Duncan Green's Blog, page 221

February 8, 2013

Bad Governance leads to bad land deals – the link between politics and land grabs

Ricardo Fuentes-Nieva (right) and Marloes Nicholls (left) crunch the numbers to find that big land investments sniff out countries with ‘weak governance’ – aka no accountability, no regulation, no rule of law, and a green light for corruption.

Ricardo Fuentes-Nieva (right) and Marloes Nicholls (left) crunch the numbers to find that big land investments sniff out countries with ‘weak governance’ – aka no accountability, no regulation, no rule of law, and a green light for corruption.

If you had bags full of money and wanted to buy land, where would you go for a good deal? If you’re only looking for ways to make a good profit and control your risk exposure, surely you would look for a place where you can influence the terms of the deal. This is the intuition behind the analysis published yesterday by Oxfam

The results of this analysis show that the global rush for land is mostly taking place in countries with weak governance. We analysed the link between national governance and large scale agricultural land deals by combining information from two important databases – the Land Matrix[i] and the World Governance Indicator (WGI) Project. To do this, we cross referenced Information on over 200 countries and territories from the two databases. Using the Land Matrix we aggregated the total number of deals reported in each country and their average size; from the WGI, we used estimates of Voice and Accountability, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law, and Control of Corruption. Once the two databases were merged, we analysed the link between the countries where large-scale land deals were – or were not – taking place and the four governance indicators for the period 2000 – 2011.

The results reveal a strong and significant link between land deals and weak governance. The majority (78%) of the 56 countries where land deals are taking place have below average WGI, and on average the pool of countries where land deals take place have 30% lower indicators than those without. These results are consistent over time.

A quick comparison between two countries shows that the land availability does not appear to be a significant factor in investment decisions. Guatemala, which scores below average on all four World Bank Governance indicators, has seen an estimated 87,000 hectares of land under deals between 2000 and 2011 despite high levels of hunger and malnutrition in rural areas. This is in stark contrast with Botswana which has a similar area of arable land per person (.11 and .13 hectares per person in Guatemala and Botswana, respectively) but which scored well above the average on World Bank governance indicators and did not record a single large-scale land deal in this period.

A quick comparison between two countries shows that the land availability does not appear to be a significant factor in investment decisions. Guatemala, which scores below average on all four World Bank Governance indicators, has seen an estimated 87,000 hectares of land under deals between 2000 and 2011 despite high levels of hunger and malnutrition in rural areas. This is in stark contrast with Botswana which has a similar area of arable land per person (.11 and .13 hectares per person in Guatemala and Botswana, respectively) but which scored well above the average on World Bank governance indicators and did not record a single large-scale land deal in this period.

These results are hardly surprising. Other studies have found similar results. Researchers at the IMF ( here and here), using a different database and methodology, have previously found that “countries with weak land sector governance are the ones most attractive to investors – at least as gauged by the number of land-related investments.” They suggest that investors might pick countries with weak governance because “it is easier to obtain land quickly and at low cost where the existing protection of land rights is weak, given that public protection may not matter to investors who can muster their own resources to defend their property rights.” Research by the World Bank found that deals were often formulated for the benefit of investors rather than the countries involved. They report that “in many cases the nature and location of lands transferred and the ways such transfers are implemented are rather ad hoc – based more on investor demands than on strategic considerations.”

Why Might Weak Governance be Good for Business?

The story behind land deals and weak governance is one of power imbalance and destitution. It’s a story where the interests of local communities are set aside to promote the interest of large investors.

There are usually three actors in any land deal – the investor, the local community who owns or uses the land and the government. The national government often acts as the intermediary (in wonk parlance, the government is the agent for the local community or the citizens, who are the principals). Weak governance – which basically reflects a gap between the interest of citizens and governments – enables investors to sidestep costly and time consuming rules and regulations, which for example, might require them to consult with affected communities. In countries where people are denied voice, where business regulations are weak or non-existent, or where corruption is out of control it might be easier for investors to design the rules of the game to suit themselves.

national government often acts as the intermediary (in wonk parlance, the government is the agent for the local community or the citizens, who are the principals). Weak governance – which basically reflects a gap between the interest of citizens and governments – enables investors to sidestep costly and time consuming rules and regulations, which for example, might require them to consult with affected communities. In countries where people are denied voice, where business regulations are weak or non-existent, or where corruption is out of control it might be easier for investors to design the rules of the game to suit themselves.

This analysis is only the first step towards a more in depth research project. Next steps include a more in depth analysis on the determinants of the number and location of deals (a double-hurdle estimation? suggestions appreciated from econometricians out there). We will also look at the geographical distribution of deals within countries to see if there is a link between the location of land deals in countries and socioeconomic indicators in those areas.

Land is such an important element of millions of people around the world that any issue related to use, access and ownership of it should be carefully analyzed. Agricultural investment is sorely needed but it should not be at the expense of people’s rights and access to land. There are potentially catastrophic implications of bad land deals. Poor accountability and regulation only means that people affected by land deals have fewer tools to defend their livelihoods and rights.

And if this all sounds a bit abstract, here’s what we’re talking about

February 7, 2013

So What do I take Away from The Great Evidence Debate? Final thoughts (for now)

The trouble with hosting a massive argument, as this blog recently did on the results agenda (the most-read debate ever on this blog) is that I then have to make sense of it all, if only for my own peace of mind. So I’ve spent a happy few hours digesting 10 pages of original posts and 20 pages of top quality comments (I couldn’t face adding the twitter traffic).

The trouble with hosting a massive argument, as this blog recently did on the results agenda (the most-read debate ever on this blog) is that I then have to make sense of it all, if only for my own peace of mind. So I’ve spent a happy few hours digesting 10 pages of original posts and 20 pages of top quality comments (I couldn’t face adding the twitter traffic).

(For those of you that missed the wonk-war, we had an initial critique of the results agenda from Chris Roche and Rosalind Eyben, a take-no-prisoners response from Chris Whitty and Stefan Dercon, then a final salvo from Roche and Eyben + lots of comments and an online poll. Epic.)

On the debate itself, I had a strong sense that it was unhelpfully entrenched throughout – the two sides were largely talking past each other, accusing each other of ‘straw manism’ (with some justification) and lobbing in the odd cheap shot (my favourite, from Chris and Stefan ‘Please complete the sentence ‘More biased research is better because…’ – debaters take note). Commenter Marcus Jenal summed it up perfectly:

‘The points of critique focus on the partly absurd effects of the current way the results agenda is implemented, while the proponents run a basic argument to whether we want to see if our interventions are effective or not. I really think the discussion should be much less around whether we want to see results (of course we do) and much more around how we can obtain these results without the adverse effects.’

There were some interesting convergences though, particularly Whitty and Dercon’s striking acknowledgement of the importance of power and politics, which are often assumed to be excluded from the results agenda. But what they actually said was

‘Understanding power and politics and how to assist in social change also require careful and rigorous evidence.’

True, but what about reversing the equation? Does understanding the role of evidence in development also require a careful and rigorous understanding of power and politics? They never fully address that crucial point, which is at the heart of Roche and Eyben’s critique.

Both sides (rather oddly, as acknowledged experts in their fields) decried the role of experts. Whitty and Dercon called for ‘moving from expert (i.e. opinion-based, seniority-based and anecdote-based) to evidence-based policy’. Ah, turns out that what is actually being suggested is a move from one kind of expert (practitioners) to another (evidence/evaluation).

Both sides (rather oddly, as acknowledged experts in their fields) decried the role of experts. Whitty and Dercon called for ‘moving from expert (i.e. opinion-based, seniority-based and anecdote-based) to evidence-based policy’. Ah, turns out that what is actually being suggested is a move from one kind of expert (practitioners) to another (evidence/evaluation).

As a non number-cruncher I also took exception to their apparent belief that only those who understand the methodological intricacies of different evaluation techniques are eligible to pass judgement. On that basis politicians would be out of a job, and only rocket scientists would get to pronounce on Trident.

There was also a really confusing exchange on the hierarchy of evidence. Whitty and Dercon show a surprising (to me at least) commitment to multi-disciplinarity: ‘Methods from all disciplines, qualitative and quantitative, are needed, with the mix depending on the context….. it is not a matter of just RCTs, but of rigour, and of combining appropriate methods, including more qualitative and political economy analysis.’

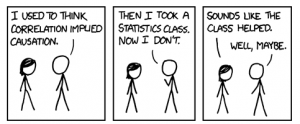

Music to the ears of the critics, but is it actually, you know, true? Everything I hear from evaluation bods is that DFID does actually see RCTs as the gold standard, and other forms of evidence as inferior. Roche and Eyben returned to the attack on this in their response, arguing that what Whitty and Dercon call the ‘evidence-barren areas in development’ are only barren if you discount sociology and anthropology, among others, as credible sources of evidence. By the way, Ed Carr has a brilliant new post on the (closely linked) clash between quants and quals, arguing that while quants can establish causation, only quals can explain how that causation occurs.

But the exchange did provide me with one important (I think) lightbulb moment. It was about failure. Whitty and Dercon were particularly convincing on this: the evidence agenda ‘involves stopping doing things which the expert consensus agreed should work, but which when tested do not’. This is a nice Popperian twist – the role of evidence is not to prove that things work, but to prove they don’t, forcing us to challenge received wisdom and standard approaches. This is indeed what I noticed about Oxfam’s recent ‘effectiveness reviews’ – if you find no or negative impact, then you (rightly) start to re-examine all your assumptions. But if this is the proper role for the evidence agenda, is it politically possible? By coincidence I have just read Ed Carr’s forceful critique of Bill Gates’ approach to evaluation, arguing that failure is often airbrushed out in order to safeguard funding and credibility. That seems a pretty fundamental contradiction.

The comments were just as thought-provoking. One of the key messages that emerged is the gulf between these debates and what those in  charge of gathering results in aid agencies actually face – highly constrained resources, crazy time pressure, and the need to deliver some (any!) results to feed the MEL machine. Oxfam’s Jennie Richmond reflected on the gap between theory and practice yesterday.

charge of gathering results in aid agencies actually face – highly constrained resources, crazy time pressure, and the need to deliver some (any!) results to feed the MEL machine. Oxfam’s Jennie Richmond reflected on the gap between theory and practice yesterday.

Commenter Enrique Mendizabal asked whether we are demanding a different role for evidence in poor countries than in our own.

‘In the UK, health policy is decided by a great many number of factors or appeals (evidence, sure, but also values, tradition, biases, political calculations, etc). We may complain about it but we accept that it is a system that works. But health policy for Malawi (or other heavily Aid dependent countries) is decided mainly by evidence (or what often passes as evidence at the time) and usually by foreign experts…. would we be happy with USAID funding a large evidence-based campaign to reform the NHS or our education policy?’

But he took his argument a step further – if the final decision should be left to the interplay of evidence (of different sorts), politics and negotiation, then DFID and other donors would be better advised to boost the ‘enabling environment’ for such debates and decisions by investing in tertiary education in developing countries:

‘strengthening economic policy debate is a more adequate objective than achieving policy change (even if it is evidence based).’

Commenter David highlighted a fundamental point that rather went missing in the initial exchange – how the results agenda does or doesn’t work in complex systems:

‘The results agenda approach tends, by presenting development as objectively knowable if broken down into discrete and small bits, todrive attention toward small, more easily measurable interventions to test, particular those that are suited to situations that are simple or complicated rather than complex. Current processes around evidence-based results fail to grapple with complex systems, interaction effects, and emergent properties that dominate most aid project landscapes.

A fundamental critique of the evidence-based revolution is that it actually diminishes efforts to get rigorous evidence about addressing complex challenges. We all want evidence, it’s a question of whether the current framing of “evidence-based” is distorting what types of evidence we gather and value. For those who think that the current emphases on methods to test what works are distorting how we value the evidence coming in (RCT=gold, qualitative methods=junk), this offers little other than platitudes about lots of other methods existing.

Personally, I would be a bigger proponent of the evidence-based revolution if it was coming to folks interested in power, politics, and development, and asking them what their questions are and what evidence might contribute to their work. Absent a learning agenda set to fit complex space and concern itself with power, it will continue to seem to me to be an instance of methods leading research – or searching for keys under the light rather than inventing a flashlight.’

To be fair, Roche and Eyben explicitly chose to focus on the politics of evidence, rather than the implications of complex systems (for example, the question of external validity in complex systems – or lack of it – raised by Lant Pritchett in our recent conversation.)

Final thoughts? After about 500 votes, the poll went narrowly to Whitty and Dercon (34% v 31% for Roche and Eyben, with a pleasing late rally for the ‘totally confused’ camp – my natural habitat). I think Chris Roche and Rosalind Eyben need to work on their communication style (more punchy, less abstract, more propositional). Chris Whitty and Stefan Dercon should give some examples of gold standard anthropological or sociological evidence to allay the doubts over their true commitment to multi-disciplinarity, and take the complex systems question more seriously.

A massive thankyou to all who took part, and please can you come back for another go in a year or so? This one isn’t going away.

February 6, 2013

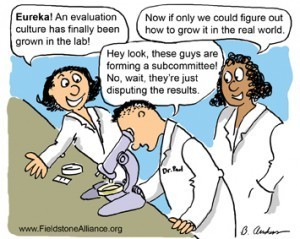

Theory’s fine, but what about practice? Oxfam’s MEL chief on the evidence agenda

Two Oxfam responses to the evidence debate. First Jennie Richmond, (right) our results czarina (aka

Head of Programme Performance and Accountability

) wonders what it all means in for the daily grind of NGO MEL (monitoring, evaluation and learning). Tomorrow I attempt to wrap up.

and Accountability

) wonders what it all means in for the daily grind of NGO MEL (monitoring, evaluation and learning). Tomorrow I attempt to wrap up.

The results wonkwar of last week was compelling intellectual ping-pong. The bloggers were heavy-hitters and the quality of the comments provided lots of food for thought. However, I was left wondering what it all meant for those of us who work in NGOs, trying to generate and learn from ‘evidence’ on a daily basis. I found myself unable to simply vote, so instead I blog….

The results and evidence agendas have brought some real benefits to NGOs in my view. First and foremost, it is important and right that those of us who claim to work in the interests of the poorest people in the world and are stewards of other people’s money, should set ourselves high standards for our own impact. In its simplest form the results agenda asks us to justify the trust others have placed in us, by demonstrating whether we are actually bringing about positive change. In Oxfam GB, accountability has long been held as a core organisational value. It is not the results and agenda that has got us thinking about how to capture and communicate our effectiveness, but it has provided a helpful additional push.

A further positive is that space has been created both within our own organisations and in the wider sector, to stop, listen and learn. MEL-istas (as Duncan calls us) 5 years ago struggled to get the ear of senior managers (let alone Ministers). But the results agenda has increased the stakes around MEL – encouraging organisations not only to increase investment, but also to listen to the findings coming from our own data gathering and analysis.

However, it has also increased the demand and the expectation, which are not easily met by all NGOs. In Oxfam GB the investment in MEL has increased over the last couple of years, undoubtedly, but still it is a real stretch to deliver the ever-more ambitious demands from donors, to develop tools to tell the story of our broader organisational impact, and to ensure that we are developing innovative ways of measuring cutting-edge programming areas, such as resilience, enterprise development and influencing.

And we are one of the largest international development NGOs in the UK. How much more difficult for the smaller and niche NGOs, or those who lack the flexible financing that permits investment in MEL and innovation? We are conscious in Oxfam that we and other large NGOs need to guard against distorting the NGO market place by pushing the boundaries on MEL and impact too far, and thereby creating expectations that cannot be met by everyone. Somehow we all need to keep our sights on a proportionate approach.

It is not just important to generate evidence, but also to use it properly. There is increased demand for serious, evidence-based conversations about what works. None of us can get away with decisions made purely on gut instinct, force of habit or ideological leaning. We are challenged by the ‘evidence’ question to collate and distil from the broad knowledge base we have at our disposal. And this has in some cases led to surprises. Rigorous studies, whether based on qualitative or quantitative methods, can challenge our preconceptions – showing us impact where we were not optimistic, or the opposite. The test, of course, comes when new programmes are designed. Will the body of evidence be applied – will we be able to find it for starters (in our often not-so-state-of-the-art knowledge management systems), and will it be politically acceptable in our own organisations to apply it to practice?

It is not just important to generate evidence, but also to use it properly. There is increased demand for serious, evidence-based conversations about what works. None of us can get away with decisions made purely on gut instinct, force of habit or ideological leaning. We are challenged by the ‘evidence’ question to collate and distil from the broad knowledge base we have at our disposal. And this has in some cases led to surprises. Rigorous studies, whether based on qualitative or quantitative methods, can challenge our preconceptions – showing us impact where we were not optimistic, or the opposite. The test, of course, comes when new programmes are designed. Will the body of evidence be applied – will we be able to find it for starters (in our often not-so-state-of-the-art knowledge management systems), and will it be politically acceptable in our own organisations to apply it to practice?

So, how can we use the results and evidence agendas and make them useful to us as NGOs? We need to do this in a way that a) is true to the actual work we do (which in the case of Oxfam includes a great deal of work that drives for political change and influencing) and b) does not distort decision-making away from the right decisions (i.e. what most suits the specific needs and opportunities of each context) in our efforts to be able to measure and communicate what we are doing.

One of the concerns raised in last week’s blog was that in some institutions, evidence becomes synonymous with impact evaluations, and even specifically with Randomised Control Trials. As all the bloggers agreed, the default use of one research method for interventions of all types is simply nonsensical. You only have to look at the enormous variety of the things we do in international development (from campaigning for policy change to delivery of bed-nets, from building of bridges to raising awareness of the rights of citizens) to realise that one approach is just not going to cut it.

Another challenge is that so much of what we do in international development is extremely hard to measure. How can we trace the input through to impact chain and clearly demonstrate the ‘on the ground’ changes we have brought about in people’s lives when the investment is in budget support or core funding? How can we reduce the process of a community standing up against acts of violence against women to a Value for Money calculation? The ethical dilemmas and practical difficulties wrapped up in measuring and ‘evidencing’ many of the processes we are involved in are huge. And, as Eyben and Roche point out, much of what we engage with in international development is messy and political. We need to make sure that the tools we have at our disposal for evidence generation are sophisticated and nuanced enough to acknowledge this messy political reality, and that we are sharing ideas on how to do this in a practical and affordable way.

The push for evidence should go hand in hand with a more entrepreneurial approach to development, opening up space for honest

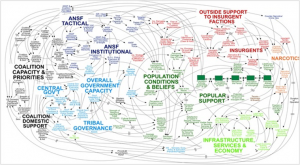

MEL that - US military mindmap of Afghanistan

reflection on both success and failure. That is the theory. But, of course, there are obstacles to this becoming a reality. Our systems in large institutions, including NGOs, are designed to demonstrate success. We all have our logframes and our KPIs, and we want to be able to put a tick in the box. No-one wants their project to be the one famous for not achieving what it set out to do, even if the real story is that it helped enormously to generate learning for future projects. Complexity thinking is having some influence right now, which helps to raise the right questions about process and incentives. However, we have a long way to go before even in the most reflexive learners in NGOs and other development institutions want their project to be hailed as the great failure.

So, we proceed with caution – welcoming the increased space the Results Agenda provides to consider ‘what seems to work’, and the profile it gives to the need to take a thorough and transparent look at the information coming out of our programmes. But, wary of the dangers of distorting what we do in order to make it measurable; of placing the MEL ‘bar’ for NGOs too high to reach; of the over-emphasis of certain methodologies; and of the danger of ignoring political realities in the work that we do. It is certainly helpful to keep reflecting and questioning, however, from all sides of the debate – so the wonkwar of last week was welcome.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers