Duncan Green's Blog, page 97

April 24, 2018

Book Review: Can Intervention Work? Rory Stewart and Gerald Knaus

We’ve had some great speakers at the LSE this year, but Rory Stewart was top of the pops, according to the students’  evaluations. He rocked up at LSE, despite having just been reshuffled to Minister for Prisons, spoke without notes, and blew everyone away. Alas, he insisted on it being off the record, so I cheated – I went back to the 2011 book that provided the material for his talk. It’s actually two 80 page essays, one (on Afghanistan) by Stewart and the other (on the Balkans) by Harvard’s Gerald Knaus. They’re both good, but I will stick to Stewart’s for now.

evaluations. He rocked up at LSE, despite having just been reshuffled to Minister for Prisons, spoke without notes, and blew everyone away. Alas, he insisted on it being off the record, so I cheated – I went back to the 2011 book that provided the material for his talk. It’s actually two 80 page essays, one (on Afghanistan) by Stewart and the other (on the Balkans) by Harvard’s Gerald Knaus. They’re both good, but I will stick to Stewart’s for now.

Stewart’s essay answers the question in the title with a pretty resounding ‘no’. Western intervention is doomed to fail because of its self-defeating combination of ‘isolation, optimism and abstraction’.

Isolation is born of the ‘overwhelming burden on ambassadors and managers to ensure their civilian staff take no personal risks’, with the result that ‘one member of the US embassy told me that she had been in the country for two years without ever leaving the embassy property.’ On the rare occasions when they leave the compound, hardly any Western officials can speak to anyone in their own language: ‘In nine years, I did not meet a senior foreign official in Afghanistan who spoke an Afghan language well.’ Instead of valuing local knowledge.

A Modern Lawrence? Stewart on his Afghan walk

Stewart himself sometimes seems a throwback to former times, an eccentric Lawrence of Arabia figure famous for walking across both Afghanistan and Iraq in the middle of their civil wars. ‘British India was not a rapidly improvised ad hoc collection of internationals, with extravagant budgets, limitless power and very short term postings. It favoured staff with logn experience who served in remote posts, spoke languages well, and reflected on local culture.’ But now, he laments, ‘a culture of country experts had been replaced by a culture of consultants.’

The writing is wonderful. Here is Stewart describing ‘James’, a friend working for a multilateral institution:

‘He had little knowledge of Afghan archaeology, anthropology, geography, history, language, literature or theology. He did not know the Pashto poetry that celebrated the expulsion of foreign armies. He did not take an interest in the honour codes of gangsters of Old Kabul. This was not his individual failing. He could have learned all these things, but he was not given the time to study them and he would not have been rewarded or listened to if he had known them.

Instead he, like most international civilians was an expert in fields that hardly existed as recently as the 1950s: governance, gender, conflict resolution, civil society, and public administration. They were not experts on gender and governance in Afghanistan: they were experts on gender and governance in the abstract. They had studied ‘lessons learned’ by their colleagues in other countries and were aware of international ‘best practice’.’

Ouch.

Stewart believes success in recent interventions is possible only on narrow, technical issues that are safely removed from the grain of local history and politics: ‘they did well at stabilizing the currency but very poorly at establishing honest local policemen; well at designing bridges, poorly at weaning farmers from opium production’.

Success also tends to come in the first few months after an intervention – for example, removing previous Taliban laws that banned all female education, or freeing up the media. From then on, it’s all downhill for the interveners/invaders, as their ignorance of local realities undermines their ability to get anything done.

The Westerners’ optimism is extraordinary and delusional – Stewart pulls together year after year of quotes from  both the military and politicians from Britain, the US and elsewhere, all predicting that yes, there have been mistakes, but now we have ‘got the formula right’ and are on the brink of lasting peace and stability. That ingrained optimism explains the seductive power of the current president, Ashraf Ghani, who while still an academic delivered a formula for state-building based on listing ‘ten functions of the state’, with an accompanying budget. He even turned it into an 18 minute TED talk.

both the military and politicians from Britain, the US and elsewhere, all predicting that yes, there have been mistakes, but now we have ‘got the formula right’ and are on the brink of lasting peace and stability. That ingrained optimism explains the seductive power of the current president, Ashraf Ghani, who while still an academic delivered a formula for state-building based on listing ‘ten functions of the state’, with an accompanying budget. He even turned it into an 18 minute TED talk.

That optimism could be maintained in spite of experience partly because it was couched in terms of ‘indistinct utopias’ of ‘state-building’ and ‘legitimate, accountable governance’ that were impossible to measure – when have you built enough state or governance? When does the Law actually rule? Conveniently, no-one can tell.

Stewart sets out a ‘new approach to intervention, one that could avoid the horror of Iraq or the absurdity of the Afghan surge.’ It sounds pretty much like the standard chorus on ‘working with the grain’, based on officials ‘who have spent a long time getting to know a particularl place. The ideal education is through an ever-more detailed study of the history of a particular place, on the one hand, and of the limitations and manias of the West, on the other.’

But based on what goes before, I rather doubt that Stewart thinks this is possible within the modern system.

April 23, 2018

How do you persuade USAID to adopt Adaptive Management? An insider’s account

Over the next few months, I’m hoping to get my amazing LSE Masters students to contribute the occasional blog – following yesterday’s post on interesting thinking at USAID, here’s a taster from

David Yamron

following yesterday’s post on interesting thinking at USAID, here’s a taster from

David Yamron

What happens when you try and put Adaptive Management into practice in a large aid bureaucracy? I spent two years finding out at the biggest of them all – USAID. For the two years prior to my studies at the LSE I worked as a contractor on a USAID project called Measuring Impact. Measuring Impact (or MI, as it was inevitably christened) is a five-year, $20 million project based within USAID’s Office of Forestry and Biodiversity. The purpose of the project is to institutionalize adaptive management and effective monitoring, evaluation, and learning within USAID projects in our little corner of the Agency.

It’s important at this juncture to briefly elaborate on what we mean when we talk about adaptive management, because I find that many people turn off when they hear buzzwords. But adaptive management is at its core a simple idea. At MI we were trying to get teams to design projects by understanding their context, plotting the outcomes they wanted to achieve, and building a theory of change to get from the former to the latter. From there, during implementation we pushed them to periodically reexamine their theory of change and outcomes, assess their progress, and make changes to their implementation strategy based on new information, all the while documenting their work so that future projects could learn from their experience.

It’s perfectly straightforward….

After I had described this process at a recent panel event at the LSE, my professor (the proprietor of this very blog) said, half joking, that this was revolutionary. And he was right. While these aren’t radical ideas, their operationalization represents a massive change to the way things are done in development, and change is always a threat. This is doubly true in a big bureaucracy like USAID. What MI was trying to do is make people design more effective projects, and to better define outcomes of those projects. Stakeholders can see this as a risky proposition. After all, USAID projects are used to reporting on output targets, like training hours, which are relatively easy to hit. The challenge of MI was to get those same projects to design their indicators, monitoring processes, and reporting processes to answer the question, what did we really achieve with this project? Trained some teachers, OK, but how did that actually affect test scores in your region of Indonesia? How many fishers in this Philippine village are actually using the sustainable fishing practices they’ve been trained in?

There is massive opposition to these sorts of changes. On the USAID side, mission staff often don’t want to make time for passing “fads” like adaptive management. New currents in development thinking can be seen as an imposition because funding cuts mean smaller and smaller cohorts are having to work harder and harder: just another thing that Washington makes me do, just more admin work that I don’t need to do because I already know how to do my job. While understandable, this is dangerous thinking. As we know, adaptive management processes sometimes show that certain interventions actually aren’t effective. That’s a hard pill to swallow for people who have built careers implementing, say, sustainable livelihoods programs. That being said, because of the decentralized nature of USAID, if a given mission’s leadership supports adaptive management, they can act as champions. Duncan calls this “going where the energy is,” and it’s a great way to build support for institutional change. A good example at MI was the South America Regional office in Lima, which had a fantastic and supportive leadership team. With MI assistance, they began designing and implementing adaptively managed projects that could monitor, course correct, and prove outcomes, and (even better!) proved willing and able to talk about it in public.

There is also opposition from the contractors implementing the projects. This is a simple incentives game:

Afghanistan

contractors don’t want to be judged on outcomes, because they’re afraid they won’t hit them. If they adaptively manage their project and progress along their theory of change and then report that they didn’t achieve their outcomes, that harms their prospects of winning future contracts. We found that it was often difficult to convince contractors to practice adaptive management without being forced to by contract language or USAID management.

Winning over these stakeholders was a difficult proposition. But doing so is the MI goal: our own outcome. To achieve that, we built the MI theory of change, a massive diagram that faintly resembled the famous Afghanistan spaghetti-mess system analysis.

USAID

One of the solutions we designed was to get adaptive management processes written into the actual guidebooks and project contracts; essentially doing an end-run around the mission staff and implementation teams. From there, we could leverage relationships with champions like South America Regional to teach teams how to design and implement projects according to the new rules and contract language. This relieved us of the task of fighting incentives and appealing to people’s better angels, and allowed us to present ourselves to project teams as people with solutions rather than more problems. One major success of MI was adding a section requiring a theory of change to the ADS Programming Policy series (official USAID guidance on program design and implementation). Another was drafting procurement language mandating adaptive management practices like theory of change workshops, outcome-based reporting, and pause-and-reflect sessions throughout implementation.

During the aforementioned panel event a student asked me, “How do you get people to do good M&E?” It’s a fair question. And I think the answer, more or less, is to approach it like a good adaptive manager. In MI’s case, that meant mapping out the context, identifying the important stakeholders, convincing them, and then using the persuasive power of our mission champions and the coercive power of bureaucratic sanctions to institutionalize the program. And while that is still a distant goal, I think that the process of institutionalization of adaptive management at USAID (or at least our little corner of it) is well on its way.

David Yamron is a former Adaptive Management Specialist for USAID Measuring Impact and a current Master’s candidate in Development Management at the London School of Economics. Check out his new development podcast The World Isn’t Flat, hosted with three other LSE grad students.

April 22, 2018

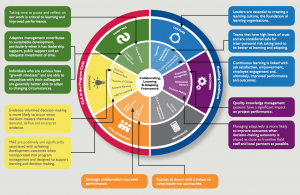

Smart thinking from USAID on putting adaptive management into practice

I recommend USAID’s recent paper ‘What difference does CLA (Collaborate; Learn; Adapt) make to development: Key findings from a recent literature review’, which provides further evidence that USAID for all its problems with the Administration, continues to do some really interesting work. The 12 key findings are neatly summarized in this graphic:

The paper’s only 5 pages, but for those that can’t even manage that, I’ll pick on the four findings that struck me as the most interesting;

Finding: Individuals who are curious, have “growth mindsets,” and are able to empathize with their colleagues are generally better able to adapt to changing circumstances. Ultimately, it is individuals who take on the work of collaborating, learning and adapting within organizations and across partner organizations. Individual personality traits, habits and competencies can affect who is more likely to take on these behaviors. The literature reviewed found the ability to be flexible and adaptive is highly related to individual personalities, which in turn drive office culture and institutional appetite for change. Across sectors, the literature found that hiring those with “adaptive mindsets” (inquisitive by nature, able to ask the right questions, flexible skillsets) and those that show sensitivity to the feelings and needs of their colleagues had a direct impact on a team’s ability to learn and adapt to effect change.

Implication for USAID Staff: In hiring for key positions, place value on adaptive mindset, soft skills and change management experience. Habits and competencies that make an individual more likely to learn and adapt need to be considered and intentionally nurtured through coaching and training in order to incentivize behavior change. As with any change effort, intentionally seeking out CLA champions with a high propensity to promote and model learning behavior will be critical for CLA uptake. If these behaviors are desirable, then clear signals need to be given to indicate that (praise in meetings for changes based on new information, leadership encouragement of trying new things, etc.)

Finding: Leaders are essential to creating a learning culture, the foundation of learning organizations. The literature discusses how organizations that encourage honest discourse and debate and provide an open and safe space for communication tend to perform better and be more innovative. Leaders are central to defining culture and “learning leaders” are generally those who encourage non-hierarchical organizations where ideas can flow freely.

Implication for USAID Staff: Mission and implementing partner leadership must model strategic collaboration, continuous learning and adaptive management. As we know from experience and confirmed by the literature, leaders are essential in creating an “enabling environment that encourages the design of more flexible programs, promotes intentional learning, minimizes the obstacles to modifying programs and creates incentives for learning and managing adaptively” (ADS 201 guidance, page 11). But achieving this enabling environment begins with leaders who truly lead by example and create the space for staff to collaborate, learn and adapt more effectively. Leadership training and coaching can help leaders at all levels within the organization improve their skills and create a culture that supports CLA.

Finding: Continuous learning is linked with job satisfaction, empowerment, employee engagement and, ultimately, improved performance and outcomes. A growing body of evidence from both private and public sector organizations recognizes that having a strong organizational learning culture increases psychological empowerment and sense of autonomy, which drives a collaborative team culture, high levels of commitment and employee retention. In the USAID context specifically, CLA is strongly related to staff empowerment, engagement and job satisfaction.

Implication for USAID Staff: Leaders should model CLA. In addition to missions using CLA approaches to improve strategy, project, and activity design and implementation, CLA can also be seen as a leadership tool for creating more effective organizations where employees are more satisfied, engaged and empowered. We are already seeing CLA being used to improve staff engagement in USAID missions, including Uganda and Senegal, as well as in the Office of Afghanistan and Pakistan Affairs.

Finding: Teams that have high levels of trust and are considered safe for interpersonal risk-taking tend to be better at learning and adapting. Managing adaptively requires a level of group tolerance for risk-taking, which by extension is contingent on teams having trusting relationships. The literature reviewed found that high trusting teams generally tend to be high-performing. Why are high trusting teams higher performing? Because they also tend to have high levels of “psychological safety,” which is the shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking. This means they are more likely to participate in risk-taking learning behavior, and by extension proactive learning-oriented action, which positively impacts results.

Implication for USAID Staff: Create space and time for team members to develop trusting interpersonal relationships. Activities that build mutual understanding and shared trust—such as group reflection moments, team problem-solving and equal conversational turn-taking—aid collaboration and evidence-based decision-making and should be prioritized. Informal opportunities for information sharing and practicing social sensitivity are also important for building team trust and psychological safety. This is especially important in the context of partnerships with local actors

April 8, 2018

Links I Liked

It’s going to be a long day at Prague airport…. ht Misha Glenny

Really amazing legal activism in Colombia, on intergenerational equity and environmental destruction. And the good guys won. ht Tessa Khan

What to say when someone tries to mansplain away the gender pay gap

Brilliant David Booth (ODI) piece on doing problem-driven development: four lessons from Nepal

“Following the storms, a coalition of environmental NGOs brings a class-action suit against the US government and fossil-fuel companies on the grounds of neglecting what scientists (including their own) have been saying for years: that something must be done. A social reaction to the use of fossil fuels grows, and individuals become ‘vigilante environmentalists’ in the same way, a generation earlier, they had become fiercely anti-tobacco. Direct-action campaigns against companies escalate. Young consumers, especially,  demand action …” From a 1998 Shell scenario planning exercise. Anyone else see a comparison to Big Tobacco and litigation?

demand action …” From a 1998 Shell scenario planning exercise. Anyone else see a comparison to Big Tobacco and litigation?

The Daily Excess Express surpassed itself with its ‘one year to Brexit’ cover. a) ooh, look – a cliff edge b) the photographer says they artificially whitened up the cliffs. Oops.

The Debate about RCTs in Development is over. We won. Slides and transcript of Lant Pritchett’s provocative/triumphalist recent lecture

The Donald channels Donnie Darko at Easter. Extremely odd, even by modern White House standards. Is BunnyBragging a thing now?

And on that surreal note, I am off on holiday. Back on 23rd April. Here’s a happy sloth to keep you company while I’m gone (really hope I get to see one, as well as be one)

April 6, 2018

Adaptive Management in Myanmar – draft paper on Pyoe Pin for your comments

Ok, FP2P hivemind, I want your comments on a draft paper about an iconic Adaptive Management programme,  Pyoe Pin in Myanmar. My co-author is Angela Christie. The paper is for the Action for Empowerment and Accountability Research Programme. Here’s the exec sum, and you can download the whole 20-page paper here.

Pyoe Pin in Myanmar. My co-author is Angela Christie. The paper is for the Action for Empowerment and Accountability Research Programme. Here’s the exec sum, and you can download the whole 20-page paper here.

This paper examines adaptive techniques in aid programming in a fragile, conflict and violence-affected setting, namely Myanmar. A combination of desk review and field research has been used to examine some of the assertions around the adaptive programming approach and to explore if and how adaptive techniques, including rapid learning and planning responses (fast feedback loops and agile programming) are particularly relevant and useful for promoting empowerment and accountability in such ‘messy places’.

‘Pyoe Pin is ready to take a risk, they move fast. Other donors are much more rigid in their country strategies.’ Civil Society Leader

This case study focuses on Pyoe Pin (‘Young Shoots’), a DFID-funded governance programme, which has been running since 2007. During ten years of extraordinary political and social turbulence, the Pyoe Pin (PP) team and its partners have facilitated social and political change by bringing together coalitions of groups and individuals to address particular issues of social, political, economic or environmental concern. To achieve this, PP supports a flexible number of issue-based programmes (IBPs) currently covering education, health, fisheries, forestry and extractive industries

Our field research focused in particular on the fisheries IBP, which is considered by Pyoe Pin to be ‘one of the first examples of public participation in state-level policy making in Myanmar’. A field visit to talk with officials, local NGOs, politicians and fishing communities added considerable insight and texture to our understanding of how PP works. Our meetings revealed an organization deeply embedded in relationships of trust with ministers, parliamentarians, civil society organizations and fishing communities, and using those trust relationships to facilitate significant progress in fisheries reform, which in turn is leading to widespread improvements in the lives of small-scale fishers.

Our field research focused in particular on the fisheries IBP, which is considered by Pyoe Pin to be ‘one of the first examples of public participation in state-level policy making in Myanmar’. A field visit to talk with officials, local NGOs, politicians and fishing communities added considerable insight and texture to our understanding of how PP works. Our meetings revealed an organization deeply embedded in relationships of trust with ministers, parliamentarians, civil society organizations and fishing communities, and using those trust relationships to facilitate significant progress in fisheries reform, which in turn is leading to widespread improvements in the lives of small-scale fishers.

Findings

Our overall conclusion is that the kinds of adaptive approaches pursued by Pyoe Pin can work in fragile, conflict and violence-affected settings, and indeed may be particularly well suited to the volatile, fragmented and unpredictable nature of such places. However, for such approaches to succeed, they need to be applied by individuals with a deep and nuanced understanding of the local context and an instinct for flexible and adaptive decision making. Further, for such individuals to prosper, they need freedom to act on a daily basis while also being supported by longer term cycles of learning and planning. Achieving the right levels of decision making devolution is not easy and means that authorising teams must sometimes be prepared to swim against the tide of institutions, ideas and interests that shape the aid sector. Thinking about what this means in practice leads us to two main conclusions – and possible next steps for this research:

The first and perhaps most important conclusion from this research is that there is a need to distinguish more clearly between adaptive management (‘everyday PEA’) and adaptive programming (a longer-term process), and ensure that the two are both present and mutually supportive.

between adaptive management (‘everyday PEA’) and adaptive programming (a longer-term process), and ensure that the two are both present and mutually supportive.

Much more attention (and perhaps more research) is needed on how to recruit, incentivise and retain entrepreneurial spirits of the ‘adaptive delivery’ kind we saw in Pyoe Pin – such individuals are born networkers, with a deep instinct for power analysis and grasp of the shifting landscape of opportunities and threats, and the patience and stamina required to get results. We are sceptical that staff steeped in linear thinking and compliance mentalities can be transformed into risk-taking, politically savvy entrepreneurs through a few workshops or a tweak in incentives. Determining who has these skills is an important task for those who would build a team capable of adaptive delivery.

There are some potential shortcomings of Adaptive Delivery that need attention, Pyoe Pin’s focus on ‘getting the right people in the room’ means identifying the powerful players within a previously excluded group, and that risks overlooking marginalised people within such groups – we barely spoke to any women during our visit to the fisheries programme. There is a danger that the win-win perspective involves working with the grain to such an extent that entrenched and excluding norms of behaviour cannot be challenged. Political economy analysis begins at home. PP appears to find it easier to focus some IBPs on specific issues of marginalisation, rather than to mainstream inclusion across all IBPs. For example, on HIV, PP has set up networks for highly marginalised groups –the Sex Worker in Myanmar network – to good effect.

Adaptive approaches also need to guard against the risk of sclerosis, as investments (led by adaptive managers) in acquiring knowledge, experience and relationships can generate their own inertia and unwillingness to pivot towards new opportunities. Thus, there is a place also for adaptive programmers who can introduce mechanisms to guard against thickening arteries, such as regularly thinking about diminishing returns and local ownership and spinning off new initiatives that enjoy the agility and innovation of start-ups.

Research question: in what ways can adaptive delivery and adaptive programming work better together?

Our second main conclusion is that the aid industry – the constellation of donors, consultants, implementing organizations, NGOs etc – struggles with the requirements of adaptive approaches.

At a crude level, there is little compatibility between adaptive approaches and the pressure for predictability, for risk minimisation and for results (often in the short term) that dominate donor agendas, especially in FCVAS. Even if donors initially ‘get it’, as was the case with DFID’s pioneering work in setting up Pyoe Pin, their own internal volatility (of personnel and priorities) makes it hard for them to maintain the commitment over the timescale necessary to achieve real change in FCVAS. That may be an argument for seeking ways to minimise the impact of donor volatility, for example by using a new funding, monitoring or reporting mechanism to provide adaptive approaches with a bulwark against the shifting tides of the aid business.

At a crude level, there is little compatibility between adaptive approaches and the pressure for predictability, for risk minimisation and for results (often in the short term) that dominate donor agendas, especially in FCVAS. Even if donors initially ‘get it’, as was the case with DFID’s pioneering work in setting up Pyoe Pin, their own internal volatility (of personnel and priorities) makes it hard for them to maintain the commitment over the timescale necessary to achieve real change in FCVAS. That may be an argument for seeking ways to minimise the impact of donor volatility, for example by using a new funding, monitoring or reporting mechanism to provide adaptive approaches with a bulwark against the shifting tides of the aid business.

In this case, these challenges have not been helped by the fact that Pyoe Pin has struggled to find ways to describe its work that satisfy donors. The subtleties of adaptive delivery – operating below the radar; spotting and reacting to the frown on the face of the minister and the often unpredictable results that this generates – can easily be overlooked or brushed aside in the search for cruder metrics to feed the results/value for money machine linked to achievements predicted within results frameworks.

This is doubly unfortunate because based on this visit, Pyoe Pin has a strong case to make that adaptive approaches can produce impressive results, even within the current institutional constraints. Were it to make this case well, donors would then face a strategic decision over whether to accept higher levels of risk and uncertainty in order to achieve greater results.

Research question: what shifts in the way aid is financed, monitored and reported would make the most meaningful contribution to enabling adaptive delivery and programming, without losing the requirements of accountability?

April 5, 2018

Africa’s First Panther Economy? Wakanda’s development dilemmas

Guest post by Dulce Pedroso (Manager, Health) and Taylor Brown (Director, Governance), Palladium

Wakanda is in transition. This small, but prosperous East African nation has never been colonised. It has never received foreign aid, technical assistance, loans or outside advice. Yet Wakanda has thrived in its seclusion. It has managed its vast resource wealth wisely. Its isolationist foreign and autarkic economic policies have delivered prosperity, exceedingly high levels of social and human development and cutting edge technological innovation.

But now, Wakanda is opening up to the world. As it does so, it faces significant development dilemmas — both as a potential donor and as a member of the global economic and political community.

For those of you who live off the grid, Wakanda is the fictional country at the heart of Black Panther, Marvel’s Afro-futurist blockbuster. As the first Hollywood blockbuster about Africa that is not primarily about slavery, genocide, war, poverty, the movie has inspired numerous articles and blogs exploring race and representation. But Black Panther also asks big questions about development. Why and how should prosperous, technologically advanced countries assist poorer, less developed ones? How can such a resource rich country integrate with the global economy without distorting its traditions, or its own political economy?

Why give aid?

Black Panther illustrates different rationales for development assistance, through the eyes of its central characters.

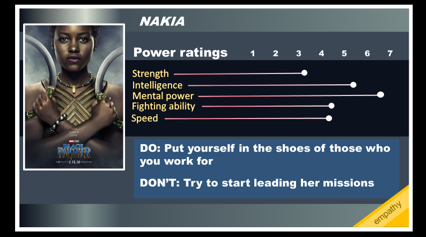

Nakia, who balances a career as a spy and an aid worker, is one of the few Wakandans who regularly engage with the outside world. Frustrated with Wakanda’s historic isolationism she believes that her country has a fundamental obligation to contribute to the world and address poverty and injustice in all its guises. She believes that Wakanda should use its wealth and technology to improve not only the lives of those in neighbouring countries, but also those marginalised communities elsewhere in the world. Nakia has a strong notion of distributive justice rooted in empathy for those who are not lucky enough to be born in Wakanda.

Nakia, who balances a career as a spy and an aid worker, is one of the few Wakandans who regularly engage with the outside world. Frustrated with Wakanda’s historic isolationism she believes that her country has a fundamental obligation to contribute to the world and address poverty and injustice in all its guises. She believes that Wakanda should use its wealth and technology to improve not only the lives of those in neighbouring countries, but also those marginalised communities elsewhere in the world. Nakia has a strong notion of distributive justice rooted in empathy for those who are not lucky enough to be born in Wakanda.

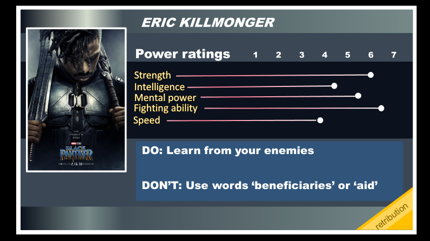

Scarred by the death of his father and driven by revenge, the film’s complex anti-villain Eric Killmonger has a very different notion of distributive justice. He has much more in common with the real-world Black Panthers than the movie’s name sake. For him, Wakanda has failed its brothers and sisters in Africa and in the African diaspora: “Two billion people all over the world who look like us whose lives are much harder, and Wakanda has the tools to liberate them all,” he chides the Wakandan court, “where was Wakanda?” This thinking – where there can be no justice without righting the wrongs of the past – has its roots in post-colonial frameworks of retribution and reparations. Eric would hate the word ‘beneficiary’ even more than Pete Vowles and without “a scintilla of gratitude”, he would

different notion of distributive justice. He has much more in common with the real-world Black Panthers than the movie’s name sake. For him, Wakanda has failed its brothers and sisters in Africa and in the African diaspora: “Two billion people all over the world who look like us whose lives are much harder, and Wakanda has the tools to liberate them all,” he chides the Wakandan court, “where was Wakanda?” This thinking – where there can be no justice without righting the wrongs of the past – has its roots in post-colonial frameworks of retribution and reparations. Eric would hate the word ‘beneficiary’ even more than Pete Vowles and without “a scintilla of gratitude”, he would  inspire Daily Mail columnists for years to come.

inspire Daily Mail columnists for years to come.

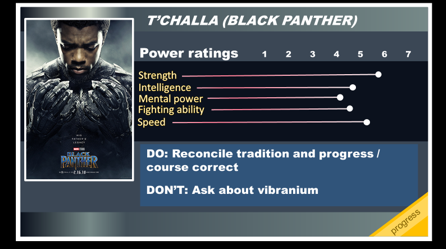

Under the funky body-contouring cat suit, T’Challa, or Black Panther, is an isolationist mostly concerned with following the customs that have enabled Wakanda to thrive. At first he listens to his friend W’Kabi’s, warnings of the problems that come with refugees and immigrants, but over time is influenced by Nakia and Eric. It takes him until a mid-credits scene, but in the end he decides that the time has come for Wakanda to open up to the world: “Now, more than ever, the illusions of division threaten our very existence. We all know the truth: more connects us than separates us. But in times of crisis the wise build bridges, while the foolish build barriers. We must find a way to look after one another as if we were one single tribe.” With this speech to the UN, T’Challa is upending the deeply embedded narrative that international development is fundamentally about the “global north” developing the “global south”…even if the assembled diplomats are still nodding along with the unnamed delegate who condescendingly asks what resources Wakanda could possibly offer to the rest of the world.

T’Challa’s challenge

Wakanda enters the world stage at a time when aid scepticism and isolationism have made their way from the fringes to mainstream politics.

The country now faces two crucial dilemmas: First, how can Wakanda best share its expertise and technology with the world – what should its development policies, programmes and priorities be? Secondly, how can Wakanda avoid the pitfalls other resource rich states have faced as it integrates into the global economy?

Wakanda’s first foray into development, a community outreach centre in Oakland, is more symbolic than substantive. It is also conventional — providing technical assistance and technology transfers in the hope that  economic, social and human development will somehow follow. In doing so, Wakanda appears to be making the same assumptions that many tech entrepreneurs do when they turn their gaze and resources to philanthropy: that techy approaches alone can solve the world’s big problems including poverty. Still it’s a start. But it does seem that Wakanda’s first Development Minister (Nakia?) might need some strategic advice on how Wakanda’s expertise and resources can contribute to the SDGs.

economic, social and human development will somehow follow. In doing so, Wakanda appears to be making the same assumptions that many tech entrepreneurs do when they turn their gaze and resources to philanthropy: that techy approaches alone can solve the world’s big problems including poverty. Still it’s a start. But it does seem that Wakanda’s first Development Minister (Nakia?) might need some strategic advice on how Wakanda’s expertise and resources can contribute to the SDGs.

Wakanda may be the world’s most technically advanced country and have a corner on the vibranium market, but T’Chala still faces significant challenges and policy choices as he integrates his country into the global economy: What fiscal and domestic policies might help Wakanda avoid the resource curse and Dutch Disease as it begins to export its resources? What strategies might it employ to diversify its economy against the day when the vibranium runs out? Should Wakanda allow FDI into the vibranium sector and if so, what regulations would need to be in place? How might it manage the potential influx of prospectors and other migrants attracted to the jobs and opportunities found in Wakanda?

no basis for a system of government…..

Lastly, there are big questions about accountability. As Wakandan opens up to the world, will traditional combat on the edge of a waterfall (with shades of Monty Python’s “farcical aquatic ceremony”) continue to provide the only means through which civilians can hold their leader to account?

So…what advice would you give to Wakanda? As a development superhero, we are sure you will accept this challenge and share your ideas and recommendations by leaving a comment below…….

April 4, 2018

Partnering Under the Influence: How to Fix the Global Fund’s Brewing Scandal with Heineken

This guest post is from Robert Marten (left, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) and Ben Hawkins (LSHTM and University of York)

This guest post is from Robert Marten (left, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) and Ben Hawkins (LSHTM and University of York)

The new head of the Global Fund to Fight HIV, Tuberculosis and Malaria, Peter Sands recently argued that “the global health community needs to engage with the private sector more rather than less.” Yet even most advocates of public-private partnership will not engage with certain companies, for instance those in the tobacco or arms industries. These sectors are correctly regarded as pernicious. Not only do they sell deadly products, but they are also untrustworthy partners supporting the production of fraudulent “evidence” in their efforts to evade and lobby against national and global regulation.

Although it is often regarded differently to the tobacco industry, the alcohol industry functions in much the same way. The industry’s products kill more than 3.3 million people every year, and trans-national alcohol companies have been proven to manipulate evidence about their products’ harmful effects. Seen in this context, it appears highly questionable that the global health community would engage with or partner with the alcohol industry. And yet this is precisely what the Global Fund has decided to do.

In January the Fund announced a partnership with Heineken, the world’s second-largest brewer. The response from civil society was immediate. IOGT International, the Global Alcohol Policy Alliance and the NCD Alliance with endorsements from more than 100 organizations, wrote “to respectfully urge an immediate end to this partnership.” We argued in the Lancet in February: “The partnership with Heineken is antithetical to the Fund’s core interests. By cooperating with, supporting, and legitimizing the alcohol industry, the Fund is endangering its own credibility and risks losing public trust.”

In January the Fund announced a partnership with Heineken, the world’s second-largest brewer. The response from civil society was immediate. IOGT International, the Global Alcohol Policy Alliance and the NCD Alliance with endorsements from more than 100 organizations, wrote “to respectfully urge an immediate end to this partnership.” We argued in the Lancet in February: “The partnership with Heineken is antithetical to the Fund’s core interests. By cooperating with, supporting, and legitimizing the alcohol industry, the Fund is endangering its own credibility and risks losing public trust.”

The Global Fund has yet to respond formally; however, Sands recently seemed to double down on its position arguing that if “we really want to achieve the SDGs [Sustainable Development Goals] and build more resilient health systems, we need to partner with the private sector to leverage their resources and their capabilities to innovate.” This is corporate spin and it is disingenuous. Sands’ response conflates the critique of partnering with Heineken with partnering with the private sector writ large. As public relations consultants will attest, generalizing criticisms beyond their specific target is a key strategy for deflecting attention and muddying the waters of debate and forging alliances with other actors whose interests may be touched up by this more general framing; in this instance, this is corporations in other sectors with whom the Fund engages in legitimate partnerships. Our critique is not about the Fund partnering with the private sector, it is about the clear inappropriateness of its engagement with Heineken, or any other alcohol producer.

Of course, the Fund should consider partnering with the private sector when it is appropriate and helps the Fund  achieve its mandate. However, the Fund also needs to scrutinize potential partnerships far more closely than appears to be the case, ensuring that they are aligned with its mandate and the SDGs. In this instance, it seems like the partnership is designed to take advantage of Heineken’s distribution network, enabling the Fund to deliver supplies to hard-to-reach areas. But Heineken isn’t the only company which operates in hard-to-reach areas, and if the Fund wants to improve its supply chain, there is a wide range of legitimate potential partners beyond Heineken and the alcohol industry. Moreover, the Global Fund has failed to argue or explain how these potential logistics gains might outweigh the well-established costs of working with and legitimizing the alcohol industry. Worse, the Fund is overlooking alcohol’s widely-understood effects on HIV and TB – the very diseases the Fund aims to cure.

achieve its mandate. However, the Fund also needs to scrutinize potential partnerships far more closely than appears to be the case, ensuring that they are aligned with its mandate and the SDGs. In this instance, it seems like the partnership is designed to take advantage of Heineken’s distribution network, enabling the Fund to deliver supplies to hard-to-reach areas. But Heineken isn’t the only company which operates in hard-to-reach areas, and if the Fund wants to improve its supply chain, there is a wide range of legitimate potential partners beyond Heineken and the alcohol industry. Moreover, the Global Fund has failed to argue or explain how these potential logistics gains might outweigh the well-established costs of working with and legitimizing the alcohol industry. Worse, the Fund is overlooking alcohol’s widely-understood effects on HIV and TB – the very diseases the Fund aims to cure.

The partnership with Heineken also contradicts the spirit of the SDGs. Regulating alcohol is ingrained in the SDGs; the SDGs call for strengthening regulatory responses to alcohol. The idea of a Heineken logistics team delivering Global Fund supplies to a health clinic while also delivering beer is absurd – and painfully, even fatally, incompatible with the SDG3 aim to ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages.

Based on “recent reports of the company’s use of female beer promoters in ways that expose them to sexual exploitation and health risks” the Global Fund announced on March 29 that it was suspending its partnership with Heineken “until such time as Heineken can take appropriate action to address these issues.” But as others have explained, this is not enough. So what should the Fund do about its partnership with Heineken?

The number of injury deaths attributed to alcohol per 100,000 people in 2010. (does not include chronic disease such as cancer or liver cirrhosis)

First, the Fund should announce an immediate and open review of its partnerships, solicit public feedback and declare its intention to develop a new partnership policy in line with the SDGs. The Fund should terminate its inappropriate partnership with the alcohol industry.

Second, the Fund should disclose the records of its interactions with Heineken (and any other alcohol industry actors) so researchers can document this episode and investigate the industry’s tactics and intentions. In the absence of a new partnership policy, the Global Fund’s donors and partners will need to reconsider the Fund’s commitment to global health and the SDGs before the Fund’s next replenishment. Without a new partnership policy, the Fund’s donors and partners will need to turn off the Global Fund’s financing tap.

April 3, 2018

An experiment in participatory blogging on Ebola in Sierra Leone

Anthropologists do things differently, including blogging. My attention was piqued by Tim Allen’s reply to a

Home made protective clothing from Ebola burials

commenter on his recent post (with Melissa Parker) on Ebola in Sierra Leone, in which he casually mentioned ‘It is perhaps worth adding that the chief and elders wanted us to write it, and we read it out at a meeting of the whole village before posting it.’ Woah, is community blogging now a Thing? So I interviewed Tim, Melissa and the three Sierra Leonean researchers they were working with: Tommy Hanson, Lawrence Babawo and Ahmed Vandi, all of Njala University. The story turned out to be even more interesting than the original comment suggested.

Melissa: ‘I was sitting in the kitchen area of a hut interviewing a woman who had lost her husband to Ebola at a Treatment Unit. He had been taken there shortly after the military arrived in the village.

But I never got to hear any more, because four men strode up and in a hostile way started saying ‘you keep coming back, what is the point of your work, if it’s not doing us any good?’

Tommy: ‘They were very furious. They had research fatigue, ‘you come in the morning and put us together for a couple of hours when we have to go to our farms, and you don’t even leave money for food.’

Melissa: ‘I’ve never encountered such an aggressive response before. I tried to explain that we weren’t an NGO, had never promised to give them things, but hoped that the information emerging from our interviews would publicise their opinions and needs. But they weren’t convinced. I wasn’t scared, but I was concerned and thrown – it was very unpleasant. Then Tim arrived, and suggested a blog.

Tim: ‘I’ve been thinking about this for a while. We want to use blogs as a way for African researchers to have a voice, perhaps as a pathway to producing papers. So I had that in mind when Melissa was having trouble, and it seemed like the obvious thing to suggest as a means of responding to these men’s frustrations about not being listened to.

We said we would draft it and come back the next day. They said yes and we left the village with a slightly sour feeling. We wrote the blog that evening, went back the next day, and no-one was there. Just a few children at school and an old blind guy. ‘They’ve all gone to dig in the Imam’s field. it’s a long way away’. We said: ‘We’ll go there, where is it?’ They found a young lad to take us and off we went into the forest – it was quite an adventure. We walked for about an hour, down winding paths. Then got to a swamp and had to wade up to our thighs across a river – we

Tommy Hanson photographing Tim Allen (the one with white legs) digging in the Imam’s field

came out into a hidden area surrounded by thick vegetation and huge trees. It turned out this was the place where they had secretly treated some of the sick during Ebola. The men were digging the field, so we spent the morning talking and digging with them – they were rather amazed and found us digging very funny. The guys who had been hostile became much more friendly.

While there, we interviewed the old chief; he was very revealing about what had gone on during the Ebola epidemic, told us how his father had died of Ebola, and he had been summoned by the next chief up because they’d heard about the secret burials. He didn’t tell them about his father’s burial, but he was found out and sacked. His replacement was found murdered – no-one knows if it was people in the village, thugs – there were lots of rumours.

We spent the morning in the field digging and talking, then stayed for lunch, and came back to the village with them, as their guests. Everyone cleaned themselves up and we called the meeting – everyone was there.

Then we read out the blog from the laptop; Tommy was translating line by line. In terms of their suggested changes

Mathiane Village Elders

to our draft, there were few. Some wanted to discuss the theft of a blackboard from the school. Overall, they were hugely enthusiastic, and some wanted their names and photos included. We were reluctant to do that in case there were repercussions for them, and explained that to them. When I read out ‘Everybody made promises and didn’t come back. We care for each other and now we are being punished; where are the NGOs now?’’ – everyone stood up and clapped and cheered!

Then we had a really nice event – I did some magic tricks and we had running races for the children, then hopping, then the whole village joined in. All sorts of competitions. It ended up with me having a race with the primary school teacher. It was a dead heat. We were all mobbed by the kids at the end!’

Tommy: ‘Now they often call to ask when we are coming back!’

Love it.

P.S. from Tim and Melissa:

Reflecting on the post we wondered about authorship. We wrote it, but should we have had ‘the people of Mathiane’ as co-authors? Also, what about Tommy and our other Sierra Leonean colleagues? We are keen that they author blogs themselves, but we thought it best in this instance to just put our names as authors to protect people who might be criticised for publicising these issues. But were we perhaps being over-cautious? People in the village said that they wanted to be named. Should we have done so? In the end, we only named the primary school teacher and the newly elected section chief. Was that the right thing to do? This was a quintessentially co-produced piece of work; and we need to find ways of acknowledging this, not only in this instance, but also in future.

April 2, 2018

Positive Deviance in action: the search for schools that defy the odds in Kenya

I’ve been thinking about why there is so little attention to Positive Deviance in development

I’ve been thinking about why there is so little attention to Positive Deviance in development  practice, so got very excited by this experiment in East Africa. Guest post from Sheila P Wamahiu (left), of Jaslika Consulting, and Kees de Graaf and Rosaline Muraya (right), of Twaweza

practice, so got very excited by this experiment in East Africa. Guest post from Sheila P Wamahiu (left), of Jaslika Consulting, and Kees de Graaf and Rosaline Muraya (right), of Twaweza

After two hours of trampolining down dirt roads, getting lost more than once (thanks, Google Maps), we pulled up at the gate of Mwarubaini Primary School. Just a gate – no wall or fence. Tired buildings and potholed classrooms greeted our arrival, but there really was something different in the air. And the story was similar at all the schools we visited, spread across Kenya: this tired look yet vibrant atmosphere.

spread across Kenya: this tired look yet vibrant atmosphere.

This journey began where all good journeys do – behind a desk! Combing through years of data points, examination results, to find schools that seem to defy their circumstances and perform exceptionally well, contrary to expectation. We only considered publicly funded, co-educational day schools and we picked those that had high exam results over time in counties and sub-counties with especially poor performance. And then a deep dive into each of these schools: is their exceptional performance driven by some advantage, not captured ‘in the books’? Or are they truly making the best of the same resources that other public schools are given and using whatever they have to drive learning?

Kitchen at a high performing school

The qualitative research in and around the first list of schools had to be wide and deep: we needed to investigate as many of the schools as we could where our data showed they were doing well, but then efficiently weed out those that had some extenuating circumstances, for example wealthy parents contributing a lot to school expenses. We conducted rapid field visits to 14 out of 26 shortlisted schools. The visits took place over six months in five counties, one and a half days per school. These visits led us to the final list of six which we then investigated in greater depth, to try to really get under the skin of what they did differently.

In both the rapid field visits and the in-depth inquiry, using mixed methods, we talked to lots of people, going beyond local education officials, head teachers and teachers to the wider community: the boda boda (motorbike taxi) driver, the mama mboga (female vegetable seller), people standing by the matatu (local bus) stop, and the taxi driver driving us to our destination. We also talked to children, both girls and boys, through focus groups, using a drawing activity to break the ice and get their views of their school, teachers and learning and disciplinary practices. We added parents and school board members to the mix in the in-depth phase of the study.

In some ways it was fitting that our search took us to some of the more dilapidated schools in Kenya. At least we could push against the common myth that shiny classrooms filled with desks, brand new buildings and a closet full of school supplies are what make learning happen.

In the end, we found six schools that truly deviated positively from the norm. Each one had its own unique story but also some common threads. Leadership in all the schools were willing to try things out, adapt processes and systems; they used whatever little resources they had in creative ways but to great effect; and they put the well-being and learning of their pupils front and centre. Across the board, we found school leaders who are optimists, able to infuse the school community with their enthusiasm so they can pull together to make things happen and to implement government policies in a way that works for them – sometimes rolling out policies that others were afraid to try and sometimes bending the rules and not complying. For example, in some schools classrooms converted to night “camps” for girls in upper primary, watched over by mothers who volunteered as matrons. Although not compliant with quality standards, these kept girls safe from sexual predators, prevented early pregnancy, and allowed extended learning hours in the evenings.

But the schools’ success was not driven by force of personality alone: although the school leaders truly were

Children at Lunch break

visionaries they had all tried to institutionalise their approaches. All of them were active and powerful mentors, and they instilled ownership of the schools into local communities – so much so that the communities themselves would pressure new incoming school leadership to maintain the high standards they were used to.

Other common threads were respect and empathy; head teachers and teachers in these schools demonstrated respect for the children, the community and education. They did not immediately default to punishment: children were not sent home for incorrect uniform or for not having paid the various surcharges. Amboseli Primary School established a “bank” where outgoing pupils would donate their old uniforms and books for those who could not afford to buy their own. Some parents, and sometimes teachers in Chama Primary paid for low income children’s meals. Sometimes, the schools just turned a blind eye to the non-payment. It is a far cry from the norm: being sent home when your parents have not paid, keeping performance high by expelling or holding back weaker pupils and demanding compulsory financial contributions from parents.

These schools did not cancel sports or break time for more academic study: children were actively engaged in games and play as an important part of a balanced learning experience.

All of the schools, and their leadership, recognised that they could look for help in unusual places. They made strong use of peer-to-peer learning and had different strategies around stand-ins and group work to deal with large classes and staff shortages. Firoza Primary School has even trained child tutors to stand in for teachers when they were absent from class for any reason.

So now that we have a long list of ideas, practices and characteristics that seem to create unusual success stories, we can begin the final stage of our positive deviance quest. We will go back to the six schools to share the findings, inviting nearby schools as well. Will school leaders in these exceptional schools recognise, validate and claim ownership of the practices we have identified? Will the schools nearby be able to adopt some of these practices? The ultimate Twaweza question: can we take it to scale?!

Fascinating. Hope the authors can come back and tell us where this work ends up!

March 28, 2018

What does the public think about inequality, its causes and policy responses?

Irene Bucelli

, (left) of the LSE and

Franziska Mager

, of Oxfam GB, summarize the results from

Irene Bucelli

, (left) of the LSE and

Franziska Mager

, of Oxfam GB, summarize the results from an Oxfam volunteer research project

an Oxfam volunteer research project

When it comes to inequality, a growing body of evidence shows that people across countries underestimate the size of the gap between the rich and poor, including their wages. This can undermine support for policies to tackle inequality and even lead to apathy that consolidates the gap.

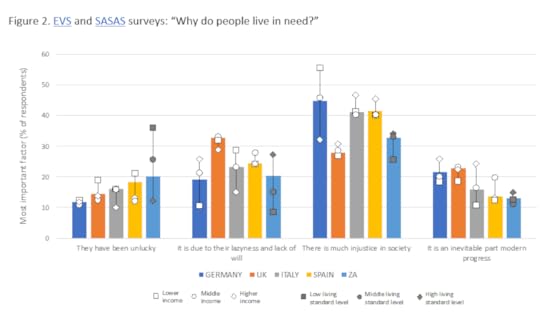

But how exactly are existing perceptions of inequality measured by social scientists? From a range of established, long-running international opinion and attitude surveys, we harvested the most-used questions asking people how they perceive inequality. Three key themes emerge throughout: tolerance of existing levels of inequality, attitudes towards policies to reduce inequality, and beliefs about its causes (table 1).

These themes, with the specific survey questions used to probe them, leave us with a goldmine of openly accessible data from a range of countries (table 2). As a first step we checked the data for seven countries where Oxfam works (UK, Germany, Italy, Spain, Mexico, US, South Africa).

Concern does not lead to support for government action

The surveys reflect high levels of concern about inequality across all countries. But this concern is not always linked to correspondingly high support for governments to tackle the gap (Figure 1). This finding is increasingly established in the inequality literature, and is consistent with recent research conducted by Oxfam and the Australian National University.

Of course, specific subgroups can be driving such differences. Perhaps unsurprisingly, better-off groups generally report lower levels of concern with existing inequality and the lowest levels of support for tackling them. The data suggests that these differences are more marked in some countries (e.g. Germany, US) and less in others (Spain).

Figure 1. ISSP, Mean agreement to “Differences in income in [country] are too large” and “The government should reduce income differences”.

In what ways do people believe the gap between the rich and poor should be tackled, if not by governments? Or do governments, on the other hand, use people’s inertia as an excuse for not tackling the gap between the rich and poor, even if the public perceive it as too large?

Exploring perceived advantage and disadvantage

People may tolerate different levels of inequality because of their different beliefs about its causes. Of the five countries we checked this for, we found that the UK stood out as the only country where laziness and lack of will is the most popular explanation of disadvantage, rather than social injustice (Figure 2). Of course some subgroups drive this effect more than others. For example, in the UK there is no obvious difference between how income groups answer this question while in Germany, agreement is much higher among low and middle income groups.

Hard work or privileged upbringing?

In all countries, people from all groups believe that hard work is an important way to improve one’s position (Figure 3). But when it comes to the importance of family background to get ahead the picture is different. This is important because people tend to have overly optimistic perceptions of their life chances and as a result overestimate social mobility – the extent to which people move up or down the social ladder. We found that higher income groups tend to downplay the importance of family background.

Figure 3. EVS and SASAS surveys: Education versus Income differences for “Why do people live in need?” and “Getting ahead: how important is [x factor]?” (not taking interaction between variables into account, not tested for statistically signifcance)

More questions than answers?

This survey data, considered highly reliable, quoted and re-analysed in countless academic studies and policy documents, is invaluable for comparing attitudes and beliefs at the national level. It provides the researcher with easily digestible descriptive data, and covers the conceptual ‘cycle’ of how people perceive a situation to be (tolerance of existing inequality), what, if anything, they want done to tackle it and what causes they may attribute to it.

But the data also shows that surveys and polls need to catch up with the current state of the inequality debate – which has become more nuanced, researched and politicised with every passing year. There is so much more they should unpack.

To mention just a few examples, surveys don’t help respondents distinguish between different monetary inequality measures like wealth and income. We also still know very little about how people apply the concept of the gap between the rich and poor to their own position in the income or wealth distribution. Do they even think about the whole distribution, or just focus on their own respective position in relation to middle or top incomes? Oxfam’s recent research has once more confirmed that median bias is real — most people falsely think they are in the middle of the income distribution. This in turn can hugely influence how they perceive the overall distribution to be, and whether this is fair. On top of this, more research is needed to separate misperceptions (false beliefs) from misinformation.

The challenge for Oxfam is to make the most of existing data and avoid duplication where it isn’t necessary, whilst also pushing the boundaries of how inequality attitudes should be measured.

We clearly need to make use of reliable data sources like the ones discussed in this post, comparable over space and time. Our preliminary look at this type of data suggests that tolerance of inequality, attitudes towards inequality-reducing policies and beliefs and values aren’t all the same across countries – let alone within them. But this should be far from the only kind of data accepted to unpack such attitudes – and there is a role for Oxfam in expanding the way they are measured. What is being missed out? Where are surveys falling behind the new dimensions uncovered through debates on inequality, for example on absolute over relative inequality? Our recent research on whether information on inequality actually makes a difference to people’s attitudes towards inequality is a step in this direction.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers