Duncan Green's Blog, page 96

May 9, 2018

Insurance hits peak hype in the aid & development biz – but what do we really know?

Guest post from Debbie Hillier, Oxfam’s Senior Humanitarian Policy Adviser

There is a lot of enthusiasm for insurance right now in a range of different sectors

humanitarians are particularly excited, hoping this is a quick win to fill the aching chasm in humanitarian aid

climate change experts hope it will be an easy fix for the problems of Loss and Damage and polluting countries hope that this will avoid the insistent calls for compensation

in the financial inclusion sector, it’s the Next Big Thing after savings and credit.

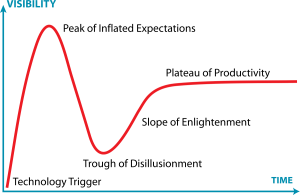

Donors are exhilarated by the opportunity to leverage the private sector; insurers are revelling in the potential market opportunities. But I suspect we are at the peak of the hype curve (left). We may want to learn the lessons of micro-credit, which was also once at this heady peak but experience over several decades now finds “modestly positive, but not transformative, effects.”

The Hype Curve

Yes, insurance clearly does have a role, but as with all things we need to carefully understand its limitations. I have been trying for several months to try and get to a more nuanced conversation about insurance: perhaps one small success has been changing the subtitle of the Payout for Perils report from ‘how insurance can solve the problems of emergency aid’ to ‘radically improve.’

Insurance advocates are careful to say that it is not a panacea/silver bullet and it needs to fit within a comprehensive risk management framework, but too often this feels a little empty. Precisely how should it fit within a comprehensive framework, and more significantly, what if there isn’t one? When faced with flood risk, solutions could include ensuring that vulnerable people have insurance, or the government has a line of credit available for response, or investment in strengthening flood defences, or implementing construction and planning controls or providing early warning and evacuation systems. A clear-sighted analysis of all of these options and others needs to be undertaken, and help is needed on how to do this.

Advocates say that insurance instils ‘risk discipline’ and incentivises risk reduction. Whilst clearly possible and eminently plausible, the empirical evidence in developing countries isn’t really there yet. One study reviewing 27 flood insurance schemes found few links and less success. Most examples of insurance schemes that supported risk reduction quoted in a report written ten years ago no longer seem to be functioning – which in itself is illustrative.

Most insurance experts say that standalone microinsurance is not suitable for the poorest people who have little income, many risks and few assets to insure – yet no one seems to have worked out what the threshold is. Surely bringing some clarity here would be a quick win, and would allow the development and promotion of other mechanisms that do work for people in extreme poverty.

Perhaps the next argument is whether insurance could be a useful tool for middle-income people, thereby freeing up

yeah, right

government and donor resources for people in poverty? While attractive in principle, the lessons from health insurance is that this leads to a stratification of services and support, such that inequality is deepened further. And this certainly seems to be the case for livestock insurance in Mongolia – the designers of the scheme knew it was better placed for the middle-sized herders and pushed for a social protection scheme for the poorer ones, but this did not materialise. Inequality looks to have increased.

What frustrates me is the lack of investment in M&E – yes, we need to explore new and innovative schemes, take a punt on promising ideas, but this must come with solid learning, evidence building and robust M&E. And up to now, this has been notably lacking. While it is perhaps not surprising that insurance companies have neither the skills nor interest in considering the impacts on gender, equity, social cohesion, female-headed households, the landless, or whether there are negative unintended consequences – the donors funding these schemes really should.

I feel pushed into being negative about insurance, purely to balance out all the over-excitement from elsewhere. A classic response to this is – yeah, but you have insurance! Well yes, but firstly, my insurance is not based on models, and therefore is not subject to ‘basis risk’ which bedevils many schemes in developing countries. And secondly, I use insurance where I believe it is cost-effective in addressing my risks – eg for my household possessions but not for my dog’s vet bills. The high excess and rising costs of insurance as my dog gets older mean that the cost/benefit argument just doesn’t stack up for me (I am however putting money aside – saving – for the likely health bills).

A sensible approach to get us to the hype curve’s ‘Plateau of Productivity’ would involve a much increased focus on:

A sensible approach to get us to the hype curve’s ‘Plateau of Productivity’ would involve a much increased focus on:

M&E for impact, not just coverage – this requires investment, perhaps adopting the Oxfam standard of a minimum spend of 5% of programme costs on M&E.

Developing a tool to evaluate both risk reduction and risk finance options, enabling governments (national and local) to better understand costs, benefits and opportunity costs of a range of measures, enabling appropriate investment. Perhaps building on this.

Ensuring quality. The G7 has a target to get insurance to 400m more poor and vulnerable people in developing countries by 2020, but it could well be argued that this target on quantity – without an equally clear focus on quality – is premature.

Pro-poor business models – such as cooperatives/mutuals and putting the missing ‘p’ into Public-Private-People Partnerships.

Who is going to pay the premiums. Insurance is not free money. It is sobering to note that Haiti’s maximum payout for cyclones under CCRIF is $35m whereas a ‘more adequate’ coverage of $328m, according to the World Bank, would require annual premiums of $15m – any offers to pay?

Even so, the bottom line is that in our rapidly-warming world, much greater investment is needed in proven solutions of risk reduction and adaptation.

May 8, 2018

5 ways to build Civil Society’s Legitimacy around the world

Saskia Brechenmacher and Thomas Carothers, of the Carnegie Endowment for International

Saskia Brechenmacher and Thomas Carothers, of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, introduce and summarize the insights from their new collection of essays from civil society activists.

Peace, introduce and summarize the insights from their new collection of essays from civil society activists.

Pressure on civic space keeps increasing around the world, driven by the toxic mix of rising authoritarianism, growing populism, and wobbly democracy.

Battles over legitimacy are central to this trend. Powerholders don’t just attack specific civic groups carrying out activities they find bothersome. They go after the legitimacy of civil society itself, questioning what right unelected civic groups have to insert themselves into policy debates and dismissing civic groups as inauthentic elite actors working at the behest of foreign powers. Such attacks often find resonance among citizens sympathetic to larger currents of nationalism and xenophobia, and feed on real weaknesses within civil society. For example, sociopolitical polarization in many countries weakens solidarity among civic groups, rendering them more vulnerable to accusations of partisanship.

Pressed to defend their very existence, civic groups and their supporters face a question they often neglected in earlier, less hostile times—from where does civil society derive its legitimacy? Or more bluntly, how is legitimacy earned? In donor and policy debates, two ideas repeatedly re-surface—that civic groups need to develop wider constituencies and more local funding. A more comprehensive examination has been lacking.

To go deeper, we asked a set of civic activists and analysts from a diverse set of places, such as Colombia, Kenya, Thailand, and Turkey, what sources of legitimacy they draw on in their work and what approaches have proven most effective at countering negative government narratives and building public support.

To go deeper, we asked a set of civic activists and analysts from a diverse set of places, such as Colombia, Kenya, Thailand, and Turkey, what sources of legitimacy they draw on in their work and what approaches have proven most effective at countering negative government narratives and building public support.

Not surprisingly, no silver bullets turned up. Yet taken together, our contributors suggest a range of potential legitimacy sources that organizations can cultivate.

First, civic groups can gain legitimacy from who they are, their identity as societal actors. For example, organizations based in and led by the communities they seek to represent are often more difficult to dismiss as illegitimate than those that advocate on behalf of others. In Guatemala, for example, the Center for the Study of Equity and Governance in Health Systems found that offering low-profile support to indigenous activist networks has proven much more effective than lobbying the government on their behalf. Of course, local rootedness is not necessarily a sufficient defense in hostile contexts. In Hungary, for example, grassroots organizations defending refugee rights have been key targets of the Orban government.

Leaders who enjoy local credibility nevertheless tend to be better positioned to fend off government smear campaigns. Tunisia provides a useful counter-example: extravagant lifestyles and wasteful spending by some Tunisian pro-democracy activists have damaged their links to potential supporters.

Second, civic organizations’ legitimacy is shaped by what they do, the issues that they work on. Not surprisingly, civic actors can build public support by working on issues that directly affect people’s lives—which may require reframing specific causes in ways that are more locally resonant rather than relying on international frameworks. For some groups, working in multiple areas has also opened up space to tackle more politically difficult topics. For example, when ActionAid came under attack in Uganda, it could point to achievements in areas such as health, education, and agriculture to make its case.

Civil society organizations also accrue legitimacy based on how they do their work. Three core principles stand out: downward accountability, transparency, and political independence. Downward accountability is crucial to ensuring local legitimacy. Transparency about objectives and methods—and “bringing your own house in order”—in turn can help counteract government accusations of corruption or subversion. In polarized political contexts, civic groups can take extra steps to avoid accusations of partisanship: embedding advocacy in international or domestic law, eschewing government funding, bridging cross-partisan divisions, and not taking sides in election campaigns.

Fourth, civic organizations draw legitimacy from those with whom they work. Our contributors highlight the  importance of building sectoral cohesion, bridging societal divides, and reaching out to new allies. In the United States, for example, a wide range of humanitarian aid organizations rallied behind the Islamic Relief Service when the latter was threatened in Congress, demonstrating the power of sectoral solidarity. In polarized societies, building stronger alliances may require overcoming legacies of mistrust and reframing causes in ways that ensure broader buy-in.

importance of building sectoral cohesion, bridging societal divides, and reaching out to new allies. In the United States, for example, a wide range of humanitarian aid organizations rallied behind the Islamic Relief Service when the latter was threatened in Congress, demonstrating the power of sectoral solidarity. In polarized societies, building stronger alliances may require overcoming legacies of mistrust and reframing causes in ways that ensure broader buy-in.

Finally, civil society organizations build legitimacy based on what impact they have. The feminist fund Mama Cash, for example, has purposefully invested in research examining the local impact of their work and leveraged external research to underscore the importance of its core mission.

In sum, multiple strategies exist for civic actors seeking to build legitimacy and defend it in the face of attacks by hostile governments or other actors. Not all of the strategies are available in every context. No one approach will necessarily beat back the attack dogs that hostile governments unleash. Yet given the punishing currents of the current global political moment, it is crucial for all civic actors and their international supporters to carefully think through the full range of actions they can take to meet the legitimacy challenge.

May 7, 2018

A day in the life of an Oxfam researcher – fancy joining the team?

Guest post from Deborah Hardoon (right)

Psst, want my job? This is my last week as Deputy Head of Research at Oxfam. It’s a role which is as fascinating as it is challenging. You get to work on important global issues, with brilliant and bright people from all over the world. For details on the role and responsibilities, here’s the job description (closing date 27th May). But if you want a window into what the job is really like, here’s a taster – a day in the life…

9:00am. Open emails

Usually there’s plenty of overnight traffic from the other side of the world. I have some questions from Amy, the Research Fellow who I manage in Myanmar. There are a few hours in the morning where we overlap, so I’ll get to those emails first. She’s written to let me know that she’s just had her abstract on inequality research in Myanmar accepted for an academic conference in the UK – it’s great to see her work reach audiences outside the country context. The three Research Fellows (Tin in the Philippines and Aromeo in South Sudan) are in their first year of an 18 month posting, jointly managed by the global research team and a content lead in the Oxfam country team. I established this programme to build in-country research capacity, the foundation for a strong evidence base for national programme and campaign work. It also ensures that national expertise and evidence informs our global work. As a pilot, we’re learning loads from the three Fellows in post about how to take this way of working forwards.

11:00. Inequality team meeting

Get an update on all the current policy and campaigning activities and share relevant research and evidence. Hot off the press, the Oxfam Malawi team have just published a national report. Some questions on the inequality statistics  used in the report have come in. I do some additional analysis of the data to inform Oxfam’s response. Some pretty striking data, when you look at the change in income per decile. I’m being asked lots of data-related questions on inequality. Despite many data gaps (particularly when it comes to disaggregating by gender and other horizontal inequalities), there is also much data to play with and a variety of ways to measure inequality. But in analysing data, recognising the gaps and limitations (such as under-reporting of top incomes) is key to understanding inequality, as is the politics of what gets measured and why.

used in the report have come in. I do some additional analysis of the data to inform Oxfam’s response. Some pretty striking data, when you look at the change in income per decile. I’m being asked lots of data-related questions on inequality. Despite many data gaps (particularly when it comes to disaggregating by gender and other horizontal inequalities), there is also much data to play with and a variety of ways to measure inequality. But in analysing data, recognising the gaps and limitations (such as under-reporting of top incomes) is key to understanding inequality, as is the politics of what gets measured and why.

13:00. Progress report on joint thought piece

Skype Call with Kaori in the private sector team, Chiara the inequality policy lead and Greg, our co-author from Finance Watch to discuss some feedback we have had on the paper we are writing together. The paper explores the relationship between the finance sector and inequality. This built on a think piece we wrote for the UK Financial Conduct Authority. We find that the relationship works directly, in the different products and rates offered to people based on their financial position, but also indirectly, through how money is created and global financial risk is managed.

This project has given me a fascinating insight into the financial sector and the impact that financialization has had on the wider economy. But the purpose of the project has also been to make these issues accessible to a non-technical audience. Because if finance remains impenetrable to everyone except those who work within the sector, it will continue to be oriented towards its own interests and those with the assets on which it depends. Instead, we argue, the sector has enormous potential to act as a level for progressive change, if it acts in the interests of society more broadly.

15:00. Webex with the IMF

I present remotely to the IMF on our Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index, together with our partners at Development Finance International. The Index scores and ranks 152 countries on the progressivity of their tax, spending and labour rights policies. The IMF have many questions and comments, ranging from the technicalities of specific indicators to the scope of the policies the Index covers. I was Oxfam’s research lead for this Index, published last year, ensuring rigour in the calculations used to analyse each component of the Index, and the technique we used to aggregate all the data into an index.

Last year’s index was a pilot, and we gathered loads of great feedback from Oxfam country offices and partners,  policy makers and academics and students from around the world. Last week I presented the Index virtually to the World Bank for their input, and this week it’s the IMF. All of the consultations will inform the next iteration of the Index, to make it an even richer source of data for civil society to use to hold governments to account on their policy choices.

policy makers and academics and students from around the world. Last week I presented the Index virtually to the World Bank for their input, and this week it’s the IMF. All of the consultations will inform the next iteration of the Index, to make it an even richer source of data for civil society to use to hold governments to account on their policy choices.

What a great job, hey! And if you ever need any support or guidance on any of this, then my/your boss Irene Guijt will always have your back. She’s a passionate do-er, with loads of inspiring ideas for innovative research projects, building research partnerships and making sense of what we know. All conveyed brilliantly in her straightforward (Dutch) style.

Here’s how Irene describes our ideal candidate: Precision, pragmatism and passion about inequality and economic development are your calling cards. You communicate clearly. You number crunch nimbly. You speak eloquently. You revel in working with others across the globe. Helping people get the best out their research efforts gives you a buzz. You’re already a top-notch thinker – and keen to dive into new angles on inequality, poverty and economic development. Your strategic mind makes you deliver well, at scale and on time. With an appetite for innovation, you’ve got robust and novel ways of analysis and communicating what can help reduce poverty.

So if you’re a bit of a data nerd, interested in inequality and enjoy making these issues come alive, then Oxfam would love to hear from you. Here’s the link again.

May 3, 2018

If you want to persuade decision makers to use evidence, does capacity building help?

This guest post comes from Isabel Vogel (

independent consultant , left) and Mel Punton (

Itad

)

, left) and Mel Punton (

Itad

)

Billions of pounds of development assistance is being channelled into research and science, with the assumption that this will help tackle global problems. But in many countries, decision makers don’t turn to evidence as their first port of call when developing policies that affect people’s lives. This problem has sometimes been framed as a lack of demand for evidence: decision makers don’t fully recognise the value that evidence can bring, and lack the skills to source, appraise and apply evidence effectively. But is this right?

In 2013, UK’s Department for International Development set up a programme to strengthen decision makers’ capacities to use evidence (discussed by David Rinnert and Liz Brower previously on this blog). Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence (BCURE) was a £15.7 million investment by the UK to build skills, incentives and systems for evidence use in government across more than 12 countries in Africa and Asia, and has recently come to an end.

So what did we learn about capacity building for evidence use?

Led by a team from Itad, the BCURE evaluation conducted almost 600 interviews over three years in Bangladesh, Kenya, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, South Africa and Zimbabwe to track what difference capacity building makes to evidence use. Although BCURE only ran for a short time, some important lessons jump out for future capacity builders (there are many more in the final evaluation report):

Figure 1. Summary of lessons from the evaluation

Evidence informed policy making is not the opposite of politicised decision making – we need to think and work politically to incentivise evidence use

There is a huge amount of literature suggesting that evidence use is inherently, unavoidably political. Policymakers don’t use evidence to inform decisions in a rational, linear way: research is just one part of the mix of considerations within the politicised, messy, institutional back-and-forth that we call the ‘policy process’.

So while there is a problem when civil servants don’t understand statistics or how to weigh up which sources are reliable, fixing these skills won’t help if there is no political space to bring evidence into decision making, and no incentives for senior decision makers to care about evidence, especially if it challenges politicians’ pet policies. We need to think and work politically when trying to promote evidence use.

On the surface the BCURE projects did this – they were all a good fit with government agendas around evidence-informed policy making, with some level of demand from senior leaders, and were tailored to align with ministry requirements through needs assessments.

But the interventions were often technocratic and would have benefited from more in-depth political economy

Good luck with that

analysis. BCURE had greater success where projects looked beyond superficial expressions of ‘need’, and located an entry point in a sector or government institution where there was existing interest in evidence, clear political (and financial) incentives for reform, and a mandate for promoting evidence use.

Sometimes this involved taking advantage of a window of opportunity for reform – for example decentralization in the health sector in Kenya, or a new Coordination and Reform unit in Bangladesh. It often required building on existing institutional credibility and relationships to gain a foot in the door; and nurturing relationships with individual champions who could act as internal sponsors for the programme, often because their own prestige was enhanced by being involved in the project.

Ultimately, we found that building capacities for evidence use was really about introducing institutional reforms – taking a wider systems view of how evidence is used, incentivised and reinforced throughout the government and parliamentary system by all the players –including by civil society to challenge ineffective policy decisions.

Changing behaviour requires more than training, and training lots of people does not result in organizational change

This seems obvious, but is worth repeating as so many capacity development programmes are built on this flawed assumption (see Lisa Denney’s post lamenting that $15bn in international aid is spent every year on training, with disappointing results).

All of the BCURE projects involved some kind of training on the importance of evidence, and how to access, appraise and apply research in their jobs. This was most successful when training linked up with other activities, which together pushed change at different levels of the system. For example, a training course might build trainees’ confidence and skills, which were then embedded through follow-up mentoring support, and through tools (such as policy development guidelines) that facilitated staff to do their jobs more easily.

An important factor was the extent to which applying evidence skills led to recognition from senior managers and career progression for trainees, or helped to mobilise donor resources for departments, which created incentives to further embed evidence use.

An important factor was the extent to which applying evidence skills led to recognition from senior managers and career progression for trainees, or helped to mobilise donor resources for departments, which created incentives to further embed evidence use.

Ultimately, whether or not training led to behavior change tended to depend on people’s immediate unit and the broader political environment being conducive to evidence-informed ways of working, as much as on the training design and implementation.

Finally – an obvious but crucial point – training needs to target people who have the scope to actually use the learning as part of their day to day work. BCURE showed that this is sometimes surprisingly difficult to achieve, e.g. where a training course is seen as a bonus to be allocated by managers, or linked to someone’s civil service grade rather than their actual job.

And if you want training to lead to organizational change through a ‘critical mass’ effect (an implicit but unrealised assumption across BCURE), you need to actively promote and resource it, e.g. through an explicit ‘training of trainers’ strategy, clustering trainees together within units to develop social connections to help each other act as a ‘focal points’, and seeing how evidence use can trigger performance incentives.

Capacity strengthening programmes should accompany change, not impose it

BCURE was most successful where projects ‘accompanied’ government partners in a flexible, collaborative way that promoted ownership, and strengthened civil servants’ capacities through ‘learning-by-doing’.

Accompaniment is not easy – it was often possible only where BCURE’s government partners already had a strong mandate and incentives to promote evidence use, or where BCURE had built up trust through previous activities that led to an invitation to closely accompany policy processes.

Accompanied reform processes in BCURE faced numerous blockages that had to be navigated, including corruption scandals, frequent staff rotations, competing interests, and changes in government priorities. For programmes to work in this way, there needs to be sufficient flexibility in the contracting model, to allow partners to respond nimbly to challenges and opportunities.

If it’s all about politics, should we bother building capacity for evidence use at all?

No-one is denying that skills and systems shortages are very real constraints to evidence use. And despite challenges, many of our respondents repeatedly told us that they need to be able to use evidence more effectively to develop credible policy solutions that can win political support and be steered through to implementation in order to actually deliver change. So there certainly is a need for capacity development, and not just in governments – BCURE strengthened national civil society actors as well as civil servants.

But BCURE brought home that using evidence is not just about technical skills – support needs to be politically informed, focus on changing incentives not just delivering training, and seek to accompany institutional reforms through collaboration over the long term, if we want to make a difference.

Of course, this is all easier in principle than it is in practice. DFID is taking the learning from the BCURE programme forward in the design of its forthcoming programme, Strengthening the Use of Evidence for Development Impact (SEDI) – so watch this space.

May 2, 2018

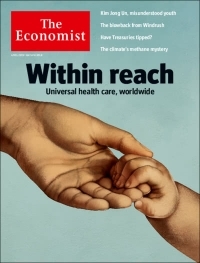

The Economist comes out in support of Universal Health Care – here are the best bits

This week’s Economist magazine leads on the case for Universal Health Care, worldwide. That’s a big deal – the  Economist is very influential, can’t possibly be accused of being a leftie spendthrift, and the case it makes is powerful. A couple of non Economist readers asked me for a crib sheet of the 10 page report, so here are some of the excerpts that caught my eye:

Economist is very influential, can’t possibly be accused of being a leftie spendthrift, and the case it makes is powerful. A couple of non Economist readers asked me for a crib sheet of the 10 page report, so here are some of the excerpts that caught my eye:

The Basic Case: ‘800m people spend more than 10% of their household budget on health care, and nearly 100m are pushed into extreme poverty (defined as having less than $1.90 a day to live on) every year by out-of-pocket health expenses.

Universal health care is both desirable and possible, even in low-income countries. Some countries achieved near-universal coverage when they were still relatively poor. Japan reached 80% when its GDP per person was about $5,500 a year. More recently, several developing countries have shown that low income and comprehensive health care are not mutually exclusive. Thailand, for example, has a universal health-insurance programme and a life expectancy close to that in the OECD club of mostly rich countries. In both Chile and Costa Rica income per person is roughly 25% of that in the United States and health spending per person just 12%, but life expectancy in all three countries is about the same. Rwanda’s GDP per person is only $750, but its health scheme covers more than 90% of  its population and infant mortality has halved in a decade.

its population and infant mortality has halved in a decade.

It is becoming increasingly clear that better health can lead to higher incomes, as well as the other way around. Economists at the World Bank used to call spending on health a “social overhead”, but now they believe that it speeds up growth.

Aid: Shifts in the burden of disease present dilemmas for international organisations. Though most spending on health in poor countries comes from government budgets and out of consumers’ pockets, an average of just over a third in 2016 was paid for by aid. Health aid in that year added up to $37.6bn. A little over half of that came from three sources: the American government (34.0% of the total), the British government (10.9%) and the Gates Foundation (7.8%). The vast majority of this aid goes on child and maternal health and on infectious diseases, especially HIV, which makes up fully 25% of the total. Non-communicable diseases account for just 1.7%.

“Improving global health is no longer primarily about combating infectious diseases,” says Lawrence Summers, who as the World Bank’s chief economist in the 1990s did much to advance its work on health. That view may strike many health experts as premature when malaria, tuberculosis and HIV are still killing millions every year, but the epidemiological shift will ensure that ever more resources will be consumed by chronic conditions. Policymakers will have to think carefully about which health services to prioritise, and how best to supply them.

In many developing countries people get their health care mostly from informal private providers such as drug shops or unqualified practitioners. In India, informal providers account for three-quarters of all visits. The figures in other countries are similar, if mostly less extreme: 65-77% in Bangladesh, 36-49% in Nigeria and 33% in Kenya. Often these markets exist side by side with public-sector providers who rely on patients paying for drugs and tests, as in China, despite a spate of recent regulations.

Other developing countries provide much better care at low cost. An exemplar is Costa Rica, whose model shows the benefit of high-quality primary health care. This is often ignored as countries splurge on big hospitals. “Primary care is not heroic,” explains Asaf Bitton of Ariadne Labs, “but it works well.” Between 1995 and 2002 Costa Rica established more than 800 “Equipos Básicos de Atención Integral de Salud”, or integrated primary-health-care teams, each looking after 4,000-5,000 people.

Before the programme was in place, just 25% of Costa Ricans had access to primary health care; by 2006 the share had risen to 93%. It was introduced in stages, which enabled researchers to assess its impact. A study in 2004 found that for every five years it was in place, child mortality declined by 13% and adult mortality by 4%, compared with areas not yet covered. Another study estimated that 75% of the gains in health outcomes resulted from the reforms.

Mental Health: According to the world mental-health survey conducted by the WHO, between 76% and 85% of people with serious mental disorders had received no treatment in the previous year. Low-income countries spend an average of just 0.5% of their health budgets on mental health, with the vast majority of the money going on hospitals that are more like asylums. And mental-health spending made up just 0.4% of global aid spending on health between 2000 and 2014.’

Surgery: Nine in ten people living in developing countries do not have access to “safe and affordable” surgical care, according to a report in 2015 by the Lancet (see map). Surgery may seem something of a luxury if funds are tight, but the consequences of not having access to it are profound. In 2010, 17m lives were lost from conditions needing surgical care, dwarfing those from HIV/AIDS (1.5m), TB (1.2m) and malaria (also 1.2m). Roughly one-third of the global disease burden measured by DALYs is from conditions requiring surgery.’

according to a report in 2015 by the Lancet (see map). Surgery may seem something of a luxury if funds are tight, but the consequences of not having access to it are profound. In 2010, 17m lives were lost from conditions needing surgical care, dwarfing those from HIV/AIDS (1.5m), TB (1.2m) and malaria (also 1.2m). Roughly one-third of the global disease burden measured by DALYs is from conditions requiring surgery.’

User Fees: In the 1980s and 1990s many health economists were relaxed about out-of-pocket payments, also known as user fees. The World Bank saw them as a way of making sure money was not wasted, and of helping health-care consumers hold providers to account. There is merit to this argument. Research by Jishnu Das of the World Bank found that when Indian health workers saw patients in their private clinics, they spent more time with them and asked more questions than when the same health workers saw patients in public clinics.

Yet that does not make it a good idea to rely mostly on user fees to fund a health system. They stop those who need care from seeking it. Concerns that users will consume too much health care unless they have to pay are overblown. And when people are not getting vaccinated to save a few cents, others suffer, too.

Out-of-pocket payments are also “cannonballs of inefficiency”, says Timothy Evans of the World Bank, which is now sceptical about user fees. If spending is pooled, it can insure more people against the risk of ill health and put pressure on providers to cut prices. Of the $500bn generated globally by user fees every year, the World Bank estimates that 40% is wasted.

How to Get There

Countries that want to expand their coverage have taken two distinct approaches. The first is to start by covering a small group of workers in depth and work outward from there, adding workers from other industries as you go along. Inevitably, though, this leaves groups of people without insurance, and those with coverage have little incentive to help them get it.

Countries that want to expand their coverage have taken two distinct approaches. The first is to start by covering a small group of workers in depth and work outward from there, adding workers from other industries as you go along. Inevitably, though, this leaves groups of people without insurance, and those with coverage have little incentive to help them get it.

The second, better approach is to cover more people but start with a limited range of benefits. In 2004 Mexico introduced Seguro Popular, a scheme that covered 50m people in the informal sector. Studies suggest that Seguro Popular has drastically reduced the number of Mexicans facing catastrophic health costs and reduced infant mortality.

Rwanda is another example. More than 90% of its people have health insurance, mostly under its Mutuelles de Santé policy that gives access to community health services as well as various treatments partly paid for by the Global Fund. Most visits involve a small co-payment and there is a tiered system of premiums, with exemptions for the poorest people. The scheme has helped cut out-of-pocket expenditure and improved health outcomes. Between 2000 and 2011, for example, the mortality rate for tuberculosis fell from 50 to 14 per 100,000 people.

In Thailand the Universal Coverage Scheme replaced two existing schemes for the rural poor and for informal workers. Today 98% of Thais have health insurance. The scheme was accompanied by reforms such as incentives for doctors to work in rural areas and extra payments to hospitals to take on patients. Crucially, Thailand’s Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Programme, a quasi-governmental body, analyses the cost-effectiveness of treatments, as well as ensuring that cancer cases such as Ms Waree’s are dealt with sympathetically. Despite the increased coverage, Thailand still spends only 4% of its GDP on health, about the same as it did 20 years ago. That works out at roughly $220 per person per year.

Another option is to expand the tax base in poorer countries. Possible candidates are taxes on extractive industries and on goods harmful to health such as tobacco, alcohol and air pollution. That would not only raise money but have great public-health benefits. Energy subsidies could also be curtailed; some poor countries, including Bangladesh, Indonesia and Pakistan, spend more on these than they do on health and education.’

Perhaps because I’m not a health policy wonk, this all looks great to me, and massively important that it is The Economist saying it. But I assume I’m missing the counterarguments and critiques – over to you for those .

May 1, 2018

Book Review: Why We Lie About Aid by Pablo Yanguas

Guest post by Tom Kirk, of the LSE’s Centre for Public Authority in International Development

Every so often you read something that brilliantly articulates an idea or issue you have been struggling with for a while, but could not properly capture. Why We Lie About Aid is one of those books. Full of pithy quotes, punchy anecdotes and insightful case studies, it draws upon an eclectic mix of ideas from across the social sciences to craft an argument that the public and institutional discourses surrounding aid and development interventions are reductive to the point of self-harm. That is both because they make aid spending a political football and because they force practitioners to focus on what can be measured. This prevents donors from seizing opportunities for transformational change in recipient countries and does a disservice to reformers who could use their support in contentious political struggles.

Yanguas, a practitioner and academic, begins by stating that he agrees with much of the criticism levelled at aid and development by the likes of James Ferguson, Tania Li and William Easterly. Yet, he does not subscribe to Dambisa Moyo’s conclusion that the system as a whole is ‘dead’. This is a defining feature of his approach, which is as much about showing how aid can drive longer-running transformational ‘episodes’, as it is explaining the reasons for its failings. However, before getting to this, he devotes the book’s first two chapters to grounding aid interventions and organisations in the politics of their donor countries. This allows him to show how aid can variously be the darling of, or scapegoat for, both right and left leaning politicians (think of David Cameron’s commitment to 0.7% and George Bush’s HIV/AIDS programmes). This arises because aid currently has no permanent electoral constituency past those that work in the sector and a small number of committed idealists. This makes if perfect fodder for politicians looking either to prove their credentials as humanitarians by increasing budgets or as fiscal disciplinarians by slashing them and imposing rigorous auditing procedures.

The latter, Yanguas argues, has been the driving force behind a push towards the ‘results’ and ‘value for money’ agendas amongst some donors in recent years. Although taxpayers have a right to expect that their money be well spent, the contemporary need to quantify programmes’ impacts focusses practitioners on quick, technical wins or low hanging fruit, such as infrastructure and service delivery programmes. This is more of a concern now that the payment of practitioners’ own contracts with donor agencies often relies on neatly demonstrating programmes’ successes. The effects of this can be seen within the public documents that aid organisations produce, which are  stripped of political conflicts and of programmes’ failures, thereby removing the chance for honest conversations about the obstacles to development and negating opportunities for learning lessons. It is also present in evaluations’ focus on programmes’ quantifiable outputs, rather than their wider societal or political outcomes. Yanguas argues that this leaves ‘donor publics’ (tax payers) with a superficial understanding of aid and forces the use of tools such as political economy analysis to the margins of programmes, where they cannot easily support ongoing interventions.

stripped of political conflicts and of programmes’ failures, thereby removing the chance for honest conversations about the obstacles to development and negating opportunities for learning lessons. It is also present in evaluations’ focus on programmes’ quantifiable outputs, rather than their wider societal or political outcomes. Yanguas argues that this leaves ‘donor publics’ (tax payers) with a superficial understanding of aid and forces the use of tools such as political economy analysis to the margins of programmes, where they cannot easily support ongoing interventions.

The book’s strongest chapters are the case studies of efforts to support anti-corruption bodies in Sierra Leone and Liberia. They are rich in detail and told through a persuasive style that moves back and forth between debates in the social sciences and events on the ground. For Sierra Leone, Yanguas shows how the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development’s (DFID) long engagement with the country’s Anti-Corruption Commission, its commitment to putting out sometimes explosive data and its location outside of the wider bureaucracy’s compromised accountability structures gradually changed what citizens expected of their political elites. For Liberia, he shows how an ever-expanding coalition of donors were, somewhat unwillingly, drawn into the country’s political conflicts through their sponsorship and tutelage of the General Auditing Commission. It was, however, ultimately unwilling to defend the Commission’s work when its head was replaced with an ally in 2011, overturning years of gains. In both cases, Yanguas shows how key individuals drove reforms with the support of donors, often at great risk to themselves, and how their combined actions had widespread, mostly unmeasurable, political ramifications: ‘whatever form aid takes, it will always have a profound effect on local actors, legitimising some and delegitimising others’.

The penultimate chapter further explores the ongoing struggles within donor organisations to ‘think and work  politically’. It covers the emergence of bottom-up movements (mainly the PDIA and DDD groups) to rethink how aid is understood and delivered, and how they are increasingly being taken seriously. Most interestingly, he shows how DFID has, somewhat subversively, financially sponsored outfits within the notoriously technical World Bank to promote more politically attuned ways of approaching developmental challenges. In a startling later section, Yanguas turns his attention to the contribution of academics routinely celebrated by development studies departments such as econometrician Daron Acemoglu and anthropologist Tania Li. He argues that their insights have very little practical application for ongoing reform processes in developing countries; something he declares ‘an abdication of the legitimate role that development scholars can play in advising officials or engaging in the public debate on aid’.

politically’. It covers the emergence of bottom-up movements (mainly the PDIA and DDD groups) to rethink how aid is understood and delivered, and how they are increasingly being taken seriously. Most interestingly, he shows how DFID has, somewhat subversively, financially sponsored outfits within the notoriously technical World Bank to promote more politically attuned ways of approaching developmental challenges. In a startling later section, Yanguas turns his attention to the contribution of academics routinely celebrated by development studies departments such as econometrician Daron Acemoglu and anthropologist Tania Li. He argues that their insights have very little practical application for ongoing reform processes in developing countries; something he declares ‘an abdication of the legitimate role that development scholars can play in advising officials or engaging in the public debate on aid’.

Yanguas concludes with a rallying cry to reinterpret aid as ‘contentious development politics’ or, put another way, as an asset for disrupting entrenched elites. This is what I have long been struggling to articulate. Indeed, he is surely right that if we want to secure the future of aid and development, and ensure it has the potential to contribute to transformative change, we must begin with our own discourses around it. To do so, Yanguas argues we should agree that both more markets and more state would be a good thing in most developing countries, thereby moving beyond tired left-right debates, and we should frame this as a moral imperative rather than a utilitarian calculation based on value for money. Abroad, we must support reformers, giving them the diplomatic cover and legitimation required to push through changes that threaten to upset debilitating status quos. We also must acknowledge that their actions and successes are unlikely to be measurable within five-year programme spans. This requires new ways of judging their intended and unintended impacts, with an eye to how they change others’ political calculations. Anything less, Yanguas argues, would be to let down brave individuals in difficult contexts and to continue to tell ourselves lies about the thing we call aid. I suggest that to get the ball rolling you should leave this book everywhere, from your friend’s bedside table, to DFID’s tea-room and the doorsteps of the Daily Mail.

April 30, 2018

Mark Goldring on how to maximise the impact of business on poverty and injustice

Guest post from

Mark Goldring

, Oxfam GB’s Chief Executive

Last week I introduced an Oxfam event at which Paul Polman of Unilever and a number of proponents of social enterprises came together to explore what kind of new business models we need to help beat poverty for good.

My starting point was that business has played a massive part in reducing extreme poverty, certainly more than that of charities and aid donors combined, and is fundamental to finishing the job. Many business leaders and employees have shown a strong personal commitment to reducing poverty, as have investors. Larry Fink, the CEO of Blackrock, recently stated in an open letter to CEOs, “To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society.” And when the world’s largest investor says it, even the sceptics begin to listen.

Many business leaders are genuinely interested in ensuring the benefits of wealth creation are shared more fairly. However, even the most committed CEOs and companies face barriers and disincentives due to the prevalence of models of business and finance that put a disproportionate emphasis on maximising shareholder value. Oxfam’s recent report, Reward Work Not Wealth, describes how the substantial economic growth over recent years has disproportionality accrued to those who already have it; around 80% of new wealth has gone to the richest 1% of the world’s population. Those in lower paid and informal employment have seen little gain in income and none in wealth. Unless we reverse this, we won’t hit our SDG target of ending extreme poverty and will leave the poorest behind as parts of society get richer.

Oxfam’s research and experience points to the potential and need for businesses that are structured so that farmers and waged workers have a greater say in decisions, and get a more equitable share of the value created. A recent Oxfam report, Fair Value showcases examples from food supply chains of multi-national companies, as well as cooperatives and social enterprises, which address such issues as contracting arrangements and fair pricing. Looking at business arrangements through the lens of how they impact differently on women and men can help overcome gender-specific barriers to women’s economic empowerment and enable them to benefit more from markets.

Oxfam’s research and experience points to the potential and need for businesses that are structured so that farmers and waged workers have a greater say in decisions, and get a more equitable share of the value created. A recent Oxfam report, Fair Value showcases examples from food supply chains of multi-national companies, as well as cooperatives and social enterprises, which address such issues as contracting arrangements and fair pricing. Looking at business arrangements through the lens of how they impact differently on women and men can help overcome gender-specific barriers to women’s economic empowerment and enable them to benefit more from markets.

Our report, and the input at the seminar from Sophi Tranchell, CEO of Divine Chocolate and Lisa Dacanay, President of the Institute for Social Entrepreneurship in Asia, as well as Paul Polman, show us such approaches are scaleable, replicable, can be extended to cover areas of the chain of production where more value is added, and that they can be linked into the supply chains of the biggest businesses.

The challenge now is for companies and their investors to more generally apply this thinking about how to respond to the needs of a wider group of stakeholders than shareholders, and for governments to consider how best to support and encourage this.

I see a range of ways, of which new business models are perhaps the least developed by big business, that will maximise the impact of business on poverty and injustice.

In brief these would include:

Recognise the difference between a legal minimum wage and a living wage. Work together with other likeminded businesses and governments towards this. The government in Ecuador garment industry in Cambodia and tea growers in Malawi have shown such progress is possible.

Look at wage differentials and extremes of pay and reward more generally. Use executive incentives to reward social and environmental performance. Challenge (often gendered) social norms that value and reward individual’s contribution to a firm’s success in a vastly different and unfair way.

Look beyond direct employees, right along the supply chain. The further along you go, the more exploitation

you will find. Build partnerships with suppliers and don’t only rely on audit.

you will find. Build partnerships with suppliers and don’t only rely on audit.Explore gender dimensions in all elements of employment. Recognise that women less often benefit from job security, training, promotion and other opportunities and more often suffer exploitation. Act accordingly.

Commit to tax transparency, pay tax where profits are earned. Work collaboratively with governments in law and practice. Without this, poor countries will never raise the tax they need to be less aid dependent and pay for much needed public services that disproportionally benefit the poor.

Actively engage with the communities affected by your operations. Recognise your impact on their lives, not just their jobs.

Explore new forms of corporate governance, such as stakeholder representation at board level, and engage with long-term investors on social and environmental issues to build support for investments in people and business rather than short-term cash returns. Use procurement approaches to favour suppliers who are structured to benefit wider stakeholders and parts of the community who may otherwise not benefit.

Most jobs and wealth will be created by small and medium sized national and local enterprises, but multinationals have a powerful role in setting standards, collaborating with government, innovating and leading a race to the top. Good business is fundamental to beating poverty, the better the business the faster we will crack it. And Oxfam is committed to play its part by engaging with business to explore and test ideas, challenge, cajole and collaborate to help make this happen.

April 29, 2018

Links I Liked

Got back from Costa Rica (fab holiday, here’s a taste of one of the more exciting moments – yep that’s me) to find a

Welcome home, you have 874 messages

Chaplinesque backlog of social media, emails, draft blog posts etc etc. That’ll teach me to go offline.

‘Economists tweet less, mention fewer people and have fewer conversations with strangers, and use less accessible language with more abbreviations and a more distant tone than a comparable group of scientists’.

Despite their increased level of public advocacy on good causes, ‘most US companies spent little or no money to lobby Congress in support of advancing social justice issues. Instead, they spent millions of dollars to push for lower taxes.’ A new Oxfam America report follows the money.

UK Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson gets a lesson in extreme manspreading from Uganda’s President Museveni.

UK Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson gets a lesson in extreme manspreading from Uganda’s President Museveni.

Why is nobody talking about prisons? Thought-provoking piece by Debora Zampier (one of my LSE students) on a neglected topic in development.

Lant Pritchett’s top six politically incorrect research findings in development economics ht Jake Allen

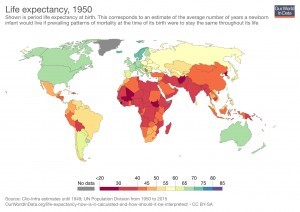

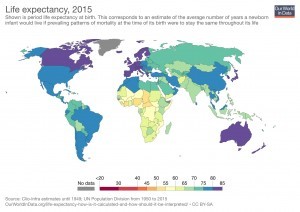

Feel-good number crunching from Max Roser. 1950 on the left (click to enlarge): Global life expectancy was 46 years. In Africa the

average was 36 In India 35 years 2015 on the right: Global life expectancy is 71 years. In Africa it is 61 (same as Japan in 1950) In India it is 68 (close to the healthiest country in 1950 – Norway with 72)

average was 36 In India 35 years 2015 on the right: Global life expectancy is 71 years. In Africa it is 61 (same as Japan in 1950) In India it is 68 (close to the healthiest country in 1950 – Norway with 72)

It’s not enough for research to be useful to policy actors; researchers must avoid being coopted and push for deeper change too. Nice piece from IDS’ James Georgalakis

“When the aging gorilla is confronted with the much more virile, new alpha-male, he shows submissiveness by grooming the alpha-male, but the gesture is actually a vain attempt by the old gorilla to humiliate his much younger rival.” — primatologist Jane Goodall ht Andrew Bradley. May not be an actual quote, alas.

April 26, 2018

Why donors ignore the evidence on what works, and transparency and accountability projects are a dead end. David Booth’s Non-Farewell Lecture.

ODI is always innovating, and earlier this week organized a non-farewell lecture for one of its big thinkers, David Booth. As  far as I could work out, this was a celebration of them stopping paying him (aka ‘retirement’), while he continues to work for them for free as a visiting fellow. Interesting business model.

far as I could work out, this was a celebration of them stopping paying him (aka ‘retirement’), while he continues to work for them for free as a visiting fellow. Interesting business model.

Anyway, for those that don’t know David’s work, he is an iconoclastic sociologist who, through big research projects like the Africa Power and Politics Programme, has spent decades pouring cold water on the half-baked buzzwords and unthinking fashions that flourish in the aid biz. We learned in the intro that he started on this course when he abandoned Trotskyism in the mid 80s – has anyone mapped the number and proclivities of lapsed trots in the aid sector? If not, why not?

David has been an influential voice in the critique of the failings of aid’s attempts in recent decades to implant Western style institutions in non-Western contexts. Phrases like ‘best practice’ and ‘good governance’ are useful alarm bells on this. Here he is (abbreviated) on what we have learned:

nb this is a Lant Pritchett slide, not one of David’s

‘If there is a single message that emerges from the best governance scholarship and research since the 1980s, it is that we know much less than we thought we did about the institutional arrangements that developing countries need….. We need a robust agnosticism about the forms of governance likely to contribute well to building economies and improving conditions of life in poor countries. The following things are clear:

The formal institutional arrangements that work reasonably well in OECD countries today are not exportable.

The institutional arrangements (formal and informal) that have helped countries break through into fast development are very diverse.

Historical path dependencies are really important, but, contra Acemoglu and Robinson, history contains more than just two typical long-term trajectories. There is much more to the global story than the persistence of ‘extractive institutions’ versus the spread of ‘inclusive institutions’.

Countries can and do make rapid and economic and social progress with institutions that, in overall terms, are seriously dysfunctional.

If there is a single takeaway from all of this, it is that ‘good’ institutions are neither easy to prescribe nor a precondition for successful developmental catch-up. Developmental catch-up invariably involves some borrowing ideas and technologies from abroad, but is never successfully led by borrowing. It is led by problem solving.’

If every serious scholar thinks this apart from Acemoglu and Robinson, (who he euphemistically categorized as ‘outliers’), have the donors done the decent, evidence-based thing? Ermm, not exactly.

‘That the immediate post-Cold War era should have featured a certain amount of liberal-democratic hubris is understandable. More striking is how durable much of the associated thinking has proven to be in the face of obvious disappointments and the build-up of the scholarly consensus against it.’

The discomfort zone for me and, probably, quite a few FP2P readers, is that David characterizes efforts to promote

Waste of time and effort?

transparency and accountability as a prime example of imposing irrelevant and inappropriate solutions. ‘Much of what lies behind the social accountability theme, like the content of most public sector capacity building, is a projection of solutions derived from experience in OECD countries onto the very different realities of developing countries. In other words, social accountability falls to the critique developed [that] it is profoundly solution-driven.’

I suspect he feels a bit that way (or at least ambivalent) about human rights too – we’ve crossed swords in the past about his apparent infatuation with Rwanda’s Paul Kagame. At least this time he moderated his usual dismissal of civil society organizations, acknowledging their role but adding ‘Civil Society Organizations are contributing to their own marginalization by doing these kinds of things that don’t lead anywhere (eg Transparency & Accountability – sorry about that, IBP).’

The way to fix aid is to really adopt ‘problem-driven iterative adaptation’ (PDIA), which means taking each letter in that clunky acronym seriously. In his view, donors have made more progress on the IA bit (Adaptive Management is all about iteration and adaptation), but have still not bought into problem-driven. The fudge has been ‘issue based’ programmes that say ‘we will use adaptive management techniques to fix governance/health/education’ – DFID’s vaunted SAVI governance programme in Nigeria would fit that bill. David thinks this falls short – what if you want to tackle poor quality education and find out that the real problem is bad roads, failing electricity or a low tax base? You need to be able to follow where the problem leads you.

Looks good, but is her placard in English just to please the donors?

Well fine, but then he’s basically saying aid donors should behave like governments, working across sectors and ministries, making trade-offs etc, which seems pretty impractical. Ironically, his weakest section was about why donors fail to act on this understanding – he puts it down to domestic donor politics and self-serving governance advisers who advocate institutional reform because that’s what they do. He even, true to his iconoclastic streak, advocated scrapping the unfortunately named GOSAC, the DFID governance team that funds lots of his work! But he didn’t really get into the broader realm of ideas and institutions, and in Q&A accepted that some of the most influential drivers of ‘best practice’ reforms are westernised leaders within developing country governments.

Conclusion? David makes people feel uncomfortable, sometimes goes too far, but who cares? In a sector full of groupthink, we need more iconoclasts like him, so I’m very glad he isn’t actually retiring.

April 25, 2018

The World Bank’s flagship report this year is on the future of work – here’s what the draft says

The World Bank’s 2019 World Development Report will be on ‘The Changing Nature of Work’ and It’s worth reading  because, even though this kind of annual flagship format feels a bit dated, WDRs are always a treasure trove of references and ideas, while what they miss out adds important insights into mainstream thinking in the aid biz. In late March a 140 page working draft went up online – kudos to the Bank for transparency, although they have come up with a particularly fiendish variant. They update the document every Friday, so whatever you write is instantly out of date. Some thoughts (on the early April version):

because, even though this kind of annual flagship format feels a bit dated, WDRs are always a treasure trove of references and ideas, while what they miss out adds important insights into mainstream thinking in the aid biz. In late March a 140 page working draft went up online – kudos to the Bank for transparency, although they have come up with a particularly fiendish variant. They update the document every Friday, so whatever you write is instantly out of date. Some thoughts (on the early April version):

The report addresses one of the big anxieties in current development circles (including on this blog) – will automation destroy the entry level jobs like garments, which have traditionally been the first rung on the ladder to development? Its response to this is remorselessly optimistic, occasionally tipping over into Policy on Prozac (‘the threat to jobs from technology is overblown’).

The basis for this optimism seems largely historic: ever since the Luddites, fear of technology has led to periodic mass anxiety about its impact on jobs, and yet those fears have never materialized. I have a lot of time for history, and wish economists as well as other disciplines would take it more seriously, so we should definitely take note.

‘Economists are notoriously bad at predictions’ says the WDR on previous prophecies of doom. Well true that, but

Indian car factory

that surely also applies to blindly assuming that future trends will rerun those of the past. The rate of change created by technology seems to be exponentially increasing – driverless cars, Artificial Intelligence, robots that can produce T-shirts, potentially wiping out Bangladesh’s main export industry overnight. To ride this wave, and make sure new jobs replace the extinct old ones, the WDR makes some heroic assumptions:

Firstly it claims that sectors like tourism, healthcare, care of the elderly and the gig economy will produce the new jobs necessary. The evidence for this seems to be little more than a lot of gee whizz anecdotes about start-ups and platforms around the developing world. To be fair, I’m not sure what more convincing evidence for this claim would even look like.

Secondly, just in case the market doesn’t step up on its own, the report proposes a central role for the state. The chapters on the state, and the call for a new social contract are fascinating. The WDR argues that ‘the three basic components of social protection systems – a basic minimum (with social assistance at its core), social insurance, and labor market institutions – can be adapted to help manage the strong headwinds of labor market challenges’. It praises the ‘recent spectacular growth in social assistance in developing countries [which is] a testament to a direction of travel towards ensuring such a minimum.’ There are 5 upbeat pages on the introduction of a Universal Basic Income, and a call for big increases in indirect taxation on carbon, digital companies and VAT (we’ll see if those survive sign off).

‘Where livelihood disruption is a new norm, even with the most resilient income support arrangements in place, active labor measures will become more important. Governments will need to ensure that first time job-seekers, workers who lose their jobs, or those who are working on low productivity jobs have access to proper counseling, training, information about new job opportunities, job search assistance, and migration support.’

Which all suggests that the Bank has moved massively on from the ‘state bad, market good’, 90s heyday of budget- slashing structural adjustment programmes. But as the diagram suggests, the reason for all this state activity is to amp up ‘labour market flexibility’. Ah, looks like we may be back to the 90s after all. ‘As all workers become better protected through reformed social assistance and insurance systems, labor markets can be made more flexible to facilitate work transitions….. stronger social protection systems can go hand in hand with more flexible labor markets. This flexibility would need to also be coupled with more effective job search support as well as new arrangements for expanding workers’ voice.’

slashing structural adjustment programmes. But as the diagram suggests, the reason for all this state activity is to amp up ‘labour market flexibility’. Ah, looks like we may be back to the 90s after all. ‘As all workers become better protected through reformed social assistance and insurance systems, labor markets can be made more flexible to facilitate work transitions….. stronger social protection systems can go hand in hand with more flexible labor markets. This flexibility would need to also be coupled with more effective job search support as well as new arrangements for expanding workers’ voice.’

I’ll come back to that ‘expanded workers’ voice’ bit in a minute, but first, what happens if the state is not up to the job? ‘If not updated, social protection and labor market policies will de facto leave many workers unprotected, with many firms and workers unable to adapt to the changing times.’

So there we have it, all this Panglossian optimism is based on the assumption of a pretty massive can opener – an effective, well intentioned state that can step in and smooth over the pain when people lose their jobs or get trapped in shitty zero hours contracts, and which can constantly retrain and reskill workers for new jobs as the economy evolves. All those unemployed van drivers are off to become coders and care assistants, right?

In other words, we seem to be squarely in ‘Getting to Denmark’ territory. If one of the key causes of poverty and conflict is an absent or malign state, what is the point of simply assuming a state as part of the proposed solution?

Now back to the workers’ voice. Trade unions are not completely absent, as they often are in World Bank documents, but they are presented largely as part of the dying Fordist order (the WDR even seems to think NGOs do a better job at giving voice to workers. Really?)

‘Labor institutions can no longer rely on the agency of the employer to provide protection to workers given the erosion of the traditional employer-employee relationship in more advanced countries and the irrelevance of this model for the rest of the world where informality dominates. Current institutions are ill-fitting to more flexible work and to new work arrangements.’

Promoting something akin to flexibility-on-speed, the WDR argues against minimum wages (it even argues that ‘labor unions—with a broader constituency and membership— are a better way to set wages’). It supports making it easier to dismiss workers (aka more flexibility), prefers state benefits to severance pay, and thinks zero hours contracts are just dandy. More from a trade union perspective here from a very unhappy Peter Bakvis of the ITUC.

OECD guide to the new technologies

Which brings me to the biggest blind spot of all – power. In the technocratic lala land of the WDR’s authors, the best results coming from the enlightened philosopher kings who are assumed to be in charge around the world stepping in to adroitly enable everyone to ride the technology tiger, as the market and its new gizmos rip through the status quo. What about imbalances in bargaining power, vested interests, political capture and their consequence, rising inequality? Not much on any of those, I’m afraid.

All in all, a fascinating document (when was the last time a WDR quoted Marx, Nehru and Lenin?), and well worth close study (I’m sure I’ve missed lots of gems). My overall take? History may be on the side of the optimists, but boundary conditions on growth, and technological acceleration could mean that this time really is different. Doomsters are always accused of crying wolf, but in the story the wolf comes in the end, and it’s not good news for the sheep.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers