Duncan Green's Blog, page 78

January 7, 2019

Who Are the Worldâs Poor? New overview from CGD

Guest post from Gisela Robles and Andy Sumner

Guest post from Gisela Robles and Andy Sumner

It sounds like a simple question: Who are the worldâs poor? Farmers, right? Well, yes, but not only. In a new CGD working paper, Gisela Robles and I take a closer look at the data on global poverty to answer this question in finer detail. We find that when poverty is measured over multiple dimensionsâincluding education, health, and standards of livingâidentifying the global poor reveals some important findings.

Measuring poverty

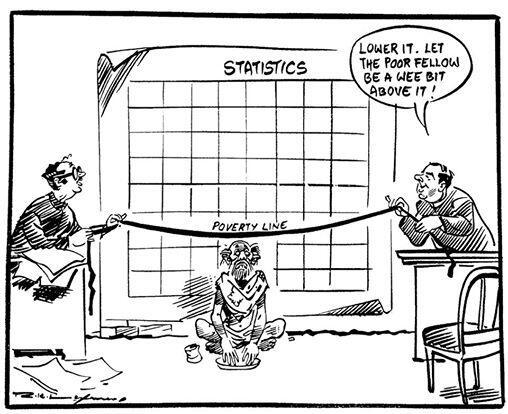

The World Bankâs new global poverty line is $1.90 per day. Using this measure, there were an estimated 766 million people living in âextreme povertyâ in 2013. Castañeda et al. (journal version and ungated) find those living under $1.90 a day are primarily rural, young, and working in agriculture.

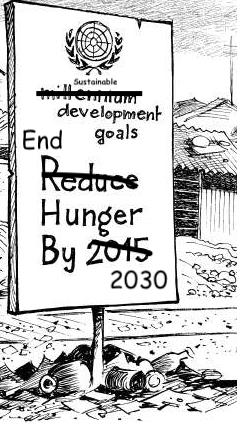

But if what if we consider dimensions of poverty beyond monetary measurements by looking at things like poor schooling, ill health, and malnutrition? Does the global poverty profile change? Put another way – with the UN global goals to end poverty in mind – what needs ending and for whom by 2030?

In our paper, we present a new global poverty profile using the multidimensional poverty measure developed by Sabina Alkire and James Foster at the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. We estimate a new global poverty profile for multidimensional poverty in 2015 based on 106 countries that account for 92 percent of the developing worldâs population.

Here are our three main findings:

The worldâs poor are young, often children but not necessarily farmers

First, at an aggregate level, the overall characteristics of global multidimensional poverty are more or less similar to those of global monetary poverty at $1.90 per day. In both cases, poor households tend to be rural households formed predominantly by young people.

Half of the worldâs multidimensional poor are under 18 years of age. Yes, you read that right. And three-quarters are under 40 years old.

We find, in countries which have the data, that two-thirds of poor households have a member employed in agriculture, but surprisinglyâgiven incomes are likely to be higher outside agricultureâone-third of poor households have no member employed in agriculture.

In other words, it turns out at least in the countries that we have data for that a significant proportion of the worldâs poor arenât farmers.

And a thought for those who say global poverty effects only 1 in 10 of the worldâs population: among the most frequent poverty deprivations, we find that undernutrition affects 1.5 billion peopleâdouble the $1.90 global poverty headcount.

Rural poverty is more about infrastructure. Urban poverty is more about child mortality and food

Second, at a disaggregated level, we find that poverty in rural areas tends to be characterized by overlapping deprivations in education and

access to decent infrastructure, meaning water, sanitation, electricity, and decent housing.

In contrastâand counterintuitively given the proximity, in principle, to better healthcare and economic opportunitiesâit is child mortality and malnutrition that is more frequently observed within urban poverty.

Just how multidimensional poverty is depends on where you live

Finally, the extent of the multidimensionality of poverty differs substantially by region; moreover, some deprivations frequently overlap while others do not.

The infrastructure-related dimensions of povertyâwater, sanitation, electricity, and housingâoften overlap with each other. No surprise thereâit is easy to imagine that people who live without access to clean water, for example, might also lack access to sanitation.

What is surprising is that deprivations in health indicators overlap least frequently with other dimensions of poverty. This points towards the importance of giving health poverty direct attention in policy.

Why does it all matter?

So where do the numbers take us? Â If many of the worldâs poor are outside of agriculture, and the urban poor experience malnutrition and child mortality despite better economic opportunities in principle, then what is going on?

First, the good news: most of the worldâs multidimensional poor live in countries with good growth history. In fact, three-quarters of global multidimensional poverty is in fast-growing countries (see table below).

So, no need to worry as growth will take care of poverty in due course? Youâd think growth was always good for the poor, right?

Well, in a very general way, yesâbut with some big caveats. In terms of monetary poverty, in up to one-third of growth episodes monetary poverty rates may not fall, as highlighted in a new book edited by Ravi Kanbur, Paul Shaffer, and Richard Sandbrook. And it seems the link between economic growth and multidimensional poverty is weaker still, as Santos et al. find (journal version and ungated).

Part of the story may be the different kinds of growth episodes. One interesting new theory is that of UNU-WIDERâs Kunal Sen (journal version and ungated), who separates types of growth episodes into âgrowth accelerationâ and âgrowth maintenanceâ and finds that the former is much less likely to benefit the poor than the latter. He argues that this is because the institutional factors that lead to growth accelerations are different from those that lead to growth maintenance.

What that study, the new book, and our own findings point towards is that itâs a good time given the global goals on ending poverty to take a much closer look at when growth goes right and wrong for the poor, and why.

Where do the multidimensionally-poor live? The global distribution of multidimensional poverty by growth history of country, 2015.

GDP per capita, PPP

(constant 2011 international $), average annual growth, 1990â2016

Number of countries

% of global

multidimensional poverty

25

13.4%

1% – 2% per capita/year

22

11.1%

>2% per capita/year

59

74.8%

No data

5

0.7%

Total

111

100.0%

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 2018 for GDP per capita growth rates and population figures; Robles and Sumner (2018) for MPI data. Note: Includes 111 low- and middle-income countries with populations above 1 million people.

The post Who Are the Worldâs Poor? New overview from CGD appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

January 6, 2019

2018 FP2P report back: stats; most-read posts and some big plans for 2019

Hi everyone, Happy New Year and all that. Thought I’d kick off with the usual feedback post on last year’s blog stats:

According to Google Analytics, overall reader stats for 2018 were:

328,887 ‘unique visitors’ – not quite the same as ‘different readers’ – if you read the blog on your PC, laptop and mobile, that counts as 3 people. Within the year, the usual trend – a weekly cycle of low weekend reads, and summer and Christmas lulls (see graph). Those numbers are pretty much identical to previous years, which I’m happy with as there were several glitches this year – Google Analytics went down mid-year, and then the email notifications to 5,000 or so subscribers stopped going out for three months, which shows up clearly in the stats – no email reminder and the world forgets all about you. Tragic.

January was a busy month – the two spikes you can see are for the post on Oxfam’s annual Davos report on 22nd, and Alice Evans’ great ‘sausagefest’ post on 11th (see below).

Most-read Posts: these continue to surprise me – only three of the top 10 were new – who says blogging is ephemeral? Apart from a possible bias towards aid industry related topics, I can see very little pattern behind this list – could someone please tell me why a 2009 post on climate change in South Africa is top with 19,000 hits in 2018?

How is climate change affecting South Africa? (a 2009 post – the oldest in the list).

10 top thinkers on Development, summarized in 700 words by Stefan Dercon (2018)

The Perils of Male Bias: Alice Evans replies to yesterday’s ‘Sausagefest’(2018)

Development Studies is fun, but is there a job at the end of it? (2018)

Venezuela: Latin America’s inequality success story [a story from 2010, dug up by some right wingers to have a go at Oxfam]

Religion and Development: what are the links? Why should we care? (from 2011)

How does emigration affect countries-of-origin? Paul Collier kicks off a debate on migration (2014 post, presumably Brexit-related)

How to get a PhD in a year and still do the day job (from 2011)

$15bn is spent every year on training, with disappointing results. Why the aid industry needs to rethink ‘capacity building’. (2017)

Are women really 70% of the world’s poor? How do we know? (2010)

Where were the readers from? As usual, US and UK dominate, but then it gets more interesting, with South Africa, India and the Philippines breaking up the Northern stranglehold.

If all goes to plan, next year’s annual report should look very different. After 10 years, 2,500 posts, 12,500 comments and 2.4 million readers, it’s time to change things up. We’re currently recruiting for someone to help us decolonise the blog, (applications closed, sorry) by sourcing top quality written, audio and video content from the Global South. Watch this space. But I’ll still be banging on about stuff too – it’s too much fun to stop!

The post 2018 FP2P report back: stats; most-read posts and some big plans for 2019 appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 21, 2018

Audio summary (8m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 17th December

And that’s me done for 2018 – see you next year!

The post Audio summary (8m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 17th December appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 20, 2018

Links I Liked, Christmas Edition

A few seasonal links before I head off for a Christmas break. See you in 2019, when we’ll find out if the only way is up….

Africa’s must-read books of 2018

Some global governance has been going on, despite everything: Briefings on the new global migration pact and the Katowice climate change agreement.

Pratham: The Grameen Bank of Education in the Developing World. Nancy Birdsall’s rave review of a huge and innovative education NGO

Complex self-organizing system in action: a murmuration of starlings in a Spanish dawn, Christmas Day

State of the World’s Humanitarian System in 9 charts. Good, accessible overview

The untold story of how India’s sex workers prevented an Aids epidemic

Population mountains: amazing data visualization that shows city population in 3D as a series of blocks: The taller the block, the more people ht Alice Evans

And congrats to my friend Kate Raworth for coming in at number 2 of the top 10 TED talks of 2018. Absolute showstopper.

The post Links I Liked, Christmas Edition appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 19, 2018

Book Review: New Power: How itâs Changing the 21st Century and Why you need to Know

As befits a grumpy old technophobe, I have long been sceptical of the hype around online activism. Iâve cited Malcolm Gladwellâs bah humbug piece on the Arab Spring âwhy the revolution will not be tweetedâ as pretty much summing up my views.

But after reading New Power, by Henry Timms and Jeremy Heimans, Iâm going to have to change my views. The authors are leading digital gurus â Timms came up with âGiving Tuesdayâ, Heimans founded GetUp! and now runs Purpose. Between them, they have a vast pool of stories of both success and failure to draw on. And backstories â theyâve done their research on everything from Kony2012 to Boaty McBoatface.

First of all, definitions (or something approximating them â this is not an academic book):

âOld Power works like a currency. It is held by a few. It is closed, inaccessible and leader-driven. It downloads and it captures. New Power operates differently, like a current. It is made by many. It uploads, and it distributes. The goal with new power is not to hoard it, but to channel it.â

New Power is reflected in both models (crowd-sourced, open access, very different from the âconsume and complyâ Old Power variety or the âparticipation farmsâ of Uber and Facebook) and values (informal, collaborative, transparent, do it yourself, participatory but with short-term affiliations).

It is built on what the authors see as âan increasing thirst to participateâ¦.. a huge wave of joining, affiliation and participationâ especially among millennials âformerly known as the audienceâ. Social media has allowed the lift-off of broad social movements like #MeToo or

Well we can always dream

#BlackLivesMatter, new business models like Airbnb and Uber, but also ISIS and the NRA, which have both proved adept at combining old and new power. And some spectacular failures, as when Starbucks boss Howard Schultz decided his baristas would build a ârace togetherâ movement by discussing racism as they served up flat whites.

One of the more striking case studies of failure is the story of the Boaty McBoatface debacle (if you havenât heard of it, check it out â itâs hilarious). Not just because it shows how things can go wrong if you encourage participation without actually meaning it, but also because the authors imagine what could have happened if the organizers hadnât pulled the plug:

âHad it leaned into all that engagement, and proudly smashed the champagne bottle on the hull of Boaty McBoatface, it could have built a community that delivered for the Natural Environment Research Council for years. You might imagine a generation of Brits following Boatyâs adventures by GPS; schoolkids greeting Boaty when she docked in their town. Boaty might have become the most participatory vessel in the world, capable of delighting the public, but also of providing a portal for more substantial engagement with the scientific enquiry she pursued.â

Although the authors are clearly more into new power than old, there is a nuanced discussion of the links between them. Organizations

like the NRA strike a different balance of the two at different moments, brilliantly out-manoeuvring gun control advocates. Getting that combination right avoids the âfate of fizzleâ suffered by Occupy and other movements that failed to vary their repertoire (see my rubbish phone pic for their decision tree on this).

Another perversion of new power values is the rise of âplatform strongmen, mastering new power techniques to achieve authoritarian endsâ. They see Donald Trump as one such, who ârevels in the instability of countless truths.â

New Power acknowledges the as yet unfinished battle between the countervailing tendencies of the online world: the tendency to centralization v the possibility of digital cooperation, as when the city of Austin, Texas replaced Uber with a locally run cooperative equivalent (why arenât more city governments doing that? Heads up, Sadiq Khan!)

But they also celebrate leaders who have combined both the techniques and the values of New Power, such as Al-jen Poo of the US National Domestic Workersâ Alliance, Lady Gaga and her âlittle monstersâ or Beth Comstock of General Electric.

To generate a series of recommendations and recipes, the authors rely on use numerous case: the ice bucket challenge (new power) vanquished the telethon (old power) because it got the right combination of ACE: something that was Actionable, Connected people together and that was Extensible â it could be customised by the participant.

A particularly useful insight comes in their â5 steps to build a crowdâ, where they stress the importance of âsuperconnectorsâ â a relatively small set of highly engaged participants who can be a massive resource. Legoâs flagging fortunes turned around largely because new management recognized the importance of the AFOLs â Adult Fans Of Lego who had previously been seen as a bit of a joke. Who are Oxfam (or LSE)âs superconnectors and how do we talk to them?

As I read, I found myself regularly scribbling notes to self in the margin â could Oxfam do this? How could we enable a community of

people whoâve taken the Make Change Happen MOOC to stay in touch and do stuff? Should Oxfam encourage people to play with its logo (informally known as âThe Kennyâ after South Park), as Airbnb has? Could there have been an online response to the Haiti scandal earlier this year, learning how to âembrace the stormâ like the US Girl Guides on transgender members?

people whoâve taken the Make Change Happen MOOC to stay in touch and do stuff? Should Oxfam encourage people to play with its logo (informally known as âThe Kennyâ after South Park), as Airbnb has? Could there have been an online response to the Haiti scandal earlier this year, learning how to âembrace the stormâ like the US Girl Guides on transgender members?

Any criticisms? I found myself hankering for a tighter âso whatâ section â it gets a bit hand-waving in its final call to arms. Here is the world they want to see:

âPeople need to feel more like owners of their own destinies, rather than pawns of elites. If the only meaningful expression of all this pent-up agency is the occasional election or referendum, people will naturally be inclined to use their participation as a way to lash out. Platform strongmen and extremists will offer easy answers. But we need something different: a world where our participation is deep, constant and multi-layered.â

A bit vague perhaps, but a highly stimulating book, recommended for technophobes and technophiles alike.

And here’s their New Power 2×2 of players against models and values

The post Book Review: New Power: How itâs Changing the 21st Century and Why you need to Know appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Book Review: New Power: How it’s Changing the 21st Century and Why you need to Know

As befits a grumpy old technophobe, I have long been sceptical of the hype around online activism. I’ve cited Malcolm Gladwell’s bah humbug piece on the Arab Spring ‘why the revolution will not be tweeted’ as pretty much summing up my views.

But after reading New Power, by Henry Timms and Jeremy Heimans, I’m going to have to change my views. The authors are leading digital gurus – Timms came up with ‘Giving Tuesday’, Heimans founded GetUp! and now runs Purpose. Between them, they have a vast pool of stories of both success and failure to draw on. And backstories – they’ve done their research on everything from Kony2012 to Boaty McBoatface.

First of all, definitions (or something approximating them – this is not an academic book):

‘Old Power works like a currency. It is held by a few. It is closed, inaccessible and leader-driven. It downloads and it captures. New Power operates differently, like a current. It is made by many. It uploads, and it distributes. The goal with new power is not to hoard it, but to channel it.’

New Power is reflected in both models (crowd-sourced, open access, very different from the ‘consume and comply’ Old Power variety or the ‘participation farms’ of Uber and Facebook) and values (informal, collaborative, transparent, do it yourself, participatory but with short-term affiliations).

It is built on what the authors see as ‘an increasing thirst to participate….. a huge wave of joining, affiliation and participation’ especially among millennials ‘formerly known as the audience’. Social media has allowed the lift-off of broad social movements like #MeToo or

Well we can always dream

#BlackLivesMatter, new business models like Airbnb and Uber, but also ISIS and the NRA, which have both proved adept at combining old and new power. And some spectacular failures, as when Starbucks boss Howard Schultz decided his baristas would build a ‘race together’ movement by discussing racism as they served up flat whites.

One of the more striking case studies of failure is the story of the Boaty McBoatface debacle (if you haven’t heard of it, check it out – it’s hilarious). Not just because it shows how things can go wrong if you encourage participation without actually meaning it, but also because the authors imagine what could have happened if the organizers hadn’t pulled the plug:

‘Had it leaned into all that engagement, and proudly smashed the champagne bottle on the hull of Boaty McBoatface, it could have built a community that delivered for the Natural Environment Research Council for years. You might imagine a generation of Brits following Boaty’s adventures by GPS; schoolkids greeting Boaty when she docked in their town. Boaty might have become the most participatory vessel in the world, capable of delighting the public, but also of providing a portal for more substantial engagement with the scientific enquiry she pursued.’

Although the authors are clearly more into new power than old, there is a nuanced discussion of the links between them. Organizations

like the NRA strike a different balance of the two at different moments, brilliantly out-manoeuvring gun control advocates. Getting that combination right avoids the ‘fate of fizzle’ suffered by Occupy and other movements that failed to vary their repertoire (see my rubbish phone pic for their decision tree on this).

Another perversion of new power values is the rise of ‘platform strongmen, mastering new power techniques to achieve authoritarian ends’. They see Donald Trump as one such, who ‘revels in the instability of countless truths.’

New Power acknowledges the as yet unfinished battle between the countervailing tendencies of the online world: the tendency to centralization v the possibility of digital cooperation, as when the city of Austin, Texas replaced Uber with a locally run cooperative equivalent (why aren’t more city governments doing that? Heads up, Sadiq Khan!)

But they also celebrate leaders who have combined both the techniques and the values of New Power, such as Al-jen Poo of the US National Domestic Workers’ Alliance, Lady Gaga and her ‘little monsters’ or Beth Comstock of General Electric.

To generate a series of recommendations and recipes, the authors rely on use numerous case: the ice bucket challenge (new power) vanquished the telethon (old power) because it got the right combination of ACE: something that was Actionable, Connected people together and that was Extensible – it could be customised by the participant.

A particularly useful insight comes in their ‘5 steps to build a crowd’, where they stress the importance of ‘superconnectors’ – a relatively small set of highly engaged participants who can be a massive resource. Lego’s flagging fortunes turned around largely because new management recognized the importance of the AFOLs – Adult Fans Of Lego who had previously been seen as a bit of a joke. Who are Oxfam (or LSE)’s superconnectors and how do we talk to them?

As I read, I found myself regularly scribbling notes to self in the margin – could Oxfam do this? How could we enable a community of

people who’ve taken the Make Change Happen MOOC to stay in touch and do stuff? Should Oxfam encourage people to play with its logo (informally known as ‘The Kenny’ after South Park), as Airbnb has? Could there have been an online response to the Haiti scandal earlier this year, learning how to ‘embrace the storm’ like the US Girl Guides on transgender members?

people who’ve taken the Make Change Happen MOOC to stay in touch and do stuff? Should Oxfam encourage people to play with its logo (informally known as ‘The Kenny’ after South Park), as Airbnb has? Could there have been an online response to the Haiti scandal earlier this year, learning how to ‘embrace the storm’ like the US Girl Guides on transgender members?

Any criticisms? I found myself hankering for a tighter ‘so what’ section – it gets a bit hand-waving in its final call to arms. Here is the world they want to see:

‘People need to feel more like owners of their own destinies, rather than pawns of elites. If the only meaningful expression of all this pent-up agency is the occasional election or referendum, people will naturally be inclined to use their participation as a way to lash out. Platform strongmen and extremists will offer easy answers. But we need something different: a world where our participation is deep, constant and multi-layered.’

A bit vague perhaps, but a highly stimulating book, recommended for technophobes and technophiles alike.

And here’s their New Power 2×2 of players against models and values

The post Book Review: New Power: How it’s Changing the 21st Century and Why you need to Know appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 18, 2018

What do Witch Doctors actually do? I interviewed one to find out â their job description may surprise you

One of the things that any Acholi person wants to avoid is to be associated with a witch doctor, but I took courage and informed the bodaboda (motorbike taxi) man that I was heading to the witch doctorâs place. He bombarded me with questions: what is your problem? Are you looking for riches? Has someone bewitched you? And his last word was that these people (witch doctors) are bad.

People certainly associate witch doctors with bad acts. They donât associate witch doctors with, for example, deciding whether Widows, with or without children, can stay on the land of their dead husbands, return to their maiden home or have the choice to reject or accept a protector (male relative of their late husband)?

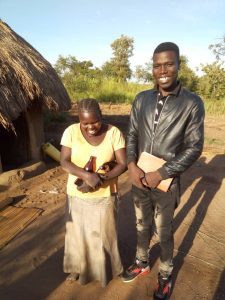

Yet thatâs just one of the roles I discovered when I interviewed some witch doctors in Northern Uganda as part of my research for CPAID. Letâs hear from Akumu Christen (a female witch doctor):

âIt was in 2009 when I became a witch doctor, even though I never wanted to be one. In 2005 I was attacked by a âjokâ for the first timeâ.

Robin: âShe was trying to show me what she uses in her daily work, Each one of those things has got different roles to play. The spear represents a god call Jok Kalawinya. Kalawinya is summoned when someone is possessed by evil spirits. The Bible represents a god called Mary, Mary is a white and she loves peace, so for anything concerning bringing peace, they summon her. The beer bottle represents a god call Jok Kirikitiny. Kirikitiny is a god from the Karomonjong ethnic groups – he is concerned with protection. The small syrup bottles contain a liquid substance which she takes before starting her work, it makes her see and hear from the gods.â

A jok is a class of spirit within the traditional Acholi belief system that is viewed as the cause of illness. Traditional healers (known as ajwaka) first identify the Jok in question and then make an appropriate sacrifice and ceremony to counter them. Alternatively if such an approach is unsuccessful the person possessed by the jok can go through a series of rituals to gain some level of control over the jok and then themselves become ajwaka.

âThis jok wanted me to become a witch doctor. When I resisted, I became mad for three months, but in the fourth month I was taken from the forest and became a born-again Christian and the jok left me alone But that liberty only lasted for two years and then I suffered the hardest attack yet from the jok. I became mad for the second time and lived in trees like a monkey for three months without eating food or drinking water and without coming down to the ground. Then my sister brought another witch doctor to initiate me into being a witch doctor, which was what the jok wanted all along, and thatâs how I became a witch doctor.

I was scared because of what people would say but I now have realised that this jokâknown as jokajula- does not support wrong-doing like killing people. I donât do rituals to kill people but to help themâ.

Akumu Christen now helps the people in her neighbourhood town. Paico, in different ways, including:

Mental Health Worker: Helping victims or Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) returnees by trying to stop or prevent spirits from attacking them. Or stop them from being haunted or  rerunning in their minds the bad things that they did in the bush, preventing nightmares and helping them cope in their community.

Peace Maker: Participating in the reconciliation of two clans, where one killed a person from the other clan. Beside that she is also involved in summoning the spirit of the dead to ask him who should receive the âkwo moneyâ(blood money paid to the victimâs family/clan).

Family Therapist: End barrenness in both men and women, which is hugely important because children are very significant to an Acholi:Â for a home to be call a home it should have children around.

Repair broken marriages or relationships.

Livelihoods Promotion: Remove bad luck and make people rich, especially those who have been put into bondage by bad people who  want them to remain poor

want them to remain poor

Disaster Prevention: She is summoned by the community elders to perform rituals to prevent natural calamities like drought or floods.

These are some of the things she does, but she is also a mother of two children with a very loving husband.

So now let me ask you again, do you still think witch doctors are bad people?

The post What do Witch Doctors actually do? I interviewed one to find out â their job description may surprise you appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

What do Witch Doctors actually do? I interviewed one to find out – their job description may surprise you

One of the things that any Acholi person wants to avoid is to be associated with a witch doctor, but I took courage and informed the bodaboda (motorbike taxi) man that I was heading to the witch doctor’s place. He bombarded me with questions: what is your problem? Are you looking for riches? Has someone bewitched you? And his last word was that these people (witch doctors) are bad.

People certainly associate witch doctors with bad acts. They don’t associate witch doctors with, for example, deciding whether Widows, with or without children, can stay on the land of their dead husbands, return to their maiden home or have the choice to reject or accept a protector (male relative of their late husband)?

Yet that’s just one of the roles I discovered when I interviewed some witch doctors in Northern Uganda as part of my research for CPAID. Let’s hear from Akumu Christen (a female witch doctor):

‘It was in 2009 when I became a witch doctor, even though I never wanted to be one. In 2005 I was attacked by a ‘jok’ for the first time’.

Robin: ‘She was trying to show me what she uses in her daily work, Each one of those things has got different roles to play. The spear represents a god call Jok Kalawinya. Kalawinya is summoned when someone is possessed by evil spirits. The Bible represents a god called Mary, Mary is a white and she loves peace, so for anything concerning bringing peace, they summon her. The beer bottle represents a god call Jok Kirikitiny. Kirikitiny is a god from the Karomonjong ethnic groups – he is concerned with protection. The small syrup bottles contain a liquid substance which she takes before starting her work, it makes her see and hear from the gods.’

A jok is a class of spirit within the traditional Acholi belief system that is viewed as the cause of illness. Traditional healers (known as ajwaka) first identify the Jok in question and then make an appropriate sacrifice and ceremony to counter them. Alternatively if such an approach is unsuccessful the person possessed by the jok can go through a series of rituals to gain some level of control over the jok and then themselves become ajwaka.

‘This jok wanted me to become a witch doctor. When I resisted, I became mad for three months, but in the fourth month I was taken from the forest and became a born-again Christian and the jok left me alone But that liberty only lasted for two years and then I suffered the hardest attack yet from the jok. I became mad for the second time and lived in trees like a monkey for three months without eating food or drinking water and without coming down to the ground. Then my sister brought another witch doctor to initiate me into being a witch doctor, which was what the jok wanted all along, and that’s how I became a witch doctor.

I was scared because of what people would say but I now have realised that this jok–known as jokajula- does not support wrong-doing like killing people. I don’t do rituals to kill people but to help them’.

Akumu Christen now helps the people in her neighbourhood town. Paico, in different ways, including:

Mental Health Worker: Helping victims or Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) returnees by trying to stop or prevent spirits from attacking them. Or stop them from being haunted or rerunning in their minds the bad things that they did in the bush, preventing nightmares and helping them cope in their community.

Peace Maker: Participating in the reconciliation of two clans, where one killed a person from the other clan. Beside that she is also involved in summoning the spirit of the dead to ask him who should receive the ‘kwo money’(blood money paid to the victim’s family/clan).

Family Therapist: End barrenness in both men and women, which is hugely important because children are very significant to an Acholi: for a home to be call a home it should have children around.

Repair broken marriages or relationships.

Livelihoods Promotion: Remove bad luck and make people rich, especially those who have been put into bondage by bad people who  want them to remain poor

want them to remain poor

Disaster Prevention: She is summoned by the community elders to perform rituals to prevent natural calamities like drought or floods.

These are some of the things she does, but she is also a mother of two children with a very loving husband.

So now let me ask you again, do you still think witch doctors are bad people?

The post What do Witch Doctors actually do? I interviewed one to find out – their job description may surprise you appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 17, 2018

Why do stable Political Party systems suddenly collapse? Some intriguing insights from Bolivia: Podcast (20m) and blogpost

A new paper by my LSE colleague Jean-Paul Faguet caught my eye, not least because of the timing. It’s a reflection on the causes of the

Jean Paul Faguet under a Bolivian rock

rapid collapse of previously stable political party systems, based on the experience of Bolivia. Impressive timing – we met and recorded this podcast just as Theresa May and Emmanual Macron were facing their respective political meltdowns. And for non-podcast listeners (podpeople?), here’s a fairly drastic edit of Jean-Paul’s essay (so blame me for any clunky bits).

Across Europe, the UK and the US, the decline of mainstream political parties, and the resurgence of populism, have been evident for some years now. As the phenomenon grows, it becomes clearer and clearer that this is not limited to certain charismatic leaders, like Geert Wilders in Holland, or particular policy issues, like immigration. Something far bigger and deeper is at work. Witness the collapse of all of Italy’s major political parties, which governed the nation throughout the post-war period. The rapid decline of France’s center-right and Socialist parties is another example. The current upheaval on both sides of American politics is a third.

Throughout the West, not just particular parties but entire party systems are losing their relevance. By ‘party systems’ I mean parties arranged in a competitive equilibrium along a left-right, worker-capitalist ideological axis. Having dominated the 20th century, and presided over enormous social and economic change, these systems are suddenly disintegrating around us. Well-prepared, experienced leaders are unable to mobilize traditional coalitions of voters. This allows established parties – even entire countries – to fall into the hands of charismatics and extremists. What’s causing the collapse? Is it somehow tied to deeper changes in society? What’s likely to come next?

To quote both Niels Bohr and Yogi Berra: predicting is hard, especially when it concerns the future. But as I argue in an article just published in the Journal of Democracy, we can open an analytical window into the future by examining the experience of Bolivia. Bolivia? I can hear you think. Yes, Bolivia. Precisely because it’s one of the poorest countries in the western hemisphere, Bolivia’s politics were never as institutionalized, nor its parties as strong, as those of richer, more developed countries. But it has suffered many of the same economic shocks, technological disruptions, and social and environmental changes as far more developed countries. Which is why the disintegration of its political system began earlier, and proceeded faster, than elsewhere. Adjusting heavily for context, Bolivia offers useful insights into how political disintegration works, and clues about where it may be going.

Political Stability

During the second half of the 20th century, Bolivia’s political party system was a surprisingly robust component of a famously fragile democracy. Why, early in the 21st century, did it suddenly collapse, to be replaced by the gigantic figure of Evo Morales and his comparatively loose Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS)?

During the second half of the 20th century, Bolivia’s political party system was a surprisingly robust component of a famously fragile democracy. Why, early in the 21st century, did it suddenly collapse, to be replaced by the gigantic figure of Evo Morales and his comparatively loose Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS)?

Although Bolivia suffered many coups in its first 190 years of independence, from 1953 onwards its politics was characterized by a party system arrayed roughly along a left-right, labor/peasant-vs.-business/capital axis typical of the twentieth century, which was remarkably stable. So dominant was this system that the same parties – indeed the same individuals – survived coups, civil disturbances, guerrilla insurgency, hyperinflation and economic meltdown, and striking social change – returning again and again to take up the reins of power. Why did it suddenly, unexpectedly collapse in 2003?

Bolivia’s radical decentralization in 1994 provided the trigger by which a cultural cleavage could become political. Before 1994, Bolivia was a highly centralized country where politics was legally and financially restricted to the national level. By creating hundreds of new municipalities, decentralization generated hundreds of spaces of local politics that had not previously existed. In these new spaces, Bolivia’s indigenous and mestizo majority could at last become political actors in their own right. The irrelevance of the dominant system revealed itself to them not analytically, but in the practical sense of responding to constituents’ demands to win elections. Over the course of a decade, these new actors abandoned first the ideological discourse of the elite party system, and then the parties themselves.

The dam broke in 2002, with a surge of parties emerging all over the country. A handful of parties tightly controlled from the top by

A different kind of politician

privileged, urban elites gave way to 388 parties, most of them new, tiny and with ultra-local concerns, constituted and run by unprivileged, ordinary Bolivians: carpenters, truck drivers, shopkeepers, and many, many farmers. Politics didn’t so much fracture as disintegrate from the bottom up. For a short time there was unbridled party multiplication. But then order began to emerge as many micro-parties federated, and others were absorbed, into the umbrella-like structure of the MAS.

Four Lessons for the West

Political party systems, even those that appear successful and stable, can and do fall apart once they lose their moorings in the key issues and conflicts voters care about most. What is essential is the link between parties and social cleavage. Where it is missing, parties are doomed.

The nature of these cleavages evolves. The old worker-capitalist divide on which politics in the West has been based for a century or more appears increasingly obsolete. As manufacturing and heavy industry decline, they take with them a class of workers who strongly identify with each other against a common adversary.

Bolivia illustrates how hard parties find it to change their core values and positions, because they have invested so much in building reputations based on them. For different but complementary reasons, both politicians and activists oppose large shifts. Hence as society changes – even as a result of policies they implemented – parties tend to get left behind.

When established parties fail, in which underlying social cleavage will a new kind of politics anchor itself? Such a cleavage would need to be not only relevant, but competitively compelling to a large segment of the population. ‘Competitively compelling’ means attractive to voters, as political entrepreneurs create new movements and compete for adherents. Their narrative, which privileges one particular cleavage over others, must be more compelling than the narratives other parties base on alternative cleavages. And today the most compelling narratives in the West, as in Bolivia, revolve around race, ethnicity, and place.

In historical terms, this is an extraordinary reversal. The Western Enlightenment believed in the equality of mankind. Liberalism sought to overcome identity-based cleavages. In countries like the US and France, liberals built not just politics, but national identities based on shared ideals, and not skin color or cultural traditions. Parties arrayed on a left-vs-right axis were accessible to everyone, regardless of identity. For decades we have taken this as given. But it is useful to remember that an open, inclusive politics in a multi-ethnic democracy is a hard thing to pull off. The danger now for the West is that a new politics is forged around identitarian cleavages of race, religion,  ethnicity, and language. This would vindicate Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” thesis, and possibly mark the failure of the Liberal project.

ethnicity, and language. This would vindicate Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” thesis, and possibly mark the failure of the Liberal project.

Finally, why is political realignment around identity good for Bolivia, but likely bad for Europe and the US? The first answer is that we cannot yet tell if it will be good for Bolivia. The events following realignment have so far been positive because Bolivia entered the process in a deep, deep hole. It was a poor, highly unequal society, in which a coherent, historically dispossessed majority continued to be politically excluded and economically disadvantaged by a small minority. Overturning that required a kind of politics suited to the society’s principal cleavage – race, ethnicity, and language. The new politics produced a regime that proved surprisingly prudent on the macroeconomic front, and was stunningly lucky internationally, coinciding for most of its life with a natural-resource boom that swiftly lifted its boat. But tough times reveal the true character of any government. In Bolivia, this test is under way now.

The deeper answer is that the implications for the West are as different as these societies and their challenges are from Bolivia’s. The likelihood is not that the “wrong politics” is replaced with one that reflects the society better, as in Bolivia, but rather that a cleavage is created where currently only differences exist. The risk is that the politics of identity will take one of the many ways in which citizens in the West differ from one another and, through sharp, polarizing, and racist language, create a new, hard social cleavage that divides us.

The post Why do stable Political Party systems suddenly collapse? Some intriguing insights from Bolivia: Podcast (20m) and blogpost appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 16, 2018

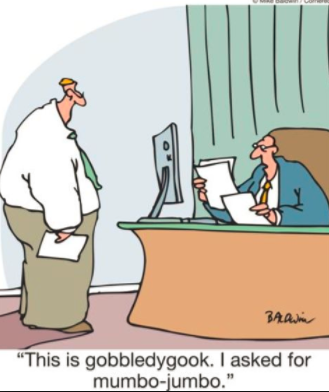

When to write in DevSpeak; when to use Plain Language? More handy tips.

multiple audiences simultaneously, which reminds me of Disney films’ amazing ability to combine a simple narrative to entertain the kids with enough irony and knowing references to keep the adults amused.

Kate Murphy’s post Just to be clear: why Devspeak needs to adopt Plain Language rang many bells for me. Over the past five years I’ve given 115 writing workshops for NGOs, charities, UN agencies and other non-profit groups, mostly in the development sector in Europe and Africa.

When I’m not giving workshops, I’m editing for the same kinds of agencies, so I’ve seen close-up the kind of mayhem Devspeak can cause. Duncan’s earlier post Which awful Devspeak words would you most like to ban? brought back the horrors of my migration to Devspeak-land 10 years ago after 25 years in journalism.

I agree wholeheartedly with Kate’s diagnosis of the malaise and her recommended treatment. Much of what I teach in my workshops is based on plain language principles.

But I worry that in Kate’s and Duncan’s posts there is an either/or attitude to Devspeak – Devspeak bad, plain language good – that doesn’t match the reality many writers face.

Yes, Devspeak on its own is dire. But sometimes people have to use Devspeak words because certain readers are expecting to see them (or because they mean specific things for which there are no other words).

Yes, Devspeak on its own is dire. But sometimes people have to use Devspeak words because certain readers are expecting to see them (or because they mean specific things for which there are no other words).

The answer is that you can use both Devspeak and plain language – and you often should.

First time round, use the development term that will push the right buttons – for donors, experts, wonks, officials – and explain it in simpler language. After that, you can go on using either the Devspeak term or the paraphrase, depending on how your audience is made up.

That question of audience is crucial. I ask my workshop participants to consider which of their audiences – and how many people in each audience – understand their agency’s jargon. Few audiences, it turns out, are made up solely of specialist or non-specialists. In other words, we almost always need to write for both.

The readers with the most power to bring about change – policy-makers, decision-makers, donors, community leaders, even the media – are often non-specialists. So failing to explain your Devspeak to them can literally get you nowhere.

What consequences do you risk in the other direction – in spelling out for experts what they already know? Perhaps they’ll be bored, irritated or frustrated. But those are minor problems compared with the consequences of not tapping into the power of the change-makers.

Nevertheless, many Devspeak users are reluctant to spell out the meaning of the terms they use. Kate calls this “an inexplicable resistance to plain language writing”. When I ask my workshop participants why they use jargon, though, they also tell me why they steer clear of plain language, and the answers are revealing.

Writers fear that they won’t be taken seriously. They worry that they won’t seem expert, professional, qualified or sufficiently educated. They are apprehensive that won’t be regarded as part of the in-crowd.

Where do these fears come from? Many development experts (especially those in think tanks) write as if their audience is made up solely of academics or their peers, and they are concerned above all else to preserve a brittle, narrowly perceived scientific credibility. The irony  is that the best academic writing has moved on from the dense, stodgy manner that some Devspeak writers use, as Helen Sword describes in her terrific book Stylish Academic Writing.

is that the best academic writing has moved on from the dense, stodgy manner that some Devspeak writers use, as Helen Sword describes in her terrific book Stylish Academic Writing.

In general, there is a failure to imagine the audience. That leaves most Devspeakers writing principally for one another.

I think the sector needs not only to adopt plain language principles, as Kate says, but to recommit to writing for the least specialist reader as well as the specialist reader. And that means talking both languages, Devspeak and plain language, when necessary. It can be complicated (you could write a book about it, and I am). But it’s a crucial step towards, yes, making change happen.

Spelling out what you mean takes more work, of course (as well as more words), but you need to do it so that the reader doesn’t have to do it. Where do you leave a reader who is baffled by a term you haven’t explained? They’ll probably Google it, and then you’re in deep trouble.

There are huge benefits to explaining Devspeak terms, in fact. You get to show what you and your organisation mean by a particular term, which is vital in the development sector where many terms are vague and/or used to mean different things by different people. (Try “educational attainment” on the next education wonk you meet. And then on the one after that.)

The first time I gave a workshop at the Overseas Development Institute, I asked the participants to write down definitions of some terms commonly used in international organisations. When we compared the results, uproar ensued. Civil society? Capacity building? Stakeholder? All were interpreted in vastly different ways by people who nevertheless worked for the same organization.

(Conclusion: Name the main groups you include in “civil society” and “stakeholders”. Say what “capacity building” entails in the context and say whose capacity to do what.)

A last thought about that resistance to plain language. In some development organisations, particularly in the UK, I’ve found that a deep distrust between research and communications teams seems to feed researchers’ reluctance to explain their terms (Devspeak is what I do, plain language is what you do). Breaking down that mistrust is crucial for many reasons, including the need for both sides to speak both languages so that we can reach both audiences, specialist and non-specialist.

The best comment I’ve heard on these questions came from Alexandros Lordos, research director of the Centre for Sustainable Peace and Democratic Development, in Cyprus. He came up to me after I’d given a workshop for his team in Nicosia in June. “I understand what you mean,” he said. “You mean that each of us needs to be our own communications officer.”

The post When to write in DevSpeak; when to use Plain Language? More handy tips. appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers