Duncan Green's Blog, page 86

September 26, 2018

Should Positive Deviance be my next Big Thing?

conversations, including one earlier this week with Oxfam’s Irene Guijt and some PD fans at the Said Business School (here’s their rather good report of a PD conference back in 2010, from which I nicked the box comparing PD with the ‘standard model’).

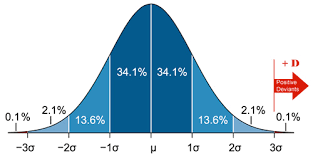

First some background: The starting point of PD is to ‘look for outliers who succeed against the odds’ – the families that don’t cut their daughters in Egypt, or the kids that are not malnourished in Vietnam’s poorest villages. On any issue, there is always a distribution of results, and PD involves identifying and investigating the positive outliers, and seeing if/how the lessons of how they did better than the rest can be spread. In the famous case in Vietnam, identifying slightly different feeding practices in outlier households led to big nutritional improvements for millions of kids.

This differs from the ‘standard model’ of aid in two big ways: it focuses on success, not failure/problems – places where the system has thrown up solutions to a given problem – and it replaces, or at least minimises, the role of ‘external interventions’ such as aid projects. Bye bye White Saviour complex/salvation by outsiders. For that alone, I love it!

This differs from the ‘standard model’ of aid in two big ways: it focuses on success, not failure/problems – places where the system has thrown up solutions to a given problem – and it replaces, or at least minimises, the role of ‘external interventions’ such as aid projects. Bye bye White Saviour complex/salvation by outsiders. For that alone, I love it!

So is this something I should work on? There’s not much point in just writing a book about PD – it would be pretty impossible to improve on the wonderful Power of Positive Deviance. Instead, what I have in mind is some kind of attempt, by Oxfam or a group of organizations, to put PD into practice and see what happens.

In many ways, this would be a natural extension of systems thinking and adaptive management: outsiders keen to promote positive change hold back from jumping in with their projects and devote time and resources to identifying the positive outliers on whatever issue they are interested in.

Then what? PD purists argue for ‘social learning’: the role of outsiders is only as facilitators, helping local people identify the outliers and learn from them. That bumps up against the political economy of the aid business – there’s no projects, nothing to raise money for, it’s just about supporting the few rare souls that have those subtle skills of facilitation.

That may help explain why Positive Deviance is not itself a Positive Deviant – there is a Positive Deviance Initiative, linked to Tufts University, which is dedicated to spreading the PD message, (eg via this handy biannual newsletter, but it really hasn’t caught on, at least not in the aid business. If any organizations have put it into practice, I would love to hear about it.

linked to Tufts University, which is dedicated to spreading the PD message, (eg via this handy biannual newsletter, but it really hasn’t caught on, at least not in the aid business. If any organizations have put it into practice, I would love to hear about it.

So rather than see PD as a complete alternative, might it be better to use it to improve current practices? Eg using PD as a way to incubate new ideas (thanks Irene for that idea!) or a form of due diligence – any organization embarking on new work, whether in terms of theme or location, should start off with PD to see what is already working and why, no matter how limited the successful example is.

This suggestion may horrify the PD enthusiasts, who fear that ‘projectizing’ PD would destroy its true nature, and I have some sympathy with that, but how else can we bring such a brilliant idea into the mainstream?

When I’ve discussed PD with Oxfam colleagues, they’ve raised some other important concerns:

Isn’t PD essentially accepting the status quo (albeit the best bit of it)? Rather than transform society, we are going to spot families that feed their kids a bit better and spread the word. Does that come at the expense of more radical, structural change?

How to stop PD becoming a new fashion, with people sprinkling it over their documents but not really changing how they work? Already I’m seeing the term cropping up in more and more conversations and documents (a bit like ‘adaptive management’!)

How to stop PD becoming a new fashion, with people sprinkling it over their documents but not really changing how they work? Already I’m seeing the term cropping up in more and more conversations and documents (a bit like ‘adaptive management’!)A lot of people seem to think they’re doing it already. After all, a lot of the restaurant conversations in aid circles starts with ‘I saw this amazing thing happening in this village/organization’. What’s the difference between that and PD?

Does PD really only work with a large ‘n’ – a big population where you can identify a clear distribution and its outliers? Does that mean it can’t be used with small ‘n’ problems like advocacy?

I’m struggling here, and it’s a big decision for me – whether to spend a lot of time on this, or do something else. Would really welcome your thoughts.

Previous posts on Positive Deviance:

Spotting PD in Kenyan primary schools

Book Review: The Power of Positive Deviance

Applying PD to PNG (Papua New Guinea)

Researching PD within a big Oxfam Savings project

And here’s Monique Sternin, one of the founders of the PD movement:

The post Should Positive Deviance be my next Big Thing? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 25, 2018

Links I Liked

An extraordinary piece of investigative journalism by BBC Africa uses all the digital arts to track down the culprits of an atrocity captured on an anonymous video – 2 women & 2 young children are led away by a group of soldiers. They are blindfolded, forced to the ground, and shot 22 times

‘More than half of aid spent on procurement still goes to rich countries’ firms – almost two decades after commitment to end ‘tied aid’’. New Eurodad report

Turns out gender inequality is bad for men’s health. ‘Living in a country with gender equality benefits men’s health: lower mortality rates, half the chance of being depressed, lower suicide rates, and a 40% reduced risk of violent death.’ WHO Europe briefing ht Pete Hennessy

A recording of my recent ‘research for influence’ webinar for On Think Tanks is now online.

Check out Participedia – ‘crowdsource, catalogue and compare participatory political processes around the world.’

If you want to stay up to date with our LSE team’s work on ‘Public Authority’, sign up here

Hard to think of anything more humiliating than having your absurd bragging laughed at by the world’s leaders assembled at the UN. I wonder what price the UN will have to pay? Oxfam America also delivered a powerful ‘not in our name’ rebuttal to the president’s address.

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 24, 2018

Self Reliance, Hip Hop, Resistance and Weapons of the Weak: do we need to rethink Empowerment?

A 3 day conference at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) inevitably makes you dig deep and question your assumptions, and last week’s gathering of the Action for Empowerment and Accountability research programme was no exception.

This time, presentations from Myanmar and Mozambique set me off. In Myanmar the researchers had expected to find communities opting between ethnic and state authorities, but found instead that many are intent on avoiding both – i.e. they are seeking self reliance. Trust is local, built on ethnicity, past experience (eg of individuals’ behaviour) and familiarity.

So say a community or a family succeeds in being left alone and managing on their own. Does that constitute empowerment? And what does that mean for accountability? It feels like our notions of Empowerment and Accountability (E&A) have somehow shrunk to looking at and valuing only what goes on in the public sphere – protests, voting, holding the state or other institutions to account.

In Mozambique some fascinating research into hip hop artists found that calling it ‘protest’ music misses a lot of what is going on. Their analysis of lyrics by ‘Refila Boy’ (blog to follow), and conversations with a range of musicians, identified issues like the value of catharsis; ridiculing and destroying deference to authority as well as complaining about daily problems like stirring up protests on corruption.

In Mozambique some fascinating research into hip hop artists found that calling it ‘protest’ music misses a lot of what is going on. Their analysis of lyrics by ‘Refila Boy’ (blog to follow), and conversations with a range of musicians, identified issues like the value of catharsis; ridiculing and destroying deference to authority as well as complaining about daily problems like stirring up protests on corruption.

Again, our understanding of E&A seems to only privilege stuff that happens in the public sphere. Calling the president ‘shorty’ in a song lyric, and having people sing along, is not seen as important in itself, only as a way to mobilize them.

From the sludge banks of memory, I dredged up a book I read a long time ago – James C Scott’s ‘Weapons of the Weak’ (1985) and his later book Domination and the Arts of Resistance (1992). Based on two years of field research in a Malaysian village, Scott identified ‘everyday forms of peasant resistance, the ordinary weapons of relatively powerless groups: foot dragging, dissimulation, desertion, false compliance, pilfering, feigned ignorance, slander, arson, sabotage.’ In the later book he developed his thinking on ‘hidden transcripts’ – ‘ a secret discourse that represents a critique of power spoken behind the backs of the dominant.’

My fear is that we have somehow lost that understanding, and allowed E&A to become synonymous with what are effectively ‘weapons of the strong’ – public acts such as voting, violence, public statements, lobbying and so on.

But in conflict-affected places, this seems a huge mistake – there, public opposition and action is all too likely to backfire, putting lives at risk. Isn’t it time to rethink empowerment and accountability, and the relationship between them? Surely feeling less scared, more defiant is itself a form of empowerment, and enhanced wellbeing, even if nothing else follows in its wake? We talk about ‘power within’ largely in terms of it being a necessary first step to public action, but shouldn’t we accept it as an end in itself, and think harder about the role of secrecy and resistance?

but is it empowerment?

Amartya Sen described development as the expansion of the freedoms to be and to do – a broad concept that would definitely include changes in the private world inside people’s heads. I think we need to make our understanding of empowerment equally comprehensive.

I’m even more confused about what all this means for our understanding of accountability. From Egypt we heard of nurses arguing effectively that E&A are in opposition: demanding accountability of doctors and patients in cases of sexual harassment of nurses would, in their view, undo efforts to establish nursing as a reputable job in the public eye.

John Gaventa listed the theories of accountability as covering access to Information; the rule of law; voting and the

social contract between states and citizens. None of those relate to private spaces, so does that mean we should separate empowerment and accountability altogether? Or think harder about private sphere accountability, eg in the household, or in the mind (am I being true to my values in thought and action?)

Discussions then touched on the potential downsides to a shift in this direction: is talking about the value of self reliance merely romanticising/accepting a survival strategy born of a lack of options? Accepting a status quo that is already full of inequality and violence? Is humour really liberating, or does it merely release the pressure for change through the kind of gallows humour that always flourishes under repression?

Not sure if this makes much sense, but I clearly have some processing to do – any advice appreciated!

And here’s a Refila Boy video as a reward for getting this far:

The post Self Reliance, Hip Hop, Resistance and Weapons of the Weak: do we need to rethink Empowerment? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 23, 2018

Are Big Companies Walking Their Talk on the SDGs? New report digs into the evidence

and Ruth Mhlanga introduce a new Oxfam report on business and the SDGs

Business has become a fixture in discussions around the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This week in New York we will see the familiar picture of executives of the world’s largest corporations convening around the UN’s General Assembly week for a series of high-profile events and conferences to discuss their contributions to the SDGs. If the past couple of years are any indication, we already know what we can expect – a presentation

of accomplishments and high-flying rhetoric on business’s willingness and ability to help tackle the world’s most urgent challenges. But is it true?

This year’s discussions will be accompanied by more somber undertones around the limited SDG progress to date (see here and here). Even voices close to the business community have called for a reality check on whether business engagement in the SDGs to date is sufficient. Three years into the SDGs, reliable information regarding companies’ uptake of and contributions to the SDGs remains patchy.

Also, business’ engagement in the SDGs can be difficult to untangle since there are no clear SDG expectations on business (making existing efforts difficult to evaluate) and many companies are already tackling issues relevant to the SDGs through their sustainability strategies (without labeling them as such).

Analyzing companies’ SDG engagement

So we took a look at public information on the SDG engagements of 76 of the world’s largest companies across six general themes: 1) their commitment, 2) how they prioritize areas of SDG engagement, 3) their level of integration of the SDG into business strategies, 4) the level of ambitions of SDG actions and targets, 5) the degree of linkage between a company’s SDG engagements and its commitment to respect human rights and gender equality, and 6) the level of transparency and quality of SDG reporting practices.

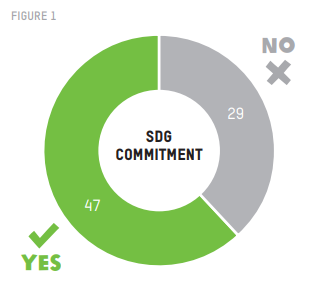

Figure 1

Overall, the report’s findings are sobering in terms of companies (not) translating their commitment to supporting the SDGs into meaningful changes and new ambitions. Beyond this headline finding, here are four takeaways that may (or may not) surprise you:

Uptake: most of the companies in our sample are (around two thirds) have made a public commitment to supporting the SDGs. Interestingly, some of the companies not embracing the SDGs are considered sustainability frontrunners in their sectors, highlighting how embracing the SDGs potentially can be more attractive option for sustainability laggards than leaders due to the ease by which companies can put any sustainability efforts under the reputational mantle of the SDGs. (Figure 1)

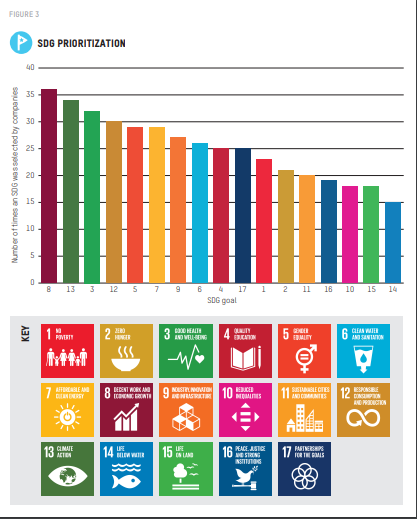

Prioritization: SDG priorities of companies mirror their existing sustainability priorities instead of shaping them. Companies’ recent uptick in support for climate action is reflected in our findings as well as their growing support of gender equality. Issues at the margins of the corporate sustainability agenda, such as business’ influence on inequality

Figure 3

or political institutions, are sidelined. (Figure 3)

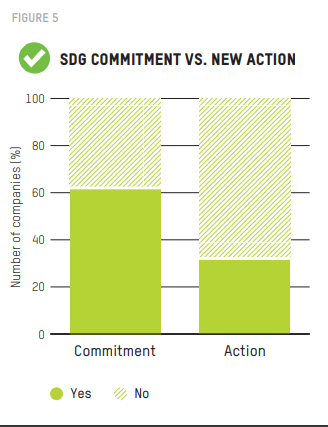

Ambition: Most of the contributions companies list in support of the SDGs pre-date the adoption of the Global Goals. Only half of the companies committing to the SDGs appear to be doing anything new (often discrete sustainability projects or new memberships) and only two companies in our sample adopted new targets in line with the 2030 timeline of the SDGs. Instead of sparking more ambitious efforts, the SDGs appear to have so far largely remained a communications tool. (Figure 5)

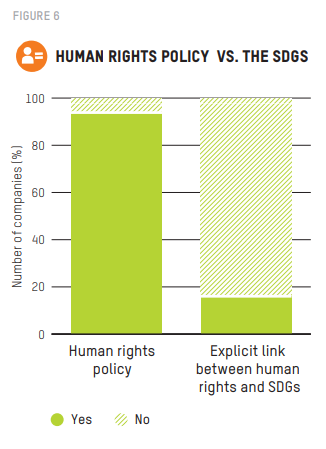

Human rights: Despite the strong link between human rights and sustainable development, few companies are marrying their human rights commitment with their contribution to the SDGs. Only five companies in our sample display a strong emphasis on human rights in their support of the SDGs (although the vast majority of companies has a human rights policy). This finding confirms the potential risk of SDGs evolving into a diverging direction from the Business and Human Rights agenda. (Figure 6)

Figure 5

The way forward

The SDGs have proved a difficult framework for business to grapple with. As they are vague, failing to set out clear expectations for business, companies looking for aspirations around the SDGs are trapped between the SDG targets (which are aimed at governments) and existing sustainability standards (many of them setting a very low bar).

To help move the discussion forward, we then went beyond our sample to identify promising practices as a guide for more meaningful SDG engagement by business. These examples range from initiatives that address core business practices relevant to the SDGs, such as the Living Wage Foundation or the Fair Tax Mark, initiatives that make human rights-focused contributions to the SDGs, such as the ACT initiative, and efforts to create universal expectations on business around particular SDGs and sectors, such as the World Benchmarking Alliance, which is launching this week.

The SDGs prompted hope that their ambition and collective vision

Figure 6

would mobilize business to a new degree and provide further momentum to efforts to more fundamentally align business models and strategies with sustainable development. The evidence to date doesn’t seem to validate this hope. Instead, our findings appear to confirm a broader trajectory of the corporate sustainability agenda, which over the years has become increasingly company-driven (vs. stakeholder-driven) and focused on a narrow ‘business case’ as primary motivator for companies to engage in sustainability issues. This approach is likely to disappoint our collective expectations of business’ contribution to achieving the SDGs.

The post Are Big Companies Walking Their Talk on the SDGs? New report digs into the evidence appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 22, 2018

FP2P round up, week beginning 17th September

Ok, well enough of you were enthusiastic for me to give this another go- here’s a summary of activity on FP2P over the last week. If I just talk you through the different posts, it seems to come in at 6-7 minutes. If you’d prefer something longer, that would probably mean actually summarizing the main points of each post – cd you let me know which you’d prefer?

Have a good weekend everyone

Duncan

http://oxfamblogs.org/fp2p/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/FP2P-audio-summary-wb-17th-September.m4a

The post FP2P round up, week beginning 17th September appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 20, 2018

Peace has a PR Problem: How would you fix it?

International Alert, explains why that matters.

Our dictionaries mirror what’s happening in society. And the words we use shape how we see events and how we act. So it’s a sad reflection that dictionaries are full of the words of war: from warmongering to terrorism, and yet ‘peacebuilding’ is so under-recognised that you won’t find it in a single English dictionary.

Luckily, it’s a joy of languages that they constantly evolve. Old words slink away, unused and unloved, to the back of the cupboard. Their place is taken by brash new words, springing up on our streets and in our tweets and richocheting around the world. Last year, for example, ‘hangry’ jumped into the dictionary – referring to people being so hungry that they become angry. Other newbies include ‘totes’, ‘adorbs’, ‘bingeable’ and, entering just last week, ‘instagrammable’. Peacebuilding is looking positively middle-aged at over 40 years, so what’s taking so long?

It is an oversight which 19 peacebuilding organisations have clubbed together to change. We’re campaigning to get peacebuilding recognised – supported by everyone from actor Mark Rylance through to the Middle East Minister Alistair Burt. We’re hoping for positive responses from the dictionaries to announce today, the UN International Day of Peace.

Sadly, the dictionaries are not the only ones giving the cold shoulder to peacebuilding, which we define as those activities that tackle the root causes of conflict and enable societies to resolve differences without violence. Politicians often don’t even know that such an activity – and so policy option – exists. They haven’t heard of peacebuilding in their daily lives, and so they don’t think about it when they get to power. Alternative responses to brewing violence overseas, such as sending in the fighter jets or ‘putting boots on the ground’, are well known levers to pull and have an appealing kinetic energy. When prime ministers want to look strong against dictators or jihadists, nothing looks quite as tough as a vast black machine taking off: Look at what we are doing, it screams.

Sadly, the dictionaries are not the only ones giving the cold shoulder to peacebuilding, which we define as those activities that tackle the root causes of conflict and enable societies to resolve differences without violence. Politicians often don’t even know that such an activity – and so policy option – exists. They haven’t heard of peacebuilding in their daily lives, and so they don’t think about it when they get to power. Alternative responses to brewing violence overseas, such as sending in the fighter jets or ‘putting boots on the ground’, are well known levers to pull and have an appealing kinetic energy. When prime ministers want to look strong against dictators or jihadists, nothing looks quite as tough as a vast black machine taking off: Look at what we are doing, it screams.

By contrast, peacebuilding seems too fluffy, too much motherhood and apple pie, too weak, too big, too slow, too worthy. Peace, it seems, has a PR problem.

And we urgently need to fix that as the world slides ever deeper into violence. As we speak, a record 68.5 million people have been forced to flee war or persecution worldwide. More people being killed in battle. More civilians, especially women and children, dying than ever before.

So peace is needed more than ever. Yet only US$10 billion is spent every year on peacebuilding, compared to an astounding $1.7 trillion in global military expenditure.

Serious as peacebuilders are, we’ve built up our evidence base. We know that peacebuilding is effective, and cost- effective – and popular. A just released public opinion poll conducted by International Alert with the British Council and polling agency RIWI across 15 countries from UK to Ukraine, Nigeria to the USA, found strong popular support for prevention as better than cure. Across the world, given choices, people ranked ‘dealing with the reasons why people fight’ top of their list of ways for governments to promote peace – way ahead of military, diplomatic or humanitarian options. Governments can look strong and win popular support by backing peace.

effective – and popular. A just released public opinion poll conducted by International Alert with the British Council and polling agency RIWI across 15 countries from UK to Ukraine, Nigeria to the USA, found strong popular support for prevention as better than cure. Across the world, given choices, people ranked ‘dealing with the reasons why people fight’ top of their list of ways for governments to promote peace – way ahead of military, diplomatic or humanitarian options. Governments can look strong and win popular support by backing peace.

Now we just need to win the argument with policy-makers. So it was that last week, I was sitting in the uber-trendy Lido Café in Herne Hill, surrounded by yummy-mummies, having a coffee with Duncan, both of us scratching our heads about peacebuilding’s low profile. What can we do to turn things round?

What have we done so far? First off, the world’s leading peacebuilding organisations have come together to put peacebuilding on the map by communicating better with the public. We know we have a problem that needs radical change to fix it. At a ‘Maniacal Business Attack’ (trendy US term for a two-day brainstorm) in DC last year, we looked at other transformative global campaigns inspired, for example, by how the gay rights movement won the day for marriage when they shifted from talking about equal rights to talking about love. Genius. So what’s the shift that we need to make to build a vibrant, modern, strong peace movement?

We haven’t yet had our breakthrough moment; we are still working away to find solutions. We know we need to tell our stories of impact better; to enlist the backing of the military; to engage the public better with our work; to bring in more celebrity support and more unusual voices. Duncan’s bacon buttie clearly getting the better of him, he suggested we enlist Jeremy Clarkson. I didn’t jot that one down – but I get his point: we need surprise supporters.

Duncan’s next bright idea was to write a blog, asking for people’s brightest and best ideas of how we could tackle peace’s PR problem. So here we are.

Credit: International Alert/Search for Common Ground

Meanwhile, as peacebuilders, we agreed to kick-off with getting peacebuilding into the dictionary. And today that step is at least partly accomplished. Harper Collins, MacMillan and Cambridge dictionaries have agreed to add the word. Harper Collins online dictionary are even making ‘peacebuilding’ their word of the day today.

Getting into the dictionary is just the first step. Next is to call on the UK government to step up its commitment to building peace, asking Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt to include concrete commitments to reducing violence in the ‘Global Britain’ strategy to be announced in March 2019.

We live in hope that, helped by your ideas, peacebuilding could hit the heights of ‘Word of the Year’. Recent winners have been fake news, populism, and austerity. Let’s hope peacebuilding can be next. That would be ‘totes adorbs’. And only possible if you get in touch with your ideas and offers of help…….

And here’s a short (2m) video summary of the public opinion research

The post Peace has a PR Problem: How would you fix it? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 19, 2018

Thumbs up or thumbs down? Did the Millennium Villages Project work?

Back in the mid-2000s, one project stood out as a bold attempt to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) at a local level: The Millennium Villages Project (MVP). Spearheaded by Professor Jeffrey Sachs, the project sought to demonstrate how the MDGs could be achieved through an integrated approach to rural development. For the past six years, I’ve been managing an evaluation of the MVP in northern Ghana, funded by DFID, to provide rigorous evidence about whether this approach to development really works.

Intuitively, the MVP made sense in many ways: do everything at once (health, education, agriculture, etc) so the effect will be far greater than a piecemeal approach of single, small-scale interventions. Not only that, but we do actually know what works in lots of areas: applying artificial fertiliser to maize rapidly increases yields, bed nets protect people from malaria-carrying mosquitos; vaccinations prevent disease.

As the former UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-Moon was quoted as saying said back in 2010: “Millennium Villages throughout Africa are showcasing… how effective an integrated strategy for health care, education, agriculture, and small business can be. We are seeing how to make the most of new technologies. And we are seeing how empowering women can empower whole societies…”.

So, lots of optimism… but, it’s been controversial.

Controversy seemed to peak around 2011 to 2013, which just happened to be when we started out in northern Ghana. Putting aside the more heated ‘war of words’, Michael Clemens and others were writing papers and blogging on the need f`or rigorous evidence (such as this Guardian blog, or putting the case forward that ‘rigorous impact evidence is not a luxury…’).

Controversy seemed to peak around 2011 to 2013, which just happened to be when we started out in northern Ghana. Putting aside the more heated ‘war of words’, Michael Clemens and others were writing papers and blogging on the need f`or rigorous evidence (such as this Guardian blog, or putting the case forward that ‘rigorous impact evidence is not a luxury…’).

So, here we are – more than five years later – bringing together evidence of the impact of the Millennium Villages Project (for northern Ghana at least):

Did the project have an impact? Well, yes and no.

No, in terms of achieving the MDGs at a local level (see MVP Evaluation Briefing 1). Certainly, for the key indicators for poverty (MDG 1) there does not seem to have been a reduction. There were income improvements that could be attributed to the Millennium Villages project, but there was no accompanying increase in consumption, and the improvements in income were insufficient to break the poverty trap. The population remains poor.

But yes, there were impacts. We found statistically significant impact against 7 of the 28 MDG indicators. For example, primary school attendance improved by 7.7%, intermediate health indicators improved for births attended by skilled professionals, children sleeping under bed nets, and so on.

Of course, assessing the project just against the MDGs is somewhat ridiculous. Rarely can a project achieve such high-level goals in a short period (although that is what the project set out to do), and the MDGs themselves are far from a definitive list of indicators. Nor indeed do they reflect the realities of people living in the area. So, there is lots of exploratory analysis that we cover elsewhere…

Does the project offer value for money? This is THE controversial one.

Caution needs to be applied when interpreting the analysis, as no direct comparison with similar projects was possible (see MVP Evaluation Briefing 3). Our analysis shows that the returns to investment in education appear to be highest, although both the returns in education and health could be achieved at a much lower cost.

projects was possible (see MVP Evaluation Briefing 3). Our analysis shows that the returns to investment in education appear to be highest, although both the returns in education and health could be achieved at a much lower cost.

Given that this was always intended as a demonstration project, we also undertook a sensitivity analysis to see if transferring such a project to local ownership could improve the value for money. Even with a 50% reduction in overheads however, there is questionable cost-effectiveness.

So, what can we conclude?

Certainly, achieving lasting change is difficult. The project’s over-ambitious aims (and often claims) made it the target for much disagreement. There were some good ideas, and things that worked well (for example, the tractor hire services, vaccinations, investments in health centres and school infrastructure). But it was starting from a low base of investment – as anyone who’s travelled to the very northern areas of Ghana knows – and it takes time.

Finally, a few things stand out for me about the Millennium Villages approach in northern Ghana:

Firstly, although many ‘quick wins’ had been scientifically tested (with rigorous evidence), the project seemed to underestimate the need for considerable experimentation in each context – working with the grain of local government and communities, as well as working with how people respond differently to interventions and adapt solutions. For example, people were not always using bed nets, finding hard at certain times of the year to reconcile the use of bed nets with the night heat. (As an aside, it is also surprising how many creative uses for bed nets there were, whether as screens for toilets or bathing areas, to protect young fruit trees, to cover store rooms, as pillows or bedding to lie on, as fishing nets, door curtains and sun blinds).

And secondly, sustainability is a huge challenge (see MVP Evaluation Briefing 9): Approaches like top-up allowances for education and health workers, new ‘super’ health facilities, and free ambulance services, etc., all had a measure of success, but were beyond what could be sustained locally. Spending by the project tended to focus on building infrastructure, providing supplies and extra staffing (‘things’) with insufficient attention to the behaviour change needed to create long-lasting impact. For example, the statistical analysis shows a sharp increase in the access to toilets (part of MDG 7), with toilets rapidly built during the last two years of the project – yet, the qualitative research highlights how people still preferred to go ‘free range’, under a ‘nice baobab tree’ or among rocks away from the village.

And secondly, sustainability is a huge challenge (see MVP Evaluation Briefing 9): Approaches like top-up allowances for education and health workers, new ‘super’ health facilities, and free ambulance services, etc., all had a measure of success, but were beyond what could be sustained locally. Spending by the project tended to focus on building infrastructure, providing supplies and extra staffing (‘things’) with insufficient attention to the behaviour change needed to create long-lasting impact. For example, the statistical analysis shows a sharp increase in the access to toilets (part of MDG 7), with toilets rapidly built during the last two years of the project – yet, the qualitative research highlights how people still preferred to go ‘free range’, under a ‘nice baobab tree’ or among rocks away from the village.

I am sure that for many readers of ‘From Poverty to Power’ this evidence only serves to reconfirm their perspective of development – the need to understand power, work with complexity, disrupt the system. But, I leave you with one challenge: would your chosen project or policy have fared any better if subject to robust evaluation? And, how do we know?

The post Thumbs up or thumbs down? Did the Millennium Villages Project work? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 18, 2018

Are fuel riots the food riots of the 21st century?

research consortium (of which Oxfam is a member), a new IDS paper on energy protests jumped out at me. Here’s the brilliant Naomi Hossain summarizing it in an IDS blog:

‘Modern life depends on fuel, even while tackling climate change means cutting subsidies for fossil fuels that mainly benefit the rich. Fuel riots are both common around the world and potentially politically potent, but it seems that we (researchers) are only just beginning to notice them.

Every seasoned researcher knows this: if there is no research on an issue, it is probably obvious, and in no need of analysis; trivial, and therefore not worth studying; or too difficult to study, and so will do your academic career no good.

A recent PhD thesis confirmed my perception that research on fuel riots is currently non-existent.

So as I started writing this blog to alert you of a new IDS Working Paper on energy protests in fragile contexts, I had a moment of proper panic: had I just spent several months, some very precious research funding, and lots of many people’s time on something not worth studying?

So then I googled “fuel protest”…

So then I googled “fuel protest”…

The top returns from the 3.2 million results included the following:

10th June: An Indian youth organization gave the last rites to their motorcyclesin protest at high gas prices

9th June: in Nepal, students staged a demonstration and threatened to burn an effigy of the Prime Minister in opposition fuel price hikes

8th June: Serbian drivers blocked roadsin protest at fuel price rises

7th June saw plans for a protest against tax increases raising fuel prices in Croatia

The crisis over fuel prices in Brazilappeared to be escalating after almost two weeks of protests: on 25th May Brazilian truckers abandoned their protests over high diesel prices after the President threatened to call in the army, and on 30th May Brazilian fuel protestors called for a return to military rule to sort matters out.

And this was just last week.

Today, I came across another example: truckers in China were protesting over the weekend about higher fuel costs, falling haulage and transportation apps which are squeezing their profits.

Clearly fuel riots / energy protests are something we should be sitting up and paying attention to.

Why has there been so little research on fuel riots and energy protests?

Well, there is some research, but it’s more focussed on environmental movements in the North – for example,  struggles against nuclear energy, fracking, the Alberta tar sands, and around the location of energy plants (so-called ‘NIMBYism’).

struggles against nuclear energy, fracking, the Alberta tar sands, and around the location of energy plants (so-called ‘NIMBYism’).

Perhaps (typically ‘liberal’ / progressive / left-leaning) researchers of contentious politics are inevitably biased towards popular struggles for sustainability or social justice?

Yet people often protest about fuel because they can’t afford to burn the fossil fuels they depend on in everyday life, and not because they want to protect the planet. And this larger family of contention around energy gets short shrift in the literature.

We didn’t set out to study energy protests; in fact we weren’t even sure they were a ‘thing’ at first.

What we did want to do was to find out more about ‘unruly’ protests in fragile settings, that is, places where political authority is fragmented or weak and conflict common.

We wanted to understand how and why people who otherwise lack power or the space for political expression sometimes manage to come together to claim or complain.

From our earlier work on food riots, it was clear that such protests were often triggered when governments failed to honour the terms of the ‘politics of provisions’, particularly when rises in the cost of living meant people felt unable to provide for their families.

But the briefest of surveys of the countries we were interested in, as part of the wider Action for Empowerment Accountability (A4EA) research programme – Egypt, Mozambique, Myanmar/Burma, Nigeria and Pakistan (and we added Zimbabwe, just because it is interesting) – showed each had had protests about energy in the past decade, and several had blown up into

Myanmar

major political events.

Myanmar’s startling ‘Saffron Revolution’ of 2007 was triggered by fuel price rises, as were Nigeria’s two weeks of riots in 2012. Mozambique saw unprecedented urban uprisings linked to fuel prices in 2008 and 2010.

The run-up to Egypt’s 2011 Revolution saw protests about fuel prices, which later returned to presage political turmoil at several other points in the past decade.

Both Pakistan and Zimbabwe saw protests about energy shortages, which in both cases contributed to political transitions.

We clearly needed to look a bit closer, and our working paper attempts to do that.

Throughout history and across the world, governments have known that failing to feed their citizens meant risking popular protests and a loss of legitimacy.

Will fuel riots have the same moral and political power?

We do not yet know.

But there are good reasons to believe they might.

There are definitely differences between protests over food compared to those over fuel: the poor suffer most from food price rises, while the rich use most energy, perhaps explaining why fuel riots display a cross-class character generally absent from food protests.

Yet people – and in particular urban low income people – depend on affordable transport to provide for their families, so that fuel prices are also seen as a moral issue.

And while most countries now leave food prices basically up to the market, fuel price subsidies remain important, particularly in authoritarian or hybrid polities of the kinds we were studying.

So while food riots kicked off all around the world when global food prices shot up in 2008 and 2010-11, fuel protests responded to distinctly national political events rather than international market prices – typically because governments were cutting subsidies in line with international institutional (IMF) reforms.

Ahead of the G7, ODI recently published research which finds that – despite commitments from the G7 and the G20 to phase out fossil fuel subsidies – G7 governments continue to provide at least $100 billion in subsidies to the production and use of coal, oil and gas.

So, perhaps these governments are well aware of the political (and social) costs and consequences of potential rise in fuel prices – will the countries I mentioned above take note and pursue similar policies to stem the protests they are facing?’

And Naomi’s also put together this very cool timeline of events in the A4EA priority countries of Egypt, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nigeria and Pakistan, covering 2007 to May 2018.

The post Are fuel riots the food riots of the 21st century? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 17, 2018

Here’s what we know about closing civic space – what other research would you suggest?

space’, so this blog sets out what we know of the research to date, and asks you for further suggestions.

The best place to start is a great new literature review by 9 IDS researchers, Here’s their summary, with some thoughts from me at the end:

‘A wave of closures of civic space has occurred around the world, notably in the last decade, but not all civil society actors are equally affected: the objects of new restrictions are typically groups and organisations from a liberal and human rights tradition, often aid-funded and with strong transnational links, as well as their allies in social movements, the media and academia.

Developing countries may have long established traditions of civil society, but formal organisations in the specifically liberal tradition proliferated after the end of the Cold War, with aid financing increasing rapidly during the 1990s and 2000s, particularly to service-providing actors.

The recent (gathering pace in the past five years, but in fact dating back to the War on Terror) wave of restrictions on civic space must be situated in the similarly relatively recent growth of such organisations in most developing countries.

Not all new regulations on civil society are unwelcome, even by civil society actors; without effective regulation, the rapid earlier expansion enabled inefficiencies and abuses. In principle, new regulations purport to strengthen the governance and accountability of civil society, and to assert national sovereignty over the development process.

Not all new regulations on civil society are unwelcome, even by civil society actors; without effective regulation, the rapid earlier expansion enabled inefficiencies and abuses. In principle, new regulations purport to strengthen the governance and accountability of civil society, and to assert national sovereignty over the development process.

In practice, however, efforts to regulate civic space are often a heavy-handed mixture of stigmatisation and delegitimisation, selective application of rules and restrictions, and violence and impunity for violence against civic actors and groups, motivated by the concentration or consolidation of political power.

Civic space may be conceptualised not as closing or shrinking overall, but as changing, in terms of who participates and on what terms. The rapid growth of the digital public sphere has dramatically reshaped the civic space for all actors, while right wing, extremist, and neotraditionalist groups and urban protest movements have occupied demonstrably more of the civic space in the past decade. That civic space may be seen as changing rather than shrinking also fits with the observation that many civil society actors report being pushed or pulled into closer relationships with political elites or the state, in order to continue to operate.

While in many developing countries, civic and political rights have been exercised to support the realisation of basic human needs, some countries noted for their high growth and rapid human development appear to have achieved such gains without the benefits of generous civic space. At the same time, countries with well-established civil society institutions and formally democratic public space are frequently unable to overcome powerful opposition to distributive policies through open or democratic processes.

These paradoxes draw attention to the conditions under which civil society contributes to inclusive development

But how?

processes. These are present when actors have the capacity to represent the concerns of the marginalised and disempowered, with both the space to articulate those concerns independently, and the traction with political elites to elicit a policy response through meaningful engagement. It helps to understand civil society not only as groups advocating from beyond the boundaries of organised politics, but also as a site of contention, of constant struggle over the interests of state, society, and the market, spilling over at times into political and economic concerns. It is not only the independence of civil society, but the nature of its ‘fit’ with the state, that best explains the politics of inclusive development.

That efforts to restrict civic space seek to curb this contention, typically to clear a path for state or political projects or for business deals, is clear. Some of the most violent and sustained recent attacks on civil society actors have clustered around potentially lucrative land and natural resource deals, and around labour rights, particularly in export sectors; indigenous people’s and human rights groups, peasant and labour organisations have struggled against deals deemed harmful to society or the environment. An assertion of sovereignty and nationalist or traditional values tends to accompany and inform these moves, alongside concerted ideological efforts to discredit or delegitimise specific actors.’

The report then sets out 4 areas for further country-level research (the language is a bit IDS-ish, so I’ve added translations):

‘Closing civic space as struggles over national sovereignty in the development process’: this isn’t a uniform process – the way space closes depends on national politics. Let’s try and understand that connection better.

‘The rise of China as a development model’: is there some link with the closure of civic space, and if so, how does that link work?

‘Occupations and expansions of the civic space’: a lot of the new entrants are either nasty (eg some religious and nationalist movements) or more unruly/protest based than their predecessors. What are their agendas and developmental impact?

‘Closing civic space, dispossession and development’: how much of this is a smokescreen for land and natural resource grabs?

I would add a few more:

The different tactics and forms of leadership that have emerged in civil society in response to closing space – which ones have been most/least effective?

What have external actors like Western governments and INGOs done to try and help – when have they been successful/made matters worse?

More on the issue of aid dependence – should we make it a priority to help CSOs generate more resources domestically to reduce their vulnerability to the crackdown?

Has anyone done a kind of long term accompaniment of one or more CSOs, to see how they respond to shrinking space over time?

Please add your own ideas – and quickly, as we’ll be chewing over these issues today and tomorrow.

The post Here’s what we know about closing civic space – what other research would you suggest? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

September 16, 2018

Links I Liked

population. So large countries with a small population shrink in size – talking about you Canada, Mongolia, Australia, and Russia, and vice versa for heavily populated places like the Netherlands or Japan. Cool eh? And kind of obvious – has no-one done this before?

Groan

Compare and contrast: the Guardian’s Afua Hirsch on Theresa May’s visit to Africa. Hannah Ryder on last week’s China Africa summit – Deborah Brautigam combs through the aid numbers agreed there.

Cash Transfers for wonks: Techie but fascinating discussion of new paper by Chris Blattman and friends on the long term (9 yrs) effects of a group-based cash grant program for unemployed youth to start individual enterprises in skilled trades in Northern Uganda. And USAID has started a series of cash benchmarking evaluations that compare the per-dollar impact of USAID programs with that of a comparably sized cash transfer given directly to individuals or households.

The collapse of Lehman brothers 10 years ago had a silver lining for Kaori Shigiya, according to a piece in the FT

Our future is disappearing. Smart and moving ice statue protest – anyone know the location? While we’re on climate change, check out this amazing example of weather reporting-cum-CGI (it all kicks off about 30 seconds in)

Economic man v bunch of puppets rap battle, by Kate Raworth and friends

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers