Duncan Green's Blog, page 82

November 10, 2018

Audio summary of FP2P posts, week beginning 5th November, with some seasonally appropriate fireworks on aid and academia

The post Audio summary of FP2P posts, week beginning 5th November, with some seasonally appropriate fireworks on aid and academia appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 8, 2018

What did I learn from Wednesday’s arguments over aid, academia and ‘the literature’?

Including some great putdowns. My favourite, which made me laugh out loud, came from Ryan Briggs: ‘Just to be clear, you’re arguing that academics are insular and generalize too much from shoddy evidence, and the evidence for your claim is based on a conversation you had with a friend?’ Ouch.

So here’s what I take away from pondering 12 pages of comments and twitter traffic.

Firstly, it’s a marmite kind of post. Not surprisingly perhaps, most practitioners liked it, a lot of scholars hated it. But the most striking were the people in the middle – former practitioners now doing Masters, PhDs etc. Annette tweeted ‘Totally agree – just completed a 2nd MA in Dev Studies and constantly felt like my practitioner experience was at odds with ‘the literature’. Nigel Thornton talked of:

‘a gut wrenching frustration that meant I stopped doing a PhD a few years back. I had to be able to quote “the Literature” in order to justify my position in the “the Academy”, while at the same time knowing that the much of “the Literature” [came from] weaker academics who defaulted to citation bingo.’

Secondly, a number of people drew distinctions between disciplines – according to Ruth Carlitz political science, especially the US variant, has little time for conspiracy theories – it’s all empirical and positivist. Pauline Rose argued that work on education is more evidence-based and up to date; Lacey Wilmott ditto on health and social work. But two excellent contributions attempted to nuance my sweeping and unfair generalizations. First Justin Williams:

‘Of course there are many different camps in academia, and a few in the aid business too, but I still think that when I look at literature produced by development agencies and academics, it congregates around what you might call two ‘poles’. There is an ’empiricist’ or ‘positivist’ pole, which as Ruth Carlitz says tends to take the world as it finds it, and looks to solve problems through collecting data without much questioning of its own assumptions etc. At the other extreme there is a ‘critical’ pole which wants to question the assumptions which underpin development, but which (in my view) doesn’t back this up enough through detailed examination of empirical examples of what development projects actually do. There is some literature in the middle – my point is just that there should be a lot more.’

Which made me think about inner and outer circles of academics. In the middle are the real aid scholars, engaging with practice, distilling useful lessons etc. They found the post wrong and offensive, with good reason. Some of them are my friends, and I can only beg their indulgence. But outside them is a wider ring of development academics who do not focus primarily on aid, but often talk about it and are important in framing the views of their students – I think they are much more likely to generalize based on a couple of formative experiences and books from decades ago.

Pablo Yanguas’ unholy Trinity

Then Pablo Yanguas responded with a brilliant discussion on his blog. He argued that ‘academic work on development – ideally – has three symultaneous aspirations: methodological rigor, theoretical significance, and practical relevance. The Holy Trinity of devstud. The ESRC proposal trifecta.’ He then explored different combinations of the three, distinguishing between seven types of research. Really useful.

Third, of course we should read what great minds, and even not-so-great ones, have written about our subject. But who decides what is included/excluded in ‘The Literature’? Is it confined to peer reviewed academic articles, or should it include papers and internal documents from aid practitioners? And as Victoria Sanchez pointed out, it is almost never homogeneous:

‘My problem is with the way the literature is used as an excuse to back what half the literature says. If the literature really does coalesce around clear answers, then great. But it seldom, if ever, does.’

Tom, who self describes as a ‘young(ish) PhD’ with a foot in both camps, elaborated

‘I often struggle to have productive conversations with my more academic colleagues. This is because what they mean, or assume I understand by, ‘the literature’ can be quite different than what I do.

Yes, I’ve read the same critical development books from the 1980s and 1990s that they have. But that is about where the similarities stop. For me, the literature includes the reflective works put out by practitioners that have responded to / built upon those critical books, the current debates within powerful development donor organisations and online discussions like this one. This does not mean I have access to more ‘truth’. But perhaps it does mean that the problem lies with the size and scope of ‘the literature’, and with the differences between and amongst academics and practitioners?’

Fourth, Justin Williams was helpful on the role of ‘critical theory’ (a much bandied-about phrase in academia):

‘Critical theory has been brilliant at helping people to think about development in different ways, to stop us seeing  development only through the ‘common sense’ lenses of development agencies. But too often critical theory remains just a conceptual exercise. What was great about The Anti-Politics Machine and, more recently, the work of people like Tania Li, is the empirical detail they bring to support their arguments. When academic articles remain at the level of ‘critical rethinking’ there is no way any empirical data can challenge them… they are ‘unfalsifiable’.’

development only through the ‘common sense’ lenses of development agencies. But too often critical theory remains just a conceptual exercise. What was great about The Anti-Politics Machine and, more recently, the work of people like Tania Li, is the empirical detail they bring to support their arguments. When academic articles remain at the level of ‘critical rethinking’ there is no way any empirical data can challenge them… they are ‘unfalsifiable’.’

He then added a pretty explosive coda:

‘To make this even more topical given today is US election results day… I think there is a link between the success of critical theory in academia and the wider spreading of conspiracy theories in society.’ Discuss.

Finally, is there a role for ranting of this kind? Alice Evans preferred my more constructive previous posts on

I feel a blog coming on

building bridges between academia and practitioners (here and here), something I do firmly believe in, in case you were wondering. James Georgolakis wearily protested my tendency to ‘pit the grounded practitioners against the out of touch egg heads once again’.

I would argue that the rant is warranted by my justified frustration with that outer ring of academics, but also that there is something Hegelian about this – you need to generate some tension with an antithesis before everyone can come together and do the big hug synthesis thing. On a purely selfish level, I also learned a lot from these comments – would people have chipped in so much on a nice, consensual post?

Final word to Elizabeth McConnell: ‘Highlights the need for critical thinking to be truly that i.e. to encompass critical self-reflection and examination of the norms and contexts in which academic publishing operates, then add in a bit of humility!’ And that goes every bit as much for practitioners too, of course.

Thanks to everyone who commented, and sorry I couldn’t do you all justice, even in this too-long post. Do please go back and read the original comments if you have time.

The post What did I learn from Wednesday’s arguments over aid, academia and ‘the literature’? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 7, 2018

The Rise of Social Protection, the art of Paradigm Maintenance, and a disagreement with the World Bank

other bodies. Social Protection includes emergency relief, permanent mechanisms such as pensions and cash transfers, and ‘social insurance’ based on people’s personal contributions.

LSE boss Minouche Shafik set the scene really well:

‘The failure of safety nets is partly responsible for the rise of populism. Governments failed to cushion the downsides of globalization and integration and haven’t kept up with changing societies and economies. We need to rethink the welfare state.

Lots of developing countries are at their ‘Beveridge Moment’ – discussing what kind of welfare state they want to build, a holistic view to replace piecemeal progress on education, health etc. But the social contract is getting harder to build and maintain in more heterogeneous, globalized societies – Who’s in/out? Who owes whom? What about the obligations to future generations?

Some old questions also need to be revisited: Redistribution needs to be squarely back on the table; tax systems have become less and less progressive over time. Universal benefits have a real political and social logic that economists lost sight of, in their preference for means testing and efficiency. We need to revisit our worship of efficiency. The Us and Them culture thus created disengages the middle classes. And, to paraphrase Titmuss, services targeted to the poor often end up being poor quality services.’

Armando Barrientos gave a useful intro to the recent trends, based on the ‘social assistance explorer’ a new (and free) online 109 country database he has helped put together (take a look – it’s amazing). Social Assistance (non-emergency Social Protection) has been rising fast in low and middle income countries. From 2000-15, the number of recipients went up nine-fold. Expansion has been uneven across regions and type of assistance (see figs).

Armando Barrientos gave a useful intro to the recent trends, based on the ‘social assistance explorer’ a new (and free) online 109 country database he has helped put together (take a look – it’s amazing). Social Assistance (non-emergency Social Protection) has been rising fast in low and middle income countries. From 2000-15, the number of recipients went up nine-fold. Expansion has been uneven across regions and type of assistance (see figs).

Once we got into the detailed debate on the virtues of different kinds of protection, the arguments were so ‘inside baseball’ that they mainly went above my head/beyond my brain. At these moments, you can always revert to checking your emails, but if you can stop angsting about your inadequacies as a geek, there is usually interesting stuff to think about even in these kinds of discussions.

For example, at a more meta level, events like these can offer some fascinating into the way paradigms shift or stick in international development.

Paradigm shifts are usually unwelcome: I got very excited when the opening panel included speakers on climate change and gender, arguing that prevailing ‘technical’ approaches to social protection need to incorporate both if they are to remain relevant and useful. On Climate Change, the LSE’s Ian Gough went as far as saying ‘Endless growth is not compatible with a single planet. We have to move to post-growth’. Yup. In a seminar with the IMF.

change and gender, arguing that prevailing ‘technical’ approaches to social protection need to incorporate both if they are to remain relevant and useful. On Climate Change, the LSE’s Ian Gough went as far as saying ‘Endless growth is not compatible with a single planet. We have to move to post-growth’. Yup. In a seminar with the IMF.

But what happened next was sobering. No-one laughed, called for his excommunication, threw anything or shouted abuse. Instead, the tumbleweed rolled across – no-one mentioned it again, or referred back to it throughout the rest of the day. They just reverted back to the normal discussions on social protection, as the (presumably rising) waters simply swallowed up Ian’s faux pas.

Gender did a little better, not least because Jeni Klugman deliberately instrumentalized it – this was about improving the effectiveness of social protection, not overthrowing the Patriarchy (which I guess would have been the gender equivalent of calling for de-growth).

By contrast, once a paradigm is entrenched, evidence or doubt can be dismissed with the flimsiest of arguments. The World Bank’s Michal Rutkowski spoke on the implications of AI and robotics. He was a core member of the team that produced the recent World Development Report on the future of work, and he went full-on Dr Pangloss, arguing that concerns about the impact of new tech on jobs were unfounded because past periods of tech disruption were followed by the creation of new kinds of jobs and increased productivity. (i.e. the Luddites were wrong).

I’ve previously criticised the WDR on this, so thought I would raise it in Q&A

Q: On the impact of new tech on jobs, you are saying ‘the past is a good guide to the future’. But we know that is not always true. Suppose (as a thought experiment) that impact on jobs is actually serious and negative, what might a precautionary approach look like? Would you make any different recommendations for social protection in such a scenario?

The Future for Optimists

A: ‘People cannot not do things. People will invent new things we cannot imagine now. I like playing chess, and thought it impossible that a computer could beat a Grand Master. I was wrong in 97 – Deep Blue beat Kasparov. I thought chess playing would die out, but numbers have been growing faster since 97.’

Okaaaay, so it’s true that people will find ways to fill their days, but will that make them happy? In the event of the impending destruction of millions of jobs (eg anyone who drives for a living, low skill manufacturing, an increasing number of routine white collar jobs), hobbies like chess or playing soccer badly won’t provide income, or the status and sense of wellbeing many people attach to having a job.

As for what this might all mean for social protection, Michal didn’t answer, but David Piachaud was pretty categorical: ‘Social Protection can’t protect against being rendered useless.’

For more on the World Bank and paradigm maintenance, see this 2014 post.

And here’s a brilliant video summary (10m views and counting) of the case for the World Bank taking this issue more seriously (ht Irene Bucelli)

The post The Rise of Social Protection, the art of Paradigm Maintenance, and a disagreement with the World Bank appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 6, 2018

Evil Donors and ‘The Literature’: Is there a problem with the way academics write about aid?

colleagues (especially the political scientists and anthropologists) who appear convinced that aid is essentially evil – a neo-imperialist plot to defend the status quo.

Secondly the way people use the phrase ‘The Literature’, in a way no-one outside academia would – as in ‘What does the Literature say on this?’ or ‘There is no Literature on this topic’ (at which point academics start rubbing their hands with glee). I’ve even found myself saying it occasionally, and feeling very scholarly when I did so.

A recent exchange both got me to link the two observations and resolve never to use the phrase ‘The Literature’ ever again. It started when my LSE colleague Rajesh Venugopal sent over his new paper in World Development (ungated version here). According to the abstract:

‘Talk of failure is commonplace in development. Drawing on a wide range of primary and secondary texts to provide illustrative evidence, the paper explores how failure is constructed, and advances a three-fold typology of failures that vary in terms of their positionality, the critical variables they identify as responsible, their epistemological stance, and the importance they accord to politics.’

I must confess, I didn’t understand much of that, but I read it anyway (Rajesh is a friend) and was struck by the way the argument was constructed. I wrote to him:

‘You make a lot of assertions, but I don’t see much in the way of evidence. eg ‘contemporary representations of development failure play an important role in sustaining the idea of intervening to end it’. My own experience would suggest the opposite. No-one I’ve met in the aid biz thinks failure is the way to ensure continued funding – just look at the dollars the Gates Foundation is ploughing into proof of impact. Where do you guys dream up this stuff?!’

Rajesh replied: ‘You’re reading it a bit too literally as a rigorous critique of development. It’s more of a woolly discussion of why everyone in the world thinks development always fails and the tone of pessimism and negativity that we swim in, i.e. everyone from the Daily Mail to the angry activist anthropologists.’

Unconvinced, I replied: ‘Inside the echo chamber created by journal paywalls, and largely unnoticed by the grubby masses of practitioners who live outside those walls, scholars write pieces largely built on the musings of other scholars. Each piece may just be a ‘woolly discussion’ but over time they acquire weight, a bit like a series of Donald Trump ‘people are saying’ tweets.

Unconvinced, I replied: ‘Inside the echo chamber created by journal paywalls, and largely unnoticed by the grubby masses of practitioners who live outside those walls, scholars write pieces largely built on the musings of other scholars. Each piece may just be a ‘woolly discussion’ but over time they acquire weight, a bit like a series of Donald Trump ‘people are saying’ tweets.

Before you know it, they have become ‘A Literature’, which can be cited in support of arguments, without the need for additional evidence (see my rant about David Hulme and Nicola Banks’ largely evidence-free crit of NGOs).

Last night I was speaking to a bunch of post docs at the Institute for European Studies in Brussels, and had a similar experience – wasn’t it the case that the big Foundations’ main aim in life is to head off radical change by supporting reformists and token change? None of the students appeared to have talked to anyone from a Foundation or read their strategies but it was OK, they could cite ‘The Literature’…..

This approach very easily lends credibility to what are really unsubstantiated conspiracy theories, and incoming students then ingest them as fact from their lecturers (I remember once, after I gave a SOAS lecture, a very confused student came up and said ‘so you don’t actually want to keep people poor then?’).’

Rajesh replied: ‘I do agree with you that there is a real problem because ‘critical insight’ in development is always about  uncovering a dark conspiracy at work. In my tribe, you’re not doing your job unless you’re unmasking villains and showing the hidden hand of imperialism, neoliberalism, etc, at work. It’s somehow viewed as a capitulation if you say otherwise, or e.g. suggest that Gates may be doing some good.’

uncovering a dark conspiracy at work. In my tribe, you’re not doing your job unless you’re unmasking villains and showing the hidden hand of imperialism, neoliberalism, etc, at work. It’s somehow viewed as a capitulation if you say otherwise, or e.g. suggest that Gates may be doing some good.’

At which point, Rajesh suggested ‘cry havoc and let slip the blogs of war’, so here you are.

Don’t get me wrong, this is not an apologia – there are plenty of examples of bad aid, political interference etc etc. But it is striking that academics are often quite content to rehash experiences and books from decades ago (e.g. James Ferguson’s wonderful The Anti Politics Machine, 1994; something they saw in Uganda in the 1980s) and assume that nothing has changed in the interim. Where’s the rigour in that?

My conclusion? If academics want to be taken seriously, they need to provide evidence (preferably from this century) for their assertions. rather than simply citing other academics, or ‘The Literature’. And please give me a slap if you hear me using the phrase ‘The Literature’. I will also continue never to link to gated publications, if I can help it, because the journal echo chamber is partly responsible for all this.

The post Evil Donors and ‘The Literature’: Is there a problem with the way academics write about aid? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 5, 2018

Aid’s fragile state problem – why is it so hard to even think about?

FCAS are characterized by states that are either absent or predatory – in terms of development, governments and officials are as likely to be part of the problem as part of the solution.

But the aid sector, especially the official world of bilateral and multilateral organizations, traditionally relies on the state as the main channel for spending aid dollars to provide education, health or the rule of law. Its instincts are statist. Aid wallahs can’t seem to cope when that recipe doesn’t work, and when confronted with FCAS, it often suffers some kind of intellectual loss of nerve where it ends up ‘assuming a state’ when discussing the role of aid. With a functioning (if imaginary) state, suddenly we can have all those comforting aid discussions about how it should best spend money, build schools etc etc. Most odd.

I mentioned this phenomenon in my review of a recent LSE-hosted ‘Commission on Fragility and Growth’, but it cropped up again in a recent ODI report on ‘financing the end of extreme poverty’.

Before it defaults back to a fictitious state, the report crunches some useful numbers. It projects poverty numbers out to 2030 and looks at what might ensure that the world ‘gets to zero’. It uses IMF and World Bank estimates of what states can reasonably be expected to raise in tax revenues and costs how much states need to spend to provide universal education and healthcare and on social protection to get everyone above $1.90 a day.

Key findings:

The proportion of people living in extreme poverty across the world is projected to fall from the latest estimate of 11% to 5% in 2030 as a result of economic growth. This would see 400 million people lifted out of extreme poverty ($1.90 a day), but leave another 400 million still in extreme poverty in 2030.

Of these 400 million people, 85% will be in fragile states.

Low Income Countries (LICs) will have 54% of the global total of extremely poor people (some fragile states are actually middle income, hence the difference between the numbers).

Low Income Countries (LICs) will have 54% of the global total of extremely poor people (some fragile states are actually middle income, hence the difference between the numbers).

On average, LICs could only increase their revenues from 17% to 19% of gross domestic product. The rest is going to have to come from aid.

While additional tax revenue reduces their funding gaps, 48 of the poorest countries in the world still cannot afford to fully fund the three core social sectors needed to end extreme poverty even if they maximise their tax effort. They would still face an aggregate financing gap of $150 billion a year. Of these, there are 29 severely financially challenged countries (SFCCs) that cannot even afford half the costs.

The 48 under-resourced countries are predominantly low-income, least developed and fragile states. The concentration is even more pronounced in the 29 SFCCs: all bar one of the 29 is a LIC or a least developed country (LDC), and only three are not fragile states.

This is where alarm bells began to ring: 26/29 of the SFCCS are fragile and/or conflict affected, and the answer is – more aid. To whom? To do what? Isn’t the politics of these places rather important in determining how much of the aid ends up reducing poverty?

I’m a big fan of the ODI so sent this draft post over to Marcus Manuel, who wrote the report. He pushed back with two good points:

‘First I agree I don’t talk about how to spend the money and that is really important. But I think there are wide range of instruments that have been used and could be used. Failing all else, Social Protection could be done entirely by the UN and CSOs – i.e. we treat this as a humanitarian emergency. And you do see external money well spent in FCAS – the Afghanistan reconstruction trust fund, Liberia pooled health fund and Yemen social development fund to name but three. I agree these countries face deep governance problems – but there are hybrid ways of ensuring money for basic services is delivered and benefits the poorest.

Second the aim of my paper was to sound the alarm – yet again – that donors are switching their money away from LICS/LDCS (low income and least developed countries) to countries that serve their national interest. Do critique me but please don’t let the donors off the hook. We can discuss and debate how best to spend the money but without the money we will all be unable to help.’

This is really useful and links nicely back to the work I’m doing on Public Authority at the LSE – trying to understand how power and politics actually works in precisely these countries that ODI labels as ‘SFCCs’. So what I’d be interested in reading is anything on how effective aid spending in FCAS differs from aid spending elsewhere – bypassing the state is one option, as Marcus says, but what else have people seen to work?

And here’s Marcus presenting the report

The post Aid’s fragile state problem – why is it so hard to even think about? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 4, 2018

Links I Liked

we talk and think about impending environmental Armageddon

I just installed Unpaywall. Fab extension to Chrome that finds you the ungated version of any academic paper. Open Access rocks.

I’ve also got a proper podcast channel now, check out the latest interview with Yuen Yuen Ang and tell your podcast-y friends.

Nudge unit/behavioural economics hype curve update: a new survey found that of the 111 identified OECD government policy nudges, a good chunk weren’t behavioural at all, at least half did not work as intended, and only 18 percent were put into practice. ht Chris Blattman

Trevor Noah with some great stand-up riffs on the nonsensical Caravan story

An ex-CIA undercover agent with the memorable name of Amaryllis Fox on what she learned – ‘everyone thinks they’re the good guy’. And an Al Qaeda prisoner quoting Hollywood at US interrogators – ‘you are the Empire, we are Luke and Han’. ht Jo Rowlands

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 3, 2018

Audio summary (9m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 29th October. Now downloadable from Soundcloud!

The post Audio summary (9m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 29th October. Now downloadable from Soundcloud! appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Podcast: How China Escaped the Poverty Trap, with Yuen Yuen Ang

Finally managed to persuade Yuen Yuen Ang, author of one of my favourite books from last year (reviewed here and discussion of bicultural authors like Yuen Yuen here), to come to LSE, where she gave a barnstorming lecture on the book and its wider implications. The previous evening I managed to catch up with her for an FP2P podcast. See what you think. I’m new to the podcast game, so any feedback/advice very welcome!

The post Podcast: How China Escaped the Poverty Trap, with Yuen Yuen Ang appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 2, 2018

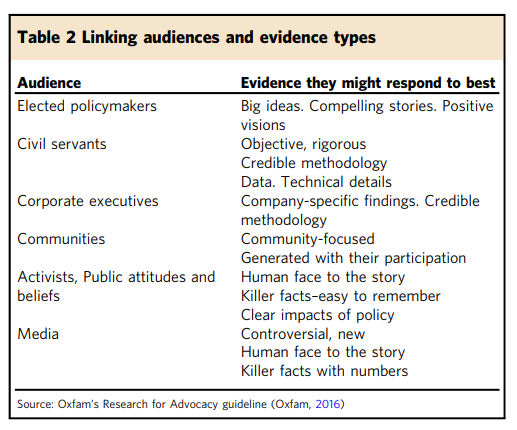

Using evidence to influence policy: Oxfam’s experience

Oxfam has got a new paper out on how it uses evidence to influence policy. My colleague Ruth Mayne led on it (along with other Oxfam colleagues, I

Yeah, right….

chipped in a few ideas). The paper brought together lots of new (to me) examples to illustrate how Oxfam seeks influence through research, while Ruth and Paul Cairney added some useful academic viewpoints on the research → policy process. I recommend it. Here’s the basic story:

‘Policymaking is rarely ‘evidence-based’. Rather, policy can only be strongly evidence-informed if its advocates act effectively. Policy theories suggest that they can do so by learning the rules of political systems, and by forming relationships and networks with key actors to build up enough knowledge of their environment and trust from their audience. This knowledge allows them to craft effective influencing strategies, such as to tell a persuasive and timely story about an urgent policy problem and its most feasible solution.

Empirical case studies help explain when, how, and why such strategies work in context. If analysed carefully, they can provide transferable lessons for researchers and advocates that are seeking to inform or influence policymaking. Oxfam Great Britain has become an experienced and effective advocate of evidence-informed policy change, offering lessons for building effective action. In this article, we combine insights from policy studies with specific case studies of Oxfam campaigns to describe four ways to promote the uptake of research evidence in policy:

(1) learn how policymaking works,

(2) design evidence to maximise its influence on specific audiences,

(3) design and use additional influencing strategies such as insider persuasion or outsider pressure, and adapt the presentation of evidence and influencing strategies to the changing context, and

(4) embrace trial and error. The supply of evidence is one important but insufficient part of this story.’

There’s a handy table on adapting narratives and research to the policy target.

There’s a handy table on adapting narratives and research to the policy target.

And here’s the conclusion:

‘The use of evidence for policy influencing has many ingredients: a robust evidence base, framing and persuasion, simple storytelling, building coalitions, learning the rules of the game in many different systems, the use of complementary influencing strategies, and a process of continuous reflection and change in light of experience and context.

Practical experiences, such as Oxfam’s, show that effective policy influencing requires a wide understanding of the role of research evidence. This message can be gleaned from a summary of the many steps from evidence to impact, as follows.

Take a value and evidence based stance to identify the need for change in policy and policymaking.

Identify the actors with the power to change policy, and the actors able to influence policymakers.

Understand which strategies help produce most change, focusing on specific institutions and wider contextual trends.

Identify people affected by the research and your target audiences, and work with them throughout relevant stages of research planning and production.

Learn how to frame your evidence and provide it to your audience at the right time, using powerful visuals and well-known messengers.

Test and adapt insider, outsider and other influencing strategies in light of experience, using trial and error across political systems and over time.

Stay agile, engage with policymakers readily and continuously, respond quickly to events, test and learn from your strategies, and be prepared to trade-off accurate but ineffective versus simplified and effective messages.

In other words, by showing the scale of this task, we show that evidence alone will not come close to making the difference.’

But I still recommend you read the full paper – it’s only 16 pages – Open Access, natch.

The post Using evidence to influence policy: Oxfam’s experience appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 1, 2018

What is civil society for? Reflection from one of Tanzania’s leading CSO thinkers

reflections from Aidan Eyakuze, Executive Director of Twaweza.

Who needs civil society organizations (CSOs)? If government does its job well, responding to citizens’ needs, delivering good quality services, safe communities and a booming economy, then what is the purpose of the diverse range of NGOs, trade unions, religious groups, community groups and others that make up civil society?

I was one of more than 600 people at CSO Week 2018 in Dodoma (Tanzania’s capital). We were there to both celebrate and debate the role of civil society in Tanzania. Lots of speakers from within and outside government spoke with almost universal praise for the role civil society plays. But not far below the collegial surface lurked a significant divergence of views.

The most important was conflicting views on the primary purpose of civil society. Government officials acknowledged the positive role of CSOs, but with a strong whiff of ambiguity about their value and scepticism about their integrity.

Government ministers and senior officials revealed a clear preference for CSOs focused on uncontroversial service delivery activities (providing healthcare or education or clean water), over those working on raising citizen voices and advocating for better policies. They said that CSOs that focus on service delivery are supporting the government as the people’s legitimately elected representative. They are giving people the help they need, and can attract additional aid dollars into  the country for development. However, those CSOs that monitor and critique government, advocate for civic space and promote human rights, may in fact be pursuing foreign agendas or wasting resources by working in areas that do not resonate with citizens’ needs, such as public services and livelihoods.

the country for development. However, those CSOs that monitor and critique government, advocate for civic space and promote human rights, may in fact be pursuing foreign agendas or wasting resources by working in areas that do not resonate with citizens’ needs, such as public services and livelihoods.

I also heard many CSOs worrying that limiting their activities to providing services makes them little more than handmaids to government and reduces citizens to mere subjects. Championing the causes of social justice, equality, shared responsibility and rewards has them working to ensure people are free citizens.

But this is a simplistic, though long-standing distinction, and I think it misses the point. For the ‘uncontroversial’ services to be delivered well to those needing them most, civic space must, crucially and contentiously, be open.

Without freedom of information and expression, people will not know what they are entitled to. Nor will they be able to voice their opinion on the quality of services or bring other problems to the attention of decision makers. Without freedom of assembly and association, the gap between a distant and powerful government and an atomised population becomes almost unbridgeable. Without citizen participation, services rarely meet citizen needs and citizens feel  increasingly powerless and disconnected. Without inclusion, marginalised people are left even further behind. Without human rights and the rule of law, citizens have little protection from corrupt or bullying officials. Those who no longer trust that the game is fair stop trying to play and withdraw to the fringes.

increasingly powerless and disconnected. Without inclusion, marginalised people are left even further behind. Without human rights and the rule of law, citizens have little protection from corrupt or bullying officials. Those who no longer trust that the game is fair stop trying to play and withdraw to the fringes.

CSOs that work to protect and promote open civic space are also working to strengthen public services and improve people’s lives. We may be doing so indirectly, but our contribution is just as valuable and necessary.

I would go further to argue that even delivering services is a political undertaking. When people are healthier, better educated and have access to water, shelter and can make a decent living, they are more likely to ask for more and expect better. And delivering services has an impact on local power relations. A new well, for example, increases the availability of water for some, changes time allocation, especially for women, and alters patterns of ownership, income and social interaction in a village. Choices are inherently political.

So the question is not ‘are we for services or for social justice?’ The two are inseparable.

Bishop Stephen Munga, of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Tanzania (ELCT) and Chancellor at  Sebastian Kolowa Memorial University expressed this point powerfully last week when he argued that “civil society gives rise to government itself.” “It is civil society that legitimately says whether government is good or bad, laws are good or bad. It is not for government or those in power to assess itself!”

Sebastian Kolowa Memorial University expressed this point powerfully last week when he argued that “civil society gives rise to government itself.” “It is civil society that legitimately says whether government is good or bad, laws are good or bad. It is not for government or those in power to assess itself!”

His assertions were both attractive, and unsettling. Who assesses us CSOs? I confess to leaving Dodoma with a nagging feeling that, as CSOs, we did not engage in some important self-reflection. Are we well-placed to deliver a vision of a healthy, wealthy, wise and just Tanzania? Are we trusted by those who we claim to represent and speak for? Are we legitimate in their eyes? How much are citizens engaged in our work, in shaping our priorities and activities, or are we distant, disconnected and self-righteous? And how much are we really contributing to improving social justice overall? Could we do more?

These questions warrant really good answers. Such deep self-reflection can only be healthy for the sector, and for the wider community which we serve. We should not shy away from it.

It should come as no surprise that government and civil society have different views on what the sector should look like, or on the relationship between services and rights. It is only proper that a combination of tension and collaboration should exist, as one party seeks to maintain social order and the other to promote social justice. A society without such tension would slide into decline and decay.

So what is civil society for? It is to improve public services and people’s livelihoods. It is also to raise citizen voices and protect civic space. And it is even, on occasion, for disagreeing with government. I am sure that doing these things makes us all stronger. We will all be better off as a result.

More wise words from Aidan here

The post What is civil society for? Reflection from one of Tanzania’s leading CSO thinkers appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers