Duncan Green's Blog, page 94

June 6, 2018

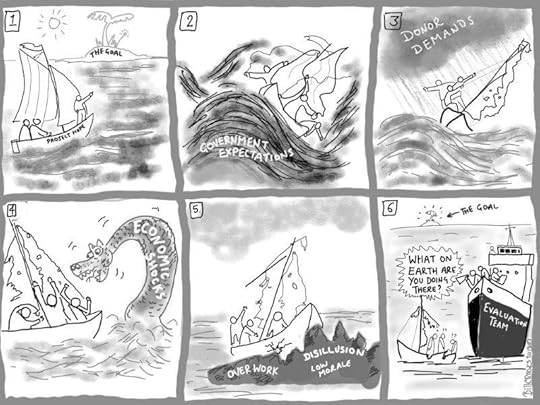

The Project Cycle in Complex Systems – cartoon version

Jo Rowlands spotted this gem in a recent Intrac Newsletter. It’s drawn by Bill Crooks, based on an original concept by Nigel Simister.

June 5, 2018

Turning ‘Leave No One Behind’ from promise to reality: Kevin Watkins on the Power of Convergence

This post is by Kevin Watkins, Chief Executive of Save the Children UK

How do you take your Sustainable Development Goals? With a generous sprinkle of motherhood, apple pie and good intentions? If so, the chances are you’re an enthusiast for the commitment to ‘leave no one behind’ in the pursuit of the 2030 development targets. Me too. It’s tough to think of a more elevated test of fairness. Yet we are in danger of allowing a hard-won commitment to equity that could – and should – guide policy design to become an empty slogan.

The SDGs define the international community’s global ambition for poverty eradication, shared prosperity and sustainability. Tucked away in the preamble ahead of the 17 headline goals and shopping list of 169 targets are the following words: “We wish to see the Goals and targets met…. for all segments of society. And we will endeavour to reach the furthest behind first.”

Press the pause button and reflect on that commitment. In effect, the SDG pledge is a commitment to ensure that progress happens first and fastest for those starting furthest away from the 2030 targets. This is a marked departure from Millennium Development Goals, which focussed attention on national average progress and turned a blind eye to rising social disparities. The SDGs establish progress with equity, or the pace of social convergence towards the 2030 goals, as the benchmark for measuring national performance.

Press the pause button and reflect on that commitment. In effect, the SDG pledge is a commitment to ensure that progress happens first and fastest for those starting furthest away from the 2030 targets. This is a marked departure from Millennium Development Goals, which focussed attention on national average progress and turned a blind eye to rising social disparities. The SDGs establish progress with equity, or the pace of social convergence towards the 2030 goals, as the benchmark for measuring national performance.

Underpinning the SDG agenda are two simple but compelling propositions. The first is rooted in ethics. The idea that the circumstances of a child’s parents, or the gender of the child, should determine their life-chances in education, health or employment is an affront to basic concepts of fairness, equality of opportunity, and social justice. The second proposition is rooted in more mundane arithmetic. Unless the rate of progress among those left behind exceeds the rate of progress for more advantaged groups, the SDGs are unattainable.

Consider the 2030 ambition of ‘ending preventable deaths’ among newborns and under-fives.

On average, death rates among children in the poorest households are twice the level for the wealthiest. The arithmetic corollary is that they will have to fall twice as fast to achieve the goal of ‘ending preventable child deaths’. Social gradients in child survival also mean that convergence is a powerful motor for saving lives. Eliminating the wealth gap in child survival in 2016 would have saved 2 million lives according to UNICEF.

The arithmetic of convergence can be illustrated by reference to the SDG threshold for child survival, which is 25

Figure 1: Nigeria

deaths for every 1000 live births (25/1000). Figures 1 and 2 looks at the trajectories required for the wealthiest and poorest 20 per cent in Nigeria and India, to achieve the 2030 target.

In the case of Nigeria, one of six countries with death rates in excess of 100/1000 live births, the simple convergence headline is that death rates for the poorest children must fall all at twice times the annualised rate for the wealthiest. In the case of India (Figure 2) the wealthiest 20 per cent have already hit the SDG target. Average child mortality rate is falling at a rate that will bring the target within reach. However, the poorest 20 per cent will not achieve the SDGs without a marked acceleration in progress relative both to the wealthy and the national average.

Figure 2: India

These are simple arithmetic exercises that draw on just one aspect of disparity. In the real world, wealth disparities intersect with regional, ethnic and wider markers for disadvantage. In the case of Nigeria, children born in the north-east face far higher death rates than those in the south. In India, marked disparities between states are reinforced by disadvantages associated with scheduled castes and tribes. But differential convergence pathways can help turn the spotlight on the public policy challenge at the heart of the SDG enterprise.

Accelerated social convergence towards the 2030 goals will require an unrelenting focus on the most disadvantaged. This has to go beyond the rhetorical flourishes that governments like to serve up at UN summits to the strategies they apply to combat poverty and extreme inequalities. Ensuring that public spending plays a role in equalising opportunity by allocating more resources to the less advantaged is an obvious starting point.

The time has come to translate the pledge to leave no one behind into a guide for policy design. Governments around the world should be putting in place national convergence plans consistent with their SDG commitments. These plans could include simple but credible targets like halving the wealth disparity in child survival or school attendance over a five-year period, linked to strategies for translating the targets into outcomes.

Of course, setting targets is not enough. In the absence of credible data to track progress among the most marginalised, ambitious targets can provide a smokescreen for complacency. One of the most disturbing findings to emerge from an excellent UNICEF report is that 520 million children are living in countries lacking data on at least two-thirds of the SDG indicators. Moreover, much of the data that is available from large-scale surveys and census documents is published intermittently – and survey samples often attach insufficient weight to the most disadvantaged.

Data deficits hide disadvantage and hamper genuine accountability for delivering on the SDG commitments. The  annual UN SDG report could set a standard both through systematic monitoring of progress for the world’s most deprived and marginalised people, and by identifying data gaps. But while global reporting serves a useful purpose national reporting to a country’s citizens is what will drive change. UN agencies and the World Bank should be doing far more to develop the data collection and reporting capabilities of national statistical bodies, and to support the generation of real-time digital data from health facilities, schools and communities in disadvantaged areas.

annual UN SDG report could set a standard both through systematic monitoring of progress for the world’s most deprived and marginalised people, and by identifying data gaps. But while global reporting serves a useful purpose national reporting to a country’s citizens is what will drive change. UN agencies and the World Bank should be doing far more to develop the data collection and reporting capabilities of national statistical bodies, and to support the generation of real-time digital data from health facilities, schools and communities in disadvantaged areas.

Here at Save the Children we have developed a Group Inequality Database that draws on a range of disaggregated sources. My colleagues are now developing convergence indicators that can be used to track national performance. which we hope will contribute to the wider debate. You can see a preview of our new data tools on our GRID website.

In the last analysis social convergence is an intensely political exercise. Translating SDG commitments into transformative outcomes for the most marginalised will require a sustained attack on inequalities that are underpinned by unequal power relationships, the skewing of resources towards the most advantaged, and overwhelming political indifference. Let’s face it, this is not an age marked by a drive to achieve greater equity.

All of which makes the SDG commitment something worth fighting for. Getting agreement on the cutting edge principle of ‘reaching the furthest behind first’ was not easy – and we should not allow that principle to join the crowded graveyard of development slogans recalled today primarily for their overwhelming irrelevance. (Remember ‘pro-poor growth’ anyone?)

Monitoring the pace of social convergence won’t change the world. But it’s an essential part of the tool-kit and not a bad place to start.

June 4, 2018

6 ways Aid Donors can help harness Religious Giving for Development

One of the consequences of writing a blog that covers some off-beat topics is that when someone’s organizing an event on one of them and can’t find qualified speakers, you get invited along to make up the numbers. So it was that I, a lifelong atheist, ended up on a panel at DFID last week on religious giving for development. DFID has identified this as an issue it wants to do more on, so it was looking for ideas.

The other speakers, Zenobia Ismael from Birmingham University (see her report on zakat here), and Jamie Williams from Islamic Relief Worldwide, were excellent, and focussed on Islamic giving. This comes in 3 main forms:

from Islamic Relief Worldwide, were excellent, and focussed on Islamic giving. This comes in 3 main forms:

Zakat: Muslims are required to give 2.5% of their savings every year, for a set of 8 philanthropic purposes set out in the Quran

Sadaqah: This is voluntary, and there are no restrictions on usage

Waqf: an endowment, used mainly to finance buildings, such as schools and mosques, but with the potential to be used for development programming.

Most attention has centred on Zakat, (which I’ve likened in the past to a global wealth tax), but Islamic Relief actually gets more money through the Sadaqah channel. This is partly because there are big arguments about how/when development qualifies under Zakat rules. Can it be spent on non-Muslims? Does it have to be spent within a year, near to where it was paid? There’s a lot of disagreement, and getting Islamic scholars to rule on this sounds pretty much like shopping around QCs to get a legal opinion that you like.

Beyond the scholars, there are big disagreements among Muslims – one young DFID staffer attending the discussion said that, as a Muslim, she could not understand why funding the SDGs would not be Zakat-compatible, but many Muslim donors think very differently – Islamic Relief has had to suspend some of its advice on this because of pushback from its donors.

When it came to me, I made the point that trying to get the aid business to take religion seriously is much bigger than just who gives what:

If you’re serious about ‘Working with the Grain’ of local societies and institutions, understanding the role of religion is crucial – eg see this study on educational reform in West Africa

There’s increasing interest about how social norms affecting attitudes and behaviours can be influenced on everything from violence against women to hand washing – it’s hard to think of any institutions that have more influence on norms than faith organizations. Not that all that influence is positive of course – lots of arguments over gender rights in many religions.

The closer to the ground you get, the more faith and religion appear on the radar – faith plays a crucial factor in agency and ‘power within’ among activists and communities in struggle

If you’re serious about pushing power and resources down to local level when responding to emergencies (aka ‘localization’), then faith organizations should definitely be in the mix – they are often where people turn when disaster strikes, and play a crucial role in helping communities recover

The faith organizations that ‘get’ development are often linked to shrinking religious congregations (liberal Protestants and Catholics). We need to understand and engage with the new, expanding evangelical churches.

But who does God give it to?

But then we got back to giving, and since DFID was looking for advice on how to support it, here’s what we suggested:

Be part of promoting a shift in understanding from charity to development. Worth seeing how to apply the lessons of previous norm shifts, eg on universal welfare as a right

Collect and publicise positive examples of religious giving

Use DFID match funding to convey the message to Muslim and other donors that they are valued

Data: I don’t normally suggest this, but there is a real vacuum here. Estimates of religious giving vary wildly, and we have precious little idea where it ends up. Measuring and tracking the amounts and purposes could go a long way to raising the issue’s profile

Promoting religious giving as a way to wean southern CSOs off their reliance on fickle aid flows (see previous post on Fundraisers without Borders)

Use its influence to get some of the other big donors on board (paging Melinda Gates….)

See also Aikande Clement Kwayu on donors’ blind spot on religion, and this longer read on religion and development by Manini Sheker

June 3, 2018

Links I Liked

We all need better influencing strategies for our bosses. Dilbert has useful advice on what works.

How Brexit will affect each ingredient of the full English breakfast – now you’ve got my attention.

Europe’s curse of wealth: migration and spiralling inequality. Branko Milanovic at brilliant best

Couple of me-related things. Speaking at the LSE launch of the World Inequality Report on Thursday, and the paperback version of How Change Happens is now on sale in bookshops – a snip at £8.99.

New US rules require large companies to disclose the ratio of their CEO’s wages to the firm average. Here’s the results by sector for 700 large firms, c/o The Economist. Take a bow Marathon Petroleum, with the highest ratio of 935:1.

New US rules require large companies to disclose the ratio of their CEO’s wages to the firm average. Here’s the results by sector for 700 large firms, c/o The Economist. Take a bow Marathon Petroleum, with the highest ratio of 935:1.

Ms Geek Africa competition. The latest winner is Salissou Hassane Latifa from Niger, who wrote an app that promises to help accident victims.

‘The likelihood of gaining tenure at a top economics department is about 26% higher for faculty with an A-surname than with a Z-surname. and harmful to collaborations (writes someone called Weber, who should probably change his name to Aardvark)

So as a migrant in Europe, all you have to do is scale four floors on the outside of a building and save a dangling baby, and you get citizenship and a job in the fire brigade. Kudos to Le Spiderman, but is this really the way to manage migration?……

May 31, 2018

What’s New in our Understanding of how Evidence Influences Policy? A view from Latin America

Following on Tuesday’s post on using evidence to influence policy in Guatemala, here’s

Enrique Mendizabal

, founder of On Think Tanks and the Latin American Evidence Week (October 22-29th)

22-29th)

It seems rather hard to come up with anything original to say in the field of evidence-informed policy – unless we consider the change from evidence-based to evidence-informed policy. The case study approach, which has been tried and tested – and continues to be tested – inevitably concludes that researchers need to communicate more and better; that policymakers need to develop different capacities – to access, appraise, analyse, use evidence; and, among other lessons, that context matters – oh, and that we’ve got to consider politics.

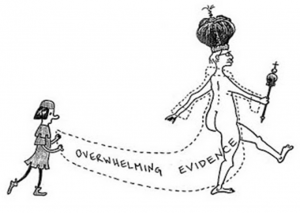

Those of us who work in this field appear forever bound to place far too much importance on the ideal role of evidence in policymaking. We are cautious of anyone suggesting that policymaking is value based and that evidence is no more than a useful tool (or fool). But ask any politician, and we have been asking many of them through dozens of events promoted by the Evidence Week in Latin America, and they will agree that emotions rather than facts drive policymaking forward – or backwards.

Theory?

There is, for sure, interesting research on the subject. Paul Carney’s and Kathryn Oliver’s work on the impossibility of adequately adapting evidence-informed medicine into evidence-informed policy asks an important question: should researchers really pursue impact? Then there is recent work on credibility – which is closely linked to emotion and, therefore, the use of evidence: Andrea Baertl’s study explores the factors that determine the credibility of research organisations, and of the evidence they produce. Spoiler: research quality is not at the top of the list.

(These studies stand out because they pay proper attention to the role of emotion.)

There is also much to learn from research that was never intended to answer questions related to evidence informed policy. Anthony King and Ivor Crewe compiled and analysed several cases of policy blunders by British governments. Their book offers rich insights into how some of the best educated, most capable, best resourced and informed people in Britain could mess it up so catastrophically. Their analysis suggests that the real gaps that need to be bridged are between policymakers’ and the public’s experiences of life (cultural disconnect) and between policy designers and policy implementers (operational disconnect).

They illustrate the pitfalls of groupthink rather well, too, although possibly not as eloquently as Michael Wolff’s Fire

Practice?

and Fury, which offers an unintended account of the Trump White House’ disdain for evidence – at least, for research based evidence. Christopher Rastrick’s paper on think tanks in the Trump administration presents a similar story. The personal and professional characteristics of the leader matter when trying to understand why an administration is close to policy research centres and keen on using evidence. It explains why Trump dislikes “outside” evidence and why Theresa May in the UK has been less ready to engage with think tanks than her predecessors – this last point was made by Nick Pearce at the OTT 2018 Conference.

One reason why these accounts stand out is precisely because they did not set out to find a desired role – or to test an expected role – for evidence. They offer hints at the ways in which information flows (or not) throughout the system. They acknowledge the influence of evidence but don’t overestimate its importance. They describe the way in which certain ideas have informed decisions but do not simplify the complex and long term process through which ideas emerge, consolidate and make their way into the mundane world of speeches, policy memos, business cases for new public programmes, or office squabbles.

To develop a convincing narrative of how research-based evidence helps inform policy decisions, it is far better to forgo our ex-ante theories of change and instead embrace the real world of messy, overlapping and start-stop stories with multiple characters and unpredictable plots. IFAD is attempting just that in its own efforts at monitoring policy engagement. This method does not set out to tell the story of how IFAD’s evidence informed policy; instead it simply wants to find out what happened.

To develop a convincing narrative of how research-based evidence helps inform policy decisions, it is far better to forgo our ex-ante theories of change and instead embrace the real world of messy, overlapping and start-stop stories with multiple characters and unpredictable plots. IFAD is attempting just that in its own efforts at monitoring policy engagement. This method does not set out to tell the story of how IFAD’s evidence informed policy; instead it simply wants to find out what happened.

These studies succeed because they present a dialogue between stories as told by the protagonists themselves. Each blunder in King’s and Crewe’s book is a conversation between several players and their ideas. Each battle between the Bannonites and Kushnerites in Wolff’s book is a clash between world views, personal and professional interests, and networks of influence. It is impossible not to find implications for evidence informed policy.

Not surprisingly, many coincide with the lessons emerging from the Latin American Evidence Week (Semana de la Evidencia), which in 2017 convened over 2,000 people who attended 53 events in 10 countries.

The festival offers a regional dialogue between policymakers, thinktankers, researchers, journalists, activists, business leaders and the public from which emerges a different narrative to the one we’ve become accustomed to:

Most policymakers actually do want evidence to inform their decisions and most researchers are constantly thinking about and trying new ways to draw attention to their work

Gold-standard evaluations aren’t the most useful source of evidence for decision making – most decisions require rather straightforward research and analysis

The world is not divided between qualitative and quantitative research and their supporters – everyone is quite happy to use both whenever possible

Testimonies are perfectly valid sources of evidence – and they are particularly legitimate ones and difficult for policymakers to dismiss

And it all comes down to dialogue – but not between researchers and policymakers to close the proverbial gap – they tend to be much closer to each other than the literature would have us believe; rather, between policymakers themselves, between designers and implementers, between the national and the local level, between sectors, between disciplines, between the various branches of government, etc.

Whether you are in Latin America or not, find out more at semanadelaevidencia.org and join the conversation.

May 30, 2018

Public Authority through the eyes of a Dead Fish

One of the highlights of last week’s conference in Ghent was a presentation by Esther Marijnen about her research in the Eastern Congo. Esther is trying to understand how rebel groups (of which DRC has many) see nature – across Africa, there is a long tradition of insurgents setting up bases in national parks. To do this she looked at (il)legal fishing in Virunga National Park (famous for its gorillas, where park rangers were recently shot by rebels/poachers).

the Eastern Congo. Esther is trying to understand how rebel groups (of which DRC has many) see nature – across Africa, there is a long tradition of insurgents setting up bases in national parks. To do this she looked at (il)legal fishing in Virunga National Park (famous for its gorillas, where park rangers were recently shot by rebels/poachers).

She spent time in the area, getting to know local people, including the fishing communities, who realized that unlike most of the conservationists, she is not only interested in gorillas, but also in humans. That trust enabled her to uncover how a commodity supply chain interacts with politics and rebellion.

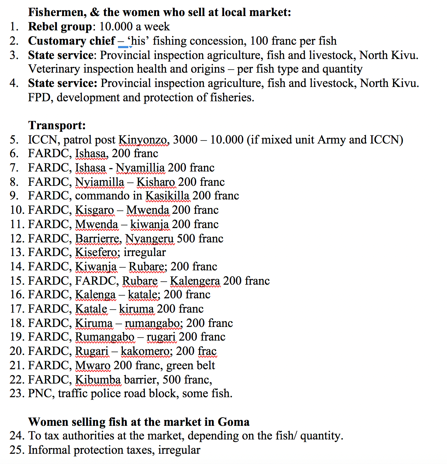

One way she did this was by jumping in a car and followed a motor bike transporting fish from the lake to the market, for which it had to cross both rebel and government-held territory. She recorded every bribe at every  roadblock, and added in the costs at both ends of the supply chain, ending up with 25 separate transactions (see pic).

roadblock, and added in the costs at both ends of the supply chain, ending up with 25 separate transactions (see pic).

That’s pretty fascinating in itself, but she also uncovered a chain of accumulating political impacts in terms of public authority, via the relationships triggered by the different stages of the fish’s journey.

At the lake (held by rebels), the granting of licenses to catch fish creates a level of legitimacy for the insurgents, building a social contract between them and the fishing communities, who value the predictability of knowing who they have to pay off and how much. This is all accompanied by the symbols of ‘stateness’ – lots of rubber stamps and forms.

Taxation can also create opposition if it is arbitrary or excessive, but the rebels are largely from the local community, and Esther reckons they can judge what is an acceptable level of taxation better than government outsiders. Moreover, while people deplore the extortion by the rebels, often under gunpoint, they say, ‘it is better to be extorted by my brother than by a foreigner’.

Yet, rebels are not the only ones involved in the fish commodity chain. Once the fish arrives in the villages, multiple state services also levy their official taxes. Often not making any distinction between fish that was ‘legally’ or ‘illegally’ acquired. When the fish is being transported the line between legal and illegal becomes even more blurry – government soldiers and the police also demand money at the numerous roadblocks on the way.

While this is an economic disadvantage for the fishermen and the transporters, it also allows them to continue their  business, which becomes very public, and so seen as a legitimate way to gain a livelihood. It also offers them a form of protection. If so many people with public authority are implicated in the trade, it becomes very difficult for the park management to crack down on it.

business, which becomes very public, and so seen as a legitimate way to gain a livelihood. It also offers them a form of protection. If so many people with public authority are implicated in the trade, it becomes very difficult for the park management to crack down on it.

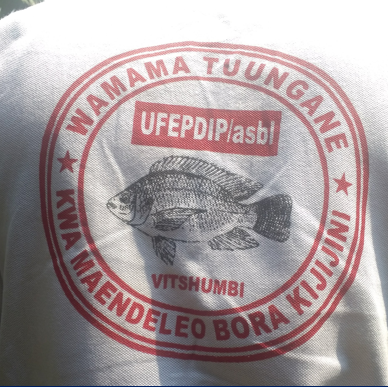

At the end of the journey the fish arrive at the market and are sold to networks of market women, who are organized in associations (see pic, which reads “mothers united for the good development of our village, Vitshumbi”).

Fascinating.

For the academic paper on this, see here.

May 29, 2018

What I learned about Public Authority from spending two days with a bunch of anthropologists, political scientists and others.

The Centre for Public Authority in International Development had its annual get together in Ghent last week. It really hurt my head, but the pain was worth it – I learned a lot. Here are some overall impressions, and then tomorrow, my top lightbulb moment – public authority through the eyes of a dead fish…..

Firstly, anthropologists are amazing. I was left with an impression of thousands of dedicated young researchers scattered around the shanty towns and villages of the globe, living with families, mucking in with the chores, getting to know people and societies in a far more profound way than I have ever done. They latch onto the kinds of messy events that the aid/development biz tends to airbrush out of its narratives. A whole case study on a poisoning incident in a Ugandan refugee camp. The ‘death of Auntie Marie’ in a poor neighbourhood in Sierra Leone. When potato sellers posted their list of rules in a Ugandan market the biggest fines for infractions were for members who resorted to witchcraft or falling in love…….

scattered around the shanty towns and villages of the globe, living with families, mucking in with the chores, getting to know people and societies in a far more profound way than I have ever done. They latch onto the kinds of messy events that the aid/development biz tends to airbrush out of its narratives. A whole case study on a poisoning incident in a Ugandan refugee camp. The ‘death of Auntie Marie’ in a poor neighbourhood in Sierra Leone. When potato sellers posted their list of rules in a Ugandan market the biggest fines for infractions were for members who resorted to witchcraft or falling in love…….

Secondly, the whole definition of ‘public authority’ has a problem. According to its project document, ‘CPAID uses the term ‘public authority’ to refer to any social institution or mechanism that exists beyond the immediate family and exercises a degree of voluntary compliance.’ That places a nice neat wall between public and private, but reality turns out to be messier than that.

In Sierra Leone family meetings including both immediate and extended family are ‘the dominant form of politics and political authority in everyday life’ (Jonah Lipton). They resolve disputes, determine what is/ is not socially acceptable and (in Sierra Leone at least) are much more female spaces than the male-dominated sphere of formal politics.

On the ground in Northern Uganda, the big problems over land are intra-family and intra-clan, not land grabs by big bad multinationals (sorry, campaigners!) and once again, are resolved by big family and community meetings that are largely off the radar of governance policy and programmes.

‘Love life histories’ in Uganda show both that love and (good) sex can flourish during wartime, and just how much conflict and intimacy are intertwined – war’s restrictions on mobility prevented traditional weddings from taking place, but Church weddings were still possible. That has big consequences since some customary rights for women are dependent on being traditionally married.

Thirdly, everything is fluid. In order for the aid/development sector to discuss issues and then devise projects, it has to use fixed concepts (families, communities, states, conflict) that remain reasonably constant as units of analysis. Once the anthropologists get involved, everything gets a lot more blurry. Lift the lid on ‘disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration’ and you start to question the whole idea of ex combatants returning ‘home’ and find a process of ‘circular return’, in which combatants bounce disconsolately between civilian and armed life, never really fitting in to either.

Thirdly, everything is fluid. In order for the aid/development sector to discuss issues and then devise projects, it has to use fixed concepts (families, communities, states, conflict) that remain reasonably constant as units of analysis. Once the anthropologists get involved, everything gets a lot more blurry. Lift the lid on ‘disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration’ and you start to question the whole idea of ex combatants returning ‘home’ and find a process of ‘circular return’, in which combatants bounce disconsolately between civilian and armed life, never really fitting in to either.

Finally, deep awareness and emotional intelligence in the field does not, sadly, carry across into the seminar room. Two days of back-to-back 20 minute presentations followed by Q&A (when time allowed). Some of the speakers read out papers in that special academic monotone that has me climbing the walls and silently screaming for release. Everyone seemed completely oblivious to other ways of engaging people or keeping some energy in the room. I realized this is partly just my problem though – when I asked participants which presentations they liked, several name-checked talks that were so badly delivered I couldn’t even take in what they were saying. Guess that must be an essential part of the academic training that I missed out on. (see here for longer rant about academic conferences).

May 28, 2018

What kind of Evidence Influences local officials? A great example from Guatemala

I met Walter Flores at a Twaweza seminar in Tanzania a couple of months ago, but have only just got round to  reading his fascinating paper reflecting on 10 years of trying to improve Public Health in Guatemala. It is short (12 pages), snappily written, with a very crisp, hard-hitting thesis, so no need to do more than provide some excerpts to whet your appetites:

reading his fascinating paper reflecting on 10 years of trying to improve Public Health in Guatemala. It is short (12 pages), snappily written, with a very crisp, hard-hitting thesis, so no need to do more than provide some excerpts to whet your appetites:

The Setting: ‘In Guatemala, because of decentralization, local public services are governed primarily by municipal governments and the Ministry of Health’s local and regional branches. This means that local authorities are actually in a position to address some issues of service quality, corruption, and abuse—though not deeper systemic issues, such as health budgets.

The Project: Over the last decade, the Centro de Estudios para la Equidad y la Gobernanza de los Sistemas de Salud (the Center for the Study of Equity and Governance in Health Systems, or CEGSS) has considered the question of how to use evidence to influence authorities and promote participation by users of public services in rural indigenous municipalities of Guatemala.

The Process: Our initial approach relied on producing rigorous evidence through the surveying of health care facilities using random samples. However, when presented to authorities, this type of evidence did not have any influence on them. In the follow-up phases, we gradually evolved our approach to employ other methods to collect evidence (such as ethnography and audiovisuals) that are easier to grasp by the non-expert public and the users of public services.

We found that evidence collected, analyzed, and systematized by the users of the health system was key to engaging the authorities. This conclusion was based on a systematic analysis of different methods for gathering evidence CEGSS used to document the conditions and user experience of local health services.

Between 2007 and up to now, we have implemented five different methods for gathering evidence:

1) Surveys of health clinics with random sampling,

2) Surveys using tracers and convenience-based sampling,

3) Life histories of the users of health services,

4) User complaints submitted via text messages,

5) Video and photography documenting service delivery problems.

Each of these methods was deployed for a period of 2-3 years and accompanied by detailed monitoring to track its effects on two outcome variables:

1) the level of community participation in planning, data collection and analysis; and

2) the responsiveness of the authorities to the evidence presented.

Our initial intervention generated evidence by surveying a random sample of health clinics—widely considered to be a highly rigorous method for collecting evidence. As the surveys were long and technically complicated, participation from the community was close to zero. Yet our expectation was that, given its scientific rigor, authorities would be responsive to the evidence we presented. The government instead used technical methodological objections as a pretext to reject the service delivery problems we identified. It was clear that such arguments were an excuse and authorities did not want to act.

Our next effort was to simplify the survey and involve communities in surveying, analysis, and report writing. However, as the table shows, participation was still “minimal,” as was the responsiveness of the authorities. Many community members still struggled to participate and the authorities rejected the evidence as unreliable, again citing methodological concerns. Together with community leaders, we decided to move away from surveys altogether, so authorities could no longer use technical arguments to disregard the evidence.

Our next effort was to simplify the survey and involve communities in surveying, analysis, and report writing. However, as the table shows, participation was still “minimal,” as was the responsiveness of the authorities. Many community members still struggled to participate and the authorities rejected the evidence as unreliable, again citing methodological concerns. Together with community leaders, we decided to move away from surveys altogether, so authorities could no longer use technical arguments to disregard the evidence.

For our next method, we introduced collecting life-stories of real patients and users of health services. The decision about this new method was taken together with communities. Community members were trained to identify cases of poor service delivery, interview users, and write down their experiences. These testimonies vividly described the impact of poor health services: children unable to go to school because they needed to attend to sick relatives; sick parents unable to care for young children; breadwinners unable go to work, leaving families destitute.

This type of evidence changed the meetings between community leaders and authorities considerably, shifting from arguments over data to discussing the struggles real people faced due to nonresponsive services. After a year of responding to individual life-stories, however, authorities started to treat the information presented as “isolated cases” and became less responsive.

We regrouped again with community leaders to reflect on how to further boost community participation and achieve a response from authorities. We agreed that more agile and less burdensome methods for community volunteers to collect and disseminate evidence might increase the response from authorities. After reviewing different options, we agreed to build a complaint system that allowed users to send coded text messages to an open-access platform.

We also wanted to continue to facilitate communities to tell their stories and experiences. Instead of presenting life- stories as text, we began helping communities to use photography and video to document their stories. Audiovisual evidence proved a powerful method to attract the interest of traditional media and other civil society organizations. Also, by using coded complaints sent via text messages and sending electronic alerts and follow-up phone calls to authorities, we were able to draw attention to service delivery problems in real time. This situation resulted in a “high” level of both community engagement and government responsiveness from officials.

stories as text, we began helping communities to use photography and video to document their stories. Audiovisual evidence proved a powerful method to attract the interest of traditional media and other civil society organizations. Also, by using coded complaints sent via text messages and sending electronic alerts and follow-up phone calls to authorities, we were able to draw attention to service delivery problems in real time. This situation resulted in a “high” level of both community engagement and government responsiveness from officials.

And the big takeway conclusion? In contrast to theories of change that posit that more rigorous evidence will have a greater influence on officials, we have found the opposite to be true. A decade of implementing interventions to try to influence local and regional authorities has taught us that academic rigor itself is not a determinant of responsiveness. Rather, methods that involve communities in generating and presenting evidence, and that facilitate collective action in the process, are far more influential. The greater the level of community participation, the greater the potential to influence local and regional authorities.’

Great stuff. The big omission, for me, is any discussion of why this is the case. Why do officials find testimonies more convincing than hard data? Is it because they prefer a human narrative, or because these are the voters who can influence their political masters? More research needed, as ever.

May 27, 2018

Links I Liked

Globally, $1.7 Trillion was spent on the military in 2017. The highest since End of Cold War. = 13x the volume of aid, and $230 for every person on the planet.

Are economists’ standard solutions part of the problem in fragile states?

Lots to read for ‘Doing Development Differently’ nerds:

On the ‘Care Insights’ blog, Care’s Gilbert Muyumbu thinks DDD is too Northern. His governance colleagues respond

Alan Hudson wants to open a dialogue between DDD and the Open Gov lot

The Harvard team behind PDIA are producing practice notes on their work, including case studies and eventually a toolkit. Not usually a big fan of toolkits, but this one might be worth it.

Fighting HIV with MTV in Nigeria. The impact of edutainment on social norms. If you like your evidence RCT’d this one’s for you.

Where is the ‘African’ in African Studies? ht David Mwambari

This is both charming and a fascinating portrait of a child comic genius. ‘I don’t try to be funny or it’s not funny’

May 24, 2018

What are the politics of reducing carnage on the world’s roads? Great new paper from ODI

There’s a form of casual violence that kills 1.25 million people a year (3 times more than malaria) and injures up to 50 million more. 90% of the deaths are of poor people (usually men) in poor countries. No guns are involved and there’s lots of things governments can do to fix it. But you’ll hardly ever read about it in the development literature, although road safety did make it into the Sustainable Development Goals (as did everything else, it has to be said) – targets 3.6 and 11.2 for SDG geeks.

million more. 90% of the deaths are of poor people (usually men) in poor countries. No guns are involved and there’s lots of things governments can do to fix it. But you’ll hardly ever read about it in the development literature, although road safety did make it into the Sustainable Development Goals (as did everything else, it has to be said) – targets 3.6 and 11.2 for SDG geeks.

So hats off to ODI (again) for not only painstakingly building the case for taking action on a major cause of death and misery in poor countries (see below), but also exploring the politics and institutions that so far have prevented governments from taking action.

I’ve just been reading the overview report of its Securing Safe Roads project, and it’s a model of its kind. Succinct, politically savvy and well evidenced, based on case studies from one municipal disaster zone (Nairobi), one city that’s made big strides (Bogotá) and one that lies somewhere in the middle (Mumbai). Here are some highlights:

Firstly overall, it’s bad and getting worse: ‘Traffic collisions are the leading cause of death among children and young people globally. Fatalities have increased in most low- and middle-income countries over the past 10 years. The World Health Organization estimates the annual economic cost of traffic fatalities and injuries to be around 3% of global gross domestic product (GDP).’

Now to the case studies:

‘In all three cities, pedestrians account for more than 50% of fatalities, with working-age males making up between 65–80%. Motorcycles display a startlingly high level of risk in Mumbai and Bogotá, making up more than 30% of fatalities. The wider economic impacts of poor road safety in these cities (such as loss of income and opportunity for families) are likely substantial. All three cities have made efforts to improve road safety, but progress has been  uneven:

uneven:

Nairobi. Politicians focus on large-scale, car-oriented projects that generate short-term political rewards. Legal or regulatory changes to improve road safety are strongly resisted by powerful interest groups. Recently created institutions dedicated to road safety present an opportunity for better coordination and proactivity. A recent plan for non-motorised transport also shows a promising shift in the attention it pays to vulnerable road users.

Mumbai. National calls for road safety reform have had little impact at the local level. Politicians focus on new major road projects, without integrating road safety considerations – an approach that is seen as more tangible and politically feasible. A Supreme Court ruling that requires states to create road safety plans may improve things but the need to advance other reform avenues remains.

Bogotá. In just 10 years (1996–2006) the city halved traffic fatalities. This was due to a combination of institutional and public transport reform, the reframing of road fatalities as a public health issue and investment in safe infrastructure. Fatality numbers have since plateaued. The city is seeking to catalyse further improvements through the application of a system-based approach to road safety.’

But rather than simply lamenting the carnage, the ODI starts to explore the politics that underlie inaction. In addition to lack of coordination between government bodies, and poor data:

‘Road safety is not a political priority. Currently, road safety lacks political salience. It is often subordinated to  other priorities, and is perceived to be in direct conflict with efforts to reduce motor vehicle congestion. Therefore, while there is little opposition to improved outcomes, the reforms that are needed can be controversial. Instead, politicians deploy their influence and funding where they think they will be able to get greater visibility and recognition from other politicians, interest groups and the public.

other priorities, and is perceived to be in direct conflict with efforts to reduce motor vehicle congestion. Therefore, while there is little opposition to improved outcomes, the reforms that are needed can be controversial. Instead, politicians deploy their influence and funding where they think they will be able to get greater visibility and recognition from other politicians, interest groups and the public.

Road safety is seen as an issue of personal responsibility, rather than government (in)action. Both decision-makers and the public tend to blame individual road users for collisions, rather than systemic issues such as infrastructure (or the lack thereof), weak regulation and planning or safe vehicles. Individuals often don’t think they will be affected by collisions, and often aren’t aware of the full array of options available to improve their safety. As a result, they tend to support short-term solutions and reactive measures, such as the simple expansion of a road network. These do not necessarily improve long-term road safety outcomes.’

The paper also comes up with some sensible suggestions for overcoming political paralysis:

Bundle road safety with more prominent or popular issues (eg public transport or congestion) and try to reframe it as eg a public health or equality issue

Build alliances across government. Both support for and opposition to road safety can exist at all levels: national, regional and local.

Take advantage of wider institutional and governance reform. For example, when Bogotá established an elected mayor and improved institutional coordination and accountability, it boosted public faith in local institutions and created a willingness to follow local regulations. The door was open for road safety reformers.

If there’s one thing I would add, it’s more on the link with class/inequality. If (generally wealthier) car drivers oppose road safety measures that largely benefit poor people, and politicians tend to listen to the rich, how do you break the political logjam? Does linking road safety to poverty and inequality help?

Congrats to ODI – this is really important work.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers