Duncan Green's Blog, page 91

July 17, 2018

Whatâs the role of Aid in Fragile States? My piece for OECD

even to skimming it yet. Will report back on the interesting bits, but in the meantime here is the piece I  contributed, on fragility and aid.

contributed, on fragility and aid.

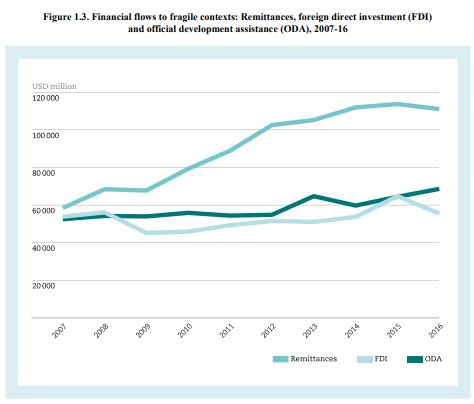

If aid is primarily aimed at reducing extreme poverty and suffering, then its future lies in fragile contexts. Recent research predicts that poverty will continue to fall in stable settings but will rise in fragile and conflict-affected settings, with poverty in these contexts overtaking the rest of the world by 2020 and then pulling away, effectively bringing an end to the current era of rapid poverty reduction. In the same vein, this report anticipates that by 2030 some 80% of the worldâs poor will live in fragile contexts. As shown in Figure 1.3, aid to fragile contexts has been rising steadily although not dramatically over the last decade, increasing to $68 billion in 2016 from $52 billion in 2007.

The increasing concentration of aid in fragile contexts lays bare the difficulties facing donors. First, these are the hardest settings in which to achieve results and the most likely to produce failures and scandals. In addition, the institutional design of aid agencies often prevents them from adapting their way of working to fragile contexts. For instance, security concerns mean that staff of the International Monetary Fund cannot even visit some fragile settings. Other donor staff who are able to work in fragile environments face daunting restrictions on their movements and contacts; many are confined to heavily fortified compounds with little access to partner governments and still less to non-state players who might be able to inform decisions. Staff turnover in such environments is often high. Finally, funding cycles are often dominated by short-term humanitarian responses, making it difficult to design longer-term strategies needed to address the fragility and its deeper causes.

The challenges to traditional aid approaches run even deeper, however. Bilateral and multilateral aid agencies have traditionally seen sovereign governments as their natural partners and/or arenas of action. But in fragile contexts, states are often weak or predatory. Many other actors fill the partial vacuum of politics and administration, among them traditional leaders, faith organisations, social movements and armed groups. The actions of individuals and organisations are constrained by these different facets of what is considered public authority, and in ways that are poorly understood by researchers and still less by aid agencies. Furthermore, the instruments of aid â funding cycles, logical framework approaches, project management, and monitoring and evaluation â assume a level of stability and predictability that is often absent in such settings.

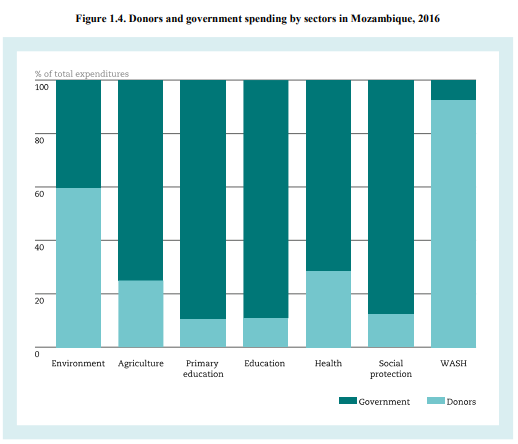

Overall, the level of aid dependence of governments in fragile contexts has fallen back slightly over the past several years. The relationship of aid to the delivery of essential services in these places raises a number of complex questions, including whether aid creates incentives or disincentives for government ownership of these services. In  best-case scenarios, the importance of aid can be exaggerated. In Mozambique, for example, health and education are overwhelmingly government-funded, with only water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) largely aid-funded (Figure 1.4.). But in worst-case scenarios, donorsâ willingness to fund basic services can absolve the partner government from doing so. In South Sudan, for example, it is reported that donors fund 80% of health care and that the government funds just 1.1%.

best-case scenarios, the importance of aid can be exaggerated. In Mozambique, for example, health and education are overwhelmingly government-funded, with only water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) largely aid-funded (Figure 1.4.). But in worst-case scenarios, donorsâ willingness to fund basic services can absolve the partner government from doing so. In South Sudan, for example, it is reported that donors fund 80% of health care and that the government funds just 1.1%.

One recent response to the difficulties faced by development actors in fragile contexts is to turn to the international private sector for help. However, international companies face many of the same problems in operating in these difficult settings. High levels of risk and unpredictability do not encourage long-term investment and the possibility of corruption and abuse poses serious reputational risks to brand-conscious companies.

Companies could seek to offset risk through public-private partnership agreements with donors and/or governments in fragile contexts. However, some in the development community and private sector have raised concerns about the higher cost of capital, the lack of savings and benefits, complex and costly procurement procedures, and inflexibility of such agreements in these settings.

International companies are most likely to take on the risks of operating in fragile contexts when returns are commensurately high. Extractive industries drill and mine in many such places. But extractives as a sector are capital intensive, create relatively few local jobs, and have a chequered record on human rights and environmental protection.

Local small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are the one part of the private sector that undoubtedly has a great deal to contribute to livelihoods and well-being in fragile contexts. However, SMEs often find it hard to navigate the complicated systems to access funding.

In trying to find effective ways to reduce poverty and vulnerability in fragile contexts, development actors increasingly accept that they must learn to âdanceâ with the system, which is a matter of grappling with the messy realities of power and politics and navigating the unpredictable tides of events, opportunities and threats. This often means abandoning or significantly adapting approaches to statebuilding and best practice developed in more stable settings.

Aid professionals have responded to these challenges by setting up networks to find ways of providing aid and support that function better in fragile contexts. One is the Doing Development Differently (DDD) network, whose 2014 manifesto set out its proposed way of working.

Aid professionals have responded to these challenges by setting up networks to find ways of providing aid and support that function better in fragile contexts. One is the Doing Development Differently (DDD) network, whose 2014 manifesto set out its proposed way of working.

DDD approaches give weight to understanding the specificities of the local context in order to be âpolitically smart [and] locally ledâ and to âwork with the grainâ of existing institutions. Responses to complex, messy problems need to be iterative, as donors and implementers adapt to changing circumstances and to lessons learned as their work progresses. These approaches are increasingly described as âadaptive managementâ.

Several new research programmes are also exploring the role of aid in fragile contexts and the efficacy of these new approaches. A recent analysis of theories of change among donors who seek to promote social and political accountability in fragile settings found an interesting bifurcation in thinking:

One current of thinking advocates deeper engagement with context, involving greater analytical skills, and regular analysis of the evolving political, social and economic system; working with non-state actors, sub-national state tiers and informal power; the importance of critical junctures heightening the need for fast feedback and response mechanisms; and changing social norms and working on generation-long shifts requiring new thinking about the tools and methods of engagement of the aid community. But the analysis also engenders a good deal of scepticism and caution about the potential for success, so an alternative opinion argues for pulling back to a limited focus on the âenabling environmentâ, principally through transparency and access to information.

In addition to the ideas outlined above, several additional options are worth exploring to try to improve the developmental contribution of financial flows in fragile contexts:

developmental contribution of financial flows in fragile contexts:

Diasporas and remittances As Figure 1.3 shows, remittances to fragility-affected countries already eclipse official development aid and foreign direct investment. They also are expected to continue to rise faster and more steadily than either of these other sources. Diasporas that send the remittances also have good knowledge of local contexts and how to support development. Some donors are exploring whether instruments such as diaspora bonds can improve the developmental impact of such flows.

Domestic resource mobilisation. Revenue raised from taxation and royalties on natural resources is growing in importance with respect to aid flows, but in many fragile contexts remains at low levels as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). Domestic resource mobilisation offers a way to further reduce aid dependence and strengthen the social contract among citizens, the state and the private sector. Until now, however, aid agencies have failed to recognise its potential. Aid figures reported to the OECD suggest only 0.2% of aid to places affected by fragility or conflict in 2015 and 2016 â a trifling USD 116 million in 2015 and USD 110 million in 2016 – was dedicated to technical assistance for domestic resource mobilisation.

Localisation. Pushing power and decision-making as close as possible to local levels makes good sense in fragile contexts to deal with the enormous variations in conditions over space and time. So far, the localisation agenda has been more apparent in statements than action, however.

Duncan Green, London School of Economics and Political Science

Tomorrow: why I don’t think much of the report of the Commission on State Fragility

The post What’s the role of Aid in Fragile States? My piece for OECD appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 16, 2018

5 ways to fix South Asiaâs Water Crisis, by Vanita Suneja

Major capital cities in South Asia – Dhaka, Delhi, Islamabad, Kabul and Kathmandu – are showing groundwater stress with the water table receding at an alarming rate. In Islamabad, the water table fell to 30 feet below the surface in 2016, compared to 5 feet in 2012.  Recently the Supreme Court of India expressed concern on the over-exploited and critical situation of groundwater in Delhi and asked the authorities to present a plan of action. Excessive pumping in Kabul has caused thousands of wells to go dry and the water table is falling at 1.5 meters per year.

Groundwater is a precious resource, allowing easy access to water in a decentralized manner at multiple locations. It is more resilient to climate change and less prone to pollution compared to the surface water (rivers and reservoirs). It is one of the critical factors responsible for making food sufficiency possible for millions of people in South Asia. South Asia accounts for nearly half of global groundwater used for irrigation.

Groundwater is also one of the key resources for piped drinking water in the cities and rural areas of South Asia – 80% of drinking water in India; 97% in Bangladesh; 80% of rural domestic water supply in Sri Lanka.

The complex tapestry of groundwater woven within soil and rocks in underground aquifers is not visible. So, unlike surface water, where diminishing quantity or quality can easily be seen, issues related to groundwater emerge only when the crisis is already upon us. But that is often too late, as replenishment of groundwater takes a long time. Over-extraction of groundwater not only affects availability for direct human consumption, it also damages wetlands and rivers and undermines ecosystem structure and services. Over-extraction also affects the quality of groundwater, by increasing the possibility of geogenic sources of contamination such as arsenic and fluoride. Around one quarter

Village : Chamraha , District: Bandha, State: Uttar Pradesh , Country: India, Date: 23/03/2018

Pappi Pal ( Water filling on cycle and Gobar leepna shots)

Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/2018/Water Aid

of the population in Bangladesh are exposed to drinking water contaminated with arsenic due to tapping into shallow aquifers. Â Salinity and arsenic affect 60% of underground supply across the Gangesâ Indo-Gangetic Basin, which supports a large population in Pakistan, India, Nepal and Bangladesh, making its water unsuitable for drinking or irrigation.

In recent years, issues of groundwater governance have gained traction in South Asia. The Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (WASA), which currently provides 78% of Dhakaâs drinking water from groundwater, has plans to double the share of surface water from 22 % to 43% by 2019, and so take pressure off groundwater extraction.

Balancing groundwater usage with other sources is important when planning cities and human settlements. In the 21 major cities of India that are expected to run out of groundwater by 2020, affecting 100 million people, it is important to focus not only on increasing groundwater recharge (the replenishment of aquifers) but also to develop and manage other sources of surface water, reuse waste water and pay attention to rain water harvesting. In Delhi, a very recent plan of action will renovate 200 lakes, treat wastewater for reuse, and concrete the canal bringing water from nearby states to reduce leakage. Pakistan passed its first ever national water policy in April 2018, recommending the creation of a Groundwater Authority as a regulatory body. The Government of India framed a model groundwater bill in 2017, including state control over groundwater extraction.

However, groundwater management requires ingenious solutions at various levels, including citizensâ engagement. Food labels comes with expiry dates and quality contents â so should aquifers. They should be publicly labelled with expiry dates, quality contents, and always be in the public imagination to encourage effective citizen engagement.

Five key challenges across South Asia need to be tackled by governments to create a robust groundwater  management regime.

management regime.

Robust data: The current assessment methodology in India uses a very small sample size of observation wells, which makes it ineffective for monitoring and management. Pakistan only recently mapped for the first time the groundwater in the Upper Indus basin.

As most groundwater usage is for agriculture, and a large population in South Asia depends on farming, the second biggest challenge is to find a suitable mix of solutions to change the cropping pattern in water-stressed agricultural areas, through incentives, pricing or regulation.

The third challenge is to enforce a regulatory framework on the extraction of water on private property by land owners. The large number of users and decentralized extraction makes any regulation hard to implement.

The fourth challenge is achieving integrated water resource management by seeking a balance between surface water and groundwater usage, and strengthening rainwater harvesting.

The fifth and the most important challenge is about triggering effective citizen engagement for participatory local governance of groundwater.

In 2015, the international community, including the governments of South Asia, committed themselves to end poverty by 2030 and leave no one behind. One of the key elements of that promise is to ensure water security. Water is the basic right and lifeline for sanitation, hygiene, food security, health, nutrition, inequality and livelihoods. It is also a key ingredient for resilient cities and human settlements.  The ministers meeting at the UNâs High Level Panel Form in in New York  this week have a unique opportunity  to come together and  review the progress on the SDG goal on  water and sanitation (goal 6)  and the goal on resilient cities and human settlements (goal 11). While discussing and reviewing goals 6 and 11 at the HLPF, member states should pay due attention to groundwater management.  But in the end, action and responsibility lie at national and local level for good governance of the respective water resources.

The post 5 ways to fix South Asiaâs Water Crisis, by Vanita Suneja appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 15, 2018

Links I Liked

The Trump demo last Friday v my first experiences in the early 80s: you still can’t hear the speakers, and everyone

still mills around trying to find their friends. But at least there’s more music now and the outfits and placards have got a lot more fun. Here are a few of my favourites (the one on the left needs to be read in Dick van Dyke cod-cockney).

still mills around trying to find their friends. But at least there’s more music now and the outfits and placards have got a lot more fun. Here are a few of my favourites (the one on the left needs to be read in Dick van Dyke cod-cockney).

While we’re on the subject, a really interesting take from Tom Carothers: Trump sees countries as a businessman sees companies – he doesn’t have friends and enemies, just wants to keep them all at arm’s length in order to do one-off ‘deals’. So he

Design v Reality: cycle path edition

pulls enemies closer, and pushes allies away.

My paper with Angela Christie on the Pyoe Pin programme in Myanmar as an example of Adaptive Management is now online

Designing for how we want humans to behave, rather than how they actually behave ht Richard Shotton

Latest issue of the excellent (and open access) Gender & Development Journal is on the role of ICTs in curbing violence and enhancing rights. Here’s the overview chapter

Every chart on economic gender inequality in one

place. Ht Ian Bray

The World Cup produced some smart humour. This spotted on a Paris pavement. And here’s some kids practicing football, when their coach shouts ‘Neymar!’.

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 12, 2018

Health, Human Rights and Plastic Bags: 3 top campaign proposals from my LSE students

too.

Each student had to produce a 2,000 word project proposal for something they would like to change and an accompanying blog. Here are 3 examples from Singapore. the Philippines and Austria.

In Singapore, Joelle Yeo [joellexyj[at]gmail.com) wants to achieve ‘a national policy change regarding Singapore’s Medisave policies to expand the scope of Medisave usage to include sexual health testing services’. But how to do that in a place like Singapore? Her power analysis suggests:

‘Singapore is a developmental state. Thus, organizational and decision-making structures are largely confined to the government, with little room for citizens to protest or challenge the state. The Singapore government possesses a lot of visible power as well as hidden power, as decisions are largely made ‘behind-the-scenes’. At the same time, invisible power is present as well in the form of conservative social norms and beliefs both at the government and national level. For example, the public advisory issued by the government regarding STIs is “abstinence, being faithful to a partner” and “avoid(ing) casual sex, or sex with sex workers.”

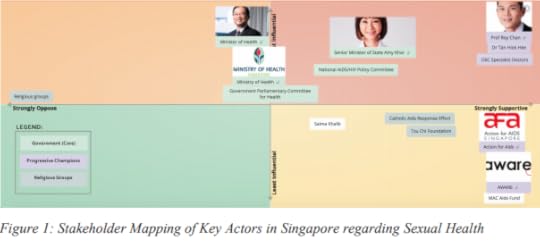

Here’s her stakeholder map. On the basis of which, she writes:

‘Prof Roy Chan has been identified as having high influence and high support. This is because of his dual role in the government and the sexual health advocacy scene. Not only is he a President’s Scholar, he is also the Director at the National Skin Centre (which oversees the Department of STI Control), an adjunct professor at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health and the Founder/President of the non-governmental organisation Action for Aids (AFA). He also sits on the National AIDS/HIV Policy Committee.

Thus, I will focus on influencing Prof Roy Chan to support and propose this national policy change. Together with the other DSC specialist doctors, he will be well-suited to convey the message to the Ministry of Health (MOH), given his influence in the government and his progressive stance towards sexual health. I will also reach out to Senior Minister of State (SMS) Amy Khor, because she frequently speaks out about HIV/AIDS and is the Chairman of the National AIDS/HIV Policy Committee. This is in contrast to the Minister of Health Gan Kim Yong, who has been relatively silent on such issues.

Joelle’s tactics? ‘Given the outcome of the power analysis and stakeholder mapping, insider tactics are likely to be more effective than outsider tactics such as popular mobilisation. This is provided the suggestions made are aligned with their interests and do not threaten the existing system. In such contexts, evidence-based influencing will be the most effective way to convince the government. Given that I will be targeting policymakers, the evidence provided should consist of big ideas and positive visions.’

She’ll also be using Singapore’s urge to be at the top of every global league table:

‘Singapore was ranked first amongst 188 countries on track to meet health-related sustainable development goals (SDG) for the year 2030 in a study published by the Lancet… [But it] is the only country that has no form of free STI testing out of the 33 countries measured. Singapore’s Asian counterparts – Japan, South Korea and China provide free STI testing services. Even Singapore’s closest geopolitical neighbours, Malaysia and Indonesia (ranked 52th and 125th respectively) provide free STI testing services, despite being Muslim-dominated and perhaps even more conservative than Singapore.’

Joelle’s full proposal here: Yeo, STD testing in Singapore.

Arbie Baguios (arbiebaguios[at]gmail.com, or see his blog) asks ‘Could a radio adaptation of Les Miserables stop the killings in the Philippines?’

Gross human rights violations. Over 12,000 killed. And yet, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s “war on drugs” enjoys high satisfaction rating from the public.

This seems crazy. Until you realise that in the Philippines, human rights are understood to be earned by those who deserve it – instead of being inherent and universal, as stated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

This means criminals including drug users are seen as undeserving of human rights. So when the government kills them without due process, the public tacitly approves. And when human rights defenders decry the abuses, they’re demonised and labelled “terrorists”.

If human rights were to be upheld in the Philippines, the goal is clear: the norm must be changed from human rights as earned and deserved to inherent and universal.

So perhaps a radio adaptation of Victor Hugo’s novel that later became a West End phenomenon (starring Lea Salonga!) could change people’s minds. After all, its deeply human characters and profound treatment of issues like justice has the audience rooting for a convict and a prostitute.

(Plus, Filipinos love musicals – and Lea Salonga!)

Human rights education through radio drama has already been done in places like Pakistan to promote women’s rights; Kenya to campaign against human rights violations by police; and Malawi to protect the rights of people with albinism.

Human rights education through radio drama has already been done in places like Pakistan to promote women’s rights; Kenya to campaign against human rights violations by police; and Malawi to protect the rights of people with albinism.

In the Philippines, there’s already a long history of human rights education. From 1998 to 2007, a “Human Rights Education Decade Plan” ensured that human rights were taught in schools at all levels.

The campaign’s “Theory of Change,” therefore, could look something like this (see left):

So could a radio adaptation of Les Mis stop the killings in the Philippines?

Not exactly.

But a human rights education campaign through radio drama that builds on local successes, involves local actors, is optimised through RCTs, and uses fiction to empower people could change the way Filipinos think about human rights – from earned and deserved to inherent and universal.

Understanding that human rights are inherently endowed to all of us could then lead to demand for policy changes that respects everyone’s rights – regardless of whether they are a convict, a prostitute, or even a drug addict!

Arbie’s full proposal here: Baguios. Human Rights in the Philippines

Teresa Schwarz came up with the memorable title ‘Don’t be a (douche) Bag’ for a campaign to ban plastic bags in Austria. A central piece of her campaign was to increase public awareness and political pressure by capitalizing on Austrians’ sense of humour and love of free tote bags, which combined make up the perfect tool for the movement. Reusable bags with the phrase “Sei kein Sack’erl” (“Don’t be a (douche)bag”) can generate attention, visualize public support and possibly reach unaware consumers. Sympathizing businesses can add the slogan to their reusable bags to spread the movement. A game can be created that encourages people to photobomb plastic bag users with their “Sei kein Sack’erl” bags and post them online; special points are given for catching politicians. This could be a fun way to demonstrate the silliness of using plastic bags while simultaneously shaming retailers still providing them and engaging the public without generating any additional costs.

According to her blog:

‘Over 70% of Austrians already agree that the time has come to finally implement a ban on plastic bags. Italy and France have paved the way within the EU and now it is time to follow suit.

While some may fear that a ban on plastic bags would interrupt the local industry, Italy and France have actually shown the opposite. In the wake of their policy changes, both countries managed to establish new markets and become leaders in the growing biodegradable industry. Since Austria’s plastic producers are already shifting their focus towards alternative materials, they could be early enough to create an additional competitive cluster in Europe.

Opponents argue that the Austrian recycling industry is efficient enough to make a ban obsolete. While I do applaud  the waste management system in Austria, even a well-functioning recycling industry cannot equate to not producing waste in the first place. Particularly since 89 % of plastic bags are only used once.

the waste management system in Austria, even a well-functioning recycling industry cannot equate to not producing waste in the first place. Particularly since 89 % of plastic bags are only used once.

The second argument states that the production of paper or biodegradable bags uses the same amount of energy as the current plastic bag industry and that a shift is therefore not environmentally desirable. While paper bags are not unproblematic, this idea completely ignores alternative fabric-based reusable bags and more importantly neglects the long-term impact the different materials have on the environment. A plastic bag is on average used for 20 Minutes, but it takes 400 years to decompose into nature. Paper bags accomplish this in about two months.

Teresa’s full campaign proposal, complete with systems and stakeholder maps here: Schwarz, plastic bags in Austria

I’m definitely hoping to stay in touch with these three, and their equally talented classmates to see how many of these campaigns turn into reality.

The post Health, Human Rights and Plastic Bags: 3 top campaign proposals from my LSE students appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 11, 2018

The last word in the Community Driven Development wonkwar? Scott Guggenheim responds to Howard White and Radhika Menon

ground as well as differences. Here Scott Guggenheim (right) responds to yesterday’s post, in what he hopes is the final exchange (people can always continue in the comments section). To recap for those who are arriving new to this, we’ve had 4 posts, including this one, which have generated over 20 comments, many extensive and very well informed. Taken together, I think they make up a good resource on the role, strengths and weaknesses of CDD:

My summary of a ‘bombshell’ of a critical ‘meta-evaluation’ of CDD by 3iE

A response from CDD guru Scott Guggenheim

A response to Scott from Howard White and Radhika Menon

Over to Scott:

‘So the bombshell has turned into a bombsqueak. Howard and co. now confirm that CDD does, in fact, build large amounts of useful, village-level productive infrastructure like clean water, market roads, and irrigation canals.

I wish I could be more conciliatory here – in fact I’d promised Duncan that I would be nice and constructive in a closing comment if given the soapbox – but while I’m glad to see the climbdown, I still don’t buy it. Either so many brilliant poverty specialists who read the 3ie paper mistakenly thought that 3ie had devastated CDD, or else they all somehow believe that potable water, irrigation, and market roads are no longer needed in poor and isolated communities. I prefer the read of a climbdown to thinking that all of those readers need new eyeglass prescriptions. Even in 3ie’s latest comments about a lack of comparator evidence to show cost effectiveness, they again leave out the studies from the very large programs in Afghanistan, Indonesia, Nepal, and the Philippines that show precisely that.

Let’s turn now to the more interesting question of what gives poor communities more voice in development. First, except for one $2.5m project in Sierra Leone that I’ve spent nearly a decade trying to convince my friend Rachel Glennester was actually a not very well thought through outlier, to the best of my knowledge, no CDD project has had the objective of building new social capital. As Casey (2017) points out, mean levels of trust in control communities  were already high: 95% in Sierra Leone; 93% in DRC and 85% in Afghanistan.

were already high: 95% in Sierra Leone; 93% in DRC and 85% in Afghanistan.

CDD’s claim is that we can use this existing social capital to facilitate and benefit from collective action within a community if (and only if) we can change the approach that state agencies use to partner with them. It sounds like a modest goal, but when this CDD work started in the 1990s, using local knowledge and delegating decision-making and resources to communities was about as popular in large development agencies as was farting in church. And, in fact, for all of the rhetoric today, they still don’t do very much of it – the general model remains, at best, one of setting up various flavors of ventriloquized “user groups” without any serious attention to the rules or processes for ensuring accountability, representativeness, or inclusion.

But while 3ie is “staggered” to find no impact on something that CDD has neither claimed nor disputed, our knowledge of what forms of collective action can give serious voice in the state-community encounter is still quite limited. That’s all the more reason to not discard the few tools that we have to expand that knowledge. I’m glad to see that 3ie now thinks that significantly increasing women’s attendance in village and subdistrict council meetings is indeed a worthy governance achievement, but their dissemination note for this study still says “CDD has no impact on social cohesion or governance.” And, in general, I would have thought that more local control and accountability over spending is a lot – not all, but a lot – of what any metric of changes to local governance would be measuring.

Let’s see if we can close with some sort of consensus. I agree with Howard and Radhika that at this point, evaluations of what works where and why are what is most important, rather than sweeping ‘CDD is good or bad’ claims. In my first comment I tried to explain why issues such as external validity, measurement intervals, and knowing your context variables are so important for this purpose, but for these broader issues of voice and power, I think we face a growing trade-off between increasingly precise measurements of increasingly less interesting questions about individual projects when we should be teasing out the links and interactions across different types of social action.

The most interesting work in CDD world these days is looking at complementarities between CDD and household cash transfers (Indonesia, Philippines); evolving the CDD platform into a whole of government frontline service delivery system (Afghanistan, India, Indonesia, Morocco), and coupling community development with better market access and returns for poor people (Nepal, Sri Lanka, India). Dewi Susanti and her team in Indonesia are currently conducting a large scale RCT that is testing whether more community control over teacher’s benefits can make a dent in teacher’s high absentee rates, the kind of evaluation that, if true, would be immensely beneficial to multiple countries, just as India’s fascinating examples of CDD projects investing CDD funds to train likely to migrate rural youth in urban skills is just begging for analysis and transfer.

access and returns for poor people (Nepal, Sri Lanka, India). Dewi Susanti and her team in Indonesia are currently conducting a large scale RCT that is testing whether more community control over teacher’s benefits can make a dent in teacher’s high absentee rates, the kind of evaluation that, if true, would be immensely beneficial to multiple countries, just as India’s fascinating examples of CDD projects investing CDD funds to train likely to migrate rural youth in urban skills is just begging for analysis and transfer.

My own favorite – mostly because I recently visited them – and still unmeasured example, was seeing how the activists from Indonesia’s female headed household empowerment NGO (PEKKA) used the transparency requirements of the CDD program to sponsor public debates between political candidates vying to become district heads over who would be matching those funds to help widows and other poor women.

To conclude, let’s be very careful about throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Any approach that reaches poor, neglected communities with large amounts of decent quality, pro-poor, cost-effective, self-targeting, economically productive assets should already receive a tick mark in the “plus” column. That all project models show variance in their quality is a truism, not an indictment, one which mostly puts the burden onto project owners to show that they can learn and improve. The way forward is to keep pushing boundaries, show a sufficient number of well-monitored and explained failures to prove that nobody’s getting complacent, and to keep using multiple types of analyses to cross-check and validate hypotheses.’

Last word? Let’s see…..

The post The last word in the Community Driven Development wonkwar? Scott Guggenheim responds to Howard White and Radhika Menon appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 10, 2018

Community Driven Development: Howard White and Radhika Menon respond to Scott Guggenheim

Evaluations have two functions: lesson learning and accountability. We believe that our report on community-driven development offers useful lessons for programme managers, practitioners and researchers. Despite posting a blog response to earlier comments, a critical backlash continues. This is disappointing – especially as our ‘critics’ use the arguments we make in the report to make arguments against us. We agree with virtually every point in Scott Guggenheim’s blog, though he writes as if we are at loggerheads. So, we would like highlight the important lessons, which are mostly areas of agreement, and set the record straight over perceived shortcomings in our report.

Our review is not a critique of CDD. And we do not say “CDD does not work”. We find that CDD has been enormously successful in delivering small scale infrastructure. We report figures on the thousands of facilities built which serve thousands of people in many countries. We do say that there is insufficient evidence on cost effectiveness. So, this is an area for further research. We do not make a recommendation to switch to local government procurement.

The positive effect on infrastructure has however not always resulted in improvements in higher order social outcomes. Meta-analysis of impact evaluation results show that CDD programmes have a weak effect on health outcomes and mostly insignificant effects on education and other welfare outcomes. While these are the overall findings, the report identifies and unpacks instances where there are positive effects. For example, there was an increase in girls’ enrolment in Afghanistan despite education being a very small share of overall investments. We attribute the increase to changing gender norms supported by the National Solidarity Programme (NSP). Our explanations chime with what Scott has to say. But somehow his blog makes it seem like we are in disagreement with him.

The positive effect on infrastructure has however not always resulted in improvements in higher order social outcomes. Meta-analysis of impact evaluation results show that CDD programmes have a weak effect on health outcomes and mostly insignificant effects on education and other welfare outcomes. While these are the overall findings, the report identifies and unpacks instances where there are positive effects. For example, there was an increase in girls’ enrolment in Afghanistan despite education being a very small share of overall investments. We attribute the increase to changing gender norms supported by the National Solidarity Programme (NSP). Our explanations chime with what Scott has to say. But somehow his blog makes it seem like we are in disagreement with him.

Further on gender norms, the impact evaluation of the second phase of NSP in Afghanistan did find ‘mixed effects’ of the programme on gender norms. Men’s acceptance of women in leadership in local and national levels had increased, as had women’s participation in local governance. However, NSP did not lead to any change in men’s attitudes towards women’s economic and social participation or girls’ education. Scott’s blog reports only the first and not the second finding in arguing we are wrong to say the evidence is mixed.

But our statements in the report are anyway based on reviewing the evidence not from just one case, but from over twenty CDD programmes, where success in promoting inclusiveness is certainly mixed. We argue that programme designers can learn from where there has been more success, as in Indonesia.

Our examination of variations in impact on education outcomes is an example of how we analyse heterogeneity. Heterogeneity is the friend of meta-analysis, not its enemy. Meta-analysis allows us to explore variations in design and context, which explain programme performance. But we have been criticised for including a range of programmes, especially social funds. Such criticism fails to recognise how social funds evolved – those in Malawi and Zambia came to be run using a very CDD approach. An external agency may be involved in vetting that decision or deciding between competing proposals, that is one of the CDD design variations. But all programmes – not just social funds – imposed some limitations on the use of the funds.

Our review finds that CDD has no impact on social cohesion (see right). There is no heterogeneity there. The lack of effect on  social cohesion is consistent across contexts. It is in building social cohesion that CDD has not worked. This is where meta-analysis is so useful, as it clearly illustrates the consistency of this finding. Scott’s blog concedes this point. So we are on the same page as far as these findings are concerned, which is not an impression you get when you read Scott’s blog.

social cohesion is consistent across contexts. It is in building social cohesion that CDD has not worked. This is where meta-analysis is so useful, as it clearly illustrates the consistency of this finding. Scott’s blog concedes this point. So we are on the same page as far as these findings are concerned, which is not an impression you get when you read Scott’s blog.

As we say in the report, the lack of impact on social cohesion is not a new finding. Indeed, one of us was a co-author of the 2002 OED review of social funds – including the CDD-like Malawi and Zambia funds – which reported no impact on social capital, as did the OED CDD report three years later. The review confirms this finding now that we have additional evidence from high quality impact evaluations.

An issue for further research we did not flag and should have done is long run effects on governance of the longer run programmes. We do distinguish between those programmes which have a multi-year, multi-project investment in communities and the ‘single shot’ designs. It is plausible that the former, like the Kecamatan Development Programme in Indonesia and Kalahi-CIDDS in the Philippines would have a larger impact. But there is no evidence of this. We can say there may be a longer run impact, which further research could assess.

Reviews intend to be comprehensive, but have inclusion criteria. So, some studies people think should be included get excluded. What matters is that we use relevant evidence to analyse whether programmes have worked, and delve deeper into questions of what they have worked for and why they have worked or not worked. People who have worked on specific CDD programmes have both a richer viewpoint but also a more restricted one. Scott also presents research findings from contexts he is associated with. This does not mean that we discount what he has to say but it has to be put into the bigger picture.

Reviews intend to be comprehensive, but have inclusion criteria. So, some studies people think should be included get excluded. What matters is that we use relevant evidence to analyse whether programmes have worked, and delve deeper into questions of what they have worked for and why they have worked or not worked. People who have worked on specific CDD programmes have both a richer viewpoint but also a more restricted one. Scott also presents research findings from contexts he is associated with. This does not mean that we discount what he has to say but it has to be put into the bigger picture.

Reviews do have their methodological limitations and evaluations can have different findings across contexts. The answers are not straightforward; they are often nuanced. Our plea to the development community would be to resist getting into ‘My study is right’ and ‘Your study is wrong’ debates and spend more time in constructive conversations about using evidence to inform programmes that can improve lives. Yes, we say CDD doesn’t build social cohesion. But we don’t say CDD doesn’t work – the answer depends on the outcome you are looking at. And there have been substantial variations in CDD’s effectiveness, so let’s learn from the variations to design better programmes.

For those interested, we also recommend reading the full report (rather than the brief which provides just a summary that some have reacted to).

The post Community Driven Development: Howard White and Radhika Menon respond to Scott Guggenheim appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 9, 2018

Adaptive Management: the trade offs; how to build trust; the sources of resistance and how to counter them

Not sure if you can take any more posts on Adaptive Management, but I had an interesting conversation with Stephen Gray on AM and Peacebuilding, which he may be using for a podcast. A few lightbulb moments:

Things we often assume go together, but they actually don’t. Two candidates:

Results v Risk: There is a vague sense that those evil planners are asking for a bunch of things at the same time

The results agenda

– results, value for money, upwards accountability (e.g. regular reporting to donors) and avoiding screw-ups that can land them in hot water with northern parliaments or publics. But if you believe a growing body of evidence, and the logic of systems thinking, you can’t have all of these things at the same time. Risk means different things to different people, but political risk (the Daily Mail test, not the risk of failing to help poor people) is what keeps politicians up at night. But if they demand zero or minimal risk (eg all those ministerial soundbites about ‘zero tolerance of corruption’), that precludes experimentation and innovation and so undermines results.

So one role for those wishing to encourage experimentation, adaptation and innovation is to help mitigate political risk (another is, of course, just to whinge about how much we hate politicans, but I don’t find that very helpful). Say you want an aid agency to think about risk across its portfolio – it will have a large number of low risk projects, and then a few high risk, high return whacky outlliers that might work, but might crash and burn. A bit like Google has a few bonkers projects like abolishing death (aka a Barbell Strategy). The trouble is that in the aid sector, it’s those that end up on the front page of the Daily Mail, so we need to find ways to insulate donors from project risk, eg by having intermediary/ arm’s length funding mechanisms.

An alternative would be for some foundations with fewer political strings, and a greater appetite for risk, to explicitly position themselves as the whacky adapters, and so provide cover for their more conservative colleagues. I have to say, that the big private foundations often don’t seem to take advantage of their relative political freedom to do this – half the time they behave like wannabe DFID’s with all the panoply of risk avoidance, reporting and results.

Adaptive Management v bottom up/localization: The discussion at the recent AM workshop in Bologna clarified that some local partners, whether governments or CSOs, are not that keen on all that iterative uncertainty. They want trips, training and concrete (schools, roads, buildings). If that is the case, we face a difficult choice: persuade them of the virtues of AM, abandon it, or find different partners, which is hardly an exercise in bottom-up accountability.

2. Trust is the essential currency of Adaptive Management, but we have slipped into a low trust, high compliance culture that is hard to shift. When talking about corporate social responsibility, I always felt very smart when I trotted out the saying ‘we have moved from a ‘trust me’, to a ‘show me’ society’. But that is actually  anathema to adaptive management, which relies on trusting programme staff and partners to do ‘adaptive delivery’ – feeling their way and changing their direction on a daily (if not hourly) basis, in response to the signals they are receiving.

anathema to adaptive management, which relies on trusting programme staff and partners to do ‘adaptive delivery’ – feeling their way and changing their direction on a daily (if not hourly) basis, in response to the signals they are receiving.

All the panoply of reporting and compliance can be seen as a substitute for trust. But how do we rebuild it? Saying ‘just trust me’ is a non starter, because donors need to be able to distinguish between adaptive management and good old fashioned incompetence – changing things on a daily basis, saying you’re not ready to report results, asking to alter the plans and targets could stem from either. One option is to move from compliance to probation – keep new staff or partners on the leash for a certain period of time, but then if they don’t screw up, have an explicit process for reducing compliance and expanding discretion over time. Which is kind of what I did in the early years of this blog (‘moving from permission to forgiveness’).

How to counter the headwinds that are blocking progress on AM?

Identify the blockers

When asking why change isn’t happening, a handy rule of thumb is the 3i test: what is the combination of institutions, interests and ideas that is blocking progress? In the case of AM we have:

Institutions: the mechanisms of the aid business – reporting requirements, timebound projects, high staff turnover all seem to work against AM

Interests: Aid organizations need to generate projects to pay their staff and big up their CEOs, while commercial project contractors (a growing presence) also need to make profits. That makes it unlikely that they will start criticising the project gravy train and pioneer new approaches. In the wonderful words of Upton Sinclair, ‘“It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

Ideas: The mental landscape that sees linear projects and plans as the ‘natural’ way to do things may be so deeply rooted that people are simply incapable of imagining a different way of working.

So how ‘we’ – the plucky band of adapters and iterators – disrupt the 3 I’s that together block progress? I guess my shorthand would be – use crises and critical junctures to shake up institutions, advocacy to expose and weaken interests, and education and research to sow the seeds of a shift in ideas (though that may be a generational project). Not enough room to expand on these now, but may come back to it.

The post Adaptive Management: the trade offs; how to build trust; the sources of resistance and how to counter them appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 8, 2018

Links I Liked

Oxfam is doing some innovative, nuts and bolts work on gender and development:

Measuring the impact of a gender rights project on women’s empowerment in Indonesia. V cool bit of evaluation using quasi-experimental research design

How to construct a women’s empowerment indicator for a given project/community based on women’s own weighting of different contributory factors.

Using Rapid Care Analysis with Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

Costa Rica Becomes the First Nation to Ban Fossil Fuels

Paging George Orwell/Black Mirror. ‘China has stated that all 1.35 billion of its citizens will be subject to its social credit system by 2020, and travel restrictions for low-scoring citizens is only one of many to come.’ ht John Magrath

Does nature conservation deserve a slice of the aid budget? A new report from the Conservative Environment Network suggests raiding UK aid budget for conservation projects that ignore livelihoods and people.

The future of the welfare state. ‘More money will not fix our broken welfare state. We need to reinvent it, centred on fostering relationships’.

Two of my heroes, Kate Raworth and Branko Milanovic, are disagreeing in an illuminating exchange on Doughnut Economics

Lovely discussion on growing up Asian in North America

If golf and soccer switched announcers

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 5, 2018

Book Review: Navigation by Judgment, by Dan Honig

to the growing library of books on aid reform. And a very useful one.

Honig is a hybrid scholar-practitioner, with dirt under his fingernails in East Timor and Liberia, and the book is for aid insiders, whether practitioners or scholars, focusing on ‘the internal organization of international Development Organizations’ (IDOs), It explores how that internal organization interacts with different kinds of issue (health, infrastructure, governance) or context (stable, predictable, messy & chaotic).

In doing so, Honig attempts to make his arguments convincing to both quals and quants, mixing in depth case studies (4 projects each from DFID and USAID), and number crunching on a mammoth dataset he has built of 14,000 aid projects (which he’s made open access – kudos!).

It’s that addition of a big number crunch that probably adds the most value, because it confirms the arguments and findings on Doing Development Differently, Adaptive Management etc etc, but in a way that is more likely to satisfy, or at least silence, sceptics. Experience is on our side, and now the numbers are too!

The summary of the summary is:

‘This book is an exploration of the costs and benefits of top-down control as compared to relying on the judgment of field agents. I argue that just as there can be too little control, there can also be too much. In doing so, I echo the view of no less an authority than former USAID administrator Andrew Natsios, who has argued that the IDO he used to run suffers from “Obsessive Measurement Disorder (OMD)”, an intellectual dysfunction rooted in the notion that counting everything in government programs . . . will produce better policy choices and improve management.’

To unpack this he uses my favourite device – a 2×2. On the X-axis axis he has level of project verifiability – can you measure results on something useful like whether people’s nutrition improves, or do you have to measure ‘outputs’, eg number of training seminars, which are a poor proxy for actual results? On the Y-axis we have high environmental predictability v low. It’s pretty similar to the one we came up with in a USAID/DFID seminar a couple of years ago, and helps the discussion forward by showing that in some quadrants logframes and conventional approaches work best, in others we need to ‘do development differently’.

He summarizes his core argument in the academic language of principal-agent theory:

‘Using Navigation by Judgment requires relying on agent judgment, and even the best agents will sometimes make mistakes. Navigation by Judgment is a second-best strategy—a strategy to employ when it is less bad than the distortions and constraints of top-down control.’

So what are his findings? The biggest contribution is probably the way organizational structure and culture influences aid. Honig distinguishes between ‘more politically insecure’ IDOs, constantly looking over their shoulder and pacifying their critics (USAID and Congress) and less insecure ones that have the confidence to try stuff out (DFID – though that may come as news to some DFID people!). The former spend huge amounts of energy trying to control what happens in the field, and gathering bucket loads of numbers to chuck at their enemies political bosses. The latter have more latitude to think about what kind of monitoring, evaluation and learning might actually help a given project achieve its aims.

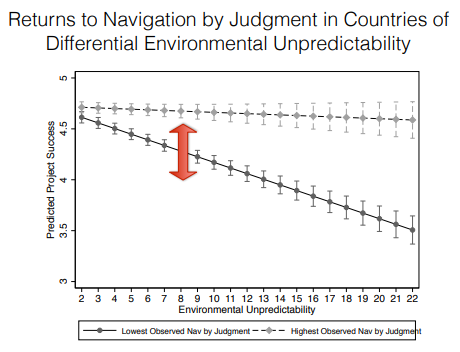

This matters because ‘As environments become more unpredictable and interventions less externally verifiable, the flaws of principal control weigh IDO projects down more heavily than do the weaknesses of fallible agent judgment. When the going gets tough, Navigation by Judgment helps cope with the rougher terrain.’ So in messy places like fragile/conflict states, IDOs that navigate by judgement do better than their more rigid colleagues, even though both groups find life harder than in stable places.

This matters because ‘As environments become more unpredictable and interventions less externally verifiable, the flaws of principal control weigh IDO projects down more heavily than do the weaknesses of fallible agent judgment. When the going gets tough, Navigation by Judgment helps cope with the rougher terrain.’ So in messy places like fragile/conflict states, IDOs that navigate by judgement do better than their more rigid colleagues, even though both groups find life harder than in stable places.

Unfortunately he stops there – I would have liked to see some discussion of whether USAID and other more under-the-cosh agencies can do much to remedy their situation, what political moments, arguments or alliances might allow them to make progress, or at least prevent rapid backward movement. Or whether DFID is likely to stay as insulated as he currently thinks it is.

Instead he slips back into a more conventional set of policy recommendations on how to make ‘IDOs fit for purpose’:

measure smarter and differentiate between measurement for learning (how to improve the project), and measurement for accountability (feeding the wolves)

change the frequency of measurement (quarterly results can kill a project and leave its staff largely braindead)

think about kinds of accountability other than voodoo numbers, eg peer judgement, ‘discursive accountability’.

Think about portfolios: there is too much of a monoculture in IDOs, where every project looks at risk and control separately, as does every country programme, and every organization. Portfolio thinking could change that, seeking a spread of risk across a country programme, an organization, or even between IDOs – the ones with a more secure authorizing environment could take on the messy places, and the ones that have Congress on their backs can stick to bednets, vaccinations or pouring concrete.

Other take-aways?

We had a big discussion when he launched the book in London on whether his findings suggest big IDO should take more aid projects in house, rather than work through contractors (as they increasingly do). His initial comment was that ‘The move to contracting out goes against navigation by judgment – a contract needs to be

When do you need a compass? When a map?

fixed, litigable. It’s really hard to litigate relationships’. That isn’t to say it’s impossible to get navigation by judgment in a contract, only more difficult; as Honig put it, ‘It would need non-traditional contracts to crowd in judgment – but that means relations based on trust, not just contract language. How do you know that a contractor will exercise judgment rather than just seek to maximise profits? Options could include looking at its track record, or co-locating donor and contractor staff.’

Honig’s findings are a powerful argument for pursuing Doing Development Differently approaches in messy places like Fragile and Conflict Affected States, where we can now show that they outperform conventional projects. At the launch, Honig said that governance in FCAS is the extreme case – there is almost nothing useful we can count and attribute, either in outputs or outcomes, so navigation by judgement should rule. Doesn’t make it any easier though.

The post Book Review: Navigation by Judgment, by Dan Honig appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

July 4, 2018

Public Pressure + League Tables: Oxfamâs campaign on food brands is moving on to supermarkets.

‘First the brands, now the retailers.‘ That was the reaction of a senior staffer at Mars – one of the 10 biggest global food manufacturers targeted in our award-winning Behind the Brands campaign – to the Behind the Barcodes launch last month. Why did we choose supermarkets as our follow-up campaign, and what if anything is different this time around?

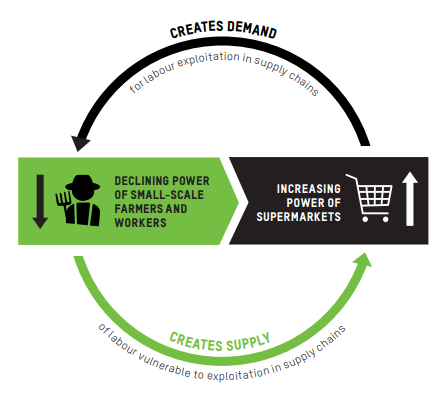

While supermarkets seem even further removed than the brand manufacturers from the producers and workers we aim to benefit, in many products they are the dominant lead firms in food value chains. From bananas to orange juice retailers are taking control and their private labels gaining market share. As the last link in the chain they have enormous positional power to set prices and other contractual terms over all other actors – even the big brands. The UK’s Marmite wars gave a taste of the power relations at play in that regard.

Their power is borne out in our new research. We show that both in aggregate and in the 12 food product chains we looked at in more depth, it is supermarkets that capture the biggest share of the end consumer price of any actor in food value chains, and that they have seen their share grow the most over the past 15-20 years. They’re also the entry point to the food chain for millions of consumers around the world – good targets therefore for a public campaign (unlike the big grain traders, for example).

But what difference has this choice made to the campaign model and theory of change?

Some things remain the same: most notably, we’ve made another scorecard. This one has 4 themes – ‘transparency’, ‘workers’, ‘farmers’ and ‘women’ – instead of 7, and we thoroughly revised and updated all indicators. We’ve dropped the themes related to natural resource rights not because they don’t matter, but for greater focus with a sector we judged has further to travel at the outset than the big food brands.

Some things remain the same: most notably, we’ve made another scorecard. This one has 4 themes – ‘transparency’, ‘workers’, ‘farmers’ and ‘women’ – instead of 7, and we thoroughly revised and updated all indicators. We’ve dropped the themes related to natural resource rights not because they don’t matter, but for greater focus with a sector we judged has further to travel at the outset than the big food brands.

The initial scores bear that out: there are no clear champions and lots of laggards. The highest score of any company on any of the themes is just 42%, and in each theme several companies score 0%. Once again the lowest scores are found in the ‘women’ theme, where only Walmart scores more than 10%.

The Behind the Brands scorecard helped drive a race to the top, and we are looking for the same again. The campaign model will again see us run shorter public campaign spikes on particular issues – starting with workers’ rights – and targeting particular companies as a complement to the scorecard. We learned in Behind the Brands that this focused public pressure in addition to the scorecard was critical in driving the biggest advances from companies (we’re not the first NGO to produce a scorecard, after all).

But there are some big differences in our approach this time around too.

First, this campaign is much more decentralised than Behind the Brands. We considered spotlighting the biggest 10 global supermarkets again, but the market dynamics are quite different at the retail end of the chain. While many of the big players have internationalised their presence – US Walmart operates in 29 countries, German Lidl in 26 and South African Shoprite in 15, for example – most don’t compete directly in the same markets, where a range of smaller national players control significant market shares too.

A more decentralised approach fits Oxfam’s internal dynamics too. The big Northern Oxfam affiliates were the gatekeepers to the Behind the Brands target companies. But in line with the Oxfam 2020 vision we wanted a model this time that could facilitate national campaigning in the South too.

While we have launched versions of Behind the Barcodes in Germany, the Netherlands, the US and the UK, we’re thrilled that our Thailand team have launched their version today, and that a related campaign from the Sustainable Seafood Alliance Indonesia – Di Balik Barcode – launched last week. We hope Oxfam teams in Italy, Brazil and Southern Africa will be among those joining over the coming year

The resulting campaign model is certainly more complex to manage. We’ve ended up with two campaign names – it’s called Behind the Price in some places – and a lot of nationally-tailored annexes to our launch report as a result. But we think we have enough ‘glue’ to make this more than the sum of its national parts.

We’ve already heard from European supermarkets that want to know how Walmart outscores them. We’ve been pointing out to German and Dutch supermarkets how far they lag behind international peers. The campaign is on

the radar of companies like Aldi and Lidl in several of their markets. While our campaign targets may not all be direct competitors, we are making it much harder for them to hide behind the inaction of others in their own market.

Two other key things are different this time. We have a bigger focus on inequality in our problem analysis. By showing how the inequality of power is at the root of human suffering in food supply chains, we are shining a spotlight on one sector of a global economy that, as we argued in this year’s Davos report, rewards wealth over women’s work.

And where Behind the Brands could be criticised for putting too much emphasis on voluntary action by companies, we are much clearer this time on the role that governments must play in protecting human and labour rights in food supply chains. We’re pushing for EU action to regulate supermarket unfair trading practices and calling for mandatory due diligence legislation in Germany, for example. Our research shows that from setting adequate minimum wages and agricultural commodity price support schemes to tackling entrenched norms that discriminate against women, public policy matters.

So we are building on the best bits of Behind the Brands, while innovating for Oxfam’s new operating context. The result is a much more complex model, but – if it works – one that could be the future of how Oxfam campaigns.

The post Public Pressure + League Tables: Oxfamâs campaign on food brands is moving on to supermarkets. appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers