Duncan Green's Blog, page 100

February 28, 2018

The Global Politics of Pro-Worker Reforms

Guest post from Alice Evans,

Lecturer in the Social Science of Development at King’s College, London

Guest post from Alice Evans,

Lecturer in the Social Science of Development at King’s College, London

Politically smart, locally-led collaborations are all the rage in international development. Through iterative adaptation and experimentation, states can improve their capabilities and learn what works for them. So sings the choir.

But we also need to recognise that governing elites will experiment in ways that further their priorities, as shaped by the wider political economy. Politics matters, of course. But many political analyses of inclusive development and growth focus on domestic drivers (Hickey et al, 2017; Pritchett et al, 2017). This is short-sighted. It is blinkered to the ways in which commerce, trade deals, and geopolitics deter (or possibly encourage) pro-poor experimentation.

Take the global garment industry: a major generator of jobs, exports and economic growth. But factory work is often poorly paid, precarious, and dangerous. Overt resistance is deterred by the prevalence of short-term, insecure contracts; fear of job loss; patriarchal trade unions; and management intimidation. Even if workers do protest for higher pay, firms and governments are often unresponsive – for fear that price-competitive global buyers will relocate to countries with lower costs.

Buyers seek low costs to remain price competitive on European high streets. Workers, manufacturers, retailers and governments perpetuate this system in order to preserve jobs, orders and economic growth. Unilateral deviation is costly. This creates a major collective action problem: risking another Rana Plaza (the factory collapse that killed over a thousand Bangladeshis).

Workers strike at the Pou Yuen factory in Ho Chi Minh City, March 31, 2015.

So, how can rich countries support workers’ rights, activism, and pay? To answer this question, I researched the political drivers of pro-worker reforms in Vietnam. I investigated why the Government became increasingly supportive of independent unions (freedom of association), a higher minimum wage, social dialogue between management and workers, and collective bargaining.

What motivated reform?

TL;DR: strikes, commerce, pressures from reputation conscious buyers, trade deals, and geopolitics.

Dissatisfied by their working conditions, Vietnamese factory workers have expressed discontent by strikes. These are made possible because skilled labour is now in short supply in industrial zones; companies’ are desperate to maintain production; and the state has tolerated both strikes and positive media coverage of them. In this context, strikes often secure improvements. News of victories inspires wider mobilisation. This alarms manufacturers – concerned about productivity, deadlines, and reputation-conscious buyers. Strikes also triggered Government concerns about its own legitimacy.

Keen to address workers’ concerns and prevent escalation, some have become more experimental: introducing social dialogue. This was championed by the Better Work Programme (an ILO-IFC initiative, with reputation-conscious buyers, to improve working conditions). Through gradual familiarisation, diplomatic phrasing, incremental adjustments, ongoing engagement, and inviting the government to undertake its own research, Better Work allayed elites’ anxieties about engaging worker representatives in dialogue. Reformists then used evidence of its effectiveness to win over conservative colleagues.

The experience of Better Work may be useful for other donors trying to engage politically: recognising that they are merely providing a space for local governments, businesses and workers’ organisations to explore policies that address their concerns. By testing new initiatives, pilots may shift perceptions about what is feasible, and how others will react. This alleviates anxieties about the unknown.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership also galvanised reform. This free trade agreement offered greater market access, as  well as stronger international partnerships and military security. But the US demanded something in return: compliance with international labour standards, especially Freedom of Association.

well as stronger international partnerships and military security. But the US demanded something in return: compliance with international labour standards, especially Freedom of Association.

Such trade-labour agreements are often described as ‘external pressures’, ‘forcing countries to be good’. That’s not what I found. Listening to Vietnamese actors, it seems that trade deals can legitimise domestic discussions on hitherto silenced, stigmatised subjects (such as Freedom of Association); enable supporters to speak openly, explore these ideas without fear of sanction; realise their views are widely shared; and build reform coalitions.

However, many conservative politicians in Vietnam feared independent unions and resisted TPP. Such concerns lessened in 2014, when China deployed an oil rig in a disputed region of the South China Sea. This triggered widespread, violent anti-China protests throughout Vietnam. Although many conservatives were anxious about TPP and FOA, reformists used this crisis to reveal the dangers of the status quo: military insecurity, faltering economic growth, and ongoing strikes.

In November 2016, Vietnam’s Central Committee announced they would permit independent trade unions. Three days later Donald Trump was elected and promptly withdrew from TPP. Without the USA’s economic and geopolitical incentive for FOA, government reform stalled. Presently, independent labour activists are being arrested and beaten, as part of a wider crackdown on dissidents.

Here we see the combined power of strikes, responsible business practices, trade deals, and geopolitics. All these levers can support a more enabling environment for women workers’ activism.

Thus, while the international development community increasingly champions iterative adaption, my research in Vietnam highlights the complementary importance of domestic and transnational political pressures for pro-poor reform.

So, let’s broaden the toolkit: engage more powerful drivers of change; engage with lead buyers; strengthen corporate accountability (such as the Bangladesh Accord, and France’s Duty of Vigilance Law); engage with trade deals, and geopolitics. Tackling global governance (reforming our supply chains) could build a more enabling environment for workers’ activism and pro-poor experiments.

Curious? Read the paper, or join Gawain Kripke (Oxfam America), Kim Elliot (CGD), and Alice Evans to discuss the politics of pro-worker reforms at CGD in Washington D.C., on 6th March.

This paper is part of a series on gender and politics, supported by the Australian Government.

February 27, 2018

5 common gaps and 4 dilemmas when we design influencing campaigns

I’ve just read the initial proposals of 30+ LSE students taking my one-term Masters module on Advocacy, Campaigning and Grassroots Activism. Their two main assignments are to work as groups analysing past episodes of change (more on that later in the term) and individual projects where they design an influencing exercise based on their own experience and the content of the course (power analysis, stakeholder mapping, systems thinking etc) They’re great in their passion and range (everything from reforming US healthcare to getting sexual harassment taken seriously in Delhi Government Schools). A lot of them showed a good ability to ‘dance with the system’ of the different tiers of the state (national, provincial, municipal), though they seemed less clear on the workings of the private sector or other key institutions. They also share some common gaps – that’s probably down to my faulty guidance on how to design the case studies (see below). Here are the main ones I identified:

healthcare to getting sexual harassment taken seriously in Delhi Government Schools). A lot of them showed a good ability to ‘dance with the system’ of the different tiers of the state (national, provincial, municipal), though they seemed less clear on the workings of the private sector or other key institutions. They also share some common gaps – that’s probably down to my faulty guidance on how to design the case studies (see below). Here are the main ones I identified:

Precedents and positive deviance: lots of great ideas, but if you can say ‘this has already happened in the country next door’ or ‘two cities are already putting this into practice’, you have far fewer arguments to overcome on feasibility.

Implementation Gaps: If a law or policy has been approved, and not implemented, then a campaign suddenly becomes much more straightforward – the government or company can’t deny its feasibility or desirability, after all. But most students seemed to prefer starting from scratch (i.e. the hard way).

The twin temptations of turkeys-for-Xmas and cumbaya campaigns: I’m trying to help the students design winnable campaigns, but some seem determined to try and persuade assorted turkeys to vote for Christmas (i.e. unwinnable campaigns to persuade those in power to do something that runs completely counter to their own interest), while others go to the opposite extreme and design campaigns that everyone already agrees with (in which case, you really just need a feasibility study).

The twin temptations of turkeys-for-Xmas and cumbaya campaigns: I’m trying to help the students design winnable campaigns, but some seem determined to try and persuade assorted turkeys to vote for Christmas (i.e. unwinnable campaigns to persuade those in power to do something that runs completely counter to their own interest), while others go to the opposite extreme and design campaigns that everyone already agrees with (in which case, you really just need a feasibility study).

Faith organizations: these were often absent from the analysis, even though they are highly relevant both to shifting norms, and in many cases as sources of behind-the-scenes ‘hidden power’ able to influence decision makers.

Stunts: The students were big on research, rational analysis, social media, but not many wanted to have fun with stunts that capture public or policy makers’ interests. Feels like I must have failed to get this across – I ended up suggesting to the student advocating for paid interns at the UN that they consider setting up an intern encampment in the middle of Geneva to highlight the issue of intern poverty there!

And some dilemmas too:

Insider v Outsider: People’s choice of tactics often seemed to reflect their personal preferences, rather than their analysis. Some students said ‘this country/process probably suits an insider approach’ and then promptly started talking about petitions and protests!

Should campaigns be winnable? I personally veer towards the achievable, but that can make you terribly timid, always looking for little tweaks here and there, rather than going for the big prizes. I guess my compromise is that if you want to pursue long shots, I want to see your working!

Do you go broad or narrow? My preferred option is for students to choose a specific change (a new policy, law or institution), which then allows you to go deeper into understanding the way decisions are made, the stakeholders involved and the power analysis of the various players, before coming up with some possible influencing strategies. You can then get started and adapt the strategy in light of experience. But then I realized that this introduces a bias against some of the less precise, but important ‘power within’/’invisible power’ influencing on norms, attitudes and beliefs. Maybe the compromise is ‘broad issue, narrow strategy’ or ‘narrow issue, range of strategies’. What doesn’t work is a broad issue, and a whole load of possible strategies, which tends to lead to a lot of vague hand-waving.

The tyranny of frameworks: I’ve run through a few of the ways to think about power (four powers, power cube etc) and already they are starting to look like a new orthodoxy, with students anxiously asking me which one to apply (or should they use all of them). Time to remind everyone that they are tools, and only useful if they work for you in a given situation.

Here’s the guidance I gave for the influencing project. This is the first year I’ve given the course, so any advice on how to improve it would be very welcome.

February 26, 2018

What makes Adaptive Management actually work in practice?

This post by Graham Teskey, one of the pioneers of ‘thinking and working politically’, first appeared on the Governance Soapbox blog

It’s striking how important words are. USAID calls it Adaptive Management, DFAT calls it Thinking and Working Politically, DFID calls it Politically Informed Programming, and the World Bank just ignores it altogether.

More seriously – what is at issue here? At heart, I would argue that this agenda – TWP, DDD or even PDIA – means four things:

being much more thoughtful and analytical at the selection stage (thinking about what is both technically appropriate and what is politically feasible);

being more rigorous about our theories of change (how we judge change actually happens in the sphere in question) and our theories of action (how and why the interventions we propose will make a difference);

our ability to work flexibly (meaning to respond to changing policy priorities and contexts, and by adapting implementation as we go – changing course, speeding up or slowing down, adding or dropping inputs and activities, changing sequencing etc.);

and our willingness and ability actively to intervene alongside, and support, social groups and coalitions advocating reform for the public good.

It is third characteristic that this blog is about. Working flexibly.

It is the flexibility of TWP-informed programming that usually attracts most attention. Many words are used interchangeably and uncritically: flexible, responsive, adaptive, agile, nimble etc. As noted above TWP emphasises responsiveness and adaptation. In the programs that I have worked on recently, it is adaptation that poses the major challenges to TWP: the ability to change course as implementation proceeds.

In discussions, the simple answer often given is that we remain wedded to the project framework and the annual plan and budget because, well, that is what we do and that is what the donor wants, and it’s important not to miss our spending target or drift off plan. I think this answer is clear, simple and wrong. Let me try to explain why.

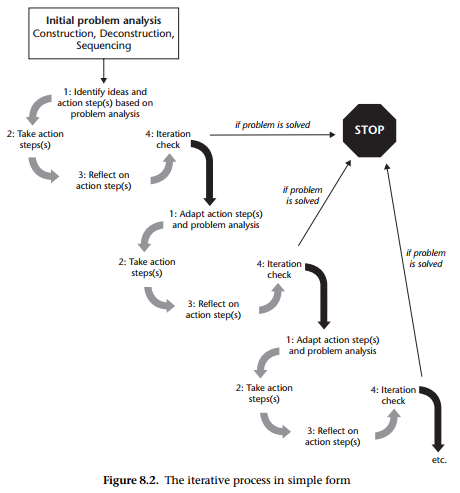

One way to iterate – from ‘Building State Capability’

When looking at issues of organisational change, public service reform and ‘capacity development’ it is now commonplace to structure the analysis in terms of three ‘layers’ or ‘levels”: the individual, the organisational and the institutional. We have known this for twenty years or so. At the individual level staff need to be trained and skilled, and with appropriate tools, to do the job. At the organisational levels appropriate systems, structures and procedures need to be in place. And at the institutional level ‘the rules of the game’ have to incentivise a culture of performance and results. In most evaluations of public service reform or case studies of organisational change, we have found that it is one thing to help strengthen individual competencies and improve organisational structures and systems, but it is another thing altogether adequately to address the institutions that incentivise performance. We have learned that turning individual competence into organisational capacity requires institutional change.

But in implementing TWP I think this is turned on its head: currently there are many incentives in place for TWP. Donors say they want it – implementing partners certainly want to. But the constraints are at the organisational and individual level. The reason is that adaptation in program delivery requires four functions to be delivered simultaneously:

implementation: the day-to-day, week-to-week task of delivering activities (how are we doing on physical progress?);

monitoring: the regular and frequent checking of progress towards achieving outputs (are we on track against the plan, the budget – and most importantly – against outputs and possibly outcomes?);

learning: our internal and reflexive questioning of progress – what are we learning about translating inputs and activities into outputs and outcomes (what is working and what isn’t?); and

adapting: revising our implementation plan, adding unforeseen activities and dropping others, changing the balance of inputs, be they cash, people or events etc. (how are we changing the plan?).

Only if we ‘learn as we go’ can we adapt in real time: this requires delivery (implementation), data collection (monitoring), learning (reflection) and adapting (changing) to be undertaken simultaneously, not sequentially. And it is here I believe that we run into severe constraints at the organisational and individual levels.

At the organisational level, the development industry has got into the bad habit of bracketing the two very different  tasks of monitoring and evaluation: development practitioners are programed to say “monitoringandevaluation” all in one word, as if the two are actually one. Only recently has L (learning) been added – but added to ‘MandE’ to form MEL. The result in project management is that the responsibility for monitoring is handed over to structurally separate functional units far removed from operational delivery and implementation. Staff responsible for delivery say “monitoring is nothing to do with me”. And of course MandE staff tend to evaluate ex post, rather than in real-time.

tasks of monitoring and evaluation: development practitioners are programed to say “monitoringandevaluation” all in one word, as if the two are actually one. Only recently has L (learning) been added – but added to ‘MandE’ to form MEL. The result in project management is that the responsibility for monitoring is handed over to structurally separate functional units far removed from operational delivery and implementation. Staff responsible for delivery say “monitoring is nothing to do with me”. And of course MandE staff tend to evaluate ex post, rather than in real-time.

At the individual level, it is hard to imagine implementation staff with the skills and competencies (let alone the time) to undertake the four functions noted above. The skills required for efficient and effective implementation against a plan and a budget are not the same as the skills for assessing progress, analysing what has worked and why, and having the experience and judgement to know which parts of the plan need adapting and in what direction – all in real-time.

The answer seems pretty straightforward: break up MEL by allocating monitoring and learning responsibilities to implementation teams; increase their resourcing by building implementations teams with multiple skill sets and competencies; insist on regular and robust internal review and reflection exercises (at least monthly); clarify precisely the level of delegated responsibility and authority for adaptation to be given to implementation teams; and negotiate all this with the donor and the partner government.

Or is this answer clear, simple and wrong too?

February 25, 2018

Links I Liked

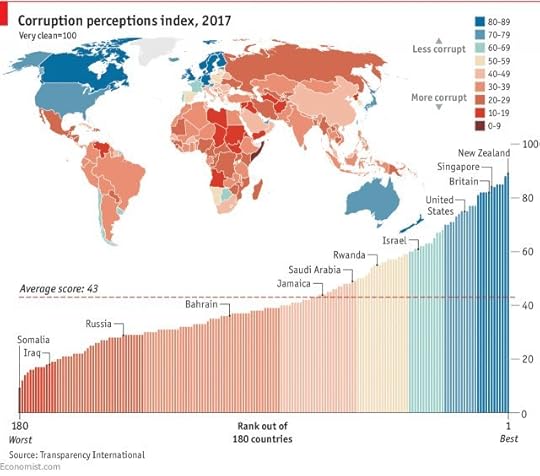

Corruption perceptions index 2017. New Zealand the cleanest, Somalia bottom of the heap.

Should advocates also be philanthropists in their personal lives, changing the world in the ‘nownow’ while pushing for the big (but long term) stuff? Thoughtful agonizing from Chambi Chachage

World Development Report 2019 will be on ‘The Changing Nature of Work’. Here’s the 40 page ‘concept note‘. Anyone read it yet? If so, what did you think?

Some enterprising LSE students have started a development podcast, called The World Isn’t Flat (a retort to Thomas Friedman – anyone remember him?). Here’s them chatting to me about the role of NGOs in Development

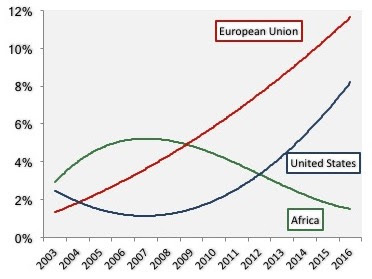

Chinese investment in Africa is not only modest, it is falling.

Update on Oxfam and se xual misconduct:

xual misconduct:

Last week Oxfam released its 2011 Haiti investigation report.

LSE Prof David Lewis explores the wider implications for aid

“Is Oxfam the worst or the best?” Academic Dyan Mazurana conducted a two-year research programme into sexual harassment and abuse in the aid sector. She finds serious sector-wide failings, but ‘Oxfam is today one of the best international aid agencies in terms of reporting, investigating and addressing sexual harassment, exploitation and abuse of its staff.’

Back to other stuff:

Branko Milanovic’s GlobalInequality blog is the best thing that’s happened to development blogging in years. Here he is on the dual delusions of conspiracy theorists and those who believe they are free to say/do whatever they want.

How one community beat the system, and rebuilt their shattered streets. Aditya Chakrabortty with a great new episode in his inspiring ‘Alternatives’ series.

World’s largest (14,000 projects, 8 donors) database of development projects with outcome ratings now available for download/public use

Lissa Lucas, you are amazing. How to make the most of your 105 second slot at a public hearing. ht Greg Hogben

February 22, 2018

Book Review: Aids Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations, by Ethan B Kapstein and Joshua W Busby

Thanks to (here’s a free pdf of the first chapter). Kapstein and Busby painstakingly researched the rise, tactics and successes/failures of the global advocacy campaign around access to medicines for HIV/AIDS. Their (hugely ambitious) aim is not just to understand a movement that has saved thousands of lives, but to draw wider lessons because, as they say: ‘recent years have seen an explosion in the number of advocacy campaigns aimed at changing the behaviour of multinational corporations and the way that markets function’. (Think fair trade, fisheries protection, labour standards, carbon emissions, land grabs, gender equity.)

Besides the case study, the authors delve into the academic literature on the economics and politics of markets (great quote from Carlyle: ‘teach a parrot the terms ‘supply and demand’ and you’ve got an economist’), which means it gets pretty dense in places. But the book is a treasure trove of insights and advice – highly recommended. It’s also bloody hard to review – there’s just too much there.

So I’m going to do violence to the book and jump straight to its Big Idea on the role of advocates in spurring transformations, which the authors call a ‘theory of strategic moral action’:

‘Market transformation in the case of Anti Retrovirals required the following: first, a market structure or favourable set of underlying economic and industrial conditions that provided opportunities or openings for an advocacy movement; second the elaboration by the AIDS movement of a compelling frame that pitted drug company profits against global access to life-saving ARV medications; third, a political and organizational consensus or coherent ‘ask’ on the part of the social movement that treatment should receive the highest policy priority, trumping, for example, prevention; fourth, a feasible strategy (defined in this case as one that minimized the costs of market transformation to the major players) for how a universal access to treatment market could be made to operation; and finally, a set of institutional arrangements to help set the rules for the transformed market and to stabilize its operations.’

Their conclusion becomes a handy checklist/steer for other activists, with a chapter on each fleshing out the issues:

‘Advocates need to ask whether they have identified the opportunities within the industry they are targeting; whether they have framed the issue in a compelling way; whether they have a coherent ask; whether they have a feasible strategy that addresses concerns about costs by firms and governments; and whether supporting institutions need to be built.’

Along the way they show a nuanced grasp of systems – the shifting tides of institutions and markets, noting that the regime around intellectual property was still emerging, and so malleable than older, more fixed arrangements, and that the pharmaceutical industries’ degree of turbulence (lots of disruptive mergers and acquisitions) and concentration made it easier for activists to play divide and rule between the big companies.

Civil rights activists march in Durban, South Africa, Monday JUL18, 2016 at the start of the 21st World Aids Conference to demand that the fight against HIV/Aids be continued and that funding in the fight against the disease must not be cut. U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon told reporters that the gains the world had made against AIDS are “inadequate and fragile” (AP Photo)

Next up they apply their theory to a bunch of other global campaigns seeking to emulate the impact of AIDS activists: malaria, maternal mortality, diarrhoeal disease, non-communicable disease (heart, cancer, diabetes), education, climate change, the elephant ivory trade, sex trafficking, and then they even back test their theory against the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade. Only access to malaria treatment achieves a ‘likely’, while reducing maternal mortality, expanding access to treatment for NCDs, reducing ivory poaching and sex trafficking get a ‘mixed’ and reducing deaths from diarrhoea, improved education, curbing climate change all get an ‘unlikely’. Activists shouldn’t get too downcast though – even abolishing the slave trade only gets a ‘mixed’……

But the guidance on questions to ask is, I think, really helpful, forcing activists to think more broadly about systems, opportunities and dead ends. It offers some useful advice on when not to campaign, by urging them to consider ‘where movements are placed in terms of their ‘life cycle’. If the market structure is difficult to contest (eg because of excessive fragmentation), movements may never really gain traction. Even with a compelling frame, unless movements cohere around a common ask, they will have difficulty convincing target actors to listen to them. Even where they are able to overcome this obstacle, they may face an uphill battle if the costs of their ‘ask’ are too high. Finally, in the absence of institutions that help stabilize the market around a new principle, the commitments may not endure – a movement may fracture and backslide to an earlier stage.’

That last point is particularly challenging, I think. It’s not enough to win, you have to think institutionally about what will make your victory sustainable. That’s a lot to ask of often small, under-resourced activist organizations.

I did have a few misgivings. Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but also creates a misleading sense of clarity andinevitability, transforming the fog and serendipity of events into a nice linear history. Typically, such accounts downplay the role of accident, luck. And having stupid opponents. That was vital in the access to medicines case, where some collective madness persuaded Big Pharma in 1998 to sue the South African government over its efforts to get cheap medicines to the sick. That’s right, they took Nelson Mandela to court, handing activists a perfect ‘Problem, Solution, Villain’ campaign moment. They dropped the case 3 years later, but by then the damage was done and the global AIDS movement never looked back.

And here’s a flavour of the South Africa campaign – Treatment Action Campaign: the First Five Years

February 21, 2018

Ebola Secrets: what happened when an epidemic hit a village in Sierra Leone?

Melissa Parker, Professor of Medical Anthropology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical

Melissa Parker, Professor of Medical Anthropology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical  Medicine, and Tim Allen, Professor of Development Anthropology at LSE and Director of the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa find long-standing customary forms of governance played a critical role in ending the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone. This blog first appeared on the LSE’s Africa blog.

Medicine, and Tim Allen, Professor of Development Anthropology at LSE and Director of the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa find long-standing customary forms of governance played a critical role in ending the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone. This blog first appeared on the LSE’s Africa blog.

‘I acted to save the lives of my people, but what I did will always play on my conscience.’ So said one of the most important paramount chiefs in Sierra Leone, recalling his role in managing the outbreak of Ebola in 2014-2016. Four years after the beginning of the outbreak, it is gradually becoming evident how the disease affected, and continues to affect, peoples’ lives.

Research on Ebola and public authority by teams based at Njala University in Sierra Leone, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the LSE, reveals how long-standing customary forms of governance played a critical role in ending the outbreak.

In the end, it was not the soldiers, the humanitarian INGOs, or the World Health Organisation that played the most important role in containing the spread of the disease. Instead, it was the people themselves and the public health measures imposed by paramount chiefs and their subordinates, including restrictions on movement, which turned the situation around. As Paul Richards, author of Ebola: How a people’s science helped end an epidemic, put it: ‘the paramount chiefs played a blinder!’ Our research confirms that was the case. However, for those involved in enforcing byelaws, it posed enormous challenges, not least because it necessitated people setting aside normal moral obligations to their own family members. Also, there was quite a bit more going on that has been barely noticed.

In the end, it was not the soldiers, the humanitarian INGOs, or the World Health Organisation that played the most important role in containing the spread of the disease. Instead, it was the people themselves and the public health measures imposed by paramount chiefs and their subordinates, including restrictions on movement, which turned the situation around. As Paul Richards, author of Ebola: How a people’s science helped end an epidemic, put it: ‘the paramount chiefs played a blinder!’ Our research confirms that was the case. However, for those involved in enforcing byelaws, it posed enormous challenges, not least because it necessitated people setting aside normal moral obligations to their own family members. Also, there was quite a bit more going on that has been barely noticed.

The people of Mathiane were among those on the receiving end of byelaws enacted by these customary authorities. The small village was seriously affected by the outbreak. Based on our local investigations, at least 56 people were infected and 38 people died from the virus. The numbers who died were much higher than those recorded in official documents, partly because some deaths were not reported to the district. Much that occurred during the epidemic was hidden, and for very good reasons.

One of the main ways in which Ebola was transmitted in Sierra Leone was through human to human contact  immediately before and after the death of infected people. Symptoms of Ebola include bleeding from bodily orifices, diarrhoea and vomiting. These secretions are highly infectious. Apart from close contact with those suffering from the illness, the normal processes of washing a corpse before burial in Sierra Leone made burial customary rites a major risk factor. But managing the final stages and the passing of a loved one is a hugely important aspect of social life. It was something that people in Mathiane, and people all over Sierra Leone, were reluctant to set aside. To do so was to set aside the ties of mutuality that make life meaningful.

immediately before and after the death of infected people. Symptoms of Ebola include bleeding from bodily orifices, diarrhoea and vomiting. These secretions are highly infectious. Apart from close contact with those suffering from the illness, the normal processes of washing a corpse before burial in Sierra Leone made burial customary rites a major risk factor. But managing the final stages and the passing of a loved one is a hugely important aspect of social life. It was something that people in Mathiane, and people all over Sierra Leone, were reluctant to set aside. To do so was to set aside the ties of mutuality that make life meaningful.

Members of the local burial team in Mathiane explained to the research team the reason why many of the infections and deaths were never noticed by outsiders. They were unwilling to ring the official phone line – 117 – to report incidents. They feared that their loved ones would not be cured at the Ebola Treatment Centre and their bodies would never be returned to their families. They knew that that was happening from accounts they were receiving from friends and relatives living in the towns and more closely monitored places.

Instead, residents in Mathiane reported to their own burial team, a group of men living in the village. Sick people were taken to hidden farms and locations in the bush, and when there were deaths, the bodies were buried late at night in locations that would not be recognised by outsiders as graves.

Mutuality in Mathiane is readily evident to anyone who spends time there. Families care for each other in intimate ways as part of daily life. They farm together, they share what they have. The open affection they show to each other’s children is striking. To abandon a resident to those who do not know them or love them is a violation of the social fabric, and was impossible to accept. Public authority in the village is premised on caring for each other in adversity, and that moral code was strong enough to undermine public authority associated with paramount chiefs, let alone aid agencies or the government.

Mathiane Village Elders

Although people in Mathiane heard about the public health regulations on the radio, they did not accept them. Instead, they developed their own strategies to contain infection. This included hiding sick people in places where they would not infect others, and encouraging them to consume pepper soup and drink a mix of lime and honey at regular intervals. It was a strategy that some remembered being particularly effective for the treatment of smallpox in the past. For those that did not survive, it was at least possible to bury their kin with safety and dignity. The local burial team believe they acted in the right way, and that they saved the lives of many who would otherwise have died.

It is possible that some of those they took away from the village, across swamps and streams, to places where outsiders would not find them, may have had malaria or other infections. But some certainly had Ebola, and many survived, because of the care they received from relatives – notably the continuous rehydration, which was only introduced in the official treatment centres after the intervention of Ugandan doctors in late 2014. The Ugandan doctors explained how they had massively reduced mortalities during the Ugandan epidemic of 2000, and once it was introduced in Sierra Leone, mortalities for those in treatment centres dropped from 70% to 30%.

Nevertheless, the people of Mathiane could not keep their secrets indefinitely. As infections spiralled in the region, and fatalities increased, it proved impossible to conceal the burials from outsiders. Information leaked to the chiefdom authorities and the District Ebola Response Team, who were trying to co-ordinate the response in the area. The customary chief was summoned to a meeting in a neighbouring village, with other chiefs in the area, and told that large fines would be imposed on anyone burying people without official sanction and the involvement of accredited burial teams. At that point, he knew that his own father was infected with Ebola, and when he returned to Mathiane, he was told his father had died, and had been buried by the local burial team.

Fearful that, because of local practices, the infection in Mathiane was not being contained, the authorities mobilised chiefdom authorities and the army to go to the village and seek confirmation that ‘secret’ burials were occurring. No-one in the village was willing to divulge the information. One child was even offered a substantial sum of money to tell the truth, but he refused to say anything.

Resorting to violence, the soldiers randomly pulled people out of their houses and beat them, including members of

Mathiane village school

the local burial team. In the end, a schoolchild, fearing for his life, succumbed to the pressure to talk. The town chief was removed from his position and a temporary town chief appointed, who later died in unexplained circumstances. Other secrets remain too. One woman explained to the research team that, shortly after the army entered the village, her mother died from Ebola. Her son fell ill while the house was quarantined, but she kept it hidden from the soldiers. He recovered.

More than three years have passed since this event, and some people are still suffering from injuries as a result of the intervention by the army. Looking back on these events, elders say there is much enduring pain. There is also much frustration. Due to Ebola, there was a great deal of interest in Mathiane, with visits by INGOs to the village, and this raised expectations that assistance would follow. However, the reality has so far been a set of empty promises.

Burial groups have been disbanded, visits from district officials have stopped, a nurse who is based at a Maternal and Child Health Post in a neighbouring village about an hour’s walk away perhaps visits once a month, but she has little to offer other than vaccinations for children under five. The health system is as weak as ever; and the promised school has not materialised. The village has done its best to make do with what is to hand. In classrooms made of bamboo sticks, the volunteer teachers manage with one blackboard between them.

Emma Kargbo, one of the teachers, explains:

“The children are so eager and enthusiastic. When asked what they want to be when they grew up – one wants to be a doctor, two want to be teachers, and three say they want to be President and bring development to their home… but at the moment there is little hope of such dreams coming true. All that money was spent on Ebola. So many NGOs came and made promises. But nothing is left behind. We are trying to help the children … but it is a circle of suffering.”

Her views were echoed by the recently elected section chief, Salamie Kamara (who is responsible for 17 villages, including Mathiane):

“The government has disappointed us. During Ebola, we saw a lot of ambulances. If someone dies, or if you are sick, they will take you to the hospital. Are they waiting for Ebola again, before they help us? One woman was meant to have given birth to twins. The umbilical cords were joined together. The TBA (traditional birth attendant) here had no idea what to do, and there was no way to rush her to the health centre. One child had already come out of the womb. It brought disgrace to us and everyone. She suffered so much. If a health centre had been there, or an ambulance had been around, they could have taken her to the health centre. The mum survived, but her children died. The nurse eventually came here, but it was too late to do anything…. It is not just the ambulances which have disappeared. Even the things that were put in place to monitor and control Ebola infection are no longer there. We in Mathiane were punished for caring for each other and not following instructions. But who cares about us now? What will happen when there is another epidemic?”

February 20, 2018

If everyone lived sustainably, what would their lives be like?

Guest post from Andrew Fanning, Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellow in the Sustainability Research  Institute at the University of Leeds. His research finding that no country currently meets the basic needs of its citizens at a globally sustainable level of resource was recently published in the journal Nature Sustainability (author summary here and there’s an interactive website). Here he reflects on a further insight from that research.

Institute at the University of Leeds. His research finding that no country currently meets the basic needs of its citizens at a globally sustainable level of resource was recently published in the journal Nature Sustainability (author summary here and there’s an interactive website). Here he reflects on a further insight from that research.

What level of resource use is associated with achieving a “good life”, and how does this compare to what is environmentally sustainable? In our paper, we looked at the current relationships between 7 indicators of national environmental pressure (relative to environmental limits) and 11 indicators of social performance (relative to the requirements of a good life) for over 150 countries. Based on the social thresholds that we chose, we concluded that resource use would need to decline by a factor of two to six times for all the world’s people to live well within planetary boundaries.

After we published the analysis, I was interested in flipping our research question around. Instead of estimating the level of resource use associated with a good life, I wanted to know what kind of life 7 billion people could expect to live at a sustainable level of resource use. Maybe some social indicators would be more sensitive to resource use than others. Maybe this knowledge would allow us to identify social goals where large gains could be made with little effect on resource use.

But how to do it? With 7 environmental indicators and 11 social indicators, I needed to understand 77 different relationships all at once! I quickly realised that such a large amount of numerical information was far too much for my mind to grasp. Since humans are visual creatures, I started thinking about how to visualise our data to see the changes in resource use associated with changes in social performance.

During coffee with Dan O’Neill (the lead author on our study) one day, I scribbled down an idea for how to visualise all of the data simultaneously. A screenshot of the interactive tool that eventually followed is shown below. The default setting for the tool is the values for a “good life” that we used in our study. The tool shows the median resource use of the 20 countries closest to each social threshold. Resource use is expressed so that a value less than one is globally sustainable (green), while a value greater than one transgresses the biophysical boundary in question (red).

The chart underscores one of our key findings: some dimensions of a good life are associated with much lower levels of resource use than others. The achievement of basic subsistence seems almost within reach at a sustainable level of resource use. Basic subsistence includes the provision of 2700 kcal of food per day, the elimination of extreme poverty below US $1.90 per day, and 95% access to sanitation and electricity.

The chart underscores one of our key findings: some dimensions of a good life are associated with much lower levels of resource use than others. The achievement of basic subsistence seems almost within reach at a sustainable level of resource use. Basic subsistence includes the provision of 2700 kcal of food per day, the elimination of extreme poverty below US $1.90 per day, and 95% access to sanitation and electricity.

But the achievement of other, more aspirational social goals has a level of resource use that is two to six times higher than globally sustainable levels. These goals include life satisfaction of 6.5 out of 10, healthy life expectancy of 65 years, and 95% enrolment in secondary education, among others.

But what about the original question that motivated me? What level of social performance would the tool show at a sustainable level of resource use, when I made all of the blocks turn green?

The good news is that it looks like we could meet the need for adequate nourishment of 2600 kcal per day for all people at a sustainable level of resource use (though this aggregate value says nothing about inequality within countries).

The good news is that it looks like we could meet the need for adequate nourishment of 2600 kcal per day for all people at a sustainable level of resource use (though this aggregate value says nothing about inequality within countries).

The bad news is that the levels of social performance associated with sustainability for the other ten social indicators are all below – far below, in some cases – reasonable definitions of a good life. I was surprised and dismayed to find that the basic need of improved sanitation (basic toilet facilities) has the largest gap between the thresholds we chose (95% with access) and the level consistent with sustainable resource use (60% with access). The level of secondary education is similarly unacceptable (66% enrolment).

So how do we get to a world where all people live well within the limits of the planet? The changes needed are things that Oxfam has been advocating for many years, in particular since Kate Raworth proposed her doughnut-shaped framework in 2012. The changes include dramatically reducing inequality, improving social cohesion, revitalising democracy, and rapidly switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy. But most of all, there is an urgent need to shift the goal of our economies away from the blind pursuit of growth, which is no longer improving people’s lives in wealthy nations like the US and UK, and towards the meaningful pursuit of a good life for all within planetary boundaries.

February 19, 2018

Top tips on how to get a reply to your emails

Some of my LSE students are pulling their hair out. A number of them are doing consultancies for various bits of the aid industry. They have composed their requests for interviews, links, suggestions etc, hit ‘send’ and then…. Silence.

aid industry. They have composed their requests for interviews, links, suggestions etc, hit ‘send’ and then…. Silence.

So short of doorstepping the unresponsive (which will probably get you arrested), how can you maximise your chances of getting a reply to your email? I tweeted the FP2P hivemind and got dozens of replies, many from the kinds of people students are probably trying to contact. Here’s what they said:

Obvious but important:

Get the grammar and spelling right – it’s amazing how many emails I get with my name misspelt. That doesn’t make you feel like answering

Have a specific question. Don’t say “I am interested in development and am hoping you can help.” (Sarah Lucas)

Timing:

Aim to be on the top of their morning email backlog, so hit send about 7.30am. Avoid weekends.

Tone:

Strike the appropriate balance between informality and formality: ‘Dear Sir’ is likely to be OTT (and they will think it’s a roundrobin) but don’t go the ‘Hey, Bob’ route either – no first names if you’ve never met them! (Shabana Abbas, Sophia Murphy)

Get to the Point:

Get the ask in the subject line. “Request for interview from Financial Times.” (Alan Beattie, but then he does actually work for the FT – an alternative for students might be ‘Professor X suggested I get in touch’).

Brevity! If one has a lot to say, one should place it in an attachment or in the second iteration of emails. (Diane Coyle, Michael Clemens)

Brevity! If one has a lot to say, one should place it in an attachment or in the second iteration of emails. (Diane Coyle, Michael Clemens)

Don’t waffle about your values (Lesley King)

The Right Kind of Flattery:

“I have been deeply inspired by your seminal paper/work in …” (Dani Rodrik, presumably tongue in cheek)

If they are super busy, they will have a swiss cheese memory (lots of holes). Try “I will never forget your wise words, and your request to lean on you when the time came.” (Paul O’Brien)

Think about their constraints:

Don’t ask for a chat unless you really mean it. And then say how long you expect the interview to last (take a real estimate, then halve it!). They may find a skype call less disruptive (and easier to end) than a face to face meeting.

Use other channels in parallel:

‘Experience from my business research. Send letter then follow up email. Time email and mail to land Friday AM.’ (Wayne Diamond)

If your targets are active on social media, engage with them before sending an email – retweet their stuff or leave intelligent comments on their blogposts. Then you’ll have a better chance of name recognition (me).

And if all else fails:

Pretend to be a funder! Works for me (Nicholas Colloff, but then he is actually a funder)

And some things I wasn’t convinced by:

Don’t say you’re a student? Offer help? Try and incentivize them/convince them it is in their interests to reply?  Personally, the ‘we were all students once’ sympathy card works better for me than ‘it’s your lucky day, you get to be interviewed by me.’

Personally, the ‘we were all students once’ sympathy card works better for me than ‘it’s your lucky day, you get to be interviewed by me.’

Also not convinced by ‘If the person they are trying to contact has a PA, approach the PA first for help.’ Isn’t a PA’s job to stop his boss saying yes to this kind of thing?

And here’s how the military do emails, according to the Harvard Business Review (ht Joshua Williams and Paul Niehaus)

Over to you – more tips please!

February 18, 2018

What to read on Oxfam’s sexual misconduct crisis?

Like anyone else connected with Oxfam, I’ve been glued to the media, and my emails over the last 10 days. It’s been pretty harrowing, a crushing dissonance between the revelations of sexual misconduct in our responses to emergencies in Haiti, Chad and elsewhere, and what I know of Oxfam’s focus and work on gender, women’s rights and working with women’s organisations, based on my 14 years with the organization.

Winnie Byanyima, Oxfam International’s Executive Director, captured how we all feel right now

Some of you have asked me to comment, but I’m not sure I have that much to add to some excellent commentary by others. I’ve never worked on the humanitarian side; nor do I have any particular inside track – one of the joys of my role of ‘pointing outwards’ for Oxfam is that I spend my time reading, blogging, writing and talking to non-Oxfam people, rather than sitting in loads of internal meetings. As you can see from FP2P, I’ve been carrying on with that role (with some relief) over the last week.

But after a while the elephant in my study becomes too big to ignore, so here are the pieces that I have found most illuminating (rather than infuriating) on what Oxfam is now calling its ‘sexual misconduct crisis’.

Oxfam’s response:

In addition to heartfelt expressions of shame and remorse, here are the concrete actions we are proposing (some of them quite far-reaching) to put it right.

This is not an argument for cutting aid or defunding Oxfam:

Zoe Williams: ‘Nobody whose serious interest is in the welfare of the girls and women of Haiti and Chad wants to see aid workers shut up shop and go home. There is a principle behind international aid: it’s not a wing of soft, diplomatic power to further Britain’s interests, as Boris Johnson has it, nor a way to “kickstart growth and development” and give us better trading partners, as David Cameron maintained. It’s the manifestation of a driving moral imperative to help another person in desperate need, whether suffering from natural disaster or manmade violence.’

Megan Norbert, who suffered a horrendous experience while with a humanitarian organization (not Oxfam) in South Sudan: ‘I feel quite strongly that dragging down the sector serves no purpose. Despite having been harmed while undertaking humanitarian work, I feel no ill will for humanitarian action as a whole; the hundreds of survivors I communicate with on a regular basis express similar feelings. What will help is pushing for more change, encouraging humanitarian organisations to act, and providing them with the resources to do so.’

Owen Barder set out his thoughts on twitter: ‘It can be harder to uncover and tackle abuse in a sector in which many of its supporters and employees feel strong affinity to the mission. People are reluctant to undermine the institutions This has led to cover ups in churches, politics, trade unions, and in NGOs…..It would be especially paradoxical to single out @oxfamgb which has fought an important fight for women and girls, and for rights, and against sexual abuse around the world. They are a key voice against abuse in the aid sector and in society.’

Heck, even Jeremy Clarkson weighed in (gated).

How to stop abuses in humanitarian response:

Save the Children UK’s Kevin Watkins argues that ‘an international registry of humanitarian workers backed by a “passport system” would enable us to prevent individuals exploiting recruitment loopholes. The UK’s large international development agencies could also come together to create a global centre on child safeguarding and sexual exploitation, working in cooperation with DfID and national authorities to prevent problems and support victims.’

Mike Edwards believes this should galvanize the push to localize spending and power: ‘For at least the last 25 years there has been a lively debate about power, aid and NGOs, focusing on the inability or unwillingness of agencies to hand over control and share their resources—as opposed to building their own brands and competing for market share from their fundraising base in the global North, and notwithstanding the recent trend to decentralize some parts of their operations. There are echoes of this debate among the friendlier critics of Oxfam since the Haiti scandal broke. The central issue is that, while NGOs are happy to criticize inequality when it is caused by others—billionaires for example, or the World Bank or multinational corporations—they have not been prepared to face up to the inequalities for which they themselves are at least partly responsible.’

Why is Emergency Response so prone to abuses?

Maggie Black in New Internationalist: ‘These environments are invariably chaotic, lawless, violent and deeply unequal. The people hired to work in such settings frequently have to face down warlords to get access to victims, argue aid convoys through armed checkpoints, risk their lives, and sometimes lose them, in the effort to bring relief to vulnerable people. Those able and willing to do those things often have a go-getting, driven and macho mentality. And this can lead to the creation of a dysfunctional and testosterone-loaded micro-culture…. To do the work on the ground, teams of itinerant workers are hired on short-term contracts and deployed in the world’s multiplying hot-spots. These conditions are where the micro-culture of aid dispensation is most vulnerable to abuse. The situation exerts huge pressure on human resources management.’

Wider Reflections:

Tim Harford on outrage as a positive feedback loop, feeding off itself.

Finally, the other, heroic, side of our Haiti response: the wonderful Yolette Etienne on Channel 4 News

And in the unlikely event that you still want more, here’s Aidnography’s regularly updated guide to the coverage (60 resources and counting)

February 15, 2018

Why the Aid Community needs to step up on Fragile/Conflict States

Everyone in the aid biz is talking fragile and conflict affected states these days (FCAS – I’ve given up on trying to get

The only way is up?

everyone to adopt FRACAS….). That’s partly because that’s where poor people will predominantly be in a couple of decades time, as more stable places grow their way out of extreme poverty, and partly because of the link to the security agenda that so fixates many governments – the ‘hotbed of terrorism’ argument.

That could be a problem. I would go as far as saying FCAS could be the graveyard of the aid business, because they are the hardest places to work/get results in. Traditional cooperation with states is more likely to go wrong. The focus on ‘zero tolerance of corruption’ is more likely to blow up in our faces. Aid is often concentrated at the short term humanitarian end of the spectrum, when conflicts and fragility are often prolonged. Expat staff (especially the more experienced ones, who are more likely to have family commitments) often prefer posts in Paris or Delhi, not Kabul or Goma. And other traditional aid partners like the private sector or Civil Society Organizations are often also weaker in such places.

Anxieties over this direction of travel may be one reason for the injection of research funding. I’m involved in two projects – Action for Empowerment and Accountability is investigating how social and political action occur in FCAS, and the LSE’s Centre for Public Authority in International Development (CPAID) is trying to understand how power operates in such places.

The OECD’s 5 axes of fragility

But where do you go if you want a broader overview of FCAS – eg how they vary; the historical accounts of ‘turnaround’ countries that have somehow escaped from fragility and conflict; the comparison of how different aid approaches do (or more often don’t, and sometimes even make things worse) work in such messy places; an understanding of who else wields power when states are either absent or predatory, and whether we can work with them?

The answer is not obvious. Research is driven by funding, and funding is generally for new research, rather than for providing a repository of wisdom, experience and advice. Those are often an almost accidental accompaniment of research – you get a bunch of researchers in a university or thinktank, and their body of knowledge and experience becomes a place others can tap into, but it is on top of their day jobs (churning out new papers).

It’s like a large scale version of the conversation I once had with our outgoing Afghanistan gender adviser. We met by accident in Dubai airport, and she told me that typically expats in Afghanistan work a couple of years, then leave, either through burn out or because they are on short term contracts. Then new arrivals start the learning process all over again (often including repeating the same approaches and discussions of the previous years – at worst, producing a Groundhog Day of ‘steep learning curves’, followed by loss of the accumulated knowledge. Then repeat.) Can’t we do better than that?

Looking more broadly, I see aspects of such an institution elsewhere – for example the International Growth Centre

may not be enough……

pulls together different disciplines to look at markets and growth, or the GSDRC is a resource centre that responds to donor requests for literature and the like. But otherwise, wisdom and experience seem to be concentrated either within institutions, or in informal networks and individuals – I started thinking about this during a conversation with fellow aid greybeard Steve Commins, who mentioned that people at the World Bank, DFID and INGOs sometimes see him as the institutional memory, even though he doesn’t work for them any more – he’s become the guy who points out that the Bank actually ran projects and research on a given subject 15-20 years ago, which everyone’s forgotten as the staff with experience are rotated onwards again and again until the knowledge has evaporated, and the Bank/DFID/INGO is about to do it all over again.

If FCAS really are the future/cemetery of the aid business, surely it should step up its ideas on this? A FCAS Centre could:

Act as a convenor, bringing together what we know about how FCAS function, history, turnarounds etc, and the past and present of aid interventions there. It would draw on different disciplines and players, researchers and practitioners etc.

Balance the larger debate with practical support and exchanges on programme design and experimentation on shared problems like how to overcome the intractable divide between short term humanitarianism and long term development programming.

Support those FCAS governments seeking a better deal from the international system.

Plug into local sources of knowledge in different countries, to ameliorate the impact of staff turnover.

From Oxfam’s point of view, I’d hope it could include some of the vital issues such as gender rights or civil society space, which keep slipping off the FCAS agenda, and yet could offer new ideas and solutions.

A child holds up bullets collected from the ground in Rounyn, a village about 15 kilometres from Shangel Tubaya, North Darfur. Most of the villages population has fled to camps for internally displaced because of heavy fighting between Government of Sudan and rebel forces.

It could also tackle some of the institutional problems that bedevil aid in fragile states – high levels of staff turnover, risk aversion, the unintended negative consequences of the results and value for money agenda (results tend to be even more unpredictable, slower, and aid more expensive than in more stable settings).

It might not work of course – it could become some opaque institution of little tangible benefit, a creature that is not unknown in the aid business. But given what is at stake, isn’t it worth a try? And if aid organizations can get more savvy at working in these messy places, there’s likely to be useful lessons for working in the more stable Zambia/Malawi type places too.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers