Duncan Green's Blog, page 95

May 23, 2018

Gender, disability and displacement: Reflections from research on Syrian refugees in Jordan

This guest post is by

Bushra Rehman (right)

, a Research Officer with the

Humanitarian Academy for Development

, which  is the research and training arm of

Islamic Relief Worldwide

. The post is based on her

prize-winning Masters dissertation

.

is the research and training arm of

Islamic Relief Worldwide

. The post is based on her

prize-winning Masters dissertation

.

It is mid-afternoon in Jordan and the weather is stiflingly hot. I arrive at a derelict building in Irbid, a city located 20 km south of the Syrian border, where I’m introduced to a Syrian refugee. She welcomes me into her apartment. Upon entering her home, I’m introduced to her sister, Dina (not her real name), a young woman whose life was transformed when she was paralysed by a gunshot wound. With a waning sense of optimism, she describes how her life changed from being a woman, like thousands of other Syrian women, to an even more disenfranchised member of society: female, disabled and displaced.

8 months later, I’m back in Jordan, at a grim tower block building in Amman, a city known for its mountainous terrain and multi-storey residential buildings, which are acutely inaccessible for people with mobility impairments. I’m introduced to a 60 year old Syrian refugee, who welcomes me into her fourth storey home. There’s no lift so I climb up the stairs, with some difficulty, to her apartment where I’m introduced to her children – three daughters and three sons, all of whom have physical and intellectual impairments. A range of environmental barriers in their local community, such as steep hills and staircases, restrict their capacity to move around, to easily access humanitarian services, to form communal relationships and as such, reinforce the sense of isolation that refugees are already facing.

These are but two examples; I am privileged to have met many Syrian refugees, of all abilities and ages, and to have had the briefest of glimpses into their journeys. These interactions showed how pre-existing vulnerabilities, such as those associated with gender, disability and displacementoften combine to deepen poverty in refugee settings. The female disabled refugees I spoke to clearly expressed how they felt secluded, dependent and lacked opportunities to access education or livelihoods in Jordan.

These women face discrimination not only because of the negative social attitudes and stigma attached to disability, but also because of the pernicious inequalities associated with being a woman, adding further susceptibility to violence and discrimination which inhibits their access to education, work, community spaces and activities. At the same time, they felt as though the “de-gendering” effects of disability prevented them from fulfilling socially-important gender roles, such as being a mother or a wife. Indeed, historically, disabled women have been subjected to cultural stereotypes which view them as asexual, unfit to reproduce and dependent.

I vividly remember a female Syrian refugee with paraplegia complaining that her marital prospects were extremely limited compared to her brother, with the same condition. In a culture where the prospect for marriage carries monumental value, she felt a great sense of deprivation. In addition to this, the insecurity associated with escaping conflict and finding herself in a new environment as a refugee with weak support structures and limited access to resources added to her disadvantage. This means that she – and other disabled female refugees like her – are discriminated against on several grounds simultaneously, causing what is often referred to as a “triple burden”: being a refugee, being a woman and being disabled.

I vividly remember a female Syrian refugee with paraplegia complaining that her marital prospects were extremely limited compared to her brother, with the same condition. In a culture where the prospect for marriage carries monumental value, she felt a great sense of deprivation. In addition to this, the insecurity associated with escaping conflict and finding herself in a new environment as a refugee with weak support structures and limited access to resources added to her disadvantage. This means that she – and other disabled female refugees like her – are discriminated against on several grounds simultaneously, causing what is often referred to as a “triple burden”: being a refugee, being a woman and being disabled.

At first glance, it would seem that disabled male refugees would be at least slightly better off than their female counterparts. However, I quickly learnt that the intersection between disability and gender has a unique impact on men, as well as women, in refugee settings. For example, an aid worker in Jordan described a case to me in which a Syrian man suffering from psychological trauma complained that his “manhood had been eroded” after a barrel bombing caused permanent injuries to his genitals and legs. Being unable to conform to culturally-mandated notions of masculinity has an incalculable effect on the self-esteem and vulnerability of Syrian men, further intensified by notions of refugees as “weak” and “dependent”. In addition, I’ve spoken to male refugees who say that the widespread perception that only disabled female refugees are vulnerable left them invisible to aid agencies – abandoned by the humanitarian system. It’s important to emphasise that the intersection of gender, disability and displacement can have a marginalising impact on both men and women.

Ultimately, all this suggests that if we are sincerely committed to ‘Leaving No One Behind’, it is imperative that we understand the diversity of experiences of the most vulnerable groups in society. We must also appreciate that when applying an intersectionality lens to our work on a practical level, we must recognise that the relationship between disability, gender and displacement is complex, multifaceted and the ways in which power is distributed can change across contexts and situations. Humanitarian actors must, therefore, step away from narrow definitions of gender, disability and displacement and work towards more rigorously planned humanitarian responses that appreciate each aspect of human difference.

Nevertheless, even though ‘intersectionality’ cautions us against reductionism, we must be careful not to treat all disabled male and disabled female refugees as passive victims with no sense of agency. Within the same demographic, individual experiences differ: Dua, a Syrian refugee told me that after escaping Syria and facing  complications that affected her mobility, she made a conscious decision to change her life by volunteering with local NGOs that support other disabled Syrian refugees in Jordan:

complications that affected her mobility, she made a conscious decision to change her life by volunteering with local NGOs that support other disabled Syrian refugees in Jordan:

“One of the most debilitating effects of disability is people misjudging me. But when they see that I’m active and making a difference, their opinion changes”.

Dua taught me about more than just the importance of intersections between gender, disability and displacement. She taught me about the need to highlight personal narratives that avoid inadvertently stripping away individuality and history. She taught me about the importance of having meaningful relationships with refugees, rather than patronising and superficial ones. And she taught me that every refugee, regardless of age, ability and gender, has stories that are vivid, elaborate and complex, populated with struggles and victories. I returned dazzled by the wisdom and strength of disabled refugees in their struggle to forge a better future, despite all the barriers that society places in their path.

Further Reading: See this new ICAI review of DFID’s approach to disability

May 22, 2018

5 Lessons from Working with Businesses to Support Workers around the World

This piece appeared on ETI’s May ‘Leadership Series’ blog yesterday

I was present at the birth of ETI 20 years ago. Recently installed at the Catholic aid agency, CAFOD, I was sent off to discuss an obscure initiative to set up a ‘Monitoring and Verification Working Group’ for companies trying to assess labour standards in their supply chains.

I was impressed to find a lot of corporate heavyweights there, lured by the silver-tongued Simon Zadek, who seemed able to captivate companies and NGOs alike. We quickly dropped the awful name, added trade unions to the mix, and the ETI was born.

In the UK, the ETI marked a sea change in the dialogue between companies and civil society. Previously, NGOs tactics were solidly outsider, criticising ‘big business’ for its many failings.

My own research for CAFOD had already caused me to question this narrative – the queues of women seeking jobs outside Bangladesh’s garment factories made sure of that, with their insistence that (while many complained of abusive treatment in the factories), earning a wage had won them new respect within the household.

With ETI, we found ourselves sitting together with the buyers of those garments, trying to help them address the complex issues of modern production networks (it took C&A three years just to find out where its clothes were being produced, unravelling the extraordinary complexities of its supply chains).

I sat on ETI’s board for the next few years and the lessons I learned there have stayed with me ever since.

Lesson one – combining insider and outsider tactics often gets the best results

After one board meeting, a supermarket rep sidled up to me and said, ‘”Duncan, could the NGOs campaign against us a bit more? My Board is threatening to cut the budget for CSR.”

After one board meeting, a supermarket rep sidled up to me and said, ‘”Duncan, could the NGOs campaign against us a bit more? My Board is threatening to cut the budget for CSR.”

I’ve used that example ever since as an illustration of the false dichotomy between outsider campaigning and insider advocacy. A combination of the two creates the pressure for action, and the cooperation that’s needed to find answers to tricky problems.

Lesson two – ensure diversity

Diversity in what are now called ‘multi-stakeholder initiatives’ is hard work, but in the long term it produces more creativity and results.

The ETI board was a study in contrasting cultures. Caricaturing massively, the corporates were ambitious, can-do pragmatists, occasionally dazzling us with statements like “I’ve been asked what would it take to make Sainsburys 100% Fairtrade.”

The unions took the long view – this was about pursuing long term bargaining rights and freedom of association, not jumping onto every passing bandwagon. And they really didn’t like the NGOs, who they saw (not without some justification) as a bunch of middle class intruders into the ancestral struggle between capital and labour.

The trouble was the companies were only there because of the NGOs, so they had to put up with us!

Over time, we got to know each other’s foibles (the guy from the ITUC was a fish and chips enthusiast), and we built trust over meals and pints.

Lesson three – empathise

Empathy + power analysis means you have to build the confidence and emotional intelligence to engage with people as individuals, while still recognizing that their views and constraints are shaped by their personal histories and the organizations they work for.

as individuals, while still recognizing that their views and constraints are shaped by their personal histories and the organizations they work for.

As a campaigner, it takes time to see the human being behind the label: I remember trying to recruit a ‘suit’ from a major department store to join ETI. I deployed my half-understood business jargon – this is about reputational risk, staff retention, yadda yadda. ”I don’t care about all that,” he replied, “I want to make the world better for my children.” Oops.

I also saw how the companies navigated the difficult combination of cooperation and rivalry – after all, we’re talking cutthroat competition between major supermarkets here. Even so, they came together in working groups, recruited new members, talked each other’s language, and understood each other’s challenges.

Lesson four – the messenger matters

When it comes to influencing, the messenger often matters. At least as much as the message. Corporates are far more likely to listen to other corporates, rather than finger-wagging NGOs or class warrior trade unions.

Some of the really interesting stuff happened after I moved on. In 2013, I watched the swift and effective response to Bangladesh’s Rana Plaza disaster. Companies, unions and NGOs were able to draw on their pre-established relationships and trust, pick up the phone and address local and international demands for action.

Within weeks a Fire and Safety Accord was agreed, which was signed by over 200 apparel brands (retailers and importers from over 20 countries in Europe, North America, Asia and Australia), two global trade unions and eight Bangladesh trade unions, as well as four NGO witnesses.

It may not be a coincidence that key actors in making a success of the Accord had previously been active in ETI – Dan Rees was head of ILO Better Work (former ETI director) and Alan Roberts the Accord’s first director (former ETI chair). They understood the landscape like no others.

While undoubtedly more needs to be done, there have been real improvements in the factories of Dhaka, which brings us to…..

Lesson five – seize opportunities

Rana Plaza

Shocks and crises can be windows of opportunity for progressive change. But, as Rana Plaza showed, only if the relationships are already in place that allow people and players to work together to respond.

Twenty years on from my time at ETI, I believe there is lots to celebrate. Progressive companies at least, realise that addressing and upholding the human rights of workers within their supply chains is both commercially important and an ethical imperative. They also realise that there are practical ways in which they can use their influence to Improve the lives of millions of workers around the world.

Yet, despite the five lessons – and the progress – I work for an NGO, and our role is to be permanently dissatisfied. I therefore always ask, where next? Here’s a couple of thoughts:

First, we discussed a Living Wagefrom the earliest days. It’s even in the ETI code of conduct, but progress in turning it into a reality has been minimal.

Second, gender equality is about much more than just funding a few projects or creating jobs for women: companies need to collect disaggregated data and really take the issues seriously.

Much more progress is needed on these issues and I look forward to seeing it happen.

(I should add that I was pleased to see that ETI has started working with its company members and the University of Manchester on mapping women’s rights initiatives in supply chains and on ensuring greater gender equality in the future.)

So a huge thanks to the ETI, and best of luck for the next 20 years.

May 21, 2018

Can ‘Doing Development Differently’ only succeed if aid donors stay away from it?

Another day, another seminar on Adaptive Management/Doing Development Differently/Thinking and Working

Optimistic

Politically (let’s save words by just calling the whole thing DDD). This one was held under the Chatham House Rule, so no names or institutions. There was an interesting mix of academics and contractors – private companies who increasingly run the big contracts for DFID and other donors, and a few lightbulb moments in the discussion:

Firstly, how come DDD has become such a Thing when it seems to swim against the institutional tides of the aid business? It emphasizes systems thinking, uncertainty, learning by doing/failing and giving priority to local knowledge – that is, to put it mildly, a poor fit with the aid biz’ preference for control, logframes, risk minimization, and predictable, tangible results. At first it seemed like some kind of quixotic backlash against the forces of evil, but it seems to be getting traction all over the place – any theories as to why/how that kind of mainstreaming has happened?

One aid trend which on the face of it seems to run counter to DDD is the shift to outsourcing – DFID and others run multi-million pound contracts through a plethora of largely faceless management consultants and contractors, like Adam Smith International, who periodically get taken to task for profit gouging, poor performance or dodgy dealings. Not all management consultants are the same, but at the gold digger end of the spectrum are some companies who only want to maximise profits and minimise costs – they seem ill suited to the world of DDD, with its focus on uncertainty, deep curiosity, suspicion of blueprints, preference for experimentation, accepting and learning from failure etc. To be fair, at the other end of the spectrum are some contractors who do not seem solely motivated by $, and who are doing some serious work in the DDD area – Palladium and OPM are two examples.

On the Fence

But a more fundamental challenge to the role of aid in DDD came from some of the Harvard crew (oops, there goes Chatham House. Sorry), who work directly with a range of governments to help pursue ‘Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation’. One speaker described its core principle as ‘always give the work back to government – it’s a coaching role, not us doing the work’.

In that model, academics may fly in to help, but they do so at the invitation of the government, and ideally, the government funds and owns the work. Riffing on my much-overused analogy of projects as linear cake recipes, the speaker said ‘PDIA accepts limits to how much we can understand about the system, which is why the cake has to be in hands of the people’. Move over Marie Antoinette.

If you introduce donors into that arrangement, ownership is diluted, and donor priorities and processes take over – the donors provide the recipe, and at best, the government gets to decorate the cake. A nice line from a TWP person: ‘Thinking politically comes naturally to many (in government, civil society etc); working politically less so. People breathe politics, then put it to one side when they talk to funders.’ See this great paper by Graham Teskey and Lavina Tyrrel for more on that.

One example: the vast majority of donor activity assumes the problem is largely known in advance – aid is siloed into education, health, infrastructure, governance etc, with calls from donors for different aid agencies/consultancies to bid for contracts. But PDIA works on the basis that you initially spend a lot of time helping local players clarify and understand the roots of a given problem, which may not look at all like what you start out with (you think the problem is poor quality education, but it turns out to be dodgy electricity or roads, or poor health among kids). Yet Aid doesn’t do agnosticism and finds it hard to hop between siloes. Tricky.

An even more fundamental challenge was raised in terms of systems thinking. The underlying model is of an external intervention into the status quo – the intervention is seen as external to the system that is being intervened in. That is questionable – donors may be only a minor perturbation of the system, in which case seeing them as separate may be a good approximation, but as soon as they start to have impact, they become part of it. Quite apart from the politics of meddling, there seems to be a fundamental contradiction in external interveners trying to understand/influence endogenous change as a separate thing from themselves.

So a purist might say ‘keep external roles to a minimum, aid donors stay away, and let local actors lead’. That has two

Not Good

massive flaws:

Yes, some governments can fund some of the PDIA style work, but many can’t – if you buy the argument that aid is still needed in many countries, then is there a way to politically sterilize it, taking it away from all the dictates of donors? One option might be to channel it through third parties, like the UN or World Bank, but they are hardly politics-free either.

PDIA-style approaches start with being invited in by someone senior in government, who wants to sort out a problem. But what about governments that don’t want to reform? Can donors tiptoe around the accusations of meddling in internal affairs and support critics, opponents and future leaders with different views? Is that where DDD meets civil society support?

In other words, a good seminar, that left me with lots of questions to ponder.

May 20, 2018

Links I Liked

The 7 deadly sins – online version ht Sony Kapoor.

Steven Pinker’s Ideas About Progress Are Fatally Flawed. These Eight Graphs Show Why.

There are 7 universal moral rules: love your family, help your group, return favours, be brave, defer to authority, be fair, respect others’ property. These are the same across all cultures, according to an analysis of ethics from 60 societies (600,000 words from over 600 sources). Ht Paul Kirby.

Israel has now killed more than 90 Palestinians in the past six weeks for approaching the fence it placed around Gaza, surpassing the total number of East Germans shot and killed for trying to scale the Berlin Wall from 1961 to 1989.

Over recent decades, the notion of rights has expanded to include ever more issues. Is it now time to include other species too? I was struck by this argument in Sapiens too.

‘The argumentative old git is back.’ Great to see George Monbiot back on his feet and over-sharing.

Indian girls receive less education, have poorer nutrition and get less medical attention than boys. Result? Discrimination kills 230,000 girls under five in India each year.

David Satterthwaite asks ‘Is urban development just too complicated for aid organizations?’

Yes, neoliberalism is a thing. Don’t let economists tell you otherwise. Well written and fairly convincing – what do people think?

May 17, 2018

Book Review: How to Rig an Election, by Nic Cheeseman and Brian Klaas

A lot of the power of a successful book is in its ‘big idea’ – the overall frame that endures long after the detailed  arguments have faded in the memory. On that basis, ‘How to Rig an Election’ looks set to do very well indeed.

arguments have faded in the memory. On that basis, ‘How to Rig an Election’ looks set to do very well indeed.

The authors are both top political scientists (Cheeseman at Birmingham and Klaas at LSE) but also good writers – the prose is crisp and wonderfully free of political science gibberish jargon – who know the value of a great anecdote (no shortage of those on a subject like this).

The starting point is a paradox ‘there are more elections than ever before, and yet the world is becoming less democratic’. The basis for these claims includes interviews with more than 500 elite figures in 11 countries, backed up by a global data set of all elections held since 1960. Their focus is on goldilocks states – neither pure authoritarian, nor ‘pure democratic’ (if such places exist), but lying on a spectrum from dominant authoritarian (Russia, Rwanda) to competitive authoritarian (Kenya, Ukraine), which together they call ‘counterfeit democracies’ masquerading as the real thing. Before you reach for your decolonisation shotgun, they also include lots of examples from the chequered pasts and presents of countries like the US (Trump) or UK (rotten boroughs).

What they find is that rigging elections is a really good strategy for autocrats – much better than simply doing an Idi Amin and trying to kill everyone who opposes you. Rigging elections ‘typically enables embattled governments to secure access to valuable economic resources like foreign aid, while reinvigorating the ruling party and – in many cases – dividing the opposition…. 30 years ago, the main aim of the average dictator was to avoid holding elections; today it is to avoid losing them.’

Perhaps the most useful aspect of the book is their identification of a six stage ‘menu of manipulation’: Gerrymandering; vote buying; repression; hacking the election; stuffing the ballot box and finally, playing the international community. A really handy checklist for future observers, whether international or armchair. Each gets a chapter, stuffed with examples.

Here’s how it works:

Gerrymandering made simple

‘By gerrymandering electoral boundaries and excluding rival leaders who threaten to gain momentum, incumbents can give themselves a significant head start before the campaign has even begun. This advantage can then be consolidated by manipulating state access to resources to distribute patronage and gifts, outspending opposition parties. At the same time, incumbents may digitally manipulate the media and electoral process.

When these tactics prove to be insufficient, counterfeit democrats have two riskier options: political violence to intimidate opponents or, if that doesn’t work, the last resort for the recalcitrant authoritarian is ballot-box stuffing.

And while counterfeit democrats are busy rigging the election, they are also often running a parallel deception campaign internationally [to] dupe observers or foreign governments into endorsing a rigged election.’

Which leaders go in for election rigging?

‘Leaders are most likely to try and stay in power when they believe that their presence is essential to maintain political stability; in cases when they are less committed to plural politics; when they have engaged in high-level corruption and/or human rights abuses; when they lack trust in rival leaders and political institutions; when they have been in power for a longer period of time; and when they control geostrategically important states with natural resources, effective security forces, weak institutions and high levels of distrust.’

The level of rigging seems to be much higher for presidents than for common and garden politicians: ‘in some African countries roughly 50% of legislators do not win re-election, even in countries where the president never loses’. Competitivity lower down the food chain allows ruling parties to renew themselves, bring in new talent and get rid of the deadwood, while the Big Man stays on the presidential throne.

My overall conclusions from the book?

Autocrats have to be really dumb to lose elections, given all the advantages of incumbency. ‘Authoritarians are

adaptable’ and getting better at rigging, including doing a lot more of it well ahead of election day.

adaptable’ and getting better at rigging, including doing a lot more of it well ahead of election day.This makes fixing it really hard – there’s a balloon effect whereby if you manage to clamp down on one of the six rigging mechanisms (eg by using tech to monitor polling stations), governments can simply shift to one of the others.

And it’s getting harder – the rise of both China and Donald Trump is making any interest in procedural democracy look rather old fashioned and irrelevant.

Depressing stuff, the authors do their best to end on a positive, but their ‘what is to be done?’ chapter is unfortunately the least convincing of the book. As one depressed election observer in Zimbabwe told Cheeseman ‘we are always fighting the last election, but the regime is always looking ahead to the next.’ The authors end on a rhetorical note:

‘Autocrats have learned that it is easier to stay in power by rigging elections than by not holding them at all. Right now, those that rig elections are not only outfoxing their own people, but also international observers. Unless we learn to identify these strategies and deter or address them, then election quality will continue to decline. If we care about democracy, we must act now.’

True that, and this book is a great start. We have the diagnosis, and next we need more ideas on who can fix it, and how.

May 16, 2018

Which is better: a guaranteed job or a guaranteed income?

Guest post from Eleanor Chowns of Bath University

Martin Ravallion (former Chief Economist of the World Bank, now at CGD) published a useful paper this week asking exactly this question. As he says, there’s no simple answer – which is why the question is so interesting.

Both ‘the right to work’ and ‘the right to income’ aim to secure a more fundamental right: freedom from poverty. Workfare has a long history, notably in India, where the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) guarantees (in theory) up to 100 days work per year, paid at a minimum wage, to anyone who requests it.

Cash transfers (often with conditions) have expanded enormously in recent years, while the hot topic of Universal Basic Income (UBI) has advocates across the political spectrum. Which of these approaches is most cost-effective? Ravallion sets out the arguments clearly.

Proponents of workfare argue that it solves unemployment, and helps push up the minimum wage. Workfare is self-targeting: richer people simply won’t bother to do it, so it’s good at reaching the very poor. And in theory these schemes can build productive assets (roads, drainage, irrigation) that help communities in the long term.

NREGA in action

But workfare has costs, too, including supervision of worksites and provision of materials. Participants face opportunity costs, so the workfare income isn’t fully additional. Monotonous manual labour is not much fun for anyone, and not much use for those with illness or disability. And Ravallion gives pages of detail on the problems with implementation, including work rationing and corruption.

So, does it work? Not nearly as well as it should. NREGA reduced poverty by only 1 percentage point in Bihar, not the 14-point reduction predicted in theory. Why? Because NREGA failed to give work to everyone who needed it, failed to pay them on time, and was costly to implement. A UBI would have been equally cost-effective in reducing poverty, without imposing a work requirement.

What about cash transfers, then? Ravallion explains the two approaches to guaranteeing a minimum income: ‘perfect targeting’, and UBI. Perfect targeting gives anyone below the poverty line a ‘top-up’ of exactly the amount needed to bring them out of poverty. UBI, in contrast, gives everyone the same regardless of their income.

On the face of it, the ‘top-up’ approach would be far less costly. One estimate suggests it would cost only $80bn per year to eliminate poverty in this way – about half the global aid budget. So what are we waiting for?

Ravallion explains four reasons why perfect targeting doesn’t work: 1) information constraints mean that in practice

Pension day in Tanzania

it’s impossible to identify who should get what: one study showed that even using the best available data, 75% of the poor would stay poor; 2) targeting may undermine wider public support for transfers, leaving the poor with ‘a larger share of a smaller pie’; 3) perfect targeting implies that poor recipients would be taxed at 100% on any additional income they earned; and 4) targeted transfers can create stigma.

In contrast, UBI would be administratively simple and cheap, though usually much more expensive overall. However, in places where a large proportion of people are poor, the costs of a universal approach might still be less than the costs of targeting.

A mid-way approach is what Ravallion calls ‘state-contingent transfers’ (aka ‘categorical targeting’) i.e. universal transfers to particular categories of people, such as ‘children’ or ‘over-60s’. This is where the paper ends – and where I think the advocacy needs to begin.

Because, in the end, evidence doesn’t drive policy. It’s all about the politics.

There’s clearly plenty of scope to improve the effectiveness of workfare schemes like NREGA. But there’s even more scope to expand universal categorical income guarantees, like pensions and child benefit. Who could really object to ensuring every child and every senior has a dollar a day to ensure a decent basic quality of life?

Of course, guaranteeing income (or employment) won’t solve all development challenges. Building good health and education systems requires collective public investment. But while it might be both impractical and relatively ineffective to ‘just give’ half the global aid budget to the poor, there’s surely scope to give more than we do at the moment. Maybe we need another ODI High Level Panel to look at the role of cash in development aid?

I do wonder sometimes why we don’t hear more about ‘the right to income’ from NGOs. A cynic might make the ‘turkeys and Christmas’ point: if more aid went directly to the poor, there’d be less to fund NGO projects. Or maybe we’re all just a little too hesitant in these aid-hostile times? But ‘more cash for the poorest’ could be a Goldilocks policy, appealing to both left and right of the political spectrum, albeit on different grounds.

So here’s the challenge: how can we ‘think and work politically’ to increase the adoption and expansion of cash transfer programmes – particularly more universalist ones? Time for a bit of action research, Oxfam?

May 15, 2018

Illicit economies, shadowy realms, and survival at the margins

Guest post by

Eric Gutierrez

,

Senior Adviser on Tackling Violence and Building Peace at Christian Aid

After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, poor landless farmers in the most conflict-affected areas of southern Afghanistan started migrating in increasing numbers to the relatively more insecure rocky desert areas. With the help of loans worth a few thousand dollars (typically provided by drug traffickers), they built their huts, prepared the land, and used percussion drills to sink tube wells of up to 100 meters deep to draw water out for growing opium poppy. After harvest, the loans were paid off, not in cash, but in high-value, low-volume, and non-perishable opium gum, collected very conveniently from right at their doorsteps by creditors. The opium plant itself (stalk, leaves, roots) was left on the ground to regenerate the sandy soil.

By 2013, an incredible transformation had taken place – an additional 300,000 hectares of agricultural land was created, supporting over 1.2 million people in southwestern Afghanistan alone. David Mansfield, the researcher who documented the transformation, and compressed it using satellite imagery and aerial mapping into a 2.5-minute video, challenged donors and development agencies: “show me a development project that has been this successful”.

Similar patterns – of poor peasants displaced by poverty and conflict taking a huge gamble to find their luck in more insecure areas to pursue illicit livelihoods – are found elsewhere. Field research (still to be published) in eastern Congo by Fraser Murray, a refugee and migration scholar, found that up to 73% of the 4.49 million internally-displaced people in that troubled region of warlords and ethnic militias choose to live outside the protection offered by the sprawling refugee camps administered by the UN and humanitarian agencies.

Poppy in Afghanistan (The US Dept of Defense posted this with the caption ‘Afghans work in a field’ – oops)

The live-out refugees typically engage in what another researcher called ‘guerrilla agriculture’, illegally planting food crops in nearby national parks reserved for wildlife. Some smuggle second-hand clothes and other small consumer items across the border with Uganda. Others, like the Twa people (forest-based hunter-gatherers) pushed out of the park, resort to poaching. In Shabunda, households set up illegal makeshift mines to extract coltan, a high-value mineral used in the manufacture of mobile phones.

Like Mansfield, Murray is sceptical of the actual aims of development agencies. He asks why 80% of humanitarian and development aid is spent inside the camps, when the majority of those who need it live outside. He points out that development actors misunderstand or have yet to seriously engage with the agency of people living at the margins.

These examples show the dynamics of survival in many of the world’s most dangerous places. “Dangerous places” is actually a technical label adopted by the Stockholm Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), to describe locations found in a total of 110 countries – 46 of which figure among the top 25% in terms of the highest violent death rates, and 78 of which are sources of 40% of the world’s refugees and internally-displaced persons. Hence, ‘dangerous places’ are typically those locations where state institutions do not or barely operate; where public services have gone missing or where infrastructure has been destroyed; or where insurance companies, banks, and firms don’t do business. In many cases, these are places too risky for humanitarian or development agency staff to even visit.

Yet as the examples reveal, people in these places somehow survive even without state protection or development aid. Life continues, albeit precariously and with many serious trade-offs. People living in dangerous places make choices and build relationships with ‘unusual actors’ to enable economic transactions and some form of order to survive. They spontaneously find ways to help themselves, typically by relying on informal, including illicit, economic activities, to tide them over. They are consequently stigmatised as criminals, and therefore regarded as outside the purview of official development. Whatever the problems are, these are typically seen as matters for law enforcement, and not for development or humanitarian agencies, to resolve.

The survival of poor communities engaged in illicit economic activities, almost without help and support from development agencies, makes the UN slogan of ‘Leave No One Behind’ look like empty rhetoric. The puzzle is – why are development agencies effectively defaulting on reaching poor people stigmatised as criminals? Why is there indecision on addressing the tough questions on illicit economies?

Over the last few years, a critical mass of research is starting to put illicit economies on the agenda of development agencies. Christian Aid published case studies on drugs and illicit practices, and on dangerous places in the Sahel. In June 2017, delegates from academia, policy, and the development sector attended a workshop at the University of Glasgow. And in April 2018, a Colloquium on the Development Implications of Illicit Economies was held at SOAS, University of London.

Debates on definitions appear to be one reason for the failure to focus on illicit economies. For example, Melissa Tullis of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) explains there still exists no official definition of “illicit financial flows”, making it extremely difficult for governments to agree on how to monitor the phenomenon. It was also for these reasons that ‘illicit financial flows’ almost did not make it into the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – it ended up in Goal 16, target 4.

Another gap is the lack of a model or theory for an in-depth understanding of the elusive, ever-changing details of illicit economies, explains professor Alfred W. McCoy, author of the classic The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia (1972).

McCoy suggests that there exists an invisible incubator for forms of illicit trades (illicit drugs, arms trafficking,

Coltan mine, DRC

human smuggling, illegal migration, etc.). He called this the ‘covert netherworld’, a shadowy realm and recurring clandestine domain beneath the surface of political life. Illicit economies persist because they have become the economic foundation of that shadowy realm that shapes, compromises, and corrupts conventional politics and political culture at the highest levels. Citing experiences in Myanmar, the Philippines, and Afghanistan, McCoy argued for the need to examine the deeper meaning of the character of illicit commodities and the implications of their phenomenal proliferation and persistence.

If indeed illicit economies are getting on the agenda, the next step now is how to bring this up in the portfolio of development agencies. Further longer-term collaboration between academia, policy, and development communities would hopefully develop sooner rather than later towards tackling the challenges of illicit economies, shadowy realms, and survival at the margins.

May 14, 2018

How to decode a UN Report on Global Finance (and find an important disagreement with the World Bank on private v public)

A giant coalition of UN-affiliated aid organizations (3 pages of logos!) recently published Financing for Development : Progress and Prospects 2018. These big tent reports are a nightmare to write, and not much easier to read. Anything contentious is fought over by the participants, and the result tends to be pretty bland. I’m not sure how many people read them, tbh.

: Progress and Prospects 2018. These big tent reports are a nightmare to write, and not much easier to read. Anything contentious is fought over by the participants, and the result tends to be pretty bland. I’m not sure how many people read them, tbh.

But on this occasion< I got the assistance of a helpful elf from deep inside the UN system to decode a significant disagreement within the ‘Inter-Agency Task Force’. You may not be surprised to hear that it’s basically the World Bank/IMF v the rest of the UN. Oh, go on then.

What does the World Bank say?

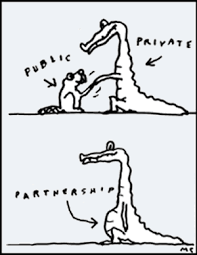

To put it crudely the Bank’s “Cascade” approach is ‘privatize everything first; if you can’t successfully privatize, then run a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) or blended finance operation or provide some guarantees for the private sector, and only if all the above fails should you go for public sector projects. Basically the Bank is returning to the 1990s under the rubric of “Maximizing Development Finance”. If you don’t believe me, here’s what the Bank tells its Development Committee (see page 2, Box 1 in this World Bank document).

“When a project is presented, ask: “Is there a sustainable private sector solution that limits public debt and contingent liabilities?”

If the answer is “Yes” – promote such private solutions.

If the answer is “No” – ask whether it is because of:

o Policy or regulatory gaps or weaknesses? If so, provide WBG support for policy and regulatory reforms.

o Risks? If so, assess the risks and see whether WBG instruments can address them.

If you conclude that the project requires public funding, pursue that option.”

To be fair, the Bank strategy does go on to say: “In assessing the potential of private solutions, the WBG will work with clients ensuring that the costs and benefits of private versus public solutions are properly assessed, and that equity and affordability concerns for consumers are properly addressed. More generally, private solutions will be promoted where they are economically viable, fiscally and commercially sustainable, transparent regarding the allocation of risks, provide value for money and ensure environmental and social sustainability.”

How does the UN report respond?

How does the UN report respond?

The report manages to sneak a few digs at this approach through sign off, talking about the importance of considering public goods, and emphasizing the risks from PPPs and blended finance. And of course. that Governments should have choice to match financing to their national strategies and, especially, preferences. Imagine the political uproar of the World Bank telling the UK that because UK public finance is limited and scarce, the NHS should be privatized by default regardless of political preferences simply because it is possible… yet that is one way the Cascade could be implemented.

Of course, there is nothing in the report outright saying the Cascade approach is a disaster – not surprising, since the World Bank is a partner on the report. But the implications of the analysis are that the Cascade is too crude a tool.

From the overview (page 2): “Public, private and blended financing contribute to financing SDG investments. … Private finance and investment, public and blended financing all remain indispensable. Project and country characteristics and national policy priorities will determine which financing model is best suited for specific investments, and which actors are best positioned to manage investment risks and provide services equitably and cost-effectively; Public policies and actions are at the heart of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.”

From Chapter II (page 15): “a key question underlying many of the international debates is what roles public, private and blended financing should play. The Addis Agenda stresses that all sources of financing are needed and that they are complementary, with different objectives and characteristics making them more or less suitable in different contexts and sectors. The Addis Agenda also underlines the potential of blended finance instruments, while calling for careful consideration of their appropriate structure and use.”

One way to characterize all of this is to ask whether the international community is saying (a) investment needs are

Page 1 of 3

huge, public finance is limited, and because of this the only solution is to leverage private finance; or is it saying (b) investment needs are huge, public finance is limited, and so we really need to raise tax revenue as well as leverage private finance and use them both more intelligently? Again, the report delicately critiques the private good/ public bad mantra.

“Equity, social inclusion and other public good considerations provide a rationale for public engagement through direct financing, subsidies, guarantees, or other incentives and/or regulation. This underscores the need for boosting public financial resources, both domestically (largely through improved taxation) and internationally (through official development assistance (ODA)).” (page 16)

“Private financing is most likely to be appropriate in sectors where projects can generate sufficient returns, such as in the energy sector, although with public oversight and often public support. The use of private finance is more challenging in areas where equity considerations and large financing gaps reduce profit prospects—such as water.

When the perceived risk of project failure is high, the cost of private finance, in particular, is likely to be prohibitive. Financing strategies need to consider how to avoid locking in high financial costs that reflect domestic risks for the entire duration of infrastructure projects (often 20 years or more). This also underscores the importance of public finance, either through direct financing or blending strategies. However, blended strategies can also create contingent liabilities that need to be carefully managed.” (page 16-17)

The report sounds several warnings about jumping to PPPs and blended finance as a ‘softer’ alternative to outright privatization.

“Providers are increasingly focusing on the ability of development finance to mobilize additional private or commercial financing, often referred to as “blended finance,” with a view to maximizing the impact of scarce public concessional resources and mobilize funding that would otherwise not have been available for SDG investments. Providers should also engage with host countries at the strategic level, to ensure that priorities in their project portfolios align with national priorities and that blending arrangements are in the public interest.” (page 88)

And there are particular worries about donors/MDBs going off and financing things with the private sector that the government doesn’t want (see pages 104-105)

Very helpful thanks – and if any other moles want to help me decode such aidspeak documents in future, my door is always open!

May 13, 2018

Links I Liked

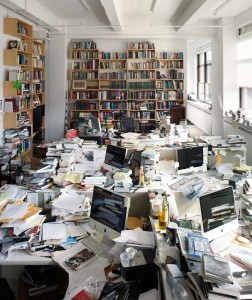

If someone ever criticises your tidiness, show them this, the New York Review of Books office. Ht Padraig Belton

States are Far Less Likely to Engage in Mass Violence Against Nonviolent Uprisings than Violent Uprisings

How Costa Rica Gets It Right by Joseph E. Stiglitz

Nice piece on ideas for avoiding boring time-suck meetings. My favourite suggestion, everyone in an organization should have a capped annual meeting budget = salary of those attending x length of meeting.

Brilliant from Branko. The 3 critical junctures that made Marxism a lasting influence: Engels, the First World War/October Revolution and Global Finance Capitalism

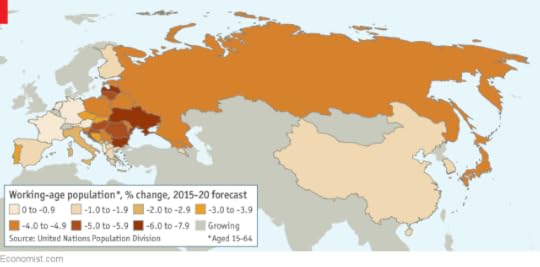

Forty countries now have shrinking working-age populations, (defined as 15- to 64-year-olds), up from nine in the late 1980s. China, Russia and Spain joined recently; Thailand and Sri Lanka soon will.

Forty countries now have shrinking working-age populations, (defined as 15- to 64-year-olds), up from nine in the late 1980s. China, Russia and Spain joined recently; Thailand and Sri Lanka soon will.

How to find surprising development successes. New paper developing a more rigorous methodology to identify and understand outliers. Please note, all positive deviance fans

Is the Bangladesh garment miracle unravelling? New research shows women garment workers are are paying too high a physical and emotional price. And from 2013-16/17, female manufacturing jobs dropped from 3.78 million to 2.86 million ht Arjan de Haan

I’m really enjoying IDR Online – a great Indian development blog. Here’s Dr Abhay Bang on how he discovered the power of research in changing policy, and why top-down research doesn’t work And an interview with feminist activist, poet, author and social scientist, Kamla Bhasin: ‘The villagers only agreed to the literacy centre because they didn’t know what connections I had. They were used to development workers coming to their communities for 6 months and then disappearing. Saying ‘yes’ to me was a way to stay out of trouble.’

Oops, one for the media training courses…..Watch Sainsbury’s CEO sing “we’re in the money” while waiting to talk about the £12 billion merger with Asda – he’s since apologised for his “unguarded moment”

May 10, 2018

Value for money in UK aid: the good, the bad and the ugly

Cathy Shutt (left, on vintage phone) and Craig Valters unsugar a recent pill on DFID’s

Cathy Shutt (left, on vintage phone) and Craig Valters unsugar a recent pill on DFID’s  approach to Value for Money

approach to Value for Money

All aid programmes should be good ‘Value for Money’ – hard to argue with that, right? 8 years ago, DFID put this principle at the heart of its work. Here we reflect on a recent report by the UK aid watchdog, ICAI.

The good

At first glance, the review appears good news. DFID is portrayed as a ‘global champion’, using value for money tools and approaches to increase the returns on its investment while influencing the practice of other donors, implementers, partner governments and NGOs.

ICAI concludes that DFID staff and implementers have a good grasp of the 3E framework (see diagram), which is used across the UK government to describe and assess value for money at various stages in programme cycles. Furthermore, at the behest of a previous ICAI review, DFID added a fourth ‘e’, equity. This aimed to ward off  concerns that penny pinching would lead to the prioritisation of programmes aiming to benefit large numbers of people, but missing the poorest who are more expensive to reach. At a theoretical level, this is a good start.

concerns that penny pinching would lead to the prioritisation of programmes aiming to benefit large numbers of people, but missing the poorest who are more expensive to reach. At a theoretical level, this is a good start.

In practice, value for money considerations have helped DFID curb waste, fraud and inefficiency. They’ve also driven down costs. It is sensible and right that this happens. Money wasted could be spent more effectively to help people both abroad, or indeed at home. The report suggests that DFID has taken this seriously.

The bad

That’s about it for the good news. Within programmes, the value for money focus tends to be on economy and efficiency in delivery, with effectiveness analysis proving highly erratic. The only convincing story of a value for money argument increasing cost effectiveness cited by ICAI relates to a programme in Uganda, where DFID staff drew on global evidence and encouraged implementing partners to use cash transfers rather than food aid. Failing to focus on effectiveness across the board undercuts the promise of value for money: what’s the point of doing things cheaply and quickly without demonstrable evidence that they are having sustainable impacts?

What’s more, the value for money approach of DFID is a bit too Mystic Meg: that is, it assumes DFID can make financial and social predictions when it can’t; DFID often works in complicated contexts, on complex problems. But ICAI found few cases of programme managers or participants monitoring the costs and outcomes of ‘small bets’ with a view to evaluating and learning what worked best and then adapting their approach. Instead they found that what might best be described as DFID’s blueprint planning approach is in tension with its commitment to learning and adaptation, emphasised in the Smart Rules.

Another alarm bell: ICAI commented that DFID staff regularly set overambitious results targets in their business cases – presumably to get them authorised (or more generously due to ‘optimism bias’). But then suppliers tend to reduce them once the stark reality of implementation kicks in. We worry this gaming of targets will be wrongly associated with adaptive management (‘ooh look, now we’ve banked the donor cheque, we can reduce our targets and call it being adaptive’). Adaptive management involves understanding we often don’t have solutions to problems upfront and puts in place serious learning processes to work them out. It’s not about not duping the system.

The ugly

According to ICAI, DFID’s value for money approach is narrow, focusing on individual projects, not their country or sector spending on complex and cross cutting issues like climate change. If DFID is serious about tackling the causes of poverty and conflict, as suggested in their aid strategy, then this is a false economy. It’s critical to consider the overall positive and negative contributions of DFID (and indeed wider government) in each country or region they work. In the absence of this, ICAI’s messages appear contradictory. DFID is a ‘global leader’ in value for money on the one hand, yet it resorts to the kind of bean counting that ignores issues of country strategy, complexity or long-term change on the other.

This accountability paradox is about methods – but also politics. Assessing the contribution of the British pound to a change process overseas is not easy, yet there are evaluation methodologies available (see here, here, and here). So, why haven’t alternatives been taken up?

change process overseas is not easy, yet there are evaluation methodologies available (see here, here, and here). So, why haven’t alternatives been taken up?

As one of us outlined here before, the reality is that over the past 10 years DFID’s political leaders became more interested in demonstrating quantifiable results to tax payers than longer term institutional change. The UK legitimately has a mix of development aims: from simple to complex, from short-term to long-term. But DFID’s value for money approach is reflective of the narrower political priority. Hence, we have ended up with misleading methods that suggest DFID and its suppliers are in control of development outcomes, when they’re not, and which ignores aid effectiveness principles of local ownership. This begs the perennial question, when it comes to value for money and accountability, whose values count and accountability to whom?

What’s to be done?

ICAI have sent a strong message that current value for money approaches are inadequate. So, what are the options for DFID and its implementers moving forward?

Can they get away with business as usual? DFID and the UK aid community could play the politics of the value for money game – appearing to be a global leader in using value for money for accountability while continuing to fall short in practice. The immediate prioritisation of the ‘global leader’ message by DFID communications department following ICAI’s report appears such a response.

Or, should we scrap value for money altogether? Pablo Yanguas has recently argued that value for money language will only suit simple initiatives like vaccination programmes. It thus leaves no option but to continue to mislead the public about the risks of supporting local actors to pursue institutional change. According to Yanguas, scrapping the idea of aid as a value for money investment is the way forward. It could force a more honest conversation with the public about the realities of aid, development and social change.

For now, we propose a compromise. Making financial savings in aid is a good thing. As is seeking to understand which interventions, comparatively, can be most effective for the money being spent. It is also unlikely and undesirable that pressures to spend taxpayers’ money well will disappear. So, the starting point must be that senior DFID leadership take this report seriously. A recent performance in front of MP’s suggests they are doing so. The challenge will be for them to reframe how value is understood in the department and by its implementers: that may mean taking possibly unpalatable messages to politicians about the uncertainty of developmental change processes, rethinking evaluative methods, and telling a better story of the UK’s role in long-term change.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers