Duncan Green's Blog, page 81

November 21, 2018

What might a 100% experimental Oxfam Country Programme look like?

Oxfam GB’s new boss, Danny Sriskandarajah, starts in the New Year, but is already talking to people inside and outside

Meet the new boss

the organization about what a ‘Nextfam’ could look like. Here’s some thoughts from a chat with him and David Bonbright earlier this week.

The problem: Experiments and innovation at the project level seldom spread beyond the bounds of the project. I’ve been banging on for years about things like multiple parallel experiments in Tanzania, but it hasn’t exactly lit a fire. New ideas seem to spread more easily through startups (GiveDirectly was partly inspired through our in Vietnam) and spin offs.

But what could we do to promote new practices within Oxfam? One option is to take the whole organization off down some new path, but innovation by its nature carries a higher risk of failure, so turning the whole of Oxfam into an innovation hub would carry unacceptably high risks. So instead, how about something in between the project and the world? A sandpit country programme, where everything is experimental/different from plain vanilla aid approaches.

Which country? Two options: a stable low or lower middle income country with relatively predictable politics and an active civil society (eg Malawi, Cambodia) or a fragile/conflict affected state (FCAS) like DRC. Arguments for the former: easier to experiment, lower risks (e.g. violence) attached to failure; arguments for the latter: FCAS are the future of aid – that’s where poor people will overwhelmingly live in the decades to come, as more stable countries grow their way out of poverty. What’s more, traditional aid approaches fail more often in FCAS, so donors and aid organizations are likely to be more open to new thinking.

How to get there? If we want to give the country the space to experiment, we will have to find enough unrestricted funding (not tied to specific projects) and spend time identifying a country director with the right instincts and drive, then let them appoint their team.

What kinds of experiments they decide to try would depend on context and skills, obviously, and an extended inception phase of listening and incubating ideas with local partners before designing a programme, but some possible ideas, which could cover the three main areas of long term development, humanitarian response and advocacy, include:

What kinds of experiments they decide to try would depend on context and skills, obviously, and an extended inception phase of listening and incubating ideas with local partners before designing a programme, but some possible ideas, which could cover the three main areas of long term development, humanitarian response and advocacy, include:

Asset based programming (assets include social capital and relationships, knowledge/skills and material goods). Reading a fascinating book by Hilary Cottam on how this applies in the UK context at the moment – review to follow.

Focus on building the resilience of domestic civil society organizations, including their ability to raise funds locally

‘Beyond the project’ programming, eg scholarships and leadership grants; long term core funding; Positive Deviance

Multiple parallel experiments on the same topic/same locality

Working with unusual suspects (traditional leaders, faith groups, artists)

Lots of facilitation/multi-stakeholder approaches

South-South exchanges

Deep (preferably feminist) localization of resources to local organizations eg in humanitarian response

Should we insist on a nothing boring/standard rule – i.e. innovation only?

If this is going to influence the rest of Oxfam and beyond, we would need to invest in rigorous, credible research and learning. That could include

real time accompaniment, eg by an independent local or international researcher, to document the experiments, successes/failures, the changes in direction etc as they occur (things always get airbrushed in retrospect, so no good waiting til the programme ends)

Commitment to ongoing, independent feedback channels from both individual beneficiaries and local partner organizations, which are used to adapt/redesign the work. That would include both feedback on the

programmes, but also the quality of the relationship with Oxfam.

programmes, but also the quality of the relationship with Oxfam.At this point, someone normally says ‘oh, we’ve been doing that for 10 years’ – feel free, and send links.

Otherwise, what other new/innovative approaches belong in the sandpit? Over to you.

The post What might a 100% experimental Oxfam Country Programme look like? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 20, 2018

How can we rate aid donors? Two very different methods yield interesting (and contrasting) results

quality, and a bottom up survey of aid recipients. The differences between their findings are interesting.

The Center for Global Development has just released a new donor index of Quality of Official Development Assistance (QuODA), with a nice blog summary by Ian Mitchell and Caitlin McKee.

‘How do we assess entire countries? One way is to look at indicators associated with effective aid. The OECD donor countries agreed on a number of principles and measures in a series of high-level meetings on aid effectiveness that culminated in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005), the Accra Agenda for Action (2008), and the Busan Partnership Agreement (2011). Our CGD and Brookings colleagues—led by Nancy Birdsall and Homi Kharas—developed QuODA by calculating indicators based largely on these principles and grouping them into four themes: maximising efficiency, fostering institutions, reducing burdens, and transparency and learning.’

QuODA’s 24 aid effectiveness indicators were then averaged to give scores to the 27 bilateral country donors and 13 multilateral agencies.

QuODA’s 24 aid effectiveness indicators were then averaged to give scores to the 27 bilateral country donors and 13 multilateral agencies.

I’d pick out two findings from this exercise:

Big is (on average) better – there’s some kind of line of best fit that suggests aid quality is higher for governments that commit a higher % of their national income. But there are outliers – New Zealand is small but beautiful; Norway is big and ugly.

The best performers are a mix of bilaterals and multilaterals, although there’s a cluster of multilaterals just below the kiwis at the top

But there’s another, completely different, approach – ask people on the receiving end what they think of the donors. AidData have been doing this for years, so I took a look at their most recent ‘Listening to Leaders’ report.

The report is based on a 2017 survey of 3,500 leaders (government, private sector and civil society) working in 22  different areas of development policy in recipient countries.

different areas of development policy in recipient countries.

‘Using responses to AidData’s 2017 Listening to Leaders Survey, we construct two perception-based measures of development partner performance: (1) their agenda-setting influence in 64 shaping how leaders prioritize which problems to solve; and (2) their helpfulness in implementing policy changes (i.e., reforms) in practice. Respondents identified which donors they worked with from a list of 43 multilateral development banks and bilateral aid agencies. They then rated the influence and helpfulness of the institutions they had worked with on a scale of 1 (not at all influential / not at all helpful) to 4 (very influential / very helpful). In this analysis, we only include a development partner if they were rated by at least 30 respondents.’ Sadly New Zealand (top on QuODA) didn’t make the cut in the AidData analysis.

On this exercise, the multilateral organizations clean up, with the US the top-rated bilateral donor at number 8 on helpfulness (the much criticised European Union comes in at number 5).

I would love to hear views on why this might be. Off the top of my head, a couple of possible explanations:

Multilateral organizations are on average bigger, so have more presence in the lives of people on the receiving end

The surveys were measuring different things – aid quality v support for policy reform

Multilateral organizations may do better on the soft stuff – technical assistance, but also partnership, dialogue etc

Thoughts?

The post How can we rate aid donors? Two very different methods yield interesting (and contrasting) results appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 19, 2018

Can new tech revive the world’s trade unions?

The Economist never ceases to surprise and inform. This week’s issue carries an excellent special report on ‘trade

Did something happen in 2008?

unions and technology’. Here’s an edited extract:

‘Support for organised labour is rising again (see chart). And technology may again play a central role in helping a revival—particularly in America, where activists are trying inventive new ways to organise workers.

Use of social media is taking the place of the shopfloor meeting in what is called “connective action”. Facebook, Reddit and WhatsApp, as well as tools such as Hustle, a texting service, allow labour groups to do three things: collect information, co-ordinate workers and get the word on campaigns out to the wider world.

Start with information. Although they work independently, many Uber drivers are active in chat groups and other online forums. The ride-hailing firm often tests new features of its app on a small group of drivers—without telling them what is going on. Online communications are an attempt to overcome this “information disadvantage”, says Alex Rosenblat, author of “Uberland”, a new book about the firm.

Comparing notes is also widespread among users of global crowdsourcing platforms such as Mechanical Turk and Freelancer, where digital labour is traded.

As for the second objective, co-ordination, without digital tools teachers’ strikes in West Virginia and other American states earlier this year would not have been as successful as they were, explains Jane McAlevey, a longtime organiser and author of several books on unions in America. In West Virginia teachers set up a Facebook group that was open only to invited colleagues. Nearly 70% of the state’s 35,000 teachers joined. The group became the hub of discussions on what to demand and how to organise protests.

Unions are shrinking – could tech help reverse that?

The West Virginia strike is a good example of the third objective: getting the word out. The Facebook group turned into a factory for hashtags and “memes”, memorable images or video clips that spread virally online. The same sort of thing happened when Starbucks, a chain of coffee shops, refused to let baristas show their tattoos. Management caved in after employees took pictures of their body art and uploaded them to social media.

However, services such as Facebook and WhatsApp are not designed for mass activism. As a result, activists have started to develop digital services specifically for labour groups.

Coworker.org is an early instance. Founded in 2013, the website helps workers condense their demands in a petition and spread them on social media. Starbucks employees have launched several successful campaigns, and not only about tattoos. They pushed the firm to minimise “clopening”, for example—where the same person closes a store late in the evening and opens it at the crack of dawn the next day.

Coworker.org was long an isolated example. Recently similar services have flourished by mimicking the startup approach and “unbundling” the roles of official unions.

Some startups aim to fulfil the role of informing workers and recruiting members. Two years ago OUR launched WorkIT, a smartphone app for Walmart workers. After signing up, users are presented with a simple chat interface where they can ask questions about the retail chain’s complex workplace regulations. Volunteers, often Walmart employees themselves, answer.

Others concentrate on helping workers voice their opinions. Union bosses have often been criticised for not paying much heed to the rank-and-file’s demands. Workership is a platform that attempts to bring structure to often freewheeling discussions online and to enable employees to pipe up without fear of repercussions (posts are anonymous). Collective-bargaining agreements, for instance, are broken down into small segments which members can discuss.

Then comes finding ways to make money to finance activities. The Independent Workers Union of Great Britain has resorted to crowdfunding its legal actions against Deliveroo, an online-delivery firm, which it accuses of having denied employment rights to its riders.

Some of these projects are spreading. WorkIT, which licenses its system to other labour organisations, has six takers, including the Pilipino Workers Centre in Los Angeles and United Voice, an Australian union. Coworker.org has been used by employees from more than 50 companies. For Starbucks it has become a union of sorts. Over 42,000 people in 30 countries are connected via the service.

Yet, as any startup will confirm, launching a new service is much easier than expanding one. Most of the fledgling

How many of you are on Whatsapp?

labour-tech projects rely on donations from philanthropists, socially minded investment funds and similar sources. It is not clear where the capital would come from to allow them to grow. In addition, these services lack the legal standing and political power of conventional unions.

Labour startups may need the support of existing unions if they are to turn into a force to be reckoned with. The best outcome would be if grassroots groups and conventional unions teamed up. Unions could become service providers for self-organising groups, helping them with things such as legal advice and lobbying.

The digital world has been embraced by some unions. Worried about the rise of crowd-working, Germany’s IGMetall, the country’s largest union, now allows self-employed workers to join. In 2015 it also launched a site to compare conditions on different crowdworking platforms, called Fair Crowd Work.

Some unions have even set up innovation units. One is HKLab, created a year ago by the National Union of Commercial and Clerical Employees, Denmark’s biggest union. Experiments include a chatbot for member inquiries and a service centre for freelancers. America’s National Domestic Workers Alliance operates Fair Care Labs, a service to improve the lot of nannies, carers and house cleaners. It will soon launch Alia, a portable-benefits service. Clients make voluntary payments of $5 per job, which allows cleaners to get some insurance coverage and paid time off.

However promising such projects, they are unlikely to help labour regain its erstwhile bargaining power soon. But if the digital labour movement has proven anything so far, it is that information and data are ever more powerful. Bad publicity is the digital equivalent of the picket line, says Michelle Miller, co-founder of Coworker.org.

Obtaining more and better data could give rise to what Fredrik Soderqvist of Unionen, a Swedish union, refers to as “predictive unionism”. His organisation is building a system that could mine information it has about its members as well as data from other sources. The idea is to offer services such as telling workers when they should ask for a raise. Algorithms could also predict the likelihood of lay-offs, if say a new chief executive takes over, and hence the need to get members ready to act.

For now, unions still look weak. Membership continues to decline. But their history shows that the relative power of labour and capital is constantly in flux. Recent decades have been tough on labour, largely as a consequence of technological change. But technology may also be the thing that helps turn their fortunes around.’

The post Can new tech revive the world’s trade unions? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 18, 2018

Links I Liked

This is from a Wetherspoons (UK pub chain) training session but it feels like it could apply to lots of other institutions too. Ht Ben Phillips

Less than two weeks to go until Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (aka AMLO) becomes Mexico’s new president. Check out my podcast with Ricardo Fuentes for background and reflections  on the role of Civil Society in the ‘4th transition’ soundcloud.com/fp2p/ricardo-f…

on the role of Civil Society in the ‘4th transition’ soundcloud.com/fp2p/ricardo-f…

‘The sign language interpreter doing the Brexit Agreement on BBC News is perfectly conveying the perplexing fuckery of this situation’ ht Ell Potter

So here’s a mindmap of Xi Jinping Thought, according to the People’s Daily. Anyone done one for Donald Trump or Teresa May?

7 challenges facing today’s campaigner…. Excellent listicle from Tom Baker

The aid experience in South Korea

Brexit protest: Persistence + a basic understanding of camera angles + British decorum (no-one gets violent) = Boom!

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 17, 2018

Audio summary (6m) of FP2P posts for week beginning 12th November

The post Audio summary (6m) of FP2P posts for week beginning 12th November appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 15, 2018

So what might ‘Beyond the Project’ Activities look like?

Some thoughts in response to yesterday’s challenge from Brady Mott. What might replace the project? On one level, it’s a self-defeating exercise – any alternative is likely to require spending money, staff etc and some kind of accountability. Boom – we’re back to projects!

But some projects can loosen the kinds of constraints that Brady describes, getting away from the dead hand of The Plan, freeing change makers to be more innovative, to spot and surf promising waves etc etc. Here are three ways to do that – I’m sure I can rely on you to point out lots of others:

Core Funding

There’s a huge difference between ‘here’s some money, along with 23 key performance indicators, and a set of project milestones/millstones and reporting requirements, all decided in advance and immutable’ and ‘we like what you do, here’s some money. Use it as you see fit, but please tell us what you do with it.’ That latter version can happen at different levels:

Individuals: As I wrote in Fit for the Future 2.0 (haven’t got round to publishing it yet, so here’s the final draft: Fit-for-the-Future-2-final-July-2018), ‘Inspirational and talented leaders and change agents repeatedly resurface in different guises and projects. So why not shift to sponsoring potential or actual leaders directly, rather than obliging them to invent projects to access funding? Yes, we’re back to good old-fashioned scholarships, but with a radical edge (the 100 grassroots women changemakers scholarship fund?). Could we imagine a mentored scholarships programme, so you link a Southern based experienced changemaker to a promising novice? Link them to training providers?’ Check out the MacArthur Foundation Genius Grants for an existing high-end version.

Cash transfers, whether small weekly amounts or one-off big lump sums, are another increasingly popular way of cutting the project strings.

Organizations: Every organization looking for money to run its operations prefers core funding to projects. Core funding gives them the flexibility they need to be agile, respond to events, move money to where it’s needed etc.

Organizations: Every organization looking for money to run its operations prefers core funding to projects. Core funding gives them the flexibility they need to be agile, respond to events, move money to where it’s needed etc.

The problem for those handing over the money is a mix of accountability and trust. The donor wants to be able to show where the money is going, and if trust is low, projects are also a way to tie the recipient down to doing particular things the donor thinks might be useful. Core-funding is more likely when there’s a long-established relationship between donor and recipient, or some institutional common ground (eg between members of the same faith network). How can we build the relationships and trust needed to reverse the decline in core funding?

Governments: The largest scale variety of core funding is General Budget Support, through which donors fund developing country government budgets, but leave spending decisions up to them. The benefits and risks are much the same as for other organizations, albeit on a grander scale. GBS has fallen out of favour of late, as aid donors worry about maintaining support for aid with their own publics, parliaments and media – the potential ‘DFID bungs money to dictators, no questions asked’ tabloid headlines weigh heavy on politicians’ minds. What might enable them to rebuild the case for GBS?

Positive Deviance

Regular readers will know this is (or at least, may be) my next thing. I won’t repeat all the arguments, but here’s the gist from the most recent PD post’, which got dozens of great comments from readers:

‘The starting point of PD is to ‘look for outliers who succeed against the odds’ – the families that don’t cut their daughters in Egypt, or the kids that are not malnourished in Vietnam’s poorest villages. On any issue, there is always a distribution of results, and PD involves identifying and investigating the positive outliers, and seeing if/how the lessons of how they did better than the rest can be spread. In the famous case in Vietnam, identifying slightly different feeding practices in outlier households led to big nutritional improvements for millions of kids.

This differs from the ‘standard model’ of aid in two big ways: it focuses on success, not failure/problems – places where the system has thrown up solutions to a given problem – and it replaces, or at least minimises, the role of ‘external interventions’ such as aid projects. Bye bye White Saviour complex/salvation by outsiders. For that alone, I love it!’

I’m still talking to people and reading stuff about PD, but some of the ideas that are being thrown up include whether PD might be particularly suitable for fragile/conflict places where nothing else works, and whether it is best applied to individuals, institutions or kinds of interventions (PD of projects!).

Outcome-Based Funding

There are market-led ways to rearrange incentives away from projects, by rewarding what aid wonks call ‘outcomes’  rather than insisting on particular project activities. If you achieve something, you get the money, and we don’t mind how you get there. Many of them have been cooked up and promoted by the Center for Global Development, achieving various levels of adoption by aid donors. I’m often sceptical about these approaches, (that’s a subject for a different post), but they all fit the criteria for ‘beyond the project’ innovation, with links:

rather than insisting on particular project activities. If you achieve something, you get the money, and we don’t mind how you get there. Many of them have been cooked up and promoted by the Center for Global Development, achieving various levels of adoption by aid donors. I’m often sceptical about these approaches, (that’s a subject for a different post), but they all fit the criteria for ‘beyond the project’ innovation, with links:

Payment by Results

Advance Market Commitments

Development Impact Bonds

OK, that’s a few ideas from me. What else you got?

The post So what might ‘Beyond the Project’ Activities look like? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 14, 2018

What’s the problem with Projects?

moving ‘Beyond the Project’. Today’s guest post by Brady Mott explains the problem with projects. Tomorrow I’ll explore some alternatives.

The development sector has always engaged with the world through the vehicle of projects: logistically intricate arrangements linking financiers, NGOs, governments, businesses and ‘beneficiaries’ together into formalized schemes that attempt to achieve a goal through a series of predetermined activities.

Historically, projects have tended to be about resource transmission – be they financial resources, intellectual resources, physical resources, capacities, skills or whatever – from the wealthy regions of the world to what sensitive intellectuals like to call the ‘global south’. This typically takes the form of activities like service delivery, infrastructure installation, educational programming and loan servicing, and usually flows unidirectionally from the ‘haves’ – those who already possess the required resources – to those who ‘have-not’.

And that’s a project – an agreement by a bunch of parties who take part in activities intended to accomplish a common goal.

But the goals of the different members can vary quite drastically from the officially stated goal of the project. The financing organization of any project, for example, holds a highly significant amount of decision-making power in the project relationship. The execution of activities in any development project is generally contingent on a number of conditions set by the donor. These conditions are often logical, relevant and sensible. Sometimes, however, they don’t relate to the goals of the project or even to the eradication of poverty in general.

Take, for example, the first-ever financial activity undertaken by the World Bank. In 1947, the Bank loaned $250 million to France to fund post-war reconstruction, modernize the country’s waning steel industry and improve the national transportation system. It was the first of its kind; a massive injection of capital into a war-ravaged nation, offered by the newly-born Bretton Woods institution with the goal of rehabilitating Europe and promoting wider economic growth. This loan came with strict conditions: in addition to demanding a meticulously balanced budget and first priority for debt repayment (fairly sensible terms considering the size and context of the loan), the Bank required that all members of the Communist Party be removed from the democratically-elected French coalition government.

The implications of this are enormous. This type of conditionality, demanding profound political and economic restructuring on the part of the debtor country as a prerequisite for the loan, set the stage for the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to exert political and economic pressure on debtor countries in the coming decades, for example through economic conditions, political contingencies and so-called Structural Adjustment Programs. This type of power dynamic is part and parcel of the nature and design of development projects, and permeates not only the project mentality but also pervades the entire notion of ‘development’ itself.

And it’s not just the Bretton Woods institutions that perform this type of power play through the financing conditions of development projects; it is all donors, governments, and NGOs who have a vision of a better world and a belief system that drives their strategy of how to get there. We here at Oxfam have a great number of clearly defined conditions for engaging in any given project, conditions that reflect our values and theories of change as an organization. Our requirement to reach a certain number of women through project activity, for example, reflects our institutional conviction that unbalanced gender dynamics are a leading driver of poverty. We won’t engage in certain projects that don’t meet our gender criteria.

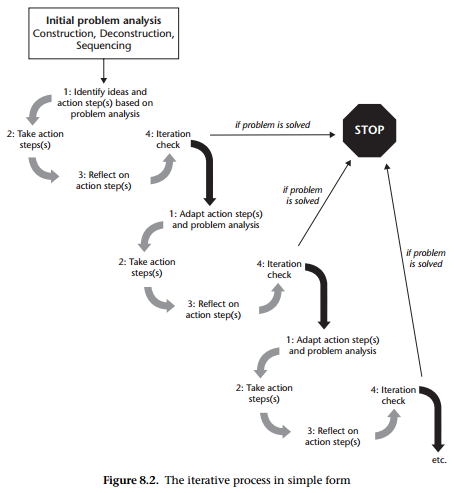

By Bill Crooks, based on an original concept by Nigel Simister

And that is good; we should have conditions determining the nature of the projects we engage in. Setting standards and conditions is how we actualize our organizational values and drive the project in what we see as the right direction for meaningful and lasting change. The difficulty, though, is that the power to decide these conditions is always exercised by the powerful ‘haves’ – the donors, the governments, the NGOs – and seldom by the ‘have-nots’ – the people for whom these projects are ostensibly being created. The ability to drive the poverty-eradication process is granted entirely to the powerful, and stripped away from the powerless, further entrenching the power imbalance that projects are meant to overcome in the first place.

This irony is pretty well demonstrated in what is perhaps the quintessence of all projects: the Millennium Villages Project. The MVP was a $200 million goliath, founded jointly by the UNDP and the Earth Institute at Columbia University, driven by the Millennium Development Goal framework and formulated under the auspices of the Bono of development economics himself, Jeffrey Sachs. It was also a paragon of ineffectual, top-down development planning and an archetype of unidirectional power flow. Between the project’s failing to reach proposed targets, misreporting the numbers on impact evaluations, and Sachs making an embarrassing, quasi-colonial show out of people’s poverty, there are no shortage of things to criticize about the MVP. But the MVPs’ relevance to the issue of projects, and their inherent power imbalances, is best summarized by the author of Sachs’ biography, Nina Munk, when describing the strange power relationship between Sachs and residents of Sauri, the first MV:

“One of the astonishing discoveries was how quickly the villagers realize that when the rich white guy shows up, they have to reassure that visitor that his donations are going to good use. So, when Jeffrey Sachs visited, he got a skewed picture of reality. That’s survival; any one of us would do the same – and you would be stupid not to.”

So, instead of being drivers of the processes that are meant to effect change in their own lives, the residents of Sauri – or ‘villagers’, if you want to be offensive about it – were forced into the passenger’s seat, required to play the part of cheerleader in the process of their own economic development. Their role was not to actively transform their community in a way that they saw as being advantageous to them; it was instead to passively have development enacted upon them, to have wealthy, foreign experts dictate to them the ‘right’ strategies of how to overcome poverty, and to cheer them on, even as the project faltered, so that the funding wouldn’t dry up.

But let me be clear: the issue at hand is not the shortcomings of Sachs, or the MVP, or the World Bank or the IMF. It is the construct of the project, its governing power structure, and the implications that that power structure actually has for global economic development. We need to rethink the entire framework of development activity; but how do you even do development without a project?

Over to Duncan on that one.

Brady Thomas Mott is a member of Oxfam’s Transparent and Accountable Finance Team

The post What’s the problem with Projects? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 13, 2018

What can we learn from campaigns run by the world’s children and young people?

There’s nothing new about children and youth being involved in movements for change, from the anti-apartheid cause in South Africa, to the earlier and more hopeful chapters of the Arab Spring. But what feels different now is that young people are increasingly creating and leading campaigns themselves. Many of these campaigns are being pulled together very quickly, using digital channels, with limited resources and little formal governance. Usually this is being done by young people who may have little formal experience of campaigning, but maybe for that reason, are less jaded, and more willing to take risks.

There are open questions about how durable many of these campaigns are in terms of impact. Some movements emerge in response to a specific outrage, and can subside almost as quickly, once political and media attention moves on. Others lose momentum in the transition from mobilisation to organisation. For example, the March for Our Lives campaign for gun control didn’t secure its objectives in the US mid-terms in Florida (at the same time, the history of campaigning shows that you can lose battles but win the war, and March for Our Lives may well have all sorts of long-term indirect benefits in fostering civic engagement).

But what struck me most was that, of all the examples shared in the conference – from student-led road safety campaigning in Bangladesh, to Australian children campaigning against single use plastics – none was initiated, driven or significantly supported by traditional NGOs.

A group of us spent time at the conference discussing the searching questions such campaigns raise about how we’re approaching change, and working with children and young people to make it happen.

A group of us spent time at the conference discussing the searching questions such campaigns raise about how we’re approaching change, and working with children and young people to make it happen.

A few key themes came through:

Logos and egos – the widespread preoccupation with NGO brand and profile in campaigns can be a major turn-off for many child and youth campaigners. Big, brand-conscious NGOs find it especially hard to leave egos and logos at the door, but will increasingly struggle to be heard by young people unless they do so.

Agility – many of the most powerful child- and youth-led campaigns are fast and improvisational, testing different approaches as they go along, to see what works best. At least in their initial stages, they’re light on governance and decision-making, and are not shackled to a rigid strategy. In contrast, NGO campaigns tend to overestimate how much we’re in control of the agenda we’re seeking to influence. Big organisations tend to create slow and difficult decision-making, which can paralyse the campaigning muscle.

Support, incubate and release – it may be that organisations with revenues in the hundreds of millions and  many thousands of staff cannot easily become agile, movement-based campaigners. But our advocacy-led campaigns can often be a powerful complement to grass roots activism, and we do have lots of skills, resources and connections that can be useful to child-led campaigns. One suggestion, from Change.org, was that all INGOs should create youth organisations, where they agree on the goals, give them some start-up resources, and then let go. Save the Children Norway has done something very like this, but such a bold approach is still the exception rather than the rule.

many thousands of staff cannot easily become agile, movement-based campaigners. But our advocacy-led campaigns can often be a powerful complement to grass roots activism, and we do have lots of skills, resources and connections that can be useful to child-led campaigns. One suggestion, from Change.org, was that all INGOs should create youth organisations, where they agree on the goals, give them some start-up resources, and then let go. Save the Children Norway has done something very like this, but such a bold approach is still the exception rather than the rule.

Campaigning with, and about people – many of the most effective child- and youth-led campaigns are led by people directly affected by the issues on which they’re campaigning: from movements to confront gender-based violence on Indian campuses, to Black Lives Matter in the US. This gives the campaigns integrity and authenticity. Campaigning rooted in personal experience can also have its own shortcomings, if single-issue campaigning becomes isolated from wider movements for justice. However, the ‘nothing about us without us’ mantra does challenge INGOs. Too often our campaigns (and programmes) have limited input from the people who are the focus of the desired change. Coalitions and partnerships are frequently an afterthought, rather than a starting point.

Many INGOs are mobilising adult campaigners in one place (usually wealthier countries) on issues affecting people in another (poorer, more marginal) place. Where they do engage children, it’s often easiest to do this amongst the educated, networked and mobile. Solidarity campaigning between people of relative privilege, and people who are more affected by an issue, has a valid place in the campaign ecosystem. But any campaign to achieve progressive change will only ring true if it models that change, by redistributing power and voice to those who currently have less  of it.

of it.

Protection and voice – there’s a tension between the right of children to participate, and have a voice, and their right to be protected (by adults). The Syria conflict began with the torture and murder of a teenage boy who campaigned against the government. There are plenty of bad examples of children being exploited in campaigning movements, and exposed to personal risk, such as the recent sexual abuse scandal involving youth campaigning networks at the UN Organisations that support child-led campaigns need to provide political cover, stay the course, and ensure robust safeguarding systems where their staff are working with children.

Campaigning space in programmes – operational INGOs like Save the Children that run programmes around the world have the potential to engage many more young people through their programmes, than through their traditional campaign activities, with the added advantage that many of those young people are directly affected by the issues of the campaign. Community level engagement on issues like FGM, child marriage, and disability, which require deep social shifts, is often a critical complement to campaigns for legislative and policy change, and helps to foster a culture of rights and accountability at the local level.

The question for INGOs is less and less how we create campaigning waves, and more how we ride them. A growing demographic youth bulge in Africa, South Asia and the Middle East; a global expansion in secondary education; technological change; and rapid urbanisation all mean that child- and youth-led campaigning movements are likely to grow in diversity and influence. This is a campaigning future that should excite anyone who cares about economic, social and environmental justice.

The post What can we learn from campaigns run by the world’s children and young people? appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 12, 2018

Old Wine in New Bottles? 6 ways to tell if a programme is really ‘doing development differently’

These days it seems that everyone in the aid sector is doing development differently – presenting themselves as politically smart, locally led, flexible and adaptive. But is it true? How much of this is “old wine in new bottles” – the language changing but the practice remaining much the same? And, if this is happening, what does a genuinely innovative and adaptive programme look like?

A small group of us – Angela Christie, Helen Derbyshire, Annette Fisher, Steve Fraser, and Wilf Mwamba – have been having a conversation about this – triggered by a recent conference in Brighton. We asked ourselves what tells us that a programme is genuinely adaptive – and on the other hand what rings alarm bells.

Here’s what we came up with.

A programme is adaptive if there is …..

A shared understanding of WHY THE PROGRAMME IS TAKING AN ADAPTIVE APPROACH

The programme donor, implementers and local partners have a shared understanding of what problem an adaptive approach will help them to solve and how being adaptive will lead to better results. Adaptive approaches generally apply to work in complex contexts, on complex issues with messy politics. Pathways to change are unpredictable, and more conventional blueprint approaches have had limited effectiveness.

Alarm bells ring for us when proposals, conversations and reports are littered with doing development differently buzzwords – but there’s no apparent understanding of why such an approach might be important in the programme context.

Alarm bells ring for us when proposals, conversations and reports are littered with doing development differently buzzwords – but there’s no apparent understanding of why such an approach might be important in the programme context.

A shared understanding of and commitment to ADAPTIVE PROGRAMMING IN PRACTICE.

Being adaptive, politically smart and locally led usually involves devolving significant operational and strategic decision-making to front-line staff and local partners. This means establishing systems, support structures and quality control mechanisms to enable frontline staff and local partners to watch and analyse their changing context, identify opportunities and momentum for change towards their strategic goals, learn from experience and adapt their interventions accordingly.

What adaptive programming is not is a programme without goals, or with continuously shifting goalposts. It is not a flexible fund built into a programme that otherwise continues with business as usual. PEA reports should be influencing thinking and action, not sitting on shelves – and in most cases, the team in the capital city shouldn’t be dominating decision making. It rings alarm bells for us when programme actions and approaches remain the same even as the context changes, and when programmes repeat actions which have not been successful hoping for a different result. And they ring particularly loudly when, through the life of the programme and despite changing contexts and opportunities for learning, the programme Log Frame and Theory of Change remain unchanged.

As much FLEXIBILITY as possible IN MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

Programme-related roadblocks – such as insisting on delivery against pre-set top-down results, fixed budgets, and contractually rigid technical or financial inputs – stand in the way of adaptation. In an adaptive programme, donors, implementers and local partners are working together from the outset to create as much flexibility as possible – to work with any partners and stakeholders, to respond to shifts in momentum and opportunity, to shift resources rapidly to where they are needed, and to provide necessary technical support. This means building flexibility into management and contracting processes, and buffering front line staff and local partners from top-down requirements that might otherwise govern and constrain their decision-making.

Alarm bells ring for us when the management team – donors and implementers – are not open about and actively and collectively trying to manage the contradictions and constraints to adaptive programming posed by commercial and contractual requirements.

A commitment to WORKING WITH THE RIGHT PEOPLE.

Working adaptively is more of an art than a science. At the front line, it involves being a ‘dancer’ and ‘dancing with

A ‘searchframe’ – the Building State Capability alternative to the logframe

the system’. It’s almost an approach to life. Adaptive programmes are re-orienting recruitment and appraisal systems, balancing technical expertise with softer skills, investing in people and nurturing potential. Important soft skills include a personal commitment to change; the ability to build trust and relationships; a willingness to listen, observe and understand; the courage to take opportunities without knowing where they will necessarily lead; and to make mistakes and learn from them. At the management level, technical skills are needed to find ways of adapting donor and supplier management systems to accommodate adaptive ways of wor

king.

Alarm bells ring for us when teams experienced in conventional programming are delivering an adaptive programme with no changes in recruitment and appraisal processes, no systematic support to enable and empower staff to work in different ways often outside their comfort zone, and no change in management style.

An ORGANISATIONAL CULTURE OF LEARNING

An organizational culture of learning includes systems and structures to enable front line staff and local partners to stand back from their day to day work, consider the bigger picture, reflect honestly on their actions, and learn from what is not working as well as what is. In programme management and donor teams, strategic reflection is needed on the overall programme approach, extending to “back room” processes that might otherwise constrain adaptive working.

Alarm bells ring when programme management information systems are focused primarily on performance management, and don’t provide front line staff and partners with information they can use for action learning and for adapting as they go. Another concern is when the focus of internal reporting is all on success, and there is no acknowledgement of or learning from what is not working.

An ability to TELL HONESTLY THE STORY AND LEARNING JOURNEY BEHIND RESULTS

Results are not simply about numbers and delivery – but about behaviour change, set-backs, learning and progress on a journey of reform. In reporting results, adaptive programmes are telling their story – communicating a learning journey, positioning results in their context, and giving a realistic assessment of the programme’s contribution to

change relative to other factors. Their communications enable an appreciation of how the programme is working and why, and contribute to wider debates about programme approaches.

Alarm bells ring for us when programme communications take a conventional approach – focused on churning out good news stories and self-promotion of the programme’s achievements.

These are our initial thoughts. We’d all be really interested to hear yours.

The post Old Wine in New Bottles? 6 ways to tell if a programme is really ‘doing development differently’ appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

November 11, 2018

Links I Liked

What Robopocalypse? Charles Kenny does his evidence-based Pangloss thing to show that the robots really aren’t taking our jobs. But if they do, the right policy responses are not that different.

Need some more good news? Prevalence of FGM among girls aged 14 and under in east Africa has dropped from 71.4% in 1995, to 8% in 2016

‘Toys inside soap can increase handwashing among kids in emergency humanitarian contexts.’ Ht Tobias Denskus

US-China trade tensions are pushing firms to diversify their supply chains. Result: ‘Vietnam, once dependent on garments and other cheap exports, has begun to rival China’s tech sector.’ ht Steve Price-Thomas

8 lessons on how to influence policy with evidence – from Oxfam’s experience, The World Bank’s David Evans & Markus Goldstein summarize our new paper much better than I did.

Seems utterly ridiculous this was Christmas ad (a collaboration between a UK Supermarket and Greenpeace) was banned (but it’s had 1.5m hits anyway)

The post Links I Liked appeared first on From Poverty to Power.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers