Duncan Green's Blog, page 220

March 6, 2013

Attack? Equivocate? Engage? How Big Food responds to a tough new campaign

Chris Jochnick, director of Oxfam America’s Private Sector Department (twitter: @cjochnick), reflects on the different corporate responses to our ‘Behind the Brands’ campaign launch

‘Behind the Brands’ campaign launch

Companies have had decades to hone their engagement strategies with activists, but still struggle to find the right approach. Initial reactions to Oxfam’s Behind the Brand campaign offer an interesting case in point. The campaign is only a week old, so these are early days – but already we can see certain styles emerging.

Behind the Brands is an aggressive effort to link consumers and the public with their most popular food brands around the enormous environmental and social “footprint” of the food and beverage industry. The campaign launched last week in countries around the globe with a flagship report, a scorecard (below) ranking the “Big 10” food and beverage companies, an interactive on-line platform to encourage public action, and various “visibility” activities at company headquarters. Media took notice, with stories in the NY Times, BBC, NPR, Businessweek among dozens of others. In the first 24 hours, 250,000 people visited the web-page; after a week, 10,000+ have taken some kind of action directed at the companies.

Oxfam was not out to blindside or gratuitously offend. We’ve worked with F&B companies in the past and expect to collaborate in the future. We spent months consulting with the companies about the Scorecard and let them know in advance what they could expect.

So how have the companies reacted? Typical responses to a campaign can be grouped into three categories: (a) defensive (b) equivocal and (c) engaged. In this case, we’ve seen evidence of all three.

So how have the companies reacted? Typical responses to a campaign can be grouped into three categories: (a) defensive (b) equivocal and (c) engaged. In this case, we’ve seen evidence of all three.

On the defensive, Associated British Foods, the Scorecard’s worst performer, came out swinging to the Guardian: “The idea that ABF would use a “veil of secrecy” in order to hide the “human cost” of its supply chain is simply ridiculous. We treat local producers, communities and the environment with the utmost respect. As for transparency … our next CR report in autumn 2013 will confirm significant improvement in disclosure.” Mondelez wasn’t too far behind, issuing a short response and sending police out to greet our pamphleteers. Only one company – Danone – opted to ignore the campaign completely – a form of passive defensiveness. These are pretty modest steps (to get a contemporary flavor for what companies are capable of, see this bit about Chevron), but do suggest a path of resistance that will only provide the campaign with grist for escalation.

Most companies have taken an equivocal stand, publicly recognizing the importance of the campaign issues, offering olive branches, and touting their corporate citizenship bone fides. The official response from Mars is typical: “Mars takes a comprehensive approach to this issue, with a strong focus on the entire farming community specifically in the area of cocoa sustainability. Our leadership has had a positive impact on the women, children and families of smallholder farms. Oxfam highlights important issues in their report and we look forward to working with them to address these critical issues.” As a first step, equivocating may make most sense. It avoids any commitment and keeps a door open to engagement.

It is too early to characterize any of the companies as “engaged”, but there are some positive signs (see responses here). Pepsi’s CEO went out to meet Oxfam pamphleteers at Pepsi headquarters and spent 30 minutes discussing the campaign. Nestle provided a fairly substantive response and, along with Pepsi and Mars, has been receptive to immediate dialogue. These are helpful openings.

In the face of protests, companies will often start defensively or equivocally, hoping to wait out a campaign. Oxfam has found that even companies with visionary leaders, scoring high marks on corporate social responsibility, will often balk reflexively at outside pressure. Pride, inertia, fear of the unknown may all contribute. We saw it play out with the iconic CSR leader Howard Schultz, who resisted for months Oxfam’s push to dialogue with the Ethiopian government around coffee branding rights, even in the face of media, shareholder, barista, consumer and public pressure. In conversations with Starbucks executives afterwards, it was evident that their deeply-rooted belief in the “goodness” of the company made it more difficult to “hear” or respond to outside criticism.

Companies will also resist campaign demands that require ceding some control. All of the Big 10 voice support for small farmers and sustainability, and many have good projects in the field. Companies are responsive to pressure around these projects and will eagerly (necessarily) partner with NGOs. Campaigns for transparency, due diligence, and worker/stakeholder rights – those issues at the heart of Behind the Brands – are a tougher sell. Companies are reluctant to identify suppliers, or sourcing volumes or auditing performance; to measure and report on how women and small-holder farmers are faring; or to acknowledge their human rights responsibilities. But these are the building blocks of real accountability.

Companies will also resist campaign demands that require ceding some control. All of the Big 10 voice support for small farmers and sustainability, and many have good projects in the field. Companies are responsive to pressure around these projects and will eagerly (necessarily) partner with NGOs. Campaigns for transparency, due diligence, and worker/stakeholder rights – those issues at the heart of Behind the Brands – are a tougher sell. Companies are reluctant to identify suppliers, or sourcing volumes or auditing performance; to measure and report on how women and small-holder farmers are faring; or to acknowledge their human rights responsibilities. But these are the building blocks of real accountability.

Behind the Brands aims to overcome this resistance by strengthening consumer and public voices. Consumer-facing companies like the Big 10 have to balance accountability concerns with risks to their brands – by far their most valuable asset. Defensiveness in the face of reasonable public demands will eventually take a toll. Oxfam knows that many consumers care about where their food comes from; if we can get enough of those consumers to think twice before making choices, companies will have to take notice.

Some company leaders already recognize a business case for treating farmers and planet well. And they know that transparency in this age is unavoidable. These companies will see dialogue with credible critical voices as an opportunity. Oxfam is counting on a handful of these companies to fully engage with the Scorecard – and all the issues underlying it — as a means towards strengthening their brands and business.

March 5, 2013

What I’m up to – podcasts, videos, speaking in UK, South Africa, US

We interrupt this blog for a brief commercial….. Been doing a lot of multimedia ranting recently, and have FP2P promo tours coming up in South Africa and the US, as well as UK. Here’s what I know is out there.

First up, I was subjected to a viva-like experience by Owen Barder, being grilled for an hour for his podcast Development Drums. The result is now out, either as an MP3 download, or as a transcript. Haven’t listened to it yet (there are limits, even to my self obsession), but I’ve heard good things about it and I certainly enjoyed it at the time – Owen had read the book carefully, and quickly got to the heart of some of the dilemmas it raises.

Then there’s been a spate of videos of different lengths. On Post2015, I’ve already linked to the IDS presentation, but there’s also a 3 minute pitch for schools. Filmed in a freezing Brixton cafe (so trendy it didn’t actually have a front wall), so I distracted myself by pulling silly faces. So of course they used it. Hey ho.

On the seemingly endless FP2P tour (c/o the hyperefficient Sarah Minty), here’s a typical presentation from last week at the University of East Anglia. IDS tomorrow, Sheffield on Thursday.

This weekend I’m off to South Africa. Details on Oxfam in South Africa’s Facebook page. Public events in Joburg (WITS Mind the Gap) and Cape Town (Stellenbosch).

Then at the end of April, it’s Boston (29 April-1 May), New York (2-3 May) and Washington DC (6-9 May). Various things confirmed, but some spaces still left, so if anyone is interested in hosting a lecture in those cities let me know.

Think that’s it – have I forgotten anything?

Update: And another – 3 minute talking head on development and justice, for UEA

March 4, 2013

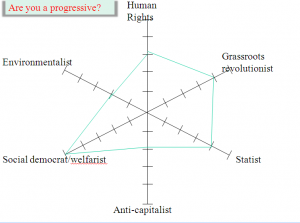

Are you a Progressive? If so, what’s your footprint?

I get irritated sometimes when a nameless Oxfam colleague (and no, there aren’t any prizes for guessing) asks ‘yes, but are you/they left wing?’, to which I of course, respond ‘depends what you mean by ‘left wing’’ (I think he finds me pretty annoying too). So in an effort to improve on this rather un-nuanced discussion, how about moving from 1D (left-right) to two (are you a progressive?). Off the top of my head, here are six plausible axes for assessing your degree of progressivity on development issues:

Grassroots Revolutionist: your priority is celebrating and supporting grassroots movements eg Occupy and the Arab Spring

Statist: you see state control of the economy, hands on industrial policy, and a high degree of regulation as the core to development

Anti-Capitalist: you know what you oppose (capitalism, large transnationals etc)

Social Democrat/Welfarist: you want everywhere to be like Sweden

Environmentalist: you increasingly focus on One Planet living and the implications for human activity in terms of consumerism, fossil fuel use etc

Human Rights: you focus on the recognition and respect of basic human rights, as set out in international law

Any improvements on the categories? Quite hard to distinguish between ends and means, but then progressives have always mixed up the two. You can try filling out this powerpoint slide (one notch from the centre is ‘a bit’, 5 notches is ‘a lot’, use line draw to fill in your footprint) and let me know what you think of the exercise. Anyone putting five notches on every axis is more likely to be an indecisive wimp than a saint.

I suspect that comparing colleagues’ footprints might help us understand why you some people tend to disagree with each other/get on each other’s nerves.

Since coming up with these axes, I have done some in-depth research with Oxfam India colleagues (OK, we talked over a beer). Turns out (amazing, eh?) that your definition of ‘progressive’ depends on where/who you are. After deep discussion (and another beer), they came up with the following set of axes:

Gender equality

Minority Inclusion (dalits, tribals etc)

Pro-poor deregulation (e.g. scrapping regressive subsidies)

People power (opposing an over centralizing state)

Progressive tax reform

Secularism

Would love to see what other country contexts produce. So here’s a bit of homework – decide your own axes, fill in your progressive footprint, send it in, and I’ll upload the best ones. And here’s mine (for what it’s worth – regular readers feel free to put me straight, and anyway, I would probably arrive at totally different conclusions from one day to the next.) And if anyone has a less clunky way to do the spider diagrams, I would love to hear about it.

My progressive footprint (for now, anyway)

March 1, 2013

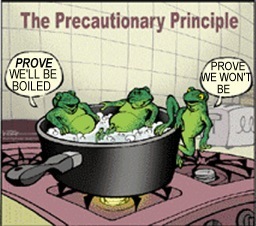

If we can’t prove that speculation drives food prices, should we regulate it anyway?

One of my more wonk-mind-blowing moments last year was refereeing a debate about financial speculation and commodity prices between Oxfam’s Rob Nash and a UK Treasury wonk who wished to remain nameless. I couldn’t understand either of them (even by international development standards, the language is really weird – try ‘contango’ or ‘backwardation’). I tried to get them to slug it out on the blog, but the Treasury type declined.

Nash and a UK Treasury wonk who wished to remain nameless. I couldn’t understand either of them (even by international development standards, the language is really weird – try ‘contango’ or ‘backwardation’). I tried to get them to slug it out on the blog, but the Treasury type declined.

So it’s good news that Stephen Spratt of IDS (right) has written a blog post and 20 page paper on food price volatility and financial speculation – Stephen is a City poacher turned gamekeeper, and one of the clearest thinkers I’ve come across on financial markets.

The paper considers the case for and against the prosecution. Stephen sets out (and tries to answer) the key questions:

How has the relationship between financial actors and food commodity markets – particularly futures markets – changed in the last ten years?

What have been the benefits and costs of the increased role of financial sector actors in these markets?

How might the balance between benefits and costs change in the future?

What reforms, if any, are needed to ensure that benefits exceed costs?

The paper helpfully unpacks different kinds of ‘speculation’ – lumping them all together is really unhelpful, and assesses the impact of high prices and volatility on different groups (see table).

But the most valuable contribution is his thinking on complex systems. Sure there is a clear correlation between rising food prices, volatility and increased financial market activity in commodities, but proving the causal link between them is a different question. His conclusion: ‘Establishing cause and effect has proven to be impossible.’

The pro-market types consider this enough grounds to oppose regulation of speculation. Stephen disagrees. He argues that we need to think harder about the costs and benefits of action if the critics of financial speculation are right, and if they are wrong. If they are right, and speculation is driving food markets, then regulation would help prevent the extremely damaging social impacts of high and volatile prices. If they are wrong, and we regulate anyway, the damage would be limited. So in a version of the precautionary principle, he comes down in favour of regulation. Here’s his conclusion:

‘The policy responses that different commentators favour are strongly influenced by two things. First, their view on the link between increasing financial speculation in futures market and price movements in spot markets. Second, their view on the relationship between financial market prices and underlying economic fundamentals. Reasonable people take different view on these questions, and it is not possible to answer them definitively. On the balance of evidence, however, we have proposed the cautious use of the precautionary principle, largely because of the fundamental importance of global food markets to the lives of billions of people.

‘The policy responses that different commentators favour are strongly influenced by two things. First, their view on the link between increasing financial speculation in futures market and price movements in spot markets. Second, their view on the relationship between financial market prices and underlying economic fundamentals. Reasonable people take different view on these questions, and it is not possible to answer them definitively. On the balance of evidence, however, we have proposed the cautious use of the precautionary principle, largely because of the fundamental importance of global food markets to the lives of billions of people.

Set against this, the ‘costs’ of placing greater curbs on financial participation in food markets seem relatively trivial. Some argue that reducing speculation would reduce market liquidity, increasing hedging costs. But there has been no reduction in hedging costs as financial engagement has grown. The only real cost, therefore, may be a reduction in the profitability of some financial institutions. Set against the potential benefits, this seems a price well worth paying.’

I’m convinced. You? The next step would be to apply the same precautionary principle/complex systems approach to different kinds of speculation and different forms of regulation – doubtless a very messy argument. Has anyone had it yet?

February 27, 2013

At last, a sensible suggestion for post2015

After my ‘bah humbug’ paper on post2015, I’ve been largely avoiding the subject as a monumental timesuck. However, a combination of Sabina ‘multidimensional’ Alkire and Andy ‘bottom billion’ Sumner is an unstoppable force, so I’m making an exception for their new paper, Multidimensional Poverty and the Post-2015 MDGs, which is worth a skim.

What Sabina and Andy do is use her previous work for UNDP on multidimensional poverty indicators (MPIs) to square an important circle. They suggest building an ‘MPI 2.0’ based on whatever combination of issues is finally agreed in the post2015 discussion. This would produce a single number that summarizes a country’s overall progress towards the post2015 goals.

That in turn would allow the post2015 process to generate more traction on national governments (the lack of which is the subject of my paper) through league tables. Imagine if every year, all countries (including the rich ones) are ranked on a comprehensive human development table that (unlike the Human Development Index and other similar efforts) has buy in and recognition from across the international community. Each annual report would pick out the countries that have risen/fallen relative to the others. Regional tables could compare India and Bangladesh, or Peru and Bolivia, to generate extra public interest and pressure on decision makers. Within countries, an MPI could highlight regional disparities (see map).

A particular advantage of the approach is speedy feedback for policy makers: The MPI reflects effective social policy interventions immediately. With measures of income poverty, a positive social change – for example in schooling or clean water – may not be reflected for a number of years.

One of the lasting institutional legacies of the MDG process is the investment in better quality data needed to assess progress – this proposal would build on that.

One suggestion though – MPI 2.0 is a dreadful name. Why don’t we just call it ‘poverty’ and argue that it should replace $1.25 a day as the international standard?

And here’s me at a recent IDS seminar explaining why I’m so underwhelmed by the general post2015 debate.

What is the evidence for evidence-based policy making? Pretty thin, actually.

A recent conference in Nigeria considered the evidence that evidence-based policy-making actually, you know, exists. The conference report sets out its theory of change in a handy diagram – the major conference sessions are indicated in boxes.

its theory of change in a handy diagram – the major conference sessions are indicated in boxes.

Conclusion?

‘There is a shortage of evidence on policy makers’ actual capacity to use research evidence and there is even less evidence on effective strategies to build policy makers’ capacity. Furthermore, many presentations highlighted the insidious effect of corruption on use of evidence in policy making processes.’

i.e. you can have all the arguments you like on the nature of evidence – disciplinary and political bias, what constitutes knowledge etc etc (as this blog recently did), but policy makers are often either unable or unwilling to use it anyway – supply doesn’t guarantee demand.

The aid agencies and research councils that fund research are very keen to promote this shift from worrying about supply to wondering how to boost demand (although the researchers are often less keen – they just want to be left alone to churn out papers and develop their careers). What was nice about this conference was the amount of on-the-ground grassroots research on how decision makers actually use (or more often ignore) research in places like Nigeria (‘political manipulation and ambition seem to be among the strongest determinants of factors influencing policy development processes’) and Indonesia (‘Even if technocratic or political – it doesn’t matter – it’s 90% personality’).

One thing I learned is that agonising over per diems is not confined to the aid business:

‘One particularly heated debate concerned the frequent requests from policy makers for ‘sitting fees’ in order to attend training or seminars which could inform them about research issues. Participants agreed that this practice is widespread in most of the African countries represented; however, opinions on how to respond to this differed. Some suggested that those who aim to inform policy makers about research need to just accept that paying these fees is necessary and should therefore include them in their budgets. However others felt that continuing to pay such fees just propagates the problem and that those funding research communication and uptake work should take a ‘zero-tolerance’ approach.’

On the demand side, the report considers both capacity and incentives. On capacity ‘most people don’t know what they don’t know!’ will resonate with researchers in NGOs trying to convince their colleagues to look harder at the evidence. There’s a mountain to climb: a survey of Zambian parliamentary researchers and librarians (and these had positively agreed that they needed to use research) found that ‘only one in three believed there was consensus that the CIA did not invent HIV’.

‘Research-evidence is often used opportunistically to back up pre-existing political decisions/opinions (confirmation bias)’. That preference for policy-based evidence-making is alive and well in the big aid donors and NGOs too, of course……..

And unfortunately, research from Ghana, Sierra Leone, Uganda, and Zambia concluded that ‘a lack of capacity to understand research was perceived as beneficial to policy makers since it ‘allowed’ them to ignore evidence and instead follow their own agenda. Thus, there is not only a lack of capacity but also a disincentive to build capacity.’ Oh dear.

How to build the incentives to use research, assuming these political obstacles are not insuperable? On HIV policy in Pakistan, DFID ‘built the capacity of civil society organisations representing marginalised groups to demand policy change’.

including policy makers in the design phase of research projects (get them on the advisory board, guys, don’t just see them as seminar fodder once you’ve finished the research)

networks and linkages between researchers and policy makers are necessary but definitely not sufficient

researchers need to change the (often dire) way they communicate their work – in one case study from Ghana ‘photographs of real people suffering from mental illness is far more powerful in influencing opinions than any policy brief could be.’ (Well duh)

target the ‘policy entrepreneurs’ with influence over decision-makers (the Minister’s old university professor etc)

‘There is a tendency for researchers and research intermediaries to focus their communication efforts on elected representatives and appointed officials but to ignore the crucial role that technocratic staff play.’

All good stuff, but the report reminded me of the governance debates of a few years ago, in that even though it recognized the problem is incentives and politics, kept drifting back to the comfort zone of supply issues (if they don’t want research, we just have to get better at communicating or building their capacity), rather than thinking harder about the demand side. For example:

Anyone involved in advocacy knows that the openness of policy makers to new ideas is episodic, and linked to things like changes of administration, scandals, crises and failures. So how does research need to be redesigned to capitalise on such brief windows of opportunity?

Opposition parties are often much less well resourced, and much more malleable in their thinking as they cast around for clever ideas that will help them win power – to what extent should researchers concentrate on those without power, rather than those currently in office?

Young minds are (generally) more open to new ideas than old ones: should researchers target future leaders (who are pretty easy to identify by faculty and university) rather than waste their time on the current generation?

The evidence debate, you won’t be surprised to hear, continues……

February 26, 2013

Beyond Horsegate: comparing the supply chains of the big 10 food companies

Erinch Sahan (right), a private sector policy advisor at Oxfam GB, introduces Behind the Brands, a big new report and company scorecard, launched today.

scorecard, launched today.

So we didn’t know we were eating horses. What else don’t we know about the supply chains delivering our food? 18 months ago, Oxfam posed this question to the Big 10: the world’s 10 largest food and beverage companies. In alphabetical order, they are Associated British Foods, Coca Cola, Danone, General Mills, Kelloggs, Mars, Mondelez, Nestle, Pepsico and Unilever. Today, we launch the results of our research and make it the centre piece of a brand-spanking new campaign: Behind the Brands.

The results aren’t pretty. The Big 10 seem unengaged with their supply chains (they don’t seem to know what’s going on and how to address it). Nor do they tell us much about where their commodities come from and next to zilch about how they use their power to shape the behaviour of suppliers. We came up with numbers to show this and ranked them across some important issues. This is how we did it.

7 critical themes

We chose seven themes that directly or indirectly change conditions for the poorest people in the food system: women, small-scale farmers, farm workers, land, water, climate, and transparency; asking whether the Big 10 are:

improving conditions for women, small-scale farmers and farm workers;

promoting equitable and sustainable access to and use of land and water;

reducing emissions and helping farmers adapt to climate change; and

being transparent about their supply chains and broader corporate activities

How the Big 10 stack up

After 18 months of analysis by Oxfam – and a long process of consultation with academics, industry experts, Oxfam staff on the ground, organisations working on international supply chains and the companies themselves – we came up with the following scores:

So what lies beneath these scores? The following questions transcend the themes and form the back-bone of the scorecard.

Are they telling their suppliers to do the right thing?

Most of what goes into the products does not come from farms operated by the Big 10. So the most important issue is how they shape the behaviour of their suppliers. On this point, the most relevant documents are their supplier codes (and supplier guidelines), which contain the standards they ask their suppliers to meet. An example is Unilever’s Sustainable Agriculture Code, which tells its suppliers to work with farmers’ groups to provide training to farmers and to provide safe working conditions for workers.

We had two problems in assessing supplier codes. Firstly, we cannot know if the codes are enforced, partly due to a lack of transparency around the auditing of suppliers. Secondly, most of the codes contain little meaningful detail. So we could not rely on supplier codes alone and had to broaden the scope of our scorecard.

Are they aware of the broader issues?

Across the themes, we assess if the Big 10 recognize the challenges faced by agricultural communities. For instance, under the women theme, we rewarded Coca Cola, Nestle, Pepsico and Unilever for publicly acknowledging that women lacked access to training related to food markets and for recognizing that small-scale farmers need assistance in adapting to climate change. While this can seem disconnected with their actual practices, for a company to address a problem, it must at least be aware of it.

Do they know details of their own supply chain?

Do companies know the relevant details of their supply chains? A company that knows where there is poorer land governance, will know it needs to focus on that part of its supply chain; a company that identifies water-stressed regions that they operate in is better equipped to channel its efforts.

Are they committed to improving conditions? Once they identify an issue, we want to see a company commit to tackling it. This could be a target or a general commitment to tackling a problem. For instance, under the water theme, we rewarded nine of the Big 10 for setting a target to reduce water use in their own operations (since this impacts availability of water for local farmers). In farmers, we looked for a commitment to ensuring that small-scale producers receive a price that allows them to earn a decent income (none of the Big 10 does this).

Once they identify an issue, we want to see a company commit to tackling it. This could be a target or a general commitment to tackling a problem. For instance, under the water theme, we rewarded nine of the Big 10 for setting a target to reduce water use in their own operations (since this impacts availability of water for local farmers). In farmers, we looked for a commitment to ensuring that small-scale producers receive a price that allows them to earn a decent income (none of the Big 10 does this).

Do their projects address core issues in their supply chains?

The Big 10 are active in philanthropic projects but we focused on whether they are doing anything to address the core issues in their supply chains. For instance, we looked for projects that improve farmer productivity, women’s empowerment, wages, land rights, resilience to climate change and access to water (we have a long list). Under most themes, we also required that they work with a relevant organisation, such as a local union or a farmers’ organisation. Few of the projects conducted by the Big 10 met our criteria.

What remains unanswered

Whether the Big 10 use their power to make their suppliers do the right thing is not very clear. It is hard to get information about who they do business with and exactly where the commodities in their products come from. We know even less about how they engage with their suppliers and, after assessing information in the public-realm, are left with unanswered questions such as:

How much emphasis do they put on social and environmental issues when negotiating contracts?

Do they know how much it would cost for their suppliers to do business responsibly and do they pay enough to allow this to happen?

How much information do they provide to their suppliers in terms of advance notice of upcoming orders and quality requirements?

Who bears risks relating to transport and weather-related disruption and fluctuating demand?

Greater transparency about how they manage these issues with suppliers is an essential first step – starting with some facts on whether and how they incentivise their buyers to take account of these issues. Until the Big 10 stop hiding behind the excuse of “commercial sensitivity”, they are not serious about being held to account for their power to improve the lives of the marginalised, many of whom are growing the food we eat.

how they incentivise their buyers to take account of these issues. Until the Big 10 stop hiding behind the excuse of “commercial sensitivity”, they are not serious about being held to account for their power to improve the lives of the marginalised, many of whom are growing the food we eat.

What do the Big 10 need to address?

The Big 10 have several gaping holes in their policies but Oxfam suggests that they prioritise taking action as follows:

1. Make explicit commitments to recognize and fix the injustices in their supply chains.

2. Identify areas of high risk and analyze and disclose their impact on supply chain issues.

3. Make clear their expectations of their suppliers and support them to do their part to fix the injustices.

Erinch Sahan led the team across Oxfam International that put together the scorecard.

February 25, 2013

Community-based tourism in Ethiopia – aka where I’ve been for the last two weeks

Just got back from something of a busman’s holiday – two weeks in Ethiopia with my wife Cathy. The highlight was some community-based tourism, a magical four-day trek across the highlands near Lalibela.

First the community bit. The trek consisted of daily walks, with the next village providing a donkey for the bags (v welcome at 3000 metres), a donkey minder + local guide (we also had an English speaking guide from the central CBT organization – see below). Pic right, as promised. Every night we stayed at comfortable purpose-built huts. The community got about 40% of the $600 we paid for the four days, (lots of elaborate writing of receipts etc as our guide handed over the cash) plus about another $100 in the tips we were encouraged to hand over directly (I was less comfortable about this, but we were assured it was acceptable and transparent).

metres), a donkey minder + local guide (we also had an English speaking guide from the central CBT organization – see below). Pic right, as promised. Every night we stayed at comfortable purpose-built huts. The community got about 40% of the $600 we paid for the four days, (lots of elaborate writing of receipts etc as our guide handed over the cash) plus about another $100 in the tips we were encouraged to hand over directly (I was less comfortable about this, but we were assured it was acceptable and transparent).

Each day would end with a conversation by the flickering light of a eucalyptus wood fire, with community leaders, cooks, or whoever else was around. The exchange was more relaxed than the structured interviews of a work field trip, with a bit more two way conversation (we were particularly stumped by trying to answer ‘so what is the motor of the economy in London, where you live?’).

And the tourism bit was wonderful, as we worked our way across the Meket Escarpment an hour south of Lailbela – a plateau of flat  fertile farmland, edged by plunging cliffs and heart-lifting views (particularly from the toilets at each campsite – nice touch. See pic left). No electricity for 30 miles, so the stars were unbeatable (saw a bright red shooting star for the first time in my life). Great birds for the twitchers (Abyssinian Ground Hornbill? No problem) troupes of lion-maned Gelada baboons, a family of rock hyraxes sunbathing next to one camp site.

fertile farmland, edged by plunging cliffs and heart-lifting views (particularly from the toilets at each campsite – nice touch. See pic left). No electricity for 30 miles, so the stars were unbeatable (saw a bright red shooting star for the first time in my life). Great birds for the twitchers (Abyssinian Ground Hornbill? No problem) troupes of lion-maned Gelada baboons, a family of rock hyraxes sunbathing next to one camp site.

But the highlight was the encounter with two priests of the ubiquitous Ethiopian Orthodox Church, pickaxes in hand, digging a series of underground churches out of solid rock on the flanks of a remote and huge canyon. The centuries-old ‘Rock-hewn churches’ attract thousands of tourists to Lalibela, but Gebre Meskel and his younger companion had decided to build some new ones, which they’ve christened Debre Sion. They’ve been at it for a year now, and reckon they will open for services within another year. Meskel has nothing on paper, just a design in his head, with lots of plans to start more churches once this series of underground chapels and connecting tunnels is complete. Initially, their colleagues were sceptical, but now just a couple of hours’ walk away, the priests are hailing a miracle – for how else could two men with handtools build an underground church this fast? Wild.

But these kinds of anecdotes don’t capture the cumulative impact of the walks, the sights and the

conversations. At times it felt like a mobile immersion, and by the end I was quite overwhelmed by the human drama, the combination of undoubted progress and daily grind and above all the beauty, both human and natural.

If you want to go, contact the Lasta Lailbela Community Tourism Guiding Enterprise (LLCTGE). Conversations with other trekkers suggest it might also be worth talking to (or specifically asking for) our guide, the endlessly patient and helpful Temesgen Damtew Tsegaye – temesgendamtew[at]yahoo.com (right – yep, the huts even had beer). More on Community-based Tourism here, but what I can’t find is any directory to help you identify good CBT projects, hopefully including next year’s holiday. Any suggestions?

February 12, 2013

Off on holiday. It involves a donkey. Back in a couple of weeks.

Exhausted by the ferocity of the evidence debates, I am off for an African holiday. I believe a donkey is involved at some point. Pics may follow.

February 11, 2013

Aid and the private sector: a love story

Oxfam private sector adviser Erinch Sahan (right) summarizes a critical new review of the growing interlinkages between aid and the private sector

Oxfam private sector adviser Erinch Sahan (right) summarizes a critical new review of the growing interlinkages between aid and the private sector

Donors have a new love: business. And it will end poverty. Aid chiefs across the world have concluded that if we need growth to end poverty and the private sector drives growth, isn’t aid most effective where it focuses on the private sector?

Well, no. At least not usually. And a new report from Canada sheds light on why.

The Canadian Council for International Co-operation and the think-tank the North South Institute have assessed the policies of donors towards promoting growth and the private sector. They break down (very adeptly) what the OECD donors are doing, how they’re thinking about the private sector and where they are falling short. It’s not only a sorely needed assessment of the rise and rise of private sector-focused aid, it also reminds us that aid is increasingly promoting a very specific economic model (thy name is neo-liberal capitalism) with some questionable assumptions that should attract serious scrutiny.

You can read the report here but here are some highlights, along with a few thoughts from me.

Just feed the growth machine

Donors are focused on plain old growth. They don’t have a meaningful approach to improving the distribution or pro-poor impacts and too often merely pay lip-service to issues to do with the quality of growth. They’re not linking possible interventions; such as support to government capacity to protect labour rights, effectively collect taxes and redistribute the benefits of growth; with their private sector programmes. In addressing gender, too often they simply focus on getting women into markets, ignoring the social and political drivers of gender inequality. And direct support to the poorest and most marginalised is falling out of favour.

OJ or kool-aid?

While the donors may differ on their rhetoric (some are good at sprinkling in buzz words like “inclusive” and “sustainable” when discussing growth), their private sector work ends up looking eerily similar. French and Belgian aid goes furthest in prioritising equality and accompanying growth with social services. However, for most donors, private sector programmes are effectively stand-alone growth feeders. The report reminds us that sustained growth in many developing countries (particularly in Africa) has failed to put a dent in unemployment. Growth driven by extractives is one such example that’s cited. So just feeding the growth machine doesn’t automatically mean the poor will benefit.

Can aid really drive growth?

The report finds that donors focus on interventions at the macro (e.g. business enabling environment and international CSR support) and meso (e.g. PPPs and financing investments) levels. However, it’s the micro-level programmes (e.g. training women farmers) that “have a much larger redistributive impact for poor and marginalized populations”. But can aid money really be a (meaningful) driver of growth? Why not focus on helping the most marginalised, rather than obsess over catalysing broader economic growth?

Win-win-win-win… always

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) are the new black. For OECD DAC members, PPP spending has risen from US$234m in 2007 to US$903m in 2010. Donor strategies suggest they represent wins for everyone: recipient governments, business, donors and NGOs. But donors seem to ignore the complexity of interests and agendas among those involved in PPPs. The pitfalls and inefficiencies of PPPs are scarcely mentioned and the politics of the PPP negotiating process is swept under the rug. This, I suspect, comes from an ideological underpinning to private sector strategies, which holds that business interests are aligned with development interests. Donors need to be reminded that this is only sometimes the case.

Crony capitalism?

Donors are also looking to include their national firms in their private sector strategies. For example, Australia’s Mining for Development programme (AU$127m) partners with Australia’s mining giants on a range of projects in developing countries. Denmark’s Business Partnerships programme and the UK’s Food Industry Retail Challenge Fund are only open to national firms. This all seems dangerously like a veiled attempt to subsidise the foreign investment and CSR strategies of national companies – as long as some development story can come about. And isn’t this neo-tied-aid? In the report’s own words “Donors sometimes favour their own commercial interests to the detriment of developing countries’ domestic policies for development.” Without more transparency around decision-making and a clear results framework for private sector partnerships (the report finds this is sorely lacking), we are left to interpret decisions and priorities as cynically as we’d like (I bags the cynical view).

programme (AU$127m) partners with Australia’s mining giants on a range of projects in developing countries. Denmark’s Business Partnerships programme and the UK’s Food Industry Retail Challenge Fund are only open to national firms. This all seems dangerously like a veiled attempt to subsidise the foreign investment and CSR strategies of national companies – as long as some development story can come about. And isn’t this neo-tied-aid? In the report’s own words “Donors sometimes favour their own commercial interests to the detriment of developing countries’ domestic policies for development.” Without more transparency around decision-making and a clear results framework for private sector partnerships (the report finds this is sorely lacking), we are left to interpret decisions and priorities as cynically as we’d like (I bags the cynical view).

The report makes a plethora of sensible recommendations, including the need to support democratic ownership of the growth agenda and ensure additionality in private sector development programmes (ie; that an investment, CSR approach or any job-creation wouldn’t have happened even without the programme). But what comes flying off the page is the need to question fundamental assumptions about growth and aid. Some questions that I’m left with are:

What type of growth should donors be promoting?

Can aid really drive growth?

Are aid bureaucrats equipped to do business with business (e.g. through partnerships and PPPs)?

Why doesn’t aid focus on building the rights and power of the most marginalised?

What do you think?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers