Duncan Green's Blog, page 93

June 20, 2018

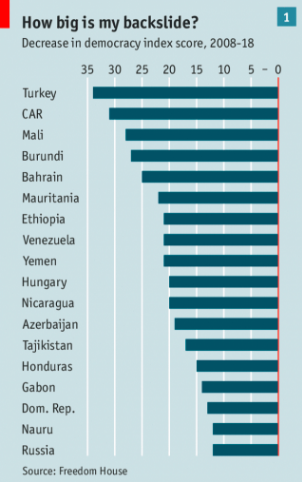

Democracy’s Retreat: a ‘how to’ guide

reversal in dozens of countries. Shades of Nic Cheeseman and Brian Klaas’ great book, How to Rig an Election. Some excerpts:

‘A democracy typically declines like this. First, a crisis occurs and voters back a charismatic leader who promises to save them. Second, this leader finds enemies. His aim, in the words of H.L. Mencken, a 20th-century American wit, “is to keep the populace alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary.” Third, he nobbles independent institutions that might get in his way. Finally, he changes the rules to make it harder for voters to dislodge him. During the first three stages, his country is still a democracy. At some point in the final stage, it ceases to be one.’

‘Picking the right enemies is crucial. Migrants are good, because they cannot vote. Mr Soros is even better, because he is rich, funds liberal causes and is, you know, Jewish. He can be painted as all-powerful; but because he is not, he cannot harm the demagogues who demonise him.

Stirring up ethnic hatred is incredibly dangerous. So rabble-rousers often use dog-whistles. South Africa’s former president, Jacob Zuma, denounced “white monopoly capital” rather than whites in general. Many leaders pick on small, commercially successful minorities. Zambia’s late president, Michael Sata, won power after railing against Chinese bosses.

Criminals make ideal enemies, since no one likes them. Rodrigo Duterte won the presidency of the Philippines in 2016 on a promise to kill drug dealers. An estimated 12,000 extra-judicial slayings later, the country is no safer but his government has an approval rating of around 80%.’

Criminals make ideal enemies, since no one likes them. Rodrigo Duterte won the presidency of the Philippines in 2016 on a promise to kill drug dealers. An estimated 12,000 extra-judicial slayings later, the country is no safer but his government has an approval rating of around 80%.’

‘To remain in power, autocrats need to nobble independent institutions. They do this gradually and quietly. The first target is often the justice system. Poland’s ruling party passed a law in December forcing two-fifths of judges into retirement. On May 11th Mr Duterte forced out the chief justice of the Philippines, who had objected to his abuse of martial law.

The media must be nobbled, too. First, an autocrat in waiting puts his pals in charge of the public broadcaster and accuses critical outlets of spreading lies. Rather than banning independent media, as despots might have done a generation ago, he slaps spurious fines or tax bills on their owners, forcing them to sell their businesses to loyal tycoons. This technique was perfected by Mr Putin in Russia, and is now widely copied. In Turkey, the last big independent media group was in March sold to a friend of Mr Erdogan.’

And then, just in case you were thinking there is no hope:

‘Democrats can fight back. Five recent examples stand out. In Sri Lanka, the opposition united to beat a spendthrift, vicious autocrat. In the Gambia, the threat of an invasion by neighbouring countries forced a strongman to accept that he had lost an election. In South Africa, an elected leader who subverted institutions and let cronies loot with impunity was tossed out by his own party in January. In Armenia, an autocrat was ousted in April by mass protests.

And in Malaysia, the prime minister, Najib Razak, tried to steal an election in May but failed. Despite  gerrymandering, censorship and racist appeals to the Malay majority, voters dumped the ruling party of the past 61 years. Its sleaze had grown too blatant. America’s justice department has accused Mr Najib of receiving $681m from 1MDB, a state fund from which $4.5bn disappeared. He says the money was a gift from an unnamed Saudi royal. The opposition gleefully contrasted the vast sums Mr Najib’s wife spends on jewellery with the difficulty ordinary folks have making ends meet. “Najib just makes up his own rules,” says a taxi-driver who switched sides to back the new government.’

gerrymandering, censorship and racist appeals to the Malay majority, voters dumped the ruling party of the past 61 years. Its sleaze had grown too blatant. America’s justice department has accused Mr Najib of receiving $681m from 1MDB, a state fund from which $4.5bn disappeared. He says the money was a gift from an unnamed Saudi royal. The opposition gleefully contrasted the vast sums Mr Najib’s wife spends on jewellery with the difficulty ordinary folks have making ends meet. “Najib just makes up his own rules,” says a taxi-driver who switched sides to back the new government.’

Wonderful – the Economist is always great as long as it steers clear of, you know, economics……

The post Democracy’s Retreat: a ‘how to’ guide appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

June 19, 2018

What did I learn from a week discussing Adaptive Management and MEL?

Just got back from an extraordinarily intense week in Bologna, running (with Claire Hutchings and Irene Guijt) a

Bologna: Tough gig, but someone had to do it

course on ‘Adaptive Management: Working Effectively in the Complexity of International Development’.

The 30 participants mainly came from NGOs and non-profits, but with a smattering of government officials and consultants. What made the discussion different from previous AM chats is that they were largely involved in the nuts and bolts of Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL). Broadly, they fell into two camps: MEL people whose organizations find themselves increasingly being told to ‘be more adaptive’, and want to know what on earth that means, and others who have already bought into the importance of systems thinking and adaptive management, but now are wondering how to put it into practice in an aid sector that has lots of countervailing pressures – short project cycles, tangible and attributable results, the dreaded logframe and all the rest.

That meant that the week got much more into the practical side (here’s the outline – please steal Adaptive Management week plan). Students were asked to bring a ‘nut to crack’ from their day jobs, and Irene and Claire, who have decades of MEL experience between them, were able to provide lots of tools and ideas that can help navigate complex systems (while always eschewing a single AM recipe). I contributed my usual systems/ power/ how change happens waffle.

The main output was a set of ‘rules of thumb’ for putting AM into practice, generated by the participants. We’re still refining that – will post for comments once it’s ready. In the meantime, here are some random insights and observations from the week.

Important to think about when not to do AM – the Cynefin framework is really useful – trad linear approaches work in the simple and (with more thought) complicated quadrants. AM comes into its own in the complex one.

Important to think about when not to do AM – the Cynefin framework is really useful – trad linear approaches work in the simple and (with more thought) complicated quadrants. AM comes into its own in the complex one.

AM raises all sorts of problems and challenges for partnership, whether with organizations you fund, host governments that you are trying to work with, or partners in multi-stakeholder initiatives. Who decides when/what/how to adapt? What if they don’t want you to be adaptive, but would rather you just get on and deliver what you initially promised? Lots of host governments just want ‘training and trips’.

AM costs money: all this standing back, reflecting, real time evaluation, piloting, comms with donors and governments to keep everyone onside while the project evolves etc requires time and investment. Are donors and our own bosses ready for that?

The ‘toolkit temptation’ is alive and well: try as they might to stress that the key to AM is rising above the toolkit and ‘dancing with the system’, Irene and Claire were constantly being asked for them. That’s just how aid folk rock. I experienced the same feeling while writing How Change Happens and ended up compromising with a ‘power and systems approach’ that emphasizes ways of working, behaviour and questions, not processes or answers.

Do MEL teams need to be rethought, rebranded or even scrapped altogether and absorbed into project teams? Too often MEL is seen as low status bean-counting, internal police/executioner, or a combination of both. I used to be very rude about them til I realized that people like Claire and Irene are among the smartest people in Oxfam. In AM, the MEL function needs to emphasize the ‘L’ bit – how can MEListas become critical friends, incubators of new ideas and champions of AM, both within and beyond the organization?

Comms with donors, host governments and others are even more important in AM, eg during long inception and experimentation phases with few tangible results. But whose job is it? MEL teams are often happier with number crunching than telling inspirational stories. Should story telling become a recognized and separate function? Come to think of it, I guess it’s part of what I do at Oxfam, though we’ve never described it that way.

Trust is essential to AM. Donors need to trust that AM is not just bad management; host governments and communities need to trust that all this fiddling about is going to help them in the end. So how to build and maintain trust? There could be a role for ‘critical interlocutors’ – people at arm’s length from the project, who understand it and the issue, and can communicate with others with independence and authority.

But what happens if trust is abused? What happens when lazy or incompetent people do AM? It’s a bit like the US constitution – designed not for good governments but for bad ones (and getting a good stress-testing right now, as it happens). Is AM easier to game than traditional aid formats? On the margins of one recent discussion, I was told that unscrupulous management consultants now deliberately bid low to win contracts, then hide behind AM as an excuse to reduce their delivery targets.

AM in fragile/conflict settings. On the surface it looks like a no brainer – these are supremely complex places, so linear approaches are much less likely to work. But in practice, often aid workers can do little more than simply respond to events – riding the tiger/ ‘blaming ethe context’. That misses out on the other essential element of AM – reflecting on and revisiting assumptions and strategy.

linear approaches are much less likely to work. But in practice, often aid workers can do little more than simply respond to events – riding the tiger/ ‘blaming ethe context’. That misses out on the other essential element of AM – reflecting on and revisiting assumptions and strategy.

How to spread the AM message? The aid sector typically propagates new orthodoxies through toolkits and protocols, but standardising those is anathema to AM. If not toolkits then what? Case studies? Charismatic champions (where’s the AM TED talk?). Exposing and ridiculing alternative approaches that fail? Other ideas?

Overall it felt last week like we have reached a crossroads: There’s now a ‘there’ there, a substantial case and growing body of evidence for when and how AM works, but numerous barriers and uncertainties remain. Maybe AM now needs its own more deliberate theory of influence – as one participant said: ‘what works best is waiting until we are 2 or 3 years into a project, when it hits a crisis and those in charge suddenly become interested in new approaches.’ Applying AM to the adoption of AM is a bit meta/turtles all the way down, but it may be what is needed.

Thoughts?

June 18, 2018

The Global Humanitarian Assistance 2018 report is out today – here are six top findings

supporting numbers:

1. Humanitarian Assistance (HA) mainly goes to a small number of countries: ‘60% of all assistance was channelled to 10 countries only, with 14% going to Syria, the largest recipient, and 8% to Yemen, the second-largest.’

2. HA is growing in absolute terms and as a percentage of overall aid budgets: ‘2017 saw a record US$27.3 billion allocated to humanitarian responses. Although both show an upward trend from 2007, the level of humanitarian assistance within overall ODA is growing faster (at 124% since 2007) than overall ODA (at 41% since 2007).’

3. HA still mainly flows via the big aid organizations: ‘In 2016, US$12.3 billion or 60% of all direct government funding went to multilateral agencies (primarily UN agencies) in the first instance. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) received US$4.0 billion directly – 20% of the total. A growing majority of this went to international NGOs who received 94% of all funding to NGOs in 2017, up from 85% in 2016.’

4. Local NGOs are still living off scraps – localization ain’t happening: ‘Local and national NGOs received just 0.4% directly of all international humanitarian assistance reported to FTS in 2017, a rise of just 0.1% from 2016’.

4. Local NGOs are still living off scraps – localization ain’t happening: ‘Local and national NGOs received just 0.4% directly of all international humanitarian assistance reported to FTS in 2017, a rise of just 0.1% from 2016’.

5. Emergencies aren’t emergencies any more – they are long term crises: ‘17 of the 20 largest recipients of international humanitarian assistance in 2017 were either long-term or medium-term recipients.’

6. Cash Transfers are on a roll: ‘An estimated US$2.8 billion of international humanitarian assistance was allocated to this in 2016, a 40% increase from 2015.’

And here’s a handy (if crowded) summary infographic

June 17, 2018

9 development trends and their implications for tomorrow’s aid jobs

This is an expansion of a blog first posted in February. According to the reader survey, most people reading this blog are a lot younger than me – students or entrants to the job market, with at least half an eye on how they are going to earn a living in the decades to come. I read and write a lot about trends in aid and development, so it’s worth speculating what they mean for the kinds of jobs today’s students might be doing in 20 years’ time, focussing on aid sector pracititioners, rather than academia. Here are some initial thoughts (in no particular order) – over to you to flesh them out:

Trend 1: Poverty will become concentrated in fragile and conflict affected states

Implications: Tomorrow’s aid workers will need to grapple with issues of violence, conflict and messy politics. If the ideas behind the Doing Development Differently network prosper, there will be a premium on the kind of adaptive skills necessary to ‘dance with the system’, rather than the implicit Stalinism of ‘rolling out best practice’.

Trend 2: There will still be a significant flow of philanthropic funding from North to South

Implications: There will always be a need for money people – raising it, spending it, reporting on how it is used. That is unlikely to go away, though it may change in form (eg the move to direct cash transfers rather than projects, aka disintermediation)

Trend 3: Localization of Humanitarian Response and long term development programmes

Implications: The days of the expat white men in shorts are over. Running projects in developing countries is a job for people in and from those countries, and about time too. On the other hand, if you’re from the South (as many of my LSE students are), then there will always be lots to do, whether in government, NGOs or the private sector.

Trend 4: The rise of Advocacy and Campaigns

Implications: Don’t panic, altruistic northern youth, there will still be lots to fix, not least stupid or evil policies and practices of your own governments or companies (tax havens, arms trade, pollution, protectionism, terrible asylum policies). ‘Influencing’ – the umbrella term for advocacy and campaigns, requires political savvy, born above all of experience. Get involved in campaigns, or lobbying, or other attempts to influence the system – they don’t really teach this stuff at school (although I am giving it a go). Alternatively, get some comms skills – always useful, or go to law school (‘the state sees the world through the eyes of the law’ as one Spanish lawyer once explained to me).

Implications: Don’t panic, altruistic northern youth, there will still be lots to fix, not least stupid or evil policies and practices of your own governments or companies (tax havens, arms trade, pollution, protectionism, terrible asylum policies). ‘Influencing’ – the umbrella term for advocacy and campaigns, requires political savvy, born above all of experience. Get involved in campaigns, or lobbying, or other attempts to influence the system – they don’t really teach this stuff at school (although I am giving it a go). Alternatively, get some comms skills – always useful, or go to law school (‘the state sees the world through the eyes of the law’ as one Spanish lawyer once explained to me).

Trend 5: The end (or at least blurring) of North-South distinctions

Implications: Some of the big challenges in ‘developing’ countries increasingly resemble those in ‘developed’: accountability, gender inequality, environmental management, migration, non-communicable diseases, road traffic, alcohol and substance abuse, depression. ‘Aid’ will look less and less like a separate sector, and more like an extension of domestic debates and reform efforts – eg environmental health specialists being seconded from one country to another. Soft skills like matching experts and helping them work together across countries and cultures will be invaluable. Alternatively, become an expert yourself in something useful, and then travel.

Trend 6: the rise of the Private Sector

Implications: Aid itself is increasingly being administered by big private companies, but given the declining overall importance of aid in most developing countries, other forms of private sector activity will matter more in the long term. Sorting out supply chains of global companies; taking social enterprise through its current hype into something that makes a genuine contribution; making markets work for the poor. Hating/dismissing the private sector was never particularly sensible (aren’t small farmers everywhere part of it?), but will make even less sense in future. Instead, think about getting experience in different bits private sector and then applying it to development challenges.

Trend 7: The push for evidence, results and value for money

Implications: Hard to see this trend going into reverse, although I do hope it becomes more nuanced and intelligent, better able to cope with complexity and unpredictability and to stop pushing projects towards doing dumb-but-measurable stuff. Lesson here is learn the skills and jargon of the bean counters, and then use/adapt them to make all our activities more effective.

better able to cope with complexity and unpredictability and to stop pushing projects towards doing dumb-but-measurable stuff. Lesson here is learn the skills and jargon of the bean counters, and then use/adapt them to make all our activities more effective.

Trend 8: The technologization/digitization of everything

Implications: Beware the hype. Yes there probably is an app that can help, whatever the problem, but it won’t substitute for the interplay of power, organization and struggle, and in any case, the app is probably best written by a bunch of coders in Nairobi, Manila or Bangalore, not some café hipster in Brooklyn or Hoxton.

Trend 9: #MeToo, #AidToo and intersecting inequalities

Implications: I think we’ve crossed some kind of Rubicon on this. Wherever you work, you will need to be literate on issues of power and exclusion. That means being self-aware and self-critical both in thought and practice (reflexivity).

Looking at these, ‘aid’ and ‘development’, which were never synonymous to begin with, are diverging rapidly. I fear that one consequence is that Development Studies, at least at undergrad level, may be less and less suitable as a direct route to a job – it feels like it’s designed for a vanishing world (see here for a trenchant critique). That’s worrying, as the numbers of DS students are booming, but maybe its decline as a path to jobs will be compensated by other factors, like what you learn about the world while you’re studying it (a bit like studying history). Back out in the jobs market, the premium will be on a combination of specialist skills and emotional and political intelligence. Not sure what department teaches that!

I look forward to your additions, corrections etc

And just in case you’ve never seen them, or want to watch them again, here’s a couple of my favourite satires on the aid biz. Enjoy.

June 14, 2018

Links I Liked

Graphics are back up, on an interim blog format til we sort it out properly. Please let me know if you are  experiencing any probs with the new format.

experiencing any probs with the new format.

The Free Tommy Robinson March has accidentally bumped into the World Naked Bike Ride event in London. What a time to be alive. ht ‘Chairman LMAO’

‘Petronia is a simulated learning experience exploring challenges of a fictional developing country at the outset of oil production.’ Interesting gamification of Curse of Wealth from the Natural Resource Governance Institute. I’d be interested in any player reviews.

Don’t be a conference troll: an oldie-but-goodie guide to asking good questions

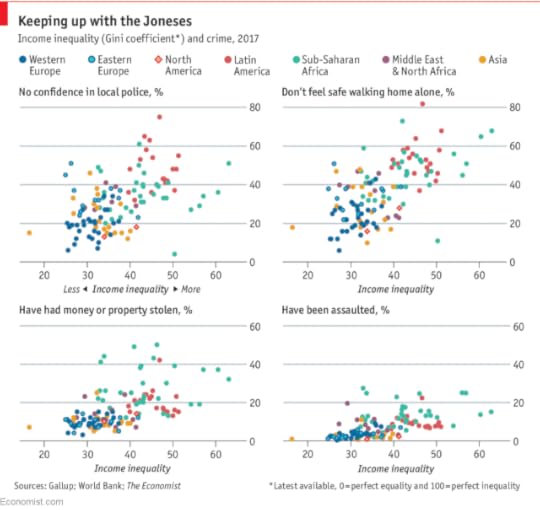

The stark relationship btw inequality and crime

Independent watchdog ICAI is critical of UK aid spending outside DFID – looks like a throwback to the bad old days of ‘aid for arms’ and the Pergau Dam

Owen Barder asks which kinds of aid can be ‘win-win’ for recipient and donor and when does pursuing UK national interest damage aid?

PDIA and Climate Change Adaptation. Report back on the Harvard Building State Capability team’s ‘first attempt at customizing our free PDIA online course to a specific theme’.

Tobacco (7m) Alcohol (3m) and High Body Mass (4m) are major killers. Sugar, tobacco and alcohol taxes (STAX) have measurable impact on all 3. Must read from The Lancet ht Robert Marten

‘Rather than proposing the economics for the 21st century, Raworth’s book brings us back to the imaginary world of early Christendom.’ Branko Milanovic has his doubts about Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics. Looking forward to Kate’s reply!

Only just catching up with this weird and overlong movie-trailer-style video on US-Korean talks, which Trump showed Kim last week. Background here

June 13, 2018

What did I learn from teaching LSE students about advocacy and campaigns?

I spent a week last month marking student assignments. Sounds boring, right? Well it was brain-drainingly hard work, but it was also enthralling. Usually I just give lectures or write stuff, and the level of feedback is pretty cursory. In contrast, marking the assignments for a course you have taught provides a unique peek inside students’ heads – you find out what students have learned or added, but also where you messed up and left them unclear or mistaken.

work, but it was also enthralling. Usually I just give lectures or write stuff, and the level of feedback is pretty cursory. In contrast, marking the assignments for a course you have taught provides a unique peek inside students’ heads – you find out what students have learned or added, but also where you messed up and left them unclear or mistaken.

This was the first year of the course, a one term LSE Masters module on Advocacy, Campaigning and Grassroots Activism. I’ve blogged before about the pleasures of teaching 33 bright sparks from around the world (only one Brit), many with relevant experience in NGOs, aid sector, journalism etc. They had two marked assignments – groups selected past episodes of change for analysis (guidelines here: DV 445 Guide to Analysing Past Stories of Change); individuals had to develop a proposal for a campaign/influencing exercise they would like to carry out (guidelines here: DV 445 How to Design an Influencing Strategy Jan 2018). Plus blogs of course.

well kind of….

So what happened? I was expecting a fairly predictable set of historical case studies (Berlin Wall, fall of Apartheid, Brexit), but actually got a much more interesting collection, including why Martinique voted to remain part of France when everywhere else was decolonizing, and the legalization of Birth Control in the US. Things that really worked included

Asking students to construct a timeline of the episode, which seemed to get people thinking more broadly about sequences of interacting factors.

Ditto a stakeholder mapping, preferably on a 2×2 of support/opposition v level of influence

A good grasp of different facets of power – the most popular frameworks were Lukes (visible, hidden and invisible) and Rowlands (power within, with, to and over)

Highlighting the interaction between processes and events (‘critical junctures’)

Gaps? Slower, contextual change, eg demographic, or economic (changing labour markets) often gets squeezed out by a focus on actors and events. Some groups jumped straight to their preferred explanation for a given event, and failed to consider alternatives (did Ellen Johnson Sirleaf really win in Liberia because of the country’s women’s movement, or were other factors as or more important?)

The individual campaign proposals were mind-blowingly varied – everything from changing public attitudes towards human rights in the Philippines, to removing the tampon tax in Rwanda, banning plastic bags in Austria and introducing climate insurance in Sudan. Gender equality, health and environmental issues were the most popular topics.

Here again, students made excellent use of stakeholder mapping and context analysis as a basis for their proposed change projects. A number identified windows of opportunity/critical junctures for change (eg electoral timetables), rather than just setting out ‘here is what we are going to do’. Good recognition of the importance of individual champions. Everyone loved league tables.

Lots of engagement with the more subtle challenges of changing norms, rather than just ‘change that law/ban that practice’. Connected to that, some students recognized the importance of religion and faith in shaping norms and practices, while others followed standard aid business practice and ignored them completely!

practice’. Connected to that, some students recognized the importance of religion and faith in shaping norms and practices, while others followed standard aid business practice and ignored them completely!

A couple of factors emerged that I will have to add for next year: the importance of precedents – historical or contemporary – in proving that a given change is possible; a couple of students went back to analyse why previous campaigns they were involved with had failed, and what they should have done differently.

But the common failings were also instructive (especially as I design an expanded course for next year):

Ignoring the opposition: several stakeholder mappings just covered potential allies, without considering the opposition, and whether it was sufficiently strong to constitute a priority target for an influencing campaign. Going to have to think more about weakening/bypassing/winning over the bad guys.

Power: Some people combined power analysis and stakeholder mapping, but the proposals that considered them separately were a lot more interesting; several people struggled with the distinction between hidden and invisible power (it took me years of tuition by Jo Rowlands to really grasp the distinction).

Sense of humour bypass: not many of them showed a sense of mischief/fun – will have to do a bit more on Popovic and the use of humour in campaigning!

Watch out Austria….

The state: people still tend to see the state as a monolith, usually a hostile one. Need to get them thinking more about the state as a complex system – cooperation and competition between tiers of government, ministries, or between civil servants, politicians, judges and MPs – and how those can be incorporated in a campaign.

Perhaps connected to that last point, there was still an occasional tendency to default to a purely outsider strategy (especially social media), rather than think through the possibilities of incorporating some insider influencing.

All in all, a fascinating experience. Already looking forward to next year!

June 12, 2018

World Inequality Report 2018: 3 insights and 2 gaps

I was a discussant at the London launch of the World Inequality Report 2018 last week by the WIR team’s Lucas Chancel. (The book, that is – the online version was released in December)

The WIR is produced by a team of economists who contribute to the WID.world database, of whom the biggest rock star is Thomas Piketty. The database is laudably transparent and user-friendly, and scrapes lots of different sources to try and build as comprehensive a picture of inequality as possible. That means national income and wealth accounts (including, when possible, offshore wealth estimates); household income and wealth surveys; fiscal data from taxes on income; inheritance and wealth data (when they exist); and wealth rankings. Phew.

The findings are striking:

‘Inequality has increased in nearly all world regions in recent decades, but at different speeds’. See Fig 2A. But fellow panellist Paul Segal pointed out that if you look closer at that graph you find another interesting development – the rate of increase of inequality has fallen since the mid-2000s, and inequality is now falling in most countries. But we’re not quite sure why, or whether it is a long term trend, or a short-term blip caused by e.g. the financial crisis.

In regions of the world like the Middle East, India and Brazil that did not experience a ‘great compression’ of inequality in the 20th Century (which went into reverse roughly up to 1980), you see something that looks like a natural ‘inequality frontier’, where the top 10% trouser about 60% of national income. That may be where Europe, US and China are now headed (see Fig E2b). Open question whether that frontier is static or rises over time as economies grow.

A really interesting discussion on the inequality impact of private v public ownership, a debate that the report acknowledges is an unusual combination of macro and micro:

‘Economic inequality is largely driven by the unequal ownership of capital, which can be either privately or public owned. We show that since 1980, very large transfers of public to private wealth occurred in nearly all countries, whether rich or emerging. While national wealth has substantially increased, public wealth is now negative or close to zero in rich countries. Arguably this limits the ability of governments to tackle inequality; certainly, it has important implications for wealth inequality among individuals.’

All really interesting, but (there’s usually a but), as I read the paper and looked at all the charts on powerpoint, I started to have my doubts.

Firstly, my mind went back to those conversations back in 2013 at Twaweza, a great East African NGO that had assumed that putting information (in this case on the appalling state of education in East Africa) into the hands of the public would lead the public to take action. It didn’t. Cue a fascinating bit of heart searching about the limits to access to information.

Might WIR face a similar problem – in what circumstances will endlessly expanding, improving and cleaning up data lead people to take action on inequality? After all, giving climate change deniers more information about climate change actually deepens their opposition to doing anything about it. The assumption that data leads to action really needs to be looked at in more depth.

And the report was frustrating because although it is superficially political (lots of Piketty-esque barbs about how much better Europe social democracy performs than the USA), it never really gets beyond recommending some fairly standard policies (progressive taxes, prevent tax evasion, invest in education, inheritance tax). There’s some kind of implicit assumption in here that decision makers at some point will want to tackle inequality, even if it courts unpopularity (eg on inheritance tax) and will be strong enough to resist the inevitable backlash from those who lose out. That’s a big tin opener.

What it doesn’t do is even ask if any of the policies proposed are politically feasible, or what might be needed to make them so. The memorable caricature of NGO reports as ‘bad shit; facty, facty’ now becomes ‘bad shit; facty facty; policy solutions; no politics’. Is that really good enough?

When I briefly ranted on to this effect, Lucas reasonably enough said that his crew of economists couldn’t be expected to do everything, and this was someone else’s job (power analysis, stakeholder mapping, building coalitions, seizing windows of opportunity and all the rest). The problem with that answer is a) there seems to be an imbalance between the academic effort to measure, and the academic effort to design feasible change strategies and b) if you combine the two, rather than treat them as distinct stages, you are likely to think design the research differently to have impact. For example, if you want to influence decision makers in country X, you may want to compare it particularly to its annoying neighbour Y, not some country thousands of miles away that it doesn’t care about.

Anyone seen any good reviews and crits of WIR?

June 11, 2018

Violence v Non Violence: which is more effective as a driver of change?

Next up in the series of graphic free posts (until we fix the WordPress upgrade) Oxfam’s Ed Cairns explores the evidence and experience on violence v non violence as a way of bringing about  social change

social change

One of the perennial themes of this blog is the idea that crises may provide an opportunity for progressive change. True. But I’ve always been nervous that such hopes can forget that most conflicts cause far more human misery than any good that may come.

This is something that Duncan and I have (non-violently) tussled about over the years. So imagine my delight when I saw a recent report that seems to back up my caution. The International Center on Nonviolent Conflict’s paper on Nonviolent Resistance and Prevention of Mass Killings looked at 308 popular uprisings up to 2013. It found that “nonviolent uprisings are almost three times less likely than violent rebellions to encounter mass killings,” which faced such brutal repression nearly 68% of the time. The authors, Erica Chenoweth and Evan Perkoski, think this is because violent campaigns threaten leaders and security forces alike, encouraging them to “hold on to power at any cost, even ordering or carrying out a mass atrocity in an attempt to survive.”

There is a positive lesson here, that nonviolence works – at least better than violence. This builds on Chenoweth’s earlier study, which suggested that between 2000 and 2006, 70% of nonviolent campaigns succeeded, five times the success rate for violent ones. Looking back over the 20th century, she found that non-violent campaigns succeeded 53% of the time, compared with 26% for violent resistance.

Again, there is a positive lesson – though it’d be interesting to know the figures since 2006, when the world appears to have become more repressive and violent. 2017 was the 12th year, according to the US-based Freedom House, “of decline in global freedom [as] seventy-one countries suffered net declines in political rights and civil liberties.” As the Uppsala Conflict Data Program shows, these years of pressure on rights have coincided with sharp rises in conflicts since the start of this decade. And according to the 2018 Global Peace Index, just out this month, “peacefulness has declined year on year for eight of the last ten years.” This seems to suggest that in our violent and challenging decade, nonviolent campaigns have found it tough in many countries too.

Tragically, this may breed a climate of desperation. In another recent article, Robin Luckham wrote that “the temptations of violence… are even stronger when authoritarian regimes violently crush non-violent protests…The turn from non-violent to violent resistance can easily open the way for more ruthless and better armed groups to step into the political spaces initially opened up by peaceful protests, as in Syria and Libya.”

This brings us perhaps to a less positive lesson – that living under tyrannies may be less worse than violent campaigns to change them. Chenoweth and Perkoski argue that “popular uprisings are not all alike. Some, like those in Libya (2011) and eventually Syria (2011), are predominantly violent, wherein the opposition chooses to take up arms to challenge the status quo. Others, like Tunisia (2010), Egypt (2011), and Burkina Faso (2014), eschew violence altogether.”

“Choose to take up arms”? That’s a harsh way to describe the situation at least some armed groups have faced. We should never forget that state repression often drives uprisings to become more violent. But looking at the historical evidence in these articles – and at almost every conflict now – it’s difficult to escape the conclusion that armed resistance is seldom successful, often counterproductive, and therefore rarely justifiable.

This begs one final question which Chenoweth and Perkoski can help with. Few would now argue that foreign countries should intervene to change regimes. But the UK Parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committee is conducting an enquiry on the prospect of military interventions for a different purpose – to stop mass killings. Its chair, Thomas Tugendhat, suggested that ‘The Cost of Doing Nothing’ in Syria had been thousands and thousands of lives.

I’ve never been convinced of that case in Syria, though the world’s failure to stop the genocides in Rwanda and Bosnia in the 1990s was among the most shameful events of our times. But Chenoweth and Perkoski highlight the danger of any kind of foreign intervention. The likelihood of mass killings increases, they conclude, both “when foreign states provide material aid to dissidents… [and] to the governments the movements oppose.” In the first case, that’s because foreign support to oppositions encourages states to perceive them “as an existential threat.”

We shouldn’t conclude that military action will never ever be justified to prevent mass killings. But we know more reasons for caution than we once did. Every foreign action needs to be carried out with the best possible knowledge of its consequences.

That’s a harder thing to do than in the 1990s, when this debate first forced its way onto humanitarian agendas. According to a UN/World Bank study, there were eight armed groups in an average civil war in the 1950s. By 2010, there were fourteen. In Syria in 2014, there were more than a thousand. While more local parties are fighting within borders, regional powers – like Saudi Arabia and Iran – as well as Russia and the US are more willing to contemplate war, in what Robert Malley of Crisis Group calls the world’s “growing militarization of foreign policy.” It is in this dangerous world that the risks of military action are higher than when the ideas of “humanitarian intervention” and Responsibility to Protect were developed.

I’ve never believed that pacifism is an adequate answer to a world of atrocities that – in truly exceptional cases – call out for an armed response. But there’s an awful lot of evidence for caution – and reason to give peace a chance.

June 10, 2018

A bombshell Evaluation of Community Driven Development

[if you’re wondering why no pics, the blog is being upgraded at the moment, and there are some glitches. Don’t think this post needs much in the way of illustration though, so here goes]

Blimey. Just read a bombshell of a working paper assessing the evidence for impact of Community-Driven Development (CDD) programmes. It’s pretty devastating.

In CDD, community members are in charge of identifying, implementing and maintaining externally funded development projects. CDD programmes have been implemented in low- and middle-income countries to fund the building or rehabilitation of schools, water supply and sanitation systems, health facilities, roads, and other kinds of public infrastructure.

The archetype is Indonesia’s World Bank financed Kecamatan Development Project, launched in 1998, the brainchild of charismatic anthropologist Scott Guggenheim, who is currently working in Afghanistan, as senior advisor to President Ashraf Ghani.

The evaluation is by the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3IE), which summarizes CDD’s evolution thus:

‘Over the last three decades, they have evolved from being a response to mitigate the social cost of economic structural adjustment to becoming an alternative delivery mechanism for social services that link directly with communities. In addition, since the 2000s, there has been more emphasis on using CDD programmes for building social cohesion, increasing decentralisation and improving governance.’

3IE cast its baleful eye over the evidence from 25 impact evaluations, covering 23 CDD programmes in 21 low- and middle-income countries and concluded.

CDD programmes have no impact on social cohesion or governance.

Many community members may hear about CDD programmes but not many attend meetings.

Few people speak at the meeting and fewer still participate in decision-making.

Women are only half as likely as men to be aware of CDD programmes and even less likely to attend or speak at community meetings.

CDD programmes have made a substantial contribution to improving the quantity of small-scale infrastructure.

They have a weak effect on health outcomes and mostly insignificant effects on education and other welfare outcomes.

There is impact on improved water supply leading to time savings.

Okaaay. Digging into the findings, they conclude that part of the problem is the focus on building stuff. ‘Investments in water-related infrastructure have reduced the time required for collecting water. These programmes slightly improve health- and water-related outcomes, but not education outcomes. Their lack of impact on higher-order outcomes can be explained by the focus on infrastructure.’

If you ask meetings dominated by men what they need, they will usually say ‘a road’ or other piece of infrastructure, so perhaps this isn’t that surprising.

The analysis also found that ‘This approach has been successful in achieving greater resource allocation to poorer areas, although not always to the poorest communities in those areas.’ That also could reflect the dangers of treating ‘the community’ as a single entity, rather than understanding it as a complex system of power in which some groups dominate others (men v women, less poor v more poor, able bodied v disabled).

Finally, the paper worries about the sustainability issues, because it finds that CDD projects often set up parallel systems to deliver the water, sanitation, roads, housing or whatever ‘the community’ decides on, but ‘These parallel structures may alienate community leaders. The function of these governance structures is also often not clear once the community projects end.’

Without knowing much about it, I’d always vaguely thought that CDD must be a Good Thing. On the basis of this paper, I probably have to revise that opinion, but what do any CDD experts reading this post think?

June 7, 2018

6 ways Local NGOs in Ghana are facing up to Shrinking Aid Flows

Local NGOs in developing countries face numerous threats, from government crackdowns to dwindling aid budgets.  How are they responding? In a recent paper for VOLUNTAS: the International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations (Open Access – yay!), Albert A. Arhin, Emmanuel Kumi and Oxfam’s Mohammed-Anwar Sadat Adam interviewed 65 people in Ghanaian NGOs, who face less overt repression than in many countries, but falling aid budgets as Ghana graduates out of Low Income status (a tipping point for a lot of aid flows). The paper identified that NGOs are pursuing six main strategies:

How are they responding? In a recent paper for VOLUNTAS: the International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations (Open Access – yay!), Albert A. Arhin, Emmanuel Kumi and Oxfam’s Mohammed-Anwar Sadat Adam interviewed 65 people in Ghanaian NGOs, who face less overt repression than in many countries, but falling aid budgets as Ghana graduates out of Low Income status (a tipping point for a lot of aid flows). The paper identified that NGOs are pursuing six main strategies:

Eggs-in-Multiple-Baskets: diversifying their donors to reduce vulnerability to a sudden end to aid flows, but also trying to tap directly into public giving (both local and international), and setting up social enterprises and subsidiary firms like consultancies to try and cross subsidise their activities.

Cost-Cutting: cutting back both staff and areas of operation

Strength in Numbers: making more use of networks and coalitions both to work together in areas such as advocacy, but also to collectively seek funds from the big donors

Form long term partnerships, eg with Memoranda of Understanding, to try and reduce the volatility of funding, eg deepening relationships with particular international NGOs

Credibility-Building Strategy: ‘organisations paying serious attention to systems and practices that make them credible, trustworthy and believable to donors, private firms, government agencies and even individuals across the country who might, through such credibility, support their work.’ That can mean greater transparency, better management systems and investing more in building relationships with donors.

Visibility-Enhancing Strategy: ‘activities that make them visible (regarding what they do) and easily recognised by actors such as donors, private firms and governments.’ And ‘seeking to create a good public image about themselves and to assert their expertise and authority in particular sector of fields of knowledge.’

The paper concludes that ‘NGOs are not passive victims of the changing aid landscape’, which is good to hear, though hardly surprising (did anyone think they would be ‘passive victims’?).

The paper concludes that ‘NGOs are not passive victims of the changing aid landscape’, which is good to hear, though hardly surprising (did anyone think they would be ‘passive victims’?).

But what’s weird is that there is almost no discussion of potential trade-offs and downsides in these survival strategies. Some of them (eg diversifying funding, shifting from aid to domestic sources of funding, transparency, reducing waste) seem like just good practice, but several others could lead to things like self-censorship to stay ‘credible’ with potential funders, even when those funders are also targets for influencing, or mimicking northern donors’ fondness for ‘badging’ their activities with yet more aid billboards going up around the developing world. – i.e. conflicts of interest abound.

Maybe that’s for the follow up research?

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers