Duncan Green's Blog, page 92

July 4, 2018

Public Pressure + League Tables: Oxfam’s campaign on food brands is moving on to supermarkets.

‘First the brands, now the retailers.‘ That was the reaction of a senior staffer at Mars – one of the 10 biggest global food manufacturers targeted in our award-winning Behind the Brands campaign – to the Behind the Barcodes launch last month. Why did we choose supermarkets as our follow-up campaign, and what if anything is different this time around?

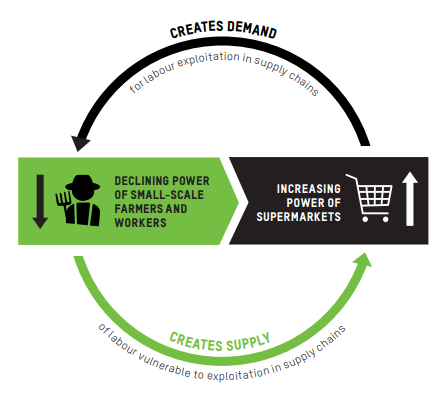

While supermarkets seem even further removed than the brand manufacturers from the producers and workers we aim to benefit, in many products they are the dominant lead firms in food value chains. From bananas to orange juice retailers are taking control and their private labels gaining market share. As the last link in the chain they have enormous positional power to set prices and other contractual terms over all other actors – even the big brands. The UK’s Marmite wars gave a taste of the power relations at play in that regard.

Their power is borne out in our new research. We show that both in aggregate and in the 12 food product chains we looked at in more depth, it is supermarkets that capture the biggest share of the end consumer price of any actor in food value chains, and that they have seen their share grow the most over the past 15-20 years. They’re also the entry point to the food chain for millions of consumers around the world – good targets therefore for a public campaign (unlike the big grain traders, for example).

But what difference has this choice made to the campaign model and theory of change?

Some things remain the same: most notably, we’ve made another scorecard. This one has 4 themes – ‘transparency’, ‘workers’, ‘farmers’ and ‘women’ – instead of 7, and we thoroughly revised and updated all indicators. We’ve dropped the themes related to natural resource rights not because they don’t matter, but for greater focus with a sector we judged has further to travel at the outset than the big food brands.

Some things remain the same: most notably, we’ve made another scorecard. This one has 4 themes – ‘transparency’, ‘workers’, ‘farmers’ and ‘women’ – instead of 7, and we thoroughly revised and updated all indicators. We’ve dropped the themes related to natural resource rights not because they don’t matter, but for greater focus with a sector we judged has further to travel at the outset than the big food brands.

The initial scores bear that out: there are no clear champions and lots of laggards. The highest score of any company on any of the themes is just 42%, and in each theme several companies score 0%. Once again the lowest scores are found in the ‘women’ theme, where only Walmart scores more than 10%.

The Behind the Brands scorecard helped drive a race to the top, and we are looking for the same again. The campaign model will again see us run shorter public campaign spikes on particular issues – starting with workers’ rights – and targeting particular companies as a complement to the scorecard. We learned in Behind the Brands that this focused public pressure in addition to the scorecard was critical in driving the biggest advances from companies (we’re not the first NGO to produce a scorecard, after all).

But there are some big differences in our approach this time around too.

First, this campaign is much more decentralised than Behind the Brands. We considered spotlighting the biggest 10 global supermarkets again, but the market dynamics are quite different at the retail end of the chain. While many of the big players have internationalised their presence – US Walmart operates in 29 countries, German Lidl in 26 and South African Shoprite in 15, for example – most don’t compete directly in the same markets, where a range of smaller national players control significant market shares too.

A more decentralised approach fits Oxfam’s internal dynamics too. The big Northern Oxfam affiliates were the gatekeepers to the Behind the Brands target companies. But in line with the Oxfam 2020 vision we wanted a model this time that could facilitate national campaigning in the South too.

While we have launched versions of Behind the Barcodes in Germany, the Netherlands, the US and the UK, we’re thrilled that our Thailand team have launched their version today, and that a related campaign from the Sustainable Seafood Alliance Indonesia – Di Balik Barcode – launched last week. We hope Oxfam teams in Italy, Brazil and Southern Africa will be among those joining over the coming year

The resulting campaign model is certainly more complex to manage. We’ve ended up with two campaign names – it’s called Behind the Price in some places – and a lot of nationally-tailored annexes to our launch report as a result. But we think we have enough ‘glue’ to make this more than the sum of its national parts.

We’ve already heard from European supermarkets that want to know how Walmart outscores them. We’ve been pointing out to German and Dutch supermarkets how far they lag behind international peers. The campaign is on

the radar of companies like Aldi and Lidl in several of their markets. While our campaign targets may not all be direct competitors, we are making it much harder for them to hide behind the inaction of others in their own market.

Two other key things are different this time. We have a bigger focus on inequality in our problem analysis. By showing how the inequality of power is at the root of human suffering in food supply chains, we are shining a spotlight on one sector of a global economy that, as we argued in this year’s Davos report, rewards wealth over women’s work.

And where Behind the Brands could be criticised for putting too much emphasis on voluntary action by companies, we are much clearer this time on the role that governments must play in protecting human and labour rights in food supply chains. We’re pushing for EU action to regulate supermarket unfair trading practices and calling for mandatory due diligence legislation in Germany, for example. Our research shows that from setting adequate minimum wages and agricultural commodity price support schemes to tackling entrenched norms that discriminate against women, public policy matters.

So we are building on the best bits of Behind the Brands, while innovating for Oxfam’s new operating context. The result is a much more complex model, but – if it works – one that could be the future of how Oxfam campaigns.

The post Public Pressure + League Tables: Oxfam’s campaign on food brands is moving on to supermarkets. appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 3, 2018

Internal battles within partner governments are what determine change. That has big implications for aid.

internal reform battles within governments and trying to help those fighting poverty from within.

Recently a line stuck in my mind from one of Duncan’s recent posts about adaptive programmes with developing country partners: `if you introduce donors into that arrangement, ownership is diluted, and donor priorities and processes take over – the donors provide the recipe, and at best, the government gets to decorate the cake.’ Harsh surely? Are we really that bad? But the reason that it made me pause is that those of us who have worked for donors can probably think of one or two instances when it has not been that far from the truth – less often than Duncan might think, but occasionally it does happen.

For example, I now work with a UK government unit, NSGI, that entails being more operational than I have since my NGO days. NSGI partners directly with the institutions of other governments (usually their policy co-ordinating bodies) not as technical advisers but as peer civil servants working together on common issues. This means spending time inside partner institutions rather than just working on those institutions. The role has made me more circumspect about those occasional conversations with international donors, who have never visited their partner’s offices, and yet tell me definitively how good or bad it is.

Now I know from experience that this is a minority– the vast majority of colleagues are practitioners who see

Internal Battles 1: Turkey

collaborating with partners as the best part of their job. Even so the idea of imposed `recipes’ resonates with a development literature in which the idea of clinical distance can seem pervasive, the notion of the outside view as unbiased and clear. Hence when I am asked to review a political-economy analysis that has been commissioned, I find they often excel at recounting history and current affairs – but tell me very little about what people within governments actually think. The counterpart can be portrayed as a lab rat to be dissected while we talk about what we plan to do `to’ the institutions (make them more accountable, improve their financial management) rather than what they will do with us.

It is a difference that helps to explain why the ‘results frameworks’ that get tied to programme documents can sometimes be enticingly ambitious (for the approver) while also being wholly unrealistic. This sense of distance also helps to explain why sometimes those project documents can differ markedly from the strategies of the internal champions of pro-poor change (who are often fighting a series of small incremental battles).

These issues are not new. Ideas of working with the grain, and with reform champions are old, but Duncan’s blog suggests that issues still remain. Perhaps Pablos Yanguas’ recent book `Why we Lie about Aid’ captures the problem, suggesting that outsiders struggle to discern the roles of `incumbents’ and `challengers’ in struggles for change:

‘In practice, development is not a process of change, but a tug-of-war between reform mobilisation and demobilisation. These are competing processes in which challengers and incumbents, respectively, work to organise co-ordinated action for change or pre-empt and minimise the success of such action.’

When I asked one counterpart for a view of how donors could help them to deliver reform they described the

Internal Battles 2: Mexico

challenge in a similar way , but they then went on to add that getting donors to join such efforts is tough, given how often donor staff change and not always with sufficient handover.

For donors, none of this is easy – and the challenges create a risk that it becomes simpler to problematize the partner: elites are bad, mad and inept; or instead to blame the previous approach (my predecessor had no idea!). The underlying development principles get lost: that the counterpart knows more than you, and that locally-generated solutions are likely to be better informed.

Over the years, the programmes that I have worked on that I pull to the fore in conversations (rather than pushing to the back), and which really delivered, are usually the ones that owed less to lengthy diagnostics and experts and more to organic (even serendipitous) emergence from local voices. Which makes me think that Pablo Yanguas raises a useful challenge – can we as outsiders, working with our local colleagues, better discern what will support reform mobilisation, perhaps making our `PEA’ an ongoing conversation rather than a dusty and distanced report?

Of course, the requests of the challengers may not always be possible, or wise to support; the role of the donor is still to look clearly at what comes from often conflicting local points of view. But if the emphasis is on engaging with Yanguas’ internal battles between challengers and incumbents then at least decisions on where to lend weight becomes a reflection of context – not a false ideal of clinical distance.

Internal Battles 3: South Korea

My own experience is that the vast majority of donor colleagues know this full-well, hence the desire to find out what ideas like Thinking and Working Politically and Doing Development Differently really mean for them. Systems and process may not always help, but the desire to support the local recipe as it cooks-up positive change for communities has never gone away.

The post Internal battles within partner governments are what determine change. That has big implications for aid. appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 2, 2018

Simplicity, Accountability and Relationships: Three ways to ensure MEL supports Adaptive Management

recent Bologna workshop.

The week before Duncan was slaving away in Bologna on adaptive management I was attending an Asia Foundation ‘practitioners’ forum’ in Manila. The focus of the event was on Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning for Adaptive Programming.

The idea for the event seems to have been catalysed by an independent review of the well-known Coalitions for Change initiative which – like nearly all reviews I’ve ever read – recommended that the program needed to undertake more systematic monitoring and evaluation. So, in the developmentally entrepreneurial spirit that the program is renowned for, they invited a whole bunch of folk to Manila to help them out.

This involved of people working on a variety of programs in Sri Lanka, Nepal, Myanmar, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and of course the Philippines, folks from ODI and DLP, a spattering of consultants [is that the right collective noun? ed], a few academics as well as some UN, EU, USAID, and DFAT staffers.

Whilst some of the debate was reminiscent of ‘governance’ discussions of ten years back – i.e. we need to build ‘capacity’ to do this stuff, or we need to get the technical stuff right – there was also some recognition of the politics of evaluation, as well as the organisational obstacles that mean that learning nearly always gets trumped by bureaucratic demands. As one staff member of Coalitions for Change’s put it, as a front line operative James Bond

Contemplating his indicators

is the best role model, and ‘James Bond didn’t write reports’!.

Some key take-aways for me were:

Simple rules for complex situations. Many of the programs represented were trying to simplify the processes and the language they used. Like others, they recognised that dealing with complexity was not helped by having overly intricate procedures and processes. Rather, simplicity encourages greater flexibility and responsiveness. Experience had also told them that simple evaluative questions and things like outcome mapping’s use of ‘plan to see’, ‘like to see’, ‘love to see’ as progress markers, made a lot more sense to staff and communities than more esoteric categorisation of hundreds of performance indicators into narrowly defined output/outcome/impact boxes.

Reframing accountability. Much of the discussion was focused on the challenge of managing accountability to donors, or ‘principal-agent’ forms of accountability, and how this could undermine processes of adaptation and learning. Yet interestingly, a number of the examples given of effective learning were actually forms of social, peer or indeed political accountability. Participants described the use of Facebook and viber to share pictures and records of meetings or events with colleagues; citizen report cards to get feedback on services; and empowering communities to use drones to detect illegal logging or mining. All of which suggest a more rounded concept of accountability might not only improve monitoring and evaluation, but create different forms of incentives to promote learning and adaptation.

Gender, teams and categorical thinking. As one presenter suggested, we don’t need a theory of change – we

Not your average development wordle

need a theory of people! Relationships, trust and notions of ‘being in it together’ are critical for teams, networks or coalitions to admit mistakes, be honest about uncertainty and therefore be in a position to learn from failure as well as success. And yet these things are not only hardest to measure, the measurement process can also distort those relationships. In similar ways the lack of attention that is sometimes given to questions of gender relations in programs that are ‘Doing Development Differently’ or ‘Thinking and Working Politically’, can mean that they focus on formal institutions and more visible forms of power. In both cases, this misses the relational aspect of interactions, power and politics and therefore the underlying dynamics that produce and re-produce outcomes. Ongoing action research, social network analysis, the use of diaries and apps, and varieties of outcome mapping and harvesting perhaps hold more promise for capturing changes in these kinds of relationships

For thoughts from someone else who was at the event see Arnaldo Pellini’s blog. A workshop report will be out in a few weeks.

The post Simplicity, Accountability and Relationships: Three ways to ensure MEL supports Adaptive Management appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 1, 2018

The Rise of the Robot Reserve Army: Working Hard or Hardly Working?

you actually having to read it, they have helpfully picked out the headlines.

The rise of a new global ‘robot reserve army’ will have profound effects on developing countries but will it mean people will be working hard or hardly working?

Stunning technological advances in robotics and artificial intelligence are being reported virtually on a daily basis: from the versatile mobile robots in agriculture and manufacturing jeans to autonomous vehicles, and 3D-printed buildings.

In fact, the International Federation of Robotics estimates that next year the stock of industrial robots will grow by more than 250,000 units per year concentrated in production of cars, electronics, and new machinery.

In some domains, emerging economies are actually ahead of richer countries. Take for example, Beijing’s driverless subway line or mobile phone-based finance in Kenya. Robots could even partially replace researchers and academics. So, this is really, really quite serious now…

This year’s World Development Report focuses on the changing nature of work (although its messages feel oddly dated). And it’s not the only one. A broad range of international agencies have recently flagged such issues relating to the future of employment in the context of automation ADB, the ILO, the IMF, UNCTAD, UNDP, UNIDO and the World Bank again, and again. Ditto the private sector folks at McKinsey Global Institute, the World Economic Forum and Pricewaterhouse. In fact, the International Labour Organization (ILO) has gone as far as launching a Global Commission on the Future of Work.

So, why does it matter?

What does automation mean for developing countries? Are the East Asian pathways to development based on job creating manufacturing-led growth gone forever? Will 1.8bn or two-thirds of the workers in developing countries need to find new jobs (as the World Bank says they will)? Is a global universal basic income needed as Indonesian Minister of Finance proposed at the IMF and World Bank meetings? Does every developing country need to set up  a ministry of automation as Thailand has done?

a ministry of automation as Thailand has done?

In a new paper we take a closer look at what we call the rise of the robot reserve army (and here’s the podcast at LSE) and what it means for the future of economic development and employment in particular in developing countries. It’s all part of a new project on structural transformation and inclusive growth that studies what we’ve called the ‘developer’s dilemma’.

‘What’s the developer’s dilemma?’ we hear you cry (we can dream). It’s this: structural transformation, aka genuine economic development (not just commodity fueled growth), often leads to rising inequality unless public policy intervenes. At the same time inclusive growth is more likely with steady or even falling inequality. That’s the developer’s dilemma.

In the years ahead big issues such as automation, but also deindustrialization are important mega-trends. And it’s important not to forget the historical experience of economic development which points towards the case for ‘trickle along’ economics.

In this context, automation is clearly of significance to the future of economic development, the future of work and point towards the need to develop new strategies for economic development in developing countries.

That said, interest in the impact of technological change is of course by no means new. There’s the detailed empirical study of Leontief and Duchin from the 1980s and, going further back, the work of W. Arthur Lewis, Marx, Ricardo and Schumpeter.

So, what did we find? Continuing the Simpsons and the robots theme, we have three headlines (why is it always three?):

D’oh! Automation is not just a rich country issue.

The bulk of thinking on the economic implications has so far focused on advanced industrialized economies where the cost of labour is high and manufacturing shows a high degree of mechanization and productivity. Yet, the developing world is both affected by automation trends in high-income countries and is itself catching up in terms of automation.

Automation is likely to affect developing countries in different ways to high-income countries. The kinds of jobs common in developing countries—such as routine agricultural work—are substantially more susceptible to automation than the service jobs—which require creative work or face-to-face interaction—that dominate high-income economies.

Duh! Automation is not only about technology.

The current debate focuses too much on technological capabilities, and not enough on the economic, political, legal, and social factors that will profoundly shape the way automation affects employment. Questions like profitability, labour regulations, unionization, and corporate-social expectations will be at least as important as technical constraints in determining which jobs get automated, especially in developing countries.

¡Ay, caramba! Pay more attention to stagnating wages than unemployment.

In contrast to a widespread narrative of ‘technological unemployment’ (© John Maynard Keynes), a more likely impact in the short-to-medium term at least is slow real-wage growth in low- and medium-skilled jobs as workers face competition from automation. This will itself hinder poverty reduction and likely put upward pressure on national inequality, weakening the poverty-reducing power of growth, potentially placing social contracts under strain.

As agricultural and manufacturing jobs are automated, workers will continue to flood into the service sector, driving down wages, leading to a bloating of service-sector employment and wage stagnation but not to mass unemployment, at least in the short-to-medium term.

How developing countries should respond in terms of public policy is a crucial question.

In sum, developing countries face real policy challenges unleashed by automation.

Given the pace of technological change, upskilling strategies are unlikely to be a panacea. Safety nets and wage subsidies may be desirable, but the question remains how to finance them (without making labour more costly and thus exacerbating a trend towards replacement). Investing in labour-heavy sectors such as infrastructure construction, tourism, social services, education or healthcare provision may be a way for developing countries to manage disruptive impacts of automation though these would imply major public investments and do not in themselves constitute a long run strategy for economic development. In the longer run the moral case of a GUBI (global universal basic income – remember, you heard the acronym here first) may become overwhelming.

So those are the headlines. For the real nerds, we’ll blog in more detail on drivers of automation, our theory on the effect of automation in developing countries; the forecasts of automatability and employment displacement; and different approaches to public policy responses.

And here’s Homer, showing how not to do it

The post The Rise of the Robot Reserve Army: Working Hard or Hardly Working? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

June 28, 2018

Are Missionaries naturally suited to ‘Doing Development Differently’ and Advocacy?

colonialism and imperialism. I’m sure there has sometimes been truth in that, but talking to a roomful of them in Dublin earlier this week, at the annual meeting of Misean Cara (a membership network for missionary organizations) I got a much more positive impression, and it got me thinking about the link between missionaries and ‘doing development differently’.

Misean Cara’s strategy sets out what it calls the ’missionary approach’, based on a set of five values:

Respect: Due regard for the feelings, needs and rights of others and the environment

Justice: Solidarity with those who are marginalised and advocacy for what is right, fair and appropriate

Commitment: Long-term dedication to and accompaniment of people amongst whom we live.

Compassion: Empathy with and understanding of the reality others live

Integrity: Transparency and accountability in all our activities.

That approach strikes me as both refreshingly human and highly compatible with DDD or the ‘power and systems approach’ I set out in How Change Happens.

Missionaries exemplify long termism and a deep knowledge of context – the room was full of priests, religious sisters and lay people who had spent decades in the same community, learning the language and becoming deeply immersed in local culture – the kind of embeddedness that Rory Stewart laments has been lost from the aid and diplomatic sector. They value people and relationships, not blueprints and policy documents.

It’s really not like this any more

Missionaries also model another idea I’ve been talking about in recent years – they are living proof that one alternative to the dead hand of the project is to directly support leaders instead. Find charismatic individuals who are likely to make change happen and support them to do so without having to concoct endless project proposals to justify the grant. Oh wait, isn’t that what missionaries are?

Their deep and permanent roots in communities should make them ideally placed to do advocacy, something that Misean Cara is encouraging its 90 member organizations to explore. But some of the missionaries I met, many of whom are elderly, though insanely energetic, confess to feeling disempowered by the impenetrable technocracy of the aid business, and its paraphernalia of methods, compliance requirements, indicators and plans. If anything, they are too impressed by the technocrats, too humble about their own achievements, knowledge and ability to work with communities to bring about change.

But there are also some downsides and challenges that are particularly acute for missionaries contemplated a leap into advocacy:

They are traditionally linked to direct service provision, running schools and clinics across Africa and beyond. Getting into advocacy is likely to create tensions between that way of working, and the need to improve the quality and quantity of services provided by the state

How Change Happens, and the way INGOs and others talk about advocacy, assumes a high level of intentionality – outside organizations, hopefully working closely with local CSOs, decide what they want to achieve, and build a theory of action to get there. But there is an alternative approach – solidarity, whereby an outside organization backs its local partner through thick and thin, takes its lead from then, and doesn’t try to impose its own agenda. That feels in some ways a more natural fit for missionary organizations, but is a nightmare to raise money for – basically asking for core funding for local organizations with no strings attached.

The other asset that missionary organizations often fail to capitalize on is that priests and nuns are sitting on a vast range of stories about the lives and struggles of the communities in which they live and work. They may not fit easily into project reports, but they are real and moving. And occasionally, some of them are hilarious. The Columban Fathers once regaled me with stories about the christenings they had performed across Latin America, and the tendency of their parishioners to invent new names based on the English words they had read on their shanty town walls, or on passing cars. There are people around the continent glorying in names such as Rangerover, Thissideup and Iloveny (the last from a number plate – got it ?).

range of stories about the lives and struggles of the communities in which they live and work. They may not fit easily into project reports, but they are real and moving. And occasionally, some of them are hilarious. The Columban Fathers once regaled me with stories about the christenings they had performed across Latin America, and the tendency of their parishioners to invent new names based on the English words they had read on their shanty town walls, or on passing cars. There are people around the continent glorying in names such as Rangerover, Thissideup and Iloveny (the last from a number plate – got it ?).

I imagine some readers will find this post naïve or offensive. After all, don’t missionaries exemplify the ‘white saviour complex’ that we dislike so much and want to get away from? But a) an increasing proportion of missionaries are local – the room was pretty diverse – and b) ask yourself which is more illegitimate – a consultant (or INGO strategic adviser, for that matter) who flies into a developing country thinking they have all the answers on their laptop, or a priest or sister who lives in the same community for decades, is trusted, and can accompany and support them in their struggles?

The post Are Missionaries naturally suited to ‘Doing Development Differently’ and Advocacy? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

June 27, 2018

Seven Rules of Thumb for Adaptive Management – what do you think?

Adaptive Management (aka Doing Development Differently, Thinking and Working Politically) seems to be flavour of the month, at least in my weird bubble of a world, so the next week is going to feature a series of posts on different aspects of what looks like a pretty important ‘movement’

First up, at one of the sessions at the Bologna workshop that I wrote about recently, we tried to identify some ‘rules of  thumb’ for those wishing to make adaptive management approaches a core part of their organization. The fact that the workshop mainly involved people involved in the nitty gritty of monitoring, evaluation and learning in a range of INGOs and aid donors gave this a particularly practical angle. We tried to avoid ending up with a load of questions (the usual end point of these conversations). We consciously pursued ‘rules of thumb’ (which some of the group called ‘principles’, while the pointy-headed might prefer ‘heuristics’) because the last thing we wanted to come up with was a new prescriptive toolkit/future logframe.

thumb’ for those wishing to make adaptive management approaches a core part of their organization. The fact that the workshop mainly involved people involved in the nitty gritty of monitoring, evaluation and learning in a range of INGOs and aid donors gave this a particularly practical angle. We tried to avoid ending up with a load of questions (the usual end point of these conversations). We consciously pursued ‘rules of thumb’ (which some of the group called ‘principles’, while the pointy-headed might prefer ‘heuristics’) because the last thing we wanted to come up with was a new prescriptive toolkit/future logframe.

Here’s what we came up with – not sure we’re there yet, so feel free to add/comment/critique etc.

RoT 1. Create ‘Enabling Conditions’ for AM in your organization. How?

Build an institutional ‘culture of curiosity’ in your organization, which rewards and resources reflection and learning

Agree clear upfront parameters for levels of decision making – who decides what?

Find the right people for the initial core team

RoT 2. From ex ante Planning to ‘Sense Making Directed Improvisation’ (ref Yuen Yuen Ang). How?

Directed: Seek sufficient analysis to understand relevant parts of the system, starting with a hypothesis that sets your direction and gives you the questions to inform your reflection and adaptation

Improvisation: Engage and empower field staff and partners to develop and act on both tacit and explicit knowledge

Create spaces for sense-making at the nexus of strategy and implementation

Constantly revisit and refine your theory of change and your theory of action, and the links between them. (Theory of Change = how the system changes; Theory of Action = how we intend to change the system)

RoT 3. Just Enough/Good Enough AM. How?

‘Enough’ means adequate for decision making and action to remain agile for adaptation and proportionate to institutional/donor needs. For example:

Good enough AM to match the complexity of system (some systems are simple/complicated and don’t need AM)

Just enough Standardization to enable local adaptation

Just Enough planning detail for the level of management, and the stage of the programme

Just Enough staff at each stage – build as you go, to get the right people for the evolving plan

Just Enough information and documentation for the level of decision making and the evolution of the programme

RoT 4. Communication is Crucial. How?

Use fast feedback loops that gather and make sense of adaptive implementation on the ground and strategically direct improvisation

Consciously design communication for diverse audiences (both internal – organization, project team, and external – partners, donors) to secure buy-in

RoT 5. Think about role of (and impact on) Partners/Coalitions. How?

Select partners considering their capacity/scope/appetite for AM

Start the conversation about AM as early as possible: establish it’s in the project before it starts

Resource the burden of participation (money, time, skills) for co-creation/AM

Don’t overstretch the AM capacity of partners

Enable and Encourage partners to learn and adapt along with you

Create safe spaces for feedback, learning and testing solutions

RoT 6. Work with Donors. How?

Find AM allies within donors and keep them involved: relationships, relationships, relationships

Continuous and diverse communication messages for different parts of donors, including showcasing AM successes

Negotiate $ for learning, burden of participation and greater flexibility

Think and Work Politically with donors – understand and link to their needs and framing, help them mitigate risk

RoT 7. Redesign MEL Systems for Accountability and Learning. How?

Adaptive MEL systems match the learning agenda and the capacity to collect and use data, employ mixed methods and ensure participation

Develop outcome indicators for learning and adaptation; accountability does not stop at outcomes

Reward well-managed failure, not poorly managed success

Make room for a mix of indicators: ‘Bedrock’ indicators can be agreed as essential from the outset, then add new or adapted indicators as AM progresses

What do you think?

The post Seven Rules of Thumb for Adaptive Management – what do you think? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

June 26, 2018

Book Review: How to be a Craftivist: the art of Gentle Protest, by Sarah Corbett

Seemed fitting somehow, as the book is all about ‘slow activism’.

Corbett, an award-winning campaigner and lifelong activist whose leftie parents dragged her along on demos from the age of 3, starts with a question: ‘If we want our world to be a more beautiful, kind and fair place, then shouldn’t our activism be more beautiful, kind and fair?’ From that, she develops a mixture of manifesto, memoir and toolkit, based on 15 years of ‘gentle protest’. The result is fascinating, and a bit disturbing too (at least for me).

The starting point was her disenchantment with ‘robot activism’:

‘My response to seeing injustice was to sign lots of petitions, host lots of stalls, go on lots of marches. I would go to lots of meetings, chair some of them, write up the minutes for others, plan events and stunts, write and send press releases.’

Sound familiar? That robo-activism meant she stopped talking or listening to people – a conversation with a punter while getting them to sign your petition just meant less time to get new signatures. It also didn’t work for her – she starts her TED talk picturing herself taking refuge in a music festival toilet, emotionally drained from the effort of confronting total strangers with a petition.

The craftivist toolkit

What she proposes instead is intriguing – the making and giving of gifts to advocacy targets, and of public art to trigger thought and conversation. There’s a burgeoning ‘craftivist movement’ and an awful lot of embroidery. The natural constituency for this approach is a mixture of craft hobbyists, introverts and burnt-out activists.

Her iconic example is Marks and Spencer, which had steadfastly refused to discuss the Living Wage in its UK branches, despite a traditional activist campaign from the likes of ShareAction. In desperation, ShareAction asked Corbett for help. She chose as the target the 14 M&S board members, 5 chief investment officers from the biggest shareholders, and 5 M&S models. Next she recruited a crack squad of embroiderers, bought 24 M&S handkerchiefs (no boycotts here – it’s all positive engagement), and asked each of them to sew a design and message that fitted the character and CV of their designated target (lots of Googling to find out what they wore, interests etc). That insider strategy was complemented by some gentle outsider stuff – small ‘stitch-ins’ outside M&S shops to get conversations going with staff and customers.

The hankies found their target, with board members comparing their messages, craftivists speaking at the M&S

M&S hankies getting ready for the big day

annual shareholder meeting, and then a year of follow up, with more craft, more meetings etc. And boom. M&S adopted the Living Wage. The lessons she draws from this include:

Ownership: this is about the board taking responsibility for the Living Wage, not about ‘us’ being right

Empathy: the 5 hours of stitching to make a bespoke hankie comes with a lot of thinking about the life, interests and constraints of the recipient. That really helps the connection.

Allies: ShareAction and others were involved – craftivism is an addition to other forms of campaigning, not a substitute.

To which I would add – craftivism can break a logjam, where positions have become polarised by ‘them v us’ activism.

Craftivism is hardly a new idea of course – think of the 19th Century ‘Arts and Crafts Movement’ led by William Morris and John Ruskin. When I worked on Chilean human rights in the 1980s, the ‘arpilleras’ – small hand stitched tableaux by groups of Chilean women, showing both everyday scenes, and the repression of General Pinochet’s dictatorship, was one of the most effective ways of arousing empathy among Western publics.

Where Morris had wallpaper to get his message out to a wider audience, today’s craftivist has Facebook and Twitter– a small piece of subversive cross stitching can be hung in a public place, photographed and shared before it is taken down.

A word on my discomfort while reading the book. One source was just my own failings as a human being: I have no colour sense, don’t understand fashion, and am absolutely useless with my hands. Every time Corbett urged the reader to think about these things, I could feel my stress levels rising (the opposite of what is supposed to happen!) To be fair Corbett does not expect her readers to be naturally skillful crafters, is as interested in the art of gentle protest as in the making of craft objects and feels craftivism is open to those who like me are not au fait with the fashion world or at all creative with our hands. But still, I was definitely out of my comfort zone.

A ‘mini banner’

Another concern was that the book is all about taking care of ourselves as activists, and empathising with the Northern targets of our activism – the M&S board and customers. Although the book argues that the slow act of making something creates space for reflecting on the complexity of the issues (e.g. the dilemmas facing M&S directors), it often seems to assume that the rest is all straightforward – the world is made up of good v bad; sweatshops are bad; renewables are good. As a shades of grey kinda guy, that lack of nuance and curiosity alarms me. Stuff like localism, de-growth, voluntary v regulatory approaches have strong arguments on both sides, in my book.

And yet the process of craftivism and its ‘gentle protest’ seems very compatible with the messages of How Change Happens – empathy, reflexivity, humility and understanding the system (or at least parts of it). Overall, it seems an extremely useful addition to the campaign repertoire, especially for the introverts among us (I’ve had my – metaphorical – festival toilet moments too – don’t ask).

Sarah tells me that she is planning to set up a ‘Gentle Protest Lab working with NGOs and funders to test new ways of campaigning’, which sounds amazing – if you want to know more, contact her on sarah[at]craftivist-collective.com or follow her on twitter/instagram (@craftivists).

And here’s her Ted talk

.

The post Book Review: How to be a Craftivist: the art of Gentle Protest, by Sarah Corbett appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

June 25, 2018

Scott Guggenheim defends Community Driven Development

take-no-prisoners critique of the critique of CDD by 3ie (apologies for acronym overload), featured in my recent post. It’s long, but I just couldn’t find places to cut it.

Duncan obviously thrives on controversy, so he’s asked me to adapt my comment on 3ie’s recent evaluation of CDD Projects into a full-fledged blog post.

As someone who is part of a community that is nurturing CDD through some growing pains to see what works and what doesn’t, I like hearing critiques of the approach from which we can learn. Useful evaluations, even the most critical ones, have been those that couple careful interrogation of primary data with a commitment to advancing a broader objective of making public policy more aligned with the everyday problems of poor people in the developing world.

But as someone who either led or was closely involved with several of the projects that 3ie was reviewing, I was pretty dismayed by the selective use of evidence and some of the odder interpretations in this report. Here’s why.

The 3ie paper suffers from three deep flaws. First, it is working from a very small sample of studies, even after inflating the number by combining social funds with CDD and calling them all CDD. This matters because their sample universe combines wildly disparate programs, from huge, multi-year national programs funded through the government’s budget, to relatively small, one-off projects that have little to do with public policies or investment. Their sample’s community grant-making frequency, level and interval times – how often communities actually got funds, how much they receive, and how long afterwards results were measured in the field – also vary by very large amounts, again a problem that matters a lot when trying to draw conclusions about cumulative impacts and outcomes. Second, for a systematic, mixed methods review, there’s a lot of unsystematic, highly selective use of the available evidence. The review has to do this because as soon as we’re past the drama of its headlines, we suddenly find lots of qualifiers attached to each of its generalizations. These include their findings about health and education; distributional and welfare impacts; and the participation of women. The third flaw is the most important from any sort of policy or decision-making perspective, which is that, as Brian Levy commented in a very insightful post that everyone interested in this debate should read, the 3ie review is measuring CDD against “perfection” rather than “what are the realistic alternatives available?”

How comparable are the designs? The problem of constructing a dataset that does not compare apples to oranges is always difficult, but if the 3ie review is going to be making claims about public policy and CDD then it should at least confine its selection to projects that are CDD. Social funds have their pros and cons, but all social funds require that communities send proposals to some central review and approval agencies. CDD programs do not. The 3ie sample also includes projects funded by donors and executed by NGOs, but which operate entirely outside of government, which is undoubtedly fine and important, but then it seems naïve (and distorting) to use these as examples of not having spillovers into other arenas of public action.

How comparable are the designs? The problem of constructing a dataset that does not compare apples to oranges is always difficult, but if the 3ie review is going to be making claims about public policy and CDD then it should at least confine its selection to projects that are CDD. Social funds have their pros and cons, but all social funds require that communities send proposals to some central review and approval agencies. CDD programs do not. The 3ie sample also includes projects funded by donors and executed by NGOs, but which operate entirely outside of government, which is undoubtedly fine and important, but then it seems naïve (and distorting) to use these as examples of not having spillovers into other arenas of public action.

Smushing together such disparate designs has a second problem. Defining the divisions between what the government does and what communities and NGOs do is the key design question for a CDD program. In her 2016 paper comparing Kenyan and Indonesian CDD projects, Jean Ensminger pointed out that CDD programs themselves vary a tremendous amount in ways that surely affect outcomes. This variance is particularly pronounced in almost every one of the areas that 3ie wants to measure: who handles procurement (government or communities); whether audits take place; if there is a working complaints handling mechanism; are facilitators qualified and trained or are they just civil servants tasked with another job? And so on. These distinctions do not appear to be relevant to 3ie. But they make or break a project.

Finally, any evaluation of this sort needs to be very careful with the quality and representativeness of its underlying studies. Andrew Beath’s otherwise excellent study of NSP, for example, which forms the basis for most of 3ie’s conclusions, covered 10 districts in just 6 of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces. Gosztonyi et. al studied NSP in 25 districts of Northeast Afghanistan, using a sample of 5,000 households, reached conclusions diametrically opposed to Beath’s. It’s not that one is right and the other wrong – what is wrong is for 3ie to generalize Beath’s findings to all of NSP. In general, this CDD evaluation literature suffers badly from weak underlying data – short intervals between baseline and endline; one-time measurements rather than long-term, repeated monitoring; “unfortunate events” such as droughts or armed conflict clouding results on irrigation or dispute resolution – in short, all of the problems that explain why good science (and policy) insists on multiple measurements and cross-checks.

Qualifying the headlines — The review has an annoying habit of making big announcements of dramatic findings that it then almost immediately qualifies. For example, “…programs have a weak effect on health outcomes and mostly insignificant effects on education and other welfare outcomes.” But the huge majority of CDD funds go into transport, clean water, and irrigation, not health or education, particularly once social funds are withdrawn from the sample, as they should have been. After boldly declaring that CDD has “no [statistically significant] impacts on health,” 3ie later notes that “the impact of the quality of health facilities is being measured for all treatment communities, including those where no investments were made in health.” (emphasis added)

that it then almost immediately qualifies. For example, “…programs have a weak effect on health outcomes and mostly insignificant effects on education and other welfare outcomes.” But the huge majority of CDD funds go into transport, clean water, and irrigation, not health or education, particularly once social funds are withdrawn from the sample, as they should have been. After boldly declaring that CDD has “no [statistically significant] impacts on health,” 3ie later notes that “the impact of the quality of health facilities is being measured for all treatment communities, including those where no investments were made in health.” (emphasis added)

How big is this average treatment effects issue? Let’s take a look. Afghanistan’s NSP CDD program, for example, covered 38,000 communities all across war-torn Afghanistan. NSP3, the program’s third phase, built 12,930 kms of rural roads, 39,449 clean water sites, 361,523 newly irrigated or rehabilitated hectares of irrigated land – and a grand total of 53 health centers. So what does this report focus on? The health centers. But in any case, why would anyone expect a village infrastructure program to produce changes to health or education, especially over the short term of most evaluation periods? For that to happen communities need teachers and books; nurses and medicines. What CDD offers is a way to build those health and education buildings at half the price, in places where the villagers actually want them to be located, and with virtually all of the spending on construction going to communities instead of to contractors (and officials).

Still on Afghanistan, 3ie writes that “An impact evaluation of the second phase of NSP in Afghanistan found mixed effects of the program on gender norms. Men’s acceptance of women in leadership in local and national levels had increased, as had women’s participation in local governance (emphasis added).” That’s a pretty big deal, not a “mixed effect!” 3ie then does go on to qualify this by saying they were referring to men’s attitudes towards women, but it’s certainly quite a trick to conclude that men now accepting women in leadership is not a change in men’s attitude towards women’s social roles.

The review’s claim that “CDD programmes have not had an overall impact on economic outcomes” – they only exempt Philippines Kalahi CIDSS from this claim – is simply put, false. The independent evaluation of Indonesia’s nationwide PNPM programs found consumption gains of 11 percentage points for the poorest. Sierra Leone’s GoBifo found gains in both household assets and market activity. BRA-KDP (Aceh) found an 11% decline in the share of villagers classified by village heads as poor, a doubling of land use for conflict victims and improvements in welfare (Adrian Morel, “Using CDD for Post-conflict reintegration: Lessons from the impact evaluation of the BRA-KDP program in Aceh,” Presentation to the Development Impact Evaluation Initiative (DIME), Dubai, June 1, 2010.).

The Atos cost-benefit study of Afghanistan’s NSP found that beneficiaries of land with improved irrigation reported crop yield increases of over 11 percent per harvest for their main crop, wheat, along with improvements in food availability for home consumption, while those who built roads found reductions in travel costs of 34 percent for goods, with an increase in the volume of goods transported of nine percent — and this in the middle of a rising conflict that was disrupting nearly all other forms of service delivery. It’s hard to see how 3ie can conclude from these independently measured findings that CDD has “an insignificant effect on…. welfare indicators.” In fact, K. Casey’s 2017 review of seven CDD operations that used randomized evaluation designs – including several of the same ones reviewed by 3ie – found improvements to household asset levels, employment, and market activity.

What are the alternative comparators? The third issue is that to be useful for policy makers, the most useful evaluation would have been to compare CDD programs against the next best available alternative. But for this kind of real-life assessment, the problem isn’t with what CDD measures, but the fact that such studies do not exist for the alternative options that 3ie is referring to. Saying that 57% of villagers knowing when the project meetings were taking place in the 9 CDD projects for which there is data illustrates “limited community” participation would mean something if we knew what the rates were for standard line projects – in fact, in the pre-KDP ethnographic studies we did in Indonesia, those numbers would have been stupendous.

What are the alternative comparators? The third issue is that to be useful for policy makers, the most useful evaluation would have been to compare CDD programs against the next best available alternative. But for this kind of real-life assessment, the problem isn’t with what CDD measures, but the fact that such studies do not exist for the alternative options that 3ie is referring to. Saying that 57% of villagers knowing when the project meetings were taking place in the 9 CDD projects for which there is data illustrates “limited community” participation would mean something if we knew what the rates were for standard line projects – in fact, in the pre-KDP ethnographic studies we did in Indonesia, those numbers would have been stupendous.

In any case, if you can reduce unit costs in a country by 44%, as 3ie itself reports for the nationwide Indonesia KDP program, we don’t need another million-dollar, multi-year RCT to conclude that this is already something worth doing. This relative efficiency matters a lot when poor countries are trying to cover large numbers of poor and isolated areas. In several of the areas of their findings, there is available evidence on what the “next best” or “without” alternative looks like. The reason why Indonesia’s PNPM’s road and water projects cost so much less than local government ones is because there is less corruption and better oversight. The roads actually got built, which is why when Indonesia began requiring local government contributions after its 2004 decentralization, 398 of 400 districts paid in a matching grant from their own budgets. Getting women’s participation in public village meetings up to 30% in Afghanistan is surely not good enough, but it’s a lot better than standard development or traditional meetings, where it is at best less than 5% and in fact in most places, it is zero. And of course, it would be great if the women always spoke up more or had more decisive roles in each and every meeting, but you can be sure that their voices will remain at zero if they aren’t even in the room.

Susan and I tried to make three points in our own paper on CDD. First, CDD gives policy makers an important,  useful new way to build large amounts of useful, small-scale productive infrastructure. It also gives poor communities some voice in how development funds are used. Second, CDD programs are not a homogenous category and for any evaluation, understanding the design differences between them is essential. And third, CDD works best when it is part of a broader strategy that can complement other programs and policy reforms as well as broader social changes taking place in society.

useful new way to build large amounts of useful, small-scale productive infrastructure. It also gives poor communities some voice in how development funds are used. Second, CDD programs are not a homogenous category and for any evaluation, understanding the design differences between them is essential. And third, CDD works best when it is part of a broader strategy that can complement other programs and policy reforms as well as broader social changes taking place in society.

We also point to CDD’s limitations. Communities can build schools and clinics, but they can’t train and hire doctors and nurses. For that we will always need health and education programmes. And I don’t know of any serious CDD program practitioner who ever believed that handing out one or at two rounds of grants for infrastructure would translate into the magical creation of missing social capital, ethnic harmony, or a social movement – all of those require a different kind of political and social reform. In yet another study left out of the 3ie review, Woolcock, Barron and Diprose found “Ethnic, religious and class relations in NTT have improved since KDP was introduced, and these changes are greater in treatment than control areas….Further, improvements in the quality of group relations grow larger over time. Villages that have had KDP for four years show, in general, greater improvements than those that have had the program for shorter periods.”

CDD programs are also not by themselves the kind of job-creating, transformative activities – urbanization, industrialization, higher education, better health – that poor people increasingly need and deserve. But they can help poor people gain access to those things, and on a scale that reaches millions.

My main feeling after finishing the 3ie review was one of depression more than anything else. How is it even possible that three sets of reviewers, using more or less the same studies and all produced within a year of each other, can reach such disparate conclusions? The 3ie report faults CDD for not doing what it never claimed to do, cherry picks the qualitative literature, and proposes instead to move procurement to local governments rather than communities, despite openly saying they base this entire conclusion on just one 2004 World Bank study of four countries’ social funds. This is the kind of advice we’re giving to governments and activists in developing countries?

What is so brilliant about Brian Levy’s discussion is that he nails a lot of what is really at stake here, which is power, influence, and money. CDD’s founding principle is that for a lot of local-level development work, developing countries don’t need much of that disempowering apparatus of big consultancies, complex procurement rules, and rigidly defined logframes guiding their every move. Nor do they need to replicate donor agencies’ deep and often vicious sectoral divisions. But what lies at the heart of CDD is the importance of accountability for service delivery. CDD began as an anomaly, but by now the idea that working through partnerships and financial transfers that give more voice to local choices can be managed, and managed well, by a broad range of developing country governments is spreading to contexts where more standard approaches have simply given up. Not perfectly, and not without failures, but it is happening and it is improving. So it’s no surprise that the traditionalists have started to push back. Perhaps it is time to step back from a meta-review of developing country’s projects and instead do some meta-reviews of the reviewers.

The post Scott Guggenheim defends Community Driven Development appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

June 24, 2018

Links I Liked

Links I Liked

Now this is what I call a political ad. Why am I running for Congress against a Tea Party Republican in Texas? It all started with a door. MJ Hegar sets out her stall:

The human price of stocking supermarket shelves. Tim Gore introduces a big new Oxfam campaign

‘That tearing sound you can hear is the veil that normally partitions economics from society and politics’. Great long read from Aditya Chakrabortty on an experiment in popular economics

‘Countries that even just barely qualified for the African Cup of Nations experienced significantly less conflict in the following six months’. The connection between soccer and nation-building is a much-neglected issue.

Which one is Fox News, which North Korean state TV?

The case against branding aid in fragile states

‘a single global poverty line cannot do the job that the World Bank, since the first poverty report in 1990, claimed it could’. Branko Milanovic unpacks the (many) implications of Bob Allen’s work on poverty lines

Naomi Hossain: fuel and energy riots are common around the world, have barely been studied, and are a potential roadblock to tackling climate change by cutting fossil fuel subsidies.

Congrats to Uganda’s Brian Gitta, the young entrepreneur who just won the Royal Academy of Engineering’s Africa prize for inventing a bloodless malaria test

Powerful ICRC video on what happens when, around the world, hospitals, medical personnel and aid workers come under attack.

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

June 21, 2018

The lure of the complicated: systems thinking, data and the need to stay complex

lightbulbs flash on in your head – either insights or the onset of a migraine.

Earlier this week I spent an afternoon at the Gates Foundation in London, discussing what systems diagnostics can offer to groups like the World Bank, DFID and RISE, a big research programme on improving the quality of education worldwide.

We kicked off with an education systems guru, Luis Crouch, describing the 3 things he thinks characterize a system:

The objects/actors in it – wolves, deer and tree saplings

the feedback loops between them – wolves eat deer; deer eat saplings.

The emergent properties that the system produces. Not intentional on part of any one actor.

In his view, most diagnostics of education performance spend a lot of time enumerating and assessing the individual actors (teachers, principals, training institutions etc), but don’t think much about the feedback loops between them. Also, they mainly look at purposive properties – did the programme achieve the intended outcome – not the emergent properties that no-one intended.

We then moved on to Jaime Saavedra, who now leads the Education Global Practice at the World Bank, but from 2013-16 was Peru’s Education Minister. His reflections on his reform efforts there were fascinating.

Firstly (in passing) a ringing endorsement for league tables. He talked of the ‘PISA shock’ from Peru’s poor performance in the global PISA education ranking. ‘‘PISA influences countries: I don’t want to look bad’.

But what really gets him fired up is data. ‘We had a huge obsession with data, throwing information into the system. There were dashboards for absolutely everything. We tracked the life of the textbook from printshop to student. Ditto with all the inputs.’

On the basis of data analysis and brainstorming, the Ministry identified poor quality teaching, pedagogy and (lack of) school leadership as the main things they needed to tackle.

Lant Pritchett chipped in (very excited that he’s going to be in the UK for a while, after leaving Harvard) and said education reformers need to come up with something like the Growth Diagnostics that he developed with Dani Rodrik, Ricardo Hausman and Andrés Velasco. Education reform is now where growth promotion was, circa 2005: ‘the problem was that every time the World Bank did a country report, it would come up with a checklist of 60 things to fix, and no country could deal with all of them. We need a structured way to identify the binding constraints to learning, and tackle those first’.

Ping! On goes a lightbulb. These two are talking about a complicated system, not a complex one. The distinction is crucial. Complicated is like sending a rocket to the moon – a difficult problem, but one that can be broken down into its component parts, ‘solved’ with data and smarts, and reassembled into a successful solution. That’s what Jaime and Lant were describing.

Ping! On goes a lightbulb. These two are talking about a complicated system, not a complex one. The distinction is crucial. Complicated is like sending a rocket to the moon – a difficult problem, but one that can be broken down into its component parts, ‘solved’ with data and smarts, and reassembled into a successful solution. That’s what Jaime and Lant were describing.

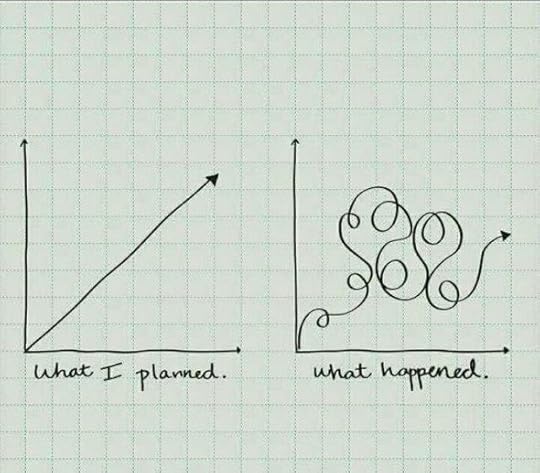

In contrast, a complex problem is more like raising a child – it’s all about antennae, judgement, guesswork, collaboration, trying stuff out and then realizing quickly when it’s not working. Data is useful, but not as central. ‘Lessons’ from raising one child are likely not to transferable to the next. And if you break a complex system down into its component parts (please don’t try this with your child) you won’t get much insight into how all the different feedback loops produce the ‘emergent properties’ of the whole.

The act of being in charge, of trying to get stuff done, drags you from the complex into the complicated quadrant. The data offers you a handle, you need to set priorities, and before you know it, you are doing the Growth Diagnostics thing and breaking up the system into its parts. That’s probably inevitable, and not such a bad way to proceed compared to, for example, just making stuff up. But it loses touch with those elements that are complex, and likely to mess up your complicated plan.

So what countervailing forces can push decision makers to keep at least one foot in the complex camp? The two obvious ones are politics and MEL: politics – what Jaime knows will fly and won’t – is all about judgement and spotting emergent patterns and opportunities; Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning, done in real time, will tell you when your attempt to disaggregate has backfired, and unintended consequences are springing up like mushrooms in the night.

Any issue is likely to have elements of both complicated and complex, so the question is how to ensure a balance of  both.

both.

Cue second light bulb. One of the things I have been failing to do is distinguish clearly between system, problem and solution. On the same topic, they may be in different quadrants – eg health, whether individual or societal, is definitely a complex system, but how to establish healthcare clinics in every corner of the county can be a complicated problem, while vaccinations may be a simple solution.

Thoughts?

The post The lure of the complicated: systems thinking, data and the need to stay complex appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers