Duncan Green's Blog, page 79

December 14, 2018

Audio Summary (6m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 10th December

The post Audio Summary (6m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 10th December appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 13, 2018

Just to be clear: why Devspeak needs to adopt Plain Language

vent. Be my guest.

If the aid sector is to communicate more effectively, we must do more than tame the rampant devspeak that Duncan highlighted in his recent blog. Instead we should focus on presenting a clear and consistent message using plain language principles, which cover so much more than the individual words that we choose.

I’m the Plain Language Editor for Translators without Borders so devspeak is my constant companion. Much of my working day is spent deciphering terms and encouraging writers to use simpler alternatives. I’m aware of the chaos and confusion that devspeak can cause. But I think the bigger communication challenge facing our sector is a general lack of clarity and focus in our writing, and an inexplicable resistance to plain-language writing.

All aid workers should write in plain language

Whether we write for colleagues, government ministers, or refugees, plain language makes exchanging information a more efficient process. We operate in a multilingual environment that is full of linguistic tripwires and pitfalls. Native and non-native English writers of varying competencies communicate with native and non-native English readers of varying competencies. All of us face conflicting demands on our limited writing and reading time.

Ellie Kemp oversees TWB’s humanitarian work in Nigeria and in the Rohingya refugee response in Bangladesh. She believes that plain language is an overlooked factor in many humanitarian responses.

“Humanitarians can’t promote two-way engagement, empower affected people, or stimulate informed debate if we write in a convoluted way,” she says. “In Bangladesh, the response uses five languages; if the original English is unclear, the consequences are amplified across the other four.”

“Humanitarians can’t promote two-way engagement, empower affected people, or stimulate informed debate if we write in a convoluted way,” she says. “In Bangladesh, the response uses five languages; if the original English is unclear, the consequences are amplified across the other four.”

Earlier this year, TWB interviewed 52 humanitarian field workers responsible for surveying internally displaced people in north-east Nigeria. The findings highlight potential data quality issues stemming from a failure to use plain language. According to Ellie:

“We tested the field workers’ comprehension of 27 terms that they regularly use in survey questions and responses,” Ellie explains. “We identified misunderstandings and misinterpretations at every stage of the data collection process.”

Plain-language writing can help navigate our multilingual environment, yet native-English writers in particular are oblivious to the confusion we cause as we extrude our un-plain language onto the page.

So what are the characteristics of plain-language writing? Here are the ones that I think have the biggest impact on readability.

Define your peak message and state it early

Plain language requires writers to define the most critical aspect of their content and to communicate that consistently. Before I edit any content, I ask the writer to define the “peak message,” or the message that must stand out. In a move that makes me one of the most annoying people in our organisation I insist that the peak message is fewer than 20 words.

But to win back the affections of my colleagues, I apply the same rule to myself. So before I drafted this blog, I defined my 16-word peak  message as, “Plain-language writing is not only about avoiding devspeak; it’s about presenting a clear and consistent point.”

message as, “Plain-language writing is not only about avoiding devspeak; it’s about presenting a clear and consistent point.”

Create a logical structure and layout

The inverted pyramid model helps to arrange content logically and keep the reader focused on the peak message. It requires writers to arrange paragraphs in order of importance, and to arrange the sentences within them in order of importance too.

The next step in plain-language writing is to make the content physically clear. Four basic formatting principles that improve clarity are:

limit paragraphs to five sentences;

maintain an average sentence length of 15-20 words, and a maximum of 25;

use informative headings every four or five paragraphs; and

use graphics, but only if they make your message clearer.

Then worry about individual words.

Favour bold, direct verbs in the active voice

Verbs are powerful tools for clarifying your message. As with so many of life’s big choices, favour the strong, confident, single type. “It is recommended that writers give consideration to selecting verbs that might be more bold,” is only a slight exaggeration of the evasive verb structures that I regularly encounter. I’d change that to “Use bold verbs.”

And in choosing your bold verb, remember that passive voice is one of the last refuges of the uncertain writer. Consider the following passive voice construction:

“It is thought [by unnamed and unaccountable people] that the active voice should be used [by unnamed and unaccountable people].” This sentence provides little clarity for the reader. Compare it to “The Plain Language Editor wants writers in the humanitarian sector to use the active voice.”

Use the simplest tense

Some tenses require less cognitive processing than others. For non-native speakers the simple present and simple past tenses are typically the clearest. For example, “we write” or “we wrote.”

Some tenses require less cognitive processing than others. For non-native speakers the simple present and simple past tenses are typically the clearest. For example, “we write” or “we wrote.”

Continuous tenses (“we are writing” or “we were writing” or “we will be writing”) are less clear. So are future tenses (“we will write”, “we will have written”).

Use pronouns carefully

Pronouns can make a sentence ambiguous, so use them sparingly. “When communicating with refugees, humanitarians should provide information in their own language,” leaves the reader wondering whether to use the refugees’ or the humanitarians’ language. A confident English speaker might assume they know, but plain language relies on clarity, not assumptions.

Rethinking devspeak

From a plain-language perspective most devspeak is merely pretentious and annoying. Readers typically understand a sentence even if it contains an unexpected neologism. Few editors care if readers need to use a dictionary occasionally; most of us pretentiously and annoyingly believe that an extended vocabulary is a thing to aspire to. But confusion and ambiguity is not something to aspire to, so before you use devspeak, look for a simpler alternative.

You’ll probably find that if your peak message is solid, and the flow and format is logical, you won’t need devspeak after all. Clearly, it’s not essential.

You can stop reading here if you like, but I thought I’d add a worked example of how all this works….

A practical illustration

Here’s an example of applying plain-language principles to a donor report earlier this year.

The paragraph on the left is the original. What opportunities can you see for applying plain-language principles to that version? I saw several, so the author and I worked together to improve the original. We agreed to replace it with the paragraph on the right.

This short training course was designed to enhance [name removed] and other humanitarian organisation staff’s capacity to act as interpreters in the course of their work, often in the context of sensitization sessions, case management or household surveys. The content focused on the role of interpreting for humanitarian action, while also shedding light on broadly applicable modes and principles of interpreting. Learning methods combined exposition with interactive sessions, including group work and simple role play exercises that were not only meant to illustrate how to interpret effectively but also laid an emphasis on key ethical issues to be considered while interpreting. Topics covered included interpreting for children and vulnerable populations, and developing multilingual terminology for humanitarian interpreting.

(116 words)

Bilingual staff at [name removed] and other humanitarian organisations often interpret informally during sensitization sessions, case management activities or household surveys. We designed this course to help them interpret more effectively. The course covered:

● the role of humanitarian interpreting;

● broad interpreting principles;

● interpreting modes;

● interpreting for children and vulnerable populations; and

● developing multilingual glossaries.

Trainers combined instructional with interactive learning methods such as group work and role play exercises. The interactive exercises illustrated effective interpreting techniques and emphasised key ethical issues related to interpreting.

(83 words, or a reduction of 28 percent. Now imagine that reduction extrapolated across an entire report).

Here’s what I saw. From a plain-language perspective, there were several issues:

Long sentences (average 29 words, maximum 40 words).

Passive voice (“the course was designed”).

Uncommon words (“exposition”).

Complex terms (“multilingual terminology for humanitarian interpreting”).

Related ideas were separated in the text.

Did you get them all? Did I miss anything? Which version do you think is clearer? What techniques do you use to make your own writing as clear as possible? Let us know (in plain language, of course).

The post Just to be clear: why Devspeak needs to adopt Plain Language appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 12, 2018

Paul Polman on Capitalism, Leadership & Sustainability

office in Unilever House, its cavernous Thames-side HQ. Inside the art deco exterior, everything had been ripped out and modernised – all glass and walkways. We sipped mint tea as dusk sank over the London skyline and Paul talked non stop for 70 minutes, providing insights into the thinking of a global corporate mover and shaker:

On being CEO: I don’t short change Unilever, but how I use the rest of my time is up to me – perhaps half of my time [is for a wider advocacy role], but if I work 100 hour weeks, Unilever still gets more than it did from previous CEOs.

On Leadership: A leader is first and foremost a human being – there are many CEOs that don’t qualify in my opinion. There are two big issues – a chronic lack of leaders, and a chronic lack of trees. Leaders bring a morality, that it is not about yourself, and that is shown through respect for others. The faith in big men is misplaced. Rosa Parks was a true leader – she didn’t have a private jet.

Any leader makes decisions that have winners and losers, so by definition, we are in the business of pissing people off.

On Short Termism and Shareholder Capitalism: Short termism has crept into everything. We have become slaves to the financial markets – you can’t solve the world’s problems based on quarterly returns (QRs). Businesses were created to solve the problems of  society. Lord Lever created bar soap because Victorian Britain needed it, not because of QRs. We have to put long term sustainability as the true fiduciary duty of boards, but they have poisoned the well of fiduciary duty. It’s written in many laws, but not acted upon. We have to wean ourselves off that. Our shares went down 8% when we stopped quarterly reporting. I got a lot of pressure. But our share price has more than doubled over my 7 year period because we’ve delivered results.

society. Lord Lever created bar soap because Victorian Britain needed it, not because of QRs. We have to put long term sustainability as the true fiduciary duty of boards, but they have poisoned the well of fiduciary duty. It’s written in many laws, but not acted upon. We have to wean ourselves off that. Our shares went down 8% when we stopped quarterly reporting. I got a lot of pressure. But our share price has more than doubled over my 7 year period because we’ve delivered results.

The Case for Sustainability: Business is not there for the shareholders; it has to find longer-term solutions. If society doesn’t function we need to do business differently, a different form of capitalism. There are big issues coming up – climate change, inequality, unemployment, social cohesion. Governments are not responding and business is paying the price – economies are not growing.

Companies that operate in a more responsible way on Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) are more successful long term. If you publish more, take into account climate change or water scarcity, your plans are more robust, you publish more data, you reduce risks for investors. Then your cost of capital will be lower.

On Multi-Stakeholder Approaches: The job of a CEO has totally changed. You have to be systemic thinkers, able to work in partnership with national governments. I don’t want to work with just businesses any more. I was asked to chair a food security task force – they asked me to get a group of business people to write something for the Business 20. I said no, because if it’s just getting recommendations from business, they would have defended first generation biofuels, no-one would have thought about land rights, the whole issue of women would not have come in – that’s why I asked Oxfam, FAO, WFP, Greenpeace. Then I invited some companies. I would not do anything in Unilever without a multi-stakeholder approach. We have to work with government and civil society.

We need to create systems that are much more agile – you can predict maybe 1/10 things if you’re smart, but the other 9/10 something happens to which you need to react, new competitors, a natural disaster, a new law is passed – things that happen outside your control. And the world is getting more volatile everywhere. What you have to do as a company is that you have a quick feedback loop from the market that picks up these signals, and a structure that is very agile and externally focussed. So we have delayered and decentralized to the countries. It’s the supertanker to speedboat transition, while you are moving.

On Corporate Social Responsibility: What we did was not CSR, it was at the operating model. We moved from projects to an  integrated business model, and linked it to the success of the brands. Every brand has a strong purpose now – Domestos wants to build 25m toilets. That’s partly because the purpose means that we are much more connected (with the local context) – that’s always the challenge in a big company. If the environment changes we get a quicker signal. Many companies which are big are just obsessed with themselves. If your brand is toilet cleaner but you’re responsible for tackling open defecation, you start to think about your business quite differently from if your role is just to sell more toilet cleaner. When you are driven by not wanting anyone to go to bed hungry, you tackle food waste differently to when it’s just a cost savings programme.

integrated business model, and linked it to the success of the brands. Every brand has a strong purpose now – Domestos wants to build 25m toilets. That’s partly because the purpose means that we are much more connected (with the local context) – that’s always the challenge in a big company. If the environment changes we get a quicker signal. Many companies which are big are just obsessed with themselves. If your brand is toilet cleaner but you’re responsible for tackling open defecation, you start to think about your business quite differently from if your role is just to sell more toilet cleaner. When you are driven by not wanting anyone to go to bed hungry, you tackle food waste differently to when it’s just a cost savings programme.

On Climate Change and The Future: In the business community, there is much more advocacy on climate change – a whole new generation, thinking differently. The evidence and opportunities on climate change are overwhelming; the millennials want purpose driven businesses. There is real change happening. When there are abuses, we should go after them, but we should rejoice in the energy, even on climate change. The Paris Agreement is an amazing agreement – one of the most amazing that the world has done. How you make it come alive is the challenge, but it worked by focussing on the positive and embracing whatever came in.

The post Paul Polman on Capitalism, Leadership & Sustainability appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 11, 2018

How can the UN become a Thought Leader again?

(TDR) was one of the big annual milestones (along with the World Development Report, Human Development Report etc). They were essential reading for any policy wonk. They’re all still being published, but they make much less of a splash than they used to. Why is that and what can be done about it?

I made a nostalgic visit to the UN in Geneva last week to help the TDR team chew this over (about 20 people, Chatham House Rule, so no names/institutions, sorry). As prep, I went back to take a look at the most recent TDRs – they are beautifully written. Here’s a sample para from the latest one, on Power Platforms and the Free Trade Delusion:

‘The paradox of twenty-first century globalization is that – despite an endless stream of talk about its flexibility, efficiency and competitiveness – advanced and developing economies are becoming increasingly brittle, sluggish and fractured. As inequality continues to rise and indebtedness mounts, with financial chicanery back in the economic driving seat and political systems drained of trust, what could possibly go wrong?’

But that’s taken from a 27 page overview, with no accompanying blog, infographic or any of the other modern accoutrements. It’s like an elegantly crafted essay from a bygone era.

UNCTAD staff’s frustration is tangible: 2008 and the global financial crisis should have been a watershed moment for an organization critiquing the failings of ‘hyperglobalization’. But even though ‘all this stuff has been in the TDR since 1981, that’s not what people are talking about’. Instead of an attempt to build a more progressive international system, we are witnessing a polarization ‘between corporate cosmopolitanism and the nationalist backlash’. The good guys are left with the ‘anguish of having wasted a crisis’.

One focus for that anxiety is what is happening at the WTO. ‘The US has showed disdain for the WTO, sending junior officials, not participating, refusing to appoint new officials to the appellate body (the WTO’s court). In response, instead of criticising the US, there’s an idea that we have to appease it and by the way, we can slip in a few of our own things at the same time.’

The result is a trojan horse dressed up as a ‘modernization agenda’ that ditches many of the positive developmental features of the moribund Doha Round. In what feels like a return to the ‘rigged rules and double standards’ of the 1980s Uruguay Round, the US, EU and Japan are trying to end/severely curtail differentiation between rich and poor countries (‘special and differential treatment’ in WTO-speak). The only leeway the poor countries will get is a bit more time to implement the same things. Oh, and on agriculture, where it’s the rich countries that ‘distort trade’ with bucketloads of subsidies, the level of ambition has gone down.

The result is a trojan horse dressed up as a ‘modernization agenda’ that ditches many of the positive developmental features of the moribund Doha Round. In what feels like a return to the ‘rigged rules and double standards’ of the 1980s Uruguay Round, the US, EU and Japan are trying to end/severely curtail differentiation between rich and poor countries (‘special and differential treatment’ in WTO-speak). The only leeway the poor countries will get is a bit more time to implement the same things. Oh, and on agriculture, where it’s the rich countries that ‘distort trade’ with bucketloads of subsidies, the level of ambition has gone down.

So if the good guys are losing the narrative battle, what should they be doing differently?

One option is to ditch the big reports altogether – by sucking up scarce resources for diminishing returns, the milestones have become millstones. What big report ever brought a Trump, Bolsonaro, Putin or Duterte to power?

Failing that, options that could fit pretty well within the current arrangements include

a High Level Commission on the future of the multilateral system, perhaps drawing on the experience of CGD to ensure that its messages resonate beyond the UN system

ask Ha Joon Chang and others to mount a kind of ‘magnificent 7 rides again’ effort in the WTO to explain (again) why a return to the Uruguay Round is a really bad idea. Ha Joon is unsurpassed as a debunker of ‘fake history’ in development, exposing the epic levels of historical amnesia from the rich countries, which are now once again trying to ‘kick away the ladder’ of development from the poor ones.

Going further, UNCTAD could consider an entirely different way of working, abandoning the ‘old war strategy’ of annual battles based on the TDR, for a new tactic of continuous online guerrilla skirmishing, seizing moments of opportunity rather than working to a pre-agreed timetable of publications. That is so not the way the UN rolls, that it is going to have to find lots of allies to work with. The good news is that UNCTAD has a lot of friends out there in the wonk and policy-maker ecosystem.

Here are some of the ideas (in increasing degree of whackiness) for how an UNCTAD 2.0 can move from hierarchy to network:

Set up a ‘Friends of UNCTAD’ (FU!) network

Feed it with mythbusters, positive deviants, killer facts, infographics, blogs and summaries mined from current and past TDRs and

invite it to use/add to them in whatever way they find useful (advocacy, campaigns etc).

invite it to use/add to them in whatever way they find useful (advocacy, campaigns etc).Include a feedback mechanism so that the FU can both say what they need from UNCTAD and vote up/down the messages they find most useful. Then UNCTAD focuses on those on social media (including podcasts, videos etc)

More broadly, it could team up with market researchers and test its (many) different narratives on rethinking the global system with its key target audiences (governments, academics, activists) to find out which ones are most effective.

How about finding a partner to produce an UNCTAD data site that people can use and adapt (think Gapminder)?

Or an UNCTAD-hosted dating agency linking up activist and advocacy organizations with researchers and research (UNCTinder? Datadate?)

Any other suggestions?

The post How can the UN become a Thought Leader again? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 10, 2018

Is Meritocracy the new Aristocracy? And the 11 Tricks that Elites use to capture Politics.

Oxfam’s advocacy work on it). They’re great, and Max has opened his mailing list up to the anyone who’s interested – just email max.lawson@oxfam.org, with ‘subscribe’ in the subject line.

Here’s his latest effort, covering two issues: a reflection on meritocracy and a new analysis from Latin America of the 11 ways that elites use to capture politics.

‘When I was 19 on holiday from University, I worked nights in a factory. One of my fellow workers, Denzel, was 17 and he had recently been expelled from his school for violent behaviour. We had attended different schools, but they were both public schools with a mix of students from many different backgrounds. Even at that young age he had a string of convictions for various crimes. We became friends over that summer, and at one point he had got a new mobile phone (at that time very rare and expensive) and he called me over one night and asked me to read the instructions for him as he could not read.

This brilliant essay by Peter Adamson, who for many years’ wrote Unicef’s State of the World’s Children report, starts with a very similar story. His argument is a powerful and interesting one. What if meritocracy is simply another form of class oppression, and in some ways an even more dangerous one? It is an excellent, subtle yet powerfully argued paper, and I would really recommend reading the whole thing. He points out that the word meritocracy was originally conceived as negative. It was intended as a warning that the ‘re-stratification of society based on ‘intelligence + application = merit’ would produce a society of arrogant, insensitive winners, and angry desperate losers.

The philosopher john Rawls was very clear on this too: ‘meritocracy still permits the distribution of wealth and income to be determined by the natural distribution of abilities and talents. It is therefore arbitrary from a moral perspective’.

Basically, just because you are clever why should you have more money, more wealth and a better life, any more than someone who has inherited a fortune from their parents?

Basically, just because you are clever why should you have more money, more wealth and a better life, any more than someone who has inherited a fortune from their parents?

Firstly we know that a huge amount of what we call merit is based on our upbringing, our parents and our home background. Denzel had a troubled family background, I had supportive parents and a house full of books.

But secondly, we also know, although it remains contentious, that some intelligence is genetic. It remains contentious as it is used by defenders of inequality- people are rich because they are cleverer- that genetic differences in intelligence explain why certain people are in charge. But Adamson’s point is that even if this is true in some instances, it does not make it morally right.

He points out how in some societies, particularly rich ones, instead of the pyramid of income, there is a diamond, with some extremely rich people at the top, and then a large, relatively educated middle class. Underneath that are a large group of poor people, who become angry at the educated elites who are not interested in their lives and blame them for their own problems. I think many in France would recognise the power of this analysis in the face of the recent dramatic protests – the latest in the wave of popular anger erupting across the world. He worries that politicians in democracies can now rule with the support of those at the top and at the middle, and that this is powerfully legitimised by the notion of meritocracy.

It is also internalised by those at the bottom. At least with class or feudalism, the injustice of the system was very clear and based on obviously flimsy foundations like inherited wealth that did not stand up to scrutiny. With meritocracy, the poor are devalued because they are less clever and less able.

‘In summary, we should accept that high levels of intelligence and ability are needed to fulfil certain positions in society, but not that those who possess these abilities are more valuable as human beings. Ultimately this is the notion that must be dethroned- the idea that the attributes of intelligence and ability are the sum and measure of human worth. Instead we should revive the idea that all people are of equal value, and that a fair society is one that opens up the possibility of life-satisfaction, in all of its varieties, to all of its members’.

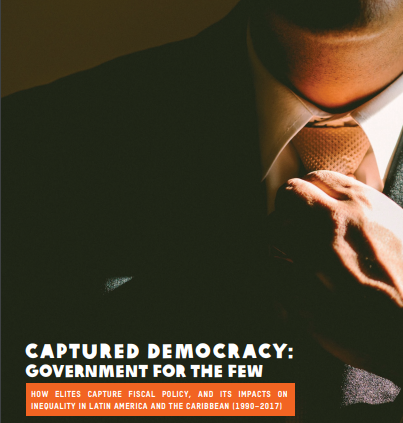

Analysing how elites have influenced policy in their favour in Latin America

This week our team in Latin America and the Caribbean published a great paper, which looks at 13 instances of pro-rich tax and spending policy and political action in the region and dissects the way in which the state has been ‘captured’ by elite interests.

They break down the process of state capture into 11 different methods deployed by elites, and then look at how many of the 13 cases employed these methods.

In almost all cases, a hugely biased and concentrated media was deployed to make the case for these policy changes, as was the revolving door where those from the private sector work in government. In the

Argentina case study, 40% of high-ranking officials in the treasury and finance ministry were former CEOs or managers in the private sector.

Most cases also involved a very rapid passage of legislation, using extraordinary extra-parliamentary powers, like executive orders. They also involved capturing the judicial process – in a quarter of cases business leaders successfully used constitutional courts to stop progressive tax measures.

In a third of cases, elites used what the paper calls a ‘technical smokescreen’, which I thought was a great concept. Deeply political and distributive tax changes are dressed up as boring and technical, so that no one notices. This is particularly possible with tax changes that reduce tax on the rich, as the impact on the poor is indirect.

Interestingly, outright bribes were only identified in two of the cases- but of course this is one of the hardest things to ascertain, so the actual number is probably higher. In one case the Brazilian firm Odebrecht, which used bribes to secure government contracts all over the continent even had a designated office for bribery and corruption operations included in its organogram.

Finally, public protest was identified in two cases, where large protests were mobilised in favour of tax changes that would only benefit a very rich elite, e.g. opposing inheritance taxes in Ecuador. This of course has echoes of the tea party in the United States. For me this final one tips over also into the capture of ideas rather than the capture of the state. The use of resources by elites to change the way people think is perhaps the most powerful tool at their disposal.

We all can see the undue power of elites in everyday life, but this level of analysis of methods and dissection of the levers of influence is rare, and very practical if we want to change things for the better. An excellent paper, and well worth reading.’

And here (if you can read it) are the 11 ways and 13 case studies. There’s also a background paper on the methodology.

The post Is Meritocracy the new Aristocracy? And the 11 Tricks that Elites use to capture Politics. appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 9, 2018

Links I Liked

southern authors etc. Details here (16th December deadline).

How Change Happens now available in Chinese

These motor cycle gangs are getting out of hand. Ht The Filling Station

Tom Baker risks another sausagefestgate with this male-dominated, but promising list of books for/about campaigners. I’d add Sarah Corbett’s How to be a Craftivist and Leslie Crutchfield (at least for the case studies), while Leila Billing recommended Rebecca Traister and Elaine Weiss,

Hey, that’s our stuff: Maasai v Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum

“Sounds Robotic” New CGD Podcast on tech and development

Why does inequality matter? Branko Milanovic summarizes the evidence: bad for growth of incomes of poor people and leads to political capture and the erosion of democracy.

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 7, 2018

Audio Summary (9m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 6 December

The post Audio Summary (9m) of FP2P posts, week beginning 6 December appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 6, 2018

How does Localization work on the ground? Podcast with Evans Onyiego and video of his work in Northern Kenya

On the margins of the localization discussion I covered yesterday, I grabbed a few minutes to interview Evans Onyiego. Evans runs a local Caritas office in Maralal, in Northern Kenya, where the Church is playing a big role in trying to rebuild trust between ethnic groups and communities whose traditional rivalries have been turbo-charged by the arrival of automatic weapons.

He’s particularly interesting both on the way his work highlights the role of faith organizations in such areas, and because he has a sharp, well-informed and practical bottom-up view of all the somewhat abstract conversations about reforming the humanitarian sector. Plus some great practical examples of building peace through boarding schools and shared market places, among others.

This is a multi-media experience: Here’s the podcast with Evans (18 minutes)

But you can also watch the 11m video about Caritas’ work in Maralal, which runs through the ‘entry points’ and ‘connectors’ they use to build trust and relationships. That includes working with women and children, inter-ethnic boarding schools and building trust by sharing market places.

And check out the slightly scary Mr Jackson Lodungikiok, politely described as ‘controversial’ – he later confessed to Evans that he had tried to kill him, but concluded that Evans must have some kind of divine protection, because he could never find him!

The post How does Localization work on the ground? Podcast with Evans Onyiego and video of his work in Northern Kenya appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 5, 2018

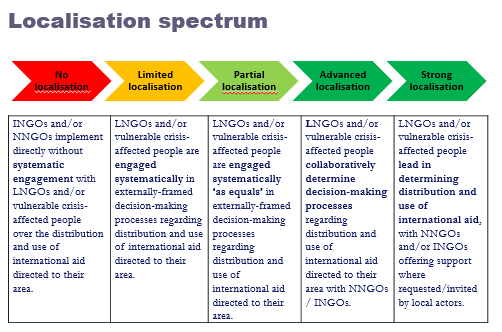

Localization in Aid – why isn’t it happening? What to do about it?

Spent two days this week discussing ‘Localization in Conflict Settings’. The subject is littered with aid jargon, but important – how does the humanitarian system ‘transfer power and resources’ to ‘local actors’ rather than outsiders insisting on running the whole thing (badly) themselves? It was organized by Saferworld and Save the Children Sweden to help flesh out a research programme, but it was under the Chatham House Rule, so that’s all I can tell you about who said what.

First, what is localization? Check out this handy spectrum from the organizers – it runs the whole way from token consultation to properly handing over the stick (and the dollars). The starting point for the discussion is failure: everyone in the aid system agrees that localization is a good idea, but it isn’t happening. According to the background paper:

handing over the stick (and the dollars). The starting point for the discussion is failure: everyone in the aid system agrees that localization is a good idea, but it isn’t happening. According to the background paper:

‘Of the US$16.4 billion of government funding for humanitarian assistance in 2016, 60% (US$12.3 billion) went to multilateral agencies, primarily the UN, and 20% (US$4.0 billion) went to NGOs. The NGO portion was divided between INGOs who received 85% and local and national NGOs who received 1.7% directly. In 2017, the local and national NGO portion increased to 2.7%.’

So first up we need a theory of non-change: why the inertia? A combination of ideas and institutions prevents progress:

Ideas:

‘Localization is risky’: it means relinquishing even the illusion of control in messy and dangerous places. That risk could be justified in terms of greater impact and long term strengthening of local organizations, but in practice, risk in aid seen not as something to be optimised, but just a bad thing, preferably kept to zero.

Aid Diversion: What if the bad guys somehow get hold of the money? The assumption is that local partners are more likely to divert the money than local INGO staff or governments. Really? Any evidence for that assumption (I tweeted a request for it, but got tumbleweed)? The falling level of tolerance of some degree of diversion as a ‘conflict tax’ – a way of getting resources to people in need – has made everything much harder. If donors really are demanding ‘zero tolerance’ of diversion in messy places like Syria or DRC, then they risk either making aid impossible, or creating a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ culture that could go horribly wrong at any moment.

From ‘Needs Assessment’ to ‘Strengths Assessment’: the humanitarian system sees the world as a series of deficits it has to plug: of infrastructure, food, basic goods, ‘capacity’. Yet the people on the ground, like Evans Onyiego, who I will feature tomorrow, start from a different place – what assets, capacity and skills do local people and organizations have (answer – lots)? How can we help them build on that? That switch suddenly makes localization look much more obviously a good idea, and suggests useful ways to achieve it. As a nice by-product, if you start with a people, community and strengths-focus, you inevitably have to confront and overcome the ‘silo problem’, whereby people experience their lives in holistic ways, rather than dividing them up into the weird and artificial categories preferred by aid (humanitarian, long term development, advocacy etc)

Institutions:

There are obvious institutional obstacles, like INGO bosses and fund raisers being judged by their turnover, but there are some less obvious ones too. Some INGOs are rebranding their local offices as independent organizations so that they can tap into localized funding pots. The really big conflicts like Syria generate comparably large amounts of aid: donors need to channel aid in huge chunks, that come with a massive bureaucracy of monitoring, evaluation and reporting (usually different for different donors). Local organizations are faced with either saying ‘no thanks’ and remaining subordinate players, or scaling up to become ‘mini-me’ big NGOs, with the risk that that diverts them from the kind of grassroots/ work that they actually want to do. And another comment that rang true from one INGO staffer: ‘we don’t want to devolve the power analysis etc to local partners because that’s the fun stuff!’

There are obvious institutional obstacles, like INGO bosses and fund raisers being judged by their turnover, but there are some less obvious ones too. Some INGOs are rebranding their local offices as independent organizations so that they can tap into localized funding pots. The really big conflicts like Syria generate comparably large amounts of aid: donors need to channel aid in huge chunks, that come with a massive bureaucracy of monitoring, evaluation and reporting (usually different for different donors). Local organizations are faced with either saying ‘no thanks’ and remaining subordinate players, or scaling up to become ‘mini-me’ big NGOs, with the risk that that diverts them from the kind of grassroots/ work that they actually want to do. And another comment that rang true from one INGO staffer: ‘we don’t want to devolve the power analysis etc to local partners because that’s the fun stuff!’

So Like St Augustine on chastity, the prayer becomes ‘Lord, let me localize, but not yet’.

But there is lots of good news too, including some really interesting things going on in an effort to break the logjam:

First, find out what local partners really want: they may not want to become miniature INGOs, but they do want help with improving security for their staff and partners; core funding so they can respond quickly to the chaotic events that characterize conflict settings; long term relationships that are maintained despite the frenetic pace of donor and INGO staff turnover and support for transition when the big money inevitably moves on (eg building their leadership and ability to raise local money).

Second some smart new ways of supporting them:

‘Microgrants’ of a couple of thousand dollars that can be quickly disbursed to crisis-affected people and self-help groups, with minimal bureaucracy. This is happening, but is held back by fears of diversion – it feels a bit like the cash transfer discussion from 10 years ago, and a similar combination of research and advocacy could help reduce opposition. Also worth linking up with the Community Driven Development debate, which covers much of the same ground.

National pooled funds: donors chip into a national fund that is designed and managed by local organizations, who could also tap into other local resources like religious giving (zakat).

Find some less bureaucratically constrained donors to pilot new approaches – Foundations? private companies?

Get every INGO and aid agency that is bidding for funds to include a localization budget line in their proposals, which is handed over to national pooled funds or other ways to support local organizations. It needs a convincing name – best we could come up with was ‘local value add’.

Finally, coming from outside the humanitarian bubble, I was struck that people in the room seemed unaware of the amount of common

The Other Kind

ground between discussions at this event, and those at, for example, the recent ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ confab. That suggests two easy wins:

Team up with those networks

Pull in some campaigners and advocacy people to design a proper influencing strategy on localization. We just did a quick stakeholder mapping/power analysis for the internal players in a large (but nameless) INGO and even that produced some new ideas for getting things moving.

Finally, if we need an anthem, can we get someone to tweak Peter Tosh? ‘Got to localize it, don’t criticize it’ ……

The post Localization in Aid – why isn’t it happening? What to do about it? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

December 4, 2018

Doing the Doughnut at the G20?

For the G20 and this week’s big climate change gabfest in Poland, Kate Raworth pulled together this smart piece on where the world’s countries have got to on living inside the doughnut, and where the burgeoning band of doughnut economists have got to in turning Kate’s big idea into a practical tool. It originally appeared on her Exploring Doughnut Economics blog:

This weekend the G20 are meeting in Argentina, with the aim (they say) of ‘building consensus for fair and sustainable development’. Since they collectively generate 85% of global GDP, whether they do or don’t transform their economies will profoundly affect us all. So how close to the Doughnut’s safe and just space are the G20?

Here’s one way of assessing it, using the pioneering national doughnut analysis by Dan O’Neill, Andrew Fanning, Julia Steinberger and Will Lamb at the University of Leeds. Using the best-available, internationally comparable data, they scaled the global concept of the Doughnut down to the national level for over 150 countries (only including those for which there were sufficient data – as a result, Saudi Arabia is unfortunately missing from this G20 analysis. The EU28 group is also not available for this analysis).

In essence, national doughnuts aim to reflect the extent to which a country is meeting its people’s essential needs while at the same time ensuring that its use of Earth’s resources remains within its share of the planet’s biophysical boundaries.

Since Argentina is hosting the talks, let’s take its national doughnut as an illustration. The aim is to fill the centre circle in blue, while not overshooting the green ring of the biophysical boundary. Like many countries worldwide, Argentina is both falling short on some social dimensions while already overshooting multiple biophysical boundaries.

The methodology for these national doughnuts is a work in progress, of course, but the indicators and data underlying them are improving year-on-year, and when taken as an overview of 150 countries, the initial analysis reveals some valuable 21st century insights.

The methodology for these national doughnuts is a work in progress, of course, but the indicators and data underlying them are improving year-on-year, and when taken as an overview of 150 countries, the initial analysis reveals some valuable 21st century insights.

In the chart below (made in collaboration with Andrew Fanning), humanity’s sweet spot – living in the Doughnut – lies in the top left-hand corner: a place where all social thresholds are met, without transgressing any biophysical boundaries.

So what does this 150 country overview reveal? Three insights jump out.

We are all developing countries now. The Doughnut challenge turns all countries – including every member of the G20 – into ‘developing countries’ because no country in the world can say that it is even close to meeting the needs of all of its people within the means of the planet. (If you are wondering which is that one country closer than the rest, it’s Viet Nam – but is it heading for the Doughnut, or moving straight past it?

New development pathways need new names. There are currently three broad clusters of countries making very different 21st century journeys, as labeled in the version of the diagram below:

A: Countries that are barely crossing any planetary boundaries, but are falling very far short on meeting people’s needs, including G20 members India and Indonesia. The development path that these nations must now pursue has never taken before. Copying the degenerative industrial path of today’s high-income countries (Group C), would most likely collapse Earth’s life-supporting systems.

B: Many middle-income, ‘emerging’ economies – including G20 members like Brazil, Russia, China, Argentina and South Africa – are both falling short on social needs while already crossing biophysical boundaries. These countries are now making future-defining investments in urbanization, energy systems and transport networks. Will these infrastructural investments take them further away from the doughnut, or start bringing them towards it?

C: Today’s high-income countries – including G20 members like the US, UK, France, Germany and the EU 28 itself – cannot be called developed, given that their resource consumption is greatly overshooting Earth’s boundaries and, in the process, undermining prospects for all other countries. These high-income nations, too, are on an unprecedented developmental journey: to sustain good living standards while moving back within Earth’s biophysical boundaries.

D: No country is yet in sweet-spot cluster D (for Doughnut!) – so how many years until some are there, and which will make it there first?

Given that the labels ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ no longer make sense in the 21st century context, how can we best rename these four clusters of countries? In comments on this blog, and on Twitter, please do share suggestions for inventive and memorable names for these very different country clusters facing the Doughnut challenge. Naming is framing, so let’s rename and reframe the future of development…

Transformative goals demand transformative approaches. Given that none of these three development paths have been pursued before – let alone have yet been achieved – it would be bizarre to think that last century’s economic theories, policy prescriptions and business models would equip us for what lies ahead. Getting into the Doughnut is our generational challenge and it demands transformational mindsets, models and action in economics, policymaking, and business.

As the world’s major economies, the G20 should be leading this transformation, with countries starting in all three country clusters. But since a key current criterion of G20 membership is having a large GDP, each country is geopolitically locked in to pursuing GDP growth to keep its place in the annual G20 Family Photo. So for leadership on the Doughnut Challenge, look, instead, to the Wellbeing Economy Governments, or #WeGO, an emerging grouping of countries – among them New Zealand, Scotland and Iceland – that are focusing on economic wellbeing and have a far greater chance of putting regenerative and distributive policies into practice.

Let me leave the G20 with the question that this summit should be asking:

[I would also add that the blob at (1,6) which is nearly in the D zone is Vietnam – I want to hear more about what they have done right!]

The post Doing the Doughnut at the G20? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers