Duncan Green's Blog, page 99

March 15, 2018

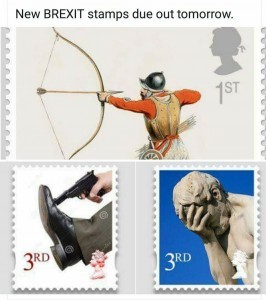

How can researchers and activists influence African governments? Advice from an insider

One of the highlights of the Twaweza meeting was hearing from Togolani Mavura (left), the Private Secretary to former  President Kikwete (in Tanzania, ex-presidents get a staff for life, not like in the UK where they have to hawk themselves round the after dinner speaking circuit). Togolani has been worked across the various policy levels of the Tanzanian goverment, and his talk reminded me a similarly witty presentation by the UK Foreign Office’s Babu Rahman. Here’s some highlights:

President Kikwete (in Tanzania, ex-presidents get a staff for life, not like in the UK where they have to hawk themselves round the after dinner speaking circuit). Togolani has been worked across the various policy levels of the Tanzanian goverment, and his talk reminded me a similarly witty presentation by the UK Foreign Office’s Babu Rahman. Here’s some highlights:

‘Government is not homogeneous – people think differently in every office, every ministry. You guys are asking yourselves how do you get buy in: How to take pilots to scale? How to translate best practices into impact? You wonder ‘what the hell, here are the facts, why are they not responding?! Here are some tips:

Know the System:

You need to understand who holds the key – Activists spend a lot of time trying to convince the wrong guys. There are those you need to convince, but some officials or politicians just need to be informed, since they have no decision-making influence – you just need their nod.

Which pathway to follow is another catch – parliamentary, thinktank, lobbying officials or civil servants – it depends on the particular policy that you are proposing. Some policies can only be imposed on the executive by the parliament; others emanate from the civil service; for others, you just go to the political party. The National Executive Committee of the ruling party in Tanzania has policy-making powers and can direct the government to act, so get your idea into the party manifesto ahead of the elections.

If, after years of trying, the government has not bought your idea, it is probably because:

– your idea or proposal is good but not good enough compared to those submitted by others

– you have not addressed the core interest, the self-interest, the ‘nerve centre’ of the individual policy makers or core interests of the respective institution e.g. your proposal may render that particular institution irrelevant or threaten their source of revenue

– your idea may just be ahead of its time. In 2010, there was a suggestion for free Universal Primary Education, but  the government said it wasn’t possible. In 2015, it adopted free UPE up to Secondary School – the time just hadn’t been right earlier on.

the government said it wasn’t possible. In 2015, it adopted free UPE up to Secondary School – the time just hadn’t been right earlier on.

For example, take Twaweza’s idea for paying teachers ‘cash on delivery’ of results. From the policy maker’s point of view, teachers are not just teachers; they are a political pressure group. If you introduce something and it goes bad, the government could fall. It is risky to do experiments on teachers’ welfare. The proposal also needs to be particularly convincing because it has to be scaled up across the country. Tanzania is a unitary system, not a federal system, so any programme has to be introduced in all parts of the country. And if it goes wrong, it can boomerang and trigger an electoral backlash for the party in power.

Learn to see through their eyes:

Government has its own ways of looking at things. Officials are wired to manage stability and predictability and are averse to disorder and instability. Budgetary process is institutionalized and centralized. Individual decision makers and institutions have no freedom to alter the budget passed by the parliament. Therefore, any proposal that you bring which has budgetary implications is likely to be rejected. It is wise therefore to spell out how it can best be financed. Policy makers are humans, and some of them have prejudices – if your proposal has a load of foreigners behind it – they will say ‘the whole idea is alien’!

Messengers are very important. A civil servant will disclose to someone they feel comfortable with. You need to know what they are thinking, know the other side. That gives you the leeway to build something that gets support from both sides.

Use their data:

Governments run through lots of myths. Many of their positions and beliefs are outdated, but have been passed down through generations until they lose their true meaning and become dogma, protected by phrases like ‘this is how it is done around here.’ Like those ‘reuse with an economy label’ signs on government envelopes – that was put on there during some economic crisis in the 60s or 70s, but it’s still on the envelopes!

Data and evidence can overcome such myths, but try and use government data – policy makers are more comfortable when you use data they know and trust. Don’t worry much about the sharpness of the data. Even if the numbers are not as good as your own, or other independent sources, it’s not a big deal. Yours isn’t a debate about whose statistics are right, but how to influence change. The devil is not in the numbers, but in the narratives!

Timing is Everything:

Master the importance of timing. The Government has its own internal clock and internal calendar. It has moods too. It will buy certain proposals in the run up to elections; others in its first term (if they help get it re-elected); still others in the second term (for its legacy).

The Chinese character for ‘crisis’

All governments go through crises at times. For the lobbyist, crisis is an opportunity. There is no better time to lobby for your cause than when the government is struggling to recover from a scandal. Governments are like humans, after a crisis you want to hear good news. It is looking for something to announce, some good news to divert attention from the scandal. That is when to go to politicians with your idea, but the proposal should not be the same subject as the scandal – it should be a distraction.

Get smarter at Lobbying:

You need to up your game on the art of lobbying. It’s no good just presenting a document with lots of data. That’s not enough. Policy makers are overstretched and overwhelmed. Parliament, donors, politicians and people all want a piece of them. Out of around 500,000 civil servants in Tanzania, maybe only 1-2,000 are actively engaged in the policy-making process. They are overwhelmed by papers. If they do not heed to your wonderful proposal it is not because they are dumb, clueless or indifferent, simply, they are over stretched. You need to find other, creative ways to get their attention and harness their interests.’

Great stuff. It’s interesting to compare this with Babu Rahman’s talk – Togolani seems to place much greater emphasis on understanding the inner workings of policy making, whereas Babu focussed more on punchy, clear presentation. Any other differences?

March 14, 2018

Can Evidence-based Activism still bring about change? The view from East Africa

Spent last week defrosting in Tanzania, at a fascinating conference that produced so many ideas for blogs that,  even if all the promised pieces don’t materialize, we’re going to have to have a ‘Twaweza week’ on FP2P. Here’s the first instalment.

even if all the promised pieces don’t materialize, we’re going to have to have a ‘Twaweza week’ on FP2P. Here’s the first instalment.

I’m buzzing and sleep deprived after getting back from an intense two days in Dar es Salaam, reviewing the strategy of one of my favourite NGOs. Twaweza works in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda, and is in my experience unique in its deep and simultaneous commitment to civic activism, social change at scale and rigorous research, focusing in particular on improving the lamentable quality of primary education in East Africa.

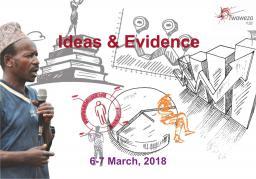

I first got involved with them back in 2013, at a point where their research had found that their hugely ambitious efforts had produced precious little in the way of results. But instead of burying the findings, they summoned people from all over the world to discuss them. Respect. That was where I first came upon my all-time favourite cartoon (see  left). And I’ve been trying to understand ‘then a miracle occurs’ ever since.

left). And I’ve been trying to understand ‘then a miracle occurs’ ever since.

We had an exchange of blog posts in 2013, and Varja Lipovsek and Rakesh Rajani, both at Twaweza at that point, summed up where they wanted to go next:

move beyond the ‘Magic Sauce’ of access to information as a driver of change

Political economy analysis as standard

Focus on the interstices between citizen and state

Understand the barriers to poor people’s agency

Think about Positive Deviance

Iterate and adapt

Don’t give up on scale

Fast forward to 2018, and I think this checklist is still where a lot of the more interesting work on accountability and governance is at.

But the world has changed since 2013, not least in the area of accountability and civil society participation. There has been a flowering of thinking and practice on institutional reform and governance, but there is a weird disconnect: the ‘Doing Development Differently’ and ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ types working on institutional reform seem barely on speaking terms with organizations like Twaweza and the whole ‘open government’ and transparency movement, even though they are often thinking and acting on parallel tracks. That weakens the thinking and practice of both groups: DDD people are often far too dismissive of civil society as a bottom-up driver of change; transparency and accountability people aren’t thinking hard enough about how to understand and ‘work with the grain’ of informal institutions and states.

More generally, the zeitgeist has not been kind to Twaweza’s original project, built on evidence and support for civil  society. Governments and policy makers are more ready to dismiss evidence in these post-truth times, and civil society is under siege in dozens of countries (including all 3 of Twaweza’s). Which leads to two big questions:

society. Governments and policy makers are more ready to dismiss evidence in these post-truth times, and civil society is under siege in dozens of countries (including all 3 of Twaweza’s). Which leads to two big questions:

To what extent should Twaweza focus on defending civil society space, even if it currently looks like a losing battle in many countries? Or (like the International Budget Partnership, which it resembles in some ways), should it further diversify its partners to non-CSOs, eg working more with private sector, or faith leaders, the judiciary or sympathetic politicians and officials?

I had an even bigger question on its understanding and use of ‘evidence’. Twaweza’s commitment to it is laudable, but it’s main value so far seems to have been in proving what doesn’t work – an impressively transparent process of unlearning and questioning initial assumptions, coming up with new ideas and then testing them in turn. That was particularly the case at the 2013 soul-searching. Since then, it feels like some of the engagement with academics has slightly lost its mojo – the researchers are burrowing away on questions such as what makes voters switch parties, that are of great interest to political scientists, but not obviously relevant to Twaweza. The gulf between the researchers and the activists at the seminar seemed wider this time, with the activists more sceptical about the value of some of the research, and insisting that what constitutes ‘data’ had to emerge from communities. I got very excited about updating Robert Chambers – from ‘handing over the stick’ to ‘handing over the click’ (I’m shallow like that). What’s the best thing to read on bottom up construction of data?

But I still think Twaweza should stick to its ambitions on scale (Rakesh originally got my attention by saying Twaweza didn’t want to do anything that wasn’t going to reach at least 2 million people). So if evidence and access to information aren’t enough to trigger the elusive miracle, are there any alternatives? Two emerged during the course of discussions:

Spot the outlier

Positive Deviance: Twaweza is using PD to identify high performing schools in poor areas of all 3 countries. It’s a fascinating attempt to apply one of my favourite ideas on the ground, and Sheila Wamahiu has promised to write a post for FP2P on the experience.

Social Network Analysis: I was interested in this recent LSE post about applying SNA in fragile states, and wondered if Twaweza could get to scale by identifying the nodal individuals, communities or organizations on any given issue, and targeting them – after all, as Malcolm Gladwell described years ago in Tipping Point, marketing departments have been doing it for years.

These are big challenges and big ideas, but if any organization has the ambition and the smarts to pull it off, it’s Twaweza.

Anyway, I’ve run out of space. Lots more to come. Twaweza want right of reply to this post, 8 people attending the seminar promised to write blogs on their work, and I have at least two others of my own to churn out – a very productive couple of days!

(Full disclosure: Twaweza paid for my flights and hotel)

March 13, 2018

Links I Liked

Huge crop experiment in China: Decade-long study involving 21 million smallholders shows how evidence-based approaches can improve food security and reduce GHG emissions. ‘As a result of the intervention, farmers were $12.2 billion better off.’

Cancer kills more people in developing countries than AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis combined. But, with Africa receiving only 5% of global funding for cancer prevention and control, the disease is outpacing efforts to contain it.

Six academic writing habits that will boost productivity. (the seventh is not wasting time on links round-ups…..)

More jargon and acronyms please

More jargon and acronyms please

Top 10 zombie statistics. This is largely UK-centric – time for a development version? Here’s a start

Malaria Must Die. Brilliant new 2 minute film from Aardman (of Wallace and Gromit fame). Strikes just the right balance between wit and message ht James Whiting

March 12, 2018

A Caring Economy: What role for government?

Anam Parvez (left), Oxfam’s Gender Justice Researcher and Lucia Rost, research consultant,

Anam Parvez (left), Oxfam’s Gender Justice Researcher and Lucia Rost, research consultant,  introduce their

new paper

on

gender equitable fiscal policies.

introduce their

new paper

on

gender equitable fiscal policies.

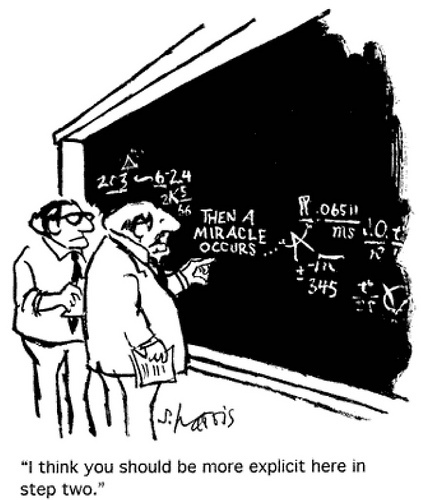

In economics we are taught that there is no such thing as a free lunch. Even if something appears to be free, there are always costs – to you and/or society. What is striking is that mainstream economists fail to recognize that this applies just as much to the lunch that has been prepared out of love by your mother, as it does to the unappetising conference sandwiches that cost you your entire day at an academic seminar.

Women around the world often spend many hours a day and on average 3 times as much as men (In India 10 times) on unpaid care and domestic work, which includes activities such as cooking, collecting water, caring for the elderly and children. This is an investment of time that we all benefit from, through healthy families, societies and economies. Yet often, unpaid care and domestic work is not considered to be ‘real’ work and is seen to fall outside the boundaries of the “market”. It continues to be invisible in terms of how we understand the economy, what we count as productive and valuable and therefore how fiscal policies get formulated and their impacts analysed.

30 years ago, Marilyn Waring wrote a seminal book critiquing the national system of accounts, showing how macroeconomic policies embedded in such a flawed understanding of the economy have often undermined women’s rights and exacerbated gender inequalities. Studies have since revealed the high cost of the invisibility and ignorance of care, often borne by women and girls: to their health, their choices and the time they have available for leisure, education, paid work and other opportunities.

30 years ago, Marilyn Waring wrote a seminal book critiquing the national system of accounts, showing how macroeconomic policies embedded in such a flawed understanding of the economy have often undermined women’s rights and exacerbated gender inequalities. Studies have since revealed the high cost of the invisibility and ignorance of care, often borne by women and girls: to their health, their choices and the time they have available for leisure, education, paid work and other opportunities.

There are reasons for optimism, however – unpaid care and domestic work is finally moving up international agendas. The SDGs, unlike their predecessors, include a target calling for the recognition, reduction and redistribution of care work. More development practitioners are also starting to acknowledge that care is not just the responsibility of household members, but that governments can and should play an important role in meeting care needs. For the last 5 years, Oxfam’s WE-Care (Women’s Economic Empowerment and Care) initiative has collected data on care work in six developing countries.

So what does the evidence tell us about what governments should invest in?

Our new paper uses the 2017 Household Care Survey (HCS) findings from Uganda and Zimbabwe to explore the relationship between public investments in care related infrastructure and services and better outcomes for society.

Water!

When water sources are distant and/or of poor quality, women are often the ones who suffer: In Uganda, women we

Invisible Work?

interviewed spent up to 6 hours a day collecting water. Read that last sentence again and apply it to your own life! Our research shows that access to an improved water source (something other than a natural source) is associated with women spending 4 hours less on care work in Zimbabwe (to put this in perspective that is approx. 1560 hours they save in a year – roughly equivalent to one full time job in the UK) and 2 hours less in Uganda. Women with access to improved water also spend 1 to 2 hours less time multi-tasking on care activities (e.g. cooking with a baby on your back). Not just women, but girls too benefit: For both countries, we find that girls with access to water spend more time on sleeping and leisure and in Zimbabwe more time studying.

Electricity and Childcare

We also find that investments in electricity are associated with boys spending more time studying, most likely because electric light in the evening makes studying easier. Girls and boys spend less time on paid work if the household uses a childcare facility. However, we find that access to childcare and electricity are not associated with women spending less time on care work. This may seem strange since a recent UN Women report shows how important childcare is in freeing up women’s time. Perhaps women’s freed time is being spent other care tasks they were unable to do before. Or that given the considerable time women spend multitasking, one service alone doesn’t reduce the hours women spend on care. This is clearly something to explore further.

The wider implications of investments in care

Fiscal policies that manage to effectively reduce the levels and intensity of women’s care work also have broader implications for women and children’s welfare and for the wider economy

Benefit to women’s health: we find that more than 1/3 of women reported an injury or illness due to their unpaid care work and over half of these women said the harm was long lasting.

Improvements in care of children: due to heavy workloads, a significant minority of women (24% in Zimbabwe and 18% in Uganda) reported that in the last week, they had left a young child alone knowing there was no one looking after them.

Reductions in gender inequalities in paid work: women interviewed in Zimbabwe and Uganda spend over two hours less a day on paid work than men.

Six hours a day

Social norm change is also needed

While we find that good quality and accessible public infrastructure is necessary for reducing women and children’s heavy unpaid care workloads, on its own it appears to be insufficient for redistributing care work between men and women. Social norms that dictate that care work is “women’s work” or isn’t as skilled or valuable as paid work must be explicitly addressed by public institutions, advertising companies and cultural leaders among others. In Uganda, we find that in households where women and men say they approve of an equitable distribution of care work between spouses, care hours are more equitable.

Linking all this to the economy means that in order to achieve transformative change in women’s lives, unpaid care work needs to be a major public policy concern. Fiscal policy – in particular public spending–is a powerful tool that governments can use to reduce and redistribute more fairly the time women spend on unpaid care work. Ultimately, such policy making can be a step towards building a ‘human economy’ where responsive governments put in place equitable and fair benefits for every woman, man and child to live decent lives. But when budgets are tight and the priority is a narrowly defined GDP target, how can we encourage public spending on care? How can we address women’s unpaid care work holistically and in the context of social norms? Many questions remain and we would be interested in hearing your thoughts.

Download the paper and infographic: Gender-equitable Fiscal Policies for a Human Economy: Evidence from Uganda and Zimbabwe

Read more about Oxfam’s WE-Care initiative

Download the 2017 WE-Care research report: Infrastructure and equipment for unpaid care work: Household survey findings from the Philippines, Uganda and Zimbabwe

March 8, 2018

Challenging humanitarianism beyond gender as women and women as victims

Dorothea Hilhorst (right), Holly Porter (centre) and Rachel Gordon (left) introduce a highly topical new issue of the Disasters journal

(open access for the duration of 2018). This post first appeared on the ISS blog.

(open access for the duration of 2018). This post first appeared on the ISS blog.

At the United Nations (UN) World Humanitarian Summit (WHS) in May 2016, ‘achieving greater gender equality and greater inclusivity’ was identified as one of the five key areas of humanitarian action. The WHS wanted this to be a watershed moment that would spark a shift toward systematically meeting the needs of women and girls and promoting their role as active decision-makers and leaders.

After more than four decades of discourses on ‘gender in development’ and a substantive history of evolving international law and practice on women, peace, and security, the WHS marked an important declaration that the humanitarian aid field takes gender seriously. ‘Gender’ too often has been understood as synonymous with ‘women and girls,’ neglecting questions of agency, vulnerability, and the dynamic and changing realities of gendered power relations.

The focus on sexual violence has brought significant attention to some of the challenges that many women face, but has also reproduced a generalized image of women as victims. That idea was already well-embedded in classic views of conflict that see men as aggressors and combatants and women as non-combatant victims. While this depiction is grounded in sad empirical realities, it leads to a kind of tunnel vision that only centres on the suffering of women, viewing them as the primary victims and primarily as victims. The victim discourse furnishes a rationale for providing women with direly needed assistance, and in fact, women themselves are often keen to play the role of victim to become eligible for aid, backgrounding other aspects of their identity, including their (political) agency. Nonetheless, this focus is problematic in obscuring other realities in which men and women assume different and more complex roles.

Humanitarian programmes often seek the participation of women because they (we) are considered the more caring gender. Women are often targeted for aid as a proven means to improve the wellbeing of children, foster more peaceful conditions, and prevent the misdirection of resources. In the process, international aid often aims to also structurally improve the position of women. This is why UNICEF considers engaging women in service delivery as a positive step towards promoting women’s rights, and describes it as the ‘double dividend of gender equality’. While well-intentioned, all of these assumptions pertaining to women’s position and role in humanitarian responses have problematic aspects. These dimensions are what we aimed to unearth and explore in our new special issue of the journal Disasters on gender, sexuality and violence in humanitarian crises.

The journal, not the organisation…..

What about men?

The attention on women as aid recipients drowns out the voices that are asking: ‘What about men?’ (not to mention other marginalised gender categories like LGBT communities). Men also cope with specific vulnerabilities, often related to their gender. They are much more often at the receiving end of lethal violence than women, and are frequently victims of sexual violence. When aid is channelled through women, it can lead to a situation where men’s vulnerability is forgotten, or where men feel emasculated or disenfranchised from their traditional social roles (see, for example, the contribution by Holly Ritchie to the special issue). Such situations can have a variety of consequences, ranging from mental health problems among men to the (violent) re-assertion of men and masculinities.

Gender as relations of power

The articles in the special issue bring another layer to this discussion that all too often boxes men and women into stagnant categories. By prioritising these categorical issues that ascribe and assume particular traits as specific to men and women, debates may miss the mark regarding gender as relations of power that, like everything else, are cast into disarray during humanitarian crises. It is well-established that gender roles are interwoven with other social identity markers, and that these intersectional gender relations are, moreover, deeply ingrained in and reproduced by the working of all institutions in society, ranging from the personal between men and women to the working of cultural values, geopolitics, governance practices, and religion. In creating the special issue, we asked: how do humanitarian responses interact with these myriad aspects of gender and other interrelated social identities? And how do humanitarian responses thus affect gender relations?

Persistence and change

The special issue testifies both to the persistence of gender relations as well as their propensity to change. Julian  Hopwood, Holly Porter, and Nangiro Saum found a drastic reported change in everyday gender relations in Karamoja, Northern Uganda, especially where women’s material resource bases were enhanced, but they raise questions about whether such change is enduring. The economic empowerment of women may spill over positively into other domains of life, or contrarily may undermine goodwill towards women’s positions and bring about a violent backlash against them (and against humanitarians)—or both. Likewise, well-meaning interventions can have adverse effects, as Luedke and Logan found in South Sudan, where a narrow focus on conflict-related sexual violence and recycled (although well-intentioned) responses thereto by international organisations were not only unhelpful, but also ran counter to and undermined local norms that might have protected women.

Hopwood, Holly Porter, and Nangiro Saum found a drastic reported change in everyday gender relations in Karamoja, Northern Uganda, especially where women’s material resource bases were enhanced, but they raise questions about whether such change is enduring. The economic empowerment of women may spill over positively into other domains of life, or contrarily may undermine goodwill towards women’s positions and bring about a violent backlash against them (and against humanitarians)—or both. Likewise, well-meaning interventions can have adverse effects, as Luedke and Logan found in South Sudan, where a narrow focus on conflict-related sexual violence and recycled (although well-intentioned) responses thereto by international organisations were not only unhelpful, but also ran counter to and undermined local norms that might have protected women.

The instrumentalisation of gender

A final layer that complicates the analysis of and interventions in gender relations is that gender as an issue is often instrumentalised for different purposes. Gender has firmly become part of the high politics of international relations. More locally, an interest in the position of women can, for example, obscure attempts of a government to firm up its grip over local authorities, as Rebecca Tapscott found in another contribution to the special issue on Northern Uganda. Likewise, Hilhorst and Douma found that the responses to sexual violence in the DRC were instrumentalised for various purposes by a large range of actors.

Treading carefully

What do these different layers mean for humanitarian action, apart from standing as a reminder that paying attention to women should not result in turning a blind eye to vulnerability and agency of other gender categories? The special issue highlights the dynamic and entangled nature of gender relations, and how humanitarian and political attention to gender adds additional layers to the complexities of gender relations in crisis environments. Aid can often do lots of harm. This does not mean that gender objectives should be abandoned, but that aid actors need to tread carefully and seriously invest in their capacity to carefully monitor the intended and unintended effects of programming on gender relations.

Dorothea Hilhorst is Professor of Humanitarian Aid and Reconstruction at the international Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University.

Holly Porter is Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at the Institute of Development Policy and Management (University of Antwerp) and Conflict Research Group (Ghent University). She is also Research Fellow at the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa of the London School of Economics and Political Science. She is the author of After rape: Violence justice and social harmony in Uganda (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Rachel Gordon is an independent research consultant on gender and humanitarian aid, and was formerly an SLRC Researcher and the SLRC Gender Team Leader, Feinstein International Center (Tufts University)/Overseas Development Institute.

March 7, 2018

From sexual harassment to everyday sexism – a feminist in Oxfam reflects on International Women’s Day

This guest post is by

Nikki van der Gaag

, Oxfam’s

Director of Gender Justice and Women’s Rights

This International Women’s Day feels different to any other for many working in the aid and humanitarian sector.

Normally, it is a day where, like so many others, we celebrate women’s individual and collective achievements. But the reports of the appalling sexual exploitation of Haitian women by Oxfam staff in the aftermath of the earthquake in 2011, and the subsequent emerging widespread scale of sexual harassment and abuse across the sector, have made it hard to feel like celebrating.

Instead, for many of us, it is a time for self-reflection, for listening and speaking out, and for recognising what many feminists already knew – that in big institutions such as the UN and INGOs and other charities, men still hold the power as much as in the media or Hollywood, the Church or the judiciary.

Berta Caceres

As we have seen very clearly, Haiti was not an isolated incident. We know that sexual exploitation by the powerful of the powerless is all too common in our own sector as elsewhere. For example, in the past 12 years there have been almost 2,000 allegations of sexual abuse and exploitation by UN personnel. As early as 2004, Amnesty International reported that under-age girls were being kidnapped, tortured and forced into prostitution in Kosovo. The U.N.’s department of peacekeeping in New York acknowledged at that time that “peacekeepers have come to be seen as part of the problem in trafficking rather than the solution.”

Much of the media focus recently has been on the behaviour of individuals, and on the contexts in which they have exploited the most vulnerable in the most appalling way, and the way in which this has been handled. But there is another factor that has been implicit rather than explicit, and that is the mix of gender and power.

As Antonio Guterres, the United Nations Secretary General, said at the start of last year’s 16 days of activism against gender-based violence: ‘Violence against women is fundamentally about power. It will only end when gender equality and the full empowerment of women is a reality.’

All over the world, women continue to face abuse, violence, discrimination and sexual harassment. The horrifying statistic that one in three women worldwide face violence from an intimate partner is often quoted but changes very little from year to year.

Many brave women die for speaking out – Jo Cox in the UK, Gauri Lankesh in India, Berta Caceres in Honduras.

Gauri Lankesh

And thousands more are raped, trafficked, sexually exploited or harassed.

This will not end until we address the roots of gender inequality and the many factors beyond gender that keep such power relations in place – among them race, ethnicity, class, geography, age, ability, and sexual orientation.

For change to be visible and felt, there needs to be a structural as well as a cultural revolution. Within our own organisations, we need to ensure that women feel safe to speak out, and that everyone knows that abusive and bullying behaviour will not be tolerated and that any allegations will be responded to quickly and clearly.

We need to make sure that when perpetrators are caught they are punished. Robust and accountable codes of conduct, investing in safeguarding teams as well as good safeguarding policies, a register of referees, are all vital if we are to see change. While Oxfam has made substantial improvements to our safeguarding since 2011, we recently announced a 10 point action plan to further strengthen and improve these measures, including the creation of an Independent Commission to review our culture and practices.

More women in positions of power are a part of the solution, though not all of it. Women still only make up 22.8 % of parliamentarians globally. And a UN study of women’s participation in peace processes found that women make up only 9% of negotiating delegations, 4% of signatories, and 2% of chief mediators.

This is despite the evidence that Analysis of 181 peace agreements signed between 1989 and 2011 found that…‘peace processes that included women as witnesses, signatories, mediators, and/or negotiators demonstrated a 20% increase in the probability of an agreement lasting at least two years. This increases over time, with a 35% increase in the probability of a peace agreement lasting 15 years.’

Jo Cox

But processes alone are not enough – it’s the attitudes and behaviours that allow such thing to happen in the first place that need to shift. Sometimes the more subtle forms of discrimination are the hardest to root out – the everyday sexisms that are tolerated and remain hidden simply because they are so routine.

For this to change we will need a real shift in ourselves and in our organisations. And this means not only working with women, or the most marginalised, but with men and boys and those in power as well. Most men do not rape or exploit or abuse women, and those who do must be punished. But men in power may be sexist or discriminatory or both. Working with men, especially young men, to understand sexist or discriminatory behaviour is a critical part of addressing the power imbalance that can sometimes lead to the kind of sexual exploitation that has been revealed so starkly in the past months.

Finally, we need to use this spotlight on our sector positively. It’s an opportunity to redouble our efforts to promote gender equality, social justice and women’s rights, both inside and outside our organisations. To challenge those who see women as less worthy or capable than men. To be more inclusive and diverse. To listen to women and girls so we can help create more space for women and women’s organisations all over the world. To challenge the individuals and institutions that perpetuate privilege, and to ensure that those who exploit their power, whoever and wherever they are, do not get away with.

I believe we can seize this moment to build the change that feminists in our sector and elsewhere have long wanted to see. Perhaps then by International Women’s Day in 2019, we will truly have cause to celebrate.

March 6, 2018

How poor countries like Mongolia may be losing millions because of corporate tax practices and legal loopholes

Sarah McNeal is an Extractive Industries Policy Assistant at Oxfam America. This was first posted on its The

Oyu Tolgoi

When oil and mining companies extract resources in developing countries around the world, tracking the so-called “extractive industry” financial transactions can, at times, feel like a trip through Wonderland. Between the convoluted ownership structures and dead-ends created by corporate confidentiality, following the chain of responsibility from the project to the supposed ultimate beneficiaries – citizens – is rarely straightforward. But Dutch non-profit Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) set out to follow the trail down the rabbit hole anyway. They allege in a recent report that the Canadian company behind Mongolia’s Oyu Tolgoi copper mine may have taken advantage of preferential trade agreements to minimize its tax payments to Mongolia and Canada by as much as $700 million. (The report was produced in collaboration with a local group, Oyu Tolgoi Watch.)

As the SOMO analysis illustrates, the information required (e.g. tax payments) or encouraged (e.g. investment agreements) to be disclosed by companies under standards such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) – or by tax payment disclosure laws in Canada or the European Union – can help reveal potentially abusive tax practices. Such multi-million dollar losses have real consequences for the citizens who should be benefitting from the revenue generated by resources in their countries.

Following the money in Mongolia

Let’s take a closer look at the Mongolia case. Mongolia, sometimes referred to as “Mine-golia”, is highly dependent on its mineral resource wealth. Mining products and precious metals made up 87 percent of Mongolia’s total exports for an estimated value of $4.2 billion in 2016. At the same time, poverty levels remain persistently high. The National Statistical Office reported that 29.6 percent of the population lived below the national poverty line in 2016.

The Oyu Tolgoi mine is one of the largest operating copper mines in the world – so large, in fact, that the mine is expected to make up 30 percent of Mongolia’s GDP when it reaches peak production. The mine is jointly owned by the Government of Mongolia (34 percent) and the Vancouver-based Turquoise Hill Resources Ltd. (66 percent), which is itself majority-owned by global mining giant Rio Tinto. As SOMO’s Mining Taxes report highlights, the Mongolian government was unable to raise the necessary capital to finance its portion of the project directly. Thus, Turquoise Hill is currently covering the government’s contribution through an intercompany loan, with the government’s payments being deducted from any future dividends. However, Turquoise Hill is not lending the money directly to Oyu Tolgoi LLC – instead, the funds flow through a chain of subsidiaries in Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

As it turns out, it is easy to set up “shell companies” – companies that meet the legal requirements for substantial presence on paper but otherwise have no real office or staff – in both Luxembourg and the Netherlands. In Turquoise Hill’s case, the Luxembourg subsidiary has one part-time staff and the Netherlands office has zero. SOMO points out that these arrangements allow corporations to take advantage of preferential tax agreements without establishing full-fledged operations in those countries.

As it turns out, it is easy to set up “shell companies” – companies that meet the legal requirements for substantial presence on paper but otherwise have no real office or staff – in both Luxembourg and the Netherlands. In Turquoise Hill’s case, the Luxembourg subsidiary has one part-time staff and the Netherlands office has zero. SOMO points out that these arrangements allow corporations to take advantage of preferential tax agreements without establishing full-fledged operations in those countries.

For instance, when the Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement was signed in 2009, both Luxembourg and the Netherlands were party to double tax agreements (DTAs) with Mongolia that reduced withholding tax payments from the standard 20 percent to 10 percent and 0 percent respectively. After an IMF report in 2012 declared that these particular agreements could be used to facilitate tax avoidance, Mongolia unilaterally terminated the DTAs. However, thanks to the stabilization clause within the 2009 mine Investment Agreement, the original tax rates still applied to Oyu Tolgoi.

The withholding tax rate was further negotiated down from 10 percent to 6.6 percent (applied retroactively) in 2015 following a disagreement between the government and Turquoise Hill over the financing package for the second phase of the mine. SOMO calculates that if Mongolia’s 20 percent withholding tax rate had been in place, the government could have collected an additional $230 million in taxes from 2011 to 2015 on the outgoing loan interest payments to Turquoise Hill, allowing Mongolia to double its spending on education and health care. Instead, in 2017 Mongolia accepted austerity measures as part of a $5.5 billion bailout package from the IMF, including a significant hike in personal income tax rates. Moreover, by holding the interest profits in Luxembourg (with an effective tax rate 2010-2016: 4.19 percent) rather than Canada (average tax rate 2010-2016: 26.6 percent), SOMO estimates that the company also avoided up to $470 million in tax payments to Canada.

In response to these claims, Turquoise Hill argued that both the Canadian and Mongolian governments approved the tax arrangements and that the company was operating in full compliance with the law. Turquoise Hill also pointed out that the presence of a Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT), not the DTA, between Mongolia and the Netherlands was the driving force behind opening a Dutch subsidiary. BITs are another common tool used by companies to protect their investments. Most treaties contain arbitration clauses that allow companies to sue governments over regulations they perceive as harmful to their business interests, which may include changes in corporate income tax rates.

Making sure taxes work for citizens

Unfortunately such tax practices are the norm, rather than the exception, within the extractive industries. For instance, another Canadian company, Caledonia Mining Corporation, allegedly took advantage of a DTA between the UK and Zimbabwe to reduce its interest and dividend withholding tax payments to almost nothing. And in December a number of oil, gas and mining giants were accused of adopting similar tactics to avoid paying taxes in Australia.

While there has been a lot of progress on improving the disclosure of taxes paid through payment disclosure laws  and the EITI, it is disappointing to learn that many of the same companies supporting EITI are involved in these practices. The Oyu Tolgoi case suggests that in addition to strengthening global transparency standards, Oxfam and our allies must continue the coordinated effort on a broader tax justice agenda, including closing the legal loopholes that allow these questionable behaviors to persist. The Netherlands has recognized the need to address such abuses and recently proposed minimum substance requirements for companies, including wage expenses of at least EUR €100,000, to prevent shell companies from enjoying tax treaty benefits. This complements the Dutch government’s commitment to insert clauses against treaty shopping into all of its tax treaties. Other governments should, at minimum, follow the Dutch example and take stronger action against tax abuses. Without such commitments and rule changes, there may be many more stories like Oyu Tolgoi in the future.

and the EITI, it is disappointing to learn that many of the same companies supporting EITI are involved in these practices. The Oyu Tolgoi case suggests that in addition to strengthening global transparency standards, Oxfam and our allies must continue the coordinated effort on a broader tax justice agenda, including closing the legal loopholes that allow these questionable behaviors to persist. The Netherlands has recognized the need to address such abuses and recently proposed minimum substance requirements for companies, including wage expenses of at least EUR €100,000, to prevent shell companies from enjoying tax treaty benefits. This complements the Dutch government’s commitment to insert clauses against treaty shopping into all of its tax treaties. Other governments should, at minimum, follow the Dutch example and take stronger action against tax abuses. Without such commitments and rule changes, there may be many more stories like Oyu Tolgoi in the future.

March 5, 2018

I’m helping run a summer school on Adaptive Management. In Bologna. Interested?

This could be a lot of fun, I’m working with two of the smartest minds in Oxfam: Irene Guijt (head of research) and

Tough gig etc

Claire Hutchings (head of Programme Quality) to design and deliver a one week summer school course on ‘Adaptive Management: Working Effectively in the Complexity of International Development’. Between us we are going to try and really combine the theoretical hand-waving stuff with the much more practical ‘here’s how you change what you do on the ground’ approach of practitioners. The course runs from 11th-15th June, 2018, And it’s in Bologna, Italy, which is pretty cool.

Here’s the blurb:

‘In the last few years, “Adaptive Management” (AM) and “complexity-aware monitoring and evaluation and learning” have gone viral as new development catchwords. Networks of donors, practitioners and researchers, such as ‘Doing Development Differently’, ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ and ‘Adaptive Management’ have developed thinking, explored current practice and are starting to propose new approaches that recognize that to be effective, international development programmes need to address the complexity and unpredictability of the contexts in which we work. This 5- day course offers a blend of grounded theory, case studies and student clinics, which will help us to understand the importance of complexity, the need for Adaptive Management, and its applications for international development programming.

Day 1> Introduction and definition of Adaptive Management

Day 2> Design and planning: exploring systems, power and stakeholder mapping

Day 3> Implementing: managing collaborative and iterative programs and activities

Day 4> Integrating complexity-aware monitoring, evaluation and learning

Day 5> Institutionalizing Adaptive Management – Making the case for AM to leaders and peers

Enrollment Fees: 1,500 Euros (early review) -1,700 Euros (general application)

Early Review Deadline: April 15, 2018 General Application Deadline: May 15, 2018.

More Information and application: for more information on the course and trainers click here

Download the application form at this link and return by email to: summer-school@cid-bo.org’

The following week, there’s a 3 day seminar on ‘Outcome Harvesting for Complex Development Programmes’, also in Bologna.

March 2, 2018

Links I Liked

I’m defrosting in Dar es Salaam next week, hanging with one of my all-time favourite NGOs – Twaweza.

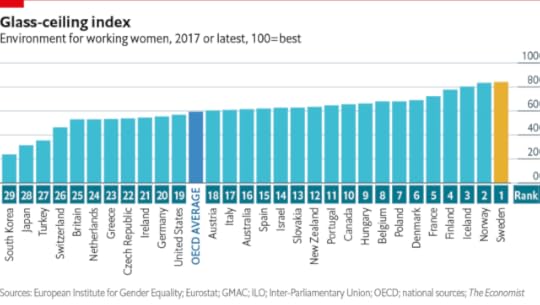

Ahead of International Women’s Day on Thursday, here’s the Glass Ceiling Index for OECD countries, ranking the best and worst countries for working women. Nordics win again. Britain at #25 – sigh.

Science reporter Ed Yong spent two years trying to fix the gender imbalance in experts he quotes in his stories (lot of his steps applicable to academics) h/t Chris Blattman

Dictionary-makers found the first known use of “mansplain”

‘From a study of 120 English hospital trusts over a four-year period, published in the journal Policy & Politics, we found that spending on external management consultants was associated with increased inefficiency.‘

Answers on grant proposals if non-profits were brutally honest with funders ht Chris Roche & Stephanie Lusby

A cracking idea for your future footnotes ht Paul Jackson

A cracking idea for your future footnotes ht Paul Jackson

In civil wars, conflicts are more likely in weak states, but within those they are more likely to erupt where weak states exercise *more* control, not less. Interesting use of night-time light as proxy for state presence

Nearly 105,000 Haitians migrated to Chile last year — 1% percent of Haiti’s population.

March 1, 2018

Where does political will come from?

Claire Mcloughlin and David Hudson summarise the Developmental Leadership Program’s recent 10 year synthesis report,

Claire Mcloughlin and David Hudson summarise the Developmental Leadership Program’s recent 10 year synthesis report,  Inside the Black Box of Political Will

.

Inside the Black Box of Political Will

.

When reforms fail, people often bemoan a lack of ‘political will’. Whether it’s failure to introduce legislation promoting women’s rights, not getting vital public services to rural communities, or weak implementation of anti-corruption measures, the shorthand answer is often that the political motivation just wasn’t there. On the flipside, its often assumed a politician’s willingness to spend valuable political or reputational capital can tip the balance in favour of meaningful change.

Political will may be a temptingly simple and intuitive explanation for why reforms succeed or fail, but it’s a turn of phrase masquerading as an explanation. What exactly is ‘political will’? Where does it come from? And crucially, how can it be strengthened? Political will is a classic black box problem. Even if we think it matters – it somehow mysteriously transforms outcomes – we don’t know how, exactly.

For more than ten years, research from the Developmental Leadership Program (DLP) has investigated the inner workings of the black box. The findings challenge two basic assumptions about where political will comes from. First, it’s not an individual phenomenon that happens inside politicians’ heads, but a collective one. No individual leader can bring about change by themselves. Frankly, there’s no point having political will if you don’t have the collective capacity to implement it. Second, collective political will doesn’t magically appear – motivation to act is built through a political process of contestation – the conflictual, though not violent, process of negotiation and deliberation. Leaders are never entirely free from rules that constrain or restrain them. In the real world, change hinges on the complex relationships between individuals and the norms and rules they inhabit – their institutional context.

The sum contribution of the research is to show how political will can be curated and embedded through a process of ‘developmental leadership’. This is a collective, strategic and political process through which people contest institutions and make change happen. It happens in the backstreets, meeting halls and homes of Suva, where a social movement of organisers and activists successfully blocked the proposed removal of protection on the grounds of sexual orientation from the Fijian Constitution. Or in Jordan, where a coalition successfully helped introduce new legislation protecting women from domestic violence. Or through the clan structures and secondary schools of Somaliland, where peace was secured and has been maintained against the odds.

Developmental leadership is typically messy, often protracted, and frequently beset by missteps and reversals. It  relies on three core elements coming together at the individual, collective and societal level (see diagram)

relies on three core elements coming together at the individual, collective and societal level (see diagram)

First, on motivated and strategic individuals with the incentives, values, interests and opportunity to push for change. Experience of higher education is key to the emergence of leaders with shared values, key skills and political networks. Elites that that helped bring about change in Mauritius, Ghana, and Somaliland were well-educated and had often gone to the same schools or universities. They often viewed their experience of higher education as formative to their future motivation in pushing for developmental change. But motivation is not enough. Even the most willing agents need a combination of power and opportunity to realise their goals, as well as the skill to work strategically. Women leaders in the Pacific used their family and political networks, alongside their education and expertise and international networks, to effectively navigate male-dominated political environments in highly politically-savvy ways.

Second, motivated people must overcome barriers to cooperation and form coalitions with sufficient power, legitimacy and influence. Their effectiveness hinges on the kinds of political strategies and tactics they use, their perceived local legitimacy, the quiet political work they do behind the scenes, and ultimately, their pragmatism. Trust between the public and private sectors can be built through leaders using symbolic public gestures that signal commitment. Coalitions can be made up of people committed to reforms, as well as those who are simply opportunistic.

Third, coalitions’ power and effectiveness partly hinges on their ability to contest and de-legitimise one set of ideas and legitimise an alternative set. Fixed ideas can be a significant impediment to change, and the work of coalitions is often to change the ideas that underpin all institutions. If they can do that, they can reformulate institutions in ways that are perceived as locally legitimate, anchor them in local norms, and therefore make change more sustainable. Narratives and framing are important for how ideas are changed – that is, how change is communicated to the people who need to be convinced it’s fair and right for society. Effective gender programming sometimes may have to avoid using the language of gender entirely, for example.

So what does this all mean for building political will? Institutions do change, whether rapidly or incrementally, through a political process of contestation. Aid actors can strategically support this process if they think and work politically. They can support the development of leadership values and motivation through quality education at all levels. They can create space for coalitions to form and to work their politics. Even networks with high levels of trust need ‘safe spaces’ where these processes can occur. And they can navigate legitimacy politics by identifying areas for contesting norms and ideas, without undermining the legitimacy of the actors they work with.

So what does this all mean for building political will? Institutions do change, whether rapidly or incrementally, through a political process of contestation. Aid actors can strategically support this process if they think and work politically. They can support the development of leadership values and motivation through quality education at all levels. They can create space for coalitions to form and to work their politics. Even networks with high levels of trust need ‘safe spaces’ where these processes can occur. And they can navigate legitimacy politics by identifying areas for contesting norms and ideas, without undermining the legitimacy of the actors they work with.

Collectively, this adds up to a bigger picture on how donors can approach politics, power and ideas in aid programming. This sometimes means letting the process run its course, and not jumping to answers. Politics is not a problem of political will, it is the necessary process through which agents defend, contest and change institutions, and through which the necessary political impetus for change is built and sustained. Politics is not the obstacle, it is the way forward.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers