among other things, that will include measuring partner country progress against the Palma Ratio; evaluating all DFID work on the extent to which it reduces income inequality and other inequalities; and bringing like-minded countries together to champion faster action on inequality.

To serve the twin goals of reducing poverty and inequality, Labour will deliver on five key and connected priorities:

To serve the twin goals of reducing poverty and inequality, Labour will deliver on five key and connected priorities:

A fairer global economy

A global movement for public services

A feminist approach to development

Building peace and preventing conflict

Action for climate justice and ecology’

And there is substance beneath each of those five priorities. Here’s what it says on inequality:

‘To mainstream action on inequality across all DFID programme areas, we will take the following steps at the national level:

We will make reducing income inequality a key metric in the countries DFID partners with, adopting the Palma Ratio (the ratio of income between the richest 10% and the poorest 40%) and the Palma Premium (the extent to which the incomes of the poorest 40% are growing faster than the richest 10%).

All UK-funded international development projects and interventions will be evaluated on the basis of the extent to which they reduce inequalities, alongside other existing criteria.

We will go beyond simply measuring and addressing income inequality, and will work towards measuring and addressing inequalities in power and the exercise of rights to ensure that women and marginalised groups, such as indigenous communities, people living with disabilities and LGBTI people, are not left behind.

In order to promote these objectives, we will look to appoint a senior civil servant post to lead the government’s international work on reducing inequality.

We will complement these initiatives with global level advocacy:

In the first year of a Labour government, the UK will host an international summit bringing together likeminded countries and partners to champion ambitious action on inequality. Ideally, this will become an annual gathering to keep the issue as a top international priority.

We will encourage countries to sign up to more ambitious targets than those set in SDG 10, with the goal of halving their existing Palma Ratio by 2030 and achieving a Palma Ratio of 1 by 2040.

We will ensure DFID works with the Treasury and uses the UK’s influence to push for the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) to take action on inequality. That will include assessing the institutions’ policies to determine their impact on inequality, as part of a broader multilateral development review.

We will call for an international commission to explore the possibility of a global wealth tax, as proposed by economist Thomas Piketty.’

There is a similar level of specificity on the other four targets – well worth a skim.

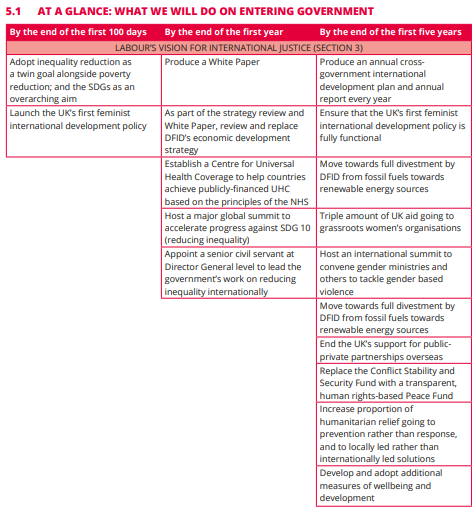

Finally, there is a nice, clear table of commitments + milestones for the first 100 days, year and five years of  government.

government.

I asked our in-house aid watcher, Gideon Rabinowitz, for a second opinion. He echoed my enthusiasm, but pointed to a few potential gaps:

‘How will they reform international aid processes and global institutions to give the south more of a say? There are perennial questions about which institutions should be at the centre of global governance and how the governance of existing Institutions should change that must be addressed.

What about going beyond health and education in terms of a sector focus? There are other services and sectors that are important and need more emphasis, including WASH and agriculture, which are strangely not mentioned at all

What will they do on inclusive economic development programmes to make them “people” focussed, including an emphasis on women’s economic empowerment, small scale businesses and informal sectors? There is very little here, and they could be emphasising a truly inclusive, poverty focussed and gender-focussed approach

Focus on the poorest countries – Will it retain an emphasis on aid volumes going to the poorest countries – especially Least Developed Countries – and reverse recent cuts to these countries? Not much discussion on this

Localising aid – There was little recognition that delivering more aid through Southern and local providers will require reforming DFID’s procurement, reporting and management systems, which currently work against these providers.’

I’d welcome other views.

March 26, 2018

International Donors and the exporting of 19th Century Poor Relief to developing countries

This post comes from

Stephen Kidd

,

Senior Social Policy Specialist at Development Pathways

Early last year, the UK’s Daily Mail newspaper expressed its concern that the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) was exporting ‘the dole’ – in other words, a welfare system for the poor – to developing countries through its financing of a range of ‘cash transfer’ schemes across Africa and Asia. The newspaper not only claimed that this money could be better spent in the UK but that DFID was creating ‘poverty traps:’ in other words, it was encouraging recipients to become lazy and stop working. It was similar to the oft-heard (if mistaken) critique by right-wing politicians in developed countries that poor people refuse to work and prefer to live off welfare benefits.

The UK’s support for cash transfers is part of a wider trend of growing investment in social security across many developing countries. As in high income countries – where large investments in social security have transformed societies since the middle of the 20th Century – these schemes have had significant positive impacts on recipients, reducing hunger, improving nutrition, facilitating higher school attendance, and supporting investments in agriculture and micro-enterprises.

However, the concerns of critics, such as the Daily Mail, should not be dismissed out of hand. The type of ‘welfare system’ promoted by many donors bears all the hallmarks of poor relief, a primitive form of welfare implemented by many developed countries between the 17th and 19th Centuries, when democracy was weak. Poor relief – as the name suggests – was targeted at those living in extreme poverty but paid for by the middle class, who were excluded from the schemes. Unconditional transfers were given to the so-called ‘deserving poor’ – in other words, those unable to work – while the working-age poor were regarded as ‘undeserving’ and forced to enter the workhouse (think Oliver Twist).

However, the concerns of critics, such as the Daily Mail, should not be dismissed out of hand. The type of ‘welfare system’ promoted by many donors bears all the hallmarks of poor relief, a primitive form of welfare implemented by many developed countries between the 17th and 19th Centuries, when democracy was weak. Poor relief – as the name suggests – was targeted at those living in extreme poverty but paid for by the middle class, who were excluded from the schemes. Unconditional transfers were given to the so-called ‘deserving poor’ – in other words, those unable to work – while the working-age poor were regarded as ‘undeserving’ and forced to enter the workhouse (think Oliver Twist).

Yet, as democracy strengthened, poor relief was increasingly opposed by most of the population – including the main taxpayers – and, instead, countries began building modern social security systems offering support across the lifecycle, addressing challenges such as old age, disability, childhood, widowhood and unemployment. Hence the growth of old age pensions, disability benefits and child benefits, which – as Figure 1 indicates – nowadays form the core of social security systems in almost all developed countries. These schemes received strong support, not only because they effectively reached the ‘poor,’ but because they also offered all citizens access to social security at the times in their lives when they most needed it.

Figure 1: Levels of investment in social security in high-income countries, disaggregated by target groups

Despite the criticism by neoliberals of ‘welfare’ for the poor, the core lifecycle social security schemes in developed countries continue to be strongly supported, with average spending at 12 per cent of GDP.

Despite the criticism by neoliberals of ‘welfare’ for the poor, the core lifecycle social security schemes in developed countries continue to be strongly supported, with average spending at 12 per cent of GDP.

The poor relief schemes promoted by donors in developing countries contrast sharply with the modern inclusive, lifecycle social security systems found in high-income countries. Not only are they targeted at the poorest – thereby excluding most citizens – their use of sanctions and workfare incorporates many of the characteristics of 19th Century poor relief.

This modern-day poor relief is highly flawed. Although programmes target the ‘poor,’ the majority of those living in poverty are excluded since it is impossible to identify the poorest households in developing countries. The selection of recipients appears arbitrary and is not understood by community members, often resulting in conflicts, broken relationships and, in some cases, violence. So, while the benefits of cash transfers are real for those lucky enough to receive them, large numbers of equally deserving people miss out.

However, the story of social security in developing countries does not stop with the poor relief favoured by donors. Many developing country governments are building their own social security systems, following the lifecycle model of developed countries, focusing initially on old age pensions, disability benefits and child benefits. The largest schemes are universal old age pensions which are now found in around 39 developing countries, including Bolivia, Lesotho, Mauritius, Georgia, Namibia, Nepal and Thailand, with Kenya planning to join the club in early 2018. A small number of countries have introduced child benefits, including Mongolia which provides children with around $10 per month. The level of investment can be relatively high: South Africa invests 3.4 per cent of GDP in its system of old age, disability and child benefits; investment in Georgia is now more than 6 per cent of GDP, mainly in an old age pension; and, even Nepal, one of the world’s poorest countries, invests almost 2 per cent of GDP in lifecycle benefits. In contrast, spending on poor relief schemes is rarely more than 0.4 per cent of GDP, and usually much less.

In contrast to donor-supported poor relief, inclusive lifecycle schemes in developing countries are popular, as evidenced by their relatively high budgets. This is because they are offered to everyone rather than an arbitrarily selected group of ‘the poor.’ In countries with democratic electoral systems, their popularity can play a key role in helping politicians win power. Furthermore, the impacts of the lifecycle schemes are much greater than poor relief: so, while the Philippines’ Pantawid poor relief programme reduces the national poverty rate by less than 5 per cent, the decrease in South Africa is 42 per cent (see Figure 2). And, of course, since most inclusive, lifecycle schemes are open to everyone, they are much more effective than poverty targeted schemes in reaching the poor.

Figure 2: Impacts on the poverty rate across age groups by the Philippines Pantawid programme and South Africa’s social grants

Unfortunately, some donors have attempted to undermine the more progressive schemes introduced by developing country governments, calling instead for poverty targeting. For example, the IMF, World Bank and Asian Development Bank have recently forced Mongolia to introduce targeting into its highly successful universal child benefit while the World Bank proposes the targeting of Namibia’s universal old age and disability benefits, despite recognising their significant impacts on poverty and inequality.

Other donors, in contrast, are, occasionally, supporting more progressive, universal social protection. For example, in Uganda, for the past six years DFID and Irish Aid have funded a universal old age pension in 14 of the country’s districts. The scheme is almost certainly DFID’s most successful cash transfer scheme and has been highly effective in reducing poverty, tackling child undernutrition, helping children attend school and stimulating local economies. It is also very popular, with strong support from Parliament and the national population, and is frequently discussed and promoted in the media.

In contrast to poor relief, such schemes are popular and likely to generate support for investment among the governments of developing countries, in particularly where democracy is strengthening. Investment in schemes such as old age, disability and child benefits will also strengthen social cohesion in fragile states, boost economic growth, reduce poverty and tackle inequality.

The lesson is clear. Donors should stop undermining universal schemes in developing countries and get behind national governments, supporting them in building modern, effective and popular social security systems rather than imposing on them 19th Century poor relief, which has already been shown to fail in developed countries.

March 25, 2018

Links I Liked

Definitions of politics, from Tanzanian kids. Take your pick, but I’m with Hayley. Ht January Makamba

New IMF report: ‘The share of countries at elevated risk of debt distress, e.g. Ghana, Lao PDR, & Mauritania, or already unable to service their debt fully has almost doubled to 40% since 2013.’ Plus lenders are more diverse this time around, so it’s harder to fix debt crises

In Mali’s Bamako, in the suburb of Yirimadio, ‘Child mortality rates have dropped to the point where they are now the lowest in sub-Saharan Africa – an achievement that may all be down to knocking on doors.’ The cost is $8 per person per year

The first website that tracks whether the world is making progress towards the SDGs.

Do you follow more men than women on twitter? What about your followers? Check your stats here. And you can do it for other twitter accounts too. ht Alice Evans.

Comic Relief to ditch white saviour stereotype appeals

Where to next on corruption research? Blue sky thinking from Dieter Zinnbauer.

A spot of unparliamentary behaviour in Kosovo. Most striking thing is how they all just sit there when the tear gas goes off – were they comatose already? ht Amichai Stein

March 23, 2018

What is really stopping the aid business shifting to adaptive programming?

Jake Allen, Head of Governance for Sub Saharan Africa at the British Council, left such a well argued, sweetly  written comment on

Graham Teskey’s recent post

that I thought I’d post it separately

written comment on

Graham Teskey’s recent post

that I thought I’d post it separately

“For every complex problem, there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.”

(HL Mencken said something similar to this, just not as pithily)

With each piece that I read on the topic of how we do development differently, many of which are on this blog, I’m finding myself getting increasingly frustrated, and feeling like this whole line of thought has gone down a cul-de-sac. We’ve been saying the same things for quite a while now, but things haven’t really changed: our development isn’t that different; our thinking and working not that much more political; our programmes not hugely more flexible nor adaptive. Some thoughts:

Old Dog, Old Tricks

There’s an implicit assumption that programmes in the bad old days were rigid, technocratic and uncontextualised, and now we are on the other side of the Rubicon, are the polar opposite. I suggest that programmes were pretty much as adaptive and politically aware then as they are now – for the day-to-day, on-the-ground work, it’s basically impossible not to have been. Maybe you think the bureaucracy and reporting were different, and we used to have to just report on the results we initially set out to achieve, but that’s all changed now? To you I say, you clearly haven’t done a lot of reporting lately. For sure, there’s often now a report heading that says, ‘how were you adaptive?’, but unless the programme’s been explicitly designed as a Doing Development Differently lab rat, you’ll still have to jump through the reporting hoops.

What did we expect? You can’t have all but a few variables remain exactly the same, and expect that injecting some good intentions and a lot of writing was going to change a whole huge system and its embedded culture. Development institutions are, by and large, political bureaucracies. Their cultures and practice need to be understood in this context, with a recognition that these aren’t going to change much or fast, so we need to adapt within the current structures.

The Low Politics of High Ideals A large part of the development world believes, or wants to believe, or at least finds it convenient to claim, that what we do is apolitical. Now I realise at this point there’s probably a whole load of people who’ve sprayed their coffee on the monitor in rage – and for sure there are loads of people and organizations who really are attempting to put the politics and power back into development. What I think is missed is the big picture of aid/development, and therefore the programmes designed within it, as being absolutely tied into big-P Politics: we are operating in other countries and doing things that directly attempt to influence how that country is run. We are only there because we are allowed to be there by their governments, but that license is granted because of the Political consensus and the trade-offs (and sometimes trade) that has been accepted and agreed.

A large part of the development world believes, or wants to believe, or at least finds it convenient to claim, that what we do is apolitical. Now I realise at this point there’s probably a whole load of people who’ve sprayed their coffee on the monitor in rage – and for sure there are loads of people and organizations who really are attempting to put the politics and power back into development. What I think is missed is the big picture of aid/development, and therefore the programmes designed within it, as being absolutely tied into big-P Politics: we are operating in other countries and doing things that directly attempt to influence how that country is run. We are only there because we are allowed to be there by their governments, but that license is granted because of the Political consensus and the trade-offs (and sometimes trade) that has been accepted and agreed.

Too Big to Not Fail

What is a programme? It’s lots of things: an idea; a Theory of Change; a vehicle for values; a bureaucratic entity; a thing valued at an amount of money; a way of changing the world. What it’s not is perfect, or a plan for delivery that should be stuck to.

It’s too big to not fail, but actually it’s also too small and too short. It’s too big because actually programmes end up almost always being collections of smaller actions and interventions, which tend to be much more successful because it’s easier to work with smaller geographies: less people, you can see the boundaries of systems; practically more doable; managers can actually hold the whole thing. But rarely do they cohere back to a single entity that forms a consistent whole (other than in the beautiful fictions of the annual report). They’re too small because even a programme of £50m is a drop in the bucket of a national economy. They’re too short because the lofty ideals and impact they aim for are generational.

I think that what underlies this is that we are all involved in a process of attempting to shift the world towards a set of accepted norms and values.

And if we see it like that, then ‘the programme’ starts to make sense: it’s an expression of the striving towards shared values, which can best be delivered at a local level, and we just have to accept the bureaucratic burden this comes with. It’s our job. But it’s the job of the leaders in the development sector to make and defend this case. A while back Jonathan Glennie made a case for reframing aid as ‘foreign public investment’. The detail and language aren’t important here; what matters are the ideas that investing in other countries is inevitable, essential and valuable and as public investment should cut across a range of sectors and objectives. It also touches on another important point: that any investment fund would not put pressures to get money out the door above making sure that spending is effective. Development agencies, if operated on a fund basis, would be able to stop, change and retrench funds with ease, making them more effective at delivering their objectives. I’d be interested to hear views on this.

values, which can best be delivered at a local level, and we just have to accept the bureaucratic burden this comes with. It’s our job. But it’s the job of the leaders in the development sector to make and defend this case. A while back Jonathan Glennie made a case for reframing aid as ‘foreign public investment’. The detail and language aren’t important here; what matters are the ideas that investing in other countries is inevitable, essential and valuable and as public investment should cut across a range of sectors and objectives. It also touches on another important point: that any investment fund would not put pressures to get money out the door above making sure that spending is effective. Development agencies, if operated on a fund basis, would be able to stop, change and retrench funds with ease, making them more effective at delivering their objectives. I’d be interested to hear views on this.

It’s the Smart, Stupid

I return sometimes to DFID’s Smart Rules, which I think were the best recent attempt to get an organisation to change its culture and foster better programming.

People seem to have focused a lot more on ‘Rules’ than ‘Smart’. Smart is about taking all the rules and systems and, even if briefly, putting them to one side and being able to ask ‘what are we trying to do, and how do we do it?’ I should say at this point that I’ve met plenty of people who embody this approach, but they remain the exception – as a colleague says ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’. Of course you still have to fill the forms and please the bosses and ministers – as I say, recognising the politics and the bureaucracy is essential.

Smart is also only as good as the least smart part of the process. Smart doesn’t work if donors try and subcontract it to someone else, but don’t do it themselves. You can’t tell a programme to be smart if you’re then not going to give it any of the actual ability to do so (yes I’m looking at you, donor in an African country who’s demanding adaptive programming at the same time as enforcing rigid adherence to pre-planned budgets! Not one of my programmes I should add.)

All this isn’t entirely fair to Graham and his original piece. He wasn’t talking about the whole problem, just a bit of it. But this ‘bit of it’ approach – it’s about MEL, it’s about learning, it’s about capacity etc – ends up missing the bigger points and stops us making the changes that will really have an effect.

March 22, 2018

Bruised but better: the stronger case for evidence-based activism in East Africa

Wrapping up Twaweza week, Varja Lipovsek (left) and Aidan Eyakuze reflect on the event that

Wrapping up Twaweza week, Varja Lipovsek (left) and Aidan Eyakuze reflect on the event that  has provided the last week’s posts

has provided the last week’s posts

It was a stormy couple of days in Dar es Salaam. First, it is the rainy season, so the tent in which we held our meeting flapped and undulated over our heads like a loose sail. More importantly, we crammed the tent with more than fifty sharp, articulate, thoughtful, and driven individuals who for two days pored over, picked apart – and also suggested how to reassemble – the main areas of work and future strategic direction for Twaweza East Africa. It was our Ideas & Evidence event, and boy was it a good ride!

We are Twaweza: an initiative working on enabling citizens to exercise agency, promoting governments to be more  open and responsive, and improving basic learning for children in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda. Since our start in 2009, we still hold at our core the democratic ideal that lasting change is driven by the actions of motivated citizens. Granted – that core idea was felt to have much more traction ten years ago, when it seemed (naively in retrospect) that the world order was generally tending towards a greater embrace of rights and democratic values, more openness and a deeper connection between citizens and government.

open and responsive, and improving basic learning for children in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda. Since our start in 2009, we still hold at our core the democratic ideal that lasting change is driven by the actions of motivated citizens. Granted – that core idea was felt to have much more traction ten years ago, when it seemed (naively in retrospect) that the world order was generally tending towards a greater embrace of rights and democratic values, more openness and a deeper connection between citizens and government.

A short decade later, the world has changed. The speed and depth of the pivot to authoritarianism by governments and to cynicism by citizens are alarming. Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, the countries where Twaweza works, have not been immune to these dark developments. Kenya’s constitutional and electoral crisis in 2017, Uganda’s scrapping of age limits for its presidency in the same year, and Tanzania’s steady slide into use of restrictive legislations and the use of deadly force by incumbent leaders and their agents (both official and otherwise) are the tip of the iceberg.

So there we were, in a tent full of activists, researchers, policy wonks, and a few government folks, from East Africa and far afield, talking about what we have learned over the last decade, what this all means in the current environment, and where we ought to go next. Rather than summarise the very rich conversations, we want to highlight key navigation points that have started to crystalize for us and which will be instrumental in shaping our new strategy.

The necessary fuss about ‘evidence’. There was an impassioned debate running through the event about what constitutes evidence, including Duncan’s own musings on this theme. But why are we becoming so shy about producing and using evidence? Almost as if we are falling prey to the defeatist “post-truth” notion, as if there is something shameful – or at least quaintly old-fashioned – in intellectually rigorous thought. We understand and support the clarification that the search for evidence does not just mean conducting randomized controlled trials (i.e., boiling out the context until there’s nothing left but a few hard kernels of “truth”). For us, the search for evidence is being in the thick of it: trying to unpack a complex problem into various components (such as, why do the public education systems in East Africa continue to fail to achieve even basic level of learning among our children?), and then examining those components with the most appropriate tools, while remaining aware of the context within which the problem is steeped.

The necessary fuss about ‘evidence’. There was an impassioned debate running through the event about what constitutes evidence, including Duncan’s own musings on this theme. But why are we becoming so shy about producing and using evidence? Almost as if we are falling prey to the defeatist “post-truth” notion, as if there is something shameful – or at least quaintly old-fashioned – in intellectually rigorous thought. We understand and support the clarification that the search for evidence does not just mean conducting randomized controlled trials (i.e., boiling out the context until there’s nothing left but a few hard kernels of “truth”). For us, the search for evidence is being in the thick of it: trying to unpack a complex problem into various components (such as, why do the public education systems in East Africa continue to fail to achieve even basic level of learning among our children?), and then examining those components with the most appropriate tools, while remaining aware of the context within which the problem is steeped.

This brings us to another key theme that arose, which was the call for a tight(er) link between evidence and action. Indeed, every single research study we conduct is directly linked to a program, or initiative we are implementing. Very many of them are evaluations, prompting Duncan to quip that we seem to be producing lots of evidence of what does not work. True, but as James Habyarimana put it, a “zero point” is a supremely important piece of insight, particularly when advising government policy implementation. If we can continue to demonstrate that the decisions taken in East Africa about how to improve learning outcomes are not yielding results, then perhaps we stand a better chance of turning the discussion towards the evidence of what does seem to work. This resonates with Rosie McGee’s presentation about the effectiveness of civic tech: 4+ years and 187 grants later, we can say what tech will not do for governance. It can be really frustrating, but it is also infinitely better than insisting we have solutions when we don’t. Such brutal honesty may allow us to nudge that discussion further.

Putting the human back into the design. How one communicates the various types of evidence is supremely  important, starting by being very clear to whom you want to communicate it to, and understanding what that person (or group) is likely to respond to, depending on what are the motivations and barriers around the issue. The insights from Togolani Mavura on what government really listens and responds to were really great – though as our colleague Ben Taylor pointed out, what the government doesn’t like listening to is as important as what it likes; e.g., independent media is an often “disliked” but crucial voice in the public dialogue. Twaweza engages with government along multiple tracks. One is the shaping of public discourse through data, including data journalism and opinion polling. This is the track that seeks to hold a mirror up to government claims, fully aware that sometimes the picture won’t be pretty. Another track, however, is a deeply embedded role which we are just starting to take on in Tanzania, where we are working closely with two key ministries to implement a teacher motivation program (whose power to boost learning outcomes we showed) through government’s own systems. In other words, we have been going with the grain when the going is our direction of travel. But we have also been ready to go against the grain, when the grain sucks (thanks Alan and Ruth for these insights!).

important, starting by being very clear to whom you want to communicate it to, and understanding what that person (or group) is likely to respond to, depending on what are the motivations and barriers around the issue. The insights from Togolani Mavura on what government really listens and responds to were really great – though as our colleague Ben Taylor pointed out, what the government doesn’t like listening to is as important as what it likes; e.g., independent media is an often “disliked” but crucial voice in the public dialogue. Twaweza engages with government along multiple tracks. One is the shaping of public discourse through data, including data journalism and opinion polling. This is the track that seeks to hold a mirror up to government claims, fully aware that sometimes the picture won’t be pretty. Another track, however, is a deeply embedded role which we are just starting to take on in Tanzania, where we are working closely with two key ministries to implement a teacher motivation program (whose power to boost learning outcomes we showed) through government’s own systems. In other words, we have been going with the grain when the going is our direction of travel. But we have also been ready to go against the grain, when the grain sucks (thanks Alan and Ruth for these insights!).

There are no shortcuts to being grounded. We may be starting to understand what prompts governments to engage, but we seem to know even less about what compels citizens to engage with evidence and take action (see Ruth Carlitz’s post). But beyond the research findings, the activists in the room were unanimous that if we are serious about this, there is no substitute for good old fashioned community level engagement (in the search for both  evidence and for solutions). We heard loud and clear from Tamasha Vijana, African Youth Development Link and Shahidi wa Maji about the importance of participatory action research, understanding the localized needs, opportunities, barriers and incentives faced by the citizen groups in focus, and also by local government as it (tries to) respond. We are fortunate to already be working with a group of grounded activists and look forward to deepening some of these relationships and learning from them.

evidence and for solutions). We heard loud and clear from Tamasha Vijana, African Youth Development Link and Shahidi wa Maji about the importance of participatory action research, understanding the localized needs, opportunities, barriers and incentives faced by the citizen groups in focus, and also by local government as it (tries to) respond. We are fortunate to already be working with a group of grounded activists and look forward to deepening some of these relationships and learning from them.

So what next for Twaweza? We are currently deep in the drafting of the new strategy, and would welcome the opportunity to share it in the near future. For now, here is the direction of travel:

Twaweza’s core mission remains to make sure that the democratic space in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda does not shrink further, and perhaps even regains some lost ground. We shall employ and deploy all manner of evidence, tactics and communication and persuasion tools to this effect.

The centrality of citizens as the energy that drives pro-democratic change has been put squarely back on Twaweza’s agenda. This includes generating grounded, participatory evidence, creating a tighter link between evidence and action at local levels, connecting with local governance, and engaging with “street-level” civil servants.

Our desire for scale remains ambitious, but it has evolved. No longer just the thin, horizontal scale aiming to simply touch many (sometimes known as the “spray and pray” approach); it will be more ‘vertical’, starting with deeply grounded understanding of needs, barriers and opportunities around a specific governance problem, deliberately percolating the issue up the system, to connect the various levels of governance, from wards to districts and counties, to national policy. We have much to learn here from friends and colleagues such as Dejusticia in Colombia, and grounded academic groups such as ARC and GOV/LAB.

Within the realm of democratic rights, the quality of basic education occupies a central role (for so many reasons: because we have a youth bulge, because it’s the first encounter between citizens and state, because no country has ever really progressed without investing substantively in public education…), and we will continue to push for improvements in education as a right in and of its own, and as a space to demonstrate the possibilities of pro-social engagement between citizens and state.

Overall, we emerged a little bit bruised (which is good) but mostly energized (even better!) from the two day storm in the tent. The sharp, honest and thoughtful discussions allowed us to examine the core essence of what Twaweza stands for, what we do, and how to do it better.

We are deeply grateful to everyone who gave us their time, energy and insights.

March 21, 2018

Can religion play a role in evidence-obsessed governance strategies? Lessons from Tanzania

Next up in the Twaweza series,

Aikande Clement Kwayu

reflects on the development sector’s blind spot with  religion

religion

When it comes to social change, religion is a double-edged sword. It can be both a force for good and/or for bad. The world-wide positive contribution by religious organisations in providing public services such as health and education is undisputed. The role of religion in areas of human rights, democracy, accountability and governance has been inconsistent. However, that does not reduce the role that religious organisations and leaders have played in demanding and promoting good governance, including defending human rights, democratic ideals, and civic space for citizen participation. Religious groups and leaders often possess moral authority to speak out against injustice. Religion often incubates and facilitates some of the strongest civil society arrangements in many developing countries.

So why has it been so difficult to incorporate the positive role of religion into the mainstream development agenda? My PhD research (2012), which analyzed the relationship between DFID and Faith Groups, found that DFID treated faith groups as exactly the same as other NGOs and/or charities. Any relationship was based purely on a pragmatic rationale, just like with any other development NGO. There was no special consideration given to religious organisations’ unique ability to reach sensitive areas that many NGOs could not access, such as in the 2011 famine crisis in Somalia. Theories of modernisation and the promotion of secularism in development discourses rendered religion a sensitive and private, perhaps even slightly embarrassing, matter, unsuitable for discussion in ‘grown-up’ aid circles.

Religion as a driver of change (sorry, couldn’t resist).

Occasional efforts to change this by the International Development Industry have been half-hearted and short-lived. In early and mid-2000s, the World Bank tried to bring religion onto the development agenda through the creation of the World Faith Development Dialogue. Yet the momentum did not last. The growing appreciation of religion as a civil society actor and subsequent academic interest in the same did not soften development partners’ rigidity in engaging with (or failing to) religious institutions. The question remains, why?

Could the budding obsession with evidence- and results-based programming partly explain the persistent reluctance to involve religion in governance and other development agendas?

Two weeks ago, at the Twaweza Ideas and Evidence conference, there was a rich discussion on what counts as evidence in governance. There were questions and debates on the role of Randomized Control Trials (RCTs) and to what extent such research can help in bringing change. The various research presentations and discussions underlined the evidence-obsessed ambience in the international development space. The unfortunate thing is, evidence is often equated with numbers. Quantified evidence seemed to be more revered than the qualitative variety.

This matters because one of the barriers that development partners find in working with religion is the difficulty of measuring impact. The impact of religion in influencing people’s thinking and actions, for example, is profound yet hard to measure. So are the roles of religious leaders in influencing change. Development organisations that are evidence–obsessed may find it difficult to work with religion out of an unconscious fear of dealing with something that is considered sensitive, private and that cannot always be evaluated on the basis of numbers. Yet there is an adequate literature that has shown the role of religion in influencing and shaping norms around political ideas and economic attitudes. Norms shaped by religion have also been shown to be persistent over time and can play a role in economic and development performance. In the real world, ‘faith-based policy making’ may be more common than the evidence-based variety, but that is neither recognized nor discussed in the aid and development bubble.

measuring impact. The impact of religion in influencing people’s thinking and actions, for example, is profound yet hard to measure. So are the roles of religious leaders in influencing change. Development organisations that are evidence–obsessed may find it difficult to work with religion out of an unconscious fear of dealing with something that is considered sensitive, private and that cannot always be evaluated on the basis of numbers. Yet there is an adequate literature that has shown the role of religion in influencing and shaping norms around political ideas and economic attitudes. Norms shaped by religion have also been shown to be persistent over time and can play a role in economic and development performance. In the real world, ‘faith-based policy making’ may be more common than the evidence-based variety, but that is neither recognized nor discussed in the aid and development bubble.

In Tanzania, religious institutions have done great work on several crucial areas of governance. An interfaith committee carried out effective advocacy against unfair tax regimes. In Chapter 12 of this recent book, I analysed the efficiency of the interfaith committee advocacy strategy on extractive industry with its two groundbreaking publications in 2008 and 2012. The voices of religious leaders in calming the situation in the 2013 protests in Mtwara in relations to gas and new gas pipeline should also be recognized. Of late, religious leaders have been outspoken against the diminishing civic space in the country. Yet we still do not see active incorporation of religious groups as key governance stakeholders and strong civil society representatives by development partners in the country.

In these testing times for democracy and shrinking civic space, it is high time for development partners to rethink their strategies and find ways through which the strengths and potentials of religious organisations and leaders can be marshaled for the common change we all want to see.

Previous Posts in this series:

When does Tech → Innovation? Here’s what 178 projects tell us

Which Citizens? Which Services? Unpacking Demand for Improved Health, Education, Roads, Water etc

How can researchers and activists influence African governments? Advice from an insider

Can Evidence-based Activism still bring about change? The view from East Africa

March 20, 2018

When does Tech → Innovation? Here’s what 178 projects tell us

Next up in Twaweza week, a realists’ guide to tech and development.

I’m basically a grumpy old technophobe who can’t even manage Excel, and whose hackles rise whenever geewhizz  geeks pop up and claim that the latest digital gizmo (blockchain, clicktivism or whatever) is going to usher us all into the promised land. I dislike the implicit individualism, the blind eye to issues of power and politics, the way politicians latch onto tech solutions as an apparently cost-free way to sound modern without actually challenging or changing the status quo.

geeks pop up and claim that the latest digital gizmo (blockchain, clicktivism or whatever) is going to usher us all into the promised land. I dislike the implicit individualism, the blind eye to issues of power and politics, the way politicians latch onto tech solutions as an apparently cost-free way to sound modern without actually challenging or changing the status quo.

So I was delighted when Rosie McGee, a ‘scholar activist’ (her description) from IDS, presented her paper (with Duncan Edwards, Colin Anderson, Hannah Hudson and Francesca Feruglio) on the results of 178 small grants to tech projects funded under the Making All Voices Count accountability programme. Over 4.5 years, the grants went to projects for innovation, scaling up, tech hubs and research, mainly in six countries across Africa and Asia (South Africa, Kenya, Philippines, Indonesia, Ghana and Tanzania).

The paper presents its main findings as 14 messages. The first is one that governance wonks don’t need to be told, but techies apparently need to hear: there is no magic bullet

‘Message 1. Not all voices can be expressed via technologies

The rest are grouped into four clusters

Applying technologies as technical fixes to solve service delivery problems

Message 2. Technologies can play decisive roles in improving services where the problem is a lack of planning data or user feedback

Message 3. Common design flaws in tech-for-governance initiatives often limit their effectiveness or their governance outcomes

Message 4. Transparency, information or open data are not sufficient to generate accountability

Applying technologies to broader, systemic governance challenges

Message 5. Technologies can support social mobilisation and collective action by connecting citizens

Message 6. Technologies can create new spaces for engagement between citizen and state

Message 7. Technologies can help to empower citizens and strengthen their agency for engagement

Message 7. Technologies can help to empower citizens and strengthen their agency for engagement

Applying technologies to build the foundations of democratic and accountable governance systems

Message 8. The kinds of democratic deliberation needed to challenge a systemic lack of accountability are rarely well supported by technologies

Message 9. Technologies alone don’t foster the trusting relationships needed between governments and citizens, and within each group of actors

Message 10. The capacities needed to transform governance relationships are developed offline and in social and political processes, rather than by technologies

Message 11. Technologies can’t overturn the social norms that underpin many accountability gaps and silence some voices

Applying technologies for the public bad

Message 12. A deepening digital divide risks compounding existing exclusions

Message 13. New technologies expand the possibilities for surveillance, repression and the manufacturing of consent

Message 14. Uncritical attitudes towards new technologies, data and the online risk narrowing the frame of necessary debates about accountable governance.’

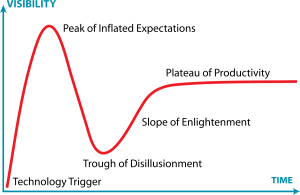

What seems to be happening is a classic hype curve. The optimism of the Arab Spring and various largely fanciful

So where are we now on tech for development?

accounts that it was all down to twitter/Facebook/telegram etc are now coming under scrutiny via experience and research. What I like about the paper is that it points the way beyond a simple trashing of the hype, to the areas in which tech holds most promise of helping the struggle for accountability, such as ‘improving services where the problem is a lack of planning data or user feedback’ (message 2) or where they can act as a general multiplier/support for other strategies (messages 5-7).

But (reverting to grumpy old technophobe) – let’s be clear. Tech is not an alternative ‘short route’ to accountability. That requires deep engagement with issues of power, trust and social norms, where a smart app or whizzy online petition is only ever going to play a subsidiary role. And, as Tim Berners-Lee broadside against the online giants, the dark shadow of the downside of tech is growing ever greater. The misguided optimism of the Arab Spring seems a long way off these days.

Last word to the authors in their conclusion:

‘Looking back through four-and-a-half years of operational and research work on the assumptions that underpinned Making All Voices Count’s theory of change at the outset, it is clear that expectations about growth in access to the internet and other technologies were excessive. Seen in relation to an end goal of improving the accountability and responsiveness of governance, the contribution of tech-enabled, individual, direct voice has been weak compared to the importance of collective, organised processes that combine online and offline approaches. Put differently, the contribution of tech innovation has been less than that of tech-aware social innovation in making voices count. That tech solutions have made only a moderate contribution is due in part to design and implementation flaws, for which today’s stock of knowledge provides abundant evidence, and to which it offers more than sufficient remedies. But it is also partly due to the complexity of the task of making governance accountable, which was under-recognised by many at the outset.’

Previous Posts in this series:

Which Citizens? Which Services? Unpacking Demand for Improved Health, Education, Roads, Water etc

How can researchers and activists influence African governments? Advice from an insider

Can Evidence-based Activism still bring about change? The view from East Africa

March 19, 2018

Links I Liked

How a Viral Eye Roll broke the silence on China’s heavily censored web

How a Viral Eye Roll broke the silence on China’s heavily censored web

Stephen Hawking had pinned his hopes on ‘M-theory’ to fully explain the universe – here’s what it is

If you live in Brixton, love London, or are a generally sentient human being, watch Molly Dineen’s new film: ‘a unique insight into being black in Britain in 2018, told through the story of renowned record shop owner and music producer, Blacker Dread.’India and Pakistan are literally ringing each other’s doorbells at night and then running away. ht Iain Marlow

Oxfam update:

Oxfam appoints former UN official to head independent commission on sexual abuse and exploitation

“The danger of this donor reaction to the Oxfam scandal is that other NGOs with less robust procedures will shy away from being open about abuse.”

China’s cities are tackling air pollution at high speed. Here’s how.

China to set up a new International Development Cooperation Agency – more like DFID than USAID.

Tim Harford’s guide to how to read stats

Liverpool FC’s Mohamed Salah’s (frequent) goal celebrations provide a guide to British Muslimness. When Salah scores, the Liverpool fans sing ‘If he’s good enough for you he’s good enough for me. If he scores another few then I’ll be Muslim too’.

London Mayor Sadiq Khan reading out his tweets starts off funny, then rapidly gets very grim indeed

March 18, 2018

Etymological map of Africa

Etymological map of Africa. I particularly like ‘He Who Talks too Much’ (Lalibela. Ethiopia), ‘It has Sunk’ (Dodoma, Tanzania), and ‘Chief Who never Sleeps’ (Harare. Zimbabwe) ht Ranil Dissanayake

March 16, 2018

Which Citizens? Which Services? Unpacking Demand for Improved Health, Education, Roads, Water etc

Next up in the Twaweza series is this post from Ruth Carlitz of the University of Gothenburg. Please read and comment on the draft paper she summarizes here.

Ruth Carlitz Göteborgs universitet

Clean water. Paved roads. Quality education. Election campaigns in poor countries typically promise such things, yet the reality on the ground often falls short. So, what do people do? Wait for five years and “throw the bums out” if they fail to deliver? For many people, the stakes are too high, and they may have well-grounded doubts about the ability of democracy to deliver anything other than a new set of bums. It’s worth asking, then, what other actions citizens take to improve their lives.

Building on Richard Batley and Claire Mcloughlin’s work on service characteristics as well as my own research on the politics of service delivery in East Africa, I’ve identified various factors affecting the likelihood that people will mobilize for improved public services. These include how frequently people experience (problems with) a given service, their ability to pay for private alternatives, and their expectations about the likelihood of improvements in response to their actions.

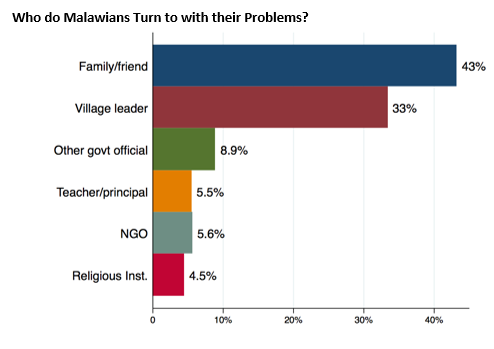

To better understand such dynamics, I’ve begun exploring data from the Local Governance Performance Index survey implemented in Malawi in 2016. The survey asked respondents what problems they faced with a range of issues related to service delivery. Those reporting problems were then asked if they turned to someone for help with the problem, who they turned to and why, whether and how the problem was resolved, and whether they were satisfied with the response.

The figure depicts the main actors people turn to for help. In general people are most likely to turn to family members, friends or neighbors, followed by village leaders. Higher-level government officials are in a distant third place, despite the fact that they may hold much more sway when it comes to influencing outcomes on the ground.

The figure depicts the main actors people turn to for help. In general people are most likely to turn to family members, friends or neighbors, followed by village leaders. Higher-level government officials are in a distant third place, despite the fact that they may hold much more sway when it comes to influencing outcomes on the ground.

Next, we can look at how demographics affect the likelihood of people turning to different actors. Wealthier respondents and those with more education are less likely to turn to friends and family, perhaps because they have the resources to solve problems on their own. This may also reflect their ability to exit the public system (e.g., going to a private clinic when the public health system falls short). On the other hand, such people are more likely to turn to other government officials, and to school officials – suggesting they may feel more empowered to approach authority figures. Gender also matters. Women are less likely to turn to village leaders or any other government officials but more likely to turn to school officials with their problems – perhaps because they are more involved in their children’s education. Finally, civic skills (having attended a community meeting in the past year) is positively associated with seeking assistance from all actors.

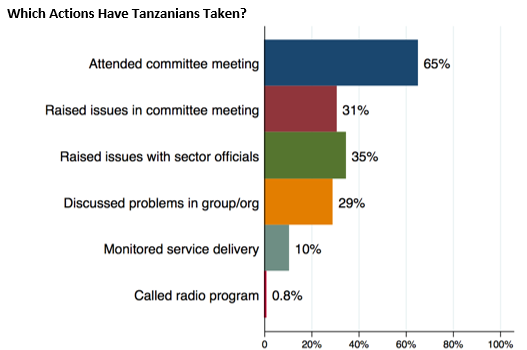

In neighboring Tanzania, recent survey data finds that nearly a quarter of all respondents took action to improve service delivery (education, health, or water) in 2015. The chart on the right unpacks what people meant by “taking  action.” Overall, Tanzanians were more likely to attend committee meetings than take any other action. We also see that people were generally more likely to raise issues in smaller group settings rather than more publicly (e.g., by calling in to the radio). Finally, note the low proportions of respondents who report tracking things like drug stockouts, teacher attendance, or water point functionality – suggesting that the focus of many citizen monitoring initiatives (report cards, etc.) may not jibe with people’s normal way of doing things.

action.” Overall, Tanzanians were more likely to attend committee meetings than take any other action. We also see that people were generally more likely to raise issues in smaller group settings rather than more publicly (e.g., by calling in to the radio). Finally, note the low proportions of respondents who report tracking things like drug stockouts, teacher attendance, or water point functionality – suggesting that the focus of many citizen monitoring initiatives (report cards, etc.) may not jibe with people’s normal way of doing things.

When it comes to which citizens are taking action, we see similar results to Malawi. Specifically, civic skills are associated with increases in all forms of action-taking. Women on the other hand are less likely to take action across the board. Wealth matters, though only for actions related to education and health. Respondents who are more informed (listen to the radio more frequently) are also more likely to take actions of all kinds, though it is interesting to note that education levels do not demonstrate any relationship with action-taking. Finally, internal efficacy (belief in one’s own ability to make effective demands) is positively associated with actions related to all sectors, while external efficacy (expectations of government responsiveness to such demands) only seems to matter for water.

The paper I prepared for Twaweza’s recent Ideas & Evidence event digs into these relationships in greater detail. While preliminary, it highlights the importance of paying attention to the ways in which service delivery differs  across and within sectors. This is critical when it comes to supporting initiatives to enhance the efficacy of citizen engagement, which, despite having generated mixed results to date, continue to benefit from considerable amounts of funding.

across and within sectors. This is critical when it comes to supporting initiatives to enhance the efficacy of citizen engagement, which, despite having generated mixed results to date, continue to benefit from considerable amounts of funding.

As a final thought, practitioners may wish to consider which aspects of service delivery might be amenable to influence. For instance, establishing community groups could create greater scope for users to share information and coalesce around shared needs. Such groups will likely be more effective when they build on existing institutional channels rather than set up parallel structures. This implies taking time to learn about people’s existing routines for problem-solving, and supporting those strategies which seem to be generating more results. In other words, working with the (local) grain.

Public goods and services can also be distributed in such a way that reduces the availability of exit options. For example, a recent study of handpump distribution in Kenya advises against clustering, as people will be more motivated to maintain their local water points if they don’t have ready alternatives.

Finally, it may also be possible to shift expectations about the possibility of improved service delivery — in particular, providing information in a way that facilitates bench-marking. For instance, learning that everyone in the neighboring district has water piped into their houses when you are spending hours each day collecting buckets from a far-away tap could serve as a tipping point

Where does this leave us? For those of us who earn our keep by cranking out conference papers and journal articles (and the occasional blog) there is much work to be done. Hopefully, such work can help to guide donors when it comes to making impactful investments, and practitioners when it comes to making actual impact.

Previous Posts in this series:

How can researchers and activists influence African governments? Advice from an insider

Can Evidence-based Activism still bring about change? The view from East Africa

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers