Duncan Green's Blog, page 87

September 14, 2018

New on FP2P: My audio summary of the week’s posts – what do you think?

Lots of plans to spice up FP2P over the next few months – will let you know as they emerge. But one pretty simple one is to get more into audio and podcasts. As a really simple way to dip my toe in the water, I thought I’d start doing a weekly summary of activity on FP2P. Here’s my first go, discussing last week’s posts – please tell me how to make it more useful, what you’d like more/less of etc, or whether you think it’s a complete waste of time!

http://oxfamblogs.org/fp2p/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Wb-10-sept.m4a

The post New on FP2P: My audio summary of the week’s posts – what do you think? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 13, 2018

Some FP2P posts you might have missed – summer catch-up part 2

jog you into clicking through, or were just lounging in the sun. Here’s the main posts that went up from July until we fixed the email notifications a week or so ago

Posts on new approaches to aid, reflecting my research at both Oxfam and LSE. These included what peace and conflict mediation can teach the Thinking and Working Politically crew; More of my thoughts on Adaptive Management and Exfamer Chris Roche gets nerdy on its link to MEL.

A lot of the aid rethink is coming from work in fragile states: check out an interview with DFID governance guru Wilf Mwamba on aid’s blind spot on non-state actors like tribes, armed groups and faith leaders; my piece on aid and FCAS for a new OECD report and me slagging off reviewing the recent report of the LSE-hosted Commission on Fragility, Growth and Development.

Other stuff from the humanitarian side: Ajoy Datta on lessons from the Nepal earthquake while Ed Cairns gets all reflective on what restrains extreme violence – culture or the law?

Couple of book reviews: Matthew Spencer on Factfulness, by the Roslings; me on Navigation by Judgment, by Dan Honig.

Lots of campaign fodder: The latest list of the world’s top 100 revenue collectors shows that 29 are states; 71 are TNCs; Contrasting approaches to tax campaigning in Oxfam (Vietnam) and ActionAid (Nigeria); Campaign proposals on health (Singapore), human rights (Philippines) and plastic bags (Austria) from 3 of my amazing LSE students; Tim Gore on the evolving theory of change behind Behind the Bar Code

Handy Mansplaining flowchart. You’re welcome.

Some regional commentary: Vanita Suneja on the water crisis in South Asia; Simon Ticehurst on why everything is going pear shaped in Latin America

And some random other stuff:

The International Budget Partnership on going to scale in South Africa

Some surprising research finds that public support for UK development NGOs is actually growing

Communicating research about sustainability

Erinch Sahan reflects on his first 100 days as boss of the World Fair Trade Organization

‘What did I learn from 2 days of intense discussions on empowerment and accountability in messy places?’

Lukas Schlogl and Andy Sumner present a new paper on development impact of the rise of the robots

Alan Whaites on why aid workers should be more aware of the potential in internal battles within host country governments

Finally, my new paper on whacky ideas for Oxfam’s future (final paper here –Fit-for-the-Future-2-July-2018).

Happy up-catching

Oh, and this is still my favourite Brexit spoof – can anyone beat it?

The post Some FP2P posts you might have missed – summer catch-up part 2 appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 12, 2018

Someone just called their new book How Change Happens – here’s my totally impartial review

disturbing – a bit like finding out that someone who looks just like you has assumed your identity and is chatting to your mates. But the new book by Leslie R Crutchfield ‘How Change Happens: Why some social movements succeed while others don’t’ sounded pretty interesting, so I tried to swallow my annoyance (did no one think to google the title?) and review it. Still, you probably need to make due allowance for lingering authorial irritation.

This HCH starts with a great question: Why have US social movements on things like tobacco control progressed so fast, when others, eg on gun control, have got nowhere? ‘How could society simultaneously grow ‘more gay’, stockpile unprecedented caches of guns, quit smoking, stop driving drunk, and remove the toxins from the air that created acid rain and destroyed the ozone, only to later fail to cap carbon emissions in any meaningful way?’ OK, you’ve got my attention.

To answer this, Crutchfield put together a 20 person research team and identified a range of case studies from recent US social movements. A good start, reminiscent of Friends of the Earth’s great research on the lessons of historical campaigns in the UK.

The book’s greatest strength is the in-depth case studies of a politically diverse range of US social movements, from equal marriage to the NRA. On the basis of these, it concludes that:

‘Change will only come when there is a grassroots-fueled movement led by individuals with the lived experience of the problem agitating from the bottom up, along with savvy networked coalitions of organizational leaders at the grass-tops who understand that their role is to coordinate and align the players around them in collective action. They do this by building ‘leaderfull’ movements and focussing on changing hearts as well as policies.’

The book bigs up activism, and downplays everything else: ‘One of our foremost revelations was this: Change happens not by chance. It is determined by individuals and the organizations and networks that bind them together.’

Becaus being right isn’t always enough……

Erm no, actually. Here’s where the two versions of How Change Happens part company. Sure, activism can have big impacts – I wouldn’t work for Oxfam or write books like How Change Happens (the other one) unless I believed that. But lots of change does happen by chance – new tech? urbanization?

What’s more, encouraging activists to believe that ‘it’s all about us’ makes them worse activists, spending all their energy internally on building the right coalition, or training new leaders, at the expense of learning to ‘dance with the system’ of society, power, politics and the economy that to a large extent will determine the fate of even the best-organized campaign. (The book mentions systems thinking, but then only applies it internally to the ‘system’ of social movements).

The book also exemplifies a dilemma I wrestled with while writing my own version of How Change Happens: should you boil it all down into a handy checklist for better activism? Codifying and ‘professionalizing’ activism in this way worries me because it risks isolating activists off as a separate tribe, talking to each other, swapping top tips on the best way to organize a petition or stir up a twitterstorm, while ignoring the context.

In the end, I stopped short, talking in terms of a general ‘power and systems approach’, but reluctant to go further. Crutchfield has no such scruples. She sets out 6 ‘practices’ (power to the grassroots; operate at local and national levels; target attitudes as well as policy; manage conflicts within your movement; work with business; cultivate dispersed leadership) and sets out lots of ‘questions to consider’ for each.

What we end up with is a book entirely focused on what I call ‘theories of action’ – the tactics and qualities of activists – with only the most cursory discussion of ‘theories of change’ – how the system is changing without those activists. What tech, demographic, political, economic processes are driving change? What critical junctures (crises, scandals, new political actors) shape it? Not relevant, apparently.

Instead, it is now all about us, a kind of social movement version of those ’10 ways to be the next Steve Jobs’ manuals that plague the airport bookshops. ‘How US Activism Happens’ would be a more accurate title (the rest of the world doesn’t exist in this book).

Rant over – sour grapes or fair comment? Feel free to read the book and tell me which it is, but be warned, it’s not cheap (£24.99 in the UK) and (unlike my version), it’s not free online.

The post Someone just called their new book How Change Happens – here’s my totally impartial review appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 11, 2018

How can Civil Society respond to government crackdowns around the world? New Oxfam paper (and hello to Oxfam GB’s new boss)

a mate. He comes to us from Civicus, the global alliance of civil society organizations. Here he is writing on this blog last year on the role of INGOs, if any, in defending civil society space. This is gonna be fun.

While we’re on the subject, Oxfam just published ‘Space to be Heard’, a paper on how to respond to ‘shrinking civic space’ – the relentless squeeze in dozens of countries on the activities of civil society organizations and activists. Two sections struck me:

Firstly, the diagnosis: What are the global drivers of shrinking civic space?

Shifting balances of global power: the growing discourse of national sovereignty and non-interference

Rising inequality: political and economic elites cracking down on civic action that challenges powerful vested interests

The changing nature of security: counter-terrorism and polarized societies

Civil society legitimacy being questioned: weak accountability and missing links with citizens

Changing development discourse: questioning the integral value of civil society

Populism, authoritarianism and nationalism on the rise: eroding the values of freedom, democracy and diversity’

Secondly, five areas that ‘civil society actors should consider if they are to become more resilient and effective in contexts of shrinking and shifting civic space.’

Secondly, five areas that ‘civil society actors should consider if they are to become more resilient and effective in contexts of shrinking and shifting civic space.’

‘Accountability

Civil society organizations need to adopt the same transparency and accountability standards that they demand of others, both to governments and donors and to citizens and constituencies. Building grassroots legitimacy should go beyond minimum public engagement strategies towards transformational change in ways of working, involving constituencies and mobilizing people. Strengthening transparency and accountability reduces the likelihood of being wrongly accused of mismanagement, tax avoidance and fraud, and enables more effective responses when being discredited.

Resilience and risk preparedness

Civil society actors must be prepared for risks such as arrests and harassment of outspoken individuals, freezing of financial assets, attacks on the reputation of individual activists, civic groups and organizations, and other tactics to restrict their activities. This includes having effective risk management and holistic security skills and systems, budgets reserved for mitigation, prevention and emergencies, and strong support networks that provide access to legal, political and psychosocial support. Building the resilience of local civil society organizations can also mean diversifying their funding streams, including through domestic resource mobilization.

Alliance building

We have found that threats to civic space are most effectively addressed when diverse civil society actors join forces.  Alliances should be as broad and inclusive as possible – including formal and informal civic actors with various identities, faith-based organizations, trade unions, media, universities, business associations, community groups, online activists and others. These alliances often need to be unbranded to provide space for diverse actors. Working in diverse alliances to protect and strengthen civic space enables civil society actors to protect the most targeted or vulnerable CSOs and activists; and to defend our common space more effectively. To do this well, we must adhere to the principles of feminist leadership and movement-building, including investing in strong capacities and mechanisms for managing internal differences.

Alliances should be as broad and inclusive as possible – including formal and informal civic actors with various identities, faith-based organizations, trade unions, media, universities, business associations, community groups, online activists and others. These alliances often need to be unbranded to provide space for diverse actors. Working in diverse alliances to protect and strengthen civic space enables civil society actors to protect the most targeted or vulnerable CSOs and activists; and to defend our common space more effectively. To do this well, we must adhere to the principles of feminist leadership and movement-building, including investing in strong capacities and mechanisms for managing internal differences.

New activism and tactics

Civil society actors need to explore new strategies and tactics that are effective within shrinking and shifting spaces to contribute to transformative change. Particularly, informal (youth) movements have shown high flexibility and creativity in exploring new ways and spaces to organize and express themselves. The International Youth Day 2017 gives a flavour of this creativity. A Café Politico in Honduras, a Facebook live programme with a top-level government official and rural youth in Bangladesh, a PechaKucha event in Somalia and an animation video to share the Global Youth Manifesto to End Inequality are only a few of the initiatives around the world to provide young people a platform to express themselves. Connecting to and learning from these actors can help more institutionalized civil society organizations refresh their ways of working so that they can still achieve their visions within contexts of shrinking and shifting spaces.

Diversity and solidarity

As civil society, we must ensure that our space is open for all people. This requires valuing diversity, expressing solidarity across groups with various identities and agendas, and challenging any forms of discrimination based on gender, age, sexual orientation, ethnicity, nationality, and other identity traits within our own ranks, the broader society and the government. Powerful international and national organizations must ensure that they do not take the  space of less powerful or more critical activist groups. Influential organizations should instead use their power to give less powerful actors access to their networks and support them in building capacity to raise their voices.

space of less powerful or more critical activist groups. Influential organizations should instead use their power to give less powerful actors access to their networks and support them in building capacity to raise their voices.

An inspiring example can be found in Tunisia. Following increasing violence against individuals and associations among the LGBTQI community in 2015, the ‘Collective of Individual Liberties’ was formed, involving LGBTQI associations and activists as well as feminist and human rights associations. In 2016, the Collective supported the LGBTQI community in celebrating May 17, the World Day Against Homophobia and Transphobia. Turning from secrecy to an open event, the day was an important milestone for the LGBTQI community to create public awareness for their struggle.’

I would have liked to see more in depth case studies, but I guess the whole point about resisting shrinking civic space is that it’s hard to talk about without putting people at additional risk.

I’d appreciate suggestions for further reading, in particular on how CSOs and others are adapting and evolving in response to the crackdown.

The post How can Civil Society respond to government crackdowns around the world? New Oxfam paper (and hello to Oxfam GB’s new boss) appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 10, 2018

Nostalgia, fragility, age and management consultants: 4 Scandinavian conversations

A couple of weeks ago, I spent a day in Sigtuna, a lovely lakeside town just outside Stockholm, doing my usual blue sky/future of

tough gig

aid thing with big cheeses from the 5 Scandinavian protestant church agencies of the ACT Alliance. The ensuing conversations were full of lightbulb moments, including these four:

Nostalgia as a political force: across the region, including in the Swedish elections on Sunday, a yearning for a largely-illusory past of rustic homesteads, pitchforks and whiteness is driving the rise of populist, anti-immigration movements like the Swedish Democrats or the ‘True Finns’. The same can be said of populism in the US or UK – it all took me back to Gil Scott Heron’s great song, ‘B Movie’ about the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan:

This country wants nostalgia

They want to go back as far as they can …

Even if it’s only as far as last week

Not to face now or tomorrow, but to face backwards

And yesterday was the day of our cinema heroes

Riding to the rescue at the last possible moment

And when America found itself having a hard time …

Facing the future, they looked for people like John Wayne

But since John Wayne was no longer available, they settled for Ronald Reagan

The past is over-rated

The Left has its own nostalgic narratives of course – in the UK, they often pine for the clarity of the post war Labour government setting up the NHS and nationalising coal. But overall, they seem to be losing the Nostalgia Wars. Anything good to read on the origins and politics of nostalgia?

Working on Fragile and Conflict-Affected settings: Should aid agencies allocate more money and effort to working in FCAS, and what should they be doing differently there?

Arguments for greater priority: that’s where the poverty is/will be; where the aid money will go; any success will be likely to replicate as other organizations pick it up

Arguments against: much harder to get results in FCAS; greater risks to staff and partners, especially where being foreign is politically toxic (an increasing number of countries)

What kind of work makes sense in FCAS? Humanitarian response; thinking more about power and public authority beyond the state (eg the role of faith leaders in the case of ACT). Positive deviance approaches often make more sense when everything else fails.

What are the relative advantages/disadvantages of doing advocacy/campaigns with young v older people? I’m always sceptical of unthinking ‘we must do more with youth’ statements, but the conversation went deeper than that:

Why work more with youth? They move fast, are connected and creative, so you can get rapid and large scale change on things like norms and behaviours, and loads of new ideas. They are more ready to mobilise in public, if that’s the nature of your campaign. What’s more, if you change the behaviours of a 15 year old, you get results for a lot longer than with a 70 year old!

than with a 70 year old!

Why work with older people: they are better connected, have more knowledge of power and how advocacy targets like companies or the state work; they may stay with the campaign longer than young people whose lives are going through rapid change (college, work, babies).

Should CSOs partner with Management Consultants? An increasing number of large bilateral aid contracts (DFID, USAID) is being channelled through Management Consultancy companies, who have set up aid management arms – the kind of thing I was looking at in Tanzania recently, with a consortium run by Palladium. When they are putting together their bids, many approach CSOs to join their consortium. How should CSOs respond? How do we sort out the companies with a genuine commitment to development from the purely profit-oriented? Could someone put together a questionnaire for the top 20 aid contractors and publish the results? I tweeted a request for advice and which questions to ask and got the following:

‘Watch out that you are not being used as bid candy. Insist on full disclosure of the whole bid.’

‘Do they transparently pay their taxes around the world? Do they make a lot of money helping others not do that? Do they shame the memory of a major Scottish economist and philosopher [can’t think who that refers to….]? Do they have a track record of building capacity in-country, or of extractively profiting?’

Talk to another contractor, compare offers; Beware overlapping partners; Have defined, project-critical outputs beyond year 1 & key named personnel.

Questions around transparency, and whether there are any domestic firms from partner countries involved in the consortia.

Give us (at least) two references, that we can follow up, from CSO partners who have worked as part of consortia with you, and with the specific staff members leading this bid.’

Any other suggestions, or offers to take on the questionnaire idea?

The post Nostalgia, fragility, age and management consultants: 4 Scandinavian conversations appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 9, 2018

ICYMI: Highlights of this summer’s FP2P posts

reason at the start of June and was only finally fixed last week. Now the notifications are back up, here’s an annotated guide to what you missed. 3 months-worth of posts is a hell of a lot, so I’ll divvy it up into month-sized chunks. Here’s June.

A very informative punch up on Community Driven Development: after I reviewed a critical evaluation by Howard White and Radhika Menon, CDD guru Scott Guggenheim responded. Howard and Radhika came back swinging and Scott tried to find some common ground/have the last word (he succeeded).

A lot of discussion of Adaptive Management (aka Doing Development Differently) prompted by a week teaching about it in Bologna, which generated 7 suggested rules of thumb for AM. Chris Roche and Alan Whaites chipped in.

Religion always gets people going. Praising the role of missionaries in development prompted a lot of comments, and DFID is keen on tapping into religious giving.

Some book reviews: Dan Honig’s ‘Navigation by Judgment’, and Sarah Corbett’s ‘Craftivism’

Inequality: The World Inequality Report 2018 and the data geeks have forgotten the politics (again). And Save the Children’s Kevin Watkins with its latest wheeze to reduce child inequality (‘convergence pathways’, since you ask)

Some LSE-related stuff: Report back on my first attempt at teaching LSE students to be campaigners; a seminar in Ghent was a bit mind-numbing, but the highlight was seeing Power through the eyes of a dead Congolese fish

Lots of links I liked, which I’ll spare you, and some random other stuff

What will the aid jobs of the future look like?

The rise of the robots

Oxfam’s Tim Gore discussed the evolving theory of change behind its new Behind the Bar Code campaign

The Economist on the Retreat from Democracy

Complicated v Complex – why it matters

Latest Humanitarian Aid stats

Ed Cairns wins his argument with me on non-violence as a driver of a change

Oxfam Ghana’s Mohammed-Anwar Sadat Adam on how NGOs are adapting to funding falls

Latin American thinktanks’ experience of evidence for influencing

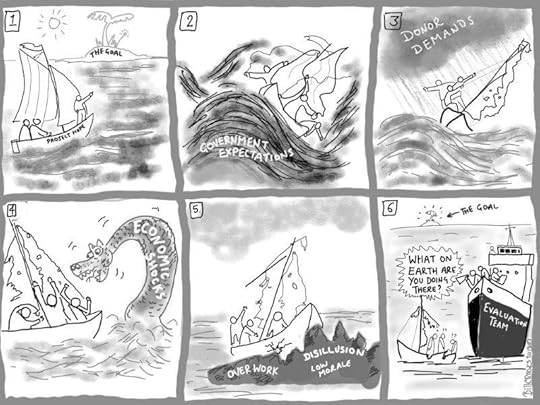

And finally, a funny on the project cycle and complexity

The post ICYMI: Highlights of this summer’s FP2P posts appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 6, 2018

So three years in, what do we know about the impact of the SDGs?

recall, I was a massive SDG sceptic in the run up to their creation in 2015 (here’s a summary of previous rants, with links). Now I want to see if my scepticism needs to be moderated/abandoned.

My main concern back then was that the SDGs were never designed to influence government behaviour. For example, there was almost no research on what aspects of international agreements (e.g. UN & ILO Conventions) get traction on national governments, and there was hardly any serious research on the impact of the MDGs – people basically said ‘ooh look, poverty has halved, the MDGs are a success’. Causation v correlation anyone?

In the absence of evidence or discussion on how to design for national impact, the SDGs were drawn up as a laundry list for lobby groups, and a happy hunting ground for the data geeks that drove the creation of the MDGs, but what practical difference were they likely to make?

But now I hear lots of stories of the SDGs being picked up by CSOs, governments, companies and others – is it hype or are they actually leading to those players doing something they would not have done otherwise?

So I appealed for things to read via twitter, and here’s what I found – please add ideas and references.

The most useful thing I’ve read was ‘The SDGs in middle-income countries: Setting or serving domestic development agendas? Evidence from Ecuador’, by Philipp Horn and Jean Grugel, a paper in the World Development journal. Based on a load of interviews with government and other players in Ecuador, they found:

‘The SDGs are not determining what Ecuadorian development means. They are, rather, legitimising development goals and policies that have already been decided on.’ Ecuador has picked two SDGs (10.2 on reducing group inequalities and 11 on inclusive cities), and sees the SDGs both as a way to validate its own priorities, and to tell the rest of the world about its work on these areas (particularly interesting on disabilities – the president is a wheelchair user, and the country has done some impressive work in the area).

‘Poverty halved, so the MDGs were a success’

National and City governments have both picked up the SDGs and used them to highlight different approaches to development. Quito city government has challenged that national administration by using a more private sector-friendly approach to urban development, and saying ‘why are you only talking about disability on inequality – what about indigenous people?’ (The government had big fights with Ecuador’s indigenous movements, so chose to focus on disability under the inequality SDG).

More broadly, they conclude that the impact of SDGs is more on norms and debates, a ‘looser script’ than the MDGs.

Elsewhere Shannon Kindornay, Javier Surasky and Nathalie Risse read through 42 country ‘voluntary national reviews’ of their progress on the SDGs, two years in, along with relevant civil society reports (some people have all the fun….). Among other things, their report found that most reporting countries had in some way incorporated the SDGs into national development plans, had set up some kind of institutional oversight (eg committees headed by a cabinet member) and selectively reported on the SDGs they cared about.

Other snippets: Somaliland, which is not even a signatory, has integrated them in its new development plan. Then there’s the impact in the Global North – the SDGs are explicitly universal. Accordoing to the Brookings Institution.

‘In recent weeks, New York City declared it will be the first major city to report directly to the United Nations on its progress toward the relevant economic, social, and environment targets for 2030. This came shortly after an array of Canadian federal ministers emphasized the goals’ importance both domestically and internationally. Meanwhile, in the big leagues of business, many of the world’s foremost institutional investors have indicated (e.g., here, here, and here) they are considering integrating the SDGs into their investment processes. Even Kanye West, the celebrity artist, posted the 17 goals for his 28 million Twitter followers, to many people’s surprise.’

What do I take from all this? Maybe I was too harsh – the SDGs are showing signs of having a drip drip influence that is dispersed and hard to pin down. Lots of spin and lip service, but some impact, albeit softer, more pervasive and harder to measure than ‘have you halved X?’ The SDGs seem to fit a diverse, multipolar world where development priorities are quite rightly decided at a local level, not imposed from outside, and being being subsumed into national politics in different ways in different places.

But that still doesn’t answer the question of why we should devote so much time and attention to the SDGs, when other international instruments are more binding (ILO and UN Conventions). I have still have seen nothing that compares the SDGs against all these other agreements in terms of their impact on decision makers.

Over to you.

The post So three years in, what do we know about the impact of the SDGs? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 5, 2018

Tanzania is about to outlaw fact checking: here’s why that’s a problem

Experts say it took just four minutes from beginning to end. First, some sensors failed. Then the pilots lost control of the plane, it stalled, went into freefall and smashed onto the surface of the Atlantic Ocean at a force 35 times greater than that of normal gravity. None of the 228 people on board Air France 447 from Rio de Janeiro to Paris on May 31, 2009 survived. The tragedy that unfolded that night was triggered by failed airspeed sensors. Without the air speed reading, the computer systems failed and the pilots, flying literally data blind, were unable to regain control of the aircraft.

Statistics are society’s sensors. Independently collected, processed, disseminated and debated, they are vital to the health of a country. We supress, fabricate or ignore them at our peril. At the risk of stretching the Air France 447 example to breaking point, sensory failure can be fatal.

Amending Tanzania’s Statistics Act

The parliament of Tanzania is considering a Written Laws (Miscellaneous Amendments (NO.3) Act 2018. It contains nine substantive amendments to the Statistics Act 2015. Most are positive – for example the offence of publishing statistics that are “false” or “may result to the distortion of facts” has been removed. But one proposed change is truly alarming. The amendments introduce the following new text in Article 24A(2):

‘A person shall not disseminate or otherwise communicate to the public any statistical information which is intended to invalidate, distort, or discredit official statistics.’

Sorry, that’s illegal now

Should this Article pass unchanged, if any official statistics happen to be incorrect (or even just disputable), then pointing out the problem and correcting it will be illegal. Any commentary querying or challenging official data would arguably be illegal under the amended Act, regardless of whether such commentary was correct or not. Indeed, this clause effectively outlaws fact-checking, unless any fact-checking confirms that the facts being checked are correct. Further, publication of any statistical information that contradicts, or merely cast doubt on, official statistics, could be prohibited under this amendment.

The value of independent statistics

Independent statistics can save lives. The Ramani Huria project has mapped poor, flood-prone areas in Dar es Salaam for flood modelling and therefore better upkeep of the infrastructure, improved warning systems, and improved and more accurate response in event of a flood crisis. Under the proposed amendments to the Statistics Act, these independently produced maps and the potentially life-saving information they contain could become illegal.

Independent statistics – when credible and transparent – can help boost the economy. Small business retailers are important to Tanzania’s economy, and could also be an important source of revenue. But, according to a 2017 report, “there are no official statistics on the number of small business retailers in Tanzania. However, secondary research data … indicates that the Total Addressable Market (TAM) is quite large and unpenetrated: one interviewee made a rough approximation of between 350,000 and 500,000 small retailers in the country.” These numbers would not exist were they not collected – and made public – by independent (non-state) entities.

Independent statistics, or data collected using methods pioneered by non-state actors, can improve inclusiveness. A recent water point mapping (WPM) exercise carried out jointly by the World Bank and the  Tanzanian government and inspired largely by WPM methodology developed by WaterAid, helped to make a strong case that the resources mobilized during the first phase of the Water Sector Development Program (2007-2014), which increased Tanzania’s spending on water by a factor of four, had not led to the anticipated improvements in access to clean water. This motivated reflection by government and donors to ensure that future investments would have their desired impact. In addition, the government has recognized that WPM data can be a useful input to identify wards and villages with the greatest need and opportunity.

Tanzanian government and inspired largely by WPM methodology developed by WaterAid, helped to make a strong case that the resources mobilized during the first phase of the Water Sector Development Program (2007-2014), which increased Tanzania’s spending on water by a factor of four, had not led to the anticipated improvements in access to clean water. This motivated reflection by government and donors to ensure that future investments would have their desired impact. In addition, the government has recognized that WPM data can be a useful input to identify wards and villages with the greatest need and opportunity.

Governments benefit from understanding what citizens say they want and need. Unfortunately, those sentiments are almost never accurately captured in official data and statistics. Afrobarometer surveys inform government policy-makers about what citizens want. Of course, this does not always mean that policy-makers will decide to prioritize goals in exactly the same way, because of competing opportunities and constraints on policy-making and implementation. But without this feedback, governments may be surprised by negative reactions to their efforts. While public sentiment is often expressed in other ways than public opinion surveys — such as through protests, social media, etc. — the discipline of rigorous independent statistics allows researchers to be sure that such opinions actually represent the views of a larger population and to identify differences of opinion within key segments of the population.

Independent actors can fill crucial gaps in how public service delivery is monitored. This example from Uganda is instructive. In June 2003, the results of the first directly observed study of teacher attendance in a national sample of 100 Ugandan schools was presented to the Ministry of Education. The data revealed that more than 1 in 4 teachers, who were supposed to be in class, was away from school. The unanimous official review was that the methodology was invalid and the problem was nowhere near as large. Three years later, in May of 2006, another

anyone seen teacher?

independent national survey of schools yielded similar results to the 2003 survey. This time the review was mixed. A reluctant minority of officials acknowledged the problem. By the beginning of 2008, the ministry started discussing teacher absenteeism as an important challenge in service delivery. In May 2018, the Office of Prime Minister announced an initiative to use biometric machines and monetary penalties in 20 pilot districts to address the problem of teacher absenteeism. This example suggests that the government agencies responsible for teacher supervision are under-resourced and/or reluctant to publish embarrassing statistics. But, independent statistics can help reform-minded colleagues in government to act in the interest of development and their people.

Avoiding disasters through statistics

There is little visible drama in the lives damaged by flooding, poor access to clean water, or even teacher absenteeism, when compared to the instant tragedy of the AF 447 disaster. However, the underlying principle is the same: all sorts of disasters can be averted and avoided when decisions about what to invest in are informed by as complete a set of data and statistics as can be mustered.

Official statistics alone are a small and incomplete part of the full picture. Independent statistics make a huge difference. We need them to get a more accurate reading of our airspeed and to ensure there is sufficient lift under our collective wings. Amendments to Tanzania’s Statistics Act must promote, protect and defend independent statistics.

The post Tanzania is about to outlaw fact checking: here’s why that’s a problem appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 4, 2018

Should the UK (or other aid donors) ‘hold its nose’ and support an unjust end to civil wars?

There was some jubilation recently in South Sudan and amongst war-weary diasporas when the two leaders of the factions who have been driving the brutal conflict signed a peace agreement. Despite efforts from many including the UK Government to include a wider diversity of voices in the process, regional players pushed for an agreement so that at least the extreme violence may stop. This was the archetypal ‘elite bargain’ between two belligerents. However, I am sceptical about how sustainable the peace will be, especially when the whole country is still awash with arms, and so many key groups were excluded from the process.

That scepticism also applies to recent changes in UK foreign policy. Earlier this year, the UK Government published a review of their work on Elite Bargains and Political Deals. The extensive study concludes that making peace without placating the elite is likely to fail. Policymakers echoed the message – we need to embrace the politics of conflict, and to prioritize politics over stabilisation and technocratic state-building. Conflicts rarely – if ever – have military solutions.

Speaking about the Study’s conclusions at Chatham House, the Minister for the Middle East and for International Development, Alistair Burt, admitted that “There will be times when we have to hold our nose and support dialogue with those who oppose our values, or who may have committed war crimes.”

Elite bargain + nice suits

Surely this isn’t new. The British Government has a long history of supporting unsavoury groups and individuals (including some governments). It would be hard to argue that bilateral relations with Egypt and Saudi Arabia are centred on rights and democracy, rather than politico-economic interests of elites and UK national security.

With Brexit looming, the UK looks to be re-defining its role in the world. Are we being prepared for a British foreign policy 2.0, where (British) stability and security come at the expense of rights in conflict affected countries? I’m sure it’s tempting to go for the short-term satisfaction of making a deal with the (often unsavoury, and nearly always) guys at the top. That may reduce immediate, large-scale violence, but often reinforces inequalities and authoritarianism in the long run – and in the end that leads to more fragility and conflict, as whole groups (particularly women and girls) are systematically excluded in these undemocratic contexts, stoking the fires of resentment and unrest.

Development is about power, and its progressive redistribution from the haves to the have-nots. As the UN grapples with the New Ways of Working, and works with the World Bank on the Nexus between conflict and development in search of pathways for peace, we ask ourselves where does this leave the agency of those most affected by conflict? If we define development as “the freedom to be and to do” – are elite bargains really contributing to human development? Where do elite bargains leave human, civil and political rights and the agency of local actors? In the aid sector, we strive to be as local as possible and as international as necessary – should the same approaches apply to UK’s support to sustainable peace?

What we can agree on is that we need to work politically, and to better analyse formal and informal power of elite

Not at the table

bargaining. And that this needs to be done through a gendered lens – to better understand how different groups perceive and experience conflicts in their societies, and the structures and institutions (or social norms) that drive conflict and perpetuate inequality. We know that in conflict affected contexts informal power structures are key. Decisions are often not made by courts, policy not set by parliaments. Instead most power is held by vested interests (i.e. war lords, elites, other states, or private sector actors) – the majority of whom are older men. Supporting communities in stabilization and development means a deeper understanding of informal power – at all levels (not just at the top).

Whether you think it’s time to even up peace deals and make them more inclusive, democratic or whether you agree with the Government that more emphasis on elite politics and bargaining is needed – what is clear from the report is that there are losers in elite bargains. Transformative women’s rights are too often off the agenda, while evidence shows ceasefires and peace agreements are more likely to be sustainable if women are meaningfully involved.

For many years, serving as a multi-lateral diplomat, I was often the only woman in all-male meeting rooms discussing peace and security across Europe and its neighbourhood. The European community ranks among the highest in human development, yet the higher level the peace negotiation, the fewer women are in the room. While commitments have been made, too many Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) conflict mediation measures are not representative of those affected by conflict. When those negotiating political issues (especially political economy) are not accountable to those they claim to be negotiating for – the deals are often hollow, benefiting the few – not the many.

At what cost?

The UK Government’s Stabilisation Unit’s paper on ‘Elite Bargains and Political Deals’ seems to posit a trickle-down theory of peace-building, whereby peace agreed by people at the top will result in stability and reduction of violence that benefits poor and marginalized communities that have likely been denied a seat at the negotiating table.

But can trickle-down economic models really be applied to sustainable stabilisation and peace? A trickle-down approach tends to leave out inclusive, local agency (freedom) representation and participation. What happens when the elites we are bargaining with do not represent the population (in any way)? Even in cases where elite bargains initially reduce violence through “illiberal peace” – in effect consolidating authoritarian systems, fragility often persists, making the recurrence of conflict likely.

As an organization that works with power, Oxfam has campaigned against the elite capture of politics and resources – including in conflict contexts. As the UK reviews and redefines its foreign policy, including aid, we hope it finds more ways to both engage elites and hear and empower those most affected and most voiceless in conflict.

The post Should the UK (or other aid donors) ‘hold its nose’ and support an unjust end to civil wars? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 3, 2018

Some Exciting Progress on Governance Diaries

no illusions that anyone is actually listening. The best I can hope for is usually that a couple of people express mild interest in an idea, before it floats off into the abyss to join all those other forgotten/ignored brainwaves.

So imagine my excitement when one idea – Governance Diaries – actually got somewhere, thanks to the enterprise of Anu Joshi and colleagues at IDS and Oxfam.

As with many ideas, I suspect, this one came up in a bar, in Yangon in September 2016. Anu and I were mulling over research ideas in Fragile, Conflict and Violence Affected Settings (FCVAS) for the new IDS-led research program, Action for Empowerment and Accountability, in which Oxfam is a partner. As we were chatting, I remembered a book that had a big impact on me, Portfolios of the Poor, which sent researchers to interview the same families every couple of weeks for a year, building trust and slowly uncovering a hitherto unknown ecosystem of financial management. Why not apply the same approach to other issues, like governance? I blogged about it, and then moved on.

Not so Anu, who is one of those entrepreneurial academics who spots ideas and makes them happen. Two years on, she is managing a 3 country governance diary programme, which will shortly start publishing country case studies and methodology papers. In each of them, local researchers are interviewing a number of families every month over a period of 6-12 months. I talked to some of the lead researchers to get a sense of how the work is evolving.

The Inspiration for Governance Diaries

We mainly talked about methodologies, not findings, because they are still processing the interviews (but they did mention a few initial discoveries – see bottom of this blog). Some headlines:

The link to fragility and conflict: Diaries seem particularly well suited to messy places like FCVAS. Why? Partly because they are a cheaper, less risky alternative to standard ethnography. Instead of sending in some foreign anthropology PhD, Diaries work with local students and academics who already speak the language and enjoy a degree of trust in the community. They can come and go (handy if the security situation fluctuates) and are generally less obvious than foreigners.

But that doesn’t mean that diaries are risk free (which is partly why I’m not going to give the names of the countries). In all three, governments increasingly equate ‘research’ with ‘opposition’. ‘At the beginning, the local leaders used to follow us, and want to sit in on the interviews to know what we were asking about. So we started interviewing them to socialize the research, asking them what questions we should be asking.’

Due to concerns about risk, initial ideas of asking people to keep their own diaries had to be abandoned – not a good idea to have such things lying around the house.

Not one, but a basket of methods: The questions and methods have evolved over time, not least because both researchers and families got bored with repetition. Most recently, researchers have introduced visual prompts and institutional mapping, asking people to draw on sand or write on cardboard to show the institutions they turn to when they need to resolve a problem. All of the countries are using Nvivo, while in one, Oxfam is also using Sensemaker. There is lots of data to analyse – hundreds of interviews, interview transcripts and researcher notes in a range of languages.

It takes time: The researchers agree that it takes 3 or 4 rounds of interviews, before everyone relaxes and

The institutions that matter: state; God; hospital; family; NGO; healer; Prophet

starts opening up. OMG. How many research exercises go back to the same people more than once or twice?

There’s a whole methodology required to work successfully with local researchers: They have local

knowledge and the trust of the interviewees, but that has its downsides:

‘They take a lot of things for granted, because they’re from there. We have to ask local researchers to imagine they’ve just arrived from Mars and need to observe and take notes on everything. In one area, they were interviewing a widow. They noticed she had bread and water and said. ‘oh no, I wasn’t eating it, I was just looking after it’. I asked them why they wrote it down, and they said in this area if you’re poor, you eat bread with water, so she was trying to hide her poverty.’

And a taste of some of the findings?

There are a multitude of public authorities: ‘In one place, people (due to a natural resource project) set up a committee that became a community-based organisation. This is becoming a kind of boss of the area – instead of going to the state, or the natural resource companies, everyone goes straight to the committee. One of the local chiefs was replaced because of the noise created by the committee – it has links to the provincial government, two levels higher up, and uses Facebook and social networks.’

Diary of a Victorian Child Worker

Diaries expose previously unknown conflicts: In the same location, ‘We wanted to compare resettled families with a control site of families who were there before: one of the big surprises was that resettled families are better off. Tension is now emerging between the two groups. The original inhabitants see the electricity lines going straight past their houses to the resettlement. People have a saying for that – why have we been bypassed?’

Debt levels can be extreme and complex: in one household where the husband died, they owed money, so his widow repaid the loan by ‘giving’ her eldest (12 year old) son to the lender as a servant. Most debts seem to be with relatives or kin groups. And the people who lend the money know they won’t be able to repay, but do so anyway due to social bonds – a form of informal social protection. ‘They are your safety net, the place where you go to when things go wrong.’

Health care is erratic: ‘Poor people don’t go to the same person more than once. We’re not sure why – maybe they can only afford to go private once, or they change because the last person didn’t work, so they try something else.

Can’t wait to read the full findings as they emerge, and promise to link here when they do

The post Some Exciting Progress on Governance Diaries appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers